Abstract

Outbreaks of poliomyelitis caused by circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) have been reported in areas where indigenous wild polioviruses (PVs) were eliminated by vaccination. Most of these cVDPVs contained unidentified sequences in the nonstructural protein coding region which were considered to be derived from human enterovirus species C (HEV-C) by recombination. In this study, we report isolation of a Sabin 3-derived PV recombinant (Cambodia-02) from an acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) case in Cambodia in 2002. We attempted to identify the putative recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02 by sequence analysis of nonpolio enterovirus isolates from AFP cases in Cambodia from 1999 to 2003. Based on the previously estimated evolution rates of PVs, the recombination event resulting in Cambodia-02 was estimated to have occurred within 6 months after the administration of oral PV vaccine (99.3% nucleotide identity in VP1 region). The 2BC and the 3Dpol coding regions of Cambodia-02 were grouped into the genetic cluster of indigenous coxsackie A virus type 17 (CAV17) (the highest [87.1%] nucleotide identity) and the cluster of indigenous CAV13-CAV18 (the highest [94.9%] nucleotide identity) by the phylogenic analysis of the HEV-C isolates in 2002, respectively. CAV13-CAV18 and CAV17 were the dominant HEV-C serotypes in 2002 but not in 2001 and in 2003. We found a putative recombination between CAV13-CAV18 and CAV17 in the 3CDpro coding region of a CAV17 isolate. These results suggested that a part of the 3Dpol coding region of PV3(Cambodia-02) was derived from a HEV-C strain genetically related to indigenous CAV13-CAV18 strains in 2002 in Cambodia.

Poliovirus (PV) is a small nonenveloped virus with a single-strand positive genomic RNA of about 7,500 nucleotides (nt) belonging to the family Picornaviridae, known as the causative agent of poliomyelitis. Currently, the global eradication program for poliomyelitis is continuing by utilizing both inactivated and live attenuated vaccines (44, 46). The endemicity of indigenous wild PVs was confirmed to be restricted to Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Niger, Nigeria, and Pakistan as of 2004 (http://www.polioeradication.org/progress.asp).

The Sabin strains (Sabin 1, 2, and 3) are attenuated PV strains and have been widely used as live oral PV vaccine (OPV) (44). Following the administration of OPV, the viruses infect the mucosal tissues and are commonly excreted for 3 to 7 weeks from immunocompetent individuals (1, 18) and occasionally for 10 to 22 years from immunodeficient patients (2, 25, 32; reviewed in reference 48). During the replication of the Sabin strains, revertants with increased virulence could emerge and cause vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis in rare cases. The rate of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis has been estimated as one case per 520,000 doses associated with the first dose of OPV (35). The revertants have been isolated from healthy individuals and also from the environment (21, 52).

Recently, outbreaks of poliomyelitis caused by circulating vaccine-derived PV (cVDPV) have been reported in Egypt, Hispaniola, the Philippines, and Madagascar (6, 8, 10, 24, 51). Sequence analysis of the genomes of cVDPVs showed unidentified sequences in the nonstructural protein coding region. These sequences are considered to be derived from recombination with unidentified nonpolio enterovirus (NPEV) during the circulation of VDPVs for 1 to 10 years (6, 8, 10, 24, 49, 51). However, a highly evolved derivative of Sabin strains without recombination by an unidentified counterpart has been isolated from an acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) case after a long-term circulation (12). Therefore, the biological role of the recombination of cVDPVs with unidentified counterpart remains to be elucidated. At present, increased transmissibility of cVDPVs compared with that of the parental Sabin strains has been proposed as a result of the recombination (3, 16); however, no virological evidence has been provided so far.

Indigenous wild PVs have been eliminated in regions where cVDPVs have been reported (1991 in the Americas [42], 1993 in the Philippines [11], and 1998 in Madagascar [41]) except Egypt. Therefore, the field NPEVs genetically closely related to PV or highly mutated Sabin derivatives are considered the possible counterparts of the recombination. Among NPEVs, coxsackie A viruses (CAVs) belonging to human enterovirus species C (HEV-C) are the suspected origin of the recombination because of the higher similarity of the genomic sequence with that of PV compared with those of other NPEVs belonging to HEV-A, HEV-B, or HEV-D (4, 22). A recent report indicated that HEV-C was frequently isolated in Madagascar (around 50% of NEPV isolates), suggesting the possible involvement of HEV-C in the emergence of the recombinant cVDPVs (41).

Here, we report an isolation and genetic characterization of a Sabin 3-derived PV recombinant (Cambodia-02) from an AFP case in Cambodia in 2002. Based on the previously estimated evolution rates of PVs, it was estimated that Cambodia-02 was isolated within 6 months after the administration of OPV, suggesting that the recombination occurred within 6 months before the isolation. This prompted us to identify the recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02 among the HEV-C isolates in Cambodia. We performed phylogenic analysis and identification of NPEV isolates from AFP cases in Cambodia from 1999 to 2003.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

RD cells (derived from human rhabdomyosarcoma), HEp-2c cells (derived from human larynx epidermoid carcinoma) and L20B cells (derived from mouse L tk− aprt− fibroblast) were cultured as monolayers in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (33, 50). RD, HEp-2c, and L20B cells were used for the virus isolation from fecal samples of AFP cases. Virus stocks were stored at −70°C.

