Abstract

Self-induced ear care is considered a bad practice and is associated with several complications. Usually, it consists of activities and habits that an individual adopts with the view of self-treating and maintaining the cleanliness of the ears. Most patients in Ghana who report to the hospital with ear conditions often mention self-initiated ear care at home prior to their hospital visit. It is a worry due to the impact on an individual’s hearing and overall quality of life. This study, therefore, aimed to explore and describe the self-induced ear care experiences among patients who access services at an Ear, Nose and Throat Clinic in Ghana. The study used an exploratory descriptive qualitative design among patients who have been practising self-induced ear care and patients who have experienced or are experiencing complications from self-induced ear care. Upon the consent of participants, interviews were conducted and audio-recorded. Data was analysed using thematic analysis. The study findings revealed that when participants encountered an ear problem, they preferred engaging in self-induced ear care based on their intentions, beliefs and evaluation of the consequences of their actions. They were poking the ears with their fingers, using safety/hair pins, chicken features, broomsticks, herbs, Dr. Côte d’Ivoire ointment, and cotton wool rather than reporting to the hospital. However, they became reoriented, dissociating themselves from self-induced ear care after encountering complications associated with it and gaining insight into the cause of their condition. In conclusion, stakeholders should sensitise the public to the dangers of self-induced ear care and develop educational strategies to address the knowledge gap and promote positive health-seeking behaviour towards all ear problems.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23991-8.

Keywords: Attitude, Ear complications, Ear, Nose & throat, Ghana, Intentions, Self-induced ear care, Subjective norms

Introduction

The human ear is a sensory organ that provides the functions of hearing and balance, making it one of the most important organs in sustaining a healthy existence. The ear is not simply a component of the hearing system; it also plays a crucial role in preserving the body’s equilibrium, which is necessary for a person to carry out their everyday tasks [1]. Physiologically, the human ear has an auto-cleaning mechanism facilitated by the movement of the jaw while speaking, chewing, and yawning, which naturally pushes out earwax and other particles without any external effort, known as a conveyor belt. The ideal is for individuals to desist from Self-Induced Ear Care (SIEC) due to interference with the natural cleaning process. This is because SIEC potentially rids the ear of its protective defences, leading to ear trauma and problems [2, 3].

Notwithstanding the physiological functions of the ear, problems may occur naturally or through the actions of individuals. Self-Induced Ear Care is an act initiated by the individual where treatment was not ascertained from the hospital. The self-initiated action occurs widely in reaction to a tingling sensation or discomfort in the ear canal. The practice may cause harm to the ear and jeopardise its integrity as a natural auto-cleaning mechanism [4], causing diverse ear problems. Ear diseases and injuries are a significant public health problem, especially in developing regions with high prevalence [5–7], where they are often neglected. The burden of ear disease and hearing loss is substantial, with an estimated 20.1 million cases of hearing loss due to otitis media and more cases of chronic suppurative otitis media [8]. It is projected that 630 million people will be living with hearing loss by 2030 [9]. The number will escalate to 2.5 billion by 2050 [10], which is alarming and costly for any nation. In 2020, almost 1 trillion dollars was spent on unaddressed hearing loss globally [11]. These disturbing figures demand attention and strategies to curb the situation. Chadha et al. have suggested the need for countries to align with cost-effective interventions and strategies that benefit the population across all stages of life span [12]. The root causes of hearing loss should be identified to understand the issues for appropriate solutions. SIEC is a possible root cause of ear loss.

Self-Induced Ear Care cleaning is identified as a long-standing, global activity that transcends gender and age [13]. It is defined as the act of inserting things into the ear canal to clean and remove foreign bodies, as well as instilling unprescribed medicine into the ears [14, 15]. Evidence attests to the fact that most people practice SIEC to remove dirt [16, 17]. This is because earwax is usually misconstrued as dirt. Physiologically, it’s untrue as earwax is a normal and healthy substance that helps protect the ear canal from dust, dirt, and other foreign particles. The wax further moistens the ear canal, prevents infections, and protects against bacteria and fungi [18, 19]. However, excessive accumulation can lead to cerumen impaction, which may obstruct clinical assessment, cause conductive hearing loss, induce discomfort or vertigo if in contact with the tympanic membrane, and contribute to infections [20]. Therefore, concerns about excessive earwax or blockage must be reported to the hospital for appropriate guidance and treatment, but this is usually not the case. Other reasons attributed to the act of SIEC are ensuring aural hygiene and relief of any uncomfortable ear sensation, possibly from the presence of ear itchiness and difficulty hearing [2, 21]. Inappropriate self-induced cleaning of the ears can result in cerumen impaction, otitis externa, and damage [22, 23].

The ear is a hub for diverse tools when individuals indulge in SIEC. Evidence reports on the use of cotton buds, pen tops, feathers, matchsticks, pins, toothpicks, car keys, ear candles, Q-tips and sharp objects for self-induced ear cleaning [4, 15, 22, 24]. This can lead to bruising and bleeding. Among the tools mentioned, the most frequently utilised is cotton wool [13, 25]. Khan et al. further reported that individuals often clean their ears daily to once a week, focusing on the outer or inside of either one or both ears [15]. This attitude may be influenced by societal norms and beliefs about cleanliness and hygiene, where earwax is considered as dirt and harmful [17] or from just the desire. For instance, it is a common belief that using cotton buds or other objects for ear cleaning is a normal and acceptable practice [26]. These beliefs end up in practices that may impact the daily lives of individuals and result in complications. Another concern is self-initiating ear medication without a prescription. Evidence suggests that this increases the resistance of pathogens and generally leads to serious health hazards such as adverse drug reactions, prolonged suffering, and dependence [27]. In addition, medications, when misused, can hide the onset of illnesses and create a host of other problems [25].

