Abstract

Antibody-secreting cell (ASC) and antibodies in lymphocyte supernatant (ALS) assays are used to assess intestinal mucosal responses to enteric infections and vaccines. The ALS assay, performed on cell supernatants, may represent a convenient alternative to the more established ASC assay. The two methods, measuring immunoglobulin A to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi lipopolysaccharide, were compared in volunteers vaccinated with a live-attenuated typhoid vaccine M01ZH09. The specificity of the ALS assay compared to the ASC assay was excellent (100%), as was sensitivity (82%). The ALS assay was less sensitive than the ASC assay at ≤42 spots/106 peripheral blood lymphocytes.

After vaccination or infection, antigen-specific antibody (immunoglobulin [Ig])-secreting cells briefly circulate systemically before homing to mucosal effector sites, such as the intestine (7, 8, 12). Both the solid-phase antibody-secreting cell (ASC; or enzyme-linked immunospot [ELISPOT]) assay and the human lymphocyte supernatant (antibodies in lymphocyte supernatant [ALS]) assay are used semiquantitatively to assay mucosal immune responses (2-4, 6, 7, 11). The ASC assay enumerates “spots” formed by Ig-producing cells bound to a nitrocellulose plate after incubation of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) with specific antigen, whereas the ALS assay measures, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, antibody in the supernatant of incubated PBL (2, 6, 7). The ALS assay has greater flexibility than the ASC assay, since antibody measurements can be performed later on frozen lymphocyte supernatants (2-4, 11). Comparison of the ALS and ASC assays has been extensively reviewed for tuberculosis and cholera, but the assays have not been compared for a systemic enteric illness such as a typhoid vaccine model (11, 13, 14). We compared the sensitivity and specificity of ALS and ASC assays in 31 adult volunteers vaccinated with a candidate oral typhoid vaccine, M01ZH09 (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi [Ty2 S. Typhi ssaV−aroC−]) (5, 9, 10).

An open-label, randomized trial was performed at the University of Vermont, approved by the institutional review board, and carried out under a Food and Drug Administration investigational new drug application. Thirty-one healthy adult volunteers aged 18 to 50 years old with no history of typhoid vaccination received 5 × 109 CFU of M01ZH09 after fasting for ≥2 h, as described previously (10). Whole blood for PBL was collected in heparinized cell preparation tubes (Vacutainer CPT; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) on the day of vaccination (day 0) and day 7 postvaccination.

ASC assay.

The IgA ASC assay to S. enterica serovar Typhi lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was performed as described previously (1, 6, 7). PBL were plated at 2.5 × 106/ml, 5.0 × 106/ml, and 1 × 107/ml on nitrocellulose microtiter plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Wells were coated with S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 1× Reggiardo's buffer or were uncoated. PBL from volunteers, positive and negative controls, were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween, an anti-human IgA-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was added and the mixture was incubated for 1 h. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium substrate was added to each well for 30 min in the dark, and the reaction was stopped by washing the microtiter plates. ASC “spots” were manually counted by two observers, photographed, and expressed as antibody-secreting cells/106 PBL. A result of ≥4 ASC per 106 PBL was defined as a positive response. Previous testing in clinical trials has validated the use of this positive cutoff as over >3 standard deviations from the mean of negative control ASC counts (0 to 2/106) (10).

ALS assay.

PBL were diluted to 1 × 107 cells/ml in plating medium (RPMI, 10% fetal calf serum, and 1% pencillin-streptomycin). An aliquot of the diluted PBL was centrifuged, and supernatant was frozen at −20°C as the “time zero” sample. The remainder of the PBL were plated on a 96-well plate at 1 × 106 cells/ml and 1 × 107 cells/ml, with 6 wells/volunteer/concentration and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24, 72, or 96 h. At each time point, cell supernatants were frozen as described above (2, 11).

To determine supernatant levels of S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS-specific IgA, 96-well microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS (0.5 μg/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in Reggiardo's buffer. Plates were washed and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 2 h at 37°C. A standard curve, linear at 5 to 70 U/ml, of S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS IgA-positive sera in plating medium was used. IgA-negative serum was used as a negative control, and IgA in the standard serum was set arbitrarily at 40,000 U/ml. Three sets of quality control (QC) samples were used (high QC, 48 U/ml; mid QC, 27 U/ml; and low QC, 12 U/ml) throughout the plate. Frozen cell supernatants were added in duplicate, after thawing at room temperature and dilution to 1:10, 1:50, and 1:100 in plating medium. Samples under 5 U/ml and all day 0 samples were rediluted at 1:5. No sample needed dilution to >1:100. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, 1° antibody (goat anti-human IgA-biotin conjugate at 1:2,000) and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase were added sequentially, each followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C and washing. Tetramethyl benzidine substrate was added in the dark, the mixture was incubated at room temperature, and then the reaction was stopped with H2SO4. Plates were read on a Biotek enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Colchester, VT) at 450 nm.

