Abstract

1,4-Naphthoquinone is a promising pharmacophore in drug discovery due to its unique redox reactive nature and wide-ranging bioactivities. Herein, a series of 1,4-naphthoquinones (1-14) were investigated for their anticancer activities against 4 cancer cell lines (i.e., HepG2, HuCCA-1, A549, and MOLT-3). Compound 11 was found to be the most potent and selective anticancer agent against all tested cell lines (IC50 = 0.15 – 1.55 μM, selectivity index = 4.14 – 43.57). QSAR modelling was performed to elucidate key structural features influencing activities against four cancer cell lines. Four QSAR models were successfully constructed using multiple linear regression (MLR) algorithm providing good predictive performance (R: training set = 0.8928–0.9664; testing set = 0.7824–0.9157; RMSE: training set = 0.1755–0.2600; testing set = 0.2726–0.3748). QSAR models suggested that the potent anticancer activities of these naphthoquinones were mainly influenced by polarizability (MATS3p and BELp8), van der Waals volume (GATS5v, GATS6v, and Mor16v), mass (G1m), electronegativity (E1e), and dipole moment (Dipole and EEig15d) as well as ring complexity (RCI) and shape of the compound (SHP2). The models were further applied for guiding the design and predicting activities of an additional set of 248 structurally modified compounds in which the ones with promising predicted activities were highlighted for potential further development. Additionally, pharmacokinetic profiles and possible binding modes towards potential biological targets of the compounds were virtually assessed. Structure-activity relationship analysis was also conducted to highlight key structural features beneficial for further successful design of the related naphthoquinones.

Keywords: Naphthoquinone, Anticancer, QSAR, ADMET, Computer-aided drug design

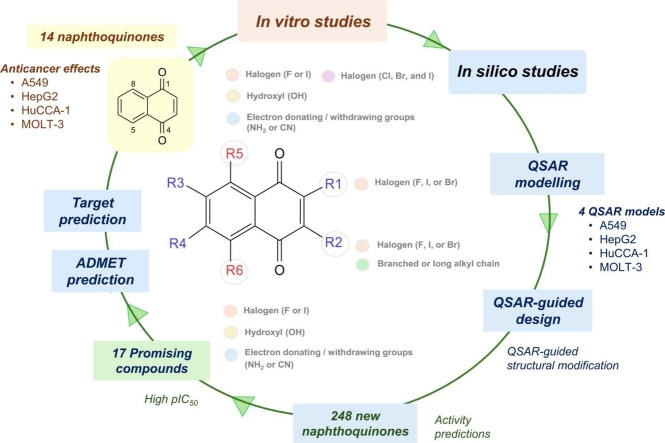

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Naphthoquinones (1-14) showed anticancer activities against four cancer cell lines.

-

•

Four Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models were constructed.

-

•

QSAR models guided rational design and activity predictions of new 248 compounds.

-

•

Key structural features governing potent activities were highlighted.

-

•

Pharmacokinetics profiles and potential targets of the compounds were predicted.

1. Introduction

Cancers are one of main leading causes of death and burden of diseases worldwide [1], [2]. Despite of many clinical available chemotherapeutics, the management of cancers is still challenging due to drug-induced toxicities, undesirable side effects, and drug resistance [3], [4]. These global health situations have driven the discovery of novel anticancer agents an urgent needs [5].

Naphthoquinones (NQs) are highly reactive molecules with prooxidant nature, which making them capable of modulating redox balance and regulating redox-related signaling pathways in the biological system [6]. NQs have been highlighted for several therapeutic potentials including anticancer, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activities [7]. Among others, 1,4-NQ derivatives have drawn great attention as promising candidates for anticancer therapeutics [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14] due to their multiple cytotoxic actions (i.e., inhibit DNA topoisomerases, generate free radicals, induce apoptosis, and regulate tumor suppressing factors)[15]. The promising anticancer potential of the 1,4-NQ pharmacophore is also highlighted by its molecular presence in doxorubicin and approved anticancer drugs [8]. However, the doxorubicin performed clinical concerning points including considerable cardiotoxicity as well as drug resistance [16], [17]. Accordingly, the design of novel 1,4-NQ analogs with improved anticancer efficacy and minimized toxicities could pave the way to overcome these limitations.

Drug development is a complex and costly process that requires multidisciplinary expertise. However, the process is well-recognized for its challenging high failure rate [18], [19] which is not only caused by the unfavorable clinical efficacy, but also by poor pharmacokinetic properties and undesirable toxicities [19]. Particularly, the failures mostly occur in the late stages of the pipeline, leading to considerable financial loss [19]. To improve success rate and save time, computational approaches have been employed as facilitating tools in current drug design, particularly, the ones that provide key knowledge for further effective screening, design, and structural optimization [20], [21]. An in silico prediction of drug-like properties and pharmacokinetic profiles in early stages of development is also highly encouraged to avoid the late stage failures [22].

Structural modification is a key strategy in drug design for enhancing drug-likeness and potency [23], [24] and understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) is one of the key factors for efficacious design and structural optimization of the lead compounds [25]. Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modelling is a well-known machine learning-based computational method for revealing key structural features and properties influencing activities of the compounds [26]. Successful story of applying the QSAR modelling for guiding the rational design of several types of bioactive compounds including the anticancer, neuroprotective, and antioxidant agents was demonstrated by our research group [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Although, some previous studies reported QSAR models for predicting anticancer activities of the 1,4-naphthoquinones [34], [35], [36], the studies demonstrating the applications of QSAR modelling for guiding the design of 1,4-naphthoquinone-based anticancer agents are still limited.

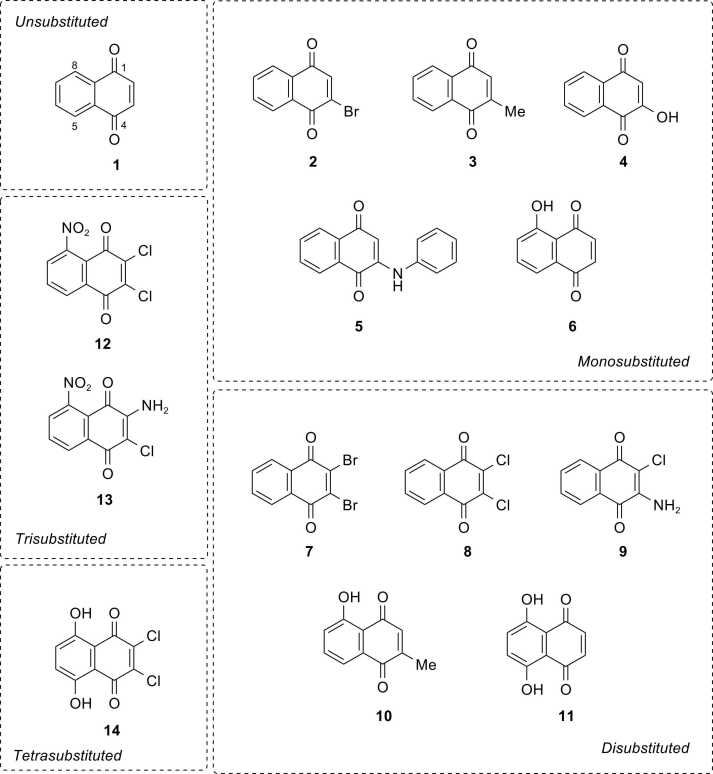

The current study demonstrates the integral use of experimental and computational approaches for facilitating rational design of NQ-based compounds for anticancer therapeutics. A series of fourteen NQ derivatives (1-14, Fig. 1), bearing mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra- substitutions on the NQ core, were investigated for their anticancer activities against 4 cancer cell lines using MTT assay. QSAR modelling was performed to construct four predictive models and further applied for guiding the design and predicting activities of an additional set of structurally modified NQ-based compounds. Drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, toxicity profiles, and potential biological targets of the selected compounds were also explored using in silico web-based tools. Additionally, structure-activity relationship analysis was conducted to reveal crucial structural key findings beneficial for further design and development of the NQ-based compounds as anticancer agents.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of naphthoquinone derivatives (1-14).

2. Materials and methods

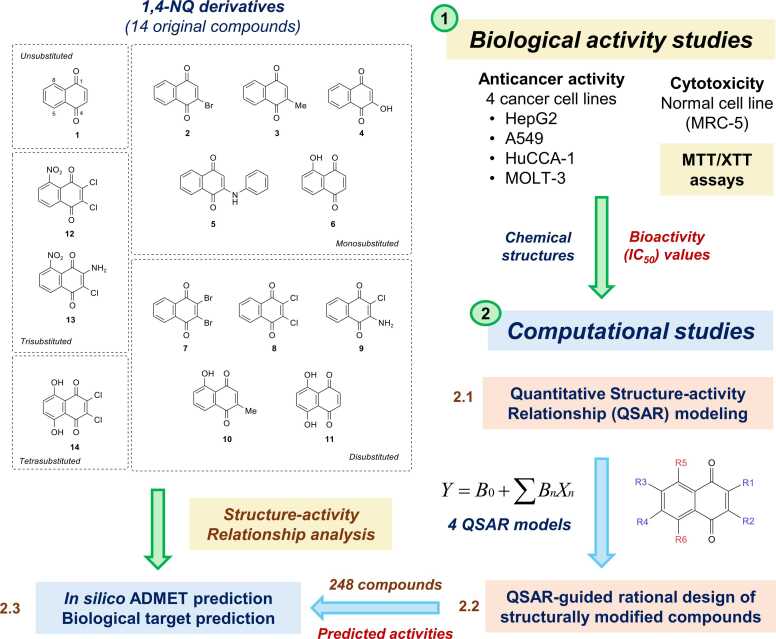

A set of fourteen commercially available 1,4-NQ derivatives (Fig. 1) were purchased and investigated for their cytotoxic activities against four cancer cell lines (i.e., hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2, ATCC: HB-8065), cholangiocarcinoma cancer (HuCCA-1), lung carcinoma (A549, ATCC: CCL-185), and T-lymphoblast acute lymphoblastic leukemia (MOLT-3, ATCC: CRL-1552) cell lines as well as a normal cell line (i.e., MRC-5: CCL-171, fetal lung fibroblast). The ATCC cell lines (HepG2, A549, MOLT-3, and MRC-5) were purchased from Biomedia Thailand, while the HuCCA-1 was received as a gift from the Immunology laboratory, Siriraj Hospital. Bioactivity values of the studied compounds (1-14) obtained from experimental assay along with their chemical structures were used to prepare datasets for QSAR modelling. The constructed models were further employed to guide the rational design and predict activities of an additional set of 248 structurally modified NQ-based compounds. Additionally, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and toxicity profiles as well as potential biological targets of the selected compounds were predicted using in silico web-based tools. Overview workflow of the study is provided in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overview workflow of the study. 1: A set of 14 original NQ derivatives were experimentally investigated for their cytotoxic effects. 2: Chemical structures of original compounds along with experimental IC50 values were used for preparing dataset for QSAR modelling. 2.1: QSAR modelling was performed using multiple linear regression (MLR) algorithm to obtain 4 QSAR models. 2.2: The constructed models were used for guiding design and predicting activities of an additional set of 248 structurally modified compounds. 2.3: A set of promising newly designed compounds with good predicted activities and original compounds were investigated for their ADMET properties and potential biological targets. Structure-activity relationships were analyzed to highlight key structural features required for potent activities.

