Abstract

Background

Community pharmacists have expanded their roles beyond traditional medication dispensing to include various clinical services. They play a critical role in reducing medication-related errors and enhancing patient safety. However, their effectiveness is significantly influenced by their work environment and associated challenges.

Objectives

This cross-sectional study evaluates the stress levels of community pharmacists in Florida, USA, and examines how stress impacts patient care.

Methods

A survey was developed and emailed to 23,016 licensed pharmacists in Florida. Responses were collected from March 9 to April 15, 2022. The primary outcomes measured were workplace stressor frequency in community pharmacies and the relationship between work environment factors and patient care quality. Secondary outcomes assessed differences in average Perceived Stress Scores (PSS) between chain and independent pharmacists and between those in managerial versus non-managerial roles.

Results

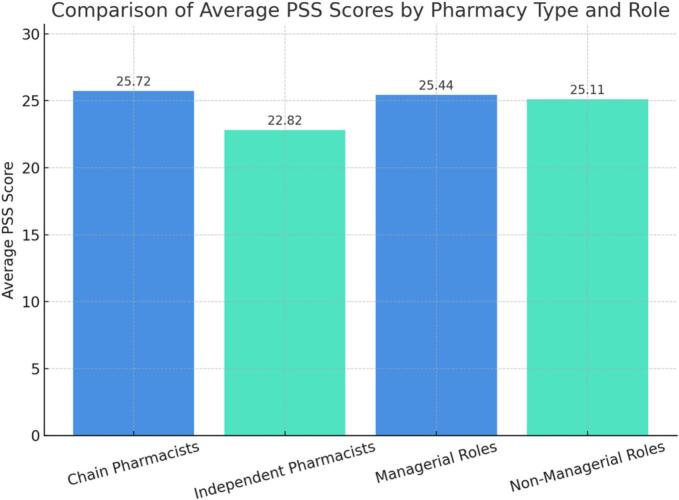

Of 361 responses, 257 pharmacists completed the survey. Most (84.8 %) were chain pharmacists, 15.2 % independent. The primary stressor was staffing issues (57.98 %). Additionally, 71.9 % deemed working conditions unsafe, and 78.4 % struggled to provide quality care due to work stress. Chain pharmacists had significantly different PSS scores (22.72) versus independent pharmacists (22.82, p = 0.0034). No difference existed between managerial (25.44) and non-managerial pharmacists (25.11, p = 0.5962). Spearman correlations showed significant negative associations between PSS scores and difficulty providing quality care (ρ = −0.47, p < 0.0001) and unsafe conditions perceptions (ρ = −0.51, p < 0.0001). Patient care measures correlated positively (ρ = 0.71, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Stress significantly impacts community pharmacists' ability to provide quality care.

Keywords: Community pharmacy, Pharmacist stress, Patient care impact, Working conditions

Highlights

-

•

Pharmacists report that workplace stress compromises their ability to provide safe care.

-

•

Inadequate staffing and strict performance metrics are major stressors in community pharmacies.

-

•

High pharmacist stress may increase the risk of medication errors and impact patient safety.

-

•

Addressing staffing shortages and workload expectations can help reduce pharmacist

-

•

Policy changes are needed to align pharmacy metrics with patient-centered care outcomes.

1. Background

In recent decades, the tasks of community pharmacists have expanded considerably beyond traditional medication dispensing to encompass various clinical services, including medication therapy management, immunizations, an enhanced role in mental health support, chronic disease management such as lipid disorders, diabetes, and hypertension, hence improving public health outcomes.1 According to the 2022 National Pharmacist Workforce Study, pharmacists now spend significant time on administering vaccines, with 86.5 % of chain pharmacists reporting increased vaccination activities since March 2020, as well as providing medication synchronization services, point-of-care testing, and patient medication assistance programs.2 The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this role expansion, with pharmacists taking on critical responsibilities in public health emergency response, vaccine administration, and telehealth services.3,4 Community pharmacists, as essential healthcare professionals, reduce medication-related errors and enhance patient safety in their communities.5 However, the effectiveness of their contributions is considerably influenced by their work environment and the many challenges they encounter,5 with the 2022 NPWS revealing that nearly 40 % of chain pharmacists believe their workplace activities significantly reduce patient medication safety.2

