Abstract

Background

Mechanical ventilation is crucial for patients with cardiogenic shock (CS), while diagnosing ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in CS patients is difficult. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an effective diagnostic model for VAP in CS. This study aims to develop an effective risk prediction model for VAP in CS patients based on clinical data.

Methods

The study is a retrospective study conducted using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) dataset. Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses identified the variables for establishing a predictive model. Its clinical utility was assessed via decision curve analysis (DCA), as well as its discrimination and calibration through the concordance index (C-index) and calibration plots.

Results

Among the 807 CS patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), 112 developed VAP. The results of this study suggest that the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, the length of ICU stay (ICU LOS), concomitant hepatic insufficiency, and the presence of concomitant sepsis are independent risk factors associated with the development of VAP during hospitalization. The area under the curve for the model was 0.798. In addition, the clinical data of 90 CS patients in the South District of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University were retrospectively analyzed for external verification, and the area under the external validation curve was 0.783. The Hosmer-Lemeshow P=0.47 indicates that the fit is acceptable, and the calibration curve proves that the predictive model has proper discrimination and good calibration. DCA revealed that the VAP prediction nomogram proved clinically valuable when interventions were considered at a VAP probability threshold ranging from 1% to 50%.

Conclusions

We can apply the nomogram for predicting the development of VAP after admission to the ICU for patients with CS, utilizing readily accessible variables.

Keywords: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), cardiogenic shock (CS), predictive model, nomogram

Highlight box.

Key findings

• The ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) predictive model (including the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, the length of intensive care unit stay, concomitant hepatic insufficiency, and the presence of concomitant sepsis) can be used in clinical practice to assess the risk of VAP in cardiogenic shock (CS) patients.

What is known and what is new?

• There are certain limitations with the current clinical, radiological, and microbiological methods for early diagnosis of VAP.

• The predictive performance of the VAP predictive model for the risk of developing VAP in CS patients has been externally verified.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Clinicians can use the VAP prediction model to identify CS patients who may develop VAP early, which may be meaningful for the treatment and prognosis of critically ill patients. Future prospective studies are needed to further explore and discover a more effective prediction model based on clinical variables to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of VAP patients.

Introduction

Background

The pathogenesis of cardiogenic shock (CS) is complicated and diverse, poses a major challenge in medical practice and has an extremely high mortality rate, which can lead not only to multi-organ failure but also to death (1,2). Acute respiratory failure occurs in 50% to 88% of CS patients and requires respiratory support in more than 80% of patients (3). Critically ill patients may require invasive mechanical ventilation to provide adequate alveolar ventilation and improve arterial oxygenation to relieve hypoxia due to respiratory distress (4). However, this intervention significantly elevates the risk for these patients to develop ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

VAP affects approximately 23.5% to 39.3% of intubated patients and is one of the most serious respiratory infections (5). VAP ranks first among hospital-acquired infections in the statistical intensive care unit (ICU), impacting approximately 20% to 36% of mechanically ventilated patients (6). VAP is a significant contributor to mortality, especially in cases of sepsis and multiple organ failure (5). Additionally, patients suffering from VAP often experience prolonged mechanical ventilation, extended stays in the ICU, and may possess a poorer overall prognosis (7).

Rationale and knowledge gap

Nonetheless, the existing methods for clinical, radiological, and microbiological diagnosis of VAP continue to exhibit certain limitations (7,8). Biomarkers and artificial intelligence present a promising avenue for future research innovation (9,10). Nonetheless, there is a limited availability of predictive models that utilize existing data to forecast the occurrence of VAP in patients with CS.

Objective

Consequently, our study aims to create and validate a clinical model that can predict the occurrence of VAP by analyzing the clinical features of patients in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) dataset, and subsequently assess its accuracy. The nomogram designed for predicting VAP is regarded as a valuable prognostic instrument to help physicians assess a patient’s risk of developing VAP and enable improved clinical decision-making. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2038/rc).

Methods

Source of data

The MIMIC-IV dataset utilized for training and testing the model encompasses data related to numerous ICU inpatients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) spanning the years 2008 to 2019 (11). The database is a public data resource and has passed the Health Insurance Continuity and Accountability Act.

