Abstract

Background

The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children is increasing, often presenting as co-occurring symptoms, yet screening for such co-occurrence remains inadequate. This study investigates repetitive negative thinking (RNT) as a transdiagnostic factor in the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety symptoms in children, aiming to develop novel early screening strategies.

Methods

Two cross-sectional surveys collected demographic information and self-reported measures of depression, anxiety, and RNT from primary school students in China. Structural equation modeling and network analysis were used to examine relationships among variables. Additionally, four machine learning algorithms (random forest, support vector machine, decision tree, and extreme gradient boosting) were applied to predict the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Results

RNT and its factors were significantly positively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms (r = 0.56–0.68, p < 0.001) and mediated 12.94% and 12.73% of their bidirectional relationship (with depression and anxiety as independent variables, respectively), with a same 95% CI: 8.78%–18.43% (p < 0.001). Network analysis revealed that RNT’s core features exhibited the highest bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence, indicating a critical mediating role in the co-occurrence of symptoms. The random forest model showed optimal predictive performance (AUC = 0.90, recall = 0.95), supporting its applicability for early screening.

Conclusion

RNT, particularly its core features, may play an important transdiagnostic role in the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety symptoms in children. This study provides an effective method for early screening in resource-limited settings, particularly in educational settings. Future research should validate the utility of RNT-targeted interventions, such as mindfulness-based therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-025-03169-y.

Keywords: Repetitive negative thinking, Depression, Anxiety, Transdiagnostic, Network analysis, Machine learning

Introduction

Depression and anxiety have become the most prevalent emotional disorders among children and adolescents, often occurring together, this phenomenon is often referred to as comorbidity [29]. Among Chinese children and adolescents, the comorbidity rate of depression and anxiety is 31.3% [84], with 52% of depressed adolescents also experiencing anxiety symptoms [12]. Children and adolescents with comorbid depression and anxiety face a greater life burden compared to those with either condition alone [63] and experience poorer treatment outcomes [1, 30]. Therefore, understanding the shared etiological pathways and interrelations of comorbid depression and anxiety is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Three pathways have been identified for the comorbidity of depression and anxiety. First, anxiety may lead to depression in individuals with anxiety vulnerability. Second, both disorders may occur simultaneously. Third, depression may lead to anxiety in individuals with depression vulnerability [18]. This comorbidity is related to both individual physiological and psychological vulnerabilities [85] and the shared characteristics of these disorders [57]. Children and adolescents, particularly those undergoing pubertal changes, are more vulnerable to comorbid depression and anxiety [60]. However, this issue remains under-recognized in clinical practice and research [51, 56]. In clinical settings, psychiatric diagnoses often rely on self-reported symptoms in patients [56], which demands high levels of clinical expertise [45, 78]. In China, factors such as a shortage of psychiatrists and the use of time-saving diagnostic methods lead to the underdiagnosis of comorbid depression and anxiety, significantly diminishing treatment efficacy [77]. The etiological complexity of comorbid depression and anxiety—encompassing genetic and environmental factors, individual characteristics, and emotion regulation strategies—poses great challenges in identifying accurate predictors [52]. To address these challenges, theoretical models of comorbidity are needed to be established to provide valuable insights into shared mechanisms that can inform the identification of transdiagnostic predictors.

The theoretical model of comorbidity provides a framework for understanding the mechanisms underlying the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety, facilitating the identification of transdiagnostic factors. The tripartite model suggests that depression and anxiety share common negative emotional components, such as irritability, restlessness, and poor concentration [75]. Additionally, the hierarchical model of mood disorders posits that higher-order factors, such as negative emotions, contribute to the overlap between these disorders [40]. These models highlight shared cognitive and emotional processes that transcend diagnostic boundaries, suggesting that transdiagnostic factors may explain the persistence and severity of comorbidity. Moreover, cognitive theories, particularly Beck’s cognitive triad, emphasize how negative perceptions of the self, the world, and the future in individuals with depression contribute to recurrent negative thought patterns, such as rumination, which in turn exacerbate anxiety by fostering anticipatory worry about potential future threats [2, 15, 74]. These repetitive cognitive processes have transdiagnostic significance, as they maintain and intensify the negative emotions associated with both disorders, suggesting that focusing on recurrent negative thinking may elucidate the shared mechanisms underlying comorbidity.

Repetitive negative thinking (RNT) may be a promising predictor of comorbid depression and anxiety. Defined as excessive, uncontrollable, and repetitive negative thoughts [21], RNT represents a transdiagnostic cognitive process implicated in the onset and persistence of depression and anxiety [59, 65]. Unlike other transdiagnostic factors like negative affect, the repetitive and uncontrollable nature of RNT distinguishes it as a unique cognitive process that can be consistently evaluated across disorders [22]. Although RNT has been extensively studied in relation to rumination in depression and worry in anxiety [10, 65], these investigations mainly focus on specific disorders, limiting the generalizability of RNT across diagnostic categories [19]. This study emphasizes perseverative thinking, which operates independently of specific emotional disorders, making it more appropriate for transdiagnostic assessment [22]. Recent studies have highlighted the transdiagnostic role of RNT in emotional disorders. For example, network analysis revealed that RNT is a core factor in depression, generalized anxiety disorder, loneliness, stress, and insomnia [80]. Another study using structural equation modeling showed that the core characteristics of RNT predict comorbid depression and anxiety better than rumination and worry alone [68]. However, these studies focused on total disorder scores, neglecting the importance of symptoms and their interrelations.

To better understand the role of symptoms in comorbid mental disorders, researchers have proposed network analysis [17], a visualization method that provides new insights into comorbidity pathways, overlapping symptoms, and diagnostic boundaries. The network structure consists of nodes (symptoms) and edges (connections between symptoms), with key metrics such as strength and expected influence indicating the importance of each symptom [7, 54]. Recent studies have identified core symptoms in depression and anxiety networks, such as restlessness, lack of energy, and excessive worry, as well as bridge symptoms that connect different disorders [37, 50]. Network analysis can map how RNT interacts with symptom levels of depression and anxiety, thereby providing a nuanced understanding of the transdiagnostic role of RNT. In developing countries with limited mental health resources (e.g., lack of specialized psychiatrists), the screening for comorbid depression and anxiety remains challenging [46]. Machine learning offers a potential solution by using algorithms to process input data and predict outcomes [31]. Previous studies have demonstrated the successful application of machine learning in predicting comorbidities such as panic disorder with agoraphobia [48] and ADHD with substance use disorders [83]. These studies suggest that machine learning may serve as a cost-effective approach for the early prediction of comorbid depression and anxiety in children and adolescents.

