Abstract

Most of the biological functions related to pathogenicity and virulence reside in the fungal cell wall, which, being the outermost part of the cell, mediates the host-fungus interplay. For these reasons much effort has focused on the discovery of useful inhibitors of cell wall glucan, chitin, and mannoprotein biosynthesis. In the absence of a wide-spectrum, safe, and potent antifungal agent, a new strategy for antifungal therapy is directed towards the development of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). In the present study the MAb A9 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) was identified from hybridomas raised in BALB/c mice immunized with cell wall antigen of Aspergillus fumigatus. The immunoreactive epitopes for this IgG1 MAb appeared to be associated with a peptide moiety, and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy revealed its binding to the cell wall surface of hyphae as well as with swollen conidia. MAb A9 inhibited hyphal development as observed by MTT [3-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay (25.76%), reduced the duration of spore germination, and exerted an in vitro cidal effect against Aspergillus fumigatus. The in vivo protective efficacy of MAb A9 was also evaluated in a murine model of invasive aspergillosis, where a reduction in CFU (>4 log10 units) was observed in kidney tissue of BALB/c mice challenged with A. fumigatus (2 × 105 CFU/ml) and where enhanced mean survival times (19.5 days) compared to the control (7.1 days) and an irrelevant MAb (6.1 days) were also observed.

Invasive aspergillosis is a serious opportunistic fungal infection caused by an ubiquitous saprophyte, Aspergillus fumigatus, in immunocompromised hosts, including patients with AIDS and patients undergoing antineoplastic chemotherapy and organ transplantation (9, 36, 41). The presently available antifungal drugs have been targeted mainly to the inhibition of ergosterol synthesis (14). However, there are a few antifungals, such as echinocandins and glycolipid papulacandin, with which inhibition of cell wall glucan biosynthesis leads to cessation of growth and cell lysis (21). Most of the biological functions related to pathogenicity and virulence reside in the fungal cell wall, which, being the outermost part of the cell, mediates the host-fungus interplay (7). This includes triggering and modulation of host immune responses. The identification and characterization of cell wall immunodominant proteins eliciting potent immune responses during aspergillosis could have important repercussions for developing novel diagnostic, prophylactic, and therapeutic techniques for aspergillosis. For these reasons much effort has focused on the discovery of useful inhibitors of cell wall glucan, chitin, and mannoprotein biosynthesis. In the absence of a wide-spectrum, safe, and potent antifungal agent, a new strategy for antifungal therapy is directed towards the development of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs).

MAbs have served as useful research tools and have dramatically improved the specificity of immune procedures. Some of the many applications of MAbs are immunochemical characterization and purification of bacterial, fungal, or viral antigens; localization of viral and fungal glycoproteins; and development of antibody and antigen detection assays (5, 10). A number of studies on MAbs against Aspergillus antigens have been directed towards the specific diagnosis of the disease (11, 13, 18, 38), whereas very limited work has been carried out on the use of MAbs for the treatment of aspergillosis (6, 30) compared to candidiasis (4, 16, 17, 27, 31, 37). Here we report the generation of an immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) MAb against cell wall glycoprotein of A. fumigatus, its characterization, and the therapeutic potential in vitro. This MAb, when evaluated against a murine model of aspergillosis, also caused an increase in the mean survival time (MST) and reduced the fungal load in the kidneys of experimental mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal cultures.

Aspergillus fumigatus, an isolate from a case of human aspergillosis, was used for generating MAbs, and the other pathogenic fungal strains used for cross-reactivity tests were Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger DSM 2182, Aspergillus terreus DSM 826, Candida albicans ATCC 10231, Candida krusei ATCC 6258, Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019, Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC 66031, Sporothrix schenckii, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes. The species-level identities of most of the isolates were confirmed by amplification of the internal transcribed spacer regions of these fungi (19). All these fungi were maintained at 28°C on Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) slants.

Collection of sera from cases of human aspergillosis.

Sera of nine patients with suspected cases of aspergillosis (six bronchopulmonary and three invasive cases) were collected from patients visiting local hospitals, confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and pooled for identification of immunogenic proteins of A. fumigatus. Prior institutional approval for working with human subjects was obtained.

Preparation of cell wall antigen.

A. fumigatus mycelia were harvested from 5 -day-old shake cultures (in Sabouraud's dextrose broth at 300 rpm) and washed thoroughly with chilled, autoclaved triple-distilled water. The wet mass was immediately frozen and kept at −80°C until used. Frozen mycelia were thawed and mixed with lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM freshly prepared phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 μg/ml of pepstatin A. The mycelia in this mixture were disrupted in a Bead Beater (Hamilton Beach/Proctor-Silex, Inc.) with acid-washed glass beads (0.5 μm), maintaining the temperature below 4°C. After 15 to 20 cycles of 30 s each followed by a pause of 3 min, complete breakage was monitored under phase-contrast microscopy. The broken mycelia were centrifuged at 5,000 × g at 4°C, and the cell wall pellet was boiled in extraction buffer containing 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The resultant mixture was again centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min, and the collected supernatant was stored at −80°C. Protein content in the supernatant was quantified by the method of Lowry et. al (24). All chemicals used in the present study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. unless otherwise mentioned.