3. Cytotoxic assay

A set of fourteen 1,4-NQ derivatives (1-14, Fig. 1) were evaluated for their cytotoxic effects against 4 types of human cancer cell lines (i.e., hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2, passage cell number 20–23), cholangiocarcinoma cancer (HuCCA-1, passage cell number 115–121), lung carcinoma (A549, passage cell number 20–26), and T-lymphoblast acute lymphoblastic leukemia (MOLT-3, passage cell number 15–25) cell lines) as well as normal fetal lung fibroblast (MRC-5, passage cell number 19–23). Two reference drugs (doxorubicin and etoposide) were used as positive control and DMSO was used as negative control. A549 and HuCCA-1 cell lines were grown in Hamm’s F12 containing 2 mM L-glutamine supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 10 % FBS. MOLT-3 cell line was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, glucose and 10 % FBS. HepG2 and MRC-5 cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium containing 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 10 % FBS.

Cell lines suspended in RPMI-1640 containing 10 % FBS were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 – 2 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate (Costar No.3599, USA) and then incubated at 37C under a humidified atmosphere with 95 % air and 5 % CO2 for 24 h. DMSO was used as a solvent to dissolve tested compounds and reference drugs. An equivalent volume of additional medium containing either the serial dilutions of the tested compounds, positive control (etoposide and/or doxorubicin) or negative control (DMSO) was added to obtain the desired final concentrations. The prepared microtiter plates were further incubated for 48 h. MTT assay was conducted to determine cell viability of adherent cells (i.e., A549, HuCCA-1, HepG2, and MRC-5 cells) [37], [38], whereas the XTT assay was performed for the suspended MOLT-3 cells [39]. The plates were read on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) and the absorbance was recorded at 550 nm. The IC50 values were determined as a concentration of the tested compounds or drugs required to afforded 50 % inhibition of cell growth. The compounds exhibiting IC50 value greater than 50 μg/mL were denoted as non-cytotoxic [33].

4. QSAR study

4.1. Datasets

Four anticancer QSAR models were separately constructed based on four types of cancer cell lines. The datasets were prepared using descriptor values (obtained from chemical structures) and bioactivity values (obtained from experimental results). Only active compounds were included in the dataset, while the inactive ones were excluded. Bioactivity values (experimentally obtained IC50 values) of active compounds were normalized by taking the negative logarithm to the base of 10 (-log IC50) into pIC50 values (Table S2). Descriptor values were obtained from structural optimization and calculation (as described below).

4.2. Molecular structure optimization and descriptor calculation

Chemical structures of compounds (1-14) were drawn using the GaussView 03 software [40]. The detailed parameters and methods for geometrical optimization were set as follows: 1) optimization use tight convergence was selected for job type, 2) semi-empirical Austin Model 1 (AM1) level or density functional theory (DFT) calculation using LANL2DZ level was selected for method, 3) ignore symmetry was selected for general option, and 4) save orbitals to checkpoint file was set for guess option. The geometrical optimization was then performed by Gaussian 09 [41] at the semi-empirical AM1 level followed by DFT calculation using LANL2DZ level to obtain the low-energy conformers to be used as input files for further processes (i.e., extraction of quantum chemical descriptor and calculation of molecular descriptors). A set of 13 quantum chemical descriptors (including mean absolute atomic charge (Qm), total energy (Etotal), total dipole moment (μ), highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), energy difference of HOMO and LUMO (HOMO-LUMOGap), electron affinify (EA), ionization potential (IP), Mulliken electronegativity (χ), hardness (η), softness (S), electrophilic index (ωi) and electrophilicity (ω)) was extracted from the optimized chemical structures (.out files) using the in-house developed script. The optimized structures were converted from.out format into.mol files to be used as input files for further molecular descriptor calculation using Dragon software (version 5.5)[42]. Both 2D and 3D descriptors were included in the calculation and all calculated parameters were set as default. The calculation was run to finally obtain a total set of 3224 molecular descriptors including 22 classes (i.e., Constitutional descriptors, Topological descriptors, Walk and path counts, Connectivity indices, Information indices, 2D autocorrelation, Edge adjacency indices, Burden eigenvalues, Topological charge indices, Eigenvalue-based indices, Randic molecular profiles, Geometrical descriptors, RDF descriptors, 3D-MoRSE descriptors, WHIM descriptors, GETAWAY descriptors, Functional group counts, Atom-centred fragments, Charge descriptors, Molecular properties, 2D binary fingerprints and 2D frequency fingerprints). Finally, a total set of calculated 3237 descriptor variables (i.e., 13 quantum chemical descriptors and 3224 molecular descriptors) was subjected to a feature selection process.

4.3. Feature selection

Feature selection is a process to filter a set of informative descriptors to be used as final predictors (independent variable: X) for QSAR model construction. Initially, correlation-based feature selection was performed to prioritize a set of descriptors that are highly correlated with bioactivity. Pearson’s pair-correlation values (r) were calculated for each pair of descriptor variable and bioactivity (pIC50 values). The descriptor variables displaying calculated |r| ≥ 0.6 were initially selected, while those with calculated |r| < 0.6 were filtered out. The initially selected descriptors were subjected to further selection process using attribute selection (CfsSubsetEval, Best First) as implemented in Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA) version 3.4.5 [43]. Multicollinearity is a phenomenon in which the predictors (descriptors) used to build the model are closely correlated leading to model overfitting and poor generalizability. To ensure that all predictors are independent, the pair-correlation values (r) between each pair of the selected descriptors were calculated to observe collinearity. For each pair of descriptors whose |r| ≥ 0.6 was considered highly correlated and one of them can be removed. Finally, a total set of informative descriptor variables was obtained for QSAR model construction. Their definitions and values are provided in Table 2 and Table S3, respectively.

Table 2.

Definitions of selected descriptors for QSAR modelling.

| Model | Descriptor | Definition | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| HuCCA−1 | MATS3p | Moran autocorrelation of lag 3 weighted by polarizability | 2D autocorrelations |

| Dipole | A separation of opposite electrical charges quantified by its dipole moment (μ). | Quantum chemical descriptor | |

| GATS5v | Geary autocorrelation of lag 5 weighted by van der Waals volume | 2D autocorrelations | |

| GATS6v | Geary autocorrelation of lag 6 weighted by van der Waals volume | 2D autocorrelations | |

| RCI | ring complexity index | Ring descriptors | |

| A549 | EEig15d | Eigenvalue 15 from edge adj. matrix weighted by dipole moments | Edge adjacency indices |

| Mor15u | signal 15 / unweighted | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | |

| E2u | 2nd component accessibility directional WHIM index / unweighted | WHIM descriptors | |

| G1m | 1st component symmetry directional WHIM index / weighted by mass | WHIM descriptors | |

| HepG2 | Mor16v | signal 16 / weighted by van der Waals volume | 3D-MoRSE descriptors |

| E2u | 2nd component accessibility directional WHIM index / unweighted | WHIM descriptors | |

| R5u | R autocorrelation of lag 5 / unweighted | GETAWAY descriptors | |

| MOLT−3 | BELp8 | lowest eigenvalue n. 8 of Burden matrix / weighted by atomic polarizabilities | BCUT descriptors |

| SHP2 | average shape profile index of order 2 | Randic molecular profiles | |

| E1e | 1st component accessibility directional WHIM index / weighted by Sanderson electronegativity | WHIM descriptors | |

| Du | D total accessibility index / unweighted | WHIM descriptors |

4.4. QSAR model construction

Multivariate analysis using multiple linear regression (MLR) algorithm was performed by Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA) version 3.4.5 [43]. The models were constructed using the final datasets containing selected descriptor (assigned as independent variables: X) and pIC50 (assigned as dependent variables: Y) values as the input files. The MLR models were built according to the following equation.

| (1) |

where Y is the pIC50 values of compounds, B0 is the intercept and Bn are the regression coefficient of descriptors Xn.

4.5. Data sampling

Leave-one-out cross-validation was used for data sampling. The dataset was separated into two sets (i.e., training set and testing set). For each round, one sample was excluded from the whole dataset (N) to remain as a training set (N-1) in which the model was trained and constructed to predict activity (Y values) of a leaving sample in the testing set. The same process continued until every sample in the dataset was chosen to be used as testing sets.

4.6. Evaluating the performance of QSAR models

Predictive performance and predictive error of the built models were assessed using two parameters including correlation coefficient (R) and the root mean square error (RMSE), respectively.

