Abstract

Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation has been proven to take part in the exacerbation of acute kidney injury (AKI). Ro 106-9920, an effective inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signal, could abrogate the formation of NETs. Herein, we explored whether Ro 106-9920 (Ro) exerts a protective role in AKI by repressing NET formation. The AKI model was induced with 30 min-bilateral renal ischemia followed by reperfusion. After finishing the 7-day treatment of Ro or vehicle, blood and the kidney were collected from each mouse for further analysis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, H&E, and TUNEL staining, immunohistochemistry, as well as Western blot were carried out to observe the kidney function, renal damage, apoptosis, and inflammation, and to preliminarily uncover the underlying mechanism. Administration with Ro effectively protected against AKI in a dose-dependent manner, as proven by the reduction of serum creatinine, serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, blood urea nitrogen, and serum inflammatory cytokine in AKI models after its administration. Moreover, Ro significantly alleviated morphological damage, kidney cells apoptosis, as well as inflammatory cytokine secretion in renal tissues. Mechanically, phosphorylation of NF-κB and myeloperoxidase activity were observed in renal tissues of AKI models, which suggested NF-κB activation and NETosis occurred in AKI. Notably, Ro treatment could significantly repress the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and the increased myeloperoxidase activity. Ro has a protective potential on ischemia/reperfusion-induced AKI by attenuating apoptosis and inflammation, perhaps by suppressing NF-κB activation and is associated with reduced NETosis.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, ischemia/reperfusion injury, Ro 106-9920, nuclear factor kappa B, neutrophil extracellular trap formation

Introduction

As one of heterogeneous disorders occurs in multiple clinical situations acute kidney injury (AKI) is manifested by reduced urine output and/or elevated serum creatinine levels, which is becoming highly prevalent worldwide [1]. In both native and transplanted kidneys, AKI mainly occurs due to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [2,3]. Even though preventive and therapeutic strategies have been consistently developed to manage AKI over last three decades, its morbidity and mortality remain high. Notably, patients with AKI patients are often susceptible to developing chronic kidney disease or even end-stage renal diseases [4]. It is important to continue the exploration of effective therapy to prevent and alleviate AKI.

Various experimental research supports that high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are in charge of tissue damage following IR injury [5,6]. Due to their critical role in renal chronic inflammation and tubular injury, multiple inflammation-related markers, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF‑α), myeloperoxidase (MPO), as well as IL-6, have been shown to be useful in evaluating the degree of disease severity in AKI patients [7,8]. As the front-line cells for the body’s immunity, neutrophils mediate inflammatory responses during tissue injury [9]. Neutrophils infiltration has been proven in renal injury induced by diverse means, including I/R [10]. I/R triggers the release of proinflammatory mediators, oxygen-free radicals, and other cytokines, subsequently stimulate neutrophils aggregate in the area of I/R, thereby destroying tissue [11]. After certain stimulation, neutrophils release DNA as a backbone and bind citrullinated histones (CitH3) and neutrophil granule proteins including MPO to form filamentous structures called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which in turn exacerbates tissue damage and interacts with other cells [12].

NETs play a critical role in tissue injury via multiple mechanisms, which included immune balance disruption, sterile inflammation, as well as enhancing vascular occlusion [13]. In various disorders caused by I/R, including ischemic stroke [14], limb I/R injury [15], and ischemia AKI [16,17], NETs were reported to aggravate disease progression and are closely related to worse disease outcomes. Both in vitro and in vivo tubular cell necrosis induced by I/R, secreted histone to prime neutrophils to form NETs, which triggered tubular epithelial cell death and further induced NET formation in fresh neutrophils [18]. Another study demonstrated that NETs are formed within the kidney after I/R and participate in I/R-induced injury, while suppressing peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 that is indispensable for NET formation, could protect rodents from I/R-induced AKI [19]. These works of literature support the pathological role of NETs in renal I/R injury and that specifically target NETs may be an effective strategy for AKI.

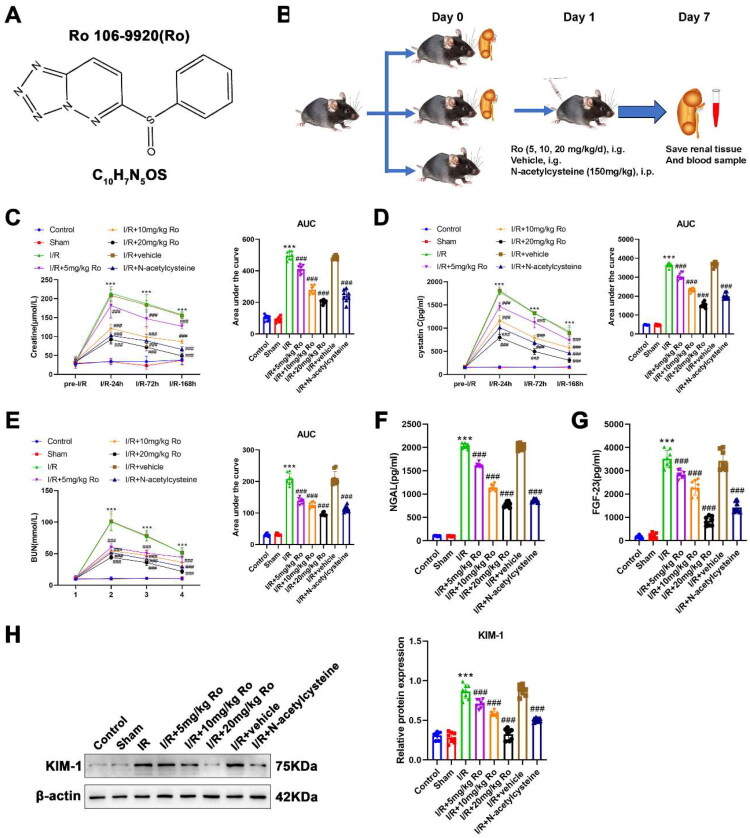

Ro 106-9920 (Ro; Figure 1A), a known inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signal, has been confirmed to abrogate NET formation. However, it remains unclear whether Ro can suppress the formation of NETs to protect against I/R-induced AKI. Hence, the current study explored the effects of Ro on NET formation during AKI, I/R-induced renal injury, and local and systemic inflammatory responses.

Figure 1.

Effects of Ro on the renal function of I/R-induced AKI mice.

A. The chemical structure of Ro 106-9920 (Ro).

B. Schematic diagram of the experimental design. Mice were subjected to bilateral renal I/R injury and treated with Ro (5, 10, 20 mg/kg/day, i.g.), vehicle, or N-acetylcysteine (150 mg/kg, i.p.). Renal tissue and blood samples were collected at the indicated time points.

