Abstract

Background

Lymph node metastasis (LNM) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is associated with significantly worse prognosis, yet its detection and risk stratification remain challenging in clinical practice. This study aimed to investigate the correlation between clinical nodal status (cN) and pathological nodal status (pN) in HCC patients and to identify risk factors for LNM via the National Cancer Database (NCDB).

Methods

We identified HCC patients who underwent liver resection between 2004 and 2017 from the NCDB. Clinical and pathological variables were analyzed to assess the correlation between cN1 and pN1. Logistic regression models were used to identify risk factors for LNM and to evaluate the diagnostic performance of cN1 in predicting pN1.

Results

A total of 21,733 HCC patients who underwent liver resection were analyzed. Of these, 15,496 (71%) were male, and the median age was 65 years. Only 1.4% of patients had cN1 disease. Among the 7,612 patients who underwent lymph node excision (LNE), 3.3% had pN1. Clinical LNM (cN1) demonstrated high specificity (99.2%) but low sensitivity (46.2%) in detecting pN1. Logistic regression analysis revealed that younger age, female sex, fibrolamellar histology, combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA), advanced clinical T stage, and higher tumor grade were significant risk factors for pN1.

Conclusions

Tumor characteristics, patient demographics, and specific histological subtypes significantly influence the risk of pN1 in patients with resectable HCC. Given the low sensitivity of cN1, LNE should be considered for high-risk patients to improve diagnostic accuracy and inform treatment decisions. These findings underscore the importance of integrating risk factors into clinical practice and highlight the need for further research to refine predictive models for LNM in HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Lymph node metastasis, Risk factors

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy and is typically characterized by hematogenous spread. As a result, lymphatic dissemination has received comparatively less attention, partly due to its stronger association with adenocarcinomas [1]. However, emerging evidence suggests that lymph node metastasis (LNM), although relatively uncommon, plays a critical role in the prognosis of patients with HCC. Large-scale cohort studies have reported LNM rates of approximately 1–3%, particularly in patients with aggressive histological subtypes such as fibrolamellar HCC and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA) [2–5]. In contrast, autopsy studies have demonstrated LNM in up to 25% of HCC patients, suggesting that its true prevalence may be underrecognized in clinical practice [6].

Several studies have suggested worsened survival outcomes in HCC patients undergoing LN dissection (LND), raising concerns about its role during surgical resection [2, 7, 8]. Despite potential selection biases, with the absence of proven adjuvant chemotherapy, local treatments for LNM in HCC patients face considerable limitations. However, a clear survival difference between patients with localized LNM (N1) and those with distant metastasis (M1) has been reported. Furthermore, patients with LNM are at increased risk of HCC recurrence after surgical resection and potentially benefit from adjuvant immunotherapy [9]. This highlights the need for ongoing efforts to investigate factors associated with LNM and select appropriate treatment candidates, especially in the context of the ongoing development of new therapeutic agents.

LNM is a significant prognostic factor correlated with poor survival in HCC patients, leading to its classification as stage IVA regardless of T stage according to the AJCC 8th edition [4, 10–12]. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted to analyze risk factors associated with LNM, revealing various correlates, including age, race, tumor size, T stage, histologic grade, and vascular invasion [2, 5, 8, 13, 14]. However, LND is generally not performed in HCC surgery, which results in a limited number of studies investigating the correlation between clinical nodal status (cN1) and pathological nodal status (pN1). Additionally, cases confirmed as pN1 are rare, making it necessary to conduct large-scale cohort studies to examine the concordance between cN1 and pN1. This study aims to utilize the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to investigate the correlation between cN1 and pN1 and to analyze various clinical data, including pathologic subtypes, to discern risk factors associated with LNM.

Methods

Data source

The NCDB is a joint project of the Committee on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The NCDB is a national oncology outcomes database. It accounts for approximately 70% of new cancer cases in the United States and has records for more than 34 million patients [15]. This analysis of a publicly available deidentified dataset was exempt from the institutional review board.

