Dear Editor,

Talquetamab is the first FDA approved drug targeting G-protein-coupled receptor class 5 member D (GPRC5D) receptor with a high efficacy and durability of responses in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma (MM). Common side effects include Cytokine Release syndrome (CRS), Immune Effector Cell Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS), oral, skin and gastrointestinal toxicities are well documented. A lesser-known side effect of GPRC5D is a cerebellar toxicity which is independent of ICANS. This was first described with MCARH109 GPRC5D CART where 2 patients (3%) developed a Grade 3 cerebellar disorder [1]. As an extension of this syndrome dizziness can be the first presenting symptom of this neurological disorder. In a subsequent report of Arlo-cel (GPRC5D CART) notable symptoms include dizziness 9%, ataxia 7%, dysarthria 4%, cerebellar toxicity, paresthesia, gait disturbance, and nystagmus were present in 1% [2]. In the prescribing information of talquetamab with European Medical Agency [https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/talvey-epar-product-information_en.pdf] based on MONUMENTAL-1 trial dizziness was present in 12% of patients and 8% had grade 3 dizziness. Herein, we report a case series documenting the clinical course of this dizziness-ataxia syndrome following talquetamab use.

Case 1 is a 65-year-old female with relapsed, refractory MM (RRMM) who was started on talquetamab. The MM was refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, carfilzomib, daratumumab, teclistamab and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) with no evidence of movement and neurocognitive toxicities (MNT) from cilta-cel. She was started on talquetamab and received step up doses on days 1, 3, and 5 and proceeded to the first full dose on day 7. She had a Grade 1 CRS which resolved with one dose of tocilizumab. On day 21, she presented with dizziness and a fall at home. She had a broad-based gait on exam. She also had concomitant oral toxicity and hyponatremia all of which resolved after supportive management and after 2 days of treatment dose dexamethasone but her dizziness and broad-based gait remained. On neurologic examination, cerebellar signs were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal. The dizziness and broad-based gait were attributed to talquetamab and the treatment was permanently discontinued with improvement of these symptoms and signs by day 40. She proceeded to a clinical trial as the next line of treatment.

Case 2 is a 50-year-old male with kappa light chain RRMM and his past medical history was significant that on diagnosis he received radiation therapy in August 2023 for diplopia from a clivus plasmacytoma external to the cavernous sinus with resolution of diplopia and had no further CNS symptoms. On relapse, he proceeded to cilta-cel which was complicated by grade 3 CRS with resolution after tocilizumab and steroids and achieved a complete response. Five months after cilta-cel, the myeloma relapsed with approximately 40% circulating plasma cells, consistent with plasma cell leukemia. He was started on talquetamab developed Grade 2 CRS requiring tocilizumab and dexamethasone with resolution of symptoms and continued with 0.8 mg/kg of talquetamab every 2 weeks. On day 24, the patient presented with diplopia, unsteady gait, and coordination. He underwent MRI Brain and orbits which showed no significant changes compared to the previous examination to the clivus plasmacytoma in January 2024. He also had oral and gastrointestinal toxicity from the talquetamab which included fatigue, decreased oral intake, and diarrhea and improved with supportive care. A neurological examination which was normal with negative cerebellar signs. An ophthalmological examination demonstrated a residual, mild left sixth cranial nerve palsy. He subsequently had falls at home from these symptoms. He was started on low dose dexamethasone for a month with minimal change in symptoms. The talquetamab was permanently discontinued with an improvement in his symptoms, and he proceeded to the next therapy in May 2024.

Case 3 is a 67-year-old female with RRMM who underwent several prior therapies including a prior BCMA and a GPRC5D-targeted CAR T (23 months prior to talquetamab) without any neurologic toxicities. She was started on step up dosing of talquetamab without CRS or ICANS and was maintained on 0.8 mg/kg every two weeks. On Cycle 3 Day 10 she presented with 2 days of dizziness which she described as lightheadedness and not vertiginous. She described her unsteady gait as a persistent feeling of “walking sideways.” Neurological exam was positive for Rhomberg sign and dyskinesia and an MRI Brain was unremarkable, and she was discharged. She received talquetamab on C3D15 and two days later she was again admitted with dizziness. She had GI side effects including nausea and vomiting, EGD was negative, and these symptoms resolved with supportive care. An MRA and an MRI of the neck and brain were negative, including a non-focal neurological examination and negative Barani test (ruling out benign paroxysmal positional vertigo). Her Rhomberg sign was positive. Subsequently, talquetamab was held for 2 months with resolution of symptoms. She was subsequently leukapheresed for ciltacabtagene. After leukapheresis she restarted talquetamab 48 days after her last dose at 0.4 mg/kg every two weeks. There was no recurrence of the symptoms, and she proceeded to cilta-cel infusion.

