Abstract

Objective:

This narrative literature review aims to explore the current landscape regarding the management of patient mental health disclosures and gaps in resources and protocols within Canadian dental and dental hygiene programs.

Methods:

CINAHL and Education Source databases, and the Journal of Dental Education were used to search for literature published between 2001 and 2023.

Results:

A total of 54 sources were included, primarily comprising original research articles, systematic and other literature reviews.

Discussion:

The prevalence of mental health disclosures is rising, with 1 in 5 Canadians living with a mental health condition. Current dental and dental hygiene programs lack explicit protocols for managing patient mental health disclosures, and the literature reveals a scarcity of research on students’ preparedness. This review underscores the importance of adopting humanistic language to reduce stigma and emphasizes educational institutions’ roles in evaluating and facilitating mental health services to support the mental health lived experiences of dental and dental hygiene patients.

Conclusion:

The review identifies 3 key research gaps: the absence of qualitative research on the student experience of managing patient disclosures, unclear integration of mental health education, and a scarcity of comprehensive evaluations of mental health services. Recommendations include incorporating mental health training in entry-to-practice curricula, aligning with established community support frameworks, and creating dedicated resources for the effective management of mental health disclosures for patients in educational settings.

Keywords: dental education, dental hygiene education, dental school curricula, humanistic language, mental health, mental health disclosures, qualitative research, stigma reduction

Abstract

Objectifs :

Cet examen narratif vise à explorer le paysage actuel en matière de gestion des divulgations de renseignements sur la santé mentale des patients ainsi que les lacunes dans les ressources et les protocoles au sein des programmes canadiens de dentisterie et d’hygiène dentaire.

Méthodes :

Des recherches ont été effectuées dans la documentation publiée entre 2001 et 2023 dans les bases de données CINAHL et Education Source et dans le Journal of Dental Education.

Résultats :

Un total de 54 sources a été retenu, comprenant principalement des articles de recherche originaux, des examens systématiques et d’autres analyses documentaires.

Discussion :

La prévalence des divulgations de renseignements sur la santé mentale est en croissance : 1 Canadien sur 5 vit avec un trouble de santé mentale. Les programmes actuels de dentisterie et d’hygiène dentaire ne comprennent pas de protocoles explicites pour la gestion des divulgations de renseignements sur la santé mentale des patients, et la documentation révèle que peu de recherche a été effectuée sur la préparation des étudiants. Cet examen souligne l’importance d’adopter un langage humaniste pour réduire la stigmatisation et met en évidence le rôle des établissements d’enseignement dans l’évaluation et la facilitation des services de santé mentale afin de soutenir les expériences vécues en matière de santé mentale par les patients en dentisterie et en hygiène dentaire.

Conclusion :

L’examen révèle 3 lacunes de recherche clé : l’absence de recherche qualitative sur l’expérience des étudiants en matière de gestion des divulgations des patients, l’intégration peu claire de l’éducation en santé mentale et la rareté d’évaluations exhaustives des services de santé mentale. Les recommandations comprennent l’intégration d’une formation en santé mentale dans les programmes d’études menant à la pratique, l’harmonisation avec les cadres de soutien communautaire établis et la création de ressources dédiées à la gestion efficace des divulgations de renseignements sur la santé mentale pour les patients dans les milieux éducatifs.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS RESEARCH.

Health care professionals need to adopt humanistic and inclusive language to reduce stigma related to mental health.

Dental and dental hygiene education programs need to integrate appropriate training to prepare practitioners to manage patient mental health disclosures.

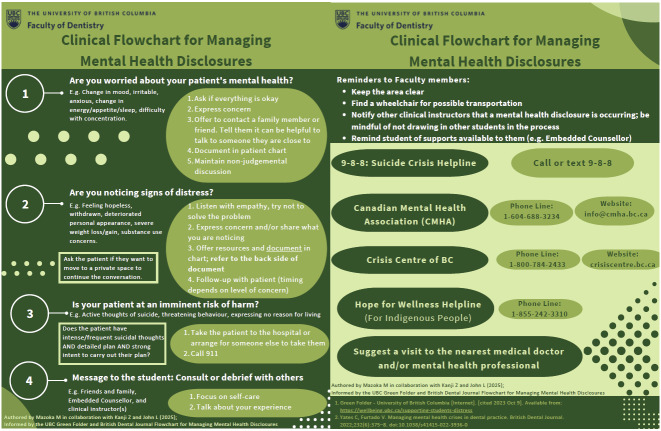

This review led to the development of a clinical flowchart for the management of patient mental health disclosures which can be used by Canadian oral health students and professionals.

