Abstract

This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive review of the techniques and challenges associated with applying upper extremity casts in pediatric patients. The chapter, along with its accompanying figures and video clips, serves as an introductory guide to pediatric orthopaedic cast application for trainees. Generally, casts are used to preserve appropriate alignment rather than to create improved alignment. In cases of nondisplaced fractures or those with acceptable alignment, the role of the cast is to maintain that alignment until healing occurs. For fractures with unacceptable alignment, reducing them to an acceptable position is necessary while the cast is utilized to maintain proper alignment. For challenging fractures that are difficult to keep aligned, have displaced intraarticular components, or are length-unstable, surgical intervention is recommended, followed by casting for immobilization after surgery. This chapter reviews the indications, application, techniques, and pitfalls of short arm, thumb spica, mitten, ulnar gutter, long arm, and hanging arm casts.

Key Concepts

-

(1)

The cast index is a valuable measure that impacts the rates of loss of reduction in distal radius fractures.

-

(2)

Molds are important not only for maintaining fracture reduction but also for keeping the cast in position and preventing slippage.

-

(3)

Along with using a cast saw to split fiberglass casts, a cast splitter should be employed to ensure proper bivalving.

Keywords: Short arm cast, Thumb spica cast, Mitten cast, Long arm cast

Introduction

The field of orthopaedic trauma management has evolved over the past several decades, with significant advancements in techniques for open reduction and instrumentation for stable fixation. As a result of these developments, the reliance on external devices such as traction, splints, and casts for fracture manipulation and stabilization has diminished. The routine practice of extended skeletal traction or spica cast application for adult femur fractures would now be considered an ancient relic. Similarly, tibial shaft fractures in adults are nearly universally treated with rigid intramedullary fixation, rather than older methods such as emergency room reduction, long leg cast application, and months of patella-tendon-bearing or short leg cast use. While upper extremity splints remain somewhat common in adult trauma, they are often used temporarily until definitive internal fixation can be performed, preferring early range of motion over long periods of immobilization.

In parallel with these advancements in fracture management, significant changes have taken place in medical education and health care service delivery. Due to increased subspecialization, many orthopaedic surgeons now manage less trauma cases, seldom apply casts, and even less frequently teach residents the safe and effective use of these techniques. As health care reimbursement models evolve, orthopaedic surgeons are increasingly focused on tasks that require their unique expertise—primarily surgical intervention—while other aspects of patient care are delegated to advanced practitioners or allied health professionals. In many emergency departments and outpatient clinics, definitive cast applications are performed by cast technicians or other ancillary staff. Consequently, traditional fracture clinics, where orthopaedic residents learned casting techniques from senior residents or faculty, are gradually being replaced. Residency education now emphasizes the surgical aspects of orthopaedic care—such as indicating patients for procedures, mastering operative techniques, and formulating appropriate postoperative care.

In pediatric patients, cast application and management remains a cornerstone of orthopaedic practice. By taking advantage of structural benefits (ie, intact periosteum) and the biological factors involved in pediatric healing and remodeling, appropriate cast immobilization is often preferred over surgical treatment for fracture management. The benefits of early mobilization and range of motion to prevent loss of independent function and stiffness in adults do not apply to children. Parents or guardians can provide necessary support, and the risk of residual stiffness is minimal.

Optimal cast application in a child requires cooperation or at least compliance—an important consideration for younger children or those facing cognitive or behavioral challenges. These children may have difficulty understanding the need for casting, and their anxiety can increase with the presence of unfamiliar individuals, a chaotic environment, or pain. Managing these factors is essential for achieving a properly fitted cast. Although pain control and sedation are often necessary, additional strategies may be beneficial: using a soft voice, positioning yourself at or below the child’s eye level to reduce intimidation, and conducting the physical examination starting away from the injury site and gradually progressing. Preparing cast materials outside the room or out of the child’s direct view may help sustain a calm atmosphere.

Short arm cast

Indications

The short arm cast is an excellent form of immobilization for definitive treatment of torus and incomplete bicortical metaphyseal distal radius fractures.

True torus or “buckle” fractures are compression injuries that result in apparent unicortical failure of the distal radial metaphysis. In these inherently stable fracture patterns, studies have shown that a removable splint is adequate for safe treatment [1,2]. However, a recent survey reported that only 29.1% of surgeons stated they would use a removable splint to manage torus fractures, with potential concerns regarding patient compliance and medicolegal implications [3].