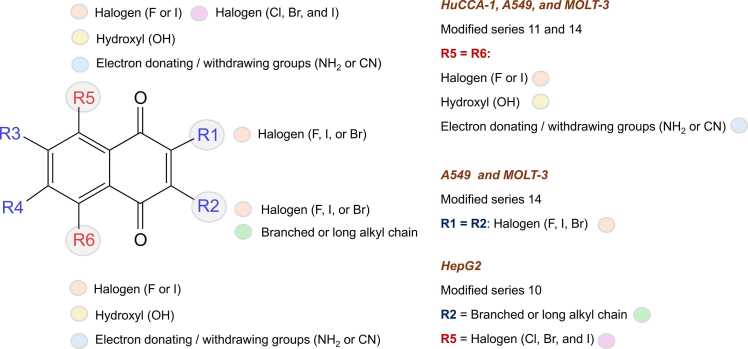

4.7. Application of QSAR models for guiding design of modified compounds

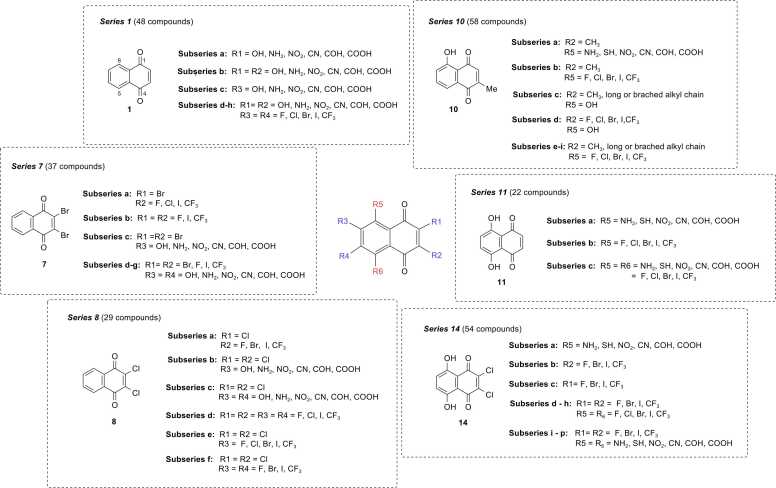

Six original compounds (1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14) with promising activities were selected as prototypes for the rational design. Key descriptors presented in the QSAR models were used for guiding the structural modifications on the core of prototypes by substitutions of various types of moieties. Modification strategies are depicted in Fig. 3. Finally, a total set of 248 newly designed compounds were obtained (i.e., series 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14). Chemical structures of the newly designed compounds were drawn, optimized, and calculated to obtain values of key descriptors in the same manner as the original compounds. The obtained values of key descriptors were collected for further predicting the activities (expressed as predicted pIC50 values) of newly designed compounds using the constructed QSAR models.

Fig. 3.

Modification strategies for rational design of additional 248 compounds.

5. Predictions of drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles

Chemical structures of the studied compounds in SMILEs format were used as input files for prediction using web-based tool ADMETlab 3.0 (https://admetlab3.scbdd.com)[44].

6. Predictions of potential biological targets

Chemical structures of the studied compounds in SMILEs format were used as input files for prediction using SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch)[45]. Subsequently, three target proteins with the highest predicted values (i.e., histone acetyltransferase p300 (EP300), dual specificity phosphatase Cdc25B (CDC25B), and carbonic anhydrase II (CA2)) were selected for molecular docking simulations to initially confirm the binding possibilities of the investigated compounds (10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3). Crystal structures of human EP300 co-crystallized with 6TF inhibitor (PDB ID: 5KJ2), human CDC25B co-crystallized with 3M8 inhibitor (PDB ID: 4WH9), and human carbonic anhydrase II co-crystallized with 9EB inhibitor (PDB ID: 5NY6) were retrieved from the RSCB protein data bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). Co-crystallized ligands were removed, and the protein structures were prepared by adding essential hydrogen atoms and repairing missing side chains using DockThor [46]. Then, non-polar hydrogen atoms were merged, Gasteiger atomic charges were assigned, and atom types of the protein structures were specified using AutoDock Tools version 1.5.6. [47], [48]. Geometrically optimized structures of the investigated ligands (10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3) were obtained from the process previously mentioned in the QSAR section and were prepared by assigning partial atomic charge, defining rotatable bonds, and merging non-polar hydrogen atoms using AutoDock Tools version 1.5.6 [47], [48]. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina, as a part of PyRx 0.8 software [49]. The grid boxes were generated (size: EP300 and CDC25B = 25 × 25 × 25 A°, CA2 = 25 × 14.85 × 17.40 A°) and allocated at the center of the binding cavity of the targets (x, y, and z coordinates: EP300 = 36.51, 9.03, and 181.70, CDC25B = 15.70, −7.723, −3.67, and CA2 = −3.63, 3.86, 13.38, respectively). Docking protocols were initially validated by redocking the co-crystallized ligands (6TF, 3M8, and 9EB) to ensure the reliability of simulations. The distance between the original pose and the redocked pose was used to calculate the root mean squared deviation (RMSD) values using Discovery Studio Visualization version 16.1.0.15350 [50]). The validated docking protocols (providing acceptable RMSD values less than 2 A°) were further used to explore the binding modes of the studied naphthoquinones (EP300: redocked 6TF-5KJ2 = 0.343 ºA, CDC25B: redocked 3M8–4WH9 = 0.335, and CA2: redocked 9EB-5NY6 = 0.462). The docking poses were visualized and illustrated using UCSF Chimera software [51], and 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams were created using Discovery Studio Visualization version 16.1.0.15350 [50].

7. Results and discussion

7.1. Anticancer activities and cytotoxicity

Fourteen NQs (1-14) were investigated for their cytotoxic effects against four cancer cell lines (i.e., HepG2, HuCCA-1, A549, and MOLT-3) using MTT and XTT assays. Most of the tested compounds exhibited broad-ranged anticancer effects against four tested cell lines, except for compounds 4, 5, and 12 (Table 1). Compound 11 displayed the most promising activities against all tested cell lines providing the lowest IC50 values (IC50: 0.15 – 1.55 µM), followed by compounds 14 (IC50: 0.27 – 14.67 µM) and 10 (IC50: 1.38 – 13.60 µM), respectively. However, these top three compounds exhibited less potency than the reference drugs doxorubicin (IC50: HuCCA-1 = 0.86, A549 = 0.31, HepG2 = 0.46 µM) and etoposide (IC50: MOLT-3 = 0.06 µM). Conversely, compounds 4 and 12 were noted to be the least potent compounds as shown by their high IC50 values (4: 248.00–275.85 µM, and 12: 79.88–122.56 µM), Table 1. Additionally, MOLT-3 cell line is noted to be the most sensitive cell for these set of NQ derivatives as indicated by the lowest IC50 value range (IC50: 0.15 – 79.88 µM) comparing to those observed for the other cell lines. Notably, 2,3-dihalo (X) NQ 7 (X = Br, IC50 = 3.29 µM) and 8 (X = Cl, IC50 = 3.61 µM) displayed improved activities compared to the unsubstituted NQ 1 (IC50 = 5.12 µM). This could be due to the suitable size and lipophilicity (Br and Cl) of the molecule to reach and interact with the target site of action. Moreover, the substitution of the 2,3-dichloro NQ 8 with 5,8-diOH group achieved a symmetrical molecule 14 (IC50 = 0.27 µM) with highly improved activity. This might result from the property of electron withdrawing (Cl) and electron donating (OH) effects providing the molecule with optimum size and electronic effects for interacting with the target site requiring lipophilic and H-bonding properties. On the other hand, the substitution of 2,3-diCl NQ (8) with 8-NO2 group gave the least potent compound 12 (IC50 = 79.88 µM). This could possibly be due to an ionic character of the NO2 group which is inappropriate for the target site interaction. The findings suggested that the NQ core structure substituted with di-halogen (Cl and Br) and di-OH groups may provide the compounds with symmetrical ring size or shape for interacting with their anticancer targets.

Table 1.

Cytotoxic activities of NQ derivatives (1-14) against 4 cancer cell lines (IC50, µM).

|

IC50 is the concentration of compound required to produce 50 % of inhibitory effect.

ND = not determined, NC = compound is considered inactive (% inhibition less than 50 % at 50 μg/mL).

Cancer cell lines comprise the following: HuCCA-1 cholangiocarcinoma cancer cell line, A549 lung carcinoma cell line, HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, and MOLT-3 lymphoblastic leukemia cell line.

Etoposide and doxorubicin were used as reference drugs.

The most potent, second most potent, and third most potent compounds against each cancer cell line are highlighted in blue, grey, and yellow, respectively.

Three compounds bearing OH group (i.e. 10, 11, and 14) were ranked as top three most promising compounds (i.e., HuCCA-1 and MOLT-3: 11 > 14 > 10; A549 and HepG2: 11 > 10 > 14), Fig. 1. Additionally, the cytotoxic effects against all cancer cell lines were notably improved when the di-OH groups were substituted on the 5- and 8- positions of compound 8 (IC50: 3.61 – 110.29 µM) to give compound 14 (IC50: 0.27 – 14.67 µM), Table 1. This suggested that the presence of di-OH groups at 5,8-position on the NQ core is essential for potent activities against four cancer cell lines.

The investigations on cytotoxicity of the compounds (1-14) against normal MRC-5 cell line showed cytotoxic effects with IC50 values range of 5.00 – 118.20 µM (Table S1). However, most of them displayed the lesser toxicity to the normal cell when compared to reference drugs (i.e., doxorubicin IC50 = 0.93 µM and etoposide IC50 = 13.35 µM). Selectivity index (SI) of the investigated compounds was also calculated showing that the most potent compound 11 displayed higher SI values against all tested cell lines (SI value range = 4.14–43.57, Table S1). Compound 11 showed better selectivity against three cancer cell lines (i.e., HuCCA-1, A549, and HepG2) when compared to doxorubicin (SI values HuCCA-1: 11 = 4.14, doxorubicin = 1.08; SI values A549: 11 = 4.52, doxorubicin = 3.02; and SI values HepG2: 11 = 4.69, doxorubicin = 2.02, Table S1). This suggested that compound 11 exhibited superior selectivity than the conventional drug, doxorubicin, and could be potentially further developed as a safer anticancer drug. Compound 11 also displayed the best selectivity towards MOLT-3, affording the highest SI value. However, this compound displayed lower selectivity against the MOLT-3 cell line when compared to that of the etoposide (SI values MOLT-3: 11 = 43.57, etoposide = 218.85, Table S1).

