Abstract

Objective

Over the last 35 years, there has been growing evidence suggesting a relationship between tobacco use and breast cancer. The tobacco industry’s role in shaping research, policy, and public opinion about the relationship is unknown. This study’s objective is to determine if the tobacco industry-funded Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) Records and the Tobacco Institute (TI) Records, housed in the Truth Tobacco Industry Document Archive, contain documents related to internal research about breast cancer and strategies to influence the science and public opinion about breast cancer causes.

Methods

We applied the situational scoping method, in which community advocates and university researchers collaborate, to 1) identify external events considered by CTR or TI as a threat or opportunity to business interests; 2) select events for further analysis, and 3) conduct social worlds/arenas mapping of industry responses to selected events.

Results

The CTR and TI Records contained 19,719 documents with the search term “breast cancer” ranging from the 1950s to 1998. We analyzed nine events relevant to the aim of this research. CTR and TI responded to external threats, pointing out methodological problems in studies they perceived as threatening, or characterizing lung cancer as misdiagnosed or metastasized breast cancer. They responded to external opportunities with promoting and funding research focusing on smoking’s “protective effects” over breast cancer, and breast cancer’s genetic, hormonal, and dietary causes.

Conclusion

The CTR and TI Records are a rich source of documents related to tobacco industry efforts to influence breast cancer research, policy, and public opinion away from any etiologic relationship between tobacco use and breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers among women.[1] In the U.S., while the 2005 California Environmental Protect Agency report listed secondhand smoke as a cause of breast cancer in younger women,[2] the 2014 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report suggested that there was insufficient evidence of a causal relationship between either active or passive smoking and breast cancer.[3] Globally, recently-published meta-analyses of the last 35 years of studies showed an overall increase of breast cancer risks associated with smoking or secondhand smoke exposure.[4,5] While the science continues to emerge, it is unclear what role the tobacco industry played in shaping the scientific, regulatory and public discourse about the relationship between smoking and breast cancer. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no prior studies addressing tobacco industry strategies related to breast cancer using previously secret tobacco industry documents.

Tobacco companies have a documented history of influencing scientific research and policies related to the health harms associated with tobacco use. Since the 1950s, the tobacco industry has created doubts and discredited science about the health risks of smoking on health outcomes, such as lung cancer.[6] The tobacco industry’s efforts to discredit the science about secondhand smoke is also well documented, including designing their own studies to counter Hirayama’s influential study of lung cancer among Japanese wives exposed to secondhand smoke,[7] funding research through industry front groups such as the Center for Indoor Air Research to serve their agenda regarding secondhand smoke legislation [8] and building networks of scientists to discredit scientific research about secondhand smoke.[9] The industry has also manipulated media and public relations to counter findings from credible organizations such as International Agency for Research on Cancer,[10] and tried to turn the risk assessment of secondhand smoke exposure into a discussion of a wide range of toxins in order to downplay secondhand smoke hazards in particular.[11]

Two tobacco industry-funded groups, the Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) and the Tobacco Institute (TI) have played important roles for decades in undermining science on the health risks of tobacco, such as cancer or cardiovascular diseases, and questioning the addictiveness of nicotine.[6] [12] The CTR was created in 1954 by major U.S. companies in response to increasing evidence that smoking caused lung cancer, to conduct and support research that downplayed the association as causal.[13] [14] [15] By 1998, CTR provided a total of over US$300 million in research grants and became the world’s leading private funding agency of biomedical research on tobacco and health.[14] The TI was created in 1958 by leading U.S. tobacco companies as a public relations and lobbying vehicle representing industry positions, including tobacco-related health issues.[14] [16] The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement required these two organizations to be dissolved due to their pivotal role in promoting industry-wide efforts to challenge research on tobacco’s health harms.[17] As these two organizations represented the voices of the leading tobacco companies and established a model of collective industry-wide, coordinated public relations strategies for multiple decades,[13,16] the CTR and TI are ideal candidates to study the tobacco industry’s coordinated responses to and attempts to influence the science about breast cancer etiology.

Our research question is: what do documents in the CTR and TI Records collections in the Truth Tobacco Industry Document Archive reveal about tobacco companies’ internal research on breast cancer and strategies to influence scientific and public opinion about tobacco exposure and breast cancer? In this study, we use the newly developed situational scoping method, [18] in which community advocates and university researchers collaborate, to scope the documents related to research questions. We focus on specific empirical situations defined as external events considered by CTR or TI as a threat or opportunity to business interests.

METHODOLOGY

The data used for this manuscript are a subset of a larger scoping investigation of documents in the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Industry Documents Library (IDL), that occurred between August 2021 and July 2022 and included five archives: the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive, the Food Industry Documents Archive, the Chemical Industry Documents Archive, the Drug Industry Documents Archive, and the Fossil Fuel Industry Archive. This work was funded by a grant from the California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP) to “investigate if there are documents in the UCSF online Industry Documents Library related to breast cancer.[19] A preliminary search of the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive in August 2021 using the term “breast cancer” returned 54,283 documents. Here, we report on two subcollections of the Master Settlement Agreement Collection: Council for Tobacco Research Records, (6,403 documents with the search term “breast cancer”) and the Tobacco Institute Records, (13,316 documents with the search term “breast cancer”). Documents contained in the additional Master Settlement Agreement subcollections and other tobacco industry document collections will be reported separately.

The situational scoping method was developed as part of the larger CBCRP project and expands beyond tobacco documents research methods by formally involving a collective of transdisciplinary researchers and community members who collaborate to shape knowledge production based on their experience and opinions about which situations are most essential to inform emancipatory action[18]. The situational scoping method is designed to be a rigorous and transparent method to conduct an overview of a body of IDL documents relevant to a research question/s. This research does not require ethics approval as it does not involve human subjects or animal research, and it uses data that is available in the public domain.

The Situational Scoping Method

We used the situational scoping method to search and analyze CTR/TI documents related to breast cancer, a method developed by author CK for the larger scoping investigation. [18] “Situational” refers to empirical situations that are the object of our study. Our empirical situation of interest is: CTR and TI responses to external events over time related to breast cancer considered to be threats or opportunities to business interests. Examples of external events include emerging scientific research, policy proposals, and news stories related to tobacco and breast cancer. “Scoping” refers to goals of a traditional scoping reviews designed to apply rigorous and transparent methods to conduct an overview or map a body of literature relevant to a research question/s.[20]

The Situational Scoping Method stages are:

Identification of a broad range of external events over time considered by IDL industries as a threat or opportunity to business interests.

Selection of external events for further analysis.

Social worlds/arenas mapping of industry responses to selected external events.

