Abstract

The human eye is an important target for infection with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). Damage to cells forming the trabeculum of the eye by HSV-1 infection could contribute to the development of glaucoma, a major blinding disease. Primary cultures of human trabecular meshwork cells were used as an in vitro model to demonstrate the ability of HSV-1 to enter into and establish a productive infection of the trabeculum. Blocking of entry by anti-herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) antibody implicated HVEM as the major receptor for HSV-1 infection.

The trabecular meshwork (TM), a specialized eye tissue, is the major site for regulation of the aqueous humor outflow. Inflammation of cells in the TM (trabeculitis) due to herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection during corneal endotheliitis and uveitis leads to elevated intraocular pressure, which is a major risk factor for glaucoma, a major blinding disease (1, 19, 21, 25, 32). Recently, immunoreactivity for HSV-1 in the trabeculum of the human eye was demonstrated during corneal endotheliitis (1, 19). HSV-1-induced inflammation of human TM cells impedes aqueous outflow and increases intraocular pressure, as has also been reported with Posner Schlossman syndrome (11, 38). The virus has been detected in aqueous humor (40), tears (14), and ciliary ganglia (2) that innervate the cells of the trabeculum. It is, however, ironic that the ability of the virus to invade and productively infect TM cells remains poorly understood and that several aspects of the virus, including the identity of the mediators of the virus entry into these cells, remain unknown. Since HSV-1 infection of TM cells is a risk factor for glaucoma and uveitis, understanding HSV-1 entry and major entry mediators in TM cells becomes important for designing novel strategies to prevent blindness. Therefore, using primary cultures of human TM cells as a model, the present study was undertaken to determine the susceptibility and the mediator(s) of productive HSV-1 entry into TM cells.

HSV entry into cells is a complex process that is initiated by specific interaction of viral envelope glycoproteins and host cell surface receptors (31). The virus uses glycoproteins B and C (gB and gC, respectively) to mediate the initial attachment to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (12, 27). Binding of herpesviruses to heparan sulfate proteoglycans likely precedes a conformational change that brings viral glycoprotein D (gD) to the binding domain of host cell surface gD receptors (7, 8, 15). Thereafter, a concerted action involving gD, its receptor, three additional HSV glycoproteins (gB, gH, and gL), and possibly an additional gH coreceptor triggers fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane of host cells (22, 23, 26). To date, three classes of HSV entry receptors have been identified (30, 31). They include herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) (20), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (17); nectin-1 and nectin-2 (3, 5, 10), two members of the immunoglobulin superfamily; and specific sites in heparan sulfate generated by certain isoforms of 3-O-sulfotransferases (28, 29, 36, 37). It was recently shown that 3-O-sulfotransferase-generated heparan sulfate (3-OS HS) also acts as a fusion receptor similar to the protein receptors (34). The relative abundance of the receptors varies with cell type, and this variation might influence the course of HSV-1 infection. For example, HVEM is expressed in various tissues, including liver, lung, and kidney, and a variety of cell types, including T and B lymphocytes, leukocytes, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts, but probably not in neurons; hence, HVEM is likely not critical for virus entry into neuronal cells, which is likely mediated by nectin-1 (24, 30).

Cultured human TM cells are susceptible to HSV-1 entry and replication.