Case 4 is a 45-year-old male heavily pretreated, non-secretory RRMM, with the last line being cilta-cel. At relapse, he was started on talquetamab and underwent step up without CRS or ICANS and proceeded to a dosing schedule of 0.8 mg/kg every two weeks. On Cycle 1 Day 15, he had evidence of oral toxicity, including Grade 1 xerostomia and dysgeusia. The patient presented on Cycle 2 Day 10 with diplopia and a brain MRI showed a clivus lesion. He received localized radiation and continued talquetamab. A month later, the diplopia returned and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) cytology was positive for plasma cells so he received concurrent intrathecal methotrexate. After a 2 month break, he was re-primed with talq and after 2 cycles, he presented with a few days of dizziness and difficulty walking. The dizziness was not positional and triggered with motion. He received an additional 2 cycles with worsening of his neurologic toxicity to severe truncal ataxia. MRI of the Brain and spine and CSF studies (Table 1), at the time, were unremarkable. Talquetamab was discontinued at this time with resolution of his neurologic symptoms. Because of residual MM and lack of other options, he was cautiously restarted on talquetamab 2 months later. He was re-started on talquetamab 0.6 mg/kg every two weeks and since he had no further dizziness, it was increased to 0.8 mg/kg every three weeks. A month later, he presented with truncal tremor and ataxia. MRI brain and CSF studies were negative. Neurologic evaluation determined that this was cerebellar ataxia related to the talquetamab. Since the patient had limited treatment options, he decided to continue with talquetamab at 0.6 mg every four weeks. Due to transient dizziness, ataxia, and stiffness after every talquetamab dose, the frequency was further reduced to every eight weeks with symptomatic improvement between doses. The myeloma eventually relapsed in the CNS so talquetamab was discontinued.

Table 1.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

| Case | Protein (mg/dL) | Glucose (mg/dL) | Cell Count | Cytology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 77 | 58 | 100 cells: 76 lymphocytes, 24 monocytes/macrophages | + Plasma cells |

In this case series (Table 2), we highlight a challenging and clinically distinct neurotoxicity which presents with dizziness and ataxia after starting talquetamab therapy. Imaging, CSF, and other neurologic studies ruled out other causes of these neurologic manifestations. Characterizing this syndrome is difficult as it does not fit into a distinct cerebellar syndrome and hence can exhibit variation between cerebellar or extrapyramidal manifestations. In case 4, there is a clear relationship with worsening of symptoms every time talquetamab was administered and resolving during the interval between doses. In case 3 when talquetamab was introduced at a lower dose after holding therapy for 2 months, there was no recurrence of symptoms.

Table 2.

Case summaries.

| Case | Age/Sex | Prior BCMA CAR T? | Prior GPRC5D CAR T? | Neurologic Toxicities | Initial dosing* schedule | Dosing* modification | Resolution? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 F | Yes | No | Dizziness, fall | 0.8 Q2W | DC | Improved |

| 2 | 50 M | Yes | No | Dizziness, diplopia, tremors, restlessness, CN 6 palsy | 0.8 Q2W | DC | Improved |

| 3 | 67 F | Yes | Yes | Dizziness, dyskinesia, + Rhomberg | 0.8 Q2W | Held for 2 months followed by 0.4 Q2W | Resolved |

| 4 | 45 M | Yes | No | Diplopia, dizziness, truncal ataxia | 0.8 Q2W | Held for 2 months followed by 0.6 Q4W. | Resolution with DC and recurrence after each dose. |

*Doses are in mg/kg units.

F female, M male, BCMA B-cell maturation antigen, CAR T chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, GPRC5D G-protein-coupled receptor class 5 member D, Q2W every two weeks, QW every week, DC discontinued, CN cranial nerve.

In the Phase 1 MCARH109 trial, two patients out of 17 had grade 3 cerebellar toxicity presenting with wide-based gait, saccadic eye movements with evolution of symptoms to involve appendicular and truncal ataxia and dysarthria. Imaging and CSF studies were negative for any abnormalities but noted low levels of CAR T cells in the CSF [1]. There has been a demonstration of low levels of GPRC5D in the inferior olivary nucleus of the cerebellum which may be the mechanism of toxicity [1]. This toxicity was managed with oral and intravenous glucocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and meclizine with stabilization of symptoms.