Situational Scoping Method Procedures Used to Scope the CTR and TI Records

Study procedures were organized into four phases and include procedures conducted separately by the research team (university researchers), and collectively by the project team (university researchers, BCAction, facilitator, UCSF IDL archivists) over the course of one year. Detailed study procedures are contained in Table 1. The document search, social worlds mapping, and Community Engagement Studio methods are described in the Appendix.

Table 1:

Situational Scoping Procedures Used to Scope the CTR and TI Records

| Project Phase | Researcher Procedures | Project Team Procedures |

|---|---|---|

| I. High-level scoping of documents (Aug 2021) | 1) With guidance from research team, EH conducted an overview of collection provenance, frequency, and distribution of documents using search term “breast cancer” (e.g., by decade, by product type, and document type) including important time periods, tobacco brands, foods, chemicals, and organizations of interest. 2) Recorded initial impressions on general themes and organizations of interest 3) Shared findings and received input at weekly research team meetings 4) Presented findings at Community Engagement Studio #1 |

Community Engagement Studio #1 5) Gave input on organizations and themes of interest 6) Additional search terms suggested relevant to tobacco and other possible cancer-causing factors in the environment: “breast cancer” AND (“smoking” OR “grant” OR “ETS” OR “secondhand smoke” OR “passive smoking” OR “EPA”) |

| II. Document sorting and review (Sep – Oct 2021) | 7) EH sorted and reviewed excerpts of high-value documents by decade for content related to external events, grouped documents on Padlet, a cloud-based real-time collaborative web platform in which users can upload, organize, and share content to virtual bulletin boards [82] 8) Shared findings and received input at weekly research team meetings 9) Documented search strategies and external events, including emerging science, media coverage, policy events, controversial issues, key institutions and organizations, and CTR/TI responses in a semi-structured memo. |

|

| III. Selection of external events (Nov 2021) | 10) EH presented findings on key external events and an initial assessment of involved organizations at Community Engagement Studio #2 13) Finalized 440 high-value documents for in-depth analysis using all suggested search terms: “breast cancer” AND (“smoking” OR “grant” OR “ETS” OR “secondhand smoke” OR “passive smoking” OR “EPA” OR “estrogen” OR “endocrine disruptor” OR “air pollution” OR chemicals OR “genotoxic”) |

Community Engagement Studio #2 11) Prioritized external events most relevant to project objectives to focus on for in-depth analysis 12) Additional search terms suggested related to cancer-causing factors linking to breast cancer and environmental exposure: “breast cancer” AND “estrogen” OR “endocrine disruptor” OR “air pollution” OR chemicals OR “genotoxic”. ; |

| IV. Social worlds/arenas mapping (Dec – May 2022) | 14) EH initiated analysis of external events and CTR/TI responses through iteratively constructing social worlds/arenas maps with Google Jamboard, a collaborative digital whiteboard [83], using procedures described in Clarke et al. [25] 15) Shared maps and received input at weekly research team meetings 16) Kept structured analytical memos using questions outlined by Clarke et al. [25] to support mapping 17) Presented preliminary maps at Community Engagement Studio #3 19) Revised maps with research team input 20) Completed a final structured analytical memo for each map 21) Presented revised maps used in project report at Community Engagement Studio #4 23) Final map iteration completed during writing of manuscript |

Community Engagement Studio #3 (February) 18) Gave input on items of greatest relevance to project objectives, items that were unclear, and map restructuring ideas Community Engagement Studio #4 (May) 22) Planned workshops to disseminate initial findings to the public |

RESULTS

In this section, we characterize the CTR and TI documents returned with the search term “breast cancer,” report on breast cancer-related external events relevant to CTR and TI business interests, and present two social worlds/arenas map that capture our industry responses to these external events.

Overview of CTR and TI Records

Of the 19,719 documents in the CTR/TI collections returned with the search term “breast cancer”, 28% were scientific publications (e.g., article, report, abstract), 19% were related to research in progress (e.g., grant application, proposal, progress report), 6% were external communication (e.g. press release, pamphlet, presentation), and 6% were internal communication (e.g., budgets, memos, meeting minutes, reports). The remaining 41% of the documents were in 51 different miscellaneous document categories (e.g. graph, table, outline, curriculum vitae etc.).

Document dates ranged from the 1950s to 1998, with most created between 1970 and 1998. Initial themes identified after the first reading of high-value documents included: genetic and hormonal causes of breast cancer, and other possible causes including air pollution, dietary fat, hair dye, alcohol, studies and debates about the effectiveness of early detection and treatment of breast cancer, debates about whether smoking status and second-hand smoke exposure were associated with breast cancer, and industry-funded research. Organizations of interest included: American Cancer Society National Cancer Institute, Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, California Department of Health, and the Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. and California).

Identification and Selection of External Events Related to Breast Cancer Considered by CTR and TI as a Threat or Opportunity to Business Interests

We initially identified 10 external events related to breast cancer that were relevant to the CTR and TI’s business interests (Table 2). Timing of the external events ranged from 1981 to the late 1990s. We classified five events as threats and five as opportunities. With feedback from the project team, we excluded one external event thought to be least likely to reveal data related to project objectives from further analysis – the California Tobacco Tax and Health Protection Act of 1988 (Proposition 99) which began contributing to a breast cancer research fund in 1993. [30,31] We found that the proposition addressed a range of public health issues and tobacco tax revenues were allocated to broader tobacco and health related research. Breast cancer research was not its main focus.

Table 2.

Key External Events Initially Identified by the Project Team as Potential Threats or Opportunities to the Business Interests of the Council for Tobacco Research and the Tobacco Institute

| Event | Year | Threat/Opportunity | About |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early evidence of association between secondhand smoke and breast cancer | 1981 | Threat | Hirayama’s studies of wives of Japanese smokers found a borderline association between secondhand smoke exposure and breast cancer [58] |

| Lung cancer surpassed breast cancer mortality among women in the U.S. | 1987 | Threat | Demonstrated the severity of the increasing smoking rate of women [34] |

| Association between secondhand smoke and breast cancer | 1990s | Threat | Researchers (Wells, Morabia) found increased risk of breast cancer with secondhand smoke exposure [60] [84] |

| EPA designated secondhand smoke as human carcinogen | 1990s | Threat | EPA published a guide to workplace smoking policies and released risk assessment of secondhand smoke in the 1990s [70,71] |

| California Proposition 99 | 1988 | Threat | California legislation aiming at increasing cigarette retail taxes, which involved allocation of the revenues to support research, including breast cancer[31] |

| Progress in hereditary and genetic research about breast cancer | 1980s and 1990s | Opportunity | Findings on genetic causes of breast cancer, discovery of BRCA-1 and BRCA-2, [85] |

| Studies of estrogen and breast cancer | 1980s | Opportunity | Cigarette smoking was found to have estrogen repressive effects that could reduce breast cancer [38] |

| Dietary fat, oral contraception, and abortion as causes or risk factors of breast cancer |

