Abstract

Objective

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a severe inflammatory disease associated with dysregulated glycolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction. This study investigates the therapeutic potential of quercetin, a novel PFKFB3 inhibitor, in modulating glycolysis and mitochondrial function to alleviate AP.

Methods

We conducted homology analysis of the PFKFB3 protein and identified quercetin as a potential inhibitor through molecular docking. In vitro experiments using a cerulein-induced inflammatory pancreatic cell model assessed the effects of quercetin on PFKFB3 expression, glycolysis, and mitochondrial function. In vivo validation was performed using an AP rat model to evaluate the impact on inflammation, tissue damage, and metabolic status.

Results

Quercetin significantly reduced PFKFB3 expression, inhibited glycolysis, and improved mitochondrial function in inflammatory pancreatic cells. In the AP rat model, quercetin treatment decreased serum amylase and lipase levels, reduced inflammatory markers (TNF-α and IL-6), and alleviated pancreatic tissue damage, as evidenced by histological analysis.

Conclusion

Quercetin effectively modulates glycolysis and mitochondrial function by inhibiting PFKFB3, thereby reducing inflammation and tissue damage in AP. These findings highlight the potential of quercetin as a novel therapeutic agent for AP.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-025-05845-z.

Keywords: PFKFB3, Glycolysis, Small Molecule Inhibitors, Acute Pancreatitis, Mitochondrial Function

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common and potentially dangerous acute inflammatory disease, with multifaceted etiology including gallstones, alcohol abuse, hyperlipidemia, and drugs [1–3]. The pathogenesis of AP involves injury and activation of pancreatic acinar cells, leading to aberrant activation and release of digestive enzymes, triggering self-digestion and inflammation of the pancreas [4–6]. Patients with AP typically present with sudden severe epigastric pain, accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and fever [1, 7, 8]. Severe cases may manifest systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ failure (MOF), posing a significant threat to patients'lives [9, 10]. Despite advancements in the treatment of AP, the mortality rate remains high, especially among critically ill patients [11]. Therefore, further research into the pathogenesis of AP, seeking new therapeutic targets and intervention strategies, holds crucial clinical significance [1, 7, 12].

In recent years, increasing evidence has highlighted the crucial role of the glycolytic pathway in the occurrence and progression of AP. Glycolysis is a key process in cellular energy metabolism, particularly important under hypoxic and high metabolic demand conditions [13]. During AP, the glycolytic pathway of pancreatic cells is significantly activated, leading to intracellular lactate accumulation and acidification, further exacerbating cell damage and inflammation. Additionally, activation of glycolysis can disrupt mitochondrial function, affecting cellular energy metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation, thereby worsening cell damage and inflammation [14–16]. Studies have shown that inhibiting the glycolytic pathway can effectively alleviate the inflammatory response and tissue damage in AP [17–19]. Therefore, modulation of the glycolytic pathway is considered a potential therapeutic strategy for intervening in AP [17–19].

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) is a key regulatory enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, catalyzing the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, thereby promoting glycolysis [20, 21]. PFKFB3 is highly expressed in multiple cell types and exhibits enhanced activity in various pathological conditions [22]. In AP, the overactivation of PFKFB3 may lead to abnormal enhancement of the glycolytic pathway, subsequently exacerbating the inflammatory response and damage to pancreatic cells [23, 24]. Recent studies have identified the significant role of PFKFB3 in cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and inflammatory conditions, with its inhibitors showing promising application in the treatment of these diseases [25–27]. However, research on the role of PFKFB3 in AP and its inhibitors remains limited [23]. Therefore, the development of novel PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitors and evaluating their potential in the treatment of AP hold significant research importance [28, 29].

Based on the aforementioned background, this study aims to develop novel small molecule inhibitors targeting PFKFB3 to regulate the glycolytic pathway, thus alleviating inflammation and cellular damage in AP. Small molecule inhibitors possess strong target specificity and stable drug metabolism, showing promising prospects in the treatment of various diseases in recent years. Using a variety of bioinformatics tools, this study screened for small molecule compounds that exhibit inhibitory effects on PFKFB3 and evaluated their efficacy through in vitro cellular models and in vivo animal models. Specifically, homology analysis of the PFKFB3 protein was conducted using the BLAST tool in the UniProt database to explore its conservation. Subsequently, small molecule compounds inhibiting PFKFB3 were retrieved and selected from the Drug SIGNatures DataBase, followed by molecular docking analysis using tools like AutoDockTools, and screening for key molecules with inhibitory effects on PFKFB3 based on Lipinski's rule of 5. Finally, the therapeutic effects of these small molecule inhibitors were assessed in an in vitro inflammatory pancreatic cell model induced by cerulein and an AP rat model.

The primary objective of this study is to screen and evaluate novel PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitors, investigating their therapeutic effects on the glycolysis and mitochondrial function in AP. Through systematic bioinformatics analysis, molecular docking, and in vitro and in vivo experiments, this study aims to elucidate the mechanism of action of PFKFB3 inhibitors in AP, providing a novel intervention approach. By establishing an AP rat model, measuring serum amylase, lipase levels, inflammation markers, and conducting histopathological evaluation, immunohistochemistry, and Western blot analysis, the therapeutic effects of the small molecule inhibitors are comprehensively assessed. These findings not only contribute to a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of AP but also offer new insights for developing effective therapeutic drugs, holding significant scientific research and clinical application value. By targeting PFKFB3 to regulate the glycolytic pathway and mitochondrial function, this study provides robust scientific support for novel therapeutic strategies for AP, indicating the potential of these inhibitors as promising therapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Identification and homology analysis of human PFKFB3 protein

The amino acid sequence of the human PFKFB3 protein (UniProt Accession: Q16875) was retrieved from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Subsequently, functional and structural domain predictions were conducted using the InterPro database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). The crystal structure of human PFKFB3 protein (RCSB PDB id: 2dwo) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Homology analysis of the human PFKFB3 protein was performed using the BLAST tool in the UniProt database.

