Abstract

Objective

To explore the impact of graded nursing interventions based on a quantitative risk assessment system on psychophysiological stress responses in patients undergoing resection for primary liver cancer.

Methods

A total of 80 patients who underwent liver cancer surgery in the hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery department of a tertiary Grade A hospital between January 2023 and December 2023 were randomly divided into an observation group and a control group, with 40 patients in each, using a random number table method. The control group received routine nursing care, whereas the observation group received a graded nursing plan based on a quantitative assessment system.

Results

Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in Psychological Stress Response Questionnaire (SRQ) scores between the two groups. Following the intervention, SRQ scores decreased in both groups, with significantly lower scores in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.001). Similarly, no statistically significant differences in the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) scores were observed between the groups before the intervention. After the intervention, both groups showed lower HAMA and HAMD scores than pre-intervention levels, with the observation group exhibiting significantly lower scores than the control group (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Graded nursing interventions based on quantitative assessment can effectively reduce postoperative psychological stress and negative emotional responses in patients undergoing surgery for primary liver cancer, thereby promoting recovery.

Trial registration

ISRCTN81587743, Registration date: 25/04/2025.

Clinical trial number

ISRCTN81587743.

Keywords: Quantitative assessment, Graded nursing, Liver cancer, Psychological stress response

Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the malignancies with high incidence and mortality rates worldwide. According to 2022 data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the incidence of liver cancer in China ranks fourth among malignant tumours, with mortality ranking third, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 20% [1]. At present, surgical resection remains the preferred method for achieving long-term survival in patients with primary liver cancer, with a 5-year survival rate of up to 56.9% [2]. However, surgery, as a substantial physiological and psychological stressor, often induces perioperative negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, which may further lead to endocrine disorders, suppression of immune function and delayed postoperative recovery [3]. Studies have shown that approximately 45% of patients undergoing liver cancer resection experience moderate to severe anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Scale [HAMA] ≥ 14 points) postoperatively, and 30% exhibit depressive symptoms (Hamilton Depression Scale [HAMD] ≥ 17 points). Moreover, psychological stress responses are substantially associated with prolonged hospital stays and an increased risk of complications [4, 5].

Although the concept of enhanced recovery following surgery (ERAS) has been gradually promoted, traditional nursing models still rely on subjective experience when assessing patients’ psychological states. This lack of quantitative tools results in insufficiently targeted interventions and limited effectiveness in alleviating psychological stress [6]. The graded nursing model based on quantitative risk assessment can integrate objective indicators (e.g. Child–Pugh score and HAMA/HAMD scales) to conduct multidimensional risk assessments and dynamically allocate nursing resources (e.g. N0–N3 nurse levels) according to risk levels, thereby enabling precise interventions and offering new perspectives for optimising perioperative management [7].

In recent years, multiple studies have demonstrated that quantitative-based graded nursing can substantially reduce postoperative anxiety levels and shorten hospital stays in patients with colorectal and breast cancer [8, 9]. However, in the field of liver cancer, existing research primarily focuses on physiological indicators (e.g. liver function and complications), and there remains a lack of evidence-based systematic assessment and stratified intervention strategies for psychological stress [10]. In addition, inconsistent risk grading standards and inefficient allocation of nursing resources have hindered the widespread clinical application of this model [11].

Given this context, the present study aims to explore the impact of quantitative graded nursing interventions on psychological stress and postoperative recovery in patients undergoing resection for primary liver cancer by constructing a grading assessment system centred on Child–Pugh scores and HAMA/HAMD scales, combined with dynamic nursing resource allocation. The findings of this study may offer a standardised approach to perioperative nursing in liver cancer and support the practical implementation of an integrated ‘physiological–psychological’ management model.

Materials and methods

General information

This study is a prospective randomised controlled trial conducted in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines. A total of 80 hospitalised patients with liver cancer who met the inclusion criteria were selected from the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Department of a tertiary Grade A hospital in Ningbo between January 2023 and December 2023. The study was approved by the ethics committee, and all patients provided signed informed consent. The sample size was calculated based on previous literature [12], with an effect size d = 0.8, α = 0.05 (two-sided) and β = 0.2. The minimum required sample size of 34 cases per group was determined using G*Power 3.1 software. Considering a 20% dropout rate, 80 cases were finally included (40 cases per group).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meeting the surgical indications outlined in the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Liver Cancer (2022 Edition) (single tumour diameter ≤ 5 cm, no portal vein trunk tumour thrombus, Child–Pugh A/B grade) [13]; (2) aged 18–75 years; and (3) provided signed informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) severe cardiovascular disease (New York Heart Association class III–IV); (2) immune system disease or coagulation dysfunction (international normalised ratio > 1.5, platelet count < 50 × 10⁹/L); (3) malignant tumours in other locations; and (4) history of cognitive impairment or mental illness.

Random number sequences were generated using SPSS 26.0, stratified by Child–Pugh score (A/B grade), with a block size of 4 for each stratum. Sealed opaque envelopes were used to store allocation results, managed by an independent statistician. Following enrolment, research nurses assigned patients to groups according to the envelope instructions, dividing them into an observation group and a control group, each comprising 40 patients.

In the control group, there were 18 men and 22 women, aged 45–74 years (mean 58.21 ± 3.15 years). In the observation group, there were 19 men and 21 women, aged 44–76 years (mean 57.13 ± 2.91 years). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, pathological stage, lesion location or surgical method (P > 0.05), indicating baseline comparability.

Methods

Control group

The control group received routine nursing care as recommended by the Chinese Expert Consensus on Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (2021) [14], which included the following: (1) preoperative health education, in which nursing staff provided patients with knowledge about liver cancer through oral communication; (2) postoperative pain management (visual analogue scale score ≤ 3), involving close monitoring of patients’ pain, bowel movements and drainage tube conditions after surgery; and (3) early ambulation (within 24 h postoperatively), where patients were guided to begin moving early in order to actively prevent complications.

Observation group

In addition to the interventions provided to the control group, the observation group received a strategy based on quantitative assessment. The expert team and intervention team, each consisting of 10 members, jointly participated in the intervention process. During this revision process, the expert team included a chief physician, a head nurse and a clinical researcher with a doctoral degree, all of whom contributed to the project. With extensive nursing knowledge and practical experience gained from long-term work, this team is dedicated to optimising and implementing nursing models to meet clinical needs and improve service quality. The intervention team comprised one psychiatric nurse, one oncology nurse, one ERAS specialist nurse, two nutrition specialist nurses and two attending physicians. Within the team, the leader was an oncology nurse responsible for overseeing the research progress and facilitating collaboration and communication among team members. Two co-leaders, including two psychiatric nurses and one physician, were responsible for managing the grading of patient care.

Preoperative quality assessment

A targeted assessment of the condition of enrolled patients with liver cancer was conducted, including age, disease status and comorbidities. The Child–Pugh score [15] was used to assess liver function, the HAMA to evaluate anxiety levels and the HAMD to assess depressive states. Each dimension was assigned a score ranging from 1 to 3 points, and the total score was calculated as: Child–Pugh + HAMA + HAMD + comorbidity score. Treatment risk was categorised based on the comprehensive score as follows: low risk (< 9 points), medium risk (9–12 points) and high risk (> 12 points).

The assessment criteria were as follows: (1) age was scored as 1 point for ages 1–69, 2 points for ages 70–79 and 3 points for age ≥ 80; (2) personal condition, under standard conditions, was scored as 1 point for no bad habits and normal body type, 2 points for no bad habits but obesity and 3 points for obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption; (3) comorbidities referred to the presence of multiple diseases alongside the primary condition; (4) psychological state was evaluated using the HAMA [16] and HAMD [17] scores – if the patient exhibited fear (HAMA > 14), anxiety (HAMA > 14), or depression (HAMD ≥ 7), the scores were categorised as 1 point for HAMD 7–17 or HAMA 7–14, 2 points for HAMD 17–24 or HAMA 14–21 and 3 points for HAMD ≥ 24 or HAMA ≥ 21; and (5) the Child–Pugh score was recorded as 1 point for Grade A, 2 points for Grade B and 3 points for Grade C [18].

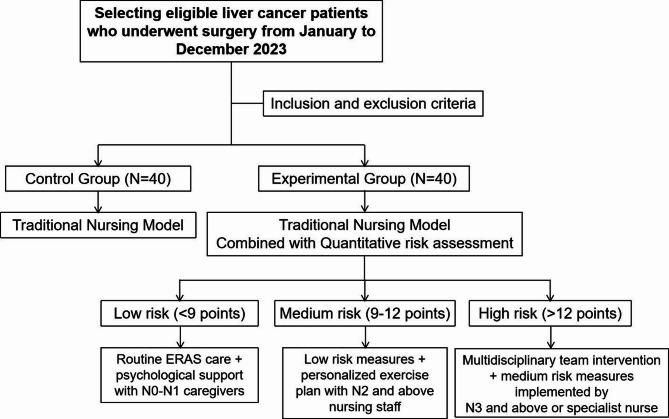

Stratified nursing plan

Based on the quantitative assessment results, clinical nursing staff from various departments were allocated appropriately, and stratified nursing measures were implemented (see Fig. 1). Patients under low-risk were assigned N0–N1 nursing staff to provide routine ERAS care plus psychological support (10 min of mindfulness training daily). Patients under medium-risk were assigned N2 or higher nursing staff to implement low-risk measures along with personalised exercise plans (bed activities starting 6 h postoperatively). Patients under high-risk were assigned N3 or higher nursing staff, team leaders or specialist nurses to implement medium-risk measures along with multidisciplinary team interventions, including joint daily rounds by psychiatric nurses and nutritionists [19, 20].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart

Specific nursing measures

Preoperative measures

The following preoperative interventions were tailored according to patient risk level. (1) Patients under low-risk received a preoperative assessment, including a detailed explanation of their overall condition, and were provided with comprehensive information about the surgery and perioperative care. (2) For patients under medium-risk, the responsible nurse conducted a preoperative check 1 day before surgery, taking into account the patient’s condition, educational level and other relevant factors to provide targeted guidance, help the patient form a correct understanding and foster a positive mindset towards the surgical process. (3) Patients under high-risk, in addition to receiving medium-risk care, were supported by a psychiatric nurse who used music therapy, narrative nursing, relaxation training and mindfulness therapy. An ERAS specialist nurse conducted a comprehensive assessment covering endurance, nutritional status, pain experience, ERAS knowledge and social support. The following measures were then implemented. (1) Personalised health education was provided through oral communication, looped videos in patient activity areas, brochure distribution and WeChat platform updates. (2) The teach-back method was used to guide patients in mastering preoperative and postoperative functional exercises, including lung function exercises (turning and back-patting techniques), tools for getting out of bed, coughing and expectoration methods and basic techniques for pain prevention and relief.

Postoperative measures

The following postoperative interventions were administered based on patient risk stratification. (1) Patients under low-risk underwent routine monitoring of vital signs and received standard post-hepatectomy care. (2) Patients under medium- and high-risk engaged in bed exercises and lung function training, which included three-step pursed-lip breathing, four-step effective coughing and five-step back-tapping techniques. A personalised out-of-bed exercise plan was developed as follows. (1) The first out-of-bed activity was guided by a specialist nurse. (2) Patients followed a three- to five-step process to get out of bed: bend the left leg, turn to the right side, support with the right elbow, use both hands for support and sit up at the bedside. The three-step rule was applied – lie in bed for 30 s, sit at the bedside for 30 s and stand for 30 s before walking. If the assessment was unsatisfactory (heart rate > 100 beats per minute, SpO₂ <90% or blood pressure < 100/60 mmHg), the activity was paused and a professional doctor evaluated the patient before continuing. (3) Early out-of-bed activity followed a weekly post-hepatectomy plan based on gradual progression, with monthly increases in exercise volume. The activity standards at 24, 48 and 72 h postoperatively were 10, 100 and 129 m, respectively. (4) To address psychological state, a psychiatric nurse, together with the responsible nurse, explained mindfulness-based stress reduction concepts and methods, guiding patients in breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation and emotional regulation.

Observation indicators

Assessments and data collection were conducted at two time points: before the implementation of the intervention and after the implementation of the intervention.

(1) Psychological Stress Response Questionnaire (SRQ): This was used to evaluate the psychological stress response of patients in both groups. The scale consists of three dimensions and 28 items, scored on a 5-point scale (0–4). The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.89, with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological stress response [21].

(2) Hamilton Depression Scale: Used to measure the depressive state of patients. The HAMD includes 17 items, with a total score range of 0–60. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.85, and higher scores indicate more severe depression [16].

(3) Hamilton Anxiety Scale: Used to measure the anxiety level of patients. The HAMA includes 14 items, with a total score range of 0–56. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.87, and higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety [16].

(4) Postoperative recovery indicators: These included time to tolerate semi-liquid diet (time from surgery to first intake of ≥ 200 mL semi-liquid food), time to first out-of-bed activity (time from surgery to independent standing and walking ≥ 5 m), time to first postoperative anal exhaust and total length of hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0. Categorical data were expressed as n (%), and continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s). The chi-square (χ²) test and t-test were used for comparisons. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and surgical indicators

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics, including age, gender, pathological stage, lesion location or surgical method (Table 1). No significant differences were observed between the observation group and the control group in terms of surgical time (152.3 ± 21.5 min vs. 158.7 ± 24.1 min, P = 0.212) or intraoperative blood loss (320.4 ± 85.6 mL vs. 335.2 ± 92.3 mL, P = 0.432).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics and surgical indicators between the two groups

| index | Observation group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | statistics (t/χ²) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 57.13 ± 2.91 | 58.21 ± 3.15 | 1.632 | 0.107 |

| Gender (male / female) | 19/21 | 18/22 | 0.125 | 0.724 |

| Child-Pugh Classification (A / B) | 28/12 | 26/14 | 0.327 | 0.568 |

| Tumor Diameter (cm) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 1.044 | 0.300 |

| Surgical method (open abdomen/ laparoscopy) | 22/18 | 24/16 | 0.222 | 0.637 |

| bleeding volume during operation (mL) | 320.4 ± 85.6 | 335.2 ± 92.3 | 0.786 | 0.432 |

| Time of surgery (min) | 152.3 ± 21.5 | 158.7 ± 24.1 | 1.265 | 0.212 |

Psychological stress responses in both groups

Following the intervention, the observation group exhibited significantly lower scores than the control group in the following measures: Psychological Stress Response Questionnaire total score, 40.92 ± 5.23 vs. 51.23 ± 6.74 (t = 7.891, P < 0.001); HAMA score, 19.32 ± 4.54 vs. 23.86 ± 5.76 (t = 4.112, P < 0.001); and HAMD score, 21.22 ± 2.26 vs. 24.66 ± 2.17 (t = 6.943, P < 0.001) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of SRQ scores between the two groups [(Mean ± SD), Points]

| group | n | emotional response | behavioral responses | Somatic reaction | SRQ total score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At admission | At discharge | At admission | At discharge | At admission | At discharge | At admission | At discharge | ||

| observation group | 40 | 26.17 ± 3.24 | 17.32 ± 4.54 | 15.53 ± 4.27 | 9.75 ± 1.24 | 20.15 ± 3.03 | 13.85 ± 2.25 | 61.85 ± 6.54 | 40.92 ± 5.23 |

| control group | 40 | 26.84 ± 3.15 | 21.42 ± 5.76* | 15.12 ± 4.15 | 12.39 ± 2.76* | 20.66 ± 3.16 | 17.39 ± 2.82* | 62.62 ± 6.47 | 51.23 ± 6.74 |

| t price | 3.872 | 5.621 | 6.134 | 7.891 | |||||

| P price | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

Table 3.

Comparison of anxiety and depression levels between the two groups [(Mean ± SD), Points]

| group | n | HAMA | HAMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the intervention | After the intervention | Before the intervention | After the intervention | ||

| observation group | 40 | 28.45 ± 5.65 | 19.32 ± 4.54 | 31.09 ± 4.16 | 21.22 ± 2.26 |

| control group | 40 | 27.84 ± 5.27 | 23.86 ± 5.76 | 32.18 ± 4.51 | 24.66 ± 2.17 |

| t price | 4.112 | 6.943 | |||

| P price | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

Postoperative recovery and complications

The observation group experienced substantially shorter times than the control group in the following postoperative indicators: time to first anal exhaust, 28.4 ± 5.06 h vs. 34.8 ± 6.73 h (P < 0.001); time to first out-of-bed activity, 31.5 ± 4.18 h vs. 40.5 ± 4.59 h (P < 0.001); and length of hospital stay, 13.5 ± 3.36 days vs. 18.3 ± 4.43 days (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of postoperative recovery between the two groups (Mean ± SD)

| index | Observation group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | statistics (t/χ²) | P price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First postoperative exhaust time (h) | 28.4 ± 5.06 | 34.8 ± 6.73 | 5.232 | < 0.001 |

| First time out of bed after surgery (h) | 31.5 ± 4.18 | 40.5 ± 4.59 | 9.415 | < 0.001 |

| Tolerance to semi-liquid feeding time (h) | 78.529.29 | 99.3612.54 | 14.867 | <0.001 |

| length of stay (d) | 13.5 ± 3.36 | 18.3 ± 4.43 | 5.876 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative complication rate (%) | 12.5(5/40) | 30.0(12/40) | 4.286 | 0.038 |

The incidence of postoperative complications in the observation group was 12.5% (5/40), significantly lower than that in the control group (30.0%, 12/40) (χ² = 4.286, P = 0.038). The main complications included wound infection (3 vs. 7 cases) and abnormal liver function (2 vs. 5 cases).

Discussion

This study confirms that graded nursing interventions based on quantitative risk assessment substantially reduce psychological stress levels (SRQ, HAMA/HAMD scores) and improve postoperative recovery indicators (e.g. time to first anal exhaust, length of hospital stay) in patients undergoing liver cancer resection. These findings align with recent trends in personalised nursing under the ERAS concept [22, 23]. By integrating multidimensional assessment and dynamic resource allocation, this study further expands the practical pathway for integrated physiological–psychological management during the perioperative period of liver cancer.

Comparison with traditional nursing models

Traditional nursing models primarily focus on monitoring physiological indicators and preventing complications but lack systematic and targeted interventions for psychological stress. Recent studies indicate that conventional nursing alone achieves anxiety relief (SAS < 50 points) in only 36%-41.7% of liver cancer patients, consistent with prior reports of limited efficacy in anxiety management [24]. In this study, although ERAS-based routine nursing in the control group shortened hospital stays, the HAMA score (23.86 ± 5.76) remained higher than that in the observation group (19.32 ± 4.54), suggesting that relying solely on physiological recovery measures is insufficient to comprehensively improve psychological states. Similarly, studies in gynaecological oncology have shown that conventional nursing has limited effects on preoperative stress responses, whereas individualised psychological interventions can reduce anxiety scores (Self-Rating Anxiety Scale) by more than 25% [25]. This study achieved precision in psychological intervention through risk-stratified allocation of specialist nurses (e.g. psychiatric nurses leading mindfulness training), resulting in a 33.9% reduction in SRQ total scores (61.85 → 40.92), substantially better than the 18.2% reduction observed in the control group (62.62 → 51.23), further validating the necessity of stratified interventions.

Similarities and differences with other systematic nursing studies

Previous systematic nursing studies have shown that comprehensive interventions can improve negative emotions and quality of life in patients with liver cancer, but these interventions often adopt a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, lacking dynamic risk assessment and resource matching [26]. In contrast, the innovations of this study include: (1) a multidimensional quantitative assessment system, integrating Child–Pugh scores (liver function), HAMA/HAMD scales (psychological state) and comorbidity scores to overcome the limitations of single-indicator assessments; and (2) dynamic resource allocation, matching nursing resources to risk levels – for example, assigning N3 nurses and multidisciplinary teams for daily rounds in high-risk cases and applying music therapy and personalised exercise plans to alleviate anxiety. These approaches are consistent with the concept of multidisciplinary collaboration in conversion therapy [25].

Synergistic effects with ERAS and conversion therapy

The ERAS concept emphasises shortening hospital stays and promoting physiological recovery but gives insufficient attention to psychological support [26]. This study addresses that gap through the graded nursing model. For example, the ‘stepwise rehabilitation management’ approach for patients under high-risk (bed activities → sitting at the bedside → standing and walking), combined with psychological counselling, not only shortened the time to first out-of-bed activity (31.5 ± 4.18 h vs. 40.5 ± 4.59 h) but also reduced the incidence of complications (12.5% vs. 30.0%). These results reflect the collaborative practices of multidisciplinary teams in liver cancer conversion therapy. Future research could explore how graded nursing can be integrated with conversion therapy, for example, by incorporating tumour biological characteristics and psychological states into preoperative assessments to develop more individualised intervention plans.

Study limitations and future directions

Despite the positive findings, this study has several limitations: (1) the small sample size (n = 80) and single-centre design may limit the generalisability of the conclusions; (2) long-term psychological outcomes (e.g. at 3 months postoperatively) and survival rate changes were not assessed; and (3) the comorbidity scoring used in the risk stratification criteria was not refined – for example, it did not account for differences in weight between cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Future directions include conducting multicentre randomised controlled trials to validate the effectiveness of the graded nursing model across different healthcare settings, extending follow-up durations and investigating the potential impact of psychological interventions on tumour recurrence using liquid biopsy indicators (e.g. circulating tumour DNA).

Conclusion

This study adopted a graded nursing model based on quantitative risk assessment, using objective indicators to construct an effective risk assessment system that comprehensively addresses the multidimensional needs of patients and supports differentiated risk management strategies. This nursing model reflects advanced nursing concepts and standardisation.

In patients undergoing liver cancer resection, the implementation of graded nursing interventions based on quantitative assessment strategies helps reduce the intensity of perioperative stress responses, enhances physiological and functional improvements and thereby promotes postoperative recovery. Furthermore, by conducting in-depth research on satisfaction with and implementation of graded nursing programmes, this study further refines the nursing grading mechanism.

By adhering to the principles of patient-centred care and the characteristics of humanised management, as well as the core aim of compassionate services, it improves the perioperative nursing grading system for patients undergoing liver resection, enhancing their compliance with treatment and satisfaction with the nursing process.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work: Zhang L, Ren XC; Data collection: Xu LP, Zheng SM, Xu QH; Supervision: Zhang L, Ren XC; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Ren XC, Xu LP, Zheng SM, Xu QH; Statistical analysis: Zhang L, Ren XC, Xu QH; Drafting the manuscript: Zhang L, Ren XC; Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors; Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Funding

Provincial Medical Project: Research on the application and intervention mechanism of menu-based nursing intervention based on HAPA model in stress response and self-health management of patients after liver cancer resection (No.2025KY249).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University. Written informed consent was signed by all participants in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Zhang and Xiaochao Ren contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Singal AG, Kanwal F, Llovet JM. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(12):864–84. 10.1038/s41571-023-00825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holzer KJ, Bollepalli H, Carron J, et al. The impact of compassion-based interventions on perioperative anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;365:476–91. 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan DJH, Quek SXZ, Yong JN, et al. Global prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):864–75. 10.3350/cmh.2022.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Zhang H, Zhang Z, et al. The mediating effect of resilience on the relationship between symptom burden and anxiety/depression among Chinese patients with primary liver cancer after liver resection. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:3033–43. 10.2147/PPA.S430790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X, Li YM, Wang Q, et al. Machine learning model based on RCA-PDCA nursing methods and differentiating factors to predict hypotension during Cesarean section surgery. Comput Biol Med. 2024;174:108395. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters R, Hipper TJ, Kricun H, et al. A quantitative public health risk assessment tool for planning for At-Risk populations. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S4):S286–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hijazi A, Galon J. Principles of risk assessment in colon cancer: immunity is key. Oncoimmunology. 2024;13(1):2347441. 10.1080/2162402X.2024.2347441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puttipanyalears C, Denariyakoon S, Angsuwatcharakon P, et al. Quantitative STAU2 measurement in lymphocytes for breast cancer risk assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):915. 10.1038/s41598-020-79622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemminki K, Försti A, Hemminki O, et al. Long-term survival trends for primary liver and pancreatic cancers in the nordic countries. JHEP Rep. 2022;4(12):100602. 10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pu C, Tian S, He S, et al. Depression and stress levels increase risk of liver cancer through epigenetic downregulation of hypocretin. Genes Dis. 2020;9(4):1024–37. 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jinks RC, Royston P, Parmar MK. Discrimination-based sample size calculations for multivariable prognostic models for time-to-event data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:82. 10.1186/s12874-015-0078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer (2022 Edition). Liver Cancer. 2023;12(5):405–44. 10.1159/000530495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Prevention and Treatment Expert Committee, Cross-Straits Medicine Exchange Association. [Chinese expert consensus on the peri-operative management of hepatectomy for liver cancer (2021 Edition)]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2021;43(4):414–30. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20210314-00228. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruf A, Dirchwolf M, Freeman RB. From Child-Pugh to MELD score and beyond: taking a walk down memory lane. Ann Hepatol. 2022;27(1):100535. 10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100535 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, et al. The Hamilton anxiety scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(1):61–8. 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Boessen R, Groenwold RH, Knol MJ, et al. Comparing HAMD(17) and HAMD subscales on their ability to differentiate active treatment from placebo in randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(3):363–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang YY, Zhong JH, Su ZY, et al. Albumin-bilirubin versus Child-Pugh score as a predictor of outcome after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2016;103(6):725–34. 10.1002/bjs.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li HY, Xu H. The impact of mindfulness relaxation training on perioperative stress response and postoperative recovery in surgical patients. Chin J Practical Nurs. 2020;36(3):170–5. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1672-7088.2020.03.002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the health action process approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(3):161–70. 10.1037/a0024509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negash A, Khan MA, Medhin G, et al. Mental distress, perceived need, and barriers to receive professional mental health care among university students in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):187. 10.1186/s12888-020-02602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogani G, Sarpietro G, Ferrandina G, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in gynecology oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(5):952–9. 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pędziwiatr M, Mavrikis J, Witowski J, et al. Current status of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in Gastrointestinal surgery. Med Oncol. 2018;35(6):95. 10.1007/s12032-018-1153-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X, Qiu J, Li H, Yang Y, Chen X. Psychological intervention based on psychosomatic integration nursing system improves mental health in liver cancer patients. Chin J Interv Radiol. 2023;11(4):210–5. 10.3877/cma.j.issn.2095-5782.2023.04.014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Lai Q, Tian Y, et al. Effect of evidence-based nursing intervention on upper limb function in postoperative radiotherapy patients with breast cancer. Med (Baltim). 2020;99(11):e19183. 10.1097/MD.0000000000019183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuominen L, Stolt M, Meretoja R, et al. Effectiveness of nursing interventions among patients with cancer: an overview of systematic reviews. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(13–14):2401–19. 10.1111/jocn.14762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.