Monoclonal antibody generation. (i) Immunization of mice.

Female BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously with 100 μl of cell wall antigen preparation in Freund's complete adjuvant (1:1), followed by five doses (on days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 37) of the same cell wall preparation in saline with incomplete Freund's adjuvant. A booster dose of the antigen in saline was injected intravenously 3 days prior to fusion experiments. Prior clearance from the local animal ethics committee was obtained.

(ii) Fusion procedure.

Fusion of the splenocytes from immunized mice with the Sp2/O myeloma cell line at a ratio of 1:2 was performed in 50% polyethylene glycol. This suspension was then mixed with RPMI 1640-HEPES modified medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1× antimycotic and antibacterial solution and dispensed in 96-well tissue culture plates (Greiner; Bio One GmbH). The plates were incubated in an incubator at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Screening for positive hybridoma selection was done by ELISA after 7 days of incubation when the clones started looking like a bunch of grapes. Positive hybrids were immediately subcloned thrice by limiting dilution and cryopreserved. Larger amounts of antibodies were produced in serum-free medium, precipitated with 50% ammonium sulfate, dialyzed against Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and stored at −80°C. The protein content of the MAb A9 preparation was quantified with a 2D Quant protein estimation kit (Amersham), and the percentage of immunoglobulin was determined in a protein gel by using Quantity 1 software (Bio-Rad).

ELISA.

ELISA was used for the screening of the hybridomas. Briefly, each well of microtiter plates (Greiner; Bio One GmbH) was coated with 100 μl of cell wall antigens of A. fumigatus adjusted to a concentration of 15 μg/ml in 0.6 M bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were blocked by treatment with 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin for 90 min at 37°C. Supernatant from wells with growing hybridomas was then added to the blocked plates (100 μl per well) and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. Plates were washed with PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) diluted 1:5,000 in PBS-Tween 20 for 90 min at 37°C. After washing, 100 μl of substrate containing 0.05% (wt/vol) ortho-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride and 0.03% (vol/vol) H2O2 in 0.15 M phosphate citrate buffer (pH 5.0) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated in dark at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 1 N H2SO4, and optical densities were read on a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 450 nm.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Cell wall proteins of the different fungi used in this study were extracted as described above, and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed by the method of Laemmli (20) in a minigel system. The total amount of protein loaded per lane was 15 to 20 μg for each cell wall extract. Electrophoresis was carried out in 12% (wt/vol) acrylamide gels at 160 V for 90 min. Standard molecular weight markers were also run simultaneously. Subsequently, the proteins in the gel were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (39). The PVDF membranes were then probed using supernatants of ELISA-positive hybridomas (clones A1 to A11) for specificity and cross-reactivity of MAbs. After the transfer, the membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline and incubated with 1:20 dilutions of MAbs A1 to A11. After washing, they were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Immunoreactive bands were developed with a substrate solution of diaminobenzidine.

Isotyping of MAb A9.

The isotype of the selected MAb A9 was determined with a monoclonal isotyping kit (Sigma Co.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Determination of nature of protein.

To determine the nature of the protein recognized by MAb A9, the removal of carbohydrate groups from cell wall antigens of A. fumigatus was accomplished by oxidation with sodium meta-periodate on a PVDF membrane. The cell wall antigens electrotransferred onto PVDF after SDS-PAGE were treated with 0.05 M sodium meta-periodate in 0.05 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) for 18 h at 4°C. The PVDF strips were then washed with acetate buffer, and the reactive groups were blocked with 1% glycine in the same buffer (27). For glycoprotein detection, the SDS-polyacrylamide gel of A. fumigatus cell wall antigen was directly stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) according to the method of Leach et al. (22).

Biological activity of MAb A9. (i) In vitro inhibitory activity.

The cidal activity of MAb A9 against all the fungi included in this study was determined by the method of Magliani et al. (25) with minor modifications. Briefly, 1 × 103 spores of A. fumigatus were incubated with 100 μl of MAb A9 (50 μg) for 18 h at 37°C. An irrelevant monoclonal IgG raised against C. albicans in our lab in a separate fusion experiment was used as a control. After incubation with MAb A9, the CFU were determined by plating 50 μl of this suspension on SDA at 35°C.

(ii) Cell viability assay by FACS.

