Abstract

Dissolved organic matter (DOM) is a key determinant of heavy metal fate in aquatic environments, influencing their mobility, toxicity, and bioavailability. Derived from natural sources such as soil and vegetation decomposition, natural DOM (N-DOM) typically features humic-like substances with abundant oxygen-containing functional groups that stabilize heavy metals through complexation. However, microplastic-derived DOM (MP-DOM), increasingly prevalent due to plastic degradation, may interact differently with heavy metals, potentially exacerbating environmental risks amid rising plastic pollution. Yet, how heavy metals drive molecular transformations in MP-DOM versus N-DOM remains unclear, hindering accurate pollution assessments. Here, we compare interactions between N-DOM and MP-DOM with cadmium, chromium (Cr), copper, and lead from both fluorescence and molecular perspectives. Our results show that N-DOM, dominated by humic-like substances (46.0–57.3 %), lignin-like (55.0–64.9 %), and tannin-like (10.1–17.6 %) compounds, forms more stable heavy metal complexes via carboxyl, phenolic hydroxyl, and ether groups than MP-DOM. By contrast, MP-DOM—enriched in protein/phenolic-like substances (13.8–24.0 %), condensed aromatic (12.1–28.5 %), and protein/aliphatic-like (8.6–12.4 %) compounds—yields less stable complexes and is highly susceptible to Cr-induced oxidation. Mass-difference network analysis and density functional theory calculations further reveal that both DOM types undergo heavy-metal-triggered decarboxylation and dealkylation, but N-DOM retains complex structures, whereas MP-DOM degrades into smaller, hazardous molecules such as phenol and benzene. This study underscores the potential for heavy metals to exacerbate the ecological risks associated with the transformation of MP-DOM, providing crucial insights to inform global risk assessment and management strategies in contaminated waters where plastic and metal pollution co-occur.

Keywords: Dissolved organic matter, Microplastic, Heavy metal, Complexation, Molecular transformation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Heavy metals form more stable complexes with natural DOM (N-DOM) than with microplastic-derived DOM (MP-DOM).

-

•

MP-DOM exhibits higher reactivity and susceptibility to oxidation by chromium, yielding unstable metal complexes.

-

•

N-DOM compounds maintain complex spatial structures post-interaction with heavy metals, limiting degradation.

-

•

MP-DOM degrades into smaller, potentially hazardous molecules (e.g., phenol, benzene) upon heavy metal binding.

-

•

Heavy metals pose amplified environmental risks via MP-DOM's oxidative breakdown and enhanced pollutant mobility.

1. Introduction

Human activities such as mining, the use of fertilizers and pesticides, as well as urban and industrial activities, result in the substantial release of heavy metals (HMs) into rivers, lakes, and oceans through rainfall, sewage discharge, and surface runoff [1,2]. Currently, aquatic environments worldwide are facing significant contamination issues related to HMs, with chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) being among the most prominent. Statistically, the Niger River in Nigeria contains concentrations of 50, 30, and 2080 μg L−1 for Cd, Pb, and Cr, respectively, along with 1258 μg L−1 for Cu in the San Sebastian Canal [3,4]. In China, the Wei River, the largest tributary of the Yellow River, demonstrates similar trends, with reported concentrations of 1.2–9.5, 0.1–0.5, 2.4–10.1, and 0.5–7.0 μg L−1 for Cr, Cd, Cu, and Pb, respectively [5]. In some watersheds more severely impacted by urbanization or industrialization, HM concentrations may be five-to ten-fold higher than these reported values [6]. The presence of HMs in aquatic systems poses significant risks to human potable water supplies and food security [7]. However, the migration and ultimate deposition of these metals is intricately linked to the presence of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in the environment [8]. Therefore, understanding the complex interactions between HMs and DOM is crucial for developing effective strategies to remediate and control HM contamination.

DOM is recognized as one of the most chemically active constituents in natural ecosystems [9,10]. Its surface functional groups (e.g., phenolic, carboxylic, and carbonyl groups) facilitate complexation with various heavy metal ions, thereby playing a critical role in determining the migration, transformation, and fate of metals in the environment [11,12]. Natural DOM (N-DOM), the most abundant and widely distributed form of DOM, primarily originates from the decomposition of terrestrial vegetation, soil leachates, and microbial metabolism in ecological environments [13]. N-DOM comprises a complex array of organic compounds, including humic substances, fulvic acids, lignin derivatives, and lipids. These components contribute to N-DOM's rich diversity of surface functional groups and intricate molecular composition, thereby enhancing its capacity for strong complexation and stabilization with HMs [10,14,15]. Research has shown that humic-like and fulvic-like fluorescent substances within N-DOM have a strong affinity for metal ions [16,17]. However, with the widespread use of plastic products, an increasing amount of microplastic-derived DOM (MP-DOM) is entering the environment through the release of microplastics (MPs). According to the literature, products manufactured from conventional petroleum-derived polymers are widely utilized, with polyethylene (PE) accounting for approximately 36 %, polypropylene (PP) for 21 %, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) for 12 % [18]. Due to their inherent resistance to degradation, waste generated from these plastic items persists in the environment for extended periods [19]. Under the influence of factors such as hydrodynamic turbulence and ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, MP-DOM is continuously released into aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [20]. According to statistics, in some regions, MP-DOM already constitutes 10 % of the DOM at the ocean surface [21]. This proportion indicates that MP-DOM is emerging as a significant fraction of aquatic DOM, with potential implications for the transport and fate of contaminants in surface waters. Compared to N-DOM, MP-DOM can accumulate in surface waters at high concentrations and may surpass N-DOM to become the predominant type of DOM in regions heavily polluted by MP composites [22,23]. Although existing studies have suggested that MP-DOM exhibits HM reactivity similar to that of N-DOM [24], there is still no consensus on the differences in chemical structure and properties between N-DOM and MP-DOM, let alone a comparison of their reactivity with HMs in the environment.

MP-DOM refers to the DOM released from MPs upon their interaction with aqueous environments, with leaching conditions critically influencing its environmental behavior [25]. Among these conditions, UV radiation plays a crucial role in inducing chain scission reactions in MPs; thus, it is commonly used to simulate the natural conditions for MP-DOM leaching [26]. Extensive research indicates that both the intensity and duration of UV irradiation significantly influence MP-DOM concentrations [27]. In freshwater, MP-DOM concentrations under UV irradiation are 66.5–80.0 times higher than those under non-UV conditions, with dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations reaching 11.1–15.5 mg DOC per g MP [24,28]. Furthermore, UV-irradiated MP-DOM contains higher proportions of oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., carbonyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups) and more fluorescent substances (e.g., protein-like and humic-like substances) [29]. These alterations in characteristics may substantially influence the reactivity of MP-DOM with HMs. Importantly, MP-DOM comprises not only polymer monomers resulting from the scission of MPs but also various additives including dibutyl phthalate, bisphenol A, and ketones [30]. Consequently, MP-DOM contains numerous unstable compounds susceptible to microbial degradation and oxidation, leading to the formation of smaller molecules with enhanced mobility [31]. However, the transformation mechanisms of MP-DOM's organic components in environmental systems remain poorly understood, especially under co-occurring HM and MP contamination. Thus, elucidating the pathways of organic transformation in MP-DOM facilitated by HM interactions is crucial for understanding the complexities associated with the environmental risks of HM and MP-DOM coexistence.

Currently, the most widely used techniques for probing the characteristics of metal–DOM interactions include ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR), synchronous fluorescence (SF), and excitation–emission matrix (EEM) spectroscopies [32,33]. Numerous studies have combined EEM spectroscopy with parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC), obtaining EEM-PARAFAC to qualitatively and quantitatively describe the binding behaviors of fluorescent components during the quenching processes of N-DOM and MP-DOM via HMs [32,34]. However, relying solely on EEM-PARAFAC might oversimplify the fluorescence into a limited number of components, thus leading to a reductionist chemical analysis [35]. In addition, while two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy (2D-COS) combined with SF and FTIR spectroscopies enables the exploration of the dynamic sequence of fluorescence and functional groups involved in DOM–metal binding, it lacks compound-specific resolution power [36]. Therefore, molecular-level insights are crucial for comprehensively analyzing the interactions between DOM and HMs. In recent years, Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS) has been extensively applied for DOM characterization, addressing the relationship between metal complexation-induced changes in DOM fluorescence and FT-ICR-MS-derived molecular formulas of DOM [[37], [38], [39]]. While FT-ICR-MS provides rich qualitative molecular data, it typically cannot resolve the structural isomers required for the identification of individual molecular components [40]. The advent of liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) has significantly enhanced the analysis of structurally similar molecules by compensating for the limitations of FT-ICR-MS, which offers high resolution and precise mass-determination capabilities. Additionally, mass-difference network analysis can precisely identify mass changes of compounds based on FT-ICR-MS data. When combined with molecular reaction network analysis, mass-difference network analysis can reveal molecular transformation pathways of DOM [41]. Coupling multiple mass spectrometry techniques with density functional theory (DFT) calculations enables more accurate predictions of molecular transformations in DOM under HM stress.

In this study, a comprehensive comparative analysis at the fluorescence and molecular levels was conducted using various spectroscopic and mass spectrometric techniques, including FT-ICR-MS and LC–MS/MS, combined with 2D-COS analysis, mass-difference network analysis, and DFT calculations, to investigate the interactions and transformation mechanisms of N-DOM and MP-DOM with HMs. The main objectives were as follows: (1) characterizing the fluorescent features and molecular components of N-DOM (DOM from water, soil, and sediment) and MP-DOM (DOM from PP, PE, and PVC); (2) qualitatively and quantitatively analyzing the interaction characteristics between different fluorescent components in DOM and HMs (Cd, Cr, Cu, and Pb); and (3) elucidating the binding mechanisms and potential transformation pathways of N-DOM and MP-DOM with HMs at the molecular level.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation and collection of DOMs

N-DOM samples were collected from the Wei River Wetland Park in Shaanxi Province, China, in July 2023. The collection encompassed river water (0.5 m below the surface), surface soil (0–20 cm depth), and sediment (0–20 cm above the riverbed), and was conducted at three distinct sites along the river. Samples from each site were meticulously mixed, packed in brown glass bottles, and swiftly transported to the laboratory. Three types of N-DOM were ultimately obtained: SY-DOM (river water, 8.1 mg L−1), CJ-DOM (sediment, 10.2 mg L−1), and TR-DOM (soil, 30.2 mg L−1), with detailed extraction methods discussed in Supplementary Text S1.1.