In Africa, SIEC has been attributed to a lack of knowledge and unawareness of the consequences [2, 28]. The authors further revealed that most of the studies were quantitative, leaving out the nuances and storyline embedded in the options of a questionnaire. Among some African settings, such as Nigeria and South Africa, SIEC seems similar, focusing on diverse items for ear cleaning, clinical presentations and gender distribution, where more females than men indulge in the practice [15, 16]. Additionally, despite the dire consequences of SIEC, most young adults in Africa engage in this practice [26], possibly based on desires unknown. In Ghana, anecdotal evidence gathered from an ENT clinic in one of the hospitals revealed that most patients with ear problems engage in SIEC before reporting to the hospital. There may be several people who do not report to the hospital and resort to other means, which may negatively impact their health. Most studies on ear health in Ghana focused on hearing difficulties/impairment and accessibility of ear care in the communities [29–31], with little known about the experiences of those who engaged in SIEC, especially the contextual factors leading to the practice. Therefore, this study sought to explore and describe patients’ experiences of SIEC and understand the factors leading to such practices. This would inform stakeholders to develop appropriate strategies to reduce possible ear injuries and complications. The study employed a qualitative approach because little is documented in the literature in the Ghanaian context. Also, qualitative is a flexible approach that helps to unravel hidden trends while exploring the complexities of a phenomenon.

Methods

Theoretical framework

The study utilised the Theory of Reasoned Action [TRA] [32] to explore the phenomenon. The theory helps to understand behaviour with an emphasis on the intention, attitudes and subjective norms. The premise is that any behaviour that occurs depends on the behavioural intentions. These intentions are influenced by the attitude towards the behaviour and beliefs associated with the behaviour. TRA helped to understand the SIEC behaviour and its root issues. In this study, the theory was utilised as a guiding framework and aided in the analysis of the findings. The researchers labelled actions that depicted the constructs of the theory based on participants’ narrations/perspectives.

Research design

The study employed an exploratory descriptive qualitative approach to explore and describe patients’ SEC experiences [33]. This approach is well-suited due to its flexibility and openness to explore perspectives on the topic. It offered the researchers the opportunity to uncover and gain an in-depth understanding of patients’ experiences through questioning and capitalising on their responses: why they engaged in SIEC, what is involved in the process, who contributes to such practices and when it occurs.

Setting and population

The study was conducted in an ENT clinic at one of the Regional Hospitals in Ghana. The ENT clinic provides ear, nose and throat care to the entire population in its environs. The study included all patients who reported to the clinic and had engaged in SIEC prior to seeking medical treatment and those who had complications as a result of such practices. This was because they had experienced the phenomenon of interest and were in a better position to provide insight into their behaviour. Patients who have suffered complications were identified through self-reporting and probing about their reasons for seeking care. All patients who were interested in the study and voluntarily consented to the study were recruited. Participants with speech impairment and ear problems not associated with SIEC were excluded from the study. In this study, SIEC refers to the act of an individual introducing anything into the ear for cleaning and reducing/relieving discomfort without receiving medical attention or directives from the hospital.

Sampling technique and sample size

Fifteen participants were recruited purposively, looking for patients who had experienced SEC to understand the phenomenon and answer the research purpose. To ensure transparency of the sampling approach utilised, the researchers developed a criterion that informed the selection of participants. Thus, participants who reported to the ENT clinic should have engaged in SIEC or experienced a complication associated with SIEC at the time of data collection. Based on the inclusion criteria, potential participants interested in sharing their experiences were recruited, and interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide. Interviews were scheduled based on the availability of participants and agreed-upon time. The principle of data saturation guided the sample size of 15. The researchers stopped conducting more interviews when no new information was identified [34], and behaviours that aligned with the theory were determined based on the participants’ narrations.

Data collection procedure

Data collection commenced after ethical clearance was obtained and consent was granted from the participants who met the inclusion criteria. Prior to an interview, the participant is provided with an information sheet to read and understand the scope of the study. For those who could not read, the researcher explained the scope to them. They were allowed to ask questions for clarification. The participants were informed about their right to participate or withdraw from the study without coercion. Each participant signed a consent form after it was confirmed that they had understood the scope of the study. All fifteen interviews were conducted face-to-face and audio-recorded, lasting between 35 and 50 min. The interviews were audio recorded with the consent of the participants. The recruitment of participants was initiated after they had received the necessary services at the clinic to prevent the notions of sub-standard care or withdrawal of care if participants refused to be part of the study. An interview guide was developed based on the constructs of TRA. The interview guide was pre-tested at a different hospital to ensure clarity and that it elicits the appropriate responses. During the interview, some of the questions discussed were: (1) Kindly share with me your experience with SEC practices. (2) How did you engage in SEC practices? (3) In your opinion, what motivated you to engage in SEC practices? Probes were elicited based on the responses of participants to understand their experiences better. Researcher JAD recruited and conducted all interviews at the homes of patients or in an empty consulting room at the clinic. Data collection and analysis occurred within 4 months.

Data analysis

The researchers manually transcribed the audio-recorded tapes after labelling them with pseudonyms. First, all transcripts were assessed for accuracy by researchers VAA and JAD, who listened to the audio-recorded interviews and read through the transcripts line by line. This ensured that missing information was inserted, enhancing the reliability of the data. A deductive analysis approach was adopted with the TRA to understand participants’ behaviour. Thematic analysis was employed [35]. We read through the transcripts several times to become acquainted with the data and generated preliminary codes that aligned with the theory’s construct. Specifically, codes were applied to the data by looking for actions that depicted SEC practices. During the initial phase of the coding, researchers JAD and VAA independently coded the data and agreed on the coding frame through discussion. The coding was deductive, where the researchers labelled behaviours that aligned with the constructs of TRA based on participants’ descriptions. Similar codes within transcripts and between transcripts were grouped to identify similar patterns, which helped in deducing subthemes that aligned with the constructs of TRA, which were the overarching themes. The sub-themes and themes were reviewed by JAD and VAA and refined where appropriate. A report on the findings was then generated from the storyline of the sub-themes and themes projected by the data.

