Abstract

A comprehensive workflow is described to examine three contributing factors to the charge heterogeneity of Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) from a single sample. Intact AAV9 capsids were fractionated using imaged capillary isoelectric focusing (icIEF)-based fractionation, allowing for collection of capsids with different isoelectric points (pIs). Capsid integrity of the fractions was confirmed with analytical icIEF and charge detection mass spectrometry (CD-MS). Using capillary electrophoresis (CE) immunoassays, the capsid protein ratios and capsid protein deamidation were characterized. Additionally, to analyze ssDNA content packaged in each fraction, CE-immunoassay and high-resolution CD-MS were used. This study enhances our understanding of AAVs, by examining the contributions of its attributes to capsid charge heterogeneity.

Introduction

Recombinant adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have rapidly emerged as leading platforms for in vivo gene therapy, owing to their excellent safety profile, low immunogenicity, ability to transduce a wide range of dividing and nondividing cells, and capacity for sustained transgene expression. − The clinical translation of AAV-based therapies has accelerated significantly, marked by regulatory approvals for treating inherited retinal dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy, with numerous candidates advancing through clinical trials for various genetic and acquired diseases. The therapeutic efficacy and safety of AAV vectors are intrinsically linked to the quality attributes of the viral preparation, demanding rigorous analytical characterization throughout process development and for final product release. ,

The AAV particle itself is a nonenveloped virion, approximately 25 nm in diameter, with a T = 1 icosahedral capsid structure. − The capsid packages a single-stranded DNA genome (up to ∼4.7 kb), mediating host cell entry, and influencing tissue tropism and immunogenicity. , The capsid is assembled from 60 individual protein subunits derived from three overlapping viral proteins (VPs): VP1, VP2, and VP3. , These proteins are encoded by the same cap gene and expressed via a combination of alternative splicing and alternative translation initiation, resulting in their incorporation into the final capsid structure at a typical stoichiometric ratio of approximately 1:1:10 (VP1/VP2/VP3). , VP1 (81.2 kDa), VP2 (66.2 kDa), and VP3 (59.7 kDa) share a common C-terminal sequence, with VP1 and VP2 possessing unique N-terminal extensions crucial for infectivity and trafficking. ,, Based purely on their amino acid sequences, the theoretical isoelectric points (pIs) for the individual VPs, and thus the assembled capsid, are generally predicted to fall within a range of approximately 6.0–6.5, although this varies slightly depending on the specific AAV serotype. −

However, experimental characterization of purified AAV preparations consistently reveals significant charge heterogeneity, meaning the population of capsid particles shows a distribution of surface charges and isoelectric points rather than a single discrete value. This inherent heterogeneity presents considerable challenges during downstream processing, particularly for purification strategies relying on charge-based separation techniques such as ion-exchange chromatography (IEX). − IEX is a cornerstone method for separating fully assembled, genome-containing capsids from empty capsids and other process-related impurities (e.g., host cell proteins, DNA). The presence of multiple charge variants within the AAV population can lead to broad elution profiles, reduced separation resolution, coelution of product variants with impurities, and difficulties in defining consistent process parameters and product specifications.

The molecular origins of AAV capsid charge heterogeneity are diverse, but post-translational modifications (PTMs) occurring during vector production within host cells are recognized as major contributors. The VP proteins can undergo various enzymatic or spontaneous modifications, including phosphorylation (on serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues), deamidation (of asparagine and glutamine), acetylation (of lysine residues or the N-terminus), ubiquitination, and others. These PTMs can alter the charge of the amino acid residues involved. Phosphorylation introduces negatively charged phosphate groups and deamidation converts neutral asparagine or glutamine residues into negatively charged aspartic or glutamic acid (or isoaspartic acid). Consequently, the presence and distribution of these PTMs across the 60 subunits of individual capsids generate a complex ensemble of charge isoforms, each deviating from the theoretical pI predicted from the unmodified primary sequence. Understanding the specific PTMs present and their impact on the overall charge profile is therefore critical for controlling product quality.

Given the profound impact of charge heterogeneity on AAV purification, characterization, and potentially biological activity, robust analytical methods capable of resolving and quantifying these subtle differences are essential critical quality attribute (CQA) assessment. The complexity of the charge variant profile needs techniques that offer high resolution and sensitivity to effectively “unravel” this heterogeneity. This study focuses on the fractionation of AAV9 capsids by their relative isoelectric points and analysis by capillary electrophoresis (CE) and charge detection mass spectrometry (CD-MS) , to provide a detailed characterization of AAV capsid charge isoforms, shedding light on the molecular features contributing to the overall charge profile of these important therapeutic vectors.

Experimental Section

Intact AAV icIEF-Based Fractionation

Intact AAV fractionation was performed using the MauriceFlex (ProteinSimple, a Bio-Techne brand, San Jose, CA, U.S.A.) instrument and its fractionation cartridge. Pharmalytes 5–8 (17045601), 3–10 (17045601), and 8–10.5 (17045501) were purchased from Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, U.S.A. l-Arginine powder (A5006), Poloxamer 188 solution 10% (F68, P5556), and ammonia acetate powder (A1542) were from Sigma, Burlington, MA, U.S.A. 1% (101876), 0.5% (102505) methyl cellulose solution, icIEF electrolyte kit (102506), fluorescence calibration standard (046-025), SimpleSol Protein Solubilizer (046-575), pI standard ladder 3 (040-646), pI standards 6.0 (040-029), 7.0 (040-031), 8.4 (040-036), 4.05 (9046-029), and 9.22 (102231) were also obtained from ProteinSimple.