Incomplete or “greenstick” fractures represent the intermediate stage of bony failure between plastic deformation and complete fractures, characterized by at least one remaining intact cortex. These injuries typically result from bending moments. Closed reduction is carried out by reducing and molding opposite to the sagittal plane deformity.

Isolated distal ulna fractures or distal radius-associated ulnar styloid fractures may also be treated with a short arm cast.

Methods

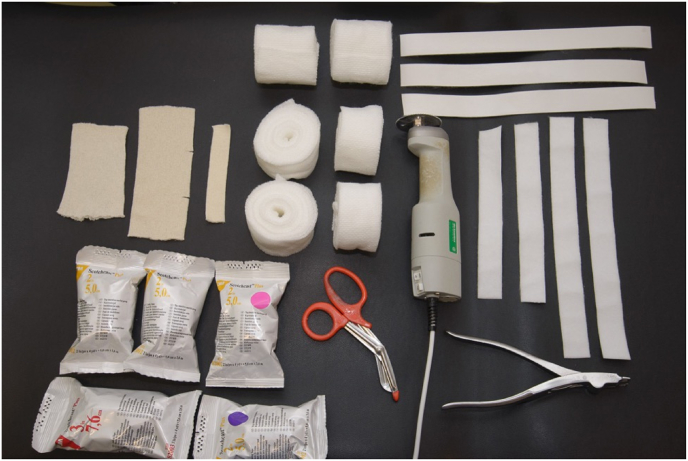

Essential materials that should be collected and prepared before application of the short arm cast as follows (Fig. 1):

-

•

Two appropriately sized stockinette pieces should be cut: one to be placed proximally at the level of the elbow and the other to be placed distally centered over the metacarpal heads. The distal piece should have two small slits on the radial side to accommodate the thumb.

-

•

A piece of 1-inch stockinette should be prepared to place over the thumb.

-

•

Three to six rolls of 2-inch cotton padding.

-

•

Two to four rolls of white 2-inch fiberglass cast.

-

•

One to two rolls of colored 2-inch fiberglass cast.

-

•

Cast saw

-

•

Cast splitter

-

•

Felt tape

Figure 1.

Supplies needed for short arm cast application.

The patient is positioned supine at the edge of the bed. If necessary, the fracture is reduced, and then an assistant holds the injured arm by the fingers. The elbow is flexed to 90°, and the forearm is in neutral rotation to facilitate easier cast application. The proximal and distal stockinette pieces are positioned to center at the proximal forearm and the metacarpal heads, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stockinette pieces should be fitted on the hand and forearm and then padded with cotton wrap.

Next, position the 1-inch stockinette over the thumb. It may help to cut a hole in the proximal end of this stockinette so it can be anchored onto the hand. Wrap the cotton padding circumferentially, taking care to avoid wrinkles. To minimize over padding and the risk of losing reduction, there should be a total of three to four layers of cotton padding along the forearm. At both proximal and distal ends, five layers of cotton padding should be used to enhance comfort.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Donald Bae: Once the limb is wrapped in cast padding, fiberglass, or plaster, pinpointing the exact location of the fracture can be challenging. This is especially critical when applying a three-point mold centered at the fracture site in very young children. Measuring the distance from the fracture to a fixed point outside the cast (eg, the tip of the thumb) can provide a useful reference point to aid in appropriate cast molding.

The 2-inch fiberglass cast material is then wrapped circumferentially, anchoring from the wrist, proceeding distally around the palm, and ending at the distal forearm. To prevent overcrowding the first webspace, the fiberglass should be “fan-folded” from the palm to the dorsal hand along the ulnar aspect. Any loose edges may be covered by a single fiberglass layer that traverses the first webspace (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Careful application of the fiberglass in the first webspace is essential to prevent cast irritation.

A total of three to four layers of fiberglass should be used throughout the short arm cast, again with careful avoidance of creases.

Master's Method.

Dr. Donald Bae: Twist or fold the casting material that is placed through the first webspace. This allows for 1) greater strength, 2) a narrower dimension of the cast material through the first webspace, which is helpful for young children, and 3) a reduced risk of sharp or rough fiberglass edges that might irritate the adjacent skin.

