Abstract

CDK2 has emerged as a pivotal target in cancer chemotherapy. To develop a novel CDK2 inhibitor scaffold, multiple rational, structure-based design strategies were applied to known potent CDK2 inhibitors. Through retrosynthetic planning, chemical synthesis, and characterisation, compounds 2–8 were generated. Initial in vitro screening using the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel, followed by accurate cytotoxicity (GI50) measurements, shortlisted compounds 5, 8b, and 8d as promising candidates. These compounds exhibited GI50 values as low as 0.6 μM and demonstrated favourable safety profiles, with selectivity indices reaching up to 7.98. The top two active compounds, 5 and 8b, were further evaluated against the most sensitive cell line, MDA-MB-468 (breast cancer), at their respective GI50 concentrations. Flow cytometric cell cycle analysis revealed 82% and 78% G1 phase arrest for compounds 5 and 8b, respectively, suggesting an effective CDK2/cyclin E targeting mechanism. Furthermore, annexin V-FITC apoptosis assays showed robust pro-apoptotic effects, with total apoptosis induction elevated 34.5-fold and 32.4-fold over the negative control for compounds 5 and 8b, respectively. Subsequent CDK2/cyclin E1 enzymatic inhibition assays confirmed the potency of these compounds, with IC50 values of 3.92 nM for 5 and 0.77 nM for 8b, compared to 1.94 nM for the reference inhibitor roscovitine. Notably, the novel lead compound 8b exhibited approximately 2.5-fold greater potency than roscovitine. Molecular docking studies further supported the experimental findings and provided structural insights for future optimisation of this promising CDK2 inhibitor scaffold.

Rationally directed design strategies allowed for the discovery of a novel CDK2 inhibitor lead compound outmatching roscovitine, exhibiting remarkable CDK2 inhibition, apoptosis induction, G1/S cell cycle arrest, and a promising safety profile.

1. Introduction

Due to the essential role of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in driving the cell cycle, they have drawn attention as effective cancer targets.1 Of special interest in cancer chemotherapy is CDK2, due to its overexpression, loss of cell cycle checkpoint regulation, mutation-induced potentiation of its action (via cancer-related indigenous CDK2 inhibition deactivation), and enhancement of the cancer cells' evasion of apoptosis.2 Accordingly, CDK2 inhibitors have been considered vital chemotherapeutic candidates, preventing cancer development and progression.3 Moreover, the activity and phosphorylation function of CDK2 are strictly regulated by regulatory proteins, namely cyclins, especially cyclins A and E,4 and they are directly involved in the G1/S transition and DNA replication.5 However, the design of an exclusively selective CDK2 inhibitor has been a challenge due to the existence of multiple subtypes of CDKs, which are structurally related in both kinase and cyclin-binding domains.6 Accordingly, off-target side effects are likely; however, the strategy of simultaneously targeting multiple kinases remains advantageous (e.g. in cancer chemotherapy) due to the involvement of each subtype in different phases of the cell cycle.7 Commonly known potent CDK2 inhibitors (e.g. roscovitine8 and dinaciclib,9Fig. 1) are under clinical investigation despite their reported activity against CDK110,11 (involved in G2/M transition), CDK511 (related to neurogenesis and Alzheimer's disease) and other subtypes.

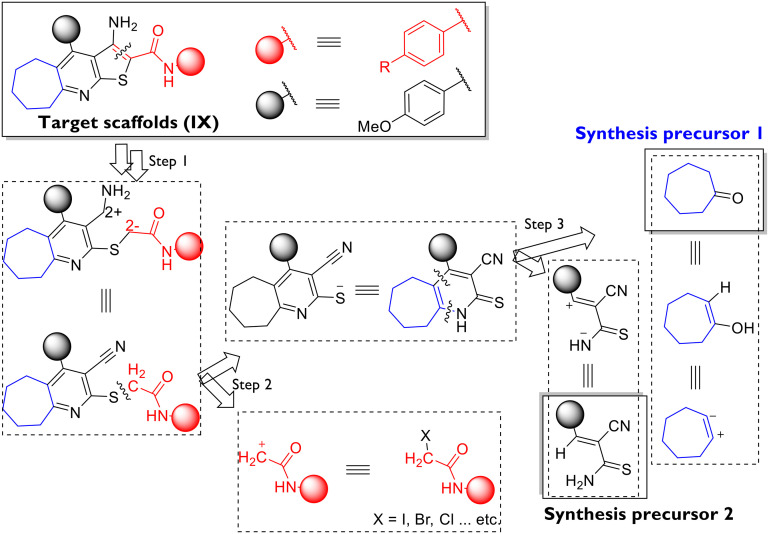

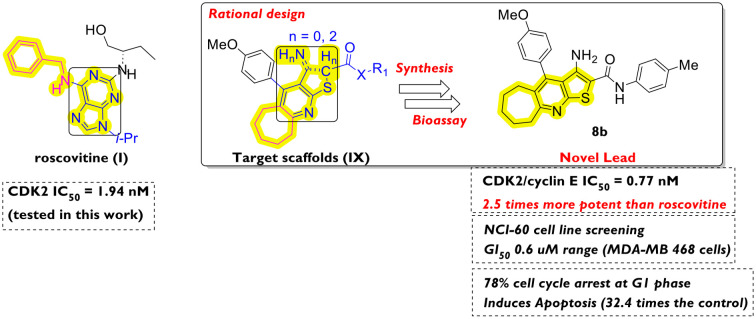

Fig. 1. Drug design strategies employed in the design of target scaffolds (IX) from reported potent ones (I–VIII): S1 ring variation; S2 ring closure; S3 rigidification of the structure; S4 isosteric substitution; S5 bioisosteric substitution; S6 ring expansion/contraction; S7 modification of the aromatic substituent; S8 changing the position of the aromatic substituent. Structural motifs inside rectangles are the ATP-binding site-targeting ones. Motifs in blue are of design interest as starting points for molecular modifications. Motifs in magenta colour represent the CDK2 hydrophobic pocket targeting groups.

From a drug design perspective, the example of dinaciclib's9,12 targeting of the conserved ATP-binding site within the CDK2 structure has been followed flexibly in the previous literature. Diverse structures of heterocyclic scaffolds have been reported to target CDK2 at the ATP site, the glycine-rich loop (which chelates the ATP phosphate backbone), the aspartate/glutamate domain (which coordinates the magnesium ion and stabilises the ATP), and the lysine/threonine domain (which properly positions the ATP for initiating the phosphorylation).9,12 Purines (e.g. roscovitine [I]8), pyridine-N-oxides (e.g. dinaciclib [II]9,12), 2,5-disubstituted-4-aminothiazoles (scaffolds III–V,13VII14) and 3,4-disubstituted-pyrazoles (scaffold VI15) are representative examples (Fig. 1). In these examples, the allosteric hydrophobic domain (isoleucine/leucine/phenylalanine within the CDK2 α-subunit) has been simultaneously targeted to different extents by the CDK2 inhibitors' lipophilic substituents (Fig. 1). Other examples of aminothiazole16 and benzimidazole,17 as well as aliphatic thiosemicarbazide, semicarbazide, and acylhyrazone linkers,18 have been reported to target the kinase site within the CDK2 enzyme while exhibiting potent antiproliferative activities.

In this article, we introduce the cyclohepta[e]thieno[2,3-b]pyridine scaffold (scaffold IX, Fig. 1) as a novel chemotype targeting CDK2 for cancer chemotherapeutic applications.

Admittedly, structurally relevant cycloalkyl[b]thieno(furo)[3,2-e]pyridine analogs have been reported as bioactive hits with anti-inflammatory activity,19 acetylcholine esterase (AChE) inhibitory activity (for Alzheimer's disease),20–22 antiviral activities against HCV,23 tick-borne encephalitis virus [TBEV]24 and dengue virus,25 potent antiplatelet aggregation activity,26 and antimicrobial activity targeting DNA gyrase,27 in addition to potent antiproliferative activities, especially against breast cancer with an unknown target (scaffold VIII28) and known ones (e.g. eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase [eEF2-K],29 sirtuin-2 selective inhibitors [SIRT-2],30 tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I [TDP1],31 phospholipase C enzyme32 and microtubules33). More details regarding other representative potent ligands are available in Fig. S1 (ESI†).

