Abstract

We previously described the use of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy to achieve off-the-shelf, long-term in vivo T cell engagement for CD19+ B cell malignancies following a single dose by expressing a transgene encoding a bispecific diabody termed GP101. Here we describe the selection and development of a clinical lead construct, VNX-101, with enhanced safety and efficacy features. A single dose of the virus was effective at eliminating B cell malignancies in humanized mouse xenograft models. We observed a linear dose-dependent increase in serum concentrations of GP101 over a three-log range in mice, with transduction and serum levels lower in females than males. There were no concerning safety signals and the No Observed Adverse Event Level was determined to be >2.7E13 vg/kg. We also conducted a 12-week study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, in-life safety, gross pathology, and histopathology in hamadryas baboon monkeys. VNX-101 treatment was well tolerated with no significant changes in body weight or clinical signs reported. Collectively, these preclinical data support the efficacy and safety of VNX-101 as a potential AAV-based treatment for cancer. A phase 1/2 clinical trial of VNX-101 for relapsed or refractory B cell malignancies is under way.

Keywords: adeno-associated virus, AAV; bispecific T cell engager; CD19; B cell leukemia/lymphoma; toxicology; biodistribution

Graphical abstract

Currier and colleagues describe development of a clinical lead adeno-associated virus construct, VNX-101, with enhanced features to achieve off-the-shelf, long-term in vivo T cell engagement for CD19+ B cell malignancies. A single dose of VNX-101 was safe in mice and non-human primates (NHPs) and eliminated B cell malignancies in xenograft models.

Introduction

Outcomes for patients with relapsed B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and certain types of B cell lymphomas have been transformed by the advent of CD19-targeted immunotherapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells and the CD19×CD3 bispecific T cell engager, blinatumomab.1,2 CAR-T cells represent a breakthrough by demonstrating (1) the profound anti-tumor efficacy that can occur by redirecting autologous T cells to tumor-associated antigens, (2) the ability to adequately manage most adverse effects with supportive care (although sometimes intensive), and (3) the safety of long-term persistence of these cells and the accompanying normal B cell ablation. Blinatumomab also represents a breakthrough in demonstrating that infusion into the bloodstream of a small protein that links T cells to leukemia cells also demonstrates anti-leukemia efficacy and is well tolerated, though it elicits similar on-target side effects to those seen with CD19-directed CAR-T cells. Because of its short half-life, blinatumomab is given as a continuous intravenous (i.v.) infusion, which is cumbersome as patients are attached to i.v. equipment continuously for weeks at a time, require frequent drug replenishments, and are at increased risk for infection due to the constant i.v. access. As a result, blinatumomab is typically used only for a few 4-week infusion cycles separated by 1–2 weeks off as a bridge to other therapies.

We previously described the use of a single i.v. dose of adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy expressing a mimic of blinatumomab, termed GP101, to achieve off-the-shelf, long-term in vivo T cell engagement for CD19+ B cell leukemia/lymphoma.3 AAV infection primarily of hepatocytes enabled the liver to continuously secrete GP101 into the bloodstream for over a year. The approach thus combines the best attributes of CAR-T and blinatumomab into one drug product, being an off-the-shelf single dose with a long-lasting effect. Here we report the preclinical development of our lead construct, VNX-101, with enhanced safety and efficacy features. We selected our lead by comparing different constructs in vitro and in vivo to identify the one that elicited the highest amount of transgene expression, as this would minimize the vector dosing needed to achieve therapeutic effects. We also tested our lead construct for efficacy in several preclinical models of ALL, examined toxicity in mice and baboons, and identified the biodistribution and dose-response relationship, using these data to guide the clinical trial design.

Results

Design and selection of a lead construct for clinical translation

The overarching goal of this preclinical development program was to increase both the safety and efficacy of our original “tool” constructs (Figure 1A) by developing a lead construct with several molecular modifications. First, as recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) during our Interact meeting, we removed the sequence encoding the hexahistidine (6xHis) tag to reduce immunogenicity. Second, as also recommended by the FDA, we modified the downstream woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) based on a reported mutation (mut6)4 to prevent the expression of protein X from the human hepatitis B virus, due to a theoretical risk of causing cancer.5,6 The modified WPRE is abbreviated as MRE in the construct illustrations of Figure 1. Next, we replaced CpG sequences in the coding sequence with alternative codons, as these “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” can activate innate immunity when they are recognized by cellular toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9).7 Finally, we tested the workability of a tissue-specific promoter to limit expression of GP101 (the Gene Product of VNX-101, the CD19-targeted bispecific T cell-engaging diabody) to the liver. The schematics of the GP101-expressing plasmids are illustrated in Figure 1B. To determine if deleting CpG sequences would alter the transgene product levels of the GP101-expressing plasmids, we transfected primary hepatocytes with four transgene plasmids (Figure 1C). We quantified expression levels of GP101 using a commercially available T cell activation assay to compare the output of our samples against those obtained from known concentrations of blinatumomab, finding that the level of GP101 was unchanged with the avoidance of CpGs. Notably, we observed that the cells transfected with plasmids driven by the CMV—chicken β-actin—rabbit β-globin promoter/enhancer hybrid (CAG) produced the GP101 at levels 2-fold above the liver-specific promoter LP1.

Figure 1.

VNX-101 was developed and selected for safety and enhanced efficacy

(A) Illustration of the original “tool” constructs for the AAV expressing a secreted anti-CD19/anti-CD3 scFv-scFv diabody. (B) Illustration of the second generation AAV constructs. (C) Primary hepatocytes were transfected with four transgene plasmids to determine if sequences devoid of CpGs would alter the transgene product levels of the GP101-expressing plasmids. (D) NSGS mice were intravenously injected at day 0 with 5.0E12 vg/kg AAV viral vectors followed by GP101 serum level analysis at weeks 1, 3, 5, and 9 by ELISA (n = 5). (E) Blincyto was compared with the purified GP101 in a calcein-release killing assay. Relative fluorescence unit (RFU) was analyzed and plotted as function of the log of the dosage in ng/mL using the agonist vs. response-variable slope (4 parameter) analysis in Graph Pad Prism. Error bars represent standard deviation.

In addition to the safety modifications, we also sought to examine if vector structural modifications could enhance levels of GP101 by designing a self-complimentary variant of VNX-101. Due to size constraints with self-complimentary vectors that have only half of the insert capacity, we utilized a shorter promoter derived from elongation factor 1 alpha (EFS) and eliminated the mutant WPRE. To compare our constructs, we injected immunocompromised Nod-scid gamma SGM3 (NSGS) mice at day 0 with a single intravenous dose with 5.0e12 vector genomes per kilogram (vg/kg) of each recombinant AAV. We then collected serum from these animals at weeks 1, 3, 5, and 9 post-injection to analyze GP101 serum levels with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).8 Steady-state levels of GP101 expression were achieved by 3 weeks. Among the constructs, the single-stranded construct with the strongest promoter, AAVrh74CAG193-dCG-MRE, produced serum levels of GP101 10-fold higher than the other vector constructs (Figure 1D). Based on these findings, we selected it as our lead for further clinical development.

GP101 and blinatumomab are functionally interchangeable

We next sought to determine if GP101 was functionally interchangeable with equivalent doses of blinatumomab, as the wealth of pre-existing clinical data available for the latter could be informative for VNX-101 target dosing. We accomplished this using calcein-release cell killing assays to compare the effects of dose-for-dose levels of commercially available blinatumomab with purified GP101 protein.9 Figure 1E displays the dose-response curves for each agent, showing roughly equivalent half maximal effective concentration (EC50) values (0.076 ng/mL vs. 0.049 ng/mL for blinatumomab and GP101, respectively). These data are consistent with those found during assay development.9 Given that patients administered blinatumomab at the FDA-recommended dose of 15 μg/m2/d have serum levels of 651 ± 307 pg/mL,10 these equivalency data support setting a minimum threshold for a therapeutic level of GP101 in a future clinical trial at >300 pg/mL.