8. QSAR modelling

QSAR modelling is one of effective in silico tools used to facilitate successful drug design and discovery [52]. It is well-known for revealing the key chemical properties (represented by descriptor variables, X) influencing bioactivity (represented by pIC50 values, Y) of the compounds. Multiple linear regression (MLR) is an algorithm popularly used in drug design due to its interpretable characteristics which is beneficial for guiding the efficacious design of new compounds [53]. Herein, four QSAR models were constructed according to experimentally obtained activities against four cancer cell lines using MLR algorithm. Experimental IC50 values were converted to pIC50 values, chemical structures of active compounds were drawn, optimized and calculated to obtain values of a large set of 3237 descriptors. Four datasets were separately prepared. For each dataset, values of calculated descriptors were assigned as independent (X) variables while the experimentally obtained pIC50 values were assigned as dependent (Y) variables. Correlation-based feature selection was performed to select a set of informative descriptors for constructions of QSAR models (HuCCA-1 model = 5 descriptors, A549 model = 4 descriptors, HepG2 model = 3 descriptors, and MOLT-3 model = 4 descriptors). Definitions and calculated values of informative descriptors are shown in Table 2 and Table S3, respectively.

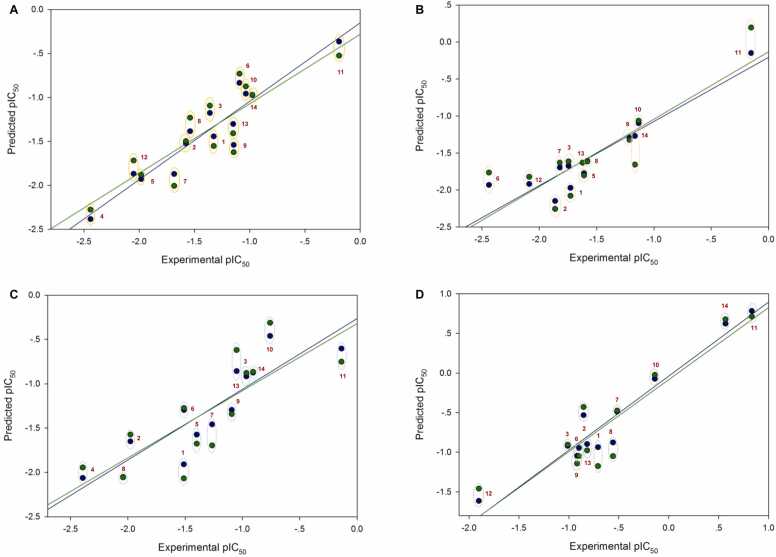

Four QSAR models were successfully constructed using MLR for predicting anticancer activities against four cancer cell lines. Values of experimental versus predicted activities (pIC50) were plotted (Fig. 4) and provided in Table S4. All built models displayed preferable predictive performance as indicated by high correlation values (R: training set = 0.8928–0.9664; testing set = 0.7824–0.9157) and low root mean squared error values (RMSE: training set = 0.1755–0.2600; testing set = 0.2726–0.3748, Table 3). The QSAR models (Table 3) revealed that polarizability (MATS3p and BELp8), van der Waals volume (GATS5v, GATS6v, and Mor16v), mass (G1m), electronegativity (E1e), and dipole moment (Dipole and EEig15d) as well as ring complexity (RCI) and shape of the compound (SHP2) were the key structural properties contributing to anticancer activities of the studied compounds. Particularly, the ring complexity plays high impact on activity against the HuCCA-1 cell line as shown by its highest regression coefficient value (r = 22.0347). Similarly, electronegativity (E1e, r = 11.9568) and shape (SHP2, r = 8.3401) were revealed to be two main key properties governing cytotoxic activity against the MOLT-3 cell (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Plots of experimental activities versus predicted activities from 4 QSAR models. A: HuCCA-1 model (N = 14), B: A549 model (N = 13), C: HepG2 model (N = 13), D: MOLT-3 model (N = 12). Plots of training set are presented as blue circles and blue solid regression lines whereas those of testing set (leave-one-out cross-validation) are shown as green circles and green regression lines. The points are labeled with compound’s number in red. Experimental and predicted pIC50 values are grouped for each compound with dotted circles.

Table 3.

Four constructed QSAR anticancer models and their predictive performances.

| Model | Equation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HuCCA−1 | pIC50= | −2.1484(MATS3p) − 0.1205(Dipole) − 0.8084 (GATS5v) − 0.1086 (GATS6v) + 22.0347 (RCI) −31.6871 | ||

| 2 | A549 | pIC50= | 0.2967(EEig15d) + 0.4053(Mor15u) − 9.1404(E2u) + 1.2161 (G1m) + 2.431 | ||

| 3 | HepG2 | pIC50= | −7.1769(Mor16v) − 9.4713(E2u) + 2.0053(R5u) + 2.2873 | ||

| 4 | MOLT−3 | pIC50= | 4.6521(BELp8) + 8.3401(SHP2) −11.9568(E1e) −4.9414 (Du) + 2.7266 | ||

| Predictive performance | |||||

| Model | N | Training | LOOCV | ||

| Rtr | RMSEtr | RCV | RMSECV | ||

| HuCCA−1 | 14 | 0.9443 | 0.1755 | 0.8616 | 0.2726 |

| A549 | 13 | 0.9310 | 0.1952 | 0.8442 | 0.3130 |

| HepG2 | 13 | 0.8928 | 0.2600 | 0.7824 | 0.3748 |

| MOLT−3 | 12 | 0.9664 | 0.1787 | 0.9157 | 0.2864 |

N denoted the number of active compounds included in the dataset.

Rtr: Correlation coefficient of the training set.

RMSEtr: Root mean square error of the training set.

RCV: Correlation coefficient of the leave-one-out cross validation set.

RMSECV: Root mean square error of the leave-one-out cross validation set.

9. QSAR-guided design of structurally modified compounds

Four constructed QSAR models were further applied to guide the rational design of an additional set of structurally modified compounds. Key descriptors presented in the models were used to guide the structural modifications. Six original compounds (1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14) were selected as representative prototypes according to their promising experimental potencies (OH-bearing compounds: 10, 11, and 14), original pharmacophore (unsubstituted 1,4-NQ: 1), and (di-halogen containing compounds: 7 and 8). Several types of moieties were substituted on different positions of the prototypes to give a total set of 248 newly designed compounds (series 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14, Fig. 3) in which their anticancer activities against four cancer cell lines were predicted using the constructed QSAR models. Chemical structures of all structurally modified compounds are provided in SMILES format (Table S5) and their predicted activities (expressed as predicted pIC50 values, Table S6) are provided in supplementary information.

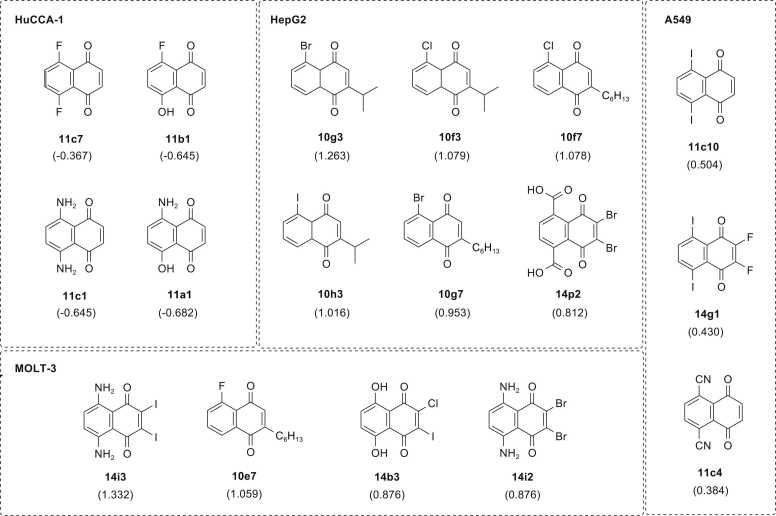

To reveal the efficacy of QSAR-driven design, predicted activities (predicted pIC50 values) of the modified compounds were compared to those of their prototypes (experimental pIC50 values). The numbers of newly designed compounds with improved predicted activities against HuCCA-1, A549, HepG2, and MOLT-3 cell lines were 40, 108, 104, and 87 compounds, respectively. Among others, the modification strategy to obtain modified compounds series 10 was noted to be the most promising strategy displaying the compounds with better activities against three cell lines (i.e., A549 = 45 compounds, HepG2 = 33 compounds, and MOLT-3 = 57 compounds) whereas that of the modified series 8 was noted as the best one for improving activities against the HuCCA-1 (13 compounds). In overview, most of the newly designed compounds provided improved activities when compared to their prototypes, which suggested the efficacious QSAR-guided modification strategies. Most of the top-ranking modified compounds displaying the most preferable predicted pIC50 values against each cell line were noted to be the members from series 11 for HuCCA-1 (i.e., 11c7, 11b1, 11c1, and 11a1) and A549 (i.e., 11c4, and 11c10), series 10 for HepG2 (i.e., 10g3, 10f3, 10f7, 10h3, and 10g7), and series 14 for MOLT-3 (i.e., 14i3, 14b3, and 14i2). Some of modified compounds from series 14 also displayed high predicted activities against A549 (14g1) and HepG2 (14p2). Similarly, compound 10e7 was listed as the second most potent one for MOLT-3, Fig. 5. Considering the range of predicted pIC50 values of top-ranked compounds, the top-ranked modified compounds predicted as the most potent ones against MOLT-3 showed the most promising predicted activities (predicted pIC50: 0.876–1.332), followed by HepG2 (predicted pIC50: 0.812–1.263), A549 (predicted pIC50: 0.384–0.504), and HuCCA-1 (predicted pIC50: −0.682 to −0.367), respectively, Fig. 5. This is in concordance with our experimental findings which suggested the MOLT-3 cell line as the most sensitive cell line for these series of studied 1,4-NQ derivatives.

Fig. 5.

Summary of top-ranking newly designed compounds with promising predicted activities.

10. Structure-activity relationship analysis

Comparative analysis of key structural features essential for desirable anticancer activities was conducted for modified compounds (modified series 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14) versus their prototypes (compounds 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14). In overview, findings showed that most of the new compounds designed by QSAR-guided structural modifications provide improved activities when compared to their parents. For each cell line, the top-ranked modified compounds and effects of changing substitutions on the core structure were discussed.

