Abstract

Background

Remnant cholesterol (RC) represents the cholesterol of triglyceride (TG)-rich lipoproteins and is the portion of cholesterol other than both high-density (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Higher RC levels have been associated with heightened inflammation. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been attributed mostly to cigarette smoking or environmental pollution. Disorders of lipid metabolism contribute to inflammation, but no studies have shown an association between RC and COPD. We aimed to investigate the association between RC levels and the pathogenesis of COPD.

Methods

Pooled statistics for the associations between RC and COPD were obtained from published data of individuals of European ancestry, primarily sourced from the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) Open Genome-Wide Association Studies (OpenGWAS) project (including 115,078 European populations) and the FinnGen Biobank (including 16,410 COPD cases and 283,589 controls). To evaluate the causal relationship between RC and COPD, a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis was employed. The primary MR method was inverse variance weighting (IVW). Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using R software.

Results

RC levels were positively associated with COPD risk according to MR analysis [IVW, odds ratio (OR): 1.222, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.092–1.368; P<0.001; MR-Egger, OR: 1.279, 95% CI: 1.065–1.536; P=0.01; weighted median, OR: 1.208, 95% CI: 1.048–1.393; P=0.008]. No significant heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy was detected.

Conclusions

High RC levels might increase the risk of developing COPD. Whether reducing RC levels among the population contributes to a lower risk of COPD remains to be investigated.

Keywords: Remnant cholesterol (RC), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Mendelian randomization (MR), triglycerides (TGs)

Highlight box.

Key findings

• High remnant cholesterol (RC) levels might increase the risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

What is known and what is new?

• It is well known that high levels of total cholesterol are a risk factor for the development of COPD.

• In this paper, we found for the first time that high RC levels might increase the risk of developing COPD, and used Mendelian randomization method to take advantage of the natural random allocation characteristics of genetics, especially the random distribution of single nucleotide polymorphisms. The setting of a randomized controlled trial was simulated to infer potential causal relationships between RC and COPD.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• In this paper, we found that high levels of RC may increase the risk of developing COPD, so we hypothesized that RC-induced COPD is associated with persistent inflammation and that triglycerides in RC lead to increased airway resistance and induce COPD. The results of the current study have two clinical implications. It provides new insights into early clinical screening for COPD and suggests that RC can be used as a screening indicator. Considering the association between high RC levels and COPD prevalence, lifestyle modification is recommended to reduce high RC levels, and several feasible lifestyle modification approaches are also mentioned in the later part of this paper.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous airway disease characterized by persistent and progressive chronic airflow limitation (1,2). COPD has high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide and is among the top three causes of death globally (3). Despite being a preventable and treatable disease, a lack of awareness and effective diagnostic tests other than spirometry could be responsible for the lack of timely and appropriate treatment (2-4). Therefore, accurate diagnosis and treatment are crucial during the early stages of COPD. The pathogenic causes of COPD are multifaceted and include genetic factors, infections, tobacco smoke, and other chronic airway diseases (e.g., asthma) (5). However, the pathogenesis of COPD has not been thoroughly explored.

COPD is an airway disease associated with heightened systemic inflammation (6). Patients have elevated levels of proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein (CRP) (7). Cholesterol is an important driver of systemic inflammation (8). Immune cells (especially macrophages) take up cholesterol and induce cytokine production, while cytokine release induces cholesterol synthesis, and this feedback predisposes to the escalation of inflammatory responses (8). Previous studies regarding the associations between the levels of cholesterol [especially low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)] and the strength of inflammation have largely been conducted in patients with cardiovascular diseases. However, patients with substantially lower LDL-C levels still have a residual elevated risk of serious cardiovascular diseases (9). Moreover, previous studies have indicated a possible role for Remnant cholesterol (RC) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and other conditions (10-12). Several studies have shown a positive correlation between RC levels and the expression of inflammatory biomarkers (13-15). A Mendelian randomization (MR) study found that RC can cause inflammation and multi-layered cellular immune responses in human arterial walls. It revealed that RC particles accumulate in arterial walls and may propagate both local and systemic inflammation (16). Unfortunately, although heightened systemic inflammation is common in respiratory diseases, the association between RC and inflammation in most respiratory diseases has not been explored (17). A recent retrospective study indicated that low-grade inflammation, which is highly related to the level of RC, predicts the severity and risk of death in COVID-19 patients.

