Abstract

Background

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is linked to early-onset cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, the corresponding disease burden has not been assessed. This study aims to evaluate the global, regional, and national early-onset CVD burden attributable to PM2.5 from 1990 to 2021.

Methods

We calculated the number, age-standardized rate, and percentage of CVD deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to PM2.5 among individuals aged 25–49 years from 1990 to 2021 based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Stratified analyses were performed by sex, age, disease subtype, sociodemographic index (SDI), and country. We further calculated estimated annual percentage change to assess the temporal trends.

Results

In 2021, the age-standardized death and DALY rates (per 100,000) of early-onset CVD attributable to total PM2.5 were 10.93 (95% confidence interval, 10.89–10.97) and 562.12 (561.84–562.39), respectively. The burden was generally higher in males, with age-standardized death and DALY rates approximately double those in females. Individuals living in regions with lower SDI faced substantially greater burden compared to those in higher-SDI regions. Those with ischemic heart disease experienced higher burden than individuals with stroke. From 1990 to 2021, the burden attributable to total and household PM2.5 declined consistently, with estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death rates of − 1.56% (− 1.68% to − 1.45%) and − 3.22% (− 3.48% to − 2.96%), respectively. The burden from ambient PM2.5 continued to rise, and only began to decline since the last decade, with an estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death rates of 0.37% (0.23%–0.52%). In contrast, the late-onset CVD burden decreased for both ambient and household exposures.

Conclusions

Despite significant reduction in early-onset CVD burden attributable to total and household PM2.5 from 1990 to 2021, the burden from ambient PM2.5 remains a persistent challenge. Males, individuals living in regions with lower SDI, and those with ischemic heart disease face a higher burden. Geographically tailored and population-specific interventions are needed to mitigate early-onset CVD burden.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04309-2.

Keywords: Fine particulate matter, Cardiovascular disease, Early-onset, Risk factor, Global Burden of Disease Study 2021

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2021, CVD deaths increased from 12.3 million in 1990 to 19.4 million in 2021, accounting for more than a quarter of total deaths globally [1]. Although CVDs are more common among middle-aged and elderly individuals, there is an increasing trend in the prevalent CVD cases among those under 50 years of age (defined as early-onset CVD in the present study) [2–5]. Early-onset CVD poses particular concern due to its long-term impact on health, including higher risks of recurrence, disability, and premature mortality [6–8]. This underscores the urgent need to summarize modifiable risk factors for early-onset CVDs and assess the corresponding disease burden.

Air pollution, especially fine particulate matter (PM2.5), has emerged as one of the most important global public health threats. PM2.5 is currently identified as the second leading risk factor for CVD burden worldwide [9]. Some studies also linked PM2.5 exposure with increased risk of early-onset CVD [10–12]. However, previous studies evaluating CVD burden attributable to PM2.5 have rarely differentiated between early- and late-onset CVDs [13–15]. Given the difference in exposure patterns and health conditions between the younger and elderly populations, the burden of early-onset and late-onset CVD due to PM2.5 may differ significantly. Therefore, it is essential to specifically evaluate the disease burden of early-onset CVDs attributable to PM2.5. Such knowledge is critical for developing targeted interventions to mitigate the cardiovascular impacts of air pollution.

Therefore, we utilized data from the GBD 2021 database to comprehensively investigate the global, regional, and national burden of early-onset CVDs attributable to PM2.5 pollution from 1990 to 2021, stratified by sex, age, disease subtype, sociodemographic index (SDI), and country. We further examined the temporal trends during the past three decades to understand how the burden has shifted across different regions and demographic subgroups.

Methods

Overview

The analyses of the present study were based on GBD 2021. The detailed information on the design and standardized methodologies of GBD 2021 has been published previously [1, 9]. In brief, GBD 2021 conducted a comprehensive evaluation on sex- and age-specific deaths for 288 causes, prevalence and years lived with disability for 371 diseases and injuries, and comparative risks for 88 risk factors across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021. In this study, we focused on the global disease burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 air pollution. Data were gathered from the Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/) [16]. All GBD 2021 analyses complied with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting statement. Ethical approval and informed consent were waived because GBD is publicly available and no identifiable information was included in the analyses.

PM2.5 air pollution estimation

PM2.5 air pollution includes both ambient (i.e., outdoor) and household (i.e., indoor) air pollution. Detailed information on data collection and input process could be found in the previously published paper [9]. In brief, ambient PM2.5 pollution is defined as the population-weighted annual gridded average PM2.5 mass concentration at a spatial resolution of 0.1° × °0.1°. A combination of chemical transport model simulations, satellite retrievals of aerosol optical depth, ground monitoring data, population data, and land use data was applied. Data Integration Model for Air Quality 2 was used to estimate the ambient PM2.5 concentrations for all regions in GBD 2021. Household air pollution is defined based on the prevalence of individuals using solid cooking fuels and the corresponding levels of PM2.5 among these individuals. Solid fuels in the present study include wood, coal/charcoal, dung, and agricultural residues. A three-step modelling strategy implementing linear regression, spatiotemporal regression, and Gaussian process regression was applied to estimate household PM2.5 pollution from solid fuels.

Health outcome definition

In this study, CVD included ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, as defined in the GBD framework [1, 9]. Other CVD subtypes were not included in the GBD estimates of PM2.5-related disease burden due to limited evidence on their associations with PM2.5 air pollution. Stroke was further categorized into three subtypes: (1) ischemic stroke; (2) intracerebral hemorrhage; and (3) subarachnoid hemorrhage. We focused on early-onset CVD, which is defined as CVD occurring among individuals under 50 years. Notably, GBD 2021 calculated the CVD burden for ages 25 + as in previous cycles. Therefore, our analysis specifically targeted individuals aged 25 to 49 years. This population was further divided into 5-year age subgroups in GBD 2021: 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years, and 45–49 years.

Disease burden attributable to PM2.5 air pollution

In GBD 2021, the cause-specific burden of a risk factor was evaluated by calculating the attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). For the estimation of the CVD burden attributable to PM2.5 exposure, a separate risk curve was first generated for each of the cardiovascular outcomes and applied across all age groups [9]. Specifically, the relative risk estimates for PM2.5 and cardiovascular disease were derived from high-quality epidemiological studies that systematically adjusted for major confounders [9]. The meta-regression—Bayesian, regularized, trimmed meta-regression tool was then utilized to create pooled relative risk estimates. The burden attributable to both ambient and household PM2.5 exposure was calculated jointly. Additionally, the theoretical minimum-risk exposure level was assigned a uniform distribution, with lower and upper bounds determined by the average of the minimum and 5th percentiles of PM2.5 exposure distributions in outdoor air pollution cohort studies conducted in North America. This is based on the assumption that current evidence was insufficient to precisely characterize the shape of the concentration–response function below the 5th percentile of the exposure distributions. The resulting lower/upper bounds of the distribution were 2.4 and 5.9 µg/m3, respectively.

