Abstract

Lacto-N-fucopentaose III (LNFPIII) is a human milk sugar containing the biologically active Lewis X (LeX) trisaccharide. LNFPIII/LeX is also expressed by immunosuppressive helminth parasites, by bacteria, and on a number of tumor/cancer cells. In this report, we first demonstrate that LNFPIII activates macrophages in vitro as indicated by upregulation of Gr-1 expression on F4/80+ cells. Further, we investigated the effect of LNFPIII-activated macrophages on NK cell activity. We found that LNFPIII-stimulated F4/80+ cells were able to activate NK cells, inducing upregulation of CD69 expression and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production. The experiments show that NK cell activation is macrophage dependent, since NK cells alone did not secrete IFN-γ in response to LNFPIII. Furthermore, we found that activation of NK cells by glycan-stimulated macrophages required cell-cell contact. As part of the cell-cell contact mechanism, we determined that CD40-CD40L interaction was critical for IFN-γ secretion by NK cells, as the addition of anti-CD40L antibodies to the coculture blocked IFN-γ production. We also demonstrated that LNFPIII-stimulated macrophages secrete prostaglandin E2, interleukin-10 (IL-10), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) but a very low level of IL-12. Interestingly, addition of anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-10, or anti-IL-12 monoclonal antibodies did not significantly alter NK cell activity. Our data show that these soluble mediators are not critical for LNFPIII-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells and provide further evidence for the importance of cell-cell contact and CD40-CD40L interactions between macrophages and NK cells.

The main role of innate immunity is to respond to pathogens with maximum speed and potency, developing a first line of defense against infection (25). Innate responses to pathogens involve cross talk between antigen-presenting cells and effector cell populations through cell-cell contact and/or via soluble mediators. Macrophages and NK cells are two innate responder cell populations. NK cells are able to lyse a variety of cells, including tumor and virus-infected cells, spontaneously in the absence of antigen-specific recognition and clonal expansion (43). The cytotoxic activity of NK cells has been correlated with their gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing capacity (9). Further, IFN-γ-producing NK cells have been shown to activate phagocytic cells and prime antigen-presenting cells (13, 45).

Several studies have examined the interactions of NK cells and dendritic cells (DCs), noting that activated NK cells can induce maturation of DCs and, similarly, both immature and mature DCs can activate NK cells (2, 10, 13, 14, 29). Surprisingly, little is known about interactions between NK cells and macrophages, despite the importance of macrophages in innate immunity (7, 8, 34). A recent study by Siren et al. (35) demonstrated that Sendai virus-infected macrophages activate NK cells in a contact- and IFN-α-dependent process. Further, Pneumocystis carinii and Listeria monocytogenes have both been shown to induce macrophage-mediated NK cell activation in SCID mice (46, 51, 52). Thus, similar to DC-NK cell interactions, it is likely that cross talk between NK cells and macrophages influences maturation/differentiation events as well as regulating functional activity.

In addition to intracellular pathogens, two different glycans, lacto-N-fucopentaose III (LNFPIII) and LNnT, both found on helminth parasites, were shown to expand peritoneal macrophage populations capable of suppressing naive CD4+ T-cell responses (3, 40). The suppressor macrophages were characterized as F4/80+ and Gr1+. A similar population of F4/80+Gr1+ macrophages that induce T-cell anergy are expanded in mice infected with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni (36). However, neither the study on schistosome infection nor those using helminth glycans to expand F4/80+Gr1+ suppressor macrophages examined macrophage-NK cell interactions.

We decided to investigate whether LNFPIII-activated macrophages interacted with NK cells. To perform this analysis, we developed an in vitro model of LNFPIII activation/differentiation of peritoneal macrophages and studied macrophage-NK cell interactions in the presence or absence of LNFPIII. Here we found that when NK cells were cocultured with LNFPIII-activated macrophages, they upregulated CD69 and produced IFN-γ, with the macrophages producing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) but not interleukin-12 (IL-12). Direct cell-cell contact with LNFPIII-stimulated macrophages was necessary for NK cell activation, as well as CD40-CD40L interaction. In contrast, addition of anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-12, or anti-IL-10 antibodies (Abs) did not significantly reduce NK cell production of IFN-γ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c, C57BL/6, and SCID mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of the Harvard School of Public Health.

Media and reagents.

The neo-glycoconjugate LNFPIII-dex and the carrier dextran were provided by Neose Technologies Inc., Horsham, PA. The neo-glycoconjugate consisted on average of 12 LNFPIII (molecular weight, 853.8) molecules conjugated to a 40-kDa molecule of dextran. All batches of LNFPIII-dex and dextran were tested for levels of endotoxin by using the Limulus amoebocyte assay (Charles River Inc., ME). For cell culture, RPMI 1640 medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 0.005 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco).

Purified anti-mouse CD69-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and -phycoerythrin (PE), DX5-FITC and -PE, CD40-FITC, Gr1-PE, IFN-γ-PE, isotype control immunoglobulin G, and the Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus kit were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Rat anti-mouse F4/80-FITC and -Cy5 monoclonal Abs (MAbs) were purchased from Serotec (Raleigh, NC).

Cells and cell culture.

Splenocytes from SCID mice or peritoneal cells (PECs) from BALB/c mice were obtained as described previously (3). For NK cell and macrophage purification, DX5-PE and F4/80-FITC Abs (BD Biosciences), goat anti-FITC and anti-PE magnetic microbeads, BS separation columns, and varioMACS magnets (Miltenyi Biotec) were used. Flow cytometry showed >98% purity of both NK cells and macrophages.

Splenocytes or NK cells (1 × 106/ml/well) were cultured in 24-well plates or in Transwells (Costar; 0.4-μm pore size) for 24, 48, and 72 h with or without the following stimuli: dextran (50 μg/ml), LNFPIII-dex (50 μg/ml), and recombinant murine IL-2 (250 U/ml; PeproTech, NJ). The neutralization Abs anti-TNF-α (MP6-XT3) (10 μg/ml), anti-CD40L (CD154-MR1) (20 to 40 μg/ml), anti-IL-10 (JES5-16E3) (10 μg/ml), and anti-IL-12 (p40/p70, clone C17.8) (5 μg/ml) and appropriate isotype control Abs were obtained from BD Biosciences.

