Abstract

Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are significant risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), with their Collaborative interaction amplifying carcinogenic risks. To elucidate the role and underlying mechanisms of tobacco-alcohol co-exposure in ESCC pathogenesis, we treated the immortalized human normal esophageal epithelial cell line NE-1 and C57BL/6 mice with 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide (4NQO, a tobacco carcinogen analog) combined with ethanol. Results demonstrated that 4NQO-ethanol co-exposure accelerated esophageal squamous carcinogenesis. Through network toxicology and in vitro/in vivo experiments, we further validated that 4NQO-ethanol Combine exacerbated inflammatory responses and aggravated DNA damage. Mechanistically, 4NQO-ethanol co-exposure activated the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway. Furthermore, the addition of the TNF-α inhibitor reduced the proliferative and invasive capacities of cells co-stimulated by 4NQO and ethanol. These findings indicate that tobacco-ethanol co-exposure promotes the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inducing inflammation and DNA damage through TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Tobacco smoking, 4-Nitroquinoline-1-oxide, Ethanol, TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Network toxicology revealed the mechanism by which 4NQO synergizes with ethanol in esophageal squamous cell carcinogenesis.

-

•

4NQO synergizes with ethanol to promote inflammation and cause DNA damage.

-

•

4NQO synergizes with ethanol to activate the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common malignant tumor in the world today, divided into adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [1]. Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are independent risk factors for ESCC [2], and they may synergistically increase the risk of ESCC occurrence [3]. However, the exact role and underlying mechanisms of the Collaborative interaction between smoking and alcohol consumption in ESCC pathogenesis remain to be fully elucidated.

Nitrosamines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and volatile organic compounds in tobacco products have been demonstrated to be carcinogenic [4], capable of interacting with DNA to form carcinogenic DNA adducts [5]. Similarly, 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide (4NQO) reacts with genomic DNA to form stable quinolone monoadducts [[6], [7], [8]], and exhibits high similarity to tobacco-induced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in terms of both pathological morphology and gene expression alterations [9]. Therefore, we employed 4NQO as a chemical inducer to mimic tobacco carcinogenesis.

Alcohol consumption is closely associated with the initiation of various cancers. As alcohol intake increases, the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) onset also rises significantly [10]. Ethanol (EtOH) the primary component of alcoholic beverages, can exert carcinogenic effects through multiple pathways. Alcohol promotes the absorption of carcinogenic compounds from tobacco smoke into the body [11]. Additionally, alcohol promotes the secretion of inflammatory factors through multiple mechanisms, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [12,13]. The accumulation of these inflammatory cytokines activates the NF-κB pathway while concurrently inducing chronic inflammation and DNA damage. This process plays a critical role in tumorigenesis [14,15].

This study adopted for the first time a methodology integrating network toxicology with molecular docking, in vitro NE-1 cell experiments, and in vivo C57BL/6 mouse models. The results demonstrate that 4NQO combine with ethanol to promote the occurrence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway. We found that combined treatment with 4NQO and ethanol induced malignant transformation of NE-1 cells after 20 passages and aggravated esophageal epithelial carcinogenesis in mice. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated the initiation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes, enhancing the proliferative, invasive, and metastatic potentials of transformed cells. Through network toxicology analysis, we identified 64 overlapping genes associated with 4NQO, ethanol, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. These genes were significantly enriched in the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway and primarily linked to inflammatory responses and DNA damage. It is well-established that inflammation and DNA damage serve as critical drivers of carcinogenesis [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Our experiments revealed that 4NQO combined with ethanol significantly exacerbated inflammatory responses and amplified DNA damage compared to single-agent exposure. Further experimental validation confirmed that co-stimulation with 4NQO and ethanol upregulates the expression levels of key proteins in the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway. Furthermore, the addition of the TNF-α inhibitor reduced the proliferative and invasive capacities of cells co-stimulated by 4NQO and ethanol.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that tobacco-ethanol co-exposure promotes the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inducing inflammation and DNA damage through TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling. The findings of this study will provide important clues and evidence for understanding the pathogenesis of ESCC and developing new prevention and treatment measures.

2. Star★methods

2.1. Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-beta Actin Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB11001 |

| goat antirabbit IgG (H + L) | Ruipate | S1002 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. | Servicebio | GB25303 |

| Anti-Phospho- NF-kB p65 Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB113882 |

| Anti-Vimentin Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111308 |

| Anti-Phospho-H2A.X(S139) Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111841 |

| Anti-Ki67 Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111141 |

| Anti-TNF-alpha Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB115726 |

| NF-κB p65 Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | D14E12 |

| TRAF2 Rabbit pAb | ABclonal | A0962 |

| Anti-Vimentin Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111308 |

| Anti-N Cadherin Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111009 |

| Anti-Phospho-H2A.X (S139) Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | GB111841 |

| Immunol Staining Blocking Buffer | Beyotime | P0102 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Triton X-100 | Beyotime | P0097 |

| BCA | Solarbio | PC0020 |

| ECL | MCE | HY-K1005 |

| SweScript RT I First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | Servicebio | G3330 |

| 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (None ROX) | Servicebio | G3320 |

| DAPI | Biosharp | BL105A |

| EDU | Beyotime | C0075S |

| FBS | Gibco | B210710RP |

| DMEM high glucose | Viva Cell | C3113-0500 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Mouse Interleukin 6 (IL-6) ELISA Kit | Fusheng | A105582 |

| Mouse Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α) ELISA Kit | Fusheng | A115357 |

| Mouse Interleukin 1β(IL-1β) ELISA Kit | Fusheng | A105612 |

| BeyoClick™ EdU-555 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit | Beyotime | C0075S |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Real-time qPCR | This paper | Table 2 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/Cell | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | Vital River | C57BL/6J |

| NE-1 | Otwo Biotech | HTX3507 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Ethanol | CTD | https://ctdbase.org/ |

| 4-Nitroquinoline N-oxide | CTD | https://ctdbase.org/ |

| esophagus squamous cell carcinoma | NCBI, OMIM | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/?term= |

| GeneCards | https://www.genecards.org/ | |

| DisgeNet | https://disgenet.com/ | |

3. Experimental model and study participant details

3.1. Cell lines

The immortalized human normal esophageal epithelial cell line (NE-1) was purchased from Otwo Biotech (HTX3507; Shenzhen, China).