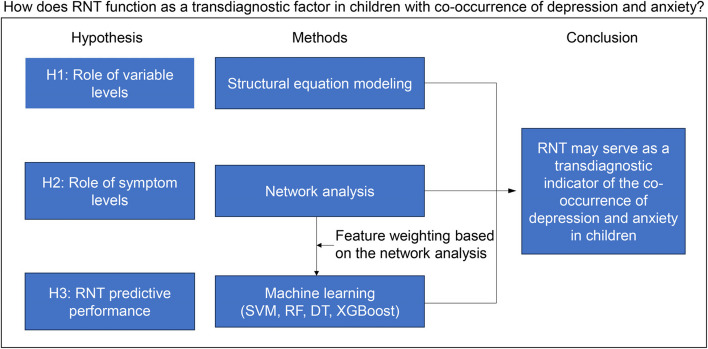

In summary, previous studies have explored RNT as a transdiagnostic marker for depression and anxiety [53, 80], and further insight may be gained by shifting the analytical focus from the variable level to the symptom level. Although prior work studies suggest that RNT plays a pivotal role in the transdiagnostic mechanisms of depression and anxiety, the extent of this role has not been thoroughly examined. Therefore, this study aims to further investigate the role and efficacy of RNT in the transdiagnostic process of depression and anxiety at the symptom level. We hypothesized that RNT may serve as a potential predictor, assisting in the early screening of comorbid depression and anxiety in primary and secondary schools, thereby laying a foundation for subsequent psychological interventions. Specifically, we hypothesize (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Overall research idea diagram. Note: RNT, repetitive negative thinking; SVM, support vector machine; RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; XGboost, eXtreme gradient boosting

H1: At the variable level, RNT can serve as a predictor for depression and anxiety, with a significant mediating effect on the bidirectional relationship between depression and anxiety (verified through structural equation modeling and mediation analysis).

H2: At the symptom level, RNT plays a crucial role in the relationship between depressive and anxiety symptoms network (validated through network analysis).

H3: Machine learning models trained on RNT-related features demonstrate strong performance in identifying children with co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety (verified through machine learning algorithms).

Methods

Participants and procedure

Dataset 1 was collected in May 2023 using convenience sampling from two primary schools in Sichuan, China. The survey was conducted using printed questionnaires by trained graduate students specializing in psychology, who distributed and collected questionnaires in each classroom. Considering the potential comprehension challenges among younger children, the study included only students in Grades 4–6. The survey materials were validated for this specific age group to ensure adequate understanding [26, 69, 76]. The study focused exclusively on children aged 10–15 years, excluding older adolescents aged 16 to 18 years, as mental health issues frequently emerge in early childhood yet remain under-addressed [27]. During the survey, the purpose and instructions of the questionnaire were explained to the students and their inquiries were addressed to ensure accurate responses. A total of 2,050 questionnaires were distributed, of which 2,012 were returned (response rate of 98.15%). After excluding blank or invalid questionnaires (1.64% of the total) and participants under 10 years old, 1,916 valid responses were included in the final analysis (valid response rate of 93.46%). The minimum sample size was determined based on the principle of 10 times the number of study variables [14].

Dataset 1 from Study 1 was used to train the machine learning model. Dataset 2 was collected in July 2024 through convenience sampling at an elementary school in Chongqing, China. It contains data from 208 students and serves as an external validation set for the machine learning model. The one-year interval between the two surveys is primarily based on the following scientific considerations: Compared to datasets collected during the same period, external validation datasets from different time points and centers allow for a more robust assessment of the model’s true predictive performance. This includes evaluating the model’s robustness against potential temporal variations (e.g., seasonal changes, evolution of clinical practice) and the stability of predictive performance over time (temporal validation). This design aligns with the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis type 2b validation standard (independent temporal external validation; [16]), which provides a higher level of evidence than purely spatial validation (i.e., different centers during the same period).

Data collection was conducted via the online survey platform “Wenjuanxing” (www.wjx.cn), with the survey content identical to that of Dataset 1. Because the survey was completed online, the questionnaire was set to mandatory response mode, preventing missing data and eliminating errors from manual data entry. Researchers shared the survey QR code with parents through class WeChat groups, emphasizing that the survey was part of a mental health assessment and asking parents to ensure their children completed it carefully. Based on the applicability of the measurement tools, 28 responses from children under 10 years old were excluded. The final external validation set used for the model included 180 valid responses.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Army Medical Research Institute and adhered to the principles of Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. Written informed consent forms were distributed to parents via class teachers one week prior to the survey. All children and their parents were informed of the study’s purpose and were required to sign the consent form. Participation was voluntary, allowing children to withdraw at any time without consequences. The survey was conducted anonymously, and researchers ensured the confidentiality of all data.

Measure tools

Demographic information included age, gender, grade, residence location, family structure, sibling number, and left-behind child status. RNT was assessed using the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire for Children (PTQ-C; [6]), which evaluates three main factors: (1) core features (CF), encompassing repetitiveness, intrusiveness, and difficulty in disengagement; (2) unproductiveness (UP); and (3) mental capacity (MC). Depression symptoms were measured using the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; [34]), and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Y. [73]). Both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 have demonstrated good psychometric properties in Chinese children and adolescents aged 10 and older [72]. All scales exhibited excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.8). Further details regarding the scales are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Data analysis

Data cleaning and preparation were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed using Mplus version 7.3. Network analysis and machine learning analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.3.

Structural equation modeling

Spearman correlation analyses were conducted between depression, anxiety, and RNT to confirm the prerequisites for SEM. Latent variable SEM was used to examine the predictive role of RNT on depression and anxiety. Additionally, two mediation models were constructed, specifying RNT as the mediator with depression and anxiety as mutual predictors. Models were estimated using robust maximum likelihood (MLR). The evaluation of model fit was conducted according to the established criteria in prior research [8]: χ2/df < 5, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.06.

