Abstract

Multilocus sequencing was used to compare Campylobacter sp. strains isolated from retail chicken products and humans with gastroenteritis in central Michigan. Sequence comparisons demonstrated overlapping diversity between chicken and human isolates. Campylobacter jejuni isolates from clinical sources had a greater diversity of flagellin alleles and a higher rate of quinolone resistance than isolates from retail chicken products.

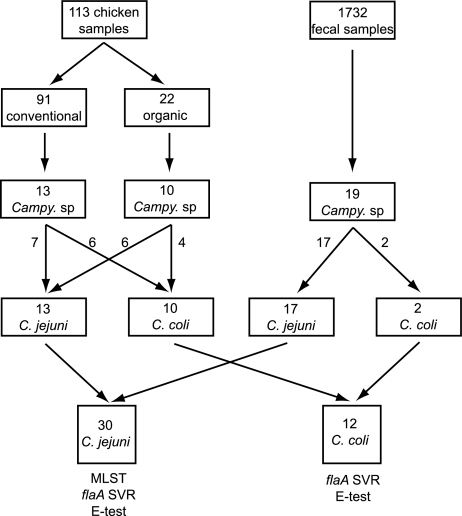

Campylobacter species are a frequent cause of foodborne illnesses in the United States (1). Because Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates occur in high numbers in the gastrointestinal tracts of chickens (18) and can be readily recovered from retail chicken products (7, 8), sporadic human infection is thought to arise most commonly via contaminated poultry products (15). To examine this link, we cultured for Campylobacter isolates from retail chicken products from 12 supermarkets in the Lansing, Michigan, area by using selective plates and filter enrichment techniques. Twenty-three Campylobacter isolates were recovered from 113 chicken samples over an 11-week period (Fig. 1). At the same time, 19 Campylobacter isolates from patients with gastroenteritis were obtained from the clinical laboratory of a private hospital in Lansing.

FIG. 1.

Isolation and characterization of Campylobacter from retail chicken samples and human clinical fecal specimens. One hundred thirteen samples of retail chicken products and 1,732 human fecal samples were cultured for Campylobacter species (Campy. sp.) by use of selective media. The chicken samples came from both organically raised and conventionally raised poultry. Campylobacter isolates were identified to the species level by a panel of biochemical and molecular techniques as C. jejuni and C. coli. Both C. jejuni and C. coli isolates were analyzed by determination of quinolone susceptibility by Etest and determination of the sequence of the flaA short variable region.

DNA was extracted from all Campylobacter isolates. C. jejuni and C. coli were identified by amplification of the flaA gene (16) and discriminated by PCR assays targeting the hippuricase (N-acyl-l-amino-acid amidohydrolase) gene (hipO) of C. jejuni and a C. coli-specific chromosomal sequence (10). Thirteen chicken isolates were C. jejuni isolates (56.5%) and 10 were C. coli isolates (43.5%), whereas 17 human isolates were C. jejuni isolates (89.5%) and 2 were C. coli isolates (10.5%). Compared to the isolation of these two species from retail chicken products, C. jejuni was significantly more likely to be isolated from human clinical specimens than C. coli (P = 0.015; χ2 test).

To determine the clonal relatedness of strains, we used multilocus sequence typing (MLST) devised for C. jejuni (4, 13, 19) as a tool for epidemiologic investigation (3). Sequence analysis of seven housekeeping genes (4) identified, on average, 15 polymorphic nucleotide sites per locus for the 30 C. jejuni strains from both clinical and retail chicken product samples (Table 1). There was substantial overlap between the alleles found in strains recovered from chickens and those from patients. No alleles were specific to either source; shared alleles were found for all seven genes (Table 1). In terms of the multilocus genotypes, there were 21 sequence types (STs) resolved, 4 (19%) of which were identified in both human and chicken isolates.

TABLE 1.