Flow cytometry.

Freshly isolated or cultured splenocytes and PECs (2 × 105 to 5 × 105) were transferred to 12- by 75-mm polystyrene tubes and washed with fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide). Cells were stained with combinations of MAbs for 30 min on ice in the dark and washed twice in FACS buffer. For intracellular cytokine staining, brefeldin A was added and left for the last 2 to 4 h of incubation at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with the use of a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit and stained with anticytokine MAbs for 30 min on ice in the dark. Acquisition of cells was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). A minimum of 20,000 events were acquired for analysis. Cell populations were analyzed using CELLQUEST software (BD Biosciences).

ELISPOT assay.

The number of IFN-γ-producing cells was measured using the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) kit assay (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, splenocytes (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in Millipore MultiScreen-HA plates (coated with anti-IFN-γ Ab) for 24 or 48 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in complete medium alone or supplemented with dextran or LNFPIII-dex. The wells were then washed and incubated overnight at 4°C with biotinylated anti-IFN-γ Abs. Reactions were visualized using avidin-alkaline phosphastase, and 5-bromo-4-chromo-3-indolylphosphatase p-toluidine salt, and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride substrate. The number of spots per 106 splenocytes, which represents the number of IFN-γ-producing cells, was counted with an ELISPOT reader (ImmunoSpot Analyzer; Cellular Technology Ltd., OH).

ELISA.

TNF-α and PGE2 kits were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Levels of IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-13, IL-4, and IL-5 were measured by capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, using capture and detection Abs from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance of differences among groups was determined by Student's t test. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Peritoneal macrophages respond to LNFPIII-dex stimulation in vitro.

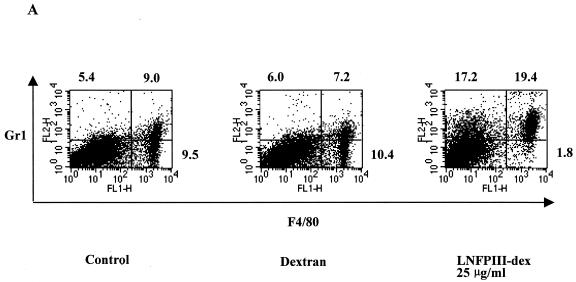

We previously demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of LNFPIII-dex led to the expansion of F4/80+, Gr1+, and CD11b+ PECs, which were functional suppressors of CD4+ T cells (3). Initially, we determined if stimulation of naive PECs in vitro with LNFPIII-dex would induce expression of Gr1 on F4/80+ cells, similar to what we observed following intraperitoneal injection of LNFPIII. Figure 1A shows representative data from one of three experiments examining phenotypic changes in PECs stimulated with LNFPIII-dex in vitro. At 48 h after in vitro stimulation with LNFPIII-dex, the number of Gr1+ F4/80+ PECs was 19.4%, compared to fewer than 10% of PECs stimulated with medium or dextran. In addition, and importantly, Fig. 1A shows that by 48 h, essentially all of the F4/80+ PECs stimulated with LNFPIII-dex had become Gr1+, compared to 41% or 48% of Gr1+ cells in PECs stimulated with dextran or medium, respectively. Approximately 47% of Gr1+ cells from LNFPIII-dex-stimulated PECs did not express F4/80, and cytospins showed that these cells were neutrophils (unpublished observation). Thus, in vitro stimulation of naive PECs with LNFPIII-dex induces peritoneal F4/80+ macrophages to express surface Gr1.

FIG. 1.

Peritoneal macrophages are able to respond to LNFPIII-dex stimulation in vitro. A. PECs were obtained from the peritoneal cavities of BALB/c mice and incubated (1 × 106/ml) for 48 h in the presence of 25 μg/ml LNFPIII-dex, dextran, or medium (control). Expression of Gr1 markers on F4/80+ cells was measured by flow cytometry. Data from one of three independent experiments are shown. B. Supernatants from cultured PECs with or without LNFPIII-dex were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h. Levels of IL-10, PGE2, and TNF-α (mean ± standard deviation) were measured by ELISA. Black bars, control (medium or dextran) PECs; hatched bars, PECs stimulated by 25 μg/ml of LNFPIII-dex. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 to 0.001 (statistically significant differences between control and LNFPIII-dex-treated PECs).

We next examined cytokine production from PECs stimulated with LNFPIII-dex for 24, 48, and 72 h in vitro, measuring the levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, IL-12, and PGE2 by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1B, the levels of TNF-α, IL-10, and PGE2 were significantly higher in supernatants from LNFPIII-dex-stimulated PECs than in supernatants from control cultures at 72 h. The levels of TNF-α remained high through 72 h of culture, whereas PGE2, while significantly higher than control supernatants, decreased by 48 h and 72 h. All other cytokines were not detectable.

In an earlier study we demonstrated that the ability of LNFPIII-dex-expanded F4/80+Gr1+ macrophages to suppress naive CD4+ T-cell proliferation was IFN-γ dependent (3). Therefore, we decided to investigate whether NK cells were a possible source of IFN-γ during LNFPIII-dex macrophage activation. For these studies we used SCID mice, which have NK cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and granulocytes but no T or B cells. FACS analysis of splenocytes from SCID mice demonstrated the presence of approximately equal percentages of NK cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, with a smaller proportion (about 5%) of CD11c+ dendritic cells (data not shown). To perform macrophage-NK cell experiments, we needed to demonstrate that SCID splenic macrophages would respond to LNFPIII-dex stimulation in a manner similar or identical to that of PEC macrophages. We found that LNFPIII-dex-stimulated SCID splenocytes upregulated expression of Gr1, B7.1, and B7.2 on F4/80+ cells (unpublished observation), demonstrating that SCID splenic macrophages become activated in response to LNFPIII-dex in the absence of T and B cells, similar to what we have seen for PEC macrophages.