Widely used environmental polymers, such as PP, PE, and PVC, were utilized for MP-DOM production. Spherical MPs (500 nm in diameter) were sourced from Jiangsu Hai'an Zhichuan Technology Co., Ltd. Prior to aging, impurities were removed through repeated washing with ethanol and water, after which the MPs were dispersed via ultrasonication in ultrapure water to achieve a concentration of 5 g L−1. A simulated 15-day UV aging test was conducted in the constructed UV aging chambers equipped with four 100-W UV lamps. Finally, three types of MP-DOM were obtained: PP-DOM (891.1 mg L−1), PE-DOM (724.8 mg L−1), and PVC-DOM (201.6 mg L−1). The high concentrations of MP-DOM are likely attributable to the intense UV exposure used in this study, consistent with the findings reported by Liu et al. [42]. Specific experimental details and preparation methods are described in Supplementary Text S1.2.

2.2. Quenching titration experiment

The extracted N-DOM and MP-DOM solutions were accurately diluted to 10 and 50 mg C L−1, respectively. Notably, the HM quenching experiments for N-DOM and MP-DOM were completely independent. For the titration of DOM using HMs, separate experiments were conducted for each metal ion (Cd(NO3)2, Pb(NO3)2, Cu(NO3)2, and K2Cr2O7). During the titration of N-DOM, 0, 200, 400, 800, 1200, 1600, and 2000 μL of 5 mmol L−1 metal reserve solutions were added to 50 mL of N-DOM solutions (SY-DOM, CJ-DOM, and TR-DOM) in brown sealed vials. This protocol established a series of N-DOM samples with HM concentrations ranging from 0 to 200 μmol L−1, a range commonly used in previous studies to assess DOM-HM interactions [34,43,44]. Although the maximum concentration set is relatively high, it can represent HM levels found in some mine tailings water, industrial wastewater, and sewage, facilitating the evaluation of DOM's response under varying degrees of pollution stress [45,46]. Alternatively, MP-DOM solutions were intentionally set at higher concentrations (50 mg C L−1) to facilitate more effective observation of their reactions with HMs. These concentrations were designed to simulate scenarios involving surface water, groundwater, or industrial wastewater heavily contaminated with MPs [47,48]. To maintain consistency with N-DOM, the HM concentrations in MP-DOM were adjusted to five times the original levels, thereby neutralizing the impact of concentration variability. Consequently, the same volume gradient of 25 mmol L−1 metal reserve solutions was added dropwise to 50 mL of MP-DOM solutions (PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM) in brown sealed vials. A series of MP-DOM titration samples with HM concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 μmol L−1 were produced. In total, 504 samples from both N-DOM and MP-DOM groups were shaken in the dark at pH 7.0 and 25 °C for 24 h to ensure that the reaction reached equilibrium [49]. Thereafter, 10 mL of the quenched solution was filtered through a 0.22-μm cellulose acetate membrane and immediately subjected to UV–vis, EEM, and SF measurements. The remaining samples were freeze-dried at −80 °C for subsequent FTIR analysis.

2.3. Analytical measurements

To elucidate the impact of UV-induced aging on the surface characteristics and chemical properties of MPs, an analytical approach using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Sigma 300, ZEISS, Germany) and FTIR spectrometry (Vertex 70, Bruker, Germany) was employed. DOC concentrations of the N-DOM and MP-DOM samples were determined using a TOC analyzer (TOC-L, Shimadzu, Japan). FTIR, UV–vis, EEM, and SF analyses of N-DOM and MP-DOM were conducted before and after titration with HMs at varying concentration gradients. The UV–vis measurements were performed using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Japan). The EEM and SF spectra were analyzed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F90 pro, Lengguang Technology, China). Detailed operational procedures and parameters for these characterizations are provided in Supplementary Text S1.3.

To ensure the detection of subtle compositional changes, the compound compositions of the N-DOM and MP-DOM samples before and after quenching with the highest concentration gradient of HMs were analyzed via FT-ICR-MS (Bruker SolariX, Bremen, Germany). Meanwhile, LC–MS/MS analyses were performed using an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography system (Vanquish, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide column (2.1 mm × 50.0 mm, 1.7 μm) coupled with the Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer (Orbitrap MS, Thermo). Specific detection parameters and analytical methods are provided in Supplementary Text S1.4.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. PARAFAC analysis and complexation modeling

PARAFAC modeling was conducted using MATLAB R2022a and the DOM Flour Toolkit (www.models.life.ku.dk) following the methodology outlined by Stedmon and Bro [50]. Unconstrained PARAFAC modeling with two to seven components was separately performed on 252 EEM results for N-DOM and MP-DOM obtained from the HM quenching titration experiments. The final component scores were determined through residual analysis, split-half analysis, and examination of the explained variance percentages. The relative content of each fraction was estimated based on the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax; R.U.) of the fractions identified within the samples.

The analysis of the binding interactions between HMs and fluorescent components employed the modified Stern–Volmer equation, a widely accepted approach for calculating the parameters associated with the binding behavior of DOM and HMs, as evidenced in previous studies [24,51]:

| (1) |

where F and F0 denote fluorescence values of Cd2+, Pb2+, Cu2+, and Cr6+ at concentrations of 0 and CM (concentration of added HMs; mol L−1), respectively; KM indicates the effective quenching constant, calculated based on the slope of the F0/(F0 − F) versus 1/CM curve; and f denotes the fraction of fluorophore involved in the binding of HMs [52,53].

2.4.2. Other analysis methods

2D-COS analyses were performed following the method of Noda and Ozaki, with specific Noda rules detailed in Supplementary Text S1.6 [54]. Details on the mass-difference network analysis and DFT calculations are provided in Supplementary Text S1.7 and Text S1.8, respectively [[55], [56], [57], [58]].

2.5. Statistical analyses

To ensure data reliability, triplicate analyses were conducted for each concentration level in the titration experiments. The standard deviation derived from these triplicates was maintained below 5 %. Calculations of EEM and the PARAFAC model were conducted using MATLAB R2022a software, while 2D-COS analyses were performed using 2Dshige software. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software. Mass-difference network analysis was conducted using Python 3.12, and visualized in Gephi 10.1.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characteristics of N-DOM and MP-DOM

3.1.1. Characterizations of aged MPs and leaching of MP-DOM

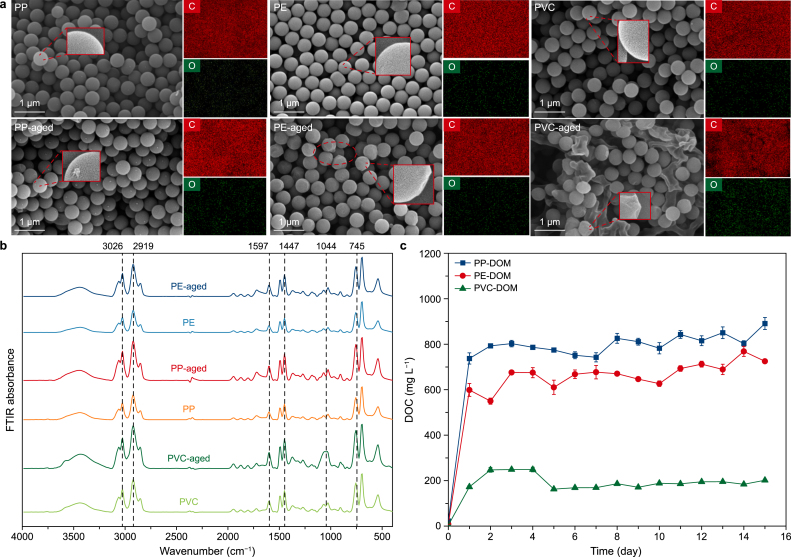

To investigate the aging dynamics of MPs (PP, PE, and PVC) under simulated conditions, the surface characteristics of MPs and the release of MP-DOM were monitored. Aging markedly enhanced surface oxidation and accelerated MP-DOM release across all types of MPs. In particular, the SEM results demonstrated varying degrees of roughness, increased cracks, and structural deformation in PP, PE, and PVC (Fig. 1a). EDS analyses corroborated these changes, showing an enhancement in surface oxygen content (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S1). FTIR spectroscopy further validated oxidative aging through intensified absorption peaks at 1597 cm−1, corresponding to C=O stretching vibrations (Fig. 1b). These oxidation signatures, recognized as key aging indicators in prior studies, were most pronounced in PVC [59]. Additionally, the EEM spectroscopy results indicated a time-dependent accumulation of humic-like fluorescent components in MP-DOM, particularly in PVC-DOM (Supplementary Fig. S2). The TOC of PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM in the simulated aging process increased significantly from initial concentrations of 22.5 ± 1.0, 8.1 ± 1.0, and 3.6 ± 0.4 to 891.1 ± 26.4, 724.8 ± 5.8, and 201.6 ± 2.1 mg L−1, respectively (Fig. 1c). Collectively, these multi-methodological findings confirmed that the simulated aging conditions effectively induced surface modification of MPs and generated representative MP-DOM.

Fig. 1.

a, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image and elemental mapping of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) elements. The red dashed circle indicates the local area of the microplastic selected for magnified SEM imaging. b, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra. The vertical dashed lines represent different infrared wavelengths. c, Variation in dissolved organic carbon (DOC) of microplastic-dissolved organic matter (MP-DOM) during the ultraviolet aging of polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microplastics. Here, aged PP-DOM (from polypropylene), aged PE-DOM (from polyethylene), and aged PVC-DOM (from polyvinyl chloride) represent the dissolved organic matter extracted from ultraviolet-aged microplastics.

