Abstract

A multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme was developed for Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sequences of seven housekeeping genes were obtained for 67 K. pneumoniae strains, including 19 ceftazidime- and ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates. Forty distinct allelic profiles were identified. MLST data were validated against ribotyping and showed high (96%) discriminatory power. The MLST approach provides unambiguous data useful for the epidemiology of K. pneumoniae isolates.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for an important proportion (4 to 8%) of nosocomial infections (14, 24). K. pneumoniae isolates are increasingly resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents, including quinolones (5, 23), and, owing to the production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL), extended-spectrum cephalosporins such as ceftazidime (22). Hospital outbreaks of K. pneumoniae isolates are frequent, and the interhospital dissemination of resistant strains has been described previously (1, 20).

Phenotypic methods developed for typing Klebsiella isolates include phage typing, bacteriocin typing, and serotyping (14). Serotyping of the capsular antigen is valuable for long-term epidemiology and reference typing (4, 16) but may not reflect accurately the genetic relationships among isolates. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis has never been validated for the epidemiology of Klebsiella strains, although the diversity of some housekeeping enzymes has been demonstrated (10, 11, 21).

Molecular methods for characterization of K. pneumoniae isolates used for epidemiological purposes include randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (7), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (1), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (18, 27). However, these methods are mostly used for outbreak investigation at the local level, as their interlaboratory reproducibility is difficult to achieve and as they do not generate highly informative and unambiguous data. Ribotyping is highly reproducible, especially in its automated implementation (3), and was shown to be highly discriminatory in Klebsiella when using EcoRI (1, 7). However, the interpretation of banding pattern variation has both practical and theoretical limitations (15).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is a nucleotide sequence-based method that is adequate for characterizing the genetic relationships among bacterial isolates (12, 13, 19). It provides unambiguous and portable data that allow the implementation of multiuser international databases (17). We report the development of an MLST scheme for K. pneumoniae and its evaluation for characterization of nosocomial isolates.

