Dear Sirs,

Mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine-kinase-emia (MIMECK) is a mitochondrial disease subtype first reported by Okamoto et al. in 2011 [1]. MIMECK is a rare mitochondrial disease characterized by episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia, proximal muscle weakness, and myalgia clinically. Its acute onset and rapid muscle-symptom progression can mimic viral myositis, drug-induced myopathy (Lamivudine, Zidovudine), and myasthenia gravis, making it a diagnostic challenge.

Previous research into the muscle pathology of MIMECK has revealed mitochondrial abnormalities, including ragged-red fibers (RRF) and cytochrome c oxidase (COX) deficiency. There is a high frequency of familial cases and a unique constellation of 16 mitochondrial DNA single-nucleotide polymorphisms, none of which are individually pathogenic (The identified variants were m.200A > G, m.257A > G, m.1442G > A, m.4612 T > C, m.5127A > G, m.6332A > G, m.7389C > T, m.8281_8289del, m.8291A > G, m.10403A > G, m.11151C > T, m.11969G > A, m.13105A > G, m.16325 T > G, m.16390G > A, and m.16523A > G). This suggests a novel genetic profile [1].

Intravenous administration of arginine during the acute phase has been reported effective, partially reversing symptoms [2]. However, long-term clinical progression and pathological findings outside of muscle tissue remained uninvestigated.

Here, we present the first MIMECK autopsy report (Case 2 in citation [1]). By detailing the clinical course leading to death and the pathological findings, we demonstrate that MIMECK is not limited to myopathy but is a mitochondrial disease involving multiple organ systems.

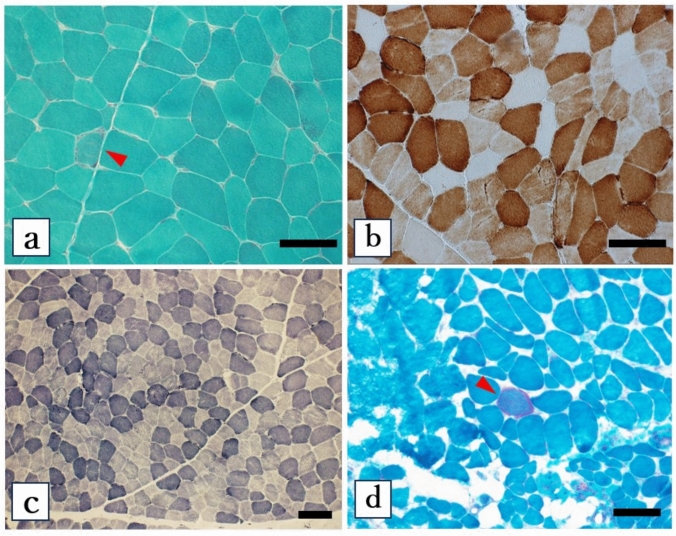

The index patient (Fig. 1: II-4) with positive family history developed exertional myalgia at 40 years old, followed by acute proximal muscle weakness with elevated serum CK (1079 U/L; reference range: up to 210 U/L). Initial evaluation at age 41 revealed short stature (147 cm) and low body weight (38.5 kg; body mass index 17.8). Blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lactate levels and lactate-to-pyruvate ratios were measured to evaluate for mitochondrial dysfunction, but results were within normal limits. Biopsy of the biceps brachii muscle (41-year-old) demonstrated RRF, partial COX deficiency, and NADH staining heterogeneity, leading to a diagnosis of mitochondrial myopathy (Fig. 2a–c).

