Abstract

Introduction

Distress is experienced by more than 30% of patients during palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at the end of life in the intensive care unit. There is a lack of high-quality evidence for specific approaches to risk factor identification and management of distress during this process. Structured “time-outs” and checklist interventions improve surgical outcomes and have been widely adopted in procedural care, but they have not been tested for use at end-of-life in intensive care unit settings.

Methods

We describe the development and planned testing of a novel time-out checklist intervention, the Comfort Measures Only Time Out (CMOT) in a non-randomized single arm pilot study. Intervention development was guided by published literature and a structured inter-professional advisory panel. The intervention will be tested by clinical teams caring for 46 patients undergoing palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation. Nurses, physicians, advanced practice providers, and respiratory therapists will convene within an hour before withdrawal of mechanical ventilation to complete the checklist. Implementation outcomes, including feasibility, will be measured by a 12-question survey and by clinician protocol adherence. Effect size calculations will determine power for future randomized controlled trials testing efficacy of the CMOT in reducing patient distress.

Discussion

This protocol will pilot test the feasibility of the CMOT, a structured time-out and checklist intervention, for WMV in the ICU. The study will inform potential changes to the protocol and intervention for a future randomized control trial. The CMOT is grounded in a quality and safety framework already adopted in procedural and critical care settings. Given high rates of distress, the CMOT will fill an identified gap in evidence surrounding the process of WMV.

Trial Registration

Clinical trials.gov (NCT05861323); 16 May 2023.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40814-025-01688-4.

Introduction

Contributions to the literature

This study is designed to improve end of life care in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) by pilot testing an inter-professional team-based checklist intervention for improving the process of palliative Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (WMV) at the end of life.

Demonstration of feasibility of the intervention will allow for larger-scale implementation and evaluation.

Background and rationale

Prior estimates suggest 25% of Americans die in intensive care units (ICUs) [1, 2], and recent trends support greater utilization of ICUs at or near end of life [3]. Most ICU deaths involve a transition to comfort-focused care with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (WMV) [4], and yet there is limited evidence guiding the process [5].

A recent review identified several research gaps, including a lack of evidence to favor either of the two main approaches to WMV at end of life (terminal extubation and terminal weaning) [6]. Despite high-quality studies supporting the efficacy of medication [6], their integration into clinical practice is limited by a lack of knowledge regarding risk factor identification and symptom management during WMV [7–10]. A better understanding of the optimal process for WMV is needed given growing evidence that distress during WMV in the ICU setting is very common [11–14]. Studies suggest that more than 30% of patients experience signs of respiratory distress, such as sustained tachypnea, after WMV [15]. Poor symptom control can contribute to moral distress among families and caregivers [16]. Implementation of existing best practices may be accomplished through interventions that focus on engaging and supporting the ICU team [17, 18]. A recently completed observational study of palliative WMV (OBSERVE-WMV) further identified both communication and planning as essential components of high-quality WMV [19].

Despite the adoption of order sets, practice variation remains a contributor to poor symptom control during WMV [12, 17, 20–24]. The time-out structure provides the opportunity for input from key members of the multidisciplinary ICU team for individualized care planning [25]. Structured “time-outs” and checklist interventions have been shown to improve surgical outcomes [26, 27] and have been widely adopted into routine ICU procedural care [28–31]. One study of checklists in ICU palliative care showed improved fidelity in confirming goals of care but did not encompass WMV [32]. Another study showed improvement in clinician communication but did not include structured assessment for patient distress using symptom scales [11, 20, 33]. A multidisciplinary checklist intervention for structured medical decision-making and ICU team support is a promising tool that has yet to be established for the WMV process.

Aims and hypotheses

The primary aim of the Comfort Measures Only Time out (CMOT) study is to establish the feasibility of an ICU team-based checklist and time-out intervention for WMV in the ICU setting. Feasibility will be assessed by recruitment rate, protocol adherence, and acceptability to clinicians (e.g., helpfulness, endorsement for future use). We hypothesize the CMOT protocol will achieve > 50% recruitment, > 75% clinician training participation, and > 85% protocol adherence. Patient-level data will also be collected from this feasibility study to establish a trend toward fewer episodes of distress among patients undergoing WMV.

