Abstract

Background and Objective

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) being increasingly identified through screening programs. Navigational bronchoscopy, including electromagnetic and robotic-assisted bronchoscopy, is pivotal for biopsying these lesions. However, inconsistent definitions of diagnostic yield (DY) across studies hinder accurate assessment of bronchoscopy performance. This narrative review aims to clarify current DY definitions and advocate for a standardized approach.

Methods

A narrative review of articles from January 2019 to July 2024 was conducted using PubMed, focusing on DY and its calculation in bronchoscopic procedures.

Key Content and Findings

This review highlights significant inconsistencies in DY definitions, with some studies including follow-up assessments and nonspecific benign (NSB) findings, while others only consider immediate specific benign (SB) and malignant results. These discrepancies result in wide-ranging reported DY values, from 26.7% to 97%. Additionally, the review underscores the importance of distinguishing between DY and diagnostic accuracy (DA), as they assess different aspects of procedural performance and should not be used interchangeably. Simulation studies also demonstrate that cancer prevalence and methodological differences in DY calculation substantially affect study outcomes. Standardizing DY as a measure based solely on immediate SB and malignant findings—without follow-up—would allow faster study times and for easier comparison across different studies. Reporting disease prevalence within the study population is highly relevant as higher prevalence may inflate reported DY values.

Conclusions

A standardized, strict definition of DY is crucial for accurately evaluating the diagnostic capacity of bronchoscopy. DY should not be confused with DA, as they measure distinct elements of performance. Adopting a strict definition of DY will enhance the comparability of study results, promote evidence-based decision-making, and help reduce unnecessary procedures while improving the reliability of diagnostic assessments in clinical practice.

Keywords: Diagnostic yield (DY), diagnostic accuracy (DA), navigational bronchoscopy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death. Approximately 340 people die from lung cancer each day (1), disproportionately affecting people with low socioeconomic status in the United States. The economic burden to the health system and out-of-pocket costs associated are exceptionally high (2). Lung cancer screening has been routinely performed since the United States Preventive Services Task Force introduced this recommendation in 2013 for adults (3). Studies have proven its efficacy in reducing lung cancer mortality compared to those who did not undergo screening (4,5). The increasing number of peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) discovered through screening or incidental findings, combined with the need for biopsy to confirm or exclude malignancy (6), has encouraged significant scientific interest in developing new technologies to improve the diagnostic yield (DY) of tissue acquisition techniques. One of the diagnostic procedures for biopsying PPL available is navigational bronchoscopy in its various forms, including electromagnetic, virtual, and robotic-assisted navigation (7).

The approach to diagnostic testing in respiratory medicine varies greatly in terms of methods, definitions, and result reporting (8). Different definitions for DY have been described in research for diverse bronchoscopic procedures despite similar nodule characteristics within their cohorts, which can potentially impact the true performance of these techniques (9). Some definitions require a follow-up period delaying novel research, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses frequently must modify or exclude data to close the gap among the different DY results, making comparisons among studies difficult (10). This is crucial to update knowledge, compare techniques to improve procedural accuracy, and enhance patient care to the best evidence-based practice.

This review examines the recent definitions of DY of PPL in navigational bronchoscopy. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1469/rc).

Methods

We conducted a literature review examining navigational bronchoscopy techniques for pulmonary nodules. Articles published between January 2019 and July 2024 were identified in PubMed using the terms “navigational bronchoscopy”, “diagnostic yield”, “robotic-assisted bronchoscopy”, “diagnostic accuracy”, “lung biopsy”, and “peripheral lung nodule”. We selected only English-language articles. The search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Search strategy summary.