To the best of our knowledge, no fused tricyclic compounds, resembling the target scaffold (IX, Fig. 1, and series 8, Scheme 2) have been reported in the literature with cancer cell cytotoxicity except for VII. We consider this an advantage of this work, as it introduces a novel lead among CDK2 inhibitors and anticancer agents in general.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of target compounds 2–6, 7a–e, and 8a–d. Reagents and conditions. [i]: Piperidine/EtOH, reflux 4 h; [ii]: ClCH2CO2Et/AcONa/EtOH, reflux 1 h; [iii]: ClCH2CONH2/AcONa/EtOH, reflux 1 h; [iv]: EtONa/EtOH, reflux 5 min.; [v]: ClCH2CO2Et/EtONa/EtOH, reflux 10 min.; [vi]: ClCH2CONH2/EtONa/EtOH, reflux 10 min.; [vii]: AcONa/EtOH, reflux 1 h; [viii]: EtONa/EtOH, reflux 10 min.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Design of novel lead scaffolds (IX) and retrosynthesis plan

The rationally directed approach followed in the design of the target scaffold (8) was based on the sequential ring closure strategy starting from 2, 3 and 5 (fused bicyclic compounds), passing through 4 and 6 (fused tricyclic compounds), and then adding an arylamide moiety to confer an extra-binding ability on the ligand to the ATP site. Finally, lead optimisation was planned via isosteric substitution at the C2-arylamide ring (as shown later in Scheme 2). It is worth noting that the alicyclic ring expansion strategy was applied to all target scaffolds following a reported enhancement in the antiproliferative activities of closely related compounds, although a specific cancer target has never been reported (scaffold VIII, Fig. 1). Furthermore, other drug design strategies were employed, including bioisosteric substitution of the lipophilic groups with the alicyclic seven-membered ring in target compounds (the employed drug design protocol is shown Fig. 1, with the corresponding strategies encoded S1–S8).

Given the need for clinical validation of the potential of CDK2 inhibitors in humans and the pharmacokinetic obligations imposed on candidate drugs, we designed our target compounds to have enhanced membrane solubility (due to the lipophilic alicyclic motif) along with tunable adjustment of the overall molecule polarity (via modifying C2-arylamide ring substituents).

Accordingly, the disconnection approach, highlighted in Scheme 1, was implemented to guide the synthetic methodology in the next step.

Scheme 1. Retrosynthesis analysis of target scaffold 8via employing the disconnection approach.

2.2. Chemical synthesis of target scaffolds IX (compounds 2–6, 7a–e and 8a–d)

As inspired by the above-mentioned retrosynthesis (Scheme 1), target compounds were synthesised as outlined in Scheme 2. Compound 2 was employed as the key starting material for the synthesis of the target compounds (Scheme 2). Thus, the reaction of 1 with cycloheptanone under reflux in ethanol and in the presence of a catalytic amount of piperidine afforded compound 2 in a yield of 27%. Although modest in yield, this reaction was readily performed on the multigram scale and required inexpensive reagents. The structure of compound 2 was confirmed by spectral and elemental analyses (cf. Experimental section). The reaction is thought to follow a multistep condensation–Michael addition [4 + 2] cyclisation. Notably, an aromatic tautomeric state is likely to exist (2′) in an equilibrium balance with 2 in the solution phase. Compound 2 was subjected to a series of condensation reactions to provide the target compounds as follows. Firstly, compound 2 was reacted with ethyl chloroacetate under reflux in ethanol in the presence of a slightly molar excess of sodium acetate as a base catalyst to afford the S-alkylated products 3. On the other hand, precursor 2 was allowed to react with chloroacetamide under the same conditions to afford 5. Given the high nucleophilicity of the thioamide functionality within compound 2 and the softer nature of the sulfur atom, due to its polarizability according to the HSAB theory,34 the alkylation reactions take place at the sulfur atom via an SN2 mechanism. Intriguingly, when the same reaction was repeated after replacing the weaker base (sodium acetate) with a stronger one (sodium ethoxide), a ring closure occurred, providing thiophene derivatives (4 and 6, respectively, Scheme 2). To confirm the intermediacy of both 3 and 5 in the latter reaction, 3 and 5 were treated with sodium ethoxide under the same conditions. Compounds 4 and 6 were obtained consequently. This proves the two-stepwise nature of the reactions under harsher base (ethoxide) conditions with SN2–based alkylation at sulfur, followed by intramolecular Thorpe–Ziegler cyclisation to form the thiophene ring. Similarly, when precursor 2 was allowed to react with N-aryl-2-chloroacetamide reagents (inspired from the retrosynthesis analysis, Scheme 1) under the above-mentioned mild and vigorous basic conditions, the products were identified as fused bicyclic cyclohepta[b]pyridines 7a–e and fused tricyclic cyclohepta[e]thieno[2,3-b]pyridines 8a–d, respectively (Scheme 2). Upon treatment of 7a–d with catalytic amounts of sodium ethoxide under reflux in ethanol, they underwent intramolecular Thorpe–Ziegler cyclisation, affording 8a–d in moderate yields (Scheme 2). Controlling the substitution pattern on the 2-chloro-N-arylacetamide reagent conferred tunability on the C2-phenylcarbamoyl substitution pattern needed for the structure–activity relationship (SAR) study. Structures of all the newly synthesised compounds were fully characterised by spectral and elemental analyses (available in detail in the ESI,† Fig. S4–S22).

2.3. Biological evaluation

The design of the bioassays performed on target compounds 2–8 was based on the rationale of their structural design. Preliminary in vitro cytotoxicity screening against the NCI-60 cell line panel was performed (all compounds successfully matched the NCI selection criteria). Then, the most potent derivatives (with known in vitro cancer cell cytotoxicity GI50) were subjected to cell cycle analysis to ascertain the potential and determine the type of CDK/cyclin complex targeted. Thereafter, a specific CDK/cyclin inhibitory assay, along with an apoptosis induction assay, was carried out to gain deeper insights into the validity of the molecular mechanism of action expected from the rational design of the targeted compounds.

2.3.1. In vitro growth inhibition% (GI%) of compounds 2–8 against the NCI-60 cell line panel at a unified single molar dose of 10 μM

The examination of the anticancer activity of the cyclohepta-pyridine compounds on different NCI cell lines revealed varying antiproliferative activity results of the synthesised candidates, indicating the high influence of the substitution on the cyclohepta-pyridine moiety on the potency against the tested cell lines. For example, the presence of an unsubstituted thioacetamide side chain at the C2 position of the cyclohepta-pyridine ring significantly increased the potency of the tested compound 5, allowing for a lethal effect on most tested cell lines with a mean GI% = 83.90%. This enhanced potency of 5 was obvious upon comparing with the results of its ester derivative (3) and their precursor (2), which exhibited weak anticancer activities with a mean GI% = 19.92 and 4.66%, respectively. The substitution pattern of the free amide moiety of the thioacetamide side chain with either phenyl or p-substituted phenyl causes a remarkable decrease in potency, as in the series 7a–d (mean GI% ranging from 6.71–13.87%). Regarding the cyclohepta-thienopyridine compounds, the presence of a free carboxylate moiety, as in compound 4, diminished the anticancer potency with a mean GI% = 0.57%. On the other hand, a slight increase in potency was noticed in the cycloheptathienopyridine-2-carboxamide derivative 6 with a mean GI% of 23.30. Additionally, the substitution with a phenyl ring on the amide group maintains moderate activity, as in compound 8a with GI% = 21.45%. The introduction of a p-tolyl moiety, as in the 8b derivative, resulted in a significant increase in the activity to reach a mean GI% = 90.51%. Similarly, the substitution with a p-chloro phenyl moiety retains the promising anticancer activity with a mean GI% = 64.50% as per the 8d derivative. In contrast, incorporating a p-acetylphenyl group in compound 8c resulted in weaker growth inhibitory activity with a mean GI% = 17.49 (Table S1†). Compounds 5, 8b, and 8d were selected by the NCI (USA) to be tested in a five-dose assay, and the obtained GI50 results are depicted in Table S2.†