Methods: study protocol

This study was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board. The trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05861323).

Trial design

This pilot study will adhere to the CONSORT Extension Guidelines for Reporting Pilot Trials (Appendix 1). The intervention (use of the CMOT by the multi-disciplinary care team) will be implemented in non-randomized, single-arm pilot study among a convenience sample of teams caring for 46 adult WMV patients in 7 ICUs (3-medical, and 1-surgical, trauma, cardiac, and neurological ICU respectively) at a single academic tertiary care center. Participating clinicians will be asked to complete the CMOT, and feasibility endpoints will be assessed via survey. Based on design recommendations for pilot studies [34], a sample size of n = 46 is expected to be sufficient for determining CMOT completion rate, and an estimated 138 survey responses (3 clinicians per enrolled patient) for determining acceptability and appropriateness of the intervention [35].

Intervention development

The content of the CMOT was guided by the published literature [6], findings from OBSERVE-WMV [17], and structured development panel of experts (Appendix 2). The CMOT builds upon existing approaches to WMV [17] and encourages best practices in-line with recent evidence supporting the use of a nurse-led algorithm [36]. The development panel consisted of six local and national experts in critical care nursing (n = 2), medical and surgical critical care (n = 2), pulmonary care (n = 1), and geriatrics (n = 1). The development panel was composed of nurses and physicians. Feedback from respiratory therapists will be incorporated in final revisions of the CMOT following enrollment of the first six patients. Individual content experts on the panel were engaged initially via email, followed by iterative revisions of the draft CMOT with the full panel. The full panel was then convened via live video-conference for open discussion to provide feedback on the content and structure of the final version of the CMOT.

