Abstract

Depression is a common psychiatric symptom among patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), adversely affecting their health. Despite the identification of various contributing factors, the precise mechanisms linking CVD and depression remain elusive. This study conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the association between CVD and depression. Furthermore, a bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis was undertaken to clarify the causal relationship between the two conditions. The meta-analysis included 39 studies, encompassing 63,444 patients with CVD, 12,308 of whom were diagnosed with depression. The results revealed a significant association between CVD and depression or anxiety, with an estimated overall prevalence of depression in CVD patients of 20.8%. Subgroup analyses showed that the prevalence of depression in patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure was 19.8% and 24.7%, respectively. According to a random-effects model, depressive symptoms were linked to an increase in unadjusted all-cause mortality compared with non-depressed patients. The MR analysis, employing the inverse-variance weighted method as the primary tool for causality assessment, identified significant associations between various CVD types and depression or anxiety phenotypes. These findings underscore the significant relationship between CVD and depression or anxiety, leading to an elevated risk of all-cause mortality. Moreover, the MR analysis provides the first genetically-informed evidence suggesting that depression plays a critical role in the development and progression of certain CVD subtypes. This emphasizes the need for addressing depressive symptoms in CVD patients to prevent or reduce adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Subject terms: Depression, Genetics

Introduction

Depression is notably more common among patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) than in the general population, presenting a significant concern that adversely affects both mental and physical health outcomes [1]. A number of meta-analyses have underscored a robust association between CVD and depression [2–6]. Moreover, depression in individuals with CVD is linked to deteriorating health outcomes, including an elevated risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality [1, 7–10]. Contributing factors include unhealthy lifestyle choices, non-compliance with cardiac medications, and direct physiological impacts on the cardiovascular system. While the precise biological mechanisms underpinning these associations are yet to be fully elucidated, several hypotheses have been proposed. These include heightened inflammatory markers, reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, alterations in autonomic nervous system function, changes in platelet function, and gut microbiota, all of which may increase the risk of cardiovascular events in those with depression [11–20]. Consequently, the causal relationship between CVD and depression remains to be conclusively determined.

Over recent decades, epidemiological research, including case-control and cohort studies, has made significant progress in identifying risk factors associated with major diseases, including CVD and its multimorbidities [21–23]. However, epidemiological studies often produce inconsistent results, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), while considered the gold standard for establishing causality, are frequently too costly, time-consuming, or ethically complex to conduct [24]. Additionally, establishing specific causal relationships between risk factors and individual diseases remains challenging within RCT frameworks [25]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shown that many diseases, including CVD, arise from interactions between genetic variants and lifestyle or environmental factors [26, 27]. Based on Mendelian genetic principles, genetic distributions in human populations remain relatively unaffected by most acquired confounding factors.

Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is an epidemiological method utilized to evaluate the causal relationships between modifiable risk factors and health outcomes [28, 29]. It is recognized that genetic predispositions can influence the development and progression of CVD [26, 30]. MR is grounded in three critical assumptions: (1) there is a strong correlation between instrumental variables and the exposure of interest; (2) instrumental variables are not correlated with confounders; and (3) instrumental variables are only associated with the outcome through their effect on the exposure, not directly [31]. The two-sample MR approach estimates the causal impact of an exposure on outcomes using summary data from GWAS [32]. This approach has been extensively applied in the CVD field, including studies on heart failure [33–36]. Nonetheless, the causal link between CVD and depression has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Given the significant impact of CVD and depression on global mortality and morbidity [37], this study aims to provide more definitive evidence of a causal relationship between these conditions, examining how specific CVD subtypes may influence depression. It also highlights the importance of addressing mental health in CVD patients to enhance clinical decision-making, particularly for those with comorbid CVD and depression, to improve overall health outcomes. To achieve these aims, we first conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the global prevalence of depression among individuals with CVD, drawing on data from both population-based and community-based studies, including prospective cohort, follow-up, and longitudinal research. Subsequently, we conducted a two-sample MR analysis using large-scale GWAS data from resources such as FinnGen, the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (CVDKP), the GWAS Catalog, and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) to evaluate the potential causal impact of depression on CVD risk.

Methods

Meta-analysis

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [38], and the study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023484984) [39]. We searched for relevant articles published between 2013 and 2024 in the PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Embase databases to ascertain the global prevalence of depression among patients with CVD (Fig. 1). Our search strategy incorporated a mix of subject headings and free-text terms related to CVD and depression, detailing both the methodology and content of the searches across the different databases (Supplemental Figure S1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection process for meta-analysis.

Selection criteria, data extraction, quality assessment, and statistical analysis

The studies included in the analysis met the following criteria: (1) The study design was either population-based or community-based, encompassing prospective cohort, follow-up, or longitudinal studies. (2) Participants diagnosed with CVD were included, and the studies reported the sample size and prevalence of depression or anxiety among these patients at baseline. (3) Diagnosis of depression or anxiety was based on an established diagnostic system, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV or 5), utilizing diagnostic interviews or validated scales for assessing depression and anxiety. (4) The study included a minimum sample size of 100 participants with CVD.

Studies were excluded if they were: (1) randomized controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, reviews, conference abstracts, or opinion pieces; (2) studies containing duplicate data; (3) studies were published before 2013; or (4) studies lacking raw data or containing non-extractable data.

For this study, two reviewers (JZ and YQ) independently evaluated the quality of the eligible studies and extracted the following information: the first author’s name, year of publication, location of the study, characteristics of the study population at baseline (including gender, mean age, age range), duration of follow-up, the number of cases, CVDs status at baseline, the number of cases with depression or anxiety, the instruments used to measure depression or anxiety, the number of case fatalities, the Hazard Ratio (HR) along the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for depression associated with all-cause mortality.

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [40], which evaluates the risk of bias in cohort studies across three dimensions of quality: selection, comparability, and outcome. The NOS allows for a maximum score of 9, with higher scores indicating higher quality research. Any disagreement between the reviewers regarding a study’s eligibility, data extraction, or quality assessment were resolved through discussion with the third reviewers (YW and LC).

Inter-study heterogeneity was analyzed using the Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic [41]. If the Q-test results in P < 0.05 and I2 ≥ 50%, indicating a high level of heterogeneity, a random-effects model will be employed for the meta-analysis. Conversely, a fixed-effects model will be chosen for lower levels of heterogeneity. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the influence of individual studies on the overall meta-analysis results. EndNote X9 was used for data management and screening. All statistical analyses were performed using the “meta” and “metafor” packages in R software, version 4.3.2.

GWASs-based Mendelian randomization analysis

Study design

To explore the causal relationship between CVD as an exposure and depression or anxiety as an outcome, we employed a two-sample bidirectional MR analysis based on publicly available summary-level datasets from GWASs. The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used as instrumental variables (IVs) were required to satisfy three main criteria: (i) the genetic variations need to be strongly associated with the exposure; (ii) the genetic variations must be independent of any confounding factors; (iii) the genetic variants should not have a direct effect on the outcomes but should influence it only through their association with the exposure. A schematic of the study design is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Mendelian randomization (MR) study design.

I. IVs directly affected exposure. II. IVs were not related to any confounders. III. IVs influenced the risk of outcomes only through exposure, not through other pathways. IVs instrumental variables, SNP single nucleotide polymorphisms, CVD cardiovascular disease, CAD coronary artery disease, MI myocardial infarction, HF heart failure, MDD major depressive disorder.