A recent study has shown concerning trends about pharmacists' job satisfaction and workload demands. According to the 2019 National Pharmacist Workforce Study (NPWS), 71 % of pharmacists reported having “high” or “excessively high” workload levels. This issue was more noticeable in community chain settings, where 91 % of pharmacists expressed similar worries.6 In contrast to those in independent and small chain settings, responding pharmacists employed in large chain, mass merchandiser, and supermarket pharmacies reported the lowest levels of job control and job satisfaction in the 2022 NPWS, further demonstrating that these difficulties have remained after COVID.2 Notably, compared to independent pharmacists, 62.9 % of chain pharmacists agreed that their job activities go beyond what they were initially hired to do, and only 26.2 % of chain pharmacists believed that there was enough staffing to meet patient care needs, compared to 75.9 % of independent pharmacists.2 As a result, pharmacists who have difficulty providing patients with the necessary care are also more likely to believe that their employment is hazardous.

Tsao et al. (2016) highlighted those significant issues such as insufficient breaks or lunches, limited time to fulfill work responsibilities, and understaffing can lead to low job satisfaction rate among chain store pharmacists compared to those in independent pharmacies due to negative workplace environment.5 Moreover, Clabaugh et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey to evaluate community pharmacists' perceptions of issues within their work environment including company climate, workflow issues, and career satisfaction.7 The results of the survey found that pharmacists working in community settings, especially in a chain pharmacy, had fears of being disciplined for addressing patient safety issues with management.7 For instance, a large proportion of respondents reported apprehension about being reprimanded for actions intended to maintain a safe work environment, such as taking mandatory rest breaks or voicing staffing inadequacies. One pharmacist described being scolded by management for staying late to prevent a serious pediatric dosing error involving insulin, highlighting how safety-driven decisions were sometimes met with punitive responses rather than support. These accounts reflect a broader culture in which pharmacists feel pressure to prioritize performance metrics over patient safety, contributing to a climate of fear and moral distress.7

A recent study has demonstrated the impact of work-related stress on pharmacist's performance and patient safety. Studies by Peterson et al. and Hassell et al. have shown a significant correlation between increased workload and the frequency of dispensing errors, with mistakes rising in direct proportion to prescription volume.8,9 Patel et al. reported that 68.9 % of community pharmacists displayed symptoms of burnout that can negatively affect the patients, while Wash et al., in their narrative review, found that U.S. community pharmacists experienced increased work-related stress and burnout, significantly correlating with a higher risk of medication errors and reduced patient safety.10,11

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated stress levels among healthcare workers, especially pharmacists, highlighting that occupational stress is a significant issue.9,12, 13, 14 A recent study by Tobia et al. (2023) examined stress levels among community pharmacists during COVID-19, revealing significant emotional exhaustion and increased risk perceptions among these healthcare workers. Their findings indicated a rise in perceived stress ratings from 15.5 to 18.2 (p = 0.0438), indicating moderate stress levels despite pharmacists reporting a strong understanding of COVID-19 prevention protocols such as hand hygiene, personal protective equipment usage, and social distancing guidelines.9 A 2021 research including 484 health-system pharmacists during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that 47 % reported experiencing burnout, while 65.3 % exhibited a moderate to high probability of burnout according to standardized assessments.12 Over 50 % experienced secondary traumatic stress; nonetheless, most maintained high levels of compassion satisfaction despite these challenges. The researchers emphasized that burnout and secondary traumatic stress (STS) can lead to serious consequences,12 including an increased likelihood of medical errors, depression, and other workplace difficulties, thereby highlighting the necessity of addressing these issues in healthcare settings.

1.1. Objectives

This study will evaluate the stress levels of community pharmacists in the State of Florida, and how stress influences the care they provide to their patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This cross-sectional survey study was conducted to assess work-related stress among licensed pharmacists in Florida. The survey was developed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform and distributed via email.

2.2. Setting and participants

The study included 23,016 pharmacists licensed in the state of Florida. Email addresses were obtained from the Florida Board of Pharmacy in February 2022 and filtered to exclude individuals with inactive licenses or those practicing outside Florida. The first four questions established inclusion criteria to ensure a focused study population. The study included pharmacists who completed the entire survey and were actively practicing in community settings (independent or chain pharmacies) for 50 % or more of their work week. Eligible participants either held managerial titles (such as prescription department manager or assistant pharmacy manager) or worked as non-floating staff pharmacists with no manager title. Several groups were excluded from the study: pharmacists working in inpatient settings (hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, long-term care facilities), those employed in industry, individuals with roles such as district manager or regional pharmacy manager, and pharmacists working less than 50 % of their work week, retired pharmacists. Demographic, workplace environment, and compensation information was collected in addition to questions evaluating stress levels.