Intervention

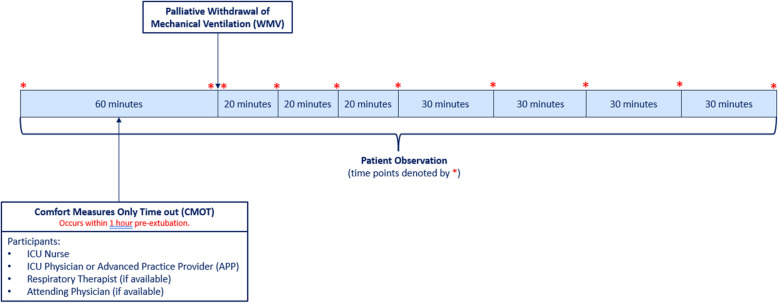

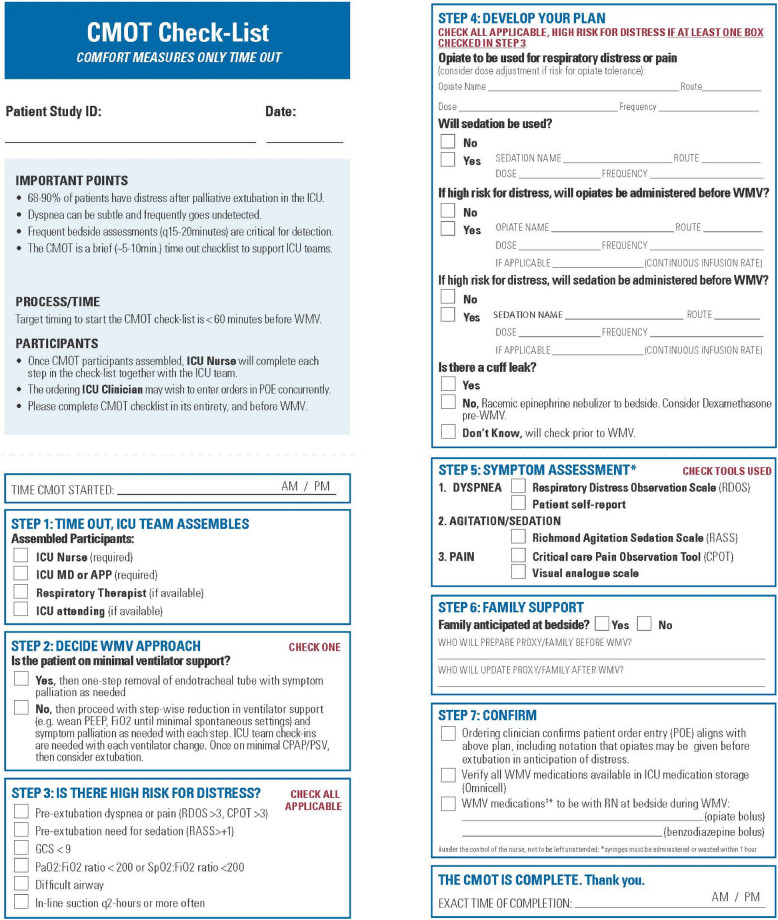

The ICU team (ICU nurse, physician/APP, and, if available, respiratory therapist) will convene as close as possible to the withdrawal of mechanical ventilation, targeting less than 60 min prior to WMV. An intervention timeline and data collection time points are provided in Fig. 1. Once participants have assembled, the start time will be recorded, and the ICU nurse will complete each step in the CMOT checklist (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Timing of CMOT events and data collection. Legend: The intensive care unit (ICU) team will convene within 1 h of palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (WMV) to complete the Comfort Measures Only Time out (CMOT) check list. The ICU nurse will assess the patient for distress at 10 designated time points (1-h pre-WMV, immediately before and after WMV, every 20 min for 1 h post-WMV, then every 30-min up to 3-h post-WMV). Abbreviations: advanced practice provider (APP), Comfort Measures Only Time out (CMOT), intensive care unit (ICU), withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (WMV)

Fig. 2.

The Comfort Measures Only Time out. Legend: The Comfort Measures Only Time out will be completed by clinical teams caring for patients undergoing palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation

The team will first decide on the approach, either one-step removal (terminal extubation) or step-wise reduction in ventilator support (rapid terminal weaning), depending on the patient’s ventilator support settings and ICU team practice patterns (Fig. 2). Next, patient risk factors for respiratory distress will be identified. The team will then review the medication plan for both anticipatory dosing of opiates and sedatives (if applicable) and symptom palliation. The patient will also be assessed for an endotracheal tube cuff leak. If there is no cuff leak, racemic epinephrine nebulizer will be brought to the bedside, and the team will consider whether to administer dexamethasone before WMV.

In the next step, the team will identify applicable symptom assessment tools for measuring distress, including dyspnea, agitation/sedation, and pain (Fig. 2). Clinicians will identify the team member responsible for preparing the patient’s family/medical proxy for WMV and providing them with updates. In the final step, the physician or APP will check that the patient entry order aligns with the outlined plan, confirming medication dose, route, and immediate availability. The ICU nurse and ordering clinician will also confirm their presence at bedside during and three minutes after WMV. At this point, the CMOT time of completion will be recorded.

Intervention field test

The first six patients enrolled will be part of the intervention field test. Results from the clinician survey and feedback from participants will guide iterative refinement of the CMOT checklist. The expert panel will again evaluate the field tested CMOT and convene for open discussion and review of the final refined version. The final revised version will then be pilot tested with clinical teams caring for 40 patients.

Participants

Eligible clinicians will be registered nurses (RN), physicians, advanced practice providers (APP), and respiratory therapists (RT) over the age of 18 who provide direct care to the patient for at least 1 h prior to WMV. Lack of English fluency will be the only exclusion criteria. Eligible patients must be over the age of 18 years old, and endotracheally intubated with a decision made for WMV (but not yet extubated) in the ICU. A waiver of informed consent was granted for patients in this study. Death by neurologic criteria (brain death) will be the only patient exclusion criteria.

Protocol training

Training and recruitment will be conducted in collaboration with ICU clinical leaders. One clinician in each ICU will be designated the “CMOT Champion” and will be responsible for leading field testing and serve as a resource for others. Prior to launch, site champions will meet with the study team to review the process and provide feedback for further refinement.

The CMOT Champion will also identify clinicians anticipated to provide care in the ICU during the duration of the study enrollment period. The research team will then contact these eligible clinician participants to invite them to a 20-min, in-person training seminar. Verbal consent will be obtained before participation in these sessions. Clinicians who consent to participate but are unable to complete in-person training will be invited to complete an online training seminar via email.

