Abstract

A PCR assay was used to analyze endotracheal aspirates from preterm infants for Ureaplasma parvum versus U. urealyticum. U. parvum was detected more often than U. urealyticum. There was no significant difference or trend in the prevalence of either species between infants with or without bronchopulmonary dysplasia when isolated alone.

The major factor leading to high morbidity and mortality of preterm infants is pulmonary immaturity. This manifests as respiratory distress in the early neonatal period and can develop into bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), currently defined as a supplemental oxygen requirement at 36 weeks postmenstrual age, with characteristic radiographic findings (2). A recent survey reported that the incidence of BPD ranged from 67% among infants with birth weights of 500 to 750 g to <1% in infants weighing 1,250 to 2,500 g (2).

Development of BPD is multifactorial and is related to pulmonary immaturity, oxidant injury due to high levels of inspired oxygen, and volutrauma associated with mechanical ventilation. However, recent research has focused on the roles of perinatal infection and the inflammatory response as critical factors influencing chronic lung injury (7, 16). Particular attention has been paid to the role of Ureaplasma species, fastidious bacteria found in the lower genital tracts of 40 to 80% of asymptomatic women (4). Rates of vertical transmission range from 18 to 88%, varying inversely with gestational age (6, 8, 12, 24, 25). Ureaplasma spp. are the most common microorganisms isolated from inflamed placentas and the lower respiratory tracts of neonates and are proven causes of neonatal pneumonia (4). Since initial reports associating ureaplasmal colonization and development of BPD were published in 1988 (5, 23, 26), more than 30 studies have been conducted. Most, but not all, have supported this association, despite major changes in the pulmonary management of very-low-birth-weight infants, such as exogenous surfactant, antenatal corticosteroid administration, and high frequency ventilation.

Data from 16S rRNA sequencing led to classification of the 14 Ureaplasma serotypes into 2 biovars. Biovar 1 contains serotypes 1, 3, 6, and 14, while biovar 2 contains serotypes 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13. Recently, the two biovars were designated distinct species: biovar 1 became Ureaplasma parvum, and biovar 2 became U. urealyticum (10, 14, 15, 20-22). U. parvum is more common in clinical specimens, but both may occur simultaneously (1, 9, 17-19).

Differential serotype pathogenicity is well known among other pathogens, so it is plausible that differences might also occur in Ureaplasma spp. This might explain the reported differences in outcomes, such as BPD rates, after infection with Ureaplasma spp. We used PCR to analyze 181 isolates from mechanically ventilated, preterm infants who were colonized with Ureaplasma spp. to determine the relative frequencies of U. parvum and U. urealyticum in preterm infants with and without BPD.

Endotracheal aspirate (ETA) specimens collected between 1994 and 2003 from neonates with birth weights of <1,500 g and with respiratory distress that were culture positive for Ureaplasma spp. were studied. ETAs and broth subcultures were frozen at −70°C until tested. Two specimens from each infant were analyzed: the original aspirate and an aliquot of a positive broth subculture. A positive result from either specimen was considered evidence of Ureaplasma spp.

PCR was performed using primers directed towards the urease genes specific for Ureaplasma: primers U5s (sense primer, 5′-CAA TCT GCT CGT GAA GTA TTA C-3′) and U4a (antisense primer, 5′-ACG ACG TCC ATA AGC AAC AAC T-3′). PCR amplified a 429-bp DNA fragment by use of sample preparation and amplification procedures described by Blanchard et al. (3). For speciation, samples were hybridized in solution to a 32P-labeled, 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe for U. parvum, U5-4/1 (5′-AAA TTG ACT TGA TGA TCC TG-3′), and to a 32P-labeled, 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe for U. urealyticum, U5-4/2 (5′-ATT TGT TTC AAA TAA GTG G-3′), as described by Povlsen et al. (18). Hybridized samples were run on an acrylamide gel, dried, and developed on X-ray film. The hybrid products of the positive controls (serotype 3 for U. parvum and serotype 10 for U. urealyticum) and positive samples were run at the same rate, with the positive control signal for each respective species used as a reference point. Negative samples and negative controls (serotype 10 for U. parvum and serotype 3 for U. urealyticum) had no hybridized products and, therefore, no signal.

