Summary

Background

Early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is crucial for improving clinical outcomes. However, the sensitivity of primary serological marker cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is suboptimal for detecting early-stage EOC. Tumour-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) are promising biomarkers for early cancer detection.

Methods

We developed an EOC EV Surface Protein-mRNA Integration (SPRI) Assay for early detection of EOC. This assay quantifies reference mRNAs within subpopulations of EOC EVs enriched by EV Click Beads targeting three EOC EV surface protein markers. Three EOC EV surface protein markers (i.e., FRα, MSLN, and TROP2) were selected through a bioinformatic framework using multi-omics data and underwent rigorous validation using EOC cell lines and EOC tissue microarrays. We then explored the translational potential of the EOC EV SPRI Assay through a phase II case–control study. The EOC EV SPRI Score was established using a logistic regression model in a training cohort (n = 118) and then validated in an independent validation cohort (n = 118).

Findings

EOC EV SPRI Score demonstrated superior performance for distinguishing EOC from benign ovarian masses and healthy donors with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97–1.00) in the training cohort and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.88–0.97) in the validation cohort. It outperformed matched serum CA125, and the performance remained excellent in earlier stages of EOC (Stage I/II, AUROC = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.98) and the subgroup of high-grade serous carcinoma (AUROC = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97).

Interpretation

The EOC EV SPRI assay demonstrated significant potential for early detection of EOC and improving long-term patient outcomes.

Funding

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (R01CA277530, R01CA255727, R01CA253651, R01CA253651-04S1, R21CA280444, R01CA246304, U01EB026421, R44CA288163, U01CA271887, and U01CA230705), DOD (HT9425-23-1-0361) and OCRA (CRDG-2023-3-1000) for the U.S. study. Additionally, we acknowledge the support of the Science and Technology Foundation of Suzhou (SZS2023006, SSD2023004) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2023335) for the work conducted at SINANO.

Keywords: Epithelial ovarian cancer, Extracellular vesicle, Liquid biopsy, Biomarker

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is often diagnosed at advanced stages due to vague symptoms and unreliable screening. Early detection is crucial to improve outcomes. Tumour-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) appear in the bloodstream at relatively early stages of disease and remain detectable throughout all stages, making them a promising biomarker for early cancer detection.

Added value of this study

In our study, we developed a convenient and sensitive approach, termed EOC EV Surface Protein-mRNA Integration (SPRI) Assay, for quantifying EOC EV subpopulations by measuring reference mRNAs within these EVs. The resultant EOC EV SPRI Score demonstrated superior performance for distinguishing EOC from benign ovarian masses and healthy donors. Specifically, it outperformed matched serum CA125 and the performance remained excellent in earlier stages of EOC and the subgroup of high-grade serous carcinoma.

Implications of all the available evidence

These findings demonstrated significant potential of the EOC EV SPRI assay for early detection of EOC and improving long-term patient outcomes.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer ranks as the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide.1,2 More than 90% of newly diagnosed ovarian cancer cases are classified as epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), with around 70% being high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC).3 EOC is frequently diagnosed at advanced stages due to the absence of early symptoms and the lack of reliable screening methods, resulting in poor survival outcomes.4,5 Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is a primary serological biomarker used to aid in EOC diagnosis6 and has been integrated with other diagnostics to improve diagnostic performance.7, 8, 9 For example, the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) pairs CA125 with human epididymis protein 4 (HE4), and the OVA1™ and Overa tests combine CA125 with four additional protein biomarkers.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 These tests have been approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to aid in assessing the likelihood of malignancy in women with an ovarian adnexal mass. Additionally, CA125 and pelvic ultrasound scan (with or without transvaginal ultrasound [TVUS] as indicated) is recommended in the initial investigations for post-menopausal women presenting with signs or symptoms of ovarian cancer.15 Despite these efforts, only around 20% of EOC was diagnosed at early stages.4 Therefore, exploring effective diagnostics for early detection of EOC is critically needed to enable timely intervention and improve patient outcomes.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a heterogeneous group of phospholipid bilayer-enclosed nanoparticles released by all cell types,16, 17, 18 particularly tumour cells and those within the tumour microenvironment.19 Tumour-derived EVs appear in the bloodstream at relatively early stages of disease and remain detectable throughout all stages,20 making them a promising biomarker for early cancer detection. Tumour EVs carry surface protein markers on their membranes that reflect the characteristics of their parental tumour cells,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 enabling targeted enrichment of specific EV subpopulations.27 Additionally, tumour EVs contain unique biomolecular cargo such as DNA, RNA, and proteins, which are encapsulated and well-protected by the EV membrane.28,29 Enriching and quantifying tumour EV subpopulations by targeting specific surface protein markers30,31 presents a promising approach for liquid biopsy-based early cancer detection.32, 33, 34

