Abstract

Aberrant activation of fibroblasts is a pivotal component of cardiac fibrosis predisposing to heart failure. However, the molecular regulation of the functional state of cardiac fibroblasts in fibrosis resolution remains largely unexplored, and therefore, effective antifibrosis therapies are still lacking. By translating mouse transcriptomics to humans, we unlocked common molecular denominators connecting the fibroblast phenotypic state and fibrogenic signaling pathways in cardiac fibrosis. Through the construction of a fibroblast-specific transcriptional gene regulatory network, we found ITGAL and DUSP9 as key druggable targets for human myocardial fibrosis. A computational drug repurposing approach predicted 367 antifibrotic candidate compounds for heart disease. In primary cardiac fibroblasts derived from patients with heart failure, we provided experimental validation of the top 2–ranked repositioned drug candidates and their combination. These innovative approaches facilitate the identification of potential targets and drug candidates for cardiac fibrosis, providing actionable opportunities for clinical translation.

Fibroblast-specific regulatory network analysis unravels therapeutic breakthroughs in the fight against cardiac fibrosis.

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial fibrosis is a common feature in heart failure (HF)–related fatalities (1). Aberrant tissue fibrosis reflects the clinical phenotype of a severe form of heart disease and correlates with mortality and the incidence of serious cardiovascular manifestations in patients with HF (2–4). A major hallmark of myocardial fibrosis is the uncontrolled activation of fibroblasts secreting collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in response to tissue damage (5). In a pathological setting, abnormal deposition of ECM components disrupts tissue architecture and ultimately culminates in cardiac dysfunction and HF (6). Current therapeutic strategies that improve HF survival primarily target the pathogenic mechanisms that occur within cardiomyocytes. However, the molecular basis of aberrant fibroblast activation dictating fibrosis resolution remains obscure, and therefore, effective antifibrosis therapies are still lacking.

Fibrotic remodeling is a complex and coordinated machinery triggering a complex cascade of molecular responses that culminates in phenotypic reprogramming of the heart (3, 7). Uncontrolled fibroblast transition from the naive to activated state is a central element dictating the resolution of organ fibrosis characterized by the de novo assembly of alpha–smooth muscle actin (αSMA) stress fibers (8). The phenotypic conversion of naive fibroblasts to αSMA-expressing myofibroblasts shifts the balance in ECM turnover, promoting accumulation of fibrotic deposition through activation of the transforming growth factor–β (TGFβ) signaling pathway and dominant mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (8, 9). The TGFβ pathway occupies a central position in the signaling networks orchestrating fibroblast behaviors in cardiac fibrosis. TGFβ acts through the heteromeric complex of TGFβ type I receptor and TGFβ type II receptor to activate two key downstream mediators, Smad2 and Smad3, to exert its biological activities including cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, and ECM production in an autocrine/paracrine manner (10). In addition to the canonical SMAD pathway, TGFβ receptors can also activate noncanonical pathways, resulting in activation of the MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling (10). A critical step in the initiation of the noncanonical pathway is activation of TGFβ activated kinase-1 (TAK1, MAP3K7) by TRAF6-mediated polyubiquitination (11). A deeper insight into the posttranslational intricacies of TGFβ signaling offers avenues for innovative therapeutic interventions to mitigate fibrosis progression.

Highly complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of cardiac fibrosis poses several limitations for target identification approaches in drug discovery. Identifying fibroblast-to-myofibroblast molecular fingerprints and predicting the targetability of genes are critical steps in drug discovery to tackle abnormal fibrotic remodeling (12). A number of key fibrosis-associated genes have been unlocked through in vitro and in vivo models in recent years (13). However, most of the discovered fibrosis-coupled genes are not causative, and agents that target noncausative genes predispose to clinical inefficiency. Reconstructions of gene regulatory networks from large-scale expression data, which explicitly represent the causal relationships among the genes, are of utmost interest and remain a challenging computational obstacle for understanding the complex regulatory mechanisms in cellular systems.

Drug target discovery is a key component of drug development and essential for identifying new molecular entities that enter clinical trials (14). Traditional drug discovery for cardiac fibrosis is costly, time-consuming, and burdened by a very low success rate. An alternative strategy is drug repositioning, redirecting existing drugs to new therapeutic indications (15). The rationale for drug repositioning lies in the large reservoir of data surrounding approved drugs, including pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and adverse event profiles (16). Leveraging these attributes can accelerate the identification of new therapeutic targets and deciphering the mechanisms of action, making drug repositioning a promising strategy to address unmet medical needs effectively.

In this study, we unlocked the distinct architecture of the causal gene regulatory networks governing fibrosing phenotype in cardiac fibroblasts. By transposing mouse transcriptomics to humans, we constructed fibroblast-specific regulatory networks to predict targets and drug candidates that could counteract aberrant fibrotic reprogramming in the heart. A network-based analysis for drug-target interactions predicted the candidate compounds for antifibrosis in a prioritized manner. Last, we functionally evaluated the antifibrotic potential of the two top-ranking drug candidates on primary cardiac fibroblasts derived from patients with HF.

RESULTS

Phenotypic and transcriptomic signatures of aberrant cardiac fibroblast activation

To decode the transcriptomic fingerprint of naive and activated fibroblasts, we first generated a TGFβ-activated phenotype of cardiac fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 1 (A to C), aberrantly activated fibroblast phenotype displayed elevated collagen accumulation, αSMA overexpression, and excessive mitochondrial ROS formation. Analysis of the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)–based transcriptome from naive and activated mouse fibroblasts uncovered 6736 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) consisting of 3348 up-regulated and 3388 down-regulated genes. As shown in Fig. 1D, we next generated a heatmap to pinpoint the top 40 differentially enriched genes controlling aberrant fibroblast behaviors priming fibrosis. To test the reliability of the RNA-seq–generated results, we analyzed the top 10 ranking DEGs involved in cardiac fibroblast activation (Table 1) using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), which closely matched the RNA-seq data (Fig. 1, E to F). Moreover, we tested the extrapolated DEGs in a mouse model of transverse aortic constriction (TAC)–induced fibrosis and HF. As shown in Fig. 2 (A to C), quantitative assessment of myocardial fibrosis in TAC-challenged hearts revealed a marked increase in tissue collagen accumulation linked to elevated mRNA expression of type I collagen compared to control sham mice. Notably, abnormal cardiac fibrosis was associated with decline in cardiac function as evidenced by a reduction in ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) in TAC mice compared to the control group (Fig. 2, D to F). The following top DEGs were identified in RNA-seq data and validated by qRT-PCR in the fibrosis-remodeled heart, up-regulated: Fgf21, Tnfsf18, Acan, Rph3A, Adamts8, and Sv2b; and down-regulated: Selenbp1, Ifitm1, and Myoc (Fig. 2, G and H).

Fig. 1. Phenotypic and transcriptome switching of activated mouse cardiac fibroblasts priming cardiac fibrosis.

Cells were starved for 2 hours in 2% serum-containing medium and then treated with TGFβ (10 ng/ml) at the indicated times. (A to C) Analysis of the TGFβ-activated fibrogenic phenotype in mouse cardiac fibroblasts (n = 3 to 10[Vehicle], 4 to 11[TGFβ]). (A) Abnormal collagen production after 72 hours of TGFβ. Left: Representative images of Picrosirius red staining and immunofluorescence staining of Collagen 1A1 (Col1A1) in red. Right: Quantifications of Collagen level by measuring the 570-nm absorbance after eluting the Sirius Red deposit and measurement of Col1A1 fluorescence intensity. (B) Fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition after 24 hours of TGFβ. Left: Representative images of the immunofluorescence staining of αSMA in green. Right: Quantifications of αSMA expression. (C) MitoSOX-detected mitochondrial ROS release after 1 hour of TGFβ. Left: Representative images for the MitoSOX signal in red. Right: Quantifications of mitochondrial ROS production. Nuclei are stained in blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (D) Heatmap of the top 40 genes enriched in TRANSPATH categories. The colored bar at the top indicates sample types. (E and F) Validation of RNA-seq results using qRT-PCR: (E) up-regulated and (F) down-regulated genes in naive and 24 hours of TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts (nmice = 4 from independent isolations). Values are presented as means ± SEM. P values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Table 1. Top 10 ranking up-regulated and down-regulated genes in TGFβ-challenged cardiac fibroblasts versus naive cells.