Spores of A. fumigatus were collected and, after washing, suspended in DPBS at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml. Graded amounts (50, 100, 200, and 400 μg) of MAb A9 in 1-ml aliquots of this cell suspension were incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Irrelevant antibody (50 μg/ml) and PBS alone were simultaneously used as controls. After incubation, 2 μl of propidium iodide (1 mg/ml in water) and 10 μl of fluorescein diacetate (5 mg/ml in acetone diluted 1:20 in DPBS) were added, and the mixture was stored on ice for not more than 30 min before analysis on a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). In another experiment, the optimum amount of MAb A9 (400 μg) was treated with papain to cleave the Fc part and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis with A. fumigatus spores as described above to subtract the amount of cell death due to agglutination, if any (33). Data presented are the averages from three experiments.

(iii) Germination assay.

The germination assay was performed by a previously described method with minor modifications (26). Ten microliters of A. fumigatus conidia (1 × 105/ml) in RPMI 1640 was incubated in polypropylene tubes at 37°C with gentle shaking in the presence of 50 μg of MAb A9. At regular intervals of 30 min, aliquots were removed and germinated conidia were counted by using a hemocytometer. An irrelevant IgG MAb at the same concentration served as a control. A total of 100 germinated conidia per field were counted, and the mean value of three independent counts was calculated. Percent germination was calculated as germinated conidia/total counted cells × 100.

(iv) MTT assay for hyphal damage.

A colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay (23) was employed to study Aspergillus hyphal damage caused by MAb A9. Briefly, 200 μl of a suspension of swollen conidia at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 was incubated with 200 μl of MAb A9 (50 μg) in a 48-well tissue culture plate overnight at 37°C in an incubator having an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min, the supernatant were checked for the absence of fungal cells and discarded. MTT (200 μl) at a concentration of 0.05 mg/ml in RPMI 1640 was added to each well and incubated further for 3 h. The wells were then aspirated dry, 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide was used to extract the dye from each well, volumes of 100 μl were transferred into the wells of a 96-well plate, and the color was measured on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at 550 nm. A well containing only dimethyl sulfoxide served as a blank, a well containing only swollen conidia served as a positive control, while wells containing swollen conidia and irrelevant monoclonal IgG served as negative controls. Antifungal activity (percentage of hyphal damage) was calculated as (1 − T/C) × 100, where T is the optical density of test wells at 3 h and C is the optical density of control wells containing hyphae only. Each set of conditions was tested in triplicate, and the results were averaged.

(v) Immunofluorescence.

Conidia of A. fumigatus grown on SDA slants were collected, washed, and suspended in PBS (105 cells/ml). Ten microliters of this was placed on glass slides coated with poly-l-lysine, dried at 37°C, and incubated with 10 μl (25 μg) of MAb A9 for 1 h at 37°C in a moist chamber. The slides were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200) in PBS-Tween 20 at 37°C in a moist chamber. The slides were then washed twice in PBS, mounted in PBS containing 90% glycerol, and examined under a fluorescence microscope.

(vi) Phagocytic assay.

Mouse macrophages (J 774) grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS without antibiotic and antimycotic agents were seeded (1 × 106/well) in a six-well tissue culture plate and allowed to adhere for at least 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. MAb A9-treated conidia were cocultured with macrophages at a 2:1 ratio in the same environment for 30 min. For complement inactivation, the FBS used in the medium and the MAb A9 solution were heated at 56°C for 30 min with occasional swirling and chilled to 4°C for few minutes. Macrophages were cultured in this medium, and phagocytosis assay was performed as described above. A control experiment was performed to assess phagocytosis without MAb A9 treatment of conidia. Cells were washed with PBS and Giemsa stained to count the number of phagocytosed A. fumigatus conidia.

(vii) In vivo evaluation of MAb A9 in mice.

The protective role of MAb A9 was determined in experimental BALB/c mice. The dose was selected on the basis of the optimum concentration at which MAb A9 exerted the maximum in vitro inhibitory effect. A. fumigatus conidia (1 × 103 cells) were incubated overnight at 37°C with 100 μl of MAb A9 (12.5 μg, 25 μg, and 50 μg), and CFU were determined by plating. A 50-μg amount of MAb A9 was selected because it showed the maximum cidal effect. Four groups of 10 mice each were taken, where the first three were given intravenous prophylactic doses of MAb A9, irrelevant IgG, and PBS, respectively, 2 h before intravenous challenge with A. fumigatus spores (2 × 105 spore per mouse) and the fourth group, without any treatment, served as a control. The animals were observed daily for morbidity and mortality, and the MST was calculated after 26 days. To evaluate the effect of MAb A9 on fungal load in kidney tissue, another set of infected mice were sacrificed 7 days postinoculation and the CFU in tissue homogenates were determined by the dilution-and-plating method.

RESULTS

A total of 11 hybridomas producing monoclonal antibodies against cell wall proteins of A. fumigatus were obtained through ELISA. These hybridomas were subcloned for three generations to determine their antibody-producing capacity and stability. The indirect immunofluorescence study revealed that only MAb A9 had a capacity to bind with both hyphae and swollen conidia (Fig. 1). Further, MAb A9 exhibited high reactivity on Western blots probed with rabbit hyperimmune serum as well as pooled sera from human aspergillosis. Therefore, further studies were undertaken with this MAb. The percentage of MAb A9 determined by in-gel analysis was found to be 68%. This was taken into consideration for further experiments.