Patients

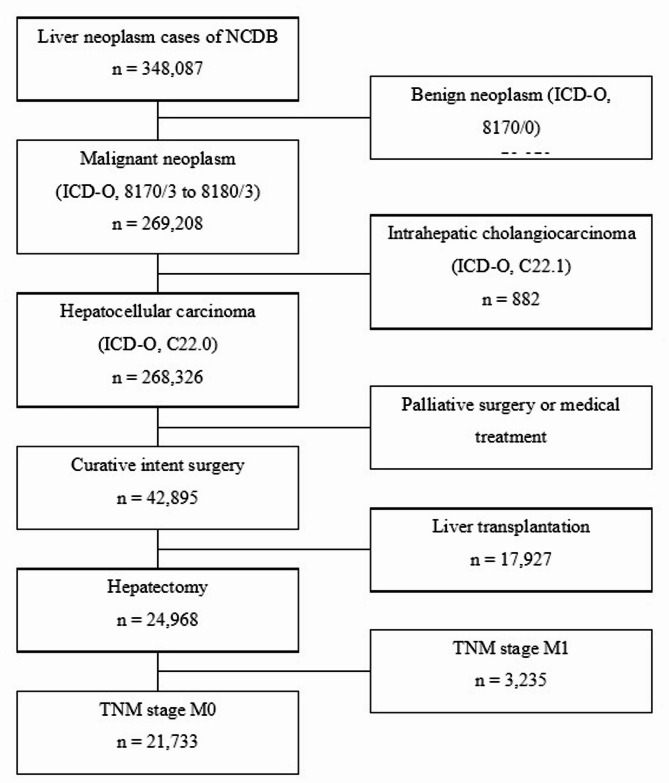

From 2004 to 2017, a total of 348,087 patients were identified in the full NCDB database. After excluding non-HCC patients, 269,208 patients remained. After those with metastatic cancer were excluded, 268,326 patients remained. Among them, 42,895 patients underwent liver resection. After the exclusion of transplant recipients, 24,968 patients remained. Finally, after those with distant metastasis were excluded, 21,733 patients were included in the study. (Fig. 1) Patients meeting the following criteria were selected using the following codes: those with a PRIMARY_SITE value of C22.0, encompassing HCC, combined cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA), clear cell type, fibrolamellar, pleomorphic type, sarcomatoid, or spindle cell variant, as well as an RX_SUMM_SURG_PRIM_SITE value ranging from 20 to 75, indicating hepatectomy. Patients meeting any of the following criteria were excluded from the analysis: patients with distant metastases and recipients of liver transplantation. LN excision (LNE) was defined as the evaluation of one or more LNs, which included LN sampling and LND.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart of patient selection

Variables analyzed

The analyzed variables included age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, income, facility type, institution location, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, cirrhosis, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, tumor size, cTNM stage, pTNM stage, Charlson comorbidity index, grade, and histology. All variables were extracted from the NCDB participant user file.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were summarized via descriptive statistics stratified by cN stage. Continuous variables are presented as the means (standard deviations, SDs) and medians (interquartile ranges, IQRs), whereas categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages) (Table 1). Comparisons between groups were performed via the Kruskal‒Wallis rank sum test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi‒square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, with the latter employing simulated p values based on 2000 replicates.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Overall N = 21,7331 |

N0 N = 18,9181 |

N1 N = 2681 |

Unknown N = 2,5471 |

p value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65 (58, 72) | 66 (58, 72) | 61 (54, 69) | 65 (56, 73) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.292 | ||||

| Male | 15,496 (71%) | 13,524 (71%) | 188 (70%) | 1,784 (70%) | |

| Female | 6,237 (29%) | 5,394 (29%) | 80 (30%) | 763 (30%) | |

| Race and Ethnicity | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1,721 (8.2%) | 1,515 (8.2%) | 18 (6.9%) | 188 (7.8%) | |

| White | 12,904 (61%) | 11,156 (61%) | 178 (69%) | 1,570 (65%) | |

| Black | 3,212 (15%) | 2,819 (15%) | 42 (16%) | 351 (14%) | |

| Asian + Others | 3,215 (15%) | 2,878 (16%) | 21 (8.1%) | 316 (13%) | |

| Unknown | 681 | 550 | 9 | 122 | |

| Tumor Size | 50 (31, 82) | 49 (30, 80) | 76 (45, 120) | 55 (35, 95) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1,303 | 1,079 | 21 | 203 | |

| AJCC Clinical T | < 0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 11,000 (61%) | 10,702 (62%) | 82 (33%) | 216 (49%) | |

| T2 | 4,018 (22%) | 3,864 (22%) | 44 (18%) | 110 (25%) | |

| T3 | 2,487 (14%) | 2,297 (13%) | 95 (38%) | 95 (21%) | |

| T4 | 486 (2.7%) | 433 (2.5%) | 30 (12%) | 23 (5.2%) | |

| Unknown | 3,742 | 1,622 | 17 | 2,103 | |

| AJCC Path T | < 0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 9,521 (51%) | 8,741 (53%) | 59 (30%) | 721 (43%) | |

| T2 | 5,522 (30%) | 4,975 (30%) | 45 (23%) | 502 (30%) | |

| T3 | 2,631 (14%) | 2,216 (13%) | 65 (33%) | 350 (21%) | |

| T4 | 838 (4.5%) | 704 (4.2%) | 31 (16%) | 103 (6.1%) | |

| Unknown | 3,221 | 2,282 | 68 | 871 | |

| AJCC Path N | < 0.001 | ||||

| N0 | 7,360 (97%) | 6,303 (98%) | 53 (38%) | 1,004 (94%) | |

| N1 | 252 (3.3%) | 100 (1.6%) | 86 (62%) | 66 (6.2%) | |

| Unknown | 14,121 | 12,515 | 129 | 1,477 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 11,066 (51%) | 9,389 (50%) | 165 (62%) | 1,512 (59%) | |