Log2FC, the logarithm to the base 2 of the fold change; logCPM, logarithm of counts per million reads; FDR, false discovery rate.

| Ensembl ID | Gene description | Gene symbol | Log2FC | LogCPM | P value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | ||||||

| ENSG00000145536 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 16 | ADAMTS16 | 4.013 | −0.480 | 2.2 × 10−33 | 2.1 × 10−31 |

| ENSG00000105550 | Fibroblast growth factor 21 | FGF21 | 3.482 | 3.156 | 9.2 × 10−35 | 1.0 × 10−32 |

| ENSG00000120337 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 18 | TNFSF18 | 3.445 | 5.122 | 6.9 × 10−48 | 1.6 × 10−45 |

| ENSG00000157766 | Aggrecan | ACAN | 3.110 | 4.693 | 2.7 × 10−69 | 1.2 × 10−66 |

| ENSG00000089169 | Rabphilin 3A | RPH3A | 3.008 | 1.380 | 5.5 × 10−9 | 5.7 × 10−8 |

| ENSG00000134917 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 8 | ADAMTS8 | 2.957 | 2.127 | 2.0 × 10−21 | 8.4 × 10−20 |

| ENSG00000162591 | Multiple EGF like domains 6 | MEGF6 | 2.753 | 3.264 | 7.3 × 10−11 | 1.0 × 10−9 |

| ENSG00000185518 | Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2B | SV2B | 2.749 | −0.822 | 4.6 × 10−10 | 5.7 × 10−9 |

| ENSG00000082196 | C1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein 3 | C1QTNF3 | 2.725 | 3.844 | 1.4 × 10−17 | 4.2 × 10−16 |

| ENSG00000151572 | Anoctamin 4 | ANO4 | 2.723 | 0.159 | 3.4 × 10−21 | 1.4 × 10−19 |

| Down-regulated genes | ||||||

| ENSG00000010932 | Flavin containing monooxygenase 1 | FMO1 | −2.872 | 2.375 | 2.8 × 10−23 | 1.5 × 10−21 |

| ENSG00000143416 | Selenium binding protein 1 | SELENBP1 | −2.943 | 4.920 | 7.0 × 10−115 | 2.0 × 10−110 |

| ENSG00000144649 | Family with sequence similarity 198 member A | FAM198A | −2.984 | 1.003 | 1.4 × 10−14 | 3.1 × 10−13 |

| ENSG00000167772 | Angiopoietinlike 4 | ANGPTL4 | −2.986 | 5.805 | 0.004 | 0.010 |

| ENSG00000185885 | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 | IFITM1 | −3.049 | 0.188 | 3.7 × 10−28 | 2.5 × 10−26 |

| ENSG00000034971 | Myocilin | MYOC | −3.184 | −0.522 | 9.8 × 10−11 | 1.3 × 10−9 |

| ENSG00000163735 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5 | CXCL5 | −3.282 | 4.576 | 1.0 × 10−72 | 5.4 × 10−70 |

| ENSG00000145283 | Solute carrier family 10 member 6 | SLC10A6 | −3.727 | −0.201 | 2.6 × 10−32 | 2.4 × 10−30 |

| ENSG00000168079 | Scavenger receptor class A member 5 | SCARA5 | −4.402 | 2.589 | 5.1 × 10−19 | 1.8 × 10−17 |

| ENSG00000163815 | C-type lectin domain family 3 member B | CLEC3B | −4.479 | 3.077 | 1.3 × 10−24 | 7.0 × 10−22 |

Fig. 2. Validation of up-regulated and down-regulated genes in a mouse model of TAC-induced HF.

(A to F) Phenotypic validation of TAC mouse model after 5 weeks of pressure overload. (A) Representative images of Picrosirius red staining. (B) Quantification of collagen disposition in heart cryosections. (C) mRNA expression of Collagen 1A1 (Col1a1) measured by qRT-PCR. (D) Representative echocardiographic images of LV structure and function. [(E) and (F)] Quantification of LV systolic function: (E) EF and (F) FS. (G and H) Validation of RNA-seq results using qRT-PCR: mRNA expression of the indicated (G) up-regulated and (H) down-regulated genes in sham and TAC-challenged mice. Values are presented as means ± SEM (nmice = 3 to 6[Sham], 4 to 6[TAC]). P values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

A functional analysis of DEGs was performed by mapping the significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes to the Gene Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org/), Disease Ontology terms (based on the HumanPSD database; https://genexplain.com/human-psd-database/) and the ontology of signal transduction and metabolic pathways from the TRANSPATH database (https://genexplain.com/transpath-database/) (17) integrated in the geneXplain/BioUML platform. As shown in Fig. 3A, the up-regulated gene profiles dictating fibroblast reprogramming into reactive profibrotic phenotype were mainly linked to metabolic processes and cellular homeostasis. The functional clusters specific to down-regulated genes in activated cardiac fibroblasts were abundantly related to cotranslational protein targeting to membrane, regulation of kinase activity, and cellular component organization and metabolism (Fig. 3B). Fibroblast-specific signaling pathways controlling cell profibrotic behavior were decrypted using data from TRANSPATH. As shown in Fig. 3C, pathway enrichment using the TRANSPATH decoded the top 15 fibrosis-driving pathways including hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) degradation and androgen receptor (AR) pathways in TGFβ-challenged cardiac fibroblasts. The most significant enriched TRANSPATH pathways of down-regulated gene profiles pinpointed a central position for p53, cholesterol metabolism, and synthesis pathways in TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Characteristics of up-regulated and down-regulated genes in aberrantly activated mouse cardiac fibroblasts.

Enriched GO (biological process) of (A) up-regulated and (B) down-regulated genes in naive and TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts. Enriched TRANSPATH Pathways (2020.1) of (C) up-regulated and (D) down-regulated genes in TGFβ-challenged cardiac fibroblasts versus naive cells.

Analysis of enriched transcription factor binding sites and composite regulatory modules

To delineate common molecular mechanisms in mouse and human cardiac fibroblasts undergoing fibrotic remodeling, we next analyzed the gene regulatory networks of the human orthologs of the identified mouse DEGs. The network of signal transduction and gene regulation of the cell orchestrates the activity of multiple transcription factors (TFs) to dictate cellular functions (18). To dissect the fibroblast-specific transcriptional and signal transduction regulatory network, we uncovered the transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) in the regulatory regions of the human DEGs by using the TF binding motif library of the TRANSFAC database (19). Using Genome Enhancer and Composite Module Analyst (CMA) tools, we identified combinations of TF motifs [composite regulatory modules (CRMs)] in the promoters of the human DEGs that serve as binding sites for specific TFs that regulate the expression of these genes upon TGFβ stimulation (fig. S1, A and B). We dissected the CRMs that coordinate up-regulation of gene expression, which include motifs for the following TFs: AR, CEBPA, CEBPB, NFATC2, CEBPD, POU2F1, LEF1, TFCP2, MYF6, and SMAD5 (tables S2 and S3). In the promoters of TGFβ-responsive human down-regulated genes, we identified CRMs containing motifs for the following TFs: TFCP2, MITF, CEBPB, TRIM28, NR3C1, FOSL1, NEUROD1, MYF6, MAFG, and HLTF (tables S2 and S4). The top 10 human up-regulated and down-regulated genes with identified most powerful CRMs in their promoters are labeled in table S5.

Finding master regulators of gene networks

Reconstruction of aberrantly affected gene regulatory networks and mapping of master regulators are the key challenges in dissecting the molecular mechanisms of complex diseases. Building on the generated patterns of key TFs, we further found common regulators of pathological gene expression in the aggressive fibrotic phenotype of fibroblasts (table S6). Through the constructed fibroblast-specific networks, we pinpointed DUSP9, AGT, AGTR2, MTUS1, PTPN6, and PLK2/3 as master regulators driving TGFβ-triggered fibroblast behavior dictating fibrosis resolution (table S6).

These master regulators are stated as key candidates for therapeutic targets to tackle cardiac fibrosis due to their dominant impacts on regulation of intracellular pathways orchestrating fibroblast activation status. Last, we decoded the causal connections between the identified TFs, which play essential roles in up-regulation (Fig. 4) and down-regulation (Fig. 5) of DEGs, and identified master regulators governing the activity of TFs.

Fig. 4. Diagram of intracellular regulatory signal transduction pathways of up-regulated genes in TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts versus naive cells for top 5 master regulators.

Designations: pink rectangles, master regulators; light blue rectangles, TFs; green rectangles are intermediate molecules, which have been added to the network during the search for master regulators from the selected TFs. Orange and blue frames highlight molecules that are encoded by up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively.

Fig. 5. Diagram of intracellular regulatory signal transduction pathways of down-regulated genes in TGFβ-challenged cardiac fibroblasts for five top-ranking master regulators.