The optical density of standards, minus blanks, was plotted against concentration and described by a four-parameter logistic fit. Optical density was interpreted against the standard curve, and concentrations of anti-LPS IgA were determined. All plates met acceptance criteria (R2 of the standard curve fit > 0. 950; accuracy for the QC control samples within 25.0% of the expected concentration; and replicate coefficients of variation (based on absorbance) of <15.0%.

Both the ASC and ALS assays demonstrated responses that were 100% specific to vaccine exposure. All day 0 ASC assays were negative for spot-forming cells. Day 7 ASC assays demonstrated a range of ASC (Table 1). Three of 31 (9.7%) plates demonstrated 0 to 3 spots and were considered “negative.” Twenty-eight of 31 (90.3%) plates were “positive” for ≥4 ASC. Positive plate spot counts ranged from 5 to 1,040/106 PBL.

TABLE 1.

Antigen-specific mucosal antibody responses in subjects vaccinated with M01ZH09 by ASC and ALS assaysa

| Subject | No. of spots/106 cells by assay:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASC

|

ALS

|

||||||

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 0 (all times)b | Day 7

|

||||

| 0 h | 24 h | 72 h | 96 h | ||||

| 003 | 0 | 1,040 | 0 | 0 | 116 | 267 | 154 |

| 004 | 0 | 624 | 0 | 0 | 453 | 426 | 397 |

| 006 | 0 | 560 | 0 | 0 | 1,145 | 2,145 | 3,200 |

| 005 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 0 | 255 | 481 | 486 |

| 028 | 0 | 396 | 0 | 0 | 235 | 497 | 347 |

| 022 | 0 | 362 | 0 | 0 | 369 | 616 | 351 |

| 001 | 0 | 209 | 0 | 0 | 105 | 244 | 225 |

| 015 | 0 | 199 | 0 | 0 | 494 | 893 | 1,101 |

| 021 | 0 | 198 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 156 | 63 |

| 008 | 0 | 172 | 0 | 0 | 199 | 391 | 636 |

| 019 | 0 | 172 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 133 | 68 |

| 025 | 0 | 154 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 173 | 100 |

| 007 | 0 | 149 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 71 | 102 |

| 017 | 0 | 148 | 0 | 0 | 237 | 289 | 283 |

| 009 | 0 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 130 | 186 | 323 |

| 014 | 0 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 132 | 101 |

| 024 | 0 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 77 | 123 |

| 020 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 7 |

| 002 | 0 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 68 | NDc |

| 011 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| 031 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 70 | 0 |

| 018 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 029 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| 027 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 22 | 32 |

| 023 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 030 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 012 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 026 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 032 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 016 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Results represent responses in 31 adult subjects vaccinated with M01ZH09 as measured by ASC and ALS assays performed at days 0 and 7 postvaccination. Note that plates for three subjects (032, 016, and 013) demonstrated 0 to 3 spots and were considered “negative.”

All incubation times for day 0 (0, 24, 72, and 96 h).

ND, not determined.

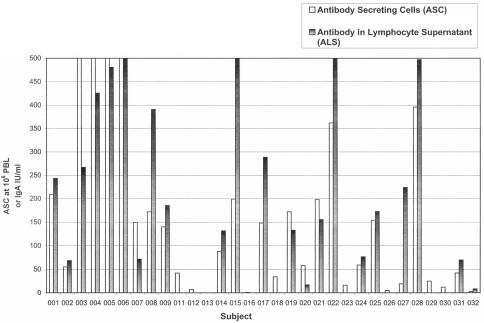

Similarly, all day 0 ALS assays were negative at all time points of incubation (0, 24, 72, and 96 h). At 72 and 96 h, ALS responses peaked in most subjects. In most samples, positive ALS assay IgA results trended closely to the ASC result (Fig. 1). Divergence occurred in two samples with very-high-positive ASC plates (no. 03 and 06). The ALS assay data demonstrated concordance to ASC results in 26 of 31 (84%) of the volunteers (Table 1) and a sensitivity of 82% (23/28). Five subjects who demonstrated an ASC response of 7 to 34 spots/106 cells had no response by ALS, even upon triplicate testing of both cell concentrations used in the ALS assay (106 and 107/ml) and using decreasing dilutions. However, concordance was exact when ASC counts were >42 spots/106 PBL. All positive ALS assays demonstrated a positive ASC result (100% positive predictive value of ASC response).

FIG. 1.

The S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS IgA ASC and ALS assays demonstrate concordance in volunteers vaccinated with oral typhoid vaccine M01ZH09.

The ASC assay is used in early-phase vaccine trials as a measure of oral and enteric vaccine intestinal immunogenicity (1, 6, 7). ASC, a solid-phase assay usually performed on fresh PBL, measures the ability of vaccination to induce antigen-specific IgA antibody-secreting cells, which contribute to specific mucosal immunity. The IgA, secreted into supernatant, is measured by ALS (2-4, 11, 13, 14). ALS offers the convenience of freezing and “banking” lymphocyte supernatant for later measurement of antibody or cytokine levels (2-4). In S. enterica serovar Typhi, a positive ASC response has been associated with vaccine efficacy in field trials (6). ALS has not independently been correlated with efficacy but has been demonstrated to be more sensitive than specific serum or intestinal IgA (3, 4).