| 1 | 5,784 (27%) | 5,123 (27%) | 61 (23%) | 600 (24%) | |

| 2 | 2,509 (12%) | 2,265 (12%) | 22 (8.2%) | 222 (8.7%) | |

| 3 | 2,374 (11%) | 2,141 (11%) | 20 (7.5%) | 213 (8.4%) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 4,019 (25%) | 3,508 (25%) | 20 (11%) | 491 (24%) | |

| 2 | 8,509 (53%) | 7,349 (53%) | 89 (48%) | 1,071 (52%) | |

| 3 | 3,312 (21%) | 2,797 (20%) | 68 (37%) | 447 (22%) | |

| 4 | 248 (1.5%) | 177 (1.3%) | 7 (3.8%) | 64 (3.1%) | |

| Unknown | 5,645 | 5,087 | 84 | 474 | |

| Education (% NO HSD) | 0.419 | ||||

| 15.3% + | 5,070 (27%) | 4,394 (27%) | 50 (22%) | 626 (27%) | |

| 9.1 − 15.2% | 5,364 (28%) | 4,642 (29%) | 63 (28%) | 659 (28%) | |

| 5.0 − 9.0% | 4,918 (26%) | 4,224 (26%) | 59 (26%) | 635 (27%) | |

| < 5.0% | 3,504 (19%) | 3,015 (19%) | 53 (24%) | 436 (19%) | |

| Unknown | 2,877 | 2,643 | 43 | 191 | |

| Income | 0.014 | ||||

| < $46,277 | 3,660 (19%) | 3,126 (19%) | 32 (14%) | 502 (21%) | |

| $46,277 - $57,856 | 3,912 (21%) | 3,365 (21%) | 48 (21%) | 499 (21%) | |

| $57,857 - $74,062 | 4,438 (24%) | 3,817 (24%) | 55 (24%) | 566 (24%) | |

| $74,063 + | 6,804 (36%) | 5,934 (37%) | 90 (40%) | 780 (33%) | |

| Unknown | 2,919 | 2,676 | 43 | 200 | |

| Facility Type | 0.129 | ||||

| Non Academic | 9,090 (42%) | 7,876 (42%) | 126 (47%) | 1,088 (43%) | |

| Academic | 12,643 (58%) | 11,042 (58%) | 142 (53%) | 1,459 (57%) | |

| Location | < 0.001 | ||||

| Northeast | 5,112 (24%) | 4,527 (25%) | 59 (25%) | 526 (22%) | |

| Midwest | 4,527 (22%) | 3,941 (22%) | 61 (26%) | 525 (22%) | |

| South | 7,653 (37%) | 6,588 (36%) | 89 (38%) | 976 (40%) | |

| West | 3,636 (17%) | 3,215 (18%) | 26 (11%) | 395 (16%) | |

| Unknown | 805 | 647 | 33 | 125 | |

| MELD | 8 (7, 13) | 8 (7, 13) | 8 (7, 14) | 8 (7, 14) | 0.889 |

| Unknown | 15,166 | 12,700 | 197 | 2,269 | |

| Fibrosis | 0.230 | ||||

| 0–4 | 2,699 (58%) | 2,380 (58%) | 27 (61%) | 292 (62%) | |

| 5–6 | 1,929 (42%) | 1,732 (42%) | 17 (39%) | 180 (38%) | |

| Unknown | 17,105 | 14,806 | 224 | 2,075 | |

| AFP | 0.005 | ||||

| Negative | 4,648 (41%) | 4,072 (41%) | 51 (35%) | 525 (37%) | |

| Positive | 6,728 (59%) | 5,755 (59%) | 96 (65%) | 877 (63%) | |

| Unknown | 10,357 | 9,091 | 121 | 1,145 | |

| Histology | < 0.001 | ||||

| HCC, NOS | 20,706 (95%) | 18,108 (96%) | 218 (81%) | 2,380 (93%) | |

| HCC, fibrolamellar | 272 (1.3%) | 200 (1.1%) | 30 (11%) | 42 (1.6%) | |

| HCC, scirrhous | 51 (0.2%) | 44 (0.2%) | 2 (0.7%) | 5 (0.2%) | |

| HCC, spindle cell variant | 46 (0.2%) | 40 (0.2%) | 2 (0.7%) | 4 (0.2%) | |

| HCC, clear cell type | 419 (1.9%) | 366 (1.9%) | 5 (1.9%) | 48 (1.9%) | |

| HCC, pleomorphic type | 10 (< 0.1%) | 6 (< 0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.2%) | |

| HCC, Comb HCC-CCA | 229 (1.1%) | 154 (0.8%) | 11 (4.1%) | 64 (2.5%) |

1 Median (Q1, Q3); n (%)

2 Kruskal‒Wallis rank sum test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s Exact Test for Count Data with simulated p value (based on 2000 replicates)