Genetic diversity at C. jejuni MLST loci, hipO, and flaA

| Locus | No. of bp | No. of variable sites | No. of alleles | Effective no. of alleles | No. of alleles shared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aspA | 477 | 10 | 9 | 4.4 | 3 |

| glnA | 477 | 14 | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| gltA | 402 | 7 | 6 | 3.7 | 4 |

| glyA | 507 | 25 | 10 | 5.7 | 3 |

| pgm | 498 | 30 | 12 | 7.6 | 5 |

| tkt | 459 | 15 | 7 | 3.4 | 4 |

| uncA | 489 | 4 | 4 | 2.7 | 3 |

| hipO | 377 | 17 | 14 | 8.7 | 4 |

| flaA | 321 | 82 | 21 | 16.1 | 2 |

| MLST averagea | 472.7 | 15 | 8.3 | 4.8 | 3.7 |

| Overall averageb | 445.2 | 22.7 | 10.3 | 6.5 | 3.6 |

Average values for the first seven loci, which were those used for the initial MLST analysis.

Average values for all nine loci, including hipO and flaA.

The average pairwise sequence divergence of the MLST loci among the human isolates (∼1%) was the same as among chicken isolates. The net genetic distance between chicken and human isolates combined was virtually zero, providing no evidence for genetic differentiation between poultry and human clinical isolates. Seventeen of the 30 (57%) C. jejuni strains belonged to previously recognized STs (Table 2). The remaining 13 isolates represent nine new sequence types. ST-21, ST-475, ST-918, and ST-937 were represented by both human and chicken isolates. Thirteen (43%) isolates belonged to novel STs, suggesting that unique STs circulate in local geographic regions (5).

TABLE 2.

Multilocus sequence typing analysis of C. jejuni isolates

| Isolatea | Allele no. for indicated geneb |

Sequence typeb,c | Clonal complexc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aspA | glnA | gltA | glyA | pgm | tkt | uncA | |||

| Chx-02 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 2 | 156 | 3 | 6 | 937 | 353 |

| Hum-13 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 2 | 156 | 3 | 6 | 937 | 353 |

| Chx-06 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 156 | 3 | 6 | 939 | 353 |

| Hum-07 | 9 | 112 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 936 | 353 |

| Hum-15 | 8 | 113 | 5 | 121 | 10 | 25 | 6 | 1048 | 353 |

| Chx-09 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 353 | 353 |

| Chx-04 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 21 | 21 |

| Hum-17 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 21 | 21 |

| Chx-17 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 21 | 21 |

| Hum-14 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 21 |

| Hum-10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 140 | 3 | 5 | 806 | 21 |

| Hum-03 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 48 | 48 |

| Chx-03 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 62 | 5 | 475 | 48 |

| Hum-01 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 62 | 5 | 475 | 48 |

| Hum-04 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 5 | 918 | 48 |

| Chx-10 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 5 | 918 | 48 |

| Chx-05 | 24 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 59 | 6 | 923 | 460 |

| Chx-18 | 24 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 59 | 6 | 923 | 460 |

| Chx-22 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 45 | 45 |

| Hum-18 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 42 | 7 | 1 | 137 | 45 |

| Hum-05 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 84 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 467 | 49 |

| Hum-02 | 9 | 25 | 2 | 10 | 22 | 3 | 6 | 52 | 52 |

| Hum-08 | 62 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 572 | 206 |

| Hum-06 | 7 | 17 | 2 | 15 | 23 | 3 | 12 | 51 | 443 |

| Hum-09 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 83 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 922 | Unk |

| Hum-12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 83 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 922 | Unk |

| Chx-11 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 53 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 924 | Unk |

| Chx-21 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 53 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 924 | Unk |

| Hum-19 | 7 | 84 | 1 | 10 | 157 | 1 | 6 | 938 | Unk |

| Chx-07 | 2 | 4 | 27 | 122 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 940 | Unk |

Chicken (Chx) and human (Hum) isolates of C. jejuni were subjected to MLST analysis.

Boldface indicates alleles and STs first described in this study.

Sequence types and clonal complexes were assigned using the PubMLST database. Unk, unknown.

Sixteen C. jejuni strains isolated here grouped into the clonal complexes ST-21, ST-48, and ST-353. Along with 1 strain each in the complexes ST-52 and ST-49, these 18 strains (60% of the C. jejuni isolates) fell into 1 of 17 clonal complexes that encompassed 92% of 814 C. jejuni strains, forming a diverse collection mainly from the United Kingdom and The Netherlands (3).

