Abstract

Some human cancer cells achieve immortalization by using a recombinational mechanism termed ALT (alternative lengthening of telomeres). A characteristic feature of ALT cells is the presence of extremely long and heterogeneous telomeres. The molecular mechanism triggering and maintaining this pathway is currently unknown. In Kluyveromyces lactis, we have identified a novel allele of the STN1 gene that produces a runaway ALT-like telomeric phenotype by recombination despite the presence of an active telomerase pathway. Additionally, stn1-M1 cells are synthetically lethal in combination with rad52 and display chronic growth and telomere capping defects including extensive 3′ single-stranded telomere DNA and highly elevated subtelomere gene conversion. Strikingly, stn1-M1 cells undergo a very high rate of telomere rapid deletion (TRD) upon reintroduction of STN1. Our results suggest that the protein encoded by STN1, which protects the terminal 3′ telomere DNA, can regulate both ALT and TRD.

Telomeres are the DNA-protein complexes that protect the ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes (19, 57). They are normally maintained by the reverse transcriptase telomerase, which utilizes a sequence within its RNA component as a template to add new telomere repeats onto the 3′ end. Telomerase plays a vital role in immortalization of human cancer cells. Since a majority of human somatic cells lack telomerase activity, expression of telomerase in many cells is sufficient to achieve immortalization, one of the characteristic features of cancer cells (5). Thus, chromosome end protection or “capping” and telomere length regulation play an important role in preventing cancer and genomic instability in human cells.

How capping is achieved is not fully clear, but a number of proteins binding to the single- or double-stranded region of the telomeres are known to be involved in regulating this process (9, 19, 42, 57). In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the 3′ telomeric terminus is protected by Stn1p in association with Ten1p and the single-strand telomere binding protein Cdc13p (11, 16, 18, 24, 25). Recruitment of Stn1p to the telomere by fusion of the DNA binding domain of Cdc13p is sufficient to rescue the lethality of the null mutation of cdc13 (11, 50). Another yeast telomere protein influencing end protection is Rap1p, which binds to duplex telomere sequences (3) and appears to prevent the occurrence of telomere fusions (41). Similarly, in human cells, single-stranded telomere binding protein POT1 and its interacting protein (PTOP/TINT/PIP1), along with duplex telomeric DNA binding proteins TRF1 and TRF2, have been implicated in providing end protection and contributing to telomere length control (1, 4, 35, 57, 67, 68). Additionally, in a variety of organisms the telomeres have been postulated to form a protective structure, where the 3′ end is thought to strand invade into the internal duplex region of the telomere to form a t loop (10, 26, 44, 48, 60, 61). Whether budding yeast telomeres form t loops is still unknown; however, some evidence indicates that they exist as fold-back structures (14).

Defects in capping can lead to a variety of problems including telomere fusions, disrupted telomere length regulation, elevated recombination near telomeres, degradation of the 5′ strand of telomeric DNA, DNA damage checkpoint activation, and premature senescence (2, 19, 42). Many or all of these problems arise from telomeres being recognized as DNA double-strand breaks. In yeast mutants lacking telomerase, telomeres gradually shorten, leading to a gradual decline in growth rate, cell cycle arrest, and cell death from critically short or uncapped telomeres. Rare emergence of postsenescence survivors occurs due to recombinational telomere elongation (RTE) (36, 38, 59). In S. cerevisiae, telomere elongation by RTE occurs either by amplification of the telomeric DNA sequences (type II RTE) or by amplification of subtelomeric DNA sequences while maintaining short telomeric terminal tracts (type I RTE) (36, 59). However, only the type II RTE pathway has been shown to occur in Kluyveromyces lactis (38). The K. lactis survivors are proposed to arise through a “roll-and-spread” mechanism (46). According to this model, a small telomeric DNA circle acts as a template to elongate a single telomere by rolling-circle replication. Subsequently, the spreading of the sequence from this elongated telomere to other telomeres occurs by gene conversion (62). Additional data have shown that telomeric circles transformed into K. lactis strains promote RTE and that DNA circles as small as ∼100 bp can form in a mutant with long dysfunctional telomeres (26a, 45, 46).

In a minority of human cancer cells, telomerase activity is absent and the telomeres are maintained by the activation of alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) (7). ALT is thought to involve recombination, as a sequence tag introduced in a single telomere in an ALT cell lineage often became copied to additional telomeres (17). ALT is best characterized, in addition to lack of telomerase activity, by extreme telomere length heterogeneity and the presence of ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies (APBs) (28). APBs are intranuclear structures that contain a number of telomere- and recombination-specific proteins including TRF1, TRF2, RAD51, RAD52, and the RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 complex (28, 54). The molecular mechanisms triggering ALT are presently unknown.

In addition to elongating telomeres, recombination has also been shown to trigger sudden deletion of telomere sequences in yeast, a process termed telomere rapid deletion (TRD) (33, 37). Telomere truncations have also been observed in other organisms, such as Euplotes, Tetrahymena, and Xenopus, and in human ALT cells (13, 32, 51, 64). Whether these truncations involve recombination, is currently unknown.

In this study, we have identified a mutation in the K. lactis STN1 gene manifesting a striking combination of phenotypes including telomere capping defects, very long and heterogeneous ALT-like telomeres produced by recombination, and a rapid shortening of all telomeres upon reintroduction of STN1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast media and strain construction.

All K. lactis cells used in this study are derivatives of the wild-type haploid strain 7B520 (ura3-1 his2-2 trp1) (66). The K. lactis plasmid genomic library used to clone the STN1 gene was previously described (29).

Serial passaging of all the strains was performed by selecting single colonies and allowing them to grow for 3 days at 30°C on standard rich media containing yeast extract, peptone, and dextrose (YPD). The construction of stn1-M1 ter1-Δ and stn1-M1 TER1-20C(ApaL) double mutants was performed through standard yeast replacement procedures. Replacement of the native TER1 gene by a ter1 gene disrupted by the URA3 construct was done by transplacement as described previously (38). Replacement of the TER1 gene by TER1-20C(ApaL) was done by a plasmid “loop in-loop out” procedure described previously (39). Additionally, the K. lactis rad52 and ter1-Δ7:URA3 deletion alleles, described previously (38), were used for isolating the double-mutant stn1-M1 ter1-Δ and stn1-M1 rad52Δ strains by mating and tetrad dissection.

Random spore analysis was performed on the spores generated by mating the 7B520 derivative stn1-M1 ura3 his2 trp1 strain with the UA24B (rad52 ade2) strain. Spores created from the diploid cells of this mating were scooped off the sporulation plate and incubated in 200 μl of 100T Zymolyase (concentration of 0.17 mg/ml in 1 M sorbitol) at 37°C for 10 min to digest the ascus sac. The spores were serially diluted in TE (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA) and plated on several synthetic complete (SC) plates lacking uracil and adenine. They were plated to an approximate cell density of ∼200 viable cells per plate and allowed to form relatively large colonies at 30°C so that the rough-colony morphology of stn1-M1 mutants could be easily distinguished. Individual colonies selected for further analysis were digested with EcoRI and hybridized to a RAD52 gene fragment probe to test for the presence of stn1-M1 rad52 double mutants.

Southern and nondenaturing in-gel hybridizations.

Yeast genomic DNA was isolated from overnight liquid YPD cultures grown at 30°C. Fragments were separated on 0.8% agarose gels and electrophoresed at 25 V for 15 h and then at 35 V for 3 h. They were transferred to HyBond N+ membranes, and hybridization was performed as described previously (12a) at 49°C, with either of two end-labeled telomere probes (G-probe, Klac1-25 [5′ACGGATTTGATTAGGTATGTGGTGT-3′], or C-probe, Klac25-1 [5′-ACACCACATACCTAATCAAATCCGT-3′]). Hybridization of a labeled subtelomere fragment (∼0.6-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment from plasmid pAK25ΔB) using a random priming kit (Stratagene) was also carried out at 65°C as described previously (63). The membranes were autoradiographed using PhosphorImager analysis (Bio-Rad; Molecular Imager). In-gel hybridization experiments were performed as described previously (15) using a telomere oligonucleotide as a probe (Klac25-1). Approximately 3 μg of undigested DNA was electrophoresed through a 0.7% agarose gel and then analyzed using the conditions described previously (63).