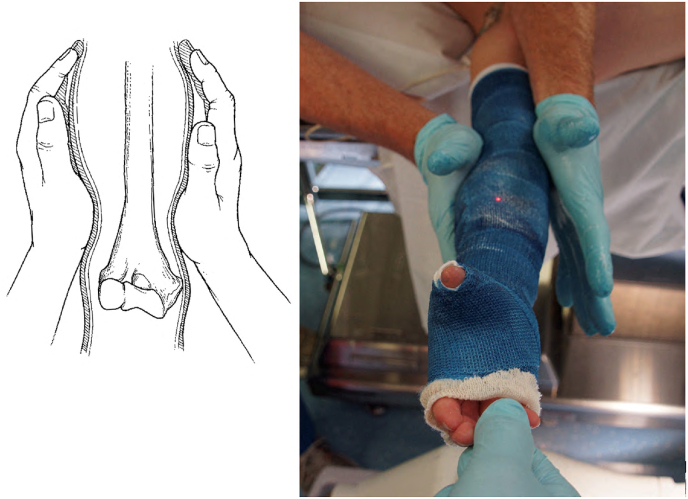

At this point, an appropriate three-point and/or interosseous mold should be applied (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

An example of a three-point mold.

Wrist flexion should be minimized to reduce the risk of median neuropathy [4]. Studies have shown that the cast index is the most predictive radiographic measure of late displacement [5]. Other indices predicting the effectiveness of cast immobilization include the three-point mold index, gap index, and Canterbury index. The risk of loss of reduction was lower in patients with a cast index of <0.7 [6]. After the mold is set, the stockinette ends can be rolled back, and a final colored layer of fiberglass cast is applied for added strength and esthetics.

The practice of univalving or bivalving casts varies among different institutions; however, a recent study showed no differences in maintaining reduction, the need for surgery, or complications between bivalved and circumferential casts [7]. Bivalving or univalving should be considered for acute fractures that undergo closed reduction (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A short arm cast after bivalving. Note that the bivalving is along the volar and dorsal surface as to not lose sagittal control of the reduction.

Bivalving should be performed along the volar and dorsal aspects of the cast to avoid inadvertently increasing the cast index and to prevent cast saw burns on bony prominences. Felt tape should be used to hold the cast together, and families should be instructed to remove the tape in case of excessive swelling or concerns about compartment syndrome.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

Using more than four layers of cotton wrap can result in overpadding, which risks losing the cast index and jeopardizing the reduction.

-

2.

Prevent wrinkles as they can irritate the underlying skin and potentially lead to pressure sores. The first webspace is a region susceptible to discomfort if the cast is applied carelessly.

-

3.

A cast index of 0.7 or less should be achieved to ensure adequate reduction and prevent late displacement.

-

4.

For young children at risk of inadvertently removing their cast, consider using a long arm cast instead.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Carley Vuillermin: A long arm cast is preferred over a short arm cast for young children. I consider young patients to be primarily those under 4 years of age.

Short arm cast with thumb spica

Indications

The short arm thumb spica cast should be utilized for scaphoid and thumb fractures.

Scaphoid fractures in the pediatric population are relatively uncommon, accounting for 3% of hand and carpal fractures and 0.34% of all fractures. Historically, pediatric scaphoid fractures have predominantly affected the distal pole; however, with changing patient characteristics and activities, fracture patterns in children and adolescents now resemble those in adults. Ninety percent of acute nondisplaced scaphoid fractures heal with nonoperative treatment. Since the scaphoid articulates with the thumb carpometacarpal joint, immobilization of the thumb is crucial for reducing stress on the scaphoid during the healing process. Allowing the thumb interphalangeal joint to remain free enables some retained dexterity without compromising stability.

Various thumb fractures can be treated with a short-arm thumb spica cast, including Salter–Harris II proximal phalanx fractures, diaphyseal metacarpal shaft fractures, and tuft fractures of the distal phalanx. The thumb interphalangeal joint should be included in the short-arm thumb spica cast for fractures located distal to the thumb metacarpal.

A short-arm thumb spica cast should also be considered for postoperative immobilization of distal radius fractures after closed reduction and percutaneous pinning to avoid pin site irritation when pins are placed in the radial styloid.

Methods

Similar to the application of a standard short arm cast, the patient is positioned supine with the elbow flexed at 90° and the forearm in neutral rotation. Additional considerations include using a longer segment of 1-inch stockinette, centered over the tip of the thumb, which allows it to be appropriately pulled back in the final stages of casting (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Placement and preparation of stockinette pieces for thumb spica cast.

