Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate treatment outcomes of patients treated with antibiotic impregnated cement applied over implanted orthopaedic hardware, in the setting of fracture-related infection, without osseous union, after open reduction internal fixation.

Design:

Retrospective observational case series.

Setting:

Level 1 trauma center

Patients/Participants:

Retrospective review of 15 patients who underwent antibiotic cement application to their retained plate for the treatment of acute fracture-related infections (12) and acutely infected nonunion (3) status after open reduction internal fixation (ORIF).

Outcomes:

Suppression of infection and radiographic union by final follow-up.

Results:

Antibiotic plate application successfully led to fracture union in all 15 patients (100%). Three of these patients (20%) required removal of hardware. Of these 3 patients, all 3 achieved fracture union before hardware removal. However, 2 of these patients developed a chronic infection and were placed on long term PO antibiotics for chronic infection suppression, thus making them ineligible for classification as free of infection.

Conclusions:

The results of this study suggest that application of antibiotic cement to retained plates/screws for ORIF during treatment of both acute fracture infections and acutely infected nonunions is a viable technique to achieve osseous union. Hardware removal may be required in some cases. Use of this technique supports fracture healing and local infection control, while maintaining construct stability long enough to achieve fracture union.

Keywords: antibiotic plate, antibiotic cement, nonunion, ORIF, infection, fracture

1. Introduction

Infection after open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) is a challenging problem for orthopaedic trauma patients and the surgeons treating these patients. It is a significant source of patient morbidity resulting in continued pain at the previous fracture site, delayed healing, loss of reduction, and skin loss, which may result in further surgical intervention such as soft-tissue coverage or even amputation. In addition to these factors, delayed healing and infection result in significant cost to patients and health care systems.1 Rates of infection after ORIF are generally reported as 1%–3% and rates of infection after open fracture have been reported from 5% to 30%.2–7

Typical treatment for an infected nonunion in the initial operative setting is irrigation, debridement with either hardware retention, hardware removal or exchange, and IV antibiotic administration tailored to culture results from deep bony specimens. In acute fracture infection, hardware retention is usual while in infected nonunion, hardware removal or exchange is common.8 Given the absence of fracture union in these cases, removal/exchange of hardware imposes the risk of loss of reduction and subsequent malunion. Furthermore, there appears to be a lack of evidence regarding optimal treatment for achieving both fracture union and suppression of infection in this patient population. While much has been written on the use of antibiotic intramedullary nails, use of antibiotic impregnated polymethymethacrylate beads, antibiotic impregnated bioabsorbable bone substitute, and other sources of local antibiotics, little has been written regarding antibiotic plating.9,10 It is known that the ideal situation for fracture healing includes appropriate fracture stability and infection suppression. Therefore, in the setting of fracture-related infection, there may be benefit to applying antibiotic cement to well-fixed plates. Furthermore, local antibiotic delivery has been shown to reduce rates of acute and chronic infection.11

There is, however, no standard method for antibiotic plate application in this setting, and the evidence regarding outcomes after treatment with these implants is limited.12–14 Therefore, a simple, standardized, and reproducible method for applying antibiotic cement to plates is needed, along with an evaluation of its effectiveness in managing chronic infections. It is within this context that the purpose of this study was to report the results of a case series of patients who underwent antibiotic plate application for the treatment of acute fracture-related infections and acutely infected nonunions to expand the current literature.

2. Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective study was performed on all patients who underwent cement application to retained ORIF plates for the treatment of an acutely infected nonunion or acute infection. Patients were identified through a database of patients treated by fellowship trained, orthopaedic trauma surgeons. The data were collected via electronic medical records and chart review from 2012 to 2022 at a single level 1 trauma center. Through this database, Current Procedural Terminology codes 11981, 11982, 11983, 20700, 20701, 20702, 20703, 20704, and 20705 (Insertion of nonbiodegradable drug delivery implant, removal of nonbiodegradable drug delivery implant, removal with reinsertion of nonbiodegradable drug delivery implant, manual preparation and insertion of deep drug-delivery device, removal of deep drug-delivery device, insertion of intramedullary drug-delivery device, removal of intramedullary drug-delivery device, insertion of intra articular drug-delivery device, removal of intra articular drug-delivery device) were queried from fellowship trained orthopaedic trauma surgeons.