Designations: pink rectangles, master regulators; light blue and violet rectangles, entities related to TFs; green rectangles are intermediate molecules, which have been added to the network during the search for master regulators from the selected TFs. Orange and blue frames highlight molecules that are encoded by up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively.

Building on the identified patterns of key TFs, we further identified common regulators of pathological gene expression in the aggressive fibrotic phenotype of fibroblasts (table S6).

Identification of potential drugs

Considering that TGFβ is a common cardinal driver of fibrosis-associated heart pathologies, we next transposed the fibroblast-specific networks to a drug repositioning strategy in a human heart disease scenario. To generate a list of known drugs, we leveraged the HumanPSD database, which integrates a wealth of data relevant to the function of human proteins, targets, and clinical trials in heart diseases. Table 2 shows the top 20 druggable master regulators from the HumanPSD and PASS libraries predicting drug targets for the treatment of fibrosis-associated heart pathologies (full lists are available in tables S7 and S8). We uncovered that the top-ranked ITGAL (HumanPSD) and DUSP9 (PASS) are the most promising druggable targets in cardiac fibrosis. In Fig. 6, we show the signal transduction cascades demonstrating a causative relationship between TGFβ-triggered up-regulation of integrins (primarily ITGAL) and activation of respective TFs, which, in turn, bind to their colocalized binding sites in the promoters of a number of genes, thereby enhancing their expression. In addition, we performed a benchmarking analysis to compare the performance of our Genome Enhancer pipeline with the widely used LINCS (through https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr) connectivity mapping approach. As shown in fig. S2, we constructed a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using a curated list of known antifibrotic and cardiovascular drugs, defined as those Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved or in phase 3+ clinical trials. These served as the gold standard positive control set. We then evaluated the ability of Genome Enhancer and LINCS–based predictions to rank these compounds within their respective outputs. The comparative analysis demonstrated the advantage of a causal, network-based analysis used by Genome Enhancer over correlation-driven approaches, specifically in diseases like fibrosis where regulatory architecture plays a critical role.

Table 2. Master regulators—Potential drug targets predicted using the HumanPSD and PASS databases.

The column Druggability score contains the number of drugs that are potentially suitable for inhibition (or activation) of the target. Total rank is the sum of the ranks of the master molecules sorted by key node score, CMA score, and transcriptomics data.

| Ensembl ID | Name | Gene description | Druggability score | Log2FC | Total rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanPSD | |||||

| ENSG00000005844 | ITGAL | Integrin subunit alpha L | 8.0 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000101182 | PSMA7 | Proteasome subunit alpha 7 | 3.0 | 0.34 | 295 |

| ENSG00000140564 | FURIN | Furin, paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme | 2.0 | 0.51 | 403 |

| ENSG00000171608 | PIK3CD | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit delta | 3.0 | 0.26 | 448 |

| ENSG00000165731 | RET | Retproto-oncogene | 7.0 | 0.83 | 452 |

| ENSG00000101336 | HCK | HCK proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase | 4.0 | 0.86 | 491 |

| ENSG00000158716 | DUSP23 | Dual specificity phosphatase 23 | 1.0 | 0.34 | 507 |

| ENSG00000010810 | FYN | FYN proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase | 2.0 | 0.53 | 515 |

| ENSG00000169398 | PTK2 | Protein tyrosine kinase 2 | 2.0 | 0.48 | 526 |

| ENSG00000198959 | TGM2 | Transglutaminase 2 | 1.0 | 1.23 | 536 |

| PASS | |||||

| ENSG00000130829 | DUSP9 | Dual specificity phosphatase 9 | 13.3 | 1.45 | 79 |

| ENSG00000145632 | PLK2 | Polo like kinase 2 | 0.7 | 1.91 | 269 |

| ENSG00000005844 | ITGAL | Integrin subunit alpha L | 12.7 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000005884 | ITGA3 | Integrin subunit alpha 3 | 3.3 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000091409 | ITGA6 | Integrin subunit alpha 6 | 3.3 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000144668 | ITGA9 | Integrin subunit alpha 9 | 0.7 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000161638 | ITGA5 | Integrin subunit alpha 5 | 4.4 | 1.07 | 273 |

| ENSG00000087191 | PSMC5 | Proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase 5 | 0.9 | 0.34 | 295 |

| ENSG00000095261 | PSMD5 | Proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase 5 | 0.9 | 0.34 | 295 |

| ENSG00000101182 | PSMA7 | Proteasome subunit alpha 7 | 0.9 | 0.34 | 295 |

Fig. 6. Signal transduction cascades regulating activation or deactivation of cardiac fibroblasts in response to TGFβ.

Signal transduction cascade that demonstrates the causative relationship between TGFβ-triggered up-regulation of integrins expression (pink node at the top of the network) and activation of respective TFs (blue nodes at the end of the network) that, in turn, bind to their colocalized binding sites in the promoters of genes leading to the up-regulation of their expression. Red arrow shows the position of TSSs in each gene. The promoter aria (from −1000 to +100 around the TSS) is shown with the TFBSs marked by the names of the respective PWMs of the TFs binding to these sites.

Collectively, these findings unlocked ITGAL and DUSP9 as promising therapeutic targets to tackle human cardiac fibrosis.

Because there are currently no effective pharmacological treatments for fibrosis, we further operated the expressions of master regulator targets to inquire drug prospects for repurposing in the heart disease motifs including cardiomyopathies, cardiovascular infections, endomyocardial fibrosis, myocardial infarction, endocarditis, and myocarditis. In this scenario, an artificial intelligence–driven strategy identified 367 candidate drugs predicted to counteract cardiac fibrosis in humans (table S9). Analysis of top-scoring drugs approved or used in clinical trials from the HumanPSD database pinpointed lovastatin, dasatinib, bosutinib, sorafenib, and nintedanib as powerful antifibrosis drug candidates (Table 3).

Table 3. List of top 5 drugs (from HumanPSD) approved or used in clinical trials for the application to treat human diseases and acting on master regulators revealed in our study.

| Drug ID | Name | Target names | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Drug rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB 00227 | Lovastatin | HDAC2 | Asthma, breast neoplasms, fibroma | Cardiovascular diseases, myocardial ischemia, arteriosclerosis | Cardiovascular diseases, myocardial ischemia, arteriosclerosis | Dyslipidemia, syndrome X, inborn genetic diseases | 18 |

| ITGAL | |||||||

| DB 01254 | Dasatinib | LCK | Adenocarcinoma, brain abscess, breast neoplasms | Adenocarcinoma, brain abscess, breast neoplasms | Lymphoid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia | Lymphoid leukemia, myeloid leukemia | 23 |

| SRC | |||||||

| ABL1 | |||||||

| PDGFRB | |||||||

| YES1 | |||||||

| FYN | |||||||

| ABL2 | |||||||

| DB 06616 | Bosutinib | SRC | Acute kidney injury, breast neoplasms, non–small cell lung carcinoma | Brain abscess, breast neoplasms, cholangiocarcinoma | Myeloid leukemia | Myeloid leukemia | 25 |

| ABL1 | |||||||

| HCK | |||||||

| MAP2K1 | |||||||

| LYN | |||||||

| DB 00398 | Sorafenib | KDR | Adenocarcinoma, adenoma, astrocytoma | Adenocarcinoma, adenoma, adrenocortical carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma, breast neoplasms, hepatocellular carcinoma | Hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, liver neoplasms | 26 |

| PDGFRB | |||||||

| FGFR1 | |||||||

| BRAF | |||||||

| RET | |||||||

| DB 09079 | Nintedanib | LCK | Adenocarcinoma, breast neoplasms, hepatocellular, carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma, angiomyoma, appendiceal neoplasms | Non–small cell lung carcinoma, colorectal neoplasms, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 27 |

| SRC | |||||||

| KDR | |||||||

| LYN | |||||||

| FGFR1 |

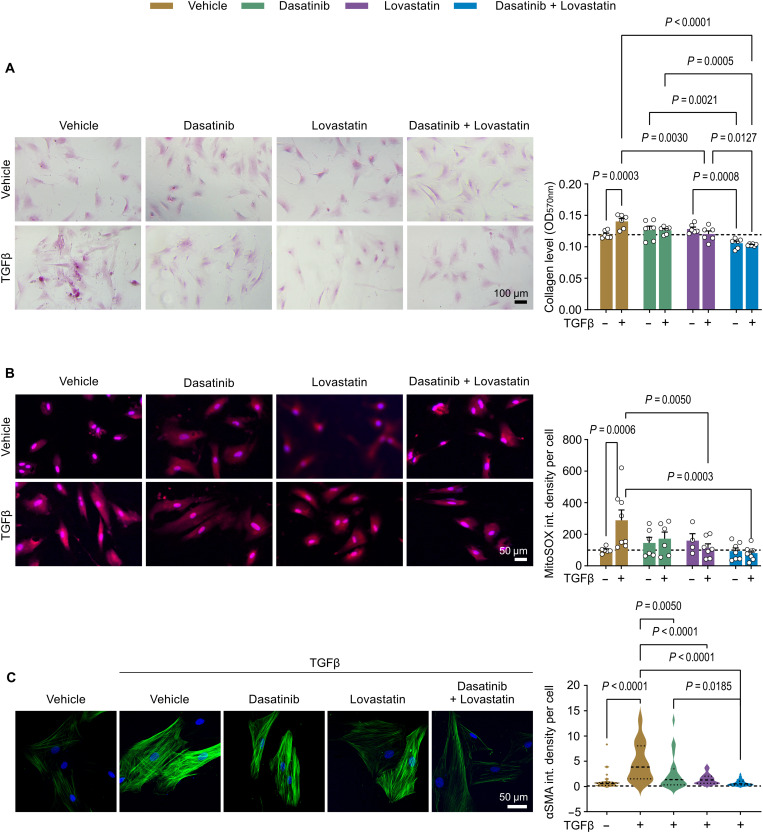

Validation of predicted drugs and their combination in cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF

To evaluate the antifibrotic potential of the top 2 predicted drug candidates, lovastatin and dasatinib, we next performed functional validation studies in primary cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF. We evaluated the effects of 1 μM lovastatin, 5 nM dasatinib, or their combination on collagen production and mitochondrial ROS generation in TGFβ-challenged human cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 7). Dose selection and dose justification were based on evaluating cellular survival in combination with gene expression profiles involved in the fibrotic responses (fig. S3). In TGFβ-exposed human fibroblasts, dasatinib-treated cells showed a tendency to decrease TGFβ-triggered collagen production, whereas lovastatin significantly reduced collagen accumulation (Fig. 7A). We demonstrated that the drug combination exhibited strong inhibition of fibroblast collagen deposition in activated cardiac fibroblasts. Furthermore, we found that combined treatment with lovastatin and dasatinib significantly decreased mitochondrial ROS levels in living TGFβ-challenged human fibroblasts (Fig. 7B). We also found that the drug combination exhibited strong inhibition of αSMA deposition in activated cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. Collagen and mitochondrial ROS production inhibition by drug candidates and their combination in TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF.

(A and B) Analysis of the TGFβ-activated fibrogenic phenotype in human primary cardiac fibroblasts treated with 5 nM dasatinib, 1 μM lovastatin, or a combination of 5 nM dasatinib and 1 μM lovastatin. Cells were starved for 2 hours in 0.5% serum-containing medium, pretreated with the indicated doses of the drugs for 20 min, and stimulated with TGFβ during the indicated times. (A) Collagen production after 72-hour exposure to TGFβ (10 ng/ml). Left: Representative images of Picrosirius red staining. Right: Quantifications of total collagen content by measuring the 570-nm absorbance after eluting the Sirius Red deposit in cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF (nwell per patient = 2; npatient = 3). (B) MitoSOX-detected mitochondrial ROS release after 1-hour exposure to TGFβ (10 ng/ml). Left: Representative images of MitoSOX immunofluorescence staining in red. Right: Quantifications of MitoSOX signals in cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF (n = 4 to 9 fields of 6.25 mm2 from three patients per group). Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI. Values are the means ± SEM; P values are calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. (C) Fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition after 24 hours of TGFβ. Left: Representative confocal images of immunofluorescence staining of αSMA in green. Right: Quantifications of αSMA expression. Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI (n = 17 to 43 cells from three patients per group).

DISCUSSION

Strategy to overcome the hurdles to treat fibrosis is a major unmet clinical need due to the lack of effective antifibrotic therapies. In this study, we unlocked the molecular signatures of fibroblast activation dictating aberrant cardiac fibrosis and identified druggable targets and drug candidates for therapeutic intervention. We found the distinct transcriptome fingerprint of naive and aberrantly activated cardiac fibroblasts linked to phenotypic alterations. By transposing mouse transcriptomics to humans, we decrypted common molecular determinants orchestrating fibroblast behaviors in fibrosis priming. Through constructed fibroblast-specific transcriptional networks, we uncovered druggable antifibrotic targets relevant to patients with HF. A computational drug repurposing strategy predicted and prioritized drug candidates that can potentially blunt excessive cardiac fibroblast activation. Last, we functionally evaluated the antifibrotic potential of two top-ranking drug candidates, lovastatin and dasatinib, and their combination on primary cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HF.

Fibroblasts have a remarkable capacity for phenotypic plasticity, which enables them to adopt distinct phenotypes during cardiac remodeling (20). Dynamic cell phenotypic switching, particularly the change from naïve to aggressive fibrogenic states, is crucial for myocardial remodeling because they enable fibroblasts to acquire different phenotypes in response to environmental variation (20). The ability of fibroblasts to display variable magnitudes of phenotype is a common signature in fibrosis-associated diseases including HF, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, chronic kidney diseases, and cystic fibrosis (21). Fibroblasts, functionally and transcriptionally heterogeneous across and within organs, operate as primary architects of the tissue microenvironment, which plays a crucial role in organ integrity (22). In line with this, single-cell RNA-seq studies have identified specific functional characteristics among fibroblast phenotypes and have shown that ECM production and immunoregulatory functions are segregated into distinct fibroblast populations (22). Aiming to bridge molecular features and phenotype-specific functions of cardiac fibroblasts, our study identified causal networks linking cell aggressive fibrogenic behaviors with the molecular architecture in cardiac fibrosis resolution. We dissected DUSP9, AGT, AGTR2, MTUS1, PTPN6, and PLK2/3 as master regulators driving TGFβ-triggered fibrogenic behavior in fibroblasts, dictating myocardial fibrosis resolution. Future studies must incorporate larger, organ-specific datasets and integrative approaches combining single-cell analysis, spatial transcriptomics, and functional assays.

TGFβ signal transduction can modulate diverse cellular responses and is particularly critical for cardiac fibrosis. Recent advances in decoding the molecular architecture of TGFβ signaling cascades and their cross-talk with other pathways have led to a more coherent roadmap of the programs governed by TGFβ (10). TGFβ signaling is primarily mediated through the Smad family of TFs but also engages in Smad-independent pathways (10). In addition, TGFβ signaling operates as a major orchestrator of immune responses, notably by regulating the activation of T cells through the induction of immunoregulatory protein expression (programmed cell death protein 1, indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase, galectin 9, etc.) contributing to the immunosuppressive environment (23–25). The importance of T cell populations has been highlighted in fibrotic remodeling occurring across different models of cardiac failure (26). Therefore, it will be essential to investigate whether the master regulators identified in our study have an effect on fibrotic remodeling mediated by immune-fibroblast cross-talk.

Dissection of regulatory pathways governing cardiac fibroblast behaviors in pathological context is fundamental to gain insight into fibrosis-associated heart diseases. Using the TRANSPATH database, our comprehensive analysis of RNA-seq dataset identified AR, CEBPA, CEBPB, TFCP2, and MITF as the main regulators of the profibrotic gene expression program in cardiac fibroblasts. Among them, CEBPA, CEBPB, and AR have traditionally been described as decisive factors regulating the expression of genes involved in differentiation, proliferation, and survival (27–30). The critical importance of CEBPA, CEBPB, MITF, AR, and TFCP2 has been largely demonstrated in cancer pathophysiology and cancer development (31–35). Recent studies indicate that CEBPA is involved in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia and hepatocellular carcinoma (31). Patients with CEBPA mutations have a longer remission duration and survival time than patients without mutations (35), which suggests a connection with a favorable course of disease progression. AR signaling has a pivotal role in breast carcinogenesis, indicating the importance of hormonal balance in women, and the potential clinical relevance of serum androgen and AR in prediction of breast cancer and selection of breast cancer therapy (36) is still insufficient. Several reports have pinpointed a capital role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the reactive pathologic scenarios (37, 38). In a mouse model, loss of stromal AR was reported to limit prostate cancer lesions, whereas, in human tumors, lower stromal AR expression was associated with depress in cancer cell differentiation and poor prognosis (39). A previous study has pinpointed that MITF is a melanoma susceptibility gene and emphasized the usefulness of whole-genome sequencing to identify novel rare variants linked to disease state (40). TFCP2 was first identified as one of the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (41), however, it has recently been stated that TFCP2 is involved in tumorigenesis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colon cancer (42). In our study, we provide the evidence that CEBPA, CEBPB, MITF, AR, and TFCP2 are the first line arbitrators in the regulation of metabolic responses, kinase activity and organization of cellular components in TGFβ-activated cardiac fibroblasts. However, further studies are needed to dissect the functional contribution of CEBPA, CEBPB, MITF, AR, and TFCP2 to fibrosis-associated cardiovascular manifestations.