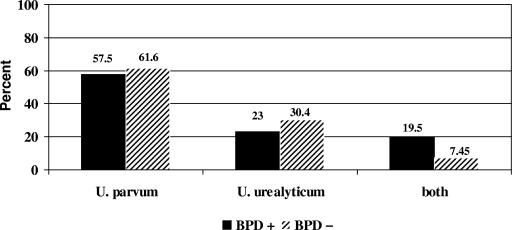

PCR results were matched with the clinical outcome of BPD (2). U. parvum was more common than U. urealyticum, but there was no difference in their relative occurrences in infants with or without BPD when isolated alone. However, both species were detected simultaneously in 17 infants with BPD versus only 7 infants without BPD, and this was a significant difference (Fig. 1). There were no differences in birth weight, severity of BPD, or other clinical and demographic variables between the two groups (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of Ureaplasma species distribution among 87 infants who developed BPD and 94 who did not develop BPD showed that U. parvum was detected in tracheal secretions more than twice as often as U. urealyticum. There was no differential association of either species with infants who developed BPD when isolated individually. Detection of both species simultaneously occurred significantly more often in infants with BPD (BPD +) than in those without this condition (BPD −) (17 versus 7 infants, respectively). Odds ratio, 3.02 (95% confidence interval, 1.19 to 7.69; P = 0.012).

Conclusions of other investigations have been mixed. Zheng et al. (27) evaluated 10 ureaplasmal isolates from neonatal cerebrospinal fluid specimens by using serotype-specific reagents and monoclonal antibodies. Seven isolates represented 5 of 14 serotypes and both genomic clusters, supporting the concept that invasiveness is not limited to one or a few serotypes. Isolates of the same serotype from different patients and isolates from different body sites within the same patient demonstrated size variation in serotype antigens expressed. Thus, many serotypes can be invasive, and antigen variability and host factors may be more important than serotype diversity.

Kim et al. (13) reported no differences in pregnancy outcome, chorioamnionitis, birth weight, gestational age, or neonatal morbidity in infants born to 77 women whose amniotic fluid contained ureaplasmas designated by species with PCR. In contrast, Abele-Horn et al. (1) found U. urealyticum to be dominant in women with pelvic inflammatory disease and those who had had a miscarriage, and U. urealyticum was associated with more adverse effects on birth weight, gestational age, and preterm delivery than was U. parvum.

Heggie et al. (11) found no differences between infants harboring U. parvum and those with U. urealyticum, with respect to occurrence of BPD. However, Abele-Horn et al. (1) reported that 10/18 (56%) infants colonized by U. urealyticum developed BPD versus 12/48 (25%) infants with U. parvum (P < 0.05).

We report here the largest evaluation of Ureaplasma spp. with the clinical outcome of BPD in 181 preterm infants over a 10-year period. We found no difference in BPD rates with either species alone. A significantly greater likelihood of BPD was observed when both species were detected together, but the numbers of infants involved were very small. Assessment of whether colonization by Ureaplasma spp. is associated with development of BPD was not an objective of this study, as we previously established this relationship in our neonatal intensive care unit (5). We analyzed a retrospective cohort of infants known to have positive endotracheal cultures for Ureaplasma spp.; however, ETA sampling was not universal during the study interval. Of those infants tested for ureaplasmas, most had a single ETA, so it is possible that other infants colonized with Ureaplasma spp. would have been detected had additional samples been tested.