Two fellowship trained orthopaedic trauma surgeons conducted independent chart review to ensure patients met the inclusion criteria. Open fractures were categorized by the Gustilo-Anderson (GA) and the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA/AO) classifications using information derived from the operative reports. Patients with both acute fracture-related infection and acutely infected nonunions after ORIF were included. All infections included were at the site of surgical treatment. Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) purulent drainage from the superficial incision or (2) an organism(s) identified from an aseptically obtained specimen from the subcutaneous tissue as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for deep surgical site infections.15 These fractures were also confirmed infections under AO-supported, fracture-related infection consensus group criteria.14,16 Any bacterial cultures that were resistant to vancomycin and/or tobramycin were excluded from this study. Figures 1 and 2 show radiographs of patients with an acute fracture-related infections and an infected nonunion, respectively, at both initial fracture presentations and at the time of infection. Construct stability was independently assessed by the operative surgeons. Any patients with any hardware failure, loss of reduction, or concerns of other forms of nonunion were excluded from this study. Hardware failure was defined as any radiographic change in position, breaking, or loosening of orthopaedic implants compared with initial postoperative radiographic imaging.

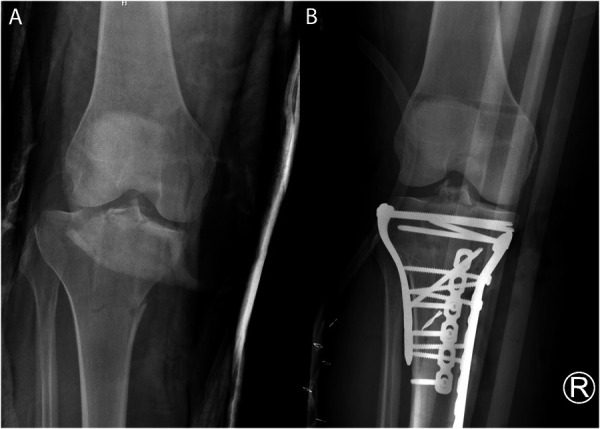

Figure 1.

(A) Initial fracture radiograph and (B) radiograph at the time of infection diagnosis of a patient with an acute fracture infection.

Figure 2.

(A) Initial fracture radiograph and (B) radiograph demonstrating nonunion of a patient with an acutely infected nonunion.

The US Food and Drug Administration's definition of nonunion is defined as a minimum of 9 months since the initial injury without boney union.17 Thus, this definition was adopted for this study. Those with acutely infected nonunions that were selected for this study were included if inciting symptoms, consistent with infection, were identified and presented within 2 weeks of undergoing surgical antibiotic cement application along with irrigation and debridement and had stable fixation (ie, lack of failed hardware or change in hardware fixation compared with prior clinical radiographs). All patients with nonunions and longer than 2 weeks of identifiable infectious symptoms were excluded from this study. Acute, postoperative, fracture-related infections occurred less than 4 weeks after ORIF and were diagnosed by a draining sinus, wound dehiscence with drainage or purulence, or a positive culture at the time of surgery.15 Freedom of infection was defined as no persistent clinical, radiographic, or laboratory evidence of infection at or before final follow-up while being off antibiotic therapy for at least 3 months. Patients who reached this 3-month mark and were not due for follow-up soon were called via telephone to assess signs and symptoms of infection.