Screening/enrollment

The research assistant (RA) will ask teams in each of the participating ICUs to identify potentially eligible patients each day during the enrollment period. Clinicians participating in the planned extubation will be invited to participate in the CMOT. While most clinicians will have attended a training session previously, the RA will offer a brief training to those who are unfamiliar with the study and will obtain verbal consent at this time.

Clinician survey

Following completion of the CMOT, the RA will administer a five-minute written survey (Appendix 3) to each member of the ICU team to obtain clinician perspectives on the intervention. Open-ended questions will explore what did and did not go well with the CMOT process. Closed-ended questions will ask clinicians to rate components of the intervention including ease of use, relevance, and utility on a Likert scale. Basic demographic information for each clinician will be collected. The survey will be administered to each participating clinician caring for a patient during WMV. Clinicians may participate in the intervention up to a maximum of three times if caring for multiple patients meeting inclusion criteria during the enrollment period.

Methods: data sources and management

Data collection

Data will be collected at multiple time points (Fig. 1) and entered into a secure electronic research database (REDCap). Once an eligible patient has been identified, the RA will obtain demographic information and illness severity from a baseline electronic health record (EHR) review.

Feasibility endpoints

The feasibility of the intervention will be measured by recruitment rate and protocol adherence. Recruitment rate for clinicians will be defined as the proportion of eligible clinicians who consent to participate and attend an in-person training seminar, or complete training prior to enrollment of a patient. Patient recruitment rates will be calculated from screening logs as the proportion of enrolled patient-ICU teams proceeding with the CMOT over the number of eligible patients identified during daily screening. Protocol adherence will be defined in two ways: (1) time out completion rate: defined as the proportion of recruited patients for whom there was a documented time-out prior to WMV, and (2) checklist completion rate: defined as the number of completed items versus total to be assessed after each CMOT by study staff.

Implementation endpoints of acceptability and appropriateness of the intervention [37] will be assessed from responses to the CMOT Clinician Survey (Appendix 4). Acceptability will be ascertained from the question, “Would you recommend the CMOT be used in the future?” with response options (Yes, No, Don’t Know, and Prefer not to answer). Appropriateness will be assessed by the question, “Do you feel the CMOT is relevant to clinical care?” with responses on a Likert scale (range 1–10, lower scores indicating disapproval). Basic demographic information (age, gender, race, ethnicity) will be collected. Written open-form feedback will be collected in the survey, and any verbal feedback will be transcribed verbatim at the time of data collection. Quantitative results will be summarized using descriptive statistics as applicable. In order to maximize recall of relevant events, the survey will be completed within 48-h following extubation but ideally will be administered directly following completion of the checklist. Participants who do not complete a same-day survey will be sent an electronic copy to be completed within 48 h.

Survey results will inform the decision to proceed with a future randomized control trial (RCT) to test the effectiveness of the intervention. The following criteria will be used: (1) at least 50% of the clinicians screened as eligible agree to participate. The trial will not be feasible if recruitment is 20% or less; (2) protocol adherence of 85% or more clinicians will complete the CMOT in full. If fewer than 50% complete the CMOT as specified, then the trial is not feasible; and 3) a majority (> 50%) of clinicians should recommend the CMOT for future use, either in its current form or with modifications.

Clinical outcomes

An episode of distressful symptoms will be defined as follows: For each 30-min interval from extubation until death (or up to 3 h), distressful symptom episodes will be determined by the occurrence of either respiratory distress (defined as either self-reported breathing difficulty rated ≥ 5 [38, 39] or RDOS ≥ 3 [40]) or pain (either a visual analogue or CPOT score ≥ 3 [41, 42]). Measures of distress will be observed and recorded by the ICU nurse at the time of extubation, every 20 min following for 1 h, and every 30 min up to 3 h post-extubation (or until time of death). Respiratory distress in patients unable to self-report will be measured via the Respiratory Distress Observation Score (RDOS) (range 0–16, higher scores indicate worse distress, ≥ 3 mild-severe) [40]. Patients able to self-report dyspnea will be asked by the RN, “are you short of breath?” and asked to rank from 0 (none) to 10 (most severe) [38, 39].