2.3.2. Determination of the antiproliferative activity GI50 of the promising derivatives using the NCI five-dose assay

The obtained data of the five-dose assay (0.01–100 μM) were investigated in terms of response parameters GI50, TGI, and LC50 against several cell lines. GI50 represents the compound molar concentration that leads to a 50% decrease in the net cell growth. TGI refers to the total growth inhibition (molar concentration causing total growth inhibition or cytostatic activity). LC50 is the lethal dose 50 (the compound molar concentration that results in a net 50% death of the initial cells). The calculated GI50, TGI, and LC50 values of compounds 5, 8b, and 8d against the sixty cancer cell lines (covering nine cancer types) are listed in Table S2.† In addition, the “subpanel” and “full panel” graph midpoints (MG-MID) for the GI50 were also calculated. These midpoints represent the average activity parameter across the subpanel and full panel cell lines for each drug and are used to estimate the selectivity of the tested compounds against each specific cancer cell line. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Full panel and subpanel mean graph midpoint values (MG-MID) of the GI50 parameter (μM) of the top three compounds 5, 8b, and 8d.

| Subpanel type | 5 | 8b | 8d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-MIDa | Selectivity indexc | MG-MIDa | Selectivity indexc | MG-MIDa | Selectivity indexc | |

| Leukemia | 0.645 | 6.99 | 5.58 | 0.94 | 12.67 | 1.28 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 2.299 | 1.96 | 4.91 | 1.07 | 13.01 | 1.24 |

| Colon cancer | 0.771 | 5.85 | 4.37 | 1.20 | 28.82 | 0.56 |

| CNS cancer | 0.565 | 7.98 | 5.72 | 0.92 | 19.39 | 0.83 |

| Melanoma | 6.485 | 0.69 | 3.90 | 1.35 | 15.43 | 1.05 |

| Ovarian cancer | 1.673 | 2.70 | 3.85 | 1.36 | 17.42 | 0.93 |

| Renal cancer | >26.13 | — | 6.13 | 0.86 | 18.15 | 0.89 |

| Prostate cancer | 1.30 | 3.47 | 4.83 | 1.09 | 8.49 | 1.91 |

| Breast cancer | 0.75 | 6.01 | 7.94 | 0.66 | 12.24 | 1.32 |

| Full panel MG-MIDb | 4.51b | 5.25b | 16.18b | |||

MG-MID is the average GI50 for individual subpanels for each tested compound (μM).

Full panel MG-MID is the average activity over all the tested cell lines related to each compound (μM).

Selectivity index was calculated by dividing the full panel MG-MID (μM) by individual subpanel MG-MID (μM) for each compound.

Among the results presented in Table S2,† compounds 5, 8b, and 8d exhibited significant cytotoxic activity with GI50 values as low as 0.20 μM. A deeper analysis of the results unveiled that the presence of the free thioacetamide moiety on the cyclohepta-pyridine ring in compound 5 led to marked enhancement of the anticancer potency, with a GI50 range of 5.42–0.20 μM. Few exceptions included UACC-257 (melanoma) and TK-10 (renal) cancer cell lines, showing GI50 = 53.60 and >100 μM, respectively. Fortunately, the TGI and LC50 of compound 5 surpassed 100 μM, reflecting minimal lethal effects towards the tested cell lines. Few exceptions to this safety window of compound 5 were observed in NCI-H522 (non-small lung cancer), COLO 205 and HT29 (colon cancer), SF-295 and SNB-75 (CNS cancer), MDA-MB-435 and SK-MEL-5 (melanoma), BT-549 (breast cancer), OVCAR-3 (ovarian cancer) and NCI/ADR-RES (ovarian cancer) cell lines.

The cyclisation of the free thioacetamide moiety slightly diminished the anticancer potency as in the p-substituted phenylthienopyridine-2-carboxamide derivatives 8b and 8d, with GI50 values ranging from 1.13 to 97.50 μM. The substitution with the p-tolyl moiety has a favourable effect on the potency, as exemplified by compound 8b that exhibited a GI50 range of 1.13–28.06 μM, in contrast to the p-chlorophenyl candidate 8d that demonstrated a GI50 range of 3.09–97.50 μM. As demonstrated by the data in Table S2,† it is evident that all the evaluated compounds displayed promising effects against different breast cancer cell lines with GI50 values as low as 0.33 μM, in addition to their potential activity against prostate cancer (GI50 range = 9.07–0.82 μM) and leukemia (GI50 range 23.70–0.29 μM). Also, both compounds had comparable cytotoxic effects against non-small cell lung cancer and CNS cancer cell lines, with GI50 ranges of 27.80–0.41 and 33.70–0.20 μM, respectively. Regarding the cytostatic effects, compound 8b displayed a wide range of TGI, from 5.80 to 97.00 μM, with nine cell lines surpassing 100 μM. This compound displayed promising LC50 values towards most tested cell lines (only twelve of them demonstrated LC50 values below 50 μM). Despite the moderate cytotoxic activity of compound 8d, it revealed a good safety profile against most tested cell lines, with LC50 values exceeding 97.50 μM.

Based on the data presented in Table 1, the unsubstituted thioacetamide derivative 5 demonstrated the most potent cytotoxic activity among the tested congeners, with a full panel GI50 (MG-MID) value of 4.51 μM. Additionally, it exhibited high selectivity indices toward leukaemia, colon, CNS, and breast cancer cell lines. It is of note that the selectivity index (SI) values of 3–6 indicate good selectivity towards the corresponding cell line, while the ratios higher than 6 indicate excellent selectivity. On the other hand, the compounds that do not meet either of these criteria are classified as nonselective.35,36 Despite the potent-to-moderate anticancer activities of the cyclized analogues 8b and 8d, both revealed poor selectivity towards all the tested cell lines. This opens the door for future development of the lead scaffold 8 for higher selectivity while preserving the high potency.

2.3.3. Cell cycle analysis

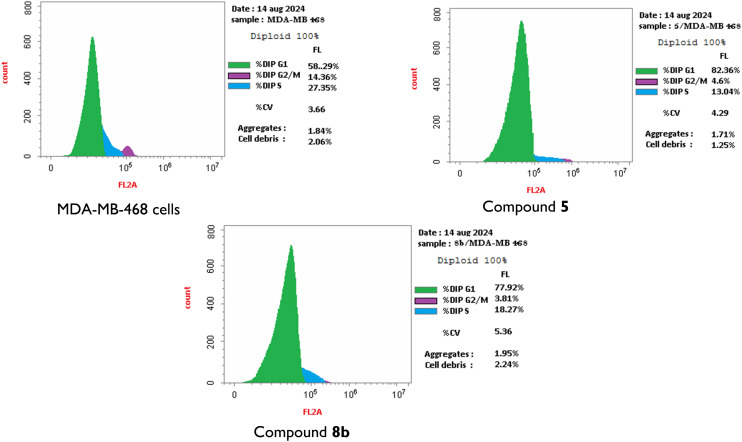

Owing to their promising activities and their good safety profiles, the bicyclic cyclohepta-pyridine-thioacetamide candidate 5 and its tricyclic analogue 8b were shortlisted as the top two compounds for further study of their effects on the cell cycle progression against the most sensitive cell line (MDA-MB-468) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cell cycle analysis of MDA-MB 468 cells before (control) and after incubation with the top two compounds (5 and 8b) at their GI50 concentrations for 24 h using DMSO as diluent.

The cells were treated with a concentration equal to the GI50 values of both compounds to gain insights into their plausible biological target at similarly bioeffective doses. The results displayed that both compounds induced cell accumulation in the G0/G1 phase (82.36% and 77.92% of the total cell population, respectively, as compared to 58.29% corresponding to the negative control, Fig. S2† and 2). In other words, both compounds revealed cell cycle cessation at the G1 phase, preventing the DNA synthesis by factors of 1.41 and 1.37 times the negative control, respectively. These results strongly recommend the CDK2/cyclin E enzyme complex (which is functionally related to the G1/S phase transition) as a potential target for compounds 5 and 8b. Accordingly, the appropriate enzyme assay was considered for further investigation of the molecular mechanism of action of these compounds, as shown below.

2.3.4. Apoptosis induction effects of compounds 5 and 8b on MDA-MB-468 cells

The capabilities of the top two compounds, 5 and 8b, to induce apoptosis in the MDA-MB-468 cell line were investigated at their GI50 concentrations, and the outcome of the experiment is presented in Fig. 3 and S3.†

Fig. 3. Effects of compounds 5 and 8b on the percentage of annexin V–FITC-positive staining in breast cancer cell line MDA-MB 468 compared to the control. The results reflect the apoptotic and necrotic induction capacity of 5 and 8b. Summation of the early (bottom right) and late (top right) apoptosis population percent quadrants represents the total apoptosis%. Different cell populations were plotted as a percentage of total events.

The results showed that both compounds induced apoptotic and necrotic effects confirmed by the elevation of percentage of cells in the early apoptosis stage from 0.54% in the control to 9.93% and 15.21%, and in the late apoptosis stage from 0.11% in the control to 12.50% and 5.87% after treatment with compounds 5 and 8b, respectively. Moreover, compounds 5 and 8b induced a total apoptosis of 22.43% and 21.08% of the cell population compared to 0.65% in the negative control. Therefore, the analysed compounds (5 and 8b) were proved to be potential apoptotic inducers. It is also worth noting that the necrotic cell populations increased after cell treatment with both compounds 5 and 8b to 7.12 and 3.92%, respectively, compared to 1.63% in the control, indicating that compound 8b is a more selective apoptosis inducer.

2.3.5. CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibition assay

According to the aforementioned results of the five-dose screening assay and cell cycle analysis, the top two compounds 5 and 8b were subjected to further investigation of their CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibitory activity in order to gain insights into their mechanism of action, correlate their promising cytotoxic activity with their ability to constrain the target enzyme, and ascertain the success of the drug design protocols employed. Roscovitine was selected as a representative reference potent CDK inhibitor, which is structurally and physico-chemically relevant to our target hydrophobic scaffold IX (Fig. 1), unlike dinaciclib (which contains a polar, hydrophilic, zwitterionic pyridine N-oxide group).

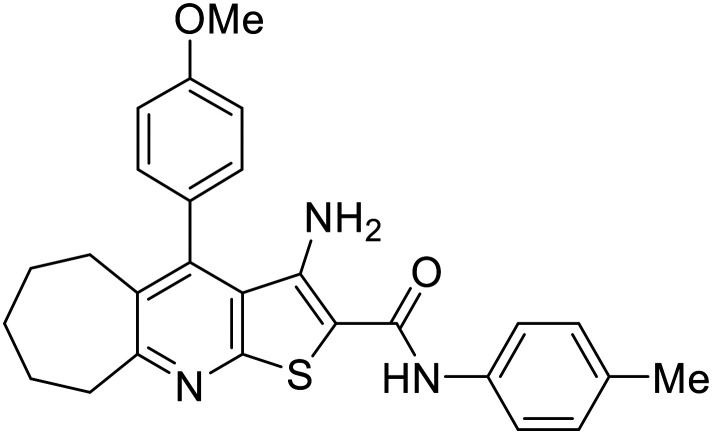

Intriguingly, both compounds 5 and 8b displayed remarkable inhibiting activities in nanomolar concentrations as presented in Table 2. Despite the superior anticancer activity of compound 5, its CDK2 inhibiting activity was only twofold lower than that of the reference standard roscovitine (3.82 nM for compound 5vs. 1.94 nM for roscovitine). On the other hand, the tricyclic analogue 8b displayed a higher activity, outmatching the potent positive control (0.77 nM for compound 8bvs. 1.94 nM for roscovitine). Accordingly, a CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibition mechanism was proved to contribute to the potent antiproliferative activities of both compounds. Moreover, the thiophene third-step cyclisation (in compound 8b) enhances the CDK2 inhibitory activity by a factor of 5.

Table 2. CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibition assay results for the top two compounds (5 and 8b) compared to roscovitine.

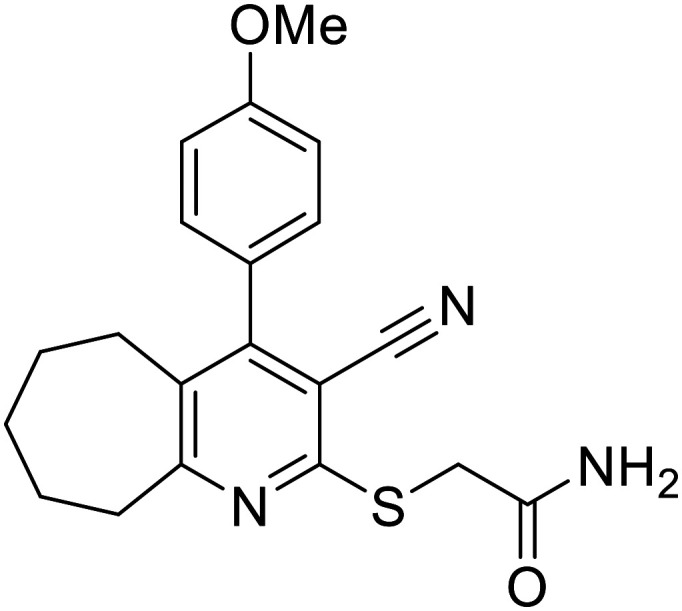

| Compound ID | Structure | IC50 (nM) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| 5 |

|

3.82 ± 0.043 |

| 8b |

|

0.77 ± 0.011 |

| Roscovitine | 1.94 ± 0.021 |

2.4. Computational studies

2.4.1. QM-based modeling of ligands having conformationally flexible rings

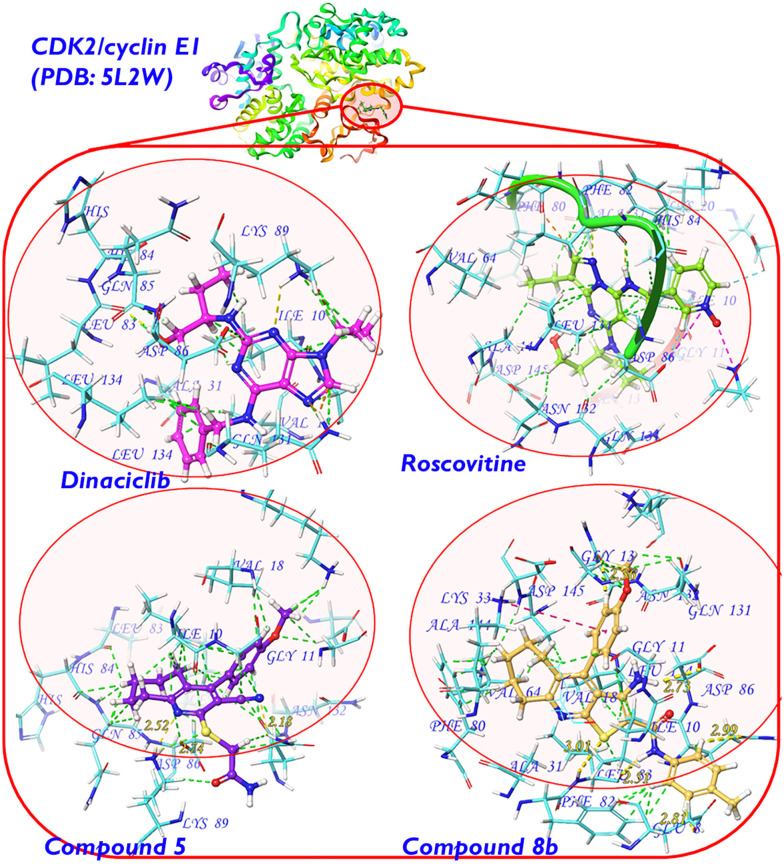

CDK2 crystal structures are widely available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and functionally influenced by binding to various cyclins during the cell cycle.3,18 As the top two target compounds (5 and 8b) displayed cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase and remarkable CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibition, we employed the crystal structure PDB 5L2W37 as a representative target protein structure source with a co-crystallised dinaciclib9,12 molecule. Dinaciclib is structurally related to roscovitine8 (the positive control utilised in the CDK2 inhibition assay) and both were starting points in the design of target scaffolds (including compounds 5 and 8b) as outlined earlier (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. On the top: the backbone structure of CDK2/cyclin E1 showing the dinaciclib binding site within the α-subunit encircled in red (PDB code: 5L2W).37 At the bottom: Ball-and-stick models showing the ligands (dinaciclib “green”, roscovitine “pink”, compound 5 “violet” and compound 8b “orange”) docked inside the CDK2/cyclin E1 α-subunit. The binding site amino acid residues are shown as stick models in cyan with corresponding labels in blue. Binding interactions are shown as dashed lines with the following color diagram: van der Waals or dipole–induced dipole interactions (green); hydrogen bonding (yellow with distance calculated in angstrom [Å]); Pi–cation interactions (salmon pink as in the case of 8b); salt bridges (magenta as in the case of dinaciclib); clashes (orange). Other than the carbon skeletons, the standard atom colour diagram is as follows: H (white), N (blue), O (red), and S (yellow).

At the ligand level, the conformational diversity of the cyclic aliphatic compounds18,38–43 shown in various bioactive compounds was proved to be more accurately described in terms of the quantum mechanical models of the most stable conformer, as we reported earlier.41 Accordingly, considering the cycloheptene moiety in compounds 5 and 8b, the same molecular mechanics-based conformational search protocol was utilised to select the most stable conformer candidate for each compound. Thereafter, a quantum mechanical structural optimisation was carried out using the B3LYP-D3 hybrid functional44 and restricted spin, as illustrated in our previous work,45,46 while applying Becke–Johnson damping dispersion corrections47 at the split-valence triple-ζ basis set 6-311G(d,p). Both LigPrep (Schrödinger package®)48 and Gaussian 16™ software49 were employed (in the MM- and QM-ligand treatment, respectively), while utilising the continuum polarizable solvation model (CPCM) to mimic the water solvation in the physiological environment.50

2.4.2. Docking study, scoring, validation, and correlation with bioassay results

The finally optimized structures of the top-two target compounds (5 and 8b), along with the two reference CDK2 inhibitors (dinaciclib and roscovitine), were then docked inside the dinaciclib binding site in the CDK2/cyclin E1 complex (PDB structure 5L2W)37 using a rigid docking protocol that minimally distorts the optimal QM-based ligand geometry reached in the previous step. Moreover, during the molecular docking process, smart charge treatment was employed. The accurate QM-based atomic partial charges (calculated through summation of the natural atomic orbitals in the NBO analysis51) were preserved for the input ligands.

At the receptor level, the atomic charges were computed via MM-based partial charge calculation (OPLS_2005 forcefield52). It is of note that the docked ligand (dinaciclib molecule in CDK2/cyclin E1 binding cavity) reproduced the same co-crystallised binding pose and protein interactions shown in the relevant protein crystal structure (PDB: 5L2W),37 which validates our employed docking protocol.

At that stage, the Glide® (Schrödinger package®)48 docking score was employed for ligand scoring. The results, shown in Table 3, demonstrate how compound 8b stands out as a superior drug candidate in terms of the docking score, which outmatched the reference CDK2 inhibitor roscovitine (−8.545 vs. −4.826, respectively). Furthermore, these theoretical results correlate perfectly with the experimental CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibitory activity assay results (Table 3). A per-residue scoring function was employed to highlight the binding site amino acid residues involved in the ligand binding.

Table 3. Docking study calculations and post-docking scoring results of the top two compounds in this study in comparison with those of the experimental positive control (roscovitine) and the co-crystallized ligand inside CDK2/cyclin E1 (dinaciclib, PDB: 5L2W37). The experimental CDK2/cyclin E1 assay IC50 (nM) values were added for comparison.

| Compound 8b | Compound 5 | Roscovitine | Dinaciclib | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2/cyclin E1 assay IC50 (nM) ± SD | 0.77 ± 0.011 | 3.82 ± 0.043 | 1.94 ± 0.021 | NDa |

| Docking score | −8.545 | −4.118 | −4.826 | −10.731 |

| MM/GBSA dG bind (kcal mol−1) | −52.37 | −23.02 | −17.62 | −68.52 |

| Amino acid residues interactionsa | Per-residue score | |||

| Lys α:9 | −0.127 | −2.651 (Coul, vdW) | −0.944 | −0.425 |

| Ile α:10 | −4.853 (vdW) | −1.431 | −4.982 (vdW, Coul) | −7.375 (vdW) |

| Gly α:11 | −0.833 | −3.204 (Coul) | −2.693 | −0.635 |

| Val α:18 | −3.909 (vdW) | +1.688 (clash) | −2.048 | −4.581 (vdW) |

| Lys α:20 | −2.082 | +0.597 (clash) | −0.713 | +2.428 (clash) |

| Lys α:33 | 1.706 (Pi–cation) | +3.558 (clash) | −0.482 | −7.023 (Coul) |

| Glu α:51 | −2.576 | −2.279 | +0.062 (clash) | +3.000 (clash) |

| Phe α:80 | −3.444 (vdW) | −0.169 | −0.300 | −1.982 |

| Phe α:82 | −4.199 (vdW) | −0.533 | −1.010 | −3.288 (vdW) |

| Leu α:83 | +0.316 (clash, HB) | −1.586 | −0.258 | −5.997 (HB) |

| Gln α:85 | −4.300 (vdW) | +0.409 (clash) | −1.628 | −1.628 |

| Asp α:86 | −0.046 | −7.486 (Coul, vdW) | −2.474 | −7.970 (ionic, Ar-HB) |

| Lys α:89 | −5.971 (vdW) | −13.846 (HB, Coul) | −3.851 (HB, vdW) | −10.988 (ionic, HB) |

| Asp α:127 | −3.158 (Coul) | −0.175 | −0.092 | +0.252 (clash) |

| Lys α:129 | +3.526 (clash) | −0.534 | −0.180 | +0.091 (clash) |

| Gln α:131 | −4.990 (Coul) | +0.727 (clash) | −2.682 | −4.403 (Coul) |

| Asn α:132 | −3.754 (Coul) | −1.141 | −1.065 | −1.780 |

| Leu α:134 | −6.409 (vdW) | −0.514 | −2.479 | −4.217 (vdW) |

| Asp α:145 | −5.951 (Coul, vdW) | −3.591 (Coul) | +1.340 (clash) | +1.340 (clash) |

van der Waals or dipole–induced dipole interactions (vdW); hydrogen bonding (HB); aromatic hydrogen bonding (Ar-HB); Pi–cation interactions (Pi–cation); salt bridges (ionic); pure coulombic interaction or dipole–dipole interaction (Coul); undesirable clashes or repulsive forces as indicated by a positive sign of the per-residue score (clash).

For more elaborate modelling of the ligand–receptor binding process, the induced-fit model53 was best employed by considering the mutual flexibility of both the ligand and the receptor binding site residues in an overall ligand–receptor complex minimisation protocol utilised via Prime® (Schrödinger package®48) following a reported method.54 In this protocol, only the ligand and the amino acid side chains (within 5 Å of the ligand surface) were allowed to be minimised in the entire ligand–receptor complex. Thereafter, the molecular mechanics, generalised born surface area (MM/GBSA) scoring function was applied for further evaluation of the binding efficiency. The calculated MM/GBSA dG bind results confirm the docking score results mentioned earlier and correlate similarly with the experimental CDK2 inhibition assay results (Table 3).

2.4.3. Ligand–receptor interactions

Sulfur-containing heterocycles are commonly known in medicinal chemistry;41,55 however, hydrogen bonding interactions are historically known as weak ones. Yet occasionally, the cumulative effect of weak binding interaction forces ends up with a strong binding affinity. This behaviour was manifested by compound 5, which surprisingly demonstrated a very strong binding interaction with Lys α:89 (per-residue score: −13.846, Table 3). Although the overall docking score and the MM/GBSA dG bind value are not remarkably high, we can safely assume that the interaction with Lys α:89 is the most important physical force involved in the binding of compound 5 to the CDK2 enzyme.

A closer view is shown in Fig. 4 (generated with Maestro® software56), where a stable six-membered ring is formed by H-bonding interactions of the 2-(carbamoylmethylthio)pyridine moiety in compound 5 with the protonated ammonium group in the Lys α:89 sidechain (N⋯H and S⋯H hydrogen bonds involved of 2.52 and 2.74 Å in length, respectively). Other relatively strong interactions of the van der Waals and the dipole/induced dipole types are shown with Asp α:86 (per-residue score: −7.486, Table 3). Interestingly, both Asp α:89 and Asp α:86 amino acid residues are intimately involved in the binding of the co-crystallised ligand (dinaciclib) and the CDK2 inhibitor (roscovitine) via the same types of physical interactions. In other words, the design of the target compound 5 successfully utilised the pharmacophoric features of dinaciclib and roscovitine, despite the apparent structural differences.

On the other hand, compound 8b showed much more intriguing results in its conceptual design than compound 5. As we mentioned above, both the docking score and the MM/GBSA binding energy outmatched those of the CDK2 inhibitor roscovitine and came considerably closer to the scoring values of the co-crystallised selective CDK2 inhibitor dinaciclib (Table 3). Accordingly, to account for this potential superior binding tendency of 8b, a comparison with dinaciclib in terms of CDK2 binding interactions is provided as follows. Generally, as compared to dinaciclib, compound 8b demonstrated similar, alternative, stronger, and additional binding site interactions along with some less effective clashes. Similar interactions with Leu α:83 were shown by 8b in which a hydrogen-bond-stabilised cyclic structure is formed with the 2-carbamoylthiophene motif (Fig. 4). However, the bulky size of the neighboring cycloheptene ring in the concise CDK2 binding site slightly shifts the 2-carbamoylthiophene moiety from optimal interaction with Leu α:83, resulting in a considerable clash (per-residue score +0.316 vs. −5.997 for dinaciclib, Table 3).

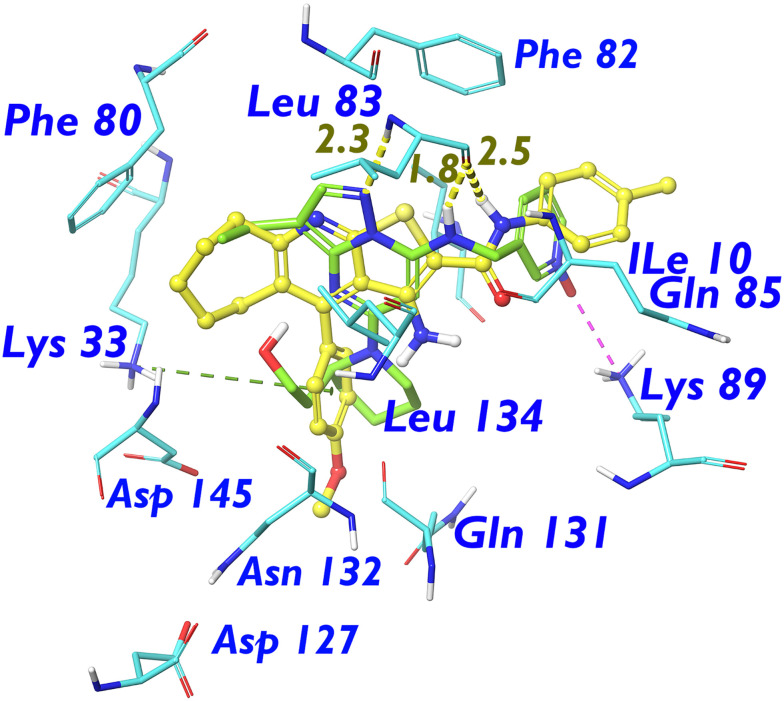

Contrarily, the merits of bio-isosteric replacement of the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine motif in dinaciclib with the 7-membered cycloheptenyl motif were manifested in the form of a higher number of comparably efficient van der Waals (vdW) interactions with the hydrophobic receptor pocket residues, namely, Ile α:10 and Leu α:134 (per-residue scores −4.853 and −6.409 for 8b, respectively, vs. −7.375 and −4.217 for dinaciclib, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Aligned ball-and-stick structural models showing the ligands (dinaciclib “green” and compound 8b “orange”) docked inside the CDK2/cyclin E1 α-subunit. The most important binding site amino acid residues are shown as stick models in standard element colours with corresponding labels in blue. Binding interactions are shown as dashed lines with the following colour diagram: van der Waals or dipole-induced dipole interactions (green); hydrogen bonding (yellow); Pi–cation interactions (salmon pink as in the case of 8b); salt bridges (magenta as in the case of dinaciclib); clashes (orange). Other than the carbon skeletons, the standard atom colour diagram is as follows: H (white), N (blue), O (red), and S (yellow). Non-polar hydrogens are removed for clarity.

Continuing the discussion about those hydrophobic pocket residues, Phe α:82 was more efficiently targeted by the 4-tolyl substituent than pyridine N-oxide in dinaciclib (per-residue score −4.199 vs. −3.288, respectively). Even at the boundary of the hydrophobic binding site cavity, the electron-poor methylene group within the side chain of Asp α:145 demonstrated much enhanced coulombic interactions of the dipole–dipole type with the electron-rich 4-methoxyphenyl motif. This enhanced rational electron demand interaction outmatched the counterintuitive clash-generating interaction of the polar 2-hydroxyethyl tail of dinaciclib with the Asp α:145 methylene sidechain (per-residue scores −5.951 and +1.340 for 8b and dinaciclib, respectively, Table 3 and Fig. 5).

As mentioned above, the unique design of our target compounds was supported by multiple strength factors. One of these factors is the capacity to serve alternative binding interactions to those displayed by the dinaciclib molecule. For instance, the salt bridge interaction with Lys α:89 shown by the pyridine-N-oxide motif in dinaciclib was successfully replaced by the carbamoylmethylthio- motif, which generated an H-bond-assisted cyclic structure with superior binding capacity. In compound 8b, the polar pyridine-N-oxide and the bio-isosteric carbamoylmethylthio group are now replaced with a totally different 4-tolyl ring attached to a semiflexible amide linker. Yet, it could successfully bind (although to a lesser extent) the Lys α:89 residue at the long carbon sidechain via vdW forces (per-residue score −5.971). Moreover, the absence of salt bridge interaction obligations with Lys α:89 allowed the 4-tolyl group in the 8b molecule to exert a stronger vdW-type interaction with the Gln α:85 sidechain carbon skeleton (per-residue scores −4.300 and −1.628 for 8b and dinaciclib, respectively, Table 3 and Fig. 5). Moreover, a stronger coulombic dipole–dipole interaction was displayed by the 4-methoxyphenyl substituent in the 8b structure with the Gln α:131 sidechain carbamoyl group than the one shown by the corresponding piperidine isostere in dinaciclib (Table 3, Fig. 5).

More intriguingly, additional types of CDK2 binding forces were displayed by compound 8b which are either vdW forces due to the enhanced lipophilicity conferred on the molecule by the cycloheptenyl motif (with Phe α:80) or dipole–dipole coulombic forces much more manifested by the methoxyphenyl substituent (with Asp α:127 and Asn α:132) than the piperidinyl one in dinaciclib (Table 3 and Fig. 5). Finally, an amazing feature of the electron-rich 4-methoxyphenyl substituent is the capacity to exhibit π–cation interaction with the Lys α:33 cationic sidechain.

In summary, the remarkable CDK2/cyclin E inhibitory activity of compound 8b could be reliably ascribed to the enhancement of the pharmacophoric features of the CDK2 selective inhibitor dinaciclib. This was implemented by modulating both the lipophilicity (extra-binding tendency of the cycloheptenyl ring and 4-tolyl substituent with Ile α:10, Leu α:134 and Phe α:82 in the hydrophobic receptor pocket) along with enhancement of the dipole–dipole interaction forces (the 4-methoxyphenyl motif outmatches the 2-hydroxyethyl tail in terms of binding Asp α:145, Asp α:127, Asn α:132 and Lys α:33 within the polar receptor pocket). Further recommendations about the carbamoylmethylthio analogues (e.g. compound 5) are to reduce the cycloheptene ring size by one carbon to relieve the steric strain inside the concise CDK2 binding site and optimise the H-bond assisted cyclic structure resulting from Lys α:89 binding. Regarding compound 8b, preserving the tricyclic cyclohepta[d]pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold seems to be optimal. Further investigations of the isosteric substitution of the 4-methoxyphenyl substituent with its more polar analog, 4-trifluoromethoxyphenyl, as well as the bioisosteric replacement of the 4-tolyl group with other lipophilic moieties (exhibiting higher Lys α:89 Pi–cation interaction tendency, e.g. naphthyls and benzothiophenyls) are recommended for the future development of the novel lead compound (8b).

3. Conclusion

Roscovitine and dinaciclib are potent inhibitors under clinical evaluation that target the ATP site within CDK2. In this study, we introduce a rational design of CDK2 inhibitors targeting the aspartate/glutamate, lysine domains, and the glycine loop of the ATP site. Multiple drug design strategies were employed on reported potent CDK2 inhibitors and other antiproliferative agents, affording the novel introduction of the cyclohepta[e]thieno[2,3-b]pyridine lead scaffold (Fig. 1). Retrosynthetic planning (Scheme 1), chemical synthesis, and characterisation afforded compounds 2–8 (Scheme 2).

Preliminary screening of the synthesised compounds against the NCI-60 cancer cell panel identified compounds 5, 8b, and 8d as potent CDK2 inhibitors, with GI50 values as low as 0.6 μM and favourable safety profiles (LC50 up to 100 μM; selectivity indices up to 7.98). Compounds 5 and 8b were further evaluated in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells, showing strong G1 phase arrest (82% and 78%) and apoptosis induction (34.5- and 32.4-fold over the control). CDK2/cyclin E1 inhibition assays confirmed their potency, with compound 8b showing an IC50 of 0.77 nM (2.5 times more potent than roscovitine).

The molecular docking study inside the ATP site of CDK2, supported by accurate quantum mechanical ligand treatments, confirmed the strong binding affinity of 8b to key CDK2 residues, outperforming reference inhibitors. Key interactions included polar binding via the 4-methoxyphenyl motif (outmatching the 2-hydroxyethyl tail in dinaciclib and roscovitine) and hydrophobic interactions from the cycloheptenyl and 4-tolyl groups. Lead compound 8b is proposed as a novel, promising CDK2 inhibitor scaffold. Preserving the tricyclic system, isosteric substitution of the 4-methoxyphenyl ring with more polar analogues, and bioisosteric replacement of the 4-tolyl with other lipophilic groups having higher Lys α:89 Pi–cation interaction tendency (e.g. naphthyl and benzothiophenyl) are recommended to enhance its potency.

4. Experimental section

The Experimental section, along with additional appropriately cited references, is provided in the ESI† (ref. 37, 41, 44, 45, 47–49, 51, 52, 54, and 56–58). More detailed data supporting the findings presented in this article are presented in Fig. S1–S22 and Tables S1–S3.†

Author contributions

Omaima F. Ibrahim: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualisation, and writing – original draft. Raed M. Maklad: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, validation, visualisation, and writing – original draft. Hajjaj H. M. Abdu-Allah: conceptualisation, project administration, supervision, and writing – review & editing. Yasmin M. Syam: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation, visualisation, and writing – original draft. Etify A. Bakhite: conceptualisation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Bethesda, USA, for performing the in vitro NCI-60 cell line panel cytotoxicity assay. R. M. M. thanks Prof. Philip A. Gale (University of Technology Sydney, Australia) for granting an honorary appointment as a Visiting Scholar at UTS. R. M. M. also acknowledges access to Australia's National Computational Infrastructure (NCI) through UTS's allocation on the Gadi supercomputer, as well as the use of the University of Sydney's Artemis HPC facility for performing DFT calculations using Gaussian software. Additionally, R. M. M. acknowledges access to the University of Sydney's Schrödinger software license (Schrödinger LLC, USA, 2023) for conducting the docking studies. All the compounds were selected for the NCI-60 Human Tumour Cell Lines Screen by the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Maryland, USA. Sixty human tumour cell lines were selected from nine cancer types—lung, colon, breast, prostate, melanoma, renal, ovarian, brain, and leukemia. These lines were chosen for their ability to grow in a common culture medium and for their consistent growth and drug response. Cryopreserved samples of each line were stored in the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program Tumour Repository.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: All the synthesis methods, characterization charts and reports along with more detailed biological assay results and methods, DFT, docking and other computational methods and the relevant output Cartesian coordinates with relevant references. Further data requests will be responded to by the lead contacts without restriction. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d5md00346f

Data availability

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its ESI.†

References

- Łukasik P. Załuski M. Gutowska I. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:2935. doi: 10.3390/ijms22062935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse S. Caldon E. C. Tilley W. Wang S. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:4233–4251. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerosa R. De Sanctis R. Jacobs F. Benvenuti C. Gaudio M. Saltalamacchia G. Torrisi R. Masci G. Miggiano C. Agustoni F. Pedrazzoli P. Santoro A. Zambelli A. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024;196:104324. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C. J. Roberts J. M. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2699–2711. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega S. Malumbres M. Barbacid M. Curr. Genomics. 2002;3:245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Akritopoulou-Zanze I. Hajduk P. J. Drug Discovery Today. 2009;14:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach S. Knockaert M. Reinhardt J. Lozach O. Schmitt S. Baratte B. Koken M. Coburn S. P. Tang L. Jiang T. Liang D. Galons H. Dierick J.-F. Pinna L. A. Meggio F. Totzke F. Schächtele C. Lerman A. S. Carnero A. Wan Y. Gray N. Meijer L. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31208–31219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlíček L. Hanuš J. Veselý J. Leclerc S. Meijer L. Shaw G. Strnad M. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:408–412. doi: 10.1021/jm960666x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruch K. Dwyer M. P. Alvarez C. Brown C. Chan T.-Y. Doll R. J. Keertikar K. Knutson C. McKittrick B. Rivera J. Rossman R. Tucker G. Fischmann T. Hruza A. Madison V. Nomeir A. A. Wang Y. Kirschmeier P. Lees E. Parry D. Sgambellone N. Seghezzi W. Schultz L. Shanahan F. Wiswell D. Xu X. Zhou Q. James R. A. Paradkar V. M. Park H. Rokosz L. R. Stauffer T. M. Guzi T. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:204–208. doi: 10.1021/ml100051d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A. Chaube S. K. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.: Anim. 2015;51:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. K. Grant S. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:662–674. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry D. Guzi T. Shanahan F. Davis N. Prabhavalkar D. Wiswell D. Seghezzi W. Paruch K. Dwyer M. P. Doll R. Nomeir A. Windsor W. Fischmann T. Wang Y. Oft M. Chen T. Kirschmeier P. Lees E. M. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2344–2353. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbrunn E. Betzi S. Alam R. Martin M. P. Becker A. Han H. Francis R. Chakrasali R. Jakkaraj S. Kazi A. Sebti S. M. Cubitt C. L. Gebhard A. W. Hazlehurst L. A. Tash J. S. Georg G. I. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:3768–3782. doi: 10.1021/jm301234k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H. Shi S. Foley D. W. Lam F. Abbas A. Y. Liu X. Huang S. Jiang X. Baharin N. Fischer P. M. Wang S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;70:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urich R. Grimaldi R. Luksch T. Frearson J. A. Brenk R. Wyatt P. G. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:7536–7549. doi: 10.1021/jm500239b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Karim S. S. Syam Y. M. El Kerdawy A. M. Abdelghany T. M. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;86:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Mohsen H. T. Syam Y. M. Abd El-Ghany M. S. Abd El-Karim S. S. Arch. Pharm. 2024;357:e2300721. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202300721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldehna W. M. Maklad R. M. Almahli H. Al-Warhi T. Elkaeed E. B. Abourehab M. A. S. Abdel-Aziz H. A. El Kerdawy A. M. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022;37:1227–1240. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2022.2062337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekhit A. A. Farghaly A. M. Shafik R. M. Elsemary M. M. A. Bekhit A. E.-D. A. Guemei A. A. El-Shoukrofy M. S. Ibrahim T. M. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;77:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon R. Marco-Contelles J. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011;18:552–576. doi: 10.2174/092986711794480186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi M. Safavi M. Allahabadi E. Rastegari A. Hariri R. Jafari S. Bukhari S. N. A. Mirfazli S. S. Firuzi O. Edraki N. Mahdavi M. Akbarzadeh T. Arch. Pharm. 2020;353:2000101. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco J. L. de los Ríos C. Carreiras M. C. Baños J. E. Badia A. Vivas N. M. Arch. Pharm. 2002;335:347–353. doi: 10.1002/1521-4184(200209)335:7<347::AID-ARDP347>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo W.-Q. Wang N.-Y. Zhu Y. Liu L. Xiao K.-J. Zhang L.-D. Gao C. Liu Z.-H. You X.-Y. Shi Y.-J. Peng C.-T. Ran K. Tang H. Yu L.-T. RSC Adv. 2016;6:40277–40286. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov A. A. Khvatov E. V. Koruchekov A. A. Nikitina A. A. Zolotareva A. D. Eletskaya A. A. Kozlovskaya L. I. Palyulin V. A. Horvath D. Osolodkin D. I. Varnek A. Mol. Inf. 2019;38:1800166. doi: 10.1002/minf.201800166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd C. M. Dai D. Grosenbach D. W. Berhanu A. Jones K. F. Cardwell K. B. Schneider C. Wineinger K. A. Page J. M. Harver C. Stavale E. Tyavanagimatt S. Stone M. A. Bartenschlager R. Scaturro P. Hruby D. E. Jordan R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:15–25. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01429-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binsaleh N. K. Wigley C. A. Whitehead K. A. Van Rensburg M. Reynisson J. Pilkington L. I. Barker D. Jones S. Dempsey-Hibbert N. C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:1997–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayed E. A. Mohsen M. El-Gilil S. M. A. Aboul-Magd D. S. Ragab A. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1262:133028. [Google Scholar]

- Leung E. Pilkington L. I. Van Rensburg M. Jeon C. Y. Song M. Arabshahi H. J. De Zoysa G. H. Sarojini V. Denny W. A. Reynisson J. Barker D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016;24:1142–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockman J. W. Reeder M. D. Suzuki K. Ostanin K. Hoff R. Bhoite L. Austin H. Baichwal V. Adam Willardsen J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:2283–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundriyal S. Moniot S. Mahmud Z. Yao S. Di Fruscia P. Reynolds C. R. Dexter D. T. Sternberg M. J. E. Lam E. W.-F. Steegborn C. Fuchter M. J. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:1928–1945. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabshahi H. J. Van Rensburg M. Pilkington L. I. Jeon C. Y. Song M. Gridel L.-M. Leung E. Barker D. Vuica-Ross M. Volcho K. P. Zakharenko A. L. Lavrik O. I. Reynisson J. MedChemComm. 2015;6:1987–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rensburg M. Leung E. Haverkate N. A. Eurtivong C. Pilkington L. I. Reynisson J. Barker D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurtivong C. Semenov V. Semenova M. Konyushkin L. Atamanenko O. Reynisson J. Kiselyov A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017;25:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:3533–3539. [Google Scholar]

- Acton E. M. Narayanan V. L. Risbood P. A. Shoemaker R. H. Vistica D. T. Boyd M. R. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2185–2189. doi: 10.1021/jm00040a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider K. Sharma S. Pokharel Y. R. Das S. Joseph A. Najmi A. K. Ahmad F. Yar M. S. Drug Dev. Res. 2022;83:1555–1577. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. Lee N. V. Hu W. Xu M. Ferre R. A. Lam H. Bergqvist S. Solowiej J. Diehl W. He Y.-A. Yu X. Nagata A. VanArsdale T. Murray B. W. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2273–2281. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldehna W. M. Habib Y. A. Mahmoud A. E. Barghash M. F. Elsayed Z. M. Elsawi A. E. Maklad R. M. Rashed M. Khalil A. Hammad S. F. Ali M. M. El Kerdawy A. M. Bioorg. Chem. 2024;153:107829. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sanea M. M. Al-Ansary G. H. Elsayed Z. M. Maklad R. M. Elkaeed E. B. Abdelgawad M. A. Bukhari S. N. A. Abdel-Aziz M. M. Suliman H. Eldehna W. M. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021;36:987–999. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2021.1915302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Warhi T. Elimam D. M. Elsayed Z. M. Abdel-Aziz M. M. Maklad R. M. Al-Karmalawy A. A. Afarinkia K. Abourehab M. A. S. Abdel-Aziz H. A. Eldehna W. M. RSC Adv. 2022;12:31466–31477. doi: 10.1039/d2ra04385h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marae I. S. Maklad R. M. Samir S. Bakhite E. A. Sharmoukh W. Drug Dev. Res. 2023;84:747–766. doi: 10.1002/ddr.22054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim T. M. Abada G. Dammann M. Maklad R. M. Eldehna W. M. Salem R. Abdelaziz M. M. El-domany R. A. Bekhit A. A. Beockler F. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023;257:115534. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Catal O. Marques I. McNaughton D. A. Maklad R. M. Ryder W. G. Hill M. J. S. Seddon A. Lewis W. Adams D. J. Félix V. Wu X. Gale P. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025;147:3392–3401. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c14194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- Maklad R. M. Moustafa G. A. I. Aoyama H. Elgazar A. A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024;30:e202400785. doi: 10.1002/chem.202400785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maklad R. M. Marae I. S. Ibrahim O. F. Mohamed S. K. Bakhite E. A. Sharmoukh W. J. Org. Chem. 2025;90:7596–7612. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5c00161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R. Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:174104. doi: 10.1063/1.2190220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, LLC, New York, USA, 2009, https://www.schrodinger.com [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A., Bloino J., Janesko B. G., Gomperts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H. P., Ortiz J. V., Izmaylov A. F., Sonnenberg J. L., Williams-Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Ranasinghe D., Zakrzewski V. G., Gao J., Rega N., Zheng G., Liang W., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Throssell K., Montgomery, Jr. J. A., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J. J., Brothers E., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Keith T., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Millam J. M., Klene M., Adamo C., Cammi R., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Farkas O., Foresman J. B. and Fox D. J., Gaussian 16, Revision C.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A. A. Maklad R. M. Zeid A. M. Mostafa I. M. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2025;5:344446. [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D., Reed A. E., Carpenter J. E. and Weinhold F., NBO Version 3.1, 1998

- Jorgensen W. L. Maxwell D. S. Tirado-Rives J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1958;44:98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maklad R. M. AbdelHafez E.-S. M. N. Abdelhamid D. Aly O. M. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;99:103767. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Warhi T. Almahli H. Maklad R. M. Elsayed Z. M. El Hassab M. A. Alotaibi O. J. Aljaeed N. Ayyad R. R. Ghabour H. A. Eldehna W. M. El-Ashrey M. K. Molecules. 2023;28:3203. doi: 10.3390/molecules28073203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, version 9.0 Schrödinger, LLC, New York, USA, 2009, https://www.schrodinger.com [Google Scholar]

- Hamed O. A. Abou-Elmagd El-Sayed N. Mahmoud W. R. Elmasry G. F. Bioorg. Chem. 2024;147:107413. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel M. W. Coussens N. P. Morris J. Taylor R. C. Dexheimer T. S. Jones E. M. Doroshow J. H. Teicher B. A. Cancer Res. 2024;84:2403–2416. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its ESI.†