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | 8/1/2024 to 8/20/2024 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed |

| Search terms used | “Navigational bronchoscopy”, “diagnostic yield”, “robotic-assisted bronchoscopy”, “diagnostic accuracy”, “lung biopsy”, “peripheral lung nodule” |

| Timeframe | January 2019 to July 2024 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: original articles including retrospective and prospective studies, simulation-based analysis, meta-analysis, for human studies, in the English language, with a detailed description of the calculation of DY |

| Exclusion criteria: not in the English language. Not report or provided an explanation of the calculation of DY | |

| Selection process | The selection process was conducted by R.F.F. and A.B.R. independently, and later approved by two board-certified interventional pulmonologists. Performed snowballing in the systematic review and meta-analysis articles for research of interest. Consideration for additional studies and review of the final references were performed by all authors |

DY, diagnostic yield.

DY dilemma

This review used the following concepts related to bronchoscopic biopsy results. The clarity of these definitions is essential for understanding and interpreting the term DY.

❖ DY: the proportion of cases in which the test result allows for confident management without additional invasive procedure (11). It is the proportion of patients in whom a diagnostic test detects a disease divided by the total cohort size (12,13), thus, the DY is not disease-specific (8).

❖ Specific benign (SB) finding: nonmalignant result that explains the presence of a PPL, such as granulomatous inflammation, organizing pneumonia, hamartoma, frank purulence, infections, and neutrophilic inflammation (11,14,15).

❖ Nonspecific benign (NSB) finding: nonspecific inflammation or any other finding not entirely explaining the presence of a PPL (11,14,15).

❖ Non-diagnostic (ND): includes atypia (atypical cells insufficient to confirm a malignant diagnosis), normal or benign lung parenchyma/alveoli, blood, and acellular sample (11,14,15).

❖ Diagnostic accuracy (DA): refers to the ability of a test to discriminate between disease and non-disease in a single target condition (15,16). According to the STARD 2015 guidelines, DA reflects a test’s performance within a particular clinical context. Variations in how the index test or reference standard (used to establish the presence or absence of a certain condition) are conducted can lead to differing results (17). This type of metric is disease-specific (8).

By the DY definition, the outcome of a bronchoscopic biopsy could only be classified as either diagnostic or non-diagnostic. However, this binary categorization oversimplifies the reality, as pathologists’ reports are rarely so clear-cut. A pathologist may report malignant, SB, NSB, or ND findings such as atypical cells or normal lung parenchyma (11,14). Upon critical analysis, results like NSB findings, such as inflammation, do not provide enough information to establish a definite diagnosis (16), and therefore, should not be considered in calculating DY.

Different studies assessing the performance of navigational or robotic bronchoscopy have used varying definitions when calculating DY (10,18-27) (Table 2). The inconsistencies in the concept are evident, as some studies consider NSB, atypia, or normal lung parenchyma findings as a nonmalignant diagnosis after a follow-up period, during which imaging or subsequent biopsy confirmed a benign disease. These findings were then included in the DY calculation along with SB and malignant results. Alternatively, other studies calculated DY based solely on SB and malignant findings without considering follow-up evaluations.

Table 2. Review of diagnostic yield definition.

| Author and year | Type of study | DY (%) | M | SB | NSB | AC | NLP | DY calculation methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kops [2023] (9) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 1. 68.6 | 1. D | 1. D | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. (M + SB)/total procedures |

| 2. 72.1 | 2. D | 2. D | 2. D† | 2. ND | 2. ND | 2. (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures | ||

| 3. N/A | 3. D | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP†)/total procedures | ||

| Pyarali [2024] (27) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 81.9 | D | D | ND | ND | ND | (M + SB)/total procedures |

| Ali [2023] (10) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 84.3 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Zhang [2024] (22) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 80.4 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Vachani [2022] (14) | Hypothetical cohort | 1. 66.7 | 1. D | 1. D | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. (M + SB)/total procedures |

| 2. 74.1 | 2. D | 2. D | 2. D† | 2. ND | 2. ND | 2. (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures | ||

| 3A. 87.8 | 3A. D | 3A. D | 3A. D† | 3A. D† | 3A. D† | 3A. (M + SB + NSB + AC + NLP)/total procedures with longitudinal data (excluding LTFU) | ||