NK cells produce IFN-γ via a contact-dependent mechanism with LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages.

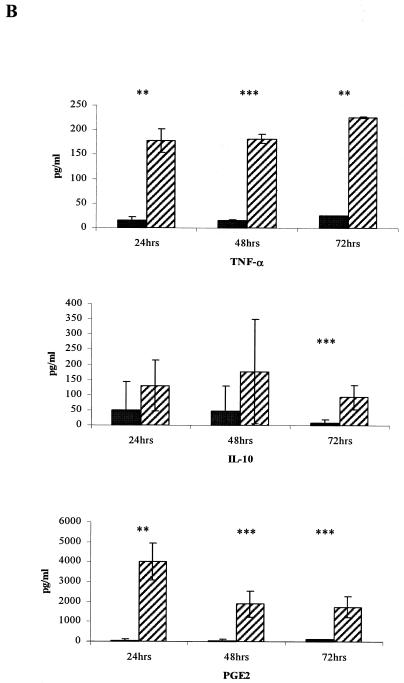

To determine if LNFPIII-stimulated macrophages interact with NK cells, we measured the expression of CD69, an early activation marker on SCID splenic NK cells, which allowed analysis in the absence of IFN-γ-producing T cells. We performed experiments with purified NK cells and macrophage cocultures in the presence of LNFPIII-dex and observed an upregulation of CD69 expression on NK cells. Figure 2 shows that at 48 h, CD69 expression was upregulated on NK cells in cultures where LNFPIII was present compared to cultures where dextran was added. Upregulation of CD69 was dependent on time in culture with LNFPIII-dex, as we were unable to detect significant levels of CD69 at 24 h of culture. To rule out the possibility that LNFPIII-dex was directly stimulating NK cells, we added LNFPIII-dex to purified NK cells, and found that this direct stimulation of NK cells did not lead to upregulation of CD69 expression. Lastly, we performed transwell experiments to determine if the ability of LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages to activate NK cells was contact dependent. NK cells were plated to the bottom of transwells. Figure 2 shows that when LNFPIII-dex was added to both the NK cell and macrophage compartments of transwell cultures, we were unable to detect an increase in CD69 expression on NK cells, demonstrating that NK cell activation required direct contact with LNFPIII-dex-treated macrophages.

FIG. 2.

Expression of CD69 on DX5+ splenocytes stimulated for 48 h with LNFPIII. Splenocytes were obtained from SCID mice as described previously (3). DX5+ and F4/80+ cells were purified according to Miltenyi Biotec instructions. Cells were cultured for 48 h with dextran or LNFPIII-dex in 24-well plates with or without transwells at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml and then harvested and labeled with anti-CD69-FITC and anti-DX5-PE Abs. The representative histograms reflect the proportion of CD69-positive cells among DX5+ cells. Thick lines, CD69 expression of LNFPIII-dex-stimulated cells. Thin lines, CD69 expression of control (dextran-stimulated) cells. Upper histogram, NK cells plus macrophages; middle histogram, purified DX5+ cells; lower histogram, purified DX5+ cells separated from purified F4/80+ cells in transwells. These results were reproduced in five separate experiments.

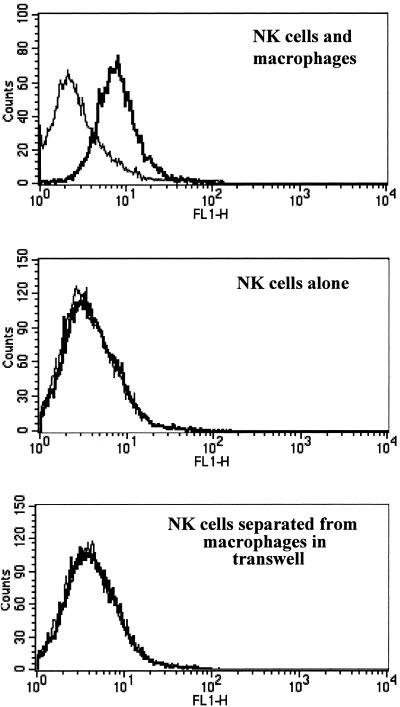

In addition to CD69 expression, NK activity can also be estimated by production of IFN-γ (9). We used intracellular staining for IFN-γ as well as an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as readouts for NK activation. To determine if macrophages and NK cells required contact for induction of NK cell production of IFN-γ, we cocultured control or LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages with NK cells in 24-well plates and in transwell plates for 48 h in the presence of IL-2. Preliminary experiments showed that exogenous IL-2 was required in order to detect IFN-γ+ cells by intracellular staining. Figure 3 shows an approximate fivefold increase in IFN-γ+ DX5+ cells from cultures containing LNFPIII-dex-activated macrophages compared with cultures with dextran-treated macrophages (10.65% versus 2.15%, respectively). In contrast, when NK cells and macrophages were separated by a semipermeable membrane, we observed no differences in the numbers of IFN-γ-positive cells between groups (data not shown). Using an ELISA to measure secreted IFN-γ in cocultures, we found that the level of IFN-γ in LNFPIII-dex cultures was roughly twofold higher than that in dextran cultures; however, the differences were not significant (data not shown). As expected, there was no detectable IFN-γ in supernatants from transwell cultures, and, similar to the intracellular cytokine staining results, levels of IFN-γ in supernatants from cultures without IL-2 were not detectable (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ+ DX5+ cells from spleens of SCID mice after 48 h of stimulation. Splenocytes were obtained from SCID mice and purified as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Cocultured cells were stimulated with dextran plus IL-2 or with LNFPIII-dex plus IL-2 for 48 h. Brefeldin A was added 4 h before the end of the cultures. Cells were then harvested, stained with anti-DX5-FITC Abs, and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-IFN-γ-PE Abs. In FACS analysis, NK cells were gated at forward scatter versus side scatter. Isotype control Abs were used in each experiment. Data shown are representative of five experiments.