For fractionation, 15 μL of AAV9 CMV-GFP or empty AAV9 capsids (Virovek, 2 × 1013 VP/mL) was mixed into a final sample solution containing 0.35% methylcellulose, 2.5% Pharmalyte 5–8, 1.5% Pharmalyte 8–10.5, 20% SimpleSol, 25 mM arginine, and pI markers of 7.0 and 8.4. The prepared AAV sample (70 μL) was loaded in position A1 of a 96-well plate and placed onto the instrument autosampler. The isoelectric focusing process for the fractionation was 10 min at 500 V, 10 min at 1000 V, and finally 40 min at 1500 V. After focusing, charge variants were mobilized at 1000 V for 25 min, then refocused at 1500 V for 3 min to improve resolution prior to fraction collection. Fraction collection was performed by chemical mobilization using 5 mM ammonia acetate and 0.001% F68 (40 μL mobilizer per well) and a collection time of 45 s per well. The fractions were collected in wells of row B to row H of the 96 well plate and positions identified using a SpectraMax i3x plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, U.S.A. with excitation = 550 nm, emission = 580 nm) to detect the bracketing fluorescent pI markers (pI 7.0 and 8.4).

Intact AAV Charge Heterogeneity Analysis

AAV9 reference samples (diluted 100-fold) and fractions (diluted 10-fold) were analyzed by an intact AAV capsid icIEF method using the analytical icIEF cartridge (PS-MC02-C). Samples were diluted into a final sample solution containing 0.35% methylcellulose, 4% Pharmalyte 3–10, 20% SimpleSol, and pI markers (4.05 and 9.22) and focused for 1 min at 1500 V and then 6 min at 3000 V. Samples were detected using the native fluorescence mode of the instrument (excitation = 280 nm, emission = 325 nm) with an exposure time of 80 s.

Capsid Protein Charge Heterogeneity Analysis

The charge profiles of the AAV capsid proteins were measured by icIEF as previously published with slight modifications described here. Briefly, 80 μL of each fraction was mixed with 400 μL cold acetone (stored at −80 °C before use) and stored in −80 °C overnight. The solution was then centrifuged for 45 min at 13,200 rpm at −10 °C, and the supernatant discarded. The precipitate was dissolved with 88% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, 10197777001, Sigma), and 3 mM acetic acid, heated at 70 °C for 10 min, and cooled to room temperature. Denatured AAVs were mixed into a final sample solution containing 40% formamide, 0.7% methylcellulose, 3 mM DTT, 1% Pharmalyte 3–10, 3% Pharmalytes 5–8, and pI markers (pI standard ladder 3 and 8.4, ProteinSimple). The detailed assay conditions after sample preparation for denatured AAVs have been described previously.

Capsid Protein Stoichiometry Analysis

The assay was performed using a Jess CE instrument (ProteinSimple, a Bio-Techne brand). Reference AAV9 samples and charge variant fractions were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min prior to analysis using the 66–440 kDa separation module (SM-W005) with default instrument settings, except the sample load time was set to 6 s, to better resolve the capsid proteins. VP1/2/3 were detected using the B1 clone (PROGEN, 61058-647, 1:50). In the method, a molecular weight standard ladder was always run in the first column. The molecular weight (M W) vs peak position in the column was calibrated by the ladder automatically by the instrument software.

Capsid Content Analysis

Reference AAV9 samples (diluted 1:800) and fractions (undiluted) were prepared using the following procedure described previously. Genomes were resolved using the 66–440 kDa separation module. Instrument settings were default, except for the stacking load time (increased to 36 s). The AAV DNA was detected using an anti-dsDNA antibody (Bio-Techne NBP3-07302, 2 μg/mL). The total area of the DNA was used to compare between samples after normalizing for capsid protein levels (to account for sample loading).

High Resolution Capsid Content Analysis with CD-MS

CD-MS measures the m/z and charge of individual ions to directly determine the mass. AAV starting materials and fractions were buffer exchanged into 200 mM ammonium acetate (AM9070G and 10977015, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) and 0.01% F68 (ThermoFisher, 24040032) using 2 Micro Bio-Spin P6 columns (7326225, Bio-Rad, Pleasanton, CA, U.S.A.) according to company procedure. Samples were electrosprayed by a Advion Triversa nanomate into an in-house built CD-MS instrument (MegaDalton Solutions, IN, U.S.A.) at an ion energy of 130 eV/z and a charge uncertainty of ∼0.8e for 104.6 ms trapping events.

Results and Discussion

Fractionation of AAV9 Capsids

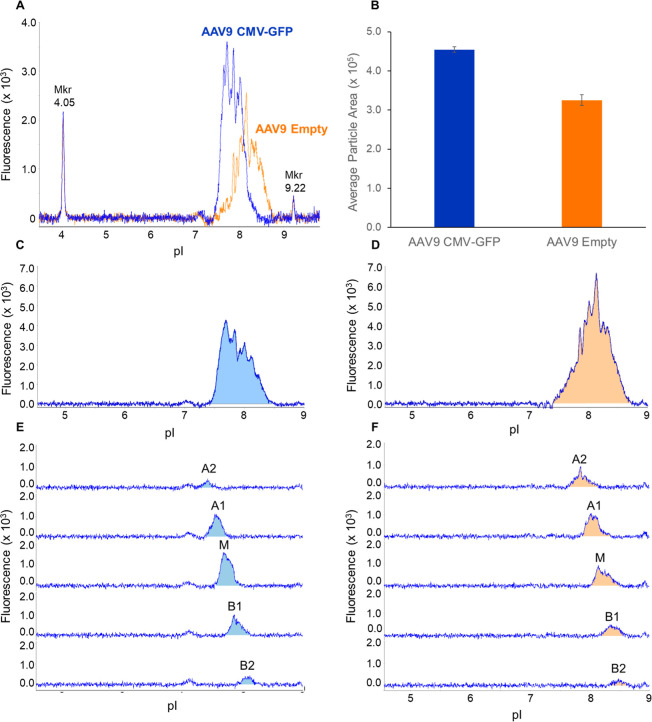

Intact AAV capsids have a reported pI range of 5.0–9.5. , Imaged cIEF (icIEF) is the gold standard for charge heterogeneity analysis of biotherapeutic and has been used extensively to characterize various antibody modalities. However, icIEF can be used for more complex molecules including fusion proteins and viruses. For this study, we obtained full AAV9 capsids (containing a CMV-GFP genome) and empty AAV9 capsids. We first examined the charge heterogeneity of both AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 intact particles by icIEF (Figure A).

1.