Sequence analysis of the genomes of enterovirus isolates.

Viral genomic RNA was isolated from the culture fluid of infected cells by using a High Pure viral RNA purification kit (Roche). DNA fragments used for the DNA sequencing were prepared by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using the viral genomic RNA as the template by use of a Titan one-tube RT-PCR system (Roche). PCR products were purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). DNA sequencing was performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.0 cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems), and then sequences were analyzed by use of an ABI PRIZM 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the 5′ end of the viral genomes were determined by the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends method by using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends system, version 2.0 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequence of the 3′ end of the viral genomes was determined from an RT-PCR product obtained with UG16 primer (20) and EcoRI-3END− (Table 1). The percentage of the mutated synonymous sites among all synonymous sites (Ks) was calculated for the VP1 coding region as previously reported (2, 12, 17). Phylogenic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method after bootstrapping 1,000 times (14, 45) using PHYLIP software (Joseph Felsenstein 1990, University of Washington). The nucleotide substitutions among the isolates were estimated by the Kimura-2 parameter method (26). The rate of transition-transversion was set at 2.0. Similarity plot analysis of HEV-C isolates was performed by using SimPlot (29).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for sequence analysis of enterovirus isolates

| Primer | Sequencea | Corresponding site on Sabin 3 genome (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| UG16 | GTTGGTGGGAACGGTTCACA | 5912-5931 |

| EcoRI-3END− | ACTGGAATTCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTV | 7432-poly(A) tail |

| UC12 | TCAATTAGTCTGGATTTTCCCTG | 6485-6507 |

| EVP4 | CTACTTTGGGTGTCCGTGTT | 544-563 |

| OL68-1 | GGTAAYTTCCACCACCANCC | 1178-1197 |

| 2A2+ | TTTKCNGMACCWGGKGAYTGYGGYGG | 3683-3708 |

| 2C− | GGYTCAATACGGYRTTTGCTCTTGAACTG | 4451-4479 |

| 292 | MIGCIGYIGARACNGG | 2604-2619 |

| 222 | CICCIGGIGGIAYRWACAT | 2942-2960 |

Variable sequence positions in the primers are expressed according to the IUPAC system. Sequences read from the 5′ position at the left end.

Primers used for the sequence analysis are listed on Table 1. Primers UG16 and UC12 were used for the analysis of a part of the 3Dpol coding region (20). Primers EVP4 and OL68-1 were used for the analysis of the VP4 coding region (39, 43). Primers 2A2+ and 2C− were designed and used for the analysis of a part of the 2BC coding region. Primers 292 and 222 were used for the initial analysis of the VP1 coding region (37). Genomic sequences used for the phylogenic analysis were as follows: 207 nt of the VP4 coding region (corresponding to nt 743 to 949 of the Sabin 3 genome), 337 nt of the 2BC coding region (corresponding to nt 3854 to 4190 of the Sabin 3 genome), and 352 nt of the 3Dpol coding region (corresponding to nt 6137 to 6488 of the Sabin 3 genome).

Identification of NPEV isolates.

A panel of horse antisera against commonly found NPEVs (RIVM, Bilthoven, The Netherlands), which include echo and coxsackie B viruses, was used for the identification of HEV-B. Antisera against CAVs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. A total of 100 50% cell culture infectious doses of enterovirus isolates were incubated with 20 units of antiserum for 2 h in 37°C, and then HEp-2c cell or RD cell suspensions in 10% fetal calf serum-minimum essential medium were added and incubated at 35.5°C (50). Inoculated cells were observed for cytopathic effect until 24 h after the complete appearance of cytopathic effect in the cells inoculated with the isolates in the absence of antiserum.

Accession numbers of the nucleotide sequences.

All the nucleotide sequences determined in this study were submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ). The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers of each sequence were as follows. The accession numbers of the VP4 coding region, the 2BC coding region, and the 3Dpol coding region of the NPEV isolates are AB206334 to AB206380, AB206709 to AB206757, and AB205529 to AB205546, respectively (see Fig. 2, 3, and 5 and the supplemental material). The accession numbers of the VP1 coding region of CAM1952, CAM2033, CAM2038, and CAM2083 are AB207264, AB207263, AB207265, and AB207266, respectively (Table 1). The accession numbers of the genomic sequences of Cambodia-02, CAM1900, CAM1972, CAM2069, and CAM2101 are AB205395, AB205397, AB205396, AB205398, and AB205399, respectively.

FIG. 2.