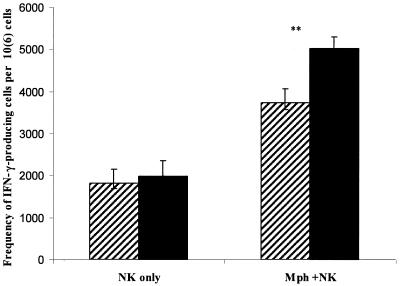

We also performed ELISPOT assays in parallel with intracellular cytokine staining experiments. ELISPOTs result at 24 h of cell culture demonstrated an insufficient number of IFN-γ-producing cells for significant quantification. However, at 48 h the number of IFN-γ-producing cells seen in NK cell-macrophage cocultures containing LNFPIII-dex was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than those obtained from controls (Fig. 4). As expected, purified DX5+ cells stimulated with LNFPIII-dex did not produce IFN-γ.

FIG. 4.

The presence of LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages in coculture with NK cells increases the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells. Splenocytes were obtained from SCID mice as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and DX5+ and F4/80+ cells were purified according to Miltenyi Biotec instructions. Cells were cultured for 48 h with dextran (hatched bars) or LNFPIII-dex (solid bars) in ELISPOT plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. Purified DX5+ cells alone or in combination with purified F4/80+ cells (isolated simultaneously with DX5+ cells) were cultured at the same concentration of cells per well. The number of IFN-γ-producing cells in response to stimulation was analyzed in an ELISPOT assay as described in Materials and Methods. The number of IFN-γ-producing cells was recalculated per 106 splenocytes. Averages ± standard deviations from five performed experiments are shown. **, statistically significant differences from control stimulation (P < 0.001).

Because LNFPIII-dex did not directly stimulate NK cells, we next performed experiments to determine if F4/80+ cells cultured for 2 h with LNFPIII-dex and then washed prior to addition to NK cells would induce their production of IFN-γ as assessed by ELISPOT. We observed that LNFPIII-prestimulated F4/80+ cells were able to significantly increase the frequency of IFN-γ-producing NK cells (data not shown). This effect was macrophage dependent, as coculture of DX5+ cells with F4/80-negative cells in the presence of LNFPIII-dex did not induce IFN-γ secretion (data not shown). To verify that macrophage activation of NK cells is not strain dependent, we performed experiments simultaneously using a Th2-type mouse strain (BALB/c) and a Th1-type strain (C57BL/6), obtaining similar responses to LNFPIII stimulation (data not shown).

To rule out other cell populations capable of responding to LNFPIII-dex and thus activating NK cells, we performed experiments where we depleted CD11c+ cells from splenocytes of SCID mice and found that this did not alter the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells (data not shown). Further, while we noticed that the frequency of IFN-γ+ cells was higher in cocultures of purified DX5+ and F4/80+ cells than in cocultures of unseparated splenocytes from SCID mice, the proportions of responding cells were similar in both cases.

To ensure that endotoxin was not contributing to the observed effects of LNFPIII-dex in the ELISPOT assay, we performed identical experiments where polymyxin B (Sigma) was added to cultures at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Cultures containing polymyxin B had similar numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells as cultures without polymyxin B, showing that induction of IFN-γ production by NK cells via coculture with LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages was not due to the presence of endotoxin (0.2 ng/ml) in LNFPIII-dex.

Taken together, our data show that NK cells do not produce IFN-γ in direct response to LNFPIII-dex stimulation but become activated in a contact-dependent mechanism when cocultured with LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages.

Role of cytokines in LNFPIII-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells.

Soluble factors are known regulators of cell activity. Thus, we analyzed production of cytokines from SCID splenocytes at 48 h after LNFPIII-dex stimulation in vitro and observed increased levels of TNF-α and PGE2 (Fig. 5A). The addition of exogenous IL-2 to cultures increased production of both TNF-α and PGE2, and the difference between LNFPIII-stimulated and unstimulated cells was highly significant (P < 0.001). We also detected low levels of IL-10 (<10 pg/ml) and IL-12 (50 to 60 pg/ml) but were unable to detect IL-2 or nitric oxide (NO) (data not shown). Interestingly, all SCID splenocyte cultures produced large amounts of transforming growth factor β, with no difference between control and LNFPIII-dex-stimulated cells. The low level of IL-10 production from LNFPIII-dex-stimulated SCID splenocytes was surprising, since production of IL-10 from LNFPIII-dex-stimulated BALB/c PECs was high. These observations suggest that cells other than macrophages and NK cells produce IL-10 in response to LNFPIII-dex or upon coculture with LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages. Unlike those of IL-10, the levels of PGE2 were comparable between LNFPIII-dex-stimulated SCID splenocytes and BALB/c PECs.

FIG. 5.

Role of cytokines in LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells. A. Splenocytes from SCID mice were obtained as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and cultured for 48 h with dextran, LNFPIII-dex, dextran plus IL-2, or LNFPIII-dex plus IL-2. Supernatants were collected, and levels of PGE2 and TNF-α were analyzed by ELISA. Means ± standard deviations from one experiment are shown. *, statistically significant differences between control (dextran or dextran plus IL-2) and oligosaccharide-stimulated (LNFPIII-dex or LNFPIII-dex plus IL-2) samples (P < 0.001). Three experiments with similar results were performed. B. Anti-TNF-α or isotype control Abs were added to cell cultures stimulated with LNFPIII-dex plus IL-2 at 10 μg/ml for 48 h to an ELISPOT plate. The number of IFN-γ-producing cells was analyzed using the ELISPOT assay as described in Materials and Methods. The number of IFN-γ-producing cells incubated with isotype control Abs (gray bar) versus anti-TNF-α Abs (black bar) was calculated per 106 cells. Means ± standard deviations from one experiment are shown. Three experiments with similar results were performed. C. Expression of CD69 on DX5+ cells is shown as results from a representative experiment of five independent experiments. Shaded histogram, culture of cells in the presence of LNFPIII-dex; thick line, anti-TNF-α Abs were added to LNFPIII-dex-stimulated cells.