Statistical analyses

We calculated age-standardized death and DALY rates (per 100,000 population) for CVD attributable to PM2.5 among individuals aged 25–49 years by using the same approach reported previously [2, 17]. Specifically, we extracted age-specific (i.e., 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years, and 45–49 years) crude death and DALY rates for each location from the GBD Results Tool (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). We then applied the direct standardization method to calculate the age-standardized rates for each location based on the world standard population in GBD 2021 [18]. The formula was as follows:

| 1 |

where is the age-specific crude rate in a certain location, is the weight of the same age subgroup in the standard population, refers to the th age class, and k is the total number of age groups [17]. To estimate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for age-standardized rates, we used the “ageadjust.direct” function in the “epitools” package in R, which implements the method based on the gamma distribution proposed by Fay and Feuer [19]. Numbers and percentages of deaths and DALYs from early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 were also calculated. The number of deaths and DALYs attributable to PM2.5 was calculated by summing age-specific estimates within the 25–49 age range that were extracted from the GBD Results Tool. The attributable percentage was then derived by dividing the attributable number by the total number of CVD deaths or DALYs within the 25–49 age range. We applied the same methods to estimate the CVD burden among individuals aged 50 years and older (defined as late-onset CVD in this study), to allow comparative analyses between early- and late-onset CVDs. We further calculated the burden for each 5-year age interval from 25 to 95 years, as well as for those aged 95 years and above, to provide a more detailed age-specific profile.

To assess the temporal trend of CVD burden attributable to PM2.5, we calculated estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) of death and DALYs rates, as well as the corresponding 95% CIs by using a log-linear model. In addition, the annual percent change and average annual percent change (AAPC) of death and DALYs rates were calculated by using Joinpoint regression model, and the corresponding 95% CIs were constructed by the Empirical Quantile Method.

Comprehensive comparisons were conducted between sexes, age groups (i.e., 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years, and 45–49 years), disease subtypes, regions with different levels of SDI (i.e., high, high-middle, middle, low-middle, and low SDI), and countries. We further examined the possible linear or non-linear relations between SDI and age-standardized rates for the 21 GBD regions (i.e., South Asia, East Asia, North Africa and Middle East, Western Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Latin America, Tropical Latin America, Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Europe, High-income North America, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Southern Sub-Saharan Africa, High-income Asia Pacific, Central Europe, Andean Latin America, Caribbean, Southern Latin America, Oceania, and Australasia) by using smoothing splines models [20].

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2) with “epitools” and “ggplot2” packages, and Joinpoint Regression Program (version 5.1.0). A p value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Global trends

In 2021, there were 304.01 (95% uncertainty interval [UI], 249.78–361.33) thousand deaths of early-onset CVD attributable to total PM2.5 pollution, 176.72 (123.61–224.98) thousand deaths to ambient exposure, and 127.25 (78.20–199.94) thousand deaths to household exposure from solid fuels (Additional file 1: Table S1). The age-standardized death rates of early-onset CVD attributable to total, ambient, and household PM2.5 were 10.93 (95% CI, 10.89–10.97), 6.35 (6.32–6.38), and 4.58 (4.55–4.60) per 100,000 population, respectively (Table 1). IHD accounted for a significant proportion among the total deaths of early-onset CVD. Specifically, the age-standardized death rates of early-onset IHD attributable to total PM2.5 exposure were 6.98 (6.95–7.01) per 100,000, while that of stroke was 3.95 (3.93–3.97) per 100,000. Similar patterns of results were also found for DALYs.

Table 1.

Age-standardized death and DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes

| Deaths (per 100,000) | DALYs (per 100,000) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PM2.5 pollution (95% CI) | Ambient PM2.5 pollution (95% CI) | Household PM2.5 from solid fuels (95% CI) | Total PM2.5 pollution(95% CI) | Ambient PM2.5 pollution(95% CI) | Household PM2.5 from solid fuels (95% CI) | |

| Global | 10.93 (10.89, 10.97) | 6.35 (6.32, 6.38) | 4.58 (4.55, 4.60) | 562.12 (561.84, 562.39) | 326.48 (326.27, 326.70) | 235.55 (235.37, 235.73) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 14.76 (14.70, 14.83) | 9.09 (9.04, 9.14) | 5.68 (5.64, 5.72) | 746.51 (746.05, 746.96) | 459.30 (458.95, 459.66) | 287.09 (286.80, 287.37) |

| Female | 7.05 (7.00, 7.09) | 3.58 (3.55, 3.61) | 3.46 (3.43, 3.50) | 374.88 (374.55, 375.20) | 191.61 (191.38, 191.84) | 183.22 (182.99, 183.44) |

| Age group* | ||||||

| 25–29 | 2.67 (2.20, 3.16) | 1.47 (1.03, 1.89) | 1.20 (0.79, 1.81) | 183.79 (151.82, 216.93) | 100.79 (70.02, 128.86) | 82.97 (54.72, 123.29) |

| 30–34 | 5.06 (4.11, 6.01) | 2.91 (2.00, 3.72) | 2.15 (1.36, 3.33) | 313.79 (257.01, 371.24) | 180.48 (125.01, 231.01) | 133.27 (85.04, 206.61) |

| 35–39 | 8.46 (6.94, 10.10) | 4.97 (3.47, 6.33) | 3.49 (2.15, 5.54) | 476.04 (392.94, 564.81) | 279.76 (195.99, 356.46) | 196.20 (122.10, 309.34) |

| 40–44 | 16.47 (13.50, 19.59) | 9.55 (6.69, 12.24) | 6.92 (4.21, 10.87) | 829.42 (684.90, 985.04) | 481.49 (336.08, 615.24) | 347.81 (212.65, 545.81) |

| 45–49 | 27.00 (22.30, 32.05) | 15.81 (11.08, 20.00) | 11.19 (6.80, 17.69) | 1221.61 (1004.68, 1445.49) | 716.32 (505.32, 907.86) | 505.10 (308.28, 797.76) |

| SDI level | ||||||

| High | 2.52 (2.47, 2.57) | 2.51 (2.46, 2.56) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 133.49 (133.13, 133.85) | 133.18 (132.82, 133.54) | 0.30 (0.29, 0.32) |