| 3B. 79.8 | 3B. D | 3B. D | 3B. D† | 3B. D† | 3B. D† | 3B. (M + SB + NSB + AC + NLP)/total procedures (including LTFU) | ||

| 3C. 88.9 | 3C. D | 3C. D | 3C. D† | 3C. D† | 3C. D† | 3C. (M + SB + NSB + AC + NLP + LTFU)/total procedures | ||

| Vachani [2023] (28) | Simulation based analysis | 1. 53.2 | 1. D | 1. D | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. (M + SB)/total procedures |

| 2. 71.4 | 2. D | 2. D | 2. D | 2. ND | 2. ND | 2. (M + SB + NSB)/total procedures | ||

| 3. 66.5 | 3. D | 3. D | 3. D† | 3. ND | 3. ND | 3. (M + SB + NSB†)/(total procedures – LTFU) | ||

| 4. 89.2 | 4. D | 4. D | 4. D† | 4. D† | 4. D† | 4. (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP†)/(total procedures – LTFU) | ||

| Leonard [2024] (11) | Prospective | 1. 73.6 | 1. D | 1. D | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. (M + SB)/total procedures |

| 2. 87.6 | 2. D | 2. D | 2. D† | 2. ND | 2. ND | 2. (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures | ||

| 3. 100 | 3. D | 3. D | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP†)/total procedures | ||

| 1§. 80.9 | 1‡. D | 1‡. D | 1‡. ND | 1‡. D | 1‡. ND | 1§. (M + SB + AC)/total procedures | ||

| 2§. 94.9 | 2‡. D | 2a. D | 2‡. D† | 2‡. D | 2‡. ND | 2§. (M + SB + NSB† + AC)/total procedures | ||

| 3§. 100 | 3‡. D | 3a. D | 3‡. D† | 3‡. D | 3‡. ND | 3§. (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP† + AC)/total procedures | ||

| Yu Lee-Mateus [2023] (18) | Retrospective | 88.4 | D | D | D† | D† | D† | (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP†)/total procedures |

| Fernandez-Bussy [2024] (19) | Retrospective | 85.7 | D | D | D† | NA | NA | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Fernandez-Bussy [2024] (29) | Retrospective | 83 | D | D | ND | ND | ND | (M + SB)/total procedures |

| Chaddha [2019] (20) | Retrospective | 69.1 | D | D | ND | ND | ND | (M + SB)/total procedures |

| Fernandez-Bussy [2024] (21) | Retrospective | 86.9 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Lee [2024] (23) | Retrospective | 1. 64.2 | 1. D | 1. D | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. ND | 1. (M + SB)/total procedures |

| 2. 64.3 | 2. D | 2. D† | 2. D† | 2. ND | 2. ND | 2. (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures | ||

| 3. 75.4 | 3. D | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. D† | 3. (M + SB + NSB† + AC† + NLP†)/total procedures | ||

| Abia-Trujillo [2024] (24) | Retrospective | 85.4 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Toennesen [2022] (26) | Prospective | 57 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Kheir [2021] (25) | Retrospective | 74.2 | D | D | ND | ND | ND | (M + SB)/total procedures |

| Chen [2021] (30) | Prospective | 74.1 | D | D | D† | ND | ND | (M + SB + NSB†)/total procedures |

| Ost [2016] (31) | Prospective | 53.7 | D | D | ND | ND | ND | (M + SB)/total procedures |

†, considered diagnostic finding if confirmed benign with follow-up or different intervention; ‡, atypical lesions considered as diagnostic; §, if atypical cells are considered diagnostic. AC, atypical cell; D, diagnostic; DY, diagnostic yield; LTFU, lost to follow-up; M, malignancy; NA, not applicable; ND, non-diagnostic; NLP, normal lung parenchyma; NSB, nonspecific benign; SB, specific benign.

