Abstract

Using a sample of 286 mothers and fathers from ethnically and socioeconomically diverse backgrounds, we tested the associations between the frequency and quality of parents’ shared book reading (SBR) with infants aged 9 months, and language skills of infants aged 18 months, and whether infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months mediated these associations. Frequency of SBR was parent-report and quality of SBR (i.e., number of reading strategies) and infants’ attention were coded from recorded SBR interactions at home. The majority of mothers and fathers reported reading to their 9-month-olds at least weekly, and mothers reported reading, on average, significantly more often than fathers. There was large variability in parents’ SBR quality ranging from 0 to 15 strategies per minute, with labelling being the most common. Path analysis showed that mothers’ SBR frequency at 9 months was significantly associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months, whereas, SBR quality by either parent was not significant. Infants’ attention did not mediate these associations. These findings suggest that early SBR is beneficial for language development and programmes targeting early language development should encourage both mothers and fathers to read often to their infants during the first year.

Keywords: diversity, fathers, infants, language development, path analysis, shared book reading

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The development of language skills is a central milestone of early childhood. Children who have difficulty either comprehending or producing language during the early years are at higher risk for school difficulties, including delays in reading, math skills and behaviour problems (Kastner et al., 2001; Matte-Landry et al., 2020). Although multiple factors, such as children’s physical and cognitive abilities, gender and biological factors contribute to early language development (e.g., Adani & Cepanec, 2019; Davidse et al., 2011; Iverson, 2010; Jimenez et al., 2020; Umek et al., 2008), one of the most significant environmental factors that promote language learning is children’s early home literacy environment (e.g., Bitetti & Hammer, 2016; Burgess et al., 2002; Farver et al., 2013; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014). In particular, shared book reading (SBR) between parents and young children has been robustly linked to children’s early language and literacy skills (e.g., Deckner et al., 2006; Mol et al., 2008; Wasik et al., 2016).

Extensive longitudinal evidence with preschool- and kindergarten-aged children indicates that children who are read to more often have better language and reading skills than children who are read to less often (e.g., Deckner et al., 2006; Hindman et al., 2008; Mol & Bus, 2011; Tompkins et al., 2017). Past research also shows that when SBR is of high quality, that is, when parents use a number of reading strategies, such as ask questions, elaborate the text, and label and describe the pictures in the book, children are more likely to learn new vocabulary (Barnes & Puccioni, 2017; Mol et al., 2008; Noble et al., 2019; Trivette et al., 2010; Wasik et al., 2016). In contrast, parents who just read the text to a child, while they expose the child to speech sounds and print, may not offer additional information about words and concepts that could scaffold the child’s language learning. When parents just read the text, it is likely that children would be less engaged in the reading or pay less attention to the book, which may be less beneficial for language skills (Fletcher et al., 2008; Lyytinen et al., 1998).

Despite the importance of reading to children, there are several limitations of this research. First, there is limited research on the frequency and quality of SBR with infants who are significantly related to language development, especially in the first year of life. The few studies that have assessed SBR between mothers and their infants find significant and positive associations between frequency during the first year and receptive and expressive language skills during the second year (Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005; O’Farrelly et al., 2018). To our knowledge, there is only one study that has assessed the quality of SBR with infants during the first year and its relation to language skills (Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). Prior research indicates that preverbal infants benefit from different types of language input compared to toddlers and preschoolers (i.e., labelling and repetition versus wh-questions and syntactically complex utterances; Rowe & Snow, 2020). Thus, given the encouragement parents receive from their paediatricians and other professionals to read to their infants, and the evidence that quality of SBR matters, understanding what ‘quality’ of SRB is for infants is an important research question (Cates et al., 2018; Klass et al., 2009). This information can inform programmes and practitioners (e.g., paediatricians, home visitors, and speech therapists) to educate parents in effective ways to read to their children. Therefore, one goal of this study is to investigate the frequency of SBR and the quality of SBR in the first year to assess whether they support language skills during the second year.

Next, extant research on SBR tends to focus on mothers’ reading behaviours and less so on fathers’ contributions, even though fathers’ frequency and quality of SBR with young children has been found to be related to children’s language skills (Duursma, 2016; Lyytinen et al., 1998; Malin et al., 2014; Teufl et al., 2019). The omission of fathers is problematic because their engagement with children in learning activities is uniquely related to various aspects of early child development, over and above mothers’ contribution (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2017, 2020; Leech et al., 2013; Pancsofar & Vernon-Feagans, 2010). Excluding fathers also provides an incomplete profile of young children’s home learning experiences and may overestimate the effect of mothers on developmental outcomes or over-look important effects of fathers. Therefore, another goal of this study is to examine both mothers’ and fathers’ frequency and quality of SBR with their infants.

Lastly, there is limited evidence on the mechanisms that explain why the frequency and quality of SBR during the first year might be related to infants’ language skills during the second year of life when rapid and substantial growth in language and cognitive skills occur (Ruben, 1997; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986). A potential mechanism through which SBR might matter for language development is infants’ attention. Infants who are read to more often and are read to with higher quality (e.g., a high number of reading strategies, such as labelling, elaborating, asking questions) may become more attentive to books and print than children who are not read to as frequently, or are read to with lower quality (i.e., few or no reading strategies; Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005; Malin et al., 2014). In turn, infants’ increased attention may help them more effectively match the words they hear to their referents in the book, thus supporting vocabulary learning (Masek et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2019). These indirect pathways from SBR to language outcomes have not been tested with infants. Therefore, the third goal of this study was to examine whether infant attention might mediate the association between the frequency and quality of SBR during infancy and language skills during the second year.

Guided by the bioecological and sociocultural perspectives (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Vygotsky, 1978), we used data from a NIH-funded longitudinal parenting intervention (McKee et al., 2021) to address the following research questions: (1) Are the frequency (i.e., how often infants are read to) and quality (i.e., number of reading strategies parents use during SBR) of maternal and paternal SBR with their 9-month-old infants associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months? And (2) Does infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months mediate the associations between maternal and paternal frequency and quality of SBR at 9 months and language skills at 18 months?

1.1. |. Theoretical background

We frame the current study using bioecological and sociocultural models that children acquire new skills through social interactions, such as SBR, with more advanced partners, such as parents, in the home environment (i.e., the microsystem; Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Vygotsky, 1978). During interactions, SBR facilitates active participation in reading, exposes children to a wide range of words and sentence structures that may not occur in daily speech, and gives children the opportunity to associate sounds with concepts and written language (Hoff-Ginsberg, 1991; Hood et al., 2008; Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005; Mol et al., 2008; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002, 2014). Research has shown that the frequency of SBR with young children is important for language development (Barnes & Puccioni, 2017; Duursma, 2014) and that SBR is more effective and more enjoyable when parents read in ways that scaffold children’s learning of new words (Hargrave & Sénéchal, 2000; Huebner & Meltzoff, 2005). Preverbal infants who are still learning to segment sounds into words may benefit from SBR because it gives them an opportunity to hear repeated labels and short phrases (Rowe & Snow, 2020). Studies on the quality of mothers’ and fathers’ SBR with infants have shown that a high number of reading strategies, such as labelling, clarifying and repeating utterances used by parents during SBR, are significantly associated with infants’ expressive and receptive language skills (Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019; Teufl et al., 2019).

Interactionist theories hypothesise that child-directed social interactions support early learning by enhancing infants’ attention during the interaction (Kuhl, 2007; Masek et al., 2021; Shneidman & Woodward, 2015). During SBR, parents provide meaningful language input (e.g., label and describe pictures, point out words), which attract their infants’ attention, focusing on the spoken and written language. In turn, infants’ heightened attention to the text and language spoken to them during SBR may help them to acquire receptive and expressive language skills.