Pain will be measured using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (range 0–10, score > 3 indicates mild or greater) and the clinical pain observation tool (CPOT) (range 0–8, scores ≥ 3 indicate pain) [42]. Agitation and sedation will be scored using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) (range − 5 to + 4, scores < 0 indicate sedation) [43]. A post-death EHR review will be used to collect data in the following categories (see Table 1 for definitions): risk factors for respiratory distress (measured within 24 h pre-extubation), pharmacologic symptom management, consultations, time of CMO order, and time of death.

Table 1.

Patient data elements to be collected

| Category | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Age, gender, race, ICU length of stay, admitting service (e.g., surgery, medicine) |

| Illness severity | Primary and secondary diagnoses, duration of mechanical ventilation (days), and the following scales*: GCS score (range 3–15, lower scores indicate less awareness) [44], Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) (range 0–163, higher scores indicate greater mortality risk) [45] |

| Risk factors for distress* | Endotracheal tube cuff leak (present/absent), pneumonia, positive fluid balance (> 500 ml 24 h before extubation) [46], copious secretions (> q2-h suctioning required), absent gag reflex, weak cough (cough peak flow (CPF < 60 l/min)) [47], and Confusion Assessment Method-ICU score (CAM positive indicates delirium) [48] |

| Measures of distress | RDOS (or self-report), RASS, and CPOT scores will be collected at regular time intervals (described above) |

| Pharmacologic symptom management | Administration of the following drugs collected from 1 h pre-extubation up to 3 h post-extubation or until death: opioids, benzodiazepines, dexmedetomidine, haloperidol, antimuscarinic drugs, racemic epinephrine, corticosteroids, and loop diuretics |

| Time of CMO order | Hours from time of comfort measures only (CMO) order to extubation |

| Time of death | Hours from extubation until death |

| ICU characteristics | Number of beds, type (surgical, medical) |

Abbreviations: ICU intensive care unit, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score, CPF cough peak flow, CAM-ICU Confusion Assessment Method-ICU, RDOS respiratory distress observation scale, RASS Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale, CPOT clinical pain observation tool, CMO comfort measures only

*Measures must be recorded within 24 h of extubation. If multiple recordings are available, the measure recorded closest to the time of extubation will be used

Participant retention

The RA will follow up with clinicians in person to encourage survey completion following completion of the CMOT within the target of 48 h after WMV. Email reminders will be sent if the clinician is not available to complete the survey immediately following completion of the CMOT.

Analyses

Statistical analysis

Feasibility endpoints of recruitment rate, time-out completion rate, and checklist completion rates will be described using proportions, median, and interquartile range, and stratified by ICU type. Measures of acceptability and appropriateness (from clinician surveys) and clinical outcomes will be summarized using descriptive statistics. Sensitivity analyses will be performed to assess the effect of repeat clinician participants. All data elements will be described using frequencies for categorical variables and median with interquartile ranges for continuous variables.

Monitoring

Data monitoring, harms, auditing

Barriers to implementation will be identified and addressed during the training phase and following field testing of the CMOT. An interim analysis of recruitment rate, protocol adherence, and early indicators of acceptability and appropriateness will be conducted following enrollment of the first six patients and the clinicians caring for them. The data and safety monitoring committee will monitor protocol compliance and report all violations to the institutional review board (IRB) within 3 working days of identification. There are few adverse events anticipated for this low-risk study. The risk of loss of confidentiality among patients and clinicians will be mitigated by assigning unique study identification numbers, and not collecting any protected health information, while entering study data into a secure REDCap database accessible only to assigned research staff. Unintended effects such as additional stress, anxiety, or grief from clinician participants will be shared with ICU leadership and reported as part of the data safety monitoring plan. Monitoring will occur monthly by review of the enrollment process, results, and participant feedback. The study will be stopped for any serious adverse event affecting participants.

Discussion

This protocol will test the feasibility of the CMOT—a structured time-out and checklist intervention for WMV in the ICU—for a future randomized control trial. The study will inform potential changes to the protocol and intervention for future trials. The CMOT is grounded in a quality and safety framework already adopted in procedural and critical care settings [28–31]. Given high rates of distress, the CMOT will fill an identified gap in evidence surrounding the process of WMV. The CMOT builds upon existing approaches to WMV, including a recently completed effectiveness trial of a nurse-driven algorithm with results indicating reductions in rate of patient distress [36].