NE-1 cells were maintained in DMEM high-glucose medium (VivaCell, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 20 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA). All cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

3.2. Animal experiments and grouping

Sixty female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (License No.: SCXK [Beijing] 2021-0006). After 1-week acclimatization, mice were randomly allocated into four groups (n = 15/group): Control, EtOH, 4NQO, and 4NQO/EtOH. The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University (Ethics Approval No.: IACUC-HEBMU-2024063).

Throughout the 24-week study, propylene glycol served as the vehicle solution. 4-Nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO; Sigma-Aldrich, #N8141-5G) was dissolved in the vehicle and diluted to 100 μg/mL. This solution was provided ad libitum in light-protected containers. The 20 % (v/v) ethanol solution was administered based on the Meadows-Cook (MC) model – an established chronic alcohol intake protocol where sustained 20 % ethanol exposure achieves pharmacologically relevant blood ethanol concentrations in C57BL/6J mice [20], a critical consideration for experimental design.

4NQO Group: Free intake of 100 μg/mL 4NQO for 16 weeks, subsequently followed by ad libitum consumption of blank vehicle solution for 8 weeks.

Ethanol Group: Ad libitum consumption of blank vehicle solution for 16 weeks, then 20 % ethanol solution for 8 weeks [20].

4NQO/EtOH Group: Free intake of 100 μg/mL 4NQO for 16 weeks, subsequently switched to ad libitum consumption of 20 % ethanol for 8 weeks.

Control group: Received vehicle solution alone throughout the 24-week period.

At study termination, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and euthanized by cervical dislocation.

4. Method details

4.1. Cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Log-phase cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells/well and incubated with ethanol (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480, or 960 mmol/L) or 4NQO (0, 400, 800, 1200, 1600, 2000, or 2400 nmol/L) for 12 or 24 h. After treatment, 100 μL of 10 % CCK-8 reagent (RK1028, ReportBio, China) was added to each well, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37 °C. Use the microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA) to measure absorbance at 450 nm.

4.2. Cell proliferation assay

The experiment comprised four groups:NE-1 group: Cells were untreated (negative control). EtOH group: Cells were exposed to 200 mM ethanol for 12 h daily. 4NQO group: Cells were exposed to 400 nM 4NQO for 12 h daily. 4NQO/EtOH group: Cells were alternately exposed to 400 nM 4NQO and 200 mM ethanol for 12 h each daily. All treatments were maintained for 20 cell passages. Subsequently, 6 μM TNF-α inhibitor (SPD304, MCE, China) was added to the 4NQO/EtOH-treated cell group. Changes in proliferative and invasive capacities were observed 24 h later.

CCK-8 Assay: Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 2000 cells/well and incubated under 37 °C/5 % CO2. After treatment, 100 μL of 10 % CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

EDU Assay: Treated cells were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured for 24 huntil adherent. EdU working solution (C0075S, Beyotime, China) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, then stained with DAPI (10 μg/mL, BL105A, Biosharp, China) for 5 min at RT. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse C1, Nikon, Japan) and analyzed with ImageJ software.

4.3. Scratch wound healing assay

Treated cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well and cultured in a humidified incubator (37 °C/5 % CO2) until reaching 80–90 % confluence. A straight scratch was made in the monolayer using a sterile 1 mL pipette tip. The cells were gently washed with PBS three time to remove debris. Scratch closure was monitored and images were captured at 0, 24, and 48 h using an inverted microscope. Quantitative analysis of migration distance was performed with ImageJ software.

4.4. Transwell invasion assay

A 100 μL aliquot of 1:8 diluted Matrigel was added to the upper chambers of 24-well Transwell inserts and incubated for 3 h for polymerization. Treated cells were then seeded into the upper chambers, while the lower chambers were filled with medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). After incubation in a CO2 incubator for 24 h or 48 h, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde (15 min), stained with 0.1 % crystal violet (5 min), and photographed under a microscope. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

4.5. Body weight monitoring and histopathological evaluation in mice

During the 24-week experimental period, body weight and survival status of mice were recorded every 4 weeks starting from week 16. After the experiment, tissues were harvested under anesthesia and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 24 h. The tissues were then dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4-μm-thick slices for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Histopathological observations were performed by two pathologists blinded to each other's assessments using a light microscope.

4.6. Immunohistochemical staining (IHC)

Immunohistochemical (IHC) Staining for Protein Expression in Mouse Esophageal Tissues. Reagents and antibodies included: Anti-Ki67 Rabbit pAb (GB111141, Servicebio, China), Anti-TNF-alpha Rabbit pAb (GB115726, Servicebio, China), Phospho–NF–κB p105-S932 Rabbit mAb (AP1355, ABclonal),TRAF2 Rabbit pAb (A0962, ABclonal, China), Anti-Vimentin Rabbit pAb (GB111308, Servicebio, China), Anti-N Cadherin Rabbit pAb (GB111009, Servicebio, China), Anti-Phospho-H2A.X (S139) Rabbit pAb (GB111841, Servicebio, China).

4.7. Drug target screening

Potential target genes of ethanol and 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide were screened by entering the keywords “Ethanol” and “4-Nitroquinoline N-oxide” in the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, https://ctdbase.org/) [21], generating a list of potential targets for further analysis.