1980s | Opportunity | Emerging studies suggesting alternative causative factors related to breast cancer. [42] [43] [86] |

| Scholarly events on secondhand smoke | 1980s-90s | Opportunity | Example: Montreal Symposium on ETS (1989), organized by pro-industry scientist, reached no conclusion on secondhand smoke and lung cancer, and also breast cancer [87] |

| Negative or “no association” of smoking on breast cancer | 1980s | Opportunity | Scientific research showing no association of breast cancer and smoking [36,37] |

Mapping CTR and TI Responses to External Events Related to Breast Cancer

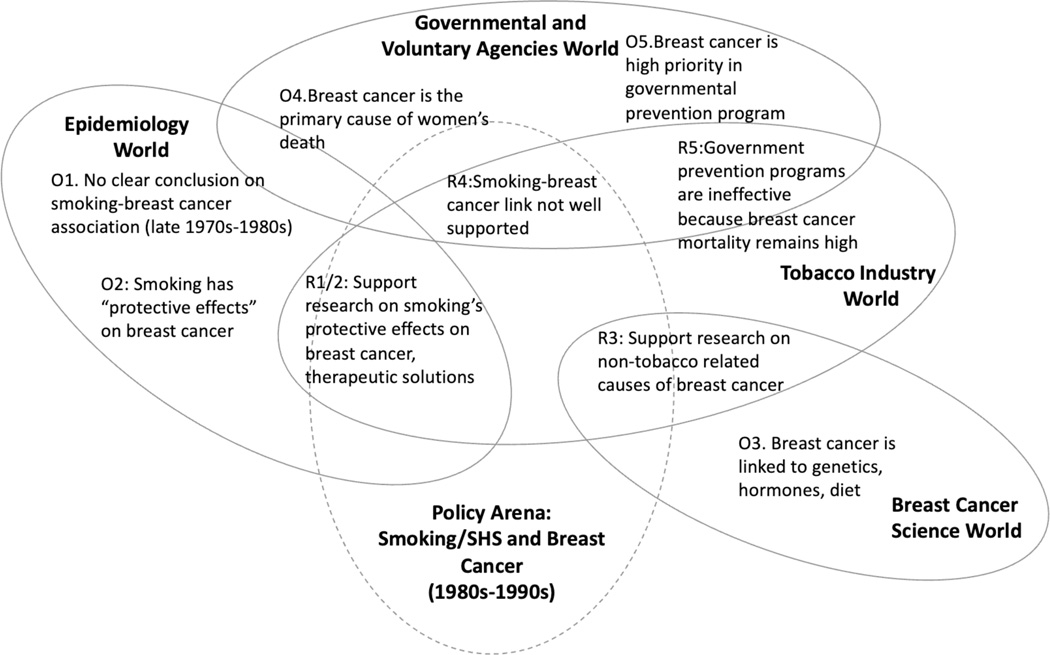

Two final social worlds/arenas maps were created: one focused on CTR and TI responses to external opportunities that could be leveraged to defend industry interests and one focused on CTR and TI responses to external threats that could hinder product marketing or reduce trust in the industry (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Social worlds/arenas map of CTR and TI responses to external opportunities related to breast cancer.

Ovals with solid lines represent social worlds, and ovals with dashed lines represent policy arenas. Bold words represent the names of social worlds and arenas. O21–5 are external opportunities. R1–4 are CTR and TI’s responses to these opportunities.

Figure 2.

Social worlds/arenas map of CTR and TI responses to external threats related to breast cancer. T1–5 are external threats. R1–4 are CTR and TI responses to these threats.

Map 1: CTR and TI Responses to External Opportunities Related to Breast Cancer

The opportunities map (Figure 1) contains four social worlds, five external opportunities, and five tobacco industry responses, centered around a smoking and secondhand smoke arena. The policy arena represents debates about the health effects of smoking/secondhand smoke on breast cancer between the 1980s and 1990s.

Epidemiology World

This social world represents population-level studies about smoking and secondhand smoke. The epidemiology world generated two external opportunities for CTR/TI. The first opportunity (Figure 1: O1) was that most epidemiological studies, reports, and conferences during the 1970s-80s had found no clear conclusion on the association between smoking and breast cancer. For example, TI’s public relations consultant Leonard Zahn reported a study by a CDC researcher showing that smoking did not affect the risk of breast cancer among women, during the International Conference on Smoking and Reproductive Health in 1985. [32] This was an opportunity for the tobacco industry because while smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke among women became an increasingly concerning issue,[33–35] the tobacco industry would not be blamed for breast cancer, the leading cancer among women.[36,37] The second opportunity for CTR/TI (Figure 1: O2) was the emergence of evidence that women who smoked had a lower risk of breast cancer compared to those who did not. The New England Journal of Medicine published a study in 1982 that linked the lower risk of breast cancer among women who smoked to smoking’s estrogen-suppressing effects, which “shed a light on why ‗smoking is associated with early menopause and with a reduction in the risk of breast cancer.”‘ [38,39]

Breast Cancer Science World

This social world represents scientific research about breast cancer, which generated a third situational opportunity for the tobacco industry (Figure 1: O3). Several studies emerged during the later 1970s and 1980s suggesting that breast cancer was linked to non-tobacco related causes such as genetics, hormonal, and dietary factors. Related to genetics, Henry Lynch, a renowned physician researcher (recipient of CTR funding for years), published research in the late 1970s showing evidence of genetic causes of breast cancer.[40] Additionally, the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II, released in 1981, concluded that breast cancer had a strong familial component.[40,41] The TI also collected studies since the 1960s showing increased risks associated with oral contraceptives including breast cancer and was planning publicity on this topic.[42] Related to diet, National Cancer Institute’s cancer prevention trials reported a link between dietary fat and breast cancer, recorded by the PR consultant Leonard Zahn on the 1987 National Conference on Cancer Prevention and Detection.[43]

Governmental and Voluntary Agencies World

This social world represents government regulations and official reports about breast cancer and lung cancer, and research and reports by professional organizations related to these topics. This social world generated a fourth and fifth opportunity for the tobacco industry. The fourth was that the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II, which concluded that breast cancer was the primary cause of death in women, was reported in the 1987 National Conference on Cancer Prevention and Detection (Figure 1: O4).[43] As breast cancer was generally not considered as smoking-related, the tobacco industry would then be less accountable for it, and made good use of this to defend themselves in the rising concern of women smoking. The fifth opportunity was that breast cancer has been a high priority with government-initiated prevention programs (such as early detection), yet breast cancer mortality still remained high, suggesting government programs had been ineffective (Figure 1: O5), making it an opportunity for industry representatives to attack governmental initiatives related to smoking. [44–46]