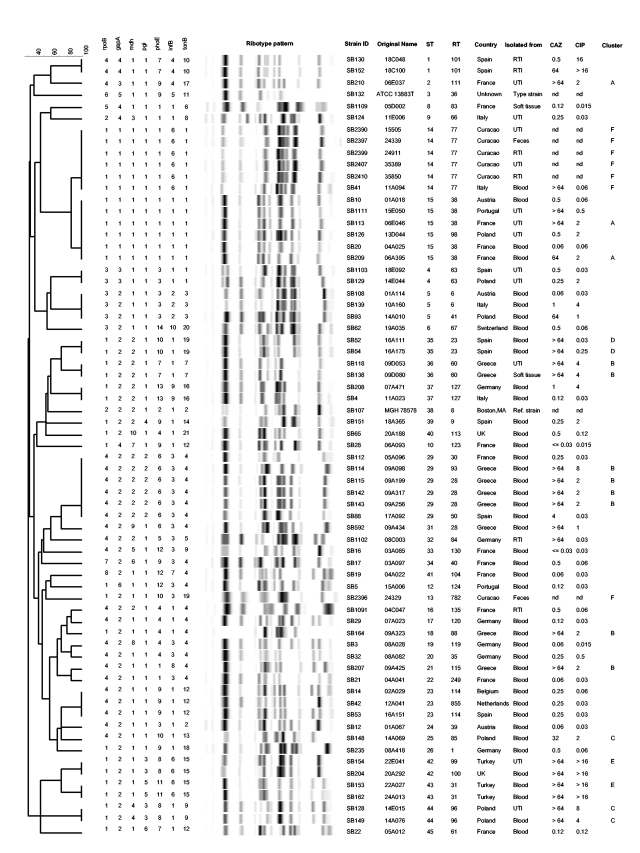

Sixty-seven K. pneumoniae isolates were included. First, 39 clinical isolates that had been collected during the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (5) were selected randomly from different European hospitals and clinical sources. This set of isolates with diverse origins was intended to estimate the discrimination of MLST among strains with no documented epidemiological links. Second, we included 19 additional European isolates that were both ciprofloxacin-resistant (MIC > 2 mg/liter) and ceftazidime-resistant (MIC > 64 mg/liter) (5) and 6 isolates collected during an epidemic of ESBL-producing strains on the Caribbean island Curaçao (28). These 26 strains were included in order to estimate the diversity of genetic backgrounds among multiresistant K. pneumoniae strains. MICs of ceftazidime and ciprofloxacin were taken from a previous study (5). Six epidemic clusters of isolates (clusters A to F in Fig. 1) were suspected when considering the source hospital and the profile of resistance to ciprofloxacin and ceftazidime. Type strain ATCC 13883T and the genome reference strain MGH78578 were included for comparison. The identification of all strains as K. pneumoniae was confirmed by rpoB and/or gyrA gene sequences (2, 6, 7).

FIG. 1.

Allelic profiles, ribotype patterns, sequence type (ST), ribotype (RT), source information, and MIC of ceftazidime (CAZ) and ciprofloxacin (CIP) of the 67 K. pneumoniae strains. The two first letters of the original strain name correspond to the code of the source medical center. Clinical sources were blood, respiratory tract (RTI), urinary tract (UTI), and soft tissue infections. Epidemiological clusters initially suspected on the basis of the medical center and susceptibility to CAZ (resistance breakpoint, 64 mg/liter) and to CIP (resistance breakpoint, 2 mg/liter) are indicated in the last column. All clinical strains were collected between 1997 and 2001. The UPGMA dendrogram was built from the pairwise distances between allelic profiles using BioNumerics.

Primer pairs were designed for PCR amplification and sequencing of internal portions of seven housekeeping genes (Table 1). Genes were selected (i) to be located far apart on the chromosome (Table 1), (ii) based on availability of PCR primers (Table 1), or (iii) for tonB, based on known nucleotide variation (GenBank/EMBL accession numbers AY016749 to AY016767). Other candidate genes were eliminated for technical reasons or to avoid risk of selective bias due to the use of antimicrobial agents (Table 1). Nucleotide sequences were obtained using Big Dye version 3.1 chemistry on an ABI 3700 apparatus. In order to eliminate the risk of sample mix-up, PCR and sequencing were performed using a molecular biology robot (RoboAmp 4200-PE; MWG Biotech, Courtaboeuf, France). Sequence chromatograms were edited and stored using BioNumerics version 4.01 (Applied-Maths, St. Maartens-Latem, Belgium). All nucleotides were supported by at least two sequence chromatograms. A different allele number was given to each distinct sequence within a locus, and a distinct sequence type (ST) number was attributed to each distinct combination of alleles. Allele sequences and STs are available on the public MLST web site at http://pubmlst.org/kpneumoniae.Nucleotide diversity was calculated using DNAsp version 4 (26).

TABLE 1.

Gene loci included in the Klebsiella pneumoniae MLST scheme, PCR and sequencing primers, and variation indices for 67 strainsa

| Locus | Putative function of gene | Primer sequenceb,c | Size (bp) | Locationd | Temp (°C) | No. of alleles | Nucleotide diversity | Polymorphic sites (nonsynonymous substitutions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB | Beta-subunit of RNA polymerase B | VIC3: GGC GAA ATG GCW GAG AAC CA | 501 | 4,771,502-4,772,002 | 50 | 8 | 0.00166 | 7 (1) |

| VIC2: GAG TCT TCG AAG TTG TAA CC | ||||||||

| gapA | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | gapA173: TGA AAT ATG ACT CCA CTC ACG G | 450 | 1,347,540-1,347,091 | 60 | 6 | 0.00136 | 5 (0) |