3.1.2. Spectral characteristics of N-DOM and MP-DOM

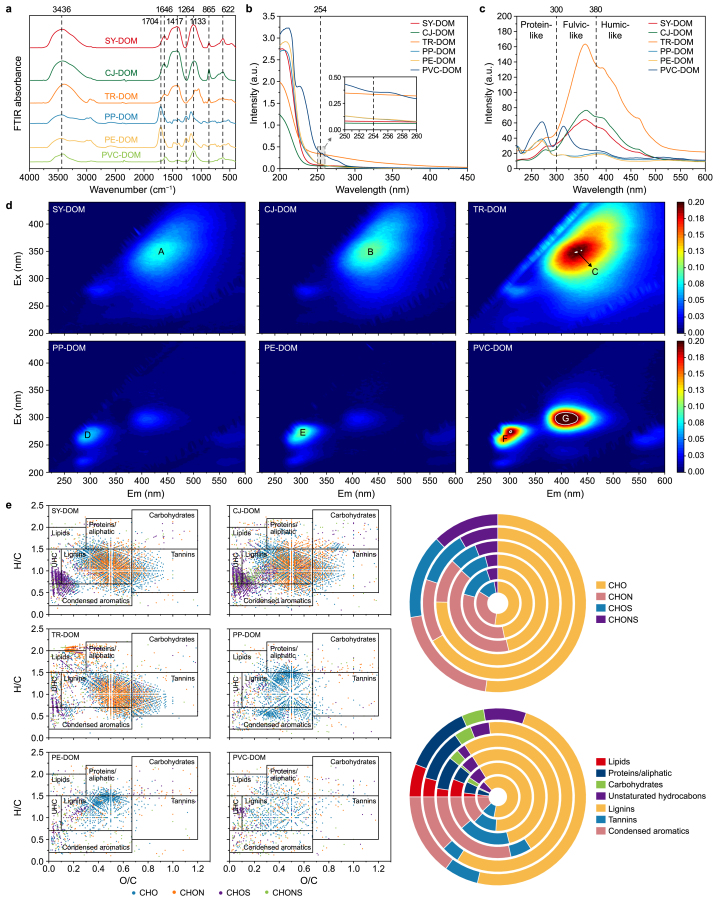

The fluorescence characteristics and chemical properties of DOM are directly related to its reactivity with HMs [17]. However, the differences in properties between N-DOM and MP-DOM remain unclear. To address this gap, we comparatively analyzed their spectral features. UV–vis spectroscopy revealed that the MP-DOM samples (PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM) exhibited higher absorbance in the range of 200–250 nm compared to the N-DOM samples (SY-DOM, CJ-DOM, and TR-DOM) (Fig. 2b). These results indicated a greater abundance of chromophoric organic compounds, consistent with the higher DOC concentrations observed in the MP-DOM samples [60]. Note that the UV absorbance of PVC-DOM was exceptionally high, despite its lower DOC concentration compared to PP-DOM and PE-DOM. This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique Cl−-mediated pathway of PVC during UV aging, leading to the formation of distinctive degradation products such as chlorinated aromatic compounds or conjugated polyene structures, which result in elevated UV absorbance [26,61]. Generally, SUV254 represents the degree of aromatization in DOM [33,62]. When normalized by DOC concentration, the SUV254 range for N-DOM was 0.5–1.1, higher than that for MP-DOM (0.01–0.2) (Supplementary Table S2). This suggested that N-DOM had a greater degree of aromaticity than MP-DOM, with TR-DOM showing the highest level of aromatization. The EEM results indicated that the fluorescence peaks (A, B, and C) of N-DOM primarily corresponded to humic-like substances (46.0–57.3 %). In contrast, the peaks (D, F, and H) of MP-DOM primarily represented protein-like/phenolic fluorescent substances (13.8–24.0 %) and peaks (E, G, and I) corresponded to humic-like substances (11.0–16.5 %) (Fig. 2d) [51,63,64]. The presence of these two types of fluorescent substances in MP-DOM may be attributed to the release of specific additives from the MPs during UV aging, such as bisphenol A and diethylhexyl phthalate, which exhibit protein/phenolic-like and humic-like fluorescence characteristics, respectively [65,66]. In addition, the humification index (HIX) calculated from EEM provided more robust evidence of this. The HIX values for N-DOM (0.7–0.8) were significantly higher than those for MP-DOM (0.1–0.2) (Supplementary Table S2), indicating that the degree of humification in N-DOM was higher than that in MP-DOM. The SF results further demonstrated that the fluorescent components in N-DOM were primarily distributed in the fulvic-like (300–380 nm) and humic-like (380–600 nm) regions, whereas MP-DOM was primarily concentrated in the protein-like (220–300 nm) and fulvic-like (300–380 nm) fluorescence regions (Fig. 2c) [16]. The findings indicated that, compared to MP-DOM, N-DOM exhibited a higher degree of aromatization and humification.

Fig. 2.

Spectral and molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter (DOM). a, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra; b, Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra, with the inset showing a magnified view at 254 nm for the six types of DOMs; c, Synchronous fluorescence spectra; d, Excitation–emission matrix spectrograms, where the letters A–F denote the characteristic fluorescence peaks of the six types of DOMs; e, Van Krevelen diagrams of the compounds and the percentages of different molecular classes in the DOMs. The six types of DOMs include SY-DOM (from river water), CJ-DOM (from sediment), TR-DOM (from soil), PP-DOM (from polypropylene), PE-DOM (from polyethylene), and PVC-DOM (from polyvinyl chloride).

3.1.3. Molecular characterization of N-DOM and MP-DOM

To further understand the molecular differences between N-DOM and MP-DOM, we compared six types of DOM using FTIR spectroscopy and FT-ICR-MS (Fig. 2a–e). The FTIR spectra of N-DOM showed significantly higher peaks at 3436 cm−1 (O–H groups), 1417 cm−1 (COO−), and 1133 cm−1 (aliphatic C–OH) compared to MP-DOM. Conversely, MP-DOM exhibited a significantly higher peak at 1704 cm−1 (carboxyl C=O). These results suggested that N-DOM contained more phenolic hydroxyls, carboxyls, and ether bonds, while MP-DOM had a higher concentration of C=O bonds. Furthermore, proportions of different compound types in N-DOM and MP-DOM were identified based on previously conducted FT-ICR-MS classifications (Supplementary Text S1.5 and Table S3) [67]. N-DOM contained more lignin-like (55.0–64.9 %) and tannin-like (10.1–17.6 %) compounds than MP-DOM, while MP-DOM had higher proportions of condensed aromatics (12.1–28.5 %) and protein/aliphatic-like (8.6–12.4 %) compounds. The abundant presence of condensed aromatic compounds in MP-DOM is likely linked to the transformation of light stabilizers (such as benzotriazoles and benzophenones) under UV aging [68,69]. Additionally, the cyclization and aromatization of conjugated polyene structures formed following the dehydrochlorination (de-HCl) of PVC polymer chains may also contribute to the increased content of condensed aromatics in MP-DOM [70,71]. According to the literature, lignin-like and tannin-like compounds are rich in carboxylic acids, phenolic hydroxyls, and ether bonds, resulting in a strong capacity for binding metal ions. Similarly, phenolic compounds within condensed aromatic structures effectively bind with HMs [40,72]. The variations in fluorescence characteristics and molecular compositions between N-DOM and MP-DOM may lead to their differential reactions with HMs.

3.2. Fluorescence response behavior of DOM with HMs

3.2.1. Quenching behavior of fluorescent components in DOM with HMs

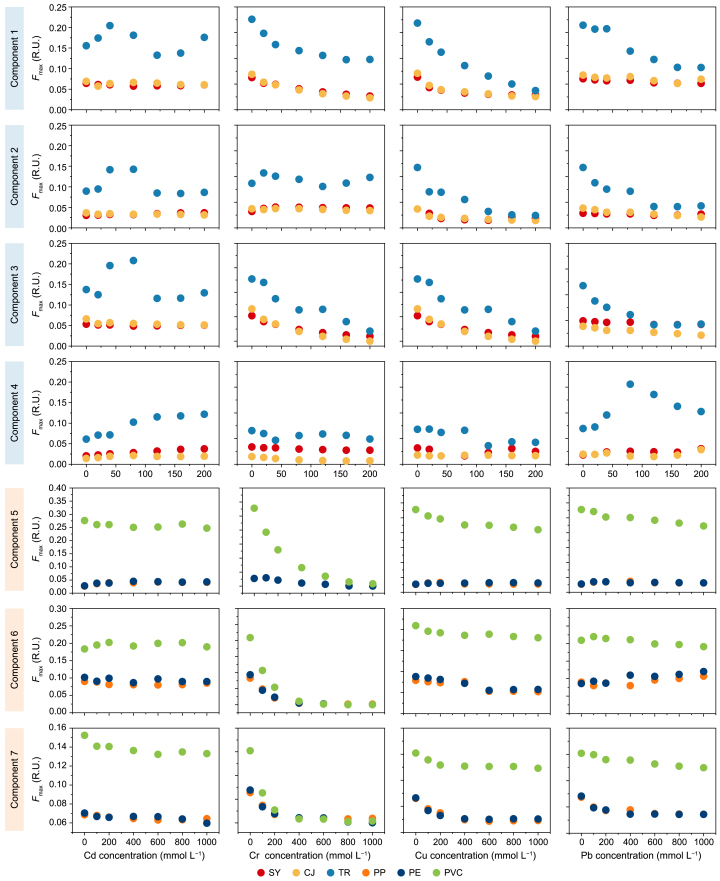

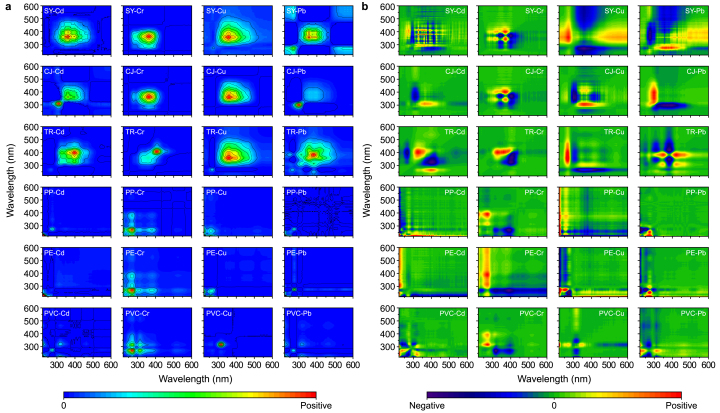

To distinguish between N-DOM and MP-DOM in terms of the fluorescent substances involved in interactions with HMs, we collected EEMs of N-DOM and MP-DOM before and after quenching by HMs at varying concentrations. Results from EEM-PARAFAC analysis indicated that fluorescence variations of N-DOM (C1–C4) and MP-DOM (C5–C7) were optimally described using a four- and three-component model, respectively, with core consistencies exceeding 90 % (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Table S4). The fluorescence quenching of N-DOM involved humic-like (C1), marine/surface water humic-like (C2), terrestrial humic-like (C3), and tyrosine-like protein (C4) substances, while that of MP-DOM was associated with marine/surface water humic-like (C5), tryptophan protein-like (C6), and petroleum hydrocarbon (C7) substances.