C. Serum levels of creatine were detected by the commercial kit at Pre-I/R, 24h, 72h, and 168h after reperfusion. Corresponding area under the curve (AUC) analysis is shown on the right.

D. Serum levels of cystatin C were detected by the commercial kit at Pre-I/R, 24h, 72h, and 168h after reperfusion. Corresponding AUC analysis is shown on the right.

E. Serum levels of BUN were detected by the commercial kit at Pre-I/R, 24h, 72h, and 168h after reperfusion. Corresponding AUC analysis is shown on the right.

F. Serum levels of NGAL were detected by the commercial kit at 168h after reperfusion.

G. Serum levels of FGF-23 were detected by the commercial kit at 168h after reperfusion.

H. Western blot analysis of KIM-1 protein expression in renal tissues.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 per group). *** means P < 0.001 when vs. the control group; ### means P < 0.001 when vs. the I/R group.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgery

Experiments were performed using a total of 56 male C57BL/6J mice (6-8 weeks, 18-22 g in mass). The Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China) was the source from which mice were obtained. All animal handling and experiments were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. All mice were maintained in the specific pathogen-free laboratory with constant temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (62–65%) under a 12 h light and dark schedule and fed with standard chow pellets and water ad libitum throughout the whole experiment.

One-week adaptation period later, to mimic AKI on mice, forty-eight mice received intraperitoneal injections with 50 mg/kg of pentobarbital sodium to anesthetize them before inducing renal I/R injury by the operation of bilateral renal artery occlusion. The surgery was carried out as previously described [20]: All anesthetized mice were placed on a temperature-controlled heating table for a dorsal midline laparotomy. Then, using two non-traumatic vascular clamps, both renal left and right pedicles of I/R model mice (n = 48) were occluded bilaterally. In the meantime, the kidneys were observed, of which color turned pale, indicating renal ischemia was established. Thirty minutes of ischemia later, the clamps were detached. The incision was closed after confirming the reperfusion phase occurred (when the kidney color turned reddish brown). Sham mice (n = 8) underwent the same surgery without a renal pedicle clamped.

Blood samples were collected for obtaining serum at four time points: before ischemia (Pre-I/R), 24 h, 72 h, and 168 h after reperfusion, for subsequent renal function analysis. Following a treatment period of 7 days, also seven days post-surgery, all mice were anesthetized as mentioned above. This regimen was selected to cover the acute injury phase and early recovery: in pilot observations, most injury markers peak within 24-72 h after I/R and partially recover by day 7. A 7-day treatment allowed us to assess whether continued Ro administration aids in recovery over the first week post-injury. Both kidneys were harvested and perfused from the heart with precooled normal saline. The right kidney was rapidly homogenized and stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C for subsequent biochemical determination. For histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses, the left one was dissected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

Group and treatments

Fifty-six mice were initially randomized into three major groups (Normal, sham, and I/R mice) and I/R mice further divided into five subgroups according to the designated treatments (n = 8 mice per group; Figure 1B): (1) control (normal mice without any operation/treatment), (2) sham (sham mice with saline), (3) I/R, (4) I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, (5) I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, (6) I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, (7) I/R + vehicle, and (8) I/R + N-acetylcysteine. Three doses of Ro (CAS: 62645-28-7, purity ≥98.0%; MedChem Express, USA) were intragastrically given daily, while N-acetylcysteine (150 mg/kg) was intravenously injected daily for a week after bilateral renal artery occlusion. The 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg doses of Ro were chosen based on preliminary dose-ranging observations, aiming to include a low, intermediate, and high dose that remained tolerable in vivo. Normal saline was used instead of Ro in the sham and I/R groups. Ro was dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide with 90% corn oil, a vehicle chosen for its ability to solubilize Ro. Importantly, this vehicle and dose have minimal biological activity on their own, as supported by the inclusion of a vehicle-control group (I/R + vehicle group). A sample size of 8 mice per group was estimated via power analysis (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to provide >80% power to detect expected differences.

Renal function determination

The renal function was evaluated by detecting the serum levels of creatinine, urea nitrogen, FGF-23, Cystatin C, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) with commercially available kits (creatinine: Cat#E-BC-K188-M, Elabscience, USA; urea nitrogen: Cat#E-BC-K188-M, Elabscience; FGF-23: Cat#RAB0106, Sigma; Cystatin C: Cat#E-BC-K188-M, Elabscience; NGAL: Cat#ab199083, Abcam, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Serum creatinine, BUN, and cystatin C levels were measured at each time point (Pre-I/R, 24h, 72h, 168h), The area under the curve (AUC) for each biomarker over time was calculated to assess the overall renal functional changes.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Histopathological changes of the kidney were observed by staining paraffin-embedded renal sections with H&E reagent. Results are presented as the total histopathological score (0-12), which was determined according to the damage of the glomerulus, cortical and medullar loss of brush border, extent of foamy degeneration, as well as the degeneration of epithelial tubular cells. Four morphological alterations were classified on a scale of 0–3 (0, no damage; 1, <25%; 2, 25 ∼ 50%; 3, 50 ∼ 75%; 4, >75%) [21].

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay

To investigate apoptotic cells in kidney sections of each group, TUNEL assay was carried out with the in situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Switzerland) as per the manufacturer’s protocols. The kidney sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to 20 min incubation with proteinase K at room temperature followed by 1 h incubation with the TUNEL reaction solution at 37 °C. Finally, the sections were stained the nucleus with DAPI, and imaged under a fluorescence microscope.

Inflammatory cytokines detection

The levels of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, in serum samples were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercially available kits (IL-1β: Cat#BMS6002, ThermoFisher, USA); IL-6: Cat#SEKM-0007, Solarbio, China; TNF-α: Cat#BMS607-2HS, ThermoFisher) accordingly with manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative reverse transcription(qRT)-PCR

After being isolated total RNAs from kidney tissue using the TransZol Up reagent, 1 μg RNA was taken from each group, followed by reverse-transcription into complementary DNA using the cDNA Synthesis SuperMix system (TransGen Biotech). Quantitative PCR was subsequently conducted employing SYBR qPCR Master Mix with the following reaction conditions: 15 min at 92 °C pre-degeneration, 40 cycles of 92 °C (15 s) and 65 °C (20 s), then entering the melting/dissociation curve stage. The data were normalized to β-actin expression base on the 2-ΔΔCt method to calculate the relative expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, in the kidneys of each mouse. The primers used are listed as follows: TNF-α, forward 5′-ACTGATGAGAGGGAGGCCAT-3′, reverse 5′-CCGTGGGTTGGACAGATGAA-3′; IL-1β, forward 5′-GGGGCGTCCTTCATATGTGT-3′, reverse 5′-GGCAGCTCCTGTCTTGTAGG-3′; IL-6, forward 5′-TACCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGC-3′, reverse 5′-CTGCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTC-3′; and β-actin, forward 5′-TCCTATGGGAGAACGGCAGA-3′, reverse 5′-TCCTTTGTCCCCTGAGCTTG-3′.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

After the procedure of deparaffinization and rehydration, renal slides were subjected to antigen retrieval and inactivation of endogenous enzyme activity. Then, slides were blocked in 5% bovine serum album for 30 min, followed by overnight incubation with a primary antibody against NF-κB (Cat#AF0246, Beyotime, China; 1:200), and MPO (Cat#AF7494, Beyotime; 1:200) at 4 °C. Next, secondary antibodies were added for further 30 min incubation at room temperature. Finally, histological slides were analyzed under the optic microscope, whereas brownish color was considered to be evidence of a positive expression. IHC score ranges 0–12 [22], which was determined by multiplication between positive cells proportion score (0–4) and staining intensity score (0–3).