Logistic regression models were employed to identify factors associated with cN1 and pN1 status among patients who underwent LNE. Covariates were selected a priori and included in the full model as specified in Tables 2 and 3. Model diagnostics were thoroughly assessed, including checks for multicollinearity via variance inflation factors, goodness-of-fit via the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and evaluation of influential data points through Cook’s distance.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for variables related to cN1 and pN1

| cN1 | pN1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| p value | OR1 | 95% CI1 | p value | p value | OR1 | 95% CI1 | p value | |

| Age (10 Years) | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.82, 0.83 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.78, 0.98 | 0.038 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Female | < 0.001 | 1.46 | 1.44, 1.47 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.45 | 1.14, 2.04 | 0.012 |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | — | — | — | — | ||||

| White | 0.003 | 1.60 | 1.56, 1.64 | 0.017 | 0.066 | 1.81 | 0.92, 3.41 | 0.076 |

| Black | 0.027 | 1.43 | 1.39, 1.47 | 0.099 | 0.566 | 1.34 | 0.54, 2.38 | 0.432 |

| Asian + Others | 0.916 | 0.96 | 0.93, 0.99 | 0.849 | 0.724 | 1.06 | 0.45, 2.20 | 0.886 |

| Education (% NO HSD) | ||||||||

| 15.3% + | — | — | — | — | ||||

| 9.1 − 15.2% | 0.561 | 0.88 | 0.87, 0.90 | 0.337 | 0.512 | 0.83 | 0.52, 1.21 | 0.379 |

| 5.0 − 9.0% | 0.008 | 1.21 | 1.19, 1.24 | 0.165 | 0.147 | 1.11 | 0.65, 1.61 | 0.649 |

| < 5.0% | 0.038 | 1.07 | 1.05, 1.10 | 0.673 | 0.075 | 0.97 | 0.51, 1.49 | 0.910 |

| Income | ||||||||

| < $46,277 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| $46,277 - $57,856 | 0.747 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.00 | 0.924 | 0.683 | 0.92 | 0.46, 1.19 | 0.747 |

| $57,857 - $74,062 | 0.308 | 1.06 | 1.04, 1.08 | 0.672 | 0.496 | 0.92 | 0.57, 1.46 | 0.736 |

| $74,063 + | 0.270 | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.12 | 0.563 | 0.165 | 1.05 | 0.56, 1.56 | 0.842 |

| Histology | ||||||||

| HCC, NOS | — | — | — | — | ||||

| HCC, fibrolamellar | < 0.001 | 7.46 | 7.28, 7.65 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 8.58 | 4.14, 13.95 | < 0.001 |

| HCC, scirrhous | 0.072 | 2.89 | 2.63, 3.16 | 0.154 | 0.112 | 2.16 | 0.20, 5.77 | 0.341 |

| HCC, spindle cell variant | < 0.001 | 3.98 | 3.77, 4.20 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 3.60 | 1.65, 11.99 | 0.010 |

| HCC, clear cell type | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01 | < 0.001 | 0.971 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 0.980 |

| HCC, pleomorphic type | 0.016 | 6.94 | 6.04, 7.96 | 0.082 | 0.043 | 22.58 | 0.66, 652.35 | 0.048 |

| HCC, Comb HCC-CCA | < 0.001 | 4.44 | 4.32, 4.56 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 4.37 | 2.06, 6.79 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor Size | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 | 0.030 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 | 0.629 |

| AJCC Clinical T | ||||||||

| T1 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| T2 | < 0.001 | 1.28 | 1.27, 1.30 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 1.50 | 1.04, 2.28 | 0.042 |

| T3 | < 0.001 | 2.89 | 2.85, 2.93 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.92 | 2.28, 4.63 | < 0.001 |

| T4 | < 0.001 | 4.05 | 3.97, 4.14 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 4.08 | 1.97, 5.95 | < 0.001 |

| AFP | ||||||||

| Negative | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Positive | < 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | 0.919 | 0.991 | 0.97 | 0.71, 1.35 | 0.876 |

| Facility Type | ||||||||

| Non Academic | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Academic | < 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.84, 0.86 | 0.069 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.64, 1.20 | 0.714 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Northeast | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Midwest | 0.018 | 1.07 | 1.06, 1.09 | 0.571 | 0.161 | 1.05 | 0.59, 1.40 | 0.830 |

| South | 0.190 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.971 | 0.319 | 1.11 | 0.65, 1.43 | 0.618 |

| West | 0.001 | 0.57 | 0.55, 0.58 | < 0.001 | 0.049 | 0.58 | 0.30, 0.88 | 0.048 |

| Grade | ||||||||

| 1 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| 2 | < 0.001 | 2.23 | 2.19, 2.28 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.83 | 1.51, 4.93 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | < 0.001 | 5.05 | 4.95, 5.16 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 6.51 | 3.55, 11.92 | < 0.001 |

| 4 | < 0.001 | 5.47 | 5.28, 5.67 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 10.09 | 2.98, 18.72 | < 0.001 |

1 OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

Table 3.