Two members from series 11 and one member from series 14 were noted as top three compounds against A549 cell line (11c10 > 14g1 > 11c4: predicted pIC50 = 0.504, 0.430, and 0.384, respectively), Fig. 5. Results suggested that the best improved activities were achieved when di-OH group at R5 and R6 positions of compound 11 (R5 = R6 = OH, experimental pIC50 = −0.512, Table S2) were replaced with di-I and di-CN groups to give 11c10 and 11c4, respectively. This effect could be due to the influence of modifications on decreasing the values of Mor15u and E2u descriptors (11: Mor15u = 0.625, E2u = 0.508, Table S3; 11c10: Mor15u = −0.131, E2u = 0.403, 11c4: Mor15u = 0.046, E2u = 0.413, Table S6). The second most potent compound 14g1 (R1 = R2 = F, R5 = R6 = I) was obtained by replacing di-Cl group on R1 and R2 as well as di-OH groups on R5 and R6 positions of the prototype 14 with di-F and di-I groups, respectively. The improved activity of compound 14g1 beyond its prototype was observed to be via the decreasing of E2u value (14: E2u = 0.529, Table S3; 14g1: E2u = 0.411, Table S6). Considering these top three compounds, it was suggested that di- or tetra- substitutions of electron withdrawing groups (i.e., I, F, and CN) on the 1,4-NQ core may be essential for enhancing anticancer activities against the A549 cell line.

Five compounds from modified series 10 and one compound from series 14 were predicted as the most promising compounds against HepG2 cell line (10g3 > 10f3 > 10f7 > 10h3 > 10g7 > 14p2; predicted pIC50 = 1.263, 1.079, 1.078, 1.016, 0.953, and 0.812, respectively, Fig. 5). From the top four most potent compounds, the best improved activities were achieved when the OH group (R5) of the prototype 10 (R2 = CH3, R5 = OH, pIC50 = −0.759, Table S2) was replaced with halogen atoms (i.e., Br, I, and Cl) and the methyl group at R2 position was substituted by C3-branched alkyl chain or C6H13 long alkyl chain. Their enhanced activities were observed to be via the increasing R5u but decreasing E2u descriptor values when compared to their prototype 10 (10: R5u = 0.842, E2u = 0.495, Table S3; 10g3: R5u = 1.241, E2u = 0.402, 10f3: R5u = 1.247, E2u = 0.403, 10f7: R5u = 1.245, E2u = 0.392, 10h3: R5u = 1.235, E2u = 0.401, 10g7: R5u = 1.240, E2u = 0.392, Table S6). Similar effects were also observed for other compounds from subseries 10c with positive predicted pIC50 values (i.e., 10c4, 10c5, 10c6, and 10c7: predicted pIC50 = 0.390, 0.067, 0.096, 0.413, Table S6, chemical structures are provided as SMILES in Table S5). All these 10c compounds are OH derivatives bearing branched or long alkyl chain with different length on R2 position. For series 14, the improved activity was obtained when the di-Cl atoms (R1 = R2 = Cl) of prototype 14 (pIC50 = −0.907, Table S2) were replaced with di-Br whereas its di-OH groups (R5 =R6 = OH) were substituted with di-COOH group to give compound 14p2 (R1 = R2 = Br and R5 = R6 = COOH, predicted pIC50 = 0.812). Like series 10, these effects were observed to be via the increasing R5u but decreasing E2u values compared with prototype 14 (14: R5u = 0.782, E2u = 0.529, Table S3; 14p2: R5u = 1.179, E2u = 0.419, Table S6). Preferable improvements were also observed for the compounds bearing di-CF3 at R1 and R2 positions (14o4: R5 = R6 = CHO, predicted pIC50 = 0.609 and 14m4: R5 = R6 = CN, predicted pIC50 = 0.559, chemical structures are provided as SMILES in Table S5).

Three members from modified series 14 and one member from series 10 were noted as the most promising compounds against MOLT-3 cell line (i.e., 14i3 > 10e7 > 14b3 = 14i2; predicted pIC50 = 1.332, 1.059, 0.876, and 0.876, respectively, Fig. 5). Two halogen derivatives from subseries i (i.e., 14i3: R1 = R2 = I and 14i2: R1 = R2 = Br) bearing di-NH2 (R5 = R6 = NH2) showed the most promising activities, which may be due to the effects of substitutions on increasing shape profile index (SHP2) but decreasing electronegativity (E1e) values of the compounds comparing to their prototype 14 (14: SHP2 = 0.557, E1e = 0.474, Table S3; 14i3: SHP2 = 0.568, E1e = 0.410, 14i2: SHP2 = 0.564, E1e = 0.457, Table S6). It was also noted that if the di-OH groups on R5 and R6 were maintained, the best activities were achieved when R1 or R2 was substituted with a Cl atom (i.e., 14b3, predicted pIC50 = 0.876). Additionally, improved activity can be achieved if the di-OH groups on R5 and R6 positions were replaced with di-SH groups to give compound 14j3 (R1 = R2 = I, chemical structure is provided as SMILES in Table S5, predicted pIC50 = 0.709, Table S6). For modified series 10, all modified compounds exhibited better predicted activity than the prototype 10 (R2 = CH3 R5 = OH, pIC50 = −0.140, Table S2) except for 10d5 (R2 = CF3 R5 = OH, pIC50 = −1.790, Table S6). Three compounds including 10e7 (R2 = C6H13, R5 = F, Fig. 5), 10h4 (R2 = C4H9, R5 = I), and 10h7 (R2 = C6H13, R5 = I) were ranked as top three compounds of the series displaying the highest predicted activities (10e7: predicted pIC50 = 1.059, 10h4: predicted pIC50 = 0.873, 10h7: predicted pIC50 = 0.735, Table S6; chemical structures of 10h4 and 10h7 are provided as SMILES in Table S5). Particularly, these compounds displayed considerably high atomic polarizability (BELp8) values (BELp8: 10e7 = 0.778, 10h4 = 0.566, and 10h7 = 0.686, respectively) when compared to prototype 10 (BELp8 = 0.168, Table S3). It was also noted that the most preferable activities were achieved when the OH group at R5 position was replaced with a halogen atom (such as F and Br) and length of the long alkyl chain substituted at R2 position was increased.

Four newly designed compounds from series 11 were predicted as the most potent compounds against HuCCA-1 cell line (11c7 >11b1 = 11c1 > 11a1; predicted pIC50: 11c7 = −0.367, 11b1 and 11c1 = −0.645, and 11a1 = −0.682, Table S6). However, these top-ranked compounds displayed less predicted activities (lower predicted pIC50 values) than prototype 11 (experimental pIC50 = −0.191, Table S2). These compounds displayed higher values of ring complexity (RCI) compared to the prototype 11 (11: RCI = 1.427, Table S3; 11c7: RCI = 1.434, 11b1: RCI = 1.436, 11c1 and 11a1: RCI = 1.444, Table S6), but their impaired activities could be due to the less negative values of three descriptor variables (Table S6) possessing negative regression coefficient (r) such as MATS3p, Dipole, GATS5v, and GATS6v, model 1, Table 3). It was found that the substitution of di-F at R5 and R6 positions on prototype 11 provided the most potent compound 11c7 (R5 = R6 = F, pIC50 = −0.367). However, decreased activity was noted when the F atom (R6) of 11c7 was replaced with OH group to give compound 11b1 (R5 = F, R6 = OH, pIC50 = −0.645). Similar effects were observed when compared to compound 11c1 bearing di-NH2 group (R5 = R6 = NH2, pIC50 = −0.645) with compound 11a1 (R5 = NH2, R6 = OH, pIC50 = −0.682), Table S6. These findings suggested that the replacement of OH group (R5) of compound 11 (R5 = R6 = OH, pIC50 = −0.191, Table S2) with F or NH2 group can enhance activities of the compounds (11b1 and 11a1: pIC50 −0.645 and −0.682, respectively, Table S6), and this effect was more noticeable when another OH group (R6) was replaced with additional F or NH2 group (11c7 > 11b1 and 11c1 > 11a1, Fig. 5). Although the top-ranking modified compounds with the highest predicted activities against HuCCA-1 displayed less potency than prototype 11, QSAR-guided structural modification strategy could improve activities of modified compounds from other series (numbers of compounds with improved activities: series 1 = 3 compounds, series 7 = 12 compounds, series 8 = 13 compounds, and series 14 = 1 compound) with noticeable improvements observed for the compounds derived from prototypes 7 and 8 with lower experimental activities (experimental pIC50 = −1.684 and −1.540, respectively, Table S2).

An overview of key structural features essential for potent activities of the newly designed compounds (presented in Fig. 5) are summarized in Fig. 6. It was revealed that the potent compounds (series 11 and 14) against all cancer cell lines, except for HepG2, shared some common features such as the presence of 5,8-disubstitution (R5 and R6 groups, Fig. 6) of two halogen atoms (F and I), or electron donating/withdrawing groups (NH2 and CN), or di-OH group on the 1,4-NQ core. The presence of additional 2,3-di-substitutions (R1 and R2 groups, Fig. 6) of di-halogen atoms (F, I, and Br) would be essential for the activity of compounds from series 14 against MOLT-3 and A549 cell lines. In contrast, those promising compounds for HepG2 (series 10) displayed different patterns in which the presence of a mono-substituted halogen atom (Cl, Br, and I) on 8-position (R5 group, Fig. 6) along with a long or branched alkyl chain substituted on 3-position (R2 group, Fig. 6) of the core structure are necessary for their potent activities.

Fig. 6.

Summary of key structural features influencing potent predicted activities of newly designed compounds.

11. Predictions of drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles

One of the current challenging issues in drug discovery is the late-stage failures which are mainly due to undesirable pharmacokinetics and considerable toxicity profiles (ADMET)[54]. This has driven the in silico predictions at early stages of development highly encouraged [55], [56]. Herein, a set of original (10, 11, and 14) and newly designed compounds (from series 10, 11, and 14, Fig. 5) with promising predicted activities were selected for investigating their ADMET profiles using in silico web-based tools as summarized in Table 4, Table 5. Drug-likeness of the compounds were assessed according to the Lipinski’s rule and QED (Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness), Table 4. Lipinski’ rule is a commonly used as a guideline to assess oral availability of bioactive molecules [57]. However, the compounds with rule’s violations may clinically exhibit oral availability. Therefore, a quantitative estimation of drug-likeness using QED is also encouraged. The QED quantifies drug-like properties of the compounds based on the concept of desirability. The estimate score was ranged from 0 to 1 (0 = all properties unfavorable, 1 = all properties favorable)[58]. The predictions revealed that all selected NQ compounds are drug-like molecules without violations according to Lipinski’s rule. However, some of them displayed poor QED scores (less than 0.67) including the original compound 11 and most of its modified members as well as most of modified compounds from series 14, Table 4. Additionally, these NQ compounds were predicted for their ease to be synthesized using synthetic accessibility score (SAS). Results indicated that all compounds are easy to synthesize as shown by their low SAS scores, Table 4.

