Summary

Megacity coastal areas, under human activity pressure, are recognized as reservoirs of human pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). However, the dynamics and potential health risks under different anthropogenic stressors remain unclear. In this study, surface seawaters were sampled from Shenzhen’s western (SZW) and eastern (SZE) coasts, considering the influences of intensive population and industrial activities, as well as tourism and recreational activities. This study revealed distinct microbiomes and selective enrichments of heavy metals and ARGs in SZW and SZE areas, with correlations between most ARGs with intl1. The microbiome-ARG co-occurrence network of SZE was more complex, containing diverse human pathogens and ARGs, highlighting health risks even in low-population density recreational areas. Hub pathogens and ARGs may contribute to shaping these networks, and have the potential to serve as new indicators for different coastal human disturbances. These findings aid in developing strategies for urban coastal sustainability and mitigating antimicrobial resistance.

Subject areas: Aquatic biology, Microbiology, Molecular microbiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Different microbial loads, enriched HPBs, and ARGs were observed

-

•

HPBs in SZW and SZE exhibited distinct multi-antibiotic resistance characteristics

-

•

Different HPBs and ARGs shaped the microbiome-ARG co-occurrence networks

-

•

ARGs might serve as new indicators for human disturbances in coastal waters

Aquatic biology; Microbiology; Molecular microbiology

Introduction

Coastal areas serve as transitional zones between terrestrial and marine environments, with over 50% of the global population residing in these regions.1,2 These areas are recognized as reservoirs of pollution from anthropogenic activities. These pollutions originated from both land- and aquatic-based sources, such as litter from holidaymakers at beaches, industrial effluents, domestic sewage, waste carried by rivers, and contamination from merchant and oil ships.3 ARGs, distinct from chemical pollutants, are defined as genetic contaminants that can multiply by replication in microbial communities in specific ecosystems.4 The potential risk of ARG dissemination in neritic waters is theoretically higher than that in oceanic waters due to the significant impact of human activities.5 As a result, offshore ecosystems are considered to be seriously threatened by the prevalence of human pathogens and ARGs, particularly in megacities6,7 Furthermore, antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, antibiotic residues, and ARG elements are primarily transmitted to the environment via surface water.8,9 However, the role of anthropogenic activities in the microbial community assemblies, the occurrence of pathogens, and the characteristics of ARGs remain inadequately investigated in coastal surface seawaters of megacities.

Shenzhen, one of the fastest-growing metropolises situated on the coast of the South China Sea with 257.3 kilometers coastline and 1145 square kilometers sea area, was predominantly agricultural with a population of less than 20,000 before 1979.10 In recent decades, Shenzhen has undergone remarkable transformation, evolving into an advanced metropolitan conglomeration with a population over 13 million, characterized by cutting-edge industries, residential areas, and commercial establishments, and thriving tourism sector.11 Despite these advancements, the coastal ecosystems of Shenzhen face escalating pressures due to intense human activities.12,13 However, there is a lack of information on microbial assemblages and potential pathogens in the seawater along the shores of Shenzhen. Furthermore, there is a dearth of comprehensive understanding concerning the abundance and diversity of ARGs as well as their associations with correlated pathogenic taxa.

The sea area of Shenzhen is divided by the Kowloon Peninsula into two parts: a coastal plain in the west extending from the Lingdingyang Estuary to the Shenzhen River Mouth, and a coastal bedrock embayment in the east encompassing Mirs Bay and Daya Bay (Figure 1). May in Shenzhen typically marks the transition from the dry season (November–April) to the wet season (May–October). The extensive return of migrant populations after the Spring Festival in winter and tourism peaks later in summer, may markedly influence the dynamics of the microbiome and ARGs. This period avoids extreme weather events (e.g., summer typhoons) and aligns with moderate human activity. In this study, May 2021, Illumina NovaSeq sequencing, qPCR and geochemical analyses were employed to provides a single-timepoint snapshot of spatial variations in microbial communities, occurrences of human pathogens, and distribution characteristics of targeted ARGs in twelve surface seawater samples collected from two geographic zones: (1) five samples from western coastal sites impacted by dense population and industrial activities, and (2) seven samples from eastern sites primarily influenced by tourism and coastal recreational activities. The associations between ARG prevalence and environmental parameters, particularly with heavy metals, were further explored. Additionally, through network analysis, we comprehensively analyzed the relationships between ARGs and microbial communities, with special attention to the potential human pathogen presence. Our aim was to obtain a comprehensive understanding of microbial populations and ARGs in these two regions. This knowledge would be beneficial in directing efforts to predict human health risks, control pathogen and ARG pollution, and identify new indicators associated with different types of anthropogenic influences on coastal areas.

Figure 1.

Sampling sites in the Shenzhen coastal area

Sampling locations in Shenzhen's western and eastern areas were designated in rose red and blue, respectively (See Table S1 for detailed information).

Results

Physicochemical parameters of seawaters

To characterize the environmental variation of the surface seawaters between SZW and SZE coastal areas, environmental parameters characterizing water quality, dissolved nutrients, and heavy metal (HM) concentrations were measured. The results revealed significant disparities between sites in the SZW and SZE groups (Figure 2). Specifically, the salinity level, dissolved oxygen (DO), temperature and conductivity were significantly lower, while the concentrations of total nitrogen (TN), total phosphate (TP), NO2− and NO3− were higher in the SZW group than in the SZE (Figures 2A and 2B). Notably, a sample of site SZW4, a bustling seaside park of a shopping mall, exhibited maximum values for TN, NO2−, NO3−, and the second highest value for TP (Figure 2B; Table S1). Additionally, among the twelve tested HMs, the concentrations of Ti and Fe were significantly higher in samples from the SZE area, while Ni, V, Cr, and Cu presented much higher levels in the SZW area (Table S5).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of physicochemical properties in SZW (rose red) and SZE (blue) coastal seawaters

(A) Water quality parameters.

(B) Dissolved nutrients.

(C) Heavy metal concentrations.

(Data are presented as violin plots; Wilcoxon test; non-significant differences marked as n.s., p > 0.05).

Profiles of Shenzhen’s western and eastern microbiota

We performed individual profiling of bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities in twelve seawater samples to investigate the impact of two distinct anthropogenic activities on microbial populations. The bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic community profiling yielded a total of 1048820, 23179, and 845132 high-quality sequences, ranging between 80428 and 91549 (median 87488), 71 and 12478 (median 560), 61693 and 80213 (median 71647) sequences per sample, respectively. A total of 5522 bacterial, 186 archaeal, and 2331 eukaryotic OTUs were identified across all samples (Table S3).

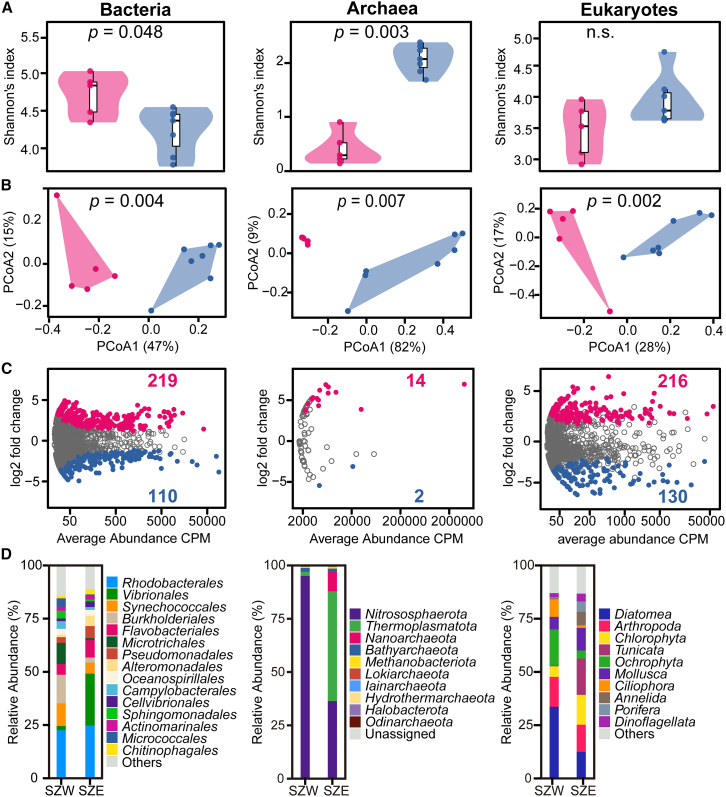

When comparing SZW and SZE samples, both alpha diversity and beta diversity exhibited significant differences. Regarding bacteria, the Shannon diversity was significantly higher in SZW samples compared to that of SZE. However, SZW samples exhibited lower Shannon indices for archaeal communities (p = 0.003), while no statistically significant difference was observed for eukaryotes (Figure 3A). Subsequently, we conducted principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Weighted UniFrac distances to compare bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities. The PERMANOVA test indicated significant differences among all three communities between SZW and SZE seawater samples, with distinct separation along axis 1 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The coastal seawaters of the SZW (rose red) and SZE (blue) areas harbor specific sets of microbiomes

(A) Violin plots depicting the Shannon diversity in the coastal seawaters of SZW and SZE sites (Wilcoxon test; non-significant differences marked as n.s., p > 0.05).