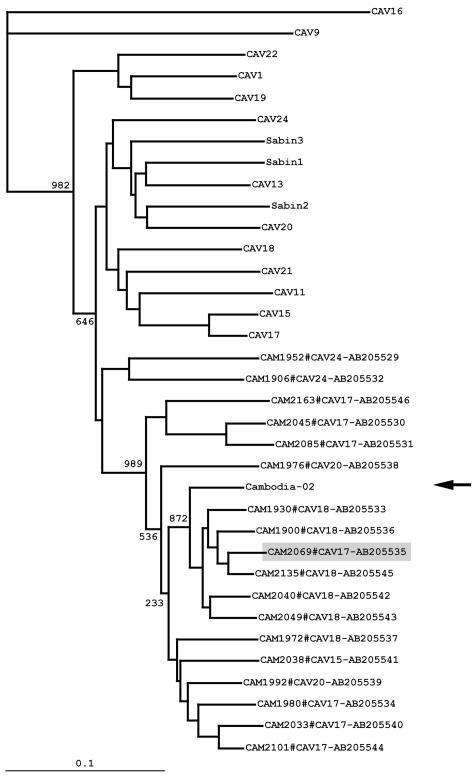

Phylogenic analysis of the 3Dpol coding region. The phylogenic tree was generated from the nucleotide sequences of the 3Dpol coding region of Cambodian HEV-C isolates, prototype HEV-C strains, and Sabin strains. The location of Cambodia-02 is indicated by an arrow. A putative HEV-C recombinant (CAM2069) is colored with light gray. The nomenclature of the isolates indicates the names of the isolates, serotypes, and the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers. Bootstrap values are shown at the branch nodes. Bar, 0.1 substitution per site.

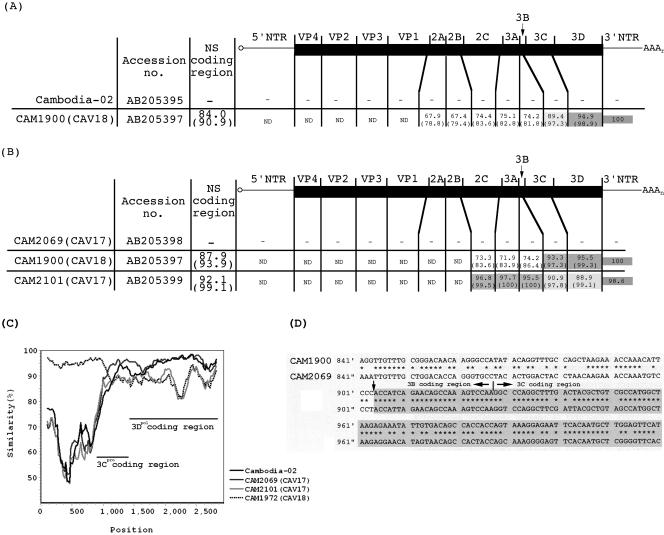

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the genomes of Cambodian HEV-C isolates. The numbers in each region represent the percentages of nucleotide identity, and the numbers in parentheses represent the percentages of amino acid identity. The genomic regions that showed more than 90% amino acid identity are colored with light gray, and the genomic regions that showed more than 92% nucleotide identity are colored with dark gray. (A) Alignment of Cambodia-02 with a CAV13-CAV18 isolate (CAM1900). (B) Alignment of a CAV17 isolate (CAM2069) with CAM1900 (CAV13-CAV18) and CAM2101 (CAV17). (C) Multisequence analysis of HEV-C isolates and Cambodia-02 by similarity plot analysis calculated by SimPlot. CAM1900 was used as the reference. A window size of 200 bp with an increment of 20 bp was used. The locations of 3Cpro and 3Dpol coding regions are shown in the plot. (D) Alignment of a part of the genome of CAM1900 with that of CAM2069 around the putative recombination junction near the 3Cpro coding region. The part representing unidentified sequence is colored with gray. NS; nonstructural protein, ND; not determined.

RESULTS

Isolation of a type 3 PV recombinant from an AFP case.

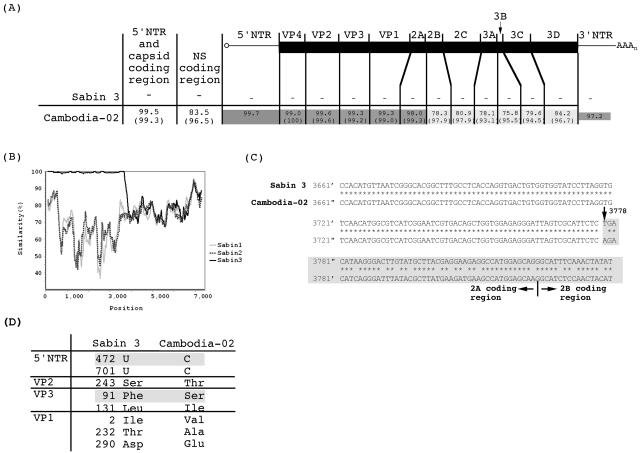

In 2002, type 3 PVs were isolated from three AFP cases in Cambodia. These PV isolates were initially characterized by sequencing of the VP1 coding region, and all the isolates were classified as OPV-like PVs according to the criteria of the World Health Organization (less than 1% nucleotide difference from the parental Sabin 3) (50). However, we found that one of these PV isolates (Cambodia-02) contained an unidentified sequence in the 3Dpol coding region which was apparently not related to those of the Sabin strains (Fig. 1). Further sequence analysis of the genome of Cambodia-02 showed that the 5′ part of the genome (from nt 1 to 3777), including the 5′ nontranslated region (5′NTR), the structural protein coding region, and a part of the 2Apro coding region, was derived from Sabin 3 followed by an unidentified sequence from the 2Apro coding region to the 3′ end of the genome (from nt 3778 to the 3′ end) (Fig. 1B and C). The nonstructural protein coding region of Cambodia-02 showed only low similarity with those of Sabin strains (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