Search for small molecule inhibitors of PFKFB3

Utilize the Drug Signatures Database (https://dsigdb.tanlab.org/DSigDBv1.0/) to identify entries that modulate PFKFB3, and based on the information provided by the database, select small molecule compounds that exhibit inhibitory effects on PFKFB3 (downregulation or decreased expression) for further analysis.

Molecular simulation docking

Small molecule compounds'2D structures were retrieved from the PubChem database and converted into 3D structures using ChemOffice 3D software, followed by energy minimization using the MM2 algorithm. The crystal structure of the receptor protein was obtained from the Protein Data Bank, and PyMOL software was utilized to remove ligands and solvents from the receptor protein structure. The target protein receptor molecules were prepared using AutoDockTools 1.5.7 software by adding hydrogens, computing charges, and converting compounds and target protein receptors into"pdbqt"files, setting appropriate Grid Box parameters. In cases where the binding status between compounds and receptor proteins is unknown, efforts were made to encompass more of the protein structure within the Grid Box. Subsequently, molecular simulation docking was performed using Vina 1.2.5 software to calculate docking energy values, and the results were visualized using PyMOL software.

Lipinski's rule of 5 for screening key small molecule compounds

According to the information provided by the Drug Signatures Database, screening compounds that adhere to Lipinski's Rule of 5 is crucial. This rule encompasses a molecular weight not exceeding 500 Daltons, no more than 5 hydrogen bond donors, no more than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, and a clog P value less than or equal to 5.

Establishment of an inflammatory pancreatic cell model

AR42J cells from rat pancreas were obtained from Nanjing CbpBio Co., Ltd. (CBP60990) and cultured in F-12 K medium (21127022, Thermo Fisher, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (10099158, Thermo Fisher, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a CO2 incubator. To mimic the inflammatory environment of pancreatic cells, the AR42J cell line was induced with cerulein. The inflammatory pancreatic cell model was constructed as follows: Model group was exposed to 10 nM cerulein, Normal group received an equivalent amount of phosphate-buffered saline, and Model + quercetin group was treated with 10 nM cerulein (17650-98-5, Absin) and 50 nM quercetin (PHR1488, Supelco) for 24 h. Additionally, AR42J cells were treated with fisetin (50 µM, PHL82542, PhytoLab), sanguinarine (2 µM, S9032, Selleck), and alsterpaullone (5 µM, S0354, Selleck) for 24 h separately [30, 31].

Cell metabolism assays

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were determined and analyzed using the Agilent Seahorse XF96 Analyzer (103179–100) following the manufacturer's protocol. AR42J cells were seeded into the wells of a cell culture microplate. For OCR measurements, cells were sequentially treated with oligomycin (10–3 mM), carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy), phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (10–3 mM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A (5 × 10–4 mM) using the Seahorse XF Mitochondrial Stress Test Kit (103015–100). The OCR was recorded using the XF96 Analyzer. For ECAR measurements, cells were sequentially exposed to glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (10–3 mM), and 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG; 50 mM) using the Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit (103020-100), and the ECAR was recorded using the XF96 Analyzer.

Western blot

Total protein from tissues was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer containing PMSF (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, P0013C). The samples were incubated on ice for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 8000 g for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The concentration of total protein was determined using a BCA assay kit (ThermoFisher, USA, 23227). Subsequently, 50 μg of protein was mixed with 2 × SDS loading buffer, boiled at 100 °C for 5 min, and then separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (ThermoFisher, USA, 88518) and blocked with 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, 9048–46-8) at room temperature for 1 h. The PVDF membrane was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-PFKFB3 rabbit antibody (1:1000, ab181861, Abcam, UK), anti-PFK-1 rabbit antibody (1:1000, ab155564, Abcam, UK), anti-LDH rabbit antibody (1:1000, ab222910, Abcam, UK), and anti-β-actin rabbit antibody (1:1000, ab8227, Abcam, UK). After washing with TBST three times for 10 min each, the membrane was incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (1:2000, ab97051, Abcam, UK) for 1 h, followed by additional TBST washes before being placed on a clean glass plate. ECL chemiluminescence reagent kit (abs920, Absin (Shanghai) Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) A and B solutions were mixed in the darkroom, then added onto the membrane. The membrane was imaged using the Bio-Rad imaging system and analyzed with Quantity One v4.6.2 software to determine the relative protein content represented by the grayscale value of the corresponding protein band/β-actin protein band. The experiment was repeated three times, and the average values were calculated.

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

The MMP was measured using a mitochondrial staining reagent JC-1 (40706ES60, Yisheng Biotech). Cells from different groups were incubated with 2 µM JC-1 for 15 min without illumination. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer.

Cloning, expression, and purification of PFKFB3

Human PFKFB3 cDNA was amplified from a mammalian expression plasmid and subcloned into the pET-30b(+) vector (Novagen, 69910-M, Sigma). The recombinant plasmid pET-30b(+)-PFKFB3C-termHis was then transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells (Novagen, 69450-M, Sigma). To express and purify PFKFB3, 1 L of transformed BL21-PFKFB3 culture was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Subsequently, an additional 1 L of Luria–Bertani medium containing 2 mmol/L IPTG (final concentration 1 mmol/L) was added, and the culture was shaken at 30 °C for 4 h. Bacterial pellets were harvested by centrifugation and subjected to protein purification under native conditions according to the Qiaexpressionist protocol (Qiagen). For further purification, the eluted fractions were dialyzed in 20 mmol/L Tris–HCl and 200 mmol/L NaCl (pH 7.4) buffer and purified by gel filtration using a Sephadex S200 column (GE28-9909–44, Sigma).

PFKFB3 enzyme activity assay

PFKFB3 enzymatic activity was measured using a coupled kinetic assay combining pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase. In the 3PO-inhibited control reactions, varying concentrations of 3PO were used without the addition of PFKFB3. Enzymatic kinetic parameters, including Vmax, Km, and Ki for PFKFB3 and 3PO inhibition, were calculated using the enzyme kinetics module in SigmaPlot 9.0.