Charge heterogeneity analysis and fractionation of intact AAV9 capsids. (A) Triplicate injections of AAV9 CMV-GFP (blue) and empty AAV9 capsids (orange) are shown in overlay, detected using native fluorescence (excitation = 280 nm, emission = 325 nm, using an 80s exposure). A clear pI difference is seen between full and empty AAV9 capsids. (B) Analysis of area under the curve for triplicate injections of AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty capsids shows reproducible icIEF analysis of AAV capsids. Unfractionated AAV9-CMV-GFP (C) and empty AAV9 (D) were compared to the respective fractionation series. Each AAV9 reference sample was fractionated into five fractions for (E) AAV9-CMV-GFP for (F) empty AAV9 capsids. Fractions are labeled based on their relative pI position to the center of the unfractionated capsids, where A2 is the most acidic peak, M is the middle peak, and B2 is the most basic peak.

Empty AAV9 capsids spanned a wider pI range than full capsids (1.40 pH units vs 1.10 pH units) and were shifted to a higher pI. It is logical to hypothesize that the higher average pI of the empty capsids is solely due to the lack of a functional genome. However, other factors can contribute to charge heterogeneity including capsid protein post-translational modifications. Protein post-translational modifications have been observed across all three capsid proteins, can occur at multiple sites within these proteins, and are known to change the pI of the proteins. Additionally, capsid protein stoichiometry has shown to be stochastic, with hundreds of combinations existing in a single sample. ,, Most of the protein incorporated into an AAV is VP3, with typically 10-fold (or less) amounts of VP2 and VP1, which are larger and differ at their N-termini. While not previously investigated (but explored herein), it is plausible to suggest that the incorporation of capsid proteins influences the capsid isoelectric point (pI), given that each capsid protein has its unique pI value.

We developed an icIEF-based fractionation method to fractionate intact AAV capsids of varied pIs to study these effects in more detail, reasoning that unique contributors may be isolated within certain pI ranges and thus only discernible when separated from the entire capsid population. The analytical icIEF method was converted to an icIEF fractionation method with minor modifications as described in the Experimental Section.

We fractionated both AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids into five fractions (labeled as follows: acidic peak: A1, the most acidic peak: A2; main peak: M; and basic pI peaks: B1, and B2, the most basic peak) and compared both fraction sets to the unfractionated reference (Figure C–F). The fractions had average pI values that span the reference sample peak “envelope” with isoelectric points ranging from 7.40–8.50 for AAV9 CMV-GFP and 7.40–8.80 for empty AAV9 capsids. We evaluated the reproducibility of the fractionation approach as well as recovery of the AAV9 capsids in the fractions (Table ). Three consecutive fractionations for the AAV9 sample were performed and analyzed for selectivity by icIEF. Across all five peaks, we report measured pI value CVs under 0.330% (Table ). Recovery of the AAV9 CMV-GFP (75%) and AAV9 empty capsids (59%) was reasonable (Table ), given the known propensity of capsids to adhere to various surfaces.

1. Interassay Fraction Apparent pI Repeatability of the Fractions.

| A2 | A1 | M | B1 | B2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| run 1 | 7.42 | 7.58 | 7.71 | 7.86 | 8.05 |

| run 2 | 7.4 | 7.55 | 7.68 | 7.83 | 8 |

| run 2 | 7.41 | 7.55 | 7.68 | 7.84 | 8.01 |

| average pI | 7.41 | 7.56 | 7.69 | 7.84 | 8.02 |

| standard deviation | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| % CV | 0.135 | 0.229 | 0.225 | 0.195 | 0.330 |

2. Recovery Rate of the Fractionation.

| AAV9 CMV-GFP VP/mL (×109) | empty AAV9 VP/mL (×109) | |

|---|---|---|

| reference | 200.0 | 200.0 |

| A2 | 4.8 | 24.0 |

| A1 | 38.0 | 34.4 |

| M | 60.4 | 30.5 |

| B1 | 34.0 | 19.3 |

| B2 | 13.2 | 9.2 |

| Sum of fractions | 150.4 | 117.4 |

| Recovery rate | 75% | 59% |

Characterization of AAV Capsid Fractions

Capsid Protein Stoichiometry

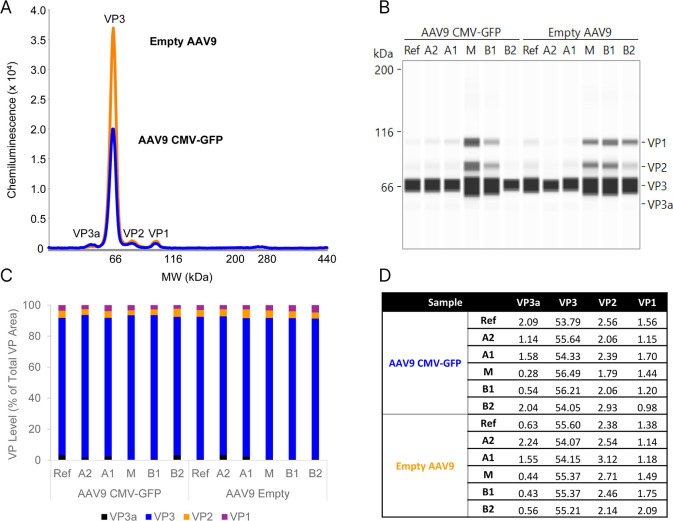

The incorporation of the three capsid proteins VP3, VP2, and VP1 has been shown to be a stochastic process, resulting in diverse intact capsids possessing different VP3/VP2/VP1 ratios. ,, Reasoning that the varied incorporation of VP3, VP2, and VP1 could lead to increased charge heterogeneity observed, a highly sensitive CE-SDS immunoassay (Simple Western) was used to measure the average capsid protein levels (“average” because the capsids are lysed, removing any particle-specific VP levels) for each reference sample and fractionation series (Figure ). Both AAV9 reference samples when analyzed at the same titer revealed four peaks: VP3, VP2, and VP1, and VP3a. We saw that the empty AAV9 capsids had nearly double the VP3 peak area (Figure A), while the other 3 VP levels were consistent between the samples. The average capsid protein ratios of the unfractionated AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 samples used in the study were 2.09:53.79:2.56:1.56 and 0.63:55.60:2.38:1.38, respectively. These samples were produced in (Sf9) insect cells, where higher levels of VP3 incorporation are routinely observed. We analyzed the fractions (20-fold diluted) and observed similar reactivity with the anti-VP1/2/3 antibody, albeit at varied signal intensities, owing to the varied abundance of capsids in each fraction (Figure B). Percent peak area (%PA) (Figure C) and absolute capsid protein levels (Figure D) further summarize the small differences between the fractions compared to the reference materials. Our data align with a recent study that examined full, empty, and partially genome-containing AAVHSC-15 capsids through CE-SDS analysis following fractionation using AUC, revealing minimal variance in VP levels. As noted, here we additionally report the abundance of VP3a which was incorporated into capsids between 0.28 and 2.04 and 0.43–2.24 proteins per capsid for AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids, respectively (Figure C).

