Abstract

To evaluate genetic variability among Entamoeba histolytica strains, we sequenced 9,077 bp from each of 14 isolates. The polymorphism rates from coding and noncoding regions were significantly different (0.07% and 0.37%, respectively), indicating that these regions are subject to different selection pressures. Additionally, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) potentially associated with specific clinical outcomes were identified.

A minority (∼10%) of individuals infected with Entamoeba histolytica develop clinical symptoms (5). Whether this is due to variations in parasite genotypes is unknown. Based almost exclusively on analysis of highly repetitive loci, significant genetic diversity among E. histolytica isolates has been reported (1, 7, 8, 20-22). Since highly repetitive regions are prone to incorporating polymorphisms due to DNA slippage, analysis of these loci may overestimate population diversity in a species (15). Analyses of nonrepetitive loci have revealed very limited polymorphisms (3, 6). There is no definitive correlation between genotypes of E. histolytica strains and their clinical manifestations; however, three studies preliminarily indicated that genotypic patterns may be predictive of a clinical outcome (1, 16, 18). To get an improved perspective of genetic variability in nonrepetitive genomic regions, we sequenced 9,077 bp (6,621 bp coding and 2,456 bp noncoding) from each of 14 E. histolytica isolates.

Genetic diversity among E. histolytica isolates.

Four E. histolytica laboratory strains and 10 clinical isolates were studied (Table 1). Laboratory and clinical isolates were cultivated under axenic and xenic conditions, respectively (9, 16). Each E. histolytica isolate was characterized by PCR amplification and sequencing of 13 genetic loci (4) (Table 2). PCRs contained 0.05 μg (phenol-chloroform) to 0.5 μg (GenomiPhi DNA) template DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 0.5 μl of Taq DNA polymerase and were cycled as follows: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; 72°C for 10 min; and a 4°C soak. PCR products were sequenced in their entirety, and sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW (www2.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw). For single-copy genes,sequences from GenBank and the The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) E. histolytica (strain HM-1:IMSS) database (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/eha1/) were the reference sequences (Table 2). For lectin and actin, which are each encoded by multicopy genes, a master template sequence was constructed (see Table 2), and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified in the genome sequence were considered inherent to the gene and not further noted.

TABLE 1.

A summary of the Entamoeba histolytica isolates analyzeda

| Isolate | Country of origin | Date of isolation (mo/yr) | Source | Clinical diagnosis | Stool microscopy | DNA origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM-1:1MSSb (r) | Mexico | 1967 | M | Colitis | NA | Axenicd |

| 200:NIHb | India | 1949 | M | Colitis | NA | Axenicd |

| HK9b | Korea | NA | M | Colitis | NA | Axenicd |

| Rahmanb | England | 1972 | M | Asymptomatic | NA | Axenicd |

| DS2-3497c | Bangladesh | 09/2000 | F | Colitis | Negative | Xenice |

| DS1-1036c | Bangladesh | 10/2000 | M | Colitis | Positive | Xenice |

| DS17-27c | Bangladesh | 06/2001 | M | Colitis | Positive | Xenice |

| DS6-64c | Bangladesh | 04/2001 | M | Colitis | Negative | Xenice |

| DS3-15c | Bangladesh | 05/2001 | F | Colitis | Negative | Xenice |

| MS6-21c | Bangladesh | 11/1999 | M | Asymptomatic | NA | Xenice |

| MS53-3046c | Bangladesh | 10/2003 | F | Asymptomatic | NA | Xenice |

| MS27-291c | Bangladesh | 06/2001 | F | Asymptomatic | NA | Xenice |

| MS30-1047c | Bangladesh | 07/2001 | M | Asymptomatic | NA | Xenice |

| MS15-3394c | Bangladesh | 08/2000 | F | Asymptomatic | NA | Xenice |

(r), reference strain; NA, not available; M, male; F, female. ATCC accession numbers: HM-1:IMSS, 30459; 200:NIH, 30458; HK9, 30015; Rahman, 30886.