Study subjects

We included 807 CS patients in this study, who were invasively ventilated for a duration exceeding 48 hours and were older than 18 years. Baseline parameters were collected, including the age and gender of ICU patients at the time of their first ICU admission, as well as laboratory parameters recorded within the first 24 hours following ICU admission. The diagnostic standards of VAP are compliant and were developed in 2016 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society (12). Patients with CS were categorized into two teams grounded on the occurrence of VAP during hospitalization: the VAP group, which comprised 112 cases, and the non-VAP group, consisting of 695 cases. Additionally, we collected and analyzed the clinical data from 90 patients admitted to the South District of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from October 2013 to September 2024 who were diagnosed with CS. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The ethics committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University approved this study (No. 2024-220-01) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Model development

Handling missing data

The raw data used for model development in the current study all come from the MIMIC-IV database. We use multiple imputation methods to handle missing data (13). This process resulted in the generation of five complete datasets for the development of the model. The multivariate imputation by chained equations algorithm (14) is capable of imputing a combination of continuous, binary, as well as unordered and ordered categorical data. The imputation models incorporated these variables in conjunction with all chosen candidate predictor variables.

Predictors selection

Initially, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the existing models for predicting VAP, alongside a systematic literature review focused on their application in VAP diagnosis. Our objective was to identify potential predictor variables. Subsequently, a screening scrutiny of patient’s clinical data and laboratory results in the MIMIC-IV database was carried out. From the MIMIC-IV dataset, we identified a total of 31 potential variables for inclusion in the modeling process. Variables exhibiting over 30% missing values were excluded from consideration, resulting in the final inclusion of 29 variables in our analysis. Patient demographics, which encompassed age, gender, admission source, diagnosis, as well as clinical and laboratory results obtained within 24 hours of ICU admission, were analyzed. The variables linked with the occurrence of VAP were determined build on the outcomes of univariate binary logistic regression analysis. The impacts of predictors on the outcomes in the MIMIC-IV dataset were assessed build on the results of the multivariate secondary logistic regression.

Assessing the model’s performance

In order to assess the discrimination capability of the predictive model built in this study, it was calculated by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Also to evaluate the calibration of this predictive model, the calibration curve is used in conjunction with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Additionally, to assess the discriminant effectiveness of the predictive model, we calculated the Harrell concordance index (C-index). In order to evaluate the clinical utility of the VAP predictive model in this study, we decided to use decision curve analysis (DCA) (15) to quantify the net benefit of different threshold probabilities.

Statistical analysis

The median (interquartile range) was used to represent continuous variables. To estimate the differences between these variables, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. The count (percentage) was used to represent categorical variables. Depending on the specifics of the data, choose whether you want to use the exact Fisher test or the Chi-squared test to estimate the differences between these variables. The characteristics were analyzed using P values, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and corresponding odds ratios (ORs). Differences were deemed statistically significant if a P value was <0.05.

R software was used for all statistical analyses (version 4.2.2, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Among the patients with CS enrolled in this study, 112 individuals developed VAP. The demographic and baseline features suggest that lactate (Lac) levels (P=0.049), the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (P<0.001), Acute Physiology Score (APS) III (P=0.01), length of ICU stay (ICU LOS) (P<0.001), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (P=0.043), use of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) (P<0.001), administration of vasoconstrictor agents (P=0.01), presence of concomitant hepatic insufficiency (P=0.003), and incidence of comorbid sepsis (P<0.001), were comparable in patients with VAP and those without VAP (Table 1). The duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (51 vs. 151.18, P<0.001) and the ICU LOS (6.34 vs. 14.75, P<0.001) were significantly longer in patients of the VAP group than patients in the non-VAP group. A greater proportion of users of NMBAs was observed in the VAP group comparable to the non-VAP group (39% vs. 19%, P<0.001). Additionally, the incidence of VAP in conjunction with hepatic insufficiency (29% vs. 16%, P=0.003) and sepsis (97% vs. 83%, P<0.001) was found to be higher.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of CS patients with or without VAP.