| High-middle | 5.93 (5.87, 6.00) | 5.53 (5.47, 5.60) | 0.40 (0.38, 0.42) | 312.44 (311.96, 312.93) | 291.44 (290.98, 291.91) | 20.94 (20.81, 21.06) |

| Middle | 10.65 (10.58, 10.71) | 8.25 (8.19, 8.31) | 2.40 (2.36, 2.43) | 548.32 (547.84, 548.80) | 424.05 (423.63, 424.47) | 124.15 (123.92, 124.38) |

| Low-Middle | 18.52 (18.42, 18.63) | 8.09 (8.02, 8.16) | 10.43 (10.35, 10.51) | 936.23 (935.47, 936.98) | 408.13 (407.63, 408.63) | 527.98 (527.41, 528.55) |

| Low | 16.77 (16.61, 16.92) | 3.42 (3.35, 3.49) | 13.34 (13.21, 13.48) | 851.25 (850.17, 852.33) | 172.68 (172.19, 173.17) | 678.52 (677.56, 679.49) |

| Cause | ||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 6.98 (6.95, 7.01) | 4.30 (4.28, 4.33) | 2.68 (2.66, 2.70) | 343.88 (343.66, 344.10) | 211.88 (211.71, 212.05) | 131.95 (131.81, 132.08) |

| Stroke | 3.95 (3.93, 3.97) | 2.05 (2.03, 2.07) | 1.90 (1.88, 1.92) | 218.24 (218.06, 218.41) | 114.60 (114.48, 114.73) | 103.60 (103.48, 103.72) |

| Ischemic stroke | 0.55 (0.54, 0.56) | 0.34 (0.33, 0.34) | 0.21 (0.21, 0.22) | 42.24 (42.16, 42.31) | 25.43 (25.37, 25.49) | 16.80 (16.75, 16.85) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 2.88 (2.86, 2.90) | 1.44 (1.43, 1.46) | 1.44 (1.42, 1.45) | 146.83 (146.69, 146.97) | 73.97 (73.87, 74.07) | 72.84 (72.74, 72.94) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 0.52 (0.51, 0.53) | 0.27 (0.26, 0.27) | 0.25 (0.25, 0.26) | 29.17 (29.11, 29.23) | 15.20 (15.16, 15.25) | 13.96 (13.92, 14.01) |

DALY disability adjusted life year, PM2.5 fine particulate matter, SDI sociodemographic index, CI confidence interval

*Values in parentheses for age-specific rates are 95% uncertainty intervals

From 1990 to 2021, the global disease burden of early-onset CVD attributable to total and household PM2.5 decreased substantially, with EAPCs in age-standardized death rates of − 1.56% (95% CI, − 1.68% to − 1.45%) and − 3.22% (− 3.48% to − 2.96%), respectively, and corresponding AAPCs of − 1.54% (− 1.66% to − 1.48%) and − 2.95% (− 3.00% to − 2.92%) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). However, the disease burden attributable to ambient PM2.5 pollution exhibited an overall increasing trend during this period, with EAPCs in age-standardized death and DALY rates of 0.37% (0.23%–0.52%) and 0.43% (0.29%–0.58%), respectively, and corresponding AAPCs of 0.09% (− 0.02% to 0.17%) and 0.14% (0.04%–0.23%). The age-standardized death and DALY rates attributable to ambient PM2.5 pollution exceeded those from household PM2.5 pollution since 2012. Though beginning to decline since 2014, ambient PM2.5-related burden remains higher. The trends were largely consistent across different CVD subtypes.

Table 2.

Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death and DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes

| Death (%) | DALYs (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PM2.5 pollution (95% CI) | Ambient PM2.5 pollution (95% CI) | Household PM2.5 from solid fuels (95% CI) | Total PM2.5 pollution(95% CI) | Ambient PM2.5 pollution(95% CI) | Household PM2.5 from solid fuels (95% CI) | |

| Global | − 1.56 (− 1.68, − 1.45) | 0.37 (0.23, 0.52) | − 3.22 (− 3.48, − 2.96) | − 1.54 (− 1.65, − 1.42) | 0.43 (0.29, 0.58) | − 3.20 (− 3.47, − 2.94) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | − 1.28 (− 1.42, − 1.13) | 0.45 (0.30, 0.61) | − 3.01 (− 3.32, − 2.69) | − 1.25 (− 1.39, − 1.11) | 0.51 (0.36, 0.66) | − 3.00 (− 3.32, − 2.68) |

| Female | − 2.09 (− 2.16, − 2.02) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.38) | − 3.52 (− 3.70, − 3.34) | − 2.03 (− 2.11, − 1.96) | 0.31 (0.18, 0.45) | − 3.49 (− 3.68, − 3.31) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 25–29 | − 1.38 (− 1.54, − 1.22) | 0.86 (0.66, 1.05) | − 3.08 (− 3.39, − 2.78) | − 1.39 (− 1.54, − 1.24) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.06) | − 3.10 (− 3.40, − 2.81) |

| 30–34 | − 1.28 (− 1.43, − 1.13) | 0.84 (0.69, 0.99) | − 2.98 (− 3.34, − 2.63) | − 1.29 (− 1.44, − 1.14) | 0.85 (0.70, 1.00) | − 3.01 (− 3.36, − 2.66) |

| 35–39 | − 1.49 (− 1.63, − 1.35) | 0.44 (0.29, 0.59) | − 3.12 (− 3.44, − 2.80) | − 1.48 (− 1.62, − 1.34) | 0.47 (0.33, 0.62) | − 3.13 (− 3.45, − 2.81) |

| 40–44 | − 1.57 (− 1.68, − 1.47) | 0.31 (0.18, 0.43) | − 3.18 (− 3.42, − 2.94) | − 1.56 (− 1.66, − 1.46) | 0.34 (0.22, 0.46) | − 3.18 (− 3.42, − 2.94) |

| 45–49 | − 1.68 (− 1.80, − 1.56) | 0.23 (0.07, 0.40) | − 3.35 (− 3.58, − 3.12) | − 1.65 (− 1.77, − 1.54) | 0.28 (0.11, 0.45) | − 3.35 (− 3.58, − 3.11) |

| SDI level | ||||||

| High | − 2.35 (− 2.46, − 2.25) | − 1.96 (− 2.03, − 1.88) | − 15.77 (− 16.45, − 15.08) | − 2.20 (− 2.30, − 2.09) | − 1.80 (− 1.87, − 1.72) | − 15.60 (− 16.25, − 14.95) |