Network analysis

A Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM) was constructed to conduct network analysis, incorporating nine depression symptoms, seven anxiety symptoms, and three RNT factors. The model employed Spearman’s rho correlation matrix and was regularized with the graphical LASSO algorithm to enhance interpretability and stability [32]. The Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) hyperparameter was set to 0.5 to balance edge selection sensitivity and specificity [25]. Data visualization was performed using the qgraph package [24].

Given the study’s aim to examine the co-occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms (nodes), emphasis was placed on bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence centrality metrics. The network was estimated using the EstimateNetwork function. The computation of bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence was conducted using the networktools package. Bridge betweenness indicates a node’s role in mediating between symptom communities, and bridge expected influence measures a node’s influence as a bridge (connection strength), collectively reflecting the potential for symptom propagation across communities [35, 36]. Network robustness was assessed using the bootnet package (nboot = 2,000), and correlation stability coefficients (CS) was employed to evaluate the stability of bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence [25].

Machine learning

The R package caret was employed for machine learning modeling to identify co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Four algorithms were selected based on their accuracy and computational efficiency in classification tasks: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree (DT), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [9, 11, 13, 64]. The RF algorithm employs an ensemble of decision trees with majority voting, providing robustness and resistance to overfitting [9]. The SVM algorithm performs binary classification by determining an optimal margin, making it suitable for non-linear problems [11]. The DT algorithm constructs a tree structure through recursive data splitting, providing interpretability and low computational complexity [64]. The XGBoost algorithm enhances decision trees via gradient boosting, iteratively correcting residuals to improve prediction accuracy [13]. Detailed settings of the machine learning model parameters can be found in the supplementary materials.

Classification criteria for co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety

The classification criterion for co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety was based on scores from the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales. The initial threshold required total scores ≥ 10 on both scales to identify significant co-occurring symptoms [5, 58]. To facilitate early screening and address data imbalance, a more lenient threshold (scores ≥ 5 on both scales) was used during model training, thereby enhancing sensitivity to potential co-occurring symptoms [79].

Feature selection

To integrate network analysis with machine learning, RNT factors were used as core features, employing a weighting method designed to optimize predictive performance. The weighting process involved: (1) normalizing bridge betweenness (CF = 0.793, UP = 0, MC = 0.207) and bridge expected influence (CF = 0.504, UP = 0.252, MC = 0.244); (2) calculating a weighted average with 50% weight per metric; and (3) normalizing to obtain final weights (CF = 0.649, UP = 0.126, MC = 0.225). Additionally, considering the heterogeneity of depressive and anxiety symptoms [28], demographic variables—gender, age, grade, place of residence (urban/rural) [47, 71, 82], family structure, and left-behind child status—were included to capture their potential influence on symptom co-occurrence [3, 42].

Data preprocessing

Dataset 1 included 1,476 participants after excluding 440 records with missing demographic information to prevent data leakage; no imputation was performed. The dataset was randomly split into 70% training and 30% testing sets, with Dataset 2 used for external validation. To address class imbalance, Random Over-Sampling Examples (ROSE) technique was employed to generate synthetic samples for the minority class, adjusting its proportion set to 40% to improve sensitivity [49]. Two models were trained—one with weighted RNT factors and one with unweighted factors—to validate whether network analysis improved prediction performance.

Model parameter configuration

The RF model was configured with n_estimators = 100 to balance accuracy and computational cost, max_features = sqrt to minimize feature dependency, and bootstrap = True to ensure robustness. SVM used a radial basis function kernel, C = 1.0, class_weight = balanced to address imbalance, and gamma = scale for optimized non-linear mapping. DT employed the Gini criterion (criterion = gini), max_depth = None for maximum classification capacity, and max_leaf_nodes to limit complexity. XGBoost was set with n_estimators = 100, learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 6, subsample = 1.0, colsample_bytree = 1.0, and objective = binary:logistic for binary classification.

Model performance evaluation

Model performance was assessed using accuracy (the proportion of correctly classified samples), precision (the proportion of true co-occurring symptom cases among those predicted), recall (the proportion of true co-occurring symptom cases correctly identified), F1 Score (the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance; [55, 62, 70]). A comparative analysis of performance comparison between weighted and unweighted RNT factor models validated the effectiveness of network analysis optimization, suggesting a potential novel approach for the precise screening of co-occurring symptoms.

Results

Demographic information and descriptive statistics

Dataset 1 (N = 1,916) had a mean participant age of 11.29 years (SD = 0.95, range = 10–15 years) and a balanced gender distribution (50.52% male, N = 968; 49.48% female, N = 890), and 58 did not report gender information. The grade distribution was as follows: Grade 4 (N = 521), Grade 5 (N = 571), and Grade 6 (N = 473), with 351 participants not reporting their grade. The majority of participants resided in urban areas (N = 1,719), while 149 were from rural areas, and 48 did not report their residence. Most participants came from two-parent families (N = 1,542), with 258 from single-parent families, 68 from other family structures, and 48 not reporting family structure. Additionally, 1,619 participants had siblings, 257 were only children, and 40 did not report sibling status. Among the participants, 625 were left-behind children, and 692 exhibited co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales (scores ≥ 5). Dataset 2 (N = 180) consisted of students in Grades 4 to 6, with a mean age of 10.84 years (SD = 1.08) and a balanced gender distribution (male: N = 91; female: N = 89). Of these, 23 participants exhibited co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales (scores ≥ 5). Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Dataset 1 (N = 1916) | Dataset 2 (N = 180) |