| Patient characteristics | Total (n=807) | No VAP group (n=695) | VAP group (n=112) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.08 [60.74, 79.52] | 71.59 [61.12, 79.59] | 70.19 [59.73, 78.24] | 0.20 |

| Gender | 0.45 | |||

| Female | 318 [39] | 278 [40] | 40 [36] | |

| Male | 489 [61] | 417 [60] | 72 [64] | |

| GCS | 15 [14, 15] | 15 [14, 15] | 15 [14, 15] | 0.78 |

| Admission source | 0.70 | |||

| CVICU | 174 [22] | 156 [22] | 18 [16] | |

| CCU | 376 [47] | 318 [46] | 58 [52] | |

| MICU | 123 [15] | 105 [15] | 18 [16] | |

| MICU/SICU | 59 [7] | 52 [7] | 7 [6] | |

| Neuro SICU | 6 [1] | 5 [1] | 1 [1] | |

| SICU | 41 [5] | 34 [5] | 7 [6] | |

| TSICU | 28 [3] | 25 [4] | 3 [3] | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (hours) | 59.92 [31, 120.13] | 51 [28, 105] | 151.18 [90.36, 246.94] | <0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 6.94 [4.58, 11.72] | 6.34 [4.2, 9.97] | 14.75 [8.65, 22.84] | <0.001 |

| Reintubation | 0.71 | |||

| No | 711 [88] | 614 [88] | 97 [87] | |

| Yes | 96 [12] | 81 [12] | 15 [13] | |

| WBC (k/μL) | 15.9 [12.1, 20.75] | 15.9 [11.9, 20.8] | 16.1 [12.95, 20.12] | 0.60 |

| pH | 7.3 [7.2, 7.38] | 7.31 [7.2, 7.38] | 7.27 [7.2, 7.36] | 0.12 |

| Lac (mmol/L) | 2.9 [1.7, 5.35] | 2.8 [1.7, 5.3] | 3.65 [2.1, 5.72] | 0.049 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.7 [1.1, 2.5] | 1.7 [1.1, 2.4] | 1.65 [1.1, 2.7] | 0.78 |

| FiO2 (%) | 50 [40, 60] | 50 [40, 60] | 50 [40, 50] | 0.14 |

| T (℃) | 37.3 [36.9, 37.92] | 37.28 [36.9, 37.9] | 37.36 [36.89, 38] | 0.55 |

| SpO2 (%) | 91 [88, 94] | 91 [88, 94] | 91 [85, 94] | 0.11 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 170 [100, 253.25] | 174 [100, 256.75] | 166.33 [96.25, 250] | 0.73 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 55 [48, 61] | 55 [48, 61] | 55 [47, 61] | 0.93 |

| APS III | 57 [44, 73] | 57 [44, 71] | 62 [47.75, 80.25] | 0.01 |

| SOFA | 8 [6, 11] | 8 [5, 11] | 9 [7, 11] | 0.043 |

| Glucocorticoids | 0.10 | |||

| No | 628 [78] | 548 [79] | 80 [71] | |

| Yes | 179 [22] | 147 [21] | 32 [29] | |

| Vasoconstrictor agents | 0.01 | |||

| No | 119 [15] | 112 [16] | 7 [6] | |

| Yes | 688 [85] | 583 [84] | 105 [94] | |

| NMBAs | <0.001 | |||

| No | 634 [79] | 566 [81] | 68 [61] | |

| Yes | 173 [21] | 129 [19] | 44 [39] | |

| Lung cancer | 0.68 | |||

| No | 795 [99] | 685 [99] | 110 [98] | |

| Yes | 12 [1] | 10 [1] | 2 [2] | |

| Hypertension | 0.69 | |||

| No | 564 [70] | 488 [70] | 76 [68] | |

| Yes | 243 [30] | 207 [30] | 36 [32] | |

| Chronic lung diseases | 0.30 | |||

| No | 546 [68] | 465 [67] | 81 [72] | |

| Yes | 261 [32] | 230 [33] | 31 [28] | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.15 | |||

| No | 524 [65] | 444 [64] | 80 [71] | |

| Yes | 283 [35] | 251 [36] | 32 [29] | |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.90 | |||