Tobacco Industry World

This social world represents the responses of CTR/TI to the opportunities. In response to the epidemiology world, the TI leveraged the lack of evidence linking smoking to breast cancer and the potential protective effects of smoking for breast cancer related to estrogen suppression (Figure 1: R1/2). A CTR review of all “protective effects” of smoking cited the 1982 NEJM study [38] and others showing smoking’s estrogen-suppressing function. [47,48] CTR prioritized research funding to bolster the estrogen-suppressing thesis in the 1980s and 1990s, even though this evidence was not well supported, and even the TI newsletters cited research found “little evidence to support a protective effect of smoking”.[49,50] CTR funded at least two multi-year research projects related to the protective effects, including a nearly decade-long project on aromatase inhibitors derived from tobacco, as an estrogen suppressor to treat breast cancer, by a team led by Yoshio Osawa at the Medical Foundation of Buffalo. The other project was Leon Bradlow and colleagues’ research on the mechanism of smoking’s effects on estrogen-dependent cancer, including breast cancer (Table 3). Other CTR-funded research projects explored estrogen-suppressing mechanisms as a means to provide therapeutic solutions to breast cancer (Table 3). Of all the funded research projects in this area, we identified three publications that acknowledged CTR funding. [51–53]

Table 3.

Major Research Funded by the Council for Tobacco Control about Breast Cancer (1980s-1990s)

| Year | Lead Researcher (PI) | Affiliation | Title | Area | Breast Cancer-Related |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 - | Eleanor Macdonald | University of Texas M.D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute at Houston | Regional Patterns of Cancer of Each Site in Five Large Regions in Texas [88] |

Epidemiology | Breast cancer as an outcome, geographical and racial variations |

| 1973 | Henry Lynch, | Creighton | Hereditary Factors, | Hereditary | Breast cancer |

| Hoda Guirgis | University | Cigarette Smoking, and Cancer Incidence in 3,261 Families [89] | (Genetic) | was found to be hereditary | |

| 1979–1994 | Henry Lynch | Creighton University | Genetic and Biomarker Studies of Smoking-Associated Cancers * [90] | Genetic | Breast cancer was hereditary within family [91,92] [93–95] |

| 1982 – 1983 | Robert Sklarew | NYU School of Medicine | Cytokinetics of Heteroploid Subpopulations by Imaging *** [96] | Genetic, cellular | Using human breast cell populations |

| 1983–1991 | Yoshio Osawa | Medical Foundation of Buffalo Inc. | Aromatase Inhibitors in Cigarette Smoke and Tobacco* | Hormonal | Tobacco-derived aromatase inhibitors and potentials in reducing breast cancer risk [97,98] |

| 1985 | Joseph Fontana | University of West Virginia | Glycosyltransferases and Glycoprotein/Proteoglycan Synthesis in Differentiation Induced Phenotypic Reversal of Malignancy by Retinoic Acid and Cyclic Nucleotides and Other Agents **[52] |

Hormonal | Tamoxifen as a potential therapeutic solution to breast cancer [52] |

| 1987-1997 | David Sirbasku | University of Texas Health Sciences | Estrogen Responsive and Autonomous Human Breast Cancer Growth* [99] |

Hormonal/Ge netic [99,100] | Estrogen as a breast cancer growth factor |

| 1986-1988 | H Leon Bradlow | Rockfeller University | Estrogen Metabolism in Relation to Cancer Risk ***[101] | Hormonal [101,102] | Breast cancer as a study subject |

| 1992-1994 | Thomas Fanning | Armed Forces Institute of Pathology | Function of Line-1 Retrotransposons in Human Breast Cancer * [103] | Cell Pathology, genetic | Pathology of breast cancer |

| 1993 | Thomas Finlay | NYU Medical Center | Proteases, Protease Inhibitors and Growth Factors in Breast Cancer [104] [105] | Hormonal | Breast cancer tumor growth and hormone |

| 1994 | Victoria Stevens | Emory University | Mechanism of Release of GPI-Anchored Proteins from Breast Cancer Cells [106] | Cellular | |

| 1994 | Herbert Samuels | NYU Medical Center | Growth Suppression of Breast Tumor Cells by Retinoids [107] | Genetic, therapeutic | Breast cancer gene expression, retinoids |

| 1995 | JoEllen Welsh | W. Alton Jones Cell Sciences Center | Calcium and Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells [108] | Cells | Vitamin D and breast cancer |

| 1990 | Stephen H. Friend | Harvard Medical School | Tumor Suppressor Genes. Tumor Formation and Development [109] |

Genetic | Tumor suppressor genes for breast cancer |

| 1996 | Sarah Parsons | University of Virginia | Interactions between c-Src and HER family members in human breast tumors [110] |

Genetic, molecular | Genetic and molecular aspects of breast cancer |

| 1997 | Jim Z Xiao | Boston Medical Center | Role of Cycln D1 and RB MDM-2 in Breast Cancer [111] | Genetic | Genetic and molecular aspects of breast cancer |

This is the title of the original awarded grant. Renewals and modifications based on the same grant number are not listed.

Original grant documents missing, only associated publications (or other supporting documents) available

Only the renewal documents available

In the breast cancer science world, CTR funded at least 48 projects on non-tobacco causes of breast cancer (Figure 1: R3). Thirty-two of these projects were related to genetic causes, and nine of them were related to hormonal (estrogen) and dietary causes and mechanisms. Major funded projects are listed in Table 3.

Regarding the research naming breast cancer as the primary cause of women’s death (governmental and voluntary agencies world), the CTR and TI documented studies or presentations suggesting no well-supported link between smoking and breast cancer (Figure 1: R4). For example, in the report of American Public Health Association’s 1979 conference, the PR consultant Hilda Zahn noted the assurance from Ernst Wynder, who found the link between smoking and cancer in 1950, [54] that “we did not (his verbal emphasis) find that cigarette smoking is related to breast cancer.”[55] Regarding breast cancer as a high priority in governmental prevention programs, the TI suggested these programs had been ineffective because breast cancer mortality remained high (Figure 1: R5). A 1987 report written by the TI criticized the National Cancer Institute’s ‘s anti-smoking stance. It pointed out a US$54 million National Cancer Institute -American Cancer Society breast cancer detection program for conflict of interest, being under the influence of American Cancer Society board members who were also National Cancer Institute advisors. The TI also argued that the governmental-initiated breast cancer early detection program was ineffective, and would expose women to more cancer risks by using X-rays.[46,56]

Map 2: CTR and TI Responses to External Threats

The situational threats map (Figure 2) contains three social worlds, four situational threats, and four industry responses. The policy arena represents debates about the health effects of smoking/secondhand smoke on breast cancer between the 1980s and 1990s. When breast cancer was not seen as associated with smoking/ secondhand smoke, it was often used to defend other threats to the industry. As more evidence of secondhand smoke and breast cancer association appeared, breast cancer itself became a threat to the industry.