The genomic sequence of Cambodia-02. (A) Alignment of the genome of Cambodia-02 (accession no. AB205395) with that of Sabin 3 (accession no. X00925). The numbers in each region represent the percentages of nucleotide identity with the Sabin 3 genome. The numbers in parentheses represent the percentages of amino acid identity. The genomic regions that showed more than 90% amino acid identity are colored with light gray, and genomic regions that showed more than 96% nucleotide identity are colored with dark gray. The nucleotide identity in the 5′ part of the genome (including the 5′NTR and the structural protein coding region) and in the nonstructural protein (NS) coding region are also shown. (B) Similarity plot analysis of Cambodia-02 and Sabin strains (Sabin 1, accession no. AY184219; Sabin 2, accession no. AY184220) calculated by SimPlot. The nucleotide sequence of the Cambodia-02 genome was used as the reference. A window size of 200 bp with an increment of 20 bp was used. (C) Alignment of the genome of Cambodia-02 with that of Sabin 3 near the putative recombination junction in the 2Apro coding region. The part representing unidentified sequence (from nt 3778 to the 3′ end) is colored with light gray. (D) The nucleotide and amino acid differences in the 5′NTR and the capsid proteins of Cambodia-02. Numbers represent the positions of nucleotides in the 5′NTR or of the amino acid residues in each capsid protein.

The nucleotide identity of the 5′ part of the Cambodia-02 genome to Sabin 3 was 99.5%. The Ks value of Cambodia-02 calculated for the VP1 coding region was 1.35 × 10−2 (with a standard error of 0.77 × 10−2). Using evolution rates of PV observed for immunodeficiency cases (2.85 × 10−2 to 3.28 × 10−2 synonymous substitutions per synonymous site per year) or for transmission of wild PV recombinants (3.45 × 10−2 synonymous substitutions per synonymous site per year) (2, 17, 28), we estimated that Cambodia-02 was isolated within 6 months after the administration of OPV. Cambodia-02 had reversions at the major attenuation determinants of Sabin 3 at nt 472 (U to C) and nt 2034, which resulted in an amino acid change of VP3 Phe91 to Ser (13, 31) (Fig. 1D). The Cambodia-02 genome contained multiple mutations in the structural protein coding region in addition to VP3 Phe91, as previously reported for temperature-resistant revertants of Sabin 3 (15, 31, 34).

Isolation and identification of HEV-C from AFP cases in Cambodia.

We analyzed the genome of NPEV isolates from AFP cases around 2002 in Cambodia to identify the putative recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02. In 2002, we isolated NPEVs from 53 AFP cases (one was from a mixed case with PV) among a total of 155 AFP cases (Table 2). For the initial molecular typing of the isolates, we analyzed the VP4 coding region (nt 743 to 949 of the Sabin 3 genome; 207 nt) to classify the isolates into each genomic species (HEV-A, HEV-B, and HEV-C) (23). We found that 21 isolates were grouped into HEV-C by the phylogenic tree analysis of the sequence of the VP4 coding region (data not shown). We identified the serotype of HEV-C isolates by a neutralization assay using type-specific antisera or by sequence analysis of the VP1 coding region. We could not discriminate CAV13 from CAV18 or CAV11 from CAV15 by the sequence analysis or by the neutralization assay, consistent with previous reports (4, 36). The deduced amino acid sequence of the VP1 protein of CAM2033 and CAM2038 showed a high nucleotide identity with those of CAV17 (94.1%) and CAV11-CAV15 (96.7%), respectively. We could not identify the serotype of CAM2083 from the deduced amino acid sequence of the VP1 protein, which showed low similarity with known enteroviruses. We observed the highest amino acid identity only with CAV24 (DN-19 strain) (74.1%) or with a CAV24 variant (73.1%). Consequently, HEV-C isolates in Cambodia in 2002 consisted of CAV1, CAV11-CAV15, CAV17, CAV13-CAV18, CAV20, CAV24, and an untypable HEV-C strain CAM2083 (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Virus isolation from AFP cases in Cambodia from 1999 to 2003

| Identification | No. of cases

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

| AFP | 149 | 230 | 168 | 155 | 128 |

| Virus isolated | 49 | 73 | 46 | 55 | 39 |

| Poliovirusa | 3 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Nonenterovirus | 6 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| HEV-A | 3 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 3 |

| HEV-B | 25 | 26 | 24 | 20 | 13 |

| HEV-C | 12 | 24 | 15 | 21 | 16 |

OPV-related isolates.

TABLE 3.

Isolation of HEV-C from AFP cases in Cambodia from 1999 to 2003

| HEV-C isolate | No. of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

| CAV1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| CAV11/15 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| CAV13/18 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| CAV17 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| CAV20 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| CAV21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CAV24 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| CAM2083 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 12 | 24 | 15 | 21 | 16 |

Sequence analysis of HEV-C isolates in the 3Dpol coding region.