The CMOT complements and extends existing evidence [36] by testing a multidisciplinary team-based “time-out” for management of key steps in the complex process of WMV at end of life. Facilitating an open, supportive environment that empowers and supports members of the ICU team (specifically the ICU nurse) is central to the intervention. Published guidelines [49, 50] lack detail in key steps for the process of WMV. The CMOT was informed by a detailed prospective observational study of WMV, OBSERVE-WMV, which identified patient risk factors for distress and modifiable care processes associated with fewer distressful episodes.

The design of the CMOT study addresses risk factor identification in patients undergoing WMV and process improvements in the following ways. First, key elements composing the CMOT were supported by results from a recently completed RCT of an algorithmic approach to WMV [36] and high-quality evidence [51–53] guiding use of opiates for pain and dyspnea relief. Substantial evidence gaps remain [6], and evidence guiding the exact timing of administration (e.g., opiate delivered in anticipation of distress) remains limited. Because the optimal approach to WMV has not been clearly established [17], the CMOT serves as a guide for discussion and planning of optimal patient management, and the final clinical decision remains with treating ICU clinicians. The second major study design consideration included field testing, and a pause following enrollment of the first six patients to support preliminary analysis, refinement of the CMOT, and iterative feedback from a broad multidisciplinary panel of experts culminating in the intervention to be tested among clinicians caring for 40 patients. Once proven feasible as a delivery tool for improving WMV care, we anticipate the need for further testing of different elements within the CMOT itself in geographically diverse ICUs.

Timing the delivery of the intervention presented a significant challenge in the design of the trial. While 60 min before WMV was chosen, a longer time window before may allow for broader participation among all members of the ICU team. Conducting the time-out and checklist intervention immediately before extubation assures closer adherence to the plan set forth by the ICU team. Surgical procedural time-outs are performed immediately before planned procedures [27, 54]. Whether the WMV process will be improved by closely emulating surgical time-outs or through a staged approach tailored to the complexities of the WMV process remains to be fully explored. The only other study of an algorithmic approach to WMV calls for frequent monitoring as directed by the nurse [36]. Involvement of the multidisciplinary team, as set forth in the CMOT, may be most effective with temporary orders being placed at time of the decision for comfort focused care, and a second step “time out” process to confirm all supplies and key personnel are available may be performed immediately prior to extubation.

Clinician perspectives will be ascertained from the CMOT Clinician Survey to define barriers to implementation. A large multi-center observational study in France [17] found that terminal weaning was more burdensome for clinicians, but this trial was not designed to test a multidisciplinary tool. Based on data obtained from the clinician survey, future versions of the CMOT will aim to improve acceptability and ease of use among clinicians. The overarching goal of the CMOT is to reduce patient distress and better support clinicians through WMV. Patient-level data are being collected from this feasibility study to establish a trend toward fewer episodes of distress among patients undergoing WMV. Results from this analysis will inform sample size and power calculations required for the design of future RCTs to test intervention efficacy in reducing patient distress. Future studies will use patient data from OBSERVE-WMV as a comparator.

This study has several potential limitations. First, the practice of end-of-life care varies in ICUs at different hospitals, which may limit the generalizability of the application of this study design. Second, participants will not be blinded to the intervention, and without control ICUs, participant’s knowledge may bias results toward finding the intervention feasible. Lastly, given differences in approach and timing of intervention development, we were unable to completely integrate all elements of the nurse-driven algorithm shown to be beneficial in reducing distress [36]. The intervention intentionally targeted the multidisciplinary ICU team to provide support and critical decision making. Future studies may benefit from the CMOT or similar intervention as a trigger for supporting the use of nurse-driven protocols. Based on recent qualitative evidence the care of the ICU patient at end of life may best occur with a collaborative and supportive environment for nurse at the bedside [19].

Conclusions

A full description of the design of this pilot trial of the feasibility of the CMOT intervention will support expected future refinements to the intervention. Key design considerations include incorporating clear prescriptive language with improvement in the quality of evidence guiding key steps in WMV. Future cluster randomized trials will test optimal approaches to intervention delivery to support a common clinical scenario at end of life in the ICU with urgent need for innovation.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1: CONSORT checklist.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2: List of Advisors.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3: Clinician Survey.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joanna Anderson, RN for her support in intervention development.