Lentiviral vector construction and transduction

The full-length cDNA of PFKFB3 was amplified by RT-PCR using mRNA extracted from AR42J cells as a template. Specific primers were designed as follows: forward primer: 5′-TAG GAT CCA TGG ACT ACA AGG ACG ACG ACG ACA AGT TGG AAC TGA CGC AGA GCC GA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-TGA AGC TTG GAA ATG GAA TGG AAC CGA C-3′. The PCR product was digested with BamHI (R3136; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and HindIII (D6389; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), and ligated into a lentiviral vector. A lentiviral vector expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used as a control.

In addition, a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting rat PFKFB3 was designed (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) and cloned into a pBluescript SK(+) plasmid (pU6) containing the U6 promoter. The U6-shRNA cassette was then subcloned into a lentiviral vector. A lentiviral vector carrying a non-targeting shRNA against firefly luciferase (shNC) served as the negative control. Thus, a lentiviral vector carrying a shRNA targeting PFKFB3 (shPFKFB3) was successfully constructed.

Subsequently, AR42J cells were transduced with the lentivirus (shPFKFB3 or shNC) according to a previously described method [32]. Lentiviral particles were harvested after 3 days of purification and concentration for use in further functional assays.

ROS detection

Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with 10 μM dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH-DA, C2938, Thermo Fisher) for ROS detection. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted using a BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer (BD Biosciences, USA) and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Establishment and treatment of AP rat model

Eighteen healthy male SD rats (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Shanghai Slake Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. They were housed in SPF-grade animal experiment rooms with a humidity of 60% to 65% and a temperature of 22 to 25 °C, under a 12-h light–dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Following one week of acclimatization, the rats were observed for their health status before the experiment. The experimental protocol and animal use procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee.

AP was induced by intraperitoneal injection of caerulein, with a dose of 50 μg/kg administered every hour for a total of 7 injections to the rats in the AP group. The control group received an equivalent volume of physiological saline intraperitoneally. Prior to injection, the rats were positioned supine, and the injections were administered on the right side of the lower abdomen along the ventral midline, angled approximately 45° to the rat's body. Care was taken to check for blood or intestinal fluids during injection to avoid intravascular, bladder, or intestinal injection. The rats were divided into three groups: the Control group (blank control rats), the AP group (AP model group), and the AP + quercetin group (rats with AP induced and administered quercetin). Quercetin (Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally in the AP + quercetin group three times: 12 h and 6 h before AP induction and 6 h after AP induction, each time at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight [33, 34]. Subsequently, the rats were euthanized, blood samples were taken from the heart for the measurement of serum amylase, lipase, and cytokines, and pancreatic tissues were collected for subsequent histological analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Rat serum was collected and experimental procedures were strictly followed according to the instructions provided in the ELISA kit to determine the levels of inflammatory factors. The ELISA kits used in the experiments were for TNF-α (ab236712, Abcam, UK) and IL-6 (ab234570, Abcam, UK).

Immunohistochemical staining

Rat pancreatic tissues were collected, fixed in 10% formalin solution, and subjected to two rounds of paraffin removal using xylene, each lasting 10 min. The tissues were then hydrated in a series of ethanol–water solutions with concentrations of 100%, 95%, 75%, and 50%, for 5 min each, followed by the addition of 1 drop of H2O2 and an incubation at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, microwave treatment with 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer for 20 min was performed for antigen retrieval, followed by the addition of 1 drop of normal goat serum. After a 5-min incubation at room temperature and removal of the serum, the tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against PFKFB3 (1:1000, ab181861, Abcam, UK), PFK-1 (1:1000, ab155564, Abcam, UK), and LDH (1:1000, ab222910, Abcam, UK). The next day, incubation at 37 °C for 1 h was followed by incubation with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500, ab150077, Abcam, USA) at 37 °C for 30 min. The addition of freshly prepared DAB chromogen (product code: DA1015, Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was done for 1–2 min, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin (product code: G1080, Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 1 min. Subsequently, dehydration, clearing, and mounting with neutral resin were carried out. Five representative high-power fields were randomly selected and observed under an optical microscope.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Tissues were embedded in paraffin, then deparaffinized and rehydrated through a gradient of alcohols. They were stained with hematoxylin (#AR-0711, Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1–2 min, followed by eosin staining with eosin Y (#AR-0731, Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the tissues were dehydrated through a gradient and mounted on slides. The extent of tissue damage and necrosis was qualitatively assessed by experienced morphologists through computer-assisted morphological examination.

Measurement of serum amylase and lipase

Serum amylase and lipase are the most common serum markers in AP, serving as indicators of the severity of the condition. After blood collection from rats, the activity of lipase and amylase in the serum was measured using the Lipase Assay Kit (#A054-1–1, Nanjing Jiancheng Company) and the Amylase Assay Kit (#BC0615, Solarbio Company).

Statistical analysis methods

The data were obtained from at least three independent experiments and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). To compare between two groups, a two-sample independent t-test was employed. For comparisons involving three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. If the ANOVA results indicated significant differences, Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test was performed to compare differences between each group. In cases of non-normal distribution or heterogeneous variance in the data, the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis H test was utilized. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and R programming language. The significance level was set at 0.05, with a two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

High conservation of PFKFB3 protein across species

Our previous research has shown significant upregulation of PFKFB3 in AP, and inhibiting PFKFB3 can greatly alleviate AP symptoms [23]. Small molecule targeted therapy involves the use of specific molecular drugs (such as small molecule compounds, nucleic acids, proteins, etc.) that target and inhibit molecular proteins and signaling pathways closely associated with inflammation progression, thereby suppressing inflammation and achieving therapeutic effects [35]. This study aims to screen novel small molecule inhibitors of PFKFB3 to provide new drug options for AP treatment.

PFKFB3 encodes the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 protein, consisting of 520 amino acids, with its two-dimensional and three-dimensional structures shown in Fig. 1A, B. To investigate the conservation of PFKFB3 protein across species, we conducted a homology comparison of the amino acid sequences of PFKFB3 proteins through the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) BLAST tool. The results indicate that the similarity between human PFKFB3 protein (UniProt Accession: Q16875) and the corresponding proteins of other species ranges from 95.2% to 100%. Specifically, the similarity with Gorilla gorilla gorilla (UniProt Accession: A0A2I2ZVY7; A0A2I2Z683), Pan paniscus (UniProt Accession: A0A2R8ZUU5; A0A2R8ZY94), Pan troglodytes (UniProt Accession: H2Q1L1; A0A2I3S0X2), and Pongo abelii (UniProt Accession: A0A2J8VK62) is 100%, while it is 97.7% and 97.1% with the corresponding proteins of Mus musculus (UniProt Accession: A2AUP1) and Rattus norvegicus (UniProt Accession: O35552-6). The Fast Family and Domain Prediction (FFDP) alignment results demonstrate high sequence and structural domain similarity between human, mouse, and rat PFKFB3 proteins (Fig. 1C), suggesting a high degree of functional similarity, indicating the reliability of studying PFKFB3 function in mouse and rat models.

Fig. 1.

Structure of human PFKFB3 protein and homology comparison results. Note: (A) Schematic diagram of the PFKFB3 protein structure, displaying functional domains (Representative Domains and Domains), protein family, and homologous superfamily information, with name labels on the right, sourced from InterPro; (B) Three-dimensional structure of PFKFB3 (RCSB PDB id: 2dwo), sourced from RCSB PDB; (C) Fast family and domain prediction results for human, rat, and mouse PFKFB3 compared to the query sequence (Query Sequence), with the input sequence being the human PFKFB3 sequence (Uniprot Accession: Q16875). The red background indicates the alignment region, whereby a longer red region signifies higher similarity between the sequences, accompanied by annotations of predicted structural domains on the right

Overall, these results indicate a high degree of conservation of the PFKFB3 protein across species.

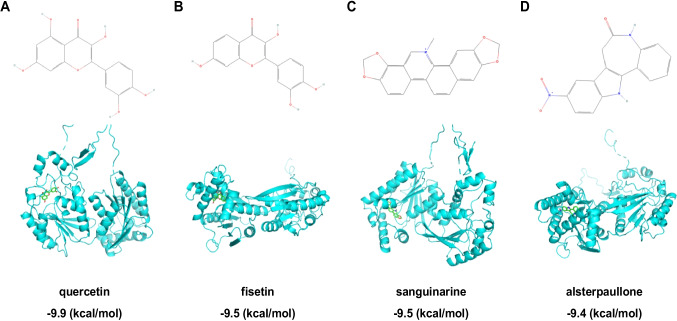

Screening of novel PFKFB3 inhibitors through molecular docking

In the search for small molecular compounds with inhibitory effects on PFKFB3, we retrieved 84 entries with regulatory effects on PFKFB3 from the Drug Signatures Database (https://dsigdb.tanlab.org/DSigDBv1.0/), which included 32 small molecules exhibiting inhibitory effects on PFKFB3 (DOWN or decreases expression) (Supplementary material 1).

Subsequently, we validated the binding of these small molecules with PFKFB3. Molecular docking analysis of the small molecule compounds and the receptor protein was conducted using software such as AutoDockTools 1.5.7 and Vina 1.2.5 [36]. Among these, 27 small molecules were analyzed for molecular docking with the protein, excluding 0175029–0000 and 0198306–0000 due to the lack of corresponding PubChem information, as well as 7646–79-9, ARSENIC, and Silica which are inorganic small molecules and do not meet the molecular docking format requirements.

The study demonstrated that when the binding energy is < 0 kcal/mol, there is an interaction and spontaneous binding potential between the receptor protein and the small molecule compound. The lower the binding energy, the more stable the complex conformation [37]. The molecular docking results indicated that all 27 small molecules can freely bind with PFKFB3, with binding energies ranging from −4.6 kcal/mol to −9.9 kcal/mol. Among these, the five small molecule compounds with the lowest binding energies were identified as quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, staurosporine, and alsterpaullone (Figs. 2A-D) (Fig. S1) (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Molecular structures of four key small compounds and their molecular docking modes with PFKFB3. Note: (A-D) depict the structural formulas of quercetin (A), fisetin (B), sanguinarine (C), and alsterpaullone (D), along with their molecular docking modes with PFKFB3. The figures present the 3D structures of the small compounds and the secondary structure of the receptor protein

For orally administered drugs to enter systemic circulation, they must dissolve in the acidic environment of the stomach and pass through the cell membranes of the intestines, which is related to the solubility and permeability of small molecular compounds [38, 39]. Lipinski's Rule of 5 (Lipinski rule) is one of the primary methods used to assess the balance between drug solubility and permeability and is a crucial criterion for designing orally administrable drugs [40]. Therefore, we queried the Drug Signatures Database to evaluate if the five small molecule compounds with the lowest binding energies comply with Lipinski's Rule. The results indicated that quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone fully adhere to Lipinski's Rule, while staurosporine violates the rule of cLogP < 5.0 (Table S2). Consequently, we consider quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone as potential key compounds for inhibiting PFKFB3 and will subject them to further analysis.

In conclusion, the results suggest that quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone may serve as crucial compounds for inhibiting PFKFB3.

The novel PFKFB3 Inhibitor significantly regulates the metabolic state and oxidative stress in caerulein-treated pancreatic cells

Based on the bioinformatics analysis, it is hypothesized that quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone may serve as key compounds in inhibiting PFKFB3. To validate this hypothesis, experiments were conducted using four selected small molecule inhibitors in an in vitro inflammatory pancreatic cell model induced by caerulein. Results revealed a significant upregulation of PFKFB3 protein expression in the caerulein-induced inflammatory pancreatic cell model, and the four compounds, quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone, all showed a marked reduction in PFKFB3 protein levels within this model, with quercetin demonstrating the most profound effect by reducing PFKFB3 protein levels by approximately 60% (Fig. 3A). Based on these results, quercetin was selected for further in-depth analysis.

Fig. 3.

Regulatory effects of the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin on metabolism and oxidative stress in inflammatory pancreatic cells. Note: (A) Western blot analysis of PFKFB3 protein expression levels in inflammatory pancreatic cells induced by zymosan after treatment with four small molecule inhibitors. (B) Seahorse XF analyzer measurement of OCR in pancreatic cells after treatment with the compound quercetin. (C) Seahorse XF analyzer measurement of ECAR in pancreatic cells after treatment with the compound quercetin. (D) Western blot analysis of PFK-1 and LDH enzyme expression levels. (E) JC-1 staining of MMP in different cell groups. (F) ROS levels in different cell groups measured using a ROS detection kit. * indicates P < 0.05 compared to the Normal group, # indicates P < 0.05 compared to the Model group, all cell experiments were repeated three times

Using Seahorse XF analyzer, the OCR and ECAR of pancreatic cells post-quercetin treatment were measured. Data indicated that quercetin treatment significantly decreased glycolytic rate, OCR, and ECAR, suggesting that quercetin inhibits the energy metabolism activities of pancreatic cells (Fig. 3B, C). Western blot analysis of PFK-1 and LDH enzyme expression revealed a significant decrease in PFK-1 and LDH enzyme levels with quercetin treatment (Fig. 3D).

Changes in MMP were evaluated using JC-1 staining. Compared with the Normal group, cells in the Model group showed a marked decrease in JC-1 red fluorescence (aggregates) and an increase in green fluorescence (monomers), resulting in a significantly reduced aggregate-to-monomer ratio. This indicates a substantial loss of MMP and impaired mitochondrial function. However, following quercetin treatment (Model + Quercetin group), the JC-1 aggregate-to-monomer ratio significantly increased compared with the Model group, suggesting that quercetin markedly improved or restored MMP, exerting protective or reparative effects on mitochondrial function (Fig. 3E).

Meanwhile, intracellular ROS levels were assessed using a ROS detection kit. Compared with the Normal group, ROS levels were significantly elevated in the Model group. Quercetin treatment (Model + Quercetin group) significantly reduced ROS levels compared with the Model group, indicating that quercetin effectively alleviated oxidative stress in the inflammatory cell model (Fig. 3F). These results demonstrate that the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin effectively modulates the metabolic state and oxidative stress response in caerulein-treated pancreatic cells by regulating glycolytic pathways and mitochondrial function.

PFKFB3 knockdown attenuates metabolic dysregulation and oxidative stress in caerulein-treated pancreatic cells

To further verify the pivotal role of PFKFB3 in metabolic disturbance and cellular stress, we established a PFKFB3 knockdown model in AR42J cells and systematically evaluated its effects on energy metabolism and oxidative stress. Seahorse XF analysis revealed that basal respiration and maximal respiratory capacity (measured by OCR) were significantly decreased in the Model group, while PFKFB3 knockdown markedly restored respiratory function (Fig. S2A).Regarding glycolytic function, the glycolysis rate and glycolytic reserve (measured by ECAR) were significantly elevated in the Model group but were significantly reduced after sh-PFKFB3 treatment (Fig. S2B), indicating an alleviation of glycolytic overactivation. Western blot analysis further demonstrated that the key glycolytic enzymes PFK-1 and LDH were upregulated in the Model group, whereas their protein levels were markedly downregulated following PFKFB3 silencing (Fig. S2C). MMP (ΔΨm), assessed by JC-1 staining, showed a decreased red/green fluorescence ratio in the Model group, indicating mitochondrial depolarization, which was partially reversed by PFKFB3 knockdown (Fig. S2D).In addition, ROS levels detected using DCFH-DA staining were significantly elevated in the Model group, while PFKFB3 knockdown significantly reduced ROS production (Fig. S2E).

Further dynamic monitoring of metabolite levels revealed that quercetin treatment significantly decreased lactate, Fru-2,6-BP, and 2-DG uptake, indicating reduced glycolytic flux; this was accompanied by decreased levels of NAD+, NADH, and ATP, suggesting overall suppression of cellular energy metabolism (Fig. S2F).

Collectively, these results indicate that PFKFB3 plays a critical role in regulating pancreatic cell metabolic disorders, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction under inflammatory conditions. Quercetin, as a PFKFB3 inhibitor, exerts similar effects at both molecular and functional levels as PFKFB3 knockdown.

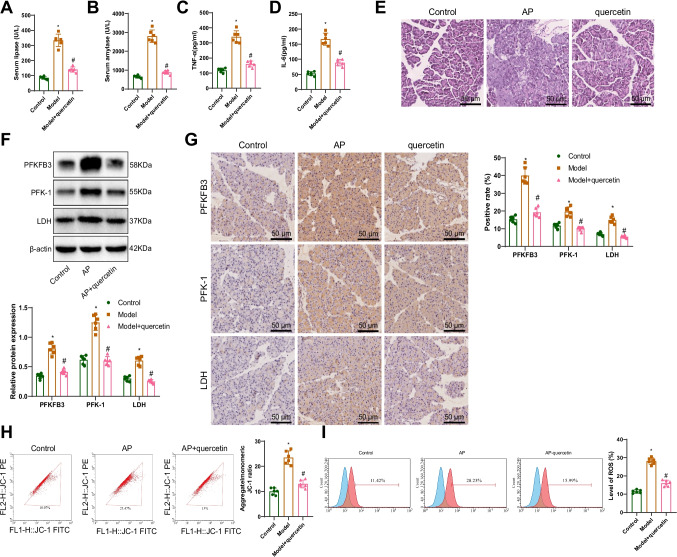

Inhibition of PFKFB3 significantly reduces inflammation in rats with pancreatitis and improves metabolic status

As shown in Fig. 3, these in vitro results demonstrate that the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin effectively modulates the metabolic status and oxidative stress response of caerulein-induced pancreatic cells by regulating glycolytic pathways and mitochondrial function. To further explore the in vivo effects of quercetin in AP, we established a rat model of AP. In order to assess both the preventive and therapeutic effects of quercetin, the treatment group received intraperitoneal injections of quercetin (50 mg/kg) at 12 h and 6 h before, and 6 h after AP induction (Model + Quercetin group). The findings revealed that compared to the Control group, the levels of serum amylase and lipase in the AP group were significantly increased. However, after treatment with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin, these levels in the serum of AP rats were notably decreased (Fig. 4A, B). Moreover, ELISA analysis of the concentrations of the inflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-6 showed a significant increase in TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the AP group rats compared to the Control group rats. Following treatment with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin, the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in the AP group rats were significantly reduced (Fig. 4C, D). Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to examine the tissue morphology of pancreatic tissues in each group. The pancreatic tissues of rats in the AP group exhibited interstitial congestion, edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, focal or coalescent necrosis, and hemorrhage. Treatment with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin markedly alleviated the inflammation and necrosis in pancreatic tissues, with only mild inflammatory reactions and minimal necrosis observed (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Improvement of inflammation and metabolism in a rat model of AP by PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin. Note: (A, B) Measurement of serum amylase and lipase levels; (C, D) ELISA experiments to assess IL-6 and TNF-α secretion; (E) Pathological changes in rat pancreatic tissues observed using H&E staining (scale bar: 50 µm); (F) Detection of PFKFB3, PFK-1, and LDH expression in rat pancreatic tissues using the Western blot method; (G) Immunohistochemical analysis of PFKFB3, PFK-1, and LDH expression in rat pancreatic tissues (scale bar: 50 µm); (H) Assessment of MMP in rat pancreatic tissues of each group using JC-1 staining; (I) Measurement of ROS levels in rat pancreatic tissues of each group using an ROS detection kit. * Represents P < 0.05 compared to the Control group, # represents P < 0.05 compared to the AP group, with six rats in each group

Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis were performed to assess the expression changes of PFKFB3 and related glycolytic and mitochondrial proteins in pancreatic tissues. The results indicated a significant increase in the expression of PFKF3, PFK-1, and LDH in the pancreatic tissues of rats in the AP group compared to the Control group. However, treatment of rats in the AP group with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin led to a significant decrease in the expression of PFKF3, PFK-1, and LDH in pancreatic tissues (Fig. 4F, G). Evaluation of MMP showed a significant increase in the membrane potential in the pancreatic tissues of rats in the AP group compared to the Control group. Conversely, treatment with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin resulted in a significant decrease in the membrane potential in pancreatic tissues of AP rats (Fig. 4H). Analysis of ROS levels demonstrated a significant increase in ROS levels in the pancreatic tissues of rats in the AP group compared to the Control group. However, treatment with the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin led to a significant decrease in ROS levels in the pancreatic tissues of AP rats (Fig. 4I). These findings suggest that the PFKFB3 inhibitor quercetin not only effectively suppresses inflammatory responses in a rat model of AP but also improves the metabolic status of pancreatic tissues and reduces oxidative stress.

Discussion

AP is a complex and potentially life-threatening inflammatory disease involving various biological processes, including disruptions in glycolysis and mitochondrial function [1, 8, 41]. This study aims to develop and evaluate a novel small molecule inhibitor of PFKFB3 to regulate glycolysis and alleviate inflammation-induced damage in AP. Previous research has highlighted the significant role of glycolysis in acute inflammation; however, there is limited research on the specific function of PFKFB3 and its inhibitors in AP [28, 42, 43]. Employing a variety of methods, this study systematically screened and assessed PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitors, with a particular focus on quercetin, demonstrating its potential in the treatment of AP. This paper delved into the similarities and differences between this study and previous research, providing a comprehensive evaluation of its scientific and clinical significance.

In this study, a combination of bioinformatics tools and experimental validation was employed in the research methodology to conduct a series of screening and evaluations. Initially, the homology of the PFKFB3 protein was investigated using the UniProt database BLAST tool to explore its conservation across different species. The results revealed a high degree of conservation, with human PFKFB3 sharing 97.7% similarity with mice and 97.1% with rats. Subsequently, small-molecule compounds inhibiting PFKFB3 were identified and selected from the Drug SIGnatures DataBase. Molecular docking analysis was carried out using AutoDockTools, and key molecules were further refined based on Lipinski's rule of 5. Through a multi-tiered screening approach, 27 potential inhibitors were identified, with binding energies ranging from −4.6 kcal/mol to −9.9 kcal/mol. Among these, quercetin, fisetin, sanguinarine, and alsterpaullone were identified as the most promising inhibitors. This screening strategy demonstrated higher accuracy and effectiveness compared to previous studies [44–46].

Although some studies have explored the role of PFKFB3 in AP, this study provides a more systematic and comprehensive investigation of its function and therapeutic potential in AP. In in vitro experiments, we found that small molecule inhibitors such as quercetin significantly reduced PFKFB3 protein expression in caerulein-induced inflammatory pancreatic cells, suppressed glycolysis, and subsequently decreased mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation activity. Specifically, using a caerulein-induced inflammatory pancreatic cell model, we observed that quercetin treatment markedly lowered intracellular PFKFB3 levels and glycolytic enzyme expression, reduced OCR and ECAR, and improved MMP stability as assessed by JC-1 staining. In addition, ROS detection assays demonstrated that quercetin significantly decreased intracellular ROS levels, thereby alleviating oxidative stress. Knockdown of PFKFB3 expression using shRNA also mimicked the therapeutic effects of quercetin (Fig. S2). These findings suggest that quercetin modulates the glycolytic pathway and mitochondrial function by inhibiting PFKFB3 activity in vitro, thereby mitigating inflammatory responses.

In in vivo experiments, we further validated the therapeutic efficacy of quercetin using a rat model of AP induced by caerulein, which displayed typical features of pancreatic inflammation and tissue injury. The results of the study showed that treatment with quercetin significantly alleviated pancreatic inflammation and injury in the rats, reduced the levels of amylase and lipase in the serum, lowered the expression of inflammatory markers such as TNF-α and IL-6, and improved the pathological changes in pancreatic tissue. Through H&E staining and immunohistochemical analysis, we observed that quercetin markedly reduced the infiltration of inflammatory cells and tissue structural damage in the pancreatic tissue. Additionally, Western blot analysis showed a significant decrease in the expression of PFKFB3, glycolytic enzymes, and mitochondrial function-related proteins in the pancreatic tissue of the quercetin-treated group. These findings are consistent with the effects of PFKFB3 inhibitors in different disease models from other studies, providing further confirmation of their specificity and effectiveness in the treatment of AP [23].

Through an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms by which quercetin regulates the glycolysis pathway and mitochondrial function, this study discovered that quercetin can inhibit the activity of PFKFB3, reducing the expression of key enzymes in the glycolysis process, thereby decreasing the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes, alleviating cellular oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Specifically, by lowering the expression of PFKFB3, quercetin decreases the production of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, thus inhibiting the glycolysis pathway. This mechanism is consistent with previous studies that identified disruptions in glycolysis and mitochondrial function during acute inflammation, but this study further elucidated the specific role played by PFKFB3 in this process. Additionally, quercetin regulates MMP and reduces ROS generation, thereby safeguarding mitochondrial function in cells. These mechanistic studies not only deepen our understanding of the role of PFKFB3 in AP but also lay a theoretical foundation for the development of more effective treatment strategies.

In summary, this study screened and evaluated novel PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitors, particularly quercetin, demonstrating their therapeutic efficacy in regulating the glycolysis pathway and mitochondrial function in AP. The results indicate that quercetin effectively mitigates cell damage and tissue inflammation in AP, presenting a new intervention strategy. These findings not only contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of AP but also offer new insights for the development of effective therapeutic drugs, with significant scientific research and clinical application value. Future research should focus on optimizing the structure of small molecule inhibitors, expanding the sample size in experiments, and conducting clinical trials to advance the clinical application of this novel treatment strategy. Through this study, we not only reveal the crucial role of PFKFB3 in AP but also provide new hope and direction for its treatment.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed a novel small molecule inhibitor of PFKFB3, quercetin, which alleviated inflammation damage and cellular stress in an AP model by modulating the glycolytic pathway and inhibiting the activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex (Fig. 5). Through a series of bioinformatics and laboratory techniques, we demonstrated that quercetin significantly reduced PFKFB3 expression in both in vitro and in vivo models, improving energy metabolism, reducing oxidative stress, and promoting the alleviation of inflammatory response and restoration of cell function.

Fig. 5.

PFKFB3 small molecule inhibitors mitigate AP by modulating glycolysis and mitochondrial function

This study provides compelling evidence for PFKFB3 as a potential therapeutic target for AP treatment and illustrates the feasibility of regulating its activity through small molecule inhibitors. The scientific significance lies in uncovering the association between the glycolytic pathway and AP, while also offering possible new treatment options in clinical settings. However, the study still has limitations, such as the long-term efficacy and safety of the small molecule inhibitor quercetin that have not been validated in broader preclinical trials. Future research needs to assess its effectiveness and safety in larger animal models and final clinical trials, as well as explore the potential for combination therapy with other treatment methods. Furthermore, deeper mechanistic studies will help optimize inhibitor design, enhancing their selectivity and therapeutic efficiency.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Molecular docking patterns. Note: (A) Molecular docking patterns of the remaining 23 small molecular compounds with PFKFB3 are shown in the figure, depicting the 3D structures of the small molecular compounds and the secondary structure of the receptor protein (PDF 1321 KB)

Supplementary file2 PFKFB3 knockdown alleviates metabolic dysregulation and oxidative stress in caerulein-treated pancreatic cells. Note: (A) Seahorse XF analysis of mitochondrial respiratory function; (B) Glycolytic function assessed by ECAR; (C) Western blot analysis of PFK-1 and LDH protein expression; (D) MMP (ΔΨm) evaluated by JC-1 staining and flow cytometry; (E) Intracellular ROS levels measured by DCFH-DA staining and flow cytometry; (F) Dynamic metabolic analysis after quercetin treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. Model group; #P < 0.05 vs. Quercetin or shRNA group. All experiments were performed in triplicate (PDF 2546 KB)

Author contributions

H.J., J.L., and Z.X. designed and conducted the experiments. Q.S. and J.T. performed data collection and analysis. H.Z. and Q.L. contributed to histological evaluation and animal model establishment. L.L. conceived and supervised the project, provided critical revisions, and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Provincial Financial Support Program/General Program (AHWJ2023A20220) and Anhui Higher Education Institution Scientific Research Project: 2024AH051287.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. Additional data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University. This study does not involve any clinical ethics or human participants.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Szatmary P, Grammatikopoulos T, Cai W et al (2022) Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs 82:1251–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerem E, Kurtcehajic A, Kunosić S et al (2023) Current trends in acute pancreatitis: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Gastroenterol 29:2747–2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Chen Y, Sun-Waterhouse D (2022) The potential of dandelion in the fight against gastrointestinal diseases: a review. J Ethnopharmacol 293:115272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgault J, Abner E, Manikpurage HD et al (2023) Proteome-wide mendelian randomization identifies causal links between blood proteins and acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 164:953-965.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiss L, Fűr G, Pisipati S et al (2023) Mechanisms linking hypertriglyceridemia to acute pancreatitis. Acta Physiol 237(3):e13916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Poggetto E, Ho I-L, Balestrieri C et al (2021) Epithelial memory of inflammation limits tissue damage while promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis. Science 373(6561):eabj0486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valverde-López F, Martínez-Cara JG, Redondo-Cerezo E (2022) Pancreatitis aguda. Med Clin 158:556–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strum WB, Boland CR (2023) Advances in acute and chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 29:1194–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen E, Xin G, Su W et al (2022) Activation of TLR4 induces severe acute pancreatitis-associated spleen injury via ROS-disrupted mitophagy pathway. Mol Immunol 142:63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips AE, Wilson AS, Greer PJ et al (2023) Relationship of circulating levels of long-chain fatty acids to persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 325:G279–G285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keeven DD, Harris CT, Davenport DL et al (2019) Cost burden and mortality in rural emergency general surgery transfer patients. J Surg Res 234:60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mederos MA, Reber HA, Girgis MD (2021) Acute pancreatitis. JAMA 325:382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Pan L-H, Li S-R et al (2022) Proteomics study on the intervention effect of Jingfang Heji on urticaria based on label-free quantitative proteomics technology. Chin J Chin Mater Med 47:5494–5501. 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20220506.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyssenko V, Vaag A (2023) Genetics of diabetes-associated microvascular complications. Diabetologia 66:1601–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Fu J-L, Hao H-F et al (2021) Metabolic reprogramming by traditional Chinese medicine and its role in effective cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res 170:105728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song MJ, Park C, Kim H et al (2023) Carnitine acetyltransferase deficiency mediates mitochondrial dysfunction-induced cellular senescence in dermal fibroblasts. Aging Cell 22(11):e14000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye L, Jiang Y, Zhang M (2022) Crosstalk between glucose metabolism, lactate production and immune response modulation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 68:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szwed A, Kim E, Jacinto E (2021) Regulation and metabolic functions of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Physiol Rev 101:1371–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul S, Ghosh S, Kumar S (2022) Tumor glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer Biol 86:1216–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones BC, Pohlmann PR, Clarke R, Sengupta S (2022) Treatment against glucose-dependent cancers through metabolic PFKFB3 targeting of glycolytic flux. Cancer Metastasis Rev 41:447–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakraborty A, Sreenivasmurthy SG, Miller W et al (2024) Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate restores DNA repair activity of PNKP and ameliorates neurodegenerative symptoms in Huntington’s disease.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 121(39):e2406308121. 10.1073/pnas.2406308121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hu K-F, Shu C-W, Lee C-H et al (2023) Comparative clinical significance and biological roles of PFKFB family members in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int 23(1):257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ergashev A, Shi F, Liu Z et al (2024) KAN0438757, a novel PFKFB3 inhibitor, prevent the progression of severe acute pancreatitis via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in infiltrated macrophage. Free Radic Biol Med 210:130–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han X, Bao J, Ni J et al (2024) Qing xia jie yi formula granules alleviated acute pancreatitis through inhibition of M1 macrophage polarization by suppressing glycolysis. J Ethnopharmacol 325:117750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin S, Li Y, Wang D et al (2021) Fascin promotes lung cancer growth and metastasis by enhancing glycolysis and PFKFB3 expression. Cancer Lett 518:230–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thirusangu P, Ray U, Sarkar Bhattacharya S et al (2022) PFKFB3 regulates cancer stemness through the hippo pathway in small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene 41:4003–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasprzak A (2021) Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling in glucose metabolism in colorectal cancer. IJMS 22:6434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu H, Lin J, Xu C et al (2021) Cyclosporine modulates neutrophil functions via the SIRT6–HIF-1α–glycolysis axis to alleviate severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Transl Med 11(2):e334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selinger M, Věchtová P, Tykalová H et al (2022) Integrative RNA profiling of TBEV-infected neurons and astrocytes reveals potential pathogenic effectors. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 20:2759–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H, Chen H, Zhou R (2023) Phospholipase D2 targeted by miR-5132-5p alleviates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis via the Nrf2/NFκB pathway. Immun Inflam Dis 11(5):e831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao X, Chen Q, Li N et al (2020) Serotonin-RhoA/ROCK axis promotes acinar-to-ductal metaplasia in caerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis. Biomed Pharmacother 125:109999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng F, Li Q, Sun J-Y et al (2018) PFKFB3 is involved in breast cancer proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis. Int J Oncol 52(3):945–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Junyuan Z, Hui X, Chunlan H et al (2018) Quercetin protects against intestinal barrier disruption and inflammation in acute necrotizing pancreatitis through TLR4/MyD88/p38 MAPK and ERS inhibition. Pancreatology 18:742–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miao B, Qi W, Zhang S et al (2019) Mir-148a suppresses autophagy by down-regulation of IL-6/STAT3 signaling in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 19:557–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedard PL, Hyman DM, Davids MS, Siu LL (2020) Small molecules, big impact: 20 years of targeted therapy in oncology. Lancet 395:1078–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trott O, Olson AJ (2009) Autodock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31:455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosa AD (2021) Docking-based analysis and modeling of the activity of bile acids and their synthetic analogues on large conductance Ca2+ activated K channels in smooth muscle cells. Eur Rev 25(23):7501–7507. 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27449 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Fine-Shamir N, Dahan A (2023) Solubility-enabling formulations for oral delivery of lipophilic drugs: considering the solubility-permeability interplay for accelerated formulation development. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 21:13–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahan A, Beig A, Lindley D, Miller JM (2016) The solubility–permeability interplay and oral drug formulation design: two heads are better than one. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 101:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ (1997) Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings 1PII of original article: S0169–409X(96), 00423–1. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 23(1–3):3–25 (1. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 46:3–26 (2001)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Berg FF, Boermeester MA (2023) Update on the management of acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Crit Care 29:145–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao M, Liu D, Xu Y et al (2023) Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in sepsis. Ann Med 55:1278–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu D, Xiao M, Zhou J et al (2023) PFKFB3 promotes sepsis-induced acute lung injury by enhancing NET formation by CXCR4hi neutrophils. Int Immunopharmacol 123:110737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jose L, Liu S, Russo C et al (2022) Artificial intelligence-assisted classification of gliomas using whole slide images. Arch Pathol Lab Med 147:916–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emam AA, Abdelaleem EA, Abdelmomen EH et al (2022) Rapid and ecofriendly UPLC quantification of remdesivir, favipiravir and dexamethasone for accurate therapeutic drug monitoring in covid-19 patient’s plasma. Microchem J 179:107580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Xie Y, Tong K et al (2023) Simultaneous screening and quantification of 479 pesticides in green tea by LC-QTOF-MS. Foods 12:4177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Molecular docking patterns. Note: (A) Molecular docking patterns of the remaining 23 small molecular compounds with PFKFB3 are shown in the figure, depicting the 3D structures of the small molecular compounds and the secondary structure of the receptor protein (PDF 1321 KB)

Supplementary file2 PFKFB3 knockdown alleviates metabolic dysregulation and oxidative stress in caerulein-treated pancreatic cells. Note: (A) Seahorse XF analysis of mitochondrial respiratory function; (B) Glycolytic function assessed by ECAR; (C) Western blot analysis of PFK-1 and LDH protein expression; (D) MMP (ΔΨm) evaluated by JC-1 staining and flow cytometry; (E) Intracellular ROS levels measured by DCFH-DA staining and flow cytometry; (F) Dynamic metabolic analysis after quercetin treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. Model group; #P < 0.05 vs. Quercetin or shRNA group. All experiments were performed in triplicate (PDF 2546 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. Additional data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.