2.

Fractionated AAV9 capsid protein analysis by Jess CE instrument, as described in Experimental SectionCapsid Protein Stoichiometry Analysis. (A) Comparison of reference samples (diluted 1:800) using an anti-VP1/2/3 antibody for detection. While similar levels of VP1, VP2, and VP3a are seen in the two samples, more VP3 is observed in the empty AAV9 capsids. (B) Comparison of the fractions (diluted 1:20) to reference material shows fractions have similar capsid proteins levels compared to the unfractionated samples. The molecular weight (M W) of the samples is calibrated by the M W ladder run in ref channel. (C) Quantitation of the data, represented as a stacked bar graph of the % peak areas of the three capsid proteins and the VP3a variant. (D) Capsid protein analysis of the reference samples and fractions, represented as total proteins present in a 60-mer.

Capsid Protein Deamidation

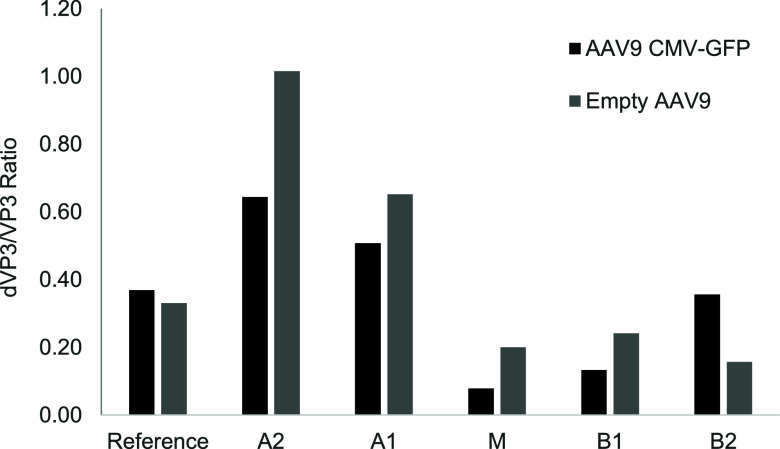

Among the PTMs observed on AAV capsid proteins, the correlation between modification and function is best understood for deamidation, which occurs across all three capsid proteins, and directly impacts potency. , While deamidation is typically measured by mass spectrometry, icIEF is a rapid and easy tool to measure capsid protein deamidation. Using an ultrasensitive IEF-based CE-immunoassay, the relative VP3 deamidation was characterized (Figures and S1). Deamidation (expressed as the ratio of deamidated VP3 to VP3) was highest in acidic fractions for both AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids. The VP3 deamidation was lower or equivalent to the reference sample in the main and basic fractions. Thus, VP3 deamidation is a significant contributor to AAV capsid charge heterogeneity.

3.

VP3 deamidation profiling. Fractions of AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids were analyzed for VP3 by denatured icIEF-immunoassay. The y-axis is the ratio of deamidated VP3 peak area to amidated VP3 peak area, normalized by the capsid protein levels present in each fraction.

Rapid Capsid Content Analysis by CE-Immunoassay

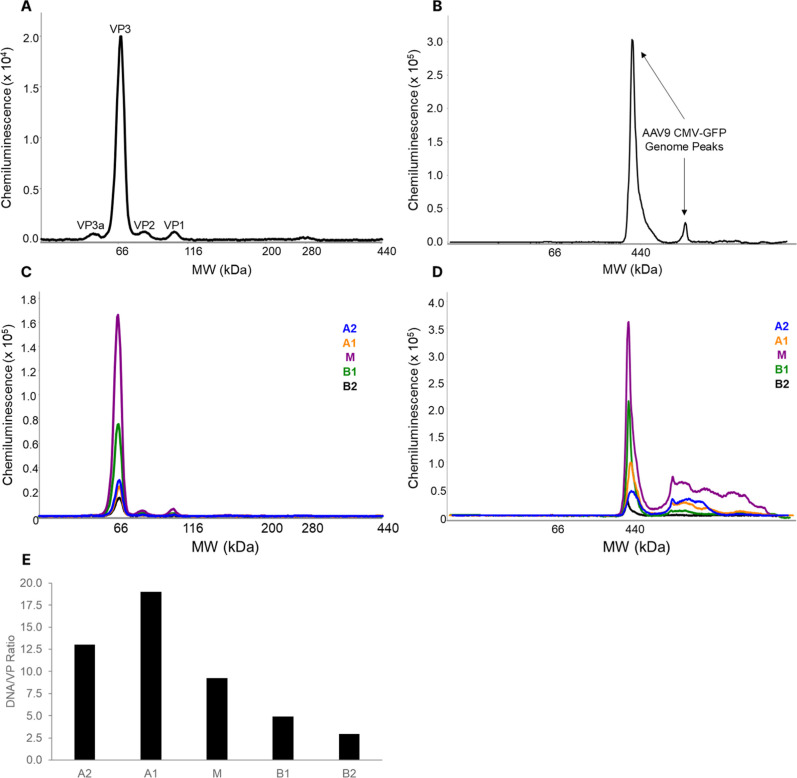

As shown in Figure , AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids have different isoelectric points, with empty capsids appearing more basic. Capsid protein incorporation was consistent across the fractions in both samples, while deamidation is enriched in the respective acidic fractions. We next analyzed the capsid content (total ssDNA content contained within the capsid) in the AAV9 CMV-GFP fractions to understand the contribution of the ssDNA genome to the charge heterogeneity of the sample. To do so, the fractions were analyzed for VP content as before, and DNA content using an anti-DNA antibody (Figure ).