|---|---|---|

| n(%) / M(SD) | n(%) / M(SD) | |

| Gender | ||

| Boy | 968 (50.52) | 91 (50.56) |

| Girl | 890 (46.45) | 89 (49.44) |

| Miss | 58 (3.03) | / |

| Age (years) * | 11.29 (0.95) | 10.84 (1.08) |

| Grade | ||

| 4 | 521 (27.19) | 60 (33.33) |

| 5 | 571 (29.80) | 46 (25.56) |

| 6 | 473 (24.69) | 74 (41.11) |

| Miss | 351 (18.32) | / |

| Residents | ||

| Urban | 1734 (90.50) | 163 (90.56) |

| Rural areas | 149 (7.78) | 17 (9.44) |

| Miss | 48 (1.72) | / |

| Family structure | ||

| Two-parent | 1542 (80.48) | 154 (85.55) |

| Single-parent | 258 (13.47) | 20 (11.11) |

| Other | 68 (3.55) | 6 (3.33) |

| Miss | 48 (2.51) | / |

| Number of children | ||

| Multiple-child | 1619 (84.50) | n/a |

| Only children | 257 (13.41) | n/a |

| Miss | 40 (2.09) | n/a |

| Left-behind children * | 625 (32.62) | 29 (16.11) |

| PHQ-9 scores | ||

| ≥ 5 | 1064 (55.53) | 44 (24.44) |

| ≥ 10 | 426 (22.23) | 10 (5.56) |

| ≥ 11 | 343 (17.90) | 9 (5.00) |

| GAD-7 scores | ||

| ≥ 5 | 782 (40.81) | 27 (15.00) |

| ≥ 10 | 270 (14.09) | 6 (3.33) |

| ≥ 11 | 215 (11.22) | 6 (3.33) |

| co-occurrence of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 (scores) | ||

| ≥ 5 | 692 (36.12) | 23 (12.78) |

M mean, SD standard deviation, PHQ-9 patient health questionnaire, GAD-7 generalized anxiety disorder scale

*Mean and standard deviation

Spearman correlation analysis revealed that RNT and its factors were significantly positively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms. The correlation between depressive and anxiety symptoms was the strongest (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), with RNT showing similar correlations with depression (r = 0.66, p < 0.001) and anxiety (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Correlations between RNT factors and depression or anxiety ranged from 0.56 to 0.67 (p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients of each variable

| Variable | Depression | Anxiety | RNT | CF | UP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | - | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.755 | - | |||

| RNT | 0.663 | 0.684 | - | ||

| CF | 0.640 | 0.669 | 0.974 | - | |

| UP | 0.576 | 0.580 | 0.837 | 0.736 | - |

| MC | 0.561 | 0.568 | 0.810 | 0.712 | 0.671 |

All the correlation coefficients have p-values less than 0.001

RNT repetitive negative thinking, CF core features, UP unproductiveness, MC mental capacity

Structural equation modeling

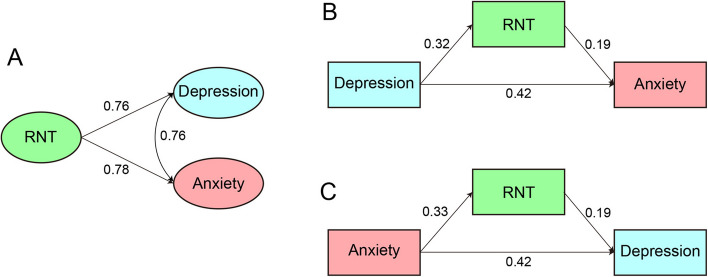

SEM demonstrated good model fit: χ2(149) = 537.12, χ2/df = 3.60, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.036, SRMR = 0.027. Standardized path coefficients revealed that RNT was a significant predictor of depression (β = 0.76, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.78, p < 0.001), suggesting comparable predictive effects for both (Fig. 2A). The path coefficient between depressive and anxiety symptoms was also significant (β = 0.76, p < 0.001). Mediation analysis showed that RNT mediated 12.94% and 12.73% of the total effect in the bidirectional relationship between depression and anxiety (with depression and anxiety as independent variables, respectively), with a same 95% CI: 8.78%–18.43% (p < 0.001; Fig. 2B, C; Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Path coefficients of RNT on depression and anxiety (A); the mediating effect of RNT in the bidirectional relationship between depression and anxiety (B, C)

Table 3.

The bidirectional mediation effect of RNT between depression and anxiety

| Path | Effect | Standard error | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| Depression as an independent variable | ||||

| Depression → Anxiety | 0.417 | 0.023 | 0.371 | 0.462 |

| Depression → RNT → Anxiety | 0.062 | 0.009 | 0.046 | 0.080 |

| Total effect | 0.479 | 0.023 | 0.434 | 0.524 |

| Anxiety as an independent variable | ||||

| Anxiety → Depression | 0.418 | 0.024 | 0.371 | 0.464 |

| Anxiety → RNT → Depression | 0.061 | 0.009 | 0.046 | 0.080 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.479 | 0.023 | 0.434 | 0.524 |

Network analysis

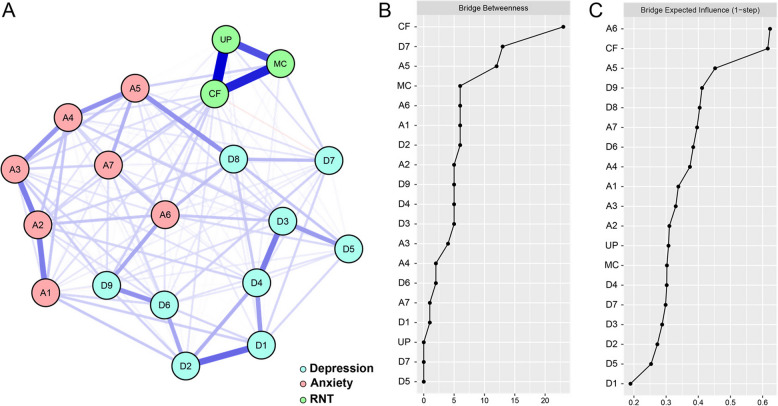

The network exhibited a dense structure (Fig. 3A), with 83.63% of possible edges connected (143/171). Analysis of bridge betweenness identified RNT’s CF (bridge betweenness = 23) as key bridge node, while RNT’s UP and MC showed lower bridge betweenness (0 and 6, respectively; Fig. 3B). Analysis of bridge expected influence indicated that CF (bridge expected influence = 0.616) and irritability (bridge expected influence = 0.623) had the highest influence (Fig. 3C). Bootstrap stability analysis yielded a correlation stability coefficient (CS) of 0.28 for bridge betweenness and 0.75 for both edges and bridge expected influence. These values exceed recommended threshold of 0.25 [23], indicating a robust network structure.