Circumferential application of cotton padding should be carried out similarly, with the extension of three to four layers of padding to the tip of the thumb.

Next, the 2-inch fiberglass is applied, anchoring at the wrist and moving distally to the palm. The “fan-fold” maneuver is performed to avoid overcrowding the first webspace. The cast material is then wrapped circumferentially around the thumb for a total of three to four layers. The distal extent of the fiberglass should be determined based on the desire to include the interphalangeal joint (Fig. 7).

Figure 8.

Example of a thumb sprain without deformity (A) placed into a thumb spica cast in a hyperextended and hyperabducted position (B), now with an iatrogenically induced deformity (C) after cast removal.

Figure 7.

Examples of thumb spica casts with interphalangeal (IP) joint free and IP joint immobilized.

The fiberglass cast is then wrapped proximally to the mid-forearm.

Most short-arm thumb spica casts stabilize fractures that do not need reduction. Therefore, a distal mold is often unnecessary. One exception is the Salter–Harris II proximal phalanx fracture, which typically benefits from a suitable mold. Additionally, excessive wrist flexion should be avoided. The ends of the stockinette should be folded down and a final cast layer should be applied. Bivalving is rarely indicated.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Donald Bae: In their desire to provide adequate padding and cast material around the thumb and through the first webspace, less experienced providers may inadvertently hyperextend or hyperabduct the thumb during thumb spica cast application (Fig. 8). While adequate padding and support is important, care should be made not to exacerbate bony deformity or impart undesirable joint position during spica cast application.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

The first webspace can be a weak area if insufficient layers of fiberglass cast are used. However, be cautious not to overcrowd this space and unintentionally create radial deviation of the thumb.

-

2.

The interphalangeal joint should remain free from fractures at or proximal to the thumb metacarpal.

Mitten cast

Indications

Mitten casts are recommended for finger fractures, and in young children with fingertip injuries or following the pinning of finger fractures, a covered mitten cast provides protection.

Pediatric hand fractures account for approximately 2.3% of all emergency department visits. Among pediatric patients, proximal phalanx fractures are the most common, while metacarpal fractures are more prevalent in adolescents compared with younger children. The robust periosteum and high remodeling potential in pediatric patients allow for most hand fractures to be managed nonoperatively with appropriate immobilization. The advantage of the mitten cast is that it provides complete immobilization of the index, long, ring, and small fingers, countering the forces from the common muscle bellies of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and extensor digitorum communis (EDC).

Generally, distal fingertip injuries, with or without a fracture, may be treated with finger splint immobilization to provide rest for the soft tissue. However, in young and/or very active children, removable immobilization devices should be avoided. A covered mitten cast should be considered for these patients. For similar reasons, a long arm cast should be contemplated if there are concerns about inadvertent cast removal.

A mitten cast is also helpful for postoperative care following finger fracture fixation techniques, such as percutaneous pinning or internal fixation, because it can offer added stability and protection.

Methods

Positioning and setup are similar to the application of the short arm cast. The distal segment of the stockinette should be cut significantly longer, so the proximal edge is at the level of the wrist, and the distal edge extends well past the fingertip edges. This allows the distal edge to be pulled back over the fiberglass while still providing appropriate coverage of the fingertips. Circumferential application of cotton padding should be done, with the extension of three to four layers of padding approximately 1 cm distal to the long finger fingertip (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Cast padding should extend 1 cm distal to the fingertips for a mitten cast.

A 2-inch fiberglass cast is applied using a technique similar to that of a short arm cast. After “fan-folding” at the palm, the fiberglass is extended distally to the fingers, and three to four layers of circumferential wrap is applied distally, approximately 1 cm past the tip of the long finger. Proximally, the fiberglass is completed at the mid-forearm.

It is essential to allow adequate space and avoid crowding of the webspaces. This can be achieved by “fish mouthing” or pulling apart the radial and ulnar aspects of the opening (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

“Fish mouthing” avoids crowding of the fingers.