Table 4.

Drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles of selected original and modified compounds.

|

Prediction was performed using web-based tool: ADMETlab 3.0 (https://admetlab3.scbdd.com/).

Grey highlights denoted preferable / excellent. Yellow highlights denoted moderately preferable. Pink highlights denoted poor.

Drug-likeness parameters:QED: Quantitative estimate of drug-likeness based on 8 properties (i.e., MW, log P, No. of HBA, NHBD, PSA, Number of rotatable bonds, the no. of aromatic rings (NAr), and the number of alerts for undesirable functional groups). Cutoff: > 0.67 = excellent, ≤ 0.67 = poor. SAS: Synthetic accessibility score = the ease to be synthesized (1 = easy to 10 = very difficult) Cutoff: ≤ 6 = excellent, > 6 = poor. Lipinski’s rule: MW ≤ 500; logP ≤ 5; Hacc ≤ 10; Hdon ≤ 5. Cutoff: < 2 violations = excellent, ≥ 2 violations = poor.

Absorption, distribution, and excretion parameters:HIA: Human intestinal absorption. Category 0: HIA > 30 %, Category 1: HIA < 30 % Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent; 0.3–0.7 = medium; 0.7–1.0 = poor. F50: %Bioavailability: Category 0: % bioavailability ≥ 50 %, Category 1: % bioavailability < 50 %. Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent, 0.3–0.7 = medium; 0.7–1.0 = poor. VDss: The volume of distribution at steady state (expressed as logVDss: L/kg). Cutoff: 0.04–20 = excellent, otherwise = poor. PPB: Plasma protein binding. Cutoff: ≤ 90 % = excellent, otherwise = poor. BBB: Blood brain barrier penetration. Category 1: logBBB > -1, Category 0: logBBB ≤ -1. Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent, 0.3–0.7 = medium; 0.7–1.0 = poor. cl-plasma: Plasma clearance (mL/min/kg). 0–5 = excellent, 5–15 = medium, > 15 = poor.

Toxicity profile:Neurotoxicity: Drug-induced neurotoxicity. Nephrotoxicity: Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Category 0: Non-toxic = 0, Category 1: toxic = 1. Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent, 0.3–0.7 = medium, 0.7–1.0 = poor. H-HT: Human hepatotoxicity. Carcinogenicity: Category 1: carcinogens; Category 0: non-carcinogens. Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent, 0.3–0.7 = medium, 0.7–1.0 = poor. LD50_oral: Rat oral acute toxicity. Category 0: low-toxicity, > 500 mg/kg; Category 1: high-toxicity; < 500 mg/kg. Cutoff: 0–0.3 = excellent, 0.3–0.7 = medium, 0.7–1.0 = poor.

Table 5.

Predicted potentials of being metabolizing enzymes substrates or inhibitors of the selected original and modified compounds.

|

Prediction was performed using web-based tool: ADMETlab 3.0 (https://admetlab3.scbdd.com/). Predictions are represented as probability values.

Grey highlights: + ++ denoted probability value 0.9–1.0. Green highlights: + + denoted probability value 0.7–0.9. Blue highlights: + denoted probability value 0.5–0.7.

Pink highlights: - denoted probability value 0.3–0.5. Yellow highlights: -- denoted probability value 0.1–0.3. White highlights: --- denoted probability value 0–0.1.

Oral bioavailability and intestinal absorption are parameters influencing therapeutic effectiveness of the drugs [59]. Compound 11 and most of its modified members (except for 11c4 and 11c10) displayed the most promising oral availability profile with excellent human intestinal absorption (HIA) and favorable bioavailability greater than 50 % (F50), suggesting their possibilities to be orally administered. In contrast, almost all modified compounds from series 10 and 14 demonstrated poor absorption properties as shown by their moderate to poor HIA and F50 values, Table 4. This indicated that other alternative routes of administration are recommended for these compounds to ensure their optimal therapeutic levels.

Distribution of drug to reach the target site of action is an essential key factor for effective therapeutic outcomes. Volume of distribution at steady state (VDss) is a parameter indicating relative affinity of the drug to tissue and plasma protein [60]. Drugs with higher binding affinity to plasma protein are less likely to distribute into tissues than those with lower binding affinity. From the predictions, these set of NQ compounds may not effectively distribute to the target tissues as shown by their low volumes of distribution (VDss) and high plasma protein binding potentials (PPB). However, some of them may be potentially developed for CNS-targeting therapeutics as shown by their favorable blood-brain-barrier penetration (BBB) abilities, Table 4.

Drug metabolism is an important process involved in biotransformation of the drugs to facilitate drug elimination or conversion of pro-drug to active form[61]. Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) is a metabolizing enzyme family playing main role in metabolism of several kinds of drugs, bioactive ingredients, and xenobiotics [62]. Inhibition or induction of the CYP450 enzymatic function could also lead to drug-drug interaction which affects therapeutic effectiveness or potential toxicities of the drug used. Herein, the compounds were assessed for their possibilities to act as substrates or inhibitors of some CYP450 isozymes with clinical importance (i.e., CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and CYP2B6), Table 5. Results indicated that most of the compounds displayed high probabilities to act as inhibitors of CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP2B6, but are less likely to act as substrates of these metabolizing enzymes. Accordingly, these NQ compounds should be considered for their potential drug-drug interactions.

Elimination of drug, measured by clearance, indicates the change in plasma drug concentration in time course [63]. Most of the compounds showed moderate to excellent plasma clearance (cl-plasma) values indicating their abilities to be eliminated. Although, most of the compounds exhibited low to moderate toxicity profiles (i.e., neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity (H-HT), oral acute toxicity (LD50_oral), all of them should be concerned for their high carcinogenicity, Table 4.

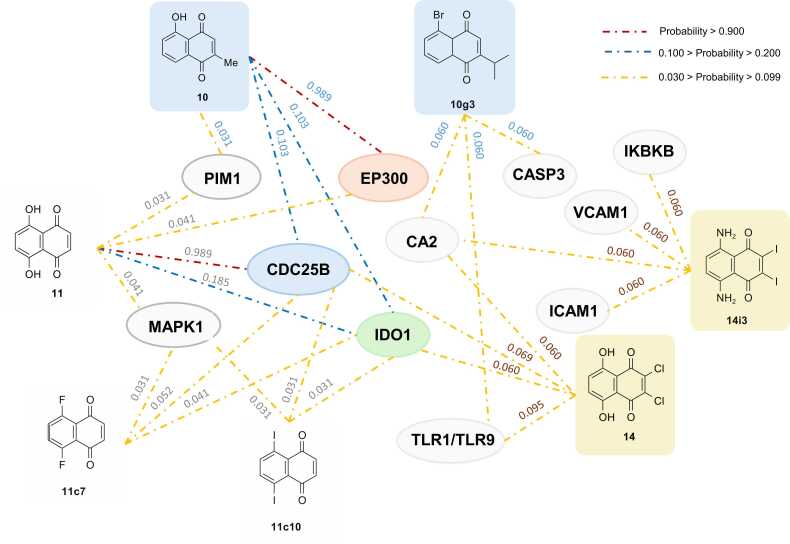

12. Predictions of potential biological targets and molecular docking

Target discovery (or target identification) is a process to identify appropriate biological molecules that can be modulated upon binding with drugs to achieve therapeutic effects, which plays essential roles in successful drug development. The conventional target identification methods are costly and time-consuming. Therefore, computational approaches have become alternative tools for target discovery utilizing the availability of data sources and machine learning to predict potential biological targets of the compounds of interest [64]. In this study, potential biological targets of the selected NQ compounds with promising activities (i.e., compounds 10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3) were investigated and summarized in Fig. 7 and Table S7.

Fig. 7.

Summary of potential biological targets of selected NQ compounds (10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3). Values indicated probability (lowest = 0, and highest = 1). Red, blue, and yellow dotted lines indicated the relationships with probability value ranges of greater than 0.900, between 0.100 and 0.200, and between 0.030 and 0.099, respectively. List of abbreviations: Histone acetyltransferase p300 (EP300), Dual specificity phosphatase Cdc25B (CDC25B), Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1), Carbonic anhydrase II (CA2), Serine/threonine-protein kinase PIM1(PIM1), Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAP2K1), Caspase-3 (CASP3), Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1), Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM1), Toll-like receptor (TLR7/TLR9), Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase beta subunit (IKBKB).

In overview, three common possible anticancer targets were predicted for original compounds (10 and 11) including histone acetyltransferase p300 (EP300), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1), and dual specificity phosphatase Cdc25B (CDC25B). Both compounds were predicted to possibly interact with all these targets with various degrees of probability. Compound 10 showed the highest possibility against EP300, followed by CDC25B and IDO1 (prediction values: EP300 = 0.989, CDC25B and IDO1 = 0.103) whereas compound 11 showed the highest probability against CDC25B followed by IDO1 and EP300 (prediction values: CDC25B = 0.989, IDO1 = 0.185, and EP300 = 0.041), Fig. 7. In contrast, compound 14 demonstrated the highest possibility to interact with toll-like receptors (TLR7/TLR9), followed by CDC25B, IDO1, and carbonic anhydrase II (CA2), respectively (prediction value: TLR7/TLR9 = 0.095, CDC25B = 0.069, IDO1 and CA2 = 0.060), Fig. 7.

Unique patterns of potential targets were observed for each modified compound series. Two newly designed compounds from series 11 (11c7 and 11c10) showed similar potential targets (i.e., IDO1 and CDC25B) to their prototype 11. Conversely, compounds 10g3 and 14i3 demonstrated different potential targets from their prototypes (10 and 14), but both shared carbonic anhydrase II (CA2) as their common target, Fig. 7. Compound 10g3 displayed the equivalent probability against two targets (i.e., caspase-3 (CASP3) and CA2, probability value = 0.060). Similarly, compound 14i3 showed equal possibility to interact with some targets involved in cancer metastasis (i.e., intercellular adhesion molecule-1 or ICAM1[65] and vascular cell adhesion protein 1 or VCAM1 [66], probability values = 0.060).