Mutagenesis.

EMS (ethyl methanesulfonate) mutagenesis was performed using the wild-type haploid strain 7B520 (ura3-1 his2-2 trp1). Briefly, 5 ml (108 cells/ml) of cells was treated with 50 μl of EMS and incubated for 2 h at 30°C. To obtain a 50% survival rate, 1 ml of the culture was removed after every 30 min and the reaction was inactivated by the addition of 8 ml of 5% sodium thiosulfate. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the cells from the 60-, 90-, and 120-min time points were plated on YPD plates to a density of 200 viable cells per plate and allowed to grow at 30°C for 3 days, so that rough-colony morphology could be easily distinguished.

Subtelomere gene conversion assay.

The gene conversion assay was performed according to the protocols described previously (40). Briefly, one of the native telomeres in the stn1-M1 mutant strain was replaced by transformation with an ∼2.0-kb EcoR1 and SacII “STU” (subtelomere, URA3) fragment containing the URA3 gene from S. cerevisiae inserted into the subtelomeric sequence of a cloned K. lactis telomere. Serially diluted cells of clones containing the “STU” fragment were plated on SC plates lacking uracil, SC plus 5-FOA (5-fluoroorotic acid), and YPD. Measurement of the loss of the URA3 gene was performed by counting colonies grown on 5-FOA with respect to the total number of colonies grown on YPD and SC plates.

RESULTS

Identification of a K. lactis mutant with extremely long telomeres.

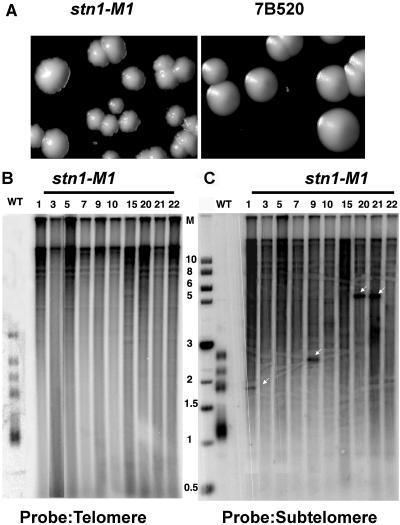

In order to identify mutants affecting telomere maintenance in K. lactis, we performed a screen for haploid mutants exhibiting abnormal colony morphology by EMS mutagenesis. Earlier work demonstrated that a rough-colony phenotype was characteristic of both telomere deletion and runaway elongation mutants of haploid K. lactis strains (38, 39). Approximately 10,000 colonies arising from EMS-treated wild-type cells were screened at 30°C, and a total of 345 abnormal colonies were identified. After restreaking on YPD plates to confirm their phenotypes, these mutants were examined for telomere length defects by Southern analysis. Subsequently, we identified 30 mutant candidates exhibiting various degrees of mild telomere length defects and two mutants that exhibited dramatic telomere elongation. The telomere and colony phenotypes of the mutant named M1 are shown in Fig. 1A and will be the focus of this study. This mutant exhibited a heterogeneous telomere repeat signal, ranging from limit mobility (>20 kb) to ∼100 bp (Fig. 1B). The presence of a telomere signal below 0.7 kb (the size of the subtelomere DNA in the smallest EcoRI telomere fragment in our wild-type K. lactis strain [47]) indicated that a significant amount of telomeric DNA existed in extrachromosomal form. Further passaging of the M1 mutant revealed that the highly elongated telomeres were maintained without apparent change over at least 600 cell divisions (Fig. 1B). A subtelomere probe exhibited a signal migrating from limit mobility to below 1 kb (Fig. 1C). We conclude that telomeres in the M1 mutant are extremely heterogeneous in length, ranging from short to extremely long. In order to estimate the amount of telomeric DNA in the M1 mutant, we quantitatively analyzed the total telomere hybridization signal in the mutant with respect to the wild-type strain by using a PhosphorImager. The results indicated a greater-than-10-fold increase in the number of telomere repeats in the M1 mutant. An interesting observation was the appearance of occasional sharp bands visible with the subtelomeric probe (arrows, Fig. 1C). These may represent unstable telomere-telomere fusions. Similar unstable sharp bands in certain K. lactis long ter1 template mutants have been shown to be telomere fusions (41).

FIG. 1.

Identification of a K. lactis mutant with extremely long telomeres. (A) The left panel shows the rough-colony morphology of the M1 mutant, while the right panel shows the isogenic 7B520 wild-type strain. (B) Shown is a Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from the M1 mutant hybridized to probe Klac1-25, composed of one (25-nucleotide) repeat of the G-strand K. lactis telomeric sequence. The individual clone was passaged for 22 streaks (∼440 to 550 cell divisions), and samples were periodically selected for genomic DNA extraction. The wild-type sample is shown overexposed for clarity. (C) The same blot was stripped and reprobed with a subtelomeric probe. Rare sharp bands marked by white arrows may represent fusions between chromosomes with few or no telomeric repeats. Molecular size markers (M), shown in the middle, are in kilobase pairs.

The elongated telomeres in the M1 mutant appear to be composed entirely of telomeric repeats.

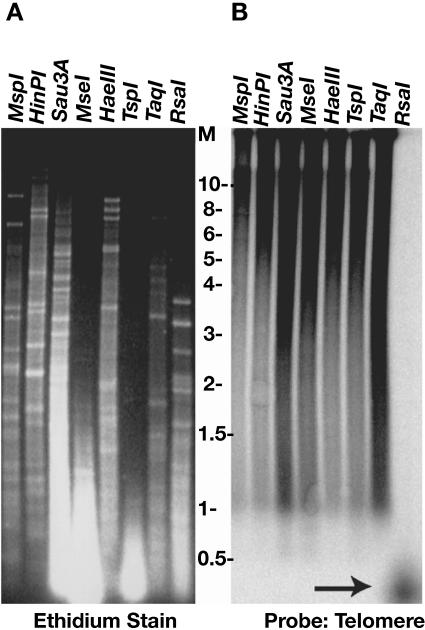

We next investigated if the telomere elongation in the M1 mutant was entirely due to amplification of the telomeric repeat sequences. Genomic DNA was extracted and subjected to digestion with several restriction enzymes with 4-bp recognition sequences. Of the enzymes used, only RsaI has a recognition site within the telomeric repeat of K. lactis and was expected to cleave away all the telomeric repeats. Southern hybridization using a telomeric probe showed that all digestions except that with RsaI left the long heterogeneous telomeres intact while bulk genomic DNA was cleaved down to small sizes (Fig. 2, compare panels A and B). In contrast, the sample digested with RsaI showed no telomere signal at high molecular weight and only a faint smear that migrated well below 500 bp (Fig. 2B). We conclude that the long heterogeneous telomere fragments in mutant M1 are due to elongated tracts of telomeric repeats. An interesting observation in almost all examined restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA samples from cells of the M1 mutant was the presence of a substantial telomeric hybridization signal (but not bulk chromosomal DNA) in the wells (Fig. 1 and 2 and data not shown). This telomeric signal in wells is resistant to proteinase K (data not shown) and appears to be a general characteristic of K. lactis mutants with extremely long telomeres (39, 63). This suggested that telomeric DNA from M1 cells was often present in a tangled form unable to migrate into the gels. Interestingly, the fraction of telomeric DNA in the well increased in the TaqI digestion, the only digestion performed at 65°C. One possible explanation for this result is that the DNA represents recombination intermediates with complex branched structures and heating at 65°C further promoted the formation of these structures.