Successful osseous union was confirmed after review of all plain radiographs or CT scans by 2 independent orthopaedic trauma surgeons. The Radiographic Union Scale for Tibia (RUST) fractures score was used to help identify union. The RUST scoring system was initially used for tibial fractures, but multiple studies have validated the scoring system in other bones including the humerus, femur, and ulna. RUST scores <7 have been shown to indicate persistent tibial nonunions, which was used as the model within our study. All patients within this study treated with this surgical technique had a preoperative RUST score of <7. Rust score of ≥10 have greater bone mineral density and mechanical strength, which was used as the benchmark value for demonstration of union and adequate biomechanical strength in all patients.18–23

If there was evidence of union, the antibiotic plate was removed at the surgeon's discretion. We excluded patients who were treated for chronic osteomyelitis unrelated to the index fracture and those with less than 6 months of follow-up. Tibia, humerus, femur, ulna, and fibula fractures were included. Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate radiographs of patients with acute infection and acutely infected nonunion, respectively, at the time of both antibiotic cement placement and fracture union. Our institutional antibiotic application protocol is described below.

Figure 3.

(A) Radiograph taken immediately after antibiotic cement placement and (B) radiograph demonstrating osseous union after antibiotic cement placement in a patient with an acute fracture infection.

Figure 4.

(A) Radiograph taken immediately after antibiotic cement placement and (B) radiograph demonstrating osseous union, after antibiotic cement placement in a patient with an acutely infected nonunion.

2.1. Antibiotic Plate Application Protocol

We followed a standard protocol with the goal of fracture union and infection suppression. Patients were admitted to the hospital electively if they were not septic, whereas patients with concern for sepsis were admitted directly through our emergency department. Patients had a standard workup including laboratories for infection (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], complete blood count [CBC] and white blood cell count). They also had a medical workup by our institution's internal medicine service for nutrition, chronic illness (diabetes, liver dysfunction, thyroid, kidney failure, cancer, HIV, and rheumatological disease), and bone mineral health (vitamin D, Ca, Mg, PTH). Preoperative optimization of these patients for surgical intervention was managed in a multidisciplinary approach with internal medicine. In the setting of sepsis, patients were treated with broad spectrum antibiotics before surgical treatment.

The antibiotic plate was fabricated using a goal of 10% antibiotic (ie, 40 g cement with 4 g of total antibiotics).24–26 This is done by using vancomycin and tobramycin in a 1:1 ratio to reach 4 g mixed with 1 radiopaque bone cement (Simplex P, Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI). The infections were treated with irrigation, debridement, and retention of the implant, which included both locking and nonlocking implants/screws. The lateral surface of the plates was coated with antibiotic cement and any bone defect was filled with antibiotic cement spacer after thorough debridement. The cement coating is ideally 3–4 mm in thickness to be both effective, but not preclude wound closure. The cement was applied in a manner so as to not cause heat necrosis of surrounding soft tissue. During repeat irrigation and debridement of the infected region, if the applied cement was noted to be compromised, as assessed by the operative surgeon, the cement was removed and reapplied to ensure complete coverage of the implant. Repeat irrigation and debridement procedures were performed every 2 days. No topical antibiotic powder was used in any part of the intraoperative procedures. Postoperatively, the patients were initially treated with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and then tailored according to culture results, as directed in a multidisciplinary approach. Culture-sensitive antibiotic treatment was guided by the infectious disease team. Patients established care with the infectious disease team before hospital discharge.

3. Results

A total of 19 patients were treated with antibiotic application to plates for either acute infection or acutely infected nonunion during our study period. Of these 19 patients, 4 (21%) were excluded because of follow-up less than 6 months. This left a total of 15 patients in our study group (75%). Two patients (13.3%) had an infected nonunion, and the other 13 had acute infection after ORIF. Fracture types included 7 tibia, 2 humeri, 2 femur, 3 fibulae, and 1 ulna, all initially treated by ORIF. All patients were indicated for surgery after being diagnosed with acute fracture-related infections or acutely infected nonunion at various times after their index fixation, by clinical, radiographic, and/or laboratory findings. Bacterial growth was not seen from intraoperative cultures on 3 patients, but each patient had a draining sinus tract. Table 1 details the baseline characteristics of our sample population.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Patient ID | Age | Race | Sex | Diabetes mellitus | IVDU | Smoking history | GA classification | Fracture mechanism | Infecting organism | Fracture location |