Epidemiology World

This social world generated two external threats. The first involved Hirayama’s studies about secondhand smoke exposure among married women in Japan in the 1980s, and a few similar studies in the US showing secondhand smoke exposure and increased breast cancer risk (Figure 2: T1).[33,57] While Hirayama’s main findings were related to increased lung cancer risk, the major concern of the industry, results also suggested a marginally increased risk of breast cancer. [33] In his interview with a German medical journal in 1981, he mentioned a borderline significance between passive smoking and breast cancer, and discussed the possibility that passive smoking might be linked to breast cancer.[58] The second situation was related to two epidemiologists, Wells and Morabia (Figure 2: T2). Their studies in the 1990s found increased breast cancer risks associated with secondhand smoke exposure.[59] A letter to the editor by Wells in 1998 reviewed four studies (Sandler, Hirayama, Smith, and Morabia), suggesting a definite increase of breast cancer risk associated with both active and passive smoking.[60]

Governmental and Voluntary Agencies World

This social world represents regulations and reports about smoking/secondhand smoke. This world produced two threats to CTR/TI: 1) the U.S. lung cancer mortality surpassed breast cancer among women in 1987, showing the severity of the increasing smoking rate of women (Figure 2: T3) [34]; and 2) the EPA’s guidelines on public smoking and report of secondhand smoke on respiratory health were released (in 1990 and 1992), which became a threat to the tobacco industry as the guidelines highlighted the health risks of secondhand smoke, and breast cancer was one of the outcomes. [61–63]

Tobacco Industry World

This social world represents CTR/TI responses to the situational threats. In response to threats from the epidemiology world in 1980s, the TI denied the association between secondhand smoke and breast cancer by arguing that smoking was not associated with breast cancer (Figure 2: R1). For example, this argument appeared in a memo responding to a Pennsylvania study showing increased risk of breast cancer among wives exposed to secondhand smoke, that breast cancer has “never been statistically associated with smoking in smokers” (italics by the author).[57]

With more evidence of both secondhand smoke and smoking associated with breast cancer, the TI launched methodological critiques (Figure 2: R2), led by its director of statistics Marvin Kastenbaum, and industry consultant statisticians. [63] In response to Hirayama’s secondhand smoke study, Kastenbaum in a memo pointed out its “flaws” in various statistical analysis techniques, and argued that “the unbiased reader surely will have doubts whether passive smoking actually is the causative factor here”.[58] They also frequently questioned the methodological approaches in studies of Morabia and Wells. [61] Nathan Mantel, a biostatistician who had financial ties with the tobacco industry, wrote about how he challenged Wells by questioning the adequacy of one-sided testing and the odds ratio, and eventually, Mantel claimed in the letter, “Wells reversed himself” to admit the “protective effects” of smoking on breast cancer.[61]

Regarding the threats from the government and voluntary agencies, the TI and CTR recognized that lung cancer surpassing breast cancer as the largest cause of mortality in women was a problem for the industry.[34,61,64] Kastenbaum wrote a memo to an army officer and industry consultant [65], bemoaning that the still-high breast cancer mortality rate was “now being brushed aside in the rush to bring lung cancer in women to the forefront of public attention” (italics by the author),[46] with the prevailing statement that “lung cancer surpasses breast cancer mortality” made the tobacco industry a target of blame

The thesis that lung cancer of nonsmoking women could be metastasis or misdiagnosis of breast cancer was used by the TI to question the rising lung cancer mortality among women due to smoking/secondhand smoke exposure (Figure 2: R3; Figure 2: R4a). Multiple scientists, who had been financially tied to the industry, made such arguments. For example, a UK toxicologist George Leslie pointed out that the death certificate and hospital records data could not tell if the lung cancer diagnosed for women was metastases from breast cancer. [66] The TI misused Lawrence Garfinkel (Vice President of the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics of American Cancer Society)’s caution about the reliability of death certificate as data source, to suggest that non-smoking female deaths attributed to lung cancer in hospital records tended to be misdiagnosis or spread of breast cancer. [67] To respond to the lung cancer and secondhand smoke association made in EPA’s report, “independent scientists” who had worked with the TI in different capacities [66,68] argued that lung cancer that was usually attributed to secondhand smoke, was actually metastasis or secondary to breast cancer.[66,69]

Additionally, in response to the EPA’s risk assessment reports about secondhand smoke and its workplace smoking policy guide [70,71], the TI-recruited scientists challenged EPA’s report on the health effects of secondhand smoke. In particular, they argued that both smoking and passive smoking increasing breast cancer risk was methodologically problematic (Figure 2 R4b).[68]

DISCUSSION

Using the newly developed situational scoping method, we conducted an overview of the 19,719 documents in the CTR/TI collections returned with search term “breast cancer”. This study confirms that there is data in the UCSF Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive in the CTR and TI Records for research and advocacy purposes related to the tobacco industries’ scientific knowledge about breast cancer, and their interference with policymakers’ and the public’s understanding of links between secondhand smoke and breast cancer. We analyzed nine external events during the 1980s and 1990s with the potential to be a threat or opportunity to the business interests of CTR or TI, and CTR and TI’s responses to these events. These responses were centered around conducting industry-funded research that could provide counterarguments to threats, or additional substantiation to opportunities. While we did not find direct evidence of CTR and TI interference with policymaker and public opinion about tobacco use and breast cancer, interference with the body of evidence has indirect impacts on these stakeholders.

Our analysis shows that the CTR responded to external threats and opportunities by actively funding research during the 1980s and 1990s related to non-tobacco related causes of breast cancer, a common strategy to divert attention from tobacco-related health issues.[14] The CTR and TI’s public relations efforts suggest that while breast cancer itself was not the principal concern for the tobacco industry, it could be used to drive the attention away from lung cancer, or it could be seen as an emerging threat. The lack of consensus on smoking and breast cancer association became an opportunity for the TI to argue that many lung cancer cases were breast cancer misdiagnosed or spread and not tobacco related. However, when more evidence showed secondhand smoke was associated with breast cancer, the TI began launching methodological critiques of those threatening studies.