The variations in maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax) after quenching with HMs are shown (Fig. 3). For N-DOM, the extent of Fmax quenching of the four fluorescent components followed the order of C3 (53.9 %) > C1 (41.9 %) > C2 (36.8 %) > C4 (23.3 %). For MP-DOM, the extent of Fmax quenching of the fluorescent components followed the order of C5 (56.4 %) > C7 (48.1 %) > C6 (23.3 %). The results demonstrated that humic-like fluorescent components in both N-DOM and MP-DOM exhibited the most pronounced quenching effects. When examining the quenching behavior with four HMs, the Fmax quenching of the fluorescent components in N-DOM generally followed the order of Cu (54.0 %) > Cr (53.2 %) > Pb (32.3 %) > Cd (8.7 %); the order was Cr (96.0 %) > Cu (39.0 %) > Pb (37.4 %) > Cd (10.1 %) for MP-DOM. This difference in quenching effects between HMs can be ascribed to compositional differences between N-DOM and MP-DOM and the distinct properties of HMs. On the one hand, the lignin-like and tannin-like substances, which are abundant in N-DOM, contain more aromatic structures and phenolic and carboxylic groups. On the other hand, the non-negligible protein/aliphatic-like substances in MP-DOM are prone to oxidation and subsequent cleavage into “lower molecular weight” compounds. Additionally, Cu is more likely to form stable complexes with phenolic and carboxylic groups in humic-like substances in DOM because of its smaller radius and paramagnetic properties. The high valence state of Cr results in strong oxidizing properties in addition to its complexation ability, often leading to the oxidization of protein-like substances in DOM [44,[73], [74], [75]].

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence quenching curves of dissolved organic matter (DOM) components titrated with cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb). Components 1–4 correspond to the four fluorescent constituents of natural dissolved organic matter, namely SY-DOM, CJ-DOM, and TR-DOM. Components 5–7 represent the three fluorescent constituents of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter, including PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM.

3.2.2. Comparison of binding parameters of fluorescent components in DOM with HMs

To further evaluate and compare the stabilities of complexes formed between different HMs and fluorescent components in N-DOM and MP-DOM, the modified Stern–Volmer equation was employed to fit and calculate the conditional stability constant (LogK) based on EEM analyses (Supplementary Fig. S4; Table 1). The LogK values for N-DOM's fluorescent components, combined with Cr, Cu, and Pb, were 4.1–4.3, 3.7–4.9, and 3.8–4.6, respectively, and the corresponding values for MP-DOM were 2.6–4.1, 3.5–4.1, and 2.2–4.1. The results indicated that the stability of complexes formed between the fluorescent components of N-DOM and HMs was higher than that of the complexes formed between the fluorescent components of MP-DOM and HMs. Cd did not fit the model for any fluorescent component, consistent with the findings of Fan et al. [51] and Zhu et al. [36], indicating Cd's weak binding stability for fluorescent substances in both N-DOM and MP-DOM. Notably, the same fluorescent components from different types of DOM exhibited variations in LogK concerning complexation with Cr, Cu, and Pb. This variation is hypothesized to be related to the degree of humification of DOM from different sources. Highly humified DOM can provide numerous binding sites and enhance spatial hindrance, thereby limiting the dissociation of metal ions and forming tighter configurations—increasing the stability of its complexes with HMs [51]. To test this hypothesis, we performed linear fitting of HIX values of six types of DOM against their LogK values for Cr, Cu, and Pb. The results confirmed our hypothesis, indicating a significant positive correlation (P < 0.05) between HIX and LogK (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Table 1.

Binding parameters of N-DOM and MP-DOM fluorescent components to heavy metals calculated by modified Stern–Volmer modeling.

| N-DOM |

MP-DOM |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | PARAFAC components | fa | LogKb | Rc | Type | PARAFAC components | fa | LogKb | Rc |

| SY + Cr | C1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.894 | PP + Cr | C5 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.979 |

| C2 | – | – | – | C6 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.939 | ||

| C3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 0.984 | C7 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 0.914 | ||

| SY + Cu | C1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 0.989 | PP + Cu | C5 | – | – | – |

| C2 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.980 | C6 | – | – | – | ||

| C3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 0.982 | C7 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 0.976 | ||

| SY + Pb | C1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 0.992 | PP + Pb | C5 | – | – | – |

| C2 | – | – | – | C6 | – | – | – | ||

| C3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 0.990 | C7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.989 | ||

| CJ + Cr | C1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 0.960 | PE + Cr | C5 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.949 |

| C2 | – | – | – | C6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 0.986 | ||

| C3 | – | – | – | C7 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.979 | ||

| CJ + Cu | C1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 0.982 | PE + Cu | C5 | – | – | – |

| C2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 0.920 | C6 | – | – | – | ||

| C3 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 0.898 | C7 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.960 | ||

| CJ + Pb | C1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 0.785 | PE + Pb | C5 | – | – | – |

| C2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 0.987 | C6 | – | – | – | ||

| C3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0.949 | C7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.956 | ||

| TR + Cr | C1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 0.980 | PVC + Cr | C5 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.995 |

| C2 | – | – | – | C6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 0.979 | ||

| C3 | – | – | – | C7 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 0.964 | ||

| TR + Cu | C1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 0.994 | PVC + Cu | C5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 0.985 |

| C2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 0.926 | C6 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 0.899 | ||

| C3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 0.992 | C7 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 0.902 | ||

| TR + Pb | C1 | – | – | – | PVC + Pb | C5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.999 |

| C2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 0.978 | C6 | – | – | – | ||

| C3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 0.969 | C7 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.951 | ||

-: Failed to be modeled.

Fraction of fluorophore involved in the binding of heavy metals.

Conditional stability constants.

Quenching model fitting correlation coefficients.

As for the fluorescent components, humic-like substances in N-DOM were found to form the most stable complexes with HMs, while C7 in MP-DOM exhibited the strongest binding stability with HMs. Protein-like fluorescent substances (C4 and C6) exhibited relatively weak stability with HMs in N-DOM and MP-DOM. Particularly, the C1 component in N-DOM demonstrated a strong binding capacity for Cr, while C2 and C3 exhibited higher binding coefficients for Cu and Pb, respectively. Notably, fits of C7 with Cr, Cu, and Pb in all three MP-DOM types were successful, and LogK values were significantly higher than those for C5 and C6. Despite the limited research on the composition of C7, these MP-derived petroleum hydrocarbons exhibited high stability in their complexes with HMs. According to previous studies, these petroleum hydrocarbons are rich in aromatic ring structures and typically possess conjugated π-electron systems, providing multiple binding sites for HMs [76]. Hence, the “petroleum hydrocarbon” substances are crucial fluorescent components of MP-DOM, playing a vital role in the stable complexation of HMs, which may affect the environmental fate and transformation of HMs.

3.2.3. Fluorescent response of DOM to HMs identified via 2D-SF-COS

To investigate the dynamics of HM-induced fluorescence sequences in N-DOM and MP-DOM, 2D-COS analysis was performed on SF spectra with varying concentrations of Cd, Cr, Cu, and Pb. In SF synchronous spectra (Fig. 4a), the self-correlation peaks of N-DOM with HMs were observed at 262–302 nm (protein-like substances, PL), 360–380 nm (fulvic-like substances, FL), and 382–410 nm (humic-like substances, HL). For MP-DOM, the peaks appeared at 223–230 nm (tyrosine protein-like substances, SL), 260–270 nm (tryptophan protein-like substances, TL), and 315–370 nm (FL). All self-correlation peaks were positively correlated, indicating a consistent response of fluorescent substances in both N-DOM and MP-DOM. In SF asynchronous spectra (Fig. 4b), the interactions of N-DOMs (SY-DOM, CJ-DOM, and TR-DOM) with Cd showed negative cross-peaks at 265–305 nm/360–410 nm, positive cross-peaks at 380–450 nm/265–305 nm, and negative cross-peaks at 380–450 nm/360–410 nm, respectively. According to Noda's rules [54], the order of fluorescence peak changes was 360–410 nm > 380–450 nm > 265–305 nm, indicating that the binding sequence of N-DOM with Cd was FL > HL > PL. Similarly, the binding sequence of N-DOM with Cr was PL > FL > HL, that with Cu was PL > HL > FL, and that with Pb was HL > PL > FL. The findings revealed that protein-like substances in N-DOM preferentially interacted with Cr and Cu, while fulvic-like and humic-like substances were more sensitive to Cd and Pb, respectively. For MP-DOMs (PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM), the specificity toward HMs was less pronounced. Instead, the response order of their fluorescent components was significantly influenced by the type of DOM. For PE-DOM and PP-DOM, the response sequence to HMs was SL > TL > FL, while for PVC-DOM, the order was TL > SL > FL. The binding sequence of HMs indicated that protein-like substances exhibited higher sensitivity to Cr and Cu, with a higher binding priority compared to humic substances. This is attributable to the fact that protein-like substances typically comprise highly reactive and relatively unstable protein/aliphatic-like compounds, with a reduced capacity to form stable complexes with HMs. This indirectly represents the high reactivity of MP-DOM with HMs and the instability of its complexes.

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional synchronous fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: a, synchronous spectra; b, asynchronous spectra.