The hand should be molded to the desired position. An intrinsic plus position is a safe, neutral hand position that accommodates most fractures. Occasionally, a straight mitten cast in extension may be indicated for specific injuries, such as extensor tendon injuries, central slip avulsion fractures, or Salter–Harris II proximal phalanx fractures without sagittal deformity. After the initial fiberglass layer is set, the stockinette ends are folded down, and the final cast layer is applied. Bivalving is not usually necessary for mitten casts.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Donald Bae: Extending the cast beyond the fingertips while still allowing the tips to be visible can be useful, particularly in very young patients at risk for cast slippage. Fingertips that are initially visible but subsequently “disappear” may alert care providers of distal migration of the cast and impending cast slippage.]

The application of the covered mitten cast involves wrapping both the cast padding and fiberglass over the tips of the fingers. When planning for a covered mitten cast, the gauze should be placed between the digits to prevent excessive sweating. During the placement of the cotton padding and fiberglass, the material is wrapped back and forth over the fingertips to ensure complete coverage of the fingertips (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Example of a covered mitten cast with fingers extended.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

The thumb should remain outside a mitten cast to avoid causing unnecessary stiffness.

-

2.

A mitten cast can be adjusted to provide full coverage, which can be beneficial for protecting fingertip injuries in young children.

-

3.

Remember to leave sufficient space in the radial/ulnar plane to prevent crowding of the fingers. Insufficient space may lead to irritation, maceration, or even pressure sores.

-

4.

Consider buddy taping the injured finger to a nearby uninjured finger to act as an extra splint beneath the cast.

Ulnar gutter cast

Indications for ulnar gutter casts in children are limited as pediatric patients often tolerate a mitten cast quite well. Typically, an ulnar gutter cast is preferred over a mitten cast for patients older than 10 years with a ring or small finger fracture in their dominant hand. This approach allows for writing and retains some function of the thumb and radial digits.

Methods

The setup and application of the ulnar gutter cast are similar to those of the mitten cast. The distal stockinette should be carefully cut to allow the radial digits to remain free (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Stockinette placement for an ulnar gutter cast, which allows free motion of the index and long fingers.

Alternatively, a separate 2-inch stockinette may be used as an adjunct to isolate the ulnar digits. It is important to include one additional finger radial to the injured finger (ie, for ring finger injuries, the long finger should be included in the ulnar gutter cast). Careful application of cotton padding and fiberglass is necessary to avoid overcrowding the webspace, which may be irritating. Care should be taken to not inadvertently ulnarly deviate the digits during cast application. Bivalving an ulnar gutter cast is not typically recommended.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Carley Vuillermin: Traditional teaching suggests that casts extending across the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and interphalangeal (IP) joints of the fingers should be positioned in the intrinsic plus position. However, studies on young adults and pediatric patients have shown that it is safe to place the cast with the MCP joints in extension and the IP joints in a comfortable position without risking long-term stiffness. This approach offers several advantages, including the following: 1) easier direct three-point molding, 2) better visualization on follow-up radiographs, and 3) ease of dressing.

The ulnar gutter cast can be beneficial for postoperative immobilization. However, it is not recommended for distal phalanx fractures and FDP repairs because of the common muscle belly of the FDP. Movement of the uncasted digits may displace the fracture or compromise the repair, respectively.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

Ulnar gutter casts can help retain some functionality in the hand, such as writing or grasping, and should be considered an alternative to mitten casting for older patients (10 years and older) with injuries to the dominant hand.

-

2.

One additional digit radial to the injured digit should be incorporated into the ulnar gutter cast (ie, for injuries to the ring finger, the long finger should be included).

-

3.

Cast material can cause irritation between fingers, particularly for patients with sensory disorders or sensitive skin.

-

4.

Ulnar gutter casts are not recommended for distal phalanx fractures and FDP repairs due to the shared muscle belly of FDP. Movement of uncasted fingers may displace fractures, weaken repairs, and cause pain.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Carley Vuillermin: Consider including three fingers instead of two in an ulnar gutter cast. Naturally, the index finger is used independently, and some patients find the bulk of the cast between the middle and ring fingers bothersome.

Long arm cast in flexion

Indications

The long arm cast with elbow flexion is a primary method of immobilization for several types of injuries, including complete bicortical distal radius fractures, forearm fractures, and elbow fractures.

Complete bicortical fractures of the distal radial metaphysis may result from bending, rotational, or shear mechanisms of injury. Nondisplaced bicortical fractures are inherently unstable and carry a risk of late displacement; therefore, they should be treated with immobilization and careful serial monitoring. These fractures may be mistaken for torus fractures, making careful evaluation of both cortices on radiographs crucial. While studies have suggested that short arm casts are as effective as long arm casts in maintaining fracture alignment, many practices favor using a long arm cast for complete bicortical distal radius fractures.