(B) PCoA based on Weighted UniFrac distances with PERMANOVA tests showing the microbial community patterns in seawaters of SZW and SZE sites.

(C) Volcano plots displaying the abundance patterns of the microbiota, highlighting the OTUs that were significantly enriched and depleted by SZW compared with SZE, as determined by differential abundance analysis (likelihood ratio test, p < 0.05, FDR corrected).

(D) The histograms of the relative abundances of microbial taxonomy between SZW and SZE samples.

To better elucidate the disparities between SZW and SZE microbiota that were strongly influenced by distinct anthropogenic activities, the differential OTU abundances were analyzed. In comparison to the SZE samples, the SZW samples exhibited a higher number of statistically significant enriched OTUs: 219 vs. 110 for bacteria, 14 vs. 2 for archaea, and 216 vs. 130 for eukaryotes (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the Venn diagrams demonstrated that the SZE samples possessed more unique OTUs in bacterial, eukaryotic and pathogenic bacterial communities (Figure S1).

The relative abundances of microbial groups in the SZW and SZE samples were further analyzed at different phylogenetic levels. The bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotic compositions were observed with distinct shifts (Figures 3D and S2). Overall, a total of 56 bacterial phyla, 138 classes, 345 orders, 572 families, and 1179 genera were identified. The bacterial community structures at the order level are displayed in Figure 3D (left), where Synechococcales, Burkholdderiales, Microtrichales, Campylobacterales, Spingomonadales, and Micrococcales were abundant in SZW samples. In contrast, Vibrionales. Flavobacteriales, Pseudomonadales, Alteromonadales, Cellvibrionaled, and Chitinophagales exhibited greater abundance in samples from SZE sites. Ten archaeal phyla were found across all samples, with the dominance of Nitrososphaeria and Thermoplasmatota, accounting for 97.6% of the total archaeal sequences. Remarkably, in SZW samples, the archaeal communities were dominated by Nitrososphaeria (95.1%) while Thermoplasmatota (51.5%), Nitrososphaeria (36.4%) and Nanoarcheaota (9.2%) comprised the majority of SZE samples (Figure 3D, middle). For eukaryotes, ten phyla were acquired. The SZW samples showed higher relative abundances of Diatomea, Ochrophyla, and Ciliophora, whereas Chlorophyla, Tunicata, Mollusca, Annelida, Porifera and Dinoflagellata were more abundant in SZE sites (Figure 3D, right).

Potential human pathogen contamination

Altered microbial communities in human-impacted marine environments can, in turn, have adverse effects on human health, such as the spread of pathogens and the development of antibiotic resistance. However, limited knowledge exists regarding the diversity and abundance of pathogenic microorganisms in coastal seawater. The pathogen database used in this study was compiled by integrating information from nine authoritative sources, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) priority pathogens list.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 Redundant entries were removed to ensure each pathogen was only represented once in the merged database. To address taxonomy inconsistencies, the nomenclature was standardized using the NCBI Taxonomy Database as a reference. The final database was validated against independent datasets and peer-reviewed literature to confirm its reliability. Through the quantification of 1048820 high-quality bacterial OTU reads, we identified 229479 HPB OTU reads belonging to 68 genera (Table S6).

The alpha-diversity analyses revealed that the diversity of pathogenic bacteria in SZW sites was significantly higher compared to SZE sites: the Shannon index values were markedly elevated in SZW seawaters (3.03 ± 0.24) as opposed to SZE samples (1.95 ± 0.55) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Distinct HPB assemblages of SZW and SZE seawater samples

(A) Violin plot of Shannon diversity of bacterial pathogens between SZW and SZE groups.

(B) PCoA plot of HPB variations between SZW and SZE groups.

(C) Volcano plot illustrates significantly enriched (rose red) and depleted (blue) HPB OTUs in SZW compared to the SZE group, as determined by differential abundance analysis.

(D) The composition and relative abundances of HPB genera in SZW and SZE samples.

(E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differentially abundant HPB OTUs between SZW and SZE groups.

The PCoA plot confirmed the distinct partitioning of pathogenic bacteria in SZW and SZE (Figure 4B). Furthermore, the volcano plot showed that the SZW group exhibited 25 enriched pathogenic OTUs, while the SZE group displayed 22 enriched pathogenic OTUs (Figure 4C). The Venn diagram showed a shared presence of 215 HPB OTUs (62%) between SZW and SZE, while exclusive OTUs accounted for 53 and 81, respectively (Figure S1D). As depicted in Figure 4D, a majority of the HPB OTUs found in sampled Shenzhen coastal seawaters were affiliated with Vibrio, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Acrobacter, Photobacterium, and Flavobacterium genera, accounting for 20.76% of total bacterial sequences. Interestingly, we observed higher ratios of HPB/bacteria abundances in SZE samples (5.90%–50.47%, median 32.32%) compared to the SZW group (3.09%–13.57%, median 8.81%). Notably, the Vibrio genus, which is the most abundant HPB genus discovered in the Shenzhen coastal area, exhibited dominance in the SZE samples with a relative abundance of 74.21%, whereas it accounted for only 22.91% in SZW areas. Acinetobacter, as the second-most prevalent HPB genus, showed higher prevalence in SZW samples (22.40%) compared to SZE (15%) (Figure 4D).

The differences in the composition of pathogenic bacteria communities between SZW and SZE were also analyzed based on specific differentially abundant HPB OTUs that were overrepresented in each community. Our result demonstrated that all enriched HPB OTUs in the SZE sample belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria, while in the SZW group, the enriched pathogenic OTUs exhibited greater diversity and were assigned to seven different bacterial classes (Figure 4E). Specifically, 29 OTUs, including Vibrio (18 OTUs), Acinetobacter (4 OTUs), and Photobacterium (3 OTUs), as well as one each of the Shewanella, Aeromonas, Coxiella, and Pseudomonas genera, showed higher abundance in SZW sites. On the other hand, 16 HPB OTUs assigned to Sutteralla (2 OTUs), Comamonas (3 OTUs), Mycobacterium (2 OTUs), Erysipelothrix (2 OTUs), Bacteroides (2 OTUs), and one each of the Sphingorhabdus, Treponema, Clostridium, Bergeyella and Parabacteroides genus displayed higher abundance in SZW sites (Figure 4E).

The fungal community of the twelve seawater samples exhibited a potential pathogen-to-overall fungi ratio of 1.87%. Eight fungal OTUs were identified for seven potential pathogenic genera (Table S6). However, no significant difference was observed in these OTUs between the SZW and SZE groups (data not shown). Overall, our findings suggest that the selective enrichment of HPBs is the common process shaping the pathogenic microbiota of Shenzhen coastal seawaters under different anthropogenic influences.