INTRODUCTION

Mental health is the psychological and emotional status of one’s well-being.1 It can be influenced by experiences, relationships, employment or educational environments, physical health, and the trust, support, and/or stigma in the community.1 Currently, 1 in 5 Canadians live with mental illness.2, 3 Recognizing this prevalence among health care patients, peers, and colleagues inspired an investigation into the management of patient mental health disclosures. Mental illness is a condition that impacts cognition, emotion, and behaviour whereas the understanding of mental health has shifted towards a more holistic perspective, emphasizing overall well-being rather than merely the absence of disease.4 The understanding of mental health in the 1960s and 1970s moved beyond limited diagnoses such as schizophrenia or depression to encompass a broader spectrum of conditions, reflecting a growing recognition of mental health as integral to overall health and well-being.4

The Mental Health Commission of Canada estimates the current and projected Canadian population living with mental illness over the next 3 decades.3 The data indicate that mental illnesses are most prevalent among individuals aged 20 to 40 years, with anxiety and mood disorders being the most common in this group.3 A comparison between females and males reveals a consistent trend: as age increases across each decade, the prevalence of mental illness steadily rises for both groups.3 In the next 3 decades, the number of people living with mental illness is forecasted to increase by 31%, reaching 8.9 million Canadians compared to the 6.9 million Canadians currently living with a mental illness.3

Using humanistic terms such as “individual” or “person with lived experience” can reduce the stigma associated with the terms “mental illness” and “mental disorder,” which this narrative literature review aims to do.5, 6 An article published in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry noted that poor oral health is correlated to mental health lived experiences; there is a higher prevalence of edentulism and caries (as determined by the number of decayed, missing or filled teeth) in people with severe mental illness than in the general population.7, 8 Those with mental health lived experiences commonly have poor oral health outcomes due to medication side effects, smoking, drug misuse, and poor oral self-care behaviours.8 Moreover, substance use, economic hardship, sociodemographic, and behavioural factors have been consistently associated with mental health lived experience incidence and prevalence.9, 10 Individuals may reach a breaking point in their mental health where immediate help and support are critical, such as experiencing suicidal ideation, self-harm or anxiety attacks.11

Stigma can be a barrier to help-seeking among young people with mental health lived experiences; additionally, internalizing any prejudices against individuals can lead to higher levels of self-stigma.12, 13 Statements such as “I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness” or “I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness” are examples of how self-stigma and stigma affect individuals.13, 14

Stigma also leads to avoidance and underuse of oral health and medical services, including mental health care, which may exacerbate inequality among those with severe mental illness.12, 15, 16 Oral health professionals engage in ongoing continuing education for managing medical emergencies.11 However, mental health emergencies are usually not integrated into that learning, resulting in discrepancies and challenges in managing all medical emergencies.11 In Canadian educational institutions, there is a scarcity of research and protocols for the management of mental health emer,gencies among dental and dental hygiene patient populations. It is suggested that adequate management of stress and mental health disorders needs to be included in the treatment of clinical manifestations.17 This review aims to explore resources and experiences that dental and dental hygiene students need to support their patients with mental health lived experiences and disclosures. The review of literature and gaps identified culminated in the development of a clinical flowchart to assist student practitioners in the management of their patients’ mental health disclosures.

METHODS

The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Education Source databases (accessed through the University of British Columbia’s online library), as well as the Journal of Dental Education’s website, were used to search for relevant literature. The search terms were mental health, mental illness, patient disclosures, oral health, dentistry, Canada, prevalence, mental health emergency, mental health crisis management, mental health resources, and health care. Fifty-four sources published in the English language between 2001 and 2023 were included. The research articles included in this narrative literature review consisted of 9 literature reviews, 13 quantitative research studies (including 7 descriptive studies), 3 observational studies, and 3 qualitative research studies, along with 1 systematic review, 2 meta-analyses, 1 mixed methods study, and 15 program evaluations. Relevant data extracted from the selected articles encompassed mental health disclosures, the prevalence of mental health experiences among dental patients, management of mental health emergencies in oral health care settings, available health care resources, and any other pertinent information on how mental health is addressed within Canadian dental and dental hygiene programs. Single descriptive case reports and opinion pieces as well as studies not published in English were excluded.

RESULTS

The analysis of the sources included in this narrative literature review revealed 5 key themes: 1) prevalence and incidence trends; 2) the impact of stigma on health care delivery; 3) experiences in health care environments; 4) preparation of the academic community for mental health emergencies; and 5) protocols for managing mental health emergencies. The sections that follow underscore the complexity of addressing mental health within educational and oral health care settings, and advocate for integrated approaches that prioritize patient well-being and enhance health care provider preparedness.