3.3. Exploration of the reaction behavior of DOM with HMs at the molecular level

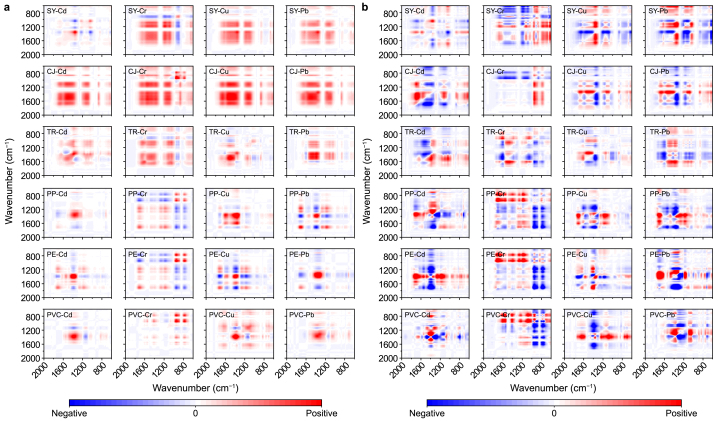

3.3.1. 2D-FTIR-COS

Previous studies have provided insights into the reactions of fluorescent substances in N-DOM and MP-DOM with HMs; however, these fluorescent substances represent only a small fraction of N-DOM and MP-DOM. Therefore, FTIR spectroscopy analyses of N-DOM and MP-DOM were performed before and after quenching with varying concentrations of HMs to comprehensively compare the molecular responses. N-DOM mainly exhibited a decrease in various oxygen-containing and aromatic groups, while MP-DOM showed not only a reduction in carboxyl groups but also increases in phenolic hydroxyl and aromatic groups. Detailed information is provided in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Text S2.2 and Fig. S7). This phenomenon was particularly pronounced in reactions with Cr, leading to the hypothesis that Cr may facilitate the oxidation and decomposition of compounds in MP-DOM, forming “smaller molecular weight” phenolic and aromatic substances.

Furthermore, 2D-COS analysis was conducted on the FTIR spectra (600–2000 cm−1) to determine the dynamic sequence of functional group alterations. In FTIR synchronous spectra (Fig. 5a) of N-DOM, the primary autocorrelation peaks were located at 1651 cm−1 (C=O), 1431 cm−1 (COO−), 1388 cm−1 (phenolic –OH), 1112 cm−1 (aliphatic –OH), 1037 cm−1 (polysaccharide C–O), and 937 cm−1 (aromatic C–C). All these autocorrelation peaks were positively correlated, indicating consistent changes in the functional groups within N-DOM. For MP-DOM, the main autocorrelation peaks were observed at 1704 cm−1 (carboxyl C=O), 1438 cm−1 (COO−), 1387 cm−1 (phenolic –OH), 1174 cm−1 (carboxylic –OH), 918 cm−1 (aromatic C–C), and 763 cm−1 (aromatic C–H). Peaks at 1387, 918, and 763 cm−1 showed positive correlations, while those at 1704, 1438, and 1174 cm−1 exhibited negative correlations, representing differing trends in functional group changes with increasing HM concentrations. From FTIR asynchronous spectra (Fig. 5b), based on Noda's rules, we concluded that the binding priorities of the polysaccharide C–O group with the four HMs were consistently high in SY-DOM and CJ-DOM. In TR-DOM, the C=O functional group was most sensitive to Cd, Cr, and Pb, while the polysaccharide C–O group preferentially bound to Cu. For MP-DOM, Cd and Pb primarily interacted with carboxylic –OH and carboxylic C=O groups, respectively; Cu preferentially bound with COO−; and Cr induced alterations in phenolic –OH groups. More details are provided (Supplementary Text S2.2). The results revealed that, in N-DOM, the ether and carbonyl groups were the first to change, whereas in MP-DOM, the carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups showed priority in their reactivity with HMs. Previous studies have reported that C–O functional groups (e.g., ethers) and C=O groups (e.g., carboxylic acids, ketones, and aldehydes) can coordinate with HM ions through the lone pairs of electrons on oxygen atoms [77]. These functional groups exhibited strong electron-donating properties, with carbonyl groups being particularly effective due to their significant electronegativity differences, which enabled the formation of relatively stable coordination bonds with HM ions.

Fig. 5.

Two-dimensional Fourier-transform infrared correlation spectroscopy: a, synchronous spectra; b, asynchronous spectra.

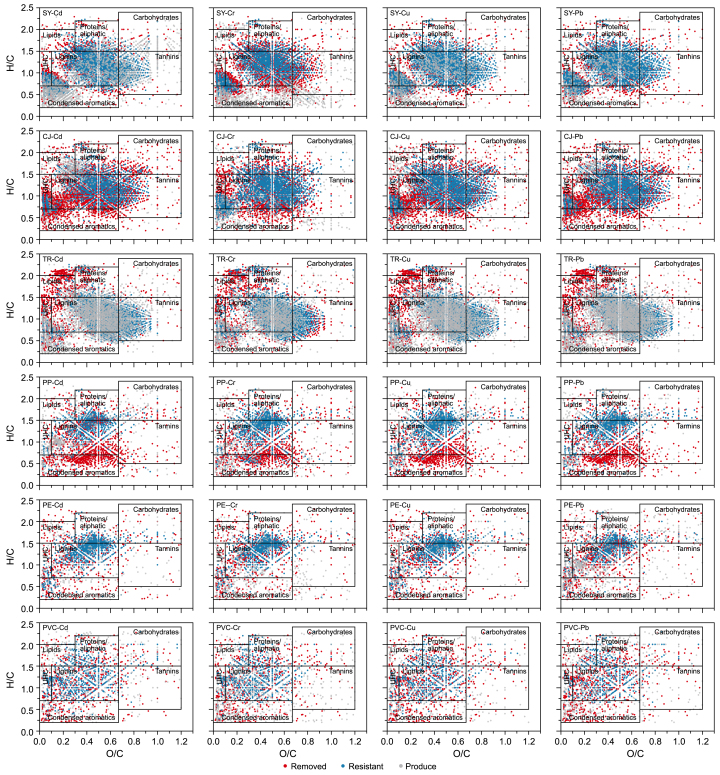

3.3.2. FT-ICR-MS

FT-ICR-MS data were obtained for N-DOM and MP-DOM before and after the addition of the highest concentrations of HMs to better investigate the compositional changes induced by HM incorporation. Following the classification rules proposed by Li et al. [78], compounds that were removed, produced, or remained after HM addition were identified and analyzed (Fig. 6). Lignin-like and condensed aromatic compounds in N-DOM and MP-DOM exhibited the most pronounced changes (Supplementary Fig. S8 and S9). This is attributable to the fact that aromatic carboxyl and phenolic groups in lignin-like and condensed aromatic compounds readily form bidentate structures with HM cations [79]. Significant differences in compound removal and production were observed depending on the source of DOM. Among N-DOMs, CJ-DOM exhibited the maximum removed compounds, while TR-DOM showed the maximum resistance and produced compounds. Among MP-DOMs, PP-DOM showed more removed and resistant compounds, whereas PVC-DOM exhibited more produced compounds. Molecular composition analysis revealed that TR-DOM was enriched in tannin-like compounds, while PVC-DOM contained more protein/lipid-like compounds (Supplementary Fig. S8 and S9). This suggested that upon HM addition, tannin-like compounds exhibited greater stability than protein- and lipid-like compounds. Furthermore, the addition of Cd and Cr primarily facilitated the removal and production of DOM compounds, while that of Cu and Pb facilitated the retention of DOM compounds. This phenomenon can be explained by the differing chemical properties between HMs. Cd, known for its high environmental mobility, tends to form unstable complexes with DOM, leading to compound removal. However, Cr(III) can form stable complexes with DOM; the strong oxidizing properties of Cr(VI) facilitate the removal of reducing substances and the breakdown of macromolecules into smaller compounds. In contrast, Cu and Pb, because of their strong complexation abilities, form stable complexes with DOM. These complexes are less likely to be removed and might have enhanced the stability of DOM, thus facilitating compound retention.

Fig. 6.

Removal (red), retention (blue), and production (grey) of compounds in van Krevelen diagrams for the six types of DOMs before and after quenching by Cd, Cr, Cu, and Pb. The six types of DOMs include SY-DOM, CJ-DOM, TR-DOM, PP-DOM, PE-DOM, and PVC-DOM.