GWAS data sources

Genetic variants association data for CVD were sourced from FinnGen consortium (https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/data-download), comprising 412,181 samples, including 201,529 cases and 210,652 controls. Genetic IVs for CAD were derived from the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (CVDKP) (https://cvd.hugeamp.org/downloads.html), comprising 210,842 cases and 1167,328 controls [42]. Additionally, genetically associated variants for myocardial infarction (61,505 cases; 577,716 controls) [43], heart failure (115,150 cases; 1550,331 controls) [44], and hypertension (129,909 cases; 354,689 controls) [45] were extracted from the GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). To mitigate bias from population stratification for overlapping individuals in exposure and outcome GWAS used in MR, we selected depression as an outcome variable from a variety of different databases. More specifically, CVD from GWAS dataset of FinnGen was adopted for the exposure, corresponding to major depressive disorder (MDD) from dataset of PGC, which was selected as an outcome. Meanwhile, CAD from CVDPK, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension from GWAS catalog were adopted for the exposure, corresponding to MDD from PGC and depression from FinnGen, which were selected as the outcome. MDD data came from the PGC (https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), with a total of 170,756 cases and 329,443 controls [46, 47]; depression data (47,696 cases and 35,290 controls) were obtained from the FinnGen consortium (https://www.finngen.fi/en/). Anxiety (5580 cases and 11,730 controls) also came from the PGC [48]. Detailed information about the sources of the GWAS datasets is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the GWASs used in this study.

| Phenotype | GWAS datasets | Sample size, N | Cases, n | Controls, n | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | |||||

| CVD | FinnGen | 412,181 | 201,529 | 210,652 | Finland |

| CAD | CVDKP | 1378,170 | 210,842 | 1167,328 | European, East Asian |

| Myocardial Infarction | GWAS Catalog | 639,221 | 61,505 | 577,716 | European |

| Heart Failure | GWAS Catalog | 1665,481 | 115,150 | 1550,331 | African, East Asian, European |

| Hypertension | GWAS Catalog | 484,598 | 129,909 | 354,689 | European |

| Outcome | |||||

| Depression | FinnGen | 406,986 | 47,696 | 35,290 | Finland |

| MDD | PGC | 500,199 | 170,756 | 329,443 | European |

| Anxiety | PGC | 17,310 | 5580 | 11,730 | European |

FinnGen consortium (https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/data-download).

CVDKP: Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (https://cvd.hugeamp.org/downloads.html).

GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/).

PGC: Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downnloads).

GWAS Genome Wide Association Study, CAD cardiovascular disease, CAD cardiovascular artery disease, MDD major depressive disorder.

Selection of the instrumental variables (IVs)

To ensure the reliability of the MR analysis by adhering to its three core assumptions, we conducted a thorough screening process for IVs. Initially, we identified SNPs associated with CVD using a significance threshold of P < 5 × 10−8. If fewer than 3 SNPs were found (P < 5 × 10−8), we relaxed the P-value threshold for SNPs used in the analysis to P < 5 × 10−5 to maximize the number of SNPs in our instrumental variables. Next, the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs was assessed, primarily using an r2 threshold of 0.001 and a physical distance criterion of 10,000 kb [49]. Subsequently, we evaluated the potential for instrumental bias among the selected SNPs by calculating the F statistic for each SNP. The F statistics were derived using the formula F = R2(N−K−1)/K(1−R2), where R2 = 2 × EAF × (1–EAF) × Beta2)/[(2 × EAF × (1–EAF) × Beta2) + (2 × EAF × (1–EAF) × N × SE2)], N is the sample size, K is the number of predictors, Beta is the estimated effect size, and EAF is the effect allele frequency. SNPs with an F statistic value of less than 10 were deemed weak instruments and were excluded from further analysis [50]. Potential confounding factors, including gender, race, physical activity, obesity, body mass index (BMI), HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and dyslipidemia were adjusted using an online tool of LDtrait (https://ldlink.nih.gov/?tab=ldtrait/) [51]. The accession of these confounders is shown in Supplemental Table S4. Finally, we eliminated palindromic SNPs that could lead to ambiguous allelic interpretations in GWAS datasets. The remaining SNPs were meticulously selected as eligible IVs for the analysis.

Statistical analyses of MR analysis

After harmonizing the effect alleles for exposure and outcome from the GWAS, we applied several statistical models to investigate the relationship between CVD and depression or anxiety. These models included the inverse-variance weighted (IVW), weighted median, and MR‐Egger methods, with the IVW method serving as primary analysis technique [52, 53]. Prior to performing MR analysis, we conducted sensitivity analyses to identify and adjust for potential pleiotropy in the causal estimates. The MR-PRESSO (Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier) test was employed to detect outliers among the SNPs that could influence the results [50], with recalibration occurring after outlier removal until the p-value for the global test became non-significant (P > 0.05). Subsequently, the results underwent further verification through MR-Egger intercept tests and a pleiotropy test to detect potential horizontal pleiotropy. Cochrane’s Q test was utilized to assess the heterogeneity among IVs. In the presence of significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05), a random-effects model was used for subsequent analyses; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was adopted.

To address the issue of multiple testing, we applied false discovery rate (FDR) correction to control for false positives. In our study, FDR-corrected P-values (P.FDR) below 0.05 were considered indicative of a significant association, while results with P-values below 0.05 that did not pass FDR correction were regarded as suggestive associations. To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we conducted a leave-one-out analysis to determine if significant results were driven by individual SNPs. Additionally, we used the ‘mr_scatter_plot’ function to generate scatter plots of SNP-exposure and SNP-outcome associations, providing a clear visualization of the MR results.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.2, with the “TwoSampleMR” and “MR-PRESSO” packages facilitating these analyses.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

Initially, a total of 28,894 articles were identified through database searches. After the removal of duplicates and the review of titles and abstracts, 50 full-text articles were shortlisted for eligibility assessment. Among these 50 full-text articles, two were excluded for being irrelevant to the study’s topic and design. Another article was excluded due to an insufficient sample size. Three articles were excluded because their results were not reported. Five articles were excluded for focusing solely on the prevalence of depression. Ultimately, 39 eligible articles were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1) [54–92].

The study primarily analyzed articles published between 2013 and 2024. The majority of these publications originated from the United States, followed by the Netherlands, Japan, and China. In this meta-analysis, a total of 63,444 patients with CVD were involved, of whom 12,308 were diagnosed with depression. The quality of the 39 included papers was evaluated using a quality assessment tool, revealing that the overall quality of the articles was generally high, with most scoring between 7 and 9 points (Supplemental Table S1). The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are detailed in Supplemental Table S2.

Meta-analyses of the prevalence of depression, anxiety and all-cause mortality in CVD patients

In summary, all 39 studies reported the prevalence of depression in patients with CVD. Additionally, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was reported in 10 of these studies, involving 1473 patients out of a total sample size of 6366. Depressive symptoms and all-cause mortality were examined in 15 studies, with a collective sample size of 36,375. Three categories of CVDs were analyzed: coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure, and other forms of CVD. Among the included studies, 19 focused on patients with CAD, covering conditions such as coronary heart disease (CHD), myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and angina pectoris (AP). Sixteen studies focused on patients with heart failure, and 4 studies included patients with other types of CVD.