Prevalence and incidence trends

RiskAnalytica projected the economic and health impact of major mental illnesses in Canada over 30 years (from 2011 to 2041) in a December 2011 publication.3 More recently, an article in the American Journal of Public Health analyzed mental health emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic, reporting a potential increase based on data from previous public health crises.9 Longitudinal data are necessary to confirm these rising challenges.3, 9 While the RiskAnalytica trajectory did not anticipate COVID-19, an updated report by the Mental Health Commission of Canada emphasized the exacerbated mental health challenges during the pandemic, including increased suicidal ideation and attempts.18, 19 In 2020, 50% of Canadians reported that their mental health had worsened since the beginning of the pandemic.20, 21 Later that year, Statistics Canada reported a 14% decline in rating mental health as “very good” or “excellent” since 2018.20, 21

Risk factors such as low education and income levels increase the likelihood of developmental disabilities and mental health lived experiences.12 However, studies have shown that poverty alone may not always be directly linked to mental health lived experiences; factors such as economic hardship, societal pressures found in the workplace (workload, job control, and social support), gender, unmet mental health needs, and help-seeking behaviour also play significant roles.9, 12, 22 In local communities, mental health resources may be insufficient, creating another barrier to care.12 The World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (AIMS) highlights that disadvantaged populations, such as individuals experiencing homelessness and refugees, often have higher rates of mental health lived experiences due to inadequate strategies for delivering equitable care across all demographics and locations.12 In assessing an individual’s risk of experiencing a mental health emergency, experts have identified possible opportunities, goals, and life events as precipitators of stress.23

The impact of stigma on health care delivery

Caution should be used when referring to individuals with mental illness.24 Currently, health care providers are urged to ask their patients how they would prefer to be addressed.5, 24 Using the person’s name, “person” or “individual with a (specific illness)” is suggested.23 Furthermore, the terms “individual” or “person with lived experience” were identified in various Australian studies as preferred terms.5, 24 These terms allow for empowerment and are focused on recovery.5

The word “stigma” originates from ancient Greece; today, it can be conceptualized as an individual being stereotyped and/or socially excluded because of negative attitudes or beliefs held by others.16, 25, 26 Stigma is associated with an individual’s mental health lived experience and often emerges in interactions with populations, even health care providers.13, 27 For Canadian families, stigma could lead to fear, shame, inability to cope, helplessness, and hopelessness.16 Mental health professionals see stigma as mental health outlets being scrutinized or viewed with disgust or suspicion.16 In Canada, education on culturally sensitive approaches and trauma-informed care is essential to ensure health care providers can work effectively with stigmatized groups.15, 27 Without proper awareness, stigma can hinder improving Canada’s mental health services.13, 16 Implementing anti-stigma interventions can lead to system improvement and mental health reform.13 Philosophical or cultural beliefs can be a barrier to recovery from mental health lived experiences; further research is needed to inform strategies to reduce stigma while increasing the quality of care.13, 16

Experiences in health care environments

In Canada, the life circumstances of patients (e.g., mental health lived experience and addiction) may not be fully understood by health care professionals, thus contributing to stigma.27 Oral health care providers have limited access to complete medical histories, as that information is recorded following the patient’s disclosure.27 Patients often debate whether to disclose their entire history, fearing the negative stereotypes a health care provider may hold.27 Outside of the dental and dental hygiene professions, individuals may stigmatize patient populations (e.g., those with substance use disorders or with HIV) in health care settings, leading to a reduced likelihood of their seeking or receiving treatment.26-28 What worked for participants in the dental office was noticing when the oral health professional maintained eye contact, spoke in a caring voice, attempted to manage the pain, and allocated time to explain the procedure(s).16 An increased awareness and understanding of mental health conditions by oral health professionals may improve the care experiences of marginalized populations.27

Preparing the academic community for mental health emergencies

Currently, Canadian educational institutions offer suicide awareness and intervention training (SAIT) as well as mental health first-aid courses to enhance student and faculty confidence in responding to mental health emergencies and building rapport so as to manage crisis situations effectively.11, 29 SAIT is a free introductory course for University of British Columbia (UBC) Vancouver and Okanagan students, faculty, staff, and alumni, offering guidance on how to engage in supportive conversations with anyone having suicidal thoughts and how to identify appropriate resources for them.29 Aside from SAIT, UBC has campus-specific guides with tips and information on promoting student health and well-being.29 A resource similar to UBC’s Green Folder and Blue Folder was created by the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University in London, Ontario, which offers guidance on responding to a student having a mental health emergency.30, 31 Practical resources developed by Canadian institutions provide effective approaches and a holistic framework for managing patient mental health disclosures and emergencies in dental and dental hygiene programs, ensuring comprehensive care and support for both students and patients.