Screened antibiotic resistance genes in the seawater samples from Shenzhen coastal areas

In this study, the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes, as well as the presence of 14 commonly observed ARGs in the environment and the intl1 copy numbers, were quantified (Table S4). The results showed bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy numbers ranged from 3.83×106 to 4.51×107 and archaeal from 1.60×103 to 6.53×105 copies mL−1 seawater, respectively. However, no significant differences in cell abundances were observed between SZW and SZE sites (Figure 5A). Moreover, intl1 and 14 screened ARGs were detected in all seawater samples, indicating a widespread distribution of ARGs in the Shenzhen coastal area.

Figure 5.

Profile of the target ARGs in seawater samples collected from the coastal area of Shenzhen

(A) The copy numbers of bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes as well as the relative abundance of ARGs/intl1 genes detected by qPCR.

(B) Donut charts illustrate the proportion of screened ARGs detected in SZW and SZE coastal sites, categorized based on their conferred antibiotics.

(C) Linear regression curves show the correlations between individual and total ARGs with intl1. Only significant relationships are presented. Each dot represents a sample; gray-shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval.

(D) Heatmap of the correlations between ARGs/intl1 genes and HPB genera. Only genera significantly correlated with at least one ARG are shown (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01). The top heatmap illustrates the average composition percentage of each genus within the total quantified HPBs in SZW and SZE groups.

The absolute abundances of ARGs/intl1 in seawaters are depicted in Figure S3. The combined abundance of target genes was significantly higher in SZW samples compared to SZE samples, with the highest abundance observed in sample SZW5 at 3.29×107 copies mL−1 seawater. Among ARGs, there was several orders of magnitude variation in abundance levels, with sul1 exhibiting the highest median relative abundance across all collected samples (1.46 × 10−2 ARG copies/16S rRNA copies) (p < 0.05), followed by sul2, qnrS, tetO, and ermF, while mefA had the lowest value (Figure 5A). These findings suggest that the Shenzhen coastal sea may serve as an important reservoir for sul genes and therefore deserves more attention. The relative abundance values of qnrB, sul1, sul3, ermF, and ampC were significantly higher in SZW compared to SZE. Additionally, although not statistically significant from those of the SZE group, the average abundances of tetA, tetO, tetQ, sul2, ermQ, mefA, and aac(3)-IIa genes were all higher in SZW samples. In contrast, tetB and qnrS exhibited greater relative abundance in SZE than SZW (Figure 5A, p < 0.05). Among targeted ARGs, tetracycline resistance genes were dominant in seawater samples from Shenzhen’s western coastal area, accounting for 66.25% of the total abundance of ARGs in SZW sites. Compared to that, the proportion of ARGs involved in resistance to sulfonamides (65.08%) and quinolones (23.30%) was larger in the SZE group (Figure 5B).

Integrons play a crucial role in the horizontal transmission of ARGs among bacteria.23 It is widely reported that integrons often carry one or more ARG cassettes.24 Therefore, investigating the behavior of intl1 can provide insights into the potential dissemination of ARGs. In this study, the levels of intl1 in the Shenzhen coastal seawater were measured to assess the transferability of ARGs. The results revealed that the relative abundance of intl1 in SZW was approximately one order of magnitude higher than that observed in SZE (Figure 5A). The correlations between ARG occurrence and the relative abundance of intl1 were further analyzed, and 10 out of 14 tested ARGs and the total ARG abundances were found to be positively correlated with intl1 (Figure 5C).

We performed pairwise Pearson correlation analyses to assess co-occurrence patterns between HPBs and targeted ARGs. Statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05) were identified between 36 specific HPB genera and 14 ARG subtypes (Figure 5D), revealing distinct spatial patterns in AMR associations. In the SZW area, pathogenic genera with higher relative abundances (e.g., Arcobacter, Bacteroides, Porphyromonas, Erysipelothrix, Treponema, Alcaligenes, Sutterella, and Achromobacter) exhibited strong correlations with a broad spectrum of ARGs (8 subtypes and intI1). Flavobacterium, Roseomonas, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Peptococcus showed significant correlations with ampC, tetO, and sul2. In contrast, HPB genera enriched in SZE samples (e.g., those correlated with qnrS, tetB, and ermQ) were associated with fewer than two ARG subtypes, except for Aeromonas, which co-occurred with five ARGs (sul3, tetQ, mefA, aac(3)-IIa, and ermF). These spatial differences indicated that coastal waters in SZW may harbor a higher prevalence of bacteria correlated with multi-antibiotic resistance profiles.

Correlation analyses of environmental parameters and microbial compositions

To investigate the relationships between environmental factors and bacterial community, we considered both SZW and SZE microorganisms holistically. Seawater physicochemical properties, such as conductivity, salinity, DO, pH, NO2−, TP as well as tested HMs including Fe, Ti, V, Cr, Ni, Cu, and MeHg were identified as the primary factors influencing the distribution of the bacterial community. ARGs such as ampC, qnrS, sul1, sul2, tetA, and intl1 also showed significant correlations with the bacterial community variations. In addition, the Shannon indices were positively correlated with conductivity, concentrations of Fe, Ti, TP, and qnrS abundances (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pairwise comparisons between environmental parameters and community composition, as well as Shannon diversity of bacteria

Shannon index and community composition were correlated to each environmental parameter by partial Mantel tests.

Upon analyzing ARGs, it was noted that TN and HMs had significant influences. Fe and Ti had negative correlations with qnrB, sul1 and intl1, while demonstrating a favorable association with qnrS. Moreover, Cr showed a clear positive association with the presence of tetA, qnrB, sul1, ermF, and intl1. Pb exhibited significant positive relationships with ermQ, while Cu and Ni demonstrated positive correlations with tetO, sul2, and ampC. The correlation between ARGs indicates a synergism among resistance genes in the coastal area.

Assembly processes and co-occurrence patterns

The NST index was employed to quantify the relative importance of deterministic and stochastic processes in bacterial community assembly. Our results show that both the SZW and SZE communities had NST values above the 50% boundary point. This suggests that stochastic processes play a bigger role in shaping the coastal seawater ecosystem of Shenzhen. Specifically, a higher NST value of 65.23% in SZE communities was observed compared to an average of 53.72% in SZW communities (Figure S4A). Additionally, the bacterial community assembly process was analyzed using a neutral model based on R2 values (R2 = 0.729 to 0.876). Both the SZW (0.827) and SZE (0.830) areas showed high migration rates, highlighting the dominance of stochastic processes in community formation, consistent with NST analysis (Figure S4B).

In order to investigate the impact of different human activities on potential ecological interactions among whole microbial members and ARGs/intl1. Co-occurrence networks were separately constructed for SZW and SZE samples, and their properties were determined. The microbiome-ARGs/intl1 co-occurrence network at SZE sites (1,080 nodes and 3,348 edges) was surprisingly more complex than that at SZW sites (758 nodes and 947 edges) (Figure 7A). A higher average degree, average path length, graph density, and degree centralization were also obtained for the SZE network, while greater values of clustering coefficient and modularity were observed for the SZW network. The overwhelming majority of nodes in the top eight modules were bacteria and eukaryotes, and very few were archaea. The distribution patterns of ARGs and pathogens in the co-occurrence networks of the SZW and SZE microbial communities were further explored. The information regarding specific ARGs and pathogenic OTUs contained within each highly populated module is presented in Figure 7B. The SZW network modules encompass six HPB genera (11 OTUs), while the SZE modules include two eukaryotic pathogens (Malassezia and Aspergillus) as well as taxonomically diverse groups of HPBs (30 OTUs, 17 genera). In the SZE network, a total of 1L ARGs were identified, while only 6 ARGs were detected in the SZW network. Furthermore, different modules contain various pathogens and ARGs, with most of them being found in larger modules with high HPB percentages (>14%) (Figure 7B). Notably, Vibrio is the sole HPB detected across three modules within the SZE network. Additionally, sul3 and tetO were detected within co-occurrence modules of both SZW and SZE networks. The keystone taxa of the SZW microbial network were identified as two eukaryotic genera (Brettanomyces and Lachancea), uncultured Paracaedibacteraceae, Aquabacterium, as well as one pathogenic genus Flavobacterium. On the other hand, the identified keystone taxa (IN2411, Protodrilus, Arcocellulus, and Phyllodocida) of the SZE network all belonged to the eukaryotic domain. Given that the high connectivity of hub ARGs in different environments may facilitate their use as ARG indicators, in to our results, tetO and sul1 were recognized as the potential indicator ARGs of the SZW and SZE ecosystems, respectively, with their highest relative abundances and co-occurrence degrees, as well as maximum positive correlations with pathogenic OTUs (data not shown) in each network (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Co-occurrence patterns of microbial communities and ARGs/intl1 in seawater samples from SZW and SZE areas

(A) Co-occurrence networks visualizing significant and strong Pearson’s correlations (r > 0.7, p < 0.05) among bacteria, archaeal, eukaryotic OTUs, as well as ARGs/intl1 in SZW and SZE samples. Shaded areas represent the top eight most populated modules, microbial OTUs, and edges within different modules are highlighted by different colors.