Confirmed by PCR analysis of the rRNA episome, strain-specific gene, and PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism of the serine-rich E. histolytica protein (4).

Positive for an E. histolytica-specific fragment of the rRNA gene (4).

Genomic DNA amplified using GenomiPhi DNA amplification (Amersham Biosciences) prior to PCR analysis.

TABLE 2.

The genes, primer sequences, and size of the PCR product utilized for the study are listeda

| Gene, genetic material, or protein | Primer sequences | PCR product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. histolytica-specific rRNA | 5′-GGCCAATTCATTCAATGAATTGAG-3′ | 850 | 4 |

| 5′-CTCAGATCTAGAAACAATGCTTCT-3′ | |||

| ssu rRNA | S: TGA GTTAGGATGCCACGACA | 1560 | GenBank accession number X56991 |

| AS: GTA CAAAGGGCAGGGACGTA | |||

| Actin | S: GGGAGACGAAGAAGTTCAAGC | 1042 | GenBank accession numbers M16339, M16396, M16340 and M16341 and TIGR genome database loci 35.m00215, 74.m00188, and 597.m00020 |

| AS: GGCAAGAATTGATCCTCCAA | |||

| γ-Tubulin | S: TGTTGGACAATGTGGAAATCA | 1000 | GenBank accession number U20322 |

| AS: AGCCAATAACATCCCACTCA | |||

| cpn60 | S: ATGGGACAACAACAGCAACA | 1124 | GenBank accession number AF029366 |

| AS: TCCTCCATCAATTCCTGCAT | |||

| Lectin (hg13) | S: GACATATGCAACAAAAACTGAAGC | 900 | GenBank accession number L14815 and TIGR genome database loci 29.m00206 and 290.m00068 |

| AS: ACACTTGGTTTTCACTTTACGT | |||

| Amebapore C | S: AAGGTAAATTGAATCAAAACACAAA | 928 | TIGR scaffold number 00018 |

| AS: TCGACCGTTTGTTTACTTCTCA | |||

| rabE | S: GGGGAAGGAAAAGTTGGAAA | 632 | GenBank accession number AB054581 |

| AS: TCAGATTTTGCTTGACGAGTG | |||

| Cysteine proteinase 5 | S: TTTCAATACTTGGGTTGCAAAT | 885 | GenBank accession number X91644 |

| AS: GCAGCTCCTGAAGCAATACC | |||

| Intron Cta | S: CTGCATTATCTCAATTTGTTCC | 500 (Intron size, 59) | 19a |

| AS: GGATCTTCATTAATTCTAATTG | |||

| Intron cdc2c | S: GCATGGGACACAGTCTG | 279 (Intron size, 61) | 19a |

| AS: GGCAAAAAGCAAGTCCTTG | |||

| Intron 64.m00165 | S: ATTTATTGGCTTGTGCGTGA | 700 (Intron size, 400) | TIGR locus number 64.m00165 |

| AS: TGGTGATGAACATCCTCAAAA | |||

| Intron 128.m00017b | F: GCTTTTGTCTCTTCACAAATACTTCA | 835 (Intron size, 700) | TIGR locus number 128.m00017 |

| R: TTGTTCTGGTGTTAATCCATCG | |||

| Intergenic region between 2.m00567 and 2.m00568 | S: AAAAGCCATTGAAAATGGATG | 668 | TIGR locus numbers 2.m00567 and 2.m00568 |

| AS: TCCATCAACATCCAATACAATTG | |||

| Locus 1-2 | S: CTGGTTAGTATCTTCGCCTGT | 396-500 | 7 |

| AS: CTTACACCCCCATTAACAAT | |||

| Locus 5-6 | S: CTAAAGCCCCCTTCTTCTATAATT | 396-550 | 7 |

| AS: CTCAGTCGGTAGAGCATGGT | |||

| Chitinase | S: GGAACACCAGGTAAATGTATA | 250-600 | 7 |

| AS: TCTGTATTGTGCCCAATT |

S, sense; AS, antisense; F, forward; R, reverse.

Intron confirmed by Northern blot analysis (Ryan C. MacFarlane, personal communication).