The principle underlying these phenomena is that the level of RC in the human body is positively correlated with the expression level of inflammatory biomarkers. COPD is an airway disease related to systemic inflammation (12), and previous studies have mainly focused on the association between LDL-C or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and COPD. We aimed to explore the association between RC levels and the pathogenesis of COPD and to consider whether RC levels can be used to judge the severity of COPD. To address this issue, it is essential to identify the underlying association between RC levels and their major determinants. Genetic factors are the dominant contributors to lipid levels; for instance, up to 40% of the interindividual variations in lipid levels can be explained by genetic factors (18). MR is an analytical method that uses genetic variation as an instrumental variable to investigate potential causal relationships between modifiable exposure factors and outcomes (19,20). Here, we used MR to minimize bias due to confounding and reverse causation (21).

We hypothesized that individuals with a high RC level would have a greater risk of COPD than those with a low or moderate RC level. Therefore, we used RC as an exposure factor and COPD as an outcome and investigated the association by two-sample MR analysis. By focusing on the association between RC and COPD, our findings might help indicate whether early intervention with RC is needed to reduce the incidence of COPD. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE-MR reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1894/rc).

Methods

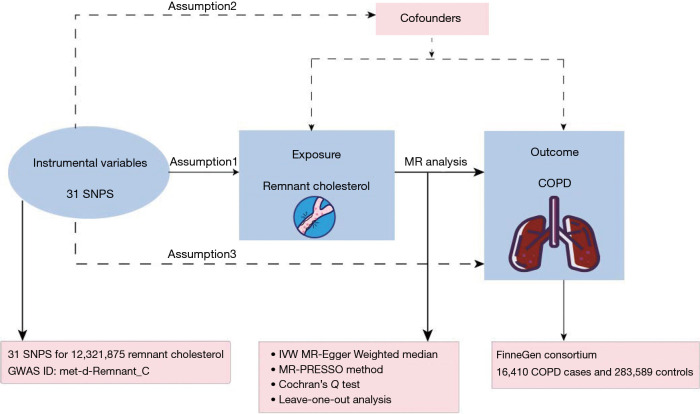

We employed data from European populations obtained from publicly accessible databases [Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and FinnGen], considering RC as an exposure factor and COPD as an outcome, and explored the association through two-sample MR analysis. Firstly, from a 2020 GWAS database of 115,078 European populations including both males and females, 31 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) representing RC were identified. Moreover, a total of 16,410 COPD cases and 283,589 controls were recognized in the FinnGen public database (https://risteys.finregistry.fi/endpoints/J10_COPD). Subsequently, heterogeneity was conducted, followed by MR analysis and sensitivity analysis. The schematic diagram regarding the causal effects of RC and COPD is shown in Figure 1. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Figure 1.

Rationale of two-sample MR concerning the causal effect of RC and COPD. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GWAS, Genome-Wide Association Study; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; RC, respiratory condition; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

GWAS summary data

The OpenGWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) (22) provided the GWAS datasets in the GWAS VCF file format by using the hg19 reference sequences for the GWAS summary data repository (23). We collected RC and COPD data from two large independent cohorts to ensure the consistency of the study population. For the RC data, we obtained information from the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) OpenGWAS project using the met-d-Remnant_C dataset containing 12,321,875 SNPs. The IEU OpenGWAS project cohort comprised 115,078 European participants of both genders. The FinnGen Alliance (https://www.finngen.fi/en/) provided summary-level data for COPD patients. The FinnGen consortium included 16,410 COPD patients and 283,589 non-COPD patients. The data are available at https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/.