Protocols for managing mental health emergencies

Alongside students, oral health professionals also need to know the available support networks to access when patients present with urgent mental health needs, i.e., a mental health emergency.11 Since December 2023, the Canada 9-8-8 Suicide Crisis Helpline has been delivering 24/7 support that is bilingual, trauma informed, and culturally sensitive, for anyone in Canada who may have suicidal thoughts or is seeking help for someone they care about.32

Oral health professionals must understand their patients’ full medical histories, including medications, diagnoses, and support from specialists.11 Nursing care plans and hospital admissions go one step further to use standard checklists that screen patients for risk factors.7 The checklists often include information on psychotropic medication, tobacco or substance use.7 In a mental health emergency, having a flowchart or model of care on the management techniques can streamline the referral process, thus providing oral health care teams with the skills and confidence to manage these high-pressure situations appropriately.11, 33 In addition, having appropriate follow-up services and strategies to monitor all patients provided with mental health services can ensure adequate support for the at-risk patient(s).11, 33 The oral health care team needs to be prepared to improve oral health status and respond to public health emergencies, thus, preventing life-threatening situations.34

DISCUSSION

Patients who visit dental offices should expect to have not only their oral health needs met, but also other health needs such as lived experiences with mental health as part of a holistic, person-centred approach to care.7, 27 Oral health care teams must recognize the profound impact that oral health has on overall health outcomes across all ages, cultures, socioeconomic circumstances, and genders, where stress and mental health lived experiences can result in poor oral hygiene due to behaviour modifications.3, 17, 33, 35, 36 Medications for mental health lived experiences (e.g., psychotropic medications) commonly have adverse effects directly affecting oral health, with xerostomia being the most prevalent, followed by excessive salivation, dysgeusia, and tardive dyskinesia.7, 37 Current research suggests a relationship between mental health and oral health. However, the significance of that relationship needs further examination, as outlined by many studies included in this narrative review.7, 38-40 One evidence-supported conclusion is that poor oral health significantly affects the quality of life of patients.7, 38

Gaps in providing care

An essential finding to support this narrative literature review pertains to the strategies medical and oral health care providers can employ when supporting vulnerable populations, beginning with mental health self-care. The consequences of anxiety and stress that dental and dental hygiene students experience can influence their ability to manage patient anxieties adequately.19 To alleviate that concern, educational institutions offer support to students with mental health lived experiences. However, in an oral health care setting and within the Faculty of Dentistry at UBC specifically, there was no protocol for helping students manage patients with such mental health experiences and disclosures.29

The university’s Emergency Medical Response Plan (2022–2023) allows all clinical instructors, students, and employees at the UBC Dental Clinic to follow an organized flowchart on the management of medical emergencies (e.g., unresponsive person, fainting/collapse, chest pain, shortness of breath, seizure, presumed overdose, and severe allergic reaction [anaphylaxis]).41 However, the management of a mental health emergency is not discussed in this resource.41

Development of a clinical resource to manage patient mental health disclosures

This narrative literature review was conducted by a student in UBC’s Dental Hygiene Degree Program, where a patient experience inspired an investigation into the current and future direction of policies on the management of mental health emergencies within the university, the province, and nationally. The research reviewed in this paper identified a gap in providing patient-centred care by considering the mental well-being of patients.42-46 To graduate competent practitioners, Canadian dental and dental hygiene programs should consider how the most vulnerable populations are treated and ensure that the principle of beneficence is upheld for all patients.42, 43 Identifying this gap provides the impetus for Canadian educational institutions to adopt a standardized protocol to manage mental health emergencies experienced by their patient populations. To effectively address mental health lived experiences within educational institutions, it is essential to integrate provincial and nationwide emergency resources accessible to students, faculty, staff, and alumni, similar to an emergency medical response plan. This comprehensive approach would ensure that all members of the academic community receive timely and appropriate support.

Before introducing the proposed resource (Figure 1), it is important to evaluate the current state of educational preparation in dental and dental hygiene programs for the management of patients’ mental health. Existing dental and dental hygiene curricula often lack sufficient education on the mental health needs of patients and do not consistently include clinical resources for referring individuals with mental health lived experiences.7, 11, 16, 27 To address this deficiency, a specialized clinical resource tailored to dental and dental hygiene students was developed. This resource provides targeted guidance for student practitioners needing to manage their patients who experience mental health emergencies.

Figure 1.

Clinical flowchart for managing mental health disclosures*

*Please visit cjdh.ca and select the June 2025 issue (vol 59, no 2) to view this clinical resource in full size.