Accuracy, prevalence, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of the cN stage relative to the pN stage

| Histology | True Negatives | False Positives | False Negatives | True Positives | Accuracy | Balanced Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC, NOS | 5974 | 47 | 72 | 57 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 0.99 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.55 |

| HCC, fibrolamellar | 94 | 1 | 19 | 19 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.95 |

| HCC, scirrhous | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.94 | 0.50 |

| HCC, spindle cell variant | 15 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

| HCC, clear cell type | 126 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.99 | — | 0.99 | — | — | — |

| HCC, pleomorphic type | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | — | — |

| HCC, Comb HCC-CCA | 76 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 0.70 |

An analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of cN staging for predicting pN status by histology (Table 3). The performance metrics included accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of true positives (patients correctly classified as pN1), and specificity was defined as the proportion of true negatives (patients correctly classified as pN0). PPV and NPV were used to assess the reliability of positive and negative classifications, respectively.

All the statistical analyses were performed via R software version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A two-sided significance level was set at 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 21,733 patients who underwent surgical resection for HCC were identified and analyzed (Table 1). Of these, 15,496 (71%) were male, and 6,237 (29%) were female. The median age was 65 years (IQR, 58–72). The racial distribution was predominantly white (61%), followed by Asian, black, and Hispanic populations. The median tumor size was 50 mm (IQR, 31–82 mm). In terms of cT stage, 11,000 patients (61%) were classified as T1, 4,018 (22%) as T2, 2,487 (14%) as T3, and 485 (2.7%) as T4. Pathologic T stage distribution was as follows: T1 in 9,521 patients (51%), T2 in 5,522 (30%), T3 in 2,631 (14%), and T4 in 838 (4.5%). Overall, there was a tendency for a greater pT stage distribution than cT stage distribution. For nodal involvement, cN1 was identified in 268 patients (1.4%) out of 19,186, whereas pN1 was found in 252 patients (3.3%) out of 7,612 who underwent LN sampling. The discrepancy in percentages, despite similar patient numbers, is attributed to the lack of preoperative lymph node biopsy or intraoperative LND in most cases. Histologic grading revealed that moderately differentiated tumors were the most common, found in 8,509 patients (53%), followed by well-differentiated tumors in 4,019 patients (25%) and poorly differentiated tumors in 3,312 patients (21%). More patients received treatment at academic institutions (12,643, 58%). The median MELD score was 8 (IQR, 7–13). AFP was positive in 6,728 patients (59%). The histological subtypes included rare subtypes, including the fibrolamellar type in 272 patients (1.3%), the scirrhous type in 51 (0.2%), the spindle cell variant in 46 (0.2%), the clear cell type in 419 (1.9%), and HCC-CCA in 229 (1.1%). The pN1 rates according to histological subtype were as follows: HCC, not otherwise specified (NOS), 1.2%; fibrolamellar type, 15.0%; scirrhous type, 4.5%; spindle cell variant, 5.0%; clear cell type, 1.4%; pleomorphic type, 0%; and HCC-CCA, 7.1%.

Risk factors for LNM

We compared the clinically determined cN stage with the postoperative pN stage. The sensitivity of cN1 for the detection of pN1 was 0.462, the specificity was 0.992, the PPV was 0.619, and the NPV was 0.984. This finding indicates that while the sensitivity was low and the specificity was high, the PPV was low, and the NPV was high (Table 3).

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with cN1. In the overall cohort, older age, male sex, and residence in the western region were associated with a lower likelihood of LNM. Conversely, younger age, female sex, white race compared with Hispanic ethnicity, fibrolamellar histology, HCC-CCA, higher cT stage, and poorer histologic differentiation were associated with a greater likelihood of cN1 (Table 2).

When only the subset of patients who underwent LNE was analyzed, similar factors were found to be associated with pN1. Specifically, younger age, female sex, fibrolamellar histology, HCC-CCA, spindle cell variant, pleomorphic type, higher cT stage, and poorer histologic differentiation were significant predictors of pN1. In the logistic regression analysis for cN status, cases with missing cN data were treated as missing values. Similarly, in the logistic regression analysis for pN status, cases with missing pN data were treated as missing values. (Table 2).

Discussion

In this large cohort study, we found that relying solely on the preoperative cN stage was insufficient for accurately predicting the postoperative pN stage. In particular, the preoperative cN1 stage demonstrated low sensitivity and PPV, which poses challenges in reliably identifying the pN1 status. In the treatment of HCC, the inability to accurately predict pN1 suggests that the current staging system may not be entirely precise. Therefore, careful consideration of this factor in clinical decision-making is essential.

The discrepancy between cN1 and pN1 has also been reported in previous studies. According to a report by Mo et al., when abdominal CT was used to distinguish LNM based on a 10 mm cutoff, the sensitivity was higher at 75.9%, but the specificity was lower at 53.5% [16]. However, this study involved a small sample size, and the criterion for determining cN1 was limited to a 10 mm tumor size. In contrast, our study, which was a large-scale cohort analysis, allowed for a more in-depth examination of the mismatch between cN1 and pN1. Another cohort study using the NCDB included 1,442 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy with LND. Patients who underwent LND had higher clinical T and N stages, with cN1 status predicting pN1 status. Despite the high NPV of 97.9% for cN1, its PPV remained relatively low at 56.3%. However, owing to its high NPV, the study suggested considering LND only for patients with cN1 status [4]. However, it is important to also consider the potential for missed pN1 cases in clinical surveillance.