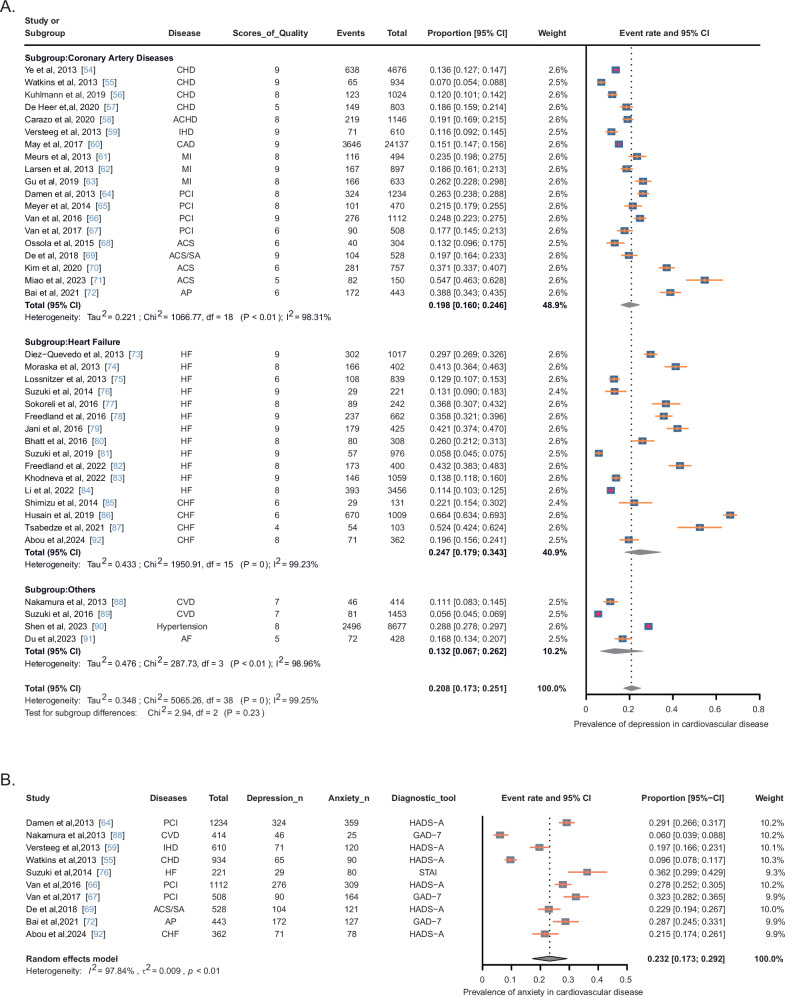

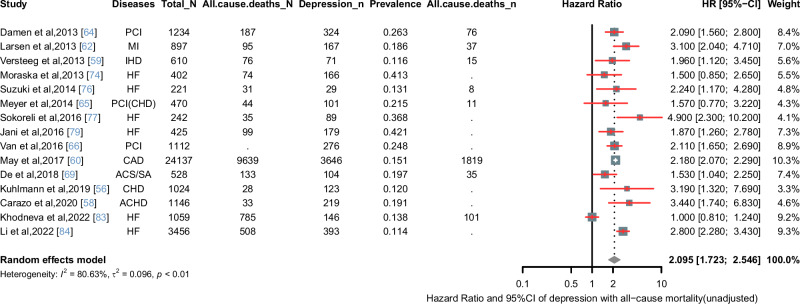

According to the I2 test results, significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies. Consequently, the data were analyzed using a stochastic-effects model. Figure 3A shows the results, indicating that the overall estimated prevalence of depression in patients with CVD was 20.8% (95% CI: 17.3–25.1%). Subgroup analyses revealed that the prevalence of depression was 19.8% (95% CI: 16.0–24.6%) in patients with CAD, and 24.7% (95%CI: 17.9–34.3%) in patients with heart failure. The prevalence of anxiety in patients with CVD was found to be 23.2% (95% CI: 17.3–29.2%) (Fig. 3B). In a random-effect model, depressive symptoms were associated with an increased unadjusted all-cause mortality rate compared with non-depressed patients (HR = 2.095, 95% CI: 1.723–2.546) (Fig. 4). The “leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis indicated that no single study had a disproportionate impact on the overall results when removed from the pooled analysis one at a time (Supplemental Figure S2). Given the substantial heterogeneity in studies of depression prevalence among cardiovascular patients (I2 = 99.25%), we conducted subgroup analyses based on specific disease types, continent, and depression diagnostic scales, as presented in Supplemental Table S3.

Fig. 3. Meta-analyses of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in CVD patients.

A Prevalence of depression in patients with CVD. B Prevalence of anxiety in patients with CVD. ACHD adult congenital heart disease, ACS acute coronary syndrome, ACS/SA acute coronary syndrome/stable angina pectoris, AP angina pectoris, CAD coronary artery disease, CHD coronary heart disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, HF heart failure, CHF chronic heart failure, IHD ischemic heart disease, MI myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CI confidence interval.

Fig. 4. Forest plot of hazard ratio of depression with all-cause mortality.

ACHD adult congenital heart disease, ACS acute coronary syndrome, ACS/SA acute coronary syndrome/stable angina pectoris, AP angina pectoris, CAD coronary artery disease, CHD coronary heart disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, HF heart failure, HR hazard ratio, IHD ischemic heart disease, MI myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CI confidence interval.

MR results

For the phenotypes associated with CVD and depression, we identified 50 MDD-associated and 51 anxiety- associated SNPs after outlier removal via MR-PRESSO and the detection of horizontal pleiotropy. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochrane’s Q-tests to determine the appropriate effect model for the MR analyses. The final results using the IVW method indicated no significant association between CVD and depression or anxiety phenotypes (MDD: OR = 1.003, 95% CI = 0.960–1.047, P = 0.905; anxiety: OR = 1.187, 95% CI = 0.942–1.495, P = 0.146) (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Results of MR analyses.

Causal effects were estimated using primary analysis (IVW), MR-Egger, and weighted median. CVD cardiovascular diseases, MDD major depressive disorder, SNPs single nucleotide polymorphisms, IVW inverse variance weighted, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio. A The forest plot shows the causal relationship between CVD and MDD, anxiety. IVW method indicated no significant association between CVD and MDD phenotypes (OR = 1.003, 95% CI = 0.960–1.047, P = 0.905), CVD and anxiety phenotypes (OR = 1.187, 95% CI = 0.942–1.495, P = 0.146), MR-Egger and weighted median method also showed consistent results. B The forest plot shows the causal association between various CVDs and depression phenotypes. IVW method results revealed significant associations between CAD and MDD (OR = 1.021, 95% CI: 1.001–1.041, P = 0.035), myocardial infarction and depression (OR = 1.038, 95% CI: 1.005–1.072, P = 0.022), heart failure and MDD (OR = 1.064, 95%CI: 1.003–1.129, P = 0.039), and hypertension and depression (OR = 1.517, 95% CI: 1.210–1.903, P < 0.001). C The forest plot of reverse causal effects of depression and anxiety phenotypes on various CVDs. IVW method results revealed significant associations between depression and CAD (OR = 1.183, 95% CI: 1.057–1.325, P = 0.004), depression and myocardial infarction (OR = 1.214, 95% CI: 1.091–1.351, P < 0.001), MDD and CVD (OR = 1.168, 95% CI: 1.073–1.270, P < 0.001), MDD and CAD (OR = 1.337, 95% CI: 1.222–1.462, P < 0.001), MDD and myocardial infarction (OR = 1.281, 95% CI: 1.142–1.438, P < 0.001), MDD and heart failure (OR = 1.107, 95% CI: 1.025–1.196, P = 0.010), MDD and hypertension (OR = 1.013, 95% CI: 1.001–1.025, P = 0.035),and anxiety and heart failure (OR = 1.008, 95% CI: 1.000–1.016, P = 0.048).

