ABSTRACT

This case described a 25‐year‐old pregnant woman with refractory multifocal epilepsy, diagnosed in 2020 and treated with bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting the centromedian and pulvinar nuclei. Prior to DBS, she experienced daily focal seizures, often progressing to generalized tonic–clonic seizures despite optimal medication. Presurgical evaluations revealed multifocal epilepsy with right hemispheric involvement and diffuse band heterotopia. Given the extensive neurophysiological and radiographic findings, DBS was chosen over resective surgery. Following implantation in December 2023, initial stimulation settings resulted in some seizure control but also development of new symptoms, including shock‐like sensations down her neck. After 43 seizure‐free days, she experienced a prolonged seizure in April 2024, prompting further investigation. Imaging revealed migration of the right pulvinar electrode, which was identified as the likely cause. This resultant displacement, called the “Twiddler's Syndrome,” is a phenomenon where device manipulation causes malfunction or dislodgment. This resulted from the patient's habit of massaging her neck. After adjusting DBS settings and turning off right pulvinar stimulation, her symptoms resolved, and she remained seizure‐free for two months. This case emphasizes the need for careful postimplantation monitoring, imaging, and awareness of hardware‐related issues like Twiddler's Syndrome, highlighting the importance of well‐planned surgical strategies to optimize outcomes in neuromodulation therapies.

Keywords: deep brain stimulation, epilepsy, hardware complications, lead migration, neuromodulation, seizure semiology, Twiddler's syndrome

1. Introduction

DBS is an emerging therapy for patients with refractory epilepsy, particularly when resective surgery is not an option due to diffuse or multifocal pathology [1]. While DBS has shown efficacy in reducing seizure burden with respect to frequency and intensity, recurrent or altered seizure symptoms/auras may result from postoperative changes (e.g., hemorrhage, inflammation, or infection), medication adjustments, psychological factors, or hardware issues such as suboptimal DBS settings, electrode displacement, or device malfunction. Neurotransmitter imbalances and de‐novo epileptogenesis may also influence symptoms [1, 2, 3]. Here, we present a case of Twiddler's syndrome and outline some essentials of following up a patient who has recently undergone implantation of a neurostimulation device.

Twiddler's syndrome is a rare but significant complication of implantable devices, including pacemakers and DBS systems [4]. It results from repeated unintentional manipulation of the device, leading to lead displacement and subsequent dysfunction [4, 5]. Understanding the risk factors, diagnostic indicators, and management strategies for this syndrome is essential to optimizing patient outcomes and ensuring DBS efficacy.

2. Case Presentation

A 25‐year‐old woman, at 11 weeks gestation, with a history of refractory multifocal epilepsy presented with a new‐onset shock sensation in her neck in April 2024. She had been diagnosed in 2020 and suffered from daily focal impaired awareness seizures, often preceded by vertiginous aura, nausea, headache, and dizziness. Every two months, these focal seizures progressed to generalized tonic–clonic (GTC) seizures despite maximal doses of oxcarbazepine and levetiracetam. The frequency and severity of her seizures significantly impaired her quality of life, necessitating consideration of surgical intervention.

Pre‐DBS evaluation included prolonged video EEG (VEEG) monitoring, which demonstrated multifocal epilepsy with significant right hemispheric involvement, predominantly in the parieto‐occipital region. MRI revealed diffuse band heterotopia, a malformation of cortical development. Genetic testing identified a heterozygous DCX mutation, which is associated with neuronal migration disorders. Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and PET scans corroborated the multifocal epileptic activity, predominantly in the right hemisphere (Figure 1). Given the nonlocalized nature of her epilepsy, she was deemed unsuitable for resective surgery. Instead, DBS targeting the bilateral centromedian and pulvinar nuclei was selected as an alternative neuromodulatory approach to reduce seizure burden.

FIGURE 1.