FIG. 2.

Telomere elongation in the M1 mutant is exclusively due to additional telomeric repeats. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained gel of genomic DNA from the “M1” mutant digested with eight different restriction enzymes, as labeled. (B) The gel in panel A was hybridized to the Klac1-25 telomere probe. All the telomeres in the lane labeled RsaI have been digested down to less than ∼50 bp (arrow), as each K. lactis telomeric repeat contains an RsaI site.

STN1 complements the M1 mutation in K. lactis.

To test if a mutation in a single gene was responsible for the defect seen in the M1 mutant, a segregation analysis was performed. The M1 mutant was mated to a wild-type K. lactis haploid strain of the opposite mating type, and the resulting diploids were sporulated. The results showed that only two of the four spores were viable in most of the 15 tetrads dissected. In each of the three tetrads where three spores were viable, the extra spore grew to exhibit the rough-colony morphology characteristic of the M1 mutant. Each of the rough colonies produced as a consequence of sporulation was analyzed for telomere length by Southern analysis and found to contain long and heterogeneous telomeres similar to those seen in the original M1 mutant (data not shown). These results support the idea that a single gene was responsible for both the telomeric defect and the rough-colony phenotype of the M1 mutant. Additionally, it also indicated that this mutation was lethal to a high percentage (90%) of spores. The poor viability of stn1-M1 spores was observed with diploids produced by backcrossing, and its basis remains unknown.

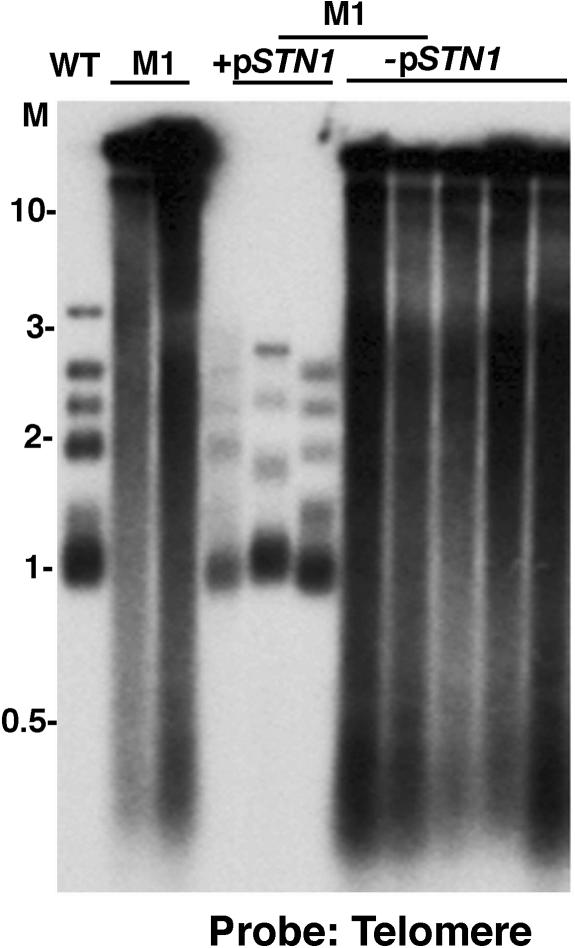

Subsequent efforts focused on complementing the M1 mutation by transforming a K. lactis genomic library plasmid into M1 mutant cells. The transformed cells were incubated at 37°C, which was semipermissive to wild-type K. lactis and exacerbated the growth defects of the M1 mutant. Approximately 20,000 transformants were visually screened for larger colony size and smoother appearance than the average transformed colony. Seven different transformants that continued to show signs of improved growth and colony morphology after restreaking on YPD plates were then examined for telomere length by Southern analysis. Two of these exhibited a complete loss of the long-telomere phenotype. Telomeres in these transformants remained short after additional passaging for maintenance of the library-derived plasmid (Fig. 3). However, upon plating these strains on plates containing 5-FOA, which selected for the loss of the library plasmid, we observed the highly elongated telomeres and rough-colony phenotypes resembling the original M1 mutant (Fig. 3). Our results suggested that the plasmids present in the transformants were responsible for rescuing the defect of the M1 mutant. After recovery of these complementing plasmids in Escherichia coli, both were found to contain ∼7.5-kb inserts and had identical restriction fragment patterns upon digestion with RsaI. As expected, retransformation of both the plasmids into the original M1 mutant was found to completely complement the mutation. One of the plasmids, p72, was selected for further sequencing.

FIG. 3.

The long telomeres of the M1 mutant are complemented by the K. lactis STN1 gene. Shown is a Southern blot of EcoRI-digested K. lactis genomic DNA from the M1 mutant hybridized to a telomere probe. The molecular size markers (M) are indicated in kb. The wild-type sample (WT) is shown on the first lane, followed by two passages (one or two streaks) of the M1 mutant. The next three lanes are independent M1 mutant clones shown shortly after transformation with a plasmid containing STN1 (+pSTN1). The last five lanes are individual clones of the M1 mutant shortly after losing the STN1-containing plasmid (−pSTN1).

To narrow down the complementing region of plasmid p72, an ∼2-kb XbaI-BspeI fragment was deleted to create pXB3. pXB3 was also found to fully complement the M1 mutant (data not shown). BLAST analysis of the insert sequence from the pXB3 plasmid revealed two intact open reading frames. One was identified as RRP8, encoding an rRNA processing protein. The other was identified as STN1, based on 28% identity and 47% similarity of its product to the sequence of the Stn1 protein of S. cerevisiae (Fig. 4). Further supporting our finding that the K. lactis gene was indeed a homologue of STN1, the two genes were not only the best matches to each other in their respective genomes but shared the same neighboring genes, RRP8 and PDC2 (data not shown). BLASTP searches using the two sequences revealed related protein products from other yeast species, one of which, from Candida glabrata, is shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Sequence analysis of K. lactis STN1 gene. Shown is an alignment of amino acid sequences of K. lactis (Kl) Stn1 with homologues from S. cerevisiae (Sc) and Candida glabrata (Cgl) (GenBank accession numbers P_38960 and XP_448655, respectively). The protein sequences were aligned in ClustalW using default values. Identical amino acids are shaded in black and marked with a star. Amino acids showing conserved substitutions are marked with two dots and shaded in gray, and semiconserved substitutions are shaded in light gray and marked with a single dot. The dark circle indicates the position of the mutation of the stn1-M1 mutant.

We used genomic DNA from the M1 mutant and its isogenic parent, 7B520, for PCR amplification of the K. lactis STN1 gene. Amplified products were purified and sequenced. Analysis revealed a single base substitution resulting in an isoleucine-to-lysine change at amino acid position 79 in the M1 mutant, but not in either the 7B520 parent or the STN1 gene in plasmid pXB3. The mutation in stn1-M1 is present in the region of its interaction with Ten1 (C. Nugent, personal communication). From our results we conclude that the phenotypes of the M1 mutant are due to this missense mutation, and we designate this allele stn1-M1.

Telomere shortening upon reintroduction of STN1 is very rapid in stn1-M1 cells.