The first author, who was enrolled in UBC’s Dental Hygiene Degree Program, developed Figure 1 in collaboration with the UBC Faculty of Dentistry’s Director of Student Affairs and the faculty’s Embedded Counsellor. The aim was to provide a tool for recognizing, assisting, and resolving mental health emergencies, and to make this resource available to UBC students in the Faculty of Dentistry so they could effectively support their patients during such mental health disclosures.

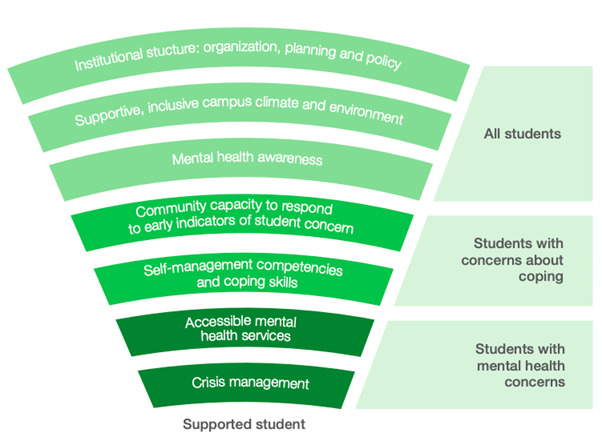

Three key sources significantly contributed to addressing the research question behind this review and resulting clinical resource. First, a guide prepared jointly by the Canadian Association of College & University Student Services and the Canadian Mental Health Association emphasizes a structured approach to enhancing mental health within educational settings, advocating for comprehensive integration of mental health support tailored to the needs of both students and patient populations.47 Second, an article in CDA Essentials underscores the importance of integrating mental health services into dental and dental hygiene education, promoting student well-being and enhancing patient care outcomes.48 Lastly, an article by Yates and Furtado highlights the value of implementing clinical flo,wcharts and models of care to streamline referral processes and enhance oral health care teams’ capabilities to address high-pressure situations appropriately.11

Dental and dental hygiene student well-being

In addition to addressing the mental health needs of patients, educational institutions must ensure that comprehensive and accessible support mechanisms are available for their student body, where mental health lived experiences are common.19, 34, 49 The release of The World Health Report 2001 raised awareness of mental health concerns significantly, but this heightened awareness has not yet led to the necessary investment in adequate resources.12, 50 To effectively support dental hygiene students and address their mental health lived experiences, Partido et al.51 emphasized the urgent need for targeted interventions to combat burnout. Their study revealed, notably, that 38% of dental hygiene students at one institution reported experiencing symptoms of burnout.51 The study also examined the reciprocal relationship between health care students’ mental well-being and the quality of patient care they provided.51 It is crucial for public health stakeholders, mental health agencies, government bodies, and policymakers to allocate appropriate resources to support health care students and the broader population.52

Currently, at Canadian universities, a unified framework for mental health promotion appears to be absent. The Canadian Mental Health Association’s guide (Figure 2) offers a systemic approach to improving student mental health, recovery, and well-being in institutional settings.47 It is equipped to address the needs of diverse student populations, enabling all learners to engage meaningfully in decision making, skill building, and drawing on their lived experiences with mental health.47 Universities offer mental health supports, such as mindfulness activities, stress relief days, and animal therapy to decrease stress and increase social engagement.53 Effective mental health support is crucial for better managing mental health disclosures, enhancing overall student well-being, and improving patient outcomes.

The comprehensive approach depicted in Figure 2 ensures timely and appropriate support for all academic community members. It offers targeted guidance, allowing students to address mental health crises while upholding their professional duties. This dual strategy—broad integration of mental health resources and specialized support—may significantly enhance mental health management across educational settings. While these initiatives have great potential to address mental health within dental and dental hygiene education, there remains a critical need to broaden and standardize such approaches across all Canadian dental and dental hygiene programs.

Recommendations for Canadian dental anddental hygiene programs

Incorporate suicide awareness and intervention training, mental health first aid, and trauma-informed care into the curriculum.

Align with the Canadian Mental Health Association’s framework for addressing the needs of both post-secondary students and patient populations.

Integrate nationwide mental health emergency resources accessible to students, faculty, staff, and alumni.

Create a dedicated resource to support dental and dental hygiene students in effectively managing patients experiencing a mental health emergency (as depicted in Figure 1).