To determine if the elevated levels of TNF-α that we detected in our cultures played a role in LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage-induced NK cell activation, we performed neutralization experiments in which anti-TNF-α Abs were added to ELISPOT wells. Figure 5B demonstrates that the number of IFN-γ-producing cells was partially but not significantly decreased when cells were incubated for 48 h in the presence of anti-TNF-α Abs. Similarly, addition of anti-IL-10 and anti-IL-12 Abs to cocultures did not alter IFN-γ production from SCID cell cocultures (data not shown). Expression of CD69 on NK cells was also partially reduced after preincubation with anti-TNF-α Abs in coculture of NK cells with LNFPIII-activated macrophages (Fig. 5C).

CD40-CD40L interaction is critical for LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells.

In addition to cytokines and chemokines, costimulatory molecules are involved in cell-cell communication (1, 6, 16, 37, 47). In this study we observed an upregulation of CD80 and CD86 molecules on LNFPIII-dex-stimulated F4/80+ cells (data not shown) but did not detect an upregulation of CD28 on NK cells, even those NK cells which were IL-2 activated (data not shown). These data indicated that CD28/B7 molecules were not involved in NK cell-macrophage interaction, at least under our experimental conditions.

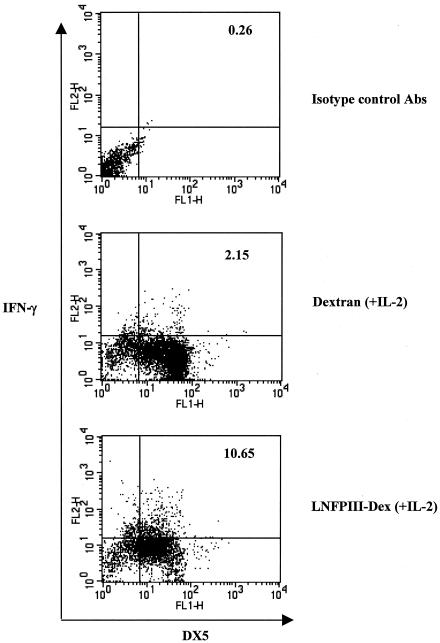

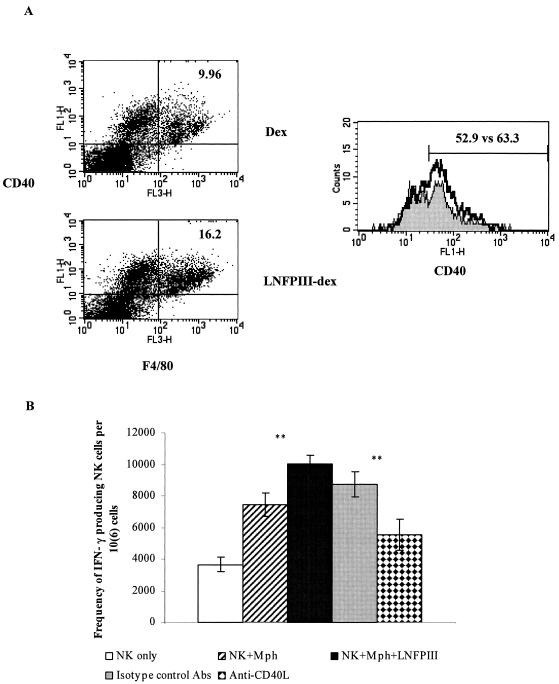

Since LNFPIII-dex stimulation of cells increased the total number of CD40+ F4/80+ cells as well as expression of CD40 on F4/80+ cells (Fig. 6A), we asked whether CD40 or CD40L plays a role in LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells. To investigate the possible role of CD40-CD40L in LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages and NK cell interaction, we added anti-CD40L blocking Abs to cultures of LNFPIII-activated F4/80+ and DX5+ cells. In each of five separate experiments, we found that the number of IFN-γ-producing cells in ELISPOT assays was significantly reduced (P < 0.001) in the presence of blocking anti-CD40L Abs (Fig. 6B), suggesting that CD40-CD40L interaction is an important step in driving activation of NK cells by LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages in vitro.

FIG. 6.

CD40-CD40L interaction is critical for LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage activation of NK cells. Splenocytes were obtained, cultured for 48 h, harvested, and stained as described in Materials and Methods. A. The number of CD40+ F4/80+ cells and expression of CD40 on F4/80+ cells were analyzed, and results shown here are from a representative experiment of three. In the upper right corners the numbers of CD40+ F4/80+ cells are presented. Shaded histograms, culture of cells in the presence of dextran; thick line, culture of cells in the presence of LNFPIII-dex. B. Cells were cultured in ELISPOT plates for 48 h in the presence of IL-2. The numbers of IFN-γ-producing DX5+ cells alone (open bar), DX5+ and F4/80+ cells with dextran (hatched bar), DX5+ and F4/80+ cells with LNFPIII-dex (black bar), DX5+ and F4/80+ cells blocked with isotype control Abs before LNFPIII-dex stimulation (gray bar), and DX5+ and F4/80+ cells blocked with anti-CD40L Abs before LNFPIII-dex stimulation (stippled bar) were calculated per 106 NK cells. Five experiments with similar results were performed. Means ± standard deviations from one experiment are shown. **, statistically significant differences from control samples (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that the neo-glycoconjugate LNFPIII-dex drives Th2-type responses in vivo, functioning as a Th2-type adjuvant for third-party antigens, and activates a population of Gr1+ F4/80+macrophages which suppress T-cell proliferation in an IFN-γ-dependent process (3, 26, 42). However, little is known about other functions (regulatory/activation) of these macrophages. The observation that LNFPIII-dex-driven suppressor macrophages functioned in an IFN-γ-dependent manner seemed at odds with the ability of LNFPIII-dex to induce anergy and Th2-type responses in vivo. NK cells are innate cells that produce large amounts of IFN-γ, in part because the IFN-γ locus in NK cells has been constitutively demethylated (39). Thus, in this study we focused on defining possible interactions between LNFPIII-dex-activated macrophages and NK cells leading to activation of NK cells and their production of IFN-γ. Among the parameters we examined were the requirement for cell-cell contact between LNFPIII-dex-activated macrophages and NK cells and the contributions of soluble mediators and costimulatory molecules, specifically CD40-CD40L.