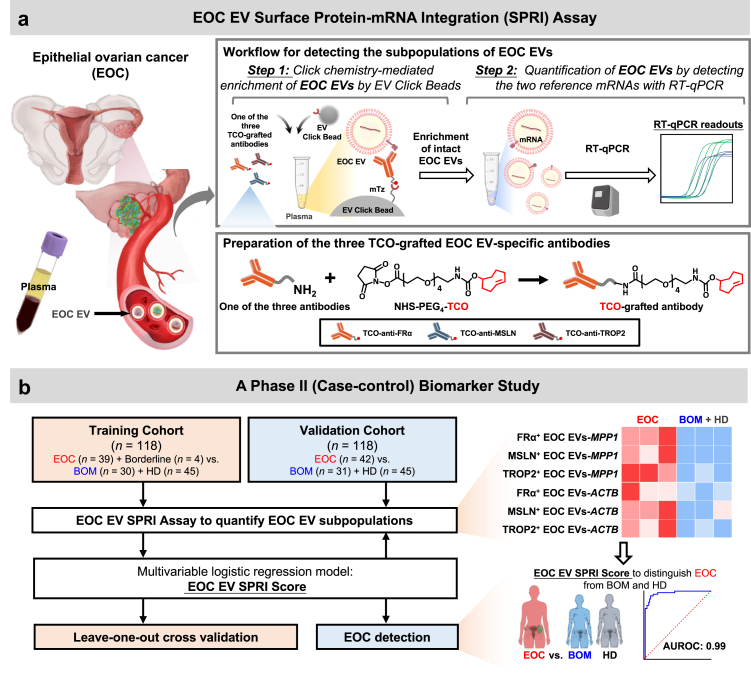

In this study, our aim is to develop an EV-based assay for the early detection of EOC by quantifying specific subpopulations of EOC EVs. We designed a convenient and sensitive approach, termed EOC EV Surface Protein-mRNA Integration (SPRI) Assay, for quantifying EOC EV subpopulations by measuring reference mRNAs within these EVs. The EOC EV SPRI Assay was conducted via a streamlined two-step workflow (Fig. 1a): i) click chemistry-mediated enrichment of EOC EVs by EV Click Beads targeting three EOC EV surface protein markers (i.e., FRα, MSLN, and TROP2), and ii) quantification of two reference mRNAs (i.e., MPP1 and ACTB) within the enriched EOC EVs via RT-qPCR. The three EOC EV surface protein markers were rigorously selected through a bioinformatic framework using multi-omics data and validated using EOC cell lines and tissue microarrays (TMA). The two reference mRNAs were also thoroughly selected and validated to ensure consistent expression within EOC EVs. mRNA quantity within EVs has been used as a surrogate measure for EV amounts.35, 36, 37 In addition, our pilot study demonstrated a linear correlation between the quantity of reference mRNAs within EVs and the EV amounts (R2 ranged 0.988–0.998). This finding indicates that the quantity of reference mRNAs within enriched EOC EVs accurately reflects the amount of EOC EVs. Consequently, the EOC EV SPRI assay enables precise quantification of EOC EV subpopulations by measuring the reference mRNAs they contain. We then explored the translational potential of the EOC EV SPRI Assay through a phase II case–control study (Fig. 1b). A logistic regression model was applied to generate EOC EV SPRI Score, which was established in a training cohort (n = 118) and then validated in an independent validation cohort (n = 118). The EOC EV SPRI Score demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) of 0.99 in the training cohort and 0.93 in the validation cohort for distinguishing EOC from benign ovarian masses (BOM) and healthy donors (HD). The performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score remained excellent in the subgroup of earlier stages EOC (Stage I/II) and the subtype of high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) with an AUROC of 0.93 and 0.97, respectively. The EOC EV SPRI Assay holds great promise for augmenting current diagnostic modalities for the early detection of EOC.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (EOC) Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Surface Protein-mRNA Integration (SPRI) Assay for early detection of EOC. (a) The EOC EV Surface Protein-mRNA Integration (SPRI) Assay was carried out via a two-step workflow––Step 1: Click chemistry-mediated enrichment of EOC EVs by EV Click Beads, and Step 2: Quantification of enriched EOC EVs by detecting the two reference mRNAs through reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Three trans-cyclooctene (TCO)-grafted EOC-specific antibodies, i.e., TCO-anti-folate receptor alpha (FRα), TCO-anti-mesothelin (MSLN), and TCO-anti-trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP2) were prepared to enable click chemistry-mediated enrichment of EOC EV subpopulations. Each EOC EV subpopulation was then subjected to RT-qPCR quantification of the two reference mRNAs, i.e., MPP1 and ACTB. The signals from MPP1 and ACTB reflect the amount of EOC EVs. (b) Clinical study design flowchart. First, plasma samples from eligible participants were collected from a training cohort comprising 39 patients with EOC, 4 with borderline ovarian tumour, 30 with benign ovarian masses (BOM), and 45 healthy donors (HD). All samples were subjected to EOC EV SPRI Assay to quantify the six subpopulations of EOC EVs (i.e., FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1, FRα+ EOC EVs-ACTB, MSLN+ EOC EVs-ACTB, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-ACTB). Subsequently, the EOC EV SPRI Score was generated by logistic regression analysis and cross-validated by leave-one-out cross validation. Finally, the diagnostic performance of EOC EV SPRI Score was validated in an independent validation cohort comprising 42 EOC, 31 BOM, and 45 HD.