| gapA181: CTT CAG AAG CGG CTT TGA TGG CTT | ||||||||

| mdh | Malate dehydrogenase | mdh130: CCC AAC TCG CTT CAG GTT CAG | 477 | 4,004,045-4,003,569 | 50 | 10 | 0.00161 | 10 (3) |

| mdh867: CCG TTT TTC CCC AGC AGC AG | ||||||||

| pgi | Phosphoglucose isomerase | pgi1F: GAG AAA AAC CTG CCT GTA CTG CTG GC | 432 | 4,831,091-4,831,522 | 50 | 6 | 0.00092 | 5 (0) |

| pgi1R: CGC GCC ACG CTT TAT AGC GGT TAA T | ||||||||

| pgi2F(seq): CTG CTG GCG CTG ATC GGC AT | ||||||||

| pgi2R(seq): TTA TAG CGG TTA ATC AGG CCG T | ||||||||

| phoE | Phosphoporine E | phoE604.1: ACC TAC CGC AAC ACC GAC TTC TTC GG | 420 | 320,309-320,728 | 50 | 14 | 0.00727 | 18 (2) |

| phoE604.2: TGA TCA GAA CTG GTA GGT GAT | ||||||||

| infB | Translation initiation factor 2 | infB1F: CTC GCT GCT GGA CTA TAT TCG | 318 | 3,937,568-3,937,885 | 50 | 10 | 0.0038 | 11 (0) |

| infB1R: CGC TTT CAG CTC AAG AAC TTC | ||||||||

| infB2F(seq): ACT AAG GTT GCC TCC GGC GAA GC | ||||||||

| tonB | Periplasmic energy transducer | tonB1F: CTT TAT ACC TCG GTA CAT CAG GTT | 414 | 2,394,251-2,394,664 | 45 | 21 | 0.01019 | 14 (5) |

| tonB2R: ATT CGC CGG CTG RGC RGA GAG |

Genes aroA, tyrB, and ureD were also amplified and sequenced successfully but were not included due to lower sequence quality in general. Genes gyrA and parC used previously (7) were excluded as amino acid changes may be selected by the clinical use of quinolones.

Sequencing primers were the same as the PCR primers, except when indicated.

Primer sources were as follows: for mdh, reference 25; for phoE, reference 9; for pgi1F and pgi1R, reference 29; gapA173, reference 8; for rpoB, E. Ageron and P. Grimont, unpublished. All other primers were designed in this study.

Based on the complete sequence of strain MGH78578 available at http://genome.wustl.edu/projects/bacterial/kpneumoniae/.

All seven genes could be PCR amplified for all isolates tested. Nucleotide variation was observed at all genes, with 6 to 21 distinct alleles (Table 1), theoretically allowing more than eight million STs to be distinguished. The seven alleles obtained for genome reference strain MGH78578 were totally identical to the genome sequence at http://genome.wustl.edu. Gene tonB was particular in that two to four codons were deleted in a small number of strains (positions 64 to 69 in strains SB93, SB108, and SB139, positions 83 to 88 in SB1102, and positions 167 to 178 in strain ATCC13883T). The number of variable sites per locus ranged from 5 to 18. The average nucleotide diversity (average number of nucleotide differences per site) was 0.0038. Nonsynonymous substitutions were rare (Table 1), indicating selection against amino acid changes and excluding strong selection bias on the observed allelic diversity, as is typically observed for housekeeping genes.

By combining the seven gene loci, 40 distinct sequence types (STs) were identified. Most groups of strains sharing the same ST belonged to suspected epidemiological clusters (Fig. 1). eBURST analysis (http://eburst.mlst.net/) revealed the existence of two clonal complexes, one including ST14 and ST15, the other including ST16 to -22. When considering only the isolates with no documented epidemiological link, the discriminatory index (Simpson index) was 96%. Therefore, MLST will discriminate most epidemiologically unrelated strains.