Rigour

Trustworthiness was ensured through credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [36]. Strategies employed to ensure these principles were prolonged engagement, where participants were offered enough time to share their experience and verifying data accuracy with participants through member checking. This provided the opportunity for participants to agree or disagree with the interpretations of the study. Also, we kept an audit trail and conducted peer debriefing sessions. Lastly, we provided a detailed description of the study setting and participant characteristics.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki by subjecting a proposal for ethics scrutiny to ensure its appropriateness in terms of principles governing research which was followed throughout the study. Ethical clearance was sought from the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (GHS-ERC 045/03/23). With the clearance certificate and an introductory letter, the researcher sought permission from gatekeepers. Recruitment commenced when access was provided. Informed consent was obtained from all participants who were involved in the study. Thus, all participants involved in the study were informed about the scope, risks and benefits of the study. Also, participants were allowed enough time to seek clarification before they signed the consent form. Privacy and confidentiality were assured with the use of pseudonyms during the interviews. Also, the findings report was de-identified as group data.

Findings

Participants characteristics

Fifteen [15] participants, aged 18–35, were involved in the study. The majority were Christians and married, with eight [8] females and seven [7] males. All participants had some form of formal education, ranging from Junior High School to the tertiary level and were engaged in various occupations, both formal and informal, while others were students. All participants were Akans. Participants in this study are identified with pseudonyms. Details of participants’ characteristics are as follows:

| Pseudonyms | Age | Gender | Marital status | Educational level | Occupation | Religion | Place of residence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adwoa | 30–35 | Female | Cohabitation | Tertiary | Teacher | Christianity | Takoradi |

| Rich | 30–35 | Male | Married | Tertiary | Teacher | Christianity | Diabene |

| Nhyira | 18–23 | Male | Single | Secondary | Student | Christianity | Fijai |

| Nana | 24–29 | Female | Single | Tertiary | Student | Christianity | Anaji |

| Kwesi | 30–35 | Male | Married | Tertiary | Lab Technician | Christianity |

Airport Ridge |

| Kojo | 30–35 | Male | Married | JHS | Operator | Christianity | Anaji |

| Kofi | 30–35 | Male | Married | Secondary | Driver | Islamic | Kweikuma |

| Fred | 30–35 | Male | Married | Secondary | Lotto Agent | Christianity | Sekondi |

| Kofi | 30–35 | Male | Married | JHS | Petty Trader | Christianity | Shama |

| Akua | 30–35 | Female | Divorce | Tertiary | Teacher | Christianity | Takoradi |

| Efua | 18–23 | Female | Cohabitation | Tertiary | Student | Christianity | Anaji |

| Celestine | 30–35 | Female | Married | JHS | Business woman | Christianity | Mpintsin |

| Ama | 18–23 | Female | Married | Secondary | Seamstress | Islamic | Effiakuma |

| Alima | 30–35 | Female | Married | Secondary | Nurse | Islamic | Kojokrom |

| Cecelia | 30–35 | Female | Single | Secondary | Businesswoman | Christianity | Fijai |

Key

JHS Junior High School

Themes and sub-themes

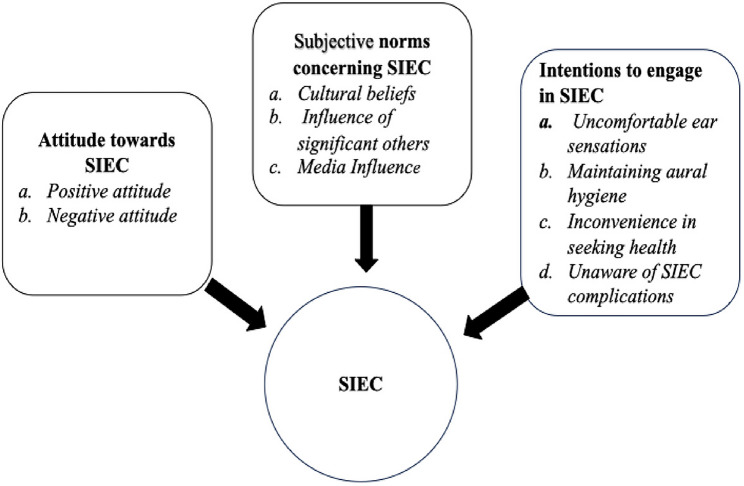

The data analysed was generated into three themes and nine sub-themes. Figure 1 shows the themes and associated subthemes. A detailed report of the themes and sub-themes follows the figure.

Fig. 1.

Themes and Sub-Themes on SIEC

Theme 1: attitude towards SIEC

Attitude refers to how individuals perceive and evaluate the SIEC practice. Participants' evaluation is shaped by how they see the consequences of their actions. Although SIEC practice is ideally unacceptable per the physiology of the ear, individuals instinctively engaged in it. They practised it unaware of what their actions may eventually lead to. The subthemes identified were negative attitude and positive attitude.

Subtheme 1.1: positive attitude

The positive behavioural attitude was when individuals sought medical attention for any incidence of ear problems. The description of participants revealed that they poorly evaluated the consequences of engaging in SIEC when there was an ear problem. Initially, they believed it was a good initiative to minimise or relieve their discomfort. A positive attitude surfaced after participants had gone through the worst experience of engaging in SIEC and reported to the hospital. Participants’ mindsets changed, and they decided to avoid ear cleaning at home. They were of the view that seeking health care is of prime importance on any issue related to the ear. Almost all the participants got to know the implications of SIEC at the hospital. They were not ready to compromise by using anything for their ear. This may be attributed to the fear they might have experienced with the complications. Therefore, the participants proclaimed that they would abstain from SIEC practices and report to the hospital with any ear issues. Some participants wished to advocate against SIEC.