SNPs for exposures

Genome-wide significant SNPs were extracted from cohorts of individuals with RC and COPD, there are 12,321,875 SNPs associated with RC in the GWAS database, but there are three core assumptions that must be met for an effective MR analysis: (I) correlation setting: with only the SNPs with P values <5×10−8 being considered significant variants associated with the corresponding phenotype (included for further analysis). When meeting the first major assumption of MR and harmonization, 41 SNPs are first screened out. The specific information is in https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/jtd-24-1894-1.xlsx. (II) Independent setting: thresholds of r2=0.001 and 10,000 kb were used to exclude SNPs via linkage disequilibrium analysis. The above criterion facilitated the deletion of SNPs possessing an r2 value exceeding 0.001 within the 10,000 kb range of the most noteworthy SNP (24). (III) Statistical strength setting: to counteract potential instrumental variable bias, we computed the F-statistics for each SNP and excluded those scoring below 10 (25). An F-statistic below 10 indicates a weak instrumental variable, implying probable bias in the outputs (26). We used LDlink (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/?tab=ldtrait) to identify SNPs associated with confounding (P<1×10−10) and excluded non-conforming SNPs. Finally, 31 SNPS were retained and presented in Table S1.

Statistical analyses

To enhance the robustness of our findings, we employed various MR analysis techniques, such as inverse variance weighting (IVW), constrained Maximum Likelihood and Model Averaging (cML-MA), Mendelian randomization-Egger (MR-Egger), and weighted median, which are designed to infer causality between COPD and RC. Additionally, we utilized various methods, including the MR-Egger intercept test, Cochran’s Q test, and leave-one analysis, to evaluate the existence of pleiotropy and heterogeneity. We integrated Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) and Radial Mendelian Randomization (RadialMR) techniques to identify and eliminate outliers, which led to decreased levels of heterogeneity and pleiotropy (27).

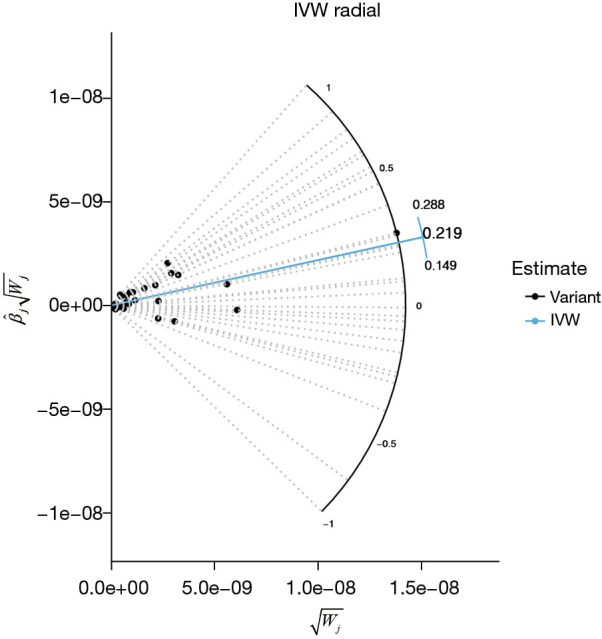

We used MR to investigate the causal relationship between RC and COPD. To assess the causal effect of the exposure on the outcomes, we used Wald ratio, expressed as a single instrumental variable. To combine the estimates of the ratio for each instrument, we used the IVW approach (28). We calculated the effects of individual SNP exposures on the outcomes by using the Wald ratio, followed by combining the effect sizes of individual SNPs based on the IVW. To address the potential bias due to correlation and uncorrelated pleiotropy, we used cML-MA, an MR approach based on cML-MA that is independent of the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (INSIDE) hypothesis (controlling for correlated and uncorrelated pleiotropic effects). The effect of each SNP was assessed with a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, with heterogeneity assessed with the Cochrane Q-value. We also used Egger regression to detect the directional pleiotropy of different genetic variants (29). Horizontal pleiotropy was identified by using the MR-Egger intercept (30). Outliers were removed, and the IVW method was repeated to integrate the effect sizes of each SNP when horizontal pleiotropy was detected (31). Radial plots for all MR analyses are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Radial plots for all MR analyses: abnormal outliers that were not detected by the RadialMR method. Black point usually represents the standard of instrumental variable, the distribution of these points provides overall data, relatively concentrated in the center area of point usually reflects most of the effects of the instrumental variables estimates close to the mean. IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; RadialMR, Radial Mendelian Randomization.