To determine conclusively whether there is a differential pathogenicity of Ureaplasma spp., future studies will require a large sample size with universal sampling of the population by using multiple modality screening with culture and PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele-Horn, M., C. Wolff, P. Dressel, F. Pfaff, and A. Zimmermann. 1997. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum biovars with clinical outcome for neonates, obstetric patients, and gynecological patients with pelvic inflammatory disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1199-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancalari, E., N. Claure, and I. R. Sosenko. 2003. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: changes in pathogenesis, epidemiology and definition. Semin. Neonatol. 8:63-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard, A., J. Hentschel, L. Duffy, K. Baldus, and G. H. Cassell. 1993. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum by polymerase chain reaction in the urogenital tract of adults, in amniotic fluid, and in the respiratory tract of newborns. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17(Suppl. 1):S148-S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassell, G. H., K. B. Waites, and D. T. Crouse. 2001. Mycoplasmal infections, p. 733-767. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 5th ed. W. B. Saunders Co., Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 5.Cassell, G. H., K. B. Waites, D. T. Crouse, P. T. Rudd, K. C. Canupp, S. Stagno, and G. R. Cutter. 1988. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection of the lower respiratory tract with chronic lung disease and death in very-low-birth-weight infants. Lancet ii:>240-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua, K. B., Y. F. Ngeow, C. T. Lim, K. B. Ng, and J. K. Chye. 1999. Colonization and transmission of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis from mothers to full and preterm babies by normal vaginal delivery. Med. J. Malays. 54:242-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Dooy, J. J., L. M. Mahieu, and H. P. Van Bever. 2001. The role of inflammation in the development of chronic lung disease in neonates. Eur. J. Pediatr. 160:457-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinsmoor, M. J., R. S. Ramamurthy, and R. S. Gibbs. 1989. Transmission of genital mycoplasmas from mother to neonate in women with prolonged membrane rupture. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 8:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grattard, F., B. Soleihac, B. De Barbeyrac, C. Bebear, P. Seffert, and B. Pozzetto. 1995. Epidemiologic and molecular investigations of genital mycoplasmas from women and neonates at delivery. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 14:853-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harasawa, R. 1999. Genetic relationships among mycoplasmas based on the 16S-23S rRNA spacer sequence. Microbiol. Immunol. 43:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heggie, A. D., D. Bar-Shain, B. Boxerbaum, A. A. Fanaroff, M. A. O'Riordan, and J. A. Robertson. 2001. Identification and quantification of ureaplasmas colonizing the respiratory tract and assessment of their role in the development of chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:854-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kafetzis, D. A., C. L. Skevaki, V. Skouteri, S. Gavrili, K. Peppa, C. Kostalos, V. Petrochilou, and S. Michalas. 2004. Maternal genital colonization with Ureaplasma urealyticum promotes preterm delivery: association of the respiratory colonization of premature infants with chronic lung disease and increased mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1113-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, M., G. Kim, R. Romero, S. S. Shim, E. C. Kim, and B. H. Yoon. 2003. Biovar diversity of Ureaplasma urealyticum in amniotic fluid: distribution, intrauterine inflammatory response and pregnancy outcomes. J. Perinat. Med. 31:146-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong, F., G. James, Z. Ma, S. Gordon, W. Bin, and G. L. Gilbert. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Ureaplasma urealyticum—support for the establishment of a new species, Ureaplasma parvum. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1879-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong, F., Z. Ma, G. James, S. Gordon, and G. L. Gilbert. 2000. Species identification and subtyping of Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum using PCR-based assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1175-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyon, A. 2000. Chronic lung disease of prematurity. The role of intra-uterine infection. Eur. J. Pediatr. 159:798-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naessens, A., W. Foulon, J. Breynaert, and S. Lauwers. 1988. Serotypes of Ureaplasma urealyticum isolated from normal pregnant women and patients with pregnancy complications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:319-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Povlsen, K., J. S. Jensen, and I. Lind. 1998. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum by PCR and biovar determination by liquid hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3211-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Povlsen, K., P. Thorsen, and I. Lind. 2001. Relationship of Ureaplasma urealyticum biovars to the presence or absence of bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women and to the time of delivery. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:65-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson, J. A., L. A. Howard, C. L. Zinner, and G. W. Stemke. 1994. Comparison of 16S rRNA genes within the T960 and parvo biovars of ureaplasmas isolated from humans. Int J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:836-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson, J. A., G. W. Stemke, J. W. Davis, Jr., R. Harasawa, D. Thirkell, F. Kong, M. C. Shepard, and D. K. Ford. 2002. Proposal of Ureaplasma parvum sp. nov. and emended description of Ureaplasma urealyticum (Shepard et al. 1974) Robertson et al. 2001. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson, J. A., A. Vekris, C. Bebear, and G. W. Stemke. 1993. Polymerase chain reaction using 16S rRNA gene sequences distinguishes the two biovars of Ureaplasma urealyticum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:824-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez, P. J., and J. A. Regan. 1988. Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization and chronic lung disease in low birth weight infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 7:542-546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez, P. J., and J. A. Regan. 1990. Vertical transmission of Ureaplasma urealyticum from mothers to preterm infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 9:398-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syrogiannopoulos, G. A., K. Kapatais-Zoumbos, G. O. Decavalas, C. G. Markantes, V. A. Katsarou, and N. G. Beratis. 1990. Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization of full term infants: perinatal acquisition and persistence during early infancy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 9:236-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, E. E., H. Frayha, J. Watts, O. Hammerberg, M. A. Chernesky, J. B. Mahony, and G. H. Cassell. 1988. Role of Ureaplasma urealyticum and other pathogens in the development of chronic lung disease of prematurity. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 7:547-551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng, X., H. L. Watson, K. B. Waites, and G. H. Cassell. 1992. Serotype diversity and antigen variation among invasive isolates of Ureaplasma urealyticum from neonates. Infect. Immun. 60:3472-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]