Network-based approaches are emerging as powerful tools for unlocking the complexity of the genotype-phenotype relationships modulating disease scenarios. Characterizing the behavior of identified genes in biological networks can dissect disease mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Construction of fibroblast-specific regulatory network architecture revealed that ITGAL, PSMA7, FURIN, DUSP9, and PLK2 are the most promising and druggable molecular targets to blunt cardiac fibrosis. Several experimental and clinical studies have previously reported that aberrations and dysregulations of ITGAL, PSMA7, FURIN, DUSP, and PLK2 contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammation and immune-dysfunctional disorders in different organ systems (43–47). In this context, regulation of the fibro-inflammatory status of fibroblasts by ITGAL, PSMA7, FURIN, DUSP9, and PLK2 can be decisive in fibrotic tissue remodeling linked to decline in cardiac function. Further studies are needed to decode the functions of these immunomodulatory arbitrators in cardiac fibrosis.

The emergence of large-scale genomic data provides wide opportunities for drug discovery and repositioning. In this work, we introduced a computational approach for drug target prediction and drug repositioning starting from sets of fibrosis-specific deregulated genes as the molecular pointers of human heart complications. In our study, we uncovered the master regulators in the gene regulatory and signal transduction networks as drug targets and identified top 5 candidate drugs that may counteract cardiac fibrosis: lovastatin, dasatinib, bosutinib, sorafenib, and nintedanib. Notably, in chronic kidney diseases, lovastatin facilitates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the glomeruli by suppressing oxidative stress and TGFβ signaling (48). In this regard, our results open a challenging translational gap, for which a key aspect is the selection of the optimal therapeutic modality for translating advances in knowledge of fibrosis-associated pathologies into effective clinical destination. In a disease-related scenario, several cardiovascular drugs have already conferred on the new indications, such as propranolol for infantile hemangioma, beta-blockers for migraine, and minoxidil for androgenic alopecia (49, 50).

A network-based deep learning model for drug-target interactions predicted the potential candidate compounds for antifibrosis in a prioritized scale. Our study decoded tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) dasatinib and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor lovastatin as the efficient antifibrotic hit compounds. TKIs represent a milestone in cancer therapy. Recently, TKIs have been repurposed to treat noncancer diseases, such as autoimmune arthritis (51). Dasatinib is a second-generation TKI for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. To date, dasatinib exhibits a more remarkable and extended kinase inhibitory potency than first-generation TKIs on autoimmune arthritis (52). In a murine model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, dasatinib prevented liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis by attenuating lipogenesis and inducing macrophage polarization (53). Moreover, TKIs can ameliorate insulin antilipolytic activity, thereby reducing the mobilization of free fatty acids (54). In the dose optimization study, dasatinib (100 mg, once daily) was not associated with any incidence of severe HF or pericardial effusion in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (55). Nonetheless, whether dasatinib can halt or reverse cardiac fibrosis in patients with HF remains unknown. In the validation experiments, we provide the evidence that the low dose of dasatinib is effective to blunt collagen production and ROS in aberrantly activated human cardiac fibroblasts. We also experimentally confirmed the antifibrosis potential of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor lovastatin. Lovastatin has been FDA-approved to treat hypercholesterolemia. Notably, we revealed that combined treatment with lovastatin and dasatinib reduced mitochondrial ROS production, suggesting that collagen-suppressive powerful properties of drug synergy may be related to increased resistance to oxidative stress in activated phenotype of cardiac fibroblasts. Oxidative stress is inherent in abnormally activated cells and may be responsible for the aggressive fibroblast behavior in fibrotic program. Further studies in animal models are required to establish an ROS-dependent component in fibroblast dysfunction leading to fibrotic tissue remodeling. As suggested by congruent directionally favorable changes based on the antifibrosis motifs and cardiac function improvement of combined drug treatment in human cardiac fibroblasts, we propose that lovastatin-dasatinib combination can offer a powerful potential to tackle reactive cardiac fibrosis. This repurposed drug strategy can move through clinical trials more quickly, offering clinical applications for the treatment of patients with HF and address a wider range of fibrosis-associated diseases. However, among its potential, this approach encounters hurdles concerning efficacy and regulatory pathways that demand rigorous evaluation of drug dose optimization. In patients with HF, a drug repurposing strategy to blunt cardiac fibrosis requires careful consideration of its complexities to maximize benefits and minimize risks. Being manually curated, the HumanPSD database and PASS training set are inherently more populated with data on well-characterized genes and high-interest diseases such as cancer and inflammation, potentially skewing drug prioritization. To address this, in our work, we filtered outputs specifically for cardiac- and fibrosis-related terms, enhancing context relevance. Last, clinical trials will be required to validate the anticipated clinical benefit of combined treatment with lovastatin and dasatinib for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis and left ventricular (LV) remodeling.

To bridge the translational gap between preclinical and clinical research, animal models are essential. However, in many cases, mouse models have failed to be predictive. Introducing phenotypic and genomic insights into mouse models allow for unique opportunities to reveal the molecular basis underlying human dose-dependent drug responses and disease evolution. Nevertheless, the limitations of in vivo disease models often restrict the translation of data from preclinical to clinical settings in the development of drugs intended for human destination.

In conclusion, constructing fibroblast-specific networks revealed molecular fingerprinting of aberrant fibrotic remodeling and direct to innovative computational approach for drug discovery and repositioning in cardiac fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures performed were approved by the institutional animal experimentation and INSERM ethics committee. Experiments were conducted according to the French veterinary guidelines and those formulated by the European Community for experimental animal use (APAFIS#2019100115162970). Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were used as experimental animals (Envigo RMS, Gannat, France). All animals were kept under stable microenvironment conditions (25° ± 1°C), with alternating 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycles and received standard laboratory food and water.

Mouse cardiac fibroblasts

Mouse cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from adult male C57BL/6J mice as previously described (16). Briefly, hearts were excised and minced, followed by digestion in a digestion buffer containing Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; H8264, Sigma-Aldrich), bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), Pancreatin NB (0.5 mg/ml, #31442, Serva), and Collagenase NB4 (0.1 mg/ml, #17454.01, Serva). The digestion was performed at 37°C over four consecutive rounds. After each round, the cell suspension was collected and centrifuged at 300g for 5 min. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium)/F-12 medium (D6434, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (20 U/ml), streptomycin (20 μg/ml), and 2 mM glutamine and cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Adherent cells were characterized at passage 1 using immunofluorescence microscopy and confirmed to be positive for vimentin and negative for CD31. Fibroblasts up to passage 3 were used for all experiments.

To induce a fibrotic response, cardiac fibroblasts were treated with TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml), referred to as TGFβ (Sigma-Aldrich), prepared as a stock solution in sterile water. Water alone was used as a control. Treatment durations are specified in the relevant figure legends.

Sirius Red staining and fibrosis quantification

Following treatment, cardiac fibroblasts were fixed in methanol and stained with 0.1% Sirius Red solution (Sigma-Aldrich, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sirius Red was solubilized in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide, and the optical density was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer.

For tissue fibrosis detection, 10-μm-thick cardiac cryosections were stained with Sirius Red using a standard protocol to visualize interstitial collagen. Quantification of cardiac fibrosis was performed using Fiji software.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cultured cardiac fibroblasts were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100. After blocking in 1% BSA, cells were incubated for 1 hour with primary antibodies against αSMA (1:200, #sc-32251, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or Col1A1 (1:400, #91144S, Cell Signaling Technology). This was followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488 or 555–conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam). Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Leica DMi8 microscope equipped with a 20x objective, and fluorescence intensity was quantified using Fiji software.

Mitochondrial superoxide anion detection

Mitochondrial superoxide anion production was measured using MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen), a cationic dihydroethidium derivative that selectively reacts with superoxide anions in the mitochondrial matrix. MitoSOX Red enters mitochondria, where it is oxidized by superoxide but not by other ROS- or reactive nitrogen species-generating systems. Once oxidized, MitoSOX Red binds to nucleic acids in mitochondria/nucleus, producing strong red fluorescence. MitoSOX Red can be used as a fluorescent indicator to specifically detect superoxide. In addition, superoxide dismutase (SOD) can prevent MitoSOX Red oxidation. After treatment with TGFβ (10 ng/ml for 1 hour), the culture medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed twice with PBS to remove residual medium. A 50-μl MitoSOX working solution (5 μM in basal medium) was added to the cells, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Leica DMi8 fluorescence microscope, and the intensity was quantified using Fiji software.

RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing

RNA-seq libraries were prepared according to Illumina’s protocol with some adjustments, using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit (reference no. 20020595). Briefly, mRNA was first selected from 1300 ng of total RNA using poly-T beads and then retrotranscribed to generate double-stranded cDNA. Compatible dual indexed adaptors were ligated, allowing the barcoding of the samples with unique dual indices. Twelve cycles of PCR were applied to amplify libraries, and a final purification step at 0.8X allowed to obtain 200– to 1000–base pair (bp) fragments. The quality of libraries, which were sequenced to a depth of at least 30 million reads, was assessed using the HS NGS kit on the Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Over 90% of reads have mapped in all samples.

RNA-seq profiling

RNA-seq was carried out on paired-end 100-bp reads of Illumina NovaSeq 6000 as previously described (56). Image analysis and base calling were performed using Illumina Real Time Analysis (3.4.4) with default parameters.

Gene expression analysis in naive (control) and TGFβ-stimulated cardiac fibroblasts isolated from three hearts was performed using the geneXplain/BioUML platform and the edgeR tool (R/Bioconductor package) integrated into our pipeline. EdgeR calculated log2FC (the logarithm to the base 2 of the fold change), P value, and adjusted P value (corrected for multiple testing) for the observed FC.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression was quantified using qRT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from cells lysed in RLT buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or from tissue samples using a phenol/chloroform-based protocol. RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations and purity were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For reverse transcription, 0.1 to 1 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with the Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. qRT-PCR was performed using the ONEGreen FAST qPCR Premix (Ozyme), with primers added at concentration of 300 nM.

The housekeeping genes Hprt and Rplp0 were used for normalization in mouse samples, whereas HPRT was used for human samples. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR are listed in table S1.

TAC surgery

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (6 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained during the surgical procedure using 2% isoflurane. Mice were mechanically ventilated, and the left thoracic cavity was accessed via a small incision at the second intercostal space.

TAC was performed under a dissecting microscope by placing a 7-0 Prolene suture around the ascending aorta. To standardize the degree of constriction, two knots were tied on the suture 1.5 mm apart, corresponding to the outer diameter of a 26-gauge needle. The suture was carefully passed around the ascending aorta, and the two knots were tied together to create the constriction.

Postoperative analgesia was provided via a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine (Buprecar, 100 μg/kg). Sham-operated mice underwent the same surgical procedure without constriction of the aorta.

All surgical procedures were performed by a single operator to ensure consistency. Mice were euthanized 5 weeks after TAC. Hearts were collected following deep anesthesia with pentobarbital.

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and underwent echocardiography in the supine position using a Vevo 2100 high-frequency high-resolution ultrasound system (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Electrocardiogram and heart rate were monitored using limb electrodes. Body temperature was measured using a rectal probe and maintained at 37°C. Chest hair was removed with a depilatory cream. The parasternal long-axis imaging, and short-axis B-mode and M-mode imaging were recorded. LV EF was obtained from the parasternal long-axis imaging by tracing the left ventricle in diastole and systole. FS was obtained from the parasternal short-axis M-mode imaging.

Databases used in the study

TFBSs in promoters and enhancers of DEGs were analyzed using known DNA binding motifs collected in the TRANSFAC library, release 2020.1 (geneXplain GmbH, Wolfenbüttel, Germany) (http://genexplain.com/transfac). The master regulator search uses the TRANSPATH database, release 2020.1 (geneXplain GmbH, Wolfenbüttel, Germany) (http://genexplain.com/transpath). A comprehensive signal transduction network of human cells is built by the software on the basis of reactions annotated in TRANSPATH. The information about drugs corresponding to identified drug targets and clinical trials references were extracted from HumanPSD database, release 2020.1 (https://genexplain.com/human-psd-database/). The Ensembl database, release Human88.38 (hg38) (http://www.ensembl.org), was used for gene ID representation, and GO (http://geneontology.org) was used for functional classification of the studied gene set.

Methods for the analysis of enriched TFBSs and composite modules

TFBSs in 5′ regulatory regions (promoters) of DEGs were analyzed using known DNA binding motifs. The motifs were specified using position weight matrices (PWMs) to get weights for each nucleotide in each position of the binding motif for a TF or TFs. TFBS enrichment in promoters was analyzed in comparison to a background sequence set, such as promoters of genes that were not differentially regulated under the experimental condition. Study and background sets were denoted briefly as “Yes” and “No” sets. In this work, we used a workflow considering promoter sequences of 1100 bp (−1000 to +100). The error rate was controlled by estimating the adjusted P value (using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure) in comparison to the TFBS frequency in randomly selected regions of the human genome (adj. P value < 0.01).

We used the CMA algorithm (57) to find CRMs in promoters of the up-regulated and down-regulated genes comparing them to the promoters of nonchanged genes (500 genes in the middle of the distribution of log2FC). For each of these two gene sets (“Yes” sets), we identified a CRM consisting of a cluster of 10 TF motifs (from the TRANSFAC database) enriched in the promoters of the gene set in comparison to the promoters of nonchanged gene (“No” set). Identification of the enriched CRMs was done with the help of genetic algorithm described in our previous article (57). The algorithm scans a sliding window of 200 to 300 bp in the proximal promoter areas [from −1000 to +100 bp around the transcription start site (TSS)] of the studied genes and computes the CRM that discriminates best promoters of the Yes set from the promoters of the No set (to minimize Wilcoxon P value) by optimizing the following parameters: selection of 10 motifs from the whole TRANSFAC library of more than 8000 motifs, an average width of the module (expressed as the sigma parameter of the normal distribution; see equation (1) in (57)], cutoffs of the motifs, and the number of best sites for each motif considered.

Methods for finding master regulators in networks

Master regulators were searched upstream of the identified TFs in reconstructed signaling pathways. The comprehensive signaling network of human cells was used for this search. The main algorithm of this search was published previously (17, 58). The main goal of the search was to find nodes in that signaling network that may serve as potential regulator of TFs found at the previous step of the analysis. Such nodes were taken into account as the most valuable drug targets because any interventions affecting such node may change the process of gene expression regulated by the identified TFs. In our analysis, the algorithm was used with the maximal radius of 12 steps upstream of each examined TF. The rate of errors was controlled by application of the algorithm 10,000 times to randomly generated sets of TFs of the same set size. The z-score and false discovery rate (FDR) value of ranks of each potential master regulator node were calculated on the base of random runs. The FDR threshold was chosen 0.05 to control the error rate.

Methods for analysis of pharmaceutical compounds

The optimal combinations of the identified master regulators (key nodes of the regulatory networks) that potentially can be targeted by pharmaceutical compounds were found using data from the HumanPSD database. The PASS software was used to predict potential drugs on the base of data on activities of chemical compounds (http://genexplain.com/pass/).

For analysis of known pharmaceutical substances, compounds that had at least one molecular target according to the HumanPSD data were selected. For sorting of the selected compounds, “Drug rank” was used. This rank is a sum of three ranks:

1) rank on the basis of “Target activity score” (T-scorePSD),

2) rank on the basis of “Disease activity score” (D-scorePSD), and

3) rank on the basis of clinical trials phases.

For calculation of the clinical trial phase rank, the maximum phase of clinical trials with the given compound was selected. The rank “Target activity score” (T-scorePSD) was calculated as follows

where T is the set of all targets corresponding to the compound intersected with the input list, |T| is the number of elements in T; AT is a set of all targets corresponding to the compound, and |AT| is the number of elements in it, w is a weight multiplier, rank(t) is a rank of a given target, and maxRank(t) is the maximal value of the rank(t) for all targets t in T.

The rank “Disease activity score” (D-scorePSD) was calculated according to the formula

where D is the set of the selected diseases, and D-scorePSD = 0 for empty D. P is the set of all known phases for each disease, and phase(d,p) is equal to the clinical phase number in the case if there were known clinical trials for the selected disease on this clinical phase or zero, otherwise.

Method for prediction of pharmaceutical compounds

High pharmacological efficiency and low toxicity are the main desirable characteristics of the drugs to be predicted. Structure–activity relationship/quantitative structure–activity relationship analysis was used to select chemical compounds and drugs from a comprehensive library containing 13,040 items with the calculated potential pharmacological activities, possible side toxic effects, and mechanisms of action. The selected compounds satisfied the following conditions:

1) Toxicity was below a chosen threshold (probability to be active as a toxic substance).

2) For all predicted pharmacological effects that corresponded to a set of user selected disease(s), Pa was greater than a chosen effect threshold.