4.

Capsid Content CE-Immunoassay. (A) AAV9 capsid protein analysis and (B) DNA analysis using CE-immunoassay detection of the AAV9 CMV-GFP reference sample. (C) Capsid protein analysis of the fractions and (D) DNA analysis of the fractions. As described in Experimental Section and the same as in Figure , the M W of the samples are calibrated by the M W standard ladder run in the first channel in the method. (E) Normalized DNA levels of the capsid fractions. The DNA signal for each sample was divided by the sum peak area of the capsid proteins for the same sample.

Two distinct DNA peak groups were observed for AAV9 CMV-GFP using this method (Figure B), which vary in ratio among the fractionated samples (Figure D). To accurately measure the differences in the DNA content of the fractions, all DNA peak areas were normalized by their respective capsid protein peak areas to account for the relative abundance of capsids in each fraction (Figure E). Enrichment of DNA was seen in the AAV9 CMV-GFP acidic fractions and declined as the capsids became more basic. The data are consistent with empty AAV9 capsids having a higher pI than AAV9 CMV-GFP capsids by icIEF and suggests the negative charge of the ssDNA genome, although contained within a proteinaceous capsid, influences the apparent pI of AAV9 capsids. To our knowledge, this is the first time this platform has been used in research to characterize AAV capsid content.

High Resolution Capsid Content Analysis by CD-MS

The rapid analysis of capsid content by CE as described above holds promise for supporting early stage process AAV development. Here, capsid concentrations are often low and the sample matrix can be complex (host cell proteins, e.g.). To gain a deeper insight into the capsid content of isolated charge variants, charge detection mass spectrometry (CD-MS) was leveraged which provides accurate mass measurements for AAVs. CD-MS provides good accuracy compared to sequence masses typically falling within +1% and measurement precision with triplicate variation typically ±0.005 MDa.

AAV9 CMV-GFP (provided as >90% full by the manufacturer) has a small genome (2.544 kb) compared to the packaging limit of AAV (∼4.7 kb). An individual AAV with a capsid protein ratio of 10:1:1 has an absolute capsid ratio of approximately 50:5:5 with a protein mass center at 3.724 MDa. Based on the CE-SDS data shown above, the AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 samples analyzed in this study have average absolute capsid ratios of 2.09:53.79:2.56:1.56 and 0.63:55.60:2.38:1.38, respectively. This gives a distribution of protein masses centered around 3.649 MDa and 3.642 MDa deviating ∼80 kDa from the typical stochastic assembly at 3.724 MDa.

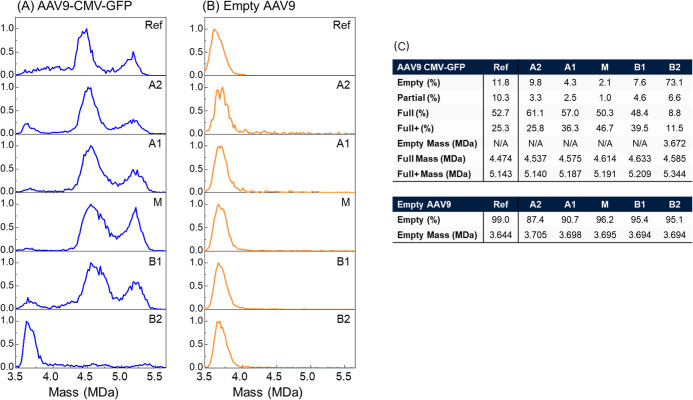

Based on the CE-SDS data, the full particles (containing a single genome of interest flanked by two inverted terminal repeats) should have a mass of 4.476 MDa. All capsid masses greater than this peak would contain either larger packaged DNA or the main DNA with copackaged fragments (Full+ range). Analysis by CD-MS (Figure A) showed that the unfractionated AAV9 CMV-GFP contained 52.7% correctly sized genome (∼4.476 MDa) and moderate abundance of empty capsids (11.8%) and subgenomic content (10.3%). The rest of the AAV9 CMV-GFP capsid content (25.3%) can be attributed to longer DNA that replicated on pathway to scDNA constructs up to the wild type packaging limit of ∼4.7 kb. This has been observed seen previously for Sf9-derived capsids when the target genome is smaller than the wild-type packaging limit. This higher mass range has a peak centered at 5.143 MDa. Previous work has shown the genome packages with at least 4% excess mass due to copackaged cations. Subtracting the expected genome and cation masses of 2.544 kb (CMV-GFP|Full) and 4.7 kb (packaging limit|Full+) from the measured CMV-GFP and Full+ peaks, residual protein mass is 3.657 and 3.633 MDa. Interestingly, a weighted average of these two values using their relative abundance gives a mass of 3.649 MDa, which agrees with the CE-SDS mass calculated 3.649 MDa (Figure C). It is important to note that the CE-SDS is based on the values of all capsids and CD-MS is measuring individual distributions within the capsid population. Fractions A1 and A2 showed the highest abundance of the ssDNA CMV-GFP genome at 61.1% and 57.0%, respectively. Additionally, Fraction A2 contains capsids closest to the reference for %dsDNA. Interestingly, the capsids from the main and B1 fractions had less ssDNA CMV-GFP (50.3% and 48.4%) but were enriched for the long genome at the apparent packaging capacity (M = 46.7% and B1 = 39.5%). In fraction B2, empty capsids (3.672 MDa) were enriched to 73.1% (5.2-fold higher than the unfractionated sample), showing that the icIEF fractionation approach can isolate empty capsids. Further method optimization may afford higher purity of empty capsids, but such efforts were not the focus of this study.

5.