Western blot (WB) analysis

In order to obtain total protein, the collected kidney tissue samples were lysed with RIPA Lysis Buffer (Solarbio). Notably, to observe the translocation of NF-κB by detecting the expression of cytosolic phospho-NF-κB (p-NF-κB) and nuclear NF-κB, nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were isolated and extracted with the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (Beyotime, Cat#P0027) as per the corresponding protocol. After the determination of protein concentration with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat#PC0020, Solarbio), 20 μg protein samples were taken from each group and subjected to SDS polyacrylamide gel separation, followed by being transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Next, membranes were blocked for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies against KIM-1 (Abacm, Cat#ab316854), NF-κB (Cat#AF0246, Beyotime), p-NF-κB (Cat#AF5881, Beyotime), MPO (Cat#AF7494, Beyotime), Cit-H3 (Cat#ab219407, Abcam), β-actin (Cat#AF5003, Beyotime) (served as an internal control), Lamin B1 (Cat#AF1408, Beyotime) (served as an internal control of nuclear p-NF-κB) at 4 °C overnight, then incubating with the appropriate HRP-coupled secondary antibody (Cat#AF0208, Beyotime). Signals were visualized by chemiluminescence using an immobilon western HRP substrate (Millipore). Analysis of the data was finally performed using ImageJ software V1.53 (NIH).

MPO activity

MPO activity in kidney tissue was measured using a calorimetric kit from ElabScience (Cat#E-BC-K074-M) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 8.1.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was applied to conduct the statistical analyses. All data were expressed as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparative analyses among multiple groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. Evaluation of p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Effects of Ro on the renal function of I/R-induced AKI mice

The chemical structure of Ro was displayed in Figure 1A, and its effect on post-I/R was explored (Figure 1B). As shown in Figures 1C–E, I/R injury markedly increased serum creatinine (AUC: control, 100.893 ± 6.537 vs. I/R, 496.536 ± 9.169, p < 0.0001), cystatin C (AUC: control, 482.388 ± 5.803 vs. I/R, 3633.625 ± 38.220, p < 0.0001), and BUN (AUC: control, 31.209 ± 1.594 vs. I/R, 208.125 ± 6.202, p < 0.0001) levels over time compared with the control group. Treatment with Ro significantly reduced these I/R-induced elevations in a dose-dependent way (creatinine-AUC: I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 410.625 ± 9.801, p < 0.0001; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 280.875 ± 9.269, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 205.088 ± 3.986, p < 0.0001), (cystatin C-AUC: I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 3036.875 ± 63.808, p < 0.0001; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 2326.375 ± 38.838, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 1527.625 ± 47.667, p < 0.0001) (BUN-AUC: I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 138.675 ± 3.244, p < 0.0001; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 125.663 ± 3.253, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 96.094 ± 1.756, p < 0.0001). N-acetylcysteine treatment also ameliorated renal injury (creatinine-AUC: 240.613 ± 13.616, p < 0.0001; cystatin C-AUC: 2000.750 ± 55.323, p < 0.0001; BUN-AUC: 112.663 ± 3.399, p < 0.0001) but to a lesser extent than high-dose Ro treatment. In addition, biomarkers of kidney injury were assessed at 168h post-I/R. Serum NGAL (Figure 1F) and FGF-23 (Figure 1G) levels were significantly elevated after I/R injury (NGAL: control, 102.623 ± 2.854 vs. I/R, 2031.942 ± 18.368, p < 0.0001; FGF-23: control, 149.645 ± 24.498 vs. I/R, 3519.460 ± 126.356, p < 0.0001). Both Ro and NAC treatments markedly reduced NGAL and FGF-23 levels compared to the untreated I/R group (NGAL: I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 1614.776 ± 14.729, p < 0.0001; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 1139.937 ± 24.212, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 776.175 ± 20.036, p < 0.0001; I/R + N-acetylcysteine, 860.440 ± 11.021, p < 0.0001) (FGF-23: I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 2836.791 ± 59.446, p < 0.0001; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 2277.763 ± 115.117, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 841.909 ± 67.524, p < 0.0001; I/R + N-acetylcysteine, 1420.410 ± 79.077, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, WB analysis revealed that Ro administration attenuated the upregulation of KIM-1 protein in renal tissues of I/R mice (Figure 1H). Notably, even 5 mg/kg Ro significantly reduced KIM-1 expression relative to the I/R group, although the suppression was more prominent at higher doses. In the meantime, the I/R + vehicle group showed no significant differences in kidney injury markers compared to the untreated I/R group. These findings suggest that Ro 106-9920 provides dose-dependent renal protection after I/R injury.