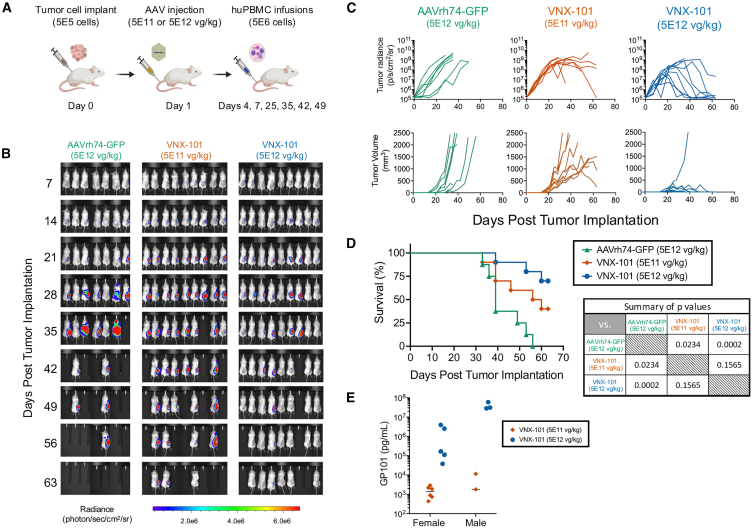

Anti-tumor efficacy of VNX-101 proof of concept in mice

We tested the lead construct VNX-101 in vivo by implanting CD19+ Raji-Luc/GFP lymphoma cells subcutaneously in the flank of NSGS immunodeficient mice that were subsequently given multiple intravenous infusions of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (huPBMCs). In this model, a single injection of VNX-101 at two different doses was effective at eliminating the tumor as measured by in vivo bioluminescence, caliper measurements, and animal survival (Figures 2A–2D). A dose response was observed with 5E12 vg/kg-treated mice having greater tumor response and survival benefit vs. mice treated at the 5E11 vg/kg dose level. We measured serum samples at endpoint sacrifice for GP101 levels (day 63) by ELISA and observed a dose-dependent increase in GP101 levels (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

A single injection of VNX-101 at two different doses was effective at eliminating the CD19-expressing Raji-Luc/GFP tumors

(A) Illustration of the treatment schema for the proof-of-concept experiment. 5E5 Raji-Luc/GFP cells were implanted on day 0 in the right flank of 6- to 8-week-old female NSG-SGM mice. On day 1, tumor-bearing mice were intravenously treated with VNX-101 (5E12 or 5E11 vg/kg) or AAVrh74-GFP control (5E12 vg/kg) by tail vein injection. On day 4, mice were transplanted with 5E6 huPBMCs. Additional doses of huPBMCs were administered on day 7 then weekly × 4 starting at day 25 (days 25, 35, 42, and 49) post tumor cell implantations. (B) Bioluminescent images from evaluation of study mice over time are shown. (C) Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence as well as measuring the tumor with calipers. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Statistical significance was determined using the log rank test (n = 7 for AAVrh74-GFP, n = 9 VNX-101[5E11 vg/kg] mice and VNX-101 [5E12 vg/kg] mice). (E) GP101 serum concentration was determined at the time of each mouse’s sacrifice by ELISA.

Bridging efficacy study of VNX-101 made with kanamycin plasmids

Due to European Medicines Agency (EMA) regulations that discourage the clinical use of AAV vectors that are generated using ampicillin-resistant plasmids,11 we produced a version of the clinical lead VNX-101 using kanamycin-resistant plasmids and administered it to NSGS mice bearing subcutaneous CD19+ Raji-Luc/GFP lymphoma tumors. VNX-101 treatment was well tolerated across the doses evaluated with no significant safety concerns observed prior to the onset of graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD), a known complication of administering human white cells into immunodeficient mice. A single i.v. injection at 5E11 vg/kg was effective at eliminating tumor as measured by in vivo bioluminescence, caliper measurements, and animal survival vs. the AAV8 EGFP control (Figures 3A–3D). Serum samples were analyzed at sacrifice for GP101 levels (day 77). Again, a persistent serum GP101 level at the time of sacrifice was observed (Figure 3E). Interestingly, the mouse in the VNX-101 treated group that has the highest bioluminescent tumor signal in Figure 3B (mouse in middle and labeled as C3B) is the mouse with the lowest GP101 production in Figure 3E, suggesting a correlation between serum levels and tumor response.

Figure 3.

A bridging study with VNX-101 manufactured with kanamycin-resistant plasmids confirmed VNX-101 efficacy in a CD19+ Raji-Luc/GFP tumor model in huPBMC humanized NSGS mice

(A) Illustration of the treatment schema for the bridging study. 5E5 Raji-Luc/GFP cells were implanted on day 0 in the right flank of 6 to 8-week-old female NSGS mice. On day 4, tumor-bearing mice were intravenously treated with VNX-101 (5E11 vg/kg) or AAV8-GFP control (5E12 vg/kg) by tail vein injection. On day 7, mice were transplanted with 5E6 huPBMCs. Additional doses of huPBMCs were administered on days 14, 21, 28, and 35 post tumor cell implantations. (B) Bioluminescent images from evaluation of study mice over time are shown. Percent of control represents percent reduction in total bioluminescence compared with AAV8-GFP control mice. (C) Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence as well as measuring the tumor with calipers. Mouse weights were followed as a metric to assess VNX-101 safety. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Statistical significance was determined using the log rank test (n = 5 for AAV8-GFP, n = 5 VNX-101 [5E11 vg/kg] mice). (E) GP101 serum concentration was determined at the time of each mouse’s sacrifice by ELISA.

Dose range-finding pharmacokinetic study in mice

We sought to determine the dose-response relationship between VNX-101 dose and the resulting steady-state serum levels of the secreted transgene product GP101 in NSGS mice. To accomplish this, we administered one of several ascending doses of VNX-101 (from 1.0E7 to 1.0E11 vg/kg) via i.v. injection to both male and female mice (n = 8/sex/group). Analysis of the injection and stability samples of the formulated VNX-101 dosages again confirmed that VNX-101 titer remained consistent during the injection procedure and that study cohorts received the appropriate doses (Figure S1). In-life assessments of the animals indicated that VNX-101 treatment was well tolerated across all doses evaluated with no observed safety concerns. All dose groups steadily gained weight during the study with no significant differences between males and females. We observed dose-dependent increases in GP101 levels in serum with minimal fluctuation; steady-state levels were reached by 4 weeks post-dose and persisted through 8 weeks post-dose (Figure 4). In both sexes, a 3-fold increase in dose led to an approximately 10-fold increase in GP101 level. VNX-101 administered at 1.0E7 vg/kg and 1.0E8 vg/kg resulted in GP101 levels below or near the lower limit of detection, whereas higher doses (1.0E10 vg/kg in males and 3.0E10 vg/kg in females) were associated with GP101 levels that were above the target threshold lower limit (300 pg/mL). At all doses, GP101 levels in males were approximately 10-fold higher than those in females, which is consistent with published studies indicating AAV vectors transduce murine liver 5- to 13-fold higher in males than females.12

Figure 4.

The dose response of VNX-101 to GP101 serum levels was consistent over a three-log range

Male and female NSGS mice were administered one of the ascending doses of VNX-101 (from 1.0E7 to 1.0E11 vg/kg) via IV injection. Blood was collected and serum isolated at 4, 6, and 8 weeks. GP101 serum levels were determined by ELISA; all sera collected from mice given 1.0E7 and 1.0E8 vg/kg were below the lower limit of quantification (200 pg/mL). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