We then analyzed the genomic sequence in the 3Dpol coding region of the HEV-C isolates. The phylogenic analysis of a part of the 3Dpol coding region (corresponding to a region of nt 6137 to 6488 of the Sabin 3 genome; 352 nt) showed that the isolates formed distinct genetic clusters from those of the prototype HEV-C strains, as observed for the sequence analysis of the VP4 coding region (Fig. 2). The phylogenic analysis of the 3Dpol coding region failed to show a clear relationship between the serotypes of isolates and their genetic clusters. For CAM1974, CAM2083, and CAM2091, we could not obtain the corresponding DNA fragment by RT-PCR. In the phylogenic analysis, a genetic cluster of indigenous CAV13-CAV18 strains was the closest to Cambodia-02. We found that a CAV13-CAV18 isolate (CAM1900) showed the highest nucleotide identity (94.0%) to Cambodia-02 among the HEV-C isolates. We further analyzed the nonstructural protein coding region of CAM1900 and found that CAM1900 showed a high identity to Cambodia-02 only in the 3Dpol coding region (94.9%) but not in other regions (Fig. 3A and C).

In the phylogenic analysis of the 3Dpol coding region, we found that a CAV17 isolate, CAM2069, was located apart from other CAV17 isolates in a genetic cluster of indigenous CAV13-CAV18 strains. The sequence analysis of CAM2069 showed that CAM2069 exhibited a high (95.5 to 97.7%) nucleotide identity to CAM2101 (a CAV17 isolate) for the 2C and the 3AB coding regions. However, the 3CDpro coding region of CAM2069 showed high (93.3 to 95.5%) nucleotide identity to that of CAV13-CAV18, as observed in the phylogenic analysis of the 3Dpol coding region (Fig. 2) and in the similarity plot analysis (Fig. 3C). This observation suggested that recombination between CAV13-CAV18 and CAV17 could occur at least in the 3CDpro coding region.

Sequence analysis of HEV-C isolates in the 2BC coding region.

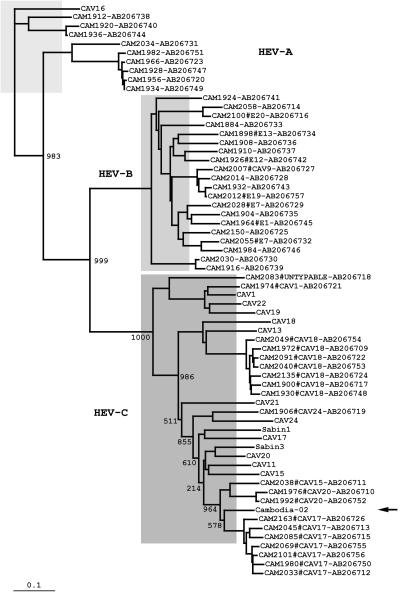

Next, we analyzed the sequence of another nonstructural protein coding region of HEV-C isolates, because the analysis in the 3Dpol coding region failed to identify the recombination counterpart. For this purpose, we designed a new primer set for RT-PCR and DNA sequencing, 2A2+ and 2C−, in the 2Apro coding region and in a cis-acting replication element in the 2C coding region (19, 40), respectively. By using this primer set, we analyzed a sequence of the 2BC coding region (corresponding to nt 3854 to 4190 of the Sabin 3 genome; 337 nt) for all the NPEV isolates (Fig. 4). We then analyzed the sequence of three isolates (CAM1920, CAM1936, and CAM2034) for which we could not analyze the sequence of the VP4 coding region. However, one isolate (CAM1952, a CAV24 strain) failed to give an RT-PCR product. In the phylogenic analysis of the 2BC coding region, we observed a close relationship between the serotypes of isolates and the genetic clusters. In this phylogenic analysis, Cambodia-02 was again located close to the genetic clusters of indigenous HEV-C but not to those of the HEV-C prototypes. CAM2101 (a CAV17 isolate) showed the highest nucleotide identity to Cambodia-02 in the 2BC coding region; however, the identity was not significantly high (86.9%).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenic analysis of the 2BC coding region. The phylogenic tree was generated from the nucleotide sequences in the 2BC coding region of Cambodian NPEV isolates, prototype HEV-C strains, and Sabin strains. The location of Cambodia-02 is indicated by an arrow. The nomenclature of the isolates indicates the names of the isolates, serotypes, and the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers. Bootstrap values are shown at the branch nodes. Bar, 0.1 substitution per site.

HEV-C isolates from AFP cases in Cambodia from 1999 to 2003.

To identify the recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02, we further analyzed the NPEV isolates from 1999 to 2003 in Cambodia. HEV-C was a dominant HEV species isolated from AFP cases in this period, suggesting that the prevalence of HEV-C was consistently high in Cambodia (Table 2 and 3). The dominant serotypes of HEV-C were different from year to year; in 2002, they were CAV17 and CAV13-CAV18. In the phylogenic analysis of the 2BC coding region, Cambodia-02 was grouped into a cluster of the indigenous CAV15-CAV17-CAV20 isolates. However, the nucleotide identity was not significantly high, and the highest (90.1%) was found with a CAV17 isolate in 2000 (data not shown). Therefore, we could not identify the exact recombination counterpart among the HEV-C isolates examined. However, these results suggested that the recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02 was genetically closely related to the indigenous HEV-C strains in Cambodia.