In order to further validate the ability of MLST for K. pneumoniae strain characterization, all 67 isolates were analyzed by ribotyping, which is known to be highly discriminatory in this species (1, 7). A total of 46 ribotypes were distinguished. Four STs (ST5, ST15, ST23, and ST42) were subdivided into two ribotype profiles (Fig. 1), whereas ST29 was subdivided into four ribotypes. Importantly, all distinct ribotypes observed within a ST were very similar (Fig. 1), probably reflecting evolution from a common ancestor. In addition, ribotype variation within an ST was consistent with geographic origin and antibiotic resistance data (Fig. 1). Simpson's index, calculated for ribotyping data on the set of isolates with no documented epidemiological link, was 98%.

When considering the 19 ceftazidime- and ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, 11 STs (13 ribotypes) were distinguished. These STs differed among themselves by at least two genes and were distributed across the entire breadth of diversity (Fig. 1), clearly demonstrating that resistance is not restricted to a few genetic backgrounds and that it is a problem of multiple emergence rather than one of interhospital spread of a few clones. This is in agreement with the common view that ESBL plasmids are easily transferred among K. pneumoniae strains and that quinolone resistance can emerge during therapy.

Inspection of the suspected epidemiological clusters in the light of MLST and ribotyping data revealed that all clusters but one (cluster D) proved to be composed of at least two genotypes. In the case of cluster B, four STs were distinguished, with two groups of isolates, plus two single isolates. Thus, MLST will be useful to sort out which cases are caused by clonal spread and which are not. Importantly, the distinct STs within a cluster differed by at least two loci and also showed very distinct ribotype patterns, which excludes ST or ribotype variation being the result of microevolution from a common index case of infection.

Seven STs were observed in distinct countries (Fig. 1). Among these, ST14 corresponded to Curaçao ESBL-producing isolates and a ceftazidime-resistant Italian isolate and ST15 corresponded to ceftazidime-resistant isolates in France, Poland, and Portugal. Both STs may represent resistant K. pneumoniae clones that have spread across countries, possibly mediated by the transfer of hospitalized patients. Alternately, they could result from the independent acquisition of resistance by susceptible genotypes that were initially widespread, as suggested by the finding in different countries of susceptible isolates of ST4, ST5, ST23, and ST37 (Fig. 1).

