Abstract

Purpose:

We identified 2 individuals with de novo variants in SREBF2 that disrupt a conserved site 1 protease (S1P) cleavage motif required for processing SREBP2 into its mature transcription factor. These individuals exhibit complex phenotypic manifestations that partially overlap with sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBP) pathway-related disease phenotypes, but SREBF2-related disease has not been previously reported. Thus, we set out to assess the effects of SREBF2 variants on SREBP pathway activation.

Methods:

We undertook ultrastructure and gene expression analyses using fibroblasts from an affected individual and utilized a fly model of lipid droplet (LD) formation to investigate the consequences of SREBF2 variants on SREBP pathway function.

Results:

We observed reduced LD formation, endoplasmic reticulum expansion, accumulation of aberrant lysosomes, and deficits in SREBP2 target gene expression in fibroblasts from an affected individual, indicating that the SREBF2 variant inhibits SREBP pathway activation. Using our fly model, we discovered that SREBF2 variants fail to induce LD production and act in a dominant-negative manner, which can be rescued by overexpression of S1P.

Conclusion:

Taken together, these data reveal a mechanism by which SREBF2 pathogenic variants that disrupt the S1P cleavage motif cause disease via dominant-negative antagonism of S1P, limiting the cleavage of S1P targets, including SREBP1 and SREBP2.

Keywords: Drosophila, Lipid droplet, S1P, SREBF1, SREBF2

Introduction

The control of lipid regulation by sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) is well characterized.1,2 SREBP proteins, encoded by 2 genes (SREBF1 [MIM#184756] and SREBF2 [MIM# 600481]), are transmembrane proteins embedded in an inactive state within the ER membrane. Limited sterol availability in the cell induces SREBPs to translocate to the Golgi, where they are proteolytically processed into active transcription factors. The Golgi-resident enzymes that cleave SREBPs are the site-1 and site-2 proteases (S1P and S2P) encoded by the MBTPS1 (MIM# 603355) and MBTPS2 (MIM# 300294) genes, respectively. Sequential cleavage of SREBPs by S1P and S2P releases the N-terminal transcription factor domain of the SREBPs and allows these peptides to translocate to the nucleus where they activate transcription of lipogenic genes.2–4 Thus, SREBPs are key regulators of fatty-acid synthesis during periods of limited lipid availability. Binding and cleavage of SREBP1 and SREBP2 by S1P occurs at a conserved tetrapeptide amino acid motif (arginine-any-any-leucine; RXXL) for which Arg519 is critically required.5 When this residue is mutated, S1P-mediated cleavage of SREBPs is abolished.6 Additionally, SREBF1 and SREBF2 can regulate each other’s gene expression through complex feedback and feedforward mechanisms mediated by micro-RNAs.4 Thus, diseases caused by a defect in one SREBP pathway member may result in phenotypes that overlap with diseases caused by other SREBP pathway members (see Table 1 for a summary of SREB-related diseases). There are numerous overlapping features between the affected individuals described herein and known SREBP-related diseases, arguing for common molecular mechanisms underlying these diseases.

Table 1.

SREBP pathway-associated diseases and phenotypic overlap

| Phenotypes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Gene | Eye | Bone | Hair | Skin | Other |

|

| ||||||

| HMD (MIM# 158310) | SREBF1 (MIM# 184756) | Cataracts, blindness, photophobia | Alopecia | Psoriatic lesions, keratosis, impaired cell junctions | Periorificial mucosal lesion, recurrent infection | |

| IFAP2 (MIM# 619016) | SREBF1 | Photophobia | Sparse or absent hair | Ichthyosis follicularis | ||

| SEDKF (MIM# 618392) | MBTPS1 (MIM# 603355) | Cataracts | Skeletal anomalies, short stature | |||

| IFAP1 (MIM# 308205) | MBTPS2 (MIM# 300294) | Photophobia | Short stature | Sparse or absent hair | Ichthyosis follicularis | Seizures |

| OS (X-linked; MIM# 300918) | MBPTS2 | Digit constriction | Alopecia | Periorificial keratotic plaques | ||

| Osteogenesis imperfecta Type XIX (MIM# 301014) | MBTPS2 | Osteopenia, fractures, short stature, scoliosis | ||||

| KFSDX (MIM# 308800) | MBTPS2 | Photophobia, corneal dystrophy | Progressive cicatricial alopecia | Widespread keratosis pilaris | ||

| Individual 1 |

SREBF2 p.(R519H) |

Photophobia, cranial nerve palsy, ocular motor apraxia, optic nerve hypoplasia, strabismus, myopia | Short stature | Scarring alopecia | Scaly skin, recurrent skin infection, plantar keratitis, abnormal nails | Global impairment, dilated ventricles, periventricular nodular heterotopias, leukomalacia, hippocampal atrophy, small cerebellum, seizures |

| Individual 2 |

SREBF2 p.R519G) |

Optic nerve and chiasm atrophy | Chondrodysplasia punctata (resolved), rhizomelic short stature with an epimetaphyseal dysplasia, unilateral postaxial polydactyly | Alopecia | Scaly and thick skin, skin lesions and callouses in areas of friction | Global impairment, dilated ventricles, subependymal heterotopia, polymicrogyria |

Pathogenic variants in genes encoding members of the SREBP pathway cause various diseases with substantial overlap in phenotypes observed, including in individuals with hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia (HMD), ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia, and photophobia (IFAP1&2), Olmstead syndrome (OS), and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalyans (KFSD). Prior to this study, human disease had not been associated with variations in the SREBF2 gene. This work delineates the role of SREBF2 p.(Arg519) variants that cause a previously unreported disease mediated by inhibition of the protease S1P, which should be known as SREBF2-related dermatologic, neurologic, and skeletal defects.

Pathogenic variants in the SREBF1 gene are associated with 2 conditions: hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia (HMD; MIM# 158310)7,8 and ichthyosis follicularis with atrichia and photophobia 2 (IFAP2; MIM# 619016).9 Individuals with IFAP2 may present with mucoepithelial defects, non-scarring alopecia, psoriasiform lesions, follicular keratosis, cataracts, blindness, and photophobia. Lipid and RNA expression analyses in skin of individuals with IFAP not only indicate reduced lipid levels but also reduced expression of lipoprotein receptors and keratin genes, thus contributing to the skin hyperkeratosis and hypotrichosis phenotypes observed.9 Ectopic lipid accumulations also lead to skin and hair defects, indicating that a precise regulation of lipogenesis is needed to maintain proper hair and skin homeostasis.10,11 Pathogenic variants in SREBF1 that cause both HMD and IFAP likely affect S1P-mediated cleavage of SREBP1, suggesting common molecular underpinnings of both diseases.8,12,13

Loss-of-function variants in MBTPS1 were identified in 1 individual with autosomal recessive spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia Kondo-Fu type (SEDKF; MIM# 618392), which was associated with significant growth restriction, skeletal dysmorphism, reduced bone mineral density, and elevated blood levels of lysosomal enzymes.14 Notably, defects in SREBP activity are associated with defects in bone morphogenesis as demonstrated by a mouse model in which loss of S1P caused endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention of collagen leading to bone defects.15–17 Pathogenic variants in MTBPS2 are associated with IFAP1 syndrome with or without BRESHECK syndrome (brain anomalies, retardation, ectodermal dysplasia, skeletal malformaitons, Hirschsprung disease, ear/eye anomalies, cleft palate/chryptochordism, and kidney displasia/hypoplasia; MIM# 308205),18 Olmstead syndrome (MIM# 300918),19 osteogenesis imperfecta type XIX (MIM# 301014),20 and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans X-linked (MIM# 308800).21 Although there are no human diseases currently associated with variants in the SREBF2 gene, the shared molecular functions of SREBP1 and SREBP2, together with the shared regulation of the 2 SREBP proteins by S1P and S2P, suggest that variants that disrupt the cleavage of SREBP2 may result in similar clinical manifestations as those associated with SREBP-related diseases.

Materials and Methods

Subject recruitment and analysis

Individual 1 was enrolled into the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) in an effort to identify an underlying genetic cause for the clinical phenotype. The individual and the unaffected parents were consented in accordance with standard UDN manual of operations22 and the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine.23–25 Individual 2 was evaluated by the skeletal dysplasia team at Nemours Children’s Hospital-Delaware and enrolled into a research study approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Exome sequencing was performed on samples from whole blood (individual 1 and parents of individual 1 and 2) or fibroblasts (individual 2), and potential pathogenic variants were identified and prioritized based on known or predicted gene function in relation to phenotypes, allele frequencies in large genomic databases (gnomAD),23 and inheritance pattern. All variants listed herein comply with Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) nomenclature based on the GRCh38 human genome reference and have been verified using Variant Validator24 (Table 2).26 SREBF2 transcript sequence utilized for our studies is listed in GenBank under the accession number NM_004599.4 (NC_000022.11). Allele frequencies and pLI scores were obtained using gnomAD23 and genetic deficiencies in the human population were assessed using the Database of Genomic Variants.25

Table 2.

SREBF2 variants identified in this study

| Gene | Variant Name (as used in this study) | Genomic Change | Transcript Change | Protein Change | Classification | Pathogenicity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| SREBF2 | R519H | NC_000022.11:g.41877398G>A | NM_004599.4:c.1556G>A | NP_004590.2:p.(Arg519His) | Pathogenic | PS2 and PS3 |

| SREBF2 | R519G | NC_000022.11:g.41877397C>G | NM_004599.4:c.1555C>G | NP_004590.2:p.(Arg519Gly) | Pathogenic | PS2 and PS3 |

We identified de novo variants in SREBF2 from 2 individuals with dermatological, neurological, and skeletal phenotypes. Both variants are characterized as pathogenic based on the American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines,26 having ≥2 strong criteria for pathogenicity (PS2 and PS3 scores).

Drosophila

Fly stocks were maintained at 22 °C on standard molasses lab food with constant light. Newly eclosed flies of the desired genotypes were housed in a 29 °C incubator until appropriately aged. Stocks used in this work were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (#51635 [y1 w*; P{nSyb-GAL4.S}3], #38396 [w*; P{UAS-SREBP.K} 2/CyO; SREBP189/TM6B, Tb1]) or generated using transgenesis procedures standardized in the lab (UAS-empty, UAS-SREBF2ref or R519H or R519G, and UAS-MBTPS1ref).27–29 In brief, transgenic fly lines were generated by first cloning human cDNAs into the pGW-attB-HA destination vector using gateway cloning (LR Clonase II, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Variants were generated before gateway cloning using Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (New England Biolabs) using primers generated from the NEBase Changer web service (New England Biolabs). All mutagenesis and cloning steps were verified by full Sanger sequencing analysis at the Baylor College of Medicine Precision Environmental Health DNA Sequencing Core. Transgenic vectors were injected into ywΦC31 integrase-expressing flies using VK37 (2nd chromosome) or VK33 (3rd chromosome) docking sites30 with red-eyed transgenic animals isolated, mated, and maintained as stocks.

Lipid droplet (LD) assays

The fly photoreceptor neuronal axons in the eye are surrounded by secondary pigment glia required for proper neuronal cell maintenance. We have previously demonstrated that overexpression of the fly SREBP protein in neurons induces a lipogenic pathway that initiates the export of newly synthesized lipids to extracellular apolipoproteins, which are endocytosed by glia and used to produce LDs.31 Because the fly eye has a stereotypical arrangement of neurons and glia, we can readily distinguish LDs in neurons from those in glia without the use of cell-type markers. Thus, LDs can be observed by staining retinas with the neutral lipid dye, Nile Red. To this end, 1- or 2-day-old flies were anesthetized on CO2 and briefly dipped in 100% ethanol before being submerged into PBS for dissection. Fly heads were isolated and incubated overnight in 37% form-aldehyde at 4 °C, shaking. The following day, retinas were manually dissected and dissociated from the cuticle using tungsten needles. Isolated retinas were washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in PBS and submerged in 2 mL PBS containing 2 μL of stock (1 mg/mL in DMSO) Nile Red (Millipore Sigma) solution and incubated for 20 minutes, shaking. Retinas were then washed 5 times (5 minutes each) with PBS and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs) mounting media on glass slides. Retinal optical sections (1 μM thick) were captured using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using a 63× objective with 3× zoom. Individual ommatidia can be delineated by the presence of diffuse Nile Red staining in the cellular membranes. LDs were manually counted in FIJI and distinguished from membrane and background staining by (1) the presence of concentrated, punctal Nile Red accumulation above background, as visualized in high contrast images, and (2) punctal size (≥0.5 μM in diameter). LD number was graphed using Prism GraphPad. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction for multiple tests were used on all LD quantification analyses using GraphPad.

Neurological assays

Flies of the desired genotype were collected into fresh food vials and stored at 29 degrees in a light controlled 12-hour light/dark cycle with food vials changed every 3 to 5 days until the flies reached the age indicated. Climbing assays were conducted by transferring the properly aged flies to an empty vial and allowing the animals to acclimatize for 5 minutes. Vials were then tapped 5 to 7 times and video recordings of a 30-second recovery phase were captured for analysis. Individual flies were manually tracked, and the time taken for each fly to climb 5 cM was recorded and graphed. Bang sensitivity assays were conducted by transferring the properly aged flies to an empty vial and allowing them to acclimatize for 5 minutes. Vials were then vortexed for 30 seconds, and video recordings of a 30 second recovery phase were captured for analysis. Individual flies were manually tracked, and the time taken for each fly to right itself and begin climbing was recorded. Electroretinogram recordings were obtained from live flies immobilized on glass microscope slides after animals were aged as indicated. Glass pipettes were filled with 100 mM NaCl and placed over wire electrodes as done previously to obtain electrical recordings.32 The reference electrode was placed on the thorax and the recording electrode was placed in the center of the eye. Flies were kept in the dark for 1 minute to acclimatize followed by exposure to 1-second light pulses from a halogen lamp. Recordings of the response to light (indicating synaptic transmission), as well as the amplitude of photoreceptor membrane depolarization, were recorded and quantified using LabChart 8 (AD Instruments) and exported for analysis. Data analysis was performed using Prism GraphPad using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction for multiple tests.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Fibroblasts obtained from individual 1 and the unaffected parents (controls) were obtained from the UDN33 and cultured for ≤3 passages in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco) supplementation. Cells were grown in culture dishes at 37 °C and 5% CO2 to 80% confluence and media was exchanged with Karnovsky’s fixative solution (4% PFA, 2% glutaraldehyde and 0.1M sodium cacodylate at pH 7.4). Fly retinal samples (aged 1–2 days post eclosion) for TEM analysis were prepared as above (except the fixative was made at pH 7.2) with flies being immobilized in fixative and head+thorax isolated. All samples were incubated in fixative at 4 °C for 48 hours. After fixation, samples were incubated in 1% Osmium Tetroxide for 35 to 40 minutes and dehydrated in graded ethanol and propylene oxide manually (fibroblasts) or using a Leica EM TP Automated Tissue Processor (flies) at room temperature. Finally, samples were embedded in Embed-812 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 72 hours, until cured. Sample sections (50 nM thick) were obtained using a Leica UC7 microtome and stained with 1% uranyl acetate and 2.5% lead citrate and mounted on microscopy grids. Sample images were captured on a JEOL JEM1010 transmission electron microscope using an AMT XR-16 midmount 16-megapixel camera. LDs and inclusions were manually counted, and ER size was measured using FIJI, and all results were graphed using Prism GraphPad. Two-tailed, paired t tests for fibroblast quantifications and ordinary one-way ANOVA for fly inclusions were calculated using GraphPad.

Gene expression analysis

Primary skin fibroblasts were cultured in MEM-alpha (Fisher Scientific) in 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific) and 1% antibiotic (Gibco). Cells were rinsed with PBS (ThermoFisher) and cultured overnight in MEM-alpha supplemented with 10% FBS or with 10% lipoprotein-depleted FBS (Kelen Biomedical) and antibiotic. The following day, cells were rinsed with PBS and RNA extracted using RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed using the high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosciences). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) and gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table 1). Target gene expression was normalized to Glycer-aldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and expression values were expressed as the fold difference in expression between the lipid-depleted and complete media conditions. Data represent 3 replicates from 2 experiments performed on different days. Statistically significant differences for each gene were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison correction after log transformation in the Prism GraphPad software.

Results

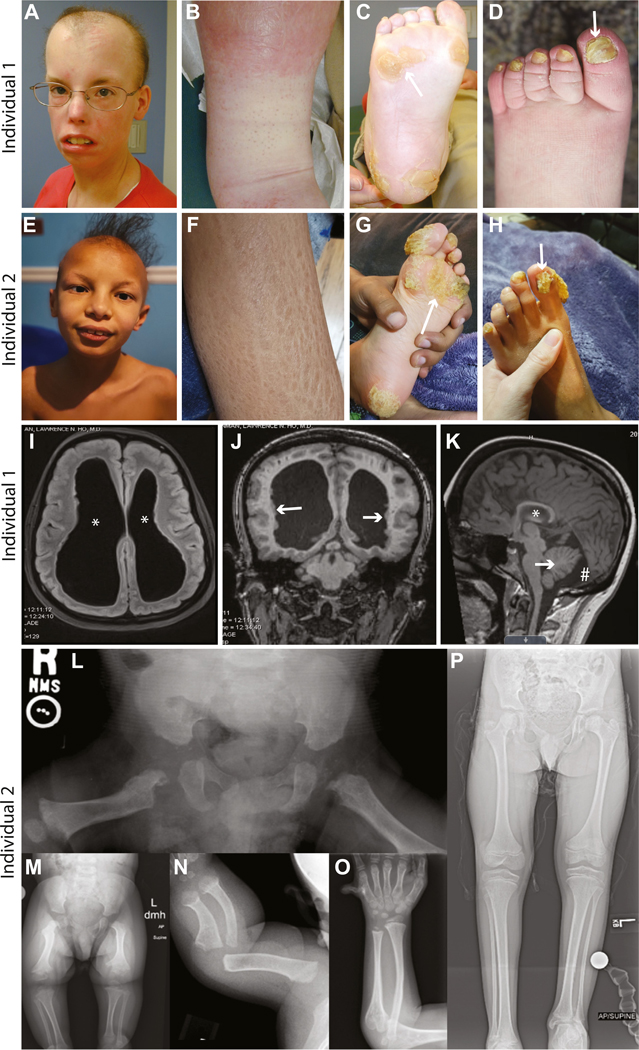

We identified 2 individuals with common disease phenotypes (Table 1 and supplemental clinical description), both with variants in SREBF2 at p.(Arg519), a key residue required for S1P-mediated cleavage of SREBP2.5 Individual 1 was suspected to have an underlying genetic cause for hair, nail, skin, bone, and neurological abnormalities (Figure 1A-D and I-K), and clinical genome sequencing (GS) was performed on whole-blood DNA samples from individual 1 and unaffected parents. The clinical GS analysis was nondiagnostic, but research reanalysis of the GS data identified a de novo variant in SREBF2, NC_000022.11g.41877397C>G NM_004599.4:c.1556G>A p.(Arg519His), which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This variant is hereby referred to as R519H. No other variants consistent with phenotypic features were identified. Individual 2 has phenotypic features similar to individual 1 (Figure 1E-H and L-P) and clinical exome sequencing was performed on fibroblasts from the individual and blood from the unaffected parents. Sequence analysis initially identified a maternally inherited heterozygous variant in FLG (MIM# 135940), NC_000001.11:g. 152313385G>A NM_002016.2 c.1501C>T p.(Arg501Ter), which may contribute in part to the scaly skin phenotype. This variant, when homozygous or in trans to a c.2282_2286del variant, is associated with ichthyosis vulgaris (MIM# 146700). However, the literature indicates that this pathogenic variant in heterozygous individuals causes, at most, a very mild epidermal phenotype.34 The individual’s mother is also heterozygous for this variant and has dry skin but no other overlapping phenotypic features with individual 2, indicating that this variant alone is not the genetic cause of the complex phenotype observed. A subsequent reanalysis of the exome data under the University of Texas Southwestern research protocol identified a de novo SREBF2 variant (c.1555C>G p.Arg519Gly). This variant is hereby referred to as R519G. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the R519G variant in blood obtained from individual 2 and found no variants of SREBF2 upon sequencing buccal cells obtained from the unaffected parents.

Figure 1. Individuals harboring variants in SREBF2 p.(Arg519) exhibit dermatological, neurological, skeletal, and other abnormalities.

Individual 1 p.(Arg519His) and individual 2 p.(Arg519Gly) share phenotypes including scarring alopecia (A and E), scaly skin (B and F), hyperkeratosis (C and G), and abnormal nails (D and H). Individual 1 also has dilated cerebral ventricles (I, asterisks), periventricular nodular heterotopias (J, arrows), leukomalacia, hippocampal atrophy (K, asterisk), a mega-cisterna magna (K, pound symbol), and a small cerebellum (K, arrow). Short stature and an initial suggestion of metaphyseal dysplasia on a bone survey as a child that resolved with age (see supplemental clinical description) was also observed. Individual 2 also presents with bilateral enlargement of the lateral cerebral ventricles and other neurological findings (see supplemental clinical description). Radiographs of individual 2 demonstrate skeletal dysplasia. Anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis taken at 5 months shows right to left asymmetry of the proximal femur with chondrodysplasia punctata present in the hip region bilaterally (L). AP radiograph of the bilateral lower extremities taken at 22 months also demonstrates right to left asymmetry with metaphyseal changes noted throughout and absent mineralization of the capital femoral epiphyses (M). Left forearm taken at 5 months and 6 years 11 months, respectively (N and O), show metaphyseal widening with broad diaphysis, and bowing present in the younger image. The metaphyseal widening remains in the older image, but the diaphyseal changes appear resolved though slight bowing remains. Unilateral postaxial polydactyly was also present (O). Supine AP image of the lower extremity taken at 10 years 11 months (P), noting significant right to left asymmetry with leg length discrepancy.

Although the cutaneous findings observed in the affected individuals are consistent with IFAP, additional inconsistent findings together with the fact that variants in SREBF2 are not known to be associated with a human disease led us to investigate further. To probe for potential mechanisms of disease and to gain a better insight into the cellular features of the disorder, we cultured skin fibroblasts from individual 1 and the unaffected parents and subjected them to ultrastructure analysis by TEM. This analysis identified 3 striking phenotypes in the cells from individual 1 compared with the control (father) cells: (1) a statistically significant reduction in LD accumulation (Figure 2A-C and E), (2) a severe expansion of the ER (Figure 2C and F), and (3) the presence of lamellar, electron-dense inclusion bodies reminiscent of defective lysosomes (Figure 2C, D, and G). We observed no distinguishable differences in other cellular features, such as mitochondria and actin fibrils, in cells from the affected individual compared with controls. The abnormalities observed are indicative of defects in LD formation due to defects in SREBP signaling,31,35 ER stress response activation,36,37 and lysosomal function.38 The SREBP pathway has been well characterized in its role as an inducer of lipid synthesis in human cells and in animal models. Murine models of SREBF1 loss induced compensatory upregulation of SREBF239 and, similarly, loss of SREBF2 induced compensatory upregulation of SREBF1,40 implicating a feedback mechanism that becomes activated in the cell upon the complete loss of one of the SREBP paralogs. In the case of SREBF2 mouse models, complete knockout of SREBF2 caused embryonic lethality with only 1 animal living beyond birth.40 This animal exhibited phenotypes notably similar to those observed in the 2 affected individuals with SREBF2 variants described here, including alopecia, attenuated growth, and reduced adipose tissue stores.40 However, it is likely that the mouse model represents a more severe reduction in SREBP2 function than is exhibited in the described individuals given that it is a complete loss of the gene. Thus, although we observe deficits in lipogenic outputs in SREBF2 variant cells compared with the abundant LD accumulation in fibroblasts from the unaffected parents, the SREBF2 variants likely do not cause a complete loss of SREBP2 function, which would be expected to result in embryonic lethality.

Figure 2. Fibroblasts from individual 1 have limited lipid droplet (LD) accumulation, exhibit expanded endoplasmic reticula (ER), and accumulate lamellar inclusion bodies.

Fibroblasts from the unaffected father (A and B) and from Individual 1 (C and D) were subjected to transmission electron tomography analysis. LD accumulation is evident in the father’s fibroblasts (A and B, labeled with black arrowheads) but is severely limited in the cells from Individual 1 (C, quantified in E). Fibroblasts from individual 1 exhibit increased ER area compared with cells from the father (A and C, white arrowheads, quantified in F) and accumulate electron-dense lamellar inclusion bodies (C, white arrows; high magnification image in D), which are absent in the cells from the father (quantified in G). All quantifications are graphed as mean ± SEM, Welch’s t test, *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

Given the defect in LD formation in fibroblasts, we set out to examine the role of the SREBF2 variants on lipogenesis using an animal model of LD formation. SREBPs and the enzymes that proteolytically activate them are highly conserved, including in insects.3,41,42 The single fly homolog of both SREBF1 and SREBF2, named SREBP, has also been characterized in its conserved role in lipid production.3,43 SREBP is expressed in fly fat body (homologous to vertebrate liver and adipose tissue), intestine, and neurons among other tissues.44 Complete loss of fly SREBP causes lethality during larval development and impedes the activation of fatty acid synthetic genes that are targets of the SREBP pathway activation, consistent with its role in lipogenesis and demonstrating the conservation of the pathway from invertebrates to vertebrates. The fly eye may be particularly useful to probe the function of SREBF2 because it is an established model for glial LD formation when the fly ortholog, SREBP, is overexpressed in eye neurons.31,32,35 In flies, as in mammals, SREBP activates fatty-acid synthesis and is cleaved by S1P and S2P enzymes.43 Given this functional conservation and the tools available for investigation in flies, we set out to model the human SREBF2 variants using a fly model. We found that ubiquitous or tissue-specific overexpression of SREBF2 or variants of SREBF2 had no effect on animal viability or morphology in young flies (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). In aged animals, however, expression of either SREBF2 variant, but not the nonvariant SREBF2, using a pan-neuronal driver (Nsyb-GAL4) caused locomotor deficits (Figure 3A-D), as well as neurotransmission defects (Figure 3E and F) indicating that the SREBF2 variants have a deleterious effect. We next sought to assess the effects of SREBF2 variants on LD formation and show that overexpression of the fly homolog of SREBF2, SREBP, in photoreceptor neurons induces lipid droplet accumulation in glial cells that surround the photoreceptors (Figure 4A and B), consistent with previous reports.31,32 Similarly, overexpression of the nonvariant human SREBF2 transcript elicited a strong glial LD accumulation phenotype compared with an empty vector negative control expressed using the same neuronal driver (Figure 4C and D). However, neuronal expression of SREBF2 transcripts encoding variants found in individuals 1 and 2 failed to induce glial LD accumulation, providing an additional line of evidence that these SREBF2 variants are loss-of-function alleles (Figure 4E-G).

Figure 3. Overexpression of SREBF2R519H or SREBF2R519G induces age-dependent neurological deficits in fly models.

Assessment of neurological function via climbing assay (A) of aged flies expressing SREBF2R519H and SREBF2R519G compared with nonvariant SREBF2 transcripts show an age-dependent increase in the time to climb, indicative of nervous system deficits (B). Neuronal function was also assessed using a bang sensitivity assay (C) showing an age-dependent increase in the time for variant-expressing flies to right themselves (D), further indicating nervous system defects with age. Finally, assessment of neurotransmission capacity via electroretinogram (ERG) was performed on flies expressing variant transcripts of SREBF2, in which a probe placed on the fly eye was used to measure neuronal response to light flashes (E). Synaptic transmission from the photoreceptors to the optic lobe is measured by the on and off transient phases and photoreceptor function is measured by the amplitude phase of the ERG recording. Age-dependent defects in neuronal function were observed in the on and off transients (F and G), indicating impaired synaptic transmission to the central brain in aged animals. All quantifications are graphed as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 4. Fly SREBP and human SREBF2 overexpression induces glial lipid droplet formation, but SREBF2 variant overexpression fails to do so.

The fly compound eye is comprised of several hundred ommatidia in which photoreceptor neurons are surrounded by glia (A). Overexpression of fly SREBP in neurons induces glial LD formation (via Nile Red staining) as previously reported (B, solid white line outlines ommatidium, dotted white line outlines photoreceptor cells), but an empty control vector does not have this effect (C). Overexpression of nonvariant human SREBF2 in neurons induces glial LD formation to similar levels as fly SREBP (D). Neuronal overexpression of either the SREBF2R519H variant (E) or the SREBF2R519G variant (F) fails to induce LD formation, suggesting that the variants are loss-of-function alleles. Quantification of LDs from all genotypes tested is graphed in (G, n = 10 animals per genotype, aged 1–2 days post eclosion) as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction, ****P < .0001.

However, the low haploinsufficiency score for the SREBF2 gene (pLI score = 0.00)23 together with the presence of 3 healthy individuals in the Database of Genomic Variants with haploinsufficiency of SREBF225,45,46 suggest that a loss-of-function model is unlikely sufficient to explain the observed disease phenotypes in the affected individuals. Furthermore, DOMINO, a machine learning algorithm used to predict genes that likely cause dominant disease, predicts that SREBF2 variants cause autosomal dominant disease at a probability of 0.981, placing it in the class of “very likely dominant” genes.47 We therefore tested whether the SREBP2 variants have dominant-negative effects by coexpressing nonvariant and variant SREBF2 transcripts and measuring glial LD accumulation. Expression of nonvariant SREBF2 together with an empty control vector resulted in robust glial LD accumulation consistent with our previous results; however, coexpression of nonvariant SREBF2 together with the SREBF2 variants significantly disrupted glial LD accumulation (Figure 5A-C and G). These data provide evidence that the disease-associated SREBF2 variants are dominant negative. We also subjected these coexpression/dominant-negative fly models to ultrastructural analysis by TEM, which revealed the presence of lamellar inclusions (Supplemental Figure 2C-H) similar to those observed in the fibroblasts from individual 1.

Figure 5. SREBF2 variants act in a dominant-negative manner by limiting the S1P enzyme pool required for SREBP protein activation.

Human SREBF2 overexpression in the fly photoreceptor neurons induces glial LD formation as visualized by Nile Red staining (A). However, co-overexpression of SREBF2R519H (B) or SREBF2R519G (C) with nonvariant SREBF2 severely limits glial LD formation, indicating that these variants act in a dominant-negative manner. Concomitant expression of the S1P encoding gene, MBTPS1, with the nonvariant SREBF2 (D) has no effect on LD formation, but expression together with SREBF2R519H (E) or SREBF2R519G (F) variants rescues the loss of glial LD production caused by the variants, revealing that the variants limit the function of S1P. Quantification of LDs from all genotypes tested is graphed in (G, n = 10 animals per genotype, aged 1–2 days post eclosion) as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Because the SREBF2 variants alter the S1P cleavage motif, we hypothesized that S1P binds to the variant SREBP2 but does not cleave it, leading to a depletion of the active S1P pool and limiting the processing of the nonvariant SREBP2 and other S1P target proteins. Therefore, we tested whether overexpression of human MBTPS1 (to restore the S1P pool) could rescue the LD accumulation defect caused by the SREBF2 variants. We generated a fly line expressing a nonvariant UAS-MBTPS1 and introduced it into the background of dominant-negative fly lines, thus expressing MBTPS1 together with variant and nonvariant SREBF2 transcripts. Expression of MBTPS1 rescued glial LD accumulation induced by SREBF2 variants (Figure 5D-G), providing evidence that the S1P pool is limited by the dominant-negative, disease-associated SREBP2 variant protein. Although the distribution of the LDs in these animals is somewhat different from what we have observed in other conditions, the numbers of LDs were similar to conditions of fly SREBP or human SREBF2 overexpression. The distribution differences might be caused by the pleiotropic effects of S1P function, affecting multiple pathways beyond SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Regardless, the mechanism of S1P inhibition by SREBF2 variants suggests that the SREBF2-related disease phenotypes may result from a combination of defects due to the loss of SREBP2 function together with the disruption of cleavage of SREBP1 and other targets of S1P.

We next sought to understand whether the SREBF2 variants, and the deficit in S1P function that they cause, affect gene regulation of the SREBP pathway members and transcriptional targets. To this end, fibroblasts from individual 1 and unaffected parents were subjected to gene expression analysis by quantitative RT-PCR. We compared gene expression profiles for some of the targets of the SREBP transcription factors, including genes important for steroidogenesis and fatty acid synthesis (Figure 6A). We grew cells in sterol-depleted media (to induce SREBP-response gene expression) and compared their response with the response from cells grown in complete media (no SREBP-response activation). Using these 2 populations of cells, we examined the mRNA expression of 3 steroidogenic genes, HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol production), INSIG1 (insulin-induced gene 1, an ER-localized protein that mediates trafficking of SREBP2 to the Golgi), and LDLR (low-density lipoprotein receptor, mediating the uptake of low-density lipoproteins).2 We also examined the expression of 3 fatty-acid synthetic genes SREBF1, FASN (fatty acid synthase, a long-chain fatty acid synthesis enzyme), and SCD (stearoyl-CoA desaturase, an ER-bound fatty acid biosynthetic enzyme) in the same cell populations (Figure 6B). Our analysis showed that, in the cells from the unaffected parents, expression of all 6 genes was elevated in the sterol-depleted conditions compared with cells in the complete media conditions, but no such transcriptional response was observed in the cells from individual 1 (Figure 6C and D). Additionally, we found no significant change in the expression of MBTPS1 or MBTPS2 in the cells from individual 1 or the parents, suggesting that these genes are not regulated by sterols or by the SREBP pathway (Figure 6E). These data indicate that SREBF2 variants induce loss of SREBP pathway activation consistent with our observations using the fly models. Additionally, these data indicate that the previously reported compensatory mechanism, in which the expression of 1 mouse SREBP paralog is upregulated upon loss of the other, is either not conserved in humans or is not activated by the SREBF2 R519 variants. Thus, the SREBF2 variants cause a dominant-negative effect on SREBP pathway activation that cannot be compensated by SREBP1.

Figure 6. Fibroblast gene expression analysis reveals defects in SREBP pathway activity caused by SREBF2 variants.

The activation of gene expression by SREBP proteins requires the cleavage of full-length SREBP proteins by S1P and S2P followed by dimerization of the SREBP transcription factor and its translocation to the nucleus (A). The cleaved, mature SREBP transcription factor recognizes and promotes the expression of genes containing Sterol Regulatory Elements (SRE) in their promoters, including genes involved in steroidogenesis and fatty acid production (B). Fibroblasts from individual 1 and unaffected parents were analyzed for gene expression of key SREBP-regulated genes via quantitative RT-PCR. We observed significant reductions in RNA from individual 1 in the SREBP-regulated genes: SREBF1, SREBF2, HMGCR, FASN, SCD, INSIG1, and LDLR (C and D) but no statistically significant changes in the genes encoding the SREBP cleavage enzymes, S1P (MBTPS1) and S2P (MBTPS2) (E). Quantifications (n = 3 replicates per genotype) are graphed as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison correction after log transformation. ns, no statistically significant difference; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Discussion

Our data implicate a defect in SREBP signaling caused by variants in SREBF2 that limit the available pool of S1P enzyme. Because both SREBF2 variants described here alter the RXXL cleavage motif recognized by S1P, we postulate that the variants inhibit cleavage of SREBP2, potentially resulting in a prolonged or aberrant interaction with S1P or that the variants cause a conformational change in the S1P enzyme, resulting in a conformer incapable of cleavage activity. In any case, our data suggest that the functional pool of S1P proteins in the cells is limited by SREBF2 p.Arg519 variants, leading to inhibited cleavage of S1P targets (Figure 7), including SREBP1, nonvariant SREBP2, and others. Hence, we propose that the phenotypes associated with the SREBF2 p.Arg519 variants are the result of impaired S1P function, thus causing disease beyond a simple loss of SREBP2 function alone. Variants that affect the RXXL motif in SREBF1 cause autosomal dominant IFAP,9 and our data suggest that the phenotypic similarity between IFAP and the 2 individuals described herein is likely explained by a reduction in S1P function in both conditions (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 7. Model diagram of proposed mechanism of disease-associated variants in SREBF2.

The cell maintains a pool of S1P cleavage enzyme capable of recognizing the RXXL motif in SREBP proteins for proper cleavage into its mature transcription factor. After cleavage, S1P dissociates from SREBP proteins and S1P can be recycled back into the available pool for additional cleavage of SREBP and other protein targets (A). Our data indicate that SREBF2 p.(Arg519) variants inhibit S1P-mediated cleavage of SREBP2 for transcription factor generation. We propose that this failed cleavage may cause an S1P-SREBP2 interaction to persist, or alter the ability of S1P to cleave SREBP2, subsequently causing a failure in S1P pool regeneration for cleavage of SREBP1, nonvariant SREBP2, and other targets of S1P (B). Thus, dominant-negative variants in SREBF2 may inhibit the proper production of any protein product requiring S1P, causing a broader array of symptoms than would be caused by loss of SREBP2 function alone.

The function of S1P as a cleavage enzyme is well characterized, and the effects of S1P deficiency are likely pleiotropic given the array of molecules that it is known to cleave. For example, the ER stress-induced transcription factor ATF6 is cleaved by S1P in a similar manner to SREBP proteins. Upon ER stress induction, ATF6 translocates from the ER to the Golgi and undergoes sequential cleavage by S1P and S2P, releasing a mature transcription factor that activates ER stress response genes.48 In the absence of an adequate pool of S1P, we postulate that the ATF6 transcription factor would not become activated to initiate transcription of its downstream effectors. This would lead to a failed ER stress response, which is consistent with the observations in the fibroblasts from individual 1, which demonstrate a vastly expanded ER (Figure 2). Moreover, S1P has also been implicated in autophagy,49 and its loss impairs lysosomal trafficking of N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase subunits alpha and beta (GNPTAB), a gene associated with a lysosomal storage disease, mucolipidosis II50 (MIM#252500). As in the case of ATF6, this function of S1P in regulating GNPTAB and other proteins important for proper lysosome function is consistent with the presence of the aberrant lysosomal phenotypes observed in cells from individual 1 (Figure 2), as well as the aberrant lamellar inclusions observed in the fly models (Supplemental Figure 2). It is noteworthy that the inclusion bodies observed in the flies are reminiscent of aberrant lysosomal engulfment of LDs and are often in close proximity to mitochondria, suggesting a cellular mechanism aimed at catabolizing the engulfed contents. Because these flies were imaged at a young age (1–2 days after eclosion), the inclusions may represent an early event in the disease process and that the lamellar inclusions may increase in lamellae number over time as more ineffectual engulfment attempts are made by the cell. Further, ER stress and lysosomal function have been linked by authors of several studies that demonstrate that the ER stress induces alterations in lysosome function including changes in acidification, size, position, and membrane permeability.51–56 Failure to initiate an ER stress response has also been associated with several metabolic disorders,57 and defective lysosomal function has been associated with numerous diseases, including Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and others.58 We predict that the expression of variant SREBF2 antagonizes the function of fly S1P and, given the pleiotropic role of S1P in cell function, may confer phenotypes beyond those examined in this study, which warrants further investigation. Additionally, nervous system assessment in the fly models of SREBF2 variant transcript overexpression shows that nervous system deficits occur in an age-dependent manner (Figure 3), suggesting that dominant-negative SREBF2 variants may progressively induce cellular deficiencies in S1P function over time.

Our data indicate that S1P deficiency caused by dominant-negative SREBF2 variants contributes to limited SREBP pathway activation, failure to initiate an ER stress response, and lysosomal dysfunction (Figure 4). The data from our fly models demonstrate that an increased availability of S1P could alleviate the effects of the SREBF2 variants (Figure 5). Thus, therapeutic intervention for this disease should be aimed at reducing the expression of variant SREBF2 transcripts or at boosting the expression of MBTPS1 or the function of S1P. Although the strategies aimed at promoting S1P function are challenging, a strategy targeting the variant SREBF2 transcript could be considered using an anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASO) method that specifically targets the variant isoform for degradation while leaving the nonvariant isoform intact. Unfortunately, ASO-based strategies can be costly and often require regular maintenance doses.59,60 Although an agonist of SREBP2 and/or S1P could prove effective, no such compounds currently exist (inhibitors of SREBP261 and MBTPS162 have been developed but would not be predicted as therapeutically effective for this disease based on these data).

In summary, we identified 2 individuals with variants in SREBF2 that disrupt the conserved RXXL cleavage motif required for proper processing of the mature SREBP2 transcription factor. We propose a mechanism by which variants of the SREBP2 RXXL motif cause a decrease in the functional pool of S1P proteins required for SREBP activation, ER stress response activation, and lysosome function. The SREBF2 variants described herein should be classified as causing SREBF2-related dermatologic, neurologic, and skeletal defects based on the dyadic approach to delineating diagnostic entitites.63 Using the semi-quantitative assessment established by Strande et al,64 we argue that there is strong supporting evidence for a gene-disease association for these SREBF2 variants based on the cellular- and animal-model-based work described herein. Our data argue that the pathogenic effects of variants that limit S1P availability may be a common feature in the pathogenesis of the disease manifestations of other SREBP-related disorders, such as IFAP, which warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2024.101174) contains supplemental material, which is available to authorized users.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the individuals and parents for their participation in this study and for providing phenotypic images. The authors thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock center for providing fly lines necessary for this work, the Gene Disruption Project team for performing the injections required for making the transgenic fly lines, and the Precision Environmental Health DNA Sequencing Core at Baylor College of Medicine for Sanger sequencing. Confocal imaging was performed in the Neurovisualization Core of the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center, supported by the National Institutes of Health under award U54D083092.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the NIH: NINDS U54 NS093793, OD R24 OD022005, NIA R01 AG073260, NIA U01 AG072439, NHGRI U01 HG010215, and U01 NS13454. M.J.M. was supported by the Brain Disorders and Development Fellowship Training Grant from the NIH under award T32 NS043124–19.

Footnotes

Ethics Declaration

Individual recruitment into the study was done in accordance with the institutional review board at Baylor College of Medicine for individual 1 and the University of Texas Southwestern for individual 2. All other institutions involved in human participant research received local IRB approval. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the corresponding IRBs. All individual-level data was deidentified before analysis and publication of this work. Written consent for the use of images used in Figure 1 was obtained from both individual’s families by the clinical teams caring for each individual.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Consortia

The Undiagnosed Diseases Network authors include: Carlos A. Bacino, Ashok Balasubramanyam, Lindsay C. Burrage, Hsiao-Tuan Chao, Ivan Chinn, Gary D. Clark, William J. Craigen, Hongzheng Dai, Lisa T. Emrick, Shamika Ketkar, Seema R. Lalani, Brendan H. Lee, Richard A. Lewis, Ronit Marom, James P. Orengo, Jennifer E. Posey, Lorraine Potocki, Jill A. Rosenfeld, Elaine Seto, Daryl A. Scott, Arjun Tarakad, Alyssa A. Tran, Tiphanie P. Vogel, Monika Weisz Hubshman, Kim Worley, Hugo J. Bellen, Michael F. Wangler, Shinya Yamamoto, Oguz Kanca, Christine M. Eng, Pengfei Liu, Patricia A. Ward, Edward Behrens, Marni Falk, Kelly Hassey, Kosuke Izumi, Gonench Kilich, Kathleen Sullivan, Adeline Vanderver, Zhe Zhang, Anna Raper, Vaidehi Jobanputra, Mohamad Mikati, Allyn McConkie-Rosell, Kelly Schoch, Vandana Shashi, Rebecca C. Spillmann, Queenie K.-G. Tan, Nicole M. Walley, Alan H. Beggs, Gerard T. Berry, Lauren C. Briere, Laurel A. Cobban, Matthew Coggins, Elizabeth L. Fieg, Frances High, Ingrid A. Holm, Susan Korrick, Joseph Loscalzo, Richard L. Maas, Calum A. MacRae, J. Carl Pallais, Deepak A. Rao, Lance H. Rodan, Edwin K. Silverman, Joan M. Stoler, David A. Sweetser, Melissa Walker, Jessica Douglas, Emily Glanton, Shilpa N. Kobren, Isaac S. Kohane, Kimberly LeBlanc, Audrey Stephannie C. Maghiro, Rachel Mahoney, Alexa T. McCray, Amelia L. M. Tan, Surendra Dasari, Brendan C. Lanpher, Ian R. Lanza, Eva Morava, Devin Oglesbee, Guney Bademci, Deborah Barbouth, Stephanie Bivona, Nicholas Borja, Joanna M. Gonzalez, Kumarie Latchman, LéShon Peart, Adriana Rebelo, Carson A. Smith, Mustafa Tekin, Willa Thorson, Stephan Zuchner, Herman Taylor, Heather A. Colley, Jyoti G. Dayal, Argenia L. Doss, David J. Eckstein, Sarah Hutchison, Donna M. Krasnewich, Laura A. Mamounas, Teri A. Manolio, Tiina K. Urv, Maria T. Acosta, Precilla D’Souza, Andrea Gropman, Ellen F. Macnamara, Valerie V. Maduro, John J. Mulvihill, Donna Novacic, Barbara N. Pusey Swerdzewski, Camilo Toro, Colleen E. Wahl, David R. Adams, Ben Afzali, Elizabeth A. Burke, Joie Davis, Margaret Delgado, Jiayu Fu, William A. Gahl, Neil Hanchard, Yan Huang, Wendy Introne, Orpa Jean-Marie, May Christine V. Malicdan, Marie Morimoto, Leoyklang Petcharet, Francis Rossignol, Marla Sabaii, Ben Solomon, Cynthia J. Tifft, Lynne A. Wolfe, Heidi Wood, Aimee Allworth, Michael Bamshad, Anita Beck, Jimmy Bennett, Elizabeth Blue, Peter Byers, Sirisak Chanprasert, Michael Cunningham, Katrina Dipple, Daniel Doherty, Dawn Earl, Ian Glass, Anne Hing, Fuki M. Hisama, Martha Horike-Pyne, Gail P. Jarvik, Jeffrey Jarvik, Suman Jayadev, Emerald Kaitryn, Christina Lam, Danny Miller, Ghayda Mirzaa, Wendy Raskind, Elizabeth Rosenthal, Emily Shelkowitz, Sam Sheppeard, Andrew Stergachis, Virginia Sybert, Mark Wener, Tara Wenger, Raquel L. Alvarez, Gill Bejerano, Jonathan A. Bernstein, Devon Bonner, Terra R. Coakley, Paul G. Fisher, Page C. Goddard, Meghan C. Halley, Jason Hom, Jennefer N. Kohler, Elijah Kravets, Beth A. Martin, Shruti Marwaha, Chloe M. Reuter, Maura Ruzhnikov, Jacinda B. Sampson, Kevin S. Smith, Shirley Sutton, Holly K. Tabor, Rachel A. Ungar, Matthew T. Wheeler, Euan A. Ashley, William E. Byrd, Andrew B. Crouse, Matthew Might, Mariko Nakano-Okuno, Jordan Whitlock, Manish J. Butte, Rosario Corona, Esteban C. Dell’Angelica, Naghmeh Dorrani, Emilie D. Douine, Brent L. Fogel, Alden Huang, Deborah Krakow, Sandra K. Loo, Martin G. Martin, Julian A. Martínez-Agosto, Elisabeth McGee, Stanley F. Nelson, Shirley Nieves-Rodriguez, Jeanette C. Papp, Neil H. Parker, Genecee Renteria, Janet S. Sinsheimer, Jijun Wan, Justin Alvey, Ashley Andrews, Jim Bale, John Bohnsack, Lorenzo Botto, John Carey, Nicola Longo, Paolo Moretti, Laura Pace, Aaron Quinlan, Matt Velinder, Dave Viskochil, Gabor Marth, Pinar Bayrak-Toydemir, Rong Mao, Monte Westerfield, Anna Bican, Thomas Cassini, Brian Corner, Rizwan Hamid, Serena Neumann, John A. Phillips III, Lynette Rives, Amy K. Robertson, Kimberly Ezell, Joy D. Cogan, Nichole Hayes, Dana Kiley, Kathy Sisco, Jennifer Wambach, Daniel Wegner, Dustin Baldridge, F. Sessions Cole, Stephen Pak, Timothy Schedl, Jimann Shin, and Lilianna Solnica-Krezel

Data Availability

All deidentified data and materials will be made available to qualified researchers upon request.