We used the R packages RadialMR, TwoSampleMR, and cML-MA for screening, exclusion, and other statistical analyses (32). The results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) (33) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using R software (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

MR estimates

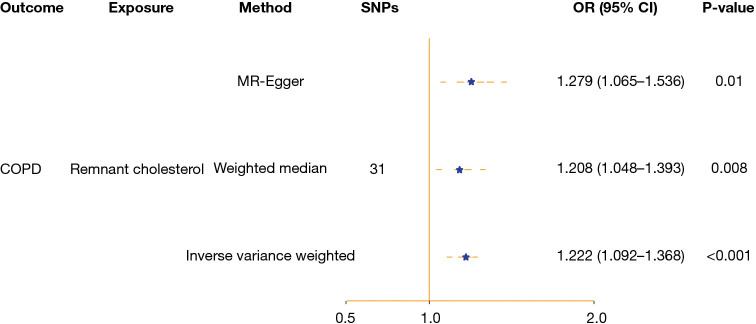

European data based on a total of 16,410 COPD cases and 283,589 controls from the FinnGen public database were recognized. We found a strong correlation between elevated RC levels and the likelihood of developing COPD. According to the IVW analysis, RC levels were positively associated with the risk of COPD. Specifically, for each unit increase in RC, the risk of COPD increased by 22% (OR =1.222, 95% CI: 1.092–1.368; P<0.001). Similar outcomes were obtained with alternative MR models, such as MR-Egger (OR: 1.279, 95% CI: 1.065–1.536; P=0.01) and the weighted median (OR: 1.208, 95% CI: 1.048–1.393; P=0.008), scatter plots for all MR analyses, presented in Figure S1. Forest plots of the results regarding the causal effect of residual cholesterol on COPD risk are presented in Figure 3. The findings obtained through the cML-MA (OR: 1.221, 95% CI: 1.125–1.317; P<0.001) method exhibited strong consistency with the estimates derived from IVW, indicating the lack of pleiotropy in the main analysis.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the results concerning the causal effect of residual cholesterol on the risk of COPD: the OR, 95% CI and P value of IVW, MR-Egger, and weighted median consistently indicated that the higher the remaining cholesterol was, the greater the risk of COPD. CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Sensitivity analyses

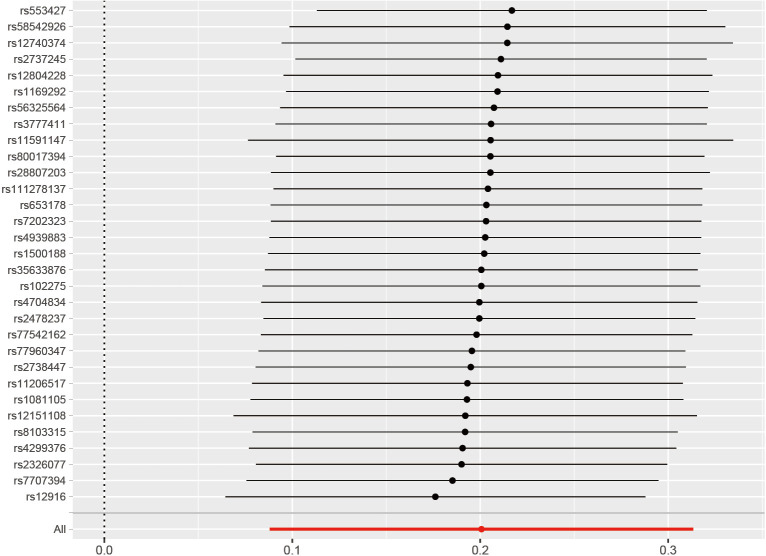

To evaluate the robustness of the aforementioned findings, a set of sensitivity analyses were conducted. These included Cochran’s Q test, MR-Egger intercept test, MR PRESSO, and IVW algorithms. Cochran’s Q test indicated no significant heterogeneity between the genetically predicted RCs and COPD patients (P=0.058 for MR-Egger; P=0.07 for IVW). Leave-one-out plots for all MR analyses are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Leave-one-out plots for all MR analyses indicating that no single SNP drives causal estimates. The red line segment represents the pooled causal effect value of all SNPs, the black line segment represents the recalculated causal effect value after excluding single SNP, and the black point represents the specific value of effect value after SNP exclusion. MR, Mendelian randomization; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