IND-enabling efficacy studies in mice

Using a good manufacturing practice (GMP) engineering lot, we conducted two efficacy studies of a single i.v. injection of VNX-101 in human disseminated xenograft models of Raji (Burkitt’s B cell lymphoma) and Tanoue (B cell precursor leukemia) (Figure 5A). Post-analyses of the injectate confirmed that the VNX-101 titer remained consistent during the injection procedure and that both Raji-Luc/GFP and Tanoue-Luc/GFP study cohorts received the appropriate formulated doses (Figures S2 and S3, respectively). VNX-101 was well tolerated across dose levels with no observed safety concerns. Although we observed a mild graft-vs.-tumor allogeneic effect of huPBMCs alone or with a GFP-expressing control virus compared with VNX-101 alone, in both Raji-Luc/GFP and Tanoue-Luc/GFP models, a single dose of VNX-101 with huPBMCs prevented development of disseminated leukemia as measured by total-body photon quantification as compared with all control groups (Figures 5B and 5C). Likewise, animals treated with VNX-101 + huPBMCs achieved significantly greater duration of progression-free survival compared with control animals (AAVrh74-GFP + huPBMCs; p < 0.0001, log rank test) (Figure 5D). We noted that treatment groups that received huPBMCs regardless of other therapy tended to display less tumor burden than the control group given injections of PBS, which we attribute to a moderate graft vs. tumor allogeneic effect. To determine if this allogeneic effect was significant, we ran a second statistical analysis to compare mean time to animal removal from the study in each cohort and included mean time to cross the bioluminescent threshold of 1E6 photons, time to reach humane endpoint (GvHD) without crossing the threshold of 1E6 photons and study endpoint. The mean time for each cohort was compared using an ordinary one-way ANOVA. For Raji-LucGFP cell line, the VNX-101 + huPBMC treatment cohort with a mean time of 35.00 days was significant compared with the control treatments Diluent + huPBMCs, AAVrh74GFP + huPBMCs and VNX-101 + PBS with mean times of 14.93, 14.44, and 14.00 days, respectively (p < 0.0001 when VNX -101 + huPBMCs is compared with each control directly). For the Tanoue-LucGFP cell line, the VNX-101 + huPBMC treatment cohort with a mean time of 38.06 days was significant compared with the control treatments Diluent + huPBMCs, AAVrh74GFP + huPBMCs, and VNX-101 + PBS with means times of 19.69, 16.19, and 13.13 days, respectively (p < 0.0001 when VNX -101 + huPBMCs is compared with each control directly). The allogeneic response was minimal in the Raji-LucGFP cell line and did not reach significance. Interestingly, huPBMCs only gave a survival advantage in the Tanoue cell line when comparing Diluent + huPBMCs vs. VNX-101 + PBS (p = 0.0116). While this allogeneic effect appeared to slow disease progression, it was ultimately unable to resolve tumor burden by itself. In bone marrow, the control groups without huPBMCs showed high tumor burden of 40% (Raji) or 20% (Tanoue) of viable cells, whereas all groups including controls given huPBMCs had <2% (Figure S4). There were no differences in the weight gains between males and females given different doses of VNX-101 and between control and VNX-101-treated animals until progressive disease or GvHD was observed at approximately 4–5 weeks (Figure S5). Weight loss was minimal in the VNX-101 + PBS control cohort that did not receive huPBMCs or correlated with progressive disease observed by in vivo bioluminescence. The weight loss in the VNX-101-treated cohort receiving huPBMCs correlated with the observation of GvHD.

Figure 5.

A single intravenous dose of VNX-101 was effective at preventing leukemic cell dissemination in two different CD19-positive xenograft models

(A) Illustration of the treatment schema for the IND-enabling efficacy study. NSGS male and female mice were i.v. injected with a bolus of either 5E4 Raji-Luc/GFP or 1E5 Tanoue-Luc/GFP cells followed by weekly i.v. injections of huPBMCs starting on day 3 (a total of five injections). On day 4, animals received a single i.v. dose of vehicle (diluent), VNX-101 (males: 5.0E12 vg/kg; females: 2.5E13 vg/kg), or AAVrh74-GFP (5.0E12 vg/kg) (n = 8/sex/group). (B) Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence. (C) Bioluminescent images from evaluation of study mice over time are shown. The dashed lines between day 7 and day 14 indicate that only day 7 data were generated from 120-s exposure and data from day 14 and beyond were generated from a 60-s exposure for both cell lines. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Raji-Luc/GFP and Tanoue-Luc/GFP are plotted. Both curves combine responses of both male and female mice. Statistical significance was determined using the log rank test (Raji-Luc/GFP: n = 15 for Diluent + huPBMCS and n = 16 for AAVrh74-GFP + huPBMCS, VNX-101 + PBS, and VNX-101 + huPBMCs; Tanoue-Luc/GFP: n = 16 for Diluent + huPBMCS, AAVrh74-GFP + huPBMCs, VNX-101 + PBS, and VNX-101 + huPBMCs). Error bars in panel B represent geometric standard deviation.

Doses of VNX-101 at 2.5E13 vg/kg (females) and 5.0E12 vg/kg (males) produced GP101 serum levels in the 1E7 pg/mL range (Figure S6). An apparently nonspecific and poorly understood GP101 ELISA signal not seen in other studies was observed in control mice and thought to be due to the presence of huPBMCs and/or human tumor cells in these mice, in the range of 1E5 pg/mL. While the assay had been validated in NSGS mice, it was not validated in mice given tumor cells and multiple injections of huPBMCs. GP101 levels in mice receiving VNX-101 were approximately two logs higher (in the range of 1E7 to 1E8 pg/mL), consistent with those mice receiving a different vector from control mice. Overall, these data confirm that the VNX-101-treated mice received the right vector and achieved the projected GP101 levels.

We were also able to detect white blood cells in the circulation of mice given huPBMCs, with lymphocytes and neutrophils constituting the majority of cell populations present; these cell types were expectedly absent in the control mice given saline in lieu of huPBMCs (Figure S7). For unknown reasons, animals given huPBMCs with or without control virus or VNX-101 tended to show lower platelet counts than the PBS control group. We also observed that the experimental groups given huPBMCs showed slightly lower hemoglobin levels than those not given huPBMCs, with the notable exception of the VNX-101 + huPBMCs treatment group.