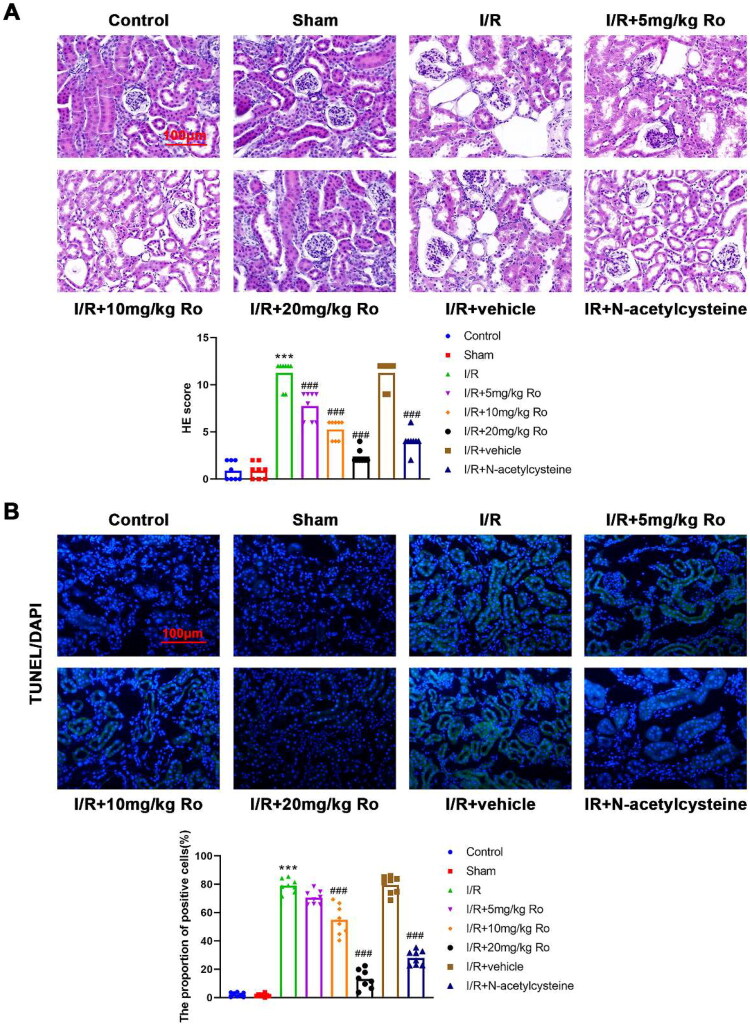

Ro alleviates renal damage of I/R-induced AKI mice

In the kidneys of mice with AKI induced by I/R, severe injury of the renal tubular epithelium was observed, characterized by loss of the brush border, tubular necrosis, cast formation, and tubular dilatation. (Figure 2A; control, 0.333 ± 0.577, vs. I/R, 11.000 ± 1.732, p < 0.0001). These changes were dramatically limited by treatment with three doses of Ro (Figure 2A; I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 7.000 ± 1.732, p = 0.0460; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 3.333 ± 1.155, p = 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 1.000 ± 1.000, p < 0.0001). Then, whether Ro affected renal apoptosis was also explored. TUNEL assay showed that renal slides of mice with AKI induced by I/R displayed significantly higher apoptotic rate of renal tubular epithelial cells than those of control mice (Figure 2B; control, 0.353 ± 0.295, vs. I/R, 79.943 ± 8.174, p < 0.0001). Importantly, I/R induced renal cell apoptosis were markedly reverted by Ro, especially the high dose (Figure 2B; I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, 70.750 ± 6.458, p > 0.9999; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, 50.767 ± 7.412, p = 0.0002; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, 1.310 ± 0.497, p < 0.0001). This data indicated the anti-apoptotic effect of Ro on the I/R-induced AKI.

Figure 2.

Ro Alleviates renal damage of I/R-induced AKI mice.

A. Pathological changes in the kidney were observed by H&E staining. Scale bar = 100 μm.

B. Renal cell apoptosis was observed by TUNEL staining. Scale bar = 100 μm.

*** means P < 0.001 when vs. the control group; ### means P < 0.001 when vs. the I/R group.

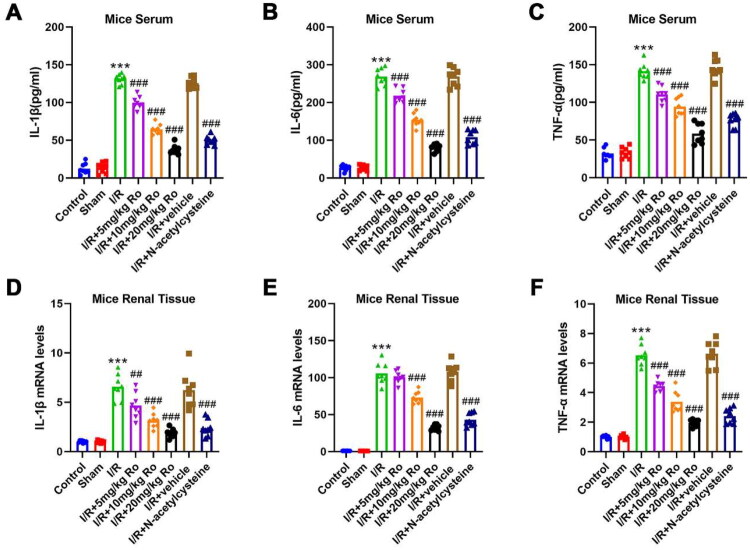

Ro reduces I/R-induced renal inflammation

To investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of Ro on I/R-induced AKI, the serum concentrations and renal mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines, which included IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, were assessed. As shown in Figure 3A–C, the serum inflammatory cytokines significantly increased after I/R (control vs. I/R, IL-1β: 12.075 ± 5.602 vs. 130.663 ± 4.217, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 27.057 ± 2.946 vs. 268.692 ± 3.241, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 34.490 ± 2.756 vs. 139.820 ± 4.537, p < 0.0001), whereas Ro administration dose-dependently suppressed them (I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 99.540 ± 4.165, p = 0.0002, IL-6:217.051 ± 6.105, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 117.583 ± 4.436, p = 0.0004; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 62.247 ± 3.220, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 147.485 ± 4.208, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 92.040 ± 4.363, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 36.848 ± 2.578, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 80.725 ± 5.194, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 61.675 ± 3.702, p < 0.0001), which suggested that Ro could mitigate the systemic inflammatory response. Renal inflammation has been proven to exacerbate kidney damage. In mice subjected to I/R operation, the transcription levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased compared to those in the control mice (Figure 3D–F; control vs. I/R, IL-1β: 1.000 ± 0.089 vs. 6.313 ± 0.491, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 1.000 ± 0.036 vs. 118.230 ± 7.858, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 1.000 ± 0.053 vs. 6.083 ± 0.287, p < 0.0001). Notably, treatment with 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg Ro effectively prohibited these cytokines broke out in the renal tissues (I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 3.980 ± 0.303, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 100.217 ± 2.437, p = 0.0096, TNF-α: 4.413 ± 0.234, p = 0.0004; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 3.330 ± 0.450, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 75.847 ± 4.476, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 3.330 ± 0.450, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, IL-1β: 2.007 ± 0.119, p < 0.0001, IL-6: 36.930 ± 3.084, p < 0.0001, TNF-α: 1.973 ± 0.115, p < 0.0001). The results collectively indicated that Ro is capable of reducing inflammation by I/R-stimulated AKI.

Figure 3.

Ro Reduces I/R-induced renal inflammation.

A–C. Serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) were assessed by the ELISA kits.

D–F. The mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) in the renal tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR.

*** means P < 0.001 when vs. the control group; ## means P < 0.01 and ### means P < 0.001 when vs. the I/R group.

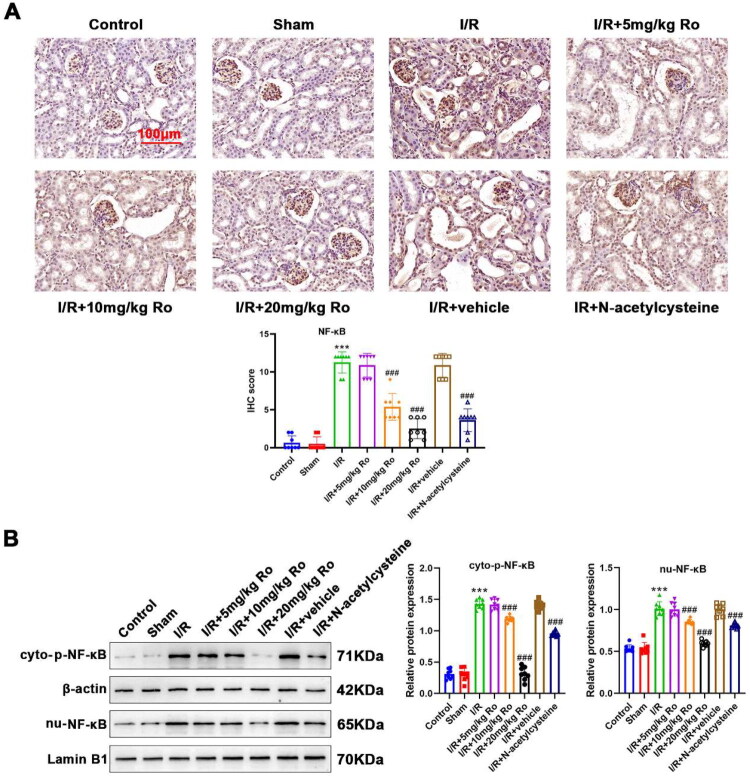

Ro inhibits NF-κB activation in the kidney of I/R-induced AKI mice

Next, the role of NF-κB in I/R-induced AKI was investigated. NF-κB activation was determined by IHC (NF-κB protein expression) and WB (observe the translocation of NF-κB by detecting cytosolic p-NF-κB and nuclear NF-κB) analysis. Compared with the kidneys of control mice, NF-κB was significantly activated in those of I/R-induced AKI mice, as revealed by increased renal NF-κB IHC staining (Figure 4A; control vs. I/R, 0.333 ± 0.577 vs. 11.000 ± 1.732, p < 0.0001) as well as the elevation in cytosolic p-NF-κB (control vs. I/R, 0.537 ± 0.056 vs. 1.436 ± 0.159, p < 0.0001) and nuclear NF-κB (control vs. I/R, 0.330 ± 0.095 vs. 1.071 ± 0.078, p < 0.0001) (Figure 4B). Both IHC and WB analyses showed that Ro (5 mg/kg) alone did not significantly inhibit NF-κB activation in I/R-induced AKI mice in (Figure 4A,B; IHC scores: 8.000 ± 1.732, p = 0.2505, cytosolic p-NF-κB: 1.344 ± 0.013, p > 0.9999, nuclear NF-κB: 0.957 ± 0.016, p > 0.9999). However, by intervention with 10 and 20 mg/kg of Ro, the I/R-induced NF-κB IHC staining and translocation of NF-κB in the nucleus were reduced effectively (Figure 4A,B; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, IHC scores: 4.667 ± 1.155, p = 0.0006, cytosolic p-NF-κB: 0.944 ± 0.029, p = 0.0011, nuclear NF-κB: 0.944 ± 0.029, p = 0.0002; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, IHC scores: 1.333 ± 0.577, p < 0.0001, cytosolic p-NF-κB: 0.632 ± 0.059, p < 0.0001, nuclear NF-κB: 0.3384 ± 0.067, p < 0.0001). These data demonstrated that 10 and 20 mg/kg of Ro effectively blocked I/R triggered NF-κB activation.

Figure 4.

Ro Inhibits NF-κB activation in the renal of I/R-induced AKI mice.

A. Expression of NF-κB in the renal sections was observed by IHC analysis.

B. Cytosolic p-NF-κB and nuclear NF-κB levels in the renal tissue were detected by WB analysis.

*** means P < 0.001 when vs. the control group; # means P < 0.05, ## means P < 0.01 and ### means P < 0.001 when vs. the I/R group.