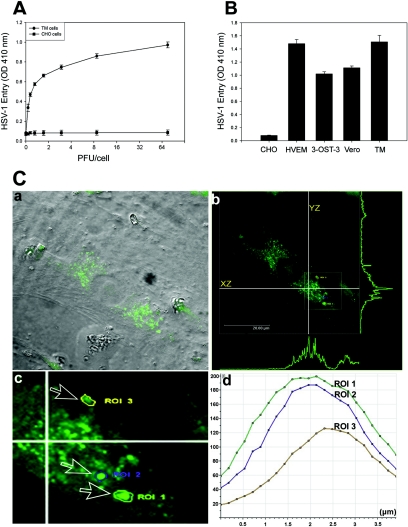

The TM cultures were prepared, in accordance with federal guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, from explanted human tissues (provided by the Illinois Eye Bank, Chicago, IL) as previously described (39). To determine HSV-1 entry, a confluent monolayer of cultured TM cells was plated in 96-well tissue culture dishes and infected with serial dilutions of recombinant HSV-1 (KOS) gL86, which expresses β-galactosidase upon entry into cells (20). Wild-type Chinese hamster ovary-K1 (CHO-K1) cells lacking functional gD receptors were used as the control. As shown in Fig. 1A, compared to HSV-1 entry into CHO-K1 cells, HSV-1 entry into human TM cells was detected in a dose-dependent manner. Next, in order to develop a better appreciation of HSV-1 entry, we decided to compare entry into TM cells with entry into gD receptor (HVEM and 3-OS HS)-expressing CHO-K1 cells and Vero cells. Vero cells are naturally susceptible to HSV-1 (33). In parallel assays (data not shown), the HSV-1 dose response observed with TM cells was similar to that with Vero cells and CHO-K1 cells expressing gD receptors HVEM and 3-OS HS. As expected, wild-type CHO-K1 cells (without any receptors) remained resistant to HSV-1 entry. A representative result, at a single virus dose (40 PFU/cell), is shown in Fig. 1B. Further, to generate more direct and visual evidence of HSV-1 entry, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged HSV-1 (K26GFP) (4) virions. Fluorescence-tagged viruses are powerful tools for the analysis of viral infection (6). High-resolution confocal microscopy was used to detect fluorescent virus particles inside infected TM cells. Figure 1C, panel a, shows green fluorescent virions in a cell under bright field illumination that was overlaid with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) fluorescent channel. The image of the infected cell was later captured at multiple z stacks (xz and yz planes) by using the FITC fluorescent channel, and the corresponding maximum projection intensities were recorded (Fig. 1C, panel b). Clearly, the maximum fluorescence intensity was found in the mid-xz and mid-yz planes, suggesting that the majority of viral capsids were present in the inner sections of the infected cell. To further verify the location of the virions in the middle inner section of the cell, we selected three regions of interest (ROI) from the same cell (inset in Fig. 1C, panel b, which is enlarged in Fig. 1C, panel c) and traced the GFP intensity serially through the z stacks. Clearly, the maximum fluorescence emitted (suggesting the highest probability of virus presence) was found near or in the mid-z sections (Fig. 1C, panel d). The confocal microscopy results confirm our virus entry data obtained from the entry assay and provide the first evidence of virus entry into primary cultures of human TM cells. Recently, primary neuronal cultures have been used successfully to demonstrate HSV-1 entry (13, 24).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of HSV-1 entry in primary cultures of human TM cells. (A) Entry of human HSV-1 into cultured human TM cells. Cultured TM cells, along with wild-type CHO-K1 cells, were plated in 96-well plates and inoculated with twofold serial dilutions of β-galactosidase-expressing recombinant virus HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 at the PFU/cell indicated. After 6 h, the cells were washed, permeabilized, and incubated with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ImmunoPure ONPG; Pierce) substrate for quantitation of β-galactosidase activity expressed from the input viral genome. The enzymatic activity was measured by spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) at an optical density (OD) at 410 nm. Each value shown is the mean (± standard deviation) of three or more determinations. (B) Comparison of levels of HSV-1 entry into multiple cell types. Entry of HSV-1 into cultured human TM cells was compared to entry into naturally susceptible Vero cells and CHO-K1 cells expressing either HVEM or 3-OS HS as gD receptors. Approximately equal numbers of cells (20,000 cells per well, per Beckman counter estimate) were plated in 96-well plates at least 16 h prior to infection. All cell types were then treated with serial dilutions of β-galactosidase-expressing recombinant virus HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 for 6 h before the cells were washed and permeabilized, and substrate (ONPG) was added to measure the viral entry. The values shown (means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations) represent the amount of reaction product detected spectrophotometrically at a single input dose of 40 PFU/cell. (C) Visualization of GFP-tagged HSV-1 (K26GFP) particles in cultured human TM cells by using confocal microscopy. Human TM cells were infected as described in the text. (a) Bright field image of cultured human TM cells overlaid with FITC fluorescent channel. Fluorescent viral capsids are seen in green. (b) Orthogonal section of the maximum projection of a z stack sliced at two different axes (xz and yz). Maximum fluorescence intensities are shown as green peaks. The inset shows the three ROI described in the text. (c) Enlarged view of the ROI (labeled and indicated by arrows). (d) Histogram of fluorescent intensities (y axis) obtained for z stacks (x axis). The total depth of the z stack was 4 μm.