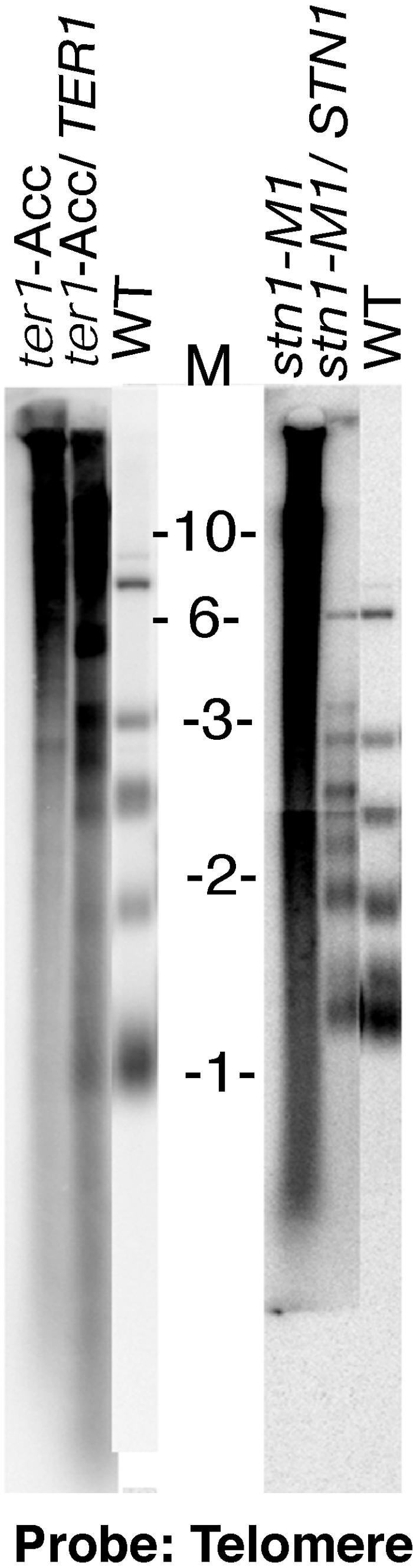

Previous work on numerous telomerase RNA gene (TER1) template mutants has produced extremely elongated telomeres superficially resembling the telomeres in the stn1-M1 mutant (31, 39, 56, 63). Reintroduction of a wild-type TER1 gene into these mutants rapidly eliminated the cellular defects and the highly smeared appearance of the telomere fragments but maintained very long telomeres. Only after hundreds of cell divisions did these long telomeres shorten to more-normal lengths. Gradual shortening is expected if telomeric sequence loss occurs primarily from incomplete replication of double-stranded DNA ends. It was therefore surprising that complementation of the stn1-M1 mutant rapidly shortened all the telomeres to nearly wild-type length without any trace of smears (Fig. 3). To further confirm this rapid sequence loss, we performed mating analysis using stn1-M1 and ter1-Acc(19A) strains, the latter a long-telomere ter1 template mutant capable of synthesizing telomeric repeats defective at binding the Rap1 protein (30, 39). Each of these strains was mated to three different wild-type strains of opposite mating type, and the telomere lengths from the resulting diploids were examined. Similar to previous published work (56), we observed that many telomeres in the TER1/ter1-Acc (19A) diploid cells were very long, similar to those of the ter1-Acc(19A) parent (Fig. 5A). In striking contrast, the stn1-M1/STN1 diploid cells had only telomeres of nearly normal length. This was true for each of the three independent diploids examined over 125 generations. This result confirmed that the long telomeres of the stn1-M1 mutant were shortened to nearly normal length within ∼30 cell divisions after reintroduction of a single copy of STN1.

FIG. 5.

Immediate shortening of the telomere occurs upon reintroduction of STN1. EcoR1-digested genomic DNA of stn1-M1/STN1 and ter1-Acc/TER1 diploids hybridized to a telomere probe. The diploids were generated by mating a wild-type K. lactis strain (see Materials and Methods) to the stn1-M1 strain and to a telomerase RNA gene template mutant (ter1-Acc) strain. The stn1-M1/STN1 diploid strain exhibits telomeres of approximately wild-type length immediately after mating (within ∼30 cell divisions), in contrast to the ter1-Acc/TER1 diploid, which retains long telomeres. Molecular size markers shown in the middle are in kb.

The long telomeres of the stn1-M1 strain are generated independently of telomerase.

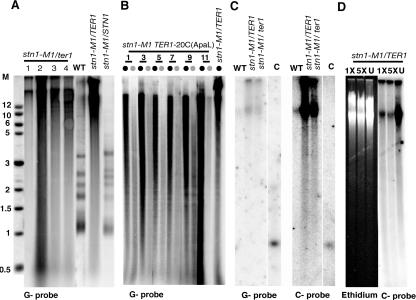

In S. cerevisiae, STN1 has been implicated as a negative regulator of telomerase by preventing Cdc13p-mediated telomerase recruitment (11, 22, 25, 50). Consistent with this, several mutant alleles isolated from different laboratories exhibited elongated telomeres that were formed in a telomerase-dependent manner. We therefore hypothesized that telomere elongation in the stn1-M1 mutant was mediated by telomerase. To address this, ter1-Δ stn1-M1 double mutants were constructed. Diploid strains constructed by mating between ter1-Δ and stn1-M1 haploid strains were found, as expected, to have telomeres of nearly normal length (data not shown). Tetrads were dissected from three independent diploid strains. Of the 44 dissected spores, we isolated five mutants displaying abnormal colonies and elongated telomeres resembling the haploid stn1-M1 strain. Southern analysis demonstrated that three of the five mutants were ter1-Δ stn1-M1 double mutants. These mutants did not display the declining growth senescence and survivor colony growth pattern characteristic of K. lactis ter1-Δ single mutants; instead they exhibited chronic abnormal growth and colony phenotypes indistinguishable from stn1-M1 single mutants (data not shown). Consistent with this, no change in telomere length was observed when stn1-M1 ter1-Δ cells were passaged over 200 cell divisions. Another ter1-Δ stn1-M1 double mutant was generated by a direct disruption of the TER1 gene in a stn1-M1 background (see Materials and Methods). This mutant strain also exhibited highly elongated telomeres and rough-colony morphology consistent with results from the mating analysis (Fig. 6A). From our results, we conclude that the telomere lengthening in the stn1-M1 mutant was independent of telomerase.

FIG. 6.

(A) Telomerase-independent lengthening in stn1-M1 mutants. Clones marked 1, 2, 3, and 4 are EcoR1-digested genomic DNA of stn1-M1 ter1-Δ double mutants hybridized to a telomeric G-strand probe (Klac1-25). The wild-type strain (WT), the stn1-M1 strain, and the parental stn1-M1/STN1 diploid are also shown. The different intensities of the telomeric signal between the stn1-M1 ter1-Δ clones is due to loading differences and possibly also strain differences. Molecular size markers (M) are in kb. (B) Telomerase remains active in stn1-M1 cells. Shown is a Southern blot of a time course of a clonal lineage of stn1-M1 containing a silent mutation in the telomerase RNA gene [TER1-20C (ApaL)]. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 represent the numbers of streaks after introduction of the TER1-20C (ApaL) gene, which generates a telomerase that synthesizes repeats with an ApaLI site. EcoRI (black circles)- and EcoRI-plus-ApaLI (gray circles)-digested genomic DNA of the individual streaks of stn1-M1 TER1-20C (ApaL) was hybridized to a G-strand telomere probe (Klac1-25). The last lane shows EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from the stn1-M1 TER1 control. The weaker intensity of the telomeric signal in the EcoRI-plus-ApaL1 lanes results from telomeric repeats with ApaLI sites that are cleaved. (C) Long 3′ overhangs in stn1-M1 cells. Shown is a nondenaturing in-gel hybridization of undigested genomic DNA of WT, stn1-M1, and stn1-M1 ter1-Δ strains. The left half of the panel has been hybridized to a G-strand telomeric probe, and the right panel shows the same set of samples probed with a C-strand telomeric probe. Lanes marked “C” are loading controls of a denatured plasmid fragment (∼3 kb) containing a K. lactis telomere. Molecular size markers (M) are in kb. (D) Exonuclease I (ExoI) digest of chromosomal DNA from stn1-M1 cells. The left half of the panel is the ethidium bromide-stained gel of genomic DNA from stn1-M1 cells. The lanes marked “1X” and “5X” represent relative amounts of ExoI used to treat genomic DNA from stn1-M1 cells. The lane marked “U” shows undigested genomic DNA. The right half of the panel represents the gel from the left panel hybridized to the C-strand telomere probe.

Telomerase is active in the stn1-M1 mutant.