CD-MS mass histograms of reference materials (top) for (A) AAV9-CMV-GFP and (B) AAV9-Empty all normalized to 1 for ions detected within the capsid mass range. Beneath each CD-MS mass histogram of the reference are the spectra for each fractionation series, shown from acidic to basic fractions. (C) Statistics from CD-MS mass histograms of reference material and fractions. Full refers to the CMV-GFP genome, while Full+ refers to packaging of the CMV-GFP genome plus other genome content (scDNA of CMV-GFP copy). Although all fractions were buffer exchanged, they might contain trace amount of SimpleSol solvent since it was added in the fractionation sample as described in Experimental Section. The impact of the SimpleSol to the CD-MS results is minimum as shown in Figure S2.

The unfractionated empty AAV9 reference material was made up of 99.0% empty capsids (3.50–4.00 MDa) with a Gaussian peak fit centered at 3.644 MDa, in good agreement with the calculated mass from the CE-SDS measurement (3.642 MDa). Empty AAV9 capsid acidic fractions (A2 and A1) had modest enrichment of DNA-containing capsids, with the relative empty capsid content dropping to 87.4% and 90.7% with capsid masses increasing to 3.705 MDa and 3.698 MDa for A2 and A1, respectively (Figure B,C). The M, B1, and B2 fractions had lower DNA content than the acidic fractions but were still enriched for DNA compared to the reference material with the empty capsid levels at 96.2%, 95.2%, and 95.1%, respectively. The mass peak of the main was 3.695 MDa, like the acidic fractions, but the two basic fractions were shifted slightly lower to 3.694 MDa. All fractions had a higher empty capsid mass, and a higher relative abundance of DNA containing capsids compared to the reference sample. This mass shift is attributed to heavily VP3 enriched capsids being lost during the fractionation (59% capsid recovery). This is supported by many fractions having narrower peak widths where the low molecular weight region of the unfractionated empty AAV9 have fallen apart. In addition we can conclude that this shift is not likely due to adduct formation or packaged genome because both cases would be expected broaden peak widths.

The masses obtained for all fractions are reported in Figure C. The particle masses increase (lowest to highest) from the most acidic fraction (A2) to the basic fraction B1, by 0.159 MDa, while the dsDNA mass shift was only 0.066 MDa across the same fractions. From the CE-SDS analysis, incorporation of VP1 (81.2 kDa) was lowest in capsids in fraction B2, highest in capsids isolated in fraction A1, and declines in capsids that are more basic (Figure ). Together, these data confirm that for the first time, intact capsids can be fractionated into unique charge variants. Importantly, they highlight the heterogeneity of AAV packaging and that even within the populations of empty and full capsids, subpopulations can be further identified by their mass differences and charge heterogeneity assessment.

Conclusions

It has been reported that empty and full capsids have a slight difference in pIs (∼6.3 vs ∼5.9, respectively) and these differences can be leveraged to some extent in purification strategies. ,, By icIEF, it was confirmed that empty AAV9 capsids possess a higher average apparent pI than AAV9 CMV-GFP capsids from the same process, however the pI difference was slightly smaller than reported. To gain a more complete understanding of the relative contributions of ratios, capsid protein post-translational modifications, and capsid content to AAV capsid charge heterogeneity, AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9 capsids were compared before and after icIEF-based fractionation. For the first time, icIEF-based fractionation of intact AAV particles was accomplished.

The method preserves capsid integrity and allows for offline characterization by methods like CE and CD-MS to be performed on the isolated capsid charge variants. Both samples, AAV9 CMV-GFP and empty AAV9, were fractionated into five fractions, each with a single peak of defined pI within the “shell” of the unfractionated material. These fractions were initially analyzed by CE-immunoassay (Simple Western) for VP3/VP2/VP1 and VP3 deamidation. , Overall, the variation in VP3 across the full capsids was higher than in empty capsids (44.5% vs 2.3%) but were small overall. For the other capsid proteins, all present at ∼1–2 proteins per capsid, VP2 levels changed the least (3.3%), followed by VP1 (22.7%), and VP3a (203%). The VP3a % difference is largest due to the unfractionated empty AAV9 capsids having low average VP3a (0.63 proteins per capsid), which was enriched 3.5-fold and 2.5-fold in A2 and A1 fractions, respectively. VP1 levels increased consistently in empty AAV9 capsids (from acidic to basic), which was confirmed by CD-MS. A clear trend was not observed in the AAV9 CMV-GFP fractions. Our findings are consistent with a recent report where full, partial, and empty AAVHSC-15 capsids had essentially the same capsid protein ratios.

Because VP3 is the dominant AAV capsid protein, the apparent pI of the capsid is largely driven by VP3 and likely VP3 PTMs. PTMs like phosphorylation, oxidation, glycosylation, and deamidation have been found on AAV capsid proteins, and all impart charged character to the amino acids they modify. Even a single PTM, across greater than 50 VP3 proteins per capsid, may have profound effects on capsid pI and capsid function.

Of the observed PTMs, deamidation has been shown to reduce the potency of AAVs and can be monitored by icIEF. , Using an icIEF immunoassay to specifically study VP3, we observed enrichment of capsids containing deamidated VP3 in the acidic fractions of both AAV9 samples and confirm that VP3 deamidation is a key driver of capsid charge heterogeneity. Empty AAV9 capsids had higher relative levels of deamidation in A2 and similar levels in A1 compared to same fractions from AAV9 CMV-GFP capsids and have similar VP3 molar ratios. Capsid engineering holds great promise for removing undesirable amino acids prone to deamidation to improve stability and targeting. , Moreover, a study leveraging icIEF fractionation to separate AAV capsid proteins was published which can be used to further facilitate deamidation characterization. Mass spectrometry analysis of AAV deamidation can be hindered by method-induced deamidation. Additionally, the significant overlap in sequence (and thus potential deamidation sites) poses further challenges. The described method alleviates both challenges, finding a buffer to control deamidation and enabling LC–MS analysis of >60% pure capsid proteins, which should further the understanding of capsid protein deamidation.

We modified a CE-immunoassay to measure the total capsid content of the capsid charge variants, where both acidic capsid fractions were found to be enriched for ssDNA. The electropherograms from the fractions (Figure D) reveal more complex profiles for the fractions compared to the reference (Figure B), where 95% of the signal comes from a single peak.