3) There were at least two targets corresponding to the predicted activity mechanisms with the predicted Pa value greater than the chosen target threshold.

“Toxicity score” was selected as the maximal Pa value for all toxicities related to the examined compound. “Disease activity score” was chosen as the maximal Pa value for all activities of the compound related to the selected diseases. “Target activity score” (T-score) was calculated as follows

where M(s) is the set of activity mechanisms identified for the examined structure (specific threshold for activity mechanisms Pa was passed), G(m) is the set of targets (converted to genes) that corresponded to the given activity mechanism (m) for the examined compound, Pa(m) is the probability of the activity mechanism (m) to be active, IAP(g) is the invariant accuracy of prediction for a gene from G(m), and optWeight(g) is an optional weight multiplier for a gene. T is a set of all targets related to the compound intersected with the input list, and |T| is the number of elements in T; AT is a set of all targets related to the compound, |AT| is the number of elements in it, w is a weight multiplier. “Druggability score” (D-score) was calculated as according to the formula

where S(g) is the set of structures having a target from the target list, M(s,g) is the set of activity mechanisms (for the examined structure) that corresponded to the examined gene, and Pa(m) and IAP(g) are described above.

Construction of ROC curves for drug prediction accuracy and AUC calculation

To benchmark the predictive accuracy of drug repurposing methods, we constructed ROC curves comparing Genome Enhancer and LINCS in their ability to identify clinically relevant antifibrotic and cardiovascular drugs. The reference set of true positives consisted of compounds either FDA-approved or currently in phase 3 or higher clinical trials for cardiac fibrosis and cardiovascular diseases.

Each method’s ranked drug list was assessed for overlap with the reference set. According to prediction score threshold, drugs were classified as follows: True Positives (TP): correctly predicted known antifibrotic/anticardiovascular drugs; False Positives (FP): drugs predicted as relevant but not in the known reference set; False Negatives (FN): known drugs not captured above the threshold; and True Negatives (TN): drugs neither predicted as relevant nor part of the known reference list.

The True-Positive Rate (TPR) and False-Positive Rate (FPR) were computed for each threshold using the following formulas

ROC curves were generated by plotting TPR against FPR across varying score cutoffs. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule, which numerically integrates the area under the ROC curve by summing trapezoids formed between successive ROC points.

Human tissue collection and human cardiac fibroblast isolation

Human myocardial tissues were obtained from patients with advanced HF undergoing implantation of LVAD (left ventricular assist device). During the surgical procedure, the myocardium inside the sewing ring positioned at the apex of the heart for the insertion of the inflow cannula is removed using a coring device. This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study, in accordance with approval by the local ethics committee in Toulouse (CPP SOOM II) under the reference CPP2-2-16-08.

Human cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from three patients as previously described (15). Myocardial tissue-derived cardiac fibroblasts were cultured in MEMα (32561, Gibco) with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The medium was changed every 2 days, and cells were passaged at 80 to 90% confluency. The purity of isolated cardiac fibroblasts exceeds 92% as assessed by positive vimentin expression and negative CD31 expression. After reaching confluency in passage 2, cells were used for all experiments. Cells were pretreated with lovastatin, dasatinib, or drug combination 20 min prior cell exposure to TGFβ (10 ng/ml). Dose selection for lovastatin, dasatinib, or their combination was guided by the assessment of cell viability, well-designed dose-response curves, and IC50 (median inhibitory concentration) determination (fig. S4).

Cell viability and confluence determination

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma-Aldrich]. Cells were incubated with MTT solution (at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C, allowing the conversion of MTT to formazan by metabolically active cells. The formazan crystals were then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. The optical density (OD) values were used to determine cell viability, which was expressed as a percentage relative to the control group.

Confluence was determined using the IncuCyte live-cell imaging system (Sartorius) at ×20 magnification. Images were captured, and the percentage of the culture area covered by cells was quantified automatically using the IncuCyte software.

Statistical analyses for in vitro and in vivo studies

All in vitro experiments were performed in at least three independent replicates. Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± SEM. For comparison of two groups, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was applied. For comparison involving three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test, or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was performed as appropriate. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.2, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

All statistical analyses included multiple testing corrections, and adjusted P values are reported throughout the manuscript. Specifically, for RNA-seq differential expression analyses, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was applied via the edgeR package to control the FDR. For TFBS enrichment and composite module analyses, FDR correction was similarly applied to comparisons between foreground and background promoter sets.

Effect sizes are included in all result tables, with metrics adapted to the type of analysis. For TFBS enrichment analyses, effect size is expressed as the “Yes/No ratio”: the ratio of TFBS frequency in DEGs (foreground) versus background genes, reflecting relative enrichment. For gene expression, log2 FC values are provided alongside FDR-corrected P values. For drug prioritization analyses, metrics such as the T-score, D-score, and Druggability score serve as standardized effect measures of predicted relevance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the GeT-Santé facility (I2MC, Inserm, Génome et Transcriptome, GenoToul, Toulouse, France) for the advice and technical contribution to the RNA-seq experiments. Our special thanks to D. Calise for TAC surgery and D. Marsal for excellent animal care skills.

Funding: This work was supported by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) (O.K.), National Programme PAUSE (S.K. and L.S.), and European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101073386 (GlioResolve) (A.Ka.) and no. 101073334 (Chrom_rare) (D.S.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: J.R., A.Ke., O.K., C.L., and N.P. Methodology: J.R., A.Ke., I.M., O.K., C.L., N.P., A.Ka., and D.S. Software: A.Ke., O.K., A.Ka., and D.S. Validation: J.R., A.S., O.K., and C.L. Formal analysis: J.R., R.K., A.Ke., I.M., A.S., O.K., C.L., A.Ka., and D.S. Investigation: L.S., M.C., J.R., R.K., S.K., A.Ke., I.M., A.S., O.K., C.L., and N.P. Resources: A.Ke., O.K., and C.L. Data curation: R.K., A.Ke., I.M., and O.K. Writing—original draft: M.C., R.K., and O.K. Writing––review and editing: M.C., J.R., R.K., A.Ke., I.M., O.K., and C.L. Visualization: R.K., A.Ke., O.K., C.L., and N.P. Supervision: J.R., A.Ke., and O.K. Project administration: A.Ke. and O.K. Funding acquisition: O.K. and A.Ke.

Competing interests: A.Ke. is employed as the chief scientific officer at GeneXplain GmbH (Germany). O.K., A.Ke., and J.R. are inventors on patent WO/2023/175136, “Combination of dasatinib and lovastatin for use in methods for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis”; the organization issuing the patent: INSERM TRANSFERT; the date of publication: 21 September 2023; CPC: A61K 31/366, A61K 31/506, A61P 9/00. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S4