| Patient 1 | 33 | Black | Female | No | No | No | IIIA | MVC | No growth | 43C |

| Patient 2 | 56 | Black | Male | No | No | No | Closed | MVC | Polymicrobial | 41C |

| Patient 3 | 68 | Black | Male | Yes | No | Yes | II | MVC vs PED | Staphylococcus aureus | 43C |

| Patient 4 | 29 | White | Female | No | No | Yes | Closed | MVC | Enterobacter cloacae | 12C |

| Patient 5 | 65 | Other | Male | Yes | No | Yes | Closed | Fall | No growth | 31A |

| Patient 6 | 29 | Other | Male | Yes | No | No | IIIA | MVC | Staphylococcus aureus | 41C |

| Patient 7* | 52 | Black | Male | Yes | No | No | II | GSW | Staphylococcus aureus | 22C |

| Patient 8 | 61 | Black | Male | Yes | No | Yes | Closed | Fall | Polymicrobial | 43A |

| Patient 9* | 61 | White | Female | No | No | Yes | Closed | Fall | No growth | 12B |

| Patient 10 | 43 | White | Male | No | No | Yes | Closed | MVC | Enterobacter cloacae | 41C |

| Patient 11 | 70 | Black | Female | Yes | No | Yes | Closed | Fall | Staphylococcus aureus | 33C |

| Patient 12 | 42 | Other | Female | Yes | No | No | Closed | Fall | Staphylococcus aureus | 43A |

| Patient 13 | 36 | Other | Male | Yes | No | Yes | Closed | Fall | Staphylococcus aureus | 43C |

| Patient 14 | 59 | Black | Male | Yes | No | No | Closed | Fall | Polymicrobial | 41C |

| Patient 15 | 34 | White | Female | No | No | No | Closed | E-Scooter accident | Enterobacter cloacae | 41C |

Table detailing all 15 patients selected based on age, race, sex, diabetes status, IV drug use, smoking history, GA classification, fracture mechanism, infecting organism, and fracture location.

Infected nonunion.

GSW, gunshot wound; MVC, motor vehicle collision; MVC vs. PED, motor vehicle collision versus pedestrian.

There were 4 patients (26.6%) who originally sustained open fractures, whereas 11 patients (73.4%) sustained closed injuries. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association open fracture classification of each of these patients is included in Table 2. Of note, there were 2 GA type IIIA fractures, 1 of the 2 was complicated by compartment syndrome requiring 2 separate procedures (4 days after index surgery) for complete primary closure. Staphylococcus aureus was the sole infecting organism in 6 cases (40%). Enterobacter cloacae was identified as the cause of infection in 3 cases (20%). Cultures identified polymicrobial infection in 3 cases (20%), and in 3 cases, no organism could be identified (20%). The mechanism of initial injury was related to a fall in 7 cases (46.6%) and a motor vehicle collision in 5 cases (33.3%). There was 1 case of motor vehicle collision versus pedestrian (6.7%), 1 case related to a gunshot wound (6.7%), and 1 because of an electric scooter accident (6.7%). Eight patients (53.3%) reported positive tobacco use and 9 had a medical history containing diabetes (60%).

Table 2.

Open fracture classifications.

| Patient ID | Skin | Muscle | Arterial | Contamination | Bone loss | GA classification | Fracture mechanism | Fracture location |

| Patient 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | IIIA | MVC | 43C |

| Patient 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | II | MVC vs PED | 43C |

| Patient 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | IIIA | MVC | 41C |

| Patient 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | II | GSW | 22C |

Table indicating the Orthopaedic Trauma Association open fracture classification, the GA open fracture classifications, mechanisms, and locations of the injuries for patients with open fractures.27

GSW, gunshot wound; MVC, motor vehicle collision; MVC vs. PED, motor vehicle collision versus pedestrian.