DISCUSSION

A Sabin 3-derived PV recombinant (Cambodia-02) analyzed in this study was isolated from an AFP case in Cambodia in 2002. Cambodia-02 was classified as OPV-like PV by sequence analysis in the VP1 coding region. In 2002, we isolated three type 3 PVs, including Cambodia-02, from AFP cases in Cambodia, but these PV isolates were genetically unrelated to each other (data not shown). Therefore, this evidence suggested that Cambodia-02 was isolated from a sporadic AFP case and did not result from a circulating strain.

Cambodia-02 was isolated within 6 months after the administration of OPV, as determined on the basis of the previous estimation of the evolution rate of PVs (2, 17). Thus, the unidentified sequence of Cambodia-02 should have retained the original genetic feature of the recombination counterpart. The last indigenous PV case in Cambodia was reported in 1997 (7); therefore, we examined HEV-C strains for the recombination counterpart. We examined HEV-C isolates from AFP cases in Cambodia; however, these isolates represented only a minor population of circulating HEV-C strains that would mostly result in asymptomatic infection. Therefore, through this strategy, we could expect to find some HEV-C strains that were only related to the recombination counterpart. We found that HEV-C was a dominant enterovirus species that could be isolated from the AFP cases in Cambodia (Table 2). The HEV-C isolates consisted of CAV1, CAV11-CAV15, CAV13-CAV18, CAV17, CAV20, CAV21, CAV24, and an untypable serotype represented by CAM2083 (Table 3). HEV-C strains have not been isolated as major NPEVs through the established enterovirus surveillance systems (5, 9) (http://idsc.nih.go.jp/iasr/prompt/circle-g/meningi/menin.html [in Japanese]). However, recently, a high frequency of HEV-C isolation (∼50% of the isolates) was reported in Madagascar, where type 2 cVDPVs emerged in 2002 (10, 41). Therefore, HEV-C might be a dominant HEV species among the circulating enteroviruses in tropical areas. However, the prevalence of HEV-C in other tropical areas remained to be further investigated.

We performed a comprehensive sequence analysis of HEV-C isolates in three different genomic regions, including the 2BC coding region and the 3Dpol coding region (20, 39, 43) (Fig. 2 and 4). We designed a new primer set, 2A2+ and 2C−, for the analysis of the 2BC coding region (Table 1). The 2A2+ primer was designed in the 2Apro coding region, and the 2C− primer was designed in a cis-acting replication element of the enterovirus (19, 40). This primer set showed a broad spectrum of applicability for HEV-A, HEV-B, and HEV-C isolates, and sequence analysis using this primer set failed for only one isolate (CAM1952 [CAV24]) among 216 NPEV isolates. Recombination junctions of cVDPV have been identified in the 2AB coding region (6, 8, 10, 24). Therefore, with a wide spectrum of applicability for NPEV, this primer set would serve as a useful tool to identify HEV-C strains related to the recombination counterpart of cVDPV.

From the sequence analysis, we found that the nonstructural protein coding regions of Cambodia-02 were grouped into the genetic clusters of the indigenous CAV17 and CAV13-CAV18 strains in Cambodia, distinct from those of the HEV-C prototype strains (Fig. 2 and 4). We isolated CAV17 from 2001 to 2002 and CAV13-CAV18 from 2002 to 2003. Thus, both CAV17 and CAV13-CAV18 were highly prevalent and could be available as the recombination counterpart of Cambodia-02 in 2002. One of the CAV13-CAV18 isolates (CAM1900) showed the highest (94.9%) nucleotide identity to Cambodia-02 in the 3Dpol coding region (Fig. 4). The nucleotide identities in the 3Dpol coding region among isolates with the same HEV-C serotype isolated in 2002 were 95 to 96% (Fig. 3), and Cambodia-02 showed a nucleotide identity comparable to indigenous HEV-C isolates in 2002. This suggested that these HEV-C isolates had evolved independently before the putative epidemic in 2002. Interestingly, we found a putative CAV recombinant (CAM2069) in the 3CDpro coding region, suggesting frequent interserotypic recombination between CAV17 and CAV13-CAV18 in this region (Fig. 4). Actually, the 3CDpro coding region showed high similarities among CAV13-CAV18, CAV11-CAV15, CAV17, and CAV20 (4, 22). This was reminiscent of frequent recombination among HEV-B strains and also among human rhinoviruses where the 3Dpol coding regions of the same serotype were not monophyletic (27, 30, 38, 47). However, we could not find the exact recombination counterpart among the indigenous HEV-C isolates from AFP cases, although their nonstructural protein coding region was closely related to that of Cambodia-02.