4.8. Disease target screening

Target genes of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) were retrieved by searching the keywords “esophagus squamous cell carcinoma” in the following databases: OMIM (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/) [22], GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) [23], and DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/). The retrieved genes were integrated and deduplicated, followed by gene name standardization using UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/).

4.9. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction

The ESCC-related targets, 4NQO targets, and ethanol-associated targets were integrated using Venny 2.1.0 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) to identify intersecting genes. These overlapping genes were subsequently imported into the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) [24] with the species parameter set to “Homo sapiens” for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction and analysis. The PPI data were then loaded into Cytoscape 3.9.1 for network visualization, where nodes were sorted in descending order of degree to highlight hub genes.

4.10. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were performed on intersecting genes using Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html) [25] with Homo sapiens as the species. The top 10 terms with the highest -LogP10 values were visualized as a bubble plot via the WEISHENGXIN platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/).

4.11. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations

The SDF-format ligand files of ethanol (Compound CID: 702) and 4NQO (Compound CID: 5955) were downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The PDB-format structures of target proteins were retrieved from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Molecular docking between ligands and protein receptors was performed using Discovery Studio 2017, with binding affinities quantified by LibDockScore [26]. Higher scores indicate stronger binding activity and greater stability between ligands and receptors.

ubsequent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the protein-ligand complexes were performed for 100 ns using GROMACS. The AMBER14SB-OL15 force field was applied to generate the protein topology files. Ligand topology files were constructed using the GAFF force field via the sobtop software. The system was solvated with TIP3P water molecules in a cubic box encompassing the entire docking complex, followed by the addition of Na+/Cl− ions to neutralize the system charge.Energy minimization was conducted in two phases: 2500 steps of steepest descent followed by 2500 steps of conjugate gradient algorithms. The system was equilibrated under NVT ensemble for 100 ps at a constant temperature (298.15 K), and subsequently under NPT ensemble for 100 ps at 1 bar pressure. Production MD simulations were carried out for 100 ns under periodic boundary conditions, with long-range electrostatic interactions calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method.

4.12. Detection of ROS in cell lines

ROS levels were measured in NE-1 and EtOH-treated cell groups. Briefly, both cell lines were plated in 6-well plates. After complete adhesion, cells were incubated with DCFH-DA solution (diluted 1:1000) at 37 °C for 20 min according to the manufacturer's instructions (S0034S, Beyotime, China), followed by three washes with PBS. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse C1, Nikon, Japan).

4.13. Elisa assay

Mouse serum samples were processed according to the instructions of the ELISA kit (Fusheng, Shanghai, China). Optical density (OD) values were measured at 450 nm, and concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were quantified by comparison to their respective standard curves.

4.14. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcriptase kit (G3330, Servicebio, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with a 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (ROX-free) kit (G3320, Servicebio, China) following the manufacturer's protocol on a CFX real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). Gene expression levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

4.15. DNA damage immunofluorescence staining

Briefly, cells were seeded on glass slides and allowed to adhere. After fixation with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 10 min, cells were permeabilized for 10 min using an immunofluorescence permeabilization buffer containing Triton X-100 (P0097, Beyotime, China). Blocking was performed for 1 h with immunostaining blocking buffer (P0102, Beyotime, China). Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with γ-H2AX primary antibody (1:250 dilution, GB111841, Servicebio, China), followed by incubation with a fluorescent secondary antibody (1:400 dilution, GB25303, Servicebio, China) for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (10 μg/mL, BL105A, Biosharp, China) for 5 min. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse C1, Nikon, Japan) and analyzed with ImageJ.

4.16. Western blotting analysis

Proteins were lysed and extracted from cell samples using RIPA lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were measured with a BCA protein assay kit (PC0020, Solarbio, China). Total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (3010040001, Sigma-Aldrich). After blocking with 5 % skimmed milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. Protein expression was detected using an ECL detection kit (HY–K1005, MCE, USA), and images were analyzed with Image J software. The following antibodies were used: NF-κB p65 Rabbit mAb (1:500, D14E12, Cell Signaling, US), Anti-Vimentin Rabbit pAb (1:750, GB111308, Servicebio, China), Anti-beta Actin Rabbit pAb (1:1500, GB11001, Servicebio, China) and goat antirabbit IgG (H + L) (1:5000, S1002, Ruipate, China).

4.17. Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 22.0 software, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data normality and homogeneity of variance were tested. Statistical analyses employed either the one-sample t-test or one-way ANOVA for multiple pairwise comparisons between sample means. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

5. Results

5.1. 4NQO combine with EtOH to induce malignant transformation of NE-1 cells

We selected varying concentrations of 4NQO and EtOH for CCK-8 assays in NE-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, both 4NQO and EtOH inhibited NE-1 cell proliferation in dose- and time-dependent manners. The IC50 values for 4NQO were 701.2 nmol/L at 12 h and 352.6 nmol/L at 24 h, while those for EtOH were 366.5 mmol/L at 12 h and 305.6 mmol/L at 24 h. To maintain NE-1 cell viability, we chose 400 nm. 4NQO and 200 mm EtOH for subsequent induction (Fig. 1B). Following 20 passages of induction with 4NQO and EtOH, we assessed cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities. Results demonstrated that compared to the 4NQO group and EtOH group, the 4NQO/ethanol combination group significantly enhanced NE-1 cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (Fig. 1C–G).

Fig. 1.

4NQO combine with EtOH to induce malignant transformation in NE-1 cells.

(A) CCK-8 assay showing the effects of varying concentrations of 4NQO and EtOH on NE-1 cells.

(B) Construction of the 4NQO and EtOH induced NE-1 cell model.

(C) Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assay.

(D) Proliferation capacity evaluated by EDU assay.

(E) Migration ability measured via scratch wound healing assay.

(F) Invasive capability analyzed using Transwell chambers.

(G) 4NQO combined with EtOH enhances N-cadherin and Vimentin protein expression in NE-1 cells.

Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

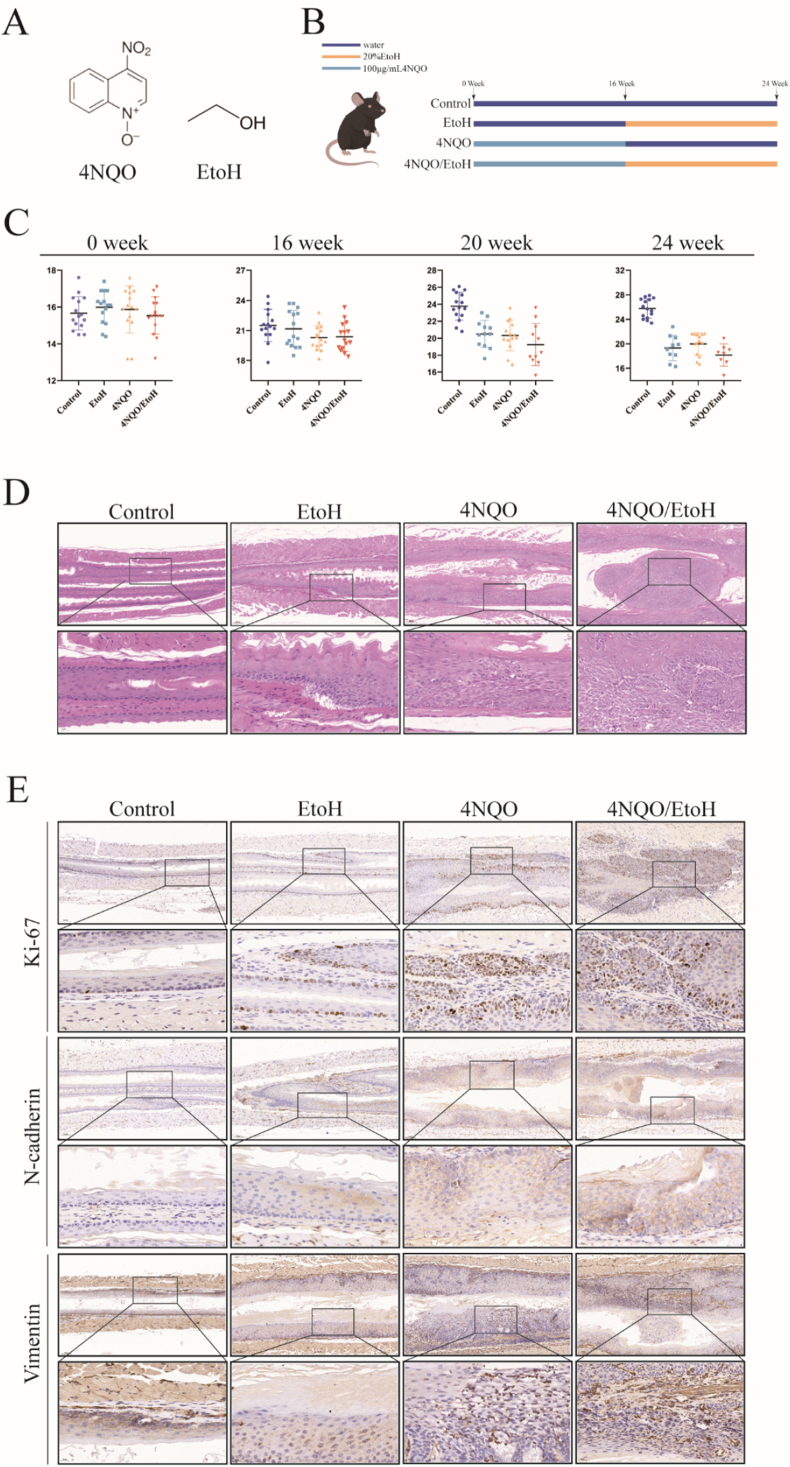

5.2. The combination of 4NQO and EtOH enhanced the proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities of mouse esophageal epithelial cells, and resulted in reduced body weight in mice

We established a 4NQO Collaborative EtOH induced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) mouse model (Fig. 2B). During the 24-week experimental period, we observed a continuous increase in the weight of the control mice, while the weight of the mice in the 4NQO/EtOH group significantly decreased compared to both the 4NQO group and the EtOH group (Fig. 2C). Histopathological examination of the mouse esophagus revealed no lesion-related changes in cell morphology or tissue structure in the control group. mild abnormal proliferation of local epithelial cells and a small number of inflammatory cells in the submucosal layer were seen in the esophageal tissue of the EtOH group. The epithelial mucosa of the esophageal tissue in the 4NQO group was thickened, exhibiting moderate to severe atypical proliferation accompanied by a high infiltration of inflammatory cells. In contrast, the esophageal epithelium of mice in the 4NQO/EtOH group displayed distinct features of squamous carcinoma, along with a significant infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 2D). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining results indicated that the positive staining for the proliferative protein Ki-67, as well as the invasion and metastasis markers N-cadherin and Vimentin, was significantly elevated in the esophageal epithelial tissues of the mice in the 4NQO/EtOH group compared to the 4NQO group and the EtOH group (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

4NQO combine with ethanol to induce esophageal carcinogenesis in mice.

(A) Molecular structures of 4NQO and EtOH.

(B) Establishment of the mouse esophageal squamous carcinoma model.

(C) Body weight changes in mice.

(D) Histopathological changes in esophageal tissues examined by H&E staining under microscopy.