The average number of irrigation and debridement (I&D) procedures performed was 3.7. During the first procedure after infection diagnosis, antibiotic cement was applied for all patients within this study. Of all 15 patients, 4 required repeat antibiotic cement placement (26.7%) with an average number of 2 reapplications of antibiotic cement per the 4 patients. All patients within this study were closed primarily and did not require additional soft tissue coverage.

Antibiotic plate application successfully led to fracture union in 100% of patients. This was shown in all RUST scores being 10 or above (11.2 average). Three of these patients required removal of hardware because of acute infections after achieving radiographic union. All 3 patients were in the acute infection cohort of patients. Of the 3 patients who required hardware removal, 2 (66.7%) had polymicrobial infections and 1 (33.3%) had a GA grade IIIA open fracture with subsequent compartment syndrome. All 3 patients underwent removal of hardware and another course of IV antibiotics. After plate removal, 2 of the patients within this group were placed on long-term oral (PO) antibiotics for chronic infection suppression thus making them ineligible for classification as free of infection. One patient sustained a closed injury the other was a GA grade IIIA open injury. The first of the 2 had uncontrolled type II diabetes mellitus management with chronic wound dehiscence that necessitated the original plate removal and the second underwent delayed closure of a fasciotomy site (4 days from index surgery). Treatment failure was defined as recurrent infection requiring hardware removal and/or lack of union 1 year after antibiotic cement placement. Although all patients achieved osseous union (100%), 3 patients (20%) required hardware removal, indicating an 80% treatment success rate. It should be noted that all patients with acutely infected nonunion went on to union, indicating that the 3 patients requiring removal of hardware had acute on chronic infections. The average follow-up for our patient population was 26 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient treatment outcomes.

| Patient ID | Repeat antibiotic cement application (# of repeat applications) | # of I&D's | Follow-up months | Hardware removed | Hardware removal reason | Freedom of infection | RUST score | Reported osseous union |

| Patient 1 | No | 6 | 12 | No | N/A | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 2 | Yes (3) | 6 | 12.7 | Yes | Chronic infection | No | 11 | Yes |

| Patient 3 | No | 1 | 6.8 | No | N/A | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 4 | No | 1 | 13.7 | No | N/A | Yes | 10 | Yes |

| Patient 5 | No | 1 | 7.1 | No | N/A | Yes | 11 | Yes |

| Patient 6 | No | 5 | 7.3 | Yes | Chronic infection | No | 11 | Yes |

| Patient 7* | No | 5 | 191.4 | No | N/A | Yes | 10 | Yes |

| Patient 8 | No | 2 | 6 | Yes | Exposed hardware | No | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 9* | Yes (1) | 5 | 85.2 | No | N/A | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 10 | Yes (2) | 5 | 8.8 | No | N/A | Yes | 10 | Yes |

| Patient 11 | No | 3 | 6.5 | No | N/A | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 12 | No | 1 | 6.7 | No | N/A | Yes | 11 | Yes |

| Patient 13 | No | 2 | 6.4 | No | N/A | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Patient 14 | No | 5 | 8 | No | N/A | Yes | 11 | Yes |

| Patient 15 | Yes (2) | 7 | 10.7 | No | N/A | Yes | 11 | Yes |

Table detailing the treatment outcomes of all 15 patients followed during this study with subsequent RUST scores and reported osseous union.

Infected nonunion.

I&D, irrigation and debridement.

Osseous union occurred as early as 40 days after antibiotic cement placement with an average of 127 days to union for all patients. Freedom of infection was achieved as early as 93 days after antibiotic cement placement with an average of 269 days for all patients.

4. Discussion

Given the limited data reported on the optimal treatment for suppression of an infection and osteomyelitis following ORIF, it can be difficult for orthopaedic surgeons to determine the best course of management for their patients. The typical course of treatment in acute fracture-related infection is hardware retention, while the hardware is removed or exchanged in chronic or delayed infection.8

An argument for hardware retention is that removal of the original plate destabilizes the construct which can increase complications with regards to healing. Worlock et al,28 demonstrated that increased osseous stability leads to decreased infection rates, and it is known the ideal conditions for fracture healing include both fracture stability and infection supression.29–31 Taking this information into account, it is reasonable to assume that optimal healing and infection suppression can be achieved with retention of hardware. This was first tested in a retrospective study by Berkes et al32 following 123 cases of postoperative ORIF infections, treated with I&D, plate retention, and culture-specific antibiotic treatment postoperatively. While 87 (71%) of those cases went on to fracture union, 26 of those patients had recurrent infections requiring hardware removal after union, indicating a 50.4% infection control rate. A similar study containing 69 patients reported an infection control rate of 27.5%.33 Given this suboptimal infection control rate, further investigation into new techniques for treating acutely infected nonunions after ORIF was warranted. In a later study, Qiu et al12 reported a 100% union rate and 90% infection clearance rate in 10 patients treated for acute infection, with hardware retention and antibiotic cement application. This study was, however, was limited in to primary vancomycin-sensitive staphylococcus infections less than or equal to one month postoperatively. When comparing the results of these studies, a drastic difference in the reported infection and union rates can be seen. In all 3 studies, patients had their original hardware retained and received culture-specific antibiotics postoperatively, thus indicating that the addition of antibiotic cement to the retained plates improved infection control and union rates.12,32,33

With this technique, alongside the standard of surgical irrigation and debridement, bacterial removal and suppression is due to 3 specific mechanisms: chemical, mechanical, and thermal. Management of infection with irrigation and debridement is a common practice resulting in manual dilution and removal of infected tissue. Insertion of local antibiotic cement delivery devices brings with it the benefits of administering higher concentrations of antibiotics to a specific location than can be done with systemic antibiotics.34,35 Elution of antibiotics has been shown to peak in the first 24–48 hours after implantation,34,36,37 with studies reporting mean inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics being delivered locally up to 4 months after cement implantation.36–38 Retention of the original hardware is controversial, as it has been shown that the typical source of implant related infections is biofilm forming bacteria.7 Biofilm is known to adhere to implants and so it has been common practice that the infected plate be removed to treat the underlying infection.8 The formation of biofilm by bacteria has been shown to peak 2 weeks after implant seeding.39 During the polymerization process, bone cement gives off large amounts of heat. An in vitro study looking at the impact of heat on biofilm elimination found that up to 97% of biofilm bacteria were eliminated at temperatures ranging from 48°C to 100°C.40 Similar levels of heat are produced in the exothermic polymerization of bone cement, indicating that the heat produced by the antibiotic cement placed over infected plates should eliminate a significant portion of the biofilm remaining on the plate following extensive I&D.41

Although the use of antibiotic cement over infected ORIF plates has demonstrated promise in prior studies, the issue with determining the efficacy of this treatment modality at this time is the small number of total cases reported in the literature. Thus, the goal of this study was to expand to the literature and report on a case series of patients treated for acute fracture infection or acutely infected nonunion following ORIF with antibiotic cement covering retained plates and screws. Outcomes from this study demonstrated that using the technique described in this report show the rate of fracture union was 100%, and the infection control rate was 80%, similar to those found by Qiu et al.12 Expansion of this technique within this study showed that more infectious bacteria such as polymicrobial infections, Staphylococcus Aureus, and Enterobacter Cloacae, can be treated with this technique. The results of this study indicate that application of antibiotic cement to retained ORIF plates, with the conjunction of irrigation and debridement, in the setting of acute fracture-related infection or acutely infected nonunion is a viable treatment method. This technique promotes fracture union in the setting of local infection control.

Limitations to this study were the low patient census, lack of comparison group, retrospective design, fracture type (open and closed), and fracture location. Second, the lack of control over systemic antibiotic treatment allowed for variability in intraoperative culture identification and postoperative treatment regimen. Doing so not only introduced an additional uncontrolled variable but also created difficulty when trying to establish patient infection free rate because of variable lengths of treatment. Treatment effectiveness toward specific bacterial species is limited within this study as individual analysis is underpowered. Therefore, treatment of acutely infected nonunions with this technique on a bacterial, species specific, basis cannot be made from this study. This technique should not act as an isolated alternative to systemic treatment of sepsis. This study was limited to patients without hardware failure, loss of reduction, or other forms of nonunion. Therefore, no conclusions can be made if this technique is viable as a treatment strategy in these situations. Finally, treatment of septic nonunions was shown to be successful in 2 patients but was specific to acute infections in the setting of nonunion and limited to a low patient census.

Future directions would be to establish a prospective cohort study, selecting for only those with only open fractures, as well as isolating infections by bacterial species to determine the efficacy of this treatment in those populations. These future studies would ideally have better control over the postoperative antibiotic treatment regimen; however, this would require prospective collaboration with an infectious disease team before beginning the study. Additional, large, randomized trials or further analyses are necessary for further validation of this technique.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that application of antibiotic cement to retained plates/screws for ORIF during treatment of both acute fracture-related infection and acutely infected nonunion was a viable technique to achieve osseous union in this patient cohort. Use of this technique supports fracture healing and local infection control, while maintaining construct stability long enough to achieve fracture union.

Acknowledgments

This article has not been previously presented or published and is not under consideration for publication by any other journal. All authors have significantly contributed to this research and have no conflicts of interest to disclose nor do these authors have any source of funding to report. This article has been reviewed by all authors and they support its submission to Orthopedic Trauma Association International.

Footnotes

Source of funding: Nil.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board and Animal Use Committee Review.

Contributor Information

Hunter Ross, Email: hunterlross@gmail.com.

Tannor Court, Email: Tannor.Court@gmail.com.

Daniel Cavazos, Email: drcavazos7@gmail.com.

Trey D. VanAken, Email: trey@vanaken.net.