Cytokine feedback loops between antigen-presenting cells and effector cells play important roles in their activation. Here we show that LNFPIII-dex stimulation of splenic macrophages leads to NK cell production of IFN-γ. To determine if cytokines produced by LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages might be involved in NK cell activation, we first determined the cytokine profile of LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages separately as well as in cocultures with NK cells. This analysis revealed that LNFPIII-dex induced production of PGE2, TNF-α, and IL-10 but little IL-12 from macrophages. Although IL-12 has been shown to activate NK cells through a STAT-4-dependent mechanism (41, 44), our finding about IL-12-independent activation of NK cells is consistent with studies showing that IFN-γ production from macrophage and NK cell cocultures was not always IL-12 dependent (34, 52). Our inability to detect significant levels of IL-12 in the cultures may have been due to the inhibitory effects of transforming growth factor β and possibly PGE2, both of which were elevated in cultures of LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages (23, 31).

Analysis of cytokine secretion by cocultured macrophages and NK cells demonstrated increased levels of TNF-α, which was expected since macrophages are known as classical producers of TNF-α. Further, it has been suggested that IL-2-induced maturation of NK cells is initiated by secretion of endogenous TNF-α (18). Our results show that addition of anti-TNF-α Abs to macrophage-NK cell cocultures partially reduced CD69 expression on NK cells but did not significantly decrease IFN-γ production by NK cells. Similar decreasing CD69 expression was demonstrated in a recent study on NK-DC interaction when anti-TNF-α neutralizing Abs were used in combination with anti-IFN-α/β Abs during poly(I · C) activation (14). Thus, TNF-α has an effect on NK cell phenotype in coculture with LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages, but TNF-α neutralization is not sufficient to reduce IFN-γ in vitro. At this time we cannot exclude the possibility that TNF-α production may be important for other processes such as maturation or apoptosis, as has been indicated in several studies (4, 19, 48, 50).

In regard to costimulatory molecules, we observed that LNFPIII-dex-stimulated F4/80+ cells cocultured in the presence of NK cells upregulated surface CD80 and CD86 (data not shown). Upregulation of CD80 and CD86 on macrophages may be the result of feedback from activated NK cells, since we did not detect CD28 on cocultured NK cells or on IL-2-activated NK cells, consistent with other observations (15). Although CD28/B7 interactions have been reported to partially regulate NK cell IFN-γ in Toxoplasma gondii-infected mice, a CD28-independent pathway of regulation was also recently shown (17, 22, 49, 53).

Our experiments comparing cocultures with and without transwells clearly show that cell-cell contact was required for LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages to induce NK cell activation. Several other studies have reported that direct cell contact was required for macrophage activation of NK cells (7, 34, 51). Similarly, multiple studies have shown contact-dependent activation of murine NK cells by DCs (1, 11, 13, 14, 29). While cell-cell contact is clearly a critical factor in macrophage/DC-NK cell interactions, the molecular mechanisms through which cell-cell contact mediates this response remain to be elucidated. For example, cell-cell interaction of CD40-CD40L was found to be important in a number of studies (5, 12, 34, 37, 38, 47). In this study, we observed that LNFPIII-dex increased the frequency of CD40+ F4/80+ cells as well as the upregulation of expression of CD40 on F4/80+ cells from the spleens of SCID mice. It has been shown that freshly isolated, nonactivated human NK cells do not express CD40L (21); however, IL-2-activated human NK cells do express CD40L (6). In this study we found that addition of anti-CD40L Abs significantly (P < 0.001) reduced or completely blocked IFN-γ production by NK cells activated by IL-2-LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophages. In fact, our data show that addition of anti-CD40L Abs reduced IFN-γ to levels below that seen in control (dextran-stimulated) cultures, indicating that CD40-CD40L interaction between NK cells and macrophages was important for NK cell activation and subsequent IFN-γ production. This appears to be the first report of such a macrophage CD40-, NK cell CD40L-dependent activation of IFN-γ secretion. Our finding fits well with a recent report showing that the CD40-dependent cytotoxic pathway is functional on human NK lines, clones, and IL-2-activated NK cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (6). Further, CD40L-mediated signaling was shown to promote the in vitro activation of cytotoxic as well as NF-κB binding activity in NK cells from tumor-transplanted animals, and in addition, NK cell CD154 interaction with macrophage CD40 was shown to be important in macrophage activation and phagocytosis in an in vitro sepsis model (20, 34). Taking these data together with our data, it appears that CD40-CD40L interaction between NK cells and activated macrophages is important in mediating efficient cross talk between these two cell types.

In conclusion, we cannot rule out untested receptor-ligand pairs or numerous surface receptors and soluble factors that may also play various roles in LNFPIII-dex-stimulated macrophage-dependent activation of NK cells, as well as in cross talk between these two cell populations. Among those examined in our study, we were able to show that TNF-α does not play a determinant role in NK cell activation and IFN-γ production. Whatever roles untested soluble mediators may play in this process (possibly IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, or IFN-α/β) (8, 33, 35), our data do clearly support an alternative IL-12-independent model of NK cell activation requiring cell-contact as well as interaction between macrophage CD40 and NK cell CD40L. Thus, the cytokine mechanism presented here would be secondary to the contact-dependent activation of NK cells by LNFPIII-activated macrophages. In addition to CD40-CD40L, different NK cell receptors may be involved, and this may also depend on the activation/maturation stages of NK cells. The possible role of CD44 and Ly49D NK receptor signaling for IFN-γ production is under investigation (22, 27, 28, 32). Activator signals from macrophages to NK cells might be delivered via C-type lectin family receptor NKG2D or CD94/NKG2C (30, 35) or other receptors such as 2B4 or CD27 (24, 30).