We identified symmetrical funnel plots, presenting in Figure S2, and no horizontal pleiotropy for the MR-Egger intercept test (P=0.054) and MR PRESSO (P=0.10). The “leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis revealed that the instrumental variables did not exert a significant impact on the main analysis. All the MR analysis results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of MR analysis, sensitivity analysis, and validations concerning the causal effect of residual cholesterol on the risk of COPD.

| MR analytical methods | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| IVW | 1.222 (1.092–1.368) | <0.001 |

| MR-Egger | 1.279 (1.065–1.536) | 0.01 |

| Weighted median | 1.208 (1.048–1.393) | 0.008 |

| cML-MA | 1.221 (1.125–1.317) | <0.001 |

| MR-Egger intercept test | 0.054 | |

| MR-PRESSO | 0.10 | |

| RadialMR | No significant outliers | |

| Cochran’s Q | 0.07 |

CI, confidence interval; cML-MA, constrained Maximum Likelihood and Model Averaging; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; OR, odds ratio; PRESSO, Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier; RadialMR, Radial Mendelian Randomization.

Discussion

Our investigation revealed a noteworthy correlation: an elevated level of RC was associated with an increased risk of COPD. The results were robust, and there was no potential bias, as the conclusion also passed the sensitivity analysis.

Our findings support a potential link between RC and COPD risk. Not all studies have reported consistent findings in this regard. For instance, a study conducted in Copenhagen revealed that decreased LDL-C levels were linked to an increased risk of COPD (34,35). Paradoxically, another study reported higher cholesterol levels among patients who had severe COPD (36) While LDL-C appears to be associated with an elevated COPD risk, it is worth noting that the opposite evidence exists, with studies revealing higher cholesterol levels in patients with severe COPD (34,35). This provides a valuable context for our study. However, few studies have explored the relationship between RC and COPD, including studies employing MR statistical approaches. More in-depth analysis is needed to confirm our findings.

Regarding the underlying mechanisms, we have formulated several plausible hypotheses. Upon accumulation, cholesterol can facilitate the formation of specific sterols, such as the liver X receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimer. The dimers play a regulatory role in downregulating cholesterol levels. Paradoxically, the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) inhibits liver X receptor activity on its target genes, causing a reduction in cholesterol efflux from macrophages and an increase in TLR signaling (37). This intricate interplay culminates when inflammatory responses are heightened, as evidenced by an increase in the levels of inflammatory markers, including CRP. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms require further in-depth investigation.

First, we hypothesized that RC-induced COPD was associated with persistent inflammation. Lee et al. demonstrated that the accumulation of macrophages in sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with COPD was positively correlated with disease progression (38). We thus postulated that RC may exert a regulatory effect on the function of macrophages, thereby predisposing them to ongoing inflammation. By highlighting the roles of RC in inflammatory processes (39), Yan et al. showed that RC could stimulate the generation of inflammatory mediators through pathways involving the induction of CD36 receptor clearance and the activation of TLR2 signaling (39). Additionally, the levels of remnant lipids correlated significantly with acute-phase inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity CRP (40). COPD is a chronic inflammatory lung disease that exhibits systemic manifestations involving multiple organ systems, particularly metabolic disorders such as hypertriglyceridemia (41,42). Emerging cross-sectional evidence from 2023 reveals that RC mediates inflammatory pathways associated with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and their co-occurrence (43). These comorbidities substantially complicate the diagnosis and clinical management of COPD. The modulation of RC through targeted interventions has emerged as a promising avenue for the prevention of COPD progression and its multisystem complications.