CD-MS was used to gain a deeper understanding of the packaged contents and capsid masses found in these samples. Three genome types were resolved in the AAV9 CMV-GFP sample by CD-MS: partial genome(s), ssDNA CMV-GFP, and longer incomplete scDNA genome(s) that are packaged due to the use of a small gene of interest. When evaluating these data, it is important to consider that most therapeutic AAVs package closer to the packaging limit. So, in our data, Full+ particles are in a similar range to those genome-containing AAVs. Notably, for the AAV9 CMV-GFP, we observed good correlation between CE-immunoassay and CD-MS for DNA content where fractions A2 and A1 had the highest total DNA levels (as measured by Simple Western) and the highest levels of the correct ssDNA CMV-GFP peak at 61.1% and 57.0%, respectively as measured by CD-MS. The main peak and B1 were enriched for Full+ genomes, to 46.7% and 39.5%, respectively. Partial genomes were most enriched, albeit at low levels, in fractions B1 (4.6%) and B2 (6.6%). Empty capsids (enriched to up 11.8% of reference sample) purified to >73% into the most basic fraction (B2), which also had VP3 deamidation levels like the reference sample. Reflecting on these data in the context of a therapeutic AAV, our data suggest that partial genomes (similar in size to the CMV-GFP used here) are enriched in acidic fractions, full-length genomes in the main fraction, and empty capsids in the more basic fractions.

Comparing the CE and CD-MS data for the AAV9 CMV-GFP capsids, the CE method employed here does not separate the genome species by size alone. For example, the amount of Full+ particles (containing scDNA) increase from A2 < A1 < M from 25.8 to 46.7% by CD-MS, a trend that is not observed by CE when comparing the ratios of the two main peak species in the electropherograms. Thus, the CE method can be used for a rapid, low-resolution analysis for capsid content that can be applied to process samples. Further investigation is needed to better understand the distinct species within the CE data.

The CD-MS data for the empty AAV9 capsids suggest that heavily VP3-enriched capsids are less stable or more inert in the icIEF separation as all fractions showed mass increases compared to the reference material. Measurements of the DNA-containing capsids for AAV9-CMV-GFP show the effect on pI of VP1 and VP2 content and copackaged cations. The trend for more basic fractions to increase in mass shows that the pI’s separated by icIEF are directly correlated to the amount of desirable VP1–VP2 content in the capsids.

The icIEF fractionation workflow used in the study provides an opportunity for future exploration using cell-based assays to evaluate both the therapeutic activity and/or negative reactions to specific pI fractions. Typically, all empty and partial fractions are considered undesirable in final drug product formulation, but it is possible that there are populations within the target packaging that are either less stable or less therapeutically active. Importantly, this work shows that AAV capsids formed, in any preparation, have a range of stabilities and properties and that any single method is insufficient to characterize the complex interplay of factors that drive the heterogeneity of AAVs. Better understanding these factors, specifically the pI differences and their correlation to mass and viral protein ratio measured herein, is important for ion exchange chromatography purification strategies and efforts toward a holistic understanding of AAV. The combined approach of icIEF fractionation, CE, and CD-MS has offered valuable insights into the relative charge contributions of capsid proteins, deamidation, and capsid content.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.5c03104.

Figure S1 and Figure S2 (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Some instruments used in the study were products of the employers of the authors.