Acknowledgments

We thank Akram Da'dara for critically reading the manuscript and Toby Daly-Engel for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R01AI056484).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amakata, Y., Y. Fujiyama, A. Andoh, K. Hodohara, and T. Bamba. 2001. Mechanism of NK cell activation induced by coculture with dendritic cells derived from peripheral blood monocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 124:214-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, D. M., C. E. Andoniou, A. A. Scalzo, S. L. van Dommelen, M. E. Wallace, M. J. Smyth, and M. A. Degli-Esposti. 2005. Cross-talk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells in viral infection. Mol. Immunol. 42:547-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atochina, O., T. Daly-Engel, D. Piskorska, E. McGuire, and D. A. Harn. 2001. A schistosome-expressed immunomodulatory glycoconjugate expands peritoneal Gr1(+) macrophages that suppress naive CD4(+) T cell proliferation via an IFN-gamma and nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 167:4293-4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beg, A. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science 274:782-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanca, I. R., E. W. Bere, H. A. Young, and J. R. Ortaldo. 2001. Human B cell activation by autologous NK cells is regulated by CD40-CD40 ligand interaction: role of memory B cells and CD5+ B cells. J. Immunol. 167:6132-6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbone, E., G. Ruggiero, G. Terrazzano, C. Palomba, C. Manzo, S. Fontana, H. Spits, K. Karre, and S. Zappacosta. 1997. A new mechanism of NK cell cytotoxicity activation: the CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. J. Exp. Med. 185:2053-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalbeth, N., R. Gundle, R. J. Davies, Y. C. Lee, A. J. McMichael, and M. F. Callan. 2004. CD56bright NK cells are enriched at inflammatory sites and can engage with monocytes in a reciprocal program of activation. J. Immunol. 173:6418-6426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demarco, R. A., M. P. Fink, and M. T. Lotze. 2005. Monocytes promote natural killer cell interferon gamma production in response to the endogenous danger signal HMGB1. Mol. Immunol. 42:433-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derby, E. G., V. Reddy, E. L. Nelson, W. C. Kopp, M. W. Baseler, J. R. Dawson, and A. M. Malyguine. 2001. Correlation of human CD56+ cell cytotoxicity and IFN-gamma production. Cytokine 13:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferlazzo, G., M. L. Tsang, L. Moretta, G. Melioli, R. M. Steinman, and C. Munz. 2002. Human dendritic cells activate resting natural killer (NK) cells and are recognized via the NKp30 receptor by activated NK cells. J. Exp. Med. 195:343-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez, N. C., A. Lozier, C. Flament, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, D. Bellet, M. Suter, M. Perricaudet, T. Tursz, E. Maraskovsky, and L. Zitvogel. 1999. Dendritic cells directly trigger NK cell functions: cross-talk relevant in innate anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Nat. Med. 5:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao, N., T. Dang, and D. Yuan. 2001. IFN-gamma-dependent and -independent initiation of switch recombination by NK cells. J. Immunol. 167:2011-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerosa, F., B. Baldani-Guerra, C. Nisii, V. Marchesini, G. Carra, and G. Trinchieri. 2002. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 195:327-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerosa, F., A. Gobbi, P. Zorzi, S. Burg, F. Briere, G. Carra, and G. Trinchieri. 2005. The reciprocal interaction of NK cells with plasmacytoid or myeloid dendritic cells profoundly affects innate resistance functions. J. Immunol. 174:727-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodier, M. R., and M. Londei. 2004. CD28 is not directly involved in the response of human CD3− CD56+ natural killer cells to lipopolysaccharide: a role for T cells. Immunology 111:384-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayakawa, Y., K. Takeda, H. Yagita, L. Van Kaer, I. Saiki, and K. Okumura. 2001. Differential regulation of Th1 and Th2 functions of NKT cells by CD28 and CD40 costimulatory pathways. J. Immunol. 166:6012-6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter, C. A., L. Ellis-Neyer, K. E. Gabriel, M. K. Kennedy, K. H. Grabstein, P. S. Linsley, and J. S. Remington. 1997. The role of the CD28/B7 interaction in the regulation of NK cell responses during infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 158:2285-2293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jewett, A., and B. Bonavida. 1993. Pivotal role of endogenous TNF-alpha in the IL-2-driven activation and proliferation of the functionally immature NK free subset. Cell Immunol. 151:257-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewett, A., M. Cavalcanti, and B. Bonavida. 1997. Pivotal role of endogenous TNF-alpha in the induction of functional inactivation and apoptosis in NK cells. J. Immunol. 159:4815-4822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jyothi, M. D., and A. Khar. 2000. Regulation of CD40L expression on natural killer cells by interleukin-12 and interferon gamma: its role in the elicitation of an effective antitumor immune response. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 49:563-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashii, Y., R. Giorda, R. B. Herberman, T. L. Whiteside, and N. L. Vujanovic. 1999. Constitutive expression and role of the TNF family ligands in apoptotic killing of tumor cells by human NK cells. J. Immunol. 163:5358-5366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieberman, L. A., and C. A. Hunter. 2002. Regulatory pathways involved in the infection-induced production of IFN-gamma by NK cells. Microbes Infect. 4:1531-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malyguine, A. M., J. E. Scott, and J. R. Dawson. 1998. The role of calnexin in NK-target cell interaction. Immunol. Lett. 61:67-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNerney, M. E., K. M. Lee, and V. Kumar. 2005. 2B4 (CD244) is a non-MHC binding receptor with multiple functions on natural killer cells and CD8(+) T cells. Mol. Immunol. 42:489-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moretta, A. 2002. Natural killer cells and dendritic cells: rendezvous in abused tissues. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:957-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okano, M., A. R. Satoskar, K. Nishizaki, M. Abe, and D. A. Harn, Jr. 1999. Induction of Th2 responses and IgE is largely due to carbohydrates functioning as adjuvants on Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens. J. Immunol. 163:6712-6717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortaldo, J. R., E. W. Bere, D. Hodge, and H. A. Young. 