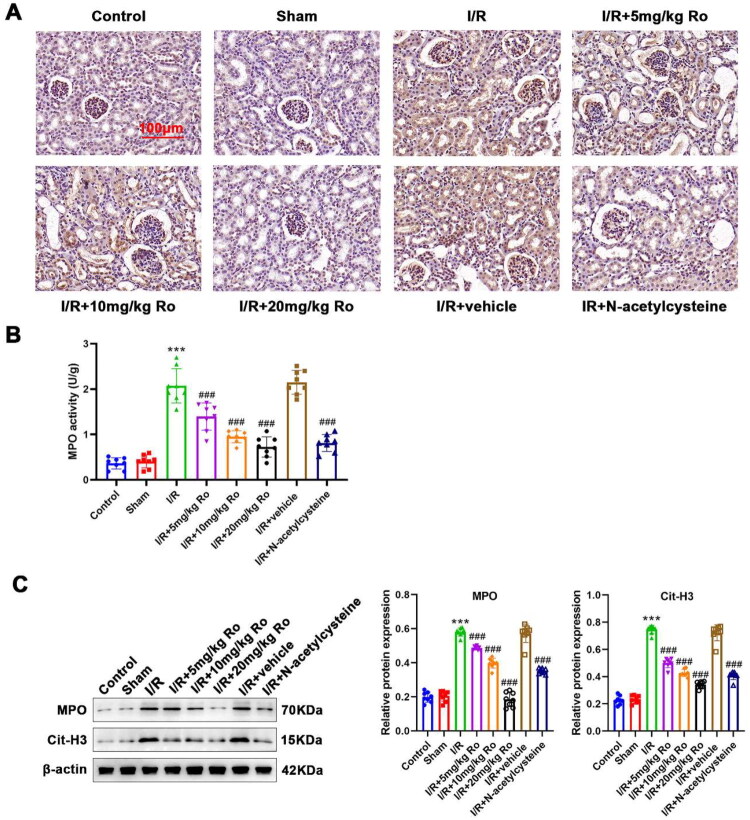

Ro is associated with reduced NETosis in the kidney of I/R-induced AKI mice

Previous publication supported the critical role of NETosis in I/R-induced AKI and Ro has been shown to effectively suppress NETs formation. Hence, it is reasonable to suppose that reduce of NETosis would be involved in the mechanism behind the protection of Ro in I/R-induced AKI. MPO is one of NETosis biomarker, IHC staining and the corresponding activity assay kit was applied to investigate neutrophil infiltration. The assays showed no infiltrating neutrophils and NETs markers were shown in control mouse kidneys (Figure 5A–C; control vs. I/R, MPO activity: 0.332 ± 0.148 vs. 1.931 ± 0.130, p < 0.0001, MPO expression: 0.850 ± 0.024 vs. 1.628 ± 0.133, p < 0.0001, Cit-H3 expression: 0.471 ± 0.064 vs. 1.279 ± 0.112, p < 0.0001). In contrast, the significant increase of NETosis in the I/R-induced AKI mice was significantly reduced by the Ro treatment (Figure 5A,B; I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, MPO activity: 1.537 ± 0.130, p = 0.0447; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, MPO activity: 1.045 ± 0.077, p < 0.0001; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, MPO activity: 0.738 ± 0.133, p < 0.0001). Similarly, WB results showed the protein levels of MPO and Cit-H3 was elevated in the kidney of I/R-induced AKI mice, which were also reduced by Ro treatment (Figure 5C; I/R + 5 mg/kg Ro, MPO expression: 1.154 ± 0.140, p = 0.0021, Cit-H3 expression: 0.979 ± 0.096, p = 0.2288; I/R + 10 mg/kg Ro, MPO expression: 1.029 ± 0.115, p = 0.0002, Cit-H3 expression: 0.762 ± 0.124, p = 0.0371; I/R + 20 mg/kg Ro, MPO expression: 0.815 ± 0.045, p < 0.0001, Cit-H3 expression: 0.522 ± 0.088, p < 0.0001). Overall, these results showed that Ro is associated with reduced NETosis in the kidney tissues of the I/R-induced AKI mice.

Figure 5.

Ro Suppresses NETosis in the renal of I/R-induced AKI mice.

A. Expression of MPO in the renal sections was observed by IHC analysis.

B. Renal MPO activity was measured using the commercial kit.

C. MPO and Cit-H3 protein levels in the renal tissue were detected by WB analysis.

*** means P < 0.001 when vs. the control group; ### means P < 0.001 when vs. the I/R group.

Discussion

According to a retrospective Chinese cohort research, the overall incidence of AKI was approximately 12% with more than 8% of in-hospital mortality [23]. AKI is therefore a serious issue; no efficient drug is available. Hence, exploring such a drug is an urgent need. We showed that Ro, an NF-κB inhibitor, effectively protected renal function against I/R-induced damage by inhibiting apoptosis, inflammation, activation of NF-κB, as well as NETs formation. In our study, only male mice were used to establish the renal I/R model. This decision was based on previous reports showing that endogenous estrogen confers protection against I/R injury in females, leading to milder tissue damage and faster functional recovery compared to males [24,25]. As a result, using male mice ensures a more consistent and reproducible injury model.

As the major cause of AKI in humans, I/R can induce various degrees of oxidative stress and inflammation to impair and even damage renal function and integrity [26]. Due to the characteristics of AKI with kidney apoptosis and inflammation, the agents alleviating these symptoms would be particularly helpful [27,28]. In the current study, in I/R-induced AKI models, 30 min-renal ischemia followed by reperfusion resulted in remarkable kidney dysfunction, as revealed by a marked elevation in the concentrations of serum creatine, blood urea nitrogen, and NGAL. Consistently, a similar extent of severity of kidney injury to the AKI mouse model has been reported in many previous studies [29,30], suggesting I/R-induced AKI models were reproducible and well grounded. Notably, in our study, Ro was proven to be renoprotective in AKI mouse models, as evidenced at both pathological and biochemical levels. Moreover, our data revealed a dose-dependent protective effect of Ro. Treatment with 5 mg/kg Ro did not significantly inhibit NF-κB activation or NETosis, whereas 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg Ro significantly attenuated these pathological processes. This finding suggests that a threshold dose is required to achieve effective suppression of inflammation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation during AKI progression.

In I/R induced-AKI, proximal tubule cells are extraordinarily vulnerable to apoptosis, and tubular cell lessening leads to reduced glomerular filtration rate and increased backleak [31]. Based on the TUNEL method, a remarked increase in the amount of labeling was observed in the kidneys from AKI mice. Ro dramatically reduced the tubular cell apoptosis in AKI, suggesting that anti-apoptosis may be one of the mechanisms behind renoprotective action from Ro. Alternatively, inflammation is demonstrated to be essential in the progression of I/R-induced organ disorders [32]. Over the past few decades, the close relationship between inflammation with renal I/R injury has been proven [33]. After being injured by I/R, kidney cells secrete various of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines to recruit inflammatory cells which further produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby aggravating the development of AKI. In addition, platelet activation responses induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines would trigger the complement system, which mediates renal cell inflammation, enhancing AKI progression [34]. Ro is capable of impairing platelet activation responses due to its suppression on the NF-κB signal [35]. Therefore, suppressing inflammation by Ro could also protect against kidney damage in AKI mice. The serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, all of which contribute to the inflammation during AKI [36–38], were found to be increased substantially in renal I/R mice in the current research. Herein, Ro could noticeably reduce I/R-induced production and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in serum and renal tissues of AKI models.

TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, such well-studied cytokines, are downstream molecules that could be directly regulated by NF-κB [39]. The NF-κB family of transcription factors incorporates extracellular stimulus with intracellular transduction signaling, modulating genes associated with apoptosis and inflammation at transcriptional level. Targeting NF-κB therefore is a potent therapeutic strategy for inflammatory diseases. A variety of etiologies of AKI, including lipopolysaccharides and I/R, has capabilities to activate the NF-κB signal via distinct pathways in tubular cells [40,41]. Its classic activation is closely linked with NF-κB nuclear translocation. After NF-κB entering the nucleus, it binds to promoters of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby up-regulating the corresponding expressions. Hence, we measured cytosolic p-NF-κB and nuclear NF-κB when exploring the effects of Ro on the activation of NF-κB. Our data clearly showed that Ro could suppress NF-κB nuclear translocation, which revealed by the impairment of cytosolic p-NF-κB and nuclear NF-κB expression, indicating that NF-κB activation impairment may be responsible for the renoprotective action of Ro. Ro treatment inhibited cytokine upregulation in AKI, accompanied by the inhibition of NF-κB activation. We thus propose that Ro can relive inflammation by preventing NF-κB nuclear translocation during AKI. Although inhibition of NF-κB activation by Ro provided significant protection against I/R-induced AKI, it is important to note that NF-κB also plays essential roles in maintaining normal immune responses and promoting cell survival. Excessive or prolonged suppression of NF-κB may impair host defense mechanisms, delay tissue repair, and exacerbate susceptibility to infections. Therefore, future studies are warranted to evaluate the optimal dosing, timing, and safety profile of NF-κB inhibitors like Ro to balance efficacy and potential risks. Interestingly, our data showed that the lowest dose of Ro (5 mg/kg) yielded only minimal reductions in NET markers (e.g. Cit-H3 level was not significantly lower than in untreated I/R mice), whereas 10 and 20 mg/kg doses produced robust decreases. This suggests a threshold effect wherein partial NF-κB inhibition at 5 mg/kg may be insufficient to suppress NET formation. In line with recent reports of U-shaped NF-κB effects, a moderate level of NF-κB suppression might be required for optimal therapeutic benefit. Zhang et al. demonstrated that both excessive activation and insufficient activation of NF-κB signaling can lead to adverse outcomes such as hypertension and chronic kidney disease, suggesting the potential U-shaped effects of manipulating NF-κB [42]. These findings highlight that appropriate modulation, rather than complete suppression, of NF-κB activity is crucial. Therefore, when considering Ro 106-9920 as a potential therapeutic agent for AKI, it will be essential to carefully define the therapeutic window to avoid unwanted detrimental effects. Future studies should explore additional doses and dosing schedules (e.g. intermediate doses between 5 and 10 mg/kg, or different timing) to define the therapeutic window of Ro. Careful dose-response assessments, guided by the U-shaped curve concept, will help identify an optimal dose that maximizes efficacy while minimizing potential risks.