These findings align with previous tobacco document research: tracking and targeting key scientists, [7] paying experts to undermine threatening research,[72] and arguing for epidemiological standards that would better serve industry interests. [73]

Our findings have implications to present-day tobacco control efforts. While the association between breast cancer and secondhand smoke was found even as early as the 1980s, it was not supported by a major scientific consensus. Even with evidence of a causal link between secondhand smoke and younger women’s breast cancer from the California EPA’s 2005 report,[2] and studies over the past 35 years finding increased breast cancer risk associated with secondhand smoke,[4,5] recent clinical guidelines still have not listed secondhand smoke as a risk factor for breast cancer.[74,75] While there may be complicated reasons, this research suggested that the tobacco industry may have a part to play by deflecting attention away from secondhand smoke. Future research should investigate CTR/TI-funded breast cancer research to determine its contribution to the scientific discourse of the external causes of breast cancer. Additionally, other promising areas for further research include examining tobacco industry interactions with governmental and voluntary agencies funding breast cancer related programs, and the discussions of air pollution and other environmental factors causing cancer rather than secondhand smoke.

Research on CTR and TI also has implications for understanding and countering present-day tobacco industry front groups such as the Foundation for a Smoke Free World, (now rebranded as Global Action to End Smoking [76]), established by Philip Morris in 2017.[77] While CTR and TI were dissolved due to the Master Settlement Agreement, industry front groups remain strategic organizations created to promote business interests. These types of organizations should not be allowed to flourish. For researchers and public health experts, more awareness should be drawn to the history of tobacco industry’s funding through front groups and third-party organizations,[14][6] to critically evaluate research studies on related topics for their funding sources, and to advocate for full disclosure of funding sources.[78]

This study also has implications for future tobacco (and other industry) documents research that might benefit from applying the situational scoping method. The situational scoping method allowed us to screen and analyze a large number of documents relevant to the topic of interest, by leveraging the expertise of the community partner as well as our transdisciplinary research team, and incorporating a set of analytical mapping and memoing tools that support a collaborative research process. This intensive model of community engagement with our partner from the outset directed our research toward topics of most interest to community members, therefore making our results more immediately actionable to community stakeholders. Our transdisciplinary team also increased efficiency of documents analysis by setting priorities and contributed to triangulation of tobacco industry events in real time. The situational scoping method also allowed us to connect seemingly separate issues on the same map. For example, the CTR’s connection with the renowned physician Henry Lynch could be a stand-alone story, but our approach placed his CTR-funded research in the larger picture of how genetic causes of breast cancer walked hand in hand with the lack of consensus on smoking and breast cancer for the interests of the industry. Additionally, in this study, breast cancer-related discussions in the documents that might be otherwise overlooked (as they were usually at the peripheral of the tobacco industry’s concern) were brought to the center to form its own unique narrative. For example, while Hirayama was recognized primarily for his research about secondhand smoke and lung cancer, in our analysis, his finding of a marginal increase of breast cancer risk with secondhand smoke exposure was highlighted, [58] making him also part of the breast cancer world (together with Gus Miller in the 1980s and Morabia and Wells in the 1990s).

Finally, the situational scoping method is rooted in social theory, which offers a view of society as social words negotiating issues in contested policy arena which can facilitate cross-industry comparison and enhance our understanding of present-day policy negotiations. We have already seen common practices in other industries being studied. For example, the alcohol industry employed similar strategies to downplay the relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer. [78] Developed by Legg et al., the “science for profit” typology and model also highlights common practices different industries employed to shape scientific evidence to their favor to protect their profits, such as funding research that produced favorable outcomes, establishing their own standards to evaluate science, making a policymaking environment friendly to them, and building a corporate image of trustworthiness.[79] As we plan to report in future manuscripts related to our larger UCSF IDL scoping project, which includes food, chemical, drug and fossil fuel archives, regardless of which health-harming industry is under study, each industry is engaged in the same general action: environmental scanning to identify threats and opportunities to business interests and responding to these external events. From this perspective, cross-industry comparisons can be made related to environmental scanning and response activities, but also, connections can be made by examining firms hired by multiple Accepted health-harming industries to protect business interests.

Study limitations are similar to traditional tobacco documents research, including that documents are of unknown representativeness, important documents may not be available, key information may have been concealed by the industry, and the challenge that large numbers of available documents present to researchers when deciding how to search and retrieve of documents.[27] [80] Since the indexing (e.g. categorizing by date, file type, etc.) of tobacco industry documents is incomplete, and OCR systems capture text imperfectly, keyword searches may still miss some documents.[80,81] Additionally, due to the exploratory nature of our study, the outcome of tobacco industry sponsorship of breast cancer research and the promotion of pro-industry breast cancer discourses on policy and public opinion will need to be confirmed in future studies. This study focused only on a subset of documents related to breast cancer in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive, limiting our findings to the CTR and TI front groups and precluding comparisons to other tobacco industry documents collections. Scoping of additional documents within the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive will be reported separately.

Conclusion

Breast cancer is an outcome that has been overlooked in studies about tobacco industry strategies to influence science, policy, and public opinion. The CTR and TI Records revealed tobacco industry’s past practices related to breast cancer and engagement in activities to shape discourses about smoking, secondhand smoke and breast cancer, including funding research, critiquing unfavorable research, and influencing regulations on secondhand smoke by submitting reports from scientists that were closely tied to the industry. The Situational Scoping Method helps to identify areas worth further investigation, for example, the impact of specific CTR-funded breast cancer research projects, and more detailed accounts of how the tobacco industry leveraged the lack of consensus on the secondhand smoke-breast cancer association to serve their interests.

Supplementary Material

What is already known on this topic

The tobacco industry-funded Center for Tobacco Research (CTR) and Tobacco Institute (TI) -- have played an important role in undermining science, policy, and public opinion on the health risks of tobacco use for decades.

What this study adds

We identified documents from the 1980s and 1990s showing the CTR sponsored research on non-tobacco related causes of breast cancer, and the TI critiqued research showing links between smoking and breast cancer, while framing lung cancer, as misdiagnosed or metastasized breast cancer among nonsmoking women, to counter the evidence about the association between lung cancer and secondhand smoke.

We applied a social theory-based methodology to industry document research to help evaluate large collections of documents and less researched topics.

How this study may affect research, practice, or policy

The Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive data may improve the understanding of the involvement of tobacco industry in etiologic studies of breast cancer for tobacco control researchers, advocates, and policymakers.

This study can inform future documents research to further investigate whether the tobacco industry had a role in shaping the scientific consensus on smoking or secondhand smoke as risk factors of breast cancer.

Acknowledgement

This project would not have been possible without the support and participation of Breast Cancer Action. We are grateful to Jayla Burton, and the leadership and staff of Breast Cancer Action for their partnership. We are also thankful for our other transdisciplinary researchers including Sheyda Aboii and Tracey Woodruff, our facilitator, Annemarie Charlesworth, and the UCSF IDL Archivists, Kate Tasker and Rachel Taketa for their important contributions to this project.