The multicenter NAVIGATE study followed a nonmalignant or indeterminate diagnosis for 12 months based on the practitioner’s judgment. Cases where subsequent tests confirmed a nonmalignant diagnosis were considered true negative (TN). This study reported a DY of 72.9% for electromagnetic bronchoscopy navigation biopsy (32). The BENEFIT study, a prospective pilot study of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy (RAB) with the Monarch™ Robotic Endoscopy System, defined TN as a specific benign finding that explained the presence of a PPL. Biopsies showing inflammation were considered TN if subsequent surgical biopsy confirmed the inflammation or follow-up imaging demonstrated resolution at 12 months. This study reported a DY of 74.1% (30). The Acquire Registry study, which assessed the DY of bronchoscopy for PPL, reported an overall DY of 53.7%, as it did not use follow-up and only included cases with a specific malignant or benign diagnosis (31). The heterogeneity of DY definitions challenges the comparison of results. Interestingly, some studies described interchangeably the terms “diagnostic accuracy” and “diagnostic yield” (19), increasing the inconsistency in the terminology. Intuitively, when a subsequent assessment is required to establish a definite diagnosis, studies report DA rather than the immediate DY of the procedure.

While DA provides a summary of the overall test performance, its clinical usefulness is limited, as it condenses critical details—sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values—into a single aggregate metric, potentially obscuring important nuances, overlooking critical information, and possibly leading to incorrect assumptions (16). For example, Abia-Trujillo et al. properly reported the DA of RAB for ground-glass nodules and subsolid nodules with a solid component less than 6 mm, yet they also discussed the valuable details embedded within that single metric (33), needed to completely understand the performance of the RAB in that setting.

Definition of DY

One of the initial steps toward achieving a standardized DY concept is to clearly define what qualifies as an accurate nonmalignant biopsy result. Should all nonmalignant findings, including atypical cells, be considered, or only the SB diagnoses? To address this question Vachani et al. conducted a study using a hypothetical cohort of 1,000 patients describing three different methods to define DY (14).

❖ Strict or conservative method: this method relies solely on the information available at during the index bronchoscopy. Only SB diagnoses are classified as TN, while all other nonmalignant findings are considered non-diagnostic. Therefore, DY is calculated as true positive (TP) + SB divided by total procedures.

❖ Intermediate method: this approach incorporates follow-up data for NSB findings, considering them as TN only if subsequent imaging or biopsy confirms nonmalignant disease in a follow-up period. The DY calculation is then TP + SB + NSB(TN), divided by total procedures.

❖ Liberal method: inclusion of follow-up data for all nonmalignant biopsy results, including ND samples, providing the chance for all the samples to be considered as diagnostic if a subsequent biopsy or imaging evidence a benign disease. DY is calculated by adding TP + SB + NSB(TN) + ND, then dividing this sum by the total number of procedures.

A recent meta-analysis of 95 studies assessing the DY and safety of navigational bronchoscopy reported that DY estimates vary greatly across studies (26.7% to 97%) secondary to the heterogeneity in study methodology. It also showed that the strict DY at the time of the index bronchoscopy for pulmonary nodules <20 mm was lower compared to the DY at 12 months of follow-up (68.6% vs. 72.1%) for the same cohort. Interestingly, this study did not include any research evaluating the DY for RAB using the strict method (9). Follow-up periods should only influence DY calculations in more liberal methodologies. As the strict method categorizes NSB as non-diagnostic, a follow-up period does not alter its classification or impact the subsequent DY calculation. Such non-diagnostic findings should also be considered false negatives (FN) when calculating DA and sensitivity for malignancy (15,34). This is consistent with findings by Fernandez-Bussy et al. [2024], who reported identical DY and DA values after a 6-month follow-up in patients undergoing shape-sensing robotic-assisted bronchoscopy (ssRAB) for cystic and cavitary pulmonary lesions, following the strict methodology and American Thoracic Society (ATS) consensus recommendations (15,29).