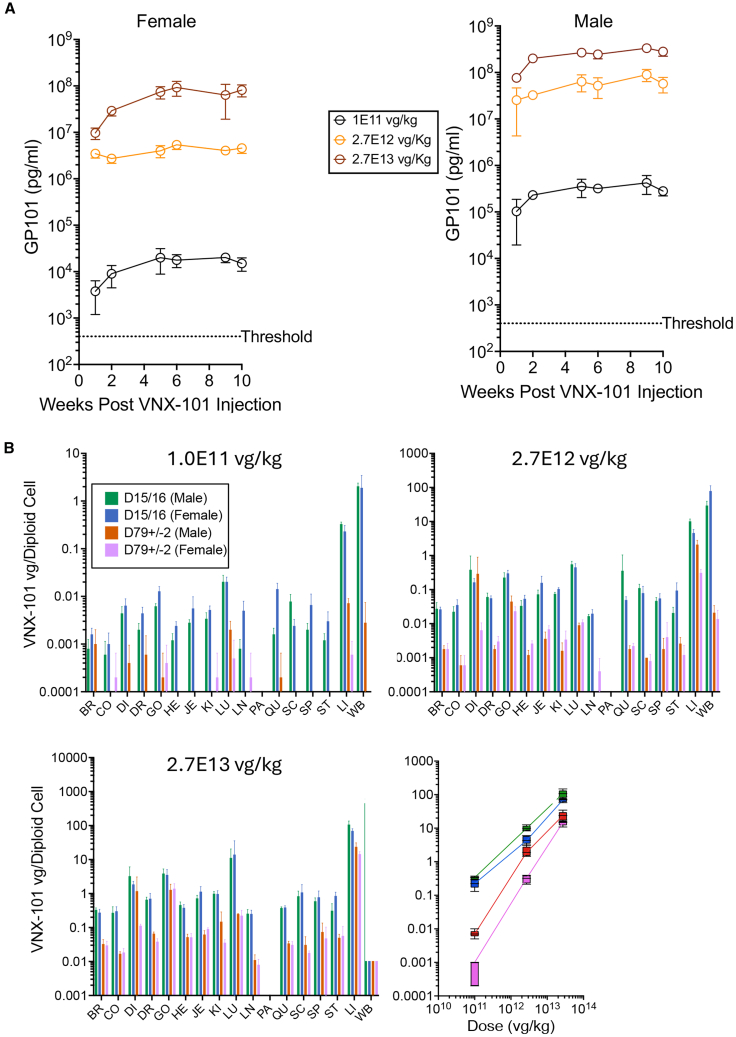

Toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution in mice

For these studies, we chose to use immunodeficient mice (NSG) that do not have B cells to emulate the scenario in humans of GP101 expression, which is expected to ablate normal B cells. We performed these studies in the absence of huPBMCs since those cause graft-vs.-host disease and would not enable toxicity studies beyond about 5 weeks due to animal deaths. Following a single bolus dose of VNX-101 at 1E11, 2.7E12, or 2.7E13 vg/kg in NSG male and female mice, we performed both stability and compatibility studies on the injection samples. Analysis of the injection and stability samples of the GLP toxicology formulated VNX-101 confirmed that VNX-101 titer remained consistent during the injection procedure and that study cohorts received the appropriate doses (Figures S8 and S9, respectively). GP101 serum levels increased with virus dose proportionally, with the lowest dose of 1.0E11 vg/kg producing and maintaining GP101 concentration above the target threshold lower limit in males and females (Figure 6A). Tissue analysis at necropsy showed that viral genomes were dose-dependently distributed and expressed most abundantly on days 15/16 in the blood and, to a lesser extent, in the liver and on day 79 ± 2 in the liver (Figure 6B). In the liver, there was a linear dose-response relationship between virus dose and genome copies per cell over the range of doses tested, with higher levels in males consistent with higher transduction and higher GP101 serum levels. At the lowest dose level of 1E11 vg/kg, which produced GP101 levels nearly 100-fold higher than the therapeutic threshold in females and 1,000-fold higher in males, there were 0.00075 ± 0.0005 vg/diploid cell in females and 0.00775 ± 0.0015 vg/diploid cell in males. There were no VNX-101-related changes in body weight or body weight gains during the study (Figure S10). Fluctuations in body weight and body weight gains, including those of statistical significance when compared with control group values, were within a range typically observed in this strain and age of mice undergoing similar procedures. Hematologic changes were considered non-adverse as the changes were minimal and/or due to a lack of VNX-101-related histopathologic correlates (Figure S11). VNX-101-related microscopic findings occurred in male animals on day 78 or 79 and were limited to the liver, in which hepatocellular cytoplasmic inclusions, considered non-adverse, were observed at ≥2.7 E12 vg/kg (Figure S12). Both the incidence and severity of this change were dose-dependent, being minimal at 2.7 E12 vg/kg and mild at 2.7 E13 vg/kg.

Figure 6.

VNX-101 was safe in mice at all doses tested under GLP conditions, with the majority of vector harbored in liver cells

(A) Male and female NSG mice were administered one of the ascending doses of VNX-101 (1.0E11, 2.7E12, and 2.7E13 vg/kg) via i.v. injection. Blood was collected and serum was isolated at weeks 4, 6, and 8. GP101 serum levels were determined by ELISA. (B) Tissue analysis of viral genomes was assessed by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) on days 15/16 and days 79 ± 2 in brain (BR), colon (CO), diaphram (DI), dosal root ganglion (DR), heart (HE), jejunum (JE), kidney (KI), lung (LU), lymph node (LN), pancreas (PA), spinal cord (SC), spleen (SP), stomach (ST) ovary/gonad (OV/GO), liver (LI), blood (WB). Error bars represent standard deviation.

The compatibility study with the diluted VNX-101 and components used to inject the NSG mice indicated no loss of VNX-101 during the dose preparation and intravenous administration. Both the low and high pre-filled syringe samples were comparable to their respective stock solutions (Table S1), as well as to the positive control, when accounting for sample dilution. The infectious titer results showed some variability (Table S2), possibly due to variability inherent in cell-based assays and testing being performed at a lower than typical sample concentration. Transgene expression was consistent for all samples tested (Table S3). The results support VNX-101 drug product compatibility with the product contact components, for VNX-101 concentrations from 1E10 vg/mL and 2.7E12 vg/mL and an exposure duration of up to 4 h.

Toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution in monkeys

We assessed the pharmacokinetics (PK), biodistribution, and safety characteristics of VNX-101 in naive hamadryas baboons at a single dose level to minimize the number of animals needed. We found that VNX-101 at a 2.7E12 vg/kg dose level was well tolerated, with no significant changes in body weight or adverse clinical signs reported (Figure 7A). We noted transient elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) post VNX-101 administration (Figure S13), which generally peaked at week 8 and decreased thereafter. Hematological studies demonstrated normal blood counts over the duration of the study (Figure S14). Peak GP101 levels were achieved in weeks 1–3 post-dose, persisting through to week 4 (Figure 7B). Levels subsequently disappeared due to the development of an inhibitor, likely an anti-GP101 antibody, as spiking of purified GP101 into serum from later timepoints was undetectable (Figure S15). GP101 levels were about 1,000-fold higher than the target threshold based on blinatumomab studies in humans, suggesting the minimally effective VNX-101 dose in humans will be far less than what we administered NHPs and the likelihood of toxicity such as hepatotoxicity also less. The highest GP101 level (1,472 ng/mL, week 1) was observed in an animal that also showed the highest transient elevation in ALT (134 U/L, week 7). We also noted that the GP101 concentration in this animal declined at weeks 2 and 3. This effect may be indicative of a stronger immune response to higher GP101 levels. Tissue analysis at necropsy showed that viral genomes were distributed and expressed most abundantly in the liver and blood (Figure 7C). Liver histology showed periportal inflammation (maximum grade 2 on a scale of 0–5) that was primarily lympho-histiocytic, but the lack of inclusion of any control animals precluded the ability to determine any test article related histopathologic changes.

Figure 7.

VNX-101 was safe in baboons under non-GLP conditions, with the majority of vector harbored in liver cells

(A) Four baboons (two male, two female) approximately 2 years of age and weighing between 5.9 and 6.8 kg were injected with 2.7E12 vg/kg of VNX-101 via i.v. infusion over 60 min. Baboon weight was measured weekly as a safety parameter. (B) Blood was collected, and serum was isolated weekly. GP101 serum levels were determined by ELISA. (C) Tissue analysis of viral genomes was assessed by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) at sacrifice on day 84. See Figure 6 legend for abbreviations.

Product contact in-use compatibility study for VNX-101 drug product

We proposed a phase 1/2 trial to evaluate the safety, dosing, and pharmacokinetics of VNX-101 in human patients. The design of this study calls for patients to receive a single intravenous infusion of VNX-101 at a range of 1.0E11 vg/kg to 2.7E12 vg/kg by means of a venous catheter using 20-cc syringe(s) or larger, as appropriate, with the infusion rate regulated by a syringe pump. Prior to initiating the trial, it was necessary for us to first conduct an in-use compatibility study. We performed this study using the minimum and maximum prepared dose concentrations (1.1 E10 vg/kg and 2.7E12 vg/kg) to confirm the minimum and maximum preparation volume and longest contact time of the product during preparation and administration to a patient. These evaluations by vector quantity (Table S4) and infectivity via TCID50 (Table S5) included both syringe compatibility time points and the 1-mL, 2-mL, and last milliliter time points for the delivery device compatibility. Each assay met all acceptance criteria. For the minimum dose study, infectious titer results varied across the samples tested from 5.22E6 to 4.31E7 TCID50/mL. While there was minor variation, the data did not present any trend indicating that the exposure to the product contact components had an impact on the product quality. Specifically, we observed the lowest infectious titer result from the 4-h syringe compatibility sample, and the highest infectious titer result from the next sample collected (the first sample from the coupled delivery device and syringe). The variability observed is likely due to inherent method variability and testing at a lower concentration than typical for the method (increasing the variability in results of the minimum dose samples). The positive control vector genome titer results for both clinical in-use positive controls (4.90E12 vg/mL for minimum dose and 5.75E12 vg/mL for maximum dose) were consistent with the lot release data for the VNX-101 drug product (4.56E12 vg/mL). Results from the minimum and maximum dose study also support the compatibility of VNX-101 with the drug delivery device as evaluated by ELISA. This evaluation included both syringe compatibility time points and the last milliliter time point for the delivery device compatibility (i.e., samples collected after >6 mL dispensed for minimum dose, and around 10 mL dispensed for maximum dose). GP101 expression was detected for all samples tested, with relative results ranging from 0.91 to 1.04 (Table S6).