Methods

Selection of EOC EV surface protein markers via a bioinformatic framework

To select EOC EV surface protein markers for EV enrichment, we developed a bioinformatic framework using multi-omics data (Supplementary Fig. S1). Our approach began with compiling data from three key sources: a) EOC cell line protein data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopaedia (CCLE),38 b) EOC tissue protein data from the Proteomics Data Commons (PDC),39 and c) EOC tissue RNA data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).40 Subsequently, the framework proceeded through three main steps: i) selecting EOC-specific markers and excluding housekeeping and haematopoietic proteins41; ii) identifying EOC EV surface markers based on criteria such as a GESP score >10 in The Cancer Surfaceome Atlas (TCSA),42 presence as EV markers in Vesiclepedia (with >10 supporting EV studies),43,44 high expression in EOC or a literature score >0.3 in the Open Targets Platform,45 and low expression in immune cells as identified in Differential Map (DMAP)46; iii) narrowing down to the top three druggable EOC EV surface markers based on the number of registered clinical trials for targeted therapies in EOC, including antibody–drug conjugate (ADC), chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T, CAR-NK, and monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Supplementary Table S1).

Selecting reference mRNAs for EOC EV quantification

The reference mRNA selection process for EOC EV quantification is outlined in Supplementary Fig. S2. This approach integrates data from two distinct sources47: (i) a group of nine classical reference genes and (ii) the top 10 highly expressed genes in cancer EVs, derived from an unbiased analysis of pooled cancer mRNA-Seq datasets.

From the classical reference genes, the three most abundantly expressed (ACTB, B2M, and RPL13A) were shortlisted. Similarly, from the cancer EV candidates, the three genes with the highest stability (OAZ1, SERF2, and MPP1) were selected. These six genes were then consolidated into a single pool of candidate reference genes.

The final selection involved evaluating these candidates using ovarian cancer RNA data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), focussing on their association with overall survival, specifically targeting genes with a hazard ratio (HR) ≥ 1. This rigorous analysis identified MPP1 and ACTB as reference mRNAs for EOC EV quantification.

EOC cell line culture

EOC cell lines OVCAR3 (RRID: CVCL_0465), purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and OVCAR8 (RRID:CVCL_1629), obtained from a tumour repository of the NCI division of cancer treatment and diagnosis, were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 11875093) with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A5670701) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 15140122). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of EOC EV surface markers

For IF staining, OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 cells were seeded on glass coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Following blocking with 2% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Cat# 017-000-001) for 30 min, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-human FRα (R & D Systems Cat# MAB5646, RRID:AB_2278620), anti-human MSLN (R & D Systems Cat# MAB32652, RRID:AB_2147798), or anti-human TROP2 (R & D Systems Cat# AF650, RRID:AB_2205667). After washing with PBS, these cells were incubated with respective secondary antibodies including donkey anti-rat IgG (Abcam Cat# ab150153, RRID:AB_2737355, 1:1000 v/v), donkey anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes Cat# A-21202, RRID:AB_141607, 1:1000 v/v), or donkey anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-2024, RRID:AB_631727, 1:1000 v/v). DAPI solution (Invitrogen Cat# 62248, 1:1000 v/v) was added before imaging on a Nikon Eclipse 90i fluorescence microscope using a 40× objective.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining on EOC TMA

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and IHC staining for FRα, MSLN, and TROP2 were performed on a TMA generated comprising 133 archived EOC samples. Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral formalin for 24 h and embedded in paraffin according to the standard operating procedure for tissue in the pathology department. Serial 5 μm-thick tissue microarray slides from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks were cut and mounted on poly-l-lysine coated glass slides. Standard IHC protocols were optimised for each antibody and assessed using the Aperio ScanScope AT high throughput scanning system. The IHC staining results were evaluated using a four-point scale staining intensity (none, 0; weak, 1+; moderate, 2+; strong, 3+), with scores of 1+ or higher considered positive.

Synthesis of trans-cyclooctene (TCO)-grafted EOC EV-specific antibodies

EOC EV-specific antibodies (1 mg/mL, 20 μL) and TCO-PEG4-NHS (1 mM, 2.7 μL, Vector Labs Cat# CCT-A137) were mixed in net volume 100 μL of PBS (pH = 8.4) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature while shaking. Excess TCO-PEG4-NHS was removed by Zeba™ 40 kDa column as per manufacturer's instruction. The obtained amount of the TCO-grafted EOC EV-specific antibody was determined by NanoDrop® with A280.