| High-middle | − 3.54 (− 3.89, − 3.18) | − 1.31 (− 1.62, − 0.99) | − 10.16 (− 11.32, − 8.98) | − 3.44 (− 3.77, − 3.10) | − 1.14 (− 1.44, − 0.84) | − 10.15 (− 11.30, − 8.98) |

| Middle | − 2.05 (− 2.20, − 1.90) | 1.19 (1.04, 1.34) | − 5.75 (− 6.35, − 5.15) | − 2.03 (− 2.18, − 1.88) | 1.23 (1.08, 1.38) | − 5.73 (− 6.33, − 5.13) |

| Low-middle | − 1.01 (− 1.13, − 0.88) | 1.72 (1.50, 1.94) | − 2.20 (− 2.46, − 1.94) | − 1.01 (− 1.13, − 0.88) | 1.72 (1.50, 1.94) | − 2.20 (− 2.46, − 1.94) |

| Low | − 1.08 (− 1.15, − 1.01) | 0.32 (0.05, 0.59) | − 1.37 (− 1.46, − 1.28) | − 1.04 (− 1.10, − 0.97) | 0.36 (0.09, 0.63) | − 1.33 (− 1.42, − 1.24) |

| Cause | ||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | − 0.96 (− 1.05, − 0.87) | 0.61 (0.47, 0.76) | − 2.57 (− 2.83, − 2.31) | − 0.93 (− 1.03, − 0.84) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.81) | − 2.56 (− 2.83, − 2.29) |

| Stroke | − 2.41 (− 2.57, − 2.24) | − 0.05 (− 0.25, 0.14) | − 3.96 (− 4.24, − 3.68) | − 2.30 (− 2.46, − 2.14) | 0.06 (− 0.12, 0.25) | − 3.88 (− 4.16, − 3.61) |

| Ischemic stroke | − 1.82 (− 2.00, − 1.64) | 0.30 (0.09, 0.51) | − 3.79 (− 4.12, − 3.46) | − 1.52 (− 1.67, − 1.37) | 0.63 (0.45, 0.81) | − 3.45 (− 3.76, − 3.15) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | − 2.30 (− 2.50, − 2.09) | 0.19 (− 0.04, 0.42) | − 3.82 (− 4.13, − 3.51) | − 2.28 (− 2.48, − 2.08) | 0.21 (− 0.02, 0.43) | − 3.81 (− 4.13, − 3.50) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | − 3.45 (− 3.57, − 3.33) | − 1.51 (− 1.69, − 1.33) | − 4.80 (− 4.94, − 4.66) | − 3.27 (− 3.38, − 3.17) | − 1.29 (− 1.46, − 1.13) | − 4.66 (− 4.80, − 4.52) |

DALY disability adjusted life year, PM2.5 fine particulate matter, SDI sociodemographic index, CI confidence interval

Fig. 1.

Trends for early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally from 1990 to 2021. A Death rate. B DALY rate. Abbreviations: PM2.5, fine particulate matter; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; APC, annual percent change

Global trends by sex

Significant differences in the disease burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 pollution were observed between males and females. Specifically, the age-standardized death rate attributable to total PM2.5 pollution was 14.76 (14.70–14.83) per 100,000 among males, nearly double that of females (7.05 [7.00–7.09] per 100,000). For ambient PM2.5, the burden among males was nearly 2.5 times that among females, whereas for household PM2.5, it was approximately 1.5 times as high in males as in females (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Similar patterns were also found for DALY rates, as well as the absolute numbers of deaths and DALYs (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1 and Figure S1).

Fig. 2.

Number and rate of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally in 2021, by age and sex. Abbreviations: PM2.5, fine particulate matter; UI, uncertainty interval

From 1990 to 2021, the reduction in age-standardized death and DALY rates of early-onset CVD attributable to total and household PM2.5 was more pronounced in females than in males (Table 2). The burden attributable to ambient PM2.5 pollution increased in both sexes, and a greater increase was observed among males.

Global trends by age

The burden of early-onset and late-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 pollution exhibited notable differences. In general, the attributable burden was higher among individuals aged 50 and above compared to those under 50 (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1–S3). Analyses stratified by 5-year age intervals also indicate that the burden was higher in older individuals and generally increased with age.

From 1990 to 2021, both early-onset and late-onset CVD attributable to total and household PM2.5 pollution showed a declining trend (Table 2, Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Table S4 and Figure S2–S4). The reduction was smaller in early-onset CVD compared to that of late-onset cases. For example, the EAPC during 1990–2021 in age-standardized death rates attributable to total PM2.5 was − 1.56% (− 1.68% to − 1.45%) for individuals under 50, compared to − 1.95% (− 2.08% to − 1.81%) for those over 50. Notably, the burden of early-onset CVD attributable to ambient PM2.5 increased during this period, whereas that of the late-onset cases decreased. Similarly, further analyses stratified by 5-year age intervals revealed that the declines were more pronounced among middle-aged and older adults than younger populations.