Durable anti-tumor efficacy by VNX-101

To test the durability of the VNX-101 treatment, we administered one of the ascending doses of VNX-101 (from 0, 1.0E10, 3E10, and 1.0E11 vg/kg) via i.v. injection into female NSGS immunodeficient mice (n = 7–8/group) on day 0. On day 340 post VNX-101 dosing, we injected 1E6 CD19+ Raji-Luc/GFP lymphoma cells intravenously. Six days later, the mice received a single intravenous infusion of huPBMCs. In this model, a single injection of VNX-101 at each dose level was effective at markedly reducing widespread growth of the tumor cells as measured by in vivo bioluminescence (Figures 8A–8C) and animal survival (Figure 8D), consistent with these low virus doses being therapeutically active for a long duration.

Figure 8.

A single injection of VNX-101 at three different doses had a durable anti-tumor effect at 1 year post virus administration

(A) Illustration of the treatment schema for the VNX-101 durability study. On day 0, female NSGS immunodeficient mice were administered one of the ascending doses of VNX-101 (from 0, 1.0E10, 3E10, and 1.0E11 vg/kg) via i.v. injection (n = 7–8). On day 340 post VNX-101 dosing, 1E6 CD19+ Raji-Luc/GFP lymphoma cells were intravenously implanted. On day 346, the mice received a single intravenous infusion of huPBMCs. (B) Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence. (C) Bioluminescent images from evaluation of study mice over time are shown. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Statistical significance was determined using the log rank test (n = 8 for diluent and VNX-101 [1E11 vg/kg] mice, n = 7 mice for VNX-101 [1E10 vg/kg] and [3E10 vg/kg] mice).

Discussion

Here we describe the development of VNX-101, an off-the-shelf therapeutic designed to achieve long-term in vivo T cell engagement for the treatment of CD19+ B cell malignancies, from initial “tool” constructs through to the completion of IND-enabling studies on the lead vector, which we selected based on its highest expression in primary human liver cells and in mice. The lead construct was safe at all doses tested in mice and baboons. The lead construct was also effective in preventing human leukemia/lymphoma progression in immunodeficient mice supplemented with human immune cells.

For the toxicity studies in mice, we chose to use immunodeficient NSGS mice to emulate the scenario of absent B cells, which will occur in humans but not wild-type mice due to species specificities of the scFvs used. Similar ablation of normal B cells is seen with the use of CD19-directed CAR-T cells, and immunoglobulin levels in patients are maintained when needed by using monthly doses of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), sometimes for years.

Of note, the animal toxicology studies we conducted only gave us information regarding the safety of the vector transducing various organs and expressing secreted GP101, not the downstream safety of its bioactivity as it does not bind animal CD3 or CD19 (except chimpanzees).13 That said, the safety of blinatumomab in humans has been well described. As a proof of concept regarding the safety and efficacy of long-term blinatumomab exposure, Gupta et al. reported on an 11-year-old patient given blinatumomab cycles (4 weeks on, 1 week off) for 2 years because she did not tolerate conventional chemotherapy.14 At the time of the publication, the patient had tolerated the therapy well and remained in clinical remission for >25 months following therapy without any further anti-leukemia therapy. While it is likely to be years and might be lifelong, we do not yet know the durability of transgene expression in humans from VNX-101. The most analogous human experience to date is hemophilia gene therapy. For hemophilia B, factor IX levels in most patients last years but diminish slowly over time,15 whereas for hemophilia A factor VIII levels decrease in half approximately every 2 years.16

The major life-threatening side effects of T cell activation from blinatumomab or CAR-T cells are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which were not measured in our murine or baboon toxicity studies due to species specificity of binding. Both syndromes result from rapid immune cell activation. Our previously reported pharmacokinetic profile in mice following AAV administration showed a gentle rise in GP101 levels, requiring 2 weeks to reach steady state3 and the data we report herein with VNX-101 are consistent with a lag time to steady state levels of 2–4 weeks. Based on published pharmacokinetic data from AAV hemophilia gene therapy studies,17 it may take longer, on the order of 4–8 weeks, to reach steady-state levels in humans. We predict such a gradual rise in serum levels, and the concomitant slower engagement of T cells, will reduce the risk of CRS and ICANS, and may also enable higher serum levels to be tolerated than what were achieved with the maximum tolerable dose of blinatumomab (2,730 ± 985 pg/mL).10 Achieving higher levels than typically used in leukemia protocols may be important in some diseases, as modeling of dose response for blinatumomab suggests that higher serum levels should be targeted for lymphomas, possibly due to issues with penetration of both the diabody and T cells into lymph nodes and extranodal tissues.10

Two other strategies have been used to increase the half-life and/or reduce administration-related burdens of bispecifics. The first is the use of the subcutaneous route of administration, which avoids the need for continuous infusion. Subcutaneous blinatumomab still is somewhat burdensome as it requires 16 total shots in the first 4 weeks and 28 total for 2 cycles. This route also does not avoid adverse events (21.4% grade 3 CRS and 42.9% grade 3 ICANS), but it results in higher peak serum levels (nearly 10,000 pg/mL),18 which might make it more effective. Also, the troughs are nearly 10-fold less than peaks, creating periods of potentially less efficacy. The second is the use of full-length antibodies including the heavy chain Fc portion that prolongs the half-life. An example in the B cell malignancy space is the anti-CD3-anti-CD20 bispecific antibody glofitimab-gxbm, which is administered every 21 days after two step-up doses. Compared with scFv-scFv diabodies like GP101, the presence of the Fc completely changes the biodistribution and the levels needed to be effective, resulting in peaks and troughs of 48.5 nM and 2.68 nM, respectively. This high peak level is 8,700-fold above the expected effective molarity of GP101 (based on blinatumomab levels of 300 pg/mL = 5.55 pM) and may be the source of numerous laboratory abnormalities seen in patients. Thus, in comparison, our strategy requires relatively trace amounts of protein in the bloodstream, which is likely to be safer, and avoids the troughs that represent periods of low efficacy.

A potential downside of our approach is the inability to stop expression in the event of side effects. The major side effects, CRS and ICANS, are due to immune cell activation and typically occur with blinatumomab within the first few weeks. CAR-T cells show a similar timeline for side effects and, with the exception of a few recent examples, are also not able to be shut down after administration, sometimes persisting safely for years and even decades.19 In the event of side effects, patients are managed with supportive care until symptoms subside. Nevertheless, it may be possible in future iterations to include an inducible control of expression or off switch.

Because of the known risks of potentially life-threatening hepatotoxicity and systemic inflammation seen with high-dose AAVs,20 we sought to minimize the vector dose needed by maximizing the amount of transgene expression. Thus, we chose the lead construct with the strongest promoter, though we recognize the risk that it could lead to increased immunogenicity as it has more CpGs than shorter promoters. With that in mind, we also attempted to reduce the vector’s overall immunogenicity by eliminating all 109 CpGs from the transgene coding sequence, though we left the CpGs of the promoter and downstream regulatory elements intact so as not to risk reducing transgene mRNA levels. Accordingly, we were able to achieve steady-state serum levels of GP101 above 300 pg/mL (equivalent to human serum levels of blinatumomab in patients given the FDA-recommended dose of 15 μg/kg/d, which was 651 ± 307 pg/mL) using only 3.0E9 vg/kg in male and 1.0E10 vg/kg in female mice. If we encounter issues with immunogenicity and short-lived expression during clinical translation, we may be able to address the issue by selectively converting only the immunostimulatory CpGs (based on the surrounding nucleotides) in the promoter to neutral CpGs and even eliminate the modified WPRE without compromising expression, as recently demonstrated in another AAV program.21

In our dose range-finding study, we noted that every 3-fold increase in dose resulted in approximately 10-fold increase in serum levels in both sexes, with the absolute level being approximately 10-fold higher in males than females at the same dose. This difference between the sexes is consistent with what has been previously described for AAV in mice,12 which is one of the reasons we tested both sexes in our baboon study. We did not observe a difference between sexes in baboons, suggesting the difference may be a phenomenon specific to mice.