(E) Expression levels of Ki-67, N-cadherin, and Vimentin in mouse esophageal tissues observed through IHC staining. Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

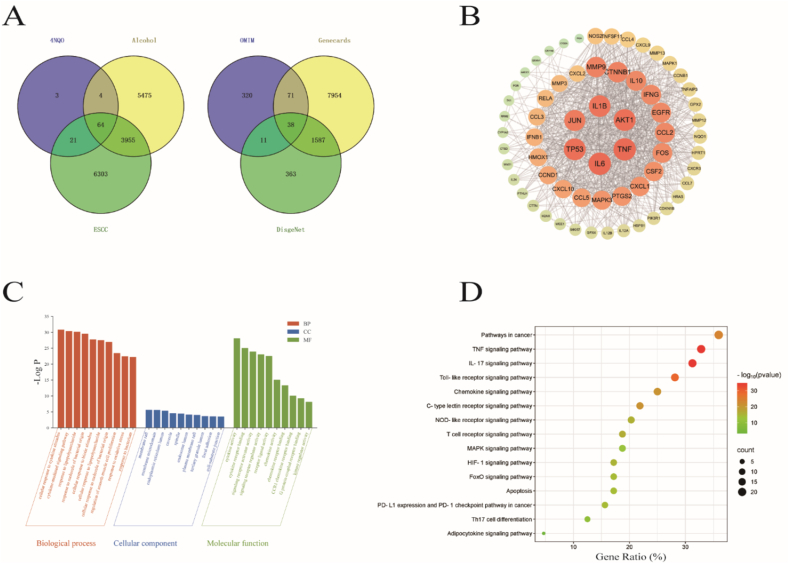

5.3. Network toxicology results

We screened a total of 10,343 ESCC-related targets (after removing duplicates) from NCBI.OMIM, GeneCards, and DisGeNET databases. From CTD, 92 4NQO-related targets and 9498 ethanol-related targets were identified. The intersection of targets related to “esophageal squamous cell carcinoma”, “4NQO”, and “ethanol” yielded 64 overlapping genes (Fig. 3A). A PPI network was constructed using the STRING database and analyzed in Cytoscape software (Fig. 3B). The analysis was based on node degree values to assess correlations: the larger the node, the darker the color, and the higher the degree value, indicating more biological functions in the network and a greater likelihood of serving as core target genes [27]. The results showed that TNF, IL6, TP53, JUN, IL1B, and AKT1 were the six targets most closely connected with other targets.

Fig. 3.

Screening and analysis of 4NQO, ethanol, and ESCC targets.

(A) Venn diagram of 4NQO, ethanol, and ESCC.

(B) Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network.

(C) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment plot.

(D) Top 10 enriched pathways of intersecting genes.

A total of 641 Gene Ontology (GO) terms were co-enriched, comprising 523 biological processes (BP), 38 cellular components (CC), and 80 molecular functions (MF). The top 10 significantly enriched terms (P < 0.01) in each category are presented (Fig. 3C and Table 1). BP primarily included cellular response to cytokine stimulus, cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, and response to lipopolysaccharide. CC involved membrane raft, membrane microdomain, and endoplasmic reticulum lumen. MF encompassed cytokine activity, cytokine receptor binding, and signaling receptor activator activity. Following removal of disease-irrelevant entries, KEGG analysis revealed the top 15 signaling pathways, such as Pathways in cancer, TNF signaling pathway, and IL-17 signaling pathway, with the TNF signaling pathway showing the strongest enrichment association (Fig. 3D).

Table 2.

Functional analysis of gene ontology (GO).

| Term | GO term | Subgroup |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0071345 | cellular response to cytokine stimulus | BP |

| GO:0019221 | cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | BP |

| GO:0032496 | response to lipopolysaccharide | BP |

| GO:0002237 | response to molecule of bacterial origin | BP |

| GO:0071216 | cellular response to biotic stimulus | BP |

| GO:0071222 | cellular response to lipopolysaccharide | BP |

| GO:0071219 | cellular response to molecule of bacterial origin | BP |

| GO:0048660 | regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation | BP |

| GO:0006979 | response to oxidative stress | BP |

| GO:0009617 | response to bacterium | BP |

| GO:0045121 | membrane raft | CC |

| GO:0098857 | membrane microdomain | CC |

| GO:0005788 | endoplasmic reticulum lumen | CC |

| GO:0005901 | caveola | CC |

| GO:0005819 | spindle | CC |

| GO:0031904 | endosome lumen | CC |

| GO:0044853 | plasma membrane raft | CC |

| GO:1904724 | tertiary granule lumen | CC |

| GO:0005925 | focal adhesion | CC |

| GO:0030055 | cell-substrate junction | CC |

| GO:0005125 | cytokine activity | MF |

| GO:0005126 | cytokine receptor binding | MF |

| GO:0030546 | signaling receptor activator activity | MF |

| GO:0030545 | signaling receptor regulator activity | MF |

| GO:0048018 | receptor ligand activity | MF |

| GO:0008009 | chemokine activity | MF |

| GO:0042379 | chemokine receptor binding | MF |

| GO:0031726 | CCR1 chemokine receptor binding | MF |

| GO:0001664 | G protein-coupled receptor binding | MF |

| GO:0019207 | kinase regulator activity | MF |

Table 1.

Primers for qRT–PCR.

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TNF-α | GACAAGCCTGTAGCCCATGT GGAGGTTGACCTTGGTCTGG |

| IL-6 | CCACCGGGAACGAAAGAGAA GAGAAGGCAACTGGACCGAA |

| IL-1β | AGAAGTACCTGAGCTCGCCA AGGTCCTGGAAGGAGCACTT |

| GAPDH | CCTCGTCCCGTAGACAAAATG TGAGGTCAATGAAGGGGTCGT |

5.4. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular docking of 4NQO and ethanol with the top six core target proteins (TNF, IL6, TP53, JUN, IL1B, AKT1) was performed using Discovery Studio 2019 Client. The binding capability between ligands and receptors was represented by LibdockScore, and the LibdockScore results were plotted as a heatmap (Fig. 4A). The results indicated that TNF&4NQO and TNF&EtOH exhibited the highest LibdockScore values. We further visualized and analyzed the 2D and 3D schematic diagrams of these two complexes (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation results.