2.3. Survey instrument

The survey instrument was adapted from the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a validated measure of perceived stress, with modifications made to assess work-related stress among pharmacists. Higher PSS scores indicate greater perceived stress in the work environment. Although the PSS-10 does not have official clinical cutoffs, prior literature typically classifies scores as low (0−13), moderate (14–26), and high (27–40) stress.15 The final survey instrument included a 44 questions across six main sections: (1) practice characteristics (e.g., setting, position, shift length, prescription volume); (2) the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a validated measure assessing perceived stress over the past month (total score range: 0–40); (3) work environment indicators, including items related to staffing, rest breaks, distractions, and supervisory communication; (4) patient safety perceptions, including concerns about medication errors, quality-related events (QREs), and performance metrics; (5) quality of patient care, focusing on pharmacists' perceived ability to engage with and assist patients; and (6) demographic information (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, years in practice, hourly wage).

Construct validity was examined through inter-item correlation analysis, which showed moderate to strong relationships among items within each domain. Internal consistency was confirmed with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.74, indicating acceptable reliability. Item-deletion analysis showed that all items contributed meaningfully to the overall consistency. A formal pilot study was not conducted due to time/resource constraints.

2.4. Data collection

Data were collected using the REDCap platform, which also served to ensure data security and manage participant responses. The survey was distributed via email to eligible pharmacists beginning on March 9, 2022. To improve participation, up to 4 email reminders were sent during the initial data collection period, which lasted through April 6, 2022. REDCap's built-in response tracking system was utilized to automatically exclude individuals who had already completed the survey from receiving additional reminders and to restrict responses to one per email address.

Due to a low initial response rate, the data collection period was extended by an additional week. During this extension, more than 100 additional responses were obtained. In total, survey responses were collected between March 9 and April 15, 2022.

To ensure confidentiality, all responses were de-identified and assigned unique identifiers within REDCap. The system also restricted submissions to one response per email address to preserve data integrity.

2.5. Variables, measures

This study analyzed several key variables, including the total Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) score, pharmacy practice setting (chain vs. independent), managerial status, reported workplace stressors (e.g., lack of breaks, feeling rushed), patient safety concerns, and demographic characteristics. The primary outcomes focused on identifying the most frequently reported stressor in the community pharmacy setting and evaluating how the work environment impacts patient care. Secondary outcomes included comparisons of average PSS scores between pharmacists working in chain versus independent pharmacies and between those with and without managerial roles.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of survey respondents. For the primary outcomes, frequencies and percentages were calculated to identify the most frequently reported stressors and the proportion of pharmacists who indicated that their work environment affects patient care. To assess the relationship between perceived stress and pharmacists' ability to provide patient care, Spearman rank-order correlation analyses were conducted. Correlation coefficients (ρ) and corresponding p-values were reported, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

For the secondary outcomes, a Welch's ANOVA was conducted to compare average PSS scores between chain and independent pharmacists, and a one-way ANOVA was used to examine differences in PSS scores between pharmacists in managerial versus non-managerial roles. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software, with significance set at p < 0.05.

2.7. Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed and exempted by the Nova Southeastern University Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

This cross-sectional study was conducted over five weeks and yielded a total of 361 responses. Of these, 257 met the inclusion criteria and completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of approximately 1.1 % based on the 23,016 pharmacists contacted.

Table 1 provides the professional and demographic characteristics of the survey participants. Only 39 (15.2 %) of the respondents were employed by independent pharmacies, while the majority (218; 84.8 %) were employed by chain pharmacies. This distribution exhibits a significant imbalance in workplace representation due to disparities in accessibility, workload, or survey participation. The sample included a higher proportion of female pharmacists (57.6 %) than male pharmacists (38.9 %). The age distribution of the working-age cohorts was evenly distributed, with the largest group being those in the 30- to 39-year-old age range (25.3 %). The sample was mostly composed of white individuals (67.3 %), followed by Asian individuals (12.1 %) and Hispanic/Latino individuals (19.5 %). Professional roles were evenly divided between staff pharmacists with managerial titles (50.2 %) and those without (49.8 %). Experience levels varied widely, with 19.1 % having less than 5 years of experience as licensed pharmacists and 7.0 % with more than 40 years of experience. The majority of respondents (44.7 %) reported hourly pay between $56 and $65.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents (N = 257).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Practice Setting | ||