Second, we hypothesized that triglycerides (TGs) in RC caused increased airway resistance and induced COPD. The RC is defined as a class of cholesterol that is abundant in TG-rich lipoproteins (44). A meta-analysis revealed that, after controlling for other factors influencing serum lipid levels, individuals with COPD exhibited higher levels of TGs than healthy individuals (45). In an observational study conducted in northern India, we discovered that elevated serum TG was a significant characteristic among female patients with COPD (46). Researchers have noted a significant association between serum TG and increased airway resistance in COPD patients. This observation suggests the potential interplay between circulating lipid metabolites and structural components of the lung due to heightened rigidity of the airway parenchyma resulting from intracellular accumulation of esterified or oxidized lipid molecules (47). Additionally, skeletal muscle has an affinity for TG, and studies have demonstrated reduced fat oxidation capacity in the peripheral skeletal muscles of patients with COPD, leading to greater accumulation of TG (48). It is well-documented that exposure to cigarette smoke is a significant risk factor for the development of COPD. Experimental studies have indicated that smoking disrupts cholesterol and bile acid metabolism, and alters gut microbiota composition (49). Notably, smoking cessation has been shown to improve lipid metabolism and respiratory function in COPD patients (50). Elevated cholesterol levels have been observed to exacerbate airway inflammation through epithelial mitochondrial dysfunction. Targeting cholesterol redistribution via the STARD3-MFN2 pathway has been identified as a potential strategy for reducing smoke-induced epithelial damage (34).

Our study offers insights into clinical early screening of COPD. We found that elevated RC levels correlate with increased COPD prevalence, suggesting that RC may serve as a screening indicator. High RC levels detected in clinical practice could facilitate the early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of COPD. Additionally, a retrospective study (12) indicated that RC levels were linked to the severity and mortality of COVID-19, also predicting COPD severity and risk. Research from the University Medical Center of Ljubljana (51) developed a disease severity prediction model based on clinical parameters and sterol subsets, achieving high predictive accuracy [area under the curve (AUC) =0.96]. We propose that our findings can enhance COPD screening efficiency, aid in severity differentiation, and support early prevention strategies.

Furthermore, given the association between high RC levels and COPD prevalence, we recommend lifestyle modifications to reduce RC (52), including smoking cessation, emphasis on management of comorbidities, increased physical activity, weight loss, and adherence to a Mediterranean diet (53). A randomized trial demonstrated that both low glycemic index (GI) diets and low GI Mediterranean diets effectively lowered residual cholesterol levels over 3 and 6 months. While formal guidelines for reducing plasma RC levels are limited, the 2023 European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Atherosclerosis guidelines advocate for medical therapy in high-risk patients with TG levels exceeding 2.3 mmol/L (or 200 mg/dL) (54), COPD mortality was reduced by smoking cessation, management of comorbidities, and reduction of RC with Mediterranean diet.

There are some strengths and limitations in this study. In terms of strengths, our study used MR analysis to examine the association between RC and the incidence of COPD. Compared with conventional observational studies, MR may help mitigate the influence of confounding variables and reverse causality, thereby providing a more robust causal inference. We further limited our study population to individuals of European descent to mitigate the potential bias related to the heterogeneity of the study population. In terms of limitations, firstly, as the GWAS data that we used primarily stemmed from European populations, the generalizability of our findings to other populations remains uncertain. Secondly, the inherent limitations of MR prevent us from eliminating confounding factors, including potential unknown variables that might exert a more substantial influence on COPD severity. Finally, there is not enough research to clarify the mechanism of RC on COPD. Based on the current research, we are more interested in the role of inflammation between RC and COPD.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates a causal link between RC and COPD, highlighting RC as a potential biomarker for COPD risk. It is recommended that future longitudinal studies explore systemic inflammation as a mediator of this association. These findings may guide targeted interventions—such as dietary changes, lipid-lowering therapies, and smoking cessation—to improve RC management and COPD outcomes.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the time and effort given by participants and investigators of the FinnGen and the MRC-IEU consortium.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE-MR reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1894/rc