Global trends by SDI

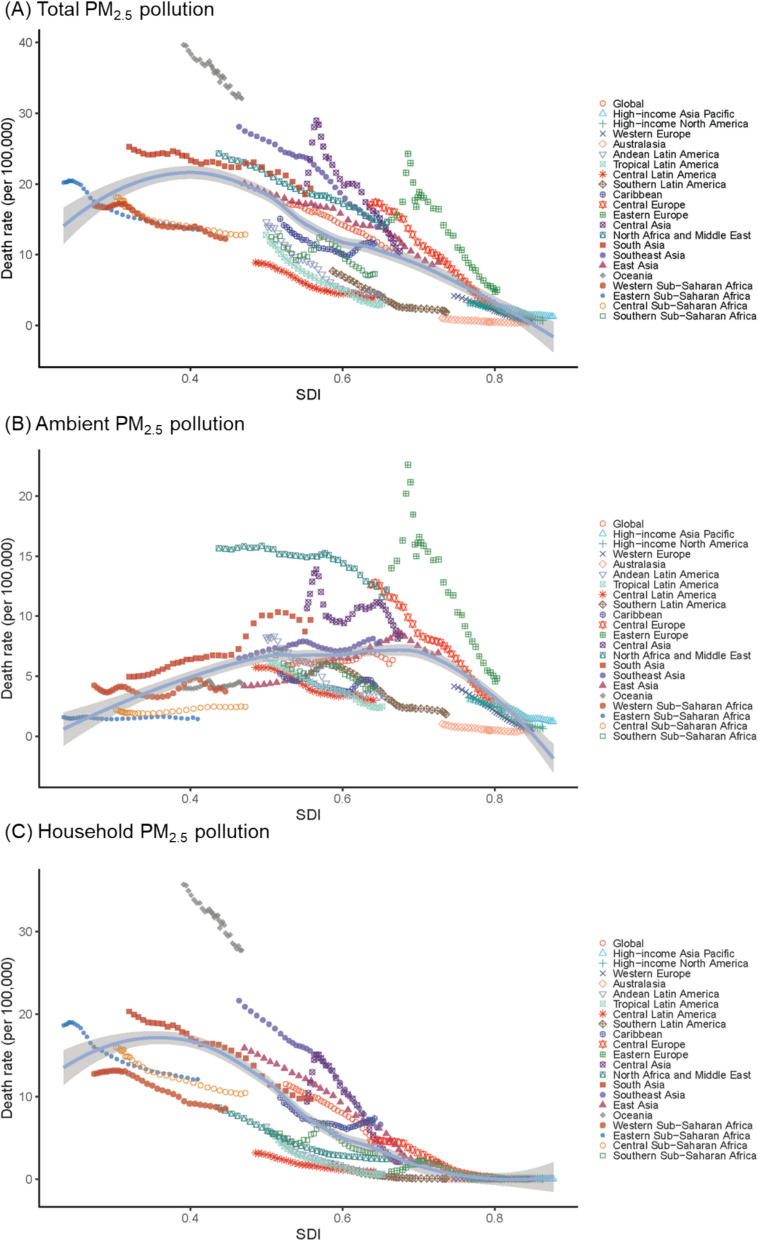

There were considerable disparities in the disease burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 across different SDI regions in 2021 (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). Regions with lower SDI levels showed a higher burden attributable to total and household PM2.5, while middle-SDI regions exhibited the highest burden attributable to ambient PM2.5. At the regional level, we found a reversed U-shaped association between SDI and the age-standardized death and DALY rates of early-onset CVD attributable to ambient PM2.5 (Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Figure S5). The rate increased with rising SDI at the lower end, reaching a peak at around 0.7, and began to decline thereafter. In contrast, the disease burden attributable to household PM2.5 pollution showed a generally decreasing trend as SDI levels increased.

Fig. 3.

Age-standardized death rates (per 100,000) of early-onset cardiovascular disease attributable to PM2.5 air pollution for the 21 Global Burden of Disease regions in 2021, by sociodemographic index. Abbreviation: PM2.5, fine particulate matter

From 1990 to 2021, there was a declining trend in the disease burden attributable to total and household PM2.5 across most regions (Additional file 1: Figure S6–S7). EAPCs in age-standardized death rates were the highest in high-middle SDI region (− 3.54% [− 3.89% to − 3.18%]) for total PM2.5, and in high-SDI region (− 15.77% [− 16.45% to − 15.08%]) for household PM2.5 (Table 2). In contrast, the temporal changes in burden attributable to ambient PM2.5 pollution varied across different SDI levels. Specifically, in high-SDI regions, a slight decrease in the burden was observed over time. In high-middle and middle-SDI regions, the disease burden showed an increasing trend until around 2014, after which it began to decline. Meanwhile, in low-middle and low SDI regions, the burden showed an overall increasing trend throughout the period.

Global trends by countries

In 2021, the early-onset CVD burden attributable to total PM2.5 pollution was predominantly observed in Asian and African countries. Specifically, countries in North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia experienced a significantly higher burden attributable to ambient PM2.5 pollution, while the burden from household PM2.5 pollution was mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Figure S8–S10). Among 204 countries, Vanuatu had the highest burden from total and household PM2.5, with age-standardized death rates of 67.04 (51.32–86.10) and 61.27 (46.30–79.60) per 100,000, respectively. Egypt had the highest age-standardized death rate (27.31 [26.75–27.88] per 100,000) from ambient PM2.5.

Fig. 4.

Age-standardized death rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Abbreviation: PM2.5, fine particulate matter