We analyzed coding regions from housekeeping genes (ssu rRNA, cpn60, and genes encoding actin and γ-tubulin) and virulence genes (lectin [hgl3], the gene encoding amebapore C, rabE, and the gene encoding cysteine proteinase 5), since they may be subject to variable selection pressures. Two genes (encoding actin and lectin) are in multiple copies in the genome; the rest are single-copy genes. For the noncoding loci, introns and intergenic and/or promoter regions were analyzed; introns should have essentially no constraint against divergence, whereas intergenic and/or promoter regions may be under some selection pressures (11). We also amplified three polymorphic loci from each strain which showed significant polymorphisms (Table 3). We sequenced locus 1-2 and locus 5-6 for the laboratory strains, and, despite having identical amplicons, the strains were genetically unique (insertions and deletions of tandem repeat sequences and SNPs) (data not shown). Similar results with repetitive loci have been previously reported with amplicon sizes underestimating sequence diversity (7, 21); therefore, sequence analysis of these regions was not performed for the clinical isolates.

TABLE 3.

Genotypic pattern for each genetic locus and straina

| Gene, genetic material, or protein | bp analyzed | HM1: IMSS | 200: NIH | HK9 | Rahman | DS2- 3497 | DS1- 1036 | DS17- 27 | DS6- 64 | DS3- 15 | MS6- 21 | MS53- 3046 | MS27- 291 | MS30- 1047 | MS15- 3394 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coding regions (SNP location) | |||||||||||||||

| ssu rRNA | 1460 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Actin | 942 | I | I | I | I | I | 165T/C, 531T/C | 165T/C | 165T/C, 531T/C | 165T/C, 531T/C | 165T/C, 531T/C | I | 531T/C | 531T/C | |

| γ-Tubulin | 900 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| cpn60 | 1000 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Lectin (hg3) | 800 | I | I | 894A/G | 1245A/C | I | I | 1245A/C | 1245A/C | 894A/G | 894A/G, 1245A/C | 1245A/C | 1245A/C | 894A/G | |

| Amebapore C | 262 | 237T/C | 237T/C | 237T/C | I | I | I | 237T/C | I | I | 237T/C | I | 237T/C | I | |

| rabE | 472 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Cysteine proteinase 5 | 785 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Noncoding regions (SNP location) | |||||||||||||||

| Intron cta | 59 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Intron cdc2c | 61 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Intron abE | 60 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Intron 64.m00165 | 400 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| Intron 128.m00017 | 700 | I | I | I | I | 369T/G | 664T/C | I | 369T/G, 664T/C | I | 664T/C | I | I | I | |

| Intergenic region between 2.m00567 and 2.m00568 | 588 | 364A/G, 550T/G | 364A/G | 364A/G | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | 236T/G*, 240A/G*, 550T/C*, 561T/G* | 236T/G*, 240A/N*, 550T/C*, 561T/N*, | 236T/G*, 240A/N, 550T/C*, 561T/N* | |

| Amebapore C upstream sequence | 588 | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | 407A/C*, 422A/C* | 407A/C, 422A/C | |

| Polymorphic loci | |||||||||||||||

| Locus 1-2 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 396 | 298 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396, 400 | 400 | 396 | 600 | |

| Locus 5-6 | 550 | 396, 550 | 396, 550 | 480, 550 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | 396 | |

| Chitinase | 344 | 250 | 250 | 344 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 344 | 396 | 344 |

I, identical; N, doublet in electropherogram (for SNP 240, N is A/G; for SNP 560, N is T/G). *, confirmed by PCR and sequencing; sequences are in GenBank (AY956427 to AY956440). For each coding region, the position of the SNP is relative to the coding region (A of the start codon is considered position 1). For the noncoding regions, the positions of the SNPs are relative to the sense primer used for PCR amplification (the first nucleotide in the sense primer is considered position 1).