“It is not good at all. When I see people practising self-induced ear care, I wish I could tell others to stop because complications with self-induced ear care are serious. I won’t advise anyone to practice it because it's a bad idea.” (Kojo)“It is not a good practice I will engage in again…it triggers complications which cause suffering. I would prefer to come to the hospital for a proper examination and the prescribed medicine, or check and know whether I have impacted wax in my ear” (Esi)

For most participants, their past experiences with foreign bodies in their ears informed the decision not to relent on SIEC but rather choose hospital treatment and other acceptable management options, such as massaging the outer ear.

“I have realised that it is not helpful because what I use always gets stuck in my ears, so I have stopped. Now, whenever the itchiness starts, I massage the outer part of my ear with my fingers and later, rush to the hospital for medical attention. (Adwoa)

Sub-theme 1.2: negative attitude

The negative attitude depicts the SIEC behaviours that participants gladly engaged in for their perceived comfort. This was because participants considered it a necessary intervention and a very convenient reaction to any ear sensation. The findings revealed that participants’ knowledge was a precursor for them to indulge in SIEC practices. Participants exhibited varied knowledge, which was based on their ignorance and poor understanding.

"I clean my ears because it makes me feel comfortable, and I don’t see anything wrong with it. No one will tamper with the ear when there is no disturbance. The basis is comfort; that is why people tamper with their ears. It starts with itching and the only way out is to put something in the ear, and that is the genesis of the problem.” (Rich).

Participants mentioned using various items to clean their ears, which span from cotton wool, matchsticks, pen caps, sponges, folded tissue, broomsticks, chicken feathers, hairpins, and safety pins, among others. Although a majority of the participants preferred cotton wool, some used multiple items depending on the availability and timing. The items may lead to the possible introduction of contaminants into the ear due to their unclean nature. Participants had this to say;

“I used cotton wool or sometimes my finger to remove the dirt in my ear. I saw it as first aid.” (Fred)“I peel off the feathers and leave the little ones at the tip to clean my ears.” (Nhyira)“… I use broomsticks, the pen cap, or anything that can be inserted into the ears about five times a day for 10 years now…” (Nana)

Some of the participants who inserted items deep in their ears complained of hearing problems and pains.

“Sometimes I take the tip of a piece of paper, I mean the toilet paper, I roll it and use the tip to stop the itching. Or I use the cotton bud. But I have realised that it goes deeper, and hearing becomes a problem.” (Kojo)“I was my own doctor and used anything available, even though it sometimes comes with pain as I push it deep to clean. I also use any available useful ointment.” (Celestine)

Furthermore, the pleasant sensations of the practice led to its repeatedness when there was discomfort or no discomfort from the ears. Most importantly, participants reminisced about the pleasant feelings with words like “tickling”, “very nice”,“pleasant”, and “sleepy”. The act they realised induces sleep and provides comfort momentarily when experiencing ear discomfort.

Oh, the feeling is very nice, tickling when you are cleaning the ears.” (Esi)“The chicken feathers give a pleasant feeling. It makes me sleepy sometimes. I even fall asleep while using it. So, I usually use it because of the pleasant feeling it gives me, very ticklish.” (Kofi).

For most of the participants, any indication of ear discomfort mostly warranted SIEC. Reform of negative attitudes leading to the avoidance of SIEC only occurred when they had visited the hospital. A lot more needs to be done to ensure that the populace does not lose their hearing, which is a key aspect of life.

Theme 2: subjective norms concerning SIEC

These are the influences from society that propelled the participants to practise SIEC. One of the primary motivations for complying with societal norms is the desire to be accepted and belong to a social group. People often conform to norms to avoid rejection, criticism, or ostracism from their peers and community. Individuals may internalise societal norms and values as they grow up, and they become part of their belief system. The description of participants also revealed the sources of their norms. The subthemes that were identified were cultural beliefs, influence of significant others and media influence.

Sub-theme 2.1: cultural beliefs

Cultural beliefs shape an individual’s ideologies and everyday life patterns. Participants described cultural beliefs as their way of life and norms concerning SIEC. These were the shared, transmitted and learned values that influenced one's behaviour. Participants considered the beliefs surrounding how to manage common ear ailments. Most of the participants affirmed the acceptance of SIEC as a common practice. Some used home remedies such as herbs, ointments, and oils for ear ailments, per their culture.

"In my Akan culture, self-inducedear care is seen as a normal practice. We believe in home remedies.” (Akua)“There is an ointment called Dr. Côte d'Ivoire that is inserted into the ears for pain and itching. It is sold at the information centre. Also, we use certain herbs. We squeeze the herbs and drop the juice into the ear” (Ama)“I usedpalmkernel oil for the pain and itching per our practice, but it didn’t work. I even switched to ginger preparation for the itching.”(Nana)

For local preparations, one of the participants mentioned that his wife advised him to apply a minty ointment (locally prepared) or boil-to-cool cooking oil. The ointment was for itching, while the boil-to-cool oil would kill the germs that were causing the pain.

“My wife also advised me to put some local minty ointment on the cotton bud and use it to clean my ears so the itching can stop. She also said I could boil cooking oil, allow it to cool slightly and pour it into my ear to kill (germs) whatever is causing pain.” (Rich)

Other participants reported that their culture demands self-reliance in managing minor health issues, including ear discomfort.

“In my community, societal norms emphasise self-reliance in managing minor health issues like ear discomfort. Many people believe that earwax is dirt and should be removed regularly, and traditional home remedies are often preferred over hospital visits due to cost and accessibility."(Kojo)"My cultural background promotes self-reliance and self-care. We have herbal remedies that have been passed down through generations, and I believe in their effectiveness."(Kwame)

Sub-theme 2.2: influence of significant others

Participants described how SIEC practices became part of them due to the influence of important persons in their lives. The significant persons were their peers, friends, family members, neighbours and concerned community members. Some of the participants practised SIEC because their close associates perceived it to be beneficial. The sharing of positive experiences made it very easy for them to engage in the practice without any caution.