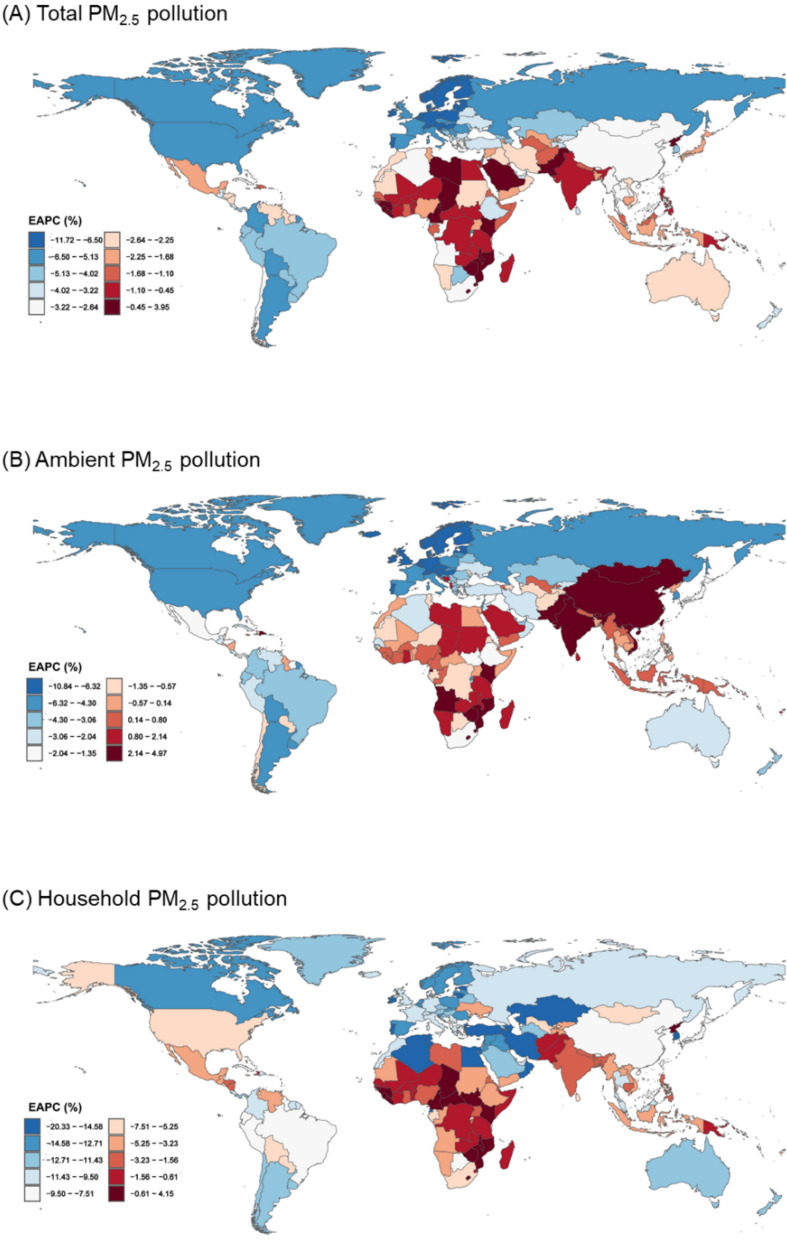

From 1990 to 2021, the burden of early-onset CVD attributable to total and household PM2.5 pollution showed a decreasing trend in most countries globally, except some in Africa (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Figure S11). In specific, Zimbabwe had the highest increase, with EAPCs in standardized death rates of 3.95% (2.82%–5.09%) for total PM2.5 pollution and 4.15% (3.01%–5.31%) for household PM2.5 pollution. Meanwhile, the largest decrease in standardized death rates attributable to total and household PM2.5 pollution was observed in Estonia (EAPC, − 11.72% [− 12.44% to − 10.99%]) and Republic of Korea (EAPC, − 20.33% [− 21.48% to − 19.17%]), respectively. For ambient PM2.5 pollution, the burden increased most significantly in East Asia, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, countries in Europe and North America experienced the most substantial declines.

Fig. 5.

Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by country. Abbreviations: PM2.5, fine particulate matter; EAPC, estimated annual percentage change

Discussion

This study provides an up-to-date evaluation on the global, regional, and national burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 from 1990 to 2021. Males, individuals living in regions with lower SDI, and those with IHD experience a higher burden. Over the past three decades, there was a substantial decrease in early-onset CVD burden attributable to total and household PM2.5, especially in regions with higher SDI. However, the corresponding burden from ambient PM2.5 continued to rise and only began to decline since the last decade. In addition, the reduction in early-onset CVD burden was less prominent than that of late-onset CVD. Such findings underscore that even in the context of global population aging, the PM2.5-related early-onset CVD burden remains a critical concern.

Most previous studies focused on the overall CVD burden attributable to PM2.5, with few age-specific analyses and insufficient attention to younger populations [13, 15, 21]. Besides, there has been a decreasing trend in the all-age CVD death and DALY rates attributable to both ambient and household PM2.5 exposure over the past three decades [9]. However, how the early-onset CVD burden varied across different regions and time periods remains unclear. Our study is the first to fill this gap by conducting a comprehensive analysis of early-onset CVD burden attributable to PM2.5 from 1990 to 2021 at the global level. We also present the late-onset CVD burden and age-specific burden by 5-year intervals. The results show that the attributable burden was consistently higher in older age groups, suggesting their greater susceptibility. Interestingly, while the burden of both early- and late-onset CVD from total and household PM2.5 has declined, the reduction in the early-onset burden is smaller compared to the late-onset burden. Additionally, in contrast to the decline in late-onset CVD burden, the early-onset CVD burden due to ambient PM2.5 even increased slightly. This suggests a need for sustained attention to younger populations who may experience slower improvements despite lower absolute burden.

Our study reveals obvious sexual differences in the burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 pollution. In general, males experience a higher burden compared to females, which is consistent with higher PM2.5-related CVD risk among males reported in previous researches [22–24]. This between-sex difference is more pronounced for ambient PM2.5 pollution and less prominent for household PM2.5. Several factors might contribute to this heterogeneity. First, there is generally a higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors among males, such as hypertension, alcohol consumption, and smoking, which contributed to a higher overall CVD burden [9, 25, 26]. Second, social and occupational factors might also play an important role. Men are more likely to engage in outdoor labor-intensive work, leading to greater exposure to ambient air pollution. Conversely, women are more often exposed to indoor air pollution due to their involvement in household tasks such as cooking [27, 28]. These results underscore the importance of accounting for sex-specific exposure patterns when designing public health policies aimed at reducing PM2.5-related disease burdens. Reducing ambient PM2.5 exposure is particularly important for mitigating CVD burden among men, while minimizing both ambient and indoor exposure would be equally crucial for women.

Substantial variations by SDI were illustrated in the burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 pollution. Similar to patterns observed in studies on other non-communicable diseases [29], a reversed U-shaped association was found between SDI and the early-onset CVD burden attributable to ambient PM2.5. In contrast, the corresponding burden due to household PM2.5 showed a generally decreasing trend as SDI increased. Low-SDI regions in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia faced the highest burden from household PM2.5, while middle-SDI regions in North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia experienced the greatest burden from ambient PM2.5. This pattern could be explained by the regional economic and environmental differences. Specifically, low-SDI countries, largely dependent on solid fuels, have higher household PM2.5 exposure, whereas middle-SDI countries face increased ambient pollution due to rapid urbanization and industrialization [30, 31]. High-SDI regions had the lowest burden from both ambient and household PM2.5, which might be largely due to the use of cleaner energy, stricter environmental regulations, more resources of individual protective measures, and improved public health and clinical systems. These regional differences underscore the critical influence of socioeconomic development on the early-onset CVD burden attributable to PM2.5 pollution.

To effectively mitigate the early-onset CVD burden due to PM2.5 pollution, tailored air quality policies and interventions based on regional economic and environmental contexts are warranted. In low-SDI countries, international cooperation is essential, including technology transfer to promote clean cooking stoves, clean energy use, and improved household ventilation. Global financial support is also needed to subsidize infrastructure upgrades and clean energy transitions. For middle-SDI countries undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization, stringent air quality management plans including tightening industrial emission standards, expanding public transportation systems, and promoting clean energy transitions are needed. High-SDI countries, while facing relatively lower PM2.5 burdens, should continue strengthening environmental regulations, advancing control technologies, and investing in long-term pollutant management. They can also play a leading role in supporting global air pollution control efforts through research collaboration, funding, and cross-border policy communication.

The health effects and corresponding disease burden attributable to PM2.5 may also vary depending on its chemical composition and sources, which differ substantially across regions [32]. Previous studies reported that carbonaceous components and PM2.5 from fossil fuel combustion might pose higher cardiovascular risks [33–36], which could theoretically contribute to a higher disease burden. However, due to data limitations, our analysis focused on total PM2.5 mass and did not account for the heterogeneity in chemical constituents and sources. This limitation may also contribute to uncertainties in regional burden estimates. Future studies integrating data on PM2.5 chemical composition and source-specific toxicity are warranted to improve the precision of disease burden estimates and guide more targeted interventions.