FIG. 1.

Immunofluorescence photograph of A. fumigatus swollen and germinated conidia stained with MAb A9. Fluorescence was uniformly distributed over the entire surface of the fungal cells.

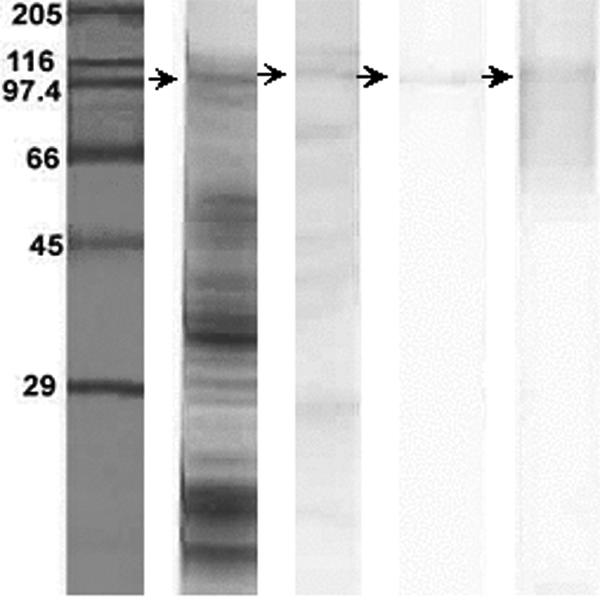

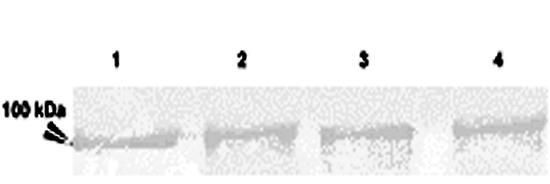

Periodate oxidation of a cell wall extract of A. fumigatus on a PVDF membrane resulted in reduction of carbohydrate residue of the glycoproteins, and sharp bands appeared. The protein binding with MAb A9 had a molecular mass of >95 kDa and was identified as a glycoprotein (Fig. 2). This confirmed that the epitope recognized by MAb A9 was proteinaceous in nature. The isotype of this monoclonal antibody was found to be IgG1 as determined with a monoclonal isotyping kit. This MAb was found to be specific against the species of aspergilli used in this study (Fig. 3), as it did not cross-react with the cell wall proteins of other human-pathogenic fungi (Candida albicans ATCC 10231, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC 66031, Sporothrix schenckii, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes).

FIG. 2.

Characteristic protein profile of the cell wall of A. fumigatus on 12% SDS-PAGE. Strips (left to right): 1, standard molecular mass marker; 2, complete protein profile on gel stained with Coomassie blue; 3, immunogenic proteins of A. fumigatus as detected by immunoblotting using pooled sera from patients with aspergillosis; 4, detection of immunogenic protein of the A. fumigatus cell wall probed with MAb A9; and 5, PAS-stained immunogenic protein (as in strip 4), demonstrating it to be a glycoprotein.

FIG. 3.

Detection of the same antigenic protein in A. fumigatus (lane 1), A. flavus (lane 2), A. niger (lane 3), and A. terreus (lane 4) by immunoblotting using MAb A9.