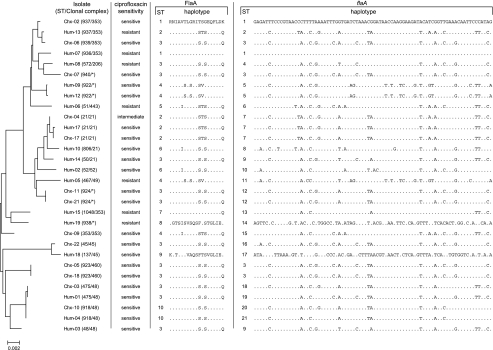

To further quantify the genetic diversity of C. jejuni, we examined sequence variation in two common traits used for Campylobacter subtyping. First, we examined allelic variation in hippuricase by designing primers (hipO-F156, 5′-AAT AGG AAA AAC AGG CGT TG-3′; hipO-R721, 5′-GTC CTG CAT TAA AAG CTC CT-3′) to amplify a 566-base-pair region in hipO. Sequencing of a 377-base-pair internal region of this amplicon revealed 17 polymorphic sites and 14 distinct hipO alleles among the 30 C. jejuni isolates with nucleotide variation comparable to that of the seven MLST loci (Table 1). A dendrogram constructed by combining the seven MLST and hipO sequences (the MLST sequences were submitted to the PubMLST Campylobacter database [http://campylobacter.mlst.net]) demonstrates overlapping relatedness and diversity of chicken and human strains (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Relationships between C. jejuni isolates from retail chicken products (Chx isolates) and from humans with gastroenteritis (Hum isolates) as determined by MLST, antibiotic resistance typing, and flagellin gene short variable region typing. A phylogeny was constructed by concatenating the seven MLST loci and the hipO locus. ST and clonal complex assignment were performed using only the seven MLST loci. Ciprofloxacin sensitivity was determined by the use of the Etest. Amino acid (FlaA) and nucleotide (flaA) haplotypes (listing of variable sites) are shown for each isolate. STs for FlaA and flaA were assigned in the order of discovery. The dendrogram was constructed using the program MEGA2 (9a).

Second, we examined sequence variation in the flaA short variable region (SVR) of the C. jejuni isolates (14) which identified 82 variable sites, 21 sequence variants (Table 1), and 10 FlaA amino acid sequence variants (Fig. 2). Assigning these sequences to STs, human strains fell into all 10 FlaA STs, while chicken isolates fell into 5 STs, with 8 of 13 in ST-3. The average divergence ± standard error of FlaA among the human isolates (7.6% ± 0.9%) was greater than that of FlaA among chicken isolates (2.2% ± 0.5%). Furthermore, the nonsynonymous base substitution-to-synonymous base substitution ratio for the flaA SVR of the human isolates was 0.177, compared to 0.072 for chicken isolates. The nonsynonymous base substitution-to-synonymous base substitution ratio for all seven MLST loci and hipO was 0.071. Given the overlapping diversity between human and chicken isolates as measured by MLST, increased flagellar diversity may reflect either reduced functional constraints on the protein or increased selection pressure within the human host.

All Campylobacter isolates were tested for sensitivity to ciprofloxacin by Etest (11). Two human C. coli isolates and one chicken isolate were ciprofloxacin resistant. Seven C. jejuni isolates (all from humans) representing 41.2% of human isolates, were ciprofloxacin resistant (Fig. 2). The difference between the rate of ciprofloxacin resistance encountered in chicken and human isolates was statistically significant (P = 0.002; χ2 test).

A portion of the gyrA gene was sequenced for each isolate (17). Nine of 10 ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter strains had a C-to-T transition that codes for the substitution of isoleucine for threonine at position 86 (T86I), the most common mutation found in highly fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter strains (21).

Geographically linked C. jejuni isolates from poultry and humans can have corresponding high rates of quinolone resistance (9, 12). Among our C. jejuni isolates in this study, unexpectedly, none of the chicken isolates was ciprofloxacin resistant, while 7 of the 17 clinical isolates of C. jejuni were ciprofloxacin resistant, in all cases associated with the T86I gyrA amino acid substitution. The treatment of patients with quinolones could select for resistant isolates and drive them to high frequency. Quinolone resistance (via the T86I mutation) can arise rapidly in C. jejuni and C. coli in the gastrointestinal tracts of animals and humans treated with quinolones (2, 6, 20).