(A) Heatmap of LibdockScore results.

(B) 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of the TNF&4NQO and TNF&EtOH complex systems.

(C) MD simulations of TNF&4NQO and TNF&EtOH complexes showing RMSD and Rg calculations, respectively.

(D) MD simulations of TNF&4NQO and TNF&EtOH complexes showing H-Bonds, RMSF, and SASA calculations, respectively. Red: TNF&4NQO; Black: TNF&EtOH.

(E) Intracellular DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity was measured using a ROS assay kit.

Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

To determine the stability of receptor-ligand complexes, molecular dynamics simulations of TNF&4NQO and TNF&EtOH were performed (Fig. 4C–D). The root means square deviation (RMSD) curve of TNF&4NQO remained relatively stable within 0–65 ns, while TNF&EtOH exhibited protein-ligand separation fluctuations after 2 ns. The radius of gyration (RG) of TNF&4NQO showed stability during the first 50 ns, whereas TNF&EtOH failed to form a stable complex. TNF&4NQO formed 0–5 hydrogen bonds, and TNF&EtOH formed almost no hydrogen bonds. Root means square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis indicated greater residue-level flexibility in TNF&4NQO compared to TNF&EtOH. Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) analysis revealed higher stability in TNF&4NQO than in TNF&EtOH. These results demonstrate that 4NQO canbind to TNF, while ethanol cannot bind to TNF. Subsequently, we measured reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in NE-1 cells and ethanol-treated groups. We observed significantly increased DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity in NE-1 cells following ethanol exposure. These results demonstrate that ethanol promotes the secretion of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α through ROS accumulation.

5.5. 4NQO combine with EtOH to induce inflammatory changes and DNA damage in NE-1 cells

We detected the mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in each group of cells using qRT-PCR. The results showed no significant trends in the EtOH group compared to the NE-1 group, while the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA in the 4NQO/EtOH group was significantly higher than that in both the 4NQO group and the EtOH group (Fig. 5A). Simultaneously, immunofluorescence results indicated that the expression of the DNA damage marker protein γ-H2AX in the 4NQO/EtOH group was significantly increased compared to the 4NQO group and the EtOH group (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

4NQO combine with EtOH to induce inflammatory changes and DNA damage in NE-1 cells after 20 passages.

(A) Relative mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β detected by qRT-PCR.

(B) Immunofluorescence detection of γ-H2AX expression. Green fluorescence indicates γ-H2AX, and blue fluorescence represents DAPI.

Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

5.6. 4NQO combine with EtOH to induce inflammatory changes and DNA damage in mice

ELISA analysis of mouse serum demonstrated significantly elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the 4NQO/EtOH group co-treatment group compared to both the 4NQO group and EtOH group (Fig. 6A). In parallel, immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that γ-H2AX—a DNA damage marker—was upregulated in esophageal tissues of mice treated with 4NQO/EtOH, 4NQO alone, or EtOH alone, indicating DNA damage induction by both combinatorial and single-agent treatments (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

4NQO combine with EtOH to induce inflammatory changes and DNA damage in mice.

(A) Inflammatory factor expression (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) in mouse serum.

(B) γ-H2AX staining in mouse esophageal tissues.

Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

5.7. 4NQO combine with EtOH to activate the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway in NE-1 cells

Subsequently, we analyzed the protein expression levels of the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway with the most significant enrichment differences. Western blot results demonstrated that TNF-α, TRAF2, and p–NF–κBp65 protein expression in the 4NQO/EtOH group was significantly elevated compared to the 4NQO group and EtOH groups, whereas total NF-κB p65 showed no significant alterations (Fig. 7A). To further validate the plausibility of the TNF-α pathway, we employed SPD304 (a TNF-α inhibitor), which induces dissociation of tumor necrosis factor trimers, thereby blocking its interaction with receptors. Using the CCK-8 assay, we assessed the effects of SPD304 on 4NQO/EtOH-treated cells. Results demonstrated a 24-h IC50 value of 6.537 μmol/L for SPD304 (Fig. 7B). Consequently, we treated the 4NQO/EtOH group with 6 μmol/L SPD304 for 24 h, observing significantly reduced migration and invasion capacities (Fig. 7C–D).

Fig. 7.

4NQO combine with ethanol to activate the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway in NE-1 cells.

(A) Western blot analysis of TNF-α, TRAF2, phospho–NF–κB p65 (p–NF–κBp65), and total NF-κB p65 protein expression.

(B) Cell viability of NE-1 cells treated with varying concentrations of SPD304 determined by CCK-8 assay.

(C) Cell migration ability assessed by wound healing assay.

(D) Cell invasion capacity evaluated using Transwell assay.

Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

5.8. 4NQO combine with EtOH to induce the expression of TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway-associated proteins in a mouse model

We performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect the expression of TNF-α, TRAF2, and p–NF–κB in mouse esophageal tissues. Our results revealed significantly stronger positive staining in the 4NQO/EtOH group compared to the 4NQO group and EtOH groups (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Expression of TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway-associated proteins in mouse. esophageal tissues. The expression of TNF-α, TRAF2, and p–NF–κB in mouse esophageal tissues was visualized via IHC staining under microscopic examination. Each data set represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

6. Discussion

Epidemiological studies show that alcohol drinking and smoking are important factors causing the occurrence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [28,29], and their Collaborative effect significantly increases the risk of esophageal cancer [30]. Studies found that, compared to moderate smoking without alcohol drinking and moderate drinking without smoking, simultaneous exposure to the same moderate levels of both factors leads to a 12 to 19 times increase in cancer risk in males and females, respectively [31]. Some researchers have proposed that tobacco and light-to-moderate alcohol interact, increasing the risk of esophageal cancer through a Collaborative multiplicative effect [32]. Our in vitro studies demonstrated that, compared with the single-exposure groups, 4NQO combined with EtOH treatment significantly enhanced cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities while promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is a critical process involving the transformation of epithelial cells into a mesenchymal phenotype [33]. When normally differentiated epithelial cells acquire EMT characteristics, this may trigger tumorigenesis and confer invasive properties [34]. In vivo experiments revealed that this combined treatment reduced body weight in mice and exacerbated esophageal carcinogenesis. Furthermore, 4NQO combined with EtOH treatment exhibited significantly elevated expression of N-cadherin and Vimentin, indicating the initiation of EMT in mouse esophageal tumor tissues, consistent with the in vitro findings [35].