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation—Outstanding Youth Foundation (No. 82222001 to W.J.G.), and Plan on Enhancing Scientific Research in Guangzhou Medical University (to W.J.G.).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1894/coif). W.J.G. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Celli B, Fabbri L, Criner G, et al. Definition and Nomenclature of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Time for Its Revision. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206:1317-25. 10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J 2023;61:2300239. 10.1183/13993003.00239-2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024;403:2100-32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00367-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD: 2024 Report. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- 5.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765-73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obling N, Backer V, Hurst JR, et al. Nasal and systemic inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Respir Med 2022;195:106774. 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1165-85. 10.1183/09031936.00128008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen SB, Wang H. The shared role of cholesterol in neuronal and peripheral inflammation. Pharmacol Ther 2023;249:108486. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu L, Tai S, Sun J, et al. Remnant Cholesterol and Its Visit-to-Visit Variability Predict Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Findings From the ACCORD Cohort. Diabetes Care 2022;45:2136-43. 10.2337/dc21-2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarese EP, Vine D, Proctor S, et al. Independent Causal Effect of Remnant Cholesterol on Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2023;43:e373-80. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.123.319297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Y, La R, Jiang M, et al. The association between remnant cholesterol and rheumatoid arthritis: insights from a large population study. Lipids Health Dis 2024;23:38. 10.1186/s12944-024-02033-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabre B, Fernandez Machulsky N, Olano C, et al. Remnant cholesterol levels are associated with severity and death in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 2022;12:17584. 10.1038/s41598-022-21177-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Yan K, Zhu P, et al. Association between multiple inflammatory biomarkers and remnant cholesterol levels in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: A large-scale real-world study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2024;34:377-86. 10.1016/j.numecd.2023.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong LF, Yan XN, Lu ZH, et al. Predictive value of non-fasting remnant cholesterol for short-term outcome of diabetics with new-onset stable coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis 2017;16:7. 10.1186/s12944-017-0410-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamano M, Saito M, Eto M, et al. Serum amyloid A, C-reactive protein and remnant-like lipoprotein particle cholesterol in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Biochem 2004;41:125-9. 10.1258/000456304322880005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernelot Moens SJ, Verweij SL, Schnitzler JG, et al. Remnant Cholesterol Elicits Arterial Wall Inflammation and a Multilevel Cellular Immune Response in Humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:969-75. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabe KF, Hurst JR, Suissa S. Cardiovascular disease and COPD: dangerous liaisons? Eur Respir Rev 2018;27:180057. Erratum in: Eur Respir Rev 2018;27:185057. 10.1183/16000617.0057-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matey-Hernandez ML, Williams FMK, Potter T, et al. Genetic and microbiome influence on lipid metabolism and dyslipidemia. Physiol Genomics 2018;50:117-26. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00053.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellingjord-Dale M, Papadimitriou N, Katsoulis M, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of breast cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One 2021;16:e0236904. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sekula P, Del Greco M F, Pattaro C, et al. Mendelian Randomization as an Approach to Assess Causality Using Observational Data. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:3253-65. 10.1681/ASN.2016010098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeung CHC, Schooling CM. Systemic inflammatory regulators and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a bidirectional Mendelian-randomization study. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:829-40. 10.1093/ije/dyaa241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takiishi T, Gysemans C, Bouillon R, et al. Vitamin D and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2010;39:419-46, table of contents. 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyon MS, Andrews SJ, Elsworth B, et al. The variant call format provides efficient and robust storage of GWAS summary statistics. Genome Biol 2021;22:32. 10.1186/s13059-020-02248-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julian TH, Glascow N, Barry ADF, et al. Physical exercise is a risk factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Convergent evidence from Mendelian randomisation, transcriptomics and risk genotypes. EBioMedicine 2021;68:103397. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Q, Yuan S, Yang Q, et al. Causal associations between urinary sodium with body mass, shape and composition: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 2020;10:17475. 10.1038/s41598-020-74657-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer TM, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat Methods Med Res 2012;21:223-42. 