Phase I presurgical evaluation shows multifocal interictal epileptiform activity, primarily from the right temporo‐parieto‐occipital region, with less frequent origins in the right fronto‐central and left temporal regions. (A) MRI shows bilateral gray matter band heterotopia in posterior quadrant peri‐occipital horn and left hippocampal sclerosis. (B) MEG localized discharges to left superior temporal gyrus, left temporal operculum, right parieto‐occipital region, right superior temporal sulcus, and right parietal operculum. (C) PET showed hypometabolism in the right superior temporal sulcus depth. (STS). (G, H, I) VEEG shows independent interictal sharp waves in right frontal‐central, temporal, and parieto‐occipital regions. (J, K) Seizures originated in the right hemisphere with rhythmic fast activity in the right mid‐temporal region. To modulate multifocal epileptiform circuits, bilateral centromedian (CM) and medial pulvinar (mPUL) nuclei were implanted. (D, E). The images reconstructed from a CT scan taken in December 2023 show that all the targets were in place. (F) Twiddler syndrome: A February 2024 CT showed DBS‐lead auto‐explantation caused by repetitive manipulation, leading to subcutaneous twisting, shortening of cable length, and migration of the right pulvinar electrode to the temporo‐occipital junction.

In December 2023, the patient received two thalamic Percept DBS implants targeting the bilateral centromedian and pulvinar nuclei. Initial stimulation parameters were continuous stimulation at 125 Hz, 90 μs, and 0.2 mA in the bilateral centromedian nuclei (pulvinar off). Following device activation, she experienced a significant reduction in seizure frequency, achieving an Engel 1B outcome (ILAE score 2). Given her initial positive response, stimulation parameters were adjusted to include 0.3 mA in the bilateral pulvinar nuclei and 0.3 mA (left) and 0.4 mA (right) in the centromedian nuclei.

By February 2024, the patient reported intermittent headaches and began massaging her neck frequently, particularly near the device site. Concurrently, she developed new symptoms, including shock‐like sensations extending from the left neck to the chest. This was unusual in her prior seizure history. After 43 consecutive seizure‐free days, she experienced a prolonged seizure in April 2024 that required rescue medication.

Seizure semiology and auras often provide insight into the cortical region involved in epileptogenesis [6]. Given the change in symptoms post‐DBS implantation, the differential diagnosis included ineffective DBS targeting, new epileptogenesis, or hardware‐related complications such as lead displacement or malfunction [7].

To assess potential device‐related complications, DBS settings and positioning were evaluated. A comprehensive imaging workup, including head and neck CT with two‐view X‐rays, was performed. The December 2023 scan confirmed correct electrode placement. However, a comparison with the February 2024 scan revealed migration of the right pulvinar electrode to the posterior temporal region. This finding, initially overlooked during routine radiological review, was identified upon focused re‐evaluation by the treating team.

3. Discussion

DBS lead migration can result from mechanical stress, improper fixation, or patient‐related behaviors. The primary differential diagnoses for this patient included (1) lead fixation failure—considered unlikely due to the use of cranial plating and shunt tubing fixation at the time of implantation, (2) cervical dystonia or excessive movement—typically associated with ventral migration rather than dorsal electrode displacement, and (3) Twiddler's syndrome—The most probable cause, given the patient's repetitive habit of massaging her neck over the implanted device [4, 5, 8].

Twiddler's syndrome was first described by Bayliss et al. in 1968 in the context of cardiac pacemakers [4]. It has since been recognized in DBS patients, with the first reported case in 2009 by Morishita et al. [5]. Patients with Twiddler's syndrome often unknowingly manipulate their implanted devices, causing lead displacement and subsequent clinical deterioration [8, 9, 10].

Due to the patient's pregnancy, surgical intervention to reposition the displaced electrode was deferred. Instead, a conservative management strategy was adopted. Right pulvinar stimulation was discontinued to prevent further unintended cortical activation. The patient was advised to avoid neck massage and other repetitive movements over the device area. Bilateral centromedian stimulation was increased to 0.5 mA (left) and 0.6 mA (right) to optimize seizure control. At her most recent follow‐up, she had remained seizure‐free for two months.