Combined with precise epidemiological information and the characterization of antibiotic resistance mechanisms, MLST analysis of larger sample sets should provide a much improved understanding of the evolutionary origin and dissemination of K. pneumoniae multiresistant strains.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. Sequences were submitted to EMBL under the numbers AJ890378 to AJ890431 and AJ890476 to AJ890496.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Keith Jolley for making our MLST data publicly available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arlet, G., M. Rouveau, I. Casin, P. J. Bouvet, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1994. Molecular epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains that produce SHV-4 beta-lactamase and which were isolated in 14 French hospitals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2553-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisse, S., and E. Duijkeren. 2005. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of 100 Klebsiella animal clinical isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 105:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brisse, S., V. Fussing, B. Ridwan, J. Verhoef, and R. J. Willems. 2002. Automated ribotyping of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1977-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisse, S., S. Issenhuth-Jeanjean, and P. A. Grimont. 2004. Molecular serotyping of Klebsiella species isolates by restriction of the amplified capsular antigen gene cluster. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3388-3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brisse, S., D. Milatovic, A. C. Fluit, J. Verhoef, and F. J. Schmitz. 2000. Epidemiology of quinolone resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisse, S., T. van Himbergen, K. Kusters, and J. Verhoef. 2004. Development of a rapid identification method for Klebsiella pneumoniae phylogenetic groups and analysis of 420 clinical isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:942-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brisse, S., and J. Verhoef. 2001. Phylogenetic diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca clinical isolates revealed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA, gyrA and parC genes sequencing and automated ribotyping. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:915-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, E. W., R. M. Davis, C. Gouk, and T. van der Zwet. 2000. Phylogenetic relathionships of necrogenic Erwinia and Brenneria species as revealed by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphote dehydrogenase gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:2057-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter, J. S., F. J. Bowden, I. Bastian, G. M. Myers, K. S. Sriprakash, and D. J. Kemp. 1999. Phylogenetic evidence for reclassification of Calymmatobacterium granulomatis as Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1695-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combe, M., J. Lemeland, M. Pestel-Caron, and J. Pons. 2000. Multilocus enzyme analysis in aerobic and anaerobic bacteria using gel electrophoresis-nitrocellulose blotting. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combe, M., J. L. Pons, R. Sesboué, and J. P. Martin. 1994. Electrophoretic transfer from polyacrylamide gel to nitrocellulose sheets, a new method to characterize multilocus enzyme genotypes of Klebsiella strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:26-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1999. Multilocus sequence typing. Trends Microbiol. 7:482-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feil, E. J., B. C. Li, D. M. Aanensen, W. P. Hanage, and B. G. Spratt. 2004. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J. Bacteriol. 186:1518-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimont, F., P. A. D. Grimont, and C. Richard. 1992. The genus Klebsiella, p. 2775-2796. In A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K.-H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, vol. 3. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimont, P. A. D., and F. Grimont. 2001. rRNA gene restriction pattern determination (ribotyping) and computer interpretation, p. 107-133. In L. Dijkshoorn, K. J. Towner, and M. J. Struelens (ed.), New approaches for the generation and analysis of microbial typing data. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 16.Hansen, D. S., R. Skov, J. V. Benedi, V. Sperling, and H. J. Kolmos. 2002. Klebsiella typing: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in comparison with O:K-serotyping. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jolley, K. A., M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2004. mlstdbNet - distributed multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) databases. BMC Bioinformatics 5:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas, D., B. Spitzmüller, F. D. Daschner, J. Verhoef, and S. Brisse. 2004. Discrimination of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca phylogenetic groups and other Klebsiella species by use of AFLP. Res. Microbiol. 155:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monnet, D. L., J. W. Biddle, J. R. Edwards, D. H. Culver, J. S. Tolson, W. J. Martone, F. C. Tenover, and R. P. Gaynes. 1997. Evidence of interhospital transmission of extended-spectrum beta-lactam-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States, 1986 to 1993. The National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance. Syst. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 18:492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nouvellon, M., J. L. Pons, D. Sirot, M. L. Combe, and J. F. Lemeland. 1994. Clonal outbreaks of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae demonstrated by antibiotic susceptibility testing, beta-lactamase typing, and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2625-2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paterson, D. L., W. C. Ko, A. Von Gottberg, S. Mohapatra, J. M. Casellas, H. Goossens, L. Mulazimoglu, G. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, R. A. Bonomo, L. B. Rice, M. M. Wagener, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2004. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in nosocomial infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 140:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paterson, D. L., L. Mulazimoglu, J. M. Casellas, W. C. Ko, H. Goossens, A. Von Gottberg, S. Mohapatra, G. M. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2000. Epidemiology of ciprofloxacin resistance and its relationship to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:473-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenblueth, M., L. Martínez, J. Silva, and E. Martínez-Romero. 2004. Klebsiella variicola, a novel species with clinical and plant-associated isolates. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozas, J., J. C. Sanchez-DelBarrio, X. Messeguer, and R. Rozas. 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19:2496-2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Zee, A., N. Steer, E. Thijssen, J. Nelson, A. van't Veen, and A. Buiting. 2003. Use of multienzyme multiplex PCR amplified fragment length polymorphism typing in analysis of outbreaks of multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:798-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Westreenen, M., A. Paauw, A. C. Fluit, S. Brisse, W. Van Dijk, and J. Verhoef. 2003. Occurrence and spread of SHV extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Curaçao. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:530-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wertz, J. E., C. Goldstone, D. M. Gordon, and M. A. Riley. 2003. A molecular phylogeny of enteric bacteria and implications for a bacterial species concept. J. Evol. Biol. 16:1236-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]