Funding:

This work was supported by the California Breast Cancer Research Program (grant-B27NN42363), the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (grant-K08DE028947), the Samuel Lawrence Foundation and discretionary funds from the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Competing interests None.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts for Women | Most Common Cancers in Women. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/cancer-facts/cancer-facts-for-women.html (accessed 21 December 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glantz SA, Johnson KC. The Surgeon General Report on Smoking and Health 50 Years Later: Breast Cancer and the Cost of Increasing Caution. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:37–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He Y, Si Y, Li X, et al. The relationship between tobacco and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:961970. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.961970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai Y-C, Chen Y-H, Wu Y-C, et al. The Association between Smoking and Mortality in Women with Breast Cancer: A Real-World Database Analysis. Cancers. 2022;14:4565. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glantz SA, editor. The cigarette papers. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong M-K, Bero LA. How the tobacco industry responded to an influential study of the health effects of secondhand smoke. BMJ. 2002;325:1413–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes DE, Bero LA. Industry-Funded Research and Conflict of Interest: An Analysis of Research Sponsored by the Tobacco Industry through the Center for Indoor Air Research. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1996;21:515–42. doi: 10.1215/03616878-21-3-515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drope J, Chapman S. Tobacco industry efforts at discrediting scientific knowledge of environmental tobacco smoke: a review of internal industry documents. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2001;55:588–94. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.8.588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong EK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry efforts subverting International Agency for Research on Cancer’s second-hand smoke study. The Lancet. 2000;355:1253–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02098-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirschhorn N. Second hand smoke and risk assessment: what was in it for the tobacco industry? Tobacco Control. 2001;10:375–82. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cataldo JK, Bero LA, Malone RE. “A delicate diplomatic situation”: tobacco industry efforts to gain control of the Framingham Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63:841–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council for Tobacco Research - SourceWatch. https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Council_for_Tobacco_Research (accessed 6 April 2023)

- 14.Proctor R. Golden holocaust: origins of the cigarette catastrophe and the case for abolition. Univ of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner KE. Tobacco industry scientific advisors: serving society or selling cigarettes? Am J Public Health. 1991;81:839–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.7.839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobacco Institute - TobaccoTactics. https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/tobacco-institute/ (accessed 10 February 2023)

- 17.The Master Settlement Agreement and Attorneys General. National Association of Attorneys General. https://www.naag.org/our-work/naag-center-for-tobacco-and-public-health/the-master-settlement-agreement/ (accessed 24 January 2023)

- 18.Kearns CE. The Situational Scoping Method: A Critical Constructivist Approach for Researching Online Industry Documents. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 19.California Breast Cancer Research Program. California Breast Cancer Research Program. Request for Proposal: Investigating Industry Influence Over Scientific Information on Breast Cancer and the Environment, Exploring the UCSF Industry Documents Library https://cbcrp.org/files/pbc-funding/investigating-industry-influence-rfp.pdf (accessed 5 March 2024)

- 20.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Colquhoun H, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. 2021;10:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter SM, Little M. Justifying Knowledge, Justifying Method, Taking Action: Epistemologies, Methodologies, and Methods in Qualitative Research. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1316–28. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kincheloe JL. Critical constructivism primer. New York: P. Lang; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine M, Torre ME. Essentials of critical participatory action research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breast Cancer Action: Mission, Vision, and Values. 2024. https://www.bcaction.org/mission-vision-and-values/

- 25.Clarke AE, Friese C, Washburn R. Situational analysis: grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Second edition Los Angeles: SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch Hadorn G, editor. Handbook of transdisciplinary research. Dordrecht; London: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson SJ, McCandless PM, Klausner K, et al. Tobacco documents research methodology. Tobacco Control. 2011;20:ii8–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke AE. From Grounded Theory to Situational Analysis. In: Morse J, Bowers BJ, Charmaz K, et al. , eds. Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation Revisited. New York: Routledge; 2021:223–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach to Obtaining Meaningful Input From Stakeholders to Inform Research. Academic Medicine. 2015;90:1646–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legislative Analyst’s Office: The California Legislature’s Nonpartisan Fiscal and Policy Advisor. 2010. https://lao.ca.gov/ballot/2009/090811.aspx (accessed 5 March 2024)

- 31.Legislative Mandate for Tobacco Control Proposition 99. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CTCB/Pages/LegislativeMandateforTobaccoControlProposition99-.aspx (accessed 5 March 2024)

- 32.Zahn L, Leonard Zahn Associates, Zahn H. International Conference On Smoking and Reproductive Health, San Francisco, Oct. 15-17, 1985. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirayama T. Non-smoking wives of heavy smokers have a higher risk of lung cancer: a study from Japan. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:183–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6259.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. The Female Smoker: At Added Risk; Some Facts From The World Health Organization. Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:i–iv; 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg L, Schwingl PJ, Kaufman DW, et al. Breast Cancer and Cigarette Smoking. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:92–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401123100205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.92- The New England Journal Of Medicine Jan. I_ 1984 Breast Cancer and Cigarette Smoking. 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D, Cole P, et al. Cigarette Smoking and Urinary Estrogens. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1062–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210213071707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMahon B, Trichopoulos D, Cole P, et al. Cigarette Smoking and Urinary Estrogens. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch H, Mulcahy G, Guirgis H, et al. Genetic and Pathologic Findings In a Kindred With Hereditary Sarcoma Breast Cancer, Brain Tumors, Leukemia, Lung, Laryngeal, and Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma; Cancer Vol 41 No 5. 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammond C. Our life styles can put us on collision courses with cancer. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horace Kornegay William Kloepfer, Jr.

- 43.To: Robert F. Gertenbach CC: WDH. 1987.

- 44.National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society. National Cancer Institute & American Cancer Society ASSIST Program. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The National Cancer Institute: Report Prepared by the Information Center of the Tobacco Institute. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kastenbaum MA. Breast Cancer. Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 47.GBG. On The Positive Side. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unknown. Number 318. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becke KL. Texas Proposed Legislation. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unknown. Tobacco Institute Newsletter Informing The Industry Of Newsworthy Developments. Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement Unknown [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadohama N. Tobacco Alkaloid Derivatives As Inhibitors Of Breast Cancer Aromatase Cancer Letters, Volume 75. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fontana J. Interaction Of Retinoids And Tamoxifen On The Inhibition Of Human Mammary Carcinoma Cell Proliferation Expl Cell Biol. 55. 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finlay TH, Tamir S, Kander SS, et al. A1-antitrypsin- And Anchorage-independent Growth Of Mcf-7 Breast Cancer Cells; Endocrinology, Vol 133 No 3. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wynder EL. Tobacco Smoking As A Possible Etiologic Factor In Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of Six Hundred and Eighty-Four Proved Cases. JAMA. 1950;143:329. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910390001001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leonard Zahn & Associates, Zahn. American Public Health Association New York, 19791104–19791108. 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 56.The Information Center of Tobacco Institute. The National Cancer Institute. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bill Kloepfer Bill Toohey Gus Miller Study: “Cancer, Passive Smoking and. Published Online First: 18 April 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kastenbaum MA. Memo From Kastenbaum Re Translation of an Article That Will Appear in a Principle Medical Journal in Germany Ill Due To Passive Smoking? Interview With Dr. Hirayama 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson KC, Samet JM, Glantz SA. A Judson Wells, PhD (1917–2008): a pioneer in secondhand smoke research. Tobacco Control. 2008;17:e5–e5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wells AJ. Re: “Breast Cancer, Cigarette Smoking, and Passive Smoking.” American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147:991–2. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mantel N. Commentary Respiratory Health Effects of Passive. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith CJ. Comments on: Environmental Tobacco Smoke: A Guide to Workplace Smoking Policies Response Addressing: Chapter 3: Health Effects of ETS Section: Cancer at Other Sites Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whidden P. Re: Relation Of Breast Cancer With Passive and Active Exposure to Tobacco Smoke. Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General </P>. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5112a4.htm (accessed 20 May 2023)