Our data demonstrate that the ALS and ASC results show an excellent concordance. Both assays are highly specific to vaccine exposure (100%), as demonstrated by the negative results prevaccination and also by examining the ALS supernatant preincubation, 7 days postvaccination (day 7, time zero). When compared to the ASC assay, the ALS assay is also 100% specific. The concordance and sensitivity of ALS versus ASC assay are also high (84% and 82%, respectively), as is the positive predictive value (100%). Interestingly, the ALS assay was negative for several (n = 5) samples that demonstrated a modest to moderate ASC response (4 to 34/106 PBL), but matched ASC results for ≥42 spots/106 cells. Although the ALS assay appears less sensitive than the ASC assay for IgA to S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS, the >42 spots/106 cells may correlate with clinical efficacy. In addition, the ALS and ASC assays appear to diverge at very high counts (>400). However, when ASC counts are extremely high, ASC counts may be imprecise, since extensive sample dilution may not be possible with limited PBL.

Our data suggest that the ASC and ALS assays demonstrate excellent specificity and sensitivity in an oral typhoid vaccine model, particularly at ASC counts of ≥42 spots/106 cells. Future work will determine whether similar ASC levels correlate with vaccine efficacy or immunogenicity. The ALS assay is a flexible and robust alternative to the ASC assay and may be easier to validate as a model of vaccine immunogenicity used to support vaccine licensure.

Acknowledgments

Clinical trial funding was provided by Microscience Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baqar, S., A. A. M. Nour El Din, D. A. Scott et al. 1997. Standardization of measurement of immunoglobulin-secreting cells in human peripheral circulation. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:375-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, H. S., and D.A. Sack. 2001. Development of a novel in vitro assay (ALS assay) for evaluation of vaccine-induced antibody secretion from circulating mucosal lymphocytes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:482-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrest, B. D. 1988. Identification of an intestinal immune response using peripheral blood lymphocytes. Lancet i:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest, B. D. 1992. Indirect measurement of intestinal immune responses to an orally administered attenuated bacterial vaccine. Infect. Immun. 60:2023-2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindle, Z., S. N. Chatfield, J. Phillimore, M. Bentley, J. Johnson, C. A. Cosgrove et al. 2002. Characterization of Salmonella enterica derivatives harboring defined aroC and Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system (ssaV) mutations by immunization of healthy volunteers. Infect. Immun. 70:3457-3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantele, A. 1990. Antibody-secreting cells in the evaluation of the immunogenicity of an oral vaccine. Vaccine 8:321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantele, A., H. Arvilommi, and I. Jokinen. 1986. Specific immunoglobulin-secreting human blood cells after peroral vaccination with Salmonella typhi. J. Infect. Dis. 153:1126-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantele, A., et al. 1997. Homing potentials of circulating lymphocytes in humans depends on the site of activation. J. Immunol. 158:574-579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan, S. A., R. Stratford, T. Wu, N. McKelvie, T. Bellaby, Z. Hindle et al. 2003. Salmonella typhi and S. typhimurium derivatives harbouring deletions in aromatic biosynthesis and Salmonella pathogenicity island-2 (SPI-2) genes as vaccines and vectors. Vaccine 21:538-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick, B. D., K. M. Tenney, C. J. Larsson, J. P. O'Neill, C. Ventrone, M. Bentley, et al. 2005. The novel oral typhoid vaccine M01ZH09 is well-tolerated and highly immunogenic in two vaccine presentations. J. Infect. Dis. 192:360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qadri, F., E. T. Ryan, A. S. G. Faruque, F. Ahmed, A. I. Khan, M. M. Islam, S. M. Akramuzzaman, D. A. Sack, and S. B. Calderwood. 2003. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin A antibodies secreted from circulating B cells are an effective marker for recent local immune responses in patients with cholera: comparison to antibody-secreting cell responses and other immunological markers. Infect. Immun. 71:4808-4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quiding-Jarbrink, M. 1997. Differential expression of tissue-specific adhesion molecules on human circulating antibody-forming cells after systemic, enteric and nasal immunizations. J. Clin. Investig. 99:1281-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raqib, R., S. M. Mostafa Kamal, M. J. Rahman, Z. Rahim, S. Banu, P. K. Bardhan et al. 2004. Use of antibodies in lymphocyte secretions for detection of subclinical tuberculosis infection in asymptomatic contacts. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 11:1022-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raqib, R., J. Rahman, A. K. M. Kamaluddin, S. M. Mostafa Kamal, F. A. Banu, S. Ahmed et al. 2003. Rapid diagnosis of active tuberculosis by detecting antibodies from lymphocyte secretions. J. Infect. Dis. 188:364-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]