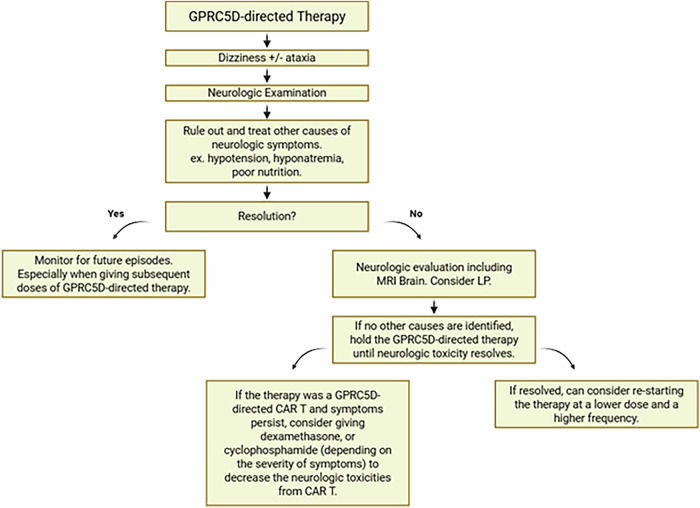

In our case series with Talquetamab, dose interruptions and discontinuations were the most effective strategies to combat these neurologic toxicities. It occurs early in the course of treatment and is associated with dose intensity. Since dizziness and gait imbalance can be common and multifactorial it is important to distinguish them from orthostasis due to oral toxicities. It is plausible that if unrecognized these toxicities might become permanent leading to progressive and permanent cerebellar toxicity. This supports: (1) early identification and recognition of dizziness and ataxia as a distinct syndrome, (2) prompt discontinuation of talquetamab, and (3) cautious re-initiation of therapy (at a lower dose) when symptoms resolve (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Algorithm for management for Dizziness-Ataxia syndrome from GPRC5D-directed therapy.

GPRC5D G-protein-coupled receptor class 5 member D, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, LP lumbar puncture, CAR T chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy.

We postulate that this dizziness-ataxia syndrome is less common but a serious adverse effect with all GPRC5D targeting agents. Due to the paucity of clear cerebellar signs on presentation, we have avoided the term cerebellar toxicity, and would prefer dizziness-ataxia syndrome, so that clinicians don’t wait for cerebellar signs to appear to avoid delays in care. All clinical trials which include GPRC5D should report dizziness-ataxia syndrome or cerebellar syndrome (if cerebellar signs are present) as a toxicity of special interest to compare across the spectrum GPRC5D-directed treatment modalities. Dose discontinuations and modifications leading to symptom resolution should also be reported. Further studies are needed to understand the pathophysiology of this unique syndrome.

Author contributions

MJ and LL were involved in study design, gathering and analysis of data; MJ, LL, SG, AB, SL, NN, MR, FS and MH participated in patient care; MJ and LL wrote the paper.

Competing interests

MJ: Consulting: Janssen, BMS, Legend. Research: Janssen, BMS, Fate Therapeutics. LWL: Received honorarium from MJH Life Sciences, CAHON, and Medscape. Stocks in Roche and Pfizer. Support of attending meetings for DAVA Oncology. SG: consultancy: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Sanofi; research funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen; speaker bureau: Adaptive Biotechnologies, Janssen. AB: Honorarium: Prime Education. Consultant: Janssen. SL: Consultancy: Abbvie, Cellectar, Janssen; Research Funding: BMS. NN: No financial competing interests. MR: Grants from J&J and Pfizer; Speakers Bureau for Janssen and BMS; support of attending meetings for DAVA Oncology; patent vis City of Hope. FS: No financial competing interests. MH: Consulting or Advisory Role: Millennium. Research Funding: Judy and Bernard Briskin Center for Myeloma (Inst), BMS (Inst). Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Millennium.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mailankody S, Devlin SM, Landa J, Nath K, Diamonte C, Carstens EJ, et al. GPRC5D-targeted CAR T cells for myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal S, Htut M, Nadeem O, Anderson LD, Kocoglu H, Gregory T. et al. BMS-986393 (CC-95266), a G protein-coupled receptor class C group 5 member D (GPRC5D)-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): updated results from a phase 1 study. Blood. 2023;142:219. [Google Scholar]