Fabrication of EV Click Beads

The 5 μm silica microbeads (10 mg, Bangs Lab Cat# 16595) were centrifuged and incubated with 1 M HCl (200 μL) for 10 min to regenerate hydroxyl groups. The beads were washed twice with ethanol (EtOH) to facilitate solvent exchange and subsequently functionalized with amine groups by incubating with 5% (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) in EtOH (500 μL) for 45 min at room temperature. The amine-functionalized silica microbeads (silica-NH2) were washed twice with PBS and once with deionised water (ddH2O), then air-dried and stored at 4 °C until use.

To functionalise methyltetrazine (mTz) group on the surface, 2 mg of silica-NH2 microbeads were reacted with 6 nmol of mTz-PEG4-NHS (Vector Labs Cat# CCT-1069) in DMSO for 30 min, followed by addition of 120 nmol of mPEG4-NHS (ThermoFisher Cat# 22341) for an additional 30 min. All reactions were conducted in the dark to prevent photodegradation of mTz compounds. Residual NHS compounds were quenched by adding 120 μL of Tris buffer (pH 8.4) and incubating for 10 min. The beads were then washed three times with ddH2O, followed by two times with EtOH, and dried at room temperature. The dried beads were stored at 4 °C, protected from light, and reconstituted with mild sonication before use.

Collection of EOC EVs from cell culture medium

OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 cells were cultured in 18 Nunc™ EasYFlask™ Flasks (175 cm2, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 156380) until 80% confluency. Before EV collection, the culture medium was replaced to serum-free cultured medium (13 mL per flask) to starve the cells for 24 h. The conditioned medium was collected and centrifugated at 300 g, 4 °C for 10 min followed by a second centrifugation step at 2800 g, 4 °C for 10 min to remove cell debris. The medium was gently transferred to Ultra-Clear Tubes (38 mL per tube, Beckman Coulter Cat# C14292) and then ultracentrifuged at 100,000 g, 4 °C for 90 min. The OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 EV pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of PBS and regarded as EOC EV stock solution. To confirm that ACTB and MPP1 transcripts are protected within EVs, we treated OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 EVs with RNase. The EVs were incubated with RNase (Invitrogen Cat# 12091039) at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by treatment with an RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific Cat# EO0381) at 37 °C for an additional 30 min, and subsequently analysed by RT-ddPCR.

Characterisation of EOC EVs

The size distribution and concentration of EOC EVs were determined using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) by ViewSizer 3000 (HORIBA Scientific, Japan). Samples were diluted into 1 mL of 0.22 μm filtered PBS at appropriate dilution rate ranging from 100 to 10,000-fold. Each sample was replicated in three runs. Total protein amount of EVs was determined by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM images were obtained using a Supra 40VP SEM (Zeiss, Germany) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. EV samples and EV-immobilised EV Click Beads were cast onto a silicon wafer and air-dried at room temperature overnight. The dried samples were sputter-coated with a gold target (Ted Pella, USA). TEM images were acquired using a Tecnai 12 Quick Cryo-EM (FEI, USA). Prior to sample preparation, a 400-mesh carbon-coated copper grid (Ted Pella, USA) was glow discharged using the PELCO easiGlow™ Glow Discharge Cleaning System (Ted Pella, USA) to facilitate hydrophilization, and the grid was used within 1 h. EV samples and EV-immobilised EV Click Beads were applied to the glow discharged grid and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. Excess samples were removed by blotting with filter paper, and the grid was washed three times with 5% uranyl acetate. Subsequently, the samples were stained with 5% uranyl acetate for 1 min. For unstained samples, distilled water was utilised instead of uranyl acetate solution following the same procedure.

EOC EVs were analysed by SEM and TEM. For EM imaging of EOC EVs, harvested OVCAR8 EV samples were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min. The SEM and TEM samples were prepared as described above and observed using the Supra 40VP SEM and Tecnai 12 Quick Cryo-EM, respectively.

EOC EV-immobilised EV Click Beads were analysed by SEM and immunogold TEM. OVCAR8 EVs were enriched on EV Click Bead with TCO-anti-MSLN (using the condition as described in EOC EV enrichment from plasma samples section). The EOC EV-immobilised Click Bead samples were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% PFA solution for 30 min at room temperature. For SEM specimens, the samples were washed with ddH2O and prepared as described above. For immunogold staining, EV-immobilised EV Click Beads were incubated with anti-CD63 (Abcam Cat# ab193349, RRID:AB_3095976, 1:50 dilution) in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature and washed twice with PBS. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with anti-mouse IgG nanogold (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs Cat# 115-205-068, RRID:AB_2338730, 12 nm, 1:20 dilution) in 1% BSA for 30 min and washed with ddH2O. The gold-labelled samples were dropped onto glow discharged TEM grids, and the specimen was prepared without staining as described above.