Over the past three decades, there has been a significant decrease in the early-onset CVD burden attributable to total and household PM2.5 pollution, especially in regions with higher SDI levels. In contrast, the burden from ambient PM2.5 slightly increased at the global level, which was mainly driven by increasing burden in less-developed regions [31]. Since the year 2012, early-onset CVD burden from ambient PM2.5 has exceeded that from household PM2.5, and became the primary contributor to PM2.5-related burden. This shift illustrates the effectiveness of the global efforts in promoting cleaner energy sources including natural gas and electricity for household use, and emphasizes that stricter actions especially on ambient PM2.5 pollution are needed to reduce CVD burden in the future.

This study provides a comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation on the global, regional, and national distributions and temporal trends of early-onset CVD burden from PM2.5 exposure. Our findings offer scientific guidance for multiple fields, including public health, clinical practice, and environmental health policy, in developing targeted interventions and management strategies to promote global cardiovascular health.

There are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, PM2.5 is a complex mixture comprising multiple constituents, each with distinct physicochemical properties [37]. The composition of PM2.5 can vary significantly by source, season, and region [38, 39]. However, the GBD 2021 study assumes spatial homogeneity in PM2.5 composition, potentially leading to inaccurate estimations in specific locations [29]. Future studies should take the heterogeneity of PM2.5 composition and source into consideration when evaluating the disease burden attributable to PM2.5. Second, our assessment of household PM2.5 pollution did not account for solid fuel use for heating, which is also an important contributor to indoor air pollution and a known risk factor for CVD [9, 40]. Thus, future studies should explore the contribution of solid fuel use for heating to the disease burden attributable to household PM2.5 pollution. Third, the effect estimates in this study rely on available epidemiological datasets, which might be limited in many low- and middle-income regions. Issues such as underdiagnosis and inadequate health care access could lead to biases in the estimation. Fourth, the current GBD 2021 dataset only evaluates burden of IHD as an aggregated category. Therefore, we were unable to estimate the disease burden by finer subtypes of IHD such as acute myocardial infarction, angina, or chronic IHD separately. In addition, most existing cohort studies on air pollution have focused on overall IHD rather than its specific subtypes, leading to insufficient evidence supporting more detailed burden estimation. Therefore, future studies with finer disease categories are warranted and would be valuable to inform targeted interventions. Last, while the relative risk estimates used in GBD 2021 were derived from epidemiological studies that adjusted for major confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured factors may still exist. In addition, potential interactions and mediation among different risk factors are not fully captured in these models. Future studies incorporating more detailed covariate data and advanced analytical methods are needed to better account for residual confounding and to explore these complex relationships.

Conclusions

Over the past three decades, the global burden of early-onset CVD attributable to PM2.5 pollution has become a critical public health concern, even in the context of global population aging. Males, individuals in lower-SDI regions, and those with IHD experienced disproportionately higher burden. Although the burden attributable to household PM2.5 has decreased substantially, that from ambient PM2.5 remains high and has only started to decline since the past decade. Geographically tailored and population-specific interventions are urgently needed to promote precise prevention and risk management for early-onset CVD and to mitigate the long-term burden globally.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Death and DALY numbers of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S2. Age-standardized death and DALY rates of cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S3. Death and DALY numbers of early-onset cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S4. Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death and DALY rates of cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Figure S1. Number and rate of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally in 2021, by age and sex. Figure S2. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by age. Figure S3. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by age. Figure S4. Trends for cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally from 1990 to 2021. Figure S5. Age-standardized DALY rates (per 100,000) of early-onset cardiovascular disease attributable to PM2.5 air pollution for the 21 Global Burden of Disease regions in 2021, by sociodemographic index. Figure S6. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by SDI levels. Figure S7. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by SDI levels. Figure S8. Age-standardized DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S9. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S10. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S11. Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by country.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 collaborators for their valuable contributions and efforts.

Abbreviations

- AAPC

Average annual percent change

- CI

Confidence interval

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life-year

- EAPC

Estimated annual percentage change

- GBD

Global Burden of Disease Study

- IHD

Ischemic heart disease

- PM2.5

Fine particulate matter

- SDI

Sociodemographic index

- UI

Uncertainty interval

Authors’ contributions

YJ contributed to the study design, data analysis, funding acquisition, and drafting and editing of the manuscript. HL, GF, and JC contributed to the interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. HK and RC contributed to the conception, study design, funding acquisition, review and editing of the manuscript. HK and RC contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3702701 and 2023YFC3709403), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82030103), Shanghai Sailing Program (24YF2706700), and the Collaborating Program of Fudan-Minhang Academic Health System (2023FM11).

Data availability

Data used in this study were obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange Global Burden of Disease Results Tool (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval and informed consent were waived because the Global Burden of Disease database is publicly available and no identifiable information was included in the analyses.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haidong Kan, Email: kanh@fudan.edu.cn.

Renjie Chen, Email: chenrenjie@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024; 18;403(10440):2100–32. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sun J, Qiao Y, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases in youths and young adults aged 15-39 years in 204 countries/territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):222. 10.1186/s12916-023-02925-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2019 Adolescent Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10-24 years, 1950-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1593-618. 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01546-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson C, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in young individuals. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(4):230-40. 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Joint impact of polygenic risk score and lifestyles on early- and late-onset cardiovascular diseases. Nat Hum Behav. 2024;8(9):1810-8. 10.1038/s41562-024-01923-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vikulova DN, Grubisic M, Zhao Y, Lynch K, Humphries KH, Pimstone SN, et al. Premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: trends in incidence, risk factors, and sex-related differences, 2000 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(14):e012178. 10.1161/jaha.119.012178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole JH, Miller JI, 3rd, Sperling LS, Weintraub WS. Long-term follow-up of coronary artery disease presenting in young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(4):521-8. 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02862-0. 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02862-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeitouni M, Clare RM, Chiswell K, Abdulrahim J, Shah N, Pagidipati NP, et al. Risk factor burden and long-term prognosis of patients with premature coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(24):e017712. 10.1161/jaha.120.017712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2162-203. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00933-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang F, Liu F, Huang K, Yang X, Li J, Xiao Q, et al. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and cardiovascular disease in China. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(7):707-17. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexeeff SE, Deosaransingh K, Van Den Eeden S, Schwartz J, Liao NS, Sidney S. Association of long-term exposure to particulate air pollution with cardiovascular events in California. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e230561. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pope CA, Lefler Jacob S, Ezzati M, Higbee Joshua D, Marshall Julian D, Kim S-Y, et al. Mortality risk and fine particulate air pollution in a large, representative cohort of U.S. adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(7):77007. 10.1289/EHP4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Khoshakhlagh AH, Mohammadzadeh M, Gruszecka-Kosowska A, Oikonomou E. Burden of cardiovascular disease attributed to air pollution: a systematic review. Global Health. 2024;20(1):37. 10.1186/s12992-024-01040-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira de Oliveira Salerno PR, Briones-Valdivieso C, Motairek I, Palma Dallan LA, Rajagopalan S, Deo SV, et al. The cardiovascular disease burden attributable to particulate matter pollution in South America: analysis of the 1990-2019 global burden of disease. Public Health. 2023;224:169-77. 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Liu YH, Bo YC, You J, Liu SF, Liu MJ, Zhu YJ. Spatiotemporal trends of cardiovascular disease burden attributable to ambient PM(2.5) from 1990 to 2019: a global burden of disease study. Sci Total Environ. 2023;885:163869. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Data Resources. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/. Accessed 16 May 2024.