Fig. 3.

Network structure (A), bridge betweenness (B) and bridge expected influence (C)

Machine learning

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the performance of weighted and unweighted RNT factor models. Internal validation showed that the AUC for weighted models (0.799–0.827) was similar to that of unweighted models (0.804–0.830). However, weighted models significantly outperformed unweighted models in recall (0.738–0.806 vs. 0.612–0.719), indicating a better identification of children with co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety (highest Recall = 80.6% vs. 71.9%). Precision values were similar between weighted (0.638–0.697) and unweighted models (0.676–0.715), suggesting a moderate false-positive rate. External validation showed similar trends (Table 4).

Table 4.

Performance comparison of weighted and unweighted feature models in internal and external validation

| Model Index | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Weighted/Unweighted | Weighted/Unweighted | |

| AUC | ||

| SVM | 0.799/0.817 | 0.850/0.868 |

| RF | 0.827/0.830 | 0.900/0.887 |

| XGBoost | 0.810/0.829 | 0.863/0.892 |

| DT | 0.801/0.804 | 0.884/0.863 |

| Accuracy | ||

| SVM | 0.760/0.783 | 0.756/0.806 |

| RF | 0.796/0.771 | 0.744/0.861 |

| XGBoost | 0.790/0.767 | 0.739/0.800 |

| DT | 0.753/0.774 | 0.806/0.811 |

| Precision | ||

| SVM | 0.645/0.698 | 0.333/0.380 |

| RF | 0.697/0.715 | 0.328/0.476 |

| XGBoost | 0.675/0.689 | 0.324/0.377 |

| DT | 0.638/0.676 | 0.389/0.392 |

| Recall | ||

| SVM | 0.750/0.706 | 0.913/0.826 |

| RF | 0.775/0.612 | 0.957/0.870 |

| XGBoost | 0.806/0.650 | 0.957/0.870 |

| DT | 0.738/0.719 | 0.913/0.870 |

| F1 Score | ||

| SVM | 0.694/0.702 | 0.488/0.521 |

| RF | 0.734/0.660 | 0.489/0.615 |

| XGBoost | 0.735/0.669 | 0.484/0.526 |

| DT | 0.684/0.697 | 0.545/0.541 |

Weighted represents the feature model weighted by the network analysis results; unweighted represents the feature model without weighting

AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, SVM support vector machine, RF random forest, DT decision tree, XGboost eXtreme gradient boosting

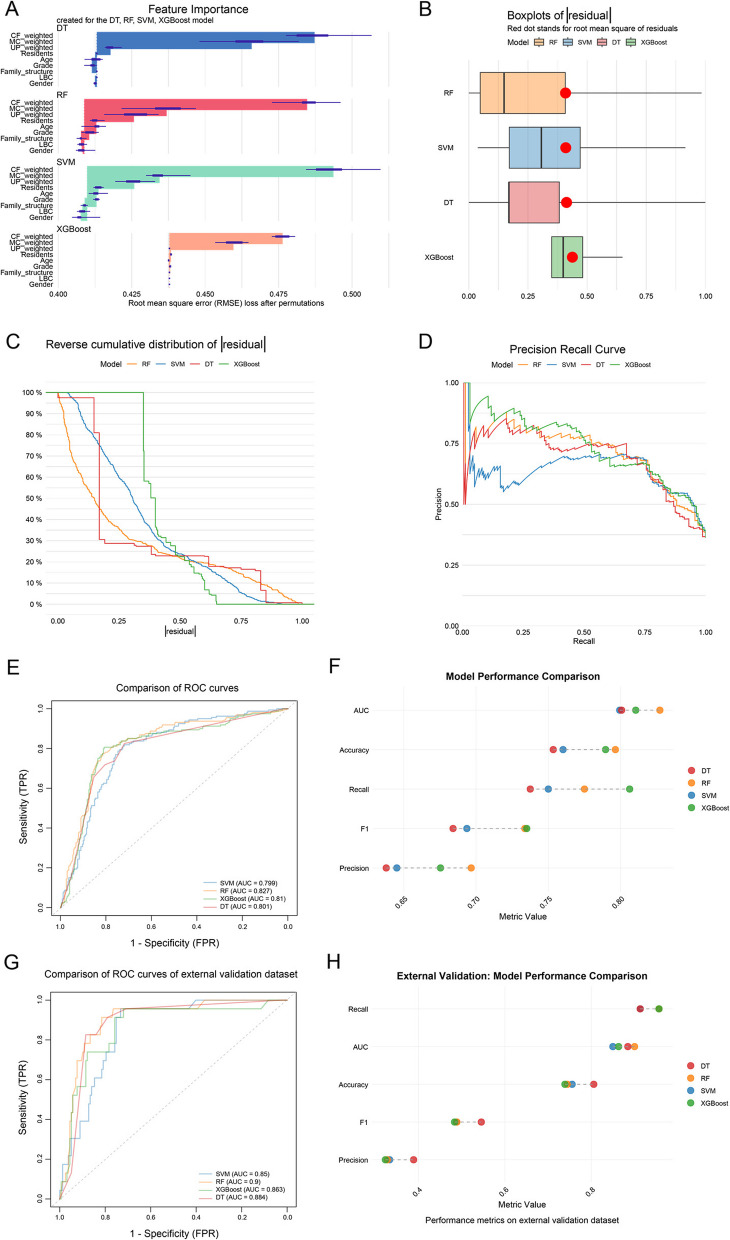

Based on the weighted model performance, only the results from the weighted model results are presented. The analysis of feature importance analysis identified CF as the most important feature, followed by MC, with UP being the least important (Fig. 4A). This finding is consistent with that from the unweighted models, indicating that weighting did not alter feature rankings. RF exhibited the lowest median absolute residuals (Fig. 4B) and a balanced residual distribution (Fig. 4C), with the best overall performance (AUC = 0.827, recall = 0.806, precision = 0.697; Fig. 4D, E, F). XGBoost ranked second in performance (AUC = 0.810), outperforming SVM and DT. External validation confirmed RF as the optimal model (Fig. 4G, H), with recall = 0.957 and precision = 0.328, highlighting its potential in the early screening of co-occurring symptoms. Overall, these findings suggest that the integration of weighted RNT factors with network analysis enhances predictive performance.