Research gaps and future research directions

The narrative literature review has highlighted a scarcity of resources for managing patient mental health emergencies, particularly evident in the lack of qualitative research on how dental and dental hygiene students approach such crises, with a predominant reliance on quantitative methodologies. Three primary research gaps emerge: first, investigations are lacking into how dental and dental hygiene programs, especially in Canada, manage mental health emergencies, emphasizing the need for comprehensive assessments of the protocols and practices employed. Second, there is a lack of clarity on how the integration of mental health education into curricula contributes to students’ well-being as they transition into professional roles.19 Third, there is a scarcity of comprehensive evaluations of the effectiveness of various student mental health and wellness services.19, 40, 54 Public health stakeholders, mental health agencies, government officials, and policymakers should recognize the limited availability of mental health emergency protocols and the uncertain contribution of skills acquired in an educational setting to students’ well-being as they transition into future professionals.19, 54 Future research should adopt humanistic terms to reduce stigma associated with mental health, exploring their impact on public perception.5, 6 The evaluation of student mental health services, understanding factors influencing service utilization, and optimizing support systems for diverse student populations represent critical areas for future investigation.19, 40, 54 Recommended research methods are surveys, interviews, content analysis, longitudinal studies, and case studies to comprehensively evaluate mental health interventions.

Figure 2.

Framework for post-secondary student mental health

Canadian Association of College & University Student Services and Canadian Mental Health Association. Post-secondary student mental health: Guide to a systemic approach. 2013. Available from: https://healthycampuses.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/The-National-Guide.pdf

CONCLUSION

When working with the public, especially within educational institutions, it is essential that all students, faculty, and staff be familiar with the procedures and protocols for managing patient mental health emergencies.47 This awareness is crucial, given the current evidence of the limited educational preparedness of dental and dental hygiene students in managing mental health emergencies when treating patients. Therefore, developing a decision-making framework to support students in these situations is imperative. The insufficient support for dental and dental hygiene students in addressing their own mental health underscores the impact on the quality of patient care, highlighting the pressing need for developing comprehensive resources to effectively promote their mental well-being.51

Disseminating timely and accurate information to individuals involved during a mental health emergency can ensure the crisis is averted and handled with care.47 Crisis management protocols are crucial to ensuring that educational institutions can respond to the risk of self-harm.37 Incorporating mental health awareness initiatives within a supportive and inclusive campus climate may encourage adequate self-management, responses, and capacity to manage a mental health emergency within Canadian educational institutions effectively.47

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

CDHA Research Agenda category: capacity building of the profession

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. About Mental Health [Internet]. ©2020 [cited 2023 Aug 23]. Available from: canada.ca/en/publichealth/services/about-mental-health.html

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. The Mental Health Commission of Canada 2017–2022 strategic plan [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): MHCC; 2016. [cited 2023 Dec 2]. Available from: canadacommons.ca/artifacts/1218659/the-mental-healthcommission-of-canada-2017-2022-strategic-plan/1771734/ [Google Scholar]

- Smetanin P , Stiff D , Briante C , Adair CE , Ahmad S , Khan M . The life and economic impact of major mental illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041. Toronto (ON) : : RiskAnalytica ; , on behalf of the Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2011 . Available from: mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/MHCC_Report_Base_Case_FINAL_ENG_0_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Manderscheid RW , Ryff CD , Freeman EJ , McKnight-Eily LR , Dhingra S , Strine TW Evolving definitions of mental illness and wellness Prev Chronic Dis 2010 ; 7 ( 1 ) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AS , Mortimer-Jones SM Terminology preferences in mental health Issues Ment Health Nurs 2020 ; 41 ( 6 ): 515 – 524 doi: 10.1080/01612840.2020.1719248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AS , Mortimer-Jones SM The relationship between terminology preferences, empowerment and internalised stigma in mental health Issues Ment Health Nurs 2021 ; 42 ( 2 ): 183 – 195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S No mental health without oral health Can J Psychiatry 2016 ; 61 ( 5 ): 277 – 282 doi: 10.1177/0706743716632523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner E , Berry K , Aggarwal VR , Quinlivan L , Villanueva T , Palmier-Claus J Oral health self-care behaviours in serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis Acta Psychiatr Scand 2022 ; ( 145 ): 29 – 41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holingue C , Kalb LG , Riehm KE , Bennett D , Kapteyn A , Veldhuis CB , et al. Mental distress in the United States at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic Am J Public Health 2020 ; 110 ( 11 ): 1628 – 1634 doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylipaavalniemi J , Kivimäki M , Elovainio M , Virtanen M , Keltikangas-Järvinen L , Vahtera J Psychosocial work characteristics and incidence of newly diagnosed depression: a prospective cohort study of three different models Soc Sci Med 2005 ; 61 ( 1 ): 111 – 122 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates C , Furtado V Managing mental health crises in dental practice Br Dent J 2022 ; 232 ( 6 ): 375 – 378 doi: 10.1038/s41415-022-3936-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S , Thornicroft G , Knapp M , Whiteford H Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency Lancet 2007 ; 370 ( 9590 ): 878 – 889 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61239-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y , Wolf A , Wang X Experienced stigma and self-stigma in Chinese patients with schizophrenia Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013 ; 35 ( 1 ): 83 – 88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanean H , Nojomi M , Jacobsson L Internalized stigma of mental illness in Tehran, Iran Stigma Res Action 2011 ; 1 : 11 – 17 doi: 10.5463/SRA.v1i1.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Mental Health Association. Stigma and Discrimination [Internet]. n.d. [cited 2023 Aug 23]. Available from: ontario.cmha.ca/documents/stigma-and-discrimination/ .