"Many of my friends often self-clean their ears and have shared their positive experiences with me. It has influenced me to try self- induced ear cleaning as well, especially when my ears are dirty."(Nana)

They perceive it as a normative behaviour to maintain respect in the family. Also, elders are held in high esteem. It is believed that their wise counsel and practices are worth emulating. Disobedience to an elder is a mark of disrespect.

“You know, the elderly are always right, and they are the most respected and trusted. It is also believed that they are the wisest and most experienced, especially when it comes to herbal medicines. We just follow what they say.” (Kwesi)

The everyday practices portrayed by family members were duly followed.

“My parents and siblings have always practised self-inducedear care for minor ailments. Growing up, I saw them using cotton buds and applying robb on fowl feathers for common ear problems. It has become a norm in our family, and I also prefer self-induced ear care for non-serious ear conditions."(Cecelia)

Sub-theme 2.3: media Influence

The role of the media in SIEC was instrumental for a few participants as it shaped their understanding. It was established that the participants obtained information about SIEC through radio, television stations and online platforms. The messages promoted SIEC with medications as a quick and effective solution for common ear ailments. This instigated them to engage in such practices.

"I have noticed that advertisements frequently promote self-medication as a quick and easy solution for common ailments. The commercials often showcase how certain over-the-counter medications can provide fast relief, and this has influenced my perception that self-medication is a convenient and effective option."(Efua)“Through various online platforms and influencers, I have come across content that endorses self-care as an empowering and cost-effective approach. Seeing people share their positive experiences and recommendations for specific medications has contributed to my belief that self-inducedear care is a valid option" (Nhyira)

Theme 3: intentions of engaging in SIEC

Participants described their intentions as the individuals' motivation and willingness to engage in SIEC practices. The intention to engage in the practice was mainly associated with satisfying a particular need or feelings that preceded the practice. The needs of the participants varied from soothing discomfort felt from painful ears and itching to removing clogging wax identified as dirt to maintain their hygiene. Also, participants engaged in ear cleaning because it seems convenient than seeking health services at the hospital. It therefore served as a first aid measure to provide temporary relief from the uneasy feeling in the ears. Participants seem oblivious to the repercussions of their actions at the time. The subthemes derived were: uncomfortable ear sensations, maintaining aural hygiene, inconvenience in seeking health care and unawareness of SIEC complications.

Sub-theme 3.1: uncomfortable ear sensations

The primary concern of participants in this study that led to the act of SIEC was the persistent feeling of discomfort in the ears. This was described in various forms such as “heaviness”, “sensation”,” awkward sounds” in the ears, “pain”, “sensation of a foreign body” in the ears, and “itching”. These feelings were associated with water entering the ears after a bath, leading to a feeling of fullness, obvious discharge or discomfort of no origin in the ears. Participants mentioned that the feeling of discomfort occurred at any time during the day. A participant narrated that:

“…the itchiness can just occur and become very severe, especially at night…Sometimes, I feel there is something stuck inside my ears, so I use a cotton bud to clean it.”(Adwoa).“I felt this heaviness sensation in the ears accompanied by some awkward sounds, so I used the cotton bud with the view of getting some relief.” (Kofi)

Some participants cleaned their ears after bathing when water entered them. This may seem meaningful, but it is not appropriate.

”I clean my ear whenever water enters my ear after bathing because it feels funny” (Alima)

Participants, therefore, engaged in SIEC to relieve their discomfort

Subtheme 3.2: maintaining aural hygiene

Personal hygiene is part of an individual’s daily routine. Some participants in this study were noticed to engage in the practice almost daily to ensure their aural hygiene. The frequency (several times a day to once daily) of SIEC was based on the notion that anytime they poked their ears, something came out which they perceived as dirt. This kind of mindset was peculiar to some participants, possibly to enhance their hearing.

Some participants use their first means of assessing the ear to determine the next steps to take or initiate further cleaning.

“Sometimes, I feel there is something like dirt stuck inside my ears, so I poke my finger into it, and when something comes out, I use the cotton bud to clean it.” (Adowa).

Participants cleaned their ears mainly because the earwax was perceived by significant others as dirt, and they felt pressured to get rid of the earwax in order to hear better. For these participants, achieving that goal was the ultimate.

“… For me, I don’t feel comfortable when someone sees the dirt in my ears, and besides, I think cleaning your ears is part of maintaining my hygiene. Usually, at home, I see babies' ears cleaned after they are bathed. As for me, I clean my ears about five times a day” (Kofi). “I learnt the dirt in my ears comes about as a result of smoke and dust in the environment, so I clean it to prevent accumulation of dirt and to make my ears clean.” (Ekua)

To maintain aural hygiene, a few deliberately ensured that water entered their ears while bathing.

“Sometimes, I ensure that water enters the ears when bathing, so I clean it…I try all means to get it out.” (Nana)

Sub-theme 3.3: inconveniences in seeking health care

The inconveniences in seeking health care were based on their past encounters at the hospital, such as long waiting periods and frequent visits to the hospital in order to get rid of the discomfort, which invariably may not be achieved. Participants wanted to avoid the long queues at the hospital and unwanted delays to ensure that they do not miss out on their jobs, which provide them with income. Participants indicated the duration they spent at the hospital seeking treatment as follows:

“…I spent about three days going to the hospital, but I wasn’t getting the desired results.”(Fred).

The bureaucratic processes, coupled with the network challenges of the paperless system in the hospital, contribute to delays at the hospital. Sometimes participants had to contend with the cost of treatment because medications covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) were unavailable at the pharmacy. Those who had not signed up for NHIS had to pay cash for all their bills, which they considered expensive. Apart from the issues mentioned, the distance to the facility also increased the cost of seeking healthcare. Some travelled far to access services because facilities in their location did not provide ENT services.