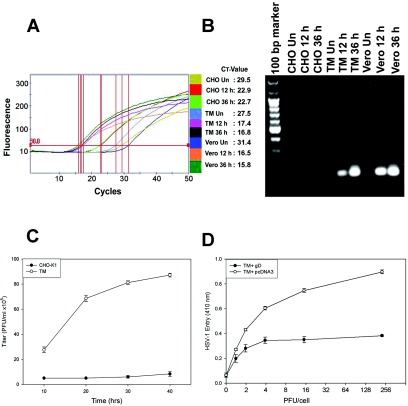

Since TM cells were found to be highly susceptible to HSV-1 entry, we next determined whether HSV-1 was able to replicate in cultured human TM cells by using real-time quantitative PCR. We employed a fluorescent, double-strand-specific dye (SYBR green; Sigma) probe and HSV-1 gD as a target gene. The protocol for the purification of viral DNA from cultured cells was followed according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAamp DNA mini kit). Confluent cultures of TM, Vero, and wild-type CHO-K1 cells were infected with 5 PFU/cell of recombinant HSV-1 (gL86) in a 6-well dish for 12 and 36 h prior to DNA extraction. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using a SmartCycler (Cepheid). The final PCR mixtures contained 2.5 μl of primer mix (final concentration of 300 nM each), 10 μl of SYBR green Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) supplemented with 3.5 mM MgCl2, and 5 μl of DNA from the prepared samples (mock- and virus-infected cells at different time points) in a total volume of 25 μl. Primers were designed using the Clone Manager 6 program (Sci-ed Central) and are listed in Table 1. The mock-infected TM, Vero, and CHO-K1 cells were used as the respective negative controls. Quantification was performed with standard curve as outlined in Fig. 2A. Amplified PCR samples were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2B). The predicted size (129 bp) of the PCR product for HSV-1 gD was obtained for infected Vero and TM cells but not for mock-infected TM cells or virus-infected CHO-K1 cells. The result obtained by real-time PCR quantitation shows that HSV-1 DNA is able to replicate in human TM cells. To gain further insight of the viral replication into human TM cells, replication kinetics of HSV-1 was established using a plaque assay. Monolayers of cultured TM cells containing approximately 4 × 106 cells in a 25-ml flask were infected with HSV-1 (KOS) virus (0.01 multiplicity of infection) for 2 h at 37°C. Wild-type CHO-K1 cells infected under similar conditions were used as a negative control. After removal of the inoculum, monolayers were overlaid with minimal essential medium containing 2.5% heat-inactivated calf serum and incubated at 37°C until the time of harvest (10 to 40 h). Yields of infectious virus titer were determined on Vero cells cultured in triplicate by using an overlay of medium containing methylcellulose. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, fixed in alcohol, and stained with Giemsa stain. Infectivity was recorded as PFU/ml at different time points. It was evident that HSV-1 infection of TM cells exhibited enhanced yields of the infectious virus particles over time (Fig. 2C). In contrast, wild-type CHO-K1 cells produced virtually no infectious viral particles. This result, together with real-time PCR data demonstrating viral replication, suggests that susceptibility of cultured TM cells to HSV-1 entry is biologically relevant. Clearly, such infection could cause damage to TM cells and even neighboring cells during viral spread.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR assay of HSV-1-infected human TM cells

| Primera | Sequence (5′-3′) | Gene targetb | Length (nucleotides) | G+C content (%) | Tm (°C)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward HSV-1 (KOS) | AAGACCTTCCGGTCCTG | gD | 17 | 58.8 | 60.2 |

| Backward HSV-1 (KOS) | TCCAACACGGCGTAGTA | gD | 17 | 52.9 | 58.7 |

Positions of primers: forward, nucleotides 135 to 151; backward, nucleotides 248 to 264. Product size: 129 bp. Probe: SYBR green Taq ReadyMix for quantitative PCR.