| Chain pharmacy | 218 | 84.8 |

| Independent pharmacy | 39 | 15.2 |

| Professional Role | ||

| Staff pharmacist with managerial title | 129 | 50.2 |

| Staff pharmacist without managerial title | 128 | 49.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 148 | 57.6 |

| Male | 100 | 38.9 |

| Prefer not to say | 9 | 3.5 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 28 | 10.9 |

| 30–39 | 65 | 25.3 |

| 40–49 | 58 | 22.6 |

| 50–59 | 57 | 22.2 |

| 60 or older | 39 | 15.2 |

| Prefer not to say | 10 | 3.9 |

| Race | ||

| White | 173 | 67.3 |

| Asian | 31 | 12.1 |

| Black or African American | 16 | 6.2 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 | 1.2 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.8 |

| Prefer not to say | 32 | 12.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 50 | 19.5 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 186 | 72.4 |

| Prefer not to say | 21 | 8.2 |

| Years as Licensed Pharmacist | ||

| Less than 5 | 49 | 19.1 |

| 5–9 | 43 | 16.7 |

| 10–14 | 31 | 12.1 |

| 15–19 | 26 | 10.1 |

| 20–24 | 29 | 11.3 |

| 25–29 | 28 | 10.9 |

| 30–34 | 20 | 7.8 |

| 35–39 | 13 | 5.1 |

| More than 40 | 18 | 7.0 |

| Years in Community Pharmacy | ||

| Less than 5 | 35 | 13.6 |

| 5–9 | 43 | 16.7 |

| 10–14 | 33 | 12.8 |

| 15–19 | 39 | 15.2 |

| 20–24 | 35 | 13.6 |

| 25–29 | 25 | 9.7 |

| 30–34 | 20 | 7.8 |

| 35–39 | 12 | 4.7 |

| More than 40 | 15 | 5.8 |

| Hourly Pay (USD) | ||

| $35 to $45 | 16 | 6.2 |

| $46 to $55 | 66 | 25.7 |

| $56 to $65 | 115 | 44.7 |

| $66+ | 60 | 23.3 |

Primary Outcomes:

Pharmacists more frequently reported staffing issues as the biggest stressor in their work environment at 57.98 %, followed by predetermined metrics at 31.91 % based on responses to the item asking about the biggest contributor to workplace stress (Table 2; Fig. 1). Staffing issues were defined by elimination of a second pharmacist and decreased allocated pharmacy technician/intern hours. Predetermined metrics include waiter time, prescription count per week, and number of vaccines administered per day. Hourly pay was least likely to be identified as the biggest stressor at 5.06 %.

Table 2.

Overall, what is the biggest contribution to your stress levels at work?

| Stressor | Number of Responses | Percentage of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Predetermined Metrics | 82 | 31.91 % |

| Staffing Issues | 149 | 57.98 % |

| Insurance Reimbursement | 13 | 5.06 % |

| Hourly Pay | 13 | 5.06 % |

Fig. 1.

Top stressors reported by pharmacists, with staffing issues and metrics cited most frequently.

To assess the impact of workplace stress on pharmacists and the patient care, two survey items were analyzed (Table 3). Among 257 respondents, 105 (41.0 %) strongly agreed and 79 (30.9 %) agreed with the statement, “Conditions at work are unpleasant and sometimes unsafe for myself and the patients.” Similarly, 133 respondents (52.1 %) strongly agreed and 67 (26.3 %) agreed with the statement, “I find it difficult to provide quality care to patients due to the work environment.” These findings suggest that many pharmacists perceive their work environment as a barrier to delivering safe and effective care (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

The percentage of pharmacists who reported that their work environment affects patient care.

| Question | Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly Disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions at work are unpleasant and sometimes unsafe for myself and the patients. | 105 (41.0 %) | 79 (30.9 %) | 52 (20.3 %) | 20 (7.8 %) |

| I find it difficult to provide quality care to patients due to the work environment. | 133 (52.1 %) | 67 (26.3 %) | 45 (17.6 %) | 10 (3.9 %) |

Secondary Outcomes

Fig. 2.

Perceptions of unsafe work conditions and care difficulty, showing high agreement with both concerns.