“…I couldn’t get all the prescriptions because some of the drugs were not covered by NHIS, and they did not have them in stock either. The network messed up,so I had to sit there for a very long time. After the long wait, I got only one medicine. I had to buy the remaining outside.” (Cecelia) “Sometimes, it is financial, distance, and time… I may not have money at the time I experience the ear problem, and travelling to the hospital is quite a distance. I had to prioritise work; otherwise, my boss would not understand, so I just decided to use olive oil and a cotton bud at that moment. I knew olive oil is used in the hospital, so it's ok” (Alima)

One participant also narrated her ordeal about a health personnel she once encountered, contributing to the decision not to report to the hospital.

“I had an experience with a doctor. When I entered the consulting room, I sat down, but he told me to go out because he didn’t offer me a seat. That day, I couldn’t open up on exactly what was wrong with me. I had to lie. Due to that incident, going to the hospital was very difficult for me”. (Efua)

Sub-theme 3.4: unaware of SIEC complications

The posture of participants showed that they were ignorant of SIEC complications, and the fact that itchy ears are a health concern that should be reported to the hospital. They were unaware of what a single cleaning of the ear could lead to, thus engaging in such practices. For instance, one patient posited that:

“I didn’t know that I had to report to the hospital when it itches. I used other things to clean it, and that became problematic. A lot of people do not know that when the ear itches, they must report to the hospital.” (Ekua)

Others engaged in SIEC regularly without any caution until they started having adverse effects.

“It never occurred to me that I would get hurt while at it. Whenever the itchiness starts, I clean itbecause my hearing was still good. I came to the hospital after realising that I could not hear.” (Ama)“Initially, I didn’t know anything about ear problems, so anything goes for me, provided it solves my problem, until it has now given me a permanent hole in my ear which often discharges”. (Esi)

The outcome of the practice impacted the daily lives of participants in such a way that some could not concentrate in class, eat or sleep at night, while others had to stay out of work. Participants mentioned that:

“It has given me a lot of pain. When I am in pain, it prevents me from doing a lot of things. Sometimes, I can’t even concentrate in class. I can’t eat too. I will be dull and quiet throughout the day. It prevents me from doing a lot of things on my schedule. The pain is very severe” (Nana)“... the cleaning at a point causes pain...It is very painful and causes sleepless nights. I had breathing difficulties as well.” (Kojo)

Discussion

The study explored the experiences of SIEC practices among patients using the TRA. Generally, the findings of the study aligned with the constructs of TRA, which indicates that behavioural intention, attitude and subjective norms influenced participants to engage in SIEC [32]. Specifically, participants’ negative attitudes coupled with adherence to norms and their intentions to maintain aural hygiene and relieve discomfort led to SIEC behaviour. Also, participants' narrations revealed nuances pertaining to their attitude. This is linked to participants' understanding towards maintaining their hearing abilities if a problem arises. In that, the knowledge of most participants towards the ramifications of SIEC was inappropriate because they inserted anything, such as pen covers, fingers, keys, broomsticks, tissues, palm kernel oil, and cotton buds, to clean or reduce ear discomfort. The findings are congruent with several studies that attributed SIEC practice to a lack of or inadequate knowledge and ignorance of possible complications [2, 4, 28]. Contrarily, Tobih et al. revealed that the majority of participants have good knowledge about the complications of self-induced ear cleaning, but that did not deter them from engaging in the practice [26]. It is therefore not surprising that, in this present study, some participants reported on the repeated practice, possibly due to the pleasant feeling they experienced or the purpose it served. This may have contributed to health professionals engaging in SIEC practices [37] even though they are aware of the adverse effects. Also, the same items used by participants in this study have been documented in the literature [4, 15, 24]; however, based on context, what seems different is the use of broomsticks and palm kernel oil. This may be attributed to the fact that it was readily available or proven to be effective. The introduction of broomsticks and palm kernel oil would likely lead to individuals losing their ear integrity in the future. Broomsticks can easily pierce the eardrum, while the impurities in palm kernel oil can be the source of contaminants, leading to infections.

Negative experiences created some fear, uncertainty, and reluctance to repeat the same actions. In terms of participants' perspectives on SIEC, this changed after reporting to the hospital with persistent symptoms or complications. A positive attitude was portrayed in their utterances to avoid SIEC and become advocates. Participants who are willing to be advocates can be included in educational campaigns to share their stories. This would enable the public to understand the realities of indulging in such behaviours.

Additionally, the quest of participants to avoid hospitalisation with its bureaucratic systems, unplanned costs and delays from long waiting instead led to frequent hospital visits and a negative impact on their daily routines. It led to absenteeism from work and low productivity. These unforeseen circumstances were associated with possible complications such as otitis externa from bacterial and fungal infection caused by the items for cleaning [26, 38]. This suggests that work schedules did not permit participants to spend long periods at the hospital. They therefore struggled to prioritise ear health services. The lack of time available for hospital visits may have prevented them from seeking professional guidance for their ear care needs.

Participants in this current study preferred ear care options that were more affordable and accessible, especially as they considered the symptoms as minor or non-serious. Evidence reports that over-the-counter ear drops or home/traditional remedies were preferred and often chosen as a cost-saving measure by individuals who perceived their condition as manageable without professional intervention [17, 39]. This may account for the use of palm kernel oil, which is usually prepared at home by individuals. It is believed that SIEC options are more affordable than visiting a healthcare provider. This is to curtail incurring transportation costs and the incidence of obtaining a prescription medication, which, though covered by the NHIS, may be unavailable, amounting to further cost.

Influences from significant others and cultural beliefs encouraged the SIEC practices. In Ghana, elders’ advice or recommendations are valued. Participants in this study obeyed their elders and other family members without question. SIEC was a common phenomenon for some families, where even babies’ ears were cleaned routinely to remove dirt. Observation of such practices may have built the confidence of individuals to live up to such standards. Therefore, people may engage frequently in SIEC as long as they experience discomfort or no discomfort. Cultural beliefs or values influence the preferences, prioritisation of needs and health-seeking behaviour of an individual [40]. Therefore, nurses should focus on understanding the cultural dynamics of individuals to better understand their subjective reality when providing care.