(B) Defining network modules. Plots showing the number of OTUs in the top eight most populated modules for the SZW and SZE co-occurrence networks. Pathogenic OTUs of bacteria and eukaryotes are colored by their taxonomy at the genus level. Percentages on the x axis indicate the proportion of HPBs in bacterial OTUs present in each module.

(C) Degree of co-occurrence and abundance of OTUs and ARGs. Relative abundance of all OTUs (as counts per million, CPM) and detected ARGs from the SZW and SZE microbiome co-occurrence networks was plotted as a function of their degree of co-occurrence. Keystone OTUs and potential indicator ARGs have a yellow and orange background, respectively. Side panels recapitulate the distributions of co-occurrence degrees and abundance for the all pathogenic OTUs and ARGs compared to the density of all.

Discussion

Bacterial pathogens

While the identification of OTUs matching known human pathogens (HPB) is an important step in assessing potential health risks, it is crucial to recognize that actual health risks depend on multiple factors that cannot be determined from amplicon data alone. Viability, virulence gene expression, and infectious dose are critical determinants of pathogenicity and risk, and their assessment requires additional methodologies beyond those employed in this study.

The most prevalent pathogenic bacteria identified in our investigation were Vibrio, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Arcobacter. Similar dominance has been observed in other marine ecosystems.25,26 Arcobacter has recently gained attention as emerging pathogens,27 their association with sewage,28 food contamination,29 and illness in a variety of hosts29 was further confirmed in our results by their higher abundances within the HPB community in SZW sites compared to SZE sites (Figure 4D). Vibrio species are primarily responsible for diseases associated with natural aquatic microbiomes.30 The majority of newly reported infectious cases associated with coastal recreational waters are of non-enteric origin.31 In recent years, scientists have expressed concern over the rising trend of Vibrio-related wound infections linked to recreational seawater in the Northern European seas.32

In our study, a higher relative abundance of HPBs was observed in SZE samples compared to SZW sites, with Vibrio spp. being the predominant species (Figure 4D). However, this should be interpreted with caution, as the mere presence of HPB OTUs does not directly translate to active infection risk. Future studies incorporating metatranscriptomics and/or cultivation-based approaches would provide valuable insights into the functional activity and potential virulence of these microbes in the environment.

Traditionally, the microbiological monitoring systems employed to assess the quality of bathing waters are primarily based on quantifying bacterial indicators associated with fecal contamination, such as Escherichia coli and intestinal enterococci. These specific bacteria have been linked to cases of gastroenteritis resulting from coastal recreational activities.33 However, in our results, OTUs belonging to indicator taxa (E. coli and Enterococcus spp.) and to the families Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae were detected with small relative abundances in SZE (0.062%) samples that were influenced by human recreational activities (data not shown). Moreover, it has been reported that the presence and abundance of these indicator bacteria do not necessarily indicate the presence of human pathogens.34 It should be noted that relying solely on these fecal markers may not adequately predict the risk of illness caused by non-enteric bacteria implicated in skin, eye, ear, respiratory tract, and throat infections.35 Moreover, in our study, most potential multi-antibiotic resistant bacteria and highly connected key pathogenic taxa determined by the correlation and network analyses were non-enteric taxa (Figures 5D and 7). Our investigation suggests that the potential risk to human health posed by other pathogenic genera should not be disregarded, and necessitates the additional identification of non-enteric indicator organisms in these coastal recreational seawaters.

The assessment of health risks associated with coastal environments is complex and multifaceted. While the SZE region exhibits higher ARG diversity and a more complex microbial-ARG co-occurrence network, the SZW region shows higher ARG abundance and a broader range of enriched HPBs, including known multi-drug resistant genera such as Acinetobacter. These differences highlight the importance of considering multiple factors when evaluating health risks. ARG diversity may indicate a greater potential for horizontal gene transfer and the emergence of new resistance profiles, while higher ARG abundance and the presence of specific pathogens may pose more immediate risks. The concept of “health risk” in this study is defined by the potential for exposure to pathogens and ARGs, which can vary based on environmental conditions and human activities. However, it is crucial to note that actual health risks depend on additional factors such as the viability of pathogens, their virulence potential, and resistance to critical antibiotics, which require further investigation beyond the scope of this study.

Abundance and composition of antibiotic resistance genes

Several lines of evidence suggest that antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon; however, human activities have accelerated the dissemination of ARGs.36 A number of abiotic factors, such as antibiotic pollutants, organic chemicals, and heavy metals, contribute to the antibiotic resistance crisis.37 “Smart” bacteria can rapidly respond to anthropogenic disturbances by acquiring ARGs and subsequently surviving environmental stressors.38 Given that seawater is the home of an enormous number of microorganisms, the atypical presence of ARGs within microbial communities could be employed as a set of markers of anthropogenic influences and the pollution status in coastal areas.37,39,40

The results of our study clearly demonstrate the predominant presence of sul genes in each sampling site (Figure 5A and S3). These results are in line with earlier research that found that sul1 and sul2 are common in aquatic environments and have higher concentrations than other ARGs.41,42,43,44 The high levels of sul1 and sul2 reflect the extensive usage of sulfonamides in this region, highlighting their significant environmental risk.45

Intl1, which was more prevalent in polluted environments, was also detected in high abundance in our study. Intl1 is known to carry a wide range of ARGs and facilitate their transfer between different microorganisms.46 Our research further confirms significant correlations between intl1 and most of the detected ARGs, with tetA and sul1 showing the strongest correlation (r > 0.9, p < 0.001, Figure 5C). Previous studies have also reported positive correlations between sul1/sul2, tet genes, and intl1.44,47,48,49,50,51 However, no relationship was found between intl1 and other ARGs.52 Some previous studies have demonstrated that, compared to other mobile genetic elements, intl1 may exhibit enhanced propagation characteristics.53,54 Furthermore, some ARGs have been observed to co-occur with other ARGs due to their position on the same DNA fragment or within the same bacterial host.55,56,57 These findings indicate that both horizontal gene transfer and a shift in potential host bacteria play significant roles in influencing the abundance of ARGs on the Shenzhen coast.

We identified 36 HPB genera present in coastal water samples that exhibited positive correlations with multiple ARGs (Figure 5D). In the SZW group, pathogenic genera with higher relative abundances exhibited strong correlations with a broad spectrum of ARGs, suggesting potential associations between these pathogens and multiple antibiotic resistance profiles. However, it is important to emphasize that these correlations do not prove that the identified genera are direct hosts of the ARGs. Confirming host-ARG associations requires more advanced techniques such as metagenomic binning, single-cell genomics, or cultivation-based methods. Our findings serve as a foundation for future research to explore these potential relationships using these approaches.

Additionally, in our study, HMs such as Cr, Ni, Cu, and Zn showed positive relationships with multiple ARGs (Figure 6). Previous results have indicated that certain ARG types can be better explained by general factors such as Cu and Zn than by the corresponding antibiotics. Notably, heavy metals can serve as strong and long-term selective pressures on both heavy metal resistance genes (MRGs) and ARGs.39 Moreover, dissolved nitrogen concentration exhibited a positive correlation with most investigated ARGs, while water quality parameters, including pH, DO, conductivity, and salinity, showed a negative correlation with ARGs that were generally enriched in the SZW group (Figure 6). In a previous study, an intricate network was identified in three lakes in China, demonstrating both direct and indirect relationships among antibiotics, metals, environmental parameters, and ARGs.58 In addition, HMs such as V, Cr, Ni, and Cu had a significant effect on the variations of the bacterial community (Figure 6). Since most of the ARGs and MRGs are found on bacterial chromosomes, shifts in the microbial community will unavoidably affect related resistance genes. This study revealed potential connections among the seawater nutrition, microbial community, ARGs, and heavy metals, providing insight into the potential regulatory mechanisms of antibiotic resistance influenced by various factors. The significant correlations between several heavy metals and ARGs suggest potential drivers of ARG distribution or co-selection mechanisms. However, these correlations do not establish causality, and further investigation into the underlying mechanisms is required.

In our study, the distribution of ARG types is not the same across the functional zones, which suggests that they may have different sources. Notably, quinolone ARGs were mainly found at the SZE sites (Figure 5B). Sulfonamide and tetracyclines are predominantly applied in animal husbandry, while quinolones hold greater significance in human medicine,59 indicating that human recreational activities may be the main reasons for the occurrence of quinolone ARGs. While the relative abundance of ARGs was normalized against bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy numbers to account for differences in bacterial biomass, this approach does not account for variations in gene copy numbers among different bacterial taxa. Future studies could benefit from additional normalization strategies, such as referencing against genome equivalents or incorporating taxon-specific gene copy numbers, to further refine the quantification of ARGs.

Network analysis, potential indicators, and microbial community assembly

In our investigation, a network analysis approach was also employed to investigate the co-occurrence patterns between ARG subtypes and microbial taxa. Firstly, different properties were observed between the co-occurrence networks of SZW and SZE samples. The SZE group exhibited higher topological feature values compared to SZW (Figure 7A). According to Landi et al.,60 an increase in the complexity of the microbial network typically indicates enhanced ecological resistance and stability.60 The average path length and clustering coefficient are used to describe the communication among different members within a network.61,62 The SZW network exhibits a short path length and a high clustering coefficient, facilitating the rapid propagation of environmental perturbations. However, its higher modularity indicates increased susceptibility to environmental variations. Conversely, the SZE network exhibits a relatively longer path length, lower coefficient, and lower modularity, suggesting the robustness of the microbial community (Figure 7A). It is important to consider alternative interpretations. The greater complexity observed in the SZE network could also reflect more diverse interactions or niche partitioning within an environment that experiences less consistent anthropogenic stress compared to SZW. In contrast, the chronic and potentially homogenizing pressure in SZW, characterized by dense population and industrial activities, may lead to a more streamlined microbial community with fewer interaction types but stronger connections among key players. This could result in a network with lower complexity but higher modularity, as observed in our study.

Secondly, the co-occurrence patterns observed in ecological network analysis offer novel insights into the identification of key species within microbial communities, thereby revealing the underlying drivers governing microbial structural successions.63 These key taxa, highly interconnected within the network, significantly influence the microbiome.64 We observed that ARGs are predominantly distributed within modules characterized by high relative abundances of HPBs (Figure 7B). These key pathogenic taxa and ARGs have major roles in shaping these networks and might serve as new indicators for human disturbances in coastal waters, though this requires validation through metagenomic assembly or isolation. Notably, only the SZE network contained a module with pathogenic eukaryotic OTUs, specifically Malassezia and Aspergillus. Malassezia, an opportunistic pathogen associated with mild skin conditions, has recently been implicated in serious diseases such as Crohn’s disease and pancreatic cancer.65 Aspergillus, a major concern due to significant rates of azole resistance, predominantly causes severe infections in non-HIV patients.66 The presence of beach users appears to be correlated with the detection of these fungi in beach sand and waters,67 which could potentially serve as indicators of anthropogenic pollution during the bathing season.68 Surprisingly, despite the low population density and good water quality in comparison to SZW sites, a higher relative abundance of HPBs (Figure 4D), considerable concentrations of the majority of ARGs (Figure 5A), and a more intricate meta-occurrence network with more ARGs and pathogenic eukaryotes (Figure 7) were detected in SZE samples. Accordingly, future research on coastal pathogens should place greater emphasis on these microorganisms. These findings emphasize that the potential health risk associated with human pathogens and antibiotic resistance in the coastal recreational area should not be overlooked. While such networks provide insights into potential microbial-ARG interactions, further validation is required to investigate potential mechanisms underlying these co-occurrence patterns. It is worth noting that our risk assessment is limited to genetic potential; actual harm depends on pathogen viability, host exposure, and transmission pathways. Future work should integrate metatranscriptomics and epidemiological data to resolve these dynamics.

Potential biological indicators for different anthropogenic impacts and assembly processes

To monitor changes in coastal areas, developing reliable biological indicators specific to ecosystems influenced by human activities is essential. Examining individual microbial taxa and ARGs offers a unique perspective for identifying potential targets for further research. In aquatic systems, keystone taxa are more effective in explaining the turnover of microbiome composition compared to the collective influence of all taxa.69 These keystone taxa can be utilized for predicting community shifts or manipulating microbiome functionality.64

Regarding the identified keystone microorganisms in SZW samples, Flavobacterium has been recognized as a key degrader involved in the metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) found in chronically hydrocarbon-polluted canals and multiple polluted bays.70,71 Additionally, it exhibits a high metabolic capacity for nitrogen.72 The bacterium Aquabacterium has also demonstrated its potential as an oil-degrading microorganism with activity in hydrocarbon remediation.73 Fungal community are sensitive to various water contaminants and anthropogenic interferences in aquatic bodies, such as industrial and domestic wastes, petroleum hydrocarbons, heavy metals and eutrophication, making them a reliable bioindicator of environmental health.74 Within the SZW group, two eukaryotic keystone taxa, namely Brettanomyces and Lachancea. Brettanomyces has been detected in the beaches, possibly due to pluvial water runoff and discharge of domestic wastes along the beaches,75 while Lachancea has been employed as a bioindicator for assessing sewage contamination and eutrophication.76 In addition, ciliates (Ciliophora members IN2411, Protodrilus and Phyllodocida) and diatomea (Arcocellulus affiliated to order Mediophyceae) assemblages were identified as keystone taxa in the SZE samples (Figure 7C). The composition of ciliate assemblages at various beach conditions and their interactions with distinct beach categories are also reported to be influenced by the urbanization levels and anthropogenic-induced stressors.77,78,79 Therefore, ciliates were suggested to be incorporated into routine coastal monitoring programs.80 Moreover, diatoms are commonly employed for water quality monitoring and inferring past environmental conditions.81 The high prevalence of Mediophyceae in marine coastal areas might be attributed to their remarkable capacity for rapid adaptation to hydrographical fluctuations.82 The keystone taxa identified in this study should be viewed as potential indicators specific to the sampling period in May 2021. Their reliability as consistent ecological indicators across different seasons and environmental conditions requires further validation through longitudinal studies.

Previous results indicated that the distribution of ARGs in the environment was closely related to anthropogenic activities.83 Thus, these ARGs might offer valuable insights into the impact of different anthropogenic activities on the dissemination and proliferation of ARGs in the environment. However, limited information on using ARGs as new indicators for human disturbances in the coastal environment is available. Our findings suggested that in SZW and SZE coastal areas of Shenzhen, tetracycline ARG tetO and sulfonamide ARG sul1 may have the greatest potential to indicate the overall antimicrobial resistance contamination in waterbodies impacted by intensive population and industrial activities, as well as tourism and recreational activities, respectively (Figure 7C).

While tetO and sul1 demonstrated differential patterns and high network degrees in our study, their broader applicability and specificity as indicators of anthropogenic impacts require further context and validation. Previous studies have consistently linked sul1 to wastewater contamination and human fecal markers, supporting its use as a marker of anthropogenic pollution in marine environments.84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95Similarly, tetO has been identified as a potential indicator of multi-source pollution, particularly in environments impacted by various human-generated effluents, such as wastewater, industrial, agricultural, and domestic discharges.36,91,96,97,98 It also shows significant correlations with antibiotics and multiple indicator microorganisms.97 While our findings align with these previous studies in highlighting the prominence of sul1 and tetO in pollution-impacted environments, we also recognize the need for further validation to establish their reliability as indicators in different contexts. Future research should incorporate metagenomic assembly, experimental validation, and clinical relevance studies to confirm their utility as environmental biomarkers. Additionally, the integration of other known indicator ARGs, such as intI1 and qnrS, which have been extensively studied in coastal and wastewater environments, would provide a more comprehensive assessment of anthropogenic impacts.

In line with our findings, significant positive correlations had been observed between sul1 and wastewater nutrients such as chemical oxygen demand (COD), NH4+-N, TP, and TN92 (Figure 6). Furthermore, the discovery of multiple significant correlations between sul1 and other ARGs associated with different or identical resistance mechanisms suggest the genetic linkage driven by co-transfer and co-occurrence of these ARGs, ultimately leading to the emergence of co-resistance or multidrug resistance (Figure 6). The tetO gene, which exhibited the highest potential human health hazard, was ranked as the most significant risk to human health.99 Within a framework aimed at identifying indicator genes to monitor antibiotic resistance in wastewater, it exhibited complete sequence homology with diverse human pathogens, thus establishing its potential as a promising candidate indicator for ARGs.100 The present study also found good correlations of tetO concentrations to Ni and Cu, however, tetO did not correlate with any of the water-quality constituents (Figure 6), indicating that these metal variables had effects on the distribution of tetO in Shenzhen coastal seawaters.

In the present study, we are pioneering an investigation into the impact of anthropogenic influence on the assembly of microbial communities in seawater of a megacity. The findings indicate that a majority of bacterial taxa reside within the predicted neutral region, underscoring the significance of stochastic processes. This could be attributed to human-induced pollution altering physicochemical conditions in seawater, thereby potentially creating nutrient resources or serving as novel substrates that facilitate stochastic dispersal and colonization by microorganisms. Our results align with Chen et al.101 in highlighting the pivotal role of anthropogenic and environmental factors in structuring urban microbial communities and ARG profiles.101 While Chen et al.101 conducted a comprehensive study on the influence of diverse environmental and demographic factors on the urban microbiome, our study offered a complementary perspective by potentially revealing additional drivers or nuances that may operate at different scales.

Coastal systems are influenced by seasonality, episodic pollution events, and hydrological shifts, all of which may alter host-ARG associations, keystone taxa roles, and pollutant-microbe interactions.89,102 While our study provides a valuable snapshot of the microbial signatures and ARG profiles in the Shenzhen coastal areas, we recognize that the dynamic nature of these ecosystems may lead to variations in the observed patterns throughout the year. The differences, correlations, and proposed bioindicators identified in our study should be interpreted with the consideration of this temporal limitation. For instance, monsoon-driven rainfall (June–September) could amplify terrestrial runoff, altering nutrient loads and microbial communities in both regions.103 Similarly, tourist influx during summer might elevate fecal indicator bacteria, potentially masking the baseline differences observed here.104 Thus, the proposed bioindicators should be interpreted as preliminary candidates requiring validation across temporal gradients. Further studies with seasonal sampling would be necessary to fully capture the extent of these variations and to validate the consistency of the identified bioindicators across different periods.

Conclusions

The SZW and SZE coastal areas of Shenzhen, impacted by distinct anthropogenic activities of dense population and tourism, respectively, provided excellent habitats for investigating variations in microbial assemblages and the resulting health risks. This study provides a single-timepoint snapshot of the significant differences in the diversity and composition of microbial communities between these two areas, as evidenced by taxa compositions, community separation patterns, HPBs, and ARGs. SZW seawater samples exhibited a greater alpha-diversity of HPBs while SZE area had more abundant HPBs that were highly dominated by Vibrio species. 36 HPB genera were found to be potentially associated with multiple high-risk ARGs in both regions. The total abundances of the 14 target ARGs and intl1 were higher in SZW samples. Tetracycline and sulfonamide resistance genes were found to be the most abundant types of ARGs in SZW and SZE samples, respectively; quinolone resistance genes were mainly detected in SZE area. Furthermore, ten out of fourteen target ARGs showed significant correlations with intl1 gene presence indicating their potential for horizontal gene transfer. Surprisingly, the ARGs/intl1 -microbiome co-occurrence network of the tourism-impacted SZE group was more complex and contained more diversified human pathogens and ARGs, compared to that observed in SZW seawater ecosystem influenced by urban living and industrial activities. In addition, key pathogenic taxa and ARGs have major roles in shaping these networks and might serve as new indicators for human disturbances in coastal waters. Our findings shed light on the distribution of microorganisms and ARGs in seawaters under different human influences, as well as offer valuable insights into risk assessment and management strategies in megacity coastal regions.

Limitations of the study

This study investigated spatial variations in microbial communities and ARGs but did not account for seasonal dynamics, due to sampling at a single timepoint. Although the strong HPB-ARGs associations imply human-influenced zones may amplify multi-drug resistance risks, the observed correlations do not prove direct links between microbial communities and ARGs. Further genomic reconstruction and experimental validation are required to clarify these relationships.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Shan Yu (shanyu@pku.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The raw sequence data determined in this article have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive105 at the National Genomics Data Center,106 with accession number CRA015567, which is publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

-

•

This article does not report original code.

-

•

All relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the Guangdong Major project of Basic and Applied Basic Research Program (No. 2020B0301030003). We gratefully acknowledge Wenwei Xie, Hailin Yang, Xinxin Fan, and Xiaoming Zhao for their support in sampling.

Author contributions

Xindi Lu: resources, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, and writing-review and editing. Shan Yu: resources, conceptualization, project administration, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. Lijuan Zhang: investigation. Siwei Liu: visualization and writing-review and editing. Hailong Lu: conceptualization and funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw sequence data | This paper, Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center (NGDC, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa) | GSA: CRA015567 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| USEARCH 10 | Edgar107 | https://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual10/ |

| R (version 4.3.1) | R Core Team108 | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

There were no experimental models involved in the study. Only seawater samples were collected, filtered and immediately frozen for this study.

Method details

Study area and sampling locations

Shenzhen, a coastal megacity in South China, is adjacent to Hong Kong. Shenzhen Bay, Mirs Bay, Daya Bay and other big and important bays along the Shenzhen coastline are considered to be complex ecosystems that have been significantly impacted by anthropogenic activities including urban development, marine culture practices, overfishing, petrochemical industries and recreational activities.109 This study was conducted at twelve specific sites encompassing two distinct geographical sections: the densely populated and industrially active western coastal area (SZW) of Shenzhen and the eastern region (SZE) primarily influenced by tourism and coastal recreational activities (Figure 1; Table S1).

Sample collection and preparation

Twelve seawater samples were collected from the coastal waters of Shenzhen in May 2021. At each sampling site, 500 mL of seawater was collected at a depth of approximately 0.5 m using sterile Nalgene bottles (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and immediately transferred to the shore laboratory for further processing. Sequentially, the seawater samples were filtered through 0.22μm pore size polycarbonate filters (Millipore, USA) to retain cells, and then stored at −80°C until DNA extraction.

Determinations of water parameters

The water quality parameters including temperature (T), salinity, conductivity, dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH, were measured in situ using the YSI Professional Plus handheld multiparameter instrument (YSI Company, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). The concentrations of dissolved nutrients, such as NO3−, nitrite (NO2−), ammonium (NH4+) and total dissolved phosphorus (TP) were determined using a Hach DR/1900 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Hach Company, Loveland CO, USA). The concentrations of Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Fe, Co, Cd, Cr, Ti and V were analyzed by NexION 1000 ICP-MS (PerkinElmer, USA). The concentrations of Hg and MeHg were detected using the Total Mercury Manual System (MERX, Brooks Rand Labs, USA) following the USEPA Method 1631110 and Method 1630.111

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

The DNA extraction of each seawater sample was performed using the CTAB-based method.112 PCR targeting the V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA gene, as well as the V4 region of the 18S rRNA gene of eukaryotes, was performed. The primer pairs and experimental conditions for amplification are summarized in Table S2. High-throughput amplicon sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform with the PE250 strategy (Novogene, Beijing, China). The amplicon sequencing depth for all samples is summarized in Table S3.

According to our previous study, paired-end reads were processed using USEARCH v10.0.240 for length-trimming, quality-filtering and merging.107 Subsequently, operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were constructed at 97% identity using the “cluster_otus” command. Singletons were removed and taxonomy was assigned to the SILVA database release 138 using the “sintax” command.113 Moreover, sequences from multicellular organisms are likely detected with the 18S rDNA libraries. To focus on the microbial community, OTUs assigned to metazoan groups and unclassified eukaryotes were eliminated.

Quantifications of target genes

qPCR is a reliable technique for detecting and quantifying the concentration of gene fragments in complex environmental samples. Therefore, in this study, microbial 16S rRNA genes for archaea/bacteria, 14 screened ARGs and the horizontal gene transfer-related gene intl1 were quantified by qPCR system (Bio-Rad CFX96, CA, USA) with the standard curve method. The specific primers and qPCR operation details are listed in Table S4. In this study, six classes of ARGs were quantified, encompassing tetracyclines (tetA, tetB, tetO and tetQ), sulfonamides (sul1, sul2 and sul3), macrolides (ermF, ermQ and mefA), quinolone (qnrB and qnrS), aminoglycoside (aac(3)-IIa), and beta-lactamase (ampC), involved in five distinct antibiotic resistance mechanisms: efflux, inactivation, target replacement, target alteration, and target protection (Table S1). Quantification of target genes was conducted with plasmid DNA standard curves ranging from 102 to 108 copies/μL, following the pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems manual (Promega). The unit of ARGs in seawater samples was represented by “copies/mL”. Additionally, the relative abundance of ARG genes and intl1 was calculated by the equation:

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1).108 Alpha indices were calculated using the “vegan” package in R.114 Principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) was performed on Weighted Unifrac matrices using the R package “phyloseq.”115 Pearson correlations of the relative abundance of HPB genera and ARGs/intl1 was calculated using the R packages “psych”, and “ggpubr”, respectively.116,117 Differentially abundant HPB OTUs between SZW and SZE groups were determined by the Wilcoxon test (BH-adjusted p < 0.05). The neutral community model was employed to evaluate the impacts of random dispersal and ecological drift on bacterial community assembly, with R2 and m-values calculated using the R package “Hmisc”.118 R2 indicates model fit, and a higher m-value suggests less dispersal limitation among communities. The normalized stochasticity ratio (NST), calculated with the R package “NST”, differentiates more deterministic (<50%) from stochastic processes (>50%) using a 50% threshold.119

Significance testing for variations in environmental parameters, water quality, alpha indices, 16S rRNA gene copy numbers, as well as relative abundance of ARGs and intl1 between SZW and SZE groups were evaluated using the “ggsignif” package in R based on the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.120 Differences in microbial community structures between SZW and SZE areas were analyzed by the permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the R package “vegan.”114

Data visualization

Violin plots, scatter plots, histograms, box plots and donut charts were generated using the “ggplot2” package in R.121 Volcano plots were constructed using ‘edgeR' and heatmaps were generated using ‘pheatmap' in R.122,123 The Pearson correlations between environmental factors and ARGs/intl1, as well as their associations with Shannon index and bacterial community composition, were analyzed using the R package “linkET.”124

To comprehensively characterize the associations among microbial communities and ARGs/intl1, co-occurrence networks were constructed. Only OTUs present in at least sixty percent of the samples were selected for analysis. Pearson correlations among microbial OTUs and ARGs/intl1 were computed using the R package “WGCNA.”125 Only significant correlations (r > 0.7, p < 0.05) were visualized using the “igraph” package in R.126 The “cluster fast greedy” method was employed to perform clustering based on the coordinates of each node and reassign nodes accordingly. OTUs and ARGs/intl1 contained in the top eight most populated modules were displayed in column plots using R software. The keystone OTUs were separately identified for the SZW and SZE meta-networks based on the definition employed by a previous study. These OTUs were recognized as nodes within the top 1% of node degree values in each network.127 In addition, the potential indicator ARGs were identified as those with a relative abundance above −5 on the natural logarithmic scale (base e) and a node degree value exceeding 10 in each network.

Published: July 16, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113133.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Liquete C., Zulian G., Delgado I., Stips A., Maes J. Assessment of coastal protection as an ecosystem service in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2013;30:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J., Lu J., Zhang Y., Wu J. Microbial ecology might serve as new indicator for the influence of green tide on the coastal water quality: Assessment the bioturbation of Ulva prolifera outbreak on bacterial community in coastal waters. Ecol. Indic. 2020;113 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsagbey S.A., Mensah A.M., Nunoo F. Influence of Tourist Pressure on Beach Litter and Microbial Quality-Case Study of Two Beach Resorts in Ghana. West African J. Appl. Ecol. 2010;15 doi: 10.4314/wajae.v15i1.49423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanderson H., Fricker C., Brown R.S., Majury A., Liss S.N. Antibiotic resistance genes as an emerging environmental contaminant. Environ. Rev. 2016;24:205–218. doi: 10.1139/er-2015-0069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H., Wang Y., Liu P., Sun Y., Dong X., Hu X. Unveiling the occurrence, hosts and mobility potential of antibiotic resistance genes in the deep ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;816 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Y.G., Zhao Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Zhang S.Y., Yu S., Chen Y.-S., Zhang T., Gillings M.R., Su J.Q. Continental-scale pollution of estuaries with antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu J., Zhang Y., Wu J. Continental-scale spatio-temporal distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in coastal waters along coastline of China. Chemosphere. 2020;247 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heberer T. Occurrence, fate, and removal of pharmaceutical residues in the aquatic environment: a review of recent research data. Toxicol. Lett. 2002;131:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marti E., Variatza E., Balcazar J.L. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam K.C. Environment and development in Chinese special economic zones: The case of Shenzhen. Sci. Total Environ. 1986;55:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng T., Xu N. Satellite-Based Monitoring of Annual Coastal Reclamation in Shenzhen and Hong Kong since the 21st Century: A Comparative Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/jmse9010048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y., Wang Y. River water quality degradation in Shenzhen City and its influencing mechanisms. China Rural Water Hydropower. 2007;7:11–13. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y., Zhu W., Le M., Lu X. Temporal and spatial variations of heavy metals in urban riverine sediment: An example of Shenzhen River, Pearl River Delta, China. Quat. Int. 2012;282:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2011.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez-Jarreta J., Amos B., Aurrecoechea C., Bah S., Barba M., Barreto A., Basenko E.Y., Belnap R., Blevins A., Böhme U., et al. VEuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52:808–816. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ecker D.J., Sampath R., Willett P., Wyatt J.R., Samant V., Massire C., Hall T.A., Hari K., McNeil J.A., Büchen-Osmond C., Budowle B. The Microbial Rosetta Stone Database: a compilation of global and emerging infectious microorganisms and bioterrorist threat agents. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsberg K.J., Patel S., Gibson M.K., Lauber C.L., Knight R., Fierer N., Dantas G. Bacterial phylogeny structures soil resistomes across habitats. Nature. 2014;509:612–616. doi: 10.1038/nature13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health and Safety Executive. The Approved List of biological agents Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens. https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/misc208.pdf.

- 18.Kembel S.W., Jones E., Kline J., Northcutt D., Stenson J., Womack A.M., Bohannan B.J., Brown G.Z., Green J.L. Architectural design influences the diversity and structure of the built environment microbiome. ISME J. 2012;6:1469–1479. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littman R.A., Fiorenza E.A., Wenger A.S., Berry K.L.E., van de Water J.A.J.M., Nguyen L., Aung S.T., Parker D.M., Rader D.N., Harvell C.D., Lamb J.B. Coastal urbanization influences human pathogens and microdebris contamination in seafood. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B., Zheng D., Zhou S., Chen L., Yang J. VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:912–917. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wattam A.R., Abraham D., Dalay O., Disz T.L., Driscoll T., Gabbard J.L., Gillespie J.J., Gough R., Hix D., Kenyon R., et al. PATRIC, the bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:581–591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou M., Johnston L.J., Wu C., Ma X. Gut microbiota and its metabolites: Bridge of dietary nutrients and obesity-related diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023;63:3236–3253. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1986466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandi S., Maurer J.J., Hofacre C., Summers A.O. Gram-positive bacteria are a major reservoir of Class 1 antibiotic resistance integrons in poultry litter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7118–7122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306466101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriques I.S., Fonseca F., Alves A., Saavedra M.J., Correia A. Occurrence and diversity of integrons and beta-lactamase genes among ampicillin-resistant isolates from estuarine waters. Res. Microbiol. 2006;157:938–947. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leight A.K., Crump B.C., Hood R.R. Assessment of fecal indicator bacteria and potential pathogen co-occurrence at a shellfish growing area. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y., Stoeck T., Forster D., Ma Z., Zhang L., Fan X. Environmental status assessment using biological traits analyses and functional diversity indices of benthic ciliate communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;131:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramees T.P., Dhama K., Karthik K., Rathore R.S., Kumar A., Saminathan M., Tiwari R., Malik Y.S., Singh R.K. Arcobacter: an emerging food-borne zoonotic pathogen, its public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control–a comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2017;37:136–161. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2017.1323355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher J.C., Levican A., Figueras M.J., McLellan S.L. Population dynamics and ecology of Arcobacter in sewage. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girbau C., Guerra C., Martínez-Malaxetxebarria I., Alonso R., Fernández-Astorga A. Prevalence of ten putative virulence genes in the emerging foodborne pathogen Arcobacter isolated from food products. Food Microbiol. 2015;52:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalvaitienė G., Vaičiūtė D., Bučas M., Gyraitė G., Kataržytė M. Macrophytes and their wrack as a habitat for faecal indicator bacteria and Vibrio in coastal marine environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023;194 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammed R.L., Echeverry A., Stinson C.M., Green M., Bonilla T.D., Hartz A., McCorquodale D.S., Rogerson A., Esiobu N. Survival trends of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Clostridium perfringens in a sandy South Florida beach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012;64:1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Böer S.I., Heinemeyer E.-A., Luden K., Erler R., Gerdts G., Janssen F., Brennholt N. Temporal and Spatial Distribution Patterns of Potentially Pathogenic Vibrio spp. at Recreational Beaches of the German North Sea. Microb. Ecol. 2013;65:1052–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez I.L., Díaz C.Á., Díaz J.L.G., Cortezón J.A.R., Juanes J.A. The European bathing water directive: application and consequences in quality monitoring programs. J. Environ. Monit. 2010;12:369–376. doi: 10.1039/b903563j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noble R.T., Fuhrman J.A. Enteroviruses detected by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction from the coastal waters of Santa Monica Bay, California: low correlation to bacterial indicator levels. Hydrobiologia. 2001;460:175–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1013121416891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Napier M.D., Haugland R., Poole C., Dufour A.P., Stewart J.R., Weber D.J., Varma M., Lavender J.S., Wade T.J. Exposure to human-associated fecal indicators and self-reported illness among swimmers at recreational beaches: a cohort study. Environ. Health. 2017;16:103–115. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen B., Liang X., Huang X., Zhang T., Li X. Differentiating anthropogenic impacts on ARGs in the Pearl River Estuary by using suitable gene indicators. Water Res. 2013;47:2811–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q., Na G., Zhang L., Lu Z., Gao H., Li R., Jin S. Effects of corresponding and non-corresponding contaminants on the fate of sulfonamide and quinolone resistance genes in the Laizhou Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;128:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen B., Yang Y., Liang X., Yu K., Zhang T., Li X. Metagenomic profiles of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) between human impacted estuary and deep ocean sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:12753–12760. doi: 10.1021/es403818e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo F., Li B., Yang Y., Deng Y., Qiu J.W., Li X., Leung K.M., Zhang T. Impacts of human activities on distribution of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes and antibiotic resistance genes in marine coastal sediments of Hong Kong. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016;92 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su J., Huang F., Zhu Y. Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment. Biodiversity Sci. 2013;21:481–487. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang L., Hu X., Xu T., Zhang H., Sheng D., Yin D. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes and their relationship with antibiotics in the Huangpu River and the drinking water sources, Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;458–460:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo Y., Mao D., Rysz M., Zhou Q., Zhang H., Xu L., JJ Alvarez P. Trends in antibiotic resistance genes occurrence in the Haihe River, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:7220–7225. doi: 10.1021/es100233w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo Y., Xu L., Rysz M., Wang Y., Zhang H., Alvarez P.J.J. Occurrence and Transport of Tetracycline, Sulfonamide, Quinolone, and Macrolide Antibiotics in the Haihe River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:1827–1833. doi: 10.1021/es104009s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niu Z.G., Zhang K., Zhang Y. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the coastal area of the Bohai Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016;107:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bean D.C., Livermore D.M., Papa I., Hall L.M.C. Resistance among Escherichia coli to sulphonamides and other antimicrobials now little used in man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:962–964. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pruden A., Arabi M., Storteboom H.N. Correlation between upstream human activities and riverine antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:11541–11549. doi: 10.1021/es302657r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J., Su Z., Dai T., Huang B., Mu Q., Zhang Y., Wen D. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the sediments of the East China Sea bays. J. Environ. Sci. 2019;81:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillings M.R. Integrons: past, present, and future. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014;78:257–277. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00056-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L., Dechesne A., He Z., Madsen J.S., Nesme J., Sørensen S.J., Smets B.F. Estimating the transfer range of plasmids encoding antimicrobial resistance in a wastewater treatment plant microbial community. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018;5:260–265. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Partridge S.R., Tsafnat G., Coiera E., Iredell J.R. Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:757–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y., Liu W., Xu C., Wei B., Wang J. Antibiotic resistance genes in lakes from middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, China: effect of land use and sediment characteristics. Chemosphere. 2017;178:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma Y., Wilson C.A., Novak J.T., Riffat R., Aynur S., Murthy S., Pruden A. Effect of Various Sludge Digestion Conditions on Sulfonamide, Macrolide, and Tetracycline Resistance Genes and Class I Integrons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:7855–7861. doi: 10.1021/es200827t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heuer H., Smalla K. Manure and sulfadiazine synergistically increased bacterial antibiotic resistance in soil over at least two months. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byrne-Bailey K.G., Gaze W.H., Kay P., Boxall A.B.A., Hawkey P.M., Wellington E.M.H. Prevalence of sulfonamide resistance genes in bacterial isolates from manured agricultural soils and pig slurry in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:696–702. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00652-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson T.A., Stedtfeld R.D., Wang Q., Cole J.R., Hashsham S.A., Looft T., Zhu Y.G., Tiedje J.M. Clusters of antibiotic resistance genes enriched together stay together in swine agriculture. mBio. 2016;7:e02214-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02214-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li B., Yang Y., Ma L., Ju F., Guo F., Tiedje J.M., Zhang T. Metagenomic and network analysis reveal wide distribution and co-occurrence of environmental antibiotic resistance genes. ISME J. 2015;9:2490–2502. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tacão M., Moura A., Correia A., Henriques I. Co-resistance to different classes of antibiotics among ESBL-producers from aquatic systems. Water Res. 2014;48:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohore O.E., Addo F.G., Han N., Li X., Zhang S. Profiles of ARGs and their relationships with antibiotics, metals and environmental parameters in vertical sediment layers of three lakes in China. J. Environ. Manage. 2020;255 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Czekalski N., Sigdel R., Birtel J., Matthews B., Bürgmann H. Does human activity impact the natural antibiotic resistance background? Abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in 21 Swiss lakes. Environ. Int. 2015;81:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landi P., Minoarivelo H.O., Brännström Å., Hui C., Dieckmann U. Complexity and stability of ecological networks: a review of the theory. Popul. Ecol. 2018;60:319–345. doi: 10.1007/s10144-018-0628-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou J., Deng Y., Luo F., He Z., Tu Q., Zhi X. Functional Molecular Ecological Networks. mBio. 2010;1:e00169-10. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00169-00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]