To determine whether telomerase was still active in the stn1-M1 mutant, the native copy of the telomerase RNA gene TER1 was replaced with a mutant copy capable of adding telomere repeats with ApaLI restriction sites (TER1-20C [ApaL]) (63). The stn1-M1 TER1-20C (ApaL) strain was passaged for ∼220 to 275 generations (11 streaks on YPD plates), and genomic DNA from several passages was digested with EcoRI and ApaLI to probe for ApaLI-containing repeats in the long telomeres of the stn1-M1 mutant strain. Cleavage with ApaLI led to the shortening of telomeric fragments, which increased with progressive passaging (Fig. 6B). These results indicated the presence of a functional telomerase in the stn1-M1 mutant.

RAD52 is essential for the viability of stn1-M1 mutants.

To assess the role of recombination in telomere maintenance in the stn1-M1 mutant, we deleted the RAD52 gene, which is known to be involved in most homologous recombination events, in the stn1-M1 background. A haploid rad52 K. lactis strain was mated to the stn1-M1 strain, and the resulting diploids were sporulated. Twenty-three tetrads from six independent diploids were dissected. Of these, 21 tetrads exhibited a ratio of viable to nonviable spores of 2:0, and the other 2 tetrads exhibited a ratio of viable to nonviable spores of 2:1. Visual examination of the nonviable spores revealed growth arrest at the two- to four-cell stage. Southern hybridization analysis confirmed that the two morphologically abnormal clones were stn1-M1 RAD52 mutants. Thus no viable stn1-M1 rad52Δ isolates were identified by this method. We next performed an additional screen for stn1-M1 rad52Δ isolates by random spore analysis from the same parental diploids (see Materials and Methods). Of the 64 colonies examined, 8 rough colonies were identified and analyzed by Southern hybridizations. All of these clones proved to be stn1-M1 RAD52 single mutants. As expected, ∼50% of normally growing segregants were STN1 rad52 mutants. We therefore conclude that the stn1-M1 mutation is synthetically lethal in combination with the rad52 gene deletion. In other experiments, we attempted to directly disrupt RAD52 in mitotically growing stn1-M1 cells. No stn1-M1 rad52 double mutants were found from these experiments either.

The stn1-M1 strain contains long stretches of 3′ G-rich single-stranded DNA.

One of the consequences of telomere uncapping in yeast is the presence of extensive 3′ single-stranded overhangs due to excessive degradation of 5′ telomeric DNA (6, 20, 49, 63). We therefore analyzed stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ stn1-M1 mutants by nondenaturing in-gel hybridizations (15). Undigested genomic DNA from both the strains was electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel. When the gel was hybridized with the C-strand telomere oligonucleotide probe, a very strong signal was observed at limit mobility (>20 kb) and in the wells (Fig. 6C). In contrast, when the same samples were hybridized with the probe derived from the G-strand telomeric DNA, we observed a greatly diminished signal. By equilibrating the signal observed to the control denatured plasmid DNA, we estimate that there is ∼20- to 30-fold increase in single-stranded G-strand over single-stranded C-strand telomeric DNA in stn1-M1 and stn1-M1 ter1-Δ cells. The strong signal seen with the C-strand telomere probe was largely sensitive to digestion with the 3′-to-5′ single-strand exonuclease ExoI (Fig. 6D). These results are consistent with the stn1-M1 mutant having a capping defect resulting in large 3′ single-stranded overhangs. The ∼30% of the single-stranded G strand that was resistant to both 1× and 5× levels of ExoI presumably represents gapped regions of the telomeric DNA. Whether the signal visible with the G-strand telomere probe was from single-stranded DNA in the stn1-M1 samples or due to background hybridization to the large amount of double-stranded telomere DNA is unclear.

Telomeres in stn1-M1 cells exhibit high rates of subtelomeric recombination.

We have previously shown that K. lactis cells with abnormally short or highly elongated telomeres exhibit highly elevated rates of subtelomeric recombination (40, 63). We hypothesized that stn1-M1 cells would exhibit elevated recombination rates near the telomeres because of the importance of the RAD52 gene for their survival. To test this, we performed gene conversion assays to measure the subtelomeric recombination rates (40). Briefly, telomere DNA tagged with a subtelomeric URA3 marker was transformed into the stn1-M1 strain, where it replaced a single native telomere. Four transformants that were verified by Southern analysis to contain a single copy of the URA3 gene were used for the gene conversion assay (see Materials and Methods). The rates of URA3 loss due to gene conversion were then measured by plating serial dilutions of the cells on media containing 5-FOA as previously described (40). Our results indicate that URA3 loss was ∼5,000-fold elevated relative to a wild-type STN1 control (Table 1). To date this is the highest rate of subtelomere gene conversion observed among a variety of K. lactis mutants exhibiting dysfunctional telomeres (40, 63).

TABLE 1.

Elevated levels of recombination near telomeres in stn1-M1 cellsa

| STN1 allele | Gene conversion rate

|

Relative rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation rate ± SD | SE (n) | ||

| STN1 | 6.70 × 10−6 ± 2.70 × 10−5 | 7.90 × 10−6 (12) | 1.0 |

| stn1-M1 | 3.69 × 10−2 ± 2.54 × 10−2 | 6.87 × 10−3 (15) | ∼5,500 |

The subtelomeric gene conversion rates of stn1-M1 are based on measurements of five independent transformants of the stn1-M1 mutant containing the URA3 gene inserted near one telomere (see Materials and Methods). The assay for each clone was performed in triplicate. As controls, the values for the wild-type STN1 clones have been cited from previously published results (40). The standard error was calculated as the standard deviation divided by the square root of n, the number of samples assayed for each strain.

DISCUSSION

The stn1-M1 mutant has a telomere cap defect.

The Stn1 protein of S. cerevisiae is part of the trimeric complex that binds the single-stranded 3′ telomeric overhangs and is known to be involved both in the protective capping function of telomeres and in regulating telomerase's ability to lengthen telomeres (11, 22, 25, 50). This is the first study of a mutant allele of STN1 in K. lactis. A variety of evidence indicates that the stn1-M1 mutation causes a defect in the protective capping function of telomeres. The extremely long telomeres of stn1-M1 cells clearly indicate the presence of a defect in telomere length regulation. The abnormal colony and cellular morphologies of the stn1-M1 mutant resemble those of early-senescing yeast telomerase deletion mutants as well as certain telomerase TER1 template mutants with extremely long telomeres (38, 39, 56). This suggests that the telomeres of stn1-M1 cells often trigger DNA damage checkpoints, similar to senescing cells lacking telomerase (29a). Another sign of a telomere capping defect in stn1-M1 cells is the long tracts of single-stranded telomeric DNA, specifically of the 3′ G-rich strand, consistent with degradation of the 5′ strand of the telomere. Studies with S. cerevisiae have shown that single-strand degradation from the 5′ end occurs at double-strand breaks and at telomeres with certain capping defects (6, 20, 65). As 3′ single-stranded DNA is a potent initiator of homologous recombination, it is not surprising that we also observe highly elevated levels of recombination near the telomeres of stn1-M1 cells. Additionally, the presence of occasional sharp bands seen with a subtelomere-specific probe (Fig. 1B) might suggest that fusions may sometimes occur in stn1-M1 mutant cells, perhaps only after the loss of telomeric repeats. Overall, our data suggest that Stn1 protects telomeres against initiating homologous recombination events. This protection might occur directly through the interaction of the Stn1/Cdc13/Ten1 complex with telomeric DNA (18), or it might occur indirectly through the ability of Cdc13 and Stn1 to interact with components of DNA polymerase α/primase, which leads to synthesis of the C-rich strand at 3′ G-strand telomeric overhangs (27, 53). It is possible that the role of Stn1 in protecting against telomeric recombination is mediated largely or entirely in the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle, as this is when the 3′ overhangs are most pronounced (15). Also, recent evidence suggests that double-strand break repair during S/G2 is usually mediated by homologous recombination while repair during G1 is mainly mediated by nonhomologous end joining (19).