Fig. 4.

The performance of machine learning models. The feature importance (A); root mean square of residuals (B); inverse cumulative distribution of absolute residuals (C); precision and recall curve (D); comparison of ROC curves (E); model performance comparison (F); comparison of ROC curves of external validation dataset (G); model performance comparison of external validation dataset (H). Note: RNT, repetitive negative thinking; SVM, support vector machine; RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; XGboost, eXtreme gradient boosting; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; CF, core features; UP, unproductiveness; MC, mental capacity

Discussion

The rising trend of co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety among children and adolescents underscores the urgent need for early screening, particularly in regions with limited medical resources [39, 43, 61] [43, 61]. RNT, as a transdiagnostic factor may play a critical role in understanding and predicting co-occurring symptoms [67, 81]. This study employed correlation analysis, SEM, network analysis, and machine learning to validate the role of RNT in the co-occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and to explore the effectiveness of network analysis-guided weighted feature models for early screening. These findings provide multi-method support for the transdiagnostic mechanisms of RNT and offer novel strategies for screening co-occurring symptoms in resource-limited settings, such as schools.

RNT as a transdiagnostic predictor at the variable level

Spearman correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations between RNT and its factors (CF, UP, MC) and symptoms of depression and anxiety. SEM confirmed the robust predictive role of RNT, mediating approximately 13% of the bidirectional relationship between these symptoms. Despite its moderate magnitude, this effect is clinically significant, particularly among high-risk groups such as left-behind children [38]. These findings support Hypothesis 1 and align with the tripartite model, which posits that RNT amplifies shared negative affectivity underlying depression and anxiety [15], as well as Beck’s cognitive triad theory, which suggests that RNT reinforces negative cognitive schemas [2]. The results corroborate previous research demonstrating RNT as a transdiagnostic process (i.e., a cognitive mechanism transcending single disorders), remains stable across different scales (e.g., Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales) and longitudinal data [53, 68]. This suggests that RNT not only serves as a shared risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms but may also sustain their co-occurrence by intensifying negative emotions.

RNT factors as a transdiagnostic critical factor at the symptom level

Network analysis further revealed heterogeneity in the role of RNT factors within the symptom co-occurrence network. CF exhibited the highest bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence, indicating its critical role in connecting depressive and anxiety symptom communities, supporting Hypothesis 2. The intrusive and difficult-to-disengage characteristics of CF closely resemble rumination in depression and worry in anxiety [20, 21], potentially driving symptom propagation by reinforcing cycles of negative thinking, consistent with the cognitive triad theory [2]. In contrast, UP and MC showed lower levels of bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence, suggesting limited contributions to transdiagnostic processes [22]. Given their strong associations with CF, UP and MC may primarily influence the development and persistence of depressive and anxiety symptoms via CF. This finding has implications for intervention design, suggesting that cognitive behavioral therapies targeting CF, such as mindfulness-based interventions, may effectively alleviate co-occurring symptoms [4].

Predictive performance of RNT in early screening

The machine learning findings supported Hypothesis 3, demonstrating that weighted RNT factor models outperformed unweighted models in predicting co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety. The RF model exhibited the best performance in internal validation, identifying 80.6% of children with co-occurring symptoms, with external validation supporting its robustness. The high recall of weighted models indicates greater sensitivity compared to traditional scale-based methods (e.g., single PHQ-9 or GAD-7 thresholds), making them suitable for resource-limited school settings. However, the lower precision of the weighted models suggests a higher false-positive rate (approximately 30% for internal validation and 67% for external validation), necessitating subsequent clinical assessments. Meanwhile, the high false-positive rate resulting from the inherent class imbalance in clinical data [44] may lead to increased downstream costs, heightened parental worry, and the potential stigmatization of children [33]. These outcomes reflect a typical trade-off faced by machine learning models in clinical applications [41]. In the current model setup, emphasis was placed on high recall rates to ensure identification of at-risk children [66]. Notably, network analysis-guided feature weighting enhanced model performance, indicating that bridge betweenness and bridge expected influence can optimize feature selection in machine learning, offering a novel approach for predicting symptom co-occurrence.

This study has several limitations. First, it relied on self-reported data from PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales, which are designed for preliminary screening rather than clinical diagnosis, and may be susceptible to biases such as by social desirability or cognitive limitations in children. Future research should consider incorporating objective behavioral measures (e.g., observational or physiological indicators) to enhance the accuracy. Second, although data imbalance was addressed using the ROSE method, it may still affect the model generalizability. Third, the sample primarily consisted of Chinese primary school students in Grades 4 to 6, which restricts generalizability to other age groups or cultural contexts (e.g., coastal vs. inland settings). Fourth, the predictive performance of machine learning models requires further validation in real-world screening scenarios to assess their clinical utility. Finally, while demographic variables (e.g., left-behind child status, family structure) were included in the models, their interactions with RNT were not thoroughly explored. Future studies could investigate the potential moderating effects of these interactions.

Conclusion

This study employed multiple methods to validate the transdiagnostic role of RNT in the co-occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children at both variable and symptom levels. Correlation analysis and SEM demonstrated that RNT, particularly CF, was significantly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, contributing to their co-occurrence with a mediation effect of 12.94%. Network analysis revealed CF’s high bridge betweenness, highlighting its pivotal role in symptom propagation. Moreover, the findings of machine learning further showed that network analysis-guided weighted RNT models exhibited excellent performance in early screening during external validation, effectively identifying children with co-occurring symptoms and proving to be suitable for resource-limited school settings. These findings enhance the theoretical understanding of RNT’s transdiagnostic mechanisms and provide a foundation for interventions targeting CF, such as mindfulness-based therapies. Future research should focus on improving model precision, validating the efficacy of interventions, and exploring interactions between RNT and demographic factors to enhance the precision of screening and prevention of symptom co-occurrence.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- RNT

Repetitive negative thinking

- RF

Random forest

- SVM

Support vector machine

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- XGBoost

eXtreme gradient boosting

- DT

Decision tree

- CV

Cross-validation

- CF

Core features

- UP

Unproductiveness

- MC

Mental capacity

- CI

Confidence interval

- CS

Correlation stability

- GGM

Gaussian graphical model

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- EBIC

Extended Bayesian information criterion

- GFI

Goodness of fit index

- NFI

Normed fit index

- CFI

Comparative fit index

- IFI

Incremental fit index

- RMSEA

Root mean square error of approximation

- PHQ-9

Patient health questionnaire

- GAD-7

Generalized anxiety disorder scale

Authors’ contributions

K.L. and L.R. wrote the main manuscript text. K.L. and C.L. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. X.L., X.T., and C.L. collected the data. M.J. and X.L. designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fund for the Major Project of the Shaanxi Provincial Teacher Development Research Program (Grant No. SJS2022ZZ008).