Also, the focus of cleaning as pertained in literature was to relieve discomfort associated with heaviness, awkward sounds, pain, the perception of a foreign body in the ear, and itching [15, 21, 25, 41]. In reference to cleaning as a means of aural hygiene, it is disclosed that the practice was to remove excess water, especially among children, after bathing. This may account for the practice as a norm among children in this current study [42]. Also, a few of the participants reported on deliberately ensuring that water enters the ear while bathing for cleaning purposes. Although this may seem appropriate for hygienic purposes, such a practice may lead to unhelpful outcomes and should be avoided.

Likewise, in connection with cleaning to remove dirt, most studies affirmed that wax is recognised as dirt that needs to be removed pre-empting SIEC practices [2, 4, 43]. This mindset is a worry, coupled with the fact that this present study identified media as influencing the practice. The premise is that information frequently heard or seen over time becomes an acceptable phenomenon for the mind and easier to emulate. This may have instigated some individuals to go into the SIEC norm. Additionally, most people believe and accept any information from the media without verification as a means of filtering the information. It is important that the public have access to appropriate information on health issues and have the means of verifying information before deciding on health-related matters.

This study, therefore, revealed that SIEC practices were standard among patients visiting the ENT clinic due to a lack of knowledge. It also suggested that when patients are equipped with appropriate knowledge, they would be better positioned to make the right decisions towards their health. In this regard, it can be pre-empted from TRA based on this phenomenon that a strong positive attitude, embodied with adequate knowledge sources, could lead to patients desisting from SIEC and seeking medical attention.

Conclusion

The study found that although SIEC is associated with momentary comfort, it leads to discomfort and future ear complications. The participants were generally unaware of the possible complications of engaging in SIEC when they encountered an ear problem. Therefore, stakeholders must deliberate on sensitisation campaigns and educational strategies that would elicit a change of mind and ensure positive health-seeking behaviours. Mobile clinics on ear health campaigns should be instituted for hard-to-reach communities to promote broad coverage of public awareness. Lastly, the Ministry of Health must create accessible media platforms through social media platforms where patients can easily access and verify information prior to any actions.

Limitation

The qualitative approach employed for the study was instrumental in understanding the issues inherent in participants’ experience because of its flexibility in questioning. It enabled the researchers to understand the intentions, attitudes and norms associated with participants engaging in the phenomenon. The study focused on a relatively small sample due to the approach of investigation. The findings are therefore transferable to a similar setting based on context. There is potential for researchers’ bias due to the purposive nature of the sampling technique and because the researchers are instrumental in the co-creation of realities. To minimise such biases, the researchers employed rigour with strategies such as peer debriefing, discussion of audit trail and reflections. Also, a clear inclusion criterion was set to mitigate the biases of selection. It is suggested that in future, other researchers conduct a longitudinal study that will follow patients over time to provide a deeper understanding of their SIEC experiences.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to DNB and all the clients who participated in this study.

Authors’ contributions

JAD and VAA conceptualised the study. JAD conducted all interviews, while all authors (JAD & VAA) participated in the data analysis and generated the findings report. JAD, ONM, and VAA also participated in writing sections of the manuscript and reviewing it for submission.

Funding

Not Applicable

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (GHS-ERC 045/03/23) awarded ethical clearance. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was also obtained from all participants who were involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harkin H. The structure and function of the ear and its role in hearing and balance. Nurs Times. 2021;117(4):56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lukolo LN, Kimera LC, Pilbee G. Self-Ear cleaning practices and the associated risks: A systematic. Editorial Board. 2021;13(5):44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oladeji SM, Babatunde OT, Babatunde LB, Sogebi OA. Knowledge of cerumen and effect of ear self-cleaning among health workers in a tertiary hospital. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2015;5(2):117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haji A, Alharbi B, Alhazmi K, Alharthi B, Kabli A, Siddiqui MI. The knowledge, attitudes, and practices of self-ear cleaning in Makkah region, cross-sectional study: self-ear cleaning. Saudi Med Horizons J. 2021;1(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alenezi NG, Alenazi AA, Elboraei YAE, Alenazi AA, Alanazi TH, Alruwaili AK, et al. Ear diseases and factors associated with ear infections among the elderly attending hospital in Arar city, Northern Saudi Arabia. Electron Physician. 2017;9(9):5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graydon K, Waterworth C, Miller H, Gunasekera H. Global burden of hearing impairment and ear disease. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133(1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaspar A, Pifeleti S, Driscoll C. The role of health promotion in the development of ear and hearing health services in the Pacific islands: A literature review. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:2050312121993287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Vecchi Brumatti L, Bavcar A, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organisation. Addressing the rising prevalence of hearing loss. In: Addressing the rising prevalence of hearing loss. 2018 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/who-260336

- 10.World Health Organisation. World report on hearing. World Health Organisation; 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=zMRqEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=WHO+world+report+on+hearing&ots=cHzmD-89Mv&sig=0gjmrcQhrUkNyoifsBWnjN8aO5s