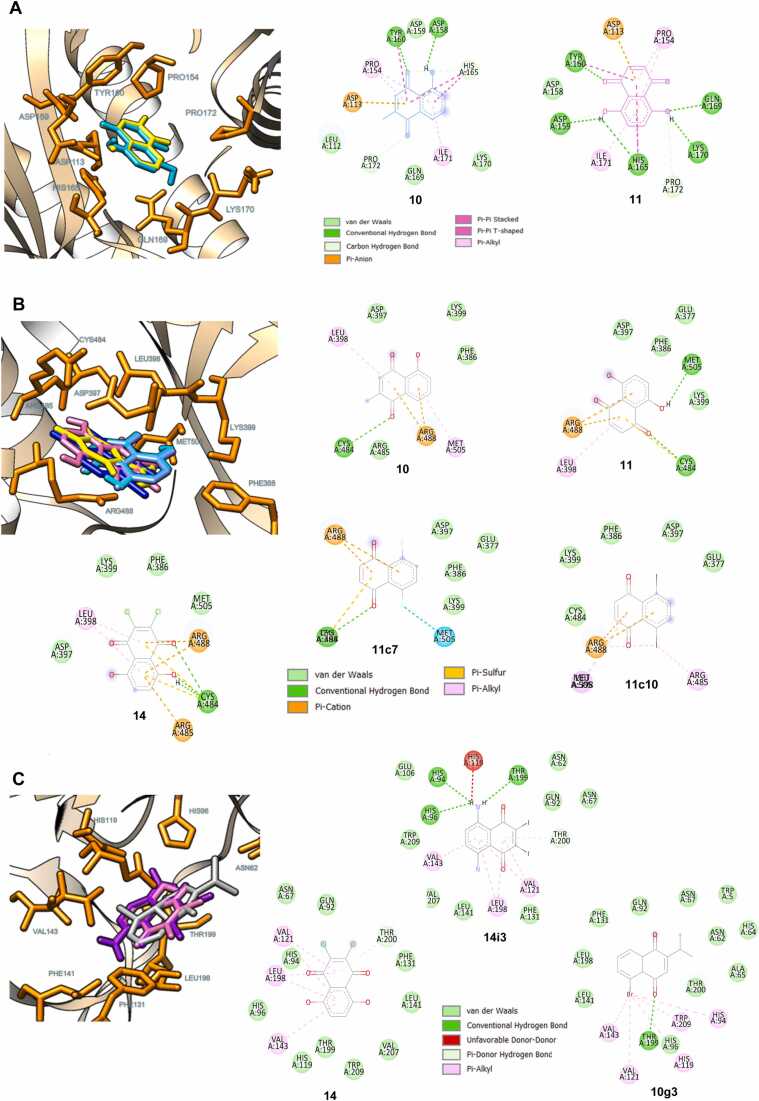

Molecular docking was performed to reveal possible binding modes of the studied NQs (10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3) against the selected targets with the highest predicted probability values (i.e., EP300, CDC25B, and CA2). It was shown that all compounds studied could occupy the binding pocket of their predicted targets (EP300, CDC25B, and CA2, respectively), Fig. 8 (A-C). Two-dimensional protein-ligand interaction diagrams revealed that the NQ ring of compounds 10 and 11 facilitated the binding with the EP300 target via the formation of pi-anion interaction with ASP113 as well as the pi-alkyl/pi-pi interactions with PRO154 and ILE171. The carbonyl oxygen atom of the NQ ring also contributed to the conventional hydrogen bond formation with TYR160 (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the NQ ring played roles in binding with CDC25B through the formation of cation-pi (with ARG488) and pi-interactions (with LEU398, ARG485, and MET505), while the carbonyl oxygen atom of the NQ ring formed conventional hydrogen bonding with CYS484. The substitution of the OH (11) or F (11c7) atom on the NQ core was found to facilitate the formation of the additional hydrogen bond or halogen interaction with MET505, respectively (Fig. 8B). For the binding with CA2, a similar binding interaction pattern was observed for compounds 14 and 14i3, in which the NQ ring played roles in pi-interactions with THR200, VAL121, VAL143, and LEU198. In contrast, the substituted Br atom of compound 10g3 contributed to these pi-interactions (with HIS94, HIS119, VAL121, VAL143, and TRP209), while its NQ ring facilitated the hydrogen bond formation with THR199 (Fig. 8C). In overview, the aromatic NQ ring is a crucial structural feature playing the main roles in the binding through pi-interactions. The substituted groups on the ring also contribute to the additional formations of binding interactions such as halogen bonding and conventional hydrogen bonding. However, it should be noted that the binding energy values of these NQ-based compounds are less preferable than those of the co-crystallized inhibitors (Table S8 and Figure S2).

Fig. 8.

Possible binding modes and 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams of the selected naphthoquinones against three predicted targets. A: EP300 (PDB ID: 5KJ2), docked compounds 10 and 11 are illustrated in yellow and cyan, respectively. B: CDC25B (PDB ID: 4WH9), docked compounds 10, 11, 14, 11c7, and 11c10 are shown in yellow, cyan, pink, light blue, and dark blue, respectively. C: CA2 (PDB ID: 5NY6), docked compounds 14, 10g3, and 14i3 are displayed in pink, grey, and purple, respectively.

Cell cycle regulation is well-known for its impacts on cancer cell proliferation, progression, and metastasis [67], [68]. Cell division cycle 25 (CDC25) phosphatases plays roles in cell cycle regulation and is highly expressed in many cancers [69] renders its inhibition a promising anticancer strategy [70]. Quinone-based analogs including compound 3 (menadione) were previously reported to inhibit CDC25b [71], [72], [73], [74], emphasizing the potential of 1,4-NQ based compounds to be further developed as CDC25b inhibitors. Most of the clinically available anticancer drugs are cell cycle regulating agents (i.e., alter expression of cell cycle related gene, activity of intracellular enzyme, proteins, and signal factors)[67], but their effectiveness is limited mainly due to drug resistance [75]. Accordingly, current strategies for anticancer therapy has been driven towards targeting epigenetic regulators [76].

Epigenomic alterations, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications and histone methylation, play key roles in many solid and hematological cancers [77]. Epigenomic alterations lead to metabolic adaptation of the tumor cells and alteration of the immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, making the targeting tumor immunometabolism one of attractive strategies gaining attention in current cancer therapies [78]. Histone acetyltransferases p300 display sequence homology and overlapping functions with histone acetyltransferase CREB-binding protein (CBP), so both often referred together as CBP/p300. CBP/p300 acts as epigenetic transcription co-activators playing roles in tumorigenesis, cancer cell proliferation, cancer cell survival, apoptosis, and metastasis [79], [80]. Over-expressed CBP/p300 was also found in many types of cancers including drug resistance ones [81]. Accordingly, CBP/p300 is a promising target for combating many types of cancers [82], especially hematological malignancies [83], [84], [85]. Currently, several CBP/p300 inhibitors have been developed for anticancer therapeutics [86].

Besides the above-mentioned strategies, targeting tumor microenvironment and cancer metabolism as well as cancer immunotherapy have been widely studied for improving therapeutic outcomes. IDO1 has been recognized as one of promising targets in cancer immunotherapy [87], [88], [89]. IDO1 is a rate-limiting enzyme functions for converting tryptophan into metabolites that create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, a suitable condition for promoting cancer growth and cancer immune escape [90]. Furthermore, the development of carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitors has gained attention in current anticancer drug development [91]. Carbonic anhydrase catalyzes the interconversion of carbon dioxide and water into bicarbonate and protons. Therefore, it plays a crucial role in maintenance of acid-base balance and controlling pH of tumor microenvironment [92]. Currently, derivatives of 1,4-NQ were developed as potent CA2 inhibitors with IC50 values in nanomolar range [14], [93].

In this study, some of the original compounds (2, 3, and 10) and their derivatives were reported as inhibitors of the predicted targets (i.e., p300, CDC25B, IDO1, and CA2). Compound 10 (plumbagin) is a natural-derived NQ reported to elicit anticancer effects against many types of cancers via the modulations of several signaling pathways relating to apoptosis, autophagy, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, as well as inhibiting angiogenesis and tumor migration [94]. Compound 10 was also reported as an inhibitor of p300 [95] and CDC25B [96]. Compound 3, known as menadione or vitamin K3, was reported to block the binding of HIF-1α to CBP/p300 leading to the inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway [97]. Moreover, compound 3 and other 1,4-NQ derivatives were reported as IDO1 inhibitors [98], [99]. A derivative of compound 2 (lawsone) was also reported as CA2 inhibitor [100].

Besides targets relating to cell cycle and epigenomic alterations, targets relating to inflammation and immune responses were predicted for these set of NQs (14 and 10g3: TLR7/TLR9; 14i3: nuclear factor kappa B kinase beta subunit or IKBKB). It was documented that host immune response [101] and inflammation display close linkage in regulating cancer development, progression, and responses to therapy [102]. Some toll-like receptor agonists [103], [104] and anti-inflammatory drugs [105] have been developed or repurposed for their implications in cancer therapeutics. Furthermore, some compounds may be beneficial for neurodegenerative diseases as shown by their potential neuroprotective-related targets (10, 11, and 10g3: monoamine oxidases A and B; MAOA and MAOB, and beta-secretase 1 or BACE1). Notably, these neurological [106], [107] and inflammatory [108], [109] targets are documented for their roles in cancer and are noted to be potential targets for current anticancer drug development. This suggested that the studied NQs could possibly be further developed for therapeutics both inside and outside cancer areas.