Patient enrolment

This retrospective biomarker study was conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) as summarised in Supplementary Table S2. All samples from patients with EOC or BOM and female HDs were obtained according to the protocols approved by the IRB. Females aged 18 years and older were eligible, with exclusion criteria for any individuals with any other active malignancy within 5 years. Plasma samples were randomly collected between 2006 and 2024 at multiple centres as listed in Supplementary Table S2. EOC was diagnosed based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines with confirmation by histopathological review performed by gynaecological pathology specialists. Diagnostic confirmation included histopathology for patients who underwent needle biopsy or surgery, including hysterectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy.

In UCLA, HDs were recruited at the UCLA Blood & Platelet Centre under an IRB-approved protocol (No. 19-000857). In SINANO, plasma samples from HD were collected from physical examination centres at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University and Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University under an IRB-approved protocol listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Blood sample processing

Peripheral venous blood from patients or HDs were collected in BD Vacutainer glass tube (BD Medical) with written informed consent from patients and followed by IRB. The plasma samples were collected and stored at −80 °C after centrifugation at 2000 rpm (4 °C, 10 min) and at 4600 g (4 °C, 10 min). For EV-depleted HD plasma samples adopted in synthetic plasma samples, peripheral venous blood was first centrifuged at 300 g (4 °C, 10 min) and at 4600 g (4 °C, 10 min).

Preparation of synthetic plasma samples

The EV-depleted plasma was prepared with ultracentrifugation. After transferring to Open-Top Thinwall Ultra-Clear Tubes (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), the supernatant underwent ultracentrifugation at 20,000 g (4 °C, 30 min) with the SW32 Ti rotor and Optima L-100 XP Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g (4 °C, 2 h). The resulting supernatant was collected as EV-depleted plasma and stored at −80 °C until use. Synthetic plasma samples mimicking EOC patient plasma were prepared to optimise and validate the function of EV Click Beads for enriching EOC EVs. OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 cell-derived EOC EVs were spiked into EV-depleted plasma from a female HD with a desired final EV concentration for EV linearity study. All samples were prepared in duplicate.

EOC EV enrichment from plasma samples

EOC EVs in both synthetic and blinded clinical plasma samples were enriched using EV Click Beads based on the optimised condition from our previous study.26 In brief, 100 ng of trans-cyclooctene (TCO)-grafted EOC EV-specific antibodies (i.e., TCO-anti-FRα, TCO-anti-MSLN, and TCO-anti-TROP2) were separately mixed with 100 μL of plasma sample for 45 min at room temperature. The plasma samples containing TCO-labelled EVs were incubated with EV Click Beads for 45 min followed by a centrifugation at 13,000 g for 1.5 min to remove the supernatant. EV-immobilised EV Click Beads were washed three times for further quantification.

Quantification of EOC EVs by detecting reference mRNAs with RT-qPCR

The enriched EOC EVs on EV Click Beads were lysed using 10 μL of XpressAmp™ Lysis Buffer containing 1% Thioglycerol (Promega, USA). Then the collected sample lysate was subjected to RT-qPCR using a PrimeDirect™ Probe RT-qPCR Mix (Takara, Japan), along with MPP1 or ACTB primers and probes (Supplementary Table S3) for EOC EV quantification by a CFX Duet Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA). A programmed Thermal Cycler was set at 90 °C for 3 min and 60 °C for 5 min followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s.

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range. Differences between two groups were determined using a two-sample t-test if data followed a normal distribution or nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test if data did not follow a normal distribution.

The sample size was calculated via AUROC comparison between the EOC EV SPRI Assay and serum CA125,48 using the paired DeLong's test. A sample size of 90 (36 cases of EOC, 54 cases of controls, the ratio of sample sizes in negative/positive groups is 3/2) is expected to have 80% power to detect the difference between the AUROCs for the EOC EV SPRI Assay versus serum CA125, assuming AUC = 0.93 for our EOC EV SPRI Assay, AUC = 0.80 for serum CA125, when a correlation between the assays of 0.6 was assumed. The power was obtained for a two-sided test at 0.05 significance level.

A stepwise logistic regression analysis was conducted in the training cohort to generate the final model (EOC EV SPRI Score), which was designed to discriminate EOC from BOM and HD controls. Youden's index was used to identify the optimal cutoff of EOC EV SPRI Score. Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was applied to estimate the performance of EOC EV SPRI Score in the training cohort (Supplementary Note S1). External validation of EOC EV SPRI Score was performed in the validation cohort. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and AUROC for EOC EV SPRI Score to discriminate EOC from BOM and HD controls at the optimal cut-off were estimated in both the training and validation cohorts. The difference of AUROCs between the EOC EV SPRI Score and serum CA125 was compared using the paired DeLong test.

All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc software (version 20.015, RRID:SCR_015044), IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23, RRID:SCR_016479), GraphPad Prism (version 9.2.0, RRID:SCR_002798), and R Studio (version 4.2.3, RRID:SCR_001905) with two-sided tests and a significance level of 0.05 (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, and ns > 0.05).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Office of the Human Research Protection Program at University of California, Los Angeles (#19-000857-AM-00013), the Office of Research Compliance and Quality Improvement at Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre (#0901), the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (#JD-LK-2022-079-01) and the Medical Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (#SWYX:NO.2024-198). Samples were collected only after obtaining written informed consent from the participants.

Role of funders

The funders had no role in the collection of data; the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

FRα, MSLN, and TROP2 are robustly expressed in EOC cells and tissues

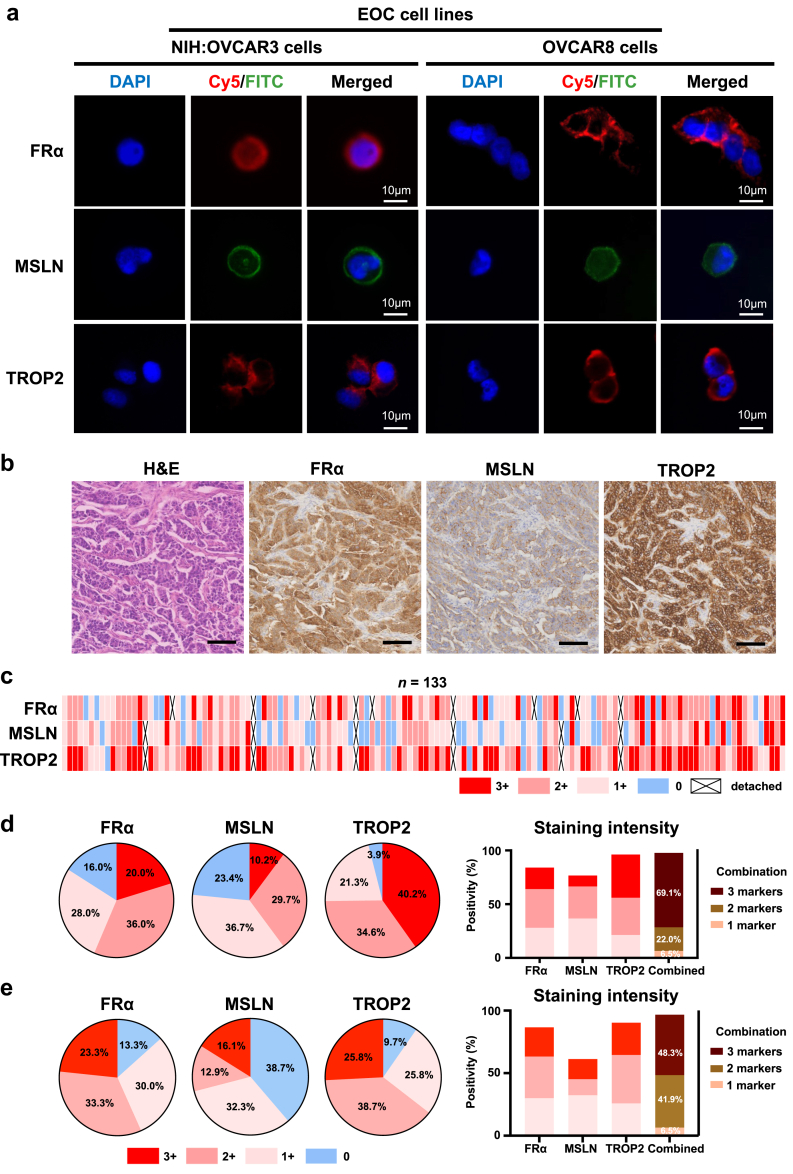

Through a bioinformatic framework using multi-omics data, three EOC EV surface protein markers (i.e., FRα, MSLN, and TROP2, Supplementary Fig. S1) were selected for enriching EOC EV subpopulations. Given that EV surface proteins often mirror those of their parental cells, we validated the expression of the three selected markers (i.e., FRα, MSLN, and TROP2) through immunofluorescence (IF) staining in the OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 human EOC cell lines. Representative IF micrographs showed strong expression of all three EOC EV surface protein markers in both EOC cell lines, with predominant localisation on the cell membranes (Fig. 2a). Minimal expression of the three proteins was observed in white blood cells of HD (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Validation of the three EOC EV surface protein markers using EOC cell lines and EOC tissue microarray (TMA). (a) Representative IF micrographs illustrating expression of FRα, MSLN, and TROP2 in OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 EOC cell lines. Blue: DAPI; red: Cy5; green: FITC. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Representative haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) images displaying expression of the three EOC EV surface protein markers on EOC TMA slides. Scale bar, 200 μm. (c) Heatmap summarising IHC staining intensity and positive percentages for each marker across EOC TMA. Pie charts depicting the percentage of (d) all-stage EOC samples and (e) earlier-stage EOC samples (stage I-II) categorised by IHC staining intensity of strong (3+), moderate (2+), weak (1+), and negative (0) for the three EOC EV surface protein. Bar charts summarising the percentage of IHC positive staining for each surface protein marker and their combinations in (d) all-stage EOC samples and (e) earlier-stage EOC samples.