- 11.McDaid D, Park AL, Chadha S. Estimating the global costs of hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(3):162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadha S, Kamenov K, Cieza A. The world report on hearing, 2021. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(4):242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almagribi AZM. Ear care: knowledge, behaviour, and attitudes among healthcare practitioners in Najran city, Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(6):e0303761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdulrahman KAB, Alhazani FA, Alayed FT, Alomar AA, AlSarrani AH, Albalawi AM, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of self-ear cleaning among the general population in riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Middle East J Family Med. 2022;7(10):128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan NB, Thaver S, Govender SM. Self-ear cleaning practices and the associated risk of ear injuries and ear-related symptoms in a group of university students. J Public Health Afr. 2017;8(2):555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adegbiji WA, Olajide GT, Olubi O, Aluko AA. A study profile of self-ear cleaning in Nigerian rural community. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2018;9(7):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alshehri A, Asiri KA, Alahmari M, Alwabel H, Alahmari Y, Mahmood S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of self-ear cleaning among medical and non-medical students at King Khalid university, abha, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Dev Ctries. 2020;4(6):960–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballachanda BB, Poojar B. Earwax–cerumen genetics and physiology: current insights and long-term implications. J All India Inst Speech Hear. 2024;43(1):2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swain SK, Sahu MC, Debta P, Baisakh MR. Antimicrobial properties of human cerumen. Apollo Med. 2018;15(4):197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz SR, Magit AE, Rosenfeld RM, Ballachanda BB, Hackell JM, Krouse HJ et al. Clinical Practice Guideline (Update): Earwax (Cerumen Impaction). Otolaryngol–head neck surg [Internet]. 2017 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 18];156(S1). Available from: https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599816671491 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Beigh Z, Islam OU, Khalid F. Cotton bud misuse in children: cause of resistant otitis externa. Curr Pediatr. 2022;26:1517–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bukhari SMAS, Aslam S, Afzal M, Riaz N, Abbas A, Afridi JA, et al. SELF-CLEANING OF EARS BY VARIOUS OBJECTS CAUSES MULTIPLE DISEASES OF THE EXTERNAL EAR. Contact Dermat. 2021;11:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segun-Busari S, Afolabi AO, Omokanye HK, Ayodele SO, Dunmade AD, Sulyman AB, et al. Malignant otitis externa in a tertiary hospital, North central region of nigeria: A 15-Year review. Nigerian J Basic Clin Sci. 2024;21(2):150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khadka S, Shakya A, Rimal S, Knowledge. Attitude and practice of Self-Ear cleaning among medical students at KIST medical college teaching hospital. J KIST Med Coll. 2023;5(9):35–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olajide TG, Olajuyin OA, Eletta AP, Agboola SM, Busari AO, Adebara I. Self ear cleaning: prevalence and profile among school children in Ekiti, Nigeria. J Biosci Med. 2019;7:25-32.

- 26.Tobih JE, Esan TO, Esan DT, Ojumu IJ. Self-ear cleaning practices and hazards among undergraduates of a private university in Nigeria. Acta Sci Med Sci. 2021;5(12):151-7.

- 27.Abdullahi M, Aliyu D. Risk factors of acute otitis externa seen in patients in a Nigerian tertiary institution. Sahel Med J. 2016;19(3):146–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afolabi AO, Kodiya AM, Bakari A, Ahmad BM. Attitude of self-ear cleaning in black Africans: any benefit? East African Journal of Public Health. 2009 [cited 2025 Mar 18];6(1). Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=08568960&AN=59336328&h=8KqJYTKuzSnePe7uSb7Sx626LetCcEQYaFZ3Xx8%2BNOs9RHT5%2BHZWZbKaHBXWw42FOfn1lq8wMO%2F8%2FKNqgGL7Gw%3D%3D&crl=c [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Agyemang CO, Opoku OA, Osragbo RM, Alhassan U, Mensah ON, Opoku A. Effects of Non-Existent ear, nose, and throat clinics on residents seeking health care at Adankwame health centre in Ashanti region, Ghana. J Appl Nurs Health. 2024;6(2):353–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opoku AO, Agyemang CO, Yussif S, Okudzeto H. Exploring the knowledge, attitude, and practice of parents of under-five children with otitis media at the Mampong municipal hospital, Ghana. J Appl Nurs Health. 2023;5(1):97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edward M, Akanlig-Pare G. Societal perception of hearing impairment in Ghana: A report on Adamorobe. 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 1]; Available from: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/28927/2/Societal%20perception%20of%20hearing%20impairment.pdf

- 32.Ajzen I. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood cliffs. 1980 [cited 2025 Jul 1]; Available from: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572543024551612928

- 33.Hunter D, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. Journal of Nursing and Health Care. 2019 [cited 2025 Mar 18];4(1). Available from: https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/180272

- 34.Fusch PDPI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 19]; Available from: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/facpubs/455/

- 35.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed SK. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;2:100051. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adoga AA, Nimkur TL. Ear care: knowledge, attitude and practice amongst health professionals at the Jos university teaching hospital. East Afr J Public Health. 2013;10(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afolabi OA, Ehalaiye BF, Fadare JO, Abdur-Rahman AB, Ehalaiye DN. Survey of ototopical self-medication among patients attending ENT and family medicine departments in a Nigerian hospital. Eur J Gen Pract. 2011;17(3):167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kıroğlu O, Berktaş F, Khan Z, Dağkıran M, Karatas Y. Self-medication practices with conventional and herbal drugs among ear, nose, and throat patients. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2022;68(10):1416–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singleton K, Krause E. Understanding cultural and linguistic barriers to health literacy. Online J Issues Nurs. 2009;14(3). [PubMed]

- 41.Alhazmi WA, Alshammari AM, Almutairi AS, Alshweash MK, Alshammari SM, Alrashidi HM et al. Self-ear cleaning practice and the associated ear-related symptoms and injuries among medical students [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: http://discoveryjournals.org/medicalscience/current_issue/v26/n130/ms573e2660.pdf

- 42.Shawish AM, Hobani AH, Zaalah LA, Hakami RA, Alharbi GH, Alhazmi RM et al. The Awareness Among Parents About Cotton Earbud (Q-tips) Use in Children in the Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus [Internet]. 2023:[cited 2025 Mar 19];15(8). Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/175388-the-awareness-among-parents-about-cotton-earbud-q-tips-use-in-children-in-the-jazan-region-saudi-arabia-a-cross-sectional-study.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Amutta SB, Yunusa MA, Iseh KR, Obembe A, Egili E, Aliyu D, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of self ear cleaning in Sokoto metropolis. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;2(6):276–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript