Abstract

Objectives

The objective was to evaluate the beneficial effects of a reminiscence based intervention (‘Remember-ME’) on both cognitive (i.e. autobiographical memory and verbal memory) and psychological dimensions (i.e. life satisfaction, psychological well-being and loneliness) in cognitively intact community-dwelling older adults

Methods

A quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate the effects of the program, including a pre-test and a post-test. The total sample consisted of 52 healthy community-dwelling retirees without cognitive impairment aged between 60 and 83 years; 30 older adults were recruited in the experimental group and 22 older adults in the control group. The experimental group received 1.5 h of group-based reminiscence training (‘Remember-ME’) per week for 10 weeks.

Results

Significant effects were found on both cognitive and psychological measures. Specifically, the intervention significantly improved the subjective quality (i.e. vividness) of autobiographical memory, the level of life satisfaction along with reducing feeling of loneliness.

Conclusion

Structured group reminiscence may be an effective method for improving both autobiographical memory and mental health in older adults.

Keywords: Memory, autobiographical memory, aging, health aging, loneliness

Introduction

The worldwide phenomenon of population aging has become a major concern for care organizations and policy makers. Depressive symptoms and loneliness, which have a detrimental effect on mental and physical health, are common in the older adults [1,2], so defining effective strategies to tackle loneliness and depressive symptoms and to promote the psychological well-being has become a global priority for researchers and practitioners [3].

One promising strategy is reminiscence-based intervention that is psychosocial intervention based on the reminiscence process of autobiographical memory. As we review in the following, this type of intervention may serve as an effective non-pharmacological approach to improve mental health in late life, although more research is needed to confirm these effects and to extend the evaluation to other aspects, i.e. dimensions of cognitive functioning.

Autobiographical memory, reminiscence and mental health

Autobiographical memory (hereafter AM) refers to memory concerning an individual’s own life and includes both episodic and semantic aspects. A key feature of autobiographical memory retrieval is its phenomenology, that is the subjective experience associated with remembering one’s own personal past, how memories appear in one’s own conscious experience (for a review on the phenomenology of AM, see Chiorri & Vannucci [4]. One of the most relevant and commonly assessed phenomenological properties of AM is vividness, which refers to the visual clarity and intensity of the memory [e.g., 5]). In studies on age-related changes in AMs, older adults reported higher ratings of vividness, coherence and reliving compared to younger adults [6–8], despite the impairment in the retrieval of episodic details [9,10]. Changes in the phenomenology are also found to be linked to individual differences in subjective well-being and psychological distress [11,12] as well as to mental health outcomes [13].

In the context of aging, a relevant everyday cognitive activity and a way of accessing AM knowledge is reminiscence, that is thinking about or telling others about personally meaningful past experiences [14,15]. According to the tripartite functional model [16,17] reminiscence serves three main groups of functions, namely self-positive functions (i.e. identity construction, problem solving, and death preparation), self-negative functions (i.e. boredom reduction, bitterness revival, intimacy maintenance) and prosocial functions (i.e. teaching/informing others, conversation). In studies on reminiscence in older adults, self-positive functions have been associated with higher life satisfaction and lower psychological distress [e.g., 16], whereas self-negative functions have been associated with lower levels of wellbeing, increased symptoms of anxiety and depression and poorer perceived health and physical well-being [16,18].

Reminiscence- based intervention, psychological well-being and cognition

These patterns of associations between reminiscence functions and mental health have stimulated the development and implementation of reminiscence-based interventions, aiming at improving mental health and cognition in later life [19,20]. The structure and format (e.g. one-to-one or in groups) of reminiscence-based interventions may vary greatly depending on the amount of structure and the specific aims of the intervention. A key distinction is made between simple reminiscence and life-review interventions [21]. Both approaches are widely used in dementia care and have demonstrated positive effects on a broad range of psychological dimensions such as life satisfaction, quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms and cognitive functions [22,23]. Over the past decade, a growing body of research involving older adults without cognitive impairment has shown beneficial effects of reminiscence on psychological health, such as significant reductions in depressive symptoms and improvements in life satisfaction, quality of life and social engagement [19,24]; see, for a meta-analysis [20].

In contrast, evidence regarding the effects of reminiscence on cognitive functioning and specifically on memory in healthy older adults remains mixed. While some studies reported positive effects [25,26], others did not find any beneficial outcomes [27,28]. Interestingly, in a more recent study, Satorres et al. [29] found that a group-based structured reminiscence program [30,31] led to change in the functions of reminiscence of AM. Specifically, participants in the intervention group showed an increase in self-positive and prosocial functions and a decrease in self-negative functions, while the control group showed an increase in the self-negative functions.

The present study

Capitalizing on these findings, in the present study we aimed to further extend research on the beneficial outcomes of group-based reminiscence programs and we investigated the effects of the reminiscence intervention developed by Meléndez Moral et al. [30]; applied in Satorres et al. and Viguer et al. [29,31] on both cognitive and psychological functioning. As for cognitive functioning, we examined AM and specifically the phenomenological property of vividness of personal memories, and verbal memory for logically organized verbal information (i.e. a short story). As for the psychological dimensions, we assessed life satisfaction, subjective feeling of loneliness and psychological wellbeing. To this aim, in the study we implemented and applied the Italian version of this reminiscence-based intervention, called ‘Remember-ME’ (In Italian: Ricordando-Mi)

Methods

Participants

Participants included cognitively intact community-dwelling retired people who did not live in community centers or nursing homes. Several voluntary associations and trade unions in the Tuscany region were invited to a first meeting to present the project and ask for their commitment. The main representatives were asked to contact eligible participants, who were directly informed of the study in a meeting.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age ≥60 years (2) Retired (3) Provided informed consent to participate (4) No need for assistance with daily activities (5) No motor, visual, or hearing impairments that would interfere with the training (6) No significant cognitive impairment, as measured by Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Moca) [32]. Following Conti et al. [33], we included those with a score of 19.5 or greater. Those who did not meet the above criteria were excluded from the study. Specifically, one participant was excluded because of cognitive impairment and another one decided to withdraw from the study after 3 sessions. The final total sample consisted of 52 individuals aged between 60 and 83 years old, with a mean age of 69.90 years (SD = 5.45); 30 older adults (9 men and 21 women) were assigned to the experimental group, and 22 older adults (8 men and 21 women) to the passive control group. All participants gave informed consent to participate. Table 1 provides a description of the two groups and shows the sociodemographic data for each group. In both groups, women outnumbered men. Additional sociodemographic information can be found in the Supplementary Material–Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the experimental and control groups.

| Variables | Total sample (N = 52) | Experimental group (N = 30) | Control group (N = 22) | Intergroup tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 69.90 (5.45) | 70.10 (5.25) | 69.64 (5.83) | |

| Range | 60 − 83 | 60 − 83 | 60–80 | F(1,50)=.23; p=.637 |

| 60–65, N (%) | 8 (15.4 %) | 3 (10.0 %) | 5 (22.7 %) | |

| 65–70, N (%) | 17 (32.7 %) | 10 (33.3 %) | 7 (31.8 %) | |

| 70–75, N (%) | 14 (26.9 %) | 10 (33.3 %) | 4 (18.2 %) | |

| 75–80, N (%) | 11 (21.2 %) | 6 (20 %) | 5 (22.7 %) | |

| 80–85, N (%) | 2 (3.8 %) | 1 (3.3 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||

| Male | 17 (32.7 %) | 9 (30.0 %) | 8 (36.4 %) | χ2 (1)=.23; p=.629 |

| Female | 35 (67.3 %) | 21 (70.0 %) | 14 (63.6 %) | |

| Education level, N (%) | ||||

| 5 Years | 6 (11.5 %) | 5 (16.7 %) | 1 (4.5%) | χ2 (3)=7.85; p=.049 |

| 6–8 Years | 7 (13.5 %) | 2 (6.7 %) | 5 (22.7%) | |

| 9–13 Years | 22 (42.3 %) | 10 (33.3 %) | 12 (54.5%) | |

| ≥14 Years | 17 (32.7 %) | 13 (43.3 %) | 4 (18.2%) | |

| Moca, M (SD) | 23.75 (2.30) | 24.40 (2.30) | 22.85 (2.03) | F(1,50)=6.36; p=.015 |

Outcome measures

Verbal memory

To assess verbal memory the Italian version of the Prose Memory Test (PM) [34], also known as the Babcock Memory Test, was used. The Prose Memory Test is designed to assess memory function in terms of recall of logically organized verbal information. The total score is the mean of the two (immediate and delayed) correct recall scores (% of correct responses). Parallel versions of the Prose Memory Test were used for the assessment.

Autobiographical memory

The Autobiographical Memory Questionnaire (in Italian, ‘AMA Accertamento della Memoria negli adulti’) [35] measures AM by asking participants to retrieve memories about 45 personal events, belonging to three different periods (childhood, youth and the last 3 years, but not the last three months) and to report their vividness, using a 6-point Likert scale (‘1 = I can’t remember this event; 2 = I know it happens but I have no images; 3 = my memory for this event is dim and vague; 4 = my memory for this event is moderately vivid; 5 = my memory for this event is much vivid; 6 = my memory is perfectly vivid’).

Psychological well-being

The Ben-SCC questionnaire (in Italian: ‘BEN-SSC Ben-essere Psicologico’) [35] was used to assess the psychological well-being in middle age and older adults. The questionnaire is inspired by the eudemonic concept of psychological well-being, proposed by Carol Ryff [36]. The questionnaire measures personal satisfaction (in Italian: Ben-SP), coping strategies (in Italian: Ben-SC), and emotion regulation skills or emotional competences (in Italian: Ben-CE). Participants are asked to rate their agreement with each of the 37 items using on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (not at all) and 4 (yes/often). The total score is calculated as the sum of the scores for all items (maximum of 148).

Life satisfaction

The Life Satisfaction Index – version A (LSI-A) [37], Italian adaptation in Franchignoni et al. [38] was used to measure global judgments of satisfaction with one’s life. The scale consists of 20 attitude items, 12 items are positively formulated and 8 items are negatively formulated. Scores range from 0 (extremely poor life satisfaction) to 40 (excellent life satisfaction).

Loneliness

The UCLA Loneliness Scale [39], Italian adaptation in Boffo et al. [40] was used to measure one’s subjective feelings of loneliness. The scale consists of 20 items using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Scores range from 20 (not lonely at all) to 80 (extremely lonely).

Study design

To evaluate the effects of the intervention, the quasi-experimental design with the experimental and control group included a pre-test and a post-test measured at the end of the intervention. The experimental group received 1.5 h of reminiscence training per week for 10 weeks. Participants in the control group received no intervention and were asked to continue with their daily routine. Participants in the control group were placed on a waiting list for the treatment. Besides, a 6-month follow-up was conducted only in the experimental group. The study was conducted in 2023. Full written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Florence and registered with the Italian Clinical Trials Registry (Prot. n. 0025815 − 06/02/2023).

The ‘Ricordando-MI’ – ‘Remember-ME’ intervention

In the study we implemented the Italian version of the structured group-based reminiscence intervention, based on the program originally developed by Meléndez Moral et al. [30] and already applied to sample of healthy older adults [29,31]. In the program, participants attended 10 sessions of approximately 90–120 min each. To ensure that all participants were involved in the group discussions, the sessions were conducted in 4 small groups of 7–8 participants. All groups completed the sessions within a 10-week period and were conducted by the same psychologist, who facilitated the group discussions and explained all activities. All sessions were scheduled in the morning to control for any confounding effects related to the time-of-day effects on individuals attending the reminiscence group. All the sections had the same structure: 10 min of progressive muscle relaxation, discussion of homework, group activities and discussion around a central theme, feedback on the session, homework assignment.

The main objective of the first session was to inform the participants about the importance of active aging and well-being in life, and to explain the concept of reminiscence, the procedure that would be used and the importance of homework to reflect on past events and to become more aware of the positive effect of positive memories on one’s mood. In subsequent sessions, the psychologist presented the day’s theme, followed by various reminiscence activities. Based on the guidelines reported in Viguer et al. [31], the main topics used to evoke positive memories were: important life events throughout the life cycle; friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships; important dates such as anniversaries, birthdays, and others; traditional celebrations; movies, theater and advertisements; jobs performed; typical childhood games; grandmothers’ objects and furniture; and music. The materials (i.e. pictures, videos and objects) used in the reminiscence program were provided and shared by group members and they were related to their personal and socio-cultural contexts. Recent studies on reminiscence-based digital story-telling [41,42] and the use of augmented and virtual reality to support storytelling [43,44] have highlighted the importance of using personalized and emotionally relevant elements (e.g. personal photos), to enhance participants’ emotional and cognitive engagement (for similar findings with Alzheimer’s disease patients, see 45).

In the reminiscence program the materials were used to stimulate recall and group discussion on memories of important events in childhood, youth, and adult life and to evoke positive feelings and emotions that people associated with major life events. Activities and group discussions were conducted to encourage participants to share their experiences, feelings and emotions related to past events. Nearly all sessions were designed to facilitate the integration of past and present, and to provide a sense of meaning, integrity and purpose. Each session ended with a brief end-of-session evaluation. All participants had the opportunity to express their emerging feelings and emotions that occurred during the group discussions and to evaluate the organizational aspects of the session. Simple homework tasks were assigned at the end of each session to prepare the following session.

Data analyses

As all participants were free to choose whether to participate either in the experimental or the control group, homogeneity analysis was performed to avoid the selection bias, and to confirm that the groups did not differ at baseline. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed as preliminary analysis to detect any significant differences between the two groups in demographic characteristics and outcome measures prior to the intervention.

To analyze the effects of the intervention, a 2 × 2 mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Group (experimental and control) and Time (pre and post-test) as independent variables was carried out. When the interaction term resulted significant, Cohen d within group estimation was reported. Analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package. As additional analysis, a repeated measure ANOVA, comparing scores at pre-test, post-test and follow-up was carried out on the experimental group.

Results

Preliminary analyses

At baseline (pre-test), the experimental and control groups were homogeneous in relation to gender (χ2 (1) = 0.23; p = .629), age (F(1,50) = 0.23; p = .637), and educational level (χ2 (3) = 7.85; p = .049). A significant difference between the two groups was found in global cognitive functioning (F = 6.36; p = .015), as the control group reported a lower score at MOCA (M = 22.85; SD = 2.03) compared to the experimental group (M = 24.40; SD = 2.30). There were no significant differences in outcome measures (i.e. verbal memory, autobiographical memory, psychological well-being, life satisfaction and loneliness) (Supplementary Material–Table 2). Overall, the experimental and control groups can be considered quite homogeneous.

Main analyses: pre-post test

The statistics of the analyses of all variables of interest are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means (and standard deviations) for the outcome variables and results from the group × time factorial ANOVA.

| Experimental group (p = 30) |

Control group (n = 22) |

F(1,50) group |

F(1,50) time |

F(1,50) group × time |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |||

| PM | 51.85 (12.93) | 57.44 (12.81) | 46.83 (10.87) | 46.59 (11.07) | 6.77 p=.012 | 3.14 p=.082 |

3.74 p=.059 |

| AMA – Total score | 147.10 (31.75) | 162.7 (30.11) | 140.18 (30.22) | 139.5 (31.05) | 3.34 p=.074 | 8.11 p=.006 | 9.65 p=.003 |

| AMA-I | 44.6 (11.68) | 50.47 (11.92) | 42.14 (15.28) | 44.55 (14.05) | 1.45 p=.234 | 12.20 p=.001 | 2.13 p=.151 |

| AMA-II | 50.17 (12.22) | 57.13 (10.74) | 47.05 (11.97) | 47.32 (12.43) | 4.72 p=.035 | 6.21 p=.016 | 5.31 p=.025 |

| AMA-III | 52.33 (13.45) | 55.1 (12.06) | 51 (10.34) | 47.64 (12.58) | 1.88 p=.176 | 0.06 p=.812 | 6.01 p=.018 |

| BEN-SCC -total score | 110.37 (12.66) | 111.87 (14.27) | 109.82 (12.14) | 109.73 (15.11) | 0.15 p=.700 | 0.20 p=.656 | 0.26 p=.615 |

| BEN-SP | 32.03 (5.03) | 32.64 (5.71) | 32.64 (5.02) | 31.86 (6.16) | 0.00 p=.963 | 0.03 p=.859 | 1.34 p=.252 |

| BEN-SC | 26.7 (3.79) | 27.03 (3.94) | 25.86 (3.75) | 26.05 (4.48) | 0.79 p=.376 | 0.33 p=.571 | 0.03 p=.867 |

| BEN-CE | 30.73 (4.04) | 30.27 (3.86) | 30.27 (3.86) | 30.5 (4.29) | 0.51 p=.479 | 1.01 p=.321 | 0.28 p=.599 |

| LSI-A | 28.17 (6.55) | 30.33 (7.62) | 27.09 (7.92) | 26.23 (8.26) | 1.61 p=.210 | 1.35 p=.250 | 7.31 p=.009 |

| UCLA | 42.7 (7.15) | 41.27 (7.65) | 43.82 (6.46) | 45.50 (7.58) | 1.86 p=.178 | 0.05 p=.823 | 7.98 p=.007 |

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

PM: Prose memory or verbal memory; AMA: Vividness of autobiographical memory; AMA-I: vividness of memories related to childhood; AMA-II: vividness of memories related to youth; AMA-III: Vividness of memories related a recent period; BEN-SCC: Psychological well-being; BEN-SP: personal satisfaction; BEN-SC: coping strategies; BEN-CE: emotional competences; LSI-A: Life satisfaction Index; UCLA: Loneliness.

Verbal memory

Only the main effect of Group was statistically significant (F(1,50) = 6.77; p = .012; ηp2 = 0.12), as the experimental group performed better than the control group at the verbal memory task. The main effect of Time (F(1,50) = 3.14; p = .082; ηp2 = 0.06) and the interaction were not statistically significant (F(1,50) = 3.74; p = .059; ηp2= 0.07), although, as shown by the moderate effect size of the interaction and illustrated in Figure 1, we can observe a different trend in the two groups, with an increase in the experimental group and stability in the control group.

Figure 1.

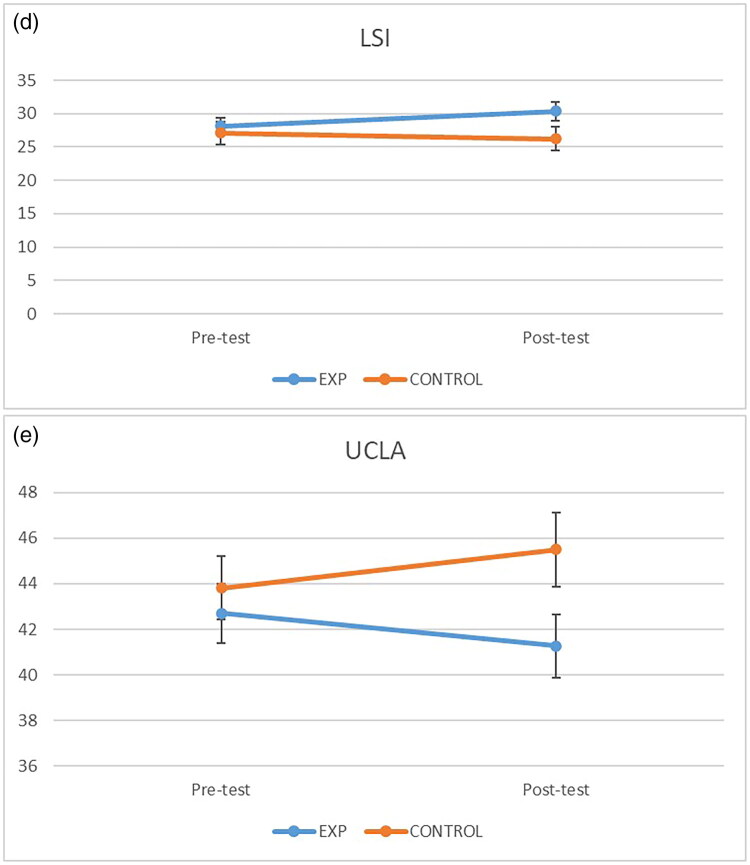

Mean scores (and standard errors) for the outcome variables for experimental and control group at pre-test and post-test. (a) PM: Prose memory or verbal memory; (b) AMA: Vividness of autobiographical memory; (c) BEN-SCC: Psychological well-being; (d) LSI-A: Life satisfaction Index; (e) UCLA: Loneliness. The y axis for BEN-SCC and UCLA do not start from zero.

Autobiographical memory

The main effect of Time was significant (F(1,50) = 8.11; p = .006; ηp2 = 0.14), whereas the main effect of Group was not significant (F(1,50) = 3.34, p = .074; ηp2 = 0.06). The interaction effect (Time × Group) was significant (F(1,50) = 9.65, p = .003; ηp2 = 0.16). As we can see from Table 2 and Figure 1, the experimental group reported an increase in the global scores of vividness of autobiographical memories from pre-test to post-test (Cohen d = 0.73) whereas in the control group they showed a stability across time (Cohen d = 0.04). A significant Time × Group effect was also found when analyses were carried out on vividness of autobiographical memories for different periods: overall, the experimental group showed an increase across time in vividness of memories related to youth (Cohen d = 0.71) and memories for a recent life period (Cohen d = 0.28), whereas the control group showed a general stability for memories related to youth (Cohen d = 0.01) and a decrease in vividness of memories related to a recent period (Cohen d = 0.47).

Psychological well-being

The main effects of Time (F(1,50) = 0.20; p = .656) and Group (F(1,50) = 0.15; p = .700) were not significant. The interaction effect (Time x Group) was not significant (F(1,50) = 0.26; p = .615) (Figure 1).

Life satisfaction

The main effects of Time (F(1,50) = 1.35; p = .250; ηp2 = 0.03) and Group (F(1,50) = 1.61; p = .210; ηp2 = 0.03) were not significant, whereas the interaction effect (Time × Group) was significant (F(1,50) = 7.31; p = .009; ηp2 = 0.13). As reported by the descriptive data in Table 2, the level of life satisfaction increased across time in the experimental group (Cohen d = 0.52), whereas it remained stable in the control group (Cohen d = 0.20) (Figure 1).

Loneliness

The main effects of Time (F(1,50) = 0.05; p = .823) and Group (F(1,50) = 1.86; p = .178; ηp2 = 0.04) were not significant, whereas the interaction effect (Time x Group) was significant (F(1,50 = 7.98; p = .007; ηp2 = 0.14). As we can see from the descriptive data (Table 2), the level of loneliness is likely to decrease in the experimental group (Cohen d = 0.32), whereas in the control group it is likely to increase across time (Cohen d = 0.37) (Figure 1).

Additional analyses

A repeated measure ANOVA, comparing scores at pre-test, post-test and follow-up was carried out on the experimental group. Only 1 out of the 30 participants did not perform the follow-up. Results are shown in Table 3 and pairwise test are reported in the Supplementary Material–Table 3.

Table 3.

Means (and standard deviation) for the outcome variables and results from Repeated-measures ANOVA on the experimental group.

| Variable | Experimental group (p = 29) |

F (2,28) time |

Sign. | η p 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test M (SD) |

Post-test M (SD) |

Follow-up M (SD) |

||||

| PM | 51.85 (13.16) | 57.49 (13.04) | 59.88 (10.38) | 6.42 | 0.003 | 0.19 |

| AMA – total score | 147.59 (32.20) | 164.21 (29.47) | 163.66 (33.13) | 12.48 | 0.001 | 0.31 |

| AMA-I | 44.59 (11.89) | 50.72 (12.04) | 51.66 (12.89) | 10.46 | 0.001 | 0.27 |

| AMA-II | 50.41 (12.36) | 57.66 (10.54) | 56.79 (12.54) | 10.14 | 0.001 | 0.27 |

| AMA-III | 52.59 (13.61) | 55.83 (11.58) | 55.21 (11.71) | 2.11 | 0.131 | 0.07 |

| BEN-SCC – total score | 111.07 (12.27) | 112.45 (14.16) | 115.97 (14.95) | 3.84 | 0.027 | 0.12 |

| BEN-SP | 32.21 (5.03) | 32.69 (5.79) | 33.72 (5.95) | 2.24 | 0.116 | 0.07 |

| BEN-SC | 26.93 (3.63) | 27.24 (3.84) | 28.28 (4.13) | 3.01 | 0.057 | 0.10 |

| BEN-CE | 30.90 (4.01) | 31.66 (3.59) | 32.34 (3.83) | 3.30 | 0.044 | 0.11 |

| LSI-A | 28.21 (6.66) | 30.38 (7.75) | 30.17 (7.30) | 5.24 | 0.008 | 0.16 |

| UCLA | 42.59 (7.25) | 41.14 (7.50) | 40.34 (6.81) | 4.16 | 0.021 | 0.13 |

*F test obtained using Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity assumption violation.

PM: Prose memory or verbal memory; AMA: Vividness of autobiographical memory; AMA-I: vividness of memories related to childhood; AMA-II: vividness of memories related to youth; AMA-III: Vividness of memories related a recent period; BEN-SCC: Psychological well-being; BEN-SP: personal satisfaction; BEN-SC: coping strategies; BEN-CE: emotional competences

LSI-A: Life Satisfaction Index; UCLA: Loneliness.

Verbal memory

The effect of Time was significant F(2,28) = 6.42; p = .003; ηp2 = 0.19). Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference between pre-test and post-test (MD = −5.65; p = .007) and pre-test and follow-up (MD = −8.03; p = .002), as verbal memory scores increased from pre-test to post-test and they were maintained at follow-up.

Autobiographical memory

As for AM, the results showed a significant effect of Time on the total score of vividness of autobiographical memories (F(2,28) = 12.48; p<.001; ηp2 = 0.31), and on the sub-scores of vividness for childhood memories (F(2,28) = 10.46; p<.001; ηp2 = 0.27) and memories related to youth (F(2,28) = 10.14; p<.001; ηp2 = 0.27). Pairwise comparison for the vividness of all autobiographical memories showed a significant difference between pre-test and post-test (MD = −16.62; p<.001) and between pre-test and follow-up (MD = −16.07; p = .001). Pairwise comparison for vividness of childhood memories showed a significant difference between pre-test and post-test (MD = −6.14; p<.001) and between pre-test and follow-up (MD = −7.07; p<.001). The pairwise comparison for vividness of memories related to youth shows a significant difference between pre-test and post-test (MD = −7.24; p<.001) and between pre-test and follow-up (MD = −6.38; p = .002). Overall, the levels of vividness of autobiographical memories, and especially of childhood memories and memories of youth, increased significantly from pre-test to post test and they were maintained at follow-up.

Psychological well-being

Results for psychological well-being indicate a significant effect of Time on the total score of psychological well-being (F(2,28) = 3.84; p = .027; ηp2 = 0.12), and the score of the subscale of Emotional Competence (F(2,28) = 3.30; p = .044; ηp2 = 0.11). Specifically, the pairwise comparison revealed a significant increase in psychological wellbeing (total score) from pre-test to follow-up (MD = −4.897; p = .012), and a similar pattern was observed for emotional competence (MD = −1.45; p = .012).

Life satisfaction

The effect of Time was significant (F(2,28) = 5.24; p = .008; ηp2 = 0.16). Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference between pre-test and post-test (MD = −2.17; p= .01) and between pre-test and follow-up (MD = −1.97; p = .019), as the levels of life satisfaction increased from pre-test to post-test and they were maintained at follow-up.

Loneliness

The effect of Time was significant (F(2,28) = 4.16; p = .021; ηp2 = 0.13). A pairwise comparison for loneliness shows a significant difference between pre-test and follow-up (MD = 2.24; p = .009) but not between pre-test and post-test (MD = 1.45; p = .073). Specifically, the level of loneliness decreased significantly from pre-test to follow-up (Supplementary Material Table 3).

Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the effects of a group-based structured reminiscence intervention on both cognitive and psychological dimensions. Our results showed that this intervention improved ratings of vividness of autobiographical memories, especially those related to childhood and youth, along with a significant increase in life satisfaction and a significant decrease in feelings of loneliness.

Effects on cognitive dimensions

In the present study we assessed the effects of the intervention on AM, and specifically on the subjective quality of vividness of AMs, and verbal memory. As mentioned above, this program has been effective in improving episodic AM in patients with aMCI and AD [30]. Here we could find, in a sample of cognitively intact older adults, a significant improvement in the subjective quality of AM, with personal memories from different time periods, and especially from childhood and youth, being experienced as more clear and vivid after the intervention and this effect was maintained at follow-up, whereas no significant changes were found in the control group.

Most scholars agree that visual imagery plays a crucial role in the retrieval of AMs [46–50], and vividness is one of the most relevant phenomenological properties of AMs, which is found to be associated also with differences in wellbeing and psychological distress [11,51]. For examples, distress levels have been linked to the retrieval of memories that are less vivid, detailed and coherent [11]. In contrast, recalling phenomenologically rich AMs are found to contribute to enhance one’s sense of overall well-being and life satisfaction [12,51].

Although future studies are needed to replicate our findings and to extend the investigation to other relevant phenomenological properties of AMs (i.e. richness of details, coherence), the pattern of results suggest that the structured group-based reminiscence intervention we employed, being focused on the recall and sharing of past events, emergence of positive feelings and maintenance and building of self-confidence through the positive memories, may enhance the way the personal past is retrieved, leading to a richer subjective experience.

In the present study we also assessed the effects of the program on verbal memory (immediate and delayed recall). Although the difference in the patterns between experimental and control group was not statistically significant, the effect size suggests a potential difference, with only the experimental group showing an improvement at post-test. Additionally, a significant change over time was found in the experimental group in the pairwise analysis, (which did not include the control group): verbal memory scores in the experimental group increased from pre-test to post-test, and were maintained at follow-up. Due to the limited statistical power provided by the available sample size, these findings should be interpreted with much caution and warrant further investigation.

Effects on psychological aspects

Our study found a significant positive effect on life satisfaction that increased from pre-test to post-test in the experimental group, as compared to the control group where life satisfaction remained stable. This result is in line with the large body of evidence identifying a positive effect of reminiscence-based interventions on life satisfaction (see Tam et al. [20] for a review) and with the results obtained in a previous study on the same reminiscence program [31]. Furthermore, our study found a positive result of the intervention on loneliness, which is consistent with some studies that found a positive effect on loneliness after a reminiscence-based intervention combined with physical exercise [52].

As suggested by other scholars [20] it is likely that the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of reminiscence-based intervention are complex and multifactorial, and it still remains unclear the role and the relative impact of different aspects of the interventions, such as recalling personal events, social engagement and also sensory stimulation, in the final outcomes of the intervention.

As showed by Satorres et al. [29] the group-based reminiscence program we employed also produced an increase in the prosocial functions of reminiscence. This reminiscence intervention stimulated older people to share positive memories, which enhanced social connectedness, interpersonal communication, intimate relationships, sense of support and belonging. This program could also help making with new friends with whom they can share the same experience. In that sense, the increase in socialization may also have contributed to improve mental health and to decrease the subjective experience of loneliness.

As for psychological wellbeing, in contrast with other studies, showing a remarkable effects of reminiscence-based interventions on depressive symptoms and psychological well-being [30,53–56], and with similar results obtained in a previous study on this reminiscence program [31] in the present work we did not find any improvements in the experimental group from pre-test to post-test. However, interestingly, when we compared the pre-test with the follow-up, we could find a significant increase in both the total score of well-being questionnaire and in its subscale on emotional competencies. Although this result needs to be further investigated, one explanation might be advanced. Specifically, one might argue that his pattern of results may be due to a sleeping effect, that is participants may have needed some time to assimilate the beneficial effects of retrieving and sharing positive autobiographical memories.

Some limitations of the present study should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, our study has a small sample size (N = 52), and also a self-selection bias, due to our recruitment procedure, which limits the generalizability and external validity of the study. The small sample size also limited the possibility of conducting more complex models where the interactional effects were controlled for baseline variables, such as educational level or MOCA scores. Future studies should include a higher number of participants from more diverse backgrounds to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Second, no scale was administered to measure depressive symptomatology and other comorbidities that are common in older people. Third, to evaluate the effects of the program, we used a pre-test vs. post-test design, and the follow-up was conducted only in the experimental group, limiting the long-term comparison between the two groups. Extending the follow-up period to several months post-intervention for both groups could provide valuable information on the durability of the intervention’s effects and its potential long-term benefits.

Conclusion

This pilot study has provided some promising evidence on the effectiveness of the Italian version of this reminiscence-based intervention on Italian community-dwelling older adults without cognitive impairment. Structured group reminiscence may be an effective method for promoting mental health in older adults, counteracting the detrimental effects of loneliness. Our findings suggest that public health efforts aimed at enhancing well-being may serve to promote mental and cognitive health as a contribution to positive, healthy and successful aging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank professor Juan Carlos Meléndez Moral for sharing the reminiscence based program. We thank the associations Anteas Provinciale Firenze-Prato, Auser Figline ODV, A.V.O. Figline e Incisa Valdarno, Il Giardino, and the trade unions FNP Cisl Pensionati Firenze Prato and SPI CGIL Lega intercomunale Figline e Incisa Valdarno, Reggello, Rignano for their commitment to the project.

Funding Statement

The research was supported by FNP CISL Pensionati, grant ‘Promoting active aging and intergenerational relationships’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lazzari C, Rabottini M.. COVID-19, loneliness, social isolation and risk of dementia in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the relevant literature. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2022;26(2):196–207. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1959616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van As BAL, Imbimbo E, Franceschi A, et al. The longitudinal association between loneliness and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2022;34(7):657–669. doi: 10.1017/S1041610221000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M.. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiorri C, Vannucci M.. The subjective experience of autobiographical remembering: conceptual and methodological advances and challenges. J Intell. 2024;12(2):21. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence12020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg DL, Rubin DC.. The neuropsychology of autobiographical memory. Cortex. 2003;39(4–5):687–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comblain C, D’Argembeau A, Van der Linden M.. Phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memories for emotional and neutral events in older and younger adults. Exp Aging Res. 2005;31(2):173–189. doi: 10.1080/03610730590915010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin DC, Berntsen D.. The frequency of voluntary and involuntary autobiographical memories across the life span. Mem Cognit. 2009;37(5):679–688. doi: 10.3758/37.5.679/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vannucci M, Chiorri C, Favilli L.. Web-based assessment of the phenomenology of autobiographical memories in young and older adults. Brain Sci. 2021;11(5):660. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11050660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine B, Svoboda E, Hay JF, et al. Aging and autobiographical memory: dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(4):677–689. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piolino P, Desgranges B, Clarys D, et al. Autobiographical memory, autonoetic consciousness, and self-perspective in aging. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(3):510–525. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.510/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luchetti M, Sutin AR.. Measuring the phenomenology of autobiographical memory: a short form of the Memory Experiences Questionnaire. Memory. 2016;24(5):592–602. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2015.1031679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Aschwanden D, et al. Sense of purpose in life, cognitive function, and the phenomenology of autobiographical memory. Memory. 2021;29(9):1126–1135. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2021.1966472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rottenberg J, Joormann J, Brozovich F, et al. Emotional intensity of idiographic sad memories in depression predicts symptom levels 1 year later. Emotion. 2005;5(2):238–242. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bluck S, Levine LJ.. Reminiscence as autobiographical memory: a catalyst for reminiscence theory development. Age Soc. 1998;18(2):185–208. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X98006862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demiray B, Mischler M, Martin M.. Reminiscence in everyday conversations: a naturalistic observation study of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(5):745–755. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappeliez P, O’Rourke N.. Empirical validation of a model of reminiscence and in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(4):P237–244. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.P237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Rourke N, Cappeliez P, Claxton A.. Functions of reminiscence and the psychological well-being of young-old and older adults over time. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(2):272–281. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Rourke N, Bachner YG, Cappeliez P, et al. Reminiscence functions and the health of Israeli Holocaust survivors as compared to other older Israelis and older Canadians. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(4):335–346. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.938607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shropshire M. Reminiscence intervention for community-dwelling older adults without dementia: a literature review. Br J Community Nurs. 2020;25(1):40–44. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2020.25.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam W, Poon SN, Mahendran R, et al. The effectiveness of reminiscence-based intervention on improving psychological well-being in cognitively intact older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;114:103847. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer E, Webster JD.. Reminiscence and mental health: a review of recent progress in theory, research and interventions. Age Soc. 2010;30(4):697–721. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09990328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotelli M, Manenti R, Zanetti O.. Reminiscence therapy in dementia: a review. Maturitas. 2012;72(3):203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Philbin L, Woods B, Farrell EM, et al. Reminiscence therapy for dementia: an abridged Cochrane systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18(9):715–727. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2018.1509709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin DC, Johnson DM.. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indic Res. 1978;5(1–4):475–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00352944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leahy F, Ridout N, Holland C.. Memory flexibility training for autobiographical memory as an intervention for maintaining social and mental well-being in older adults. Memory. 2018;26(9):1310–1322. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2018.1464582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sok SR. Effects of individual reminiscence therapy for older women living alone. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(4):517–524. doi: 10.1111/inr.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen AP, Doyle C, Roche RA.. The impact of reminiscence on autobiographical memory, cognition and psychological well-being in healthy older adults. Eur J Psychol. 2020;16(2):317–330. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i2.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Medeiros K, Mosby A, Hanley KB, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a writing workshop intervention to improve autobiographical memory and well‐being in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(8):803–811. doi: 10.1002/gps.2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satorres E, Delhom I, Meléndez JC.. Effects of a simple reminiscence intervention program on the reminiscence functions in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;33(6):557–566. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meléndez Moral JC, Fortuna Terrero FB, Sales Galan A, et al. Effect of integrative reminiscence therapy on depression, well-being, integrity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in older adults. J Posit Psychol. 2015;10(3):240–247. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.936968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viguer P, Satorres E, Fortuna FB, et al. A follow-up study of a reminiscence intervention and its effects on depressed mood, life satisfaction, and well-being in the elderly. J Psychol. 2017;151(8):789–803. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2017.1393379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conti S, Bonazzi S, Laiacona M, et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Italian version: regression based norms and equivalent scores. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(2):209–214. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Renzi E, Faglioni P, Ruggerini C. ; 1977. Studies of verbal memory in clinical application for the diagnosis of amnesia. Archivio di Psicologia, Neurologia e Psichiatria, 38, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Beni R, Borella E, Carretti B, et al. BAC. Portfolio per la valutazione del benessere e delle abilità cognitive nell’età adulta e avanzata. Firenze: Giunti OS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neugarten BL, Havighurst RJ, Tobin SS.. The measurement of life satisfaction. J Gerontol. 1961;16(2):134–143. doi: 10.1093/geronj/16.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franchignoni F, Tesio L, Ottonello M, et al. Life Satisfaction Index: italian version and validation of a short form. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78(6):509–515. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boffo M, Mannarini S, Munari C.. Exploratory structure equation modeling of the UCLA loneliness scale: a contribution to the Italian adaptation. TPM Appl Psychol. 2012;19(4):345–363. doi: 10.4473/TPM19.4.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu L, Fields NL, Highfill MC, et al. Remembering the past with today’s technology: a scoping review of reminiscence-based digital storytelling with older adults. Behav Sci. 2023;13(12):998. doi: 10.3390/bs13120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu L, Li S, Yan R, et al. Effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological outcome among older adults without obvious cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiat. 2023;14:1139700. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1139700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Feng L, Liang C, et al. Exploring the opportunities of AR for enriching storytelling with family photos between grandparents and grandchildren. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wear Ubiquit Technol. 2023;7(3):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei X, Gu Y, Kuang E, et al. Bridging the generational gap: exploring how virtual reality supports remote communication between grandparents and grandchildren. Vol. 44. In: Schmidt A, Väänänen K, Goyal T, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2023. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen KW, Salgado S, Daustrand M, et al. Using nostalgia films to stimulate spontaneous autobiographical remembering in Alzheimer’s disease. J Appl Res Memory Cognit. 2021;10(3):400–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conway MA. Associations between autobiographical memories and concepts. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cognit. 1990;16(5):799–812. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.16.5.799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El Haj M, Delerue C, Omigie D, et al. Autobiographical recall triggers visual exploration. JEMR. 2014;7(5):1–7. doi: 10.16910/jemr.7.5.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El Haj M, Nandrino JL, Antoine P, et al. Eye movement during retrieval of emotional autobiographical memories. Acta Psychol. 2017;174:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubin DC. A basic-systems approach to autobiographical memory. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(2):79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00339.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vannucci M, Pelagatti C, Chiorri C, et al. Visual object imagery and autobiographical memory: object imagers are better at remembering their personal past. Memory. 2016;24(4):455–470. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2015.1018277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latorre JM, Ricarte JJ, Serrano JP, et al. Performance in autobiographical memory of older adults with depression symptoms. Appl Cognit Psychol. 2013;27(2):167–172. doi: 10.1002/acp.2891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yujia REN, Rong TANG, Hua SUN, et al. Intervention effect of group reminiscence therapy in combination with physical exercise in improving spiritual well-being of the elderly. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50(3):531–539. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i3.5594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bharathi AR. Evaluate the effectiveness of reminiscence therapy. JPRI. 2021;33(46A):447–452. doi: 10.9734/JPRI/2021/v33i46A32887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, et al. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291–300. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai CK, Igarashi A, Yu CT, et al. Does life story work improve psychosocial well-being for older adults in the community? A quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0797-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preschl B, Maercker A, Wagner B, et al. Life-review therapy with computer supplements for depression in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(8):964–974. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.702726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.