Abstract

Background:

Evidence-based treatments for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) include behavioral treatment and psychostimulants, preferably in combination. Research on the treatment of ADHD underscores a gap in the literature regarding the optimal sequencing of treatments (Pelham, Jr. & Altszuler, 2020). Emerging evidence supports starting with behavioral treatment before psychostimulants, though the mechanisms of this sequencing effect are not entirely understood.

Objective:

This study explores one plausible mechanism—that psychostimulants reduce behaviors targeted by behavioral treatment, thereby reducing opportunities for children to learn and practice self-regulation skills. The article reports post hoc findings from a triple-masked, AB/BA crossover study, conducted in the Summer Treatment Program (STP).

Method:

Two-hundred forty-eight children diagnosed with ADHD; 77% male; 85% Hispanic) were randomized to receive either (a) intensive behavior therapy plus medication (“COMB”) or (b) intensive behavior therapy plus placebo (“BT”) for 3 weeks, then crossed over to the other condition for 3 weeks. Behavior in recreational settings was systematically recorded and analyzed as a function of medication status and order of treatments.

Results:

We found evidence that initial medication reduced the efficacy of subsequent behavior therapy. That is, children exhibited significantly more misbehaviors when unmedicated if they started with combined treatment, then had medication withdrawn, than if they started with behavior therapy alone.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that starting with a combined treatment approach had an unintended adverse impact on children’s behavioral functioning when medication was withdrawn. The results support current clinical recommendations, which are to start treatment of ADHD with behavior therapy alone and to add medication as necessary.

Keywords: ADHD, methylphenidate, behavior treatment

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common mental health disorders affecting elementary-aged children in the U.S. (Danielson et al., 2018). ADHD-associated functional impairments include conflicts with parents and teachers as a result of difficulty completing tasks independently, poor interactions with peers (Hoza et al., 2005; Pelham & Bender, 1982), and low academic achievement and behavior problems in school (DuPaul & Jimerson, 2014; Loe & Feldman, 2007). Children with ADHD account for the vast majority of behavior problems in elementary school setting (Harrison et al., 2013) and are the most common behavioral referral to school and outpatient mental health providers (Anderson et al., 2015; Barkley et al., 2006; DuPaul & Stoner, 2014).

A voluminous literature has clearly demonstrated that behavioral treatment (BT; behavioral classroom management and behavioral parent training), medication with a central nervous system stimulant (MED), and the combination of the two (COMB) are effective short-term treatments for ADHD but are limited in their long-term effects (Barkley, 2014; DuPaul & Stoner, 2014; Evans et al., 2018; Fabiano et al., 2009; Greenhill et al., 2002; Group, 1999; Kass et al., 2015). It is important to highlight that these treatments improve children’s behavior in different ways. That is, behavioral treatment stems from social learning theory and operant learning, which posit that children learn appropriate behavior over time via consistent positive and negative reinforcement which, when implemented consistently, significantly reduce behavior concerns in these children at school (i.e., getting out of seat, blurting out answers) and at home (i.e., defiance; Forehand et al., 1979). Over time, as adults in a child’s environment (e.g., parents and teachers) use these strategies, children develop the skills necessary to reduce inappropriate behavior (e.g., blurting out answers, not waiting turn, refusing to comply with adult requests, requiring repeated reminders to complete tasks) and increase appropriate behavior (e.g., raising hand, waiting turn, completing tasks the first time asked). In contrast, stimulant medication, the most commonly employed evidence-based treatment for ADHD, works by dramatically reducing disruptive behavior and increasing on-task behavior through its effects on the central nervous system, thereby reducing the need to teach the child how or why to behave in certain ways. Importantly, while stimulant medication produces acute effects in reducing symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention, there is no residual benefit of medication on behavior once its therapeutic effect wears off.

A critical question for the field is whether behavioral interventions or pharmacological interventions in isolation or in combination result in the best outcomes for children with ADHD. The literature has many examples of short-term studies of concurrent multimodal treatment compared to one or the other component (see Pelham, Jr. & Altszuler, 2020). These studies typically show that children treated with combined pharmacological and behavioral intervention show greater effects of acute intervention compared to children who receive unimodal MED or BT and that this result is obtained with lower “doses” of treatment compared to MED or BT alone. The primary finding of a well-known randomized clinical trial concluded the combination was not significantly better than medication alone (e.g., see MTA Group, 1999). However, an alternative interpretation (Pelham, 1999) and secondary analyses (Conners et al., 2001; Swanson et al., 2001) support a combined treatment approach. It has also been established that lower doses translate into fewer side effects with MED and to lower cost with BT interventions (Fabiano et al., 2007; Pelham et al., 2014). That is, combined treatment at a low dose significantly reduces behavioral concerns shown by children with ADHD, resulting in current treatment guidelines recommending combined treatment as the preferable course of treatment for elementary-aged children (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019). However, despite combined treatment being the current consensus on the most effective treatment for these children, there is relatively little research regarding how best to implement combined treatments. That is, is it better to begin a child’s treatment with medication and later add behavioral treatment, or better to start with the opposite sequence, or is it perhaps better to implement the treatments simultaneously? And finally, are there iatrogenic effects of combining or sequencing treatments?

Several studies have begun to answer these questions. Pelham et al. (2016) recruited a sample of 152 children with ADHD (ages 5–12), and initially randomly assigned the children to one of two treatments using an adaptive SMART design: low-dose medication for school hours only (MedFirst) or low-intensity behavioral intervention consisting of behavioral parent training and school consultation (BehFirst). If participants were rated by teachers as needing additional treatment, they were then rerandomized to a secondary treatment arm: either (1) increased dose of the original treatment to which they had demonstrated insufficient response or (2) addition of the other treatment to make a combined treatment condition. A couple of critical findings resulted from this study. First, children who were assigned to BehFirst had significantly fewer rule breaking behaviors in the classroom at the end of the school year (IRR = 0.65, p < .01) compared to children assigned to MedFirst. In addition, parents of children who received medication first participated in parent training significantly less than parents of children who received behavioral intervention first. Specifically, 75% of families assigned to behavioral intervention first attended all 9 parent training sessions, while only 20% of the parents whose children were prescribed medication first met that criterion. In other words, parents whose children began treatment with medication did not obtain meaningful participation in the important parenting part of the intervention, which was essential to back up the teacher’s use of classroom behavioral management strategies. Overall, this study suggests that the sequencing of treatments influences not only the child’s behavior, but also has important implications for the behavior of important adults in the child’s life. Nevertheless, the study design did not include a combined treatment arm in the first randomization. As such, it limits our ability to conclude whether starting with combined treatment first and then switching to MED or BT only would have differentially impacted behavior outcomes.

Another study that has examined the impact of ADHD medication on the uptake of behavioral treatment is Waxmonsky et al. (2019). Insurance claim data were analyzed for youth with ADHD (N = 827,396). Children for whom medication prescriptions were filled were significantly less likely to use behavior therapy (odds ratio [OR] = .39, p < .001). Of concern, this association held true independent of age; even children under the age of 6 were significantly less likely to receive behavior therapy if medicated, despite treatment guidelines recommending behavior therapy as the first line of treatment for this age group (Wolraich et al., 2019).

Despite the large literature regarding the short-term effectiveness of both behavioral and pharmacological treatment for ADHD, strikingly there is limited evidence supporting long-term benefits of either of these interventions. Consequently, most children with ADHD have serious functional impairments that continue into adulthood (Altszuler et al., 2016; Hechtman et al., 2016; Merrill et al., 2019; Pelham III et al., 2020), and no studies have supported a preventive impact of either of these treatments on children’s functional outcomes (e.g., academic and vocational achievement, social relationships). For example, one of the most well-known studies of intervention for ADHD, the MTA study (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999), showed robust, short-term effects of interventions in elementary-aged ADHD children. Unfortunately, any beneficial effect that was observed from the behavioral, pharmacological, or combined interventions dissipated entirely by the 2-year follow up (Hechtman et al., 2016; Molina et al., 2009; Molina et al., 2023; Swanson et al., 2018). The question is why do these interventions not have long term positive impacts on children receiving them?

There are several potential explanations as to why standard treatments may not produce lasting impacts over the course of the child’s life. One is that most providers are recommending a sequence of treatments that do not promote necessary skill development to target a child’s functional impairment and may inadvertently reduce the likelihood that the adults in the child’s life will have the opportunity to implement strategies to positively shape the child’s behavior. Another is that tolerance to medication or habituation to reinforcement may emerge and undermine an effective treatment. It is estimated that 90% of children with ADHD are prescribed stimulant medication (Danielson et al., 2018). While psychostimulants produce acute behavioral improvements (e.g., decreased hyperactivity) in most children with ADHD, of concern, is that its use may also reduce the likelihood that parents and teachers will use behavioral strategies that actually teach the child appropriate behavior long term. Furthermore, most children who receive pharmacological treatment choose to discontinue treatment by adolescence, with the average length of stimulant use treatment being 2 years (Lichtenstein et al., 2012; McCarthy et al., 2009). Thus, the window of opportunity in childhood during which children could learn self-regulatory and adaptive skills may be undermined by using psychostimulants alone or in combination with behavioral interventions across home and school settings as first-line intervention.

In sum, additional research is needed to comprehensively understand the best sequencing of treatments and potential long-term effects. While prior work has started to answer critical questions in the sequencing of EBTs, much remains unanswered. For example, Pelham and colleagues (2016) found that starting with BT alone can drastically reduce the need and dose of MED, and conversely, being randomized to MED first reduced the subsequent uptake and use of BT strategies. Nonetheless, an important question that remains unanswered is whether starting with best practice combined treatment (COMB) can potentially undermine the efficacy of BT.

The current study used a triple-masked, within subject, AB/BA crossover trial design to investigate the order effect of treatment post-hoc within the context of an intensive BT program (STP; Pelham et al., 2017) and has two goals. First, we sought to understand whether children have better outcomes when they start with behavioral intervention only (BT alone) or when they start with combined behavioral and pharmacological treatments (COMB). We hypothesized that children who started with BT and then switched to COMB treatment would show lower rates of inappropriate behavior during the unmedicated (BT) condition compared to children who started with COMB treatment and then received BT alone. Second, we investigated whether either treatment protocol produced an unintended adverse effect on children’s behavior.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and forty-eight children with ADHD (77% boys, 85% Hispanic), between the ages of 5–12 (M = 8.1, SD = 1.8) who attended a therapeutic summer camp (Summer Treatment Program (STP); Pelham et al., 2017) between the years 2013–2016 were included in this study (refer to Table 1 for demographic and diagnostic information). Participating children were enrolled in a clinical trial funded by the National Institute of Mental Health examining tolerance to stimulant medication (MH099030), which was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (now WCG IRB). At study entry, ADHD diagnosis was confirmed by two Ph.D./M.D.-level clinicians according to best practice recommendations (Pelham et al., 2005) and included independent review of parent and teacher ratings of DSM-IV symptoms (i.e., the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Scale; Pelham et al., 1992) and cross-situational impairment (Impairment Rating Scale; Fabiano et al., 2006), as well as a structured parent interview (NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children–IV, computerized version; Shaffer et al., 2000). If there was a diagnostic disagreement between clinicians, a third Ph.D.-level clinician reviewed the case, and a majority vote was used to determine the diagnosis. Exclusion criteria for the larger clinical trial included (a) Full-Scale IQ below 80; (b) taking psychotropic medication for conditions other than ADHD or active medical or psychiatric conditions that could be worsened by stimulants; (c) documented adverse response to methylphenidate stimulant medication or a failed trial of sustained release methylphenidate at full therapeutic doses; or (d) concurrent diagnosis of DSM-IV autism or Asperger’s disorder as stimulants have been found to have a reduced efficacy and tolerability in this population (Rupp, 2005). Youth with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), or a mood or anxiety disorder were allowed to enroll if they did not require emergent treatment (e.g., mania, active suicidal ideation).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Study Entry

| Variable | Full Sample (N =248) | Placebo First (n=132) | Medication First (n=116) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age in years | 8.1 (1.8) | 8.1 (1.9) | 8.1 (1.8) |

| Female | 23 % | 21% | 24% |

| White | 88% | 85% | 92% |

| Black | 11 % | 15% | 6% |

| Hispanic | 85 % | 81% | 89% |

| Estimated full-scale IQ | 96.7 (12.7) | 96.9 (13.1) | 96.8 (12.8) |

| Medication Dosea | 20.8 (5.7) | 20.2 (4.3) | 21.8 (6.3) |

| Diagnosed with ADHD | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Combined Subtype | 73.8 % | 74.4% | 73.0% |

| Predominantly Impulsive/Hyperactive Subtype | 8.1 % | 8.3% | 7.8% |

| Predominantly Inattentive Subtype | 18.1 % | 17.3% | 19.1% |

| Diagnosed with ODD | 63.5 % | 63.9% | 62.9% |

| Diagnosed with CD | 10.2 % | 9.2% | 11.3% |

| Number of ADHD impulsivity/hyperactivity symptoms endorsed on DBD-RS | 7.4 (2.2) | 7.42 (2.1) | 7.3 (2.1) |

| Number of ADHD inattention symptoms endorsed on DBD-RS | 8.4 (1.3) | 8.52(1.1) | 8.2 (1.4) |

| Number of ODD symptoms endorsed on DBD-RS | 4.7 (2.7) | 4.64 (2.6) | 4.7 (2.7) |

| Number of CD symptoms endorsed on DBD-RS | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.97 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.2) |

Note. IQ = intelligence quotient, ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder, CD = Conduct Disorder, DBD-RS = Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale.

daily medication dose in mg.

Values are means with standard deviations in parentheses, or proportions (%) for binary variables. Estimated full-scale IQ based on Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 2011). Diagnoses were made at study entry as described in text. For symptom counts, symptom was counted as endorsed when either parent or teacher rated the symptom as occurring “pretty often” or “very often” on the DBD-RS (Pelham et al., 1992).

Setting

The study was conducted within the STP, an intensive 8-week behavioral intervention program for children with ADHD and related disorders. Children attended the STP for 9 hours per day on weekdays, during which they participated in 2 hours of academic lessons and participated in group recreational activities for the remainder of the day (e.g., skill drills, sport games, recess). Children were placed groups of 12 to 14 with same-aged peers and were supervised by a lead counselor and five to six paraprofessional undergraduate counselors who were supervised by permanent Ph.D.-level staff members. STP staff members implemented the standard STP behavioral intervention during 8-weeks of the program (Pelham et al., 2017). STP behavioral intervention consists of several components including a point system in which children earn points for appropriate behaviors (e.g., compliance, following activity rules) and lose points for inappropriate behaviors (e.g., negative verbalizations, rule violations) that are commonly targeted in children with disruptive behaviors. The behavioral intervention also includes standard activity rules and procedures, time out for serious inappropriate behaviors (e.g., aggression, destruction of property), and frequent social reinforcement (e.g., praise) for appropriate behavior. The behaviors for which the children earned points included: (1) following activity rules; (2) good sportsmanship; (3) complying with commands; (4) helping peers; (5) sharing with peers; (6) contributing to group discussions; (7) ignoring disruptions, provocations, and insults; and (8) demonstrating attention to ongoing events. The behaviors for which the children lost points included: (1) violating activity rules; (2) poor sportsmanship; (3) physical aggression; (4) destruction of property; (5) noncompliance with adult commands; (6) stealing; (7) lying; (8) verbally abusing staff members; (9) name calling or teasing other children; (10) cursing; (11) interrupting; (12) complaining or whining; and (13) leaving the activity area without permission (Pelham et al, 2017).

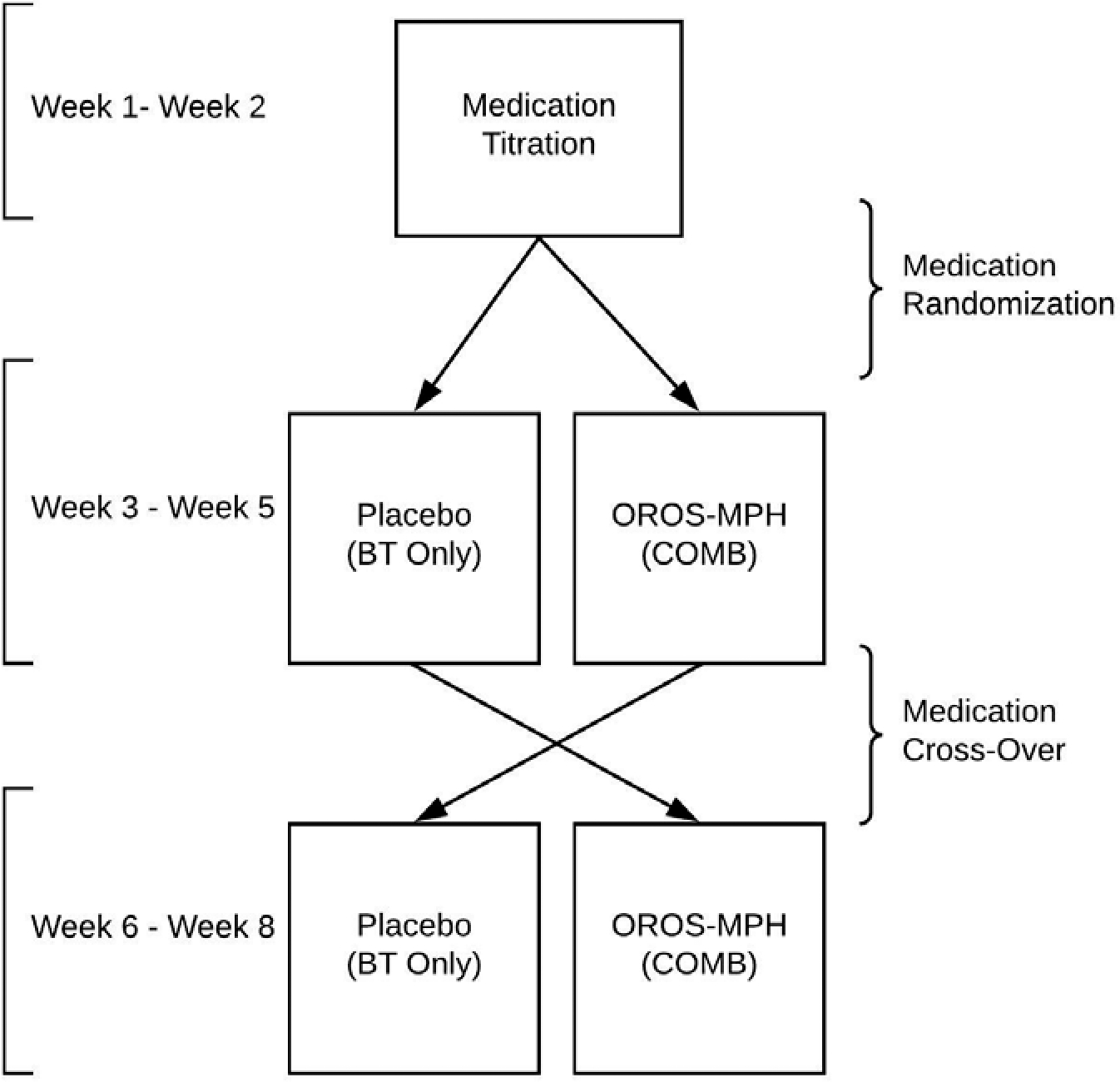

Design

A triple-masked, AB/BA crossover design was used, which allowed us to evaluate the effect of sequencing treatment (i.e., starting BT only versus COMB) on objective measures of children’s behavior (see Figure 1). As part of the clinical trial (MH099030) designed to investigate tolerance to stimulant medication, children participated in 2-week long dose titration trial, followed by a randomized order of OROS-MPH/placebo over the remaining 6 weeks. Children were randomized to take OROS-MPH or a placebo each morning for three weeks (weeks 3–5) and were then crossed to the other condition for the final three weeks of STP (weeks 6–8). All children received standard behavior treatment during the 8-week program. The current study evaluates the effect of randomizing the order of treatment over the remaining 6 weeks of the summer program on behavioral indices (described below).

Figure 1. Study Design.

Stimulant Medication

Children underwent a triple-masked controlled assessment of up to three doses of OROS-MPH (Concerta) for 9 days. Children attended the STP unmedicated for the first day, and then received a randomized schedule of low, moderate, and high dose – approximately 0.15 mg/kg (3 days), 0.3 mg/kg (3 days) and 0.6 mg/kg (3 days), respectively. Three Ph.D./M.D.-level clinicians reviewed behavioral data to determine the optimal OROS-MPH dose for each child, the lowest dose that produced substantive efficacy in children’s behavior compared to placebo. In total, 76% of children were assigned 18 mg, 19% of children were assigned 27 mg, and 4% of children were assigned 36 mg. Children received a mean daily dose of 20.8 mg (SD = 5.7 mg). The average titrated dose would be considered low compared to the titration in the MTA (Greenhill et al., 2001) or to routine clinical titration in the community. Side effects to stimulant medication were monitored via parent and STP staff report using the Pittsburgh Side Effect Rating Scale (Pelham, 1993). Parents were instructed to administer medication to their child at home before 7:30 am and to record the time medication was administered on a medication card that was collected daily at the STP. If a parent did not administer the medication, the medication was administered by study medical staff at the STP. Except for the medical team, STP clinical staff members, caregivers, and children were masked to medication status.

Dependent Measures

Counselor-recorded point-system behaviors.

Throughout the day, counselors recorded the frequencies with which the children exhibited the behaviors targeted by the point system (Pelham et al., 2017), and sum scores for each behavior category were totaled each day. Consistent with past research conducted within the STP, the following positive point system categories (1) percentage of rule following (%), (2) good sportsmanship, (3) behavior bonus (4) compliance, (5) helping, and (6) sharing as well as negative point system categories were used as dependent measures: (a) rule violations, (b) adult-directed noncompliance, (c) interrupting, (d) conduct problems (i.e., lying, stealing, destruction of property, and aggression), and (e) negative verbalizations (i.e., verbal abuse to staff, teasing peers, and swearing). These measures have been shown to be reliable and sensitive to medication effects in many previous studies (e.g., Altszuler et al., 2019; Pelham et al., 1990, 1999, 2000; Pelham & Hoza, 1987). In addition, minutes in time out served as a dependent measure. Children were assigned a time out as consequence for serious inappropriate behavior (i.e., repeated noncompliance, intentional aggression, intentional destruction of property). Time outs were implemented using an escalating/de-escalating procedure, such that the length of the time out was escalated if a child behaved inappropriately and was reduced if a child behaved appropriately. For children who escalated to the maximum allotted time, due to continuous negative behavior during time out, a contingent release procedure was followed, such that children were required to exhibit no negative behaviors for the last minute (ages 5–6) or 2 minutes (ages 7–12) for time out to end (see Fabiano et al., 2004 for evaluation of time out procedures at the STP).

Treatment and Procedure Integrity and Fidelity

Staff members underwent a two weeklong intensive training prior to the start of STP to learn manualized behavioral treatment procedures described in the STP Manual (Pelham, Greiner, & Gnagy, 2012). At post-training, and every week thereafter at STP, staff members completed weekly quizzes, in which they were expected to reproduce definitions of point-system behaviors verbatim as well as describe behavior management procedures based on vignettes of behaviors that are commonly exhibited at STP. In addition, in-vivo reliability evaluation of behavior management procedures were conducted by independent observers. These procedures have been employed for other medication trials conducted at STP and are described elsewhere (Helseth et al., 2015). Reliability observations were conducted on 29.5% of the available recreation periods, sampled across groups, sports, and days. Three children from the group were randomly selected and were observed independently for a 60-minute period. Observers independently coded and recorded behaviors exhibited by those three children. Point-system reliability for behavioral categories were determined by computing correlations between the counselors and the independent observer. Correlations averaged .73 across counselor-recorded point-system behaviors. Compliance with medication conditions was close to 99.9%, with children missing doses only on days in which they were absent from the summer program.

Analytic Plan

We used R (R Core Team, 2020) with glmTMB package (Brooks et al., 2017) to fit generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMM) and used ggplot2 and sjPlot packages for data visualization (Lüdecke, 2021). As recommended (i.e., Coxe et al., 2009), estimated models were specified to reflect a negative binomial distribution (“family = nbinom2”) given that all point-system behavior outcomes in the present study were count, had right-skewed distribution, and were overdispersed. Due to the outcome variable ‘minutes in time out’ having a zero-inflated distribution, this outcome was estimated using a zero-inflated Poisson distribution (“family = poisson”). Count outcome behavioral data were collected daily, such that repeated measurements of behavioral data were nested within each child. Therefore, random intercept only models were composed of two-levels, in which child was at the highest level (level-2) and the series of repeated count measurements (i.e., behavioral data) at the lowest level (level-1). As the observed outcome variables were nested within each child, each outcome variable of interest was regressed on a random intercept for each subject, and the following variables for fixed effects: (a) randomization to order of BT first vs. COMB first, (b) current medication status (c) and the interaction between randomization order (BT first, COMB first) and medication status (placebo/OROS-MPH).

Missing Data.

Full information maximum likelihood was used to accommodate missing data as missingness was infrequent <8% across point-system outcomes. Data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR) as missing values were explained by children’s absence from the STP (e.g., planned vacation, sick day). Estimated models included all children (N = 248) since maximum likelihood estimation can account for missing values at one or more occasions.

Results

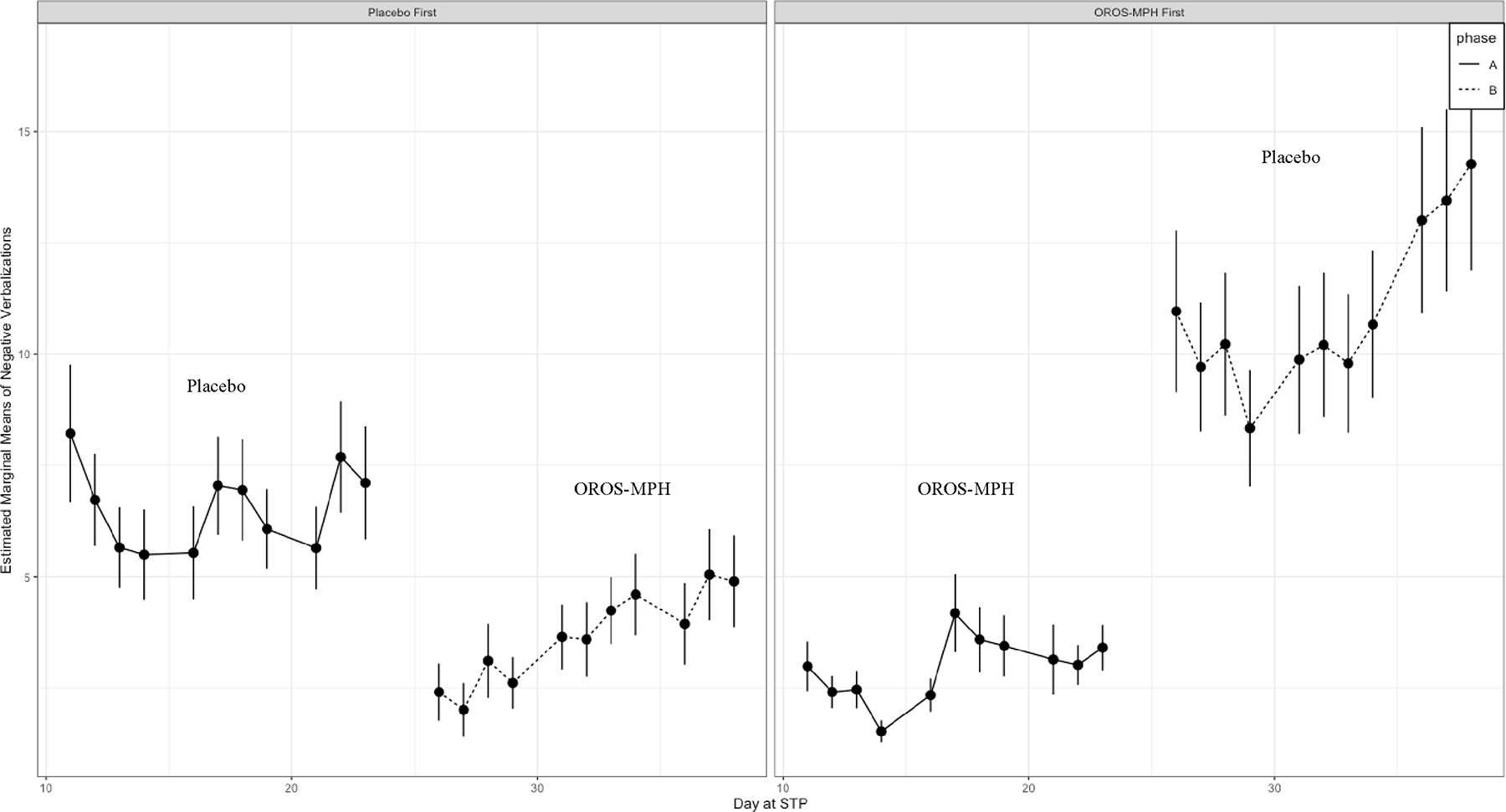

We fitted generalized linear mixed models to predict rates of point-system behavior (e.g., noncompliance, negative verbalizations) with medication status (i.e., MPH, placebo) and order of treatment sequence (BT or COMB first) (formula: DV ~ medication status * treatment order + 1 | subject). Standardized parameters were obtained by fitting the model on a standardized version of the dataset and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) and p-values were computed using the Wald approximation. Table 2 reports means and standard deviations, Table 3 summarizes model results, and Figure 2 graphs the results of negative point-system categories. Results from positive point-system categories were uniformly ns and are reported in Supplement 1).

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Dependent Measures

| Placebo |

OROS-MPH |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Phase | Second Phase | First Phase | Second Phase | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Complaining | 4.5 (8.3) | 6.9 (16.5) | 3.1 (7.1) | 3.1 (6.1) |

| Conducta | 2.5 (13.2) | 3.5 (13.5) | 0.6 (2.8) | 0.9 (3.9) |

| Interruption | 8.4 (11.9) | 9.4 (14.9) | 4.8 (9.1) | 3.8 (5.5) |

| Minutes in Time Out | 9.1 (27.1) | 15.7 (41.4) | 4.1 (15.3) | 3.8 (13.5) |

| Negative Verbalizations | 7.0 (15.3) | 13.5 (30.3) | 3.2 (9.8) | 4.4 (15.9) |

| Noncompliance | 3.5 (5.9) | 4.8 (8.5) | 2.2 (4.4) | 2.0 (4.3) |

| Rule Violations | 32.4 (66.7) | 40.3 (68.2) | 17.3 (34.7) | 15.5 (22.1) |

Note. Raw data are presented in the form of means (standard deviation in parentheses). Rates are average daily frequency counts.

Conduct variable includes aggression toward staff/peer, intentional destruction of property, stealing, and lying.

Table 3.

Generalized Linear Mixed Models of Observable Behaviors

| Conduct | Interruption | Minutes in Time Out | Negative Verbalizations | Noncompliance | Rule Violations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p |

| Med Order | 1.61 | 0.97 – 2.66 | 0.065 | 0.98 | 0.70 – 1.38 | 0.925 | 1.54 | 0.70 – 3.36 | 0.281 | 1.66 | 1.12 – 2.45 | 0.011 | 1.24 | 0.89 – 1.74 | 0.207 | 1.14 | 0.91 – 1.43 | 0.240 |

| Med Status | 0.46 | 0.38 – 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 0.42 – 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 0.40 – 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.46 – 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.48 – 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.51 – 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Med Order * Med Status | 0.58 | 0.45 – 0.75 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 1.20 – 1.44 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.61 – 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.55 – 0.71 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.87 – 1.11 | 0.781 | 0.99 | 0.92 – 1.06 | 0.741 |

Note. IRR = Incidence Rate Ratio; Med Status: 0 = Placebo, 1 = OROS-MPH; Med Order: 0 = Placebo First, 1 = OROS-MPH First.

Figure 2. Effect of Medication Order on Negative Verbalizations in STP Recreational Setting.

Note. Solid line represents Phase A (weeks 3–5); Dashed line represents Phase B (weeks 6–8) of STP.

Medication Effect.

As expected, the main effect of medication status (MPH, Placebo) was statistically significant across all point-system measures (p < .001), such that children had significantly lower rates of negative point-system behaviors when taking MPH compared to when taking a placebo. Next, children’s rate of negative point-system behavior when assigned to MPH did not differ based on the randomized order in which children received MPH (p = ns), indicating that children’s behavior when receiving OROS-MPH was comparable regardless of whether they were assigned to MPH (COMB) first or second. However, the randomized sequence order in which children received treatment (COMB versus BT first) greatly impacted variability in children’s unmedicated behavior (Placebo) across negative point-system indices.

Order Effect on Observed Behavior.

The cross-over interaction between medication status and the order in which children received treatment was statistically significant for negative point-system categories, including negative verbalizations (IRR = 0.63, 95% CI [0.55 – 0.71], p < .001), interruptions (IRR = 1.31, 95% CI [1.20 – 1.44], p < .001), conduct problems (IRR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.45 – 0.75], p < .001), and minutes spent in time out (IRR = 0.64, 95% CI [0.61 – 0.67], p < .001) but not for rates of noncompliance (p = 0.781) nor rule violations (p = 0.741). As shown in Table S1, we were unable to detect an order effect on positive-point system categories. Though between group differences for rates of conduct behaviors and interruption were statistically significant, these differences were not clinically meaningful due to small effect size. In contrast, mean comparisons showed that children who started on COMB treatment first and then switched to BT had twice as many negative verbalizations during BT condition (M= 13.53, SD= 30.30) compared to children who were randomized to receive BT first (M= 7.02 SD = 15.30) and then switched to COMB treatment for the last 3 weeks of the STP. Similarly, COMB first group exhibited higher rates of complaining (M = 6.86, SD = 16.52) when unmedicated compared to BT first group (M = 4.49, SD = 8.25). In addition, children who were assigned to COMB treatment first and then switched to BT, on average spent 73% more time in time out (M = 15.67, SD = 41.39) during the last 3 weeks of the program compared to children who received BT first (M= 9.06, SD = 27.09). In summary, the randomized sequence order in which children received treatment (COMB versus BT first) greatly impacted variability in children’s negative point-system behavior in the BT only condition across point-system indices.

Discussion

The current study sought to answer two questions. First, whether it is better to start with behavioral interventions for children with ADHD or combined interventions (i.e., behavioral and pharmacological treatment). Second, we investigated whether either treatment protocol produced an unintended adverse effect on children’s behavior. Using a triple-masked AB/BA design in which staff members, caregivers, and participants were masked to medication status, we collected direct observation of children’s behavior in the STP recreational setting across two 3-week blocks. The study design allowed for within subject and between-group comparisons to determine whether the order in which children received well-established treatment for ADHD led to differences in observed point-system behavior. Results indicate that (1) children’s behavior was better managed with a combination of BT and MED (COMB), regardless of the order in which treatments were assigned, (2) initiating treatment using BT first protocol and adding stimulant medication after (COMB) was the optimal treatment protocol, and (3) in contrast, initiating treatment with a COMB protocol resulted in unintended adverse outcomes once MED was withdrawn on negative behavior of children with ADHD. Each of the findings will be discussed in turn.

The current results show substantial reductions in problematic behavior among children who underwent a combined treatment approach involving intensive behavioral therapy (BT) and medication (COMB). Children’s medicated behavior was comparable and independent of the medication treatment order (COMB first vs COMB second). Specifically, COMB treatment protocol resulted in lower rates of negative point-system behaviors compared to BT alone. These findings replicate the extensive literature on the single and combined effects of BT and medication (e.g., Fabiano et al., 2008; Pelham et al., 2007) and support current treatment guidelines that recommend a combined treatment approach rather than either modality alone.

In addition to investigating the single and combined effects of BT alone and in combination with medication, the present findings report on treatment order effects, namely starting with BT alone or using a combined (COMB) treatment approach from the onset. Results showed that starting with three weeks of BT and then adding stimulant medication for the last three weeks resulted in significantly lower rates of misbehavior compared to when the children were on BT alone. These findings support recent studies by Chronis et al. (2004) and Pelham et al. (2016) that recommend behavioral treatment as a first-line intervention and adding medication, as needed. It is important to note that for a subset of children, BT alone was sufficient in managing their behavior when implemented as a first-line intervention protocol for the first three weeks of the program. However, the study design did not allow participants to remain on initial treatment even when an appropriate response was shown. Nevertheless, other studies that have utilized a Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) study design to examine treatment sequencing effects have found that starting with BT first can delay or eliminate the subsequent need for medication. In contrast, children who received COMB treatment first exhibited up to twice as many rule-breaking behaviors, such as negative verbalizations, when their active medication was withdrawn and switched to a placebo (BT alone) during the last three weeks of the program compared to children who started on BT alone. These findings suggest that the order in which children received treatments significantly affected their unmedicated behavior, as evidenced by several indices of social behavior. It is possible that the COMB first treatment protocol had an unintended adverse effect on children’s behavior when used as a first-line treatment. By reducing the frequency of disruptive behaviors, opportunities for staff to implement behavioral strategies to address inappropriate behavior were also reduced (i.e., if a child is interrupting less frequently, there are fewer learning opportunities during which a child engages in an impulsive behavior, a staff member labels the behavior as interrupting, and staff then administers a consequence in the form of point loss, and the child subsequently attempts to regulate themselves to avoid further point losses by raising their hand or waiting to speak). Furthermore, because the medication in the COMB protocol is temporarily managing behavior, there are fewer problem behaviors occurring in general. As a result, opportunities for practicing and utilizing behavioral strategies that effectively teach the child to manage their behavior are dramatically reduced. Consequently, this undermines children’s ability to learn self-regulation strategies to manage their own behavior. These findings suggest that the concurrent use of stimulant medication may have hindered the effectiveness of behavioral treatment on reducing disruptive behaviors in these children.

In summary, results indicate that OROS-MPH (COMB) treatment produced an acute beneficial effect in the reduction of behavior problems. Given that the frequency of disruptive behaviors was reduced, there were that many fewer opportunities for counselors to implement behavioral strategies intended to modify inappropriate behavior, which in turn prevented children from learning to self-regulate their behavior. In other words, these children did not benefit as much from the behavioral treatment because of the concurrent administration of stimulant medication. Thus, it appears that there may be a bidirectional relationship between staff members and child behavior that ultimately influences the rate of negative child behaviors during the placebo phase. For instance, due to medication eliminating most negative behaviors, staff members would have fewer opportunities to provide corrective feedback during the combined treatment phase, thereby reducing the opportunity for children to learn self-regulatory skills. It is also possible that medicated children were perhaps not accustomed to receiving as much corrective feedback from staff, which could explain the increase in negative behavior during the placebo phase. As such, the effectiveness of medication during the combined treatment phase may have precluded an opportunity for children to experience a behavioral extinction burst. Therefore, children’s negative behavior may increase as they receive higher rates of corrective feedback once they switch to behavioral treatment only (placebo) compared to when they were medicated (COMB treatment), such that the order in which children receive BT versus COMB treatment impacts their behavioral response.

Limitations & Future Directions

Although these results extend the literature on the sequencing of evidence-based treatments for ADHD, study limitations should be considered. First, this was a post hoc analysis of a trial designed to study tolerance to stimulants, and thus requires replication with a priori hypothesis testing. Second, while the STP is an ideal setting that allows for the manipulation of various treatments, it is a highly controlled setting where staff members receive extensive training delivering a manualized BT program (Pelham et al., 2017). Therefore, to determine the robustness of findings, replication is needed in a less controlled setting and implemented by adults whose BT skills are more consistent with real-world conditions (implementing low dose of behavior intervention, including a daily report card at school and/or weekly behavior parent training to address behaviors at home). Additional study limitations are related to the study design itself. For example, the cross-over AB/BA design undercuts our ability to determine whether time or children’s baseline behavior could partly explain differences between group unmedicated behavior. Of note, there was no between group differences in parent- and teacher- ratings of children’s symptoms at study entry (DBD-RS; Pelham et al., 1998) . Last, the study design precluded our ability to assess for the potential sequence effect of starting with MED only and then adding BMOD. Nevertheless, this sequence order has been evaluated in prior work (i.e., Pelham et al., 2016) and has been found to produce worse outcomes when compared to BMOD first and adding MED as necessary.

Several questions remain. This study was funded by an NIH grant to investigate tolerance to stimulant medication (MH099030, Examining Tolerance to CNS Stimulants in ADHD, PD/PI W. Pelham, J. Swanson, and J. Waxmonsky, 2012). Acute tolerance appears to occur each day after medication is administered (Swanson, et al., 1999), and this grant proposal hypothesized long-term tolerance may build-up and undermine effective treatment due to consistent use of stimulant medication (Pelham, Swanson, and Waxmonsky, 2012). An alternative to the proposed hypothesis described herein (i.e., reduced efficacy associated with reduced opportunities to learn and practice self-regulation skills) could be based on proposed long-term tolerance (i.e., iatrogenic effects associated with carry-over tolerance that may emerge during the “medication-first” condition and may endure over time for an equal or longer duration after medication is stopped). However, this alternative hypothesis was beyond the scope of the current study and its findings will be reported elsewhere. Next, future research should examine whether the sequencing of behavioral treatment and medication depends on the dosages of treatment or the settings in which they are delivered. Additional research is also needed to understand the potential long-term effects of sequencing medication. While stimulant medication is prescribed to 90% of children with ADHD, more often than not, children stop taking medication later on for a variety of reasons (McCarthy et al., 2009). For example, Brinkman and colleagues (2017) found in 12-year MTA follow-up, participants reported discontinuing medication at 13.3 years old, with the most self-reported reason being no longer needing medication or a lack of perceived effectiveness. Further, most participants (68.8%) endorsed the item stating, “I was tired of taking it”. Moreover, participants of longitudinal studies have reported experiencing comparable rates of functional impairment regardless of medication status, thereby raising the question of the effectiveness of long-term use of medication (Swanson et al., 2019; Volkow et al., 2003). Indeed, children with ADHD often continue to experience symptoms and related impairment that impact educational and vocational attainment, financial stability, and interpersonal relationships (Altszuler et al., 2016; Barkley et al., 2008; Hechtman et al., 2016; Merrill et al., 2019; Pelham et al., 2019). Thus, it is important to clarify why children fare worse off when starting with combined treatment but eventually withhold medication as a part of their treatment plan.

Another limitation to the present study is that data on parent behavior were not collected, including how treatment sequencing impacted parent’s management of their child’s behavior at home and the level of fidelity in implementing behavioral strategies taught in the behavior management training portion of the STP. Prior work suggests that parents of children who start treatment with medication do not utilize BPT services to an adequate degree (Coles et al., 2020). Further, their study revealed that children who received behavioral treatment delayed adding medication treatment by 13 weeks on average and were half as likely to initiate medication at all. If they did require medication, the dose needed was significantly lower than the group that did not receive BCM. Future work should focus on understanding the mechanism of this association, such as perception of utility of services, need for behavioral health services, convenience, cost, etc.

Clinical Implications

These results are consistent with some guidelines (e.g., SDBP, NICE), which recommend starting with behavioral treatment first and adding stimulant medication as necessary, but contradict other treatment guidelines (e.g., AACAP) that recommend starting with medication only or combined treatment (Pliszka et al., 2007). In current utilization practices, medication serves as the first-line monotherapy for most elementary-aged children with ADHD, while psychotherapy is reported to be added over time for approximately one-third of treatment regimens (Schein et al., 2022). Based on prior work (e.g., Coles et al., 2014; Pelham et al., 2016), a child’s treatment course that starts with medication first would similarly, and perhaps, even more drastically, undermine subsequent uptake and use of behavior treatment strategies – this provides a direct contrast to AACAP guidelines recommending cycling through multiple pharmacological treatments prior to adding BT (Pliszka et al., 2007). Findings from the current study suggest that, in the short-term, sequencing treatment should begin with behavioral treatment and then add medication for optimal treatment effects. These results provide preliminary justification for a priori hypothesis testing in a future clinical trial. Further, longitudinal work is also needed to determine the long-term benefits of such sequencing.

These results also have important implications for public health and education policy. Because ADHD is not designated as a Special Education category, children are often classified as Other Health Impaired or other categories by way of comorbid diagnoses (e.g., Emotional Disturbance, Specific Learning Disability). Although children with ADHD account for approximately 60% of children receiving special education services (Schnoes et al., 2006; Wagner & Blackorby, 2002), few evidence-based interventions are included in Individualized Education Plans for youth with ADHD (Spiel et al., 2014). As such, children with ADHD are less likely to receive the proper evidence-based behavioral treatments in classroom settings. Furthermore, school districts may require a visit to their doctor in order to qualify for special education services. Generally, medical doctors are primarily trained to provide support in one way –medication – and receive little training in recommending specific behavioral interventions. In contrast, doctors who would prefer to prescribe a combined treatment approach find themselves limited by the shortage of behavioral health providers. Thus, receiving pharmacological treatment as unimodal intervention is likely for these families. If children with ADHD are beginning their treatment with medication, the window of opportunity to learn important skills may be missed. This is especially concerning because typically by adolescence most children stop taking medication (Brinkman et al., 2018; McCarthy et al., 2009; Swanson, 2019). Therefore, no lasting treatment impacts will be sustained when opportunities to learn to self-regulate could have happened in early childhood or during elementary school. When youth cease medication, they are left with limited skills to help them navigate the impairment that often continues into adolescence and adulthood (Altszuler et al, 2016; Barkley et al., 2008; Hechtman et al., 2016; Merrill et al., 2019; Pelham et al., 2019).

Taken together with prior research, these results highlight the need for a more integrated, multidisciplinary treatment approach where behavioral health providers, physicians, and teachers work together to ensure the recommendation and provision of optimal treatment for each individual child. These results add to the growing evidence that beginning with behavioral treatment has a number of positive outcomes including reducing costs for schools and parents and lowering the likelihood of needing medication (Coles et al., 2020; Pelham et al., 2016). This study also provides additional support for the guidelines outlined by Barbaresi et al., (2020) for the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, indicating that behavioral and educational approaches should be implemented at the outset.

Supplementary Material

Funding source:

This study was conducted within a project funded by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant [MH099030].

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: Waxmonsky has received research funding from NIH, Supernus, and Pfizer and served on the advisory board for Iron Shore, NLS Pharma and Purdue Pharma. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02039908

IRB: Western Institutional Review Board, Protocol #20130136, Title: “Examining Tolerance to CNS Stimulants in ADHD”

References

- Altszuler AR, Page TF, Gnagy EM, Coxe S, Arrieta A, Molina BS, & Pelham WE (2016). Financial dependence of young adults with childhood ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(6), 1217–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LE, Chen ML, Perrin JM, & Van Cleave J (2015). Outpatient visits and medication prescribing for US children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics, 136(5), e1178–e1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autism P (2005). Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 62(11), 1266–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2014). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, & Fletcher K (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(2), 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Simon JO, & Epstein JN (2018). Reasons why children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder stop and restart taking medicine. Academic Pediatrics, 18(3), 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Epstein JN, March JS, Angold A, Wells KC, Klaric J, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Kraemer HC, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, … Wigal T (2001). Multimodal Treatment of ADHD in the MTA: An Alternative Outcome Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 159–167. 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S, West SG, & Aiken LS (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, & Blumberg SJ (2018). Prevalence of Parent-Reported ADHD Diagnosis and Associated Treatment Among U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 199–212. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, & Jimerson SR (2014). Assessing, understanding, and supporting students with ADHD at school: Contemporary science, practice, and policy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, & Stoner G (2014). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens JS, Wymbs BT, & Ray AR (2018). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 157–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham J, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Onyango AN, Kipp H, Lopez-Williams A, & Burrows-MacLean L (2006). A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE Jr, Coles EK, Gnagy EM, Chronis-Tuscano A, & O’Connor BC (2009). A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE Jr, Manos MJ, Gnagy EM, Chronis AM, Onyango AN, Lopez-Williams A, Burrows-MacLean L, Coles EK, & Meichenbaum DL (2004). An evaluation of three time-out procedures for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows-MacLean L, Coles EK, Chacko A, Wymbs BT, Walker KS, Arnold F, & Garefino A (2007). The single and combined effects of multiple intensities of behavior modification and methylphenidate for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a classroom setting. School Psychology Review, 36(2), 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Sturgis ET, McMahon RJ, Aguar D, Green K, Wells KC, & Breiner J (1979). Parent behavioral training to modify child noncompliance: Treatment generalization across time and from home to school. Behavior Modification, 3(1), 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, & Dulcan MK (2002). Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2), 26S–49S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Davies M, Clevenger W, Wu M, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Bukstein OG, & Conners CK (2001). Impairment and deportment responses to different methylphenidate doses in children with ADHD: The MTA titration trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group MC (1999). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(12), 1073–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JR, Bunford N, Evans SW, & Owens JS (2013). Educational Accommodations for Students With Behavioral Challenges: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 551–597. 10.3102/0034654313497517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Stehli A, Owens EB, Mitchell JT, Arnold LE, Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Jensen PS, Abikoff HB, Algorta GP, Howard AL, Hoza B, Etcovitch J, Houssais S, Lakes KD, & Quyen Nichols J (2016). Functional Adult Outcomes 16 Years After Childhood Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: MTA Results. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(11), 945–952.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Mrug S, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA, Kraemer HC, Pelham WE, Wigal T, & Arnold LE (2005). What Aspects of Peer Relationships Are Impaired in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 411–423. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass E, Posner JE, & Greenhill LL (2015). Pharmacological treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavior disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, Sjölander A, Serlachius E, Fazel S, Långström N, & Larsson H (2012). Medication for attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder and criminality. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(21), 2006–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe IM, & Feldman HM (2007). Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(6), 643–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke D (2021). sjPlot: Data visualisation for statistics in social science.(version 2.8. 7)[Computer software]. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S, Asherson P, Coghill D, Hollis C, Murray M, Potts L, Sayal K, de Soysa R, Taylor E, & Williams T (2009). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Treatment discontinuation in adolescents and young adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(3), 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill BM, Molina BS, Coxe S, Gnagy EM, Altszuler AR, Macphee FL, Morrow AS, Trucco EM, & Pelham WE (2019). Functional outcomes of young adults with childhood adhd: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Kennedy TM, Howard AL, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Mitchell JT, Stehli A, Kennedy EH, Epstein JN, Hechtman LT, Hinshaw SP, & Vitiello B (2023). Association Between Stimulant Treatment and Substance Use Through Adolescence Into Early Adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(9), 933–941. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, Epstein JN, Hoza B, Hechtman L, & Abikoff HB (2009). The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 484–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham III WE, Page TF, Altszuler AR, Gnagy EM, Molina BS, & Pelham WE Jr (2020). The long-term financial outcome of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(2), 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE Jr, & Altszuler AR (2020). Combined Treatment for Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Brief History, the Multimodal Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Study, and the Past 20 Years of Research. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 41, S88–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE Jr, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, & Milich R (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(2), 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE (1999). The NIMH Multimodal Treatment Study for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Just Say Yes to Drugs Alone? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44(10), 981–990. 10.1177/070674379904401004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Burrows-MacLean L, Gnagy EM, Fabiano GA, Coles EK, Wymbs BT, Chacko A, Walker KS, Wymbs F, & Garefino A (2014). A dose-ranging study of behavioral and pharmacological treatment in social settings for children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(6), 1019–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R, Pillow DR, Pelham WE Jr., Hoza B, Molina BSG, & Stultz CH (1998). Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale—Parent Version. Confirmatory Factor Analyses Examining Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Other Childhood Disruptive Behaviors, 26, 293–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka S (2007). Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(7), 894–921. 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoes C, Reid R, Wagner M, & Marder C (2006). ADHD among Students Receiving Special Education Services: A National Survey. Exceptional Children, 72(4), 483–496. 10.1177/001440290607200406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiel CF, Evans SW, & Langberg JM (2014). Evaluating the content of Individualized Education Programs and 504 Plans of young adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(4), 452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM (2019). Debate: Are stimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder effective in the long term?(against). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(10), 936–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman LT, Pelham WE, Greenhill LL, Conners CK, Kraemer HC, & Wigal T (2018). Long-term outcomes in the Multimodal Treatment study of Children with ADHD (the MTA). Oxford Textbook of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, 315–333. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Abikoff HB, Clevenger W, Davies M, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Owens EB, Pelham WE, Schiller E, Severe JB, … Wu M (2001). Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 168–179. 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, & Blackorby J (2002). Disability Profiles of Elementary and Middle School Students with Disabilities. SEELS (Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED477664 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.