After AKI occurs, neutrophils are the first immune cells to penetrate the interstitium of the kidney [43]. Extravagant neutrophil aggregation can cause tissue injury. In addition to phagocytosis, neutrophils have also been shown to release NETs. Initially, NETs was denoted as a strong defense to microbiota and was recently reported to be a contributor of the pathogenesis of pathogen-free inflammation, including renal I/R [44]. The relationship between the NETs with the activity of NF-κB pathway is vital [45]. Recently, the NF-κB pathway was revealed to directly up-regulate NETosis, thereby aggravating disease progression [46]. Neutrophil proteins, such as MPO with CitH3, are widely accepted markers of NET formation. Our study found increased NET formation, as measured by MPO activity and expression, as well as Cit-H3 expression in renal tissues from the I/R mice. Ro could reduce NETosis via an NF-κB-dependent mechanism [47]. These data revealed that Ro not only inhibited NF-κB nuclear translocation but also reduced the I/R-induced NETosis in the kidneys, which collectively revealed Ro treatment was associated with reduced NF-κB activation and NET formation, which likely contributed to the attenuation of renal injury. We acknowledge that our evidence of NETosis is indirect, based on MPO activity and Cit-H3 protein expression in kidney tissues. Definitive identification of NETs would require visual confirmation through immunofluorescent co-localization of extracellular DNA with neutrophil granule proteins (e.g. MPO) and citrullinated histones (e.g. Cit-H3) in web-like structures. In addition, our current measurements in tissue homogenates do not allow us to localize NET formation or distinguish between infiltrating circulating neutrophils and potential resident sources in the kidney. Moreover, we assessed NETosis only at a single time point (day 7 post-I/R), which may not reflect the peak or full dynamics of NET formation and clearance. Future studies will incorporate high-resolution immunofluorescence microscopy or in vivo imaging techniques to localize NETs in situ, as well as serial sampling at multiple time points (e.g. 6 h, 24 h, 72 h, and 7 days) to construct a detailed time course of NETosis during AKI progression and resolution.

In addition to NF-κB activation and NETosis, several other pathological mechanisms have been implicated in the development of I/R-induced AKI. These include oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis, which contribute to renal tubular injury and inflammation. Although the current study primarily focused on the NF-κB/NETosis axis, future investigations are warranted to explore the potential interactions between Ro treatment and these alternative pathways to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of its protective mechanisms.

This is the first report to discover the potential of Ro for attenuating AKI. However, there were some limitations in our study. First, we evaluated only the therapeutic potential of Ro administered shortly after the onset of renal I/R injury. It remains unclear what the effect of pretreatment with Ro in renal I/R prevention. Moreover, in clinical settings, the diagnosis and intervention of AKI often occur several hours to days after the initial injury. Therefore, future investigations are warranted to determine the efficacy of Ro when given as a pretreatment for AKI prevention, to compare prophylactic vs. therapeutic strategies, and whether Ro remains effective when administered at delayed time points post-AKI onset to define its therapeutic window and optimal timing for clinical translation. Although our research demonstrated that Ro could reduce the activation of NF-κB, coinciding with reduced NETosis in our model, these findings are associative. We cannot definitively conclude from our in vivo data alone that NF-κB activation directly causes NET formation (or vice versa) without additional mechanistic experiments. Hence, the precise molecular mechanisms by which Ro regulates these pathways remain to be elucidated. Current findings were mainly based on protein-level analyses. Future studies will employ more advanced mechanistic approaches to directly dissect the NF-κB/NETs relationship. For example, transgenic or knockout mouse models (such as mice deficient in key NETosis regulators like PAD4 or Cit-H3) will be employed in future mechanistic studies to see if blocking NET formation mimics the effects of Ro. Similarly, conditional NF-κB knockout mice (or pharmacological NF-κB activation in the presence/absence of Ro) could help establish causality. In vitro, siRNA-mediated knockdown of NF-κB subunits or NET-related proteins in neutrophils will be used to confirm that effects of Ro are indeed through these targets. Techniques like chromatin immunoprecipitation could also verify whether NF-κB directly binds promoters of NETosis-related genes in this context. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic profile, tissue distribution, and safety of Ro remain to be fully elucidated. Although Ro showed significant therapeutic efficacy in our acute AKI model, it is essential to investigate its absorption, bioavailability, metabolism, and potential off-target effects in vivo. Future preclinical studies are warranted to comprehensively assess the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of Ro, which will be crucial for its clinical translation. Lastly, but not least, the present study focused on the acute phase of I/R-induced kidney injury. The long-term outcomes, including renal fibrosis development and the progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD), were not evaluated. Extended observation periods and assessment of fibrotic markers such as collagen deposition and α-SMA expression should be incorporated in future studies to determine whether Ro can prevent the AKI-to-CKD transition.