Spearman rank-order correlation analyses were conducted to assess the impact of stress at work on pharmacists and the kind of the care they provide. The results demonstrated significant negative correlations between scores and both items: difficulty in providing quality care (ρ = −0.47, p < 0.0001) and perceptions of unsafe conditions (ρ = −0.51, p < 0.0001). The findings indicate that individuals who are experiencing elevated levels of stress are more concerned about their safety in the workplace and believe that the quality of care they give is poor. There was a robust positive correlation between the two patient care measures (ρ = 0.71, p < 0.0001). Due to this, pharmacists who express difficulty in providing adequate care to patients are also more inclined to perceive their job as hazardous (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Spearman correlations showing higher stress is linked to greater care difficulty and patient redirection.

Welch's ANOVA was used to compare the average PSS scores of chain pharmacists (25.72) and independent pharmacists (22.82) for the secondary outcomes. The results indicated a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0034, 95 % CI), with chain pharmacists reporting higher stress levels. However, the mean PSS scores of pharmacists in managerial positions (25.44) and those in non-managerial roles (25.11) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and showed no significant difference (p = 0.5962, 95 % CI) (Table 4; Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Average PSS.

| Type of Pharmacist | Average PSS Score | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Pharmacists (N = 218,) 84.8 % | 25.72 | 0.0034 |

| Independent Pharmacists (N = 39) 15.2 % | 22.82 | |

| Managerial Roles (N = 129) 50.2 % |

25.44 | 0.5962 |

| Non-Managerial Roles (N = 128) 49.8 % | 25.11 |

PSS: Perceived Stress Score.

Fig. 4.

Average PSS scores by pharmacist type and role.

4. Discussion

To the knowledge of the researchers, this is the first large-scale survey that was sent to Florida community pharmacists to assess stress levels within their work environment. The confidentiality of this survey provides a safe place for pharmacists to voice their concerns regarding their work environment without fear of retaliation from employers. The survey was designed to exclude individuals who do not practice in the environments that they set rules and create workflow/metrics for, such as district managers or regional managers. The results of this study can provide proof to state organizations and legislators that patient care is affected by the amount of stress that community pharmacists are under and hopefully promote change.

It is concerning that 71 % of pharmacists find their jobs unpleasant, and 78 % report difficulty providing quality patient care. This poses a major threat to drug safety and healthcare quality. These findings align with previous research on healthcare worker stress. The findings align with those of Shanafelt et al. (2019), which indicated a 43.9 % burnout rate among physicians and significantly worse work-life balance compared to the public. This indicates a systematic issue that might affect patient safety and the quality of care.16

While the results showed significant differences in PSS scores between chain and independent pharmacists (25.72 vs 22.82) as expected, it is important to note that most respondents worked in chain pharmacy settings, as it may limit the generalizability of stress-related outcomes to those practicing in independent settings. This outcome aligns with prior research indicating a higher prevalence of negative work attitudes in chain pharmacies vs to independent pharmacies.7

The analysis revealed no significant PSS differences between managerial and non-managerial roles, challenging conventional assumptions about hierarchical stress patterns.17 Organizations may need to reconsider their tiered approach to stress interventions. Rather than assuming managers require more intensive support, these findings suggest that comprehensive stress management programs should be equally accessible across all organizational levels. Future studies should examine whether specific stressor types (interpersonal vs. task-related) vary by role level, even when overall stress levels remain equivalent. Although there were more questions in the survey than analyzed, the questions chosen for analysis were pertinent to the objectives set forth by the researchers.

The significant negative correlations between stress levels and patient perceptions of their treatment (ρ = −0.47 to −0.51) indicate a relationship that has been considered but not quantitatively shown in community pharmacies.

4.1. Limitations

The study's sample size was modest (361 replies, 257 completions) relative to Florida's licensed pharmacist population (23,016 contacted), presumably attributable to communication challenges and the survey's extensive length (44 multi-part questions). A free-response section may uncover workplace problems. The inadequate response rate resulted from restricted promotional initiatives, namely REDCap emails. Future studies could be enhanced by extending response durations and state-specific advertising to augment participation and data integrity.

The PSS-10 is a validated instrument designed to measure how individuals perceive stress in their daily lives. However, in this study, the questions were slightly modified to focus specifically on respondents' work-related stress. As a result, the tools' original psychometric properties –particularly its construct validity– may not be directly comparable to those from studies using the original, unmodified PSS. In addition, due to time constraints, no formal pilot study was conducted. Despite this limitation, the adapted instrument provides important contextual insights into the stressors pharmacists encounter in their work environments. With data collected from this survey, future studies can aim to further evaluate the impact of a pharmacist's work environment on the care they deliver to their patients.