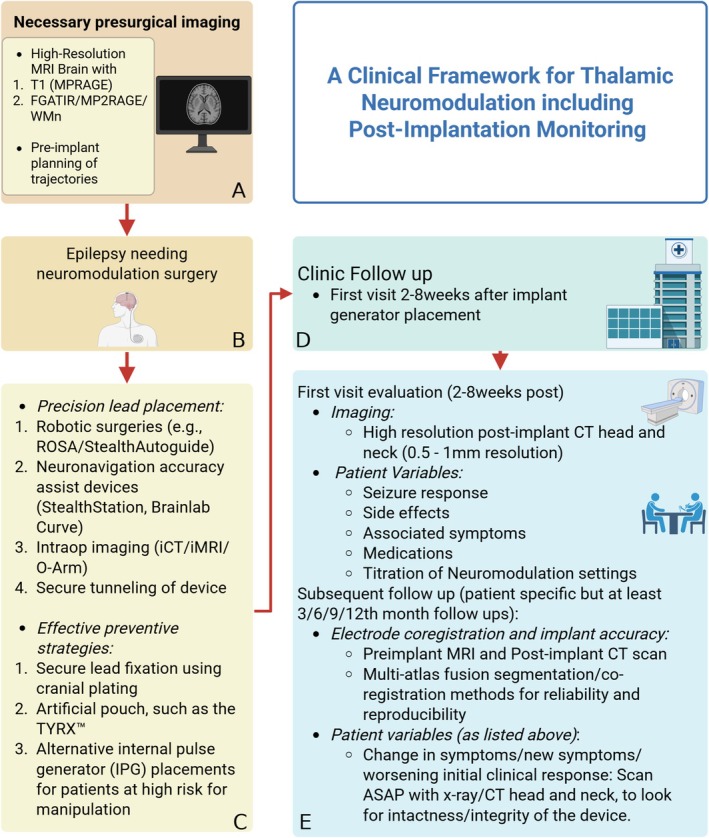

Regarding neuromodulation care and preventive strategies for Twiddler's Syndrome, it is paramount to emphasize safe and preventive surgical practices, implant accuracy, hardware care, routine monitoring and clinic follow‐up, battery health and replacement, and standardized clinical reporting protocols (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

A clinical framework for thalamic neuromodulation including postimplantation monitoring. (A) Preimplantation evaluation and target selection: Multimodal workup including prolonged VEEG, MRI, PET, and MEG is used to confirm seizure laterality and localization. Patients who eventually get identified as candidates appropriate for neuromodulation should undergo MRI epilepsy protocol (usually of high resolution with 1‐2 mm slice thickness and no interslice gap) with specific sequences such as FGATIR/MP2RAGE/WM‐nulled. These sequences provide the tissue contrast that help delineate the different thalamic nuclei and also allow for auto‐segmentation algorithms to define patient specific thalamic atlas (https://github.com/thalamicseg/thomas_new). (B, C) Surgical lead placement and strategies to prevent lead or device displacement: Intraoperative techniques to ensure optimal lead positioning and stability include robotic surgeries and accuracy assist devices. Emphasis is placed on accurate stereotactic targeting, intraoperative verification of lead placement, and secure fixation of hardware. Cranial lead anchoring using titanium plating and creation of a stable subcutaneous pocket for the implantable pulse generator are employed to minimize the risk of postoperative lead migration or hardware malfunction. (D, E) Postimplantation surveillance and symptom reassessment: A structured follow‐up protocol is essential to monitor patient's response to neuromodulation therapy. This includes routine imaging (e.g., CT, X‐ray) to detect hardware complications such as Twiddler's syndrome, and detailed clinical correlation of new or atypical symptoms (e.g., shock sensations, prolonged seizures) with device function and lead positioning. Initial programming and clinical response assessment: Postimplant activation of DBS includes titration of stimulation parameters (e.g., amplitude, frequency, pulse width) to optimize seizure control while minimizing stimulation‐related side effects. Early programming must be aligned with baseline seizure semiology to identify meaningful clinical changes. Management of hardware‐related complications and longitudinal care: Upon diagnosis of lead migration or device malfunction, conservative or surgical interventions may be considered based on patient status (e.g., in this case patient was pregnant). Management may involve reprogramming (e.g., deactivation of migrated leads), behavioral modification (e.g., avoiding manipulation), and periodic reassessment to ensure seizure control and device integrity.