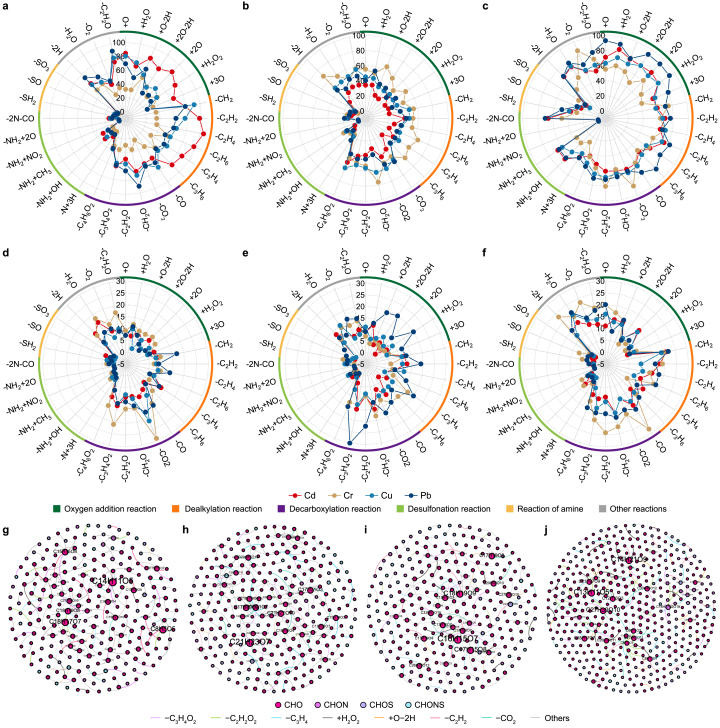

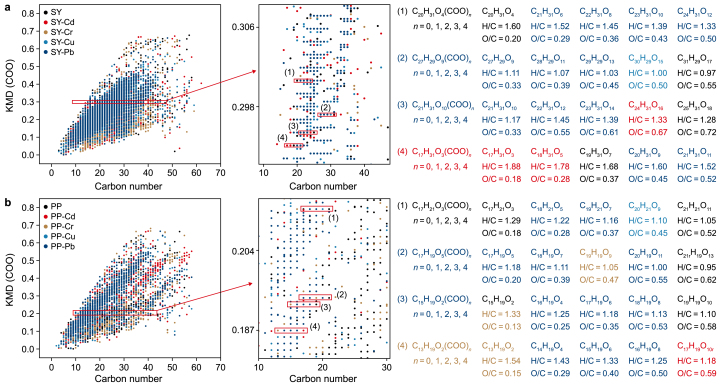

To clarify the reactions occurring in N-DOM and MP-DOM before and after the addition of HMs, a mass-difference analysis of 32 potential transformation reactions (Supplementary Table S6) was conducted to quantify the frequency of these reactions during DOM–HM interactions [75,80,81]. Radar plots (Fig. 8a–f) revealed that the interactions between DOM and HMs primarily involved decarboxylation reactions (–C4H6O2, –C2H2O, –CH2O, –CO2). Kendrick mass defect analysis (KMD(COO)) (Fig. 7a and b; Supplementary Fig. S10) further indicated that decarboxylation reactions in N-DOM predominantly involved compounds within the C17–C28 range, whereas mass discrepancies in MP-DOM primarily pertained to compounds in the C13–C22 range. In addition to decarboxylation reactions, distinct reaction patterns were observed for different metals: Cd, Cu, and Pb were predominantly associated with demethylation (–CH2) reactions, whereas Cr reactions were more commonly related to dehydrogenation (−2H) and oxygenation (+O). This finding provided robust evidence supporting the hypothesis that Cr(VI) induces oxidative reactions. Cd's strong electrophilicity facilitated its complexation with the oxygen-containing functional groups in DOM. This complexation altered the electronic configuration of DOM compounds, leading to polarization and cleavage of specific chemical bonds, thereby facilitating decarboxylation and dealkylation reactions [82]. Cu and Pb, characterized by their unpaired d-electrons, formed stable complexes with the oxygen-containing functional groups in organic molecules. These complexes reduced the electron density and altered the electronic structure of DOM compounds, resulting in bond dissociation. Furthermore, TR-DOM exhibited unique deamidation reactions (–2N–2O), likely because of the high abundance of organic nitrogen in soils. Metal ions seemed to coordinate with the oxygen or nitrogen atoms in amide bonds, altering the electronic structure of these bonds and often leading to amide hydrolysis. Comparing the reactions of each of N-DOM and MP-DOM with HMs, the former exhibited greater complexity. In the case of N-DOM, in addition to decarboxylation, nearly all types of reactions were observed, attributed to the diversity of its molecular composition and functional groups. However, MP-DOM exhibited a simpler and less stable composition, with reactions predominantly involving decarboxylation and oxidative dehydrogenation.

Fig. 8.

a–f, Radar plots of possible types of reactions between precursor-products reacted with Cd, Cr, Cu, and Pb for SY-DOM (a), CJ-DOM (b), TR-DOM (c), PP-DOM (d), PE-DOM (e), and PVC-DOM (f). g–j, The reactions of PE-DOM with Cd (g), Cr (h), Cu (i), and Pb (j), computational analysis of possible transformation pathway networks.

Fig. 7.

Kendrick mass defect of COO (KMD(COO)) versus carbon number and their scaled extended segments in the formula plots for the SY-DOM (a) and PP-DOM (b) compounds before and after quenching by Cd, Cr, Cu, and Pb.

To further elucidate the reasons behind the differences in the reaction pathways of various DOMs with HMs, Gephi was employed to visualize the mass-difference network analysis between precursors and products in DOM. The potential transformation pathways of different DOMs reacting with HMs are shown (Fig. 8g–j and Supplementary Fig. S11). From the reaction pathway diagrams for CJ-DOM with HMs, such as Cr, Cu, and Pb, common CHO precursor compounds, such as C23H19O13, can be identified. The primary reaction pathways involved decarboxylation (–C3H4O2, –C2H2O2, –CO2) and dealkylation (–C3H4). Similarly, CHO compounds such as C24H23O9, C25H13O4, and C9H13O in SY-DOM also underwent decarboxylation and dealkylation. A notable presence of CHOS compounds (C30H13O3S) as precursors led to dealkylation (–C3H4 and –CH2) and desulfonation reactions (–SH2 and –SO). Regarding TR-DOM, the primary precursors were CHON compounds such as C22H22NO13–C26H26NO13, and the main transformation pathways included dealkylation (–C2H6) and decarboxylation (–CO), alongside amine reactions (–NH2 + CH3) and other reactions (–H2O). In contrast to the reaction pathways of N-DOM, the MP-DOM pathways primarily involved the transformation of individual CHO precursor compounds. The main precursors for PE, PP, and PVC were C13H11O5–C21H23O7, C10H7O4–C23H11O10, and C9H15O4–C21H21O6, respectively. However, the transformations in MP-DOM were dominated by decarboxylation reactions (–CO, –CO2, and –C3H4O2), accompanied by dealkylation reactions primarily involving –C2H2. In addition, PVC-DOM contained some sulfur-containing compounds (C10H19O8S, C12H23O6S, and C25H11N2O4S), which primarily underwent dealkylation (–CH2 and –C2H6), decarboxylation (–CO, –CO2, and –C3H4O2), and desulfonation reactions (–SH2, –SO, and –SO3). Notably, the differences in reaction pathways between N-DOM and MP-DOM are primarily attributed to their distinct molecular structures and reaction mechanisms. N-DOM, particularly TR-DOM, largely comprises “high-molecular-weight” nitrogen-containing organic compounds, such as C26H26NO13, which frequently engage in complex interactions with HMs. These interactions typically facilitated the immobilization of HMs, thereby reducing their mobility. In contrast, MP-DOM generally comprises “low-molecular-weight” organic compounds, such as C9H15O4, which are more likely to migrate with HMs (e.g., Cd) in the environment or undergo oxidative degradation into “smaller-molecular-weight” compounds.

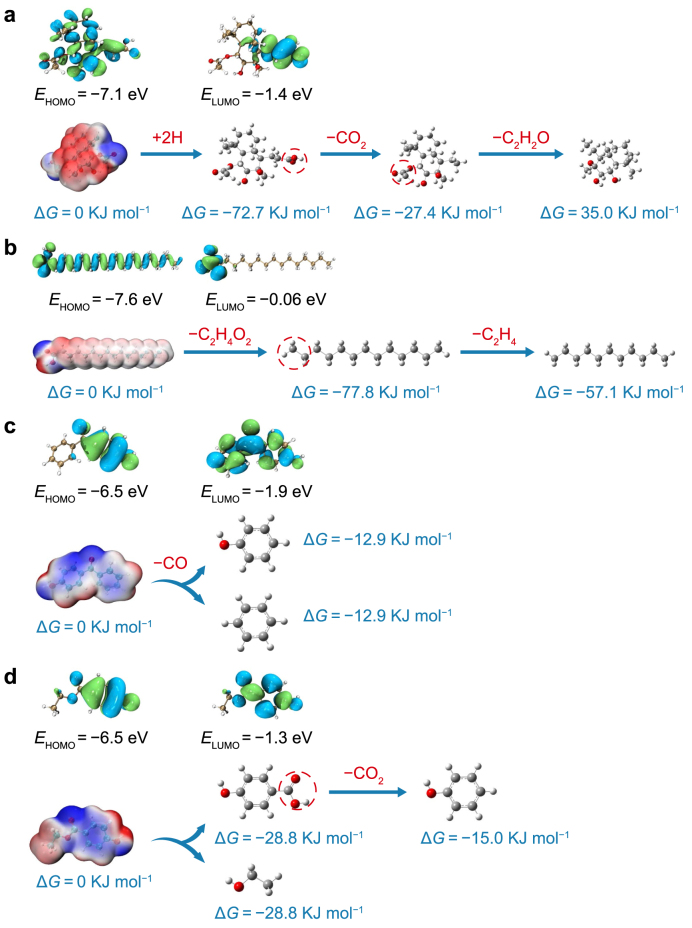

3.4. DFT calculations of typical compound transformations in DOM before and after reaction with HMs

To obtain more precise and reliable evidence, LC–MS/MS analysis was employed to elucidate the molecular structures of compounds in six types of DOM before and after HM addition. The chemical structures of the ten most abundant compounds in different DOM samples were identified through cross-validation of the LC–MS/MS identification results with theoretical molecular mass data from FT-ICR-MS (Supplementary Fig. S12). Four representative compounds were selected for DFT calculations and transformation-pathway predictions (Supplementary Text S1.8 and Fig. S13). DFT calculations revealed that 4-hydroxybenzophenone exhibited the highest energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO, −6.5 eV) and the lowest energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO, −1.9 eV) (Fig. 9c). Generally, a higher EHOMO value represents a stronger electron-donating ability and greater oxidative reactivity, while a lower ELUMO value implies a stronger electron-accepting capacity and reductive property [83]. This suggested that 4-hydroxybenzophenone possessed robust “dual” electron-donating and electron-accepting characteristics. Ethyl 4-hydroxybenzoate showed EHOMO and ELUMO values comparable to those of 4-hydroxybenzophenone (Fig. 9d), further underscoring the high reactivity and susceptibility of MP-DOM compounds toward redox reactions. In contrast, (E)-3-(4-acetyloxy-2,3-dihydroxy-2,5,5,8a-tetramethyl-3,4,4a, 6,7,8-hexahydro-1H-naphthalen-1-yl) prop-2-enoic acid and palmitic acid exhibited lower EHOMO values and higher ELUMO values, with the latter showing the highest ELUMO (−0.06 eV), indicating substantial stability (Fig. 9a and b). In terms of Gibbs free energy change (ΔG), the decarboxylation reactions of N-DOM and MP-DOM exhibited negative values, indicating that these reactions were thermodynamically spontaneous. (E)-3-(4-acetyloxy-2,3-dihydroxy-2,5,5,8a-tetramethyl-3,4,4a,6,7,8-hexahydro-1H-naphthalen-1-yl) prop-2-enoic acid in N-DOM maintained its complex stereochemical configuration following decarboxylation, resulting in the formation of 4-ethyl-2,3-dihydroxy-3,4a, 8,8-tetramethyldecahydronaphthalen-1-yl acetate (Fig. 9a). The subsequent –C2H2O reaction of this compound exhibited a positive ΔG of 35.0 kJ mol−1, indicating a thermodynamically unfavorable process. However, the ΔG value of the –C2H2O reaction of ethyl 4-hydroxybenzoate in MP-DOM was −28.8 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 9d). Note that the acetate hydrolysis (Fig. 9a, ΔG = 35.0 kJ mol−1) and ethyl ester hydrolysis (Fig. 9d, ΔG = −28.8 kJ mol−1) reactions exhibited contrasting ΔG values, although both design processes involve the formal transformation of a –C2H2O moiety. This discrepancy suggested that ΔG was determined by the global thermodynamic stability of the entire molecular system, rather than by localized alterations to functional groups. In particular, in the hydrolysis of 4-ethyl-2,3-dihydroxy-3,4a,8,8-tetramethyldecahydronaphthalen-1-yl acetate to its triol derivative (Fig. 9a), the positive ΔG indicated that the reactant retains greater thermodynamic stability than the product within this structurally constrained decahydronaphthalene framework. This unexpected endergonicity may arise from increased steric hindrance, unfavorable conformational changes in the triol product, or unique stabilizing interactions present in the acetate reactant within this particular structure [84,85]. Conversely, the hydrolysis of ethyl 4-hydroxybenzoate to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid was an exergonic process (Fig. 9d, ΔG < 0). This aligned with the typical behavior of many ester hydrolysis reactions, particularly when the resulting carboxylic acid (4-hydroxybenzoic acid) benefits from significant resonance stabilization. The electronic properties of the aromatic ring and the greater intrinsic stability of carboxyl groups relative to ethyl ester groups collectively drove this reaction toward a thermodynamically favorable direction [86]. These findings confirmed that N-DOM compounds had higher structural stabilities than MP-DOM compounds.