However, using the same methods for various CVDs and depression or anxiety phenotypes, the final IVW method results revealed significant associations between CAD and MDD (OR = 1.021, 95% CI: 1.001–1.041, P = 0.035), myocardial infarction and depression (OR = 1.038, 95% CI: 1.005–1.072, P = 0.022), heart failure and MDD (OR = 1.064, 95%CI: 1.003–1.129, P = 0.039), and hypertension and depression (OR = 1.517, 95% CI: 1.210–1.903, P < 0.001). After applying FDR correction, we found that all results showed suggestive associations, except for a significant association between depression and hypertension (Fig. 5B).

We subsequently performed a reverse MR analysis. After removing relevant confounders and excluding palindromic and other SNPs not present in the results, we assessed the causal effects of depression, MDD, and anxiety on various CVDs. Outliers were removed using MR-PRESSO, and horizontal pleiotropy was assessed. Our analysis found strong evidence of causal relationships for the following pairs: depression and CAD (OR = 1.183, 95% CI: 1.057–1.325, P = 0.004), depression and myocardial infarction (OR = 1.214, 95% CI: 1.091–1.351, P < 0.001), MDD and CVD (OR = 1.168, 95% CI: 1.073–1.270, P < 0.001), MDD and CAD (OR = 1.337, 95% CI: 1.222–1.462, P < 0.001), MDD and myocardial infarction (OR = 1.281, 95% CI: 1.142–1.438, P < 0.001), and MDD and heart failure (OR = 1.107, 95% CI: 1.025–1.196, P = 0.010). These associations remained significant after FDR correction. For anxiety, an association with heart failure was initially observed (OR = 1.008, 95% CI: 1.000–1.016, P = 0.048); however, this association was no longer significant after FDR correction (Fig. 5C).

Sensitivity analyses, including the MR-PRESSO global test and the MR-Egger intercept test, were not significant (P > 0.05), suggesting the absence of horizontal pleiotropy. Due to the partial heterogeneity test results (P < 0.05), we adopted the random effects model in the IVW method. The F-statistic was significantly greater than 10, indicating stability in our findings. Results suggested a weak association between an increased risk of various CVDs and a higher risk of depression, but no association with an increased risk of anxiety.

In the reverse analysis, strong evidence indicated a causal relationship between depression and various CVDs, whereas anxiety showed only a weak association with heart failure and no causal relationship with other conditions. All sensitivity analyses and heterogeneity test outcomes are documented in Supplemental Table S5. Finally, the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the MR results, as no individual SNPs significantly influenced the findings when removed (Supplemental Figure S3). Scatter plots visualizing these associations are shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

Discussion

This study provides comprehensive evidence linking CVD with depression using both meta-analysis and MR approaches. The meta-analysis, incorporating 39 studies, revealed that the overall prevalence of depression in patients with CVD is 20.8%, with subgroup analyses showing a prevalence of 19.8% in coronary artery disease and 24.7% in heart failure. Additionally, anxiety was prevalent in 23.2% of CVD patients. Our findings further indicate that depressive symptoms are significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in CVD patients, as determined by a random-effects model. The results of MR analysis did not demonstrate a significant association between CVD and depression phenotypes. However, subsequent results from the IVW method indicated significant associations between MDD and various subtypes of CVD, including CAD, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension. These findings underscore a robust association between CVD and depression.

Our meta-analysis aligns with previous studies that report a strong association between CVD and depression, exacerbating disease progression and mortality risks [2–6]. A prior meta-analysis covering studies from 1966 to 2022 reported a similar association, demonstrating that depressive symptoms increase the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality [5]. The estimated depression prevalence in our study (20.8%) is comparable to the 18.4% prevalence reported in a global systematic review [6]. In this study, subgroup analysis revealed a depression prevalence of 19.8% among CAD patients, aligning with prevalence levels reported in other studies, typically between 15 and 20% for CAD patients [93]. Rutledge et al. [94] also reported an aggregated point estimate for depression in heart failure patients at 21.6%, similar to the 25.1% prevalence observed in heart failure patients in our study. Additionally, the highest anxiety prevalence was reported among cardiac patients in the Americas at 36.8% and among women at 42.3% [95], both higher than this study’s anxiety finding of 23.4%. However, discrepancies exist across populations, with reported depression prevalence reaching as high as 47% in some regions [96]. Such variations may be attributed to differences in diagnostic criteria, healthcare access, and socioeconomic factors.

The observed statistical discrepancies and heterogeneity between this study and others may be due to differences in research methodologies, data collection instruments, sample sizes and characteristics, and variations in the geographical and demographic contexts of each study. For example, a systematic review of biological models found that specific subtypes of depression, rather than a single model of depression, contributed to understanding the bidirectional biological relationship between CVD and depression [97]. A study on two large prospective datasets from the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration and the U.K. Biobank indicated that even baseline depressive symptoms below the threshold for MDD were correlated with the incidence of CVD [98]. In a population-based cohort study, adults with depressive symptoms were found to have an increased risk of developing CVD and mortality, with a stronger effect in urban settings across economically diverse regions [99]. Elevated depressive symptoms, specifically restless sleep and loneliness were also significantly correlated with CVD incidence among middle-aged and older adults in China [100]. In the U.S., women exhibited a higher prevalence of depression, with HR showing significant associations between depression, all-cause mortality, and CVD [101]. Similarly, in China, depression was associated with an increased risk of all-cause and CVD mortality, with a more pronounced effect observed in men [102]. We have also considered the influence of varying sample characteristics, such as age, gender distribution, and other clinical factors, which may affect the CVD-depression relationship and contribute to heterogeneity in meta-analysis results.

Given the high burden of depression and anxiety in CVD patients, incorporating routine mental health screenings into cardiovascular care is imperative in clinical settings [93]. Early detection and intervention for these psychological conditions are crucial in preventing the exacerbation of CVD and improving overall patient outcomes [93, 103]. Collaborative care models that integrate cardiovascular and mental health interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and tailored pharmacological strategies, have the potential to alleviate depressive symptoms and enhance the quality of life for certain individuals with CVD [93, 104, 105]. Thus, the high prevalence of depression and anxiety among CVD patients highlights the importance of routine mental health screening as part of comprehensive cardiovascular care.

Moreover, we employed multiple MR analytical approaches to examine the association between CVD and depression [106]. These included the standard IVW method, which assumes all genetic variants are valid IVs; the weighted median method, which assumes that the majority of genetic variants are valid IVs; and the MR-Egger method, which assumes a plurality of genetic variants as valid IVs. We selected the IVW method as the primary tool for causality assessment due to its higher statistical power under the assumption that all genetic variants are valid instruments. Among the methods, the IVW approach demonstrated the highest statistical power for detecting a causal effect, followed by the weighted median method and MR-Egger regression [107]. However, we acknowledge that the weighted median method may be more robust in the presence of outliers and potential pleiotropy. While IVW is considered the most statistically powerful, it is less robust to outliers and requires all selected SNPs to function as valid instrumental variables [108]. In contrast, the weighted median estimator provides robustness against outliers that deviate from the true causal relationship [109]. Therefore, we used the weighted median method as a complementary approach to validate our findings and assess the influence of pleiotropy on the results.