Adopting best surgical practices and using state‐of‐the‐art equipment minimizes the risks associated with DBS implantation. Continued training on emerging technologies and techniques is essential for maintaining high standards of patient safety and care. Effective preventive strategies.

Effective preventive strategies for the development of Twiddler's Syndrome include:

Secure lead fixation using cranial plating and firm anchoring within a tight subcutaneous pocket [11, 12, 13].

Placement of the generator in an artificial pouch, such as the TYRX Absorbable Antibacterial Envelope, to reduce device mobility and minimize infection risk [12].

Consideration of alternative internal pulse generator (IPG) placements, such as abdominal positioning, in patients at high risk for manipulation [14].

Also, accurate placement of electrodes is crucial for the effectiveness of neuromodulation therapies. Following implantation, it is essential to immediately obtain a CT scan postsurgery and up to six weeks afterward to confirm the accurate placement of electrodes. This step is vital for correlating clinical outcomes with specific anatomical targets and preventing wrong‐site stimulation. Additionally, this helps ensure that the therapeutic goals of neuromodulation are met effectively.

Following successful implantation, it is of the utmost importance to emphasize proper hardware care. Manufacturers such as Medtronic (VNS/dB) and NeuroPace (RNS) provide detailed user manuals and patient guidelines that are indispensable for the care of neuromodulation devices. These instructions include guidelines on living with the device, recognizing signs of potential complications, and understanding the functionalities and limitations of the implanted system.

Additionally, regular follow‐up appointments are essential to ensure the ongoing success of DBS therapy. These sessions should review device performance, symptom management, and patient well‐being, adjusting treatment plans as necessary to optimize outcomes. The following strategies aid in the prevention and early identification of lead migration:

Regular postoperative imaging surveillance to detect early lead migration before clinical symptoms emerge.

Patient education on the risks of device manipulation and behavioral strategies to avoid inadvertent lead displacement [13].

During these clinic visits, routine interrogation of the device is crucial. Testing lead impedance and monitoring for lead migration can prevent malfunctioning of the device. Several studies have identified a decrease in impedance closely following stimulation, resulting in the delivery of a higher‐than‐intended current in older voltage‐controlled IPGs [15]. Identifying these issues early can significantly impact patient management and device functionality. It is important to note that changes in clinical responses may not solely be due to lead migration but also secondary to battery depletion. Implantable pulse generators typically last 5.4 years on average [16]. RNS devices, in use since 2015, may last longer due to noncontinuous stimulation. Battery type (fixed vs. rechargeable) also affects implant longevity. Regular monitoring and timely replacement of the battery are essential to maintain consistent device performance and therapeutic efficacy [16].

Lastly, the implementation of standardized reporting protocols within electronic medical records (EMRs) can help in systematically tracking changes in clinical response over time. This structured approach aids in assessing the long‐term effectiveness of the therapy and facilitates adjustments in treatment plans based on patient progress.

4. Conclusion

This case highlights the necessity of meticulous postoperative monitoring and the value of imaging follow‐up in patients with unexpected changes in seizure semiology following DBS. Awareness of Twiddler's syndrome and prompt intervention can optimize long‐term neuromodulation outcomes and maintain therapeutic efficacy in complex epilepsy cases.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript, compilation of patient data and development of the clinical framework.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the epilepsy fellows and the staff at the epilepsy monitoring unit for working with us over the past few months to help in the clinical management of the patient that has led to the smooth management of the patient's complications. We thank the Texas Institute of Restorative Neurotechnologists (TIRN), UTHealth, Houston for providing the essential support and incubation for our neuromodulation research.

Funding: Dr. Ganne Chaitanya's work on neuromodulation is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH‐R25 grant) [NS113757].