Allometric scaling for different-sized species, in which higher doses per kilogram are required in larger animal models or humans to achieve similar effects as in smaller animal models, is a well-known issue for AAV gene therapy. Although some investigators have tried to model allometric scaling mathematically,22,23 others have suggested there are too many variables to make reliable predictions.24 Comparing our experience in two different species using the same dose of 2.7E12 vg/kg, baboons showed a serum level peak of mid-E5 pg/mL, whereas female and male mice showed mid-E6 and mid-E7 pg/mL, respectively. Thus, the allometric scaling effect resulted in a difference in serum levels of ∼10-fold between female mice and baboons and ∼100-fold between male mice and baboons. Given that the dose-response relationship we identified in our dose range-finding study suggests a 3-fold increase in vector dose results in a 10-fold increase in serum level, we would predict that multiplying the female mouse dose by 3-fold and the male mouse dose by 9-fold would be sufficient to reach the 300 pg/mL threshold in baboons, which would be 3E10 vg/kg or 2.7E10 vg/kg, respectively. Because the baboons in our study weighed ∼6 kg (∼200-fold more than the mice), the allometric scaling from baboons to a 70-kg human adult (∼11-fold) will likely be less pronounced than from mice to baboons. As such, we selected 1E11 vg/kg (∼3-fold above the predicted therapeutic dose in baboons) as our starting dose for the human clinical trial. Because subjects in AAV-based gene therapy trials will likely only get one chance at a dose, it is important to choose a starting dose that will likely be efficacious rather than the traditionally very low doses given in conventional oncology trials.

The biodistribution data enable us to estimate the percentage of hepatocytes that need to be transduced in order to produce sufficient amounts of GP101 to reach therapeutic serum levels. In our mouse virus genome biodistribution study, the lowest dose we tested was 1E11 vg/kg, which resulted in GP101 levels of approximately 2E4 pg/mL in females, approximately 100-fold above the therapeutic target threshold of 300 pg/mL. At that dose, we found there were 0.0075 ± 0.0005 vg/diploid genome, which is 1 in 1,333 hepatocytes. Thus, we will likely need to transduce far less than 1 in 1,000 cells to achieve therapeutic efficacy, making hepatotoxicity unlikely.

The formation of an inhibitor in the baboons that neutralized expression in all animals by 6 weeks raises the question of the development of anti-drug antibodies in humans. We did not specifically measure anti-GP101 antibodies so we do not know the timing of their onset in the baboons. We also did not seek to detect GP101 in the VNX-101 virus prep to determine if we co-delivered any protein that could have been immunogenic. Certainly if anti-drug antibodies were to occur in human patients and result in short-lived expression of GP101, then therapy with VNX-101 would likely be ineffective, as the goal is to apply long-term pressure on malignant B cells. It would also preclude further use of blinatumomab in that patient. That said, a retrospective study of monoclonal antibodies showed there is only a 59% concordance of anti-drug antibodies between non-human primates and humans.25 Furthermore, because the GP101 mechanism of action not only destroys malignant human B cells but also eliminates normal human B cells, the development of anti-GP101 antibodies in humans is extremely unlikely. In fact, fewer than 1% of patients treated with blinatumomab developed such antibodies.26 This situation was not mimicked in baboons because GP101 is not bioactive in that species. It is also possible, however, that the slow rise in GP101 levels following VNX-101 administration in humans might provide a window of opportunity for the development of anti-GP101 neutralizing antibodies before normal B cells are depleted. Such a potential complication could be mitigated by pretreatment with blinatumomab prior to VNX-101. Assuming that does not occur, we also predict that the long-term elimination of normal B cells with VNX-101 will prevent the formation of anti-AAV antibodies, which might enable redosing if desired (note that we will only be able to test this hypothesis in humans due to species differences, as GP101 is not bioactive in animals other than chimpanzees). A future use of VNX-101 could also therefore be to enable redosing for other AAV gene therapies, providing the trade-off of potentially long-term dependency on IVIG infusions is considered in the risk-benefit analysis. A further advantage might be less risk for complications of AAV gene therapy such as thrombotic microangiopathy, which has been shown to result in part from anti-AAV antibodies.27

Finally, we point out that recent experience suggests that blinatumomab may be able to substitute for intensive chemotherapy, as determined in a real-world experience in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients who were unable to tolerate or were resistant to conventional chemotherapy.28 We can thus envision a future in which patients are put into remission with conventional chemotherapy and given a single dose of VNX-101 as adjuvant therapy, which provides the required long-term pressure to eventually eliminate all leukemia cells, and enables avoidance of further chemotherapy and its attendant short- and long-term side effects.

Taken together, our preclinical data support the efficacy and safety of VNX-101 as a potential AAV-based treatment for CD19+ B cell malignancies. Because the treatment also affects normal B cells, this therapy also might be useful for treating autoimmune diseases. A phase 1/2 clinical trial of VNX-101 for relapsed or refractory B cell malignancies is open for accrual (NCT06533579).

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Raji-Luc/GFP cells were grown as previously described.3 Tanoue cells were a kind gift from the Ruoning Wang Lab (Nationwide Children’s Hospital Abigail Wexner Research Institute). Raji-Luc/GFP, Tanoue, and Tanoue-Luc/GFP cells were all maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (10 mg/mL). The Jurkat NFAT-Luc reporter cell line was purchased from BPS Bioscience (San Diego, CA). All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat genotyping and confirmed negative for mycoplasma by IDEXX Bioanalytics (Columbia, MO). Tall-104 and Raji cells were purchased from ATCC (Gaithersburg, MD) and cultured as described by Weiss et al.9 Primary human hepatocytes were purchased from Lonza Bioscience (Wallkersville, MD). Tanoue-Luc/GFP cells were created by transducing Tanoue leukemia cells with cytomegalovirus-driven Firefly luciferase-GFP lentivirus (Cellomics Technology, Halethorpe, MD) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. In short, Tanoue cells were incubated with lentivirus (multiplicity of infection = 1 lentiviral particle per Tanoue cell) and polybrene (8 μg/mL) for 24 h. The transduced cells were then pelleted and resuspended in fresh complete RPMI 1640 medium and allowed to grow for an additional 72 h before the addition of puromycin (1 μg/mL) to aid in the selection of luciferase and GFP-positive cells. Tanoue-Luc/GFP cells were cultured and expanded in puromycin-containing media until passage number 5, whereupon frozen stocks were created to be used in this study.

Plasmid construction and rAAV viral vector production

DNA sequences for the CD19 and CD3 single-chain antibody components featured in this study were assembled with SnapGene software (GSL Biotech LLC, San Diego, CA) and human codon-optimized; alternative codons were hand selected to eliminate CG dinucleotides in designated constructs. Recombinant AAV vectors used to express the GFP control were packaged into either AAV8 or AAVrh74 backbones and titrated by VectorBuilder Inc. (Chicago, IL). For the POC, bridging, IND-enabling efficacy studies and the DRFS and GLP single-dose pharmacokinetic studies, AAV assembly plasmids were purified using good manufacturing practice (GMP) by a contracted research organization (CRO) and the recombinant AAV vector used to express the lead GP101 construct was packaged by another CRO. Aliquots of plasmid DNA or rAAV were stored at −20°C or −80°C respectively.

ELISA for GP101

We developed an ELISA to measure GP101 serum levels.8 Briefly, purified CD3 epsilon and delta proteins (ACRO Biosystems, Newark, DE) were coated onto wells of a white ELISA plate, washed, then blocked with a casein solution. Mouse and baboon serum samples containing GP101 were diluted to reach within the linear range of the respective standard curves. With incubation and washings between each step, the anti-CD19 side of GP101 was then bound with CD19-mouse Fc reagent (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-anti-mouse Fc (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) using QuantaRed substrate (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA).

Potency assay

Purified GP101 and Blincyto were evaluated in a cell T cell killing assay.9 Target Raji cells were incubated with calcein AM and washed. Cytotoxic TALL-104 cells (6E4 cells) and Raji cells (2E4 cells) were co-incubated with a varying concentration of GP101 or Blincyto (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) for 2.5 h. Cells are centrifuged and the calcein released from dead cells measured by fluorescence.