Another study assessed the difference between DY and DA by different techniques, including atypical cells. The evidence showed that the conservative method had the lowest discrepancy compared to the intermediate or liberal methods, significantly impacting the results depending on how atypical cell data was managed (11).

The recently published ATS Delphi Consensus on the definition of DY recommends using a strict methodology. According to this approach, the numerator should include only patients with peripheral pulmonary nodules whose biopsy results establish a SB or malignant diagnosis that provides sufficient information to guide patient care. The denominator should encompass all patients who underwent the procedure (15).

Standardizing terminology for nonmalignant results is crucial for achieving a consistent definition and accurate calculation of DY. The studies mentioned above highlight the importance of robust data management, precise definitions, and transparent reporting of results to interpret study outcomes reliably.

Cancer prevalence effect

According to the underlying prevalence of malignant disease, DY will vary significantly (15). A simulation-based analysis of 1,000 bronchoscopies assessed parameters that could affect the DY, categorized by four different definitions (28). In this study, variation in cancer prevalence had the largest effect on DY, with the strict method showing the most significant differences in response to these changes. A higher cancer prevalence increased DY estimates across all methods except the liberal approach. Consequently, the DY reported on studies should be interpreted cautiously, as studies performed in settings with high lung cancer prevalence will likely report a higher DY. This results in potential over- or underestimation of bronchoscopy performance, which should be considered when analyzing study outcomes (28). Therefore, studies should report the prevalence of lung cancer in their cohort to improve the understanding of results and enhance the internal and external validation.

Atypical lesions

Significant gaps remain in establishing a universal approach to terminology, particularly for atypical lesions: Should they be classified as diagnostic or ND findings? Leonard et al. explored further into this issue using the Vachani et al. classification, creating subgroups including atypical cells results (11). Of the 450 specimens included in the study, only 7% corresponded to atypical cells, yet 66.7% were malignant. Interestingly, sensitivity analysis showed that if atypia were always considered diagnostic of malignancy, the study’s navigational bronchoscopy would demonstrate a sensitivity of 91%, specificity of 93%, positive predictive value of 95%, and positive likelihood ratio of 13. Conversely, if atypia were consistently deemed ND, performance would drop to 46%, 94%, 67%, and 7.3, respectively (11).

While the categorization of atypia findings significantly impacts the sensitivity analysis of the tests, it is evident that these results are ND by nature. They require further testing to guide management decisions and, therefore, should not be included in the numerator when calculating DY. Further studies are needed to determine how to properly handle these atypical results when reporting data in scientific articles.

A call to a standardized definition

DY reflects how often bronchoscopy was diagnostic for a range of diseases in that clinical context (8). Therefore, follow-up periods should not be considered when calculating DY. By definition, the conservative/strict method described by Vachani et al. (14) accurately reflects the true meaning of DY, as it evaluates data available at the time of the index bronchoscopy biopsy results. When the use of a reference standard to establishing the presence or absence of a condition is included in a study (17), data should be described as DA, adding sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios as part of the standard report for a specific disease. The recent ATS Consensus recommends a minimum of 12-month clinical or radiographic follow up when reporting sensitivity for malignancy. This follow-up period, however, should not be used to calculate DY, and should be used to calculate the remaining risk of malignancy within non-diagnostic and NSB findings (15). Chae et al. found that including non-diagnostic samples in the calculation of sensitivity of specificity of transthoracic needle biopsy decreased the metric in 4.5 and 10.7%, respectively, and its calculation should be conducted using a 3×2 table where non-diagnostic results are included in the denominator (34). The ATS consensus states that simply excluding these findings is inappropriate and misleading (15).

Summarizing detailed biopsy findings in tables is useful to understand what specific variables are used to calculate each metric. This approach would help researchers avoid using the terms DY and DA interchangeably, thus preventing confusion in interpreting study outcomes. These recommendations align to the ones reported in the literature (8,15), such as a detailed, transparent reporting of results allowing calculation of DY using the strict definition (15).