Fig. 9.

The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), electrostatic potential distribution, and possible reaction pathways of typical compounds in SY-DOM and CJ-DOM (a), TR-DOM (b), PVC-DOM (c), as well as PP-DOM and PE-DOM (d) during the reaction with heavy metals.

According to the electrostatic potential distribution within these compounds, the C–O and C=O functional groups, along with regions near the benzene ring, exhibited more pronounced negative values (Fig. 9). These regions were characterized by higher “negative” electrostatic potentials and typical nucleophilic sites, making them more likely to bind with HMs [87]. Consequently, in DOM, the reaction sites for compounds interacting with HMs were predominantly localized to ether, phenolic hydroxyl, and carboxyl regions, consistent with the results of the 2D-FTIR-COS analysis. We observed that the nucleophilic sites within N-DOM compounds were not readily accessible, in stark contrast to those within MP-DOM compounds (Fig. 9a and b). In MP-DOM, almost all nucleophilic sites were surface-exposed, validating the high reactivity of these compounds (Fig. 9c and d). Regarding the transformation pathways, the interaction between HMs and these functional groups typically triggered “spontaneous” chemical bond disruption within the compounds. In particular, for N-DOM, representative compounds such as (E)-3-(4-acetyloxy-2,3-dihydroxy-2,5,5,8a-tetramethyl-3,4,4a, 6,7,8-hexahydro-1H-naphthalen-1-yl) prop-2-enoic acid and palmitic acid retained complex chemical structures even after reacting with HMs. Conversely, in MP-DOM, compounds such as ethyl 4-hydroxybenzoate and 4-hydroxydiphenylketone might have degraded into phenol and benzene following their reactions with HMs. Ethyl 4-hydroxybenzoate and 4-hydroxybenzophenone are generally considered MP-derived compounds with inherent biotoxicity, and their degradation byproducts (phenol and benzene) may, likewise, pose potential environmental hazards [59]. Importantly, the complexation of HMs with these smaller molecular entities enhanced their solubility in the aquatic column, thereby facilitating their environmental dispersion.

4. Conclusion

The escalating pace of urbanization and industrialization has exacerbated pollution from HMs and MPs within aquatic ecosystems. This issue is particularly pronounced in industrial wastewater and municipal sewage, where these contaminants frequently coexist, often at elevated concentrations. Against this backdrop, the present study explores the interactions of N-DOM and MP-DOM with various HMs, highlighting significant differences in their fluorescent properties and molecular reactions. N-DOM is rich in humic-like substances, lignin-like, and tannin-like compounds, characterized by a high degree of aromatization and humification. Functional groups (carboxyl, phenolic hydroxyl, and ether bonds) in N-DOM frequently form highly stable complexes with HMs. However, MP-DOM mainly comprises protein/phenolic-like substances and contains a higher number of condensed aromatic and protein/aliphatic-like compounds, which exhibit high reactivity toward HMs. MP-DOM readily forms unstable complexes with HMs, and its compounds are susceptible to oxidation by Cr. In addition, the binding specificities of HMs with DOM are markedly pronounced. Cr preferentially induces changes in the phenolic hydroxyl group in MP-DOM, while Cu, Cd, and Pb exhibit affinities for the ether and carboxyl groups in N-DOM. Despite undergoing decarboxylation and dealkylation reactions upon exposure to HMs, N-DOM compounds can maintain their complex spatial structures, yielding natural products such as 4-ethyl-3,4a, 8,8-tetramethyl-decanaphthane-1,2,3-triol. However, compounds in MP-DOM may degrade into small, hazardous molecules (e.g., phenol, benzene) after interacting with HMs, thereby increasing the risk of environmental pollution. This study provides vital insights into the divergent roles that N-DOM and MP-DOM play in the complexation and transformation processes involving HMs, offering a molecular-level foundation for elucidating their environmental impacts and informing pollution-mitigation strategies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xianbao Zhong: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kaiying Zhao: Validation, Software. Mengyuan Wu: Visualization, Methodology. Yaohui Zhang: Methodology, Formal analysis. Chiyue Ma: Validation, Software. Hexiang Liu: Visualization, Methodology. Bokun Chang: Validation, Software. Xiaohui Lian: Data curation. Yujing Li: Methodology. Zixuan Huang: Validation. Lang Zhu: Writing – review & editing. Ming Zhang: Data curation. Chi Zhang: Writing – review & editing. Yajun Yang: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jialong Lv: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National natural science foundation of China (Project No. 42407037), the Shaanxi Province Postdoctoral Research Project (Project No. 2023BSHYDZZ62), the General project of Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program (Project No. 2024JC-YBQN-0264), Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Project No. 2024NC-ZDCYL-02-14) and Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Project No. 2024NYGG011).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2025.100610.