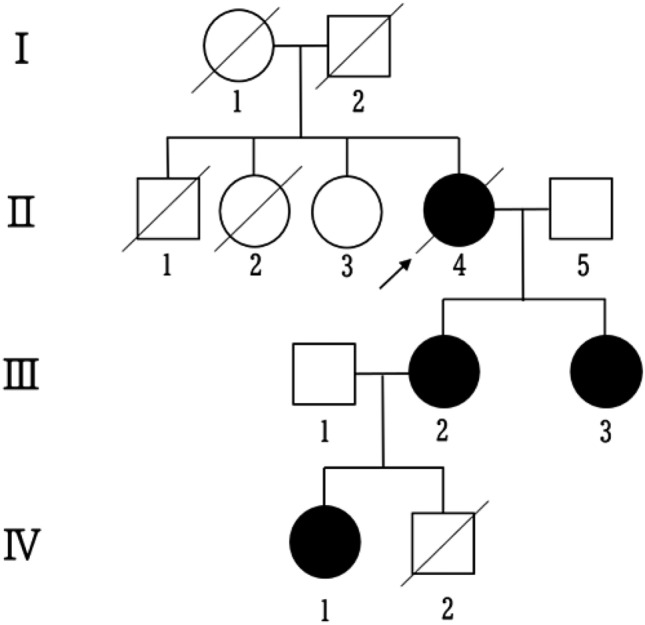

Fig. 1.

Family pedigree showing the proband (II-4, arrow) with mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia (MIMECK). The patient’s mother (I-1) died from cerebral infarction at age 82. Two deceases siblings included II-1 (pneumonia, age 3) and II-2 (combined muscle and cardiac disease, 60 s). Two daughters (III-2 and III-3) exhibited muscle weakness and hyper-CK-emia, with III-3 also having pneumonia in her 40 s. Granddaughter (IV-1) had prenatal cardiomegaly, ventricular enlargement, and ascites, and was later diagnosed with autism, developing vision and hearing impairments, and muscle weakness in her 20 s. Another grandchild (IV-2) died neonatally from cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal complications. Genetic confirmation of MIMECK was established in the proband (II-4), her daughter (III-3), and granddaughter (IV-1)

Fig. 2.

Histopathology of proband’s biceps brachii (biopsy; a-c) and paraspinal muscles (autopsy; d). (a, d) Gomori trichrome stains show ragged-red fibers (arrowheads; 1.21% and 0.78% prevalence, respectively). b Cytochrome c oxidase (COX) staining reveals partial deficiency (11.22% negative fibers). c Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)-tetrazolium reductase staining shows focal enzymatic activity variations. Scale bar = 100 μm

She maintained independent mobility for > 10 years despite progressive fatigue and generalized muscle pain. By her late 50 s, she developed gait instability, followed by frequent urination and pseudo-obstruction. Orthostatic hypotension and depression-like mood disorders were also observed. She required hospitalization at age 63 for dyspnea on minimal exertion and an evident weight loss (10 kg). Despite normal echocardiogram findings, pulmonary function tests showed restrictive ventilatory impairment (forced vital capacity FVC: 49.8% predicted; peripheral oxygen saturation SpO2: 92%). She received intravenous l-arginine (20 g/day × 5 days), with subsequent improvement in respiratory function (FVC: 59.6% predicted, SpO2: 98%). Genetic testing via MitoChip identified 16 homoplasmic mtDNA variants in both blood and skeletal muscle DNA, suggestive the diagnosis of MIMECK. Subsequent whole-exome sequencing revealed no pathogenic variants in nuclear-coding mitochondrial genes.

The patient subsequently experienced recurrent disease exacerbations characterized by systemic pain, generalized weakness, dyspnea, dysphagia, and CK elevation, frequently triggered by infections or sulpiride administration (for depression). At age 66, she manifested mild cognitive decline (Mini-Mental State Examination score: 26/30). Neuroimaging revealed mild white matter changes on MRI (Fig. S1) and a lactate peak near the lenticular nuclei on Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), suggestive of central mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. S2). The disease progressed to hypercapnic respiratory failure (PaCO₂ 79.3 mmHg), culminating in death at age 74 years.

The proband’s mother (Fig. 1: I-1) died of a cerebral infarction at age 82. One brother (II-1) died of pneumonia at age 3, and a sister (II-2) died in her 60 s from a combination of muscle and cardiac disease. Two affected daughters of the proband (III-2 and III-3) exhibited muscle weakness and hyper-CK-emia; III-3 also had a history of pneumonia in her 40 s. A granddaughter (IV-1) presented prenatally with cardiomegaly, ventricular enlargement, and ascites. Postnatally, she was diagnosed with autism, followed by progressive vision and hearing impairments, and muscle weakness emerging in early adulthood. Another grandson (IV-2) died neonatally due to cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal complications.