Data availability

The data and code required for this study are available on the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/Eq. 74/?view_only = 9b7f553a37bf4ec3b15d1a69ee1475ed.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Army Medical University. The present study complies with the requirements of the Helsinki Declaration for studies involving human beings. One week prior to the survey, both children and their parents were informed of the purpose of the survey and asked to sign an informed consent form. The researchers ensured the confidentiality and privacy of the data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Article corrected in 2025.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/25/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s40359-025-03451-z

Contributor Information

Ming Ji, Email: jiming@snnu.edu.cn.

Xi Luo, Email: luorosi@126.com.

References

- 1.Bai B, Yin H, Guo L, Ma H, Wang H, Liu F, Liang Y, et al. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety leads to a poor prognosis following angina pectoris patients: a prospective study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press. 1976.

- 3.Behere AP, Basnet P, Campbell P. Effects of family structure on mental health of children: a preliminary study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(4):457–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell IH, Marx W, Nguyen K, Grace S, Gleeson J, Alvarez-Jimenez M. The effect of psychological treatment on repetitive negative thinking in youth depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2023;53(1):6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt KN, Kalogeropoulos AP, Dunbar SB, Butler J, Georgiopoulou VV. Depression in heart failure: can PHQ-9 help? Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bijttebier P, Raes F, Vasey MW, Bastin M, Ehring TW. Assessment of repetitive negative thinking in children: the perseverative thinking questionnaire – child version (PTQ-C). J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2015;37(1):164–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(1):91–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman ND, Goodboy AK. Evolving considerations and empirical approaches to construct validity in communication science. Annals of the International Communication Association. 2020;44(3):219–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodar KE, La Greca AM, Hysing M, Llabre MM. Stressors, repetitive negative thinking, and insomnia symptoms in adolescents beginning high school. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(9):1027–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan VK, Dahiya K, Sharma A. Problem formulations and solvers in linear SVM: a review. Artif Intell Rev. 2019;52(2):803–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J. Study on the association between 24-hour movement behavior and depression, anxiety and depressive-anxiety comorbid symptoms in adolescents (Master of Medicine). Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, GuangZhou. 2022.

- 13.Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 785–794). New York, NY, USA: ACM. 2016.

- 14.Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H, Lokhnygina Y. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research, Third Edition. 3rd ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(3):316–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ. 2015;350: g7594. 10.1136/bmj.g7594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HLJ, Borsboom D. Comorbidity: a network perspective. Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33(2–3):137–50 (discussion 150-93). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings CM, Caporino NE, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(3):816–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devynck F, Kornacka M, Baeyens C, Serra É, Neves JF. das, Gaudrat, B., Delille, C., et al. (2017). Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): French Validation of a Transdiagnostic Measure of Repetitive Negative Thinking. Front Psychol. 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ehring T. Thinking too much: rumination and psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):441–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehring T, Watkins ER. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. Int J Cogn Ther. 2008;1(3):192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehring T, Zetsche U, Weidacker K, Wahl K, Schönfeld S, Ehlers A. The perseverative thinking questionnaire (PTQ): validation of a content-independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42(2):225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(1):195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. Qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epskamp S, Fried EI. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods. 2018;23(4):617–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng R, Li K, Li Z, Feng Z. Development and application of negative cognitive processing bias scale for adolescents. J Army Med Univ. 2024;46(02):196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonagy P, Pugh K. Editorial: CAMHS goes mainstream. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2017;22(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao Y-Q, Pan B-C, Sun W, Wu H, Wang J-N, Wang L. Depressive symptoms among Chinese nurses: prevalence and the associated factors. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(5):1166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garber J, Weersing VR. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: implications for treatment and prevention. Clin Psychol. 2010;17(4):293–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorman JM. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4(4):160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han S-H, Kim KW, Kim S, Youn YC. Artificial neural network: understanding the basic concepts without mathematics. Dementia Neurocogn Disord. 2018;17(3):83–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haslbeck JMB, Fried EI. How predictable are symptoms in psychopathological networks? A reanalysis of 18 published datasets. Psychol Med. 2017;47(16):2267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horsselenberg EMA, van Busschbach JT, Aleman A, Pijnenborg GHM. Self-stigma and its relationship with victimization, psychotic symptoms and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0149763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu X, Zhang Y, Liang W, Zhang H, Yang S. Reliability test of the patient health questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9) in adolescents. Sichuan Mental Health. 2014;27(04):357–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones, P. (2017). networktools: Assorted Tools for Identifying Important Nodes in Networks. R package version 1.0.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=networktools.