Additionally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed on 133 EOC TMA samples, including 121 cases of HGSC, 2 cases of low-grade serous carcinoma, and 10 cases of clear cell carcinoma (see patient demographic data in Supplementary Table S4). Representative haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and IHC staining of the markers on EOC TMA samples were presented in Fig. 2b, with moderate membrane expression of MSLN and strong membrane expression of FRα and TROP2 on the same area of tumour tissues. IHC staining intensity results for each marker across the EOC TMA were depicted in Fig. 2c–d. Among 125 evaluable EOC samples for FRα (excluding cases where tumour tissue was not present or detached from the slides during IHC staining), 20.0% showed strong staining (3+), 36.0% showed moderate staining (2+), and 28.0% showed weak staining (1+). For MSLN, out of 128 evaluable EOC samples, 10.2% exhibited strong staining, 29.7% moderate staining, and 36.7% weak staining. TROP2 had the highest positivity among the three markers, with 40.2% of 127 evaluable samples showing strong staining, 34.6% moderate staining, and 21.3% weak staining. Overall, 97.6% of the evaluable EOC samples (120 out of 123) tested positive for at least one marker, and 69.1% were positive for all three markers. Of note, 96.8% (30 out of 31) of patients with stage I-II EOC have tested positive for at least 1 marker and 48.4% (15 out of 31) have tested positive for all 3 markers (Fig. 2e), which confirmed that the EOC EV-specific surface proteins are expressed in earlier-stage EOC. These results underscore the synergistic role of FRα, MSLN, and TROP2 in efficiently enriching heterogeneous EOC EV subpopulations, laying a solid foundation for their use in the EOC EV SPRI Assay.

EV Click Beads effectively immobilise EOC EVs through surface functionalisation

We utilised the OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 cell lines as a model to isolate EOC cell-derived EVs from conditioned media using ultracentrifugation. Following the Minimal Information for Studies of EVs (MISEV) 2023 guidelines,49 we characterised OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 EVs through nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). NTA indicated a consistent average size of 180.6 ± 88.7 nm for OVCAR3 EVs and 142.3 ± 67.2 for OVCAR8 EVs (Supplementary Fig. S4a), while TEM micrographs revealed their cupped or spherical morphologies (Supplementary Fig. S4b). In addition, NTA further determined the EV particle number to be 5.44 × 1010 particles/mL, and the total protein content of OVCAR3 EVs averaged at 328 ± 2 μg/mL. Following MISEV 2023 guidelines, the ratio of protein amount to particle number was determined to be 6.03 × 10−9 μg/particle.