| No | 390 [48] | 337 [48] | 53 [47] | |

| Yes | 417 [52] | 358 [52] | 59 [53] | |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 0.003 | |||

| No | 661 [82] | 581 [84] | 80 [71] | |

| Yes | 146 [18] | 114 [16] | 32 [29] | |

| Sepsis | <0.001 | |||

| No | 124 [15] | 121 [17] | 3 [3] | |

| Yes | 683 [85] | 574 [83] | 109 [97] |

Data are presented as n [%] or median [interquartile range]. Use of NMBAs was defined as the use of any NMBA such as vecuronium, rocuronium. APS, Acute Physiology Score; CCU, coronary care unit; CS, cardiogenic shock; CVICU, cardiac vascular intensive care unit; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU LOS, length of intensive care unit stay; Lac, lactate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MICU, medical intensive care unit; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agent; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; SICU, surgical intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; T, temperature; TSICU, trauma surgical intensive care unit; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; WBC, white blood cell.

Model development

Table 2 summarizes the results of the univariate analysis that factors related to the development of VAP in patients with CS by demographic and clinical variables. The analysis revealed that several variables were considerably linked with the development of VAP. Notably, the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation was linked to VAP development with an OR of 1.007 (95% CI: 1.005–1.009; P<0.001). Similarly, the ICU LOS also demonstrated a significant correlation, yielding an OR of 1.091 (95% CI: 1.069–1.117; P<0.001). Furthermore, APS III indicated an OR of 1.012 (95% CI: 1.003–1.021; P=0.006), while SOFA score reported an OR of 1.069 (95% CI: 1.012–1.131; P=0.02). The administration of NMBAs was associated with a heightened risk, evidenced by an OR of 2.839 (95% CI: 1.849–4.331; P<0.001). The use of vasoconstrictor agents also contributed significantly, reflected in an OR of 2.882 (95% CI: 1.399–6.975; P=0.009). Furthermore, in the company of concomitant hepatic insufficiency was linked to an OR of 2.039 (95% CI: 1.278–3.194; P=0.002), while comorbid sepsis presented a particularly strong association with an OR of 7.659 (95% CI: 2.825–31.467; P<0.001). All of the above factors were taken into account and analyzed when building a multivariate binary logistic regression model. Ultimately, the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (OR =1.003; 95% CI: 1.001–1.006; P=0.02), ICU LOS (OR =1.050; 95% CI: 1.016–1.086; P=0.004), concurrent hepatic insufficiency (OR =1.817; 95% CI: 1.088–2.983; P=0.02), and the presence of comorbid sepsis (OR =3.848; 95% CI: 1.349–16.233; P=0.03) was recognized as independent risk elements for the development of VAP (Table 2).

Table 2. Logistic regression model for predicting VAP in CS.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 1.007 | 1.005–1.009 | <0.001 | 1.003 | 1.001–1.006 | 0.02 | |

| ICU LOS | 1.091 | 1.069–1.117 | <0.001 | 1.050 | 1.016–1.086 | 0.004 | |

| Lac | 1.047 | 0.985–1.109 | 0.13 | ||||

| APS III | 1.012 | 1.003–1.021 | 0.006 | 1.006 | 0.994–1.018 | 0.36 | |

| SOFA | 1.069 | 1.012–1.131 | 0.02 | 0.984 | 0.909–1.066 | 0.69 | |

| Hypertensives | |||||||

| No | |||||||

| Yes | 2.882 | 1.399–6.975 | 0.009 | 1.217 | 0.536–3.139 | 0.66 | |

| NMBAs | |||||||

| No | |||||||

| Yes | 2.839 | 1.849–4.331 | <0.001 | 1.248 | 0.731–2.089 | 0.41 | |

| Hepatic insufficiency | |||||||

| No | |||||||

| Yes | 2.039 | 1.278–3.194 | 0.002 | 1.817 | 1.088–2.983 | 0.02 | |

| Sepsis | |||||||

| No | |||||||

| Yes | 7.659 | 2.825–31.467 | <0.001 | 3.848 | 1.349–16.233 | 0.03 | |

APS, Acute Physiology Score; CI, confidence interval; CS, cardiogenic shock; ICU LOS, length of intensive care unit stay; Lac, lactate; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agent; OR, odds ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

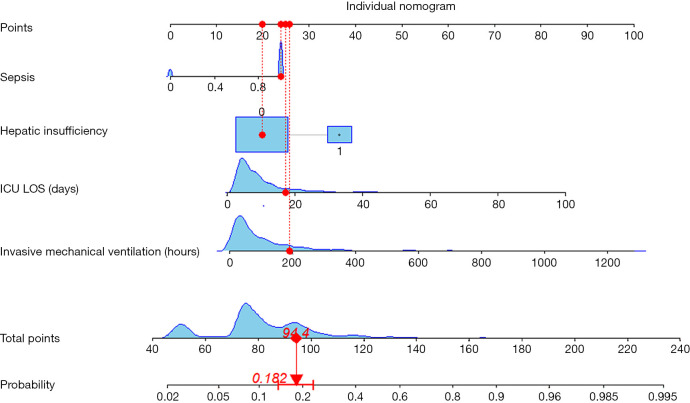

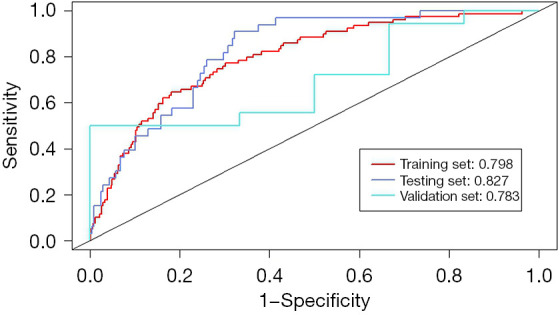

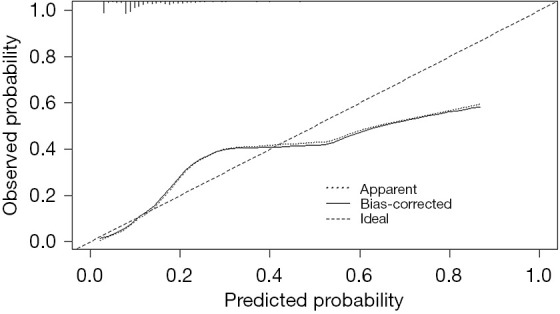

Model visualization and performance

This predictive model was successfully constructed, which combines the independent predictors mentioned above, and illustrated as a nomogram (Figure 1). We used the Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fitting to prevent overfitting of the current model. As illustrated in Figure 2, the AUROC is calculated as 0.798, 0.827, and 0.783, respectively, for the training, testing, and validation sets. In addition, the calibration curve of the VAP predictive model for CS patients exhibited good concordance within this study (Figure 3). The calculation of C-index of the model in this study showed that the prediction nomogram has sufficient discrimination with a specific result of 0.798 (95% CI: 0.747–0.849). Furthermore, the apparent performance of the VAP risk nomogram reflected its strong prediction capability.

Figure 1.

Developed VAP predictive model in patients with CS. Summing the scores of variables included in the model. And then a vertical line at the total score was drawn and making it intersect with the line representing the predicted VAP. The corresponding value of the point of intersection was the predicted VAP of individuals. Hepatic insufficiency: 0, no; 1, yes. CS, cardiogenic shock; ICU LOS, length of intensive care unit stay; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Figure 2.

The ROC curves of predictive model for VAP in patients with CS. CS, cardiogenic shock; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Figure 3.

Calibration curve of VAP predictive model in CS patients. A closer fit to the diagonal dotted line represents a better prediction. CS, cardiogenic shock; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

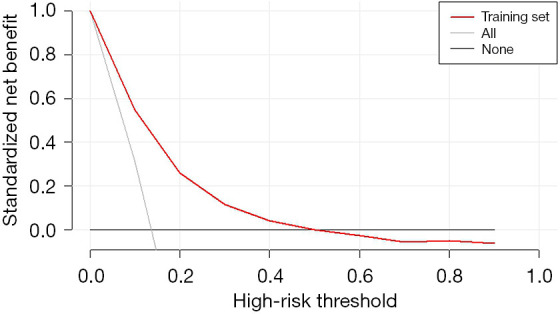

Clinical application

Figure 4 presents a DCA of the VAP predictive model for CS patients. The results indicate that when the patient threshold probability is between 1% and 50%, utilizing the VAP predictive nomogram will provide greater benefits for patients than in extreme cases, where all patients are diagnosed with VAP or not diagnosed with VAP.

Figure 4.

DCA curve of the VAP predictive model in CS patients. The decision curve shows that if the threshold probability of a patient is >1 and <50%, using this VAP nomogram prediction in the current study to predict VAP risk adds more benefit than the “intervention-for-all” patient scheme or the “intervention-for-none” scheme. CS, cardiogenic shock; DCA, decision curve analysis; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

These results suggest that the predictive model constructed in this study offers a greater net benefit for predicting the onset of VAP over a relatively wide threshold probability range, indicating a significant clinical benefit.

Discussion

Key findings

Our retrospective findings indicate that the freshly exploited VAP predictive model may serve as a worthwhile implement for projecting the development of VAP in CS patients. The findings of univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses indicated that hepatic insufficiency, ICU LOS, sepsis and the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation were the important individual elements that determined the risk of VAP among patients with CS.

In this study, the highest proportion of patients in the VAP group had concomitant sepsis, followed by those with renal insufficiency. According to the 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) guidelines, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) should be initiated immediately when life-threatening disturbances in fluid, electrolyte, or acid-base balance occur, or when complications from AKI arise. However, determining the optimal timing for initiating CRRT remains a key focus of recent KDIGO research. Several randomized trials in adults have assessed the impact of CRRT initiation timing on outcomes, with conflicting results (16). A cohort study involving children and adolescents found that delayed initiation of CRRT was associated with more severe major adverse kidney events at 90 days and increased resource utilization (17). Another retrospective study based on the MIMIC-IV database indicated that, while there was no significant association between CRRT initiation timing and mortality, early initiation of CRRT may improve clinical outcomes in patients with lower non-renal SOFA scores (18). These findings suggest the need for further prospective, multicenter studies to define the optimal timing for initiating CRRT. When deciding whether to initiate CRRT, a comprehensive evaluation of the risk of complications, overall prognosis, recovery potential, and patient preferences should be considered. Additionally, dynamic adjustments based on the patient’s clinical status should guide the provision of CRRT support in a reasonable and feasible manner.

Comparison with similar researches and explanations of findings

The length of invasive mechanical ventilation and ICU LOS have been shown to correlate with the occurrence of VAP, corroborating findings reported in earlier studies (5). A retrospective analysis involving 6,126 adult patients in the ICU revealed a notable correlation between the length of invasive mechanical ventilation and the subsequent onset of VAP (19). Our findings indicate that patients with CS who developed VAP experienced prolonged stays in the ICU as well as an increased length of invasive mechanical ventilation, aligning with the results of earlier studies (20,21).

This may be attributed to the extended duration of hospital stays, which is associated with increased exposure in the inpatient environment. Furthermore, mechanical ventilation is an invasive intervention that heightens the risk of developing VAP by facilitating the introduction of external pathogens into the patient’s respiratory system (22). The findings indicate that, to improve patient prognosis and ensure safety, identifying the risk factors linked to VAP and implementing timely preventive strategies is critical.

A summary analysis of the outcomes of this study exhibit that the development of VAP does not correlate with age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, reintubation, white blood cell (WBC) count, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, body temperature, or the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio. However, it is significant that some researches have identified these factors as potential risk factors for the development of VAP (5). The observed discrepancy in this study may stem from differences in hospital-acquired infection control and CS management systems across different countries over the past two decades. Additionally, shifts in diagnostic criteria and definitions of VAP may have further contributed to these differences. Consequently, there is a significant need for more recent research findings to identify and generalize the risk factors linked with the development of VAP in greater depth.

Immunodeficiency acquired in ICU may arise among ICU patients as a consequence of coexisting sepsis. The most prevalent infections acquired in ICU among immunocompromised patients are ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections, which encompass both VAP and ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis (VAT), as well as bloodstream infections (23,24). The infections most frequently observed in immunocompromised patients in ICU are VAP and VAT. However, several studies indicate that the incidence of these infections may be lower in this population compared to non-immunocompromised patients (25). In a prospective study, it was observed that patients with immunosuppression experienced a lower incidence of VAT at 7% compared with 12% in patients without immunosuppression, as well as an occurrence of VAP at 9% vs. 13% in the non-immunosuppressed group (26). Consequently, the relationship between coexisting sepsis in patients and the risk of developing VAP remains a subject of debate, necessitating further investigation.

The liver is crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis, and individuals with hepatic insufficiency may experience both congenital and acquired immune dysregulation (27). As a result, these patients may face a heightened risk of developing complications related to VAP and could be at an increased risk of mortality. Recent studies indicated that hepatic insufficiency is a predictor of more severe inflammation and that patients suffering from hepatic insufficiency tend to have a poorer prognosis (28,29). Patients with immune dysfunction due to hepatic insufficiency are at higher risk of secondary infection, which can be life-threatening, leading to higher organ dysfunction and mortality (30,31). Bacterial infections (BIs) are frequently observed in patients suffering from hepatic insufficiency, and are four to five times higher than those hospitalized for other reasons (32). A multicenter, prospective, intercontinental research revealed a significant incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) BIs among patients suffering from cirrhosis (33). In summary, this indicates that hepatic insufficiency serves as a significant factor affecting the incidence of VAP.

Strengths, limitations, implications, and actions needed

The strength of this study is that previous scoring systems, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS), tended to be intricate and often required considerable time for assessment. In contrast, the VAP predictive nomogram offers a straightforward and user-friendly alternative, allowing for rapid utilization. The VAP predictive nomogram serves as a valuable tool for clinicians to identify critically ill patients at risk of developing VAP during their stay in the ICU. By enabling tailored prevention and intervention strategies, this predictive model not only aids in improving patient recovery outcomes but also helps mitigate the burden of limited ICU bed availability. However, it is critical to recognize certain disadvantages associated with our study. This retrospective study is subject to certain inherent limitations. The MIMIC-IV database is a publicly accessible, extensive single-center database that global researchers can utilize without charge (11). Significant application has been found in several directions, including the improvement of predictive models, epidemiological research, and educational courses. Due to the absence of comprehensive data for several laboratory indicators, important clinical markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin levels were excluded from the analysis. These indicators are crucial for assessing nosocomial infections (34). These factors might have influenced the stability of the nomogram used for predicting VAP in comparison to the present forecasts. In this research, the external validation was conducted using a sample comprised solely of patients from a single tertiary general hospital in Hefei. The limitation of external validation data calls into question the reliability and accuracy of this predictive model. Therefore, it is essential that future prospective studies further evaluate these findings to confirm the model’s efficacy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, utilizing the ROC curve, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, calibration curve, DCA, and C-index, we successfully developed a pragmatic predictive model for predicting VAP with relatively strong performance and acceptable fit of the model. Clinicians can utilize the VAP predictive model in clinical practice to assess the risk of developing VAP in patients with CS. This tool enables them to implement preventive strategies in an early stage. Active and efficacious preventive treatments may provide critical patients with an improved prospect.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The ethics committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University approved this study (No. 2024-220-01) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2038/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2038/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2038/dss

References

- 1.Chioncel O, Parissis J, Mebazaa A, et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and contemporary management of cardiogenic shock - a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1315-41. 10.1002/ejhf.1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masip J, Frank Peacok W, Arrigo M, et al. Acute Heart Failure in the 2021 ESC Heart Failure Guidelines: a scientific statement from the Association for Acute CardioVascular Care (ACVC) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2022;11:173-85. 10.1093/ehjacc/zuab122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laghlam D, Benghanem S, Ortuno S, et al. Management of cardiogenic shock: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care 2024;14:45. 10.1186/s13613-024-01260-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Povlsen AL, Helgestad OKL, Josiassen J, et al. Invasive mechanical ventilation in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: A contemporary Danish cohort analysis. Int J Cardiol 2024;405:131910. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frondelius T, Atkova I, Miettunen J, et al. Early prediction of ventilator-associated pneumonia with machine learning models: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance(✰). Eur J Intern Med 2024;121:76-87. 10.1016/j.ejim.2023.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howroyd F, Chacko C, MacDuff A, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: pathobiological heterogeneity and diagnostic challenges. Nat Commun 2024;15:6447. 10.1038/s41467-024-50805-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt CE. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:888-906. 10.1007/s00134-020-05980-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adult patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:1170-9. 10.1007/s00134-020-06036-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole S, Clark TW. Rapid syndromic molecular testing in pneumonia: The current landscape and future potential. J Infect 2020;80:1-7. 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang Y, Zhu C, Tian C, et al. Early prediction of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critical care patients: a machine learning model. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:250. 10.1186/s12890-022-02031-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data 2023;10:1. 10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Executive Summary: Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:575-82. 10.1093/cid/ciw504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z. Multiple imputation with multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) package. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:30. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377-99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vickers AJ, Van Calster B, Steyerberg EW. Net benefit approaches to the evaluation of prediction models, molecular markers, and diagnostic tests. BMJ 2016;352:i6. 10.1136/bmj.i6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan HC, Chen YY, Tsai IJ, et al. Accelerated versus standard initiation of renal replacement therapy for critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT studies. Crit Care 2021;25:5. 10.1186/s13054-020-03434-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gist KM, Menon S, Anton-Martin P, et al. Time to Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy Initiation and 90-Day Major Adverse Kidney Events in Children and Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e2349871. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuermaimaiti M, Wang M, Lou R, et al. The impact of initiation timing of continuous renal replacement therapy on outcomes in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury a retrospective study from the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 2025;15:10922. 10.1038/s41598-024-84435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giang C, Calvert J, Rahmani K, et al. Predicting ventilator-associated pneumonia with machine learning. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e26246. 10.1097/MD.0000000000026246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranzani OT, Niederman MS, Torres A. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2022;48:1222-6. 10.1007/s00134-022-06773-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaragoza R, Vidal-Cortés P, Aguilar G, et al. Update of the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia in the ICU. Crit Care 2020;24:383. 10.1186/s13054-020-03091-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Oliveira Manoel AL. Surgery for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care 2020;24:45. 10.1186/s13054-020-2749-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nates JL, Pène F, Darmon M, et al. Septic shock in the immunocompromised cancer patient: a narrative review. Crit Care 2024;28:285. 10.1186/s13054-024-05073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreitmann L, Helms J, Martin-Loeches I, et al. ICU-acquired infections in immunocompromised patients. Intensive Care Med 2024;50:332-49. 10.1007/s00134-023-07295-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreitmann L, Gaudet A, Nseir S. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Immunosuppressed Patients. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023;12:413. 10.3390/antibiotics12020413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreau AS, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, et al. Impact of immunosuppression on incidence, aetiology and outcome of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1701656. 10.1183/13993003.01656-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saviano A, Wrensch F, Ghany MG, et al. Liver Disease and Coronavirus Disease 2019: From Pathogenesis to Clinical Care. Hepatology 2021;74:1088-100. 10.1002/hep.31684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liakina V, Stundiene I, Milaknyte G, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on the liver: The experience of a single center. World J Gastroenterol 2022;28:5735-49. 10.3748/wjg.v28.i39.5735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, et al. Outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: An international registry study. J Hepatol 2021;74:567-77. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasa E, Hartmann P, Schnabl B. Liver cirrhosis and immune dysfunction. Int Immunol 2022;34:455-66. 10.1093/intimm/dxac030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casulleras M, Zhang IW, López-Vicario C, et al. Leukocytes, Systemic Inflammation and Immunopathology in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Cells 2020;9:2632. 10.3390/cells9122632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miranda-Zazueta G, León-Garduño LAP, Aguirre-Valadez J, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Current treatment. Ann Hepatol 2020;19:238-44. 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piano S, Singh V, Caraceni P, et al. Epidemiology and Effects of Bacterial Infections in Patients With Cirrhosis Worldwide. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1368-1380.e10. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galli F, Bindo F, Motos A, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein to rule out early bacterial coinfection in COVID-19 critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2023;49:934-45. 10.1007/s00134-023-07161-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]