We applied network toxicology to investigate the targets of the Collaborative effects of 4NQO and ethanol in esophageal carcinogenesis. Six core hub genes with the strongest associations were identified: TNF, IL-6, TP53, JUN, IL-1β, and AKT1, which are closely associated with inflammatory responses and DNA damage. GO enrichment analysis demonstrated that 4NQO combined with ethanol primarily functions through modulating cytokine stimulation and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggest that 4NQO directly binds to TNF, while ethanol exhibits no binding affinity for TNF. However, upon further review of the literature, it was noted that ethanol can promote the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) [36,37]., which was also confirmed in our study. Furthermore, in intraexperiment demonstrated that 4NQO combined with ethanol significantly elevated inflammatory levels in NE-1 cells. Most notably, after 24 weeks of exposure to 4NQO combined with EtOH, widespread inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the submucosa of mice, accompanied by significantly increased serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. Chronic inflammation drives tumorigenesis via DNA damage [[38], [39], [40]]. We observed that 4NQO combined with ethanol (EtOH) exacerbated DNA damage in both mouse esophageal epithelial tissues and NE-1 cells. This indicates that chronic inflammation promotes DNA damage, which feedback-activates inflammation-associated pathways, forming a vicious cycle that ultimately drives malignant transformation of the esophageal epithelium.

KEGG pathway analysis further demonstrated that the co-exposure of 4NQO-EtOH in esophageal cancer progression primarily involves pathways in cancer, the TNF signaling pathway, and the IL-17 signaling pathway. Mechanistically, the TNF signaling pathway mediates systemic inflammatory responses [41]. Upon TNF-α binding to TNFR1, it recruits TRADD and triggers interactions with E3 ubiquitin ligases (cIAP1/2), TRAF2, and serine-threonine kinase RIP1, leading to NF-κB pathway activation [42,43]. DNA damage also activates the NF-κB pathway [44]. Activated NF-κB participates in inflammatory responses and directly induces the production of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α、IL-6和IL-1β [45]. Our study revealed that the Collaborative action of 4NQO and ethanol (EtOH) significantly upregulates key nodal proteins of the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB pathway in NE-1 cells compared to 4NQO or EtOH monotherapy. Furthermore, the addition of the TNF-α inhibitor mitigated the 4NQO/EtOH-induced migratory and invasive potential of esophageal epithelial cells. Consistent protein alterations were observed in mouse esophageal tissues under 4NQO-EtOH synergy, demonstrating that the Collaborative interaction between 4NQO and ethanol (EtOH) induces esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) initiation via activation of the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway.

In conclusion, this study integrates network toxicology with in vivo and in vitro experiments to elucidate that 4NQO combine with EtOH to synergistically activate the TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby inducing ESCC. These findings provide critical clues and a theoretical basis for understanding the Collaborative effects of smoking and alcohol consumption in ESCC pathogenesis and developing novel prevention and treatment strategies.

6.1. Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, only a single normal esophageal epithelial cell line (NE-1) was used in the in vitro experiments, and the results were not validated across multiple esophageal epithelial cell lines. Second, although this study focused on the KEGG-enriched TNF-α/TRAF2/NF-κB pathway, which exhibited the most significant enrichment, pathways such as IL-17 and MAPK are also critically involved in ESCC pathogenesis. Evidence suggests that IL-17 and TNF can synergistically amplify inflammatory feedback loops [46]. Furthermore, TNF-α itself can activate MAPK signaling, thereby exacerbating inflammation [47]. The complex interplay and potential cascade effects of these pathways in ESCC development warrant further investigation. Given that the biological effects of EtOH are multifaceted and complex, future studies are warranted to elucidate its precise mechanisms.

Materials availability

No new unique reagents were generated in this study.

Author contributions

J.Y: writing-original draft, methodology, conceptualization. J.G and Y.W: validation, data collation. T.X and S.H: data collation, investigation. C.Z and M.H: methodology, investigation, Experimental data analysis. P.Z and R,L: Methodology, Investigation, Data collation. Z.W and J.L: Writing-review, editing, supervision and project management. All authors contributed to writing and providing feedback.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank SuanYichou Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) for their technical assistance with Fig. 4.

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82274593); Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (H2023206137); S&T Program of Hebei (223777122D); Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (BJK2024113); Hebei Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Subjects Programme (2024110) and Hebei Medical University 2024 Innovative Experimental Programme for Undergraduates (USIP2024063) were supported.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2025.102187.

Contributor Information

Zhongbing Wu, Email: 19001631@hebmu.edu.cn.