Our study identified several risk factors for cN1 and pN1. The factors associated with cN1 included age, female sex, white ethnicity, fibrolamellar type, spindle cell variant, clear cell type, HCC-CCA, tumor size, cT stage, region, and grade. The factors associated with pN1 included age, female sex, fibrolamellar type, spindle cell variant, pleomorphic type, HCC-CCA, cT stage, region, and grade. Common factors between cN1 and pN1 included age, female sex, fibrolamellar type, spindle cell variant, HCC-CCA, cT stage, region, and grade. Notably, the utilization of a nationwide multicenter cohort enabled us to explore the associations between LNM and rare histological subtypes, such as the fibrolamellar type and HCC-CCA. These findings underscore the complexity of predicting pN1 status in HCC patients and emphasize the need for comprehensive risk assessment beyond the preoperative cN stage. Further research into the clinical risk factors associated with cN1 and pN1 is crucial to improve patient stratification and guide optimal treatment strategies.

Previous studies have extensively investigated risk factors associated with LNM in HCC. For example, a study utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database examined prognostic factors in HCC patients with LNM. Variables such as grade, T stage, liver surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy (RTx), AFP level, fibrosis score, tumor size, and M stage were assessed. This study revealed that appropriate clinical management strategies could be developed for HCC patients with LNM [17]. Another study involving 2,034 HCC patients reported that preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels exceeding 10 ng/mL were associated with a higher incidence of LNM. Larger tumor size, vascular invasion, higher histologic grade, and lack of encapsulation are also correlated with LNM [8]. Clinical data from 268 HCC patients were used to develop a nomogram for predicting LNM. Furthermore, studies using serologic biomarkers, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (N/L ratio), platelet count, prothrombin time, and total protein, have demonstrated good performance in predicting LNM [13, 14].

Additionally, experimental research in HCC has identified several biomarkers for LNM, such as the nuclear accumulation of CXCR4, the overexpression of VEGF-C and CK19, and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α). These biomarkers, along with gene expression profiling, have provided new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying LNM. Moreover, miRNA-based models have been shown to be reliable for the early prediction of LNM in HCC patients [18–21].

Despite its common occurrence, the clinical significance of LNM in HCC treatment is often underestimated. LNM significantly impacts survival outcomes, as demonstrated by an autopsy study involving 660 HCC patients, which revealed a substantial LNM incidence of 25.5%. Larger tumors (> 10 cm) were associated with a 40% LNM incidence, and poorly differentiated tumors with sinusoidal growth patterns presented higher LNM rates [6]. In addition, a study examining 342 HCC patients with extrahepatic metastases revealed that LNM was the second most prevalent type of metastasis following lung metastasis [22, 23].

In this study, we excluded patients with distant metastasis which exerts a dominant influence on survival outcomes, regardless of LNM. Including M1 cases could introduce significant confounding bias when assessing the independent prognostic impact of LNM. Similarly, patients who underwent liver transplantation were excluded due to their distinct clinical characteristics compared to those undergoing hepatic resection. Liver transplantation is typically reserved for patients with more advanced hepatic dysfunction and different baseline prognostic factors, and it is associated with higher morbidity and mortality than hepatic resection. Including these cases could therefore increase selection bias and confound the interpretation of survival outcomes. However, the exclusion of M1 and liver transplantation cases may limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader HCC population.

Selective LNE in HCC patients has been subjected to scrutiny, with postoperative confirmation of LNM in 18 out of 2189 patients (0.8%). Importantly, no mortalities or occurrences of liver failure were reported. Patients with solitary LNMs presented a more favorable prognosis than did those with multiple LNMs, with a median survival of 29 months and one-, three-, and five-year overall survival rates of 85%, 42%, and 21%, respectively [24]. A nationwide survey conducted in Japan investigated 14,872 HCC patients who underwent surgical resection, employing the Japanese staging system. Notably, LNM was associated with a better one-stage prognosis than distant metastasis [3]. This systematic review included 603 HCC patients and 434 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) patients, revealing a 51.6% prevalence of LND and a 15.2% incidence of LNM in HCC patients and a 78.5% LND rate with a 45.2% incidence of LNM in ICC patients. Routine LND is advocated for both HCC and ICC [25]. In patients with HCC with LNM, aggressive locoregional treatment alongside LND has yielded relatively favorable outcomes. Regional lymphadenectomy is considerably safe and has a low intraoperative complication rate [12, 26]. Among the 15 patients, four experienced lymph node recurrence, and 13 experienced intrahepatic recurrence. The median survival after LND was 25.2 months [27]. These findings highlight the importance of proactive therapeutic strategies in managing HCC patients with LNM and underscore the potential benefits of interventions such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), RTx, and selective LND in improving patient outcomes. However, it is important to recognize that HCC with LNM is indicative of more advanced disease. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system, patients with LNM are classified as having advanced HCC, which typically requires systemic treatment. Systemic therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, play crucial roles in the management of advanced-stage HCC, aiming to improve survival and control disease progression. Thus, the presence of LNM should prompt consideration of not only locoregional interventions but also systemic treatment strategies in the comprehensive management of advanced HCC [28].