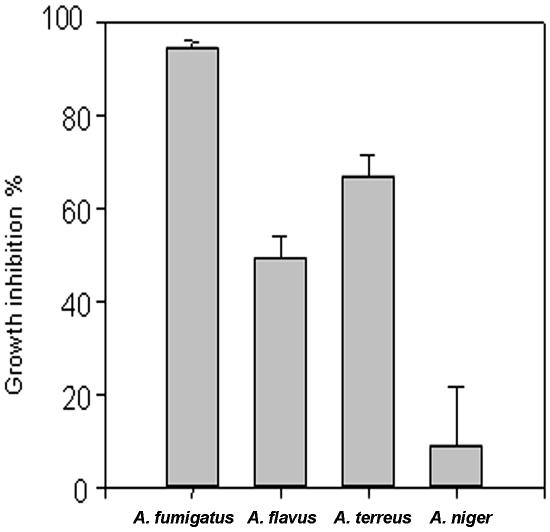

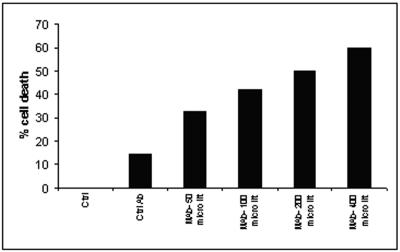

MAb A9 exhibited a potent cidal activity against all four species of Aspergillus, as significant reductions in the number of CFU compared to controls (without any MAb) as well as with an irrelevant MAb were observed. The optimum dose of MAb A9 was found to be 50 μg, where it caused 94.8% reduction in CFU (P < 0.0001) of A. fumigatus (Fig. 4). The reductions in CFU for other MAbs (from the remaining hybridoma lines) were found to be only between 11 and 16% (data not shown). To confirm the fungicidal activity of MAb A9, conidia of A. fumigatus were incubated in presence of antibody for 18 h and stained with propidium iodide and fluorescein diacetate. The dead cells were stained with propidium iodide, while fluorescein diacetate stained both live and dead cells. More than 33% of cells were found dead at 50 mg/ml of MAb A9, while treatment with irrelevant antibody caused 14.3% death at same concentration. A dose-dependent death of A. fumigatus conidia due to MAb A9 occurred, where a maximum of 60% cell death was observed at a concentration of 400 μg/ml of MAb A9 (Fig. 5). The negative controls (DPBS treated) did not show any effect. Further, the FACS analysis of papain-treated MAb showed 59% death of A. fumigatus spores, indicating that fungal cell death was not due to agglutination (Fig. 5). The fungicidal activity of MAb A9 was also confirmed by MTT reduction assay, where 25.76% (P < 0.003) hyphal damage was observed compared to the control and to treatment with an irrelevant MAb.

FIG. 4.

In vitro fungicidal activity of MAb A9 against A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. terreus, and A. niger measured by the reduction in number of CFU compared to the control with an irrelevant MAb. Values are means of triplicate determinations ± standard errors of the means. Differences in fungicidal activity between A. fumigatus spores treated with MAb A9 and irrelevant MAb were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001) as determined by the Student t test.

FIG. 5.

Dose-response bar graph generated from FACS analysis, showing the percentage of dead cells at different concentrations of MAb A9 and concanavalin A, which causes agglutination. The figure shows that antibody-mediated agglutination is insufficient for killing of A. fumigatus conidia. Data presented are the averages from three experiments.

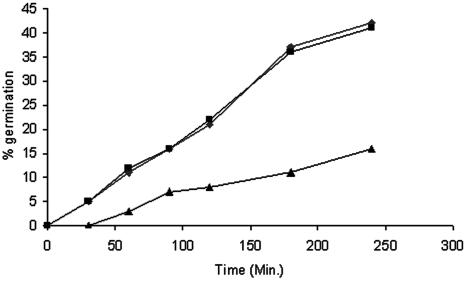

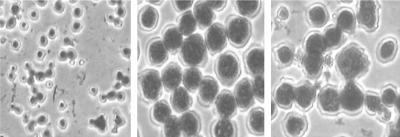

Swollen conidia were used for in vitro testing of germination of A. fumigatus against MAb A9. Since the growth was defined on the basis of visible mycelium formation, conidia should germinate and produce sporelings for monitoring of the growth inhibition and fungicidal activity of MAb. The germination of swollen conidia at 37°C in RPMI 1640 was achieved in a multistep process. During the initial 30 min of incubation, germination occurred only in control and irrelevant MAb-treated conidia. Treatment with MAb A9 resulted in a delay in this process, and only 16% germination was observed after 4 h of incubation, compared to 42% germination for both controls (Fig. 6). Compared to the control, phagocytosis of A. fumigatus conidia was enhanced by coincubation of conidia with MAb A9 (Fig. 6). Further, conidia treated with MAb A9 and coincubated with macrophages did not show a change in phagocytosis, thereby indicating that MAb A9 was independent of complement (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

In vitro effect of MAb A9 on germination of A. fumigatus conidia. Swollen A. fumigatus conidia (1.0 × 103) were incubated at 37°C with 50 mg of MAb A9 in 100 μl RPMI 1640. At selected time intervals, percent germination was calculated. A total of 100 conidia per field were counted at a magnification of ×400, and the mean value from three independent experiments was calculated. ⧫, control; ▪, irrelevant IgG; ▴, MAb A9.

FIG. 7.

Alveolar macrophages (J774 cell line) showing phagocytosis of A. fumigatus conidia. (Left) Conidia without any treatment (with MAb A9) were cocultured with macrophages and served as a control. (Middle) Conidia treated with MAb A9 for 18 h and then cocultured with macrophages, showing more phagocytosed conidia than the control. (Right) Conidia treated with MAb A9 which was heated to 56°C for inactivation of complement and then cocultured with macrophages exhibited phagocytosis similar to that in the middle panel, indicating complement-independent phagocytosis.