References

- Wang J.-H., Zhan W., Gallagher T. L., Gao G.. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Platform for Ocular Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Mol. Ther. 2024;32(12):4185–4207. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naso M. F., Tomkowicz B., Perry W. L., Strohl W. R.. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31:317–334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Tai P. W. L., Gao G.. Adeno-Associated Virus Vector as a Platform for Gene Therapy Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2019;18:358–378. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-H., Gessler D. J., Zhan W., Gallagher T. L., Gao G.. Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Vector for Gene Therapy of Human Diseases. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2024;9(1):78. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01780-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. F.. Product-Related Impurities in Clinical-Grade Recombinant AAV Vectors: Characterization and Risk Assessment. Biomedicines. 2014;2:80–97. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines2010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werle A. K., Powers T. W., Zobel J. F., Wappelhorst C. N., Jarrold M. F., Lyktey N. A., Sloan C. D. K., Wolf A. J., Adams-Hall S., Baldus P., Runnels H. A.. Comparison of Analytical Techniques to Quantitate the Capsid Content of Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;23:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod A., Wobus C. E., Zádori Z., Ried M., Leike K., Tijssen P., Kleinschmidt J. A., Hallek M.. The VP1 Capsid Protein of Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Is Carrying a Phospholipase A2 Domain Required for Virus Infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83(5):973–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-5-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger J. C., Snowdy S., Samulski R. J.. Separate Basic Region Motifs within the Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Proteins Are Essential for Infectivity and Assembly. J. Virol. 2006;80(11):5199–5210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02723-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra S. P., Rose J. A., Hardy M., Baroudy B. M., Anderson C. W.. Direct Mapping of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Proteins B and C: A Possible ACG Initiation Codon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82(23):7919–7923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra S. P., Koczot F., Fabisch P., Rose J. A.. Synthesis of Adeno-Associated Virus Structural Proteins Requires Both Alternative MRNA Splicing and Alternative Initiations from a Single Transcript. J. Virol. 1988;62(8):2745–2754. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2745-2754.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J. A., Maizel J. V., Inman J. K., Shatkin’ A. J.. Structural Proteins of Adenovirus-Associated Viruses. J. Virol. 1971;8(5):766–770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.8.5.766-770.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson F. B., Ozer H. L., Hoggan M. D.. Structural Proteins of Adenovirus-Associated Virus Type 3. J. Virol. 1971;8(6):860–863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.8.6.860-863.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samulski R., Muzyczka N.. AAV-Mediated Gene Therapy for Research and Therapeutic Purposes. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014;1:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A. K., Zhang J., Frabutt D., Mulcrone P. L., Li L., Zeng L., Herzog R. W., Xiao W.. Fast and High-Throughput LC-MS Characterization, and Peptide Mapping of Engineered AAV Capsids Using LC-MS/MS. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2022;27:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michen B., Graule T.. Isoelectric Points of Viruses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;109(2):388–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles A. R., Sims J. J., Turner K. B., Govindasamy L., Alvira M. R., Lock M., Wilson J. M.. Deamidation of Amino Acids on the Surface of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsids Leads to Charge Heterogeneity and Altered Vector Function. Mol. Ther. 2018;26(12):2848–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. F.. Manufacturing and Characterizing AAV-Based Vectors for Use in Clinical Studies. Gene Ther. 2008;15(11):840–848. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T., Nonaka-Sarukawa M., Uchibori R., Kinoshita K., Hayashita-Kinoh H., Nitahara-Kasahara Y., Takeda S., Ozawa K.. Scalable Purification of Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 1 (AAV1) and AAV8 Vectors, Using Dual Ion-Exchange Adsorptive Membranes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009;20(9):1013–1021. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G., Bahr-Davidson J., Prado J., Tai A., Cataniag F., McDonnell J., Zhou J., Hauck B., Luna J., Sommer J. M., Smith P., Zhou S., Colosi P., High K. A., Pierce G. F., Wright J. F.. Separation of Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Empty Particles from Genome Containing Vectors by Anion-Exchange Column Chromatography. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;140(1–2):183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel A. L., Katsikis G., Sha S., Maloney A. J., Hong M. S., Nguyen T. N. T., Wolfrum J., Springs S. L., Sinskey A. J., Manalis S. R., Barone P. W., Braatz R. D.. Analytical Methods for Process and Product Characterization of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus-Based Gene Therapies. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;20:740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary B., Maurya S., Arumugam S., Kumar V., Jayandharan G. R.. Post-Translational Modifications in Capsid Proteins of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) 1-Rh10 Serotypes. FEBS J. 2019;286(24):4964–4981. doi: 10.1111/febs.15013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson E. E., Keifer D. Z., Asokan A., Jarrold M. F.. Resolving Adeno-Associated Viral Particle Diversity with Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(13):6718–6725. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. F., Draper B. E., Chen Y. T., Powers T. W., Jarrold M. F.. Quantitative Analysis of Genome Packaging in Recombinant AAV Vectors by Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;23:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F., Wu J., Haitjema C., Heger C.. Development of a Highly Sensitive Imaged CIEF Immunoassay for Studying AAV Capsid Protein Charge Heterogeneity. Electrophoresis. 2023;44(15–16):1258–1266. doi: 10.1002/elps.202300039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ProteinSimple Do Your AAV Contain DNA?; Biotechne. Application Note. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., McElroy W., Pawliszyn J., Heger C. D.. Imaged Capillary Isoelectric Focusing: Applications in the Pharmaceutical Industry and Recent Innovations of the Technology. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2022;150:116567. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2022.116567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wörner T. P., Bennett A., Habka S., Snijder J., Friese O., Powers T., Agbandje-McKenna M., Heck A. J. R.. Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Assembly Is Divergent and Stochastic. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1642–1650. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21935-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi T., Nonaka M., Maruno T., Yamaguchi Y., Fukuhara M., Torisu T., Maeda M., Abbatiello S., Haris A., Richardson K., Giles K., Preece S., Yamano-Adachi N., Omasa T., Uchiyama S.. Enhancement of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Activity by Improved Stoichiometry and Homogeneity of Capsid Protein Assembly. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2023;31:101142. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.101142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. F., Qu G., Tang C., Sommer J. M.. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus: Formulation Challenges and Strategies for a Gene Therapy Vector. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2003;6(2):174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li J., Peraramelli S., Luo N., Chen A., Dai M., Liu F., Yu Y., Leib R. D., Li Y., Lin K., Huynh D., Li S., Ou L.. Systematic Comparison of RAAV Vectors Manufactured Using Large-Scale Suspension Cultures of Sf9 and HEK293 Cells. Mol. Ther. 2024;32(1):74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl-Carboni A., Dollive S., Laughlin S., Lushi R., MacArthur M., Zhou S., Gagnon J., Smith C. A., Burnham B., Horton R., Lata D., Uga B., Natu K., Michel E., Slater C., DaSilva E., Bruccoleri R., Kelly T., McGivney J. B.. Analytical Characterization of Full, Intermediate, and Empty AAV Capsids. Gene Ther. 2024;31(5–6):285–294. doi: 10.1038/s41434-024-00444-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Wang Y.. Sample Preparation Matters for Peptide Mapping to Evaluate Deamidation of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Proteins Using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Hum. Gene Ther. 2022;33(15–16):821–828. doi: 10.1089/hum.2021.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. Z., Powers T. W., Huang S., Liu Z., Shi H., Orlet J. D., Mo J. J., Srinivasan S., Jacobs S., Zhang K., Runnels H. A., Anderson M. M., Lerch T. F.. Development of an IcIEF Assay for Monitoring AAV Capsid Proteins and Application to Gene Therapy Products. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2023;29:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Andari J., Grimm D.. Production, Processing, and Characterization of Synthetic AAV Gene Therapy Vectors. Biotechnol. J. 2021;16(1):2000025. doi: 10.1002/biot.202000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Ishii K., Koizumi S., Sakaue H., Maruno T., Fukuhara M., Shibuya R., Tsunaka Y., Matsushita A., Bandoh K., Torisu T., Murata-Kishimoto C., Tomioka A., Mizukado S., Kaji H., Kashiwakura Y., Ohmori T., Kuno A., Uchiyama S.. Glycosylation of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 6. Mol. Ther.Methods Clin. Dev. 2024;32(2):101256. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D. H., Bashir A., Sinai S., Jain N. K., Ogden P. J., Riley P. F., Church G. M., Colwell L. J., Kelsic E. D.. Deep Diversification of an AAV Capsid Protein by Machine Learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39(6):691–696. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-00793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J., Fakhiri J., Grimm D.. Fantastic AAV Gene Therapy Vectors and How to Find Them Random Diversification, Rational Design and Machine Learning. Pathogens. 2022;11(7):756–761. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11070756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy W., Huang S., He X., Zhou C., Heger C. D., Powers T. W., Anderson M. M., Sloan C., Lerch T. F.. Enabling IcIEF Peak Identification of AAV Capsid Proteins by Fractionation on MauriceFlex and Subsequent Analysis by LC-MS. Electrophoresis. 2025;46(1–2):22–33. doi: 10.1002/elps.202400201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.