Our bidirectional MR analysis initially found no significant causal relationship between overall CVD and depression phenotypes. However, further analyses using the IVW method revealed significant associations between depression and specific CVD subtypes, including CAD, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension. Notably, the reverse MR analysis revealed a stronger causal link between depression and various CVDs, particularly CAD, myocardial infarction, and heart failure, with all associations remaining significant after false discovery rate (FDR) correction. A recent MR analysis using data from NHANES 2007–2018 found that genetically determined depression was associated with an increased risk of several CVD types, including coronary heart disease (odds ratio [OR] = 1.14), myocardial infarction (OR = 1.19), atrial fibrillation (OR = 1.14), and stroke (OR = 1.13), but not heart failure [82]. This lack of association with heart failure contrasts with our findings. Consistent with the significant associations observed between MDD and various CVD subtypes in our study, other research has similarly suggested that MDD is associated with higher odds of CAD, myocardial infarction, and heart failure [110, 111]. In contrast, Cao et al. [100] reported that depression itself was not associated with an increased risk of any specific CVD, including arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, CAD, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, or the broader CVD category. However, they found that antidepressant use was correlated with a higher risk across all these cardiovascular conditions [100]. In line with these findings, our MR analysis also did not show a significant association between CVD and depression phenotypes in the overall CVD group, suggesting that this may be due to the mediating effects of antidepressants.

In this study, we also found significant associations between CAD and MDD, myocardial infarction and depression, heart failure and MDD, and hypertension and depression. Although some of these associations are statistically significant, the ORs close to 1 suggest that the practical impact may be limited. However, several additional factors should be considered. The CIs are used as the performance metric, which means that the actual effect size may still hold statistical significance, independent of P-values [112]. Larger effect sizes can be detected in studies with smaller sample sizes, whereas smaller effect sizes require larger sample sizes for reliable detection [113]. The sample size in our study may also influence the observed results. In large-scale public health studies or disease-specific research, and even minor effects can significantly impact population health. For instance, in a pooled analysis of 22 prospective studies with 563,255 participants, Harshfield et al. [98] reported that baseline depressive symptoms were associated with CVD incidence, even at levels below the threshold for MDD. Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms, reducing these symptoms through effective interventions could yield substantial benefits at both population and individual levels. It is important to interpret small effect sizes with caution. We acknowledge the limitations of our study, particularly in detecting and interpreting small effect sizes, and advise cautious interpretation of these findings.

More importantly, horizontal or correlated pleiotropy, confounding genetic associations, and mechanism-specific causal effects may contribute to the heterogeneity observed in MR causal effect estimates [114]. Differences in the characteristics of study populations within the underlying GWAS datasets may also create heterogeneity [115, 116], especially if there are variations in the strength and specificity of genetic instruments used for different exposures. Although MR aims to reduce confounding, unmeasured confounders that vary across studies may still introduce heterogeneity [117]. It is important to note that some degree of heterogeneity in variant-specific estimates is inevitable and should be seen as an opportunity to explore causal mechanisms rather than as an obstacle to MR studies [106]. Therefore, while the random-effects model helps to account for this heterogeneity, it remains essential to interpret the findings with caution, particularly regarding any unmeasured sources of heterogeneity in this study. The lack of a significant association between overall CVD and depressive phenotypes may stem from heterogeneity among CVD subtypes, each with potentially distinct pathophysiological mechanisms and relationships with depression [118, 119]. Additionally, the high polygenicity of depression may obscure specific subtypes with stronger genetic links to CVD [120]. The relationship between CVD and depressive phenotypes might be weaker or more complex than previously thought, requiring larger sample sizes or more precise phenotypic definitions to uncover significant associations.

Additionally, four causal cardiometabolic risk factors, including hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, and prescription of opioid use, were identified as mediators in the relationship between depression and various forms of CVD [121]. Depression can lead to dysregulation of lipid metabolism through mechanisms such as chronic stress and inflammation, resulting in elevated cholesterol levels [122]. This, in turn, increases the risk of atherosclerosis, which is a major contributor to CAD and other CVDs [122]. Depression is also associated with heightened sympathetic nervous system activity and increased circulating stress hormones like cortisol [123, 124], which can contribute to the development and worsening of hypertension—a known risk factor for stroke, heart failure, and other cardiovascular conditions [123–125]. Lu et al. [110] found that a genetic predisposition to depression correlates with a higher risk of CAD and myocardial infarction, partially mediated by type 2 diabetes mellitus and smoking behaviors. Recent studies have shown that cardiometabolic risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, serve as mediators in the relationship between anxiety/depression and CVDs [126]. This association is especially pronounced among younger women and may be driven by neuro-immune pathways related to stress [126]. Prescription opioid use also serves as a mediator, often used to manage pain and anxiety in patients with CVD [127]. Both opioid overdose and withdrawal can precipitate adverse cardiovascular events due to hemodynamic changes, vascular reactions, and proarrhythmic/electrophysiological effects [128]. Moreover, MR analysis has suggested potential causal links between a genetic predisposition to increased prescription opioid use and a heightened risk for MDD, anxiety, and stress-related disorders [129]. Understanding the role of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, and prescription opioid use as mediators allows healthcare providers to adopt more comprehensive treatment strategies that address both mental health and cardiometabolic risk factors, thereby reducing the overall burden of CVD in patients with depression.

Our bidirectional MR analysis also suggests that depression and anxiety may increase the risk of CVD, while CVDs such as CAD, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension may increase the risk of depression, but not anxiety. A large U.K. population-based cohort study indicated that the comorbidity between depression and CHD primarily arises from shared environmental factors [130]. Additionally, biomarkers like interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and triglycerides are likely to have a causal relationship with depression [130]. Growing evidence highlights possible mechanisms by which depression may lead to CVD, including hyperactivation of the inflammatory response, autonomic dysregulation, endothelial dysfunction, abnormal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function, platelet hyperactivation, genetic factors, gut microbiota imbalance, and socio-behavioral factors [122]. Depression is also associated with unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as poor diet, physical inactivity, and substance abuse, all of which are recognized risk factors for CVD [131]. Yang et al. [132] reviewed the mechanisms contributing to depression following myocardial infarction, including serotonin dysfunction, altered HPA axis function, gut microbiota imbalances, exosomal signaling disruptions, and inflammatory processes. In short, these findings suggest that depression may contribute to the development of CVD through mechanisms such as systemic inflammation, autonomic dysfunction, and metabolic disturbances, rather than simply being a consequence of cardiovascular conditions.