Shaft fractures of the radius and ulna are common injuries among pediatric patients, accounting for 5%-10% of all fractures in children. The mechanism of injury should be understood before attempting closed reduction. Long arm cast immobilization should be directed against the deforming muscle forces—pronation, supination, and radial deviation. Fractures involving the distal radial ulnar joint (Galeazzi fracture dislocation) or the proximal radial ulnar joint and the radiocapitellar joint (Monteggia fracture dislocation) may similarly be treated, or at least temporized, with a long arm cast.

Some injuries result from torsional mechanisms, and the pattern of deformity is classically multiplanar with a fracture apex either volarly or dorsally. Closed reduction is done by reversing the rotational deformity, followed by correcting the angulation. The “rule of thumbs,” in which the thumb is rotated toward the apex of the deformity, has been proposed to guide providers about the appropriate reduction maneuver [8].

Some elbow fractures may be treated definitively with long arm cast immobilization. These injuries include radial head and neck fractures, medial epicondyle fractures, minimally displaced lateral condyle fractures, type 1 supracondylar humerus fractures, and occult elbow fractures. For fractures that require surgical management, a long arm cast may serve as a temporary stabilizer before or after definitive treatment.

In young children and those with poor compliance to short arm casting, a long arm cast may be used instead to maintain the position of the arm and prevent slippage.

Methods

Similar to the short arm cast, supplies should be collected and prepared before starting the casting process (Fig. 13).

-

•

Two appropriately sized stockinette pieces should be cut: one to be placed proximally at the level of the proximal humerus and other to be placed distally centered over the metacarpal heads. The distal piece should have two small slits on the radial side to accommodate the thumb.

-

•

One piece of 1-inch stockinette should be prepared to place over the thumb.

-

•

Four to eight rolls of 2-inch cotton padding.

-

•

Three to five rolls of white 2- or 3-inch fiberglass cast.

-

•

One to two rolls of colored 2- or 3-inch fiberglass cast.

-

•

Cast saw.

-

•

Cast splitter.

-

•

Felt tape.

Figure 13.

Supplies needed for long arm casting.

The patient is positioned supine at the edge of the bed. The reduction is performed, and the injured arm is then held by the fingers by an assistant. Any platform (such as a hand table) should be removed. The elbow is flexed to the desired position, usually between 70 and 90°. Excessive elbow flexion beyond 90° is avoided, as compression of the brachial artery or anterior interosseous artery may occur, potentially leading to iatrogenic Volkmann ischemic contracture. Generally, neutral forearm rotation is preferred; however, some fractures are more stable in certain degrees of supination or pronation. The optimal position of forearm rotation during long arm casting is controversial, but it is important to consider subsequent follow-up and the ease of repeat radiographic evaluation.

The proximal and distal stockinette pieces are centered at the proximal humerus and the metacarpal heads, respectively. Position the 1-inch stockinette over the thumb. Cotton padding is wrapped circumferentially to create a total of three to four layers, taking care to avoid creases. The elbow can be a challenging area for maneuvering the cotton padding. Care should be taken not to overstuff the antecubital fossa; in most cases, excess cotton padding should be removed. A two to three layer cotton splint should be placed at the posterior elbow to provide adequate padding (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

An additional posterior slab of cotton padding is often needed.

The 2-inch fiberglass cast is then circumferentially wrapped similar to a short arm cast initially. As the fiberglass cast approaches the elbow, various techniques may be used to ensure no cast creasing when making the turn around the elbow.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Carley Vuillermin: Be very vigilant with this step. Remind your assistant to maintain the position and not to move in order to accommodate you while wrapping the casting material. It can be helpful with small children to start with the elbow just over 90° flexed as it will ultimately end up under 90° at the conclusion of casting.

If you apply a cast and find that the elbow is too extended, don’t just flex it! Take the time to remove the cast and reapply it correctly. The pressure areas in the cubital fossa are not worth the risk.

If x-rays are taken after the cast is applied, look at the bones and the cast, as you can often identify wrinkles or possible pressure points in the cast.