Chronic uncapping triggers runaway RTE in stn1-M1 cells.

Although both stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ mutants can maintain telomeres by recombination, they are very different in important ways. A striking difference is in the extent of telomere elongation between stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ survivor cells. stn1-M1 cells have telomeres that are many kilobases in length, while ter1-Δ survivors seldom have telomeres longer than several hundred base pairs (38). Secondly, stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ cells differ in growth characteristics. ter1-Δ cells display a progressive growth senescence to a point where most cells are dead or very poorly growing (38). After RTE has lengthened telomeres, growth is improved, with survivors often temporarily displaying growth characteristics indistinguishable from wild-type cells. This recovery is followed by irregular cycles of additional senescence and growth improvement brought on by the fluctuating and often very short lengths of the telomeres. In contrast, stn1-M1 cells exhibit a chronic growth defect reminiscent of moderately senescent ter1-Δ cells. This growth defect is stably maintained between different growth passages over long periods of time. The two mutants also differ in their responses to the deletion of genes involved in homologous recombination. In stn1-M1 cells, deletion of RAD52 leads to immediate lethality. In contrast, in a ter1-Δ mutant strain, lethality also occurs, but only after >50 cell divisions. Additionally, we have observed that deletion of RAD59, a gene homologous to RAD52, kills or severely affects the growth of stn1-M1 cells but does not severely affect the growth or formation of survivors in the ter1-Δ background (S. Iyer and M. J. McEachern, unpublished data).

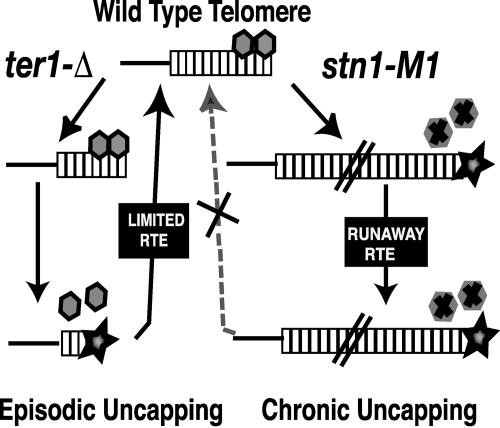

We propose that the differences between stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ cells result from fundamentally different types of telomere capping defects. As shown in the model in Fig. 7, ter1-Δ cells can be viewed as having a capping defect that is episodic in nature (Fig. 7, left). Recent work in our laboratory has shown that telomeres in ter1-Δ cells are able to recombine only once they have shortened to less than ∼4 repeats (100 bp) in size (62). This predicts that, once a telomere is lengthened by RTE to a size appreciably above this length, it effectively becomes recapped and resistant to initiating further recombination events. If all telomeres become lengthened and recapped, the cell can grow normally until one or more telomeres again shorten to below ∼100 bp. Telomere length can become kilobases long in “type II” survivors of yeast cells lacking telomerase. However, this is thought to be triggered by rolling-circle replication events that generate a long telomere in a single step (34, 46). In this circumstance, where uncapping is episodic, RTE is inherently self-limiting.

FIG. 7.

Two types of RTE in K. lactis. (Left) In the absence of telomerase (ter1-Δ), a telomere capping defect producing a state prone to initiating recombination (black star) occurs only once telomeres have dropped below ∼100 bp in length, presumably due to the inadequate presence of telomere capping proteins (gray hexagons). Once RTE lengthens telomeres above their critical length, they become recapped and resistant to additional elongation by recombination. The capping-defective telomere state, prone to initiating recombination, is thus episodic, and the extent of telomere elongation is limited. (Right) In the stn1-M1 mutant, a defective capping protein may cause a chronic capping defect that leaves telomeres prone to initiating recombination in a manner largely or entirely independent of telomere length. This produces runaway RTE (type IIR RTE). See text for details.

However, we hypothesize that, in stn1-M1 cells, the capping defect is chronic and partly or entirely independent of the initial length of the telomere (Fig. 7, right). Recombination events that produce abnormally long telomeres in stn1-M1 cells cannot restore normal telomere functionality due to the continued presence of the dysfunctional Stn1 protein. Thus even the longest telomere in stn1-M1 cells may be capable of initiating recombinational repair and undergoing RTE.

The RTE-producing moderate elongation of telomere repeat tracts in yeast mutants lacking telomerase has been termed “type II” (12, 59). Since the telomere elongation of stn1-M1 cells appears to consist only of elongated telomeric repeat tracts, it could also be described as type II RTE. However, given the fundamental differences between RTE in stn1-M1 and ter1-Δ cells, especially in terms of telomere length, we propose that RTE observed in stn1-M1 cells be called type IIR for producing runaway telomere elongation. We would define type IIR RTE as extreme telomere elongation by recombination resulting from a chronic telomere capping defect that is largely or entirely independent of telomere length. By this definition, the moderate telomere elongation caused by recombination in S. cerevisiae cdc13-1 cells under certain conditions might qualify as a less extreme example of type IIR RTE (21, 23) because telomeres of nearly normal size can become elongated by recombination. Also, as discussed below, the telomere maintenance in human ALT cells is certainly a candidate for being type IIR RTE.

The mechanistic similarities and differences between type II RTE in ter1-Δ cells and the type IIR RTE of stn1-M1 cells still remain to be determined. Accumulating evidence indicates that the type II RTE in ter1-Δ cells occurs through a roll-and-spread mechanism, whereby the first long telomere is generated by copying a telomeric circle of ∼100 bp and all other telomeres are elongated by directly or indirectly copying that telomere (45, 46). It is difficult to predict the role of telomeric circles in type IIR RTE. One possibility is that the long telomeres in stn1-M1 cells could arise from intertelomeric recombination without the need of DNA circles. However, if relatively large circles are present in stn1-M1 cells, they could be potent templates for generating long telomeric repeat tracts through rolling-circle events. Therefore a reasonable prediction is that telomeric circles are not essential to type IIR RTE but may be important contributors to it.

An interesting feature of the stn1-M1 mutant (and perhaps a general characteristic of type IIR RTE) is its apparent ability to undergo RTE in the presence of an active telomerase. A question that then arises is why are stn1-M1 rad52 cells nonviable, if they can utilize telomerase to maintain chromosome ends? We suggest that the essential role of recombination in stn1-M1 cells stems from a function that cannot be replaced by telomerase. One possibility is that recombination is needed to repair chromosome ends that have lost all telomeric repeats. The very high loss rate of a subtelomeric URA3 gene indeed suggests that recombinational repair very frequently involves subtelomeric sequences in stn1-M1 cells. A second possibility is that recombination is required to antagonize the production of single-stranded telomeric DNA. The accumulation of 5 to 10 kb of single-stranded DNA is thought to be sufficient to arrest yeast cell growth (58). The repair DNA synthesis that is initiated from strand invasion or possibly the strand invasion itself might act to counteract the cell cycle arrest signal produced by single-stranded DNA.

Is STN1 a regulator of TRD?

A striking feature of the stn1-M1 mutant is the rapid loss of its long telomeres upon reintroduction of STN1 (Fig. 3 and 5A). This is very different from a number of other instances where abnormally elongated telomeres are introduced into cells that otherwise maintain shorter telomeres (31, 33, 56, 69). In these cases, the long telomeres commonly remain long for protracted periods of growth. However, sudden telomere shortening events attributed to processes other than incomplete replication have been observed in a number of circumstances (37). Especially well documented are TRD events that occur in S. cerevisiae (8, 33). Most TRD events are RAD52 and MRE-11 dependent and are thought to be intrastrand recombination events resulting in terminal deletions (37). While its underlying mechanism is unclear, the rapid telomere shortening we report here may represent the most extreme example of TRD reported so far.