In the nonrepetitive genetic loci analyzed, 14 SNPs were identified: 5 within coding regions and 9 in noncoding regions (Table 3). The actin and lectin genes (both multicopy genes) showed the maximum polymorphisms, with four of the five SNPs occurring in these two genetic loci. The limited sequence variability in the coding regions we studied concurs with a recent comparative genomic hybridization analysis, where these genes were highly conserved among the strains tested (20). All SNPs in the coding regions were synonymous. This is incongruous with reports for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, where analysis of coding regions from seven housekeeping genes (8,318 bp of sequence) revealed 101 SNPs, of which only 36 were synonymous (2). Similarly, in Plasmodium falciparum, of the 48 SNPs detected in antigenic locus mspI, only 7 were synonymous (17). Whether these differences between our observations and others are due to technical (limited amount of sequence data, types of genes analyzed) or biological (codon bias, differential selection pressure) reasons is not clear at present. We searched the GenBank database for sequences of nonrepetitive coding regions from E. histolytica strains other than HM-1:IMSS. Of the approximately eight sequences identified (X84009, X83685, X79134, X79133, X83685, AY870660, AY460178, X82198), only the latter three have significant matches in the TIGR E. histolytica database, and only one (X82198) had an SNP that was synonymous. Further sequencing may be useful to clarify this issue. It is likely that each point mutation occurred just once in the phylogenetic history of the species. Since SNP markers are evolutionarily stable and unlikely to mutate again to either a novel or ancestral state, they are useful for evolutionary analyses (2).

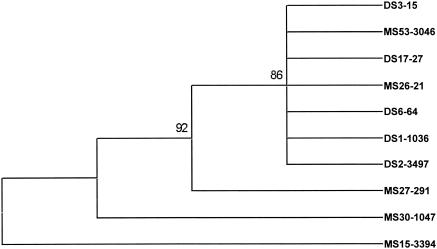

Using data from all genes studied, we identified 14 genotypic patterns among the 14 isolates. However, the types of polymorphisms we identified in nonrepetitive genomic regions were significantly different from those in highly repetitive regions. Sequence divergence in our study was limited to SNPs, in contrast to sequence analysis of repetitive regions, in which differences between isolates are largely due to copy numbers of 12- to 16-bp tandemly repeated regions (7). The underlying structure of the DNA influences replication errors, and DNA slippage can result in changes in the number of repeat regions, leading to a large degree of variability in repetitive loci (15). For phylogenetic analysis, nucleotide sequences for the six genetic loci with SNPs were combined and used to generate a dendrogram, which distinguished three of the asymptomatic isolates from the others (Fig. 1). Two asymptomatic isolates (MS26-21 and MS53-3046) clustered with the samples from diarrheal stools. Whether this indicates that these two isolates have unrecognized virulence potential remains to be investigated. Among the clinical isolates, there were six SNPs associated exclusively with isolates from asymptomatically infected individuals (the 894 SNP in the lectin gene; the 236, 240, and 561 SNPs in the intergenic region between 2.m00567 and 2.m00568; and the 407 and 422 SNPs in the upstream region of amebapore C) (Table 3). Additionally, there was one SNP (369 in the 128.m00017 intron) that in the clinical isolates was identified only in samples from diarrheal stools. However, using a two-sided Fischer exact test using Stata/SE 7.0 (Stata Corporation Texas), only the lectin 894 SNP was statistically significant in its association (P = 0.015).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram created using concatemeric nucleotide sequences for 10 clinical E. histolytica isolates for the six genetic loci with SNPs. The dendrogram was generated using a Mega 2.2 program (dMEGA2; Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Software; Arizona State University) (http://www.megasoftware.net/) using a maximum parsimony matrix algorithm and bootstrap values to estimate confidence intervals.

Significant variability in polymorphisms between coding and noncoding regions.