Shalin Shah and Ganne Chaitanya shared first authors.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH R‐25 grant): grant NS113757.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Zangiabadi N., Ladino L. D., Sina F., Orozco‐Hernández J. P., Carter A., and Téllez‐Zenteno J. F., “Deep Brain Stimulation and Drug‐Resistant Epilepsy: A Review of the Literature,” Frontiers in Neurology 10 (2019): 601, 10.3389/fneur.2019.00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fenoy A. J. and Simpson R. K., “Risks of Common Complications in Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery: Management and Avoidance,” Journal of Neurosurgery 120, no. 1 (2014): 132–139, 10.3171/2013.10.JNS131225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hariz M. I., “Complications of Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery,” Movement Disorders 17, no. Suppl 3 (2002): S162–S166, 10.1002/mds.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bayliss C. E., Beanlands D. S., and Baird R. J., “The Pacemaker‐Twiddler's Syndrome: A New Complication of Implantable Transvenous Pacemakers,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 99, no. 8 (1968): 371–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morishita T., Foote K. D., Burdick A. P., et al., “Identification and Management of Deep Brain Stimulation Intra‐ and Postoperative Urgencies and Emergencies,” Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 16, no. 3 (2010): 153–162, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foldvary‐Schaefer N. and Unnwongse K., “Localizing and Lateralizing Features of Auras and Seizures,” Epilepsy & Behavior 20, no. 2 (2011): 160–166, 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chaitanya G., Toth E., Pizarro D., Irannejad A., Riley K., and Pati S., “Precision Mapping of the Epileptogenic Network With Low‐ and High‐Frequency Stimulation of Anterior Nucleus of Thalamus,” Clinical Neurophysiology 131, no. 9 (2020): 2158–2167, 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morishita T., Hilliard J. D., Okun M. S., et al., “Postoperative Lead Migration in Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Impact,” PLoS One 12, no. 9 (2017): e0183711, 10.1371/journal.pone.0183711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hussain M. A. and Jenkins A., “Unusual Complication After Insertion of Deep Brain Stimulator Electrode,” British Journal of Neurosurgery 31, no. 2 (2017): 275, 10.1080/02688697.2016.1229748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Straw I., Ashworth C., and Radford N., “When Brain Devices Go Wrong: A Patient With a Malfunctioning Deep Brain Stimulator (DBS) Presents to the Emergency Department,” BML Case Reports 15, no. 12 (2022): e252305, 10.1136/bcr-2022-252305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghanchi H., Taka T. M., Bernstein J. E., Kashyap S., and Ananda A. K., “The Unsuccessful Twiddler: A Case of Twiddler's Syndrome Without Deep Brain Stimulator Lead Breakage,” Cureus 12, no. 4 (2020): e7786, 10.7759/cureus.7786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molle Z. K., Slotty P., and Vesper J., “Surgical Management of “Twiddler Syndrome” in Patients With Deep Brain Stimulation: A Technical Note and Review of the Literature,” Acta Neurochirurgica 164, no. 4 (2022): 1183–1186, 10.1007/s00701-022-05135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Penn D. L., Wu C., Skidmore C., Sperling M. R., and Sharan A. D., “Twiddler's Syndrome in a Patient With Epilepsy Treated With Deep Brain Stimulation,” Epilepsia 53, no. 7 (2012): 119–121, 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pourfar M. H., Budman C. L., and Mogilner A. Y., “A Case of Deep Brain Stimulation for Tourette's Complicated by Twiddler's Syndrome,” Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2, no. 2 (2015): 192–193, 10.1002/mdc3.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Satzer D., Lanctin D., Eberly L. E., and Abosch A., “Variation in Deep Brain Stimulation Electrode Impedance Over Years Following Electrode Implantation,” Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery 92, no. 2 (2014): 94–102, 10.1159/000358014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hariz M., Hariz G. M., and Blomstedt P., “Longevity of Deep Brain Stimulation Batteries; a Global Survey of Neurosurgeons and Neurologists,” Movement Disorders 36, no. 5 (2021): 1273–1274, 10.1002/mds.28501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.