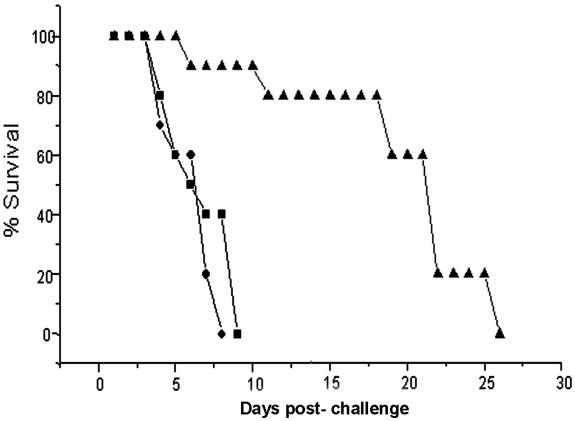

In vivo, MAb A9 exhibited good antifungal activity in a murine model of aspergillosis. A reduction in CFU of more than 4 log10 units was observed in kidney tissue of experimental mice compared to controls (Fig. 8). Because of these results, another experiment was carried out to see the effect of MAb A9 on the survival of experimental mice infected with A. fumigatus. The MST of mice was calculated on the basis of observations made up to 26 days. A significant increase in the MST of mice treated with MAb A9 (19.5 days) compared to control mice (7.1 days) and mice treated with an irrelevant MAb IgG (6.1 days) was observed (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

Effect of MAb A9 on the reduction in CFU from kidney tissue of experimental mice. A reduction in CFU of >4 log10 units was observed in kidney tissue of BALB/c mice challenged with A. fumigatus (2.0 × 105 cells per mouse) and MAb A9 administered prophylactically 2 h before infection via the tail vein. The difference between MAb A9-treated groups and the control group (without treatment) was significant (P < 0.001 according to Student t test).

FIG. 9.

Protective effect of MAb A9 against systemic aspergillosis in experimental mice. Survival rates of MAb A9-vaccinated mice compared to those of control mice (▪), mice treated with an irrelevant IgG (⧫), and MAb A9-immunized mice (▴). Data represent % survival recorded daily for 26 days postchallenge. Differences in survival rates (on day 26) between MAb A9- and irrelevant IgG-immunized mice were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001 as assessed by the log rank test).

DISCUSSION

Two fungal pathogens for which the role of antibody has been extensively studied are Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans (2). Candidacidal antibodies against C. albicans have been reported, where the target was located in the cell wall of Candida (15, 27, 32). Recently a humanized MAb directed against heat shock protein (HSP90) has entered clinical trials for the treatment of candidiasis. This antibody also has its target in the cell wall of C. albicans. Thus, it has been proposed that selective antibodies directed against specific epitopes may be protective against local and systemic infection and may form the basis for immunotherapy. The protective efficacy of MAbs to C. neoformans depends on the isotype (29, 42). The importance of isotype in protection was established when an IgG3 antibody was converted from a nonprotective antibody into a protective antibody by isotype switching to IgG1 (42). The efficacy of the murine isotypes in prolonging survival in mice was IgG1 > IgA and IgM > IgG3 (29). In the present study, MAb A9, which is IgG1 and was generated against cell wall glycoprotein of A. fumigatus, showed promising results in vitro as well as in vivo. MAb A9 has the agglutinating property, but the protection against A. fumigatus was not due to agglutination as indicated by the FACS analysis, where about 60% cell death was observed. In the case of C. neoformans, it has been proved that antibody-mediated agglutination is insufficient for protection against C. neoformans (28).

MAb A9 generated against the cell wall protein of A. fumigatus in the present study not only was capable of reducing CFU in a focal organ, the kidney, in experimental mice (Fig. 8) but also enhanced the MST significantly (P < 0.001) compared to negative controls as well as to animals treated with irrelevant MAb against C. albicans (Fig. 9). These results were in agreement with the in vitro findings, where a 94.8% reduction in CFU (about 60% cell death in FACS analysis) was observed against spores of A. fumigatus, followed by A. niger DSM 2182, A. terreus DSM 826, and A. flavus (Fig. 4). However, no such effect was observed against the other clinical isolates (Candida albicans ATCC 10231, C. krusei ATCC 6258, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC 66031, Sporothrix schenckii, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes), thereby indicating the specificity of MAb A9 for the species of Aspergillus tested.

The efficacy of any particular MAb depends on several variables, such as the characteristics of the targeted antigen, its function, and its cell surface density, as well as characteristics of the MAb, including specificity, avidity, and isotype (1). When a fungal spore germinates, it produces a hypha, which in turn grows by increasing in length through the accumulation of newly formed substances on the hyphal wall (8). During growth phase, galactomannan is incorporated into the fungal cell wall (12). In the present study, MAb A9, which was produced and identified as MAb IgG1 by using an isotyping kit, was directed against a proteinaceous epitope of a glycoprotein of >95 kDa as proved by glycoprotein PAS staining and deglycosylation experiments (Fig. 2). The cell surface characteristics of resting conidia are altered during swelling and germination, and this modification leads to the changes in the inner wall molecules (40). MAb A9 could enhance the time required for germination (Fig. 6), thus indicating that MAb A9 may have stopped or at least reduced the modification in the inner wall structure, which is crucial for fungal development to some extent.

Immunofluorescence microscopy with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG revealed that the epitope is uniformly distributed over the entire surface of germinating hyphae as well as over the swollen conidia (Fig. 1). Complement collections and antibodies promote attachment (opsonization) and identification of fungi by various receptors (34). In this study, MAb A9 uniformly opsonized the cell surface and was found to be protective in an experimental murine model of invasive aspergillosis. This was supported by the results of phagocytosis assays, where an increased number of A. fumigatus conidia exposed to MAb A9 were engulfed by macrophages (Fig. 7).

The in vitro and in vivo results of this study also show that MAb A9 binds with this antigen and blocks its functions, resulting in a reduction in growth. This antibody was found to have therapeutic efficacy in a murine model of invasive aspergillosis, and immunoblotting performed with pooled sera and MAb A9 (Fig. 2) identified the same protein band that was common between the two, showing that this protein induced an immune response in humans as well. Hence, it might be protective against A. fumigatus infection in humans. Currently there are a considerable number of reports in the literature on the production of MAbs against Aspergillus species, although in most cases these antibodies showed cross-reactivity with other pathogenic fungi (13, 18).

By enhancing the immune response of immunocompromised hosts, antifungal resistance can be reduced. The specific interactions between monoclonal antibodies and fungal cell wall molecules have many important implications; for example, it has been proved that antibodies play an important role in setting the initial host defense against fungi and can be protective against fungal infections. The therapeutic efficacy of antifungal agents is limited without the help of host immune reactivity (3, 35). In conclusion, MAb A9 may be beneficial as an immunoprobe for recognition of epitopes responsible for the shared antigenicity of fungal glycoproteins, for examining their expression during hyphal and conidial morphogenesis, and for immunotherapy against A. fumigatus infections in particular and aspergillosis in general.

Acknowledgments

We thank the director and the head of the Fermentation Technology Division, CDRI, Lucknow, India, for providing facilities.

A.K.C. thanks the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, for a Senior Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

CDRI communication no. 6720.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breedveld, F. C. 2000. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Lancet 355:735-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casadevall, A. 1995. Antibody immunity and invasive fungal infections. Infect. Immun. 63:4211-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadevall, A., A. Cassone, F. Bistoni, J. F., Cutler, W. Magliani, J. W. Murphy, L. Polonelli, and L. Romani. 1998. Antibody and/or cell-mediated immunity, protective mechanisms in fungal disease: an ongoing dilemma or an unnecessary dispute? Med. Mycol. 36:95-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova, M., J. P. Martinez, and W. L. Chaffin. 1990. Fab fragments from a monoclonal antibody against a germ tube mannoprotein block the yeast-to-mycelium transition in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 58:3810-3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassone, A., A. Torosantucci, M. Boccanera, G. Pellengrini, C. Palma, and G. Malavasi. 1988. Production and characterization of a monoclonal antibody to a cell surface, glucomannoprotein constituent of Candida albicans and other pathogenic Candida species. J. Med. Microbiol. 27:233-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cenci, E., A. Mencacci, A. Spreca, C. Montagnoli, A. Bacci, K. Perruccio, A. Velardi, W. Magliani, S. Conti, L. Polonelli, and L. Romani. 2002. Protection of killer anti-idiotypic antibodies against early invasive aspergillosis in a murine model of allogeneic T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation. Infect. Immun. 70:2375-2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaffin, W. L., J. L. Lopez-Ribot, M. Casanova, D. Gozalbo, and J. P. Martinez. 1998. Cell-wall and secreted proteins of Candida albicans: identifications, function, and expression. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:130-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deacon, J. W. 1997. Modern mycology. Blackwell Science, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 9.Denning, D. W. 1998. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:781-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeWit, M. Y. L., and P. R. Klaster. 1988. Purification and characterization of a 36kDa antigen of Mycobacterium leprae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:1541-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenelon, L. E., A. J. Hamilton, J. I. Figueroa, M. A. Bartholomew, M. H. Allen, P. McCarthy, and R. J. Hay. 1999. Production of specific monoclonal antibodies to Aspergillus species and their use in immunohistochemical identification of aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1221-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontaine, T., C. Simenel, G. Dubreucq, O. Adam, M. Delepierre, J. Lemoine, C. E. Vorgias, M. Diaquin, and J. P. Latge. 2000. Molecular organization of the alkali-insoluble fraction of Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27594-27607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fratamico, P. M., and H. R. Buckley. 1991. Identification and characterization of an immunodominant 58-kDa antigen of Aspergillus fumigatus recognized by sera of patients with invasive aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 59:309-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgopapaadakou, N. H. 1998. Antifungals: mechanism of action and resistance, established and novel drugs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:547-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyard, C., E. Dehecq, J. P., Tisser, L. Polonelli, E. Dei-Cas, J. C. Cailliez, and F. D. Menozii. 2002. Involvement of [beta]-glucans in the wide-spectrum antimicrobial activity of Williopsis saturuns var marakii MUCL 41968 killer toxin. Mol. Med. 8:686-694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han, Y., R. P. Morrison, and J. E. Cutler. 1998. A vaccine and monoclonal antibodies that enhance mouse resistance to Candida albicans vaginal infection. Infect. Immun. 66:5771-5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han, Y., T. R. Kozel, M. X. Zhang, R. S. MacGill, M. C. Carroll, and J. E. Cutler. 2001. Complement is essential for protection by an IgM and IgG3 monoclonal antibodies against experimental, hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. J. Immunol. 167:1550-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar, A., and V. P. Kurup. 1993. Murine monoclonal antibodies to glycoprotein antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus show cross-reactivity with other fungi. Allergy Proc. 14:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, M., and P. K. Shukla. 2005. Use of PCR targeting of internal transcribed spacer regions and single-stranded conformation polymorphism analysis of sequence variation in different regions of rRNA genes in fungi for rapid diagnosis of mycotic keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:662-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lartey, P. A., and C. M. Moehle. 1997. Recent advances in antifungal agents. p. 151-160. In J. J. Plattner (ed.), Annual reports in medicinal chemistry. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Leach, B. S., J. F. Collown, Jr., and W. W. Fish. 1980. Behaviour of glycopolypeptides with empirical molecular weight estimation method. I. In sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biochemistry 19:5734-5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levitz, S. M., and R. D. Diamond. 1985. A rapid colorimetric assay of fungal viability with the tetrazolium salt MTT. J. Infect. Dis. 152:938-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magliani, W., S. Conti, F. De Bernardis, M. Gerloni, D. Bertolotti, P. Mozzoni, A. Cassone, and L. Polonelli. 1997. Therapeutic potential of antiidiotypic single chain antibodies with yeast killer toxin activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manavathu, E. K., J. Cutrigh, and P. H. Chandrasekar. 1999. Comparative study of susceptibility of germinated and ungerminated conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus to various antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:858-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moragues, M. D., M. J. Omaetxebarria, N. Elguezabal, M. J. Sevilla, S. Conti, L. Polonelli, and J. Ponton. 2003. A monoclonal antibody directed against a Candida albicans cell-wall mannoprotein exerts three anti-C. albicans activities. Infect. Immun. 71:5273-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee, J., G. Nussbaum, M. D. Scharff, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Protective and non-protectivemonoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans originating from one B-cell. J. Exp. Med. 181:405-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee, J., M. D. Scharff, and A. Casadevall. 1992. Protective murine monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 60:4534-4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostubo, T., K. Maruyama, S. Maesaki, Y. Miyazaki, E. Tanaka, T. Takizawa, K. Moribe, K. Tomono, T. Tashiro, and S. Kohno. 1998. Long-circulating immunoliposomal amphotericin B against invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:40-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polonelli, L., N. Segny, S. Conti, M. Gerloni, D. Bertolotti, C. Cantelli, W. Magliani, and J. C. Cailliez. 1997. Monoclonal yeast killer toxin-like candidacidal anti-idiotypic antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:142-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polonelli. L., F. De Bernardis, S. Conti, M. Boccanera, W. Magliani, M. Gerloni, C Cantelli, and A. Cassone. 1996. Human natural yeast killer toxin-like candidacidal antibody. J. Immunol. 56:1880-1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porter, R. R. 1959. The hydrolysis of rabbit y-globulin and antibodies with crystalline papain. Biochem. J. 73:119-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romani, L. 2002. Innate immunity against fungal pathogens, p. 401-432. In R. A. Calderone and L. R. Cihlar (ed.), Fungal pathogenesis. Principles and clinical applications Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 35.Romani, L. 2004. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sable, C. A., and G. R. Donowitz. 1994. Infections in bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.San Millan, R., P. Ezkurra, G. Quindos, R. Robert, J. M. Senet, and J. Ponton. 1996. Effect of monoclonal antibodies directed against Candida albicans cell wall antigens on the adhesion of the fungus to polystyrene. Microbiology 142:2271-2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ste-Marie, L. S. Senechal, M. Boushira, S. Garzon, H. Strykowski, L. Pedneault, and L. de Repentigny. 1990. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to cell wall antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 58:2105-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacylamide gets to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some application. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tronchin, G., K. Esnault, G. Renier, R. Filmon, D. Chabasse, and J. F. Bouchara. 1997. Expression and identification of laminin-binding protein in Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect. Immun. 65:9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wingard, J. R. 1999. Fungal infections after bone marrow transplant. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 5:55-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan, R., A. Casadevall, G. Spira, and M. D. Scharff. 1995. Isotype switching from IgG3 to IgG1 converts a non-protective murine antibody to C. neoformans into a protective antibody. J. Immunol. 154:1810-1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]