Despite employing robust statistical methodologies, our study acknowledges several limitations that warrant cautious interpretation of the results. Firstly, while MR can address some limitations of observational studies and supports causal inference, it relies on assumptions that are difficult to verify. As such, MR can suggest but not definitively establish causality. Secondly, to enhance study power, we used data from the largest available GWAS on CVD and MDD, including resources like FinnGen, CVDKP, GWAS Catalog, and PGC. Despite using large datasets, our sample size may still limit subgroup analyses, potentially affecting the detection of associations, particularly for specific CVD subtypes or depressive phenotypes. Additionally, we recognize limitations inherent in meta-analysis, including the risk of publication bias and heterogeneity among included studies. The quality of the data used, especially from GWAS datasets, may vary. Differences in phenotype definitions and measurement methods across studies can introduce variability, that may affect the robustness of our findings.

Finally, although MR methods are designed to mitigate confounding, population stratification could still introduce bias, especially if there are unmeasured differences in ancestry or environmental exposures across study populations [117]. Additionally, lifestyle and environmental factors—such as diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic status—may confound the relationship between CVD and depression [28, 133, 134]. While MR analysis reduces confounding by using genetic instruments, these factors could still indirectly influence the results. Therefore, future research should address these limitations by incorporating more diverse and larger sample sizes, improving data quality, and further exploring potential confounding factors.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the significant relationship between CVD and depression, highlighting the urgent need for integrated mental and cardiovascular healthcare. The MR findings suggest that depression may contribute to CVD pathogenesis rather than merely being a consequence of cardiovascular conditions. These results emphasize the importance of managing depressive symptoms in CVD patients to prevent adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Future research should further investigate the mechanistic pathways linking these conditions to develop targeted intervention strategies.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grant from Sichuan Science and Technology Program (to Y.W., NO. 2022YFS0617); supported by the joint project of Southwest Medical University and Suining First People’s Hospital (to Y.W., NO. 2023SNXNYD06).

Author contributions

JZ and YQ had full access to all the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. JZ and YQ designed the study, performed the meta-analysis and MR analysis, and drafted the manuscript. CY and XF assisted in data extraction and quality assessment of included studies. XZ and CZ contributed to the interpretation of results and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SZ and YL provided methodological guidance on statistical models and GWAS data interpretation. KH provided oversight, technical support, and contributed to manuscript revision. LC and YW supervised the entire study process, revised the manuscript, YW secured project funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available. Summary-level data for cardiovascular disease (CVD) were obtained from the FinnGen Consortium (https://www.finngen.fi/en), the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (CVDKP, https://cvd.hugeamp.org/downloads.html), and the GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). Summary-level data for major depressive disorder (MDD), depression, and anxiety were obtained from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC, https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/) and FinnGen. All genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets used in Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis are fully accessible to the public. No original individual-level data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Competing interests

Dr. Hashimoto is one of the editorial board members of this journal. Dr. Hashimoto is the inventor of filed patent applications on “The use of R-ketamine in the treatment of psychiatric diseases”, “(S)-norketamine and salt thereof as pharmaceutical”, “R-ketamine and derivative thereof as prophylactic or therapeutic agent for neurodegeneration disease or recognition function disorder”, “Preventive or therapeutic agent and pharmaceutical composition for inflammatory diseases or bone diseases”, “R-ketamine and its derivatives as a preventive or therapeutic agent for a neurodevelopmental disorder”, and “TGF-β1 in the treatment of depression” by Chiba University. Dr. K. Hashimoto has also received speakers’ honoraria, consultant fees, or research support from Otsuka. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study includes a meta-analysis of previously published articles and a Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis based on publicly available genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics. No new human or animal participants were recruited or studied directly by the authors. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All studies included in the meta-analysis had received ethical approval from their respective institutional review boards, and informed consent was obtained from all participants in those original studies. Ethical approval and participant consent for the GWAS datasets used in the MR analysis were obtained by the original investigators. Therefore, no additional ethical approval or informed consent was required for this study.

Footnotes

In this article, the order in which the authors appeared in the author list was incorrectly given as Jun Zeng, Yuting Qiu, Chengying Yang, Xinrong Fan, Xiangyu Zhou, Chunxiang Zhang, Sui Zhu, Yang Long, Yan Wei, Kenji Hashimoto and Lijia Chang where it should have been Jun Zeng, Yuting Qiu, Chengying Yang, Xinrong Fan, Xiangyu Zhou, Chunxiang Zhang, Sui Zhu, Yang Long, Kenji Hashimoto, Lijia Chang, and Yan Wei. The original article has been corrected.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jun Zeng, Yuting Qiu.

Change history

5/9/2025

In this article, the order in which the authors appeared in the author list was incorrectly given as Jun Zeng, Yuting Qiu, Chengying Yang, Xinrong Fan, Xiangyu Zhou, Chunxiang Zhang, Sui Zhu, Yang Long, Yan Wei, Kenji Hashimoto and Lijia Chang where it should have been Jun Zeng, Yuting Qiu, Chengying Yang, Xinrong Fan, Xiangyu Zhou, Chunxiang Zhang, Sui Zhu, Yang Long, Kenji Hashimoto, Lijia Chang, and Yan Wei. The original article has been corrected.

Change history

5/14/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41380-025-03049-2

Contributor Information

Kenji Hashimoto, Email: hashimoto@faculty.chiba-u.jp.

Lijia Chang, Email: changlijia1984@outlook.com.

Yan Wei, Email: weiyan.1111@swmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41380-025-03003-2.