Muscle autopsies obtained from multiple regions revealed an absence of ragged-red fibers (RRFs) in the quadriceps, biceps femoris, and iliopsoas. However, few RRFs (0.78% of fibers) were identified in paraspinal muscles (Fig. 2d).

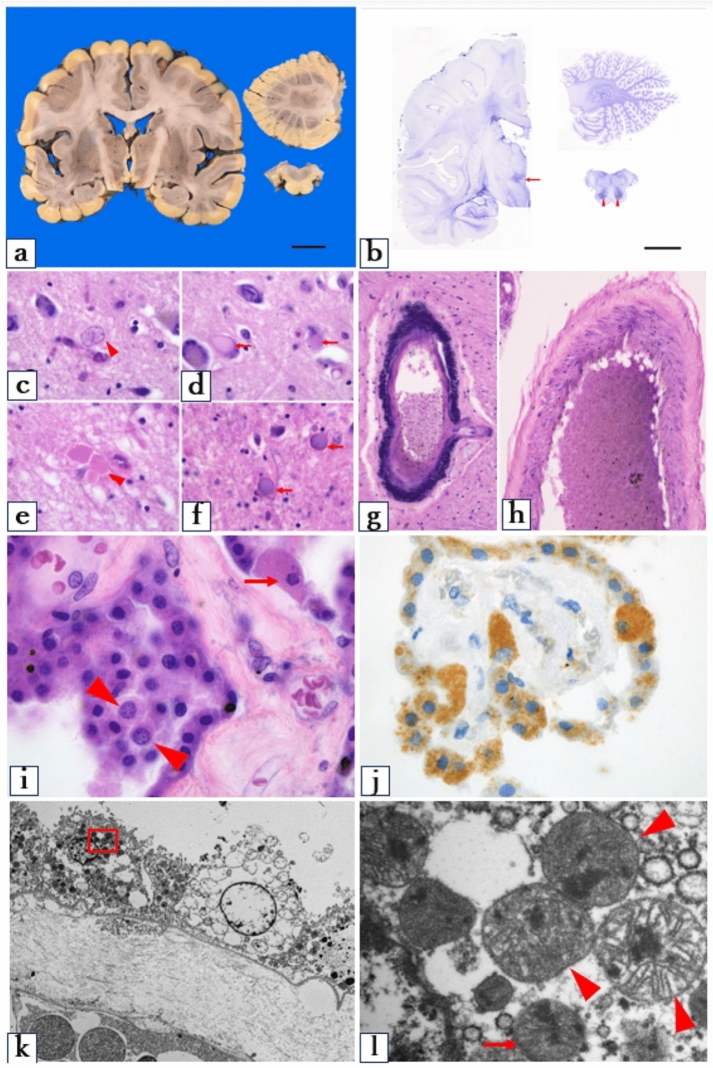

Gross examination of the heart revealed mild left ventricular hypertrophy, with myocardial thickness of 13 mm. Histological evaluation of the atrioventricular conduction system showed fibrosis involving the His bundle, suggesting latent conduction disturbances (Fig. 3a). The presence of myocardial hypertrophy was further supported by myocyte size variation and architectural disarray (Fig. 3b), with a mean myocyte short-axis diameter of 21.8 μm (Fig. 3b). Electron microscopy showed an elevated number and density of mitochondria in the cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3c and d).

Fig. 3.

Heart (a–d) and kidney (e–h) macroscopic and microscopic findings in the proband. a Azan-Mallory staining of a cross-section of the atrioventricular conduction system revealing bifurcation of the His bundle into the right and left legs. The His bundle is infiltrated by fibrous tissue, and irregular fibrosis is within the bundle itself. Abnormal fibrosis can also be seen at the very top of the interventricular septal myocardium. Scale bar: 500 μm. b Hematoxylin & eosin stain revealing variation in the size of the myocardial fibers, with architectural disarray, and mild hypertrophy. Scale bar: 50 μm. c, d Electron microscopy of the heart tissue showing increased mitochondrial density. d is a magnified view of the red box in c. This highlights the flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions within the mitochondrial matrix (arrowheads). Magnification: c ×3000; d ×10,000. e Gross examination of the kidney showing multiple cysts. Scale bar: 2 cm. f Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing preserved architecture with mild tubular changes. Magnification: ×600. g, h Electron microscopy of the kidney showing an increased number of mitochondria and characteristic flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions in the mitochondrial matrix (arrowheads). Magnification: g ×4000; h ×40,000. CFB central fibrous body, His His bundle, VS ventricular septum, MIMECK mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia

The kidneys displayed multiple bilateral cortical cysts (Fig. 3e), with no significant glomerular sclerosis or proliferative changes (Fig. 3f). No granular swollen epithelial cells, which are typically identified by mitochondrial enlargement in tubular cells, were observed. Both the heart and kidneys exhibited flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions in the mitochondria under electron microscopy (Fig. 3c–f).

Congestion and focal hemorrhage were observed in multiple organs but were considered nonspecific and attributed to cardiopulmonary resuscitation rather than as a contributory cause of death.

Macroscopic examination of the brain revealed a weight of 1278 g, which is within the normal range. There was no evidence of cortical atrophy or large structural lesions such as stroke-like abnormalities (Fig. 4a). We saw no cortical laminar necrosis or white matter degeneration. Gliotic scarring was found in the posterior hypothalamic area and inferior olive nuclei (Fig. 4b). Alzheimer type II astrocytes with enlarged nuclei were identified in the posterior hypothalamic area (Fig. 4c). In the same region, we also observed occasional neurons with hyaline inclusions (Fig. 4d) and enlarged axons (Fig. 4e). In the medullary thin bundle and cuneate nucleus, eosinophilic spherical structures with dual staining were noted in H&E stains (Fig. 4f). Calcification was observed in the vascular walls of the globus pallidus and choroid plexus (Fig. 4g). However, there was no thickening of the vascular smooth muscle in the tunica media, as reported in other studies on mitochondrial angiopathy (Fig. 4h).

Fig. 4.

Histological and ultrastructural findings in the brain of the proband. a No overt abnormalities are visible by macroscopic examination. Scale bar: 2 cm. b Holzer stain showing gliotic scarring in the posterior hypothalamic area and the inferior olive nuclei of the medulla. Scale bar: 2 cm. c Hematoxylin & eosin stain showing Alzheimer type II astrocytes (arrowheads) in the posterior hypothalamic area, hyaline inclusions within the neurons (arrows) (d), and enlarged axons (e). f Spherical structures within the thin bundle nucleus. g Mineral deposits in the vascular walls of the globus pallidus. h No thickening of the smooth muscle in the middle layer of the brain surface vessels. i Enlargement of both the nucleus (arrowheads) and cytoplasm (arrow) of epithelial cells in the choroid plexus. j Mitochondrial stain revealing a mosaic pattern: some epithelial cells have intense cytoplasmic staining due to dense mitochondrial accumulation, whereas others have minimal or no staining (anti-human mitochondrial antibodies). k, l Electron microscopy of the choroid plexus showing both normal-sized (arrows) and enlarged (arrowheads) mitochondria, all containing characteristic flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions. c–l Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Magnification: c–e, i, j ×100; f–h ×20; K ×800; l ×10,000. MIMECK mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia

The epithelial cells of the choroid plexus showed balloon-like swelling of both the cytoplasm and nuclei (Fig. 4i–k). Mitochondrial staining showed a heterogeneous pattern, with some cells demonstrating intense cytoplasmic staining suggestive of mitochondrial accumulation, and others not staining at all (Fig. 4j). Electron microscopy revealed that the mitochondria of the choroid plexus epithelial cells varied in size and morphology within individual cells. They also had flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions (Fig. 4k and l).

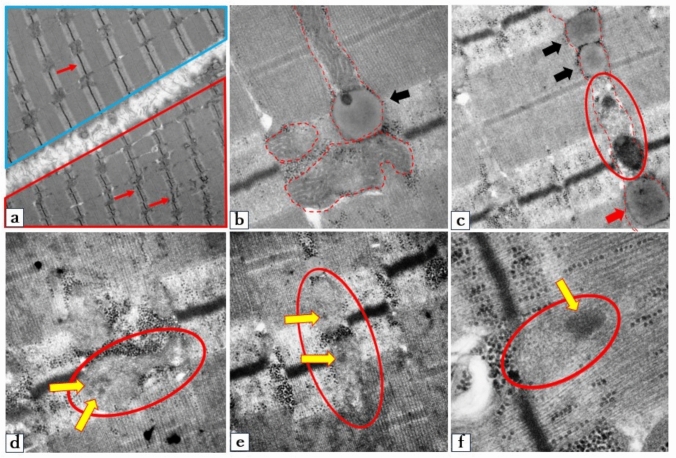

Ultrastructural analysis revealed heterogeneous involvement of muscle fibers, with varying degrees of mitochondrial and myofibrillar damage (Fig. 5a). In severely affected regions, mitochondria showed marked matrix pallor with near-complete loss of cristae and disruption of the bilayer membrane. Adjacent myofibrils exhibited Z-band streaming and disorganization (Fig. 5a—red box). Relatively preserved mitochondria with intact cristae were also observed in contact with lipid droplet-like structures (Fig. 5b). Serial transitions between degenerating mitochondria and lipid droplet-like structures suggested a progressive morphological continuum (Fig. 5c). Notably, a subset of lipid droplets demonstrated increased electron density, containing distinctive flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions. (Fig. 5d–f, yellow arrows).

Fig. 5.

Electron microscopy findings from the biopsied biceps brachii muscle of proband. a Electron microscopy showing both relatively preserved myofibers (blue box) and damaged myofibers (red box). In the affected fibers, the mitochondrial matrix displays reduced electron density, and the typical double membranes and cristae structures are barely visible. The Z-bands appear shortened and disorganized (arrow). b Mitochondria with relatively milder damage exhibit well-preserved cristae (outlined by dotted lines). The mitochondria and lipid droplet-like structures (black arrows) are in contact. c Dotted lines indicate morphological changes in mitochondria. Severely damaged mitochondria (red circles) transform into lipid droplet-like structures (black arrows). Some lipid droplets exhibited increased electron density, with structures reminiscent of flocculent or woolly electron dense inclusions (red arrows). d–f Flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions (yellow arrows) within the damaged mitochondria (red circle). Magnification: a × 8000; b ×50,000; c ×20,000; d ×30,000; e ×30,000; f × 0,000. MIMECK mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia

This study represents the first comprehensive pathological characterization of a patient genetically diagnosed MIMECK case. While previous reports on MIMECK have been limited to muscle biopsy findings, we demonstrate histopathological evidence of multi-organ involvement, a defining feature of mitochondrial diseases. In accordance with recent diagnostic criteria for mitochondrial diseases [3], this phenotype aligns more closely with primary mitochondrial myopathy (PMM), particularly the subtype presenting with episodic rhabdomyolysis. However, MIMECK is distinguished by its unique genetic signature, featuring 16 homoplasmic mtDNA variants in the absence of pathogenic variants in MT-CYB or genes associated with CoQ10 deficiency, which can also manifest with a PMM phenotype [1].

Cardiac involvement in mitochondrial diseases has been well documented. These include conduction defects in KSS and myocardial hypertrophy in MELAS [4]. Similarly, we found prenatal and neonatal cardiac dysfunction in two family members of the patient presented in this study. However, the index patient showed no clinical or laboratory evidence of cardiac abnormalities. Despite this, pathological examination revealed myocardial hypertrophy, an elevated number and density of mitochondria, and flocculent or woolly electron-dense inclusions within the mitochondrial matrix. These findings illustrate the potential for both clinical and subclinical cardiac involvement in patients with MIMECK, highlighting the need for long-term cardiac monitoring. Although hepatic function was preserved, we observed multiple bilateral cortical cysts in the kidneys of the index patient. This is consistent with previously reported cystic changes in mitochondrial disorders [5].

Neuropathological examination revealed gliosis in the posterior hypothalamic region and the inferior olivary nucleus. These findings are in concordance with a previously reported autopsy case involving a mutation in another mitochondria-related gene, C12orf65 [6]. Other findings common in mitochondrial diseases that were also seen in the present case include vascular calcification in the globus pallidus and choroid plexus, and Alzheimer type II astrocytes in the posterior hypothalamus [7, 8]. These suggest metabolic abnormalities- mineral metabolism: calcium and phosphate, oxidative stress [8].

Certain findings in the present case appear to be unique, including neurons with hyaline inclusions, enlarged axons, and spherical structures within the medullary thin bundle and cuneate nucleus. These appear to be novel morphological manifestations of the mitochondrial dysfunction in this disease. Notably, no clinical signs corresponding to dysfunction in these regions, such as thermoregulatory abnormalities, drowsiness, or deep sensory deficits, manifested during the patient’s lifetime. Nonetheless, the patient exhibited depressive symptoms and mild cognitive impairment, symptoms also reported in affected family members.

The choroid plexus plays an important role in the regulation of molecular concentrations in the CSF, protecting neurons and glial cells, and preserving ion homeostasis. Dysfunction of the choroid plexuses can disrupt interstitial ion balance, impair neuronal excitability, and interfere with protein absorption and lactate transport from the CSF [8]. In mitochondrial diseases such as Leber encephalopathy and MELAS, defects have been reported in subunit II of the COX in choroid plexus epithelial cells [8]. Previous studies have described cytoplasmic swelling and a reduced nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio in these cells [9, 10]. In contrast, the choroid plexus epithelial cells in this case showed balloon-like swelling of both the nuclei and cytoplasm. While MELAS and MIMECK share acute disease onset features [2], the distinct nuclear-to-cytoplasmic morphology observed in our case may help to differentiate MIMECK. Electron microscopy revealed mitochondrial heterogeneity within individual epithelial cells, with mitochondria of varying size creating a mosaic-like pattern. This mosaicism could be a characteristic feature of MIMECK.

The consistent observation of lipid droplet-like structures in skeletal muscle biopsies from both the proband and her affected daughter (III-3, Patient 1 in citation [2]), combined with ultrastructural evidence demonstrating progressive mitochondrial degeneration culminating in lipid accumulation, strongly implicates a disease-specific metabolic impairment. These pathological changes likely reflect compromised fatty acid oxidation and disrupted tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle function [11], representing both a characteristic histopathological feature and a potential key mechanistic insight into the underlying metabolic dysfunction. These findings warrant further investigation to elucidate whether these lipid accumulations contribute directly to disease pathogenesis or represent a secondary consequence of mitochondrial failure.

Flocculent or woolly electron-dense mitochondrial inclusions were observed in both autopsy and biopsy-derived skeletal muscle specimens from the subject. These electron-dense structures are not limited to mitochondrial diseases but can also occur under cellular stress, such as ischemia and apoptosis.

Postmortem autolysis and delayed formalin fixation in autopsy tissue often result in artifactual changes, such as clearing of the mitochondrial matrix, disruption of cristae, and nonspecific protein aggregates. As a result, autopsy specimens exhibit increased contrast, while glutaraldehyde-fixed biopsy specimens exhibit reduced contrast and preserved ultrastructure. Despite the contrast difference, the identification of identical inclusions in biopsy specimens confirmed their biological significance. Notably, the biopsy specimen, obtained at age 41 under a strict fixation protocol, effectively eliminates postmortem artifacts and age-related degenerative changes as confounding factors. Therefore, these mitochondrial inclusions likely represent the characteristic ultrastructural features of MIMECK.

Similar electron-dense inclusions have been reported in LHON, particularly in the extraocular muscles [12], optic nerves [13], and skeletal muscles [14]. These inclusions are believed to result from the accumulation of abnormal metabolic intermediates and associated proteins related to dysfunction in the mitochondrial TCA cycle [15].

Given that a skeletal muscle biopsy from MIMECK has reported small-vessel hyalinosis (SVH)—a vascular lesion analogous to that seen in MELAS, which provides a mechanistic rationale for using l-arginine therapy [2]. (Case 2 in citation [1]). While the episodic nature of MIMECK permits within-patient symptom comparisons, the uncontrolled design precludes definitive efficacy conclusions. Future prospective studies incorporating quantitative biomarkers are needed to objectively evaluate l-arginine’s therapeutic potential in MIMECK.

The generalizability of our findings is limited as this report is based on a single autopsy case. Although key pathological features were confirmed using ante-mortem biopsies to reduce postmortem artifact concerns, some may still have been nonspecific, particularly those observed in the heart and kidneys. Furthermore, the exclusive use of fixed tissue samples precluded functional assays, including direct assessments of mitochondrial activity.

Although genotype–phenotype cosegregation was observed in affected individuals (II-4, III-2, and IV-1), the small family size and incomplete genetic data (missing studies for unaffected II-3 and affected III-3) limit definitive penetrance estimates. Notably, the relatively severe phenotypes in IV-1 and IV-2 raise the possibility of genetic anticipation in this pedigree. Future studies should expand pathological examinations to additional MIMECK cases, incorporate fresh tissue analyses, and include comprehensive family studies to clarify genotype–phenotype correlations.

In conclusion, this autopsy case of a genetically confirmed MIMECK patient provides valuable insights into the multisystem pathology of this rare mitochondrial disease. The condition shares several features with other mitochondrial disorders, such as MELAS, KSS, and LHON, including vascular calcification, gliosis, and characteristic mitochondrial ultrastructural changes. These include distinctive alterations in the choroid plexus and the consistent presence of flocculent or woolly electron-dense mitochondrial inclusions in muscle, heart, kidneys, and brain, which could potentially serve as diagnostic markers. Clinically, this case challenges the prior characterization of MIMECK as an episodic disorder (based on acute CK elevations), demonstrating instead a chronic and progressive course. These findings highlight the need for regular systemic evaluation and long-term management, similar to other mitochondrial diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Supplementary Figure 1: Brain FLAIR MRI findings from the index patient with MIMECK at age 66. Only nonspecific white matter lesions are visible. Diffusion-weighted images show no evidence of the stroke-like lesions seen in MELAS. FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MELAS, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MIMECK, mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging (PDF 88 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Figure 2: Brain MRS findings of the index patient with MIMECK at age 66. MRS was performed during a non-seizure session. Although the white matter lesion in the basal ganglia appeared nonspecific on conventional imaging, MRS at the same site revealed a lactate peak. CO2, carbon dioxide; CR, creatine; MIMECK, mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy: NAA, N-acetylaspartate (PDF 59 KB)

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the patients and their relatives for receiving genetic tests and pathological examinations in this study. The authors appreciate T Ohnishi and N Hirata at Kagoshima University for their vital technical assistance. The authors extend their appreciation to the Division of Gene Research, Research Support Centre, Kagoshima University, for the use of their facilities. Finally, the authors thank ENAGO (www.enago.jp) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex

- COX

Cytochrome c oxidase

- CK

Creatine kinase

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- KSS

Kearns-Sayre syndrome

- LHON

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy

- MELAS

Myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like

- MIMECK

Mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- RRF

Ragged-red fibers

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

Author contributions

RN, YHir, YS and HT conceived the project and designed the study. RN and SN collected the clinical data. MA, YHig, and AY analyzed and verified the genetic data. HM, TN, AA, YI and IY contributed to the evaluation and analysis of pathological examination. YO aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. JY contributed to English proofreading. RN drafted the original manuscript, and all co-authors approved the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (Grant Numbers 201442014A and 201442071A). This research was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers JPK20K07906, JP23K06966, JP24K18708).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for ethical and privacy reasons, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kagoshima University (application ID: G490).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and available family members.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of clinical data and images was obtained from the patient’s family.

References

- 1.Okamoto Y, Higuchi I, Sakiyama Y, Tokunaga S, Watanabe O, Arimura K et al (2011) A new mitochondria-related disease showing myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia. Ann Neurol 70:486–492. 10.1002/ana.22498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nozuma S, Okamoto Y, Higuchi I, Yuan J, Hashiguchi A, Sakiyama Y et al (2015) Clinical and electron microscopic findings in two patients with mitochondrial myopathy associated with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia. Intern Med 54:3209–3214. 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.5444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancuso M, Lopriore P, Semmler L, Kornblum C (2025) 280th ENMC International Workshop: The ERN EURO-NMD mitochondrial diseases working group; diagnostic criteria and outcome measures in primary mitochondrial myopathies. Hoofddorp, the Netherlands, 22-24 November 2024. Neuromuscul Disord 50:105340. 10.1016/j.nmd.2025.105340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behjati M, Sabri MR, Etemadi Far M, Nejati M (2021) Cardiac complications in inherited mitochondrial diseases. Heart Fail Rev 26:391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gürgey A, Ozalp I, Rötig A, Coşkun T, Tekinalp G, Erdem G et al (1996) A case of Pearson syndrome associated with multiple renal cysts. Pediatr Nephrol 10:637–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishihara H, Omoto M, Takao M, Higuchi Y, Koga M, Kawai M et al (2017) Autopsy case of the C12orf65 mutation in a patient with signs of mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurol Genet 3:e171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phadwal K, Vrahnas C, Ganley IG, MacRae VE (2021) Mitochondrial dysfunction: cause or consequence of vascular calcification? Front Cell Dev Biol 9:611922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanji K, Kunimatsu T, Vu TH, Bonilla E (2001) Neuropathological features of mitochondrial disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol 12:429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyahara H, Tamai C, Inoue M, Sekiguchi K, Tahara D, Tahara N et al (2023) Neuropathological hallmarks in autopsied cases with mitochondrial diseases caused by the mitochondrial 3243A>G mutation. Brain Pathol 33:e13199. 10.1111/bpa.13199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyahara H, Matsumoto S, Mokuno K, Dei R, Akagi A, Mimuro M et al (2019) Autopsied case with MERRF/MELAS overlap syndrome accompanied by stroke-like episodes localized to the precentral gyrus. Neuropathology 39:212–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S-J, Zhang J, Choi AMK, Kim HP (2013) Mitochondrial dysfunction induces formation of lipid droplets as a generalized response to stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 10.1155/2013/327167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadun AA (1994) Morphological findings in the visual system in a case of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Clin Neurosci 2:165–172 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerrison JB, Howell N, Miller NR, Hirst L, Green WR (1995) Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Electron microscopy and molecular genetic analysis of a case. Ophthalmology 102:1509–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carta A, Carelli V, D’Adda T, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA (2005) Human extraocular muscles in mitochondrial diseases: comparing chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol 89:825–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itkonen P, Collan Y (1983) Mitochondrial flocculent densities in ischemia. Digestion experiments. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A 91:463–468. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1983.tb02779.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Supplementary Figure 1: Brain FLAIR MRI findings from the index patient with MIMECK at age 66. Only nonspecific white matter lesions are visible. Diffusion-weighted images show no evidence of the stroke-like lesions seen in MELAS. FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MELAS, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MIMECK, mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging (PDF 88 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Figure 2: Brain MRS findings of the index patient with MIMECK at age 66. MRS was performed during a non-seizure session. Although the white matter lesion in the basal ganglia appeared nonspecific on conventional imaging, MRS at the same site revealed a lactate peak. CO2, carbon dioxide; CR, creatine; MIMECK, mitochondrial myopathy with episodic hyper-creatine kinase-emia; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy: NAA, N-acetylaspartate (PDF 59 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for ethical and privacy reasons, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.