Tables S1, S2, S5, and S6

Legends for tables S3, S4, and S7 to S9

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S3, S4, and S7 to S9

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gyöngyösi M., Winkler J., Ramos I., Do Q.-T., Firat H., McDonald K., González A., Thum T., Díez J., Jaisser F., Pizard A., Zannad F., Myocardial fibrosis: Biomedical research from bench to bedside. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 177–191 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki T., Fukumoto Y., Sugimura K., Oikawa M., Satoh K., Nakano M., Nakayama M., Shimokawa H., Prognostic impact of myocardial interstitial fibrosis in non-ischemic heart failure—Comparison between preserved and reduced ejection fraction heart failure. Circ. J. 75, 2605–2613 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assomull R. G., Prasad S. K., Lyne J., Smith G., Burman E. D., Khan M., Sheppard M. N., Poole-Wilson P. A., Pennell D. J., Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 1977–1985 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulati A., Jabbour A., Ismail T. F., Guha K., Khwaja J., Raza S., Morarji K., Brown T. D. H., Ismail N. A., Dweck M. R., Di Pietro E., Roughton M., Wage R., Daryani Y., O’Hanlon R., Sheppard M. N., Alpendurada F., Lyon A. R., Cook S. A., Cowie M. R., Assomull R. G., Pennell D. J., Prasad S. K., Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA 309, 896–908 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travers J. G., Kamal F. A., Robbins J., Yutzey K. E., Blaxall B. C., Cardiac fibrosis: The fibroblast awakens. Circ. Res. 118, 1021–1040 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baues M., Dasgupta A., Ehling J., Prakash J., Boor P., Tacke F., Kiessling F., Lammers T., Fibrosis imaging: Current concepts and future directions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 121, 9–26 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bektik E., Fu J.-D., Ameliorating the fibrotic remodeling of the heart through direct cardiac reprogramming. Cells 8, 679 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gourdie R. G., Dimmeler S., Kohl P., Novel therapeutic strategies targeting fibroblasts and fibrosis in heart disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 620–638 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotta Y., Uchiyama K., Takagi T., Kashiwagi S., Nakano T., Mukai R., Toyokawa Y., Yasuda T., Ueda T., Suyama Y., Murakami T., Tanaka M., Majima A., Doi T., Hirai Y., Mizushima K., Morita M., Higashimura Y., Inoue K., Fukui A., Okayama T., Katada K., Kamada K., Handa O., Ishikawa T., Naito Y., Itoh Y., Transforming growth factor β1-induced collagen production in myofibroblasts is mediated by reactive oxygen species derived from NADPH oxidase 4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 506, 557–562 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng Z., Fan T., Xiao C., Tian H., Zheng Y., Li C., He J., TGF-β signaling in health, disease and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 61 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bale S., Verma P., Yalavarthi B., Scarneo S. A., Hughes P., Amin M. A., Tsou P.-S., Khanna D., Haystead T. A., Bhattacharyya S., Varga J., Pharmacological inhibition of TAK1 prevents and induces regression of experimental organ fibrosis. JCI Insight 8, e165358 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreutzer F. P., Meinecke A., Mitzka S., Hunkler H. J., Hobuß L., Abbas N., Geffers R., Weusthoff J., Xiao K., Jonigk D. D., Fiedler J., Thum T., Development and characterization of anti-fibrotic natural compound similars with improved effectivity. Basic Res. Cardiol. 117, 9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia Z.-C., Yang X., Wu Y.-K., Li M., Das D., Chen M.-X., Wu J., The art of finding the right drug target: Emerging methods and strategies. Pharmacol. Rev. 76, 896–914 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue H., Li J., Xie H., Wang Y., Review of drug repositioning approaches and resources. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14, 1232–1244 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosomi K., Fujimoto M., Ushio K., Mao L., Kato J., Takada M., An integrative approach using real-world data to identify alternative therapeutic uses of existing drugs. PLOS ONE 13, e0204648 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pchejetski D., Foussal C., Alfarano C., Lairez O., Calise D., Guilbeau-Frugier C., Schaak S., Seguelas M. H., Wanecq E., Valet P., Parini A., Kunduzova O., Apelin prevents cardiac fibroblast activation and collagen production through inhibition of sphingosine kinase 1. Eur. Heart J. 33, 2360–2369 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krull M., Pistor S., Voss N., Kel A., Reuter I., Kronenberg D., Michael H., Schwarzer K., Potapov A., Choi C., Kel-Margoulis O., Wingender E., TRANSPATH: An information resource for storing and visualizing signaling pathways and their pathological aberrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D546–D551 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kel A., Boyarskikh U., Stegmaier P., Leskov L. S., Sokolov A. V., Yevshin I., Mandrik N., Stelmashenko D., Koschmann J., Kel-Margoulis O., Krull M., Martínez-Cardús A., Moran S., Esteller M., Kolpakov F., Filipenko M., Wingender E., Walking pathways with positive feedback loops reveal DNA methylation biomarkers of colorectal cancer. BMC Bioinformatics 20, 119 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matys V., Kel-Margoulis O. V., Fricke E., Liebich I., Land S., Barre-Dirrie A., Reuter I., Chekmenev D., Krull M., Hornischer K., Voss N., Stegmaier P., Lewicki-Potapov B., Saxel H., Kel A. E., Wingender E., TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: Transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D108–D110 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kel A., Thum T., Kunduzova O., Targeting fibroblast phenotype switching in cardiac remodelling as a promising antifibrotic strategy. Eur. Heart J. 46, 354–358 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M., Wang L., Wang M., Zhou S., Lu Y., Cui H., Racanelli A. C., Zhang L., Ye T., Ding B., Zhang B., Yang J., Yao Y., Targeting fibrosis, mechanisms and cilinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 206 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhl L., Genové G., Leptidis S., Liu J., He L., Mocci G., Sun Y., Gustafsson S., Buyandelger B., Chivukula I. V., Segerstolpe Å., Raschperger E., Hansson E. M., Björkegren J. L. M., Peng X.-R., Vanlandewijck M., Lendahl U., Betsholtz C., Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination. Nat. Commun. 11, 3953 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batlle E., Massagué J., Transforming growth factor-β signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 50, 924–940 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park B. V., Freeman Z. T., Ghasemzadeh A., Chattergoon M. A., Rutebemberwa A., Steigner J., Winter M. E., Huynh T. V., Sebald S. M., Lee S.-J., Pan F., Pardoll D. M., Cox A. L., TGFβ1-mediated SMAD3 enhances PD-1 expression on antigen-specific T cells in cancer. Cancer Discov. 6, 1366–1381 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariathasan S., Turley S. J., Nickles D., Castiglioni A., Yuen K., Wang Y., Kadel E. E., Koeppen H., Astarita J. L., Cubas R., Jhunjhunwala S., Banchereau R., Yang Y., Guan Y., Chalouni C., Ziai J., Şenbabaoğlu Y., Santoro S., Sheinson D., Hung J., Giltnane J. M., Pierce A. A., Mesh K., Lianoglou S., Riegler J., Carano R. A. D., Eriksson P., Höglund M., Somarriba L., Halligan D. L., van der Heijden M. S., Loriot Y., Rosenberg J. E., Fong L., Mellman I., Chen D. S., Green M., Derleth C., Fine G. D., Hegde P. S., Bourgon R., Powles T., TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martín P., Sánchez-Madrid F., T cells in cardiac health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 135, e185218 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koschmieder S., Halmos B., Levantini E., Tenen D. G., Dysregulation of the C/EBPα differentiation pathway in human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 619–628 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura A., Hirai H., Yokota A., Kamio N., Sato A., Shoji T., Kashiwagi T., Torikoshi Y., Miura Y., Tenen D. G., Maekawa T., C/EBPβ is required for survival of Ly6C− monocytes. Blood 130, 1809–1818 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahim B., O’Regan R., AR signaling in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 9, 21 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mannelli F., Ponziani V., Bencini S., Bonetti M. I., Benelli M., Cutini I., Gianfaldoni G., Scappini B., Pancani F., Piccini M., Rondelli T., Caporale R., Gelli A. M. G., Peruzzi B., Chiarini M., Borlenghi E., Spinelli O., Giupponi D., Zanghì P., Bassan R., Rambaldi A., Rossi G., Bosi A., CEBPA-double-mutated acute myeloid leukemia displays a unique phenotypic profile: A reliable screening method and insight into biological features. Haematologica 102, 529–540 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du C., Pan P., Jiang Y., Zhang Q., Bao J., Liu C., Microarray data analysis to identify crucial genes regulated by CEBPB in human SNB19 glioma cells. World J. Surg. Oncol. 14, 258 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartman M. L., Czyz M., MITF in melanoma: Mechanisms behind its expression and activity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 1249–1260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z., Gao F., Shao Z., Xie H., Zhou L., Xu X., Zheng S., TFCP2 genetic polymorphism is associated with predisposition to and transplant prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2017, 6353248 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q., Deng Q., Chao H.-P., Liu X., Lu Y., Lin K., Liu B., Tang G. W., Zhang D., Tracz A., Jeter C., Rycaj K., Calhoun-Davis T., Huang J., Rubin M. A., Beltran H., Shen J., Chatta G., Puzanov I., Mohler J. L., Wang J., Zhao R., Kirk J., Chen X., Tang D. G., Linking prostate cancer cell AR heterogeneity to distinct castration and enzalutamide responses. Nat. Commun. 9, 3600 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wouters B. J., Löwenberg B., Erpelinck-Verschueren C. A. J., van Putten W. L. J., Valk P. J. M., Delwel R., Double CEBPA mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations, define a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with a distinctive gene expression profile that is uniquely associated with a favorable outcome. Blood 113, 3088–3091 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng J., Li L., Zhang N., Liu J., Zhang L., Gao H., Wang G., Li Y., Zhang Y., Li X., Liu D., Lu J., Huang B., Androgen and AR contribute to breast cancer development and metastasis: An insight of mechanisms. Oncogene 36, 2775–2790 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao C.-P., Chen L.-Y., Luethy A., Kim Y., Kani K., MacLeod A. R., Gross M. E., Androgen receptor in cancer-associated fibroblasts influences stemness in cancer cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 24, 157–170 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clocchiatti A., Ghosh S., Procopio M.-G., Mazzeo L., Bordignon P., Ostano P., Goruppi S., Bottoni G., Katarkar A., Levesque M., Kölblinger P., Dummer R., Neel V., Özdemir B. C., Dotto G. P., Androgen receptor functions as transcriptional repressor of cancer-associated fibroblast activation. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 5531–5548 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]