Researchers should refrain from labeling results as TP or TN for diagnostic values when describing DY. Instead, results should be categorized only as either diagnostic (malignancy and SB findings) or ND values for all others to avoid confusion. This approach ensures that DY reflects the actual diagnostic capacity of a test without the requirements of another intervention since TP or TN entail a subsequent intervention or follow-up to the standard of care to confirm that finding. It is also crucial to explicitly report the prevalence of lung cancer in the study cohort, as it greatly impacts DY. Additionally, the type and size of the PPL, experience of the proceduralists, and biopsy tools should be detailed, as these factors are potential confounders that could influence the outcomes (26). Incorporating these elements is essential for researchers and readers to accurately interpret study outcomes and ensure that findings are reliable and comparable across different studies.

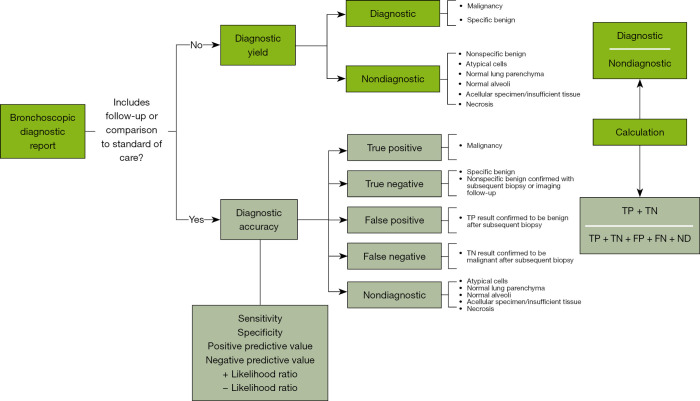

A strict definition of DY might underestimate the true value of the technique, as NSB findings, atypical cells, and normal parenchyma results require an additional follow-up to confirm the benignity of a PPL, and they would be considered as ND at index bronchoscopy. Conversely, a liberal definition could overestimate artificially inflating DY values, leading to confusion in the management of PPL, especially when including ND findings. Physicians are primarily concerned with the clinical usefulness of the data provided by bronchoscopy (16), and it is not enough information to simply have no evidence of malignancy in bronchoscopy; rather, it must be confirmed that the PPL represents something other than lung cancer (11,14,16). Consequently, DY and DA must be clearly distinguished, as they evaluate different components of the procedural performance to reliably guide treatments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bronchoscopic diagnostic report algorithm. FN, false negative; FP, false positive; ND, non-diagnostic; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

Evidence-based decision-making is key to improving the accuracy of diagnosis and reduce the uncertainty of managements. The inconsistency in diagnostic metrics hinders the comparison of studies and limits the effective application of evidence-based strategies in clinical practice (35,36). Standardizing the definition of DY is essential not only for enhancing clinical decisions but also for optimizing patient care. Additionally, such standardization could reduce the economic burden on patients and health systems by minimizing overtreatment and unnecessary procedures. It has been demonstrated that a considerable part of the waste in healthcare spending is attributed to overtreatment in the United States (37). Therefore, achieving reliable bronchoscopic results could enhance DA and management, avoiding costly and redundant interventions.

Efforts to standardize the definitions of DY aim to facilitate the comparison of various techniques for lung nodule assessment across different studies. Our conclusions align with the recent ATS consensus, “Assessment of Advanced Diagnostic Bronchoscopy Outcomes for Peripheral Lung Lesions: A Delphi Consensus Definition of Diagnostic Yield and Recommendations for Patient-centered Study Designs” (15), as well as the STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting DA (17) in lung nodule evaluation. We advocate for consistent reporting of data in accordance with these standards, not only for bronchoscopic techniques but also for other pulmonary diagnostic procedures such as image-guided transthoracic biopsies.