2001. Activating Ly-49 NK receptors: central role in cytokine and chemokine production. J. Immunol. 166:4994-4999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortaldo, J. R., and H. A. Young. 2003. Expression of IFN-gamma upon triggering of activating Ly49D NK receptors in vitro and in vivo: costimulation with IL-12 or IL-18 overrides inhibitory receptors. J. Immunol. 170:1763-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccioli, D., S. Sbrana, E. Melandri, and N. M. Valiante. 2002. Contact-dependent stimulation and inhibition of dendritic cells by natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 195:335-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raulet, D. H. 2004. Interplay of natural killer cells and their receptors with the adaptive immune response. Nat. Immunol. 5:996-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross, M. E., and M. A. Caligiuri. 1997. Cytokine-induced apoptosis of human natural killer cells identifies a novel mechanism to regulate the innate immune response. Blood 89:910-918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sague, S. L., C. Tato, E. Pure, and C. A. Hunter. 2004. The regulation and activation of CD44 by natural killer (NK) cells and its role in the production of IFN-gamma. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 24:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt, K. N., B. Leung, M. Kwong, K. A. Zarember, S. Satyal, T. A. Navas, F. Wang, and P. J. Godowski. 2004. APC-independent activation of NK cells by the Toll-like receptor 3 agonist double-stranded RNA. J. Immunol. 172:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott, M. J., J. J. Hoth, M. K. Stagner, S. A. Gardner, J. C. Peyton, and W. G. Cheadle. 2004. CD40-CD154 interactions between macrophages and natural killer cells during sepsis are critical for macrophage activation and are not interferon gamma dependent. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 137:469-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siren, J., T. Sareneva, J. Pirhonen, M. Strengell, V. Veckman, I. Julkunen, and S. Matikainen. 2004. Cytokine and contact-dependent activation of natural killer cells by influenza A or Sendai virus-infected macrophages. J. Gen. Virol. 85:2357-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith, P., C. M. Walsh, N. E. Mangan, R. E. Fallon, J. R. Sayers, A. N. McKenzie, and P. G. Fallon. 2004. Schistosoma mansoni worms induce anergy of T cells via selective up-regulation of programmed death ligand 1 on macrophages. J. Immunol. 173:1240-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stout, R. D., and J. Suttles. 1996. The many roles of CD40 in cell-mediated inflammatory responses. Immunol. Today 17:487-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stout, R. D., J. Suttles, J. Xu, I. S. Grewal, and R. A. Flavell. 1996. Impaired T cell-mediated macrophage activation in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 156:8-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tato, C. M., G. A. Martins, F. A. High, C. B. DiCioccio, S. L. Reiner, and C. A. Hunter. 2004. Cutting edge: innate production of IFN-gamma by NK cells is independent of epigenetic modification of the IFN-gamma promoter. J. Immunol. 173:1514-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terrazas, L. I., K. L. Walsh, D. Piskorska, E. McGuire, and D. A. Harn, Jr. 2001. The schistosome oligosaccharide lacto-N-neotetraose expands Gr1(+) cells that secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibit proliferation of naive CD4(+) cells: a potential mechanism for immune polarization in helminth infections. J. Immunol. 167:5294-5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thierfelder, W. E., J. M. van Deursen, K. Yamamoto, R. A. Tripp, S. R. Sarawar, R. T. Carson, M. Y. Sangster, D. A. Vignali, P. C. Doherty, G. C. Grosveld, and J. N. Ihle. 1996. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature 382:171-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas, P. G., M. R. Carter, O. Atochina, A. A. Da'Dara, D. Piskorska, E. McGuire, and D. A. Harn. 2003. Maturation of dendritic cell 2 phenotype by a helminth glycan uses a Toll-like receptor 4-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 171:5837-5841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinchieri, G. 1989. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv. Immunol. 47:187-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trinchieri, G. 1998. Immunobiology of interleukin-12. Immunol. Res. 17:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trinchieri, G. 1995. Natural killer cells wear different hats: effector cells of innate resistance and regulatory cells of adaptive immunity and of hematopoiesis. Semin. Immunol. 7:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tripp, C. S., S. F. Wolf, and E. R. Unanue. 1993. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha are costimulators of interferon gamma production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3725-3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner, J. G., A. L. Rakhmilevich, L. Burdelya, Z. Neal, M. Imboden, P. M. Sondel, and H. Yu. 2001. Anti-CD40 antibody induces antitumor and antimetastatic effects: the role of NK cells. J. Immunol. 166:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Antwerp, D. J., S. J. Martin, T. Kafri, D. R. Green, and I. M. Verma. 1996. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science 274:787-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villegas, E. N., L. A. Lieberman, N. Mason, S. L. Blass, V. P. Zediak, R. Peach, T. Horan, S. Yoshinaga, and C. A. Hunter. 2002. A role for inducible costimulator protein in the CD28-independent mechanism of resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 169:937-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, C. Y., M. W. Mayo, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1996. TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science 274:784-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warschkau, H., and A. F. Kiderlen. 1999. A monoclonal antibody directed against the murine macrophage surface molecule F4/80 modulates natural immune response to Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 163:3409-3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warschkau, H., H. Yu, and A. F. Kiderlen. 1998. Activation and suppression of natural cellular immune functions by Pneumocystis carinii. Immunobiology 198:343-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wille, U., E. N. Villegas, L. Craig, R. Peach, and C. A. Hunter. 2002. Contribution of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and the CD28/B7 and CD40/CD40 ligand pathways to the development of a pathological T-cell response in IL-10-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 70:6940-6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]