1.2 |. Frequency of SBR during infancy in relation to language skills

Preschool- and kindergarten-aged children who are read to more often have better language skills than children who are read to less often (e.g., Barnes & Puccioni, 2017; Mol & Bus, 2011). Although, on average, infants are read to less often than older children (Cabrera et al., 2021; Jimenez et al., 2020; Raikes et al., 2006), especially by their fathers (Cabrera, Hofferth, et al., 2011), the frequency of mothers’ and fathers’ SBR with infants is significantly associated with later language skill (Dunst et al., 2012; Jimenez et al., 2020; Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005; Raikes et al., 2006). A small-scale study with White, middle-class families found that infants who were read to at 8 months by parents had better expressive language skills at 12 and 16 months compared to those who were not read to (Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005). Another small-scale study with an Irish White sample also found that mothers who read to their infants daily at 6 months had infants with better vocabulary comprehension and production at 12 months compared to mothers who did not report reading daily (O’Farrelly et al., 2018). Moreover, findings from a national study show that one-year-olds who were read to at least once per week by their mothers had greater receptive vocabulary at age 3 years than children who were read to less often than once per week, after controlling for SES, maternal race and ethnicity, and depressive symptoms (Jimenez et al., 2020). Overall, these studies show the benefit of frequent reading to infants for early language development.

1.3 |. Quality of SBR in relation to language skills

In addition to frequency of SBR, quality of SBR also explains some of the variability in early language skills (e. g., Deckner et al., 2006; Malin et al., 2014; Mol et al., 2008; Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). Studies with toddlers and preschoolers from diverse backgrounds have measured quality of SBR in various ways, including interactive reading strategies (Boyce et al., 2004), metalingual talk (Deckner et al., 2006; Malin et al., 2014), decontextualised talk (Hindman et al., 2008), or inferential questions and statements (Tompkins et al., 2017). For example, Hindman et al. (2008) measured the number of ‘decontextualised’ strategies (e.g., going beyond the information provided on the page) mothers used with preschoolers during SBR; Malin et al. (2014) measured high-quality SBR with toddlers as the number of ‘metalingual’ strategies (e.g., prompts, responses, recasts) mothers and fathers used during SBR. Following these practices, in this study, we operationalised SBR quality as the number of reading strategies parents used during SBR with their infants.

Extant evidence on the quality of SBR with toddlers and preschoolers shows that it is positively associated with children’s receptive and expressive vocabulary at preschool and kindergarten. For example, a small-scale study with White, middle-class parents showed that fathers’ use of questions, imitations, and feedback during SBR with their 15- to 27-month-old infants was positively correlated with mother-reported child expressive vocabulary (Blake et al., 2006). In another study with a small sample of low-income African American mothers and fathers, Malin et al. (2014) found that controlling for parental education and reading frequency, both mothers’ and fathers’ metalingual talk (e.g., recasts of child’s language, labels) during SBR at 24 months was positively associated with children’s receptive vocabulary at prekindergarten. A cross-sectional study with middle-to-upper-class Australian mothers and fathers found that mothers’ inquiring-clarifying utterances (e.g., Is that the cat?) during SBR were positively related to one-year-olds’ receptive skills and that fathers’ repeating-imitating utterances (e.g., repeating what the child said before) were positively related to children’s expressive skills (Teufl et al., 2019).

We are aware of only one study that has examined the contribution of SBR quality during the first year of life to early language development. Muhinyi and Rowe (2019) assessed the quality of SBR using a predominantly White sample from diverse SES and found that more questions (e.g., yes/no questions, tag questions, wh-questions) asked by mothers during SBR with their 10-month-olds was related to better pragmatic, expressive and receptive language skills of children at 24 months. However, further research is needed to better understand and measure ‘quality’ of SBR with preverbal infants. One of the challenges pertains to the conceptualisation of ‘high-quality’ SBR for infants. Preverbal infants are just beginning to segment sounds into words and babble, thus the most helpful input for them might be clear labelling and repetition of words and phrases rather than more elaborate reading strategies as used with toddlers and preschoolers (Rowe & Snow, 2020). Indeed, research shows that during SBR with infants, parents mostly use pointing or labelling to engage them, whereas parents of older children use more cognitively demanding strategies, such as asking wh-questions and elaborating on the text (Mol et al., 2008; Rowe et al., 2017). Another challenge is understanding how parents’ SBR with infants may be influenced by book type or text genre (Anderson et al., 2004; Luo et al., 2020; Pellegrini et al., 1990; Stadler & McEvoy, 2003). Some evidence with preschoolers indicate that when parents read non-narrative books (e.g., concept, expository or alphabet books), they tend to use more reading strategies than when they read narrative books (e.g., books with a storyline; Anderson et al., 2004; Pellegrini et al., 1990). Additionally, when parents read non-narrative books, they are more likely to teach preschoolers print concepts and phonological awareness than when they read narrative books, which induce more discussion on the content of the book (e.g., characters, events, connections with the child’s own experience; Stadler & McEvoy, 2003). Another study with four-year-olds from low-income, ethnic minority families showed that access to a variety of narrative books at home, but not concept books (e.g., colours, numbers, letters), was associated with mothers’ use of storyline questions during SBR (Luo et al., 2020). Therefore, the quality of SBR during infancy may also depend on the type of book parents read with their infants. In this study, we focus on the quality of SBR (i.e., the number of reading strategies of parents) during infancy using an age-appropriate non-narrative number book, and explore whether it is related to later language skills.

1.4 |. Infants’ attention during SBR as a mediator

Of interest to developmental science is the mechanism or process through which SBR matters for children’s language development. Previous studies show that children who are read to more often pay more attention during SBR and show stronger interest in the reading activity than children who are not read to as frequently (Fletcher et al., 2008; Lyytinen et al., 1998). Moreover, children who are engaged in high-quality interactions with their parents tend to make fewer attention shifts, have longer bouts of attention, and display better attentional control compared to infants who experience low-quality interactions (Mason et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2009; Miller & Gros-Louis, 2013; Weisleder et al., 2016). It appears that children who have longer stretches of attention have the opportunity to connect the language input provided by parents to what they pay attention to at the moment (Kuhl, 2007; Masek et al., 2021). Thus, a potential mechanism linking the frequency and quality of SBR to language skills could be infants’ attention during the reading activity.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that have empirically tested whether infants’ attention during SBR mediates the association between the frequency and quality of SBR and language outcomes. However, studies with toddlers provide evidence that children’s attention is a potential mediator. An earlier small-scale study found a concurrent correlation between mothers’ and fathers’ reading frequency with children at age 2 years and children’s reading interest (e.g., initiation and duration of reading) and between children’s reading interest and vocabulary production at age 2 years, although they did not test for a mediational pathway (Lyytinen et al., 1998). Fletcher et al. (2008) found that two-year-old children from predominantly low-income White families who were read to with higher quality (i.e., more labeling, expansions and questions) by their mothers had better joint attention (i.e., both child and mother attending to the book during SBR) than toddlers who were read to with lower quality (i.e., fewer reading strategies). Another study found that toddlers’ levels of interest during SBR (i.e., attention, affect and active participation) at 24 months fully mediated the association between mothers’ and fathers’ metalingual talk during SBR and children’s receptive vocabulary at prekindergarten (Malin et al., 2014). Based on this literature, we hypothesise that high-frequency and high-quality (i.e., high number of reading strategies) SBR would scaffold language learning indirectly by attracting infants’ attention to the content in the book and the ambient speech provided by parents, which would then support language learning.

1.5 |. The current study

Grounded in the bioecological and sociocultural theories (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Masek et al., 2021; Vygotsky, 1978), we investigate (1) whether the frequency and quality of mothers’ and fathers’ SBR with their infants at 9 months are associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months, and (2) whether infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months mediates these associations. We hypothesise that mothers’ and fathers’ frequency and quality of SBR at 9 months would be positively associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months (main effect hypothesis), and that mothers and fathers who read more frequently to their infants and engage in higher-quality SBR (i.e., use more reading strategies) at 9 months would have infants with increased attention during SBR, which, in turn, would be associated with better receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months (mediation effect hypothesis).