Conversely, a body of literature suggests that LND may not be warranted in cases of HCC. An analysis leveraging SEER data concluded that while LNM serves as a prognostic factor in HCC, routine LND is deemed superfluous. Among 8,829 HCC patients, 1,346 underwent LND, with LNM detected in 56 individuals (4.2%). Among the 2,497 lymph nodes examined, 93 (3.7%) tested positive for LNM. Factors such as race, tumor size, clinical T stage, extrahepatic bile duct invasion, and tumor grade were identified as risk factors for LNM [2]. Another study focusing on LND for HCC patients with LNM performed LND in 968 operable patients reported lymph node enlargement. LNM was confirmed in 41 individuals (5.1%). Among the 49 patients with confirmed LNM, those who underwent complete LND had one-, three-, and five-year survival rates of 68.0%, 31.0%, and 31.0%, respectively. However, there was no significant difference in survival curves between those who did and did not undergo LND (p = 0.944) [26]. These discrepancies may arise from differences in patient selection, extent of LND, follow-up duration, and analytical methods. Notably, prior studies focused exclusively on patients undergoing LND, which may introduce selection bias. In contrast, our study analyzed a broader patient population, reflecting real-world practice.

Certain histological classifications, such as the fibrolamellar type or HCC-CCA, are associated with LNM, and LND is often more actively recommended [5, 29–31]. In a comparison of combined HCC-CCA, HCC, and ICC, a greater frequency of LNM was observed in combined tumors, which presented a poorer prognosis than did HCC. However, ICC has the worst prognosis, positioning combined tumors as having an intermediate clinical profile between those of ICC and HCC [31]. Furthermore, when posttreatment outcomes of ICC and HCC patients were assessed, academic cancer centers demonstrated superior survival rates compared with community cancer centers [32]. This study suggested that previously unknown spindle cell variants and pleomorphic types may be related to LNM.

Overall, recent studies emphasize the importance of considering LNM in HCC treatment strategies and underscore the potential benefits of interventions such as TACE, RTx, and selective LND. Future research should continue to investigate the clinical and molecular factors associated with LNM in HCC patients to optimize treatment approaches and improve patient outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that tumor characteristics such as size, grade, and clinical stage, as well as patient demographics, are associated with LNM in patients with resectable HCC. Of particular importance are histologic types, such as the fibrolamellar type and HCC-CCA, which predict a higher risk of LNM. It is crucial to consider the possibility that cN1 may not always correlate with pN1 in treatment planning. When factors related to LNM are present, the likelihood of LNM should be carefully considered in clinical management. The development of reliable prognostic models and nomograms incorporating these factors could aid in treatment decision-making and improve patient outcomes. Additionally, exploring novel biomarkers and therapeutic strategies targeting LNM in HCC remains an area of active research, with the goal of enhancing treatment efficacy and overall survival rates for patients with this disease.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- cN