Rahul Vaidya, Email: rahvaidya2012@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Q, Aierxiding A, Wang G, et al. Incidence and risk factors for deep surgical site infection after open reduction and internal fixation of closed tibial plateau fractures in adults. Int Wound J. 2018;15:237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stennett CA, O'Hara NN, Sprague S, et al. Effect of extended prophylactic antibiotic duration in the treatment of open fracture wounds differs by level of contamination. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Wang H, Tang Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors for surgical site infection after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fracture: a retrospective multicenter study. Medicine. 2018;97:e9901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng J, Sun T, Zhang F, et al. Deep surgical site infection after ankle fractures treated by open reduction and internal fixation in adults: a retrospective case-control study. Int Wound J. 2018;15:971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinmetz S, Wernly D, Moerenhout K, et al. Infection after fracture fixation. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Diagnosis and treatment of infections associated with fracture-fixation devices. Injury. 2006;37(suppl 2):S59–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metsemakers WJ, Morgenstern M, Senneville E, et al. General treatment principles for fracture-related infection: recommendations from an international expert group. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140:1013–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismat A, Walter N, Baertl S, et al. Antibiotic cement coating in orthopedic surgery: a systematic review of reported clinical techniques. J Orthop Traumatol. 2021;22:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKee MD, Li-Bland EA, Wild LM, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing an antibiotic-impregnated bioabsorbable bone substitute with standard antibiotic-impregnated cement beads in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis and infected nonunion. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barth RE, Vogely HC, Hoepelman AIM, et al. “To bead or not to bead?” Treatment of osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint-associated infections with gentamicin bead chains. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu XS, Cheng B, Chen Yxin, et al. Coating the plate with antibiotic cement to treat early infection after fracture fixation with retention of the implants: a technical note. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu X, Wu H, Li J, et al. Antibiotic cement-coated locking plate as a temporary internal fixator for femoral osteomyelitis defects. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1851–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liporace FA, Yoon RS, Frank MA, et al. Use of an “antibiotic plate” for infected periprosthetic fracture in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:e18–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Checklist . National Healthcare Safety Network. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/checklists/Surgical-Site-Infection-SSI-Checklist.pdf: CDC; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway JD, Hlad LM, Bark SE. Antibiotic cement-coated plates for management of infected fractures. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:E49–E53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham BP, Brazina S, Morshed S, et al. Fracture healing: a review of clinical, imaging and laboratory diagnostic options. Injury. 2017;48(suppl 1):S69–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leow JM, Clement ND, Tawonsawatruk T, et al. The radiographic union scale in tibial (RUST) fractures: reliability of the outcome measure at an independent centre. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5:116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneble CA, Li DT, Kahan J, et al. Reliability of radiographic union scoring in humeral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:e437–e441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graf RM, Shaw JT, Simske NM, et al. Distal femur nonunion: risk factors and validation of RUST scores. OTA Int Open Access J Orthop Trauma. 2023;6:e234. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kizkapan TB, Misir A, Oguzkaya S, et al. Reliability of radiographic union scale in tibial fractures and modified radiographic union scale in tibial fractures scores in the evaluation of pediatric forearm fracture union. Jt Dis Relat Surg. 2021;32:185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christiano AV, Goch AM, Leucht P, et al. Radiographic union score for tibia fractures predicts success with operative treatment of tibial nonunion. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10:650–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooke ME, Hussein AI, Lybrand KE, et al. Correlation between RUST assessments of fracture healing to structural and biomechanical properties. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:945–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maceroli MA, Yoon RS, Liporace FA. Use of antibiotic plates and spacers for fracture in the setting of periprosthetic infection. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(suppl 6):S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anagnostakos K, Wilmes P, Schmitt E, et al. Elution of gentamicin and vancomycin from polymethylmethacrylate beads and hip spacers in vivo. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:193–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink B, Vogt S, Reinsch M, et al. Sufficient release of antibiotic by a spacer 6 weeks after implantation in two-stage revision of infected hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3141–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orthopaedic Trauma Association Open Fracture Study Group. Open Fracture Study Group: a new classification scheme for open fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worlock P, Slack R, Harvey L, et al. The prevention of infection in open fractures: an experimental study of the effect of fracture stability. Injury. 1994;25:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellwinkel JE, Working ZM, Certain L, et al. The intersection of fracture healing and infection: orthopaedics research society workshop 2021. J Orthop Res. 2022;40:541–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perren SM. Evolution of the internal fixation of long bone fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84-B:1093–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster AL, Moriarty TF, Zalavras C, et al. The influence of biomechanical stability on bone healing and fracture-related infection: the legacy of Stephan Perren. Injury. 2021;52:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkes M, Obremskey WT, Scannell B, et al. , Southeast Fracture Consortium. Maintenance of hardware after early postoperative infection following fracture internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rightmire E, Zurakowski D, Vrahas M. Acute infections after fracture repair: management with hardware in place. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anagnostakos K, Meyer C. Antibiotic elution from hip and knee acrylic bone cement spacers: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4657874–4657877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh PH, Chang YH, Chen SH, et al. High concentration and bioactivity of vancomycin and aztreonam eluted from SimplexTM cement spacers in two-stage revision of infected hip implants: a study of 46 patients at an average follow-up of 107 days. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishitani K, Sutipornpalangkul W, de Mesy Bentley KL, et al. Quantifying the natural history of biofilm formation in vivo during the establishment of chronic implant-associated Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in mice to identify critical pathogen and host factors. J Orthop Res. 2015;33:1311–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pihl M, Bruzell E, Andersson M. Bacterial biofilm elimination using gold nanorod localised surface plasmon resonance generated heat. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;80:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaishya R, Chauhan M, Vaish A. Bone cement. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2013;4:157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiranek WA, Hanssen AD, Greenwald AS. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement for infection prophylaxis in total joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2487–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahpari O, Mousavian A, Elahpour N, et al. The use of antibiotic impregnated cement spacers in the treatment of infected total joint replacement: challenges and achievements. Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2020;8:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tande AJ, Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:302–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]