- Brondani MA , Alan R , Donnelly L Stigma of addiction and mental illness in healthcare: The case of patients’ experiences in dental settings PLoS ONE 2017 ; 12 ( 5 ): e0177388 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J , Darby I Mental health and periodontal and peri‐implant diseases Periodontol 2000 2022 ; 90 ( 1 ): 106 – 124 doi: 10.1111/prd.12452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J Roots of Hope: A uniquely Canadian approach to suicide prevention Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being 2023 ; 8 ( 2 ): 107 – 109 Available from: journalcswb.ca/index.php/cswb/article/view/335 [Google Scholar]

- Maragha T , Donnelly L , Schuetz C , Bergmann H , Brondani M Mental health and wellness in Canadian dental schools: findings from a national study J Dent Educ 2022 ; 86 ( 1 ): 68 – 76 DOI: 10.1002/jdd.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins EK , McAuliffe C , Hirani S , Richardson C , Thomson KC , McGuinness L , et al. A portrait of the early and differential mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Findings from the first wave of a nationally representative cross-sectional survey Prev Med 2021 ; 145 : 106333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus Reid Institute . Worry, gratitude & boredom: As COVID-19 affects mental, financial health, who fares better; who is worse? Vancouver (BC) : : Angus Reid Institute ; ; 2020 . Available from: http://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2020.04.27_COVID-mental-health.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ylipaavalniemi J , Kivimäki M , Elovainio M , Virtanen M , Keltikangas-Järvinen L , Vahtera J Psychosocial work characteristics and incidence of newly diagnosed depression: a prospective cohort study of three different models Soc Sci Med 2005 ; 61 ( 1 ): 111 – 122 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R , Evans S , Gately C , Stordy J , Huxley P , Rogers A , et al. State–event relations among indicators of susceptibility to mental distress in Wythenshawe in the UK Soc Sci Med 2002 ; 55 ( 6 ): 921 – 935 doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00226-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner M , Radian E , Neiman A , Neiman R Declaring label preferences: Terminology research in mental health Can J Community Ment Health 2011 ; 30 ( 1 ): 121 – 137 Available from: cjcmh.com/doi/10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0009 [Google Scholar]

- Link BG , Phelan JC Conceptualizing stigma Annu Rev Sociol 2001 ; 27 ( 1 ): 363 – 385 [Google Scholar]

- Hoover K , Lockhart S , Callister C , Holtrop JS , Calcaterra SL Experiences of stigma in hospitals with addiction consultation services: A qualitative analysis of patients’ and hospital-based providers’ perspectives J Subst Abuse Treat 2022 ; 138 : 108708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart H Fighting stigma and discrimination is fighting for mental health Can Public Policy 2005 ; 31 ( Suppl ): 21 – 28 Available from: mdsc.ca/documents/Publications/Fighting%20Stigma%20and%20Discrimination%20is%20Fighting%20for%20Mental%20Health.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Poku OB , Eschliman EL , Entaile P , Rampa S , Mehta H , Tal D , et al. “It’s better if I die because even in the hospital, there is a stigma, people still gossip”: Gossip as a culturally shaped labelling process and its implications for HIV-related stigma in Botswana AIDS Behav 2023 ; 27 : 2535 – 2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The University of British Columbia. Suicide Awareness & Intervention Training (SAIT) [Internet]. n.d. Available from: wellbeing.ubc.ca/sait .

- University of British Columbia . Green folder: Student health and well-being . Vancouver (BC) : : UBC ; ; 2024 . Available from: allard.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/2025-04/2024.06_v2_Green%20Folder.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University . Identifying and responding to a student in distress: A guide for faculty and staff. London (ON) : : Western University ; ; 2021 . Available from: schulich.uwo.ca/learner_experience/wellness_resources/Identifying-a-Learner-In-Distress-Tips-for-Staff-and-Faculty.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Mental Health Support: Get Help [Internet]. ©2024. Available from: canada.ca/en/public-health/services/mental-health-services/mental-health-get-help.html .