The occurrences of SNPs between coding and noncoding regions (0.07% and 0.37%, respectively) were statistically significantly different (P = 0.0039) (as calculated above). A number of factors could influence this observation. First, SNPs are more common in microsatellite repeats; however, this was not a factor in our observation, as the SNPs in noncoding regions were not in microsatellite repeats. Second, codon bias restricts the extent of genetic variability that can occur in coding regions, especially in AT-rich organisms such as E. histolytica (12). A functional constraint in the coding regions was seen in our analysis, as all SNPs represented synonymous changes. Of the nine SNPs in the noncoding regions, seven were identified exclusively in clinical isolates, suggesting continued selection and evolutionary pressures. Noncoding regions are often targeted for population-based investigation because they represent rapidly evolving sequences, as they are subject to reduced selective constraints compared to coding regions (10, 11). Our results corroborate previous studies, where E. histolytica isolates differing at the locus encoding chitinase or serine-rich E. histolytica protein were identical at rRNA internally transcribed spacer regions and intergenic sequences between superoxide dismutase and actin 3 genes (6, 13). Similar epidemiological studies of Plasmodium falciparum have revealed paradoxical results in population structures partly due to the reliance of some studies exclusively on highly polymorphic genes (14, 15) versus data from housekeeping genes or introns (19). The overall data indicate that noncoding regions may be better gauges to assess evolutionary trends in E. histolytica.

Long-term tissue culture does not significantly change the nonrepetitive genetic regions.

The E. histolytica isolates studied have been subjected to variable culture conditions from long-term (>30 years) axenic culture to short-term (1 to 3 years) xenic culture (Table 1). The different conditions did not significantly change the genetic composition of nonrepetitive regions. Overall, 4,617 bp and 580 bp of coding and noncoding regions, respectively, did not change among any of the isolates tested (a total of 72,758 bp). Additionally, the presence of SNPs at identical positions (237 in amebapore C and 894 and 1245 in the lectin gene) in both laboratory and clinical samples indicate that E. histolytica isolates have remained phylogenetically conserved during long-term tissue culture (Table 3). Furthermore, axenization did not trigger significant changes in the genes studied.

We propose that studies of noncoding, nonrepetitive regions might be the most informative for future population-based studies to develop an improved evolutionary and phylogenetic framework for E. histolytica.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The sequences described in this work have been submitted to GenBank under the nucleotide sequence accession numbers AY956427 to AY956440.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Stanford University Dean's fellowship for D.B. and grants from the NIAID (AI-053724 and AI-063470) to U.S. R.H. is an International Research Scholar of the HHMI and is also supported by a grant from the NIAID (AI-43596).