GenBank accession number L09243.

Tm, melting temperature.

FIG. 2.

Entered HSV-1 replicates in human TM cells, and entry is sensitive to gD-mediated interference. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of entry. Fluorescence curve along with cycle threshold (CT) values are shown for each sample. The parameter CT is defined as the fractional cycle number at which the fluorescence passes the fixed threshold. Vero, TM, and CHO-K1 cells were infected with HSV-1. Total cell DNA was isolated 12 and 36 h postinfection and analyzed by RT-PCR. The reaction was carried out using the following conditions for the target HSV-1 (KOS) (gD). First, DNA was denatured at 95°C for 420 s, and the template was amplified for 50 cycles by denaturing DNA at 95°C for 30 s followed by annealing of primers at 58°C for 10 s and extension at 72°C for 16 s. After amplification, one cycle of melting curve from 60 to 95°C by a transition rate of 0.2°C/s, with continuous detection of fluorescence, was performed. Un, untreated. (B) Visualization of viral DNA. PCR products (20 μl) electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose (SeaKem LE agarose; Cambrex) Tris-acetate-EDTA (1×) gel containing ethidium bromide verified the amplification product (HSV-1 gD) of the predicted size (129 bp) with no primer dimer bands. Un, uninfected. (C) HSV-1 infection of TM cells leads to infectious yields of the virus. Confluent monolayers of TM and wild-type CHO-K1 cells were infected with HSV-1 at 0.01 PFU per cell for 90 min at 37°C. Inocula were harvested at the indicated times (10 to 40 h) postinfection. The infectious viral titers for each time point (PFU/ml) were determined in triplicate on Vero cells by plaque assay, which indicated that the viral titers in cultured corneal fibroblasts increased over the time period. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of results in triplicate wells from a representative experiment. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (D) Expression of HSV-1 gD in human TM cells interferes with HSV-1 entry. Cultured human TM cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing HSV-1 gD (pPEP99) (TM + gD) or with empty plasmid (pcDNA3) (TM + pcDNA3) as a control. Fourteen hours later, the cells were replated on 96-well plates and exposed to β-galactosidase-expressing HSV-1 (KOS) gL86. Six hours after inoculation, cells were lysed and β-galactosidase activities were determined as a measure of virus entry.

Expression of HSV-1 gD in cultured human TM cells renders resistance to HSV-1 entry.

In order to determine if the gD receptors played a role in infection of TM cells by HSV-1, a gD-mediated interference assay was used (9). This assay is based on the principle that cells that are normally susceptible to viral entry become resistant upon expression of viral gD due to sequestration of gD receptors by cell-expressed gD. Human TM cells were transiently transfected (TransIT-TKO; Mirus) with an HSV-1 gD-expressing plasmid (or an equal amount of empty vector, pcDNA3, as a control), followed by infection with serial dilutions of β-galactosidase-expressing HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 (9, 29). As shown in Fig. 2D, HSV-1 entry into TM cells expressing gD was approximately twofold lower than entry into the control TM cells transfected with empty vector. Thus, viral entry into human TM cells is likely mediated by gD receptors expressed on the TM cell surface in a gD-dependent manner.

Human TM cells express HVEM and 3-OST-3 but not nectin-1 and nectin-2.