Contributor Information

Yajun Yang, Email: yajuny@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Jialong Lv, Email: ljlll@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Fang S., Fang Z., Hua C., Zhu M., Tian Y., Yong X., Yang J., Ren L. Distribution, sources, and risk analysis of heavy metals in sediments of xiaoqing river basin, Shandong Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023;30(52):112445–112461. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-30239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaaban M., Nunez-Delgado A. Soil adsorption potential: harnessing earth's living skin for mitigating climate change and greenhouse gas dynamics. Environ. Res. 2024;251 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.118738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olatunji O.S., Osibanjo O. North Central Nigeria; 2013. Eco-Partitioning and Indices of Heavey Metal Accumulation in Sediment and Tilapia zillii Fish in Water Catchment of River Niger at Ajaokuta. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemachandra S.C.S.M., Sewwandi B.G.N. Application of water pollution and heavy metal pollution indices to evaluate the water quality in st. Sebastian canal, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023;20 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weihua T., Lei W., Jianling G., Shuting W., Yu Z. Heavy metal pollution and source analysis of weihe river in Shaanxi Province. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2017;7(6):684–690. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu D., Wang J., Yu H., Gao H., Xu W. Evaluating ecological risks and tracking potential factors influencing heavy metals in sediments in an urban river. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021;33(1):42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y., Song S., Wang R., Liu Z., Meng J., Sweetman A.J., Jenkins A., Ferrier R.C., Li H., Luo W., Wang T. Impacts of soil and water pollution on food safety and health risks in China. Environ. Int. 2015;77:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L., Wu Y., Li J., Ni Z., Ren Y., Lin J., Huang X. Hydrodynamics and dissolved organic matter components shaped the fate of dissolved heavy metals in an intensely anthropogenically disturbed Estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;934 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu D., Du Y., Yu S., Luo J., Duan H. Human activities determine quantity and composition of dissolved organic matter in Lakes along the yangtze river. Water Res. 2020;168 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tazisong I.A., Senwo Z.N., He Z. Elemental composition and functional groups in soil labile organic matter fractions. Labile Organic Matter—Chemical Compositions, Function, and Significance in Soil and the Environment. 2015:137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu B., Wang P., Wang C., Qian J., Bao T., Shi Y. Investigating spectroscopic and copper-binding characteristics of organic matter derived from sediments and suspended particles using EEM-PARAFAC combined with two-dimensional fluorescence/FTIR correlation analyses. Chemosphere. 2019;219:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan T., Yao X., Ren H., Liu L., Deng H., Shao K. Regional-scale investigation of the molecular weight distribution and metal-binding behavior of dissolved organic matter from a shallow macrophytic Lake using multispectral techniques. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;439 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marschner B., Kalbitz K. Controls of bioavailability and biodegradability of dissolved organic matter in soils. Geoderma. 2003;113(3–4):211–235. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adusei-Gyamfi J., Ouddane B., Rietveld L., Cornard J.-P., Criquet J. Natural organic matter-cations complexation and its impact on water treatment: a critical review. Water Res. 2019;160:130–147. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michael-Kordatou I., Michael C., Duan X., He X., Dionysiou D., Mills M., Fatta-Kassinos D. Dissolved effluent organic matter: characteristics and potential implications in wastewater treatment and reuse applications. Water Res. 2015;77:213–248. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hur J., Lee D.-H., Shin H.-S. Comparison of the structural, spectroscopic and phenanthrene binding characteristics of humic acids from soils and Lake sediments. Org. Geochem. 2009;40(10):1091–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu J., Zhang H., He P.-J., Shao L.-M. Insight into the heavy metal binding potential of dissolved organic matter in MSW leachate using EEM quenching combined with PARAFAC analysis. Water Res. 2011;45(4):1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geyer R., Jambeck J.R., Law K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017;3(7) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W.C., Tse H.F., Fok L. Plastic waste in the marine environment: a review of sources, occurrence and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;566–567:333–349. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Z., Cao X., Wang K., Guan Y., Ma Y., Li Z., Guan J. The environmental effects of microplastics and microplastic derived dissolved organic matter in aquatic environments: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeley M., Song B., Passie R., Hale R. Microplastics affect sedimentary microbial communities and nitrogen cycling. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Y., Zhang Y., Lang M., Guo X., Xia T., Wang T., Jia H., Zhu L. Identification of sources, characteristics and photochemical transformations of dissolved organic matter with EEM-PARAFAC in the wei river of China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021;15:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang B., Yang T., Fan S., Zhen L., Zhong X., Yang F., Liu Y., Shao C., Hu F., Xu C., Yang Y., Dai Y., Lv J., Du W. Molecular-level insights of microplastic-derived soluble organic matter and heavy metal interactions in different environmental occurrences through EEM-PARAFAC and FT-ICR MS. J. Hazard Mater. 2025;487 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.137050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y.K., Hong S., Hur J. Copper-binding properties of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy and two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Water Res. 2021;190 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q., Gu W., Chen H., Wang S., Hao Z. Molecular properties of dissolved organic matter leached from microplastics during photoaging process. J. Hazard Mater. 2024;480 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X., Fang L., Gardea-Torresdey J.L., Zhou X., Yan B. Microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter: generation, characterization, and environmental behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;948 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi N.E., Lee Y.K., Oh H., Hur J. Photo-induced leaching behaviors and biodegradability of dissolved organic matter from microplastics and terrestrial-sourced particles. Chemosphere. 2024;355 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M., Xu J., Tang R., Yuan S., Min Y., Xu Q., Shi P. Roles of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter on the photodegradation of organic micropollutants. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;440 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu S., Qiu Y., He Z., Shi C., Xing B., Wu F. Microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter and its biogeochemical behaviors in aquatic environments: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024;54(11):865–882. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hahladakis J.N., Velis C.A., Weber R., Iacovidou E., Purnell P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard Mater. 2018;344:179–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee Y.K., Yoo H.-Y., Ko K.-S., He W., Karanfil T., Hur J. Tracing microplastic (MP)-Derived dissolved organic matter in the infiltration of MP-contaminated sand system and its disinfection byproducts formation. Water Res. 2022;221 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang M., Li Z., Huang B., Luo N., Zhang Q., Zhai X., Zeng G. Investigating binding characteristics of cadmium and copper to DOM derived from compost and rice straw using EEM-PARAFAC combined with two-dimensional FTIR correlation analyses. J. Hazard Mater. 2018;344:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M., He Z. Characteristics of dissolved organic carbon revealed by ultraviolet-visible absorbance and fluorescence spectroscopy: the current status and future exploration. Labile Organic Matter—Chemical Compositions, Function, and Significance in Soil and the Environment. 2015:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W., Habibul N., Liu X.-Y., Sheng G.-P., Yu H.-Q. FTIR and synchronous fluorescence heterospectral two-dimensional correlation analyses on the binding characteristics of copper onto dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49(4):2052–2058. doi: 10.1021/es5049495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosario-Ortiz F.L., Korak J.A. ACS Publications; 2017. Oversimplification of Dissolved Organic Matter Fluorescence Analysis: Potential Pitfalls of Current Methods. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y., Jin Y., Liu X., Miao T., Guan Q., Yang R., Qu J. Insight into interactions of heavy metals with livestock manure compost-derived dissolved organic matter using EEM-PARAFAC and 2D-FTIR-COS analyses. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;420 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He Z. Agricultural and environmental significance of soil organic matter and plant biomass: insight from ultrahigh-resolution fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Pedosphere. 2025;35(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo L., Chen Z., Lv J., Cheng Y., Wu T., Huang R. Molecular understanding of dissolved Black carbon sorption in soil-water environment. Water Res. 2019;154:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S., Qiu Y., He Z., Shi C., Xing B., Wu F. Microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter and its biogeochemical behaviors in aquatic environments: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024;54:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song F., Li T., Shi Q., Guo F., Bai Y., Wu F., Xing B. Novel insights into the molecular-level mechanism linking the chemical diversity and copper binding heterogeneity of biochar-derived dissolved black carbon and dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55(17):11624–11636. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan Z., He C., Shi Q., Xu C., Li Z., Wang C., Zhao H., Ni J. Molecular insights into the transformation of dissolved organic matter in landfill leachate concentrate during biodegradation and coagulation processes using ESI FT-ICR MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(14):8110–8118. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu P., Li H., Wu J., Wu X., Shi Y., Yang Z., Huang K., Guo X., Gao S. Polystyrene microplastics accelerated photodegradation of co-existed polypropylene via photosensitization of polymer itself and released organic compounds. Water Res. 2022;214 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu D., Gao H., Yu H., Song Y. Applying EEM-PARAFAC combined with moving-window 2DCOS and structural equation modeling to characterize binding properties of Cu (II) with DOM from different sources in an urbanized river. Water Res. 2022;227 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W., Zhang F., Ye Q., Wu D., Wang L., Yu Y., Deng B., Du J. Composition and copper binding properties of aquatic fulvic acids in eutrophic taihu Lake, China. Chemosphere. 2017;172:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Concas A., Ardau C., Cristini A., Zuddas P., Cao G. Mobility of heavy metals from tailings to stream waters in a mining activity contaminated site. Chemosphere. 2006;63(2):244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivasa Gowd S., Govil P.K. Distribution of heavy metals in surface water of ranipet industrial area in Tamil Nadu, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008;136(1):197–207. doi: 10.1007/s10661-007-9675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alimi O.S., Farner Budarz J., Hernandez L.M., Tufenkji N. Microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments: aggregation, deposition, and enhanced contaminant transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52(4):1704–1724. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chae Y., An Y.-J. Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2018;240:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berkovic A.M., García Einschlag F.S., Gonzalez M.C., Pis Diez R., Mártire D.O. Evaluation of the Hg2+ binding potential of fulvic acids from fluorescence Excitation—Emission matrices. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013;12(2):384–392. doi: 10.1039/c2pp25280e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stedmon C.A., Bro R. Characterizing dissolved organic matter fluorescence with parallel factor analysis: a tutorial. Limnol Oceanogr. Methods. 2008;6(11) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan T., Yao X., Sun Z., Sang D., Liu L., Deng H., Zhang Y. Properties and metal binding behaviors of sediment dissolved organic matter (SDOM) in Lakes with different trophic states along the yangtze river basin: a comparison and summary. Water Res. 2023;231 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.119605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hays M.D., Ryan D.K., Pennell S. A modified multisite stern− volmer equation for the determination of conditional stability constants and ligand concentrations of soil fulvic acid with metal ions. Anal. Chem. 2004;76(3):848–854. doi: 10.1021/ac0344135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.da Silva J.C.E., Machado A.A., Oliveira C.J., Pinto M.S. Fluorescence quenching of anthropogenic fulvic acids by Cu (II), Fe (III) and UO22+ Talanta. 1998;45(6):1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(97)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noda I., Ozaki Y. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy: Applications in Vibrational and Optical Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grimme S., Ehrlich S., Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32(7):1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marenich A.V., Cramer C.J., Truhlar D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113(18):6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024;161(8) doi: 10.1063/5.0216272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu T., Chen Q. Shermo: a general code for calculating molecular thermochemistry properties. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 2021;1200 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo H., Xiang Y., He D., Li Y., Zhao Y., Wang S., Pan X. Leaching behavior of fluorescent additives from microplastics and the toxicity of leachate to Chlorella vulgaris. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;678:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee Y.K., Hong S., Hur J. A fluorescence indicator for source discrimination between microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter and aquatic natural organic matter. Water Res. 2021;207 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu Z., Cao X., Wang K., Guan Y., Ma Y., Li Z., Guan J. The environmental effects of microplastics and microplastic derived dissolved organic matter in aquatic environments: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;933 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie J., Xia H., Guan M., Huang K., Chen J. Accelerating the humification mechanism of dissolved organic matter using biochar during vermicomposting of dewatered sludge. Waste Manag. 2023;159:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2023.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwarz F.P., Wasik S.P. Fluorescence measurements of benzene, naphthalene, anthracene, pyrene, fluoranthene, and benzo [e] pyrene in water. Anal. Chem. 1976;48(3):524–528. doi: 10.1021/ac60367a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carstea E.M., Bridgeman J., Baker A., Reynolds D.M. Fluorescence spectroscopy for wastewater monitoring: a review. Water Res. 2016;95:205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spagnuolo M.L., Marini F., Sarabia L.A., Ortiz M.C. Migration test of bisphenol A from polycarbonate cups using excitation-emission fluorescence data with parallel factor analysis. Talanta. 2017;167:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee Y.K., Murphy K.R., Hur J. Fluorescence signatures of dissolved organic matter leached from microplastics: polymers and additives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(19):11905–11914. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dittmar T., Koch B., Hertkorn N., Kattner G. A simple and efficient method for the solid-phase extraction of dissolved organic matter (SPE-DOM) from seawater. Limnol Oceanogr. Methods. 2008;6(6):230–235. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carstensen L., Beil S., Börnick H., Stolte S. Structure-related endocrine-disrupting potential of environmental transformation products of benzophenone-type UV filters: a review. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;430 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen H., Hu X., Yin D. Benzotriazole ultraviolet stabilizers in the environment: a review of occurrence, partitioning and transformation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;954 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang J., Hou X., Zhang K., Xiao Q., Gardea-Torresdey J.L., Zhou X., Yan B. Photochemistry of microplastics-derived dissolved organic matter: reactive species generation and organic pollutant degradation. Water Res. 2025;269 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.122802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu K., Jia H., Sun Y., Dai Y., Zhang C., Guo X., Wang T., Zhu L. Long-term phototransformation of microplastics under simulated sunlight irradiation in aquatic environments: roles of reactive oxygen species. Water Res. 2020;173 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gu X., Zhang C., Mo S., Korshin G.V., Yan M. Insights into molecules of natural organic matter binding with a Copper(II) cation: interpretation based on FT-ICR-MS and differential UV–Vis absorbance spectra. ACS ES&T Water. 2023;3(10):3315–3322. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryan D.K., Weber J.H. Fluorescence quenching titration for determination of complexing capacities and stability constants of fulvic acid. Anal. Chem. 1982;54(6):986–990. [Google Scholar]