13. Limitations and future directions of the study

The small-sized molecules have gained considerable attention in the current drug discovery due to their promising characteristics that allow preferable drug-like and pharmacokinetic profiles, enabling their multiple applications [110]. Some small-sized 1,4-NQ derivatives (i.e., lawsone (2), menadione (3), juglone (5), and plumbagin (10), Fig. 1) have been widely used as a template for the design of new bioactive derivatives [15]. Accordingly, this study aimed to focus on exploring the structural influences on the cytotoxic effects of a specific class of small-sized naphthoquinone derivatives (bearing mono-, di-, tri- and tetra substitutions). Therefore, these QSAR models were inevitably built from relatively small datasets due to the limited numbers of compounds studied. Several issues concerning the QSAR models built from small datasets have been pointed out, including model robustness and the limited generalizability [111]. However, the QSAR models built from small datasets have still been recognized for their benefits in accelerating the drug discovery pipeline at an early stage, in which the bioactivity endpoints from the interest compounds are still limited [112]. Additionally, there are none of the current general rules established for the impact of the size of the training datasets on the predictive quality of the models. It was suggested that not only the size of the dataset but also several factors (i.e., specific dataset, descriptor types, descriptor selection, and statistical analysis methods used for assessments) integrally influence the predictability of the models [111].

The best practice for model validation is another debating issue. While external validation is noted to be the most suitable way to assess the generalizability of the model, cross-validation is recognized to provide more reliable assessments of the overall predictive performance of the model, particularly when the original dataset is too small to be provided as an external test set or the availability of the external test set is limited [113], [114], [115]. LOOCV is one of the suitable methods for validating QSAR models built from small datasets [116]. It was also suggested that cross-validation methods such as k-fold cross-validation can be used to comprehensively assess the model’s predictive performance [111]. Regarding this concern, four constructed QSAR models (i.e., HuCCA-1, A549, HepG2, and MOLT-3 models) were further validated using k-fold cross-validation (k = 5 and 10, Table S4a). It was shown that these models provided almost comparable predictive performance with those of leave-one-out cross-validation sets when validated with k-fold cross-validations (k = 5 and 10).

The impact of small-sized datasets on the generalizability of the QSAR model is another concerning issue. Applicability domain (AD) defines the trustable prediction of the unknown compounds based on their similarities (i.e., chemical, structural, and properties) to those of the compounds used to build the model [117]. It is well-recognized that no matter how large the trained dataset, the generalizability of the constructed models to predict unknown compounds outside the chemical space of the trained compounds is still limited [118]. K-means clustering is one of the methods effectively used to assess the applicability domain of the compounds in the training set [119]. The AD of the constructed QSAR models was assessed by exploring the chemical space of the trained compounds (1-14) using K-means clustering. The chemical space plot (Figure S1) was created using the ChemMine Tools [120] to indicate the boundary of the model’s trustable predictions. Accordingly, it should be noted that the predictions of unknown compounds outside these boundaries are along with chances of prediction errors and/or meaningless interpretations.

Lastly, it should be noted that the newly designed compounds proposed in this study have not yet been synthesized and validated for their predicted activities and properties. The target prediction and molecular docking simulations performed herein only provided the possibilities towards the potential targets. Future chemical synthesis, in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies are required to ensure successful development of these NQ-based compounds as therapeutics.

14. Conclusions

A set of 1,4-NQ derivatives (1-14) were experimentally investigated for their anticancer activities against 4 cancer cell lines (i.e., HuCCA-1, A549, HepG2, and MOLT-3). Most of the tested compounds exhibited broad-ranging anticancer activities against all cell types, except for compounds 4, 5, and 12. Compound 11 was noted as the most potent compound providing the highest potency and preferable selectivity against four cancer cell lines (IC50: 0.15 – 1.55 µM) followed by compounds 14 (IC50: 0.27 – 14.67 µM) and 10 (IC50: 1.38 – 13.60 µM), respectively. Among others, MOLT-3 seems to be the most sensitive cell for these class of NQ compounds as indicated by the low IC50 values less than 10 µM (except for compounds 3 and 12). Experimentally obtained activity values (IC50) along with chemical structures of the active compounds were used for preparing four datasets for QSAR modelling. Four QSAR models were successfully constructed using MLR algorithm. The models provided acceptable predictive performance affording high R but low RMSE values (R: training set = 0.8928–0.9664; testing set = 0.7824–0.9157; RMSE: training set = 0.1755–0.2600; testing set = 0.2726–0.3748). The key properties governing anticancer activities of the compounds were revealed to be polarizability (MATS3p and BELp8), van der Waal volume (GATS5v, GATS6v, and Mor16v), dipole moment (Dipole and EEig15d), electronegativity (E1e), mass (G1m) and shape (SHP2). Key predictors from the models were further used to guide the rational design of an additional set of 248 structurally modified compounds (series 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14). It was demonstrated that the QSAR-guided structural modification strategies could facilitate the efficacious design to give new compounds with better predicted activities when compared to their prototypes. Finally, a set of 17 newly designed compounds exhibiting the most promising predicted activities against each cancer cell line was highlighted for potential further development. These modified compounds displayed more promising predicted activities against MOLT-3, HepG2, and A549 cell lines (with positive predicted pIC50 values) when compared to HuCCA-1 cell line (with negative predicted pIC50 values). Structure-activity relationship analysis revealed that the presence of di-halogen, di-OH, or di-NH2 group on 5,8-positions along with di-substitution of halogen atoms on 2,3-positions of the 1,4-NQ core may be essential for potent anticancer activities. Predictions of pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of the highlighted compounds indicated their possibilities for therapeutics, however, some issues regarding considerable poor distribution, potential drug-drug interaction as well as undesirable toxicities should be further optimized to ensure efficacy and safety. Predictions of potential biological targets suggested some cancer-related, inflammatory-related, and immunological-related as well as neurological-related targets as possible targets of these NQ compounds. Molecular docking was conducted to initially reveal possible binding modes of the top-ranked compounds (10, 11, 14, 10g3, 11c7, 11c10, and 14i3) against three predicted anticancer targets (i.e., EP300, CDC25B, and CA2). The core NQ ring was noted as a structural feature essential for the binding interactions, particularly for the formations of pi-interactions. The substituted moieties also noted to facilitate the binding through the formations of additional hydrogen or halogen bonds. However, further studies (both in silico, in vitro, and in vivo) to validate the druggability of these targets are required. In summary, this work demonstrated an integration of experimental assays and computational approaches in facilitating effective design of 1,4-NQ derivatives for anticancer therapeutics. Key structural-activity relationship obtained herein would be beneficial for further screening, design, and structural optimization of the related NQ compounds. However, it is highly suggested that the newly designed compounds need to be further experimentally synthesized, investigated, and validated. Additional assessments (in vitro, in vivo, and clinical trials) are also essential to ensure their pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles for successful development.

Author statement

We certify that this work is original and has not been (as whole or in-part) published, nor currently being under consideration for publication elsewhere. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We also confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process. She is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Veda Prachayasittikul: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Prasit Mandi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ratchanok Pingaew: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Supaluk Prachayasittikul: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Somsak Ruchirawat: Supervision, Resources. Virapong Prachayasittikul: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Veda Prachayasittikul is supported by Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, Research Grant for New Scholar (grant no. RGNS 64 – 167) and Mahidol University (Fundamental Funds: fiscal year 2025 by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF)). Ratchanok Pingaew is supported by Srinakharinwirot University (grant no. 646/2568). We are also indebted to Chulabhorn Research Institute for bioactivity testing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2025.07.040.

Contributor Information

Veda Prachayasittikul, Email: veda.pra@mahidol.ac.th.

Ratchanok Pingaew, Email: ratchanok@g.swu.ac.th.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Giaquinto A.N., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F., Laversanne M., Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Soerjomataram I., et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S.U., Fatima K., Aisha S., Malik F. Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand U., Dey A., Chandel A.K.S., Sanyal R., Mishra A., Pandey D.K., et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis10(4) 2023:1367–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gach-Janczak K., Drogosz-Stachowicz J., Janecka A., Wtorek K., Mirowski M. Historical perspective and current trends in anticancer drug development. Cancers. 2024;16(10):1878. doi: 10.3390/cancers16101878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapoor N., Kandwal P., Sharma G., Gambhir L. Redox ticklers and beyond: naphthoquinone repository in the spotlight against inflammation and associated maladies. Pharm Res. 2021;174 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aminin D., Polonik S. 1,4-naphthoquinones: some biological properties and application. Chem Pharm Bull. 2020;68(1):46–57. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c19-00911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angulo-Elizari E., Henriquez-Figuereo A., Morán-Serradilla C., Plano D., Sanmartín C. Unlocking the potential of 1,4-naphthoquinones: a comprehensive review of their anticancer properties. Eur J Med Chem. 2024;268 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayahi M.H., Hassani B., Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani M., Dastyafteh N., Gohari M.R., Tehrani M.M., et al. Design, synthesis, and cytotoxic activity of 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinone-benzamide derivatives as apoptosis inducers. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-78468-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanad S.M.H. 2,3-diaminonaphthalene-1,4-dione: versatile precursor for the synthesis of molecular systems. Synth Commun. 2025;55(4):281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravichandiran P., Martyna A., Kochanowicz E., Maroli N., Kubiński K., Masłyk M., et al. In vitro and in vivo biological evaluation of novel 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives as potential anticancer agents. ChemMedChem. 2024;19(24) doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202400495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardaneh P., Pirhadi S., Mohabbati M., Khoshneviszadeh M., Rezaei Z., Saso L., et al. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of 1,4-naphthoquinone- 1,2,3-triazole hybrids as new anticancer agents with multi-kinase inhibitory activity. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):6639. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-87483-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leechaisit R., Mahalapbutr P., Suriya U., Prachayasittikul V., Prachayasittikul S., Ruchirawat S., et al. Novel naphthoquinones as potent aromatase inhibitors: synthesis, anticancer, and in silico studies. J Mol Struct. 2024;1316 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efeoglu C., Serttas R., Demir B., Sahin E., Yabalak E., Seferoglu N., et al. 1,4-naphthoquinone thiazoles: synthesis, crystal structure, anti-proliferative activity, and inverse molecular docking study. J Mol Struct. 2025;1322 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman M.M., Islam M.R., Akash S., Shohag S., Ahmed L., Supti F.A., et al. Naphthoquinones and derivatives as potential anticancer agents: an updated review. Chem Biol Inter. 2022;368 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belger C., Abrahams C., Imamdin A., Lecour S. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and risk factors. Int J Heart. 2024;Vasc 50 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2023.101332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Malky H.S., Al Harthi S.E., Osman A.M. Major obstacles to doxorubicin therapy: cardiotoxicity and drug resistance. J Oncol Pharm Pr. 2020;26(2):434–444. doi: 10.1177/1078155219877931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]