10.1177/0962280210394459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Z, Zhang H, Chen K, et al. Iron status and obesity-related traits: A two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:985338. 10.3389/fendo.2023.985338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teumer A. Common Methods for Performing Mendelian Randomization. Front Cardiovasc Med 2018;5:51. 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, et al. Sensitivity Analyses for Robust Causal Inference from Mendelian Randomization Analyses with Multiple Genetic Variants. Epidemiology 2017;28:30-42. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:377-89. Erratum in: Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:391-2. 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Yang H, Li H, et al. Insights into modifiable risk factors of cholelithiasis: A Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology 2022;75:785-96. 10.1002/hep.32183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 2018;7:e34408. 10.7554/eLife.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorsteinsdottir F, Cardoso I, Keller A, et al. Neonatal Vitamin D Status and Risk of Asthma in Childhood: Results from the D-Tect Study. Nutrients 2020;12:842. 10.3390/nu12030842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Liu Y, Liu X, et al. Regulatory roles of external cholesterol in human airway epithelial mitochondrial function through STARD3 signalling. Clin Transl Med 2022;12:e902. 10.1002/ctm2.902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafirova-Ivanovska B, Stojkovikj J, Dokikj D, et al. The Level of Cholesterol in COPD Patients with Severe and Very Severe Stage of the Disease. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2016;4:277-82. 10.3889/oamjms.2016.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freyberg J, Landt EM, Afzal S, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of COPD: Copenhagen General Population Study. ERJ Open Res 2023;9:00496-2022. 10.1183/23120541.00496-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:104-16. 10.1038/nri3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JW, Chun W, Lee HJ, et al. The Role of Macrophages in the Development of Acute and Chronic Inflammatory Lung Diseases. Cells 2021;10:897. 10.3390/cells10040897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan J, Horng T. Lipid Metabolism in Regulation of Macrophage Functions. Trends Cell Biol 2020;30:979-89. 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izumida T, Nakamura Y, Hino Y, et al. Combined Effect of Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (sdLDL-C) and Remnant-Like Particle Cholesterol (RLP-C) on Low-Grade Inflammation. J Atheroscler Thromb 2020;27:319-30. 10.5551/jat.49528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariniello DF, D'Agnano V, Cennamo D, et al. Comorbidities in COPD: Current and Future Treatment Challenges. J Clin Med 2024;13:743. 10.3390/jcm13030743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu TD, Fawzy A, Brigham E, et al. Association of Triglyceride-Glucose Index and Lung Health: A Population-Based Study. Chest 2021;160:1026-34. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y, Wei Q, Li H, et al. Association of remnant cholesterol with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and their coexistence: the mediating role of inflammation-related indicators. Lipids Health Dis 2023;22:158. 10.1186/s12944-023-01915-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stürzebecher PE, Katzmann JL, Laufs U. What is 'remnant cholesterol'? Eur Heart J 2023;44:1446-8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xuan L, Han F, Gong L, et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and serum lipid levels: a meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis 2018;17:263. 10.1186/s12944-018-0904-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy R, Gautam AK, Singh NP, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Its Correlates Among Female Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients at a Rural Tertiary Health Care Center in Northern India. Cureus 2022;14:e28611. 10.7759/cureus.28611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rafie S, Moitra S, Brashier BB. Association between the Serum Metabolic Profile and Lung Function in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Turk Thorac J 2018;19:13-8. 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2017.17043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franssen FM, O'Donnell DE, Goossens GH, et al. Obesity and the lung: 5. Obesity and COPD. Thorax 2008;63:1110-7. 10.1136/thx.2007.086827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Y, Yang C, Lei Z, et al. Cigarette smoking exposure breaks the homeostasis of cholesterol and bile acid metabolism and induces gut microbiota dysbiosis in mice with different diets. Toxicology 2021;450:152678. 10.1016/j.tox.2021.152678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pezzuto A, Ricci A, D'Ascanio M, et al. Short-Term Benefits of Smoking Cessation Improve Respiratory Function and Metabolism in Smokers. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2023;18:2861-5. 10.2147/COPD.S423148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kočar E, Katz S, Pušnik Ž, et al. COVID-19 and cholesterol biosynthesis: Towards innovative decision support systems. iScience 2023;26:107799. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raggi P, Becciu ML, Navarese EP. Remnant cholesterol as a new lipid-lowering target to reduce cardiovascular events. Curr Opin Lipidol 2024;35:110-6. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campanella A, Iacovazzi PA, Misciagna G, et al. The Effect of Three Mediterranean Diets on Remnant Cholesterol and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Secondary Analysis. Nutrients 2020;12:1674. 10.3390/nu12061674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Correction to : 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2024;45:518. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]