- 36.Jones P, Ma R, McNally RJ. Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2021;56(2), 353–367. Routledge. Retrieved from 10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Kaiser T, Herzog P, Voderholzer U, Brakemeier E. Unraveling the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in a large inpatient sample: network analysis to examine bridge symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(3):307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3(1):1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KM, Lee DH, Lee EJ, Roh YH, Kim W-J, Cho S-J, Yang KI, et al. Self-reported insomnia as a marker for anxiety and depression among migraineurs: a population-based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:111–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar V, Biswas S, Rajput DS, Patel H, Tiwari B. PCA-Based Incremental Extreme Learning Machine (PCA-IELM) for COVID-19 Patient Diagnosis Using Chest X-Ray Images. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li K, Guang Y, Ren L, Zhan X, Tan X, Luo X, Feng Z. Network analysis of the relationship between negative life events and depressive symptoms in the left-behind children. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YI, Starr LR, Wray-Lake L. Insomnia mediates the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(6):583–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livermore D, Trappenberg T, Syme A. Machine learning for contour classification in TG-263 noncompliant databases. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022;23(9): e13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Long J, Ouyang Y, Duan H, Xiang Z, Ma H, Ju M, Sun D. multiple factor analysis of depression and/or anxiety in patients with acute exacerbation chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1449–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lotrakul M, Saipanish R. Psychiatric services in primary care settings: a survey of general practitioners in Thailand. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:48. 10.1186/1471-2296-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu J, Jiang M, Li L, Hesketh T. Relaxation in the Chinese Hukou system: effects on psychosocial wellbeing of children affected by migration. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19): 3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lueken U, Straube B, Yang Y, Hahn T, Beesdo-Baum K, Wittchen H-U, Konrad C, et al. Separating depressive comorbidity from panic disorder: a combined functional magnetic resonance imaging and machine learning approach. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:182–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lunardon N, Menardi G, Torelli N. ROSE: a package for binary imbalanced learning. R J. 2014;6(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo J, Bei D-L, Zheng C, Jin J, Yao C, Zhao J, Gong J. The comorbid network characteristics of anxiety and depressive symptoms among Chinese college freshmen. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magklara K, Bellos S, Niakas D, Stylianidis S, Kolaitis G, Mavreas V, Skapinakis P. Depression in late adolescence: a cross-sectional study in senior high schools in Greece. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malygin YV, Orlova AS, Malygin VL. Conceptualization of comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders and approaches to their managing. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2022;122(6):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McEvoy PM, Salmon K, Hyett MP, Jose PE, Gutenbrunner C, Bryson K, Dewhirst M. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic predictor of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Assessment. 2019;26(2):324–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McNally RJ, Mair P, Mugno BL, Riemann BC. Co-morbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: a Bayesian network approach. Psychol Med. 2017;47(7):1204–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mei J, Desrosiers C, Frasnelli J. Machine learning for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease: a review of literature. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13: 633752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melton TH, Croarkin PE, Strawn JR, McClintock SM. Comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a systematic review and analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2016;22(2):84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49(1):377–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrison C, Walker G, Ruggeri K, Hacker Hughes J. An implementation pilot of the MindBalance web-based intervention for depression in three IAPT services. Cogn Behav Ther. 2014;7: e15. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moulds ML, Black MJ, Newby JM, Hirsch CR. Repetitive negative thinking and its role in perinatal mental health. Psychopathology. 2018;51(3):161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patterson P, McDonald FEJ, Kelly-Dalgety E, Lavorgna B, Jones BL, Sidis AE, Powell T. Development and evaluation of the good grief program for young people bereaved by familial cancer. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sandler RA, Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Song D, Berger TW, Marmarelis VZ. System identification of point-process neural systems using probability based Volterra kernels. J Neurosci Methods. 2015;240:179–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schniering CA, Einstein D, Kirkman JJL, Rapee RM. Online treatment of adolescents with comorbid anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2022;311:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaikhina T, Lowe D, Daga S, Briggs D, Higgins R, Khovanova N. Decision tree and random forest models for outcome prediction in antibody incompatible kidney transplantation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2019;52:456–62. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shihata S, Johnson AR, Erceg-Hurn DM, McEvoy PM. Measurement invariance of disorder-specific and transdiagnostic measures of repetitive negative thinking. Assessment. 2022;29(8):1730–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sigdel M, Dinc I, Sigdel MS, Dinc S, Pusey ML, Aygun RS. Feature analysis for classification of trace fluorescent labeled protein crystallization images. BioData Min. 2017;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spinhoven P, Drost J, van Hemert B, Penninx BW. Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;33:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spinhoven P, van Hemert AM, Penninx BW. Repetitive negative thinking as a predictor of depression and anxiety: a longitudinal cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:216–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Su W, Luo L, Yan N, Zhang Y, Jiang G, Yuan G. Investigation and analysis of the influencing factors on anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents in Chongqing city through Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7). J Psychiatry. 2022;35(02):158–62. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tharwat A. Classification assessment methods. Appl Comput Inform. 2021;17(1):168–92. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Unsal A, Unaldi C, Baytemir C. Anxiety and depression levels of inpatients in the city centre of Kirşehir in Turkey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(4):411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang S. The optimal cut-offs of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in the initial screening of depression and anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents with different characteristics. Kunming: Kunming Medical University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y, Chen R, Zhang L. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale among inpatients in general hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;28(3):168–71. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(2):163–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104(1):3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wei Y, Cui B, Xue J, Chen S, Huang Z. Application analysis of the 9-item patient health questionnaire in adolescents. Sichuan Mental Health. 2023;36(02):149–55. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Z, Fang Y. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders: challenges in diagnosis and assessment. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26(4):227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamada K, Hosoda M, Nakashima S, Furuta K, Awata S. Psychiatric diagnosis in the elderly referred to a consultation-liaison psychiatry service in a general geriatric hospital in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(2):304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang X, Gao L, Zhang S, Zhang L, Zhang L, Zhou S, Qi M, et al. The professional identity and career attitude of Chinese medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in China. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13: 774467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zagaria A, Ballesio A, Vacca M, Lombardo C. Repetitive negative thinking as a central node between psychopathological domains: a network analysis. Int J Cogn Ther. 2023;16(2):143–60. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zetsche U, Bürkner P-C, Schulze L. Shedding light on the association between repetitive negative thinking and deficits in cognitive control - a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Y, Li S, Xu H, Jin Z, Li R, Zhang Y, Wan Y. Gender-based differences in interaction effects between childhood maltreatment and problematic mobile phone use on college students’ depression and anxiety symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang-James Y, Chen Q, Kuja-Halkola R, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Faraone SV. Machine-learning prediction of comorbid substance use disorders in ADHD youth using Swedish registry data. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61(12):1370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou S-J, Zhang L-G, Wang L-L, Guo Z-C, Wang J-Q, Chen J-C, Liu M, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu Z, Li P, Hao L. Correlation of childhood psychological abuse and neglect with mental health in Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 770201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and code required for this study are available on the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/Eq. 74/?view_only = 9b7f553a37bf4ec3b15d1a69ee1475ed.