We address our research questions in a sample of ethnically and socioeconomically diverse families. The relation between frequency and quality of SBR and language development is not well-understood in infants in non-White families. Although some of the variability in the frequency and quality of SBR can be attributed to cultural practices and beliefs and language use (Boyce et al., 2004; Hammer et al., 2005; Jimenez et al., 2019; Melzi & Caspe, 2005), ethnic minority parents living in the United States, as any other parent living in the United States, are encouraged by their paediatricians and other professionals to read to their children from birth and as often as they can (Council on Early Childhood et al., 2014). Qualitative research has shown that ethnic minority parents want their children to succeed in the United States and engage in childrearing practices, such as SBR, that further that goal (Aldoney & Cabrera, 2016). Indeed, prior studies with ethnic minority mothers and fathers show that they engage in frequent reading with their children as young as 9 months (Cabrera et al., 2021; Malin et al., 2014). This study is intended to provide more evidence on the direct and indirect associations between SBR during infancy and early language skills in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of families, controlling for conceptually relevant covariates (e.g., parent education, infant language exposure) that may confound these associations.

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Study sample

We used data from a longitudinal English-Spanish bilingual parenting intervention that provided educational information about typical child development and effective parenting practices to parents through baby books (Cabrera & Reich, 2017; McKee et al., 2021). Eligibility criteria for the intervention project included: (1) children were first-born; (2) mothers and fathers were cohabiting with each other and the child at enrolment; (3) parents were literate at or above a first-grade level in English or Spanish and (4) parents reported household incomes below U.S. $75,000 at enrolment. All families lived in southern California and the Washington, D.C., metro areas. The sample of this study includes 286 mothers and fathers (143 families) who spoke English and/or Spanish during SBR with their infants at 9 months, and whose children have data on language skills at 18 months.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study sample. The majority of mothers and fathers self-identified as Hispanic or Latino (76% and 73%), followed by non-Hispanic African American (12% and 11%), non-Hispanic White (7% and 8%) and other (e.g., Asian, multiracial; 6% and 8%). Twice as many fathers (21%) than mothers (11%) reported less than a high school education, and mothers (25%) were almost twice as likely as fathers (14%) to have a 4-year college degree or above. In terms of household income, 40% of the sample reported house-hold incomes at or below U.S. $40,000, which is 200% of the federal poverty line for a family in 2017 when the intervention project started enroling parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). About half of the parents were born outside the U.S. More than 60% of infants lived in households where parents reported speaking only English or Spanish to them, and about 38% lived in households where parents reported speaking two (33% English and Spanish) or more languages to them. About half of the infants were boys.

TABLE 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

| Family/child (n = 143) |

Mothers (n = 143) |

Fathers (n = 143) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 108 | 75.5 | 104 | 72.7 | ||

| African American | 17 | 11.9 | 15 | 10.5 | ||

| White | 10 | 7.0 | 12 | 8.4 | ||

| Other (e.g., Asian, multiracial) | 8 | 5.6 | 12 | 8.4 | ||

| Parent education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 15 | 10.5 | 30 | 21.0 | ||

| High school | 28 | 19.6 | 36 | 25.2 | ||

| Some college | 64 | 44.8 | 57 | 39.9 | ||

| 4-year college degree or above | 36 | 25.2 | 20 | 14.0 | ||

| Parent nativity status | ||||||

| Born in the U.S. | 71 | 49.7 | 65 | 45.5 | ||

| Born outside the U.S. | 72 | 50.3 | 78 | 54.5 | ||

| Household incomeb | ||||||

| Below $22,000 | 12 | 10.3 | ||||

| $22,001 to $40,000 | 44 | 37.9 | ||||

| $40,001 to $75,000 | 52 | 44.8 | ||||

| Above $75,000 | 8 | 6.9 | ||||

| Infant language exposurec | ||||||

| English or Spanish only | 88 | 62.4 | ||||

| Two or more languages (e.g., English and Spanish) | 53 | 37.6 | ||||

| Infant gender | ||||||

| Boy | 69 | 48.3 | ||||

| Girl | 74 | 51.7 | ||||

| Study site | ||||||

| D.C. metro area | 67 | 46.9 | ||||

| Southern California | 76 | 53.1 | ||||

| Intervention condition | ||||||

| Intervention group (mother only) | 39 | 27.3 | ||||

| Intervention group (father only) | 30 | 21.0 | ||||

| Intervention group (both parents) | 34 | 23.8 | ||||

| Control group | 40 | 28.0 | ||||

Note: Percentages for certain variables may not add up to 100 due to decimal rounding.

All categories, except for Hispanic/Latinx, were non-Hispanic parents.

Sample sizes do not add up to 143 because 27 families did not report household income, and percentages were calculated using n = 116.

Sample sizes do not add up to 143 because 2 children had missing data on language exposure, and percentages were calculated using n = 141.

2.2 |. Procedure

During the home visits at 9 months, mothers and fathers were each recorded in four types of semi-structured interactions with their child (i.e., SBR, free play without toys, free play with toys and cleanup). For this study, we used the SBR interactions, which lasted up to 10 min (i.e., parents were free to read for however long they wanted and the researcher stopped them when they reached 10 min). The books for the SBR interactions (i.e., Un Elefante: Numbers—Numeros and Counting with—Contando con Frida) were selected because they are bilingual in English and Spanish, and age-appropriate for infants. Both books were about counting and contained simple text on each page, including a number word and a label for the object displayed (e.g., ‘two elephants’ and ‘dos elefantes’). Each infant read one book with their mother and another book with their father, and the same two books were read in each family. In addition, we counterbalanced the book mother read and father read between families to ensure that average differences between mothers’ and fathers’ SBR quality would not be attributed to different books. The order of the observations of mother–child and father-child interactions was randomly assigned. Parents were asked to sit on a mat with their infant and act naturally as if we were not present. They were encouraged to read the book in the language they felt comfortable with and were allowed to switch between languages. Two English-Spanish bilingual or two English monolingual trained researchers, depending on the family, conducted the home visit and interviewed parents about family demographics and engagement in literacy activities with their infant at home. While one researcher interviewed the mother or father, another researcher recorded the other parent interacting with their infant. During the 9- and 18-month home visits, a trained researcher (English-Spanish bilingual researchers for infants in Spanish-speaking families) assessed infants’ language skills after their interactions with mother and father.

2.3 |. Measures

2.3.1 |. Infants’ language skills at 18 months

Infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months were assessed by trained researchers using the Preschool Language Scale, 4th edition (PLS-4; Zimmerman et al., 2002). PLS-4 has been validated in a nationally representative sample that was stratified based on parent education, geographic region, and race described by the 2000 Census in the U.S. (Zimmerman et al., 2002). The PLS-4 provides age-appropriate standardised scores for children’s receptive and expressive language skills rather than just vocabulary, and is less susceptible to bias compared to language measures based on parent reports. PLS-4 has strong psychometric properties including test–retest stability coefficients from 0.82 to 0.95 for receptive and expressive scores and internal consistency reliability coefficients from 0.66 to 0.96 in the standardisation sample (Zimmerman et al., 2002).

PLS-4 was administered during home visits in either English or Spanish after consulting with parents about their infant’s preferred language use. Specifically, for infants whose parents reported them to understand/speak only English or Spanish, the assessment was conducted in that language. For infants whose parents reported them to understand/speak both English and Spanish, parents determined which language was more appropriate to use for the assessment; in addition, for these infants who understood/spoke both languages, we administered the items they did not answer correctly in the other language to capture their conceptual knowledge regardless of language. Eight infants were administered items in the other language, but none answered those items correctly in the other language. Of the 143 infants in our sample, 58% (n = 83) were assessed entirely or primarily using the English PLS-4 and 42% (n = 60) entirely or primarily using the Spanish PLS-4. The English and Spanish versions of the assessment are designed to be functionally equivalent and the items under age 3 years are mostly identical in both versions. Independent samples t-tests revealed no significant differences between English and Spanish standardised receptive and expressive language scores (t = −0.55, p = 0.58; t = −0.69, p = 0.49, respectively), and thus, standardised PLS-4 scores were used in the analysis.

2.3.2 |. Parents’ frequency of SBR at 9 months

At 9 months, mothers and fathers reported how frequently they read to their infant at home using one item (i.e., ‘About how often do you read to your child at home’?; Farver et al., 2006). This item was rated on a 7-point scale from 1 = never to 7 = daily (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of mothers’ and fathers’ SBR frequency at 9 months. SBR, shared book reading.