We gratefully acknowledge the help of Tomoyoshi Nozaki for critical reading of the manuscript, Sebastian Gagneux for statistical help, and all members of our laboratory, especially Jason A. Hackney for helpful suggestions and discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayeh-Kumi, P. F., I. M. Ali, L. A. Lockhart, C. A. Gilchrist, W. A. Petri, Jr., and R. Haque. 2001. Entamoeba histolytica: genetic diversity of clinical isolates from Bangladesh as demonstrated by polymorphisms in the serine-rich gene. Exp. Parasitol. 99:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, L., T. Brown, M. C. Maiden, and F. Drobniewski. 2004. Silent nucleotide polymorphisms and a phylogeny for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1568-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck, D. L., M. Tanyuksel, A. J. Mackey, R. Haque, N. Trapaidze, W. R. Pearson, B. Loftus, and W. A. Petri. 2002. Entamoeba histolytica: sequence conservation of the Gal/GalNAc lectin from clinical isolates. Exp. Parasitol. 101:157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, C. G., and L. S. Diamond. 1993. Entamoeba histolytica: a method for isolate identification. Exp. Parasitol. 77:450-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gathiram, V., and T. F. Jackson. 1985. Frequency distribution of Entamoeba histolytica zymodemes in a rural South African population. Lancet i:719-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh, S., M. Frisardi, L. Ramirez-Avila, S. Descoteaux, K. Sturm-Ramirez, O. A. Newton-Sanchez, J. I. Santos-Preciado, C. Ganguly, A. Lohia, S. Reed, and J. Samuelson. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of Entamoeba spp.: evidence of a bottleneck (demographic sweep) and transcontinental spread of diploid parasites. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3815-3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haghighi, A., S. Kobayashi, T. Takeuchi, G. Masuda, and T. Nozaki. 2002. Remarkable genetic polymorphism among Entamoeba histolytica isolates from a limited geographic area. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4081-4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haghighi, A., S. Kobayashi, T. Takeuchi, N. Thammapalerd, and T. Nozaki. 2003. Geographic diversity among genotypes of Entamoeba histolytica field isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3748-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haque, R., I. K. Ali, S. Akther, and W. A. Petri, Jr. 1998. Comparison of PCR, isoenzyme analysis, and antigen detection for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:449-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann, T., C. R. Blackston, S. F. Parmley, J. S. Remington, and J. P. Dubey. 2000. Strain typing of Toxoplasma gondii: comparison of antigen-coding and housekeeping genes. J. Parasitol. 86:960-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, W. 1997. Molecular evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 12.Loftus, B., I. Anderson, R. Davies, U. C. Alsmark, J. Samuelson, P. Amedeo, P. Roncaglia, M. Berriman, R. P. Hirt, B. J. Mann, T. Nozaki, B. Suh, M. Pop, M. Duchene, J. Ackers, E. Tannich, M. Leippe, M. Hofer, I. Bruchhaus, U. Willhoeft, A. Bhattacharya, T. Chillingworth, C. Churcher, Z. Hance, B. Harris, D. Harris, K. Jagels, S. Moule, K. Mungall, D. Ormond, R. Squares, S. Whitehead, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, H. Norbertczak, C. Price, Z. Wang, N. Guillen, C. Gilchrist, S. E. Stroup, S. Bhattacharya, A. Lohia, P. G. Foster, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, C. Weber, U. Singh, C. Mukherjee, N. M. El-Sayed, W. A. Petri, Jr., C. G. Clark, T. M. Embley, B. Barrell, C. M. Fraser, and N. Hall. 2005. The genome of the protist parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Nature 433:865-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton-Sanchez, O. A., K. Sturm-Ramirez, J. L. Romero-Zamora, J. I. Santos-Preciado, and J. Samuelson. 1997. High rate of occult infection with Entamoeba histolytica among non-dysenteric Mexican children. Arch. Med. Res. 28:311-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich, S. M., and F. J. Ayala. 2000. Population structure and recent evolution of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6994-7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich, S. M., R. R. Hudson, and F. J. Ayala. 1997. Plasmodium falciparum antigenic diversity: evidence of clonal population structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13040-13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah, P. H., R. C. MacFarlane, D. Bhattacharya, J. C. Matese, J. Demeter, S. E. Stroup, and U. Singh. 2005. Comparative genomic hybridizations of Entamoeba strains reveal unique genetic fingerprints that correlate with virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 4:504-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanabe, K., N. Sakihama, and A. Kaneko. 2004. Stable SNPs in malaria antigen genes in isolated populations. Science 303:493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valle, P. R., M. B. Souza, E. M. Pires, E. F. Silva, and M. A. Gomes. 2000. Arbitrarily primed PCR fingerprinting of RNA and DNA in Entamoeba histolytica. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 42:249-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volkman, S. K., A. E. Barry, E. J. Lyons, K. M. Nielsen, S. M. Thomas, M. Choi, S. S. Thakore, K. P. Day, D. F. Wirth, and D. L. Hartl. 2001. Recent origin of Plasmodium falciparum from a single progenitor. Science 293:482-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Wilihoeft, U., E. Campos-Gongora, S. Touzni, I. Bruchhaus, and E. Tannich. 2001. Introns of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar. Protist 152:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaki, M., and C. G. Clark. 2001. Isolation and characterization of polymorphic DNA from Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:897-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaki, M., S. G. Reddy, T. F. Jackson, J. I. Ravdin, and C. G. Clark. 2003. Genotyping of Entamoeba species in South Africa: diversity, stability, and transmission patterns within families. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1860-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaki, M., J. J. Verweij, and C. G. Clark. 2003. Entamoeba histolytica: direct PCR-based typing of strains using faecal DNA. Exp. Parasitol. 104:77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]