Strengths and limitations

This review aims to summarize the information on DY and critically analyze the current literature directly assessing this topic. We acknowledge the nature of a narrative review may limit an exhaustive systematic review approach, and that studies comparing different definitions of DY are mainly hypothetical cohorts, while the rest of the studies included are mostly retrospective. Prospective and more methodological studies are needed to assess the impact of definitions of DY in clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Across studies of navigational bronchoscopy, significant differences have emerged in the calculation of DY, particularly regarding nonmalignant and ND findings. DY reflects the true diagnostic capacity of a test without requiring further intervention and should be calculated using malignant and SB findings in the numerator, divided by total procedures. This calculation should be clearly differentiated from DA and sensitivity analysis, which are applicable when follow-up is required. A standardized definition of DY is essential to accurately interpret study outcomes, reliably compare the performance of bronchoscopic techniques, and ultimately enhance patient care.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Fayez Kheir) for the series “Advances in Interventional Pulmonary” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1469/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1469/coif). The special series “Advances in Interventional Pulmonary” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. S.F.B. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease from September 2024 to August 2026. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:12-49. 10.3322/caac.21820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kratzer TB, Bandi P, Freedman ND, et al. Lung cancer statistics, 2023. Cancer 2024;130:1330-48. 10.1002/cncr.35128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer VA; U.S. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:330-8. 10.7326/M13-2771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meza R, Jeon J, Toumazis I, et al. Evaluation of the Benefits and Harms of Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography: Modeling Study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021;325:988-97. 10.1001/jama.2021.1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan T, Usman Y, Abdo T, et al. Diagnosis and management of peripheral lung nodule. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:348. 10.21037/atm.2019.03.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer T, Annema JT. Advanced bronchoscopic techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2021;161:152-62. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ost DE, Feller-Kopman DJ, Gonzalez AV, et al. Reporting Standards for Diagnostic Testing: Guidance for Authors From Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2023;30:207-22. 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kops SEP, Heus P, Korevaar DA, et al. Diagnostic yield and safety of navigation bronchoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2023;180:107196. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali MS, Ghori UK, Wayne MT, et al. Diagnostic Performance and Safety Profile of Robotic-assisted Bronchoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023;20:1801-12. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202301-075OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard KM, Low SW, Echanique CS, et al. Diagnostic Yield vs Diagnostic Accuracy for Peripheral Lung Biopsy Evaluation: Evidence Supporting a Future Pragmatic End Point. Chest 2024;165:1555-62. 10.1016/j.chest.2023.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park HY, Suh CH, Kim SO. Use of "Diagnostic Yield" in Imaging Research Reports: Results from Articles Published in Two General Radiology Journals. Korean J Radiol 2022;23:1290-300. 10.3348/kjr.2022.0741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broger T, Marx FM, Theron G, et al. Diagnostic yield as an important metric for the evaluation of novel tuberculosis tests: rationale and guidance for future research. Lancet Glob Health 2024;12:e1184-91. 10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00148-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vachani A, Maldonado F, Laxmanan B, et al. The Impact of Alternative Approaches to Diagnostic Yield Calculation in Studies of Bronchoscopy. Chest 2022;161:1426-8. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.08.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez AV, Silvestri GA, Korevaar DA, et al. Assessment of Advanced Diagnostic Bronchoscopy Outcomes for Peripheral Lung Lesions: A Delphi Consensus Definition of Diagnostic Yield and Recommendations for Patient-centered Study Designs. An Official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians Research Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024;209:634-46. 10.1164/rccm.202401-0192ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez AV, Ost DE, Shojaee S. Diagnostic Accuracy of Bronchoscopy Procedures: Definitions, Pearls, and Pitfalls. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2022;29:290-9. 