References

- 1.Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:613–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baune BT, Stuart M, Gilmour A, Wersching H, Heindel W, Arolt V, et al. The relationship between subtypes of depression and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of biological models. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan Y, Gong Y, Tong X, Sun H, Cong Y, Dong X, et al. Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krittanawong C, Maitra NS, Qadeer YK, Wang Z, Fogg S, Storch EA, et al. Association of depression and cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2023;136:881–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafiei S, Raoofi S, Baghaei A, Masoumi M, Doustmehraban M, Nejatifar Z, et al. Depression prevalence in cardiovascular disease: global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;13:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, Martire LM, Ariyo AA, Kop WJ. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Honig A, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JT, et al. Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng R, Yu C, Liu N, He M, Lv J, Guo Y, et al. Association of depression with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among adults in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1921043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajan S, McKee M, Rangarajan S, Bangdiwala S, Rosengren A, Gupta R, et al. Association of symptoms of depression with cardiovascular disease and mortality in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:1052–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattina GF, Van Lieshout RJ, Steiner M. Inflammation, depression and cardiovascular disease in women: the role of the immune system across critical reproductive events. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;13:1753944719851950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao M, Lin X, Jiang D, Tian H, Xu Y, Wang L, et al. Depression and cardiovascular disease: shared molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Zhou J, Wang M, Yang C, Sun G. Cardiovascular disease and depression: a narrative review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1274595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto K. Sigma-1 receptor chaperone and brain-derived neurotrophic factor: emerging links between cardiovascular disease and depression. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;100:15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fioranelli M, Roccia MG, Przybylek B, Garo ML. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depression and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Life. 2023;13:1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC. Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:S29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Zhao X, O’Neil A, Turner A, Liu X, Berk M. Altered cardiac autonomic nervous function in depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amadio P, Zara M, Sandrini L, Ieraci A, Barbieri SS. Depression and cardiovascular disease: the viewpoint of platelets. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Zhang X, Wu Z, Huang K, Yang C, Yang L. Brain-heart communication in health and diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2022;183:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang K, Duan J, Wang R, Ying H, Feng Q, Zhu B, et al. Landscape of gut microbiota and metabolites and their interaction in comorbid heart failure and depressive symptoms: a random forest analysis study. mSystems. 2023;8:e0051523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahimi K, Lam CSP, Steinhubl S. Cardiovascular disease and multimorbidity: a call for interdisciplinary research and personalized cardiovascular care. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–e646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the american heart association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wootton RE, Jones HJ, Sallis HM. Mendelian randomisation for psychiatry: how does it work, and what can it tell us? Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes MV, Ala-Korpela M, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization in cardiometabolic disease: challenges in evaluating causality. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:577–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kathiresan S, Srivastava D. Genetics of human cardiovascular disease. Cell. 2012;148:1242–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rom O, Chen YE, Aviram M. Genetic variants associated with cardiovascular diseases and related risk factors highlight novel potential therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2021;32:148–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson SC, Butterworth AS, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: principles and applications. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:4913–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV, Kang H, Morrison J, Munafò MR, et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2022;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tada H, Fujino N, Hayashi K, Kawashiri M-A, Takamura M. Human genetics and its impact on cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol. 2022;79:233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:377–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woolf B, Di Cara N, Moreno-Stokoe C, Skrivankova V, Drax K, Higgins JPT, et al. Investigating the transparency of reporting in two-sample summary data mendelian randomization studies using the MR-Base platform. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:1943–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo S, Au Yeung SL, Zhao JV, Burgess S, Schooling CM. Association of genetically predicted testosterone with thromboembolism, heart failure, and myocardial infarction: mendelian randomisation study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2019;364:l476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry A, Gordillo-Marañón M, Finan C, Schmidt AF, Ferreira JP, Karra R, et al. Therapeutic targets for heart failure identified using proteomics and mendelian randomization. Circulation. 2022;145:1205–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MS, Kim WJ, Khera AV, Kim JY, Yon DK, Lee SW, et al. Association between adiposity and cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational and mendelian randomization studies. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3388–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Peng W, Pang M, Zhu B, Liu H, Hu D, et al. The effects of psychiatric disorders on the risk of chronic heart failure: a univariable and multivariable mendelian randomization study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1306150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao L, Zhang L, Yang C, Wang T, Feng L, Peng C, et al. Sotagliflozin attenuates cardiac dysfunction and depression-like behaviors in mice with myocardial infarction through the gut-heart-brain axis. Neurobiol Dis. 2024;199:106598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aragam KG, Jiang T, Goel A, Kanoni S, Wolford BN, Atri DS, et al. Discovery and systematic characterization of risk variants and genes for coronary artery disease in over a million participants. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1803–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartiala JA, Han Y, Jia Q, Hilser JR, Huang P, Gukasyan J, et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies novel susceptibility loci for myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:919–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levin MG, Tsao NL, Singhal P, Liu C, Vy HMT, Paranjpe I, et al. Genome-wide association and multi-trait analyses characterize the common genetic architecture of heart failure. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dönertaş HM, Fabian DK, Valenzuela MF, Partridge L, Thornton JM. Common genetic associations between age-related diseases. Nat Aging. 2021;1:400–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, Trzaskowski M, Byrne EM, Abdellaoui A, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet. 2018;50:668–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Shirali M, Clarke T-K, Marioni RE, Davies G, et al. Genome-wide association study of depression phenotypes in UK Biobank identifies variants in excitatory synaptic pathways. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otowa T, Hek K, Lee M, Byrne EM, Mirza SS, Nivard MG, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1391–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verbanck M, Chen C-Y, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin SH, Brown DW, Machiela MJ. LDtrait: An online tool for identifying published phenotype associations in linkage disequilibrium. Cancer Res. 2020;80:3443–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. 2018;7:e34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hemani G, Bowden J, Davey Smith G. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:R195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye S, Muntner P, Shimbo D, Judd SE, Richman J, Davidson KW, et al. Behavioral mechanisms, elevated depressive symptoms, and the risk for myocardial infarction or death in individuals with coronary heart disease: the REGARDS (Reason for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:622–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watkins LL, Koch GG, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson JR, O’Connor C, et al. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhlmann SL, Arolt V, Haverkamp W, Martus P, Strohle A, Waltenberger J, et al. Prevalence, 12-month prognosis, and clinical management need of depression in coronary heart disease patients: a prospective cohort study. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88:300–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Heer EW, Palacios JE, Ader HJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Tylee A, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Chest pain, depression and anxiety in coronary heart disease: consequence or cause? a prospective clinical study in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2020;129:109891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carazo MR, Kolodziej MS, DeWitt ES, Kasparian NA, Newburger JW, Duarte VE, et al. Prevalence and prognostic association of a clinical diagnosis of depression in adult congenital heart disease: results of the boston adult congenital heart disease biobank. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Versteeg H, Hoogwegt MT, Hansen TB, Pedersen SS, Zwisler AD, Thygesen LC. Depression, not anxiety, is independently associated with 5-year hospitalizations and mortality in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:518–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.May HT, Horne BD, Knight S, Knowlton KU, Bair TL, Lappe DL, et al. The association of depression at any time to the risk of death following coronary artery disease diagnosis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2017;3:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meurs M, Zuidersma M, Dickens C, de Jonge P. Examining the relation between post myocardial infarction depression and cardiovascular prognosis using a validated prediction model for post myocardial mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larsen KK, Christensen B, Sondergaard J, Vestergaard M. Depressive symptoms and risk of new cardiovascular events or death in patients with myocardial infarction: a population-based longitudinal study examining health behaviors and health care interventions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gu XH, He CJ, Shen L, Han B. Association between depression and outcomes in Chinese patients with myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Damen NL, Versteeg H, Boersma E, Serruys PW, van Geuns RJ, Denollet J, et al. Depression is independently associated with 7-year mortality in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the RESEARCH registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer T, Hussein S, Lange HW, Herrmann-Lingen C. Transient impact of baseline depression on mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease during long-term follow-up. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Dijk MR, Utens EM, Dulfer K, Al-Qezweny MN, van Geuns RJ, Daemen J, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms as predictors of mortality in PCI patients at 10 years of follow-up. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Montfort E, Denollet J, Widdershoven J, Kupper N. Validity of the European society of cardiology’s psychosocial screening interview in patients with coronary artery disease-the THORESCI study. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:404–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ossola P, Paglia F, Pelosi A, De Panfilis C, Conte G, Tonna M, et al. Risk factors for incident depression in patients at first acute coronary syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Jager TAJ, Dulfer K, Radhoe S, Bergmann MJ, Daemen J, van Domburg RT, et al. Predictive value of depression and anxiety for long-term mortality: differences in outcome between acute coronary syndrome and stable angina pectoris. Int J Cardiol. 2018;250:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim JW, Kang HJ, Kim SW, Shin IS, et al. Impact of depression at early and late phases following acute coronary syndrome on long-term cardiac outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:592–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miao X, Chen Y, Qiu X, Wang R. Construction and validation of a nomogram predicting depression risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary stenting: a prospective cohort study. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10:385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bai B, Yin H, Guo L, Ma H, Wang H, Liu F, et al. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety leads to a poor prognosis following angina pectoris patients: a prospective study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diez-Quevedo C, Lupon J, Gonzalez B, Urrutia A, Cano L, Cabanes R, et al. Depression, antidepressants, and long-term mortality in heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND, Vickers KS, Rummans TA, Dunlay SM, et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure: a community study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lossnitzer N, Herzog W, Stork S, Wild B, Muller-Tasch T, Lehmkuhl E, et al. Incidence rates and predictors of major and minor depression in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:502–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki T, Shiga T, Kuwahara K, Kobayashi S, Suzuki S, Nishimura K, et al. Impact of clustered depression and anxiety on mortality and rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. J Cardiol. 2014;64:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sokoreli I, de Vries JJ, Riistama JM, Pauws SC, Steyerberg EW, Tesanovic A, et al. Depression as an independent prognostic factor for all-cause mortality after a hospital admission for worsening heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW, Steinmeyer BC, Skala JA, Davila-Roman VG. Depression and multiple rehospitalizations in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39:257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jani BD, Mair FS, Roger VL, Weston SA, Jiang R, Chamberlain AM. Comorbid depression and heart failure: a community cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhatt KN, Kalogeropoulos AP, Dunbar SB, Butler J, Georgiopoulou VV. Depression in heart failure: can PHQ-9 help? Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suzuki T, Shiga T, Nishimura K, Omori H, Tatsumi F, Hagiwara N. Patient health questionnaire-2 screening for depressive symptoms in Japanese outpatients with heart failure. Intern Med. 2019;58:1689–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Freedland KE, Steinmeyer BC, Carney RM, Skala JA, Chen L, Rich MW. Depression and hospital readmissions in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2022;164:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khodneva Y, Ringel JB, Rajan M, Goyal P, Jackson EA, Sterling MR, et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and all-cause mortality among REGARDS participants with heart failure. Eur Heart J Open. 2022;2:oeac064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li J, Jiang C, Liu R, Lai Y, Li L, Zhao X, et al. Prognostic value of post-discharge depression in patients recently hospitalized with acute heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:858751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shimizu Y, Suzuki M, Okumura H, Yamada S. Risk factors for onset of depression after heart failure hospitalization. J Cardiol. 2014;64:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Husain MI, Chaudhry IB, Husain MO, Abrol E, Junejo S, Saghir T, et al. Depression and congestive heart failure: a large prospective cohort study from Pakistan. J Psychosom Res. 2019;120:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsabedze N, Kinsey JH, Mpanya D, Mogashoa V, Klug E, Manga P. The prevalence of depression, stress and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nakamura S, Kato K, Yoshida A, Fukuma N, Okumura Y, Ito H, et al. Prognostic value of depression, anxiety, and anger in hospitalized cardiovascular disease patients for predicting adverse cardiac outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1432–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Suzuki T, Shiga T, Omori H, Tatsumi F, Nishimura K, Hagiwara N. Depression and outcomes in Japanese outpatients with cardiovascular disease - a prospective observational study. Circ J. 2016;80:2482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shen W, Su Y, Guo T, Ding N, Chai X. The relationship between depression based on patient health questionaire-9 and cardiovascular mortality in patients with hypertension. J Affect Disord. 2024;345:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Du M, Cheng T, Ye Y, Wei Y. Prevalence and risk factors of postprocedure depression in patients with atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation. Cardiol Res Pract. 2023;2023:4635336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abou Kamar S, Oostdijk B, Andrzejczyk K, Constantinescu A, Caliskan K, Akkerhuis KM, et al. Temporal evolution of anxiety and depression in chronic heart failure and its association with clinical outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2024;411:132274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jha MK, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Charney DS, Murrough JW. Screening and management of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1827–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Karami N, Kazeminia M, Karami A, Salimi Y, Ziapour A, Janjani P. Global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in cardiac patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;324:175–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ghaemmohamadi MS, Behzadifar M, Ghashghaee A, Mousavinejad N, Ebadi F, Saeedi Shahri SS, et al. Prevalence of depression in cardiovascular patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000 to 2017. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vogelzangs N, Seldenrijk A, Beekman AT, van Hout HP, de Jonge P, Penninx BW. Cardiovascular disease in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;125:241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harshfield EL, Pennells L, Schwartz JE, Willeit P, Kaptoge S, Bell S, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and incident cardiovascular diseases. JAMA. 2020;324:2396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Santosa A, Rosengren A, Ramasundarahettige C, Rangarajan S, Gulec S, Chifamba J, et al. Psychosocial risk factors and cardiovascular disease and death in a population-based cohort from 21 low-, middle-, and high-Income countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2138920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li H, Zheng D, Li Z, Wu Z, Feng W, Cao X, et al. Association of depressive symptoms with incident cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1916591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang Z, Jackson SL, Gillespie C, Merritt R, Yang Q. Depressive symptoms and mortality among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2337011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu N, Pan XF, Yu C, Lv J, Guo Y, Bian Z, et al. Association of major depression with risk of ischemic heart disease in a mega-cohort of Chinese adults: the China kadoorie biobank study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kovacs AH, Luyckx K, Thomet C, Budts W, Enomoto J, Sluman MA, et al. Anxiety and depression in adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:430–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rollman BL, Anderson AM, Rothenberger SD, Abebe KZ, Ramani R, Muldoon MF, et al. Efficacy of blended collaborative care for patients with heart failure and comorbid depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1369–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wu Y, Yu X, Zhu Y, Shi C, Li X, Jiang R, et al. Integrating depression and acute coronary syndrome care in low resource hospitals in China: the I-CARE randomised clinical trial. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;48:101126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Burgess S, Foley CN, Allara E, Staley JR, Howson JMM. A robust and efficient method for mendelian randomization with hundreds of genetic variants. Nat Commun. 2020;11:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taschler B, Smith SM, Nichols TE. Causal inference on neuroimaging data with mendelian randomisation. Neuroimage. 2022;258:119385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhu X. Mendelian randomization and pleiotropy analysis. Quant Biol. 2021;9:122–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lu Y, Wang Z, Georgakis MK, Lin H, Zheng L. Genetic liability to depression and risk of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and other cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e017986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sui X, Liu T, Liang Y, Zhang B. Psychiatric disorders and cardiovascular diseases: a mendelian randomization study. Heliyon. 2023;9:e20754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lawton M, Ben-Shlomo Y, Gkatzionis A, Hu MT, Grosset D, Tilling K. Two sample mendelian randomisation using an outcome from a multilevel model of disease progression. Eur J Epidemiol. 2024;39:521–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:279–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Darrous L, Hemani G, Davey Smith G, Kutalik Z. PheWAS-based clustering of mendelian randomisation instruments reveals distinct mechanism-specific causal effects between obesity and educational attainment. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Uffelmann E, Huang QQ, Munung NS, de Vries J, Okada Y, Martin AR, et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1:59. [Google Scholar]

- 116.de Leeuw C, Savage J, Bucur IG, Heskes T, Posthuma D. Understanding the assumptions underlying mendelian randomization. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30:653–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bell KJL, Loy C, Cust AE, Teixeira-Pinto A. Mendelian andomization in cardiovascular research: establishing causality when there are unmeasured confounders. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e005623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Xu X, Hua X, Mo H, Hu S, Song J. Single-cell RNA sequencing to identify cellular heterogeneity and targets in cardiovascular diseases: from bench to bedside. Basic Res Cardiol. 2023;118:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Soremekun O, Dib MJ, Rajasundaram S, Fatumo S, Gill D. Genetic heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease across ancestries: insights for mechanisms and therapeutic intervention. Camb Prism Precis Med. 2023;1:e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]