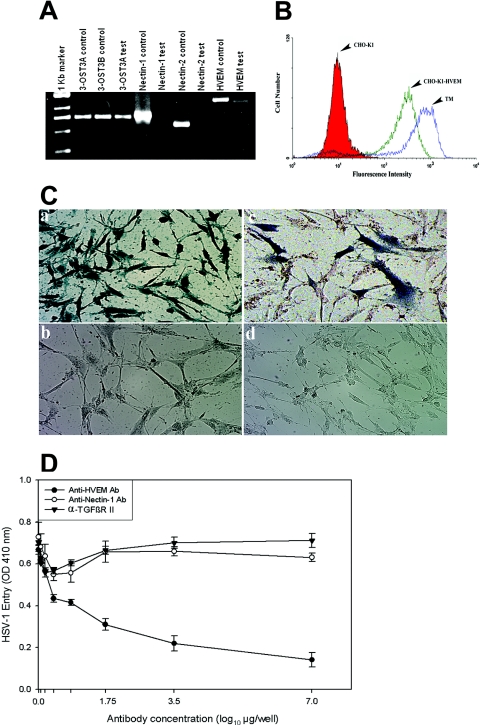

To determine the identity of gD receptors expressed in human TM cells, additional reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR experiments were performed. Total RNA was isolated from cultured TM cells by using a QIAGEN RNeasy kit (QIAGEN Corp., Valencia, CA). Superscript II RT (Invitrogen Corp.) was used for RT-PCR. The PCR amplification of cDNAs was done with primers 5′-TCTCTGCTGCCAGACA-3′ and 5′-GCCACAGCAGAACAGA-3′ for HVEM; 5′-TCCTTCACCGATGGCACTATCC-3′ and 5′-TCAACACCAGCAGGATGCTC-3′ for nectin-1; and 5′-AGAAGCAGCAGCACCAGCAG-3′ and 5′-GTCACGTTCAGCCAGGA-3′ for nectin-2. The 3-O-sulfotransferase-3 (3-OST-3) sequences were amplified using primers 5′-CAGGCCATCATCATCGG-3′ and 5′-CCGGTCATCTGGTAGAA-3′. The expected sizes of the PCR products were 1,270 bp for HVEM, 738 bp for nectin-1, 616 bp for nectin-2, and 736 bp for 3-OST-3. As shown in Fig. 3A, the expected PCR products were detected for HVEM and 3-OST-3 (both A and B isoforms), but not for nectin-1 and nectin-2. While the expression of 3-OST-3 specific mRNAs in TM cells was very interesting, the absence of nectin-1-specific product was unexpected since it is generally thought to be well expressed in cell lines and tissues (10), including murine eye (35). To address the potential significance in entry, HVEM expression on the surface of TM cells was verified by flow cytometry using anti-HVEM antibody. As shown, both HVEM-expressing CHO-K1 and TM cells were positive for HVEM expression (Fig. 3B). Wild-type CHO-K1 cells were used as a negative control.

FIG. 3.

HVEM is the major mediator of entry into TM cells. (A) mRNAs specific to HVEM and 3-OST-3 but not to nectin-1 or nectin-2 were detected in TM cells. RT-PCR assays were performed. cDNAs were produced from total RNA isolated from the cells. PCR was performed using primers specific to each receptor (indicated at top). Either the expression plasmids for each receptor (indicated as controls) or cDNA isolated from TM cells (indicated as tests) were used as templates. The products were separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and then stained with ethidium bromide. Amplification products specific to HVEM and 3-OST-3 but not to nectin-1 or nectin-2 were detected in cDNAs generated from TM cells. (B) Cell surface expression of HVEM in TM cells detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Monolayers of cultured TM cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with anti-HVEM antibody (1:200 dilution). CHO-K1 cells stably expressing HVEM (CHO-K1-HVEM) and wild-type CHO-K1 cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cells were examined by FACS analysis after 30 min of incubation with secondary anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (1:500 dilution) conjugated with FITC. (C) TM cells are resistant to BHV-1 entry. Cultured human TM cells (panels a and b), TM cells transiently transfected with the nectin-1 expression plasmid pBG38 (panel c), or TM cells mock transfected with empty vector (panel d) were exposed to β-galactosidase-expressing recombinants (40 PFU/cell) of HSV-1 (panel a) and BHV-1 (panels b, c, and d). After 6 h of infection at 37°C, cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed and permeabilized, and incubated with X-Gal (Invitrogen), which yields an insoluble blue product upon hydrolysis by β-galactosidase. Microscopy was performed using a 20× objective of the inverted microscope (Axiovert 100 M; Zeiss). The slide book version 3.0 was used for images. Blue cells (representing viral entry) were seen as shown. (D) Anti-HVEM polyclonal antibody, but not anti-nectin-1 antibody, inhibits HSV-1 entry into cultured human TM. Cells plated in 96-well plates were incubated with twofold dilutions of the anti-HVEM antibody (Ab), anti-nectin-1 Ab, and a control with α-TGFβR II Ab for 1 h 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then challenged with equal doses of HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 prepared in PBS with 1% glucose and 0.1% heat-inactivated calf serum at 37°C. After 2 h 30 min, cells were washed one time with PBS and treated for a short period with citrate buffer. Finally, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 4 h in PBS buffer at 37°C. The substrate, ImmunoPure ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), was prepared in PBS buffer with nonionic detergent (Igepal CA-630; Sigma), and β-galactosidase activity was read at an optical density (OD) at 410 nm. The concentrations of the antibody used are expressed in μg/well. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Expression of nectin-1 in TM cells allows BHV-1 entry.

To further verify that nectin-1 is not expressed in human TM cells, bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) entry into TM cells was examined. Among the known entry receptors, BHV-1 uses exclusively nectin-1 for entry into mammalian cells (10). As shown in Fig. 3C, X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) activity was found to be positive for human TM cells infected with HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 (Fig. 3C, panel a) and negative for BHV-1 (Cooper) v4a (18) (Fig. 3C, panel b), indicating the inability of BHV-1 to enter into TM cells. However, upon transient transfection of the nectin-1 expression plasmid (pBG38) (10) at a concentration of 1.5 μg/μl, many TM cells became susceptible to BHV-1 cell entry (Fig. 3C, panel c), suggesting the dependence of BHV-1 on nectin-1 for entry into TM cells. In parallel, TM cells transiently transfected with the control plasmid (pcDNA3 at 1.5 μg/μl) remained resistant to BHV-1 entry. Taken together, these findings provide further support that nectin-1 is not expressed in cultured human TM cells.

Anti-HVEM antibody blocks HSV-1 entry in cultured human TM cells.

To test the possible significance of HVEM as the major mediator of HSV-1 entry into human TM cells, the effects of a previously characterized entry-blocking anti-HVEM antibody (20), along with a mouse monoclonal anti-nectin-1 antibody (R1.302; Immunotech) with known ability to block nectin-1-mediated entry (3), were studied. For the experiments, TM cells plated on 96-well plates were preincubated with twofold dilutions of anti-HVEM, anti-nectin-1, and antibody to a membrane protein, α-TGFβR II (Santa Cruz, Inc., CA), for 90 min, starting with a 1:20 dilution in PBS. The cells were then infected with a fixed dose of HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 at 37°C for 2 h. The anti-HVEM antibody dose-response curve compared to control antibodies against α-TGFβR II or nectin-1 (Fig. 3D) indicates that higher concentrations of anti-HVEM antibody blocked approximately 80% of HSV-1 entry into cultured TM cells, implicating HVEM as the major entry mediator. The residual 20% entry was possibly mediated by 3-OS HS, verification of which will require 3-OS HS-specific antibodies that do not currently exist. The control antibodies, including anti-nectin-1 antibody, did not significantly reduce viral entry.

In summary, our results provide evidence that human TM cells are susceptible to HSV-1 entry and are capable of supporting viral replication. HVEM was found to play the role of the major mediator of the entry process. This is the first report of its kind implicating HVEM as the receptor for entry into an ocular cell type. Until now, HVEM was known to mediate entry into activated T lymphocytes (20). While expression of HVEM could facilitate viral infection, its high level of expression in TM cells could indicate a potential role for HVEM in immune modulation during HSV-1 infection of a human host (16, 17). Our study provides a unique example of a naturally susceptible cell type that does not express nectin-1 and uses HVEM as the major mediator of entry. It clearly suggests that receptor usage by HSV-1 could be cell type specific.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia G. Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), Thomas Mettenleiter (Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Germany), and Prashant Desai (Johns Hopkins) for reagents; Deepak Edward and David Ramsey for insightful comments; and Xiang Chen and Martin Tibudan (all from University of Illinois at Chicago) for cell cultures.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI057860 to D.S.) and a Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) career development award (D.S.). Additional support for the work was provided by a core grant (EY01792), a predoctoral fellowship (AI056680 to P.M.S.), and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (AHA0525768Z to V.T.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano, S., T. Oshika, Y. Kaji, J. Numaga, M. Matsubara, and M. Araie. 1999. Herpes simplex virus in the trabeculum of an eye with corneal endotheliitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 127:721-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustos, D. E., and S. S. Atherton. 2002. Detection of herpes simplex virus type-1 in human ciliary ganglia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43:2244-2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocchi, F., L. Menotti, P. Mirandola, M. Lopez, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 1998. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. J. Virol. 72:9992-10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai, P., and S. Person. 1998. Incorporation of the green fluorescent protein into the herpes simplex virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 72:7563-7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eberle, F., P. Dubreuil, M. G. Mattei, E. Devilard, and M. Lopez. 1995. The human PRR2 gene, related to the human poliovirus receptor gene (PVR), is the true homolog of the murine MPH gene. Gene 159:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott, G., and P. O. Hare. 1999. Live-cell analysis of a green fluorescent protein-tagged herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 73:4110-4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller, A. O., and P. G. Spear. 1987. Anti-glycoprotein D antibodies that permit adsorption but block infection by herpes simplex virus type 1 prevent virion-cell fusion at the cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:5454-5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller, A. O., and P. Perez-Romero. 2002. Mechanisms of DNA virus infection: entry and early events. Front. Biosci. 7:D390-D406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geraghty, R. J., C. R. Jogger, and P. G. Spear. 2000. Cellular expression of alphaherpesvirus gD interferes with entry of homologous and heterologous alphaherpesviruses by blocking access to a shared gD receptor. Virology 268:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geraghty, R. J., C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1998. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science 280:1618-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geurds, A. M., and A. S. Gurwood. 2002. Posner Schlossman syndrome. Case study. Optom. Today 63:38-39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herold, B. C., D. WuDunn, N. Soltys, and P. G. Spear. 1991. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 plays a principle role in the adsorption of virus to cells and in infectivity. J. Virol. 65:1090-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Immergluck, L. C., M. S. Domowicz, N. B. Schartz, and B. Herold. 1998. Viral and cellular requirements for entry of herpes simplex virus type 1 into primary neuronal cells. J. Gen. Virol. 79:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman, H. E., A. M. Azcuy, E. D. Varnell, G. D. Sloop, H. W. Thompson, and J. M. Hill. 2005. HSV-1 DNA in tears and saliva of normal adults. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46:241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krummenacher, C., I. Baribaud, M. Ponce de Leon, J. C. Whitbeck, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2000. Localization of a binding site for herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D on herpesvirus entry mediator C by using antireceptor monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 74:10863-10872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsters, S. A., T. M. Ayres, M. Skubatch, C. L. Gray, M. Rothe, and A. Ashkenazi. 1997. Herpesvirus entry mediator, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family, interacts with members of the TNFR-associated factor family and activates the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14029-14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauri, D. N., R. Ebner, R. I. Montgomery, K. D. Kochel, T. C. Cheung, G. L. Yu, S. Ruben, M. Murphy, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, P. G. Spear, and C. F. Ware. 1998. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity 8:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, J. M., C. A. Whetstone, L. J. Bello, W. C. Lawrence, and J. C. Whitebeck. 1995. Abortion in heifers inoculated with a thymidine kinase-negative recombinant of bovine herpesvirus 1. Am. J. Vet. Res. 56:870-874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mimura, T., S. Amano, M. Nagahara, T. Oshika, K. Tsushima, N. Nakanishi, and T. Tanino. 2002. Corneal endotheliitis and idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 133:699-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery, R. I., M. S. Warner, B. J. Lum, and P. G. Spear. 1996. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell 87:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohashi, Y., S. Yamamoto, K. Nishida, S. Okamoto, S. Kinoshita, K. Hayashi, and R. Manabe. 1991. Demonstration of herpes simplex virus DNA in idiopathic corneal endotheliopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 112:419-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry, C., S. Bell, T. Minson, and H. Browne. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H binds to alphavbeta3 integrins. J. Gen. Virol. 86:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Romero, P., A. Perez, A. Capul, R. Montgomery, and A. O. Fuller. 2005. Herpes simplex virus entry mediator associates in infected cells in a complex with viral proteins gD and at least gH. J. Virol. 79:4540-4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richart, S. M., S. A. Simpson, C. Krummenacher, J. C. Whitbeck, L. I. Pizer, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and C. L. Wilcox. 2003. Entry of herpes simplex virus type 1 into primary sensory neurons in vitro is mediated by nectin-1/HveC. J. Virol. 77:3307-3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritterband, D. C., and D. N. Friedberg. 1998. Virus infection of the eye. Rev. Med. Virol. 8:187-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scanlan, P. M., V. Tiwari, S. Bommireddy, and D. Shukla. 2003. Cellular expression of gH confers resistance to herpes simplex virus type-1 entry. Virology 312:14-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanlan, P. M., V. Tiwari, S. Bommireddy, and D. Shukla. 2005. Spinoculation of heparan sulfate deficient CHO 745 cells enhances herpes simplex type-1 entry, but does not abolish the need for essential glycoproteins involved in the virus fusion mechanism. J. Virol. Methods 128:104-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shukla, D., and P. G. Spear. 2001. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J. Clin. Investig. 108:503-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shukla, D., J. Liu, P. Blaiklock, N. W. Shworak, X. Bai, J. D. Esko, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, R. D. Rosenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spear, P. G. 2004. Herpes simplex virus: receptors and ligands for cell entry. Cell. Microbiol. 6:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spear, P. G., and R. Longnecker. 2003. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J. Virol. 77:10179-10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi, T., S. Ohtani, K. Miyata, N. Miyata, S. Shirato, and M. Mochizuki. 2002. A clinical evaluation of uveitis-associated secondary glaucoma. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 46:556-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terry-Allison, T., R. I. Montgomery, J. C. Whitbeck, R. Xu, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1998. HveA (herpesvirus entry mediator A), a coreceptor for herpes simplex virus entry, also participates in virus-induced cell fusion. J. Virol. 72:5802-5810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiwari, V., C. Clement, M. B. Duncan, J. Chen, J. Liu, and D. Shukla. 2004. A role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 85:805-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valyi-Nagy, T., V. Sheth, C. Clement, V. Tiwari, P. Scanlan, J. H. Kavouras, L. Leach, G. Guzman-Hartman, T. S. Dermody, and D. Shukla. 2004. Herpes simplex virus entry receptor nectin-1 is widely expressed in the murine eye. Curr. Eye Res. 29:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia, G., J. Chen, V. Tiwari, W. Ju, J. P. Li, A. Malmstrom, D. Shukla, and J. Liu. 2002. Heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase isoform 5 generates both an antithrombin-binding site and an entry receptor for herpes simplex virus, type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37912-37919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu, D., V. Tiwari, G. Xia, C. Clement, D. Shukla, and J. Liu. 2005. Characterization of heparan sulphate 3-O-sulphotransferase isoform 6 and its role in assisting the entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. Biochem. J. 385:451-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto, S., D. Pavan-Langston, R. Tada, R. Yamamoto, S. Kinoshita, K. Nishida, Y. Shimomura, and Y. Tano. 1995. Possible role of herpes simplex virus in the origin of Posner-Schlossman syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 119:796-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yue, B. Y. J. T., E. Higginbotham, and I. Chang. 1990. Ascorbic acid modulates the production of fibronectin and laminin by cells from an eye tissue-trabecular meshwork. Exp. Cell Res. 187:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng, X., M. Yamaguchi, T. Goto, S. Okamoto, and Y. Ohashi. 2000. Experimental corneal endotheliitis in rabbit. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41:377-385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]