- 17.Yang K, Yang X, Jin C, Ding S, Liu T, Ma B, et al. Global burden of type 1 diabetes in adults aged 65 years and older, 1990-2019: population based study. BMJ. 2024;385:e078432. 10.1136/bmj-2023-078432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GBD 2021 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population estimates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950-2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):1989–2056. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00476-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fay MP, Feuer EJ. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat Med. 1997;16(7):791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu L, Tian T, Wang B, Lu Z, Bian J, Zhang W, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in older adults aged 60-89 years from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5(1):e17–e30. 10.1016/s2666-7568(23)00214-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Zhang H, Zou Z. Changing profiles of cardiovascular disease and risk factors in China: a secondary analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Chin Med J. 2023;136(20):2431-41. 10.1097/cm9.0000000000002741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexeeff SE, Deosaransingh K, Liao NS, Van Den Eeden SK, Schwartz J, Sidney S. Particulate matter and cardiovascular risk in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(2):159-67. 10.1164/rccm.202007-2901OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beelen R, Stafoggia M, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Xun WW, Katsouyanni K, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and cardiovascular mortality: an analysis of 22 European cohorts. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):368-78. 10.1097/ede.0000000000000076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Q, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, Wang Y, Koutrakis P, Choirat C, et al. Air pollution and mortality in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2513-22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1702747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu T, Tang M, He B, Liu X, Han Y, Liu C, et al. Assessing global, regional, and national time trends and associated risk factors of the mortality in ischemic heart disease through Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study: population-based study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024;10:e46821. 10.2196/46821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin KF, Mejia MT. Household air pollution as a silent killer: women’s status and solid fuel use in developing nations. Population and Environment. 2017;39(1):1–25. 10.1007/s11111-017-0269-z [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin HH, Maquiling A, Thomson EM, Park IW, Stieb DM, Dehghani P. Sex-difference in air pollution-related acute circulatory and respiratory mortality and hospitalization. Sci Total Environ. 2022;806(Pt 3):150515. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sang S, Chu C, Zhang T, Chen H, Yang X. The global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;238:113588. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bu X, Xie Z, Liu J, Wei L, Wang X, Chen M, et al. Global PM2.5-attributable health burden from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of disease study 2017. Environ Res. 2021;197:111123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbasi-Kangevari M, Malekpour MR, Masinaei M, Moghaddam SS, Ghamari SH, Abbasi-Kangevari Z, et al. Effect of air pollution on disease burden, mortality, and life expectancy in North Africa and the Middle East: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7(5):e358-e69. 10.1016/s2542-5196(23)00053-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Leaderer BP, Gent JF, Lee HJ, Koutrakis P. Associations of PM₂.₅ constituents and sources with hospital admissions: analysis of four counties in Connecticut and Massachusetts (USA) for persons ≥ 65 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(2):138-44. 10.1289/ehp.1306656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Sarnat SE, Winquist A, Schauer JJ, Turner JR, Sarnat JA. Fine particulate matter components and emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in the St. Louis, Missouri-Illinois, metropolitan area. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(5):437-44. 10.1289/ehp.1307776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang Y, Du C, Chen R, Hu J, Zhu X, Xue X, et al. Differential effects of fine particulate matter constituents on acute coronary syndrome onset. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10848. 10.1038/s41467-024-55080-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman MM, Begum BA, Hopke PK, Nahar K, Newman J, Thurston GD. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associations with biomass- and fossil-fuel-combustion fine-particulate-matter exposures in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(4):1172-83. 10.1093/ije/dyab037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian Y, Ma Y, Wu J, Wu Y, Wu T, Hu Y, et al. Ambient PM(2.5) Chemical composition and cardiovascular disease hospitalizations in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2024;58(37):16327-35. 10.1021/acs.est.4c05718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly FJ, Fussell JC. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmos Environ. 2012;60:504-26. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.06.039 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Tian H, Zhang K, Liu S, Cheng K, Yin S, et al. Seasonal variation, formation mechanisms and potential sources of PM2.5 in two typical cities in the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration, China. Sci Total Environ. 2019;657:657-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinson A, Sidwell A, Black O, Roper C. Seasonal Variation in the chemical composition and oxidative potential of PM2.5. Atmosphere. 2020;11(10) 10.3390/atmos11101086 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu K, Qiu G, Chan KH, Lam KH, Kurmi OP, Bennett DA, et al. Association of solid fuel use with risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in rural China. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1351-61.10.1001/jama.2018.2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Death and DALY numbers of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S2. Age-standardized death and DALY rates of cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S3. Death and DALY numbers of early-onset cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Table S4. Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized death and DALY rates of cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, stratified by sex, age groups, SDI levels, and causes. Figure S1. Number and rate of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally in 2021, by age and sex. Figure S2. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by age. Figure S3. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by age. Figure S4. Trends for cardiovascular diseases among people aged over 50 years attributable to PM2.5 air pollution globally from 1990 to 2021. Figure S5. Age-standardized DALY rates (per 100,000) of early-onset cardiovascular disease attributable to PM2.5 air pollution for the 21 Global Burden of Disease regions in 2021, by sociodemographic index. Figure S6. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by SDI levels. Figure S7. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by SDI levels. Figure S8. Age-standardized DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S9. Percentage of deaths from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S10. Percentage of DALYs from early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution in 2021, by country. Figure S11. Estimated annual percentage change in age-standardized DALY rates of early-onset cardiovascular diseases attributable to PM2.5 air pollution from 1990 to 2021, by country.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study were obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange Global Burden of Disease Results Tool (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).