In summary, we isolated a type 3 PV recombinant from an AFP case in Cambodia and suggested that the unidentified sequence of the recombinant was derived from an indigenous HEV-C strain in Cambodia. In addition to the poor population immunity, the high prevalence of HEV-C would be another critical factor for the emergence and/or the evolution of cVDPV. The biological roles of the recombination of cVDPV remain to be further studied.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Feldon and Cambodian local and regional EPI staffs for their expert surveillance. We are grateful to Junko Wada for her excellent assistance.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for “Promotion of Polio Eradication” from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, and by a grant for health research from the regional office for the Western Pacific, World Health Organization. H.S. was supported in part by grants-in-aid for “Development of Expanded Programme on Immunization and Accelerating Measles Control in the Polio-free Era” from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, J. P., Jr., H. E. Gary, Jr., and M. A. Pallansch. 1997. Duration of poliovirus excretion and its implications for acute flaccid paralysis surveillance: a review of the literature. J. Infect. Dis. 175:S176-S182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellmunt, A., G. May, R. Zell, P. Pring-Akerblom, W. Verhagen, and A. Heim. 1999. Evolution of poliovirus type I during 5.5 years of prolonged enteral replication in an immunodeficient patient. Virology 265:178-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boot, H. J., D. T. Kasteel, A. M. Buisman, and T. G. Kimman. 2003. Excretion of wild-type and vaccine-derived poliovirus in the feces of poliovirus receptor-transgenic mice. J. Virol. 77:6541-6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, B., M. S. Oberste, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid coding region. J. Virol. 77:8973-8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caro, V., S. Guillot, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2001. Molecular strategy for ‘serotyping’ of human enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 82:79-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Acute flaccid paralysis associated with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus—Philippines, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:874-875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Certification of poliomyelitis eradication—Western Pacific Region, October 2000. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Circulation of a type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus—Egypt, 1982-1993. JAMA 285:1148-1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Enterovirus surveillance—United States, 2000-2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:1047-1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Poliomyelitis—Madagascar, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:622. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Western Pacific Region, January 1, 1996-September 27, 1997. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46:1113-1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherkasova, E. A., E. A. Korotkova, M. L. Yakovenko, O. E. Ivanova, T. P. Eremeeva, K. M. Chumakov, and V. I. Agol. 2002. Long-term circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus that causes paralytic disease. J. Virol. 76:6791-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans, D. M., G. Dunn, P. D. Minor, G. C. Schild, A. J. Cann, G. Stanway, J. W. Almond, K. Currey, and J. V. Maizel. 1985. Increased neurovirulence associated with a single nucleotide change in a noncoding region of the Sabin type 3 poliovaccine genome. Nature 314:548-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filman, D. J., R. Syed, M. Chow, A. J. Macadam, P. D. Minor, and J. M. Hogle. 1989. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 8:1567-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine, P. E., and I. A. Carneiro. 1999. Transmissibility and persistence of oral polio vaccine viruses: implications for the global poliomyelitis eradication initiative. Am. J. Epidemiol. 150:1001-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavrilin, G. V., E. A. Cherkasova, G. Y. Lipskaya, O. M. Kew, and V. I. Agol. 2000. Evolution of circulating wild poliovirus and of vaccine-derived poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient: a unifying model. J. Virol. 74:7381-7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelfand, H. M., P. L., D. R. LeBlanc, and J. P. Fox. 1959. Revised preliminary report on the Louisiana observations of the natural spread within families of living vaccine strains of poliovirus, p. 203-217. First international conference on live poliovirus vaccines. Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Goodfellow, I., Y. Chaudhry, A. Richardson, J. Meredith, J. W. Almond, W. Barclay, and D. J. Evans. 2000. Identification of a cis-acting replication element within the poliovirus coding region. J. Virol. 74:4590-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillot, S., V. Caro, N. Cuervo, E. Korotkova, M. Combiescu, A. Persu, A. Aubert-Combiescu, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2000. Natural genetic exchanges between vaccine and wild poliovirus strains in humans. J. Virol. 74:8434-8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horie, H., H. Yoshida, K. Matsuura, M. Miyazawa, Y. Ota, T. Nakayama, Y. Doi, and S. Hashizume. 2002. Neurovirulence of type 1 polioviruses isolated from sewage in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:138-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyypia, T., T. Hovi, N. J. Knowles, and G. Stanway. 1997. Classification of enteroviruses based on molecular and biological properties. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishiko, H., Y. Shimada, M. Yonaha, O. Hashimoto, A. Hayashi, K. Sakae, and N. Takeda. 2002. Molecular diagnosis of human enteroviruses by phylogeny-based classification by use of the VP4 sequence. J. Infect. Dis. 185:744-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kew, O., V. Morris-Glasgow, M. Landaverde, C. Burns, J. Shaw, Z. Garib, J. Andre, E. Blackman, C. J. Freeman, J. Jorba, R. Sutter, G. Tambini, L. Venczel, C. Pedreira, F. Laender, H. Shimizu, T. Yoneyama, T. Miyamura, H. van Der Avoort, M. S. Oberste, D. Kilpatrick, S. Cochi, M. Pallansch, and C. deq Uadros. 2002. Outbreak of poliomyelitis in Hispaniola associated with circulating type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus. Science 296:356-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kew, O. M., R. W. Sutter, B. K. Nottay, M. J. McDonough, D. R. Prevots, L. Quick, and M. A. Pallansch. 1998. Prolonged replication of a type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2893-2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindberg, A. M., P. Andersson, C. Savolainen, M. N. Mulders, and T. Hovi. 2003. Evolution of the genome of human enterovirus B: incongruence between phylogenies of the VP1 and 3CD regions indicates frequent recombination within the species. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1223-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, H. M., D. P. Zheng, L. B. Zhang, M. S. Oberste, O. M. Kew, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Serial recombination during circulation of type 1 wild-vaccine recombinant polioviruses in China. J. Virol. 77:10994-11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lole, K. S., R. C. Bollinger, R. S. Paranjape, D. Gadkari, S. S. Kulkarni, N. G. Novak, R. Ingersoll, H. W. Sheppard, and S. C. Ray. 1999. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J. Virol. 73:152-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukashev, A. N., V. A. Lashkevich, O. E. Ivanova, G. A. Koroleva, A. E. Hinkkanen, and J. Ilonen. 2003. Recombination in circulating enteroviruses. J. Virol. 77:10423-10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macadam, A. J., C. Arnold, J. Howlett, A. John, S. Marsden, F. Taffs, P. Reeve, N. Hamada, K. Wareham, J. Almond, N. Cammack, and P. D. Minor. 1989. Reversion of the attenuated and temperature-sensitive phenotypes of the Sabin type 3 strain of poliovirus in vaccinees. Virology 172:408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacLennan, C., G. Dunn, A. P. Huissoon, D. S. Kumararatne, J. Martin, P. O'Leary, R. A. Thompson, H. Osman, P. Wood, P. Minor, D. J. Wood, and D. Pillay. 2004. Failure to clear persistent vaccine-derived neurovirulent poliovirus infection in an immunodeficient man. Lancet 363:1509-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendelsohn, C. L., E. Wimmer, and V. R. Racaniello. 1989. Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell 56:855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minor, P. D. 1992. The molecular biology of polio vaccines. J. Gen. Virol. 73:3065-3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nkowane, B. M., S. G. Wassilak, W. A. Orenstein, K. J. Bart, L. B. Schonberger, A. R. Hinman, and O. M. Kew. 1987. Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis. United States: 1973 through 1984. JAMA 257:1335-1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, D. R. Kilpatrick, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J. Virol. 73:1941-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberste, M. S., W. A. Nix, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Improved molecular identification of enteroviruses by RT-PCR and amplicon sequencing. J. Clin. Virol. 26:375-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oberste, M. S., S. Penaranda, and M. A. Pallansch. 2004. RNA recombination plays a major role in genomic change during circulation of coxsackie B viruses. J. Virol. 78:2948-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olive, D. M., S. Al-Mufti, W. Al-Mulla, M. A. Khan, A. Pasca, G. Stanway, and W. Al-Nakib. 1990. Detection and differentiation of picornaviruses in clinical samples following genomic amplification. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2141-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paul, A. V., E. Rieder, D. W. Kim, J. H. van Boom, and E. Wimmer. 2000. Identification of an RNA hairpin in poliovirus RNA that serves as the primary template in the in vitro uridylylation of VPg. J. Virol. 74:10359-10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rakoto-Andrianarivelo, M., D. Rousset, R. Razafindratsimandresy, S. Chevaliez, S. Guillot, J. Balanant, and F. Delpeyroux. 2005. High frequency of human enterovirus species C circulation in Madagascar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:242-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robbins, F. C., and C. A. de Quadros. 1997. Certification of the eradication of indigenous transmission of wild poliovirus in the Americas. J. Infect. Dis. 175:S281-S285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rotbart, H. A. 1990. Enzymatic RNA amplification of the enteroviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:438-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabin, A. B. 1965. Oral poliovirus vaccine. History of its development and prospects for eradication of poliomyelitis. JAMA 194:872-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salk, J. E. 1960. Persistence of immunity after administration of formalin-treated poliovirus vaccine. Lancet ii:715-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savolainen, C., P. Laine, M. N. Mulders, and T. Hovi. 2004. Sequence analysis of human rhinoviruses in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase coding region reveals large within-species variation. J Gen. Virol. 85:2271-2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semler, B. L., and E. Wimmer. 2002. Molecular biology of picornavirus, p. 387. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 49.Shimizu, H., B. Thorley, F. J. Paladin, K. A. Brussen, V. Stambos, L. Yuen, A. Utama, Y. Tano, M. Arita, H. Yoshida, T. Yoneyama, A. Benegas, S. Roesel, M. Pallansch, O. Kew, and T. Miyamura. 2004. Circulation of type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in the Philippines in 2001. J. Virol. 78:13512-13521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization. 2004. Polio laboratory manual, 4th ed. W.H.O./IVB/04.10. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 51.Yang, C. F., T. Naguib, S. J. Yang, E. Nasr, J. Jorba, N. Ahmed, R. Campagnoli, H. van der Avoort, H. Shimizu, T. Yoneyama, T. Miyamura, M. Pallansch, and O. Kew. 2003. Circulation of endemic type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus in Egypt from 1983 to 1993. J. Virol. 77:8366-8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida, H., H. Horie, K. Matsuura, and T. Miyamura. 2000. Characterisation of vaccine-derived polioviruses isolated from sewage and river water in Japan. Lancet 356:1461-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.