- 65.Adlkofer Franz - SourceWatch. https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Franz_Adlkofer (accessed 18 May 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Environmental Protection Agency, Leslie GB, Mantel N, et al. Health Effects Of Passive Smoking: Assessment Of Lung Cancer in Adults and Respiratory Disorders in Children Public Review Draft Comments of Scientists; Volume IV. Published Online First: October 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Document Garfinkel II. Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mantel N. Commentary Respiratory Health Effects Of Passive. Published Online First: July 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee PN. Weaknesses in Recent Risk Assessments of Environ1kental Tobacco Smoke. Published Online First: 11 January 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lippmann ML. Science Advisory Board’s review of the Office of Research and Development document Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Assessment of Lung Cancer in Adults and Respiraory Disorders in Children, EPA/600/6–90/006A, June 1990, and the Office of Air and Radiation’s draft document Environmental Tobacco Smoke: A Guide to Workplace Smoking Policies, (EPA/400/6–90/004, June 1990. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 71.EPA. Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders. Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Landman A, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Efforts to Undermine Policy-Relevant Research. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:45–58. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ong EK, Glantz SA. Constructing “Sound Science” and “Good Epidemiology”: Tobacco, Lawyers, and Public Relations Firms. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1749–57. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Breast cancer - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/breast-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20352470 (accessed 21 December 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 75.CDC Breast Cancer. What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/risk_factors.htm (accessed 21 December 2022)

- 76.Global Action to End Smoking. Tobacco Tactics. 2024. https://tobaccotactics.org/article/global-action-to-end-smoking/

- 77.Legg T, Clift B, Gilmore AB. Document analysis of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World’s scientific outputs and activities: a case study in contemporary tobacco industry agnogenesis. Tob Control. 2023;tc-2022–057667. doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, et al. The strategies of alcohol industry SAPROs: Inaccurate information, misleading language and the use of confounders to downplay and misrepresent the risk of cancer: Letter to the Editor. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2018;37:313–5. doi: 10.1111/dar.12677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Legg T, Hatchard J, Gilmore AB. The Science for Profit Model—How and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0253272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carter SM. Tobacco document research reporting. Tobacco Control. 2005;14:368–76. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malone RE. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tobacco Control. 2000;9:334–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Padlet. Padlet. padlet.com (accessed 1 March 2024) [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jamboard Google. Google Jamboard. https://jamboard.google.com/ (accessed 1 March 2024) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morabia A, Bemstein M, Hritier SP, et al. Relation of Breast Cancer with Passive and Active Exposure to Tobacco Smoke. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;143:918–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Unknown. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service National Institutes of Health. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Taylor J. Cancer Risks or Thee but Not for Me In October you may recall the Journal of the National Cncer Institute caused quite a stir by publishing an epidemiological study suggesting that women who have abortions are more likely to develop breast cancer than. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ecobichon DJ, Wu JM, Heath DC. Report: Environmental Tobacco Smoke Proceedings of the International Symposium at McGill Univ 1989. Tobacco Institute Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cohen D;H. re: A new grant application, #845, from Eleanor J. Macdonald 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Evans F, Lynch HT. Application For Research Grant Hereditary Factors, Cigarette Smoking, and Cancer Incidence in 3,261 Families. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lynch HT, Shaddy RW. Application For Research Grant Genetic and Biomarker Studies of Smoking-Associated Cancers. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lynch H. Call from Rose Kushner. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Albano Fusaro, Lynch, et al. Memoradum. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lynch HT. Unknown. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lynch H. Meetings With And Letter From Leonard Zahn Regarding Our Institute. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 95.McNamara JG. Unknown. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fitzgerald TA, Sklarew RJ. Application For Renewal Of Research Grant Cytokinetics Of Heteroploid Subpopulations By Imaging. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Osawa Y. Unknown. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Osawa Y. Application For Research Grant Aromatase Inhibitors In Cigarette Smoke And Tobacco. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 99.CTR, Oppermann KR, Sirbasku DA. Application For Research Grant Estrogen-Responsive And Autonomous Human Breast Cancer Growth. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sirbasku DA, CTR, Kleasner KF. Application For Renewal Of Research Grant Estrogen-Responsive And Autonomous Human Breast Cancer Growth. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bradlow HL, MichnoviIz JJ, CTR. Application For Renewal Of Research Grant Estrogen Metabolism In Relation To Cancer Risk. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bradlow HL, Michnovicz JJ, Nichols RW. Application For Renewal Of Research Grant Estrogen Metabolism In Relation To Cancer Risk. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fanning TG. Research Grant Application Function Of Line 1 Retrotransposons In Human Breast Cancer. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Finlay TH. Competing Renewal Application Proteases, Protease Inhibitors And Growth Factors In Breast Cancer. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Finlay TH. Competing Renewal Application Proteases, Protease Inhibitors And Growth Factors In Breast Cancer. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stevens VL. Research Grant Application Mechanism Of Release Of GPI-Anchored Proteins From Breast Cancer Cells. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Samuels HH. Research Grant Application Growth Suppression of Breast Tumor Cells By Retinoids. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stevens JL. Research Grant Application Calcium And Apoptosis In Breast Cancer Cells. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 109.CTR Friend SH, Isselbacher KJ. Application For Research Grant Tumor Suppressor Genes, Tumor Formation and Development. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 110.CTR Miller NS. Research Grant Application Interactions Between C-Src and Her Family Members in Human Breast Tumors. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ward KA, Xiao JZ. Research Grant Application Role of Cyclin D1 and Rb-Mdm2 In Breast Cancer. Council for Tobacco Research Records; Master Settlement Agreement 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.