In summary, the present study found that Ro protected against I/R-induced AKI by prohibiting both apoptosis and inflammation. The renoprotection of Ro may be attributable to the blockage of NF-κB activation and NETosis. Ro shows promise as an experimental candidate for AKI; however, its safety profile, optimal dosing, and pharmacokinetics require thorough investigation before clinical translation. Before moving to clinical trials, further preclinical work is required, which included detailed pharmacokinetic studies to ensure adequate drug delivery to renal tissue, formal toxicology assessments to establish a safety margin, and testing in additional models (and potentially larger animals) to confirm efficacy and safety. Moreover, regulatory requirements demand Good Manufacturing Practice production and safety pharmacology (cardiac, neurologic toxicity assays) for any new therapeutic.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Kellum JA, Romagnani P, Ashuntantang G, et al. Acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):52. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00284-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Zhang Q, Wen J, et al. Ischemic duration and frequency determines AKI-to-CKD progression monitored by dynamic changes of tubular biomarkers in IRI Mice. Front Physiol. 2019;10:153. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu Jawdeh BG, Govil A.. Acute kidney injury in transplant setting: differential diagnosis and impact on health and health care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(4):228–232. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, et al. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(5):891–898. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05571008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutz J, Thürmel K, Heemann U.. Anti-inflammatory treatment strategies for ischemia/reperfusion injury in transplantation. J Inflamm (Lond). 2010;7(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R, Xie L, Li L, et al. The gut microbial metabolite, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionic acid, alleviates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury via mitigation of macrophage pro-inflammatory activity in mice. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(1):182–196. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee DW, Faubel S, Edelstein CL.. Cytokines in acute kidney injury (AKI). Clin Nephrol. 2011;76(3):165–173. doi: 10.5414/cn106921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farooqui N, Zaidi M, Vaughan L, et al. Cytokines and immune cell phenotype in acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8(3):628–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2022.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altmann DM. The immune regulatory role of neutrophils. Immunology. 2019;156(3):215–216. doi: 10.1111/imm.13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizokami T, Shimada M, Suzuki K.. Neutrophil depletion attenuates acute renal injury after exhaustive exercise in mice. Exp Physiol. 2024;109(4):588–599. doi: 10.1113/EP091362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schofield ZV, Woodruff TM, Halai R, et al. Neutrophils–a key component of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock. 2013;40(6):463–470. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sørensen OE, Borregaard N.. Neutrophil extracellular traps - the dark side of neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(5):1612–1620. doi: 10.1172/JCI84538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):134–147. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denorme F, Portier I, Rustad JL, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps regulate ischemic stroke brain injury. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(10):e154225. doi: 10.1172/JCI154225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oklu R, Albadawi H, Jones JE, et al. Reduced hind limb ischemia-reperfusion injury in Toll-like receptor-4 mutant mice is associated with decreased neutrophil extracellular traps. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(6):1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X, You D, Cui J, et al. Reduced neutrophil extracellular trap formation during ischemia reperfusion injury in C3 KO mice: c 3 requirement for NETs release. Front Immunol. 2022;13:781273. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.781273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Dong Z.. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemic AKI: new way to kill. Kidney Int. 2018;93(2):303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakazawa D, Kumar SV, Marschner J, et al. Histones and neutrophil extracellular traps enhance tubular necrosis and remote organ injury in ischemic AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1753–1768. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016080925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raup-Konsavage WM, Wang Y, Wang WW, et al. Neutrophil peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 has a pivotal role in ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2018;93(2):365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang Y, Liu Z, Qu L, et al. Inhibition of the IRE1/JNK pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells attenuates ferroptosis in acute kidney injury. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:927641. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.927641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fattori V, Borghi SM, Guazelli CFS, et al. Vinpocetine reduces diclofenac-induced acute kidney injury through inhibition of oxidative stress, apoptosis, cytokine production, and NF-κB activation in mice. Pharmacol Res. 2017;120:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawaetz M, Christensen A, Juhl K, et al. Potential of uPAR, αvβ6 integrin, and tissue factor as targets for molecular imaging of oral squamous cell carcinoma: evaluation of nine targets in primary tumors and metastases by immunohistochemistry. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3853. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Nie S, Liu Z, et al. Epidemiology and clinical correlates of AKI in Chinese hospitalized adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1510–1518. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02140215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Chang Y, Han Z, et al. Estrogen protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating Th17/Treg cell immune balance. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:7812099–7812014. doi: 10.1155/2022/7812099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kher A, Meldrum KK, Wang M, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of sex differences in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67(4):594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulay SR, Linkermann A, Anders HJ.. Necroinflammation in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(1):27–39. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015040405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murata I, Sugai T, Murakawa Y, et al. Salvianolic acid B improves the survival rate, acute kidney dysfunction, inflammation and NETosis-mediated antibacterial action in a crush syndrome rat model. Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(5):320. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spandou E, Tsouchnikas I, Karkavelas G, et al. Erythropoietin attenuates renal injury in experimental acute renal failure ischaemic/reperfusion model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(2):330–336. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He J, Wang Y, Sun S, et al. Bone marrow stem cells-derived microvesicles protect against renal injury in the mouse remnant kidney model. Nephrology (Carlton). 2012;17(5):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viñas JL, Spence M, Porter CJ, et al. micro-RNA-486-5p protects against kidney ischemic injury and modifies the apoptotic transcriptome in proximal tubules. Kidney Int. 2021;100(3):597–612. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Havasi A, Borkan SC.. Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):29–40. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang M, Liu Q, Meng H, et al. Ischemia-reperfusion injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):12. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01688-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurman JM. Triggers of inflammation after renal ischemia/reperfusion. Clin Immunol. 2007;123(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Guo W, Tao XG, et al. Platelet count as an independent risk factor for acute kidney injury induced by rhabdomyolysis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(14):1738–1740. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malaver E, Romaniuk MA, D’Atri LP, et al. NF-kappaB inhibitors impair platelet activation responses. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(8):1333–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H, Lei CT, Zhang C.. Interleukin-6 signaling pathway and its role in kidney disease: an update. Front Immunol. 2017;8:405. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantaluppi V, Quercia AD, Dellepiane S, et al. Interaction between systemic inflammation and renal tubular epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(11):2004–2011. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anders HJ. Of inflammasomes and alarmins: IL-1β and IL-1α in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(9):2564–2575. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun SC. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(9):545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panah F, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Argani H, et al. Ischemic acute kidney injury and klotho in renal transplantation. Clin Biochem. 2018;55:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Y, Zhang Y, Wang L, et al. The role of autophagy in kidney inflammatory injury via the NF-κB route induced by LPS. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(8):655–667. doi: 10.7150/ijms.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Wang G, Li M, et al. Both partial inactivation as well as activation of NF-κB signaling lead to hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39(12):1993–2004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfae090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1503–1520. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakazawa D, Kumar S, Desai J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in tissue pathology. Histol Histopathol. 2017;32(3):203–213. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ramos AM, et al. Regulated cell death pathways in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(5):281–299. doi: 10.1038/s41581-023-00694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.An Z, Li J, Yu J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induced by IL-8 aggravate atherosclerosis via activation NF-κB signaling in macrophages. Cell Cycle. 2019;18(21):2928–2938. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2019.1662678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lapponi MJ, Carestia A, Landoni VI, et al. Regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation by anti-inflammatory drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345(3):430–437. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.202879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.