Both the presence of very long telomeres formed independently of telomerase and the very high rate of subtelomeric gene conversion indicate that the telomeres in stn1-M1 mutants undergo very high levels of recombination. It is quite likely that RTE and TRD in stn1-M1 cells could result from the same recombination pathway initiated at a telomere. Our data suggest that Stn1 acts to inhibit telomeres from engaging in recombination events in general, but also that it differentially affects RTE and TRD. The presence of long telomeres indicates that telomere lengthening predominates over telomere shortening in stn1-M1 cells. In contrast, reintroduction of STN1 into stn1-M1 cells does not simply complement defects caused by the mutant stn1 gene and freeze telomeres at long sizes as might be expected. Instead, telomere deletion events clearly predominate over RTE events, leading to dramatic telomere shortening of all 12 telomeres. It is not currently known whether these TRD events occur within a single cell division or whether they occur more gradually over many cell divisions.

How Stn1p influences the extensive TRD events observed undoubtedly depends on the mechanism by which it caps and protects telomeres. The Cdc13p/Stn1p/Ten1p complex bound to the single-strand telomeric overhang may prevent the 3′ overhang from engaging in any strand invasion into other telomeric repeats. An additional possibility is that the Stn1 complex may affect the outcome of 3′ overhangs that are already engaged in an intrastrand invasion, perhaps by binding to the displaced DNA loop. This might explain how reintroducing STN1 into stn1-M1 cells blocks RTE while continuing to permit TRD events in the cell. However, we cannot yet rule out the possibility that the rapid telomere shortening in stn1-M1 cells arises due to recombination-independent events.

Parallels between stn1-M1 and human ALT cells.

The phenotypes of stn1-M1 cells are in many ways strikingly similar to mammalian ALT cells. The most obvious similarity between stn1-M1 and ALT cells is in the very long and heterogeneous telomeres that are produced by recombination. Also, the RTE pathways observed in both stn1-M1 and ALT cells are genetically recessive (51, 52). Another similarity of ALT cells and stn1-M1 cells is that both exhibit a mixture of healthy and senescent cells (28, 55). This is suggestive of both having chronic telomere capping defects that can often trigger growth arrests. Like stn1-M1 cells, ALT cells appear to have elevated levels of telomere recombination (17). Additionally, the presence of telomeric DNA, telomeric proteins, and a growing list of recombination proteins in ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies also suggested the importance of recombination in the ALT pathway (28). So far, APBs have not been identified in yeast species. Other similarities between ALT and stn1-M1 cells are that both are able to produce telomeric circles (t circles) and that RTE can occur in the presence of telomerase (10; S. Iyer, A. Cesare, E. Basenko, J. Griffith, and M. McEachern, unpublished data). Whether t circles contribute to RTE in either case is not known. It is currently unclear whether ALT cells, like stn1-M1 cells, produce at least some telomeres with long 3′ overhangs. Rapid telomere shortening reminiscent of TRD has also been observed in ALT cells (37, 43, 51, 52). The mechanisms triggering such deletion events in ALT and stn1-M1 cells still remain to be determined. Thus, both ALT cells and stn1-M1 cells share many traits consistent with their telomeres having chronic capping defects and being very frequently engaged in recombinational repair.

An obvious possibility suggested by our work is that the phenotype of ALT cells could arise from mutations in genes encoding proteins that are components of the single-stranded DNA binding complex. Although a human homologue of STN1 has not been yet identified, one of the several proteins interacting with hPOT1 (part of the TRF complex) is a potential candidate for being a functional ortholog of STN1 (35, 57, 67). Another exciting implication of our results arises from the extreme sensitivity of stn1-M1 to the absence of RAD52. This could imply that ALT-positive cells may be much more sensitive to recombination inhibitors than normal cells. We conclude that stn1-M1 is an excellent model for understanding how telomere capping defects can trigger both RTE and TRD. Further studies of stn1-M1 should therefore provide many additional important insights and lead to a better understanding of these mechanisms in yeast and other organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joris Heus for the gift of the K. lactis library plasmid. We also thank Dana Underwood, MGIF, Nicole Fitzpatrick, and Travis Duckworth for their assistance in the TER1-20C (ApaL) strain construction, gene sequencing, EMS screen, and the subtelomere gene conversion assay.