Clinical nodal stage

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCC-CCA

Hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LNE

Lymph node excision

- LNM

Lymph node metastasis

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NCDB

National Cancer Database

- NOS

Not otherwise specified

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- pN

Pathological nodal stage

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- RTx

Radiation therapy

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- TACE

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

Author contributions

HL, KK, NN, and JY analyzed and interpreted NCDB regarding the clinical and pathologic N stage after LNE for HCC. KJ and ML performed the statistical analysis. HL is a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This analysis of a publicly available deidentified dataset was exempt from the institutional review board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The data used in this study did not contain any personally identifiable information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schlitt HJ, Neipp M, Weimann A, Oldhafer KJ, Schmoll E, Boeker K, Nashan B, Kubicka S, Maschek H, Tusch G, et al. Recurrence patterns of hepatocellular and fibrolamellar carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Lu Y, Shi X, Han G, Zhao J, Gao Y, Wang X. Development and validation of a novel model to predict regional lymph node metastasis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa K, Makuuchi M, Kokudo N, Izumi N, Ichida T, Kudo M, Ku Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Matsui O, Matsuyama Y. Impact of histologically confirmed lymph node metastases on patient survival after surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a Japanese nationwide survey. Ann Surg. 2014;259:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp Bohan PM, O’Shea AE, Lee AJ, Chick RC, Newhook TE, Tran Cao HS, Allen CJ, Nelson DW, Clifton GT, Vauthey JN, et al. Lymph node sampling in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: National practice patterns and predictors of positive lymph nodes. Surg Oncol. 2021;36:138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishii T, Ito T, Sumiyoshi S, Ogiso S, Fukumitsu K, Seo S, Taura K, Uemoto S. Clinicopathological features and recurrence patterns of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe J, Nakashima O, Kojiro M. Clinicopathologic study on lymph node metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 660 consecutive autopsy cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1994;24:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahdaleh FS, Naffouje SA, Sherman SK, Kamarajah SK, Salti GI. Tissue diagnosis is associated with worse survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: A National Cancer database analysis. Am Surg. 2022;88:1234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CW, Chan KM, Lee CF, Yu MC, Lee WC, Wu TJ, Chen MF. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with lymph node metastasis: clinicopathological analysis and survival outcome. Asian J Surg. 2011;34:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang J, Choi J, Choi WM, Kim KM, Lee HC, Shim JH. Response to Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab specific for lung and lymph node metastases affects survival of patients with HCC. Liver Int. 2024;44:907–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun YS, Pawlik TM, Vauthey JN. 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer staging manual: pancreas and hepatobiliary cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:845–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia F, Wu L, Lau WY, Li G, Huan H, Qian C, Ma K, Bie P. Positive lymph node metastasis has a marked impact on the long-term survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiaohong S, Huikai L, Feng W, Ti Z, Yunlong C, Qiang L. Clinical significance of lymph node metastasis in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2010;34:1028–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan Y, Zhou Q, Zhang M, Liu H, Lin J, Liu Q, Shi B, Wen K, Chen R, Wang J, et al. Integrated nomograms for preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion and lymph node metastasis risk in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang XP, Gao YZ, Jiang YB, Wang K, Chen ZH, Guo WX, Shi J, Zhang YJ, Chen MS, Lau WY, Cheng SQ. A serological scoring system to predict lymph node metastasis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawaguchi Y, Chiang YJ, Velasco JD, Tzeng CD, Vauthey JN. Long-term outcomes in patients undergoing resection, ablation, and trans-arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma in the united states: a National cancer database analysis. Glob Health Med. 2019;1:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mo H, Huang R, Wei X, Huang L, Huang J, Chen J, Qin M, Lu W, Yu X, Liu M, Ding K. Diagnosis of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using Dual-Energy computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2023;47:355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K, Tao C, Wu F, Wu J, Rong W. A practical nomogram from the SEER database to predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with lymph node metastasis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:3847–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, Sun HC, Wu WZ, Tan YS. [Nuclear accumulation of CXCR4 and overexpressions of VEGF-C and CK19 are associated with a higher risk of lymph node metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2010;32:344–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Fan J, Tang ZY, Zeng HY, Gao DM. Gene expression profiling of fixed tissues identified hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, VEGF, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 as biomarkers of lymph node metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Fan J, Tang ZY, Zhao XM. A microRNA-based prediction model for lymph node metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3587–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma J, Zhang L, Bian HR, Lu ZG, Zhu L, Yang P, Zeng ZC, Xiang ZL. A noninvasive prediction nomogram for lymph node metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma based on serum long noncoding RNAs. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1710670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchino K, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Kanda M, Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, Goto T, Omata M, Yoshida H, Koike K. Hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: clinical features and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2011;117:4475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uka K, Aikata H, Takaki S, Shirakawa H, Jeong SC, Yamashina K, Hiramatsu A, Kodama H, Takahashi S, Chayama K. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi S, Takahashi S, Kato Y, Gotohda N, Nakagohri T, Konishi M, Kinoshita T. Surgical treatment of lymph node metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amini N, Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Maithel SK, Kim Y, Pawlik TM. Management of lymph nodes during resection of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:2136–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun HC, Zhuang PY, Qin LX, Ye QH, Wang L, Ren N, Zhang JB, Qian YB, Lu L, Fan J, Tang ZY. Incidence and prognostic values of lymph node metastasis in operable hepatocellular carcinoma and evaluation of routine complete lymphadenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awazu M, Fukumoto T, Takebe A, Ajiki T, Matsumoto I, Kido M, Tanaka M, Kuramitsu K, Ku Y. Lymphadenectomy combined with locoregional treatment for multiple advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with lymph node metastases. Kobe J Med Sci. 2013;59:E17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, Beal E, Finn RS, Gade TP, Goff L, Gupta S, Guy J, Hoang HT, et al. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1830–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz SP, Holtestaul T, Marenco CW, Bader JO, Horton JD, Nelson DW. Prognostic role of lymph node sampling in adolescent and young adults with fibrolamellar carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2022;276:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita S, Vauthey JN, Kaseb AO, Aloia TA, Conrad C, Hassan MM, Passot G, Raghav KP, Shama MA, Chun YS. Prognosis of fibrolamellar carcinoma compared to Non-cirrhotic conventional hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Yu X, Xu J, Li J, Zhou Y. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of clinicopathological characteristics after surgery. Med (Baltim). 2019;98:e17102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coon C, Berger N, Eastwood D, Tsai S, Christians K, Mogal H, Clarke C, Gamblin TC. Primary liver cancer: an NCDB analysis of overall survival and margins after hepatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.