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012799. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Lee-Mateus A, Reisenauer J, Garcia-Saucedo JC, et al. Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy versus CT-guided transthoracic biopsy for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules. Respirology 2023;28:66-73. 10.1111/resp.14368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Bussy S, Yu Lee-Mateus A, Reisenauer J, et al. Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy versus Computed Tomography-Guided Transthoracic Biopsy for the Evaluation of Subsolid Pulmonary Nodules. Respiration 2024;103:280-8. 10.1159/000538132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaddha U, Kovacs SP, Manley C, et al. Robot-assisted bronchoscopy for pulmonary lesion diagnosis: results from the initial multicenter experience. BMC Pulm Med 2019;19:243. 10.1186/s12890-019-1010-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Bussy S, Garza-Salas A, Barrios-Ruiz A, et al. Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy in the Multiple Pulmonary Nodule Diagnosis during a Single Anesthetic Event. Respiration 2024;103:397-405. 10.1159/000538910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang C, Xie F, Li R, et al. Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorac Cancer 2024;15:505-12. 10.1111/1759-7714.15229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee B, Hwang HS, Jang SJ, et al. Optimal approach for diagnosing peripheral lung nodules by combining electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy and radial probe endobronchial ultrasound. Thorac Cancer 2024;15:1638-45. 10.1111/1759-7714.15376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abia-Trujillo D, Folch EE, Yu Lee-Mateus A, et al. Mobile cone-beam computed tomography complementing shape-sensing robotic-assisted bronchoscopy in the small pulmonary nodule sampling: A multicentre experience. Respirology 2024;29:324-32. 10.1111/resp.14626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kheir F, Thakore SR, Uribe Becerra JP, et al. Cone-Beam Computed Tomography-Guided Electromagnetic Navigation for Peripheral Lung Nodules. Respiration 2021;100:44-51. 10.1159/000510763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toennesen LL, Vindum HH, Risom E, et al. When Pulmonologists Are Novice to Navigational Bronchoscopy, What Predicts Diagnostic Yield? Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12:3127. 10.3390/diagnostics12123127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pyarali FF, Hakami-Majd N, Sabbahi W, et al. Robotic-assisted Navigation Bronchoscopy: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Yield and Complications. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2024;31:70-81. 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vachani A, Maldonado F, Laxmanan B, et al. The Effect of Definitions and Cancer Prevalence on Diagnostic Yield Estimates of Bronchoscopy: A Simulation-based Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023;20:1491-8. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202302-182OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Bussy S, Funes-Ferrada R, Yu Lee-Mateus A, et al. Diagnostic performance of Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted bronchoscopy with mobile Cone-Beam CT for cystic and cavitary pulmonary lesions. Lung Cancer 2024;198:108029. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.108029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen AC, Pastis NJ, Jr, Mahajan AK, et al. Robotic Bronchoscopy for Peripheral Pulmonary Lesions: A Multicenter Pilot and Feasibility Study (BENEFIT). Chest 2021;159:845-52. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic Yield and Complications of Bronchoscopy for Peripheral Lung Lesions. Results of the AQuIRE Registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:68-77. 10.1164/rccm.201507-1332OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folch EE, Pritchett MA, Nead MA, et al. Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy for Peripheral Pulmonary Lesions: One-Year Results of the Prospective, Multicenter NAVIGATE Study. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:445-58. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abia-Trujillo D, Chandra NC, Koratala A, et al. Diagnostic Yield of Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy for Ground-Glass Nodules and Subsolid Nodules with a Solid Component Less than 6 mm. Respiration 2023;102:899-904. 10.1159/000533314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chae KJ, Hong H, Yoon SH, et al. Non-diagnostic Results of Percutaneous Transthoracic Needle Biopsy: A Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019;9:12428. 10.1038/s41598-019-48805-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thammasitboon S, Cutrer WB. Diagnostic decision-making and strategies to improve diagnosis. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2013;43:232-41. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015;351:h5527. 10.1136/bmj.h5527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA 2012;307:1513-6. 10.1001/jama.2012.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]