2.3.3 |. Parents’ quality of SBR at 9 months

Mothers’ and fathers’ quality of SBR was assessed as the number of reading strategies they used during SBR with their infants. On average, mothers read for 3.79 min (range = 0.48–10, SD = 2.06) and fathers read for 3.58 min (range = 0.68–9.78, SD = 1.97). Because parents in our sample read with their infants for different amounts of time ranging from half a minute to 10 min, the number of strategies used during SBR was divided by the duration of SBR to ensure that the data were not skewed by the length of time each parent read to their infant. Therefore, SBR quality represented mothers’ and fathers’ number of strategies used per minute during the interaction.

Native English and Spanish speakers transcribed the recorded parent–child SBR interactions in Datavyu (Gilmore et al., 2016) using the standardised format dictated by Codes for the Analysis of Human Language (CHAT), which is available through the Child Language Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney, 2000). Transcription was conducted at the utterance level (i.e., conversational unit), defined by a pause of 1 s or more, ended with a terminal intonation contour, or had a complete grammatical structure (Ratner & Brundage, 2020). Transcribers were required to achieve 90% agreement with the lead transcriber on timing, content, and segmentation of utterances during the training process. Each transcript was checked by a second transcriber to ensure accuracy (Luo & Tamis-LeMonda, 2017; Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019).

The coding scheme of SBR quality was adapted based on previous studies that have measured the reading quality as number of strategies used by parents during SBR with young children (e.g., Deckner et al., 2006; Fletcher et al., 2008; Hindman et al., 2008; Malin et al., 2014; Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). Parents’ utterances were coded for six reading strategies: labelling (e.g., That’s a dress.), description (e.g., She has flowers on her head.), making personal connections to the child (e.g., You wore that dress before.), elaboration (e.g., Those elephants work for the circus), prompts (e.g., wh-questions and other prompts for the child to produce language, such as ‘Can you say “two”?’) and book concepts (e.g., ‘This is the cover of the book’; ‘Turn the page’; see Table II). Reading strategies were coded mutually exclusively, that is, each utterance was only coded for one strategy. Directive utterances used to regulate infants’ attention and behaviours during SBR (e.g., ‘Sit down’. ‘Look here’.) and verbatim utterances based on the text were not coded as reading strategies. To establish interrater reliability for the coding, native English- and Spanish-speaking coders achieved 90% agreement with the lead coder on each reading strategy during the training process; then, 20% of the videos were randomly selected for double coding (Malin et al., 2014; Schick et al., 2017; Seven et al., 2020; Tompkins et al., 2017). According to the guidelines for intraclass correlations (ICCs; Koo & Li, 2016), prompts (ICC = 0.94) and labelling (ICC = 0.93) showed excellent reliability; book concepts (ICC = 0.87) and description (ICC = 0.82) showed good reliability; and connection (ICC = 0.73) and elaboration (ICC = 0.69) showed moderate reliability.

TABLE II.

Descriptive statistics of study variables.

| Mothers (n = 143) |

Fathers (n = 143) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Definition/Scale | Example | M/n (SD) | Range/% | M/n (SD) | Range/% |

| Labelling | Number of utterances that were labelling an object or defining vocabulary | ‘That’s the parrot’. ‘Clouds are things you see in the sky’. | 1.81 (1.98) | 0–8.78 | 1.53 (1.74) | 0–8.47 |

| Description | Number of utterances that were describing a location, action, or attribute | ‘She has flowers in her hair’. | 0.86 (1.19) | 0–5.87 | 0.82 (1.13) | 0–5.16 |

| Book concepts | Number of utterances that were about book handling or reading processes | ‘You turn the page’. | 0.89 (1.12) | 0–6.0 | 0.82 (1.21) | 0–7.5 |

| Prompts | Number of utterances that were wh-questions or other prompts | ‘What’s that?’; ‘Can you say “baby”?’ | 0.55 (0.71) | 0–4.15 | 0.55 (0.88) | 0–4.97 |

| Connection | Number of utterances that were linking book content to child | ‘You wore a dress like that’. | 0.33 (0.76) | 0–7.26 | 0.43 (0.93) | 0–7.45 |

| Elaboration | Number of utterances that were expanding from text to create a story or make inferences | ‘They work for Cirque du Soleil’. | 0.09 (0.27) | 0–1.56 | 0.15 (0.44) | 0–2.68 |

| SBR quality | Summed number of labelling, description, elaboration, connection and prompts utterances | 4.54 (3.60) | 0–15.65 | 4.31 (3.66) | 0–14.51 | |

| Infant attention | Duration of infants’ attention during SBR rated on a 1–5 scale | 3.92 (0.84) | 1.6–5 | 4.05 (0.73) | 2.0–5 | |

| SBR frequencya | Parents reported how often they read to their infants at home | 5.44b (1.62) | 1–7 | 4.85 (1.75) | 1–7 | |

| Parent quantity of speech | Number of words (word tokens) spoken per minute during SBR | 57.83c (19.29) | 8.77–101.47 | 57.70 (24.23) | 9.32–153.88 | |

| Infants (n = 143) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | ||

| Total language at 9Md | Standardised PLS-4 total scores | 95.30 (9.67) | 66–119 |

| Receptive language at 18Me | Standardised PLS-4 receptive scores | 86.76 (12.16) | 67–129 |

| Expressive language at 18Mf | Standardised PLS-4 expressive scores | 97.67 (9.70) | 73–131 |

Note: Means for reading strategies represent the number of times per minute parents used each strategy during shared book reading (SBR).

Sample size for mothers’ and fathers’ reading frequency is 140 due to missing data.

Mothers’ and fathers’ reading frequency are significantly different (t = 4.37, p < 0.0001).

Sample size for mothers’ quantity of speech 142 due to missing data.

Normative mean for standardised PLS-4 scores is 100 and standard deviation is 15 (Zimmerman et al., 2009).

Sample size for receptive language scores at 18 months is 137 due to missing data.

Sample size for expressive language scores at 18 months is 142 due to missing data.

The number of times each strategy was used per minute was then summed across the six strategies to calculate mothers’ and fathers’ SBR quality. It should be noted that SBR quality represented the total number of reading strategies rather than the diversity of strategies (number of different strategies). For example, a parent who used three different types of strategies each for one time, and a parent who used the same strategy three times would have the same score for SBR quality. Studies using composites of the total number of reading strategies, regardless of type, have found them to be positively related to children’s language skills (e.g., Malin et al., 2014; Tompkins et al., 2017; Zucker et al., 2013). The internal consistency among these strategies using standardised Cronbach’s alpha were α = 0.76 for mothers and α = 0.74 for fathers, suggesting acceptable internal consistency.

2.3.4 |. Infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months

Infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months with mothers and fathers was also coded from the recorded SBR interaction. This coding was adapted from three studies that examined infants’ and/or toddlers’ attention during SBR as an indicator of their interest in the activity (Deckner et al., 2006; Malin et al., 2014; Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). It assessed the duration of infants’ attention to the book (e.g., looking at the pages, touching and/or flipping the pages), and was rated on a 5-point Likert scale based on 30-s intervals from 1 = not attending to the book for the entire interval to 5 = attending to the book for the entire interval. The ratings across the intervals were then averaged to obtain one rating per SBR interaction. Trained coders completed batches of five videos until achieving within one-score difference with the lead coder on every video, and 20% of the videos were randomly selected for double coding. Coders achieved moderate interrater reliability (ICC = 0.71).

2.3.5 |. Covariates

To isolate the associations between parents’ frequency and quality of SBR and infants’ language skills, we included seven covariates. At the family level, we controlled for intervention condition (0 = control group and 1 = intervention group), because parents in the intervention group were given books about positive parenting (e.g., reading to children) and child development after the 9-month data collection, which may affect infants’ language outcomes at 18 months. We controlled for study site (1 = D.C. metro area and 2 = southern California), because infants at one site lived with more economically advantaged families than infants at the other site, and these factors have been associated with better language skills (Cabrera & Reich, 2017; Huttenlocher et al., 2010). We also controlled for highest parent education and parent quantity of speech because these variables have been associated with children’s language skills (Rowe, 2008, 2012). The highest level of education between mother and father (1 = less than high school; 2 = high school; 3 = some college; 4 = 4-year college degree or higher) were self-reported. Parents’ quantity of speech (i.e., word tokens) were calculated based on transcripts of their speech during SBR and then summed between mother and father to represent each infant’s total amount of language input from both parents at home.

At the child level, we controlled for infants’ language exposure (0 = English or Spanish only and 1 = two or more languages) and gender (0 = boy and 1 = girl) because studies have shown associations between these variables and children’s language skills (Umek et al., 2008). We also controlled for infants’ standardised total language scores at 9 months measured using the PLS-4 (Zimmerman et al., 2002).

2.4 |. Data analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics and zero-order bivariate correlations for the study variables. Next, we conducted a path analysis to test the associations among mothers’ and fathers’ SBR frequency and quality at 9 months, infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months, and infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months. A path analysis model is the most suitable statistical method for answering our research questions because it tests both direct and indirect paths among the variables; accommodates dependency between variables (e.g., mothers’ and fathers’ variables); and examines the effect of one parent’s SBR frequency and quality on infants’ language skills while accounting for the effect of the other parent.

The model included maternal and paternal SBR frequency and quality at 9 months as exogeneous variables, infants’ attention during SBR with mother and father as mediators, infants’ receptive and expressive language scores at 18 months as endogenous variables, and the covariates. We allowed the error terms of maternal and paternal variables and of receptive and expressive language scores to covary with each other. We also allowed the error terms of the covariates (except for intervention condition) and of exogeneous variables to covary with each other. In addition, the error terms of the covariates covaried among themselves when conceptually relevant. We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to adjust for missing data and maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimation to account for non-normality in the data. To estimate the indirect effects (mediations) through infants’ attention, we utilised bootstrapping based on 1000 bootstrapped samples, and presented the 95% confidence intervals to determine the statistical significance of indirect effects.

We used R (R Core Team, 2020) and the following packages: irr (Gamer et al., 2019), lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), psych (Revelle, 2020) and tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019). Four fit statistics were used in the path analysis: chi-square test, comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). Model fit was evaluated according to Hu and Bentler’s (1999) guidelines, which recommend a CFI >0.95, a RMSEA <0.06, and a SRMR <0.08 for good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We used standardised coefficients (i.e., Betas) to indicate effect sizes for the endogenous variables in the path analysis. Acock (2014) suggested that β <0.2 is considered weak, 0.2< β <0.5 is moderate, and β >0.5 is strong. We also calculated R2 for each model to indicate the proportion of variance in infants’ receptive and expressive language skills explained by the specified path analysis model.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive statistics

None of the primary study variables (i.e., maternal and paternal SBR frequency and quality at 9 months, infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months, and infants’ language skills at 18 months) showed skewness beyond acceptable levels (i.e., smaller than −2 or >2; Curran et al., 1996; Kim, 2013). Figure 1 shows that the majority of mothers and fathers (80% and 69%, respectively) reported reading to their infants at least once a week; almost a third (29%) of mothers and 16% of fathers reported reading to their infants daily; and, only 9% and 14%, respectively, of mothers and fathers reported rarely or never reading to their infants. Table II shows that, on average, mothers reported reading to their infants once a week at 9 months, and fathers reported twice a month.

Regarding the quality of SBR, Table II shows that there is a large variability in the number of reading strategies parents used during SBR, from zero to more than 15 strategies per minute. On average, mothers used 4.54 reading strategies per minute, and similarly, fathers used 4.31 reading strategies per minute. The most and least commonly used strategies across parents were labelling and elaboration, respectively, with mothers and fathers using about 2 labelling strategies per minute (M = 1.81 and 1.53, respectively), and using almost no elaboration strategies per minute (M = 0.09 and 0.15, respectively).

At 9 months, infants paid attention to the book more than half of the time during the SBR interaction with mothers and fathers (M = 4 on a 1–5 scale). In terms of language skills at 18 months, on average, infants scored approximately 1 SD below the norm (normative mean = 100, SD = 15) in receptive skills (M = 86.78, SD = 12.12) and almost at the norm for expressive skills (M = 97.34, SD = 10.26). However, there was large variability. For receptive skills, the majority of the infants (59%) scored at the norm, 40% scored 1 SD below the norm, and 1% scored 1 SD above the norm. For expressive language, the majority of the infants (87%) scored at the norm, only 10% scored 1 SD below the norm, and 3% scored 1SD above the norm (Zimmerman et al., 2009).

3.2 |. Zero-order bivariate correlations

Table III demonstrates that maternal SBR frequency at 9 months was significantly correlated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months (r = 0.24, p < 0.01 for both skills) and that maternal SBR quality was significantly correlated with expressive language skills (r = 0.25, p < 0.01). Moreover, the frequency and quality of maternal SBR were significantly correlated (r = 0.17, p < 0.05). This was not the case for fathers, as neither paternal SBR frequency nor quality was significantly correlated with infants’ language skills. Infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months was not significantly correlated with their language skills at 18 months nor with parents’ frequency and quality of SBR at 9 months.

TABLE III.

Bivariate correlations among shared book reading (SBR), covariate and language variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M SBR frequency | - | |||||||||

| 2. F SBR frequency | 0.47*** | - | ||||||||

| 3. M SBR quality | 0.17* | 0.03 | - | |||||||

| 4. F SBR quality | 0.26** | 0.03 | 0.20* | - | ||||||

| 5. Parent word tokens | 0.30*** | 0.07 | 0.54*** | 0.60*** | - | |||||

| 6. Attention w/M | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.02 | - | ||||

| 7. Attention w/F | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.09 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.21** | - | |||

| 8. Total language (9M) | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.21* | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.08 | - | ||

| 9. Parent education | 0.09 | 0.15 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.08 | - | |

| 10. AC scores (18M) | 0.24** | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.20* | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | - |

| 11. EC scores (18M) | 0.24** | 0.04 | 0.25** | 0.16 | 0.30*** | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.43*** |

Note: M, mother; F, father. Attention = infant attention during SBR. Total language = standardised total language scores at 9 months. AC scores = standardised receptive language scores at 18 months. EC scores = standardised expressive language scores at 18 months.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

3.3 |. Path analysis

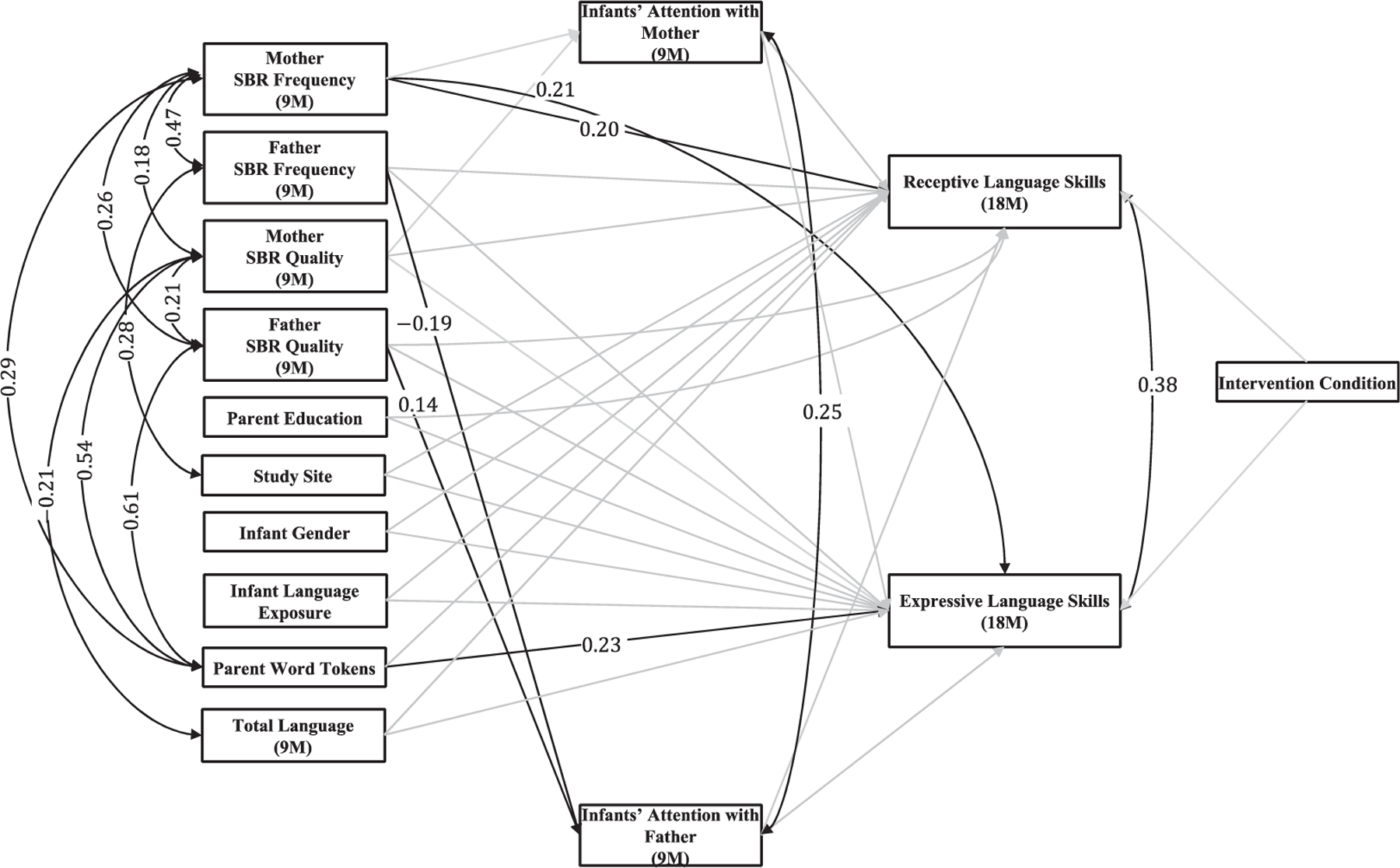

The path analysis model (Figure 2) testing the main effects of the frequency and quality of SBR on language skills and the mediation effects through infants’ attention demonstrated acceptable fit: χ2(df = 32) = 42.40, p = 0.10, suggesting that the predicted model matched the observed data; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.05. This model explained 10% of the variance in receptive language scores, and 18% of the variance in expressive language scores at 18 months.

FIGURE 2.

Path analysis model of main and mediation effects. 9M, months; 18M, 18 months. Significant paths are shown in black with standardised coefficients. Only significant covariances are shown for visual clarity. SBR, shared book reading.

3.3.1 |. Main effects

Controlling for intervention condition, study site, child gender, child language exposure, child language skills at 9 months, parents’ education and parents’ quantity of speech, mothers’ frequency of SBR at 9 months was significantly associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language scores at 18 months (β = 0.20, p = 0.02 and β = 0.22, p = 0.002, respectively), demonstrating moderate effects (i.e., 0.2 < β < 0.5; Acock, 2014). Neither fathers’ frequency nor quality of SBR at 9 months were significantly associated with infants’ language scores at 18 months, over and above the contribution of maternal SBR and the covariates (see Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Summary of path analysis model predicting standardised receptive and expressive language outcomes at 18 months.

|

Variable |

Infant attention w/M |

Infant attention w/F |

Receptive scores |

Expressive scores |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| M SBR frequency | −0.15 | 0.05 | - | - | 0.20* | 0.66 | 0.21** | 0.45 |

| F SBR frequency | - | - | −0.19* | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.72 | −0.09 | 0.52 |

| M SBR quality | 0.12 | 0.02 | - | - | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.32 |

| F SBR quality | - | - | 0.14* | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.34 | −0.03 | 0.29 |

| Infant attention w/ M | - | - | - | - | −0.02 | 1.30 | 0.11 | 0.96 |

| Infant attention w/ F | - | - | - | - | −0.03 | 1.61 | −0.06 | 1.16 |

| Intervention condition | - | - | - | - | −0.01 | 1.01 | 0.08 | 0.71 |

| Study site | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 2.14 | 0.01 | 1.58 |

| Infant gender | - | - | - | - | 0.04 | 1.96 | 0.10 | 1.58 |

| Infant language exposure | - | - | - | - | −0.12 | 2.15 | −0.01 | 1.73 |

| Parent education | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 1.05 | −0.02 | 0.84 |

| Parent word tokens | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| Total language (9 M) | - | - | - | - | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.08 |

| Beta | 95% CI | Beta | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation effects | ||||

| M SBR quality → Infant attention w/M | −0.00 | −0.16–0.07 | 0.01 | −0.01–0.17 |

| F SBR quality → Infant attention w/F | −0.00 | −0.15–0.09 | −0.01 | −0.15–0.02 |

| M SBR frequency → Infant attention w/M | 0.00 | −0.18–0.39 | 0.01 | −0.43–0.04 |

| F SBR frequency → Infant attention w/F | −0.02 | 0–0.22–0.39 | 0.01 | −0.08–0.37 |

Note: M, mother; F, father; CI, confidence interval. Parent word tokens are marginally significant for predicting expressive language skills ( p = 0.07).

Abbreviation: SBR, shared book reading.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

3.3.2 |. Mediation effects

Infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months did not significantly mediate the association between maternal or paternal SBR frequency and quality, and language skills at 18 months (see Table 4). Standardised indirect effects were around 0% and 95% confidence intervals all included 0. However, not as part of our hypotheses, paternal SBR frequency and quality were significantly associated with infants’ attention (β = −0.19, p = 0.01; β = 0.14, p = 0.04, respectively).

3.3.3 |. Sensitivity and exploratory analyses

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the findings based on our primary analysis. Because PLS-4 English and Spanish scores are standardised based on two samples of children (i.e., children who could speak and understand English and children who could understand and converse fluently in Spanish, respectively), we conducted the same path analysis using raw PLS scores, instead of standardised PLS score, to assess whether the findings were influenced by standardisation. Raw scores were appropriate to use also because all the infants in our sample were 18 months when PLS-4 was administered. We found the same results, except that maternal SBR frequency at 9 months was not significantly associated with raw receptive language scores (Table S1).

In addition, we conducted post-hoc analyses to assess the associations between specific strategies at 9 months and infants’ language skills at 18 months. The path analyses show that specific strategies (e.g., labelling, prompts) did not uniquely and significantly contribute to language outcomes (see Tables S2 and S3 for full results).

4 |. DISCUSSION

To advance our understanding of how the reading experiences of infants from ethnically and socioeconomically diverse families relate to their language skills in toddlerhood, we examined associations between mothers’ and fathers’ frequency (i.e., how often they read to their infants), and quality (i.e., number of reading strategies) of SBR with their 9-month-old infants and infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months, and whether infants’ attention during SBR mediated these associations. Overall, mothers and fathers in our sample reported reading to their infants between twice a month and once a week at 9 months and used between 0 and 15 strategies, with an average of five strategies per minute of SBR. The most commonly used reading strategy was labelling (e.g., ‘That’s parrot’.). Controlling for intervention condition, study site, child gender, language exposure, baseline language skills, and parents’ education and quantity of speech, only mothers’ SBR frequency at 9 months was significantly associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months, albeit small effect sizes. We found no evidence that the path between SBR frequency and quality and language skills was mediated through infants’ attention.

4.1 |. Early reading experiences of infants

It is worth noting that infants’ language skills at 18 months in our study varied tremendously from 2 SD below to 2 SD above the norm. Such variability is remarkable and begs the question why some children growing up in less advantaged conditions score at normative levels in language skills as their more advantaged peers (Hoff, 2006; Huttenlocher et al., 2010). The answer might lie, partly, in the variability of exposure to literacy experiences, specifically the quantity and quality of the reading experiences children have at home. In our study, the majority of mothers and fathers (81% and 69%, respectively) reported reading at least once per week to their infants at 9 months and approximately 30% of the mothers and 16% fathers reported reading every day to their infants. Only a small proportion of parents reported not reading at all or rarely reading. These reading patterns are consistent with findings from national studies showing that, on average, 9-month-olds are read to relatively infrequently (once per week; Cabrera et al., 2021; Rathbun & Grady, 2021). These findings suggest that infrequent reading to infants may be an issue that needs to be addressed for all parents from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds.

In terms of the quality of SBR (assessed in our study as the number of reading strategies parents used during SBR with their infants), we also found remarkable variability—some parents did not use any strategies at all and others used more than 15 strategies per minute (an average of 5 strategies per minute). Reading strategies found to be associated with better language outcomes in older children, such as elaboration, making connections with the child, and asking questions, were hardly used by parents in our sample. The most commonly used strategy was ‘labelling’, which offers short, repetitive and concrete language input, followed by ‘introducing basic print concepts’ (e.g., asking the infant to turn the page). From a developmental perspective, such choice of reading strategies might be driven by the age of the child. For example, parents may perceive their preverbal infants to be too young to understand elaboration (e.g., seeing a juggling elephant and ‘elaborating’ that it works in a circus), suggesting that they may be sensitive to the linguistic and cognitive capabilities of their children (Rowe & Snow, 2020). This is consistent with prior findings that White mothers of diverse SES were less likely to elaborate on the text or ask questions during SBR with 10-month-old infants compared to labelling and describing the pictures (Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). Therefore, the ethnically diverse, but predominately Latino, parents in our sample displayed reading behaviours that are similar to those of White mothers. Furthermore, parents’ high use of labelling and low use of elaboration may also be a result of the content in the book, which includes a number and a short phrase without a storyline on each page. The relation between book type and SBR quality has been examined in previous studies (Anderson et al., 2004; Fletcher & Finch, 2015; Luo et al., 2020; Stadler & McEvoy, 2003). Our findings on SBR quality imply that programmes and practitioners should not assume that low-income parents are not engaging in developmentally appropriate behaviours but should rather survey and observe parents first to understand how they are interacting with their infants and then either validate their behaviours or offer guidance on engaging in high-quality SBR with their infants.

4.2 |. SBR frequency, quality and infants’ language skills

Consistent with previous studies, we found support for our hypothesis that the frequency with which mothers report engaging in SBR with their infants is significantly associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months (Duursma, 2014; Fletcher et al., 2008; Jimenez et al., 2020; Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005; Mol et al., 2008; Sénéchal et al., 1998; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002, 2014).

Our finding that the frequency of fathers’ SBR was not significantly associated with infants’ language skill was contrary to our hypothesis and inconsistent with past studies with older children, which found that fathers’ SBR frequency significantly contributes to children’s language skills (e.g., Duursma et al., 2008; Malin et al., 2014). One possible explanation is that fathers in our sample did not read often enough to make a difference (i.e., on average, they reported reading twice a month). Indeed, a paired samples t test showed that fathers, on average, reported reading significantly less often than mothers (t = 4.37, p < 0.0001). This is consistent with past studies demonstrating that fathers reported reading significantly less often to their infants than mothers (Baker, 2018; Cutler & Palkovitz, 2020; Foster et al., 2016). These findings suggest that programmes should target fathers to educate them on the importance of reading to infants during the first year.

We did not find support for our hypothesis that the quality of mothers’ and fathers’ SBR would be associated with infants’ receptive and expressive language skills. Our findings are inconsistent with past findings with older children demonstrating positive associations between SBR quality and language outcomes (e.g., Malin et al., 2014; Mol et al., 2008; Noble et al., 2019; Wasik et al., 2016). Our findings are also inconsistent with the one study with 10-month-old infants, which showed that mothers’ use of questions during SBR at 10 months predicted infants’ receptive and expressive language skills at 18 months (Muhinyi & Rowe, 2019). However, these authors did not control for fathers’ reading behaviours, quantity of language input, demographic characteristic, or mothers’ frequency of SBR, and thus, it is possible that their findings overestimated the effect of maternal SBR quality. In our study, we examined both frequency and quality of SBR by both parents, thereby accounting for more influences on infants’ language skills, and potentially yielding a more conservative estimation of the effects of SBR quality on infants’ language skills. Future studies should include both parents to have a more accurate understanding of how the home literacy environment contributes to language learning.

Although we did not find significant associations between SBR quality and language skills with infants, this does not necessarily mean that parents should be discouraged from using high-quality SBR. Not only does high-quality reading in infancy establish reading habits and interests that can be beneficial for language learning later when infants are more cognitively and linguistically ready to learn from their reading interactions with parents, but it might also ‘prime’ children to benefit more from reading experiences so that the effect might be detected later in development (Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2005).

4.3 |. Infants’ attention as a mechanism

We did not find support for our hypothesis that infants’ attention during SBR at 9 months mediates the associations between mothers’ and fathers’ frequency and quality of SBR and infants’ language skills. The infants in our study on average paid attention to the book for the majority of the time (an average of 4 on a 1–5 scale), and thus, there may not have been enough variability in the sample to observe a significant association between infants’ attention and language outcomes. Moreover, we did not measure joint attention between parents and infants during SBR, which has been found to be related to vocabulary skills over and above the effect of sustained attention (Akhtar & Gernsbacher, 2007; Yu et al., 2019). It is also possible that the effect of SBR during infancy on early language skills may operate through another mechanism that was not tested in this study, or may be more direct than indirect. As reviewed above, we know of only one study that found evidence that toddlers’ attention during SBR mediated the association between reading quality and language skills (Malin et al., 2014). However, that study did not include infants and measured children’s affect and active participation during SBR in addition to attention. It is possible that the mechanism to explain why reading matters during infancy is different from toddlers. Therefore, more research is needed to examine what mechanisms underlie the association between SBR and early language development, and at what point in development.

Although infants’ attention did not significantly mediate the associations between fathers’ SBR frequency and quality and language outcomes, as we hypothesised, it is interesting to note that paternal higher frequency of reading was negatively associated with infants’ attention, whereas, paternal higher quality of reading was positively associated with infants’ attention. Because these are concurrent associations, it is difficult to discern the directionality. It is possible that infants who are less attentive are read to more often by fathers to expose them more to books, and that infants who are more attentive prompt their fathers to use more strategies for engaging them during SBR. The role of the child in how they are read to is an important area of future research.

4.4 |. Limitations and future directions

There are a few limitations that should be considered when interpreting findings from this study. First, we used non-narrative number books for the parent–child SBR activity. Although these books contained a variety of pictures and minimal text that allow for high-quality SBR, these types of books may prompt certain reading strategies (e.g., labelling and describing) more than others (e.g., elaboration), as indicated by prior research on the relation between book type and parents’ reading strategies (Anderson et al., 2004; Fletcher & Finch, 2015; Luo et al., 2020; Stadler & McEvoy, 2003). Different book types may also elicit more or less attention from infants (Fletcher & Finch, 2015). In the future, researchers should try other types of books, such as a wordless picture book or a narrative book to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of parents’ reading strategies and infants’ attention during SBR. Second, we did not measure the overall quality of the SBR interaction (e.g., mothers’ and fathers’ responsiveness, positive affect, etc.), which may contribute to language development as found in previous studies (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2017; Landry et al., 2008; Ryan et al., 2006; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004, 2019). Future studies should evaluate the overall quality of the parent–child SBR interaction in addition to the reading strategies to obtain a more comprehensive picture of infants’ reading experiences. Third, SBR activity was recorded while researchers were present, which may have altered parents’ behaviours during SBR, such as using more strategies to appear more engaged with their infant, (i.e., Hawthorne effect; McCarney et al., 2007) or acting other than they typically would when reading to their infants at home. Fourth, past research has identified cultural variations in SBR related to parents’ race, ethnicity, and language use (Boyce et al., 2004; Caspe, 2009; Hammer et al., 2005; Jimenez et al., 2019; Melzi & Caspe, 2005). Although examining the correlates of parents’ SBR behaviours, such as demographic characteristics and cultural beliefs and practices, is not the goal of our study, it is important for future studies to understand whether these factors shape infants’ reading experiences during the first year and whether they moderate the association between SBR and early language skills (Duursma et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2020). Lastly, this study did not include measures on home literacy resources (e.g., number of books) or parents’ attitudes toward reading with infants, which have been found to relate to parents’ literacy behaviours and children’s language outcomes (Niklas et al., 2020; Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011). Future studies could benefit from measuring the broader home literacy environment of children during the first year.