- Webster S , Harrison L The multidisciplinary approach to mental health crisis management: an Australian example J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004 ; 11 ( 1 ): 21 – 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Buenaventura A , Chavez-Tuñon M , Castro-Ruiz C The mental health consequences of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in dentistry Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020 ; 14 ( 6 ): 803 – 807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton LJ , Mancl LA , Grembowski D , Armfield JM , Milgrom P Unmet dental need in community-dwelling adults with mental illness: results from the 2007 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey J Am Dent Assoc 2013 ; 144 ( 3 ): e16 - e23 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhar MA , Khokhar WA , Clifton AV , Tosh GE Oral health education (advice and training) for people with serious mental illness Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 ; 9 ( 9 ): CD008802. Available from: doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008802.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien A , Sethi F , Sith M , Bartlett A Public mental health crisis management and Section 136 of the Mental Health Act J Med Ethics 2017 ; 44 ( 5 ): 349 – 353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poornachitra P , Narayan V Management of dental patients with mental health problems in special care dentistry: a practical algorithm Cureus 2023 ; 15 ( 2 ): e34809 10.7759/cureus.34809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhar MA , Khokhar WA , Clifton AV , Tosh GE . Oral health advice (education and training) for people with serious mental illness [plain language summary] . © 2016 . Cochrane Library. Available from: cochrane.org/CD008802/SCHIZ_oral-heath-advice-education-and-training-people-serious-mental-illness . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Macnamara A , Mishu MP , Faisal MR , Islam M , Peckham E Improving oral health in people with severe mental illness (SMI): a systematic review PLoS ONE 2021 ; 16 ( 12 ): e0260766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faculty of Dentistry, The University of British Columbia . Emergency medical response plan . Vancouver (BC) : : UBC ; ; n.d. Available from: secure.dentistry.ubc.ca/intranet/operations_manual/documents/Section_IE_Emergency_Procedures.pdf?ver=Aug2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Dental Hygienists Association . Dental hygienists’ code of ethics . Ottawa (ON) : : CDHA ; ; 2023 . Available from: cdha.ca/pdfs/Profession/Resources/Code_of_Ethics_EN_web.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Dental Hygienists Association . Canadian competencies for baccalaureate dental hygiene programs . Ottawa (ON) : : CDHA ; ; 2015 . Available from: files.cdha.ca/profession/CCBDHP_report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Dental Hygienists Association . Canadian competencies for a baccalaureate oral health practitioner: Combining dental hygiene and dental therapy education . Ottawa (ON) : : CDHA ; ; 2018 . Available from: files.cdha.ca/education/OHP-Competencies.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau A , Walton JN , Morin S , Dagenais M Association of Canadian Faculties of Dentistry educational framework for the development of competency in dental programs J Dent Educ 2019 ; 83 ( 4 ): 464 – 473 10.21815/jde.019.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Dental Education Association, American Dental Hygienists’ Association . Graduate dental hygiene program aims and outcomes . Chicago (IL) : : ADEA and ADHA ; ; 2021 . Available from: adha.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Graduate_Dental_Hygiene_Program_Aims_and_Outcomes_March_2021.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of College & University Student Services and Canadian Mental Health Association . Post-secondary student mental health: Guide to a systemic approach . Vancouver (BC) : : CACUSS and CMHA ; ; 2013 . Available from: healthycampuses.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/The-National-Guide.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- CDA Staff How Canadian dentists are dealing with stress and uncertainty CDA Essentials 2021 ; 8 ( 1 ): 20 – 25 Available from: cda-adc.ca/en/services/essentials/2021/issue1/20/ [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP , Mortier P , Bruffaerts R , Alonso J , Benjet C , Cuijpers P , et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders J Abnorm Psychol 2018 ; 127 ( 7 ): 623 – 638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The World health report: 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope . Geneva : : WHO ; ; 2001 . Available from: apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42390 . [Google Scholar]

- Partido BB , Owen J Relationship between emotional intelligence, stress, and burnout among dental hygiene students J Dent Educ 2020 ; 84 ( 8 ): 864 – 870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragioti E , Li H , Tsitsas G , Lee KH , Choi J , Kim J , et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic J Med Virol 2022 ; 94 ( 5 ): 1935 – 1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell CA , Mills S , Goodfellow H , Cruz M A novel approach to supporting student mental health in the university classroom with therapy dogs Can J Community Ment Health 2022 ; 41 ( 2 ): 97 – 101 [Google Scholar]

- Pich J Oral health education (advice and training) for people with serious mental illness [review] Issues Ment Health Nurs 2019 ; 40 ( 10 ): 929 – 930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.