The disproportionate representation of practice settings in this study was a significant limitation; chain pharmacists constituted 84.8 % (n = 218) of the respondents, whereas independent pharmacists accounted for just 15.2 % (n = 39). The notable differences in workflow, management structure, and daily challenges between chain and independent pharmacy environments may have influenced our findings. Consequently, instead of representing the whole pharmacy profession, the results may more precisely reflect the experiences of chain pharmacists. To comprehensively represent the spectrum of pharmacist viewpoints, further study should aim for a more equitable sample across various practice environments.

5. Conclusion

Stress can impact community pharmacists' quality of work and therefore affect the quality of care they provide their patients. The findings of this research should encourage state governments to implement improvements so that pharmacists may operate in safer environments safeguarding patient welfare. Setting minimum staffing ratios based on prescription volume to avoid understaffing; making it a legal need for community pharmacies to do stress audits; coming up with ways for the state board of pharmacy to keep a closer look on workload metrics; and making sure that pharmacists have set hours to help patients and provide clinical services without interrupting their work. These concrete steps would address many of the stressors identified in this study and create more sustainable practice environments that protect both, pharmacists' wellbeing and patient safety.

Previous presentations of the work

Research in progress presented virtually at the 2021 Annual Midyear Meeting, and at the Florida Residency Conference in Tampa, FL on May 13th, 2022.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Goar Alvarez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Taylor Harris: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Erika Zwachte Fennick: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Leanne Lai: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Jesús Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Rawan Alkhamisi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

References

- 1.George P.P., Molina J.A., Cheah J., Chan S.C., Lim B.P. The evolving role of the community pharmacist in chronic disease management - a literature review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2010;39(11):861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mott D.A., Gaither C.A., Doucette W.R., et al. Pharmacy Workforce Center, Inc; 2022. National Pharmacist Workforce Study: Final Report. Accessed May 18, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isenor J.E., Cossette B., Murphy A.L., et al. Community pharmacists’ expanding roles in supporting patients before and during COVID-19: an exploratory qualitative study. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(1):21–29. doi: 10.1177/17151635211056197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pantasri T. Expanded roles of community pharmacists in COVID-19: a scoping literature review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62(5):1466–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2022.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsao N.W., Lynd L.D., Gastonguay L., Li K., Nakagawa B., Marra C.A. Factors associated with pharmacists’ perceptions of their working conditions and safety and effectiveness of patient care. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2016;149(1):18–27. doi: 10.1177/1715163515617777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaither C.A., Schommer J.C., Doucette W.R., Kreling D.H., Mott D.A. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; Arlington, VA: 2020. 2019 National Pharmacist Workforce Study. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clabaugh M, Newlon JL, Illingworth Plake KS. Perceptions of working conditions and safety concerns in community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(6):761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hassell K., Seston E.M., Schafheutle E.I., Wagner A., Eden M. Workload in community pharmacies in the UK and its impact on patient safety and pharmacists’ well-being: a review of the evidence. Health Soc Care Commun. 2011;19(6):561–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston K., O’Reilly C.L., Scholz B., Georgousopoulou E.N., Mitchell I. Burnout and the challenges facing pharmacists during COVID-19: results of a national survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):716–725. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01268-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SK, Kelm MJ, Bush PW, Lee HJ, Ball AM. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout in community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(2):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wash A, Moczygemba LR, Brown CM, Crismon ML, Whittaker TA. A narrative review of the well-being and burnout of U.S. community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2024;64(2):337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2023.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Tobia L., Muselli M., De Luca F., et al. Community pharmacists’ perceptions and experiences of stress during COVID-19. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2023;16(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s40545-023-00523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones A.M., Clark J.S., Mohammad R.A. Burnout and secondary traumatic stress in health-system pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(9):818–824. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxab051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedima E.W., Okoro R.N., Yelmis G.A., Adam H. Assessment of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of pharmacists: a nationwide survey. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2022;5 doi: 10.1016/j.rcsop.2022.100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt T.D., West C.P., Sinsky C., et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peter K.A., Schols J.M.G.A., Halfens R.J.G., Hahn S. Investigating work-related stress among health professionals at different hierarchical levels: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2020;7(4):969–979. doi: 10.1002/nop2.469. Published 2020 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]