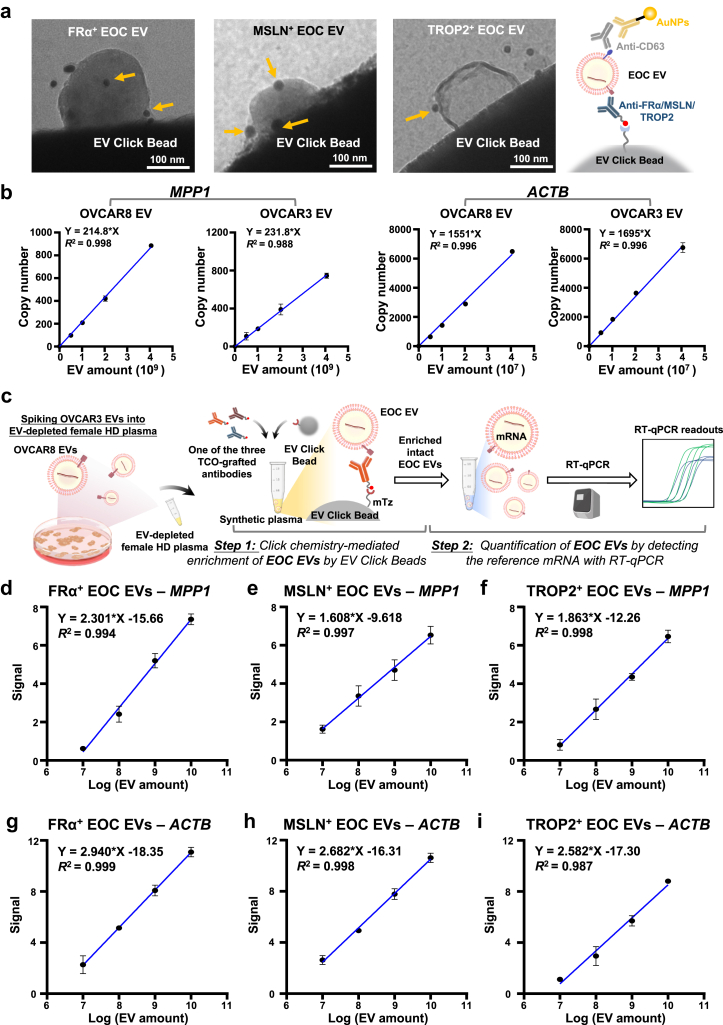

To efficiently enrich EOC EVs, we synthesised mTz-grafted EV Click Beads based on the outstanding performance of our previous click chemistry-mediated EV enrichment technology, i.e., EV Click Beads for immobilising TCO-labelled EVs. To confirm the expression of three EOC EV surface protein markers on EOC EVs and evaluate the performance of EV Click Beads, we employed immunogold staining to label the OVCAR3 EVs. After click chemistry mediated immobilisation of TCO-anti-FRα, TCO-anti-MSLN, and TCO-anti-TROP2 labelled OVCAR3 EVs, immunogold staining targeting CD63 (a representative EV surface marker) was performed to further validate the identity of the enriched EVs, confirming the presence of the three EOC EV surface protein markers on OVCAR3 EVs and the immobilisation of enriched EVs on the beads through TEM (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Characterisation of EOC cell line-derived EVs and linearity study of EOC EV SPRI Assay using synthetic plasma samples. (a) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of click chemistry mediated immobilisation of TCO-anti-FRα, TCO-anti-MSLN, and TCO-anti-TROP2 labelled OVCAR3 EVs, visualised by immunogold staining with anti-CD63-grafted gold nanoparticles (gold arrows). Scale bar, 100 nm. (b) Linearity study showing correlation between EV concentration and reference mRNA (i.e., MPP1 and ACTB) expression in OVCAR8 and OVCAR3 EVs. Two replicates were examined for each group. Data are presented as mean ± SD. R2 was calculated using simple linear regression. (c) Workflow for linearity study of the EOC EV SPRI Assay using synthetic plasma samples spiked with OVCAR3 EVs. The EVs were enriched using EV Click Beads in conjunction with each of the three TCO-grafted antibodies, i.e., TCO-anti-FRα, TCO-anti-MSLN, or TCO-anti-TROP2. RT-qPCR detection of the ACTB mRNA served as a surrogate for enriched OVCAR3 EV concentrations (d–i) Dynamic linearity ranges of ACTB signal for the EOC EV subpopulations enriched by TCO-grafted EOC EV-specific antibodies. Two replicates were examined for each group. Data are presented as mean ± SD. R2 was calculated using simple linear regression.

ACTB and MPP1 mRNAs serve as reliable quantitative markers for EOC EVs

Choosing appropriate reference mRNAs that are consistently present across EOC EV subpopulations is crucial. The reference genes for EOC EV quantification were selected from a cancer EV reference genes dataset47 consisting of both classical reference genes and cancer EV-specific genes, which ultimately led to the identification of MPP1 and ACTB as the top two reference genes for EOC EV quantification (Supplementary Fig. S2). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S5, both ACTB and MPP1 transcripts remained detectable after RNase treatment in pure OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 EVs, confirming that these mRNA markers are stabilised within EVs. To validate the hypothesis that quantifying EOC EV-encapsulated MPP1 and ACTB mRNAs would reflect the amount of EOC EVs, we performed a linearity analysis using two serially diluted EOC EVs. The EV amounts were quantified by NTA, and the absolute copy numbers of MPP1 and ACTB mRNAs were determined using reverse transcription digital PCR (RT-dPCR). Both reference mRNAs demonstrated robust linear correlations with EV amounts (R2 > 0.98, Fig. 3b), establishing their reliability as reference molecular markers for EOC EV quantification.

The EOC EV SPRI assay quantifies EV subpopulations with high linearity in synthetic plasma

To assess the linearity of the EOC EV SPRI Assay, we quantified the reference mRNA signals of MPP1 and ACTB within OVCAR3 EVs using synthetic plasma samples (Fig. 3c). The samples were prepared by spiking OVCAR3 EV stock solution into EV-depleted plasma from a female HD. EOC EVs in 100 μL of synthetic plasma samples were labelled with TCO-grafted antibodies specific to FRα, MSLN, or TROP2 and then enriched using EV Click Beads. The enriched OVCAR3 EVs were subjected to mRNA extraction followed by quantification of ACTB through RT-qPCR. The signal was calculated as 40—Ct value. A strong linear correlation (R2 > 0.98) between MPP1 or ACTB signal and spiked OVCAR3 EV concentrations (ranging from 4.0 × 107 to 4.0 × 1010 EV/mL, based on NTA results) was observed (Fig. 3d–i), further confirming the assay's accuracy. In comparison, HD EVs exhibited minimal expression of MPP1 and ACTB mRNAs in EOC EV SPRI Assay (Supplementary Fig. S6), demonstrating that the assay effectively distinguishes EOC EVs from those of noncancer controls.