In vitro comparison of αCD19xαCD3 AAV constructs

To compare αCD19-αCD3 diabody-expressing plasmids, 2E5 primary hepatocytes were seeded in 48-well plates for 4 h. After replacing supernatant with maintenance media supplied by Lonza Biosciences (Walkersville, MD), hepatocytes were cultured for 48 h and then transfected with 1.0 μg of indicated GP101-expressing plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Supernatants were collected at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Then the concentration of the GP101 in hepatocyte supernatants was quantitated using the T cell Activation Bioassay (Promega, Madison, WI) in accordance with the manufacturer’s listed protocol. Briefly, cell supernatants were diluted in RPMI 1640 medium, and 25 μL of these samples were plated in white opaque 96-well plates. Serial dilutions of known concentrations of blinatumomab purchased from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA) as 35-μg injection vials from the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Research Pharmacy were also prepared and plated to serve as a standard curve. Diluted supernatants or a media negative control was added to the coculture of Raji cells and Jurkat TCR/CD3 effector cells in a 96-well plate. After 6 h of coculture at 37°C, 50 μL of Bio-Glo Luciferase Assay reagent was added to each well, and total luminescence was recorded on a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader (Winooski, VT) using an integration time of 1 s. Data were analyzed using Prism 9 software to construct a four-parameter logistic curve and interpolate the unknown serum GP101 concentrations against the blinatumomab standards.

Animals

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg(CMV-IL3,CSF2,KITLG)1Eav/MloySzJ (013062, NSG-SGM3 or NSGS) mice were procured from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred in-house. All animal experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the regulations of the local institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) where the experiments were conducted, either the IACUC at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Charles River Laboratories (mouse toxicology study), or the Mannheimer Foundation (baboon monkey study). Male and female NOD.Cg- Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (005557, NSG) mice 8–12 weeks of age were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Naive male and female baboons (Papio hamadryas) approximately 2 years of age were supplied by the Mannheimer Foundation, Inc. (Homestead, FL). During all animal studies, the care and use of animals were conducted with guidance from the guidelines of the USA National Research Council.

In vivo comparison of GP101 expressing AAV vector constructs

On day 0, NSGS mice were intravenously injected with AAVrh74CAG193-dCG-MRE, AAVrh74LP1p/K193-dCG-MRE, AAVrh74scEFSp/K193-dCG-MRE, or AAVrh74scEFSp/K193-MRE at 5.0e12 vg/kg (n = 5). Blood was collected in microtainer blood collection serum separator tubes with clot activator gel (Becton, Dickinson Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and allowed to clot for 20 min. Collection tubes containing blood were centrifuged at >2,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The serum (supernatant) was collected and stored at <−20°C. Serum samples were then thawed and GP101 serum levels analyzed at weeks 1, 3, 5, and 9 by ELISA.

Proof-of-concept efficacy study

For proof of concept in an early-stage tumor model, 5E5 Raji-Luc/GFP cells were implanted on day 0 in the right flank of 6- to 8-week-old female NSGS mice. On day 1, assigned cohorts of tumor-bearing mice were intravenously treated with VNX-101 (5E12 or 5E11 vg/KG) or AAVrh74-GFP control (5E12 vg/kg) by tail vein injection. On day 4, designated cohorts were transplanted with 5E6 huPBMCs from CGT Global (Folsom, CA). Additional doses of huPBMCs were administered on days 7, 25, 35, 42, and 49 post tumor cell implantations. Mice were followed for tumor growth and survival until a humane endpoint was reached. Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence (see below) as well as measuring the tumor with calipers and calculating the tumor volume using the formula length × width2 × π/6. Blood was collected at endpoint by retro-orbital bleed and analyzed for GP101 serum concentration using the ELISA for GP101.

Bridging efficacy study

For an established tumor model in the bridging study, 5E5 Raji-Luc/GFP cells were implanted on day 0 in the right flank of 6- to 8-week-old female NSGS mice. On day 4, assigned cohorts of tumor-bearing mice were intravenously treated with VNX-101 (5E12 or 5E11 vg/kg) or AAV8e-GFP control (5E12 vg/kg) by tail vein injection. On day 7, designated cohorts were transplanted with 5E6 huPBMCs from CGT Global (Folsom, CA). Additional doses of huPBMCs were administered on days 14, 21, 28, and 35 post tumor cell implantations. Mice were followed for tumor growth and survival until a humane endpoint was reached. Tumor growth and GP101 serum concentration levels were determined as described above.

IND-enabling efficacy study

To test the anti-tumor potential of VNX-101 in metastatic models, NSGS male and female mice were i.v. injected with a bolus of either 5E4 Raji-Luc/GFP or 1E5 Tanoue-Luc/GFP cells followed by weekly i.v. injections of huPBMCs from CGT Global (Folsom, CA) starting on day 3 (a total of five injections). For these studies, huPBMCs from a male (CGT Global Lot 2108050043) were chosen to avoid HY antigen response as Tanoue and Raji were known to be derived from male patients. On day 4, animals received a single i.v. dose of vehicle (diluent), VNX-101 (males: 5.0E12 vg/kg; females: 2.5E13 vg/kg), or AAVrh74-GFP (5.0E12 vg/kg) (n = 8/sex/group). Mice were followed for tumor growth and survival until a humane endpoint was reached. Tumor growth was determined by measuring tumor bioluminescence (see below). Blood was collected at endpoint by retro-orbital bleed and analyzed for GP101 serum concentration using the ELISA for GP101.

Dose range-finding pharmacokinetic study in mice

To perform the dose range-finding pharmacokinetic study, a single bolus dose of VNX-101 (Engineering Grade Test Material) from 1.0E7 to 1.0E11 vg/kg via i.v. injection was administered to both male and female mice (n = 8/sex/group). Blood was collected and serum was isolated at 4, 6 and 8 weeks. GP101 levels were analyzed by the ELISA as previously described.

Single-dose toxicity study in mice

To analyze the pharmacokinetics of VNX-101 mice, a single bolus dose of VNX-101 (Engineering Grade Test Material) at 1E11, 2.7E12, or 2.7E13 vg/kg was administered to both male and female NSG mice. The following parameters and endpoints were evaluated as part of a GLP toxicology study: mortality, clinical observations, body weights, clinical pathology parameters (hematology and clinical chemistry), pharmacokinetics, PCR analysis (blood and tissues), and macroscopic and microscopic examinations.

Pharmacokinetic study in non-human primates

To analyze the pharmacokinetics of VNX-101 in primates, four hamadryas baboons (two male, two female) approximately 2 years of age and weighing between 5.9 and 6.8 kg were injected with 2.7E12 vg/kg of VNX-101 via i.v. infusion over 60 min. General life assessments included daily cage side observations, detailed clinical observations as needed, weekly body weights, weekly blood collections for complete blood counts, GP101 serum concentration analysis, and serum chemistry and scheduled euthanasia with full necropsy at 12 weeks. The necropsy included selected organ weights, standard tissue cryopreservation for RNA/DNA isolation with subsequent digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) analysis for VNX-101 biodistribution and standard tissue formalin fixation with processing for H&E staining and pathology evaluation.

In vivo bioluminescent imaging in mice

Bioluminescent imaging was initiated 7 days after implantation of tumor cells and conducted weekly thereafter. Each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μL (3 mg) of Xenolight Rediject D-luciferin (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and maintained under isoflurane gas anesthesia for 5 min before imaging. Bioluminescent images were obtained using the Xenogen IVIS Spectrum (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). Quantification of tumor bioluminescent activity was performed with Living Image 4.4 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) by taking an auto-exposure and recording the total photons in a set region of interest that was kept consistent throughout the duration of study. Bioluminescent activity is presented as photons per second per cm2 per steradian (p/s/cm2/sr). Additional sets of images were taken at 60-s exposures for display purposes in their respective figures.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software 9.0.2 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and corresponding log rank Mantel-Cox tests were used to evaluate the statistical differences between groups in efficacy studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carla Waddell, Haley Wrightnour, Miranda Menke, and Erin Grove for their expert care of the animals and Natalie Rohan and Allison Lowry for their technical support. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (numbers P30 CA016058 and U54-CA232561 [T.P.C.] and 1R01CA278995-01A1 [T.P.C.]) and Cancer Free Kids Pediatric Cancer Research Alliance (B.H. and T.P.C.) and via a sponsored research agreement with Vironexis Biotherapeutics, Inc. (T.P.C.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.A.C., A.R., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., A.M.G., D.D., D.H., A.K., S.V., B.K., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Methodology: M.A.C., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., A.M.G., D.D., D.H., A.K., P.M., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Investigation: M.A.C., A.R., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., A.M.G., S.N.P., A.S.V., D.D., D.H., A.K., P.M., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Visualization: M.A.C., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., D.D., D.H., A.K., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Funding acquisition: A.R., S.V., B.K., and T.P.C. Project administration: M.A.C., A.R., D.D., A.K., S.V., B.K., P.M., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Supervision: M.A.C., A.R., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., D.D., A.K., S.V., B.K., P.M., P.R., T.L.W., and T.P.C. Writing – original draft: M.A.C. and T.P.C.. Writing – review & editing: M.A.C., A.R., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., A.M.G., S.N.P., A.S.V., D.D., D.H., A.K., S.V., B.K., P.M., P.R., T.J., T.L.W., and T.P.C.