This work was supported by grant from the National Institute of Health (GM 61645-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumann, P., and T. R. Cech. 2001. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science 292:1171-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Porath, I., and R. A. Weinberg. 2004. When cells get stressed: an integrative view of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Investig. 113:8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman, J., C. Y. Tachibana, and B. K. Tye. 1986. Identification of a telomere-binding activity from yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:3713-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasco, M. A. 2004. Carcinogenesis Young Investigator Award. Telomere epigenetics: a higher-order control of telomere length in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 25:1083-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodnar, A. G., M. Ouellette, M. Frolkis, S. E. Holt, C. P. Chiu, G. B. Morin, C. B. Harley, J. W. Shay, S. Lichtsteiner, and W. E. Wright. 1998. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science 279:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth, C., E. Griffith, G. Brady, and D. Lydall. 2001. Quantitative amplification of single-stranded DNA (QAOS) demonstrates that cdc13-1 mutants generate ssDNA in a telomere to centromere direction. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:4414-4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan, T. M., A. Englezou, L. Dalla-Pozza, M. A. Dunham, and R. R. Reddel. 1997. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat. Med. 3:1271-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucholc, M., Y. Park, and A. J. Lustig. 2001. Intrachromatid excision of telomeric DNA as a mechanism for telomere size control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6559-6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cervantes, R. B., and V. Lundblad. 2002. Mechanisms of chromosome-end protection. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cesare, A. J., and J. D. Griffith. 2004. Telomeric DNA in ALT cells is characterized by free telomeric circles and heterogeneous t-loops. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:9948-9957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra, A., T. R. Hughes, C. I. Nugent, and V. Lundblad. 2001. Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev. 15:404-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Q., A. Ijpma, and C. W. Greider. 2001. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1819-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Church, G. M., and W. Gilbert. 1984. Genomic sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen, S., and M. Mechali. 2002. Formation of extrachromosomal circles from telomeric DNA in Xenopus laevis. EMBO Rep. 3:1168-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bruin, D., S. M. Kantrow, R. A. Liberatore, and V. A. Zakian. 2000. Telomere folding is required for the stable maintenance of telomere position effects in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7991-8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dionne, I., and R. J. Wellinger. 1996. Cell cycle-regulated generation of single-stranded G-rich DNA in the absence of telomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13902-13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuBois, M. L., Z. W. Haimberger, M. W. McIntosh, and D. E. Gottschling. 2002. A quantitative assay for telomere protection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161:995-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunham, M. A., A. A. Neumann, C. L. Fasching, and R. R. Reddel. 2000. Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nat. Genet. 26:447-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans, S. K., and V. Lundblad. 2000. Positive and negative regulation of telomerase access to the telomere. J. Cell Sci. 113:3357-3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira, M. G., K. M. Miller, and J. P. Cooper. 2004. Indecent exposure: when telomeres become uncapped. Mol. Cell 13:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garvik, B., M. Carson, and L. Hartwell. 1995. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6128-6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grandin, N., and M. Charbonneau. 2003. The Rad51 pathway of telomerase-independent maintenance of telomeres can amplify TG1-3 sequences in yku and cdc13 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3721-3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2000. Cdc13 cooperates with the yeast Ku proteins and Stn1 to regulate telomerase recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8397-8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2001. Cdc13 prevents telomere uncapping and Rad50-dependent homologous recombination. EMBO J. 20:6127-6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2001. Ten1 functions in telomere end protection and length regulation in association with Stn1 and Cdc13. EMBO J. 20:1173-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandin, N., S. I. Reed, and M. Charbonneau. 1997. Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev. 11:512-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith, J. D., L. Comeau, S. Rosenfield, R. M. Stansel, A. Bianchi, H. Moss, and T. de Lange. 1999. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell 97:503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Groff-Vindman, C., A. J. Cesare, S. Natarajan, J. D. Griffith, and M. J. McEachern. 2005. Recombination at long mutant telomeres produces tiny single- and double-stranded telomeric circles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:4406-4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Grossi, S., A. Puglisi, P. V. Dmitriev, M. Lopes, and D. Shore. 2004. Pol12, the B subunit of DNA polymerase alpha, functions in both telomere capping and length regulation. Genes Dev. 18:992-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henson, J. D., A. A. Neumann, T. R. Yeager, and R. R. Reddel. 2002. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in mammalian cells. Oncogene 21:598-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heus, J. J., B. J. Zonneveld, H. Y. Steensma, and J. A. Van den Berg. 1990. Centromeric DNA of Kluyveromyces lactis. Curr. Genet. 18:517-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.IJpma, A. S., and C. W. Greider. 2003. Short telomeres induce a DNA damage response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:987-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Krauskopf, A., and E. H. Blackburn. 1996. Control of telomere growth by interactions of RAP1 with the most distal telomeric repeats. Nature 383:354-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krauskopf, A., and E. H. Blackburn. 1998. Rap1 protein regulates telomere turnover in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12486-12491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson, D. D., E. A. Spangler, and E. H. Blackburn. 1987. Dynamics of telomere length variation in Tetrahymena thermophila. Cell 50:477-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, B., and A. J. Lustig. 1996. A novel mechanism for telomere size control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 10:1310-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin, C.-Y., H.-H. Chang, K.-J. Wu, S.-F. Tseng, C.-C. Lin, C.-P. Lin, and S.-C. Teng. 2005. Extrachromosomal telomeric circles contribute to Rad52-, Rad50-, and polymerase δ-mediated telomere-telomere recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 4:327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, D., A. Safari, M. S. O'Connor, D. W. Chan, A. Laegeler, J. Qin, and Z. Songyang. 2004. PTOP interacts with POT1 and regulates its localization to telomeres. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:673-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1-senescence. Cell 73:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lustig, A. J. 2003. Clues to catastrophic telomere loss in mammals from yeast telomere rapid deletion. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEachern, M. J., and E. H. Blackburn. 1996. Cap-prevented recombination between terminal telomeric repeat arrays (telomere CPR) maintains telomeres in Kluyveromyces lactis lacking telomerase. Genes Dev. 10:1822-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McEachern, M. J., and E. H. Blackburn. 1995. Runaway telomere elongation caused by telomerase RNA gene mutations. Nature 376:403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McEachern, M. J., and S. Iyer. 2001. Short telomeres in yeast are highly recombinogenic. Mol. Cell 7:695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McEachern, M. J., S. Iyer, T. B. Fulton, and E. H. Blackburn. 2000. Telomere fusions caused by mutating the terminal region of telomeric DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11409-11414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEachern, M. J., A. Krauskopf, and E. H. Blackburn. 2000. Telomeres and their control. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:331-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murnane, J. P., L. Sabatier, B. A. Marder, and W. F. Morgan. 1994. Telomere dynamics in an immortal human cell line. EMBO J. 13:4953-4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murti, K. G., and D. M. Prescott. 1999. Telomeres of polytene chromosomes in a ciliated protozoan terminate in duplex DNA loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14436-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natarajan, S., C. Groff-Vindman, and M. J. McEachern. 2003. Factors influencing the recombinational expansion and spread of telomeric tandem arrays in Kluyveromyces lactis. Eukaryot Cell. 2:1115-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natarajan, S., and M. J. McEachern. 2002. Recombinational telomere elongation promoted by DNA circles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4512-4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nickles, K., and M. J. McEachern. 2004. Characterization of Kluyveromyces lactis subtelomeric sequences including a distal element with strong purine/pyrimidine strand bias. Yeast 21:813-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikitina, T., and C. L. Woodcock. 2004. Closed chromatin loops at the ends of chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 166:161-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nugent, C. I., T. R. Hughes, N. F. Lue, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pennock, E., K. Buckley, and V. Lundblad. 2001. Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell 104:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perrem, K., T. M. Bryan, A. Englezou, T. Hackl, E. L. Moy, and R. R. Reddel. 1999. Repression of an alternative mechanism for lengthening of telomeres in somatic cell hybrids. Oncogene 18:3383-3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrem, K., L. M. Colgin, A. A. Neumann, T. R. Yeager, and R. R. Reddel. 2001. Coexistence of alternative lengthening of telomeres and telomerase in hTERT-transfected GM847 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3862-3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qi, H., and V. A. Zakian. 2000. The Saccharomyces telomere-binding protein Cdc13p interacts with both the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase alpha and the telomerase-associated est1 protein. Genes Dev. 14:1777-1788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reddel, R. R., T. M. Bryan, and J. P. Murnane. 1997. Immortalized cells with no detectable telomerase activity. A review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 62:1254-1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogan, E. M., T. M. Bryan, B. Hukku, K. Maclean, A. C. Chang, E. L. Moy, A. Englezou, S. G. Warneford, L. Dalla-Pozza, and R. R. Reddel. 1995. Alterations in p53 and p16INK4 expression and telomere length during spontaneous immortalization of Li-Fraumeni syndrome fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4745-4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith, C. D., and E. H. Blackburn. 1999. Uncapping and deregulation of telomeres lead to detrimental cellular consequences in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 145:203-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smogorzewska, A., and T. de Lange. 2004. Regulation of telomerase by telomeric proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:177-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sogo, J. M., M. Lopes, and M. Foiani. 2002. Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science 297:599-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teng, S. C., and V. A. Zakian. 1999. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8083-8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tomaska, L., J. Nosek, A. M. Makhov, A. Pastorakova, and J. D. Griffith. 2000. Extragenomic double-stranded DNA circles in yeast with linear mitochondrial genomes: potential involvement in telomere maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4479-4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomaska, L., S. Willcox, J. Slezakova, J. Nosek, and J. D. Griffith. 2004. Taz1 binding to a fission yeast model telomere: formation of telomeric loops and higher order structures. J. Biol. Chem. 279:50764-50772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Topcu, Z., K. Nickles, C. Davis, and M. J. McEachern. 2005. Abrupt disruption of capping and a single source for recombinationally elongated telomeres in Kluyveromyces lactis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3348-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Underwood, D. H., C. Carroll, and M. J. McEachern. 2004. Genetic dissection of the Kluyveromyces lactis telomere and evidence for telomere capping defects in TER1 mutants with long telomeres. Eukaryot Cell. 3:369-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vermeesch, J. R., D. Williams, and C. M. Price. 1993. Telomere processing in Euplotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:5366-5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White, C. I., and J. E. Haber. 1990. Intermediates of recombination during mating type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 9:663-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wray, L. V., Jr., M. M. Witte, R. C. Dickson, and M. I. Riley. 1987. Characterization of a positive regulatory gene, LAC9, that controls induction of the lactose-galactose regulon of Kluyveromyces lactis: structural and functional relationships to GAL4 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:1111-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ye, J. Z., J. R. Donigian, M. van Overbeek, D. Loayza, Y. Luo, A. N. Krutchinsky, B. T. Chait, and T. de Lange. 2004. TIN2 binds TRF1 and TRF2 simultaneously and stabilizes the TRF2 complex on telomeres. J. Biol. Chem. 279:47264-47271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye, J. Z., D. Hockemeyer, A. N. Krutchinsky, D. Loayza, S. M. Hooper, B. T. Chait, and T. de Lange. 2004. POT1-interacting protein PIP1: a telomere length regulator that recruits POT1 to the TIN2/TRF1 complex. Genes Dev. 18:1649-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu, L., K. S. Hathcock, P. Hande, P. M. Lansdorp, M. F. Seldin, and R. J. Hodes. 1998. Telomere length regulation in mice is linked to a novel chromosome locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8648-8653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]