Several molds should be utilized to ensure the proper fitting of the long arm cast. An appropriate interosseous mold must be applied. Particular attention should be given to maintain a straight ulnar border and preventing the creation of a “banana cast.” This is imperative not only to combat the radially deviating pull of the brachioradialis but also to prevent small arms from slipping out of the cast (Fig. 15).

Figure 15.

A straight ulnar border is essential for application of a long arm cast. This prevents ulnar angulation of the forearm fracture after swelling goes down.

Proximally, a supracondylar mold should be applied to provide additional support and prevent cast slippage (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

A supracondylar mold helps prevent cast slippage.

The posterior sagittal cast index, a ratio of maximal posterior cast space (ie, padding) to elbow soft-tissue diameter at the level of the antecubital fossa, can be used to measure long arm cast fit. A posterior sagittal cast index >0.20 is associated with loss of reduction [9]. After the molds are set, the stockinette ends are rolled back and a final layer of fiberglass cast is applied.

Master’s Method.

Dr. Carley Vuillermin: Molding is essential for fracture reduction and maintenance in all patients. In smaller patients, particularly those under 3 years of age, molding also helps reduce the risk of cast slippage. The key molds to minimize the risk of cast slippage are the flat posterior humeral and ulnar border molds that create a 90° angle, along with the supracondylar mold.

Valving should be considered for acute fractures that undergo closed reduction or for significantly swollen arms. Felt tape should be used to hold the cast together, and families should be instructed to remove the tape if there are concerns about compartment syndrome.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

Avoid a “banana cast” by shaping a straight ulnar border and posterior humeral border, along with an interosseous and supracondylar mold.

-

2.

Do not flex the elbow beyond 90° as iatrogenic compression of the brachial and/or anterior interosseous arteries may result in Volkmann ischemic contracture.

-

3.

Position the cotton padding around the arm in the desired final position as flexing the elbow after padding significantly increases the pressure within the antecubital fossa.

-

4.

Avoid excessive padding of the antecubital fossa as this can lead to vascular compromise.

Long arm cast in extension

Indications

Indications for long arm casting in extension for trauma include proximal forearm fractures that have unacceptable angulation of more than 10° or for closed treatment of nondisplaced olecranon fractures (Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21). However, outside of trauma, long arm casts are an invaluable tool for serial casting for elbow flexion contractures secondary to brachial plexus birth injury, cerebral palsy, and post-traumatic stiffness.

Figure 17.

This 9-year-old girl has a 7-day-old proximal forearm fracture with 15° of angulation in her long arm flexion cast, who was indicated for reduction and placement of an extension cast.

Figure 18.

The fracture is reduced under fluoroscopic imaging and the cotton is wrapped to include the thumb.

Figure 19.

The fracture is reduced and held while the fiberglass hardens.

Figure 20.

Supracondylar mold will prevent the cast from slipping distally.

Figure 21.

The cast is finished and split to allow for swelling.

Methods

Supplies and steps for applying a long arm cast are similar for the elbow in flexion and extension. Generally, full extension is avoided due to the increased risk of cast slippage. A small degree of elbow flexion (10-30°) is well tolerated for the treatment of nondisplaced olecranon fractures. The straight ulnar border and supracondylar molds are particularly essential for maintaining cast position while the elbow is extended. Including the thumb can also prevent the cast from sliding distally. Bivalving should be considered for extremely swollen elbows, with a plan for cast overwrap once swelling subsides.

The dropout cast is a unique variant of the long arm cast designed to prevent elbow flexion and facilitate gradual elbow extension. This cast is utilized for serial casting of elbow flexion contractures greater than 30°. Once the cast is applied in maximum tolerated extension, the patient can perform elbow extension exercises within the cast to further stretch the elbow between casting sessions. When the contracture decreases to less than 30°, the dropout cast is more likely to slip off, prompting the use of a traditional long arm cast in extension.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

•

Extension casts often slip distally in younger children, so consider using long arm flexed casts for those under 5 years of age.

-

•

Supracondylar molds are particularly important in preventing cast slippage. Similarly, attention should be given to the sharp angle formed by a straight ulnar and the posterior border of the humerus.

-

•

Extended periods of cast immobilization with the elbow in extension pose a heightened risk of stiffness and loss of terminal flexion.

Hanging arm cast

Indications

The utility of hanging arm casts is limited, except for the closed treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures. Compared with a cuff and collar sling, a hanging arm cast provides gravity-assisted traction by relying on its additional weight, theoretically allowing for gradual reduction and maintenance of displaced proximal humerus fractures. Its use is typically reserved for older children and adolescents.