Jing Li, Email: lijing@hebmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Bray F., Laversanne M., Sung H., et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024;74(3):229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radojicic J., Zaravinos A., Spandidos D.A. HPV, KRAS mutations, alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking effects on esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma carcinogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 2012;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2011.8737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prabhu A., Obi K.O., Rubenstein J.H. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109(6):822–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht S.S., Hatsukami D.K. Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2022;22(3):143–155. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00423-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips D.H. Smoking-related DNA and protein adducts in human tissues. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(12):1979–2004. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.12.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen K.A., Depledge L.N., Bian L., et al. Polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase gamma are critical to tobacco-mimicking oral carcinogenesis in mice. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2023;11(9) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-007110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shishodia G., Toledo R.R.G., Rong X., et al. 4NQO enhances differential activation of DNA repair proteins in HPV positive and HPV negative HNSCC cells. Oral Oncol. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spuldaro T.R., Wagner V.P., Nör F., et al. Periodontal disease affects oral cancer progression in a surrogate animal model for tobacco exposure. Int. J. Oncol. 2022;60(6) doi: 10.3892/ijo.2022.5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z., Guan B., Men T., et al. Comparable molecular alterations in 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide-induced oral and esophageal cancer in mice and in human esophageal cancer, associated with poor prognosis of patients. In Vivo (Athens) 2013;27(4):473–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman N.D., Murray L.J., Kamangar F., et al. Alcohol intake and risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a pooled analysis from the BEACON consortium. Gut. 2011;60(8):1029–1037. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.233866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seitz H.K., Stickel F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7(8):599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratna A., Mandrekar P. Alcohol and cancer: mechanisms and therapies. Biomolecules. 2017;7(3) doi: 10.3390/biom7030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rumgay H., Murphy N., Ferrari P., et al. Alcohol and cancer: epidemiology and biological mechanisms. Nutrients. 2021;13(9) doi: 10.3390/nu13093173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T., Chen Z.J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215(5):1287–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wunderlich R., Ruehle P.F., Deloch L., et al. Interconnection between DNA damage, senescence, inflammation, and cancer. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2017;22(2):348–369. doi: 10.2741/4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthupalani S., Annamalai D., Feng Y., et al. IL-1β transgenic mouse model of inflammation driven esophageal and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39907-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao J., Cui Q., Fan W., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis in a mouse model deciphers cell transition states in the multistep development of esophageal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):3715. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17492-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barros E.M., Mcintosh S.A., Savage K.I. The DNA damage induced immune response: implications for cancer therapy. DNA Repair. 2022;120 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2022.103409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins J.L., Lan L., Zou L. DNA repair defects in cancer and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dev. 2022;36(5–6):278–293. doi: 10.1101/gad.349431.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes J.S., Best K., Belknap J.K., et al. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol. Behav. 2005;84(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiegers T.C., Davis A.P., Wiegers J., et al. Integrating AI-powered text mining from PubTator into the manual curation workflow at the comparative toxicogenomics database. Database. 2025:2025. doi: 10.1093/database/baaf013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayers E.W., Bolton E.E., Brister J.R., et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D20–d26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stelzer G., Rosen N., Plaschkes I., et al. The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2016;54 doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5. 1.30.1-1.30.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Nastou K.C., et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–d612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye B., Chen P., Lin C., et al. Study on the material basis and action mechanisms of sophora davidii (Franch.) skeels flower extract in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023;317 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X., Wei S., Niu S., et al. Network pharmacology prediction and molecular docking-based strategy to explore the potential mechanism of Huanglian Jiedu Decoction against sepsis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;144 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moody S., Senkin S., Islam S.M.A., et al. Mutational signatures in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma from eight countries with varying incidence. Nat. Genet. 2021;53(11):1553–1563. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conway E., Wu H., Tian L. Overview of risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15(23) doi: 10.3390/cancers15235604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui R., Kamatani Y., Takahashi A., et al. Functional variants in ADH1B and ALDH2 coupled with alcohol and smoking synergistically enhance esophageal cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1768–1775. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castellsagué X., Muñoz N., De Stefani E., et al. Independent and joint effects of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of esophageal cancer in men and women. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;82(5):657–664. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<657::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee C.H., Wu D.C., Lee J.M., et al. Carcinogenetic impact of alcohol intake on squamous cell carcinoma risk of the oesophagus in relation to tobacco smoking. Eur. J. Cancer. 2007;43(7):1188–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lengrand J., Pastushenko I., Vanuytven S., et al. Pharmacological targeting of netrin-1 inhibits EMT in cancer. Nature. 2023;620(7973):402–408. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klymkowsky M.W., Savagner P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: a cancer researcher's conceptual friend and foe. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174(5):1588–1593. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu W., Kang Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev. Cell. 2019;49(3):361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dukić M., Radonjić T., Jovanović I., et al. Alcohol, inflammation, and microbiota in alcoholic liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(4) doi: 10.3390/ijms24043735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teschke R. Hemochromatosis: ferroptosis, ROS, gut microbiome, and clinical challenges with alcohol as confounding variable. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024;25(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms25052668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kay J., Thadhani E., Samson L., et al. Inflammation-induced DNA damage, mutations and cancer. DNA Repair. 2019;83 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kidane D., Chae W.J., Czochor J., et al. Interplay between DNA repair and inflammation, and the link to cancer. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014;49(2):116–139. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.875514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meira L.B., Bugni J.M., Green S.L., et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008;118(7):2516–2525. doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley J.R. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J. Pathol. 2008;214(2):149–160. doi: 10.1002/path.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu H., Lin L., Zhang Z., et al. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2020;5(1):209. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borghi A., Verstrepen L., Beyaert R. TRAF2 multitasking in TNF receptor-induced signaling to NF-κB, MAP kinases and cell death. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016;116:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mccool K.W., Miyamoto S. DNA damage-dependent NF-κB activation: NEMO turns nuclear signaling inside out. Immunol. Rev. 2012;246(1):311–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilmore T.D. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffin G.K., Newton G., Tarrio M.L., et al. IL-17 and TNF-α sustain neutrophil recruitment during inflammation through synergistic effects on endothelial activation. J. Immunol. 2012;188(12):6287–6299. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akhter N., Wilson A., Arefanian H., et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum stress promotes the expression of TNF-α in THP-1 cells by mechanisms involving ROS/CHOP/HIF-1α and MAPK/NF-κB pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(20) doi: 10.3390/ijms242015186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.