Abbreviations

- APP

Advanced practice provider

- CPOT

Clinical pain observation tool

- CMO

Comfort measures only

- CMOT

Comfort Measures Only Time out

- CAM

Confusion assessment method-ICU

- EHR

Electronic health record

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- IRB

Institutional review board

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- OBSERVE-WMV

Observational study of withdrawal of mechanical ventilation

- RCT

Randomized control trial

- RN

Registered nurse

- RA

Research assistant

- RDOS

Respiratory Distress Observation Score

- RT

Respiratory therapist

- SAPS

IISimplified Acute Physiology Score

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

- WMV

Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation

Authors’ contributions

CRF conceived of the study and is the grant holder. All authors were involved with the intervention and protocol development. AGF helped implement the protocol and write the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIA K23AG066929, Dr. Fehnel, NINR R01NR015768, Dr. Campbell; NHLBI K24HL148314, Dr. White; NIA U54AG063546, Dr. Mitchell).

Data availability

The results of this study will be shared with the clinician participants, presented at scientific meetings, and publicly available at PubMed Central. Data from the study will be de-identified and not traceable to individual participants.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations (CCI/IRB) approved this study (#2023P000160) and will review any protocol changes. The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05861323) and with the National Institute on Aging CROMS database (DGCG-10874). Participants will be assigned a unique identifier to protect confidentiality. All study databases will be de-identified and archived at the end of the study. All data are encrypted and stored in secure, password protected research virtual environment accessible only to approved study staff.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fulton AT, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Intensive care utilization among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive and severe functional impairment. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Johnson-Hurzeler R, et al. End-of-life care intensity and hospice use. Med Care. 2016;54:672–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aslakson RA, Reinke LF, Cox C, Kross EK, Benzo RP, Curtis JR. Developing a research agenda for integrating palliative care into critical care and pulmonary practice to improve patient and family outcomes. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:329–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzu MA, Campbell ML, Schwartzstein RM, White DB, Mitchell SL, Fehnel CR. Evidence guiding withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at the end of life: a review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;66:e399–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epker JL, Bakker J, Lingsma HF, Kompanje EJO. An observational study on a protocol for withdrawal of life-sustaining measures on two non-academic intensive care units in the netherlands: few signs of distress, no suffering? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:676–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Mahoney S, McHugh M, Zallman L, Selwyn P. Ventilator withdrawal: procedures and outcomes. Report of a collaboration between a critical care division and a palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;26:954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Aiyagari V, Hollingsworth H. Factors associated with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a neurology/neurosurgery intensive care unit. 2001;29:1792–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouyang DJ, Lief L, Russell D, Xu J, Berlin DA, Gentzler E, et al. Timing is everything: early do-not-resuscitate orders in the intensive care unit and patient outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0227971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas CE, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Beinum A, Hornby L, Ward R, Ramsay T, Dhanani S. Variations in the operational process of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:e450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell ML. Dyspnea prevalence, trajectories, and measurement in critical care and at life’s end. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:168–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puntillo K, Nelson JE, Weissman D, Curtis R, Weiss S, Frontera J, et al. Palliative care in the ICU: relief of pain, dyspnea, and thirst-a report from the IPAL-ICU Advisory Board. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:235–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehnel CR, de la Hoz MA, Celi LA, Campbell ML, Hanafy K, Nozari A, et al. Incidence and risk model development for severe tachypnea following terminal extubation. Chest. 2020;158:1456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Wibisono AH, Allen KA, Yaghoobzadeh A, Bit-Lian Y. Exploring the experiences of nurses’ moral distress in long-term care of older adults: a phenomenological study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert R, Le Gouge A, Kentish-Barnes N, Cottereau A, Giraudeau B, Adda M, et al. Terminal weaning or immediate extubation for withdrawing mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients (the ARREVE observational study). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell ML, Yarandi HN, Mendez M. A two-group trial of a terminal ventilator withdrawal algorithm: pilot testing. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:781–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryan AF, Reich AJ, Norton AC, Campbell ML, Schwartzstein RM, Cooper Z, et al. Process of withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at end of life in the ICU. CHEST Critical Care. 2024;2:100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):147–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abarshi EA, Papavasiliou ES, Preston N, Brown J, Payne S. The complexity of nurses’ attitudes and practice of sedation at the end of life: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:915–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brinkkemper T, Van Norel AM, Szadek KM, Loer SA, Zuurmond WWA, Perez RSGM. The use of observational scales to monitor symptom control and depth of sedation in patients requiring palliative sedation: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;27:54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer S, Kossoff SB. Withdrawal of life support in the neurological intensive care unit. Neurology. 1999;52:1602–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papavasiliou ES, Brearley SG, Seymour JE, Brown J, Payne SA. From sedation to continuous sedation until death: how has the conceptual basis of sedation in end-of-life care changed over time? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:691–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paruk F, Kissoon N, Hartog CS, Feldman C, Hodgson ER, Lipman J, et al. The Durban World Congress Ethics Round Table Conference Report: III. Withdrawing mechanical ventilation—the approach should be individualized. J Crit Care. 2014;29:902–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, Syin D, Goodrich E, Hartmann E, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B, Reznick R, Baker GR, Doran D, Espin S, Bohnen J, Whyte S. Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Arch Surg. 2008;143:12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tainter CR, Nguyen AP, Pollock KA, O’Brien EO, Lee J, Schmidt U, et al. The impact of a daily “medication time out” in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2018;43:366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrnes MC, Schuerer DJE, Schallom ME, Sona CS, Mazuski JE, Taylor BE, et al. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gozu A, Clay C, Yonus F. Hospital-wide reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections: a tale of two small community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:619–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall R, Rocker G, Murray D. Simple changes can improve conduct of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:902–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matone E, Verosky D, Siedsma M, O’Kane EN, Ren D, Harlan MD, et al. A comfort measures only checklist for critical care providers: impact on satisfaction and symptom management. Clin Nurse Spec. 2021;35:303–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med. 1995;14:1933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teare MD, Dimairo M, Shephard N, Hayman A, Whitehead A, Walters SJ. Sample size requirements to estimate key design parameters from external pilot randomised controlled trials: a simulation study. Trials. 2014;15:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell ML, Yarandi HN. Effectiveness of an algorithmic approach to ventilator withdrawal at the end of life: a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2024;27(2):185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gift A, Narsavage G. Validity of the numeric rating scale as a measure of dyspnea. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:200–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, et al. An official American thoracic society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am Journal Resp Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4):435–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell ML, Templin T, Walch J. A respiratory distress observation scale for patients unable to self-report dyspnea. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price D, Harkins S. Combined use of experimental pain and visual analogue scales in providing standardized measurement of clinical pain. Clin J Pain. 1987;3:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:420–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. The Lancet. 1974;304:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson N, Esteban A. Risk factors for extubation failure in patients following a successful spontaneous breathing trial. Chest. 2006;130:1664–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salam A, Tilluckdharry L, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Neurologic status, cough, secretions and extubation outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;21:2703–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AHS, Dellinger EP, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Downar J, Delaney JW, Hawryluck L, Kenny L. Guidelines for the withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1003–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banzett RB, Adams L, O’Donnell CR, Gilman SA, Lansing RW, Schwartzstein RM. Using laboratory models to test treatment morphine reduces dyspnea and hypercapnic ventilatory response. Am Journal of Resp and Crit Care Med. 2011;184:920–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Decavele M, Bureau C, Campion S, Nierat MC, Rivals I, Wattiez N, et al. Interventions relieving dyspnea in intubated patients show responsiveness of the mechanical ventilation-respiratory distress observation scale. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clemens KE, Klaschik E. Symptomatic therapy of dyspnea with strong opioids and its effect on ventilation in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:473–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cist A, Truog R, Brackett S, Hurford W. Practical guidelines on the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2001;39:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Appendix 1: CONSORT checklist.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2: List of Advisors.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3: Clinician Survey.

Data Availability Statement

The results of this study will be shared with the clinician participants, presented at scientific meetings, and publicly available at PubMed Central. Data from the study will be de-identified and not traceable to individual participants.