In summary, a polyphasic scheme was used to compare the diversity of Campylobacter species isolated from retail poultry and humans with gastroenteritis. MLST analysis of housekeeping genes of C. jejuni strains provides support for the hypothesis that retail chicken products can serve as food reservoirs for C. jejuni that leads to human gastroenteritis. Analysis of potentially variable traits (flagellar typing and antibiotic resistance profiling) suggests that additional selection occurs at some point during the transition from the environmental reservoir and sampling of the human host, perhaps within the gastrointestinal tract of the host itself.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

flaA SVR sequences were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers AY927807 to AY927484, and the partial hipO sequences were submitted under the accession numbers AY944146 to AY944175.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this study were funded with support from the Michigan State University Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases.

We thank Jennifer Ellis-Cortez for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of foodborne illnesses-selected sites, United States, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:340-343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delsol, A. A., J. Sunderland, M. J. Woodward, L. Pumbwe, L. J. Piddock, and J. M. Roe. 2004. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in the native Campylobacter coli population of pigs exposed to enrofloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:872-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, R. Ure, J. A. Wagenaar, B. Duim, F. J. Bolton, A. J. Fox, D. R. Wareing, and M. C. Maiden. 2002. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a basis for epidemiologic investigation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duim, B., P. C. Godschalk, N. van den Braak, K. E. Dingle, J. R. Dijkstra, E. Leyde, J. van der Plas, F. M. Colles, H. P. Endtz, J. A. Wagenaar, M. C. Maiden, and A. van Belkum. 2003. Molecular evidence for dissemination of unique Campylobacter jejuni clones in Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5593-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engberg, J., J. Neimann, E. M. Nielsen, F. M. Aerestrup, and V. Fussing. 2004. Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter infections: risk factors and clinical consequences. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1056-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge, B., D. G. White, P. F. McDermott, W. Girard, S. Zhao, S. Hubert, and J. Meng. 2003. Antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter species from retail raw meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3005-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanninen, M. L., P. Perko-Makela, A. Pitkala, and H. Rautelin. 2000. A three-year study of Campylobacter jejuni genotypes in humans with domestically acquired infections and in chicken samples from the Helsinki area. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1998-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hein, I., C. Schneck, M. Knogler, G. Feierl, P. Plesss, J. Kofer, R. Achmann, and M. Wagner. 2003. Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry and humans in Styria, Austria: epidemiology and ciprofloxacin resistance. Epidemiol. Infect. 130:377-386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linton, D., A. J. Lawson, R. J. Owen, and J. Stanley. 1997. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2568-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luber, P., E. Bartelt, E. Genschow, J. Wagner, and H. Hahn. 2003. Comparison of broth microdilution, E test, and agar dilution methods for antibiotic susceptibility testing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1062-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luber, P., J. Wagner, H. Hahn, and E. Bartelt. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli strains isolated in 1991 and 2001-2002 from poultry and humans in Berlin, Germany. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3825-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning, G., C. G. Dowson, M. C. Bagnall, I. H. Ahmed, M. West, and D. G. Newell. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing for comparison of veterinary and human isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6370-6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meinersmann, R. J., L. O. Helsel, P. I. Fields, and K. L. Hiett. 1997. Discrimination of Campylobacter jejuni isolates by fla gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2810-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neimann, J., J. Engberg, K. Molbak, and H. C. Wegener. 2003. A case-control study of risk factors for sporadic campylobacter infections in Denmark. Epidemiol. Infect. 130:353-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyofo, B. A., S. A. Thornton, D. H. Burr, T. J. Trust, O. R. Pavlovskis, and P. Guerry. 1992. Specific detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli by using polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2613-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piddock, L. J., V. Ricci, L. Pumbwe, M. J. Everett, and D. J. Griggs. 2003. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter species from man and animals: detection of mutations in topoisomerase genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosef, O., G. Kapperud, S. Lauwers, and B. Gondrosen. 1985. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, and Campylobacter laridis from domestic and wild animals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1507-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suerbaum, S., M. Lohrengel, A. Sonnevend, F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Allelic diversity and recombination in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 183:2553-2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Boven, M., K. T. Veldman, M. C. de Jong, and D. J. Mevius. 2003. Rapid selection of quinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni but not in Escherichia coli in individually housed broilers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:719-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zirnstein, G., L. Helsel, Y. Li, B. Swaminathan, and J. Besser. 2000. Characterization of gyrA mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter coli by DNA sequence analysis and MAMA PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]