Declaration of interests

The following authors have a financial conflict of interest due to their ownership in or employment by Vironexis Biotherapeutics, Inc.: M.A.C., A.R., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., D.D., D.H., A.K., S.V., B.K., and T.P.C. The following authors are co-inventors on patent application 62/808,264 that is related to this work: M.A.C., B.H., P.-Y.W., C.-Y.C., and T.P.C.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2025.101541.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Haydu J.E., Abramson J.S. The rules of T-cell engagement: current state of CAR T cells and bispecific antibodies in B-cell lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2024;8:4700–4710. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Hadidi S., Heslop H.E., Brenner M.K., Suzuki M. Bispecific antibodies and autologous chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies for treatment of hematological malignancies. Mol. Ther. 2024;32:2444–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cripe T.P., Hutzen B., Currier M.A., Chen C.Y., Glaspell A.M., Sullivan G.C., Hurley J.M., Deighen M.R., Venkataramany A.S., Mo X., et al. Leveraging gene therapy to achieve long-term continuous or controllable expression of biotherapeutics. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanta-Boussif M.A., Charrier S., Brice-Ouzet A., Martin S., Opolon P., Thrasher A.J., Hope T.J., Galy A. Validation of a mutated PRE sequence allowing high and sustained transgene expression while abrogating WHV-X protein synthesis: application to the gene therapy of WAS. Gene Ther. 2009;16:605–619. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard M.J., Schneider R.J. The enigmatic X gene of hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:12725–12734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12725-12734.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsman S.M., Mitrophanous K., Olsen J.C. Potential oncogene activity of the woodchuck hepatitis post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) Gene Ther. 2005;12:3–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright J.F. Quantification of CpG Motifs in rAAV Genomes: Avoiding the Toll. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:1756–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson T., Ahnoud A., DiNello B., Ralph P., Cripe T., Wang P., Weiss T. Development of a Pharmacokinetic (PK) Mouse Serum GLP ELISA for an Anti–CD19–AntiCD3 Diabody. bioRxiv. 2025 doi: 10.1101/2025.03.19.644217. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss T., Paniagua J., Johnson T., Cripe T.P., Ralph P. Cell-Based Potency Assay for Anti-CD3-Anti-CD19 Diabody. bioRxiv. 2025 doi: 10.1101/2025.04.15.648836. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hijazi Y., Klinger M., Kratzer A., Wu B., Baeuerle P.A., Kufer P., Wolf A., Nagorsen D., Zhu M. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Relationship of Blinatumomab in Patients with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;13:55–64. doi: 10.2174/1574884713666180518102514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EMA_Committee_for_Advanced_Therapies Reflection paper on design modifications of gene therapy medicinal products during development. 2012. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-design-modifications-gene-therapy-medicinal-products-during-development_en.pdf

- 12.Davidoff A.M., Ng C.Y.C., Zhou J., Spence Y., Nathwani A.C. Sex significantly influences transduction of murine liver by recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors through an androgen-dependent pathway. Blood. 2003;102:480–488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlereth B., Quadt C., Dreier T., Kufer P., Lorenczewski G., Prang N., Brandl C., Lippold S., Cobb K., Brasky K., et al. T-cell activation and B-cell depletion in chimpanzees treated with a bispecific anti-CD19/anti-CD3 single-chain antibody construct. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006;55:503–514. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S., Casey J., Lasky J. Case Report: Blinatumomab as upfront consolidation and maintenance therapy in a pediatric patient with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1246924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasko J.E.J., Samelson-Jones B.J., George L.A., Giermasz A., Ducore J.M., Teitel J.M., McGuinn C.E., High K.A., de Jong Y.P., Chhabra A., et al. Fidanacogene Elaparvovec for Hemophilia B - A Multiyear Follow-up Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025;392:1508–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2307159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George L.A. Hemophilia A Gene Therapy - Some Answers, More Questions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;388:761–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2212347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George L.A., Sullivan S.K., Giermasz A., Rasko J.E.J., Samelson-Jones B.J., Ducore J., Cuker A., Sullivan L.M., Majumdar S., Teitel J., et al. Hemophilia B Gene Therapy with a High-Specific-Activity Factor IX Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2215–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabbour E., Zugmaier G., Agrawal V., Martínez-Sánchez P., Rifón Roca J.J., Cassaday R.D., Böll B., Rijneveld A., Abdul-Hay M., Huguet F., et al. Single agent subcutaneous blinatumomab for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2024;99:586–595. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C.H., Sharma S., Heczey A.A., Woods M.L., Steffin D.H.M., Louis C.U., Grilley B.J., Thakkar S.G., Wu M., Wang T., et al. Long-term outcomes of GD2-directed CAR-T cell therapy in patients with neuroblastoma. Nat. Med. 2025;31:1125–1129. doi: 10.1038/s41591-025-03513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assaf B.T. Systemic Toxicity of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Therapy Vectors. Toxicol. Pathol. 2024;52:523–530. doi: 10.1177/01926233241298892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta N., Gilbert R., Chahal P.S., Moreno M.J., Nassoury N., Coulombe N., Gingras R., Mullick A., Drouin S., Sasseville M., et al. Optimization of adeno-associated viral (AAV) gene therapies vectors for balancing efficacy, longevity and safety for clinical application. Gene Ther. 2025;32:197–210. doi: 10.1038/s41434-025-00524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang F., Wong H., Ng C.M. Rational Clinical Dose Selection of Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Therapy Based on Allometric Principles. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;110:803–807. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burr A., Erickson P., Bento R., Shama K., Roth C., Parekkadan B. Allometric-like scaling of AAV gene therapy for systemic protein delivery. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022;27:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aksenov S., Roberts J.C., Mugundu G., Mueller K.T., Bhattacharya I., Tortorici M.A. Current and Next Steps Toward Prediction of Human Dose for Gene Therapy Using Translational Dose-Response Studies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;110:1176–1179. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Meer P.J.K., Kooijman M., Brinks V., Gispen-de Wied C.C., Silva-Lima B., Moors E.H.M., Schellekens H. Immunogenicity of mAbs in non-human primates during nonclinical safety assessment. mAbs. 2013;5:810–816. doi: 10.4161/mabs.25234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu M., Wu B., Brandl C., Johnson J., Wolf A., Chow A., Doshi S. Blinatumomab, a Bispecific T-cell Engager (BiTE((R))) for CD-19 Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy: Clinical Pharmacology and Its Implications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:1271–1288. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salabarria S.M., Corti M., Coleman K.E., Wichman M.B., Berthy J.A., D'Souza P., Tifft C.J., Herzog R.W., Elder M.E., Shoemaker L.R., et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy following systemic AAV administration is dependent on anti-capsid antibodies. J. Clin. Investig. 2024;134 doi: 10.1172/JCI173510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodder A., Mishra A.K., Enshaei A., Baird S., Elbeshlawi I., Bonney D., Clesham K., Cummins M., Vedi A., Gibson B., et al. Blinatumomab for First-Line Treatment of Children and Young Persons With B-ALL. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024;42:907–914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.