5 |. CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations, our study adds to the growing literature on the importance of reading to infants in ethnically and socioeconomically diverse families by showing that over and above fathers’ reading behaviours and other important family characteristics, infants who are read to frequently by their mothers during the first year have better receptive and expressive language skills than infants who are read to less frequently by their mothers. This finding underscores that many low-income mothers engage in reading that is frequent enough to make a difference and that we should encourage fathers to do the same with their infants. The role that high-quality SBR during infancy plays in language development needs to be further explored to identify what types of reading strategies are most helpful to infants. An implication of our findings is that programs should focus on encouraging both parents, especially fathers, to read to their infants as often as possible, and to use various reading strategies to increase infants’ attention during the reading activity. Early childhood practitioners (e.g., paediatricians, home visitors) could educate both mothers and fathers on the importance of book reading during infancy, provide parents with infantand child-appropriate books, and model a variety of reading strategies, as a way to support parent-infant SBR and early language development. Understanding how both mothers and fathers contribute to the early language and literacy environment of infants in ethnically and socioeconomically diverse families should enable researchers and policymakers to identify the specific factors and mechanisms that support early language development and, in turn, reduce disparities in school readiness.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by a grant awarded to Dr. Natasha J. Cabrera and Dr. Stephanie M. Reich by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) R01HD078547-05.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study uses data from a larger study (Baby Books 2 Project) approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland-College Park (protocol number 714055).

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peerreview/10.1002/icd.2516.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are not publicly available but can be provided upon reasonable request sent to the authors. No aspect of this study was pre-registered.

REFERENCES

- Acock AC (2014). A gentle introduction to Stata (4th ed.). Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adani S, & Cepanec M (2019). Sex differences in early communication development: Behavioral and neurobiological indicators of more vulnerable communication system development in boys. Croatian Medical Journal, 60(2), 141–149. 10.3325/cmj.2019.60.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar N, & Gernsbacher MA (2007). Joint attention and vocabulary development: A critical look: Joint attention and vocabulary development. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1(3), 195–207. 10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00014.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldoney D, & Cabrera NJ (2016). Raising American citizens: Socialization goals of low‐income immigrant Latino mothers and fathers of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3607–3618. 10.1007/s10826-016-0510-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Anderson A, Lynch J, & Shapiro J (2004). Examining the effects of gender and genre on interactions in shared book reading. Reading Research and Instruction, 43(4), 1–20. doi: 10.1080/1938807040955841420076771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CE (2018). Fathers’ and mothers’ language acculturation and parenting practices: Links to Mexican American children’s academic readiness. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(1), 52–64. 10.1177/1476718X15614044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes E, & Puccioni J (2017). Shared book reading and preschool children’s academic achievement: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study-birth cohort. Infant and Child Development, 26(6), e2035. 10.1002/icd.2035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitetti D, & Hammer CS (2016). The home literacy environment and the English narrative development of Spanish–English bilingual children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(5), 1159–1171. 10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake J, Macdonald S, Bayrami L, Agosta V, & Milian A (2006). Book reading styles in dual-parent and single-mother families. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 501–515. 10.1348/000709905X49719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce LK, Cook GA, Roggman LA, Innocenti MS, Jump VK, & Akers JF (2004). Sharing books and learning language: What do Latina mothers and their young children do? Early Education & Development, 15(4), 371–386. 10.1207/s15566935eed1504_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (Vol. 1, 6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SR, Hecht SA, & Lonigan CJ (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408–426. 10.1598/RRQ.37.4.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, & Reich S (2017). BabyBooks2: A randomized control trial (RCT) to test the effects of a book intervention for low‐income mothers and fathers. In Author (Chair.), International perspectives on parenting interventions for at‐risk families. In Symposium conducted at the biennial meeting of the society for research in child development. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Hennigar A, Chen Y, West J, Fagan J, & Wildsmith E (2021). Programs can build on the strengths of Latino families with low incomes to improve outcomes. Report 2021–02. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/programs-can-build-on-the-strengths-oflatino-families-with-low-incomes-to-improve-outcomes [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Hofferth SL, & Chae S (2011). Patterns and predictors of father-infant engagement across race/ethnic groups. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(3), 365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Karberg E, Malin JL, & Aldoney D (2017). The magic of play: Low-income mothers’ and fathers’ playfulness and children’s emotion regulation and vocabulary skills. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 757–771. 10.1002/imhj.21682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Moon U, Fagan J, West J, & Aldoney D (2020). Cognitive stimulation at home and in child care and children’s preacademic skills in two-parent families. Child Development, 91(5), 1709–1717. 10.1111/cdev.13380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspe M (2009). Low-income Latino mothers’ booksharing styles and children’s emergent literacy development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(3), 306–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cates CB, Weisleder A, Johnson SB, Seery AM, Canfield CF, Huberman H, Dreyer BP, & Mendelsohn AL (2018). Enhancing parent talk, reading, and play in primary care: Sustained impacts of the video interaction project. The Journal of Pediatrics, 199, 49–56. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Early Childhood, High PC, Klass P, Donoghue E, Glassy D, DelConte B, Earls M, Lieser D, McFadden T, Mendelsohn A, Scholer S, Schulte EE, Takagishi J, Vanderbilt D, & Williams PG (2014). Literacy promotion: An essential component of primary care pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 134(2), 404–409. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1, 16–29. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler L, & Palkovitz R (2020). Fathers’ shared book reading experiences: Common behaviors, frequency, predictive factors, and developmental outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 56(2), 144–173. 10.1080/01494929.2019.1683119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidse NJ, de Jong MT, Bus AG, Huijbregts SCJ, & Swaab H (2011). Cognitive and environmental predictors of early literacy skills. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 395–412. 10.1007/s11145-010-9233-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckner DF, Adamson LB, & Bakeman R (2006). Child and maternal contributions to shared reading: Effects on language and literacy development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 31–41. 10.1016/j.appdev.2005.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Simkus A, & Hamby DW (2012). Relationships between age of onset and frequency of reading and infants’ and toddlers’ early language and literacy development. Center for Early Literacy Learning Reviews, 5(3). [Google Scholar]

- Duursma E (2014). The effects of fathers’ and mothers’ reading to their children on language outcomes of children participating in early head start in the United States. Fathering: A Journal of Theory and Research About Men as Parents, 12(3), 283–302. http://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/1346 [Google Scholar]

- Duursma E (2016). Who does the reading, who the talking? Low-income fathers and mothers in the US interacting with their young children around a picture book. First Language, 36(5), 465–484. 10.1177/0142723716648849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duursma E, Pan BA, & Raikes H (2008). Predictors and outcomes of low-income fathers’ reading with their toddlers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(3), 351–365. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Xu Y, Eppe S, & Lonigan CJ (2006). Home environments and young Latino children’s school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(2), 196–212. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Xu Y, Lonigan CJ, & Eppe S (2013). The home literacy environment and Latino head start children’s emergent literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 775–791. 10.1037/a0028766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher KL, Cross JR, Tanney AL, Schneider M, & Finch WH (2008). Predicting language development in children at risk: The effects of quality and frequency of caregiver reading. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 89–111. 10.1080/10409280701839106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher KL, & Finch WH (2015). The role of book familiarity and book type on mothers’ reading strategies and toddlers’ responsiveness. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(1), 73–96. doi: 10.1177/1468798414523026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TD, Froyen LC, Skibbe LE, Bowles RP, & Decker KB (2016). Fathers’ and mothers’ home learning environments and children’s early academic outcomes. Reading and Writing, 29(9), 1845–1863. 10.1007/s11145-016-9655-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer M, Lemon J, & Singh IFP (2019). Irr: Various coefficients of interrater reliability and agreement. R package version 0.84.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=irr [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore RO, Adolph KE, Millman DS, & Gordon A (2016). Transforming education research through open video data sharing. Advances in Engineering Education, 5 http://advances.asee.org/wp-content/uploads/vol05/issue02/Papers/AEE-18-Gilmore.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]