Methods

The application of a hanging arm cast is similar to that of a standard long arm cast in elbow flexion. Since the targeted fracture involves the proximal humerus, it is important to end the cast just proximal to the elbow to avoid creating a modulus mismatch at the fracture level. An addition of a fiberglass “D-ring” may be opted to allow easier sling use around the neck (Fig. 22).

Figure 22.

A D-ring may be fashioned to allow for easier sling use.

Pearls, pitfalls, and complications

-

1.

The hanging arm cast uses gravity-assisted traction but does not provide actual protection or immobilization of the fracture.

-

2.

Children and adolescents should sleep upright for the first 7-10 days to allow traction to effectuate reduction.

-

3.

Wrist and elbow stiffness may result from prolonged use.

-

4.

The efficacy of a hanging arm cast over a simple sling is debatable.

Summary

In this chapter, we emphasize the benefits and challenges of upper extremity cast application in pediatric patients. In the current orthopaedic landscape, where techniques and indications are expanding, casts remain essential in treating pediatric orthopaedic trauma. As orthopaedic subspecialization advances and clinical roles become more strictly defined, mastering the art of casting poses a growing challenge.

To summarize, the purpose of a cast is to maintain the reduction of a fracture. Complications arise from the inappropriate use of a cast to achieve correction. Providers should remember that while casting is generally a benign treatment with historically positive outcomes, complications may still occur. Pressure sores can develop due to inadequate padding, sharp angles, or creasing of the fiberglass. Cast burns are an avoidable complication; however, the incidence is not zero. Especially in small children who cannot express their discomfort or other warning signs, special care should be taken to mitigate risks.

The art of casting requires a high level of orthopaedic foundational knowledge, including an understanding of anatomy and the relevant deforming forces, trust in biology and the power of remodeling, as well as the ability to navigate the child’s psyche and family expectations. As orthopaedic surgery advances, these foundational principles remain integral to the treatment we provide to our patients. Therefore, there will always be a need for a technically proficient cast in the treatment of pediatric trauma.

Test your knowledge

Review questions and answers for the JPOSNA® Primer on Cast and Splint Application can be found through the links below.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author contributions

David S. Liu: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Andrea S. Bauer: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Ethics approval and consent

The authors declare that no patient consent was necessary as no images or identifying information are included in the article.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to our consultant cast masters Donald Bae, MD, and Carley Vuillermin, MBBS, FRACS.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: JPOSNA® Primer on Cast and Splint Application published in Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America.

References

- 1.Liu D.S., Murray M.M., Bae D.S., May C.J. Pediatric and adolescent distal radius fractures: current concepts and treatment recommendations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2024;32:e1079–e1089. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-23-01233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry D.C., Achten J., Knight R., Appelbe D., Dutton S.J., Dritsaki M., et al. Immobilisation of torus fractures of the wrist in children (FORCE): a randomised controlled equivalence trial in the UK. Lancet. 2022;400:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry D.C., Gibson P., Roland D., Messahel S. What level of immobilisation is necessary for treatment of torus (buckle) fractures of the distal radius in children? Bmj. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelberman R.H., Szabo R.M., Mortensen W.W. Carpal tunnel pressures and wrist position in patients with Colles' fractures. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1984;24:747–749. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alemdarolu K.B., Iltar S., Cimen O., Uysal M., Alagöz E., Atlihan D. Risk factors in redisplacement of distal radial fractures in children. J Bone Jt Surg. 2008;90:1224–1230. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohm E.R., Bubbar V., Yong-Hing K., Dzus A. Above and below-the-elbow plaster casts for distal forearm fractures in children. J Bone Jt Surg. 2006;88:1–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae D.S., Valim C., Connell P., Brustowicz K.A., Waters P.M. Bivalved versus circumferential cast immobilization for displaced forearm fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37:239–246. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waters P., Skaggs D., Flynn J. ninth ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2020. Rockwood and Wilkins' Fractures in Children. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehlman C.T., Denning J.R., McCarthy J.J., Fisher M.L. Infantile supracondylar humeral fractures (patients less than two years of age): twice as common in females and a high rate of malunion with lateral column-only fixation. J Bone Jt Surg. 2019;101:25–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]