References

- 1.Jeon YG, Kim YY, Lee G, Kim JB. Physiological and pathological roles of lipogenesis. Nat Metab. 2023;5(5):735–759. 10.1038/s42255-023-00786-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1125–1131. 10.1172/JCI15593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rawson RB. The SREBP pathway — insights from insigs and insects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(8):631–640. 10.1038/nrm1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimano H, Sato R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology — divergent pathophysiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(12):710–730. 10.1038/nrendo.2017.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89(3):331–340. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan EA, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Sakai J. Cleavage site for sterol-regulated protease localized to a Leu–Ser bond in the lumenal loop of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(19):12778–12785. 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witkop CJ, White JG, King RA, Dahl MV, Young WG, Sauk JJ. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: a disease apparently of desmosome and gap junction formation. Am J Hum Genet. 1979;31(4):414–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boralevi F, Haftek M, Vabres P, et al. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: clinical, ultrastructural and genetic study of eight patients and literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(2):310–318. 10.1111/J.1365-2133.2005.06664.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Humbatova A, Liu Y, et al. Mutations in SREBF1, encoding sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1, cause autosomal-dominant IFAP syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107(1):34–45. 10.1016/J.AJHG.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang D, Tomisato W, Su L, et al. Skin-specific regulation of SREBP processing and lipid biosynthesis by glycerol kinase 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(26):E5197–E5206. 10.1073/PNAS.1705312114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evers BM, Farooqi MS, Shelton JM, et al. Hair growth defects in Insig-deficient mice caused by cholesterol precursor accumulation and reversed by simvastatin. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(5):1237–1248. 10.1038/JID.2009.442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leithauser LA, Mutasim DF. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia: unique histopathological findings in skin lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(4):431–439. 10.1111/J.1600-0560.2011.01857.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheman AJ, Ray DJ, Witkop CJ, Dahl MV. Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia. Case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(2 Pt 2):351–357. 10.1016/S0190-9622(89)80033-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo Y, Fu J, Wang H, et al. Site-1 protease deficiency causes human skeletal dysplasia due to defective inter-organelle protein trafficking. JCI Insight. 2018;3(14):e121596. 10.1172/JCI.INSIGHT.121596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patra D, DeLassus E, Liang G, Sandell LJ. Cartilage-specific ablation of site-1 protease in mice results in the endoplasmic reticulum entrapment of type IIb procollagen and down-regulation of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105674. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0105674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patra D, DeLassus E, Hayashi S, Sandell LJ. Site-1 protease is essential to growth plate maintenance and is a critical regulator of chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation in postnatal mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(33):29227–29240. 10.1074/jbc.M110.208686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patra D, Xing X, Davies S, et al. Site-1 protease is essential for endochondral bone formation in mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;179(4):687–700. 10.1083/JCB.200708092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naiki M, Mizuno S, Yamada K, et al. MBTPS2 mutation causes BRESEK/BRESHECK syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(1):97–102. 10.1002/AJMG.A.34373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaghoobi R, Omidian M, Sina N, Abtahian SA, Panahi-Bazaz MR. Olmsted syndrome in an Iranian family: report of two new cases. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10(2):246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindert U, Cabral WA, Ausavarat S, et al. MBTPS2 mutations cause defective regulated intramembrane proteolysis in X-linked osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11920. 10.1038/NCOMMS11920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castori M, Covaciu C, Paradisi M, Zambruno G. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(1):53–58. 10.1016/J.EJMG.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UDN manual of operations. Accessed December 21, 2023. https://undiagnosed.hms.harvard.edu/research/udn-manual-of-operations/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman PJ, Hart RK, Gretton LJ, Brookes AJ, Dalgleish R. VariantValidator: accurate validation, mapping, and formatting of sequence variation descriptions. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(1):61–68. 10.1002/HUMU.23348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald JR, Ziman R, Yuen RKC, Feuk L, Scherer SW. The Database of Genomic Variants: a curated collection of structural variation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D986–D992. 10.1093/NAR/GKT958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutta D, Kanca O, Byeon SK, et al. A defect in mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis impairs iron metabolism and causes elevated ceramide levels. Nat Metab. 2023;5(9):1595–1614. 10.1038/s42255-023-00873-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei P, Xue W, Zhao Y, Ning G, Wang J. CRISPR-based modular assembly of a UAS-cDNA/ORF plasmid library for more than 5500 Drosophila genes conserved in humans. Genome Res. 2020;30(1):95–106. 10.1101/gr.250811.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chilian M, Vargas Parra K, Sandoval A, Ramirez J, Yoon WH. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated tissue-specific knockout and cDNA rescue using sgRNAs that target exon-intron junctions in Drosophila melanogaster. Star Protoc. 2022;3(3):101465. 10.1016/J.XPRO.2022.101465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venken KJT, He Y, Hoskins RA, Bellen HJ. P[acman]: a BAC transgenic platform for targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in D. melanogaster. Science. 2006;314(5806):1747–1751. 10.1126/science.1134426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Zhang K, Sandoval H, et al. Glial lipid droplets and ROS Induced by mitochondrial defects promote neurodegeneration. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):177–190. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moulton MJ, Barish S, Ralhan I, et al. Neuronal ROS-induced glial lipid droplet formation is altered by loss of Alzheimer’s disease–associated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(52): e2112095118. 10.1073/pnas.2112095118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Splinter K, Adams DR, Bacino CA, et al. Effect of genetic diagnosis on patients with previously undiagnosed disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2131–2139. 10.1056/NEJMoa1714458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith FJD, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nat Genet. 2006;38(3):337–342. 10.1038/ng1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, MacKenzie KR, Putluri N, Maletić-Savatić M, Bellen HJ. The glia-neuron lactate shuttle and elevated ROS Promote Lipid synthesis in neurons and lipid droplet accumulation in glia via APOE/D. Cell Metab. 2017;26(5):719–737.e6. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarc E, Petan T. Lipid droplets and the management of cellular stress. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92(3):435–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Zhang K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated lipid droplet formation and Type II diabetes. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:247275. 10.1155/2012/247275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barral DC, Staiano L, Guimas Almeida C, et al. Current methods to analyze lysosome morphology, positioning, motility and function. Traffic. 2022;23(5):238–269. 10.1111/TRA.12839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang G, Yang J, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Diminished hepatic response to fasting/refeeding and liver X receptor agonists in mice with selective deficiency of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):9520–9528. 10.1074/jbc.M111421200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vergnes L, Chin RG, de Aguiar Vallim TA, et al. SREBP-2-deficient and hypomorphic mice reveal roles for SREBP-2 in embryonic development and SREBP-1c expression. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(3):410–421. 10.1194/jlr.M064022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osborne TF, Espenshade PJ. Evolutionary conservation and adaptation in the mechanism that regulates SREBP action: what a long, strange tRIP it’s been. Genes Dev. 2009;23(22):2578–2591. 10.1101/GAD.1854309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espenshade PJ, Hughes AL. Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41(1):401–427. 10.1146/ANNUREV.GENET.41.110306.130315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seegmiller AC, Dobrosotskaya I, Goldstein JL, Ho YK, Brown MS, Rawson RB. The SREBP pathway in Drosophila: regulation by palmitate, not sterols. Dev Cell. 2002;2(2):229–238. 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunte AS, Matthews KA, Rawson RB. Fatty acid auxotrophy in Drosophila larvae lacking SREBP. Cell Metab. 2006;3(6):439–448. 10.1016/J.CMET.2006.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Al-Ouran R, Hu Y, et al. MARRVEL: integration of human and model organism genetic resources to facilitate functional annotation of the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(6):843–853. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samocha KE, Robinson EB, Sanders SJ, et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):944–950. 10.1038/ng.3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinodoz M, Royer-Bertrand B, Cisarova K, Di Gioia SA, Superti-Furga A, Rivolta C. DOMINO: using machine learning to predict genes associated with dominant disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(4):623–629. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen X, Shen J, Prywes R. The luminal domain of ATF6 senses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and causes translocation of ATF6 from the er to the Golgi. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(15):13045–13052. 10.1074/jbc.M110636200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai Y, Arikkath J, Yang L, Guo ML, Periyasamy P, Buch S. Interplay of endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in neurodegenerative disorders. Autophagy. 2016;12(2):225–244. 10.1080/15548627.2015.1121360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braulke T, Carette JE, Palm W. Lysosomal enzyme trafficking: from molecular mechanisms to human diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2024;34(3):198–210. 10.1016/J.TCB.2023.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakpa KL, Khan N, Afghah Z, Chen X, Geiger JD. Lysosomal stress response (LSR): physiological importance and pathological relevance. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021;16(2):219–237. 10.1007/S11481-021-09990-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elfrink HL, Zwart R, Baas F, Scheper W. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and alters lysosomal morphology and distribution. Mol Cells. 2013;35(4):291–297. 10.1007/S10059-013-2286-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim A, Cunningham KW. A LAPF/phafin1-like protein regulates TORC1 and lysosomal membrane permeabilization in response to endoplasmic reticulum membrane stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26(25):4631–4645. 10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dauer P, Gupta VK, McGinn O, et al. Inhibition of Sp1 prevents ER homeostasis and causes cell death by lysosomal membrane permeabilization in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1564. 10.1038/S41598-017-01696-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bae D, Moore KA, Mella JM, Hayashi SY, Hollien J. Degradation of Blos1 mRNA by IRE1 repositions lysosomes and protects cells from stress. J Cell Biol. 2019;218(4):1118–1127. 10.1083/JCB.201809027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakashima A, Cheng SB, Kusabiraki T, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress disrupts lysosomal homeostasis and induces blockade of autophagic flux in human trophoblasts. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11466. 10.1038/S41598-019-47607-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhattarai KR, Chaudhary M, Kim HR, Chae HJ. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response failure in diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(9):672–675. 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Platt FM, d’Azzo A, Davidson BL, Neufeld EF, Tifft CJ. Lysosomal storage diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):27. 10.1038/s41572-018-0025-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rook ME, Southwell AL. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy: from design to the Huntington disease clinic. BioDrugs. 2022;36(2):105–119. 10.1007/S40259-022-00519-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhuri K, Bechtold C, Quijano E, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides: an emerging area in drug discovery and development. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1–24. 10.3390/JCM9062004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamisuki S, Shirakawa T, Kugimiya A, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of diarylthiazole derivatives that inhibit activation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Med Chem. 2011;54(13):4923–4927. 10.1021/JM200304Y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hay BA, Abrams B, Zumbrunn AY, et al. Aminopyrrolidineamide inhibitors of site-1 protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17(16):4411–4414. 10.1016/J.BMCL.2007.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Biesecker LG, Adam MP, Alkuraya FS, et al. A dyadic approach to the delineation of diagnostic entities in clinical genomics. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108(1):8–15. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strande NT, Riggs ER, Buchanan AH, et al. Evaluating the clinical validity of gene-disease associations: an evidence-based framework developed by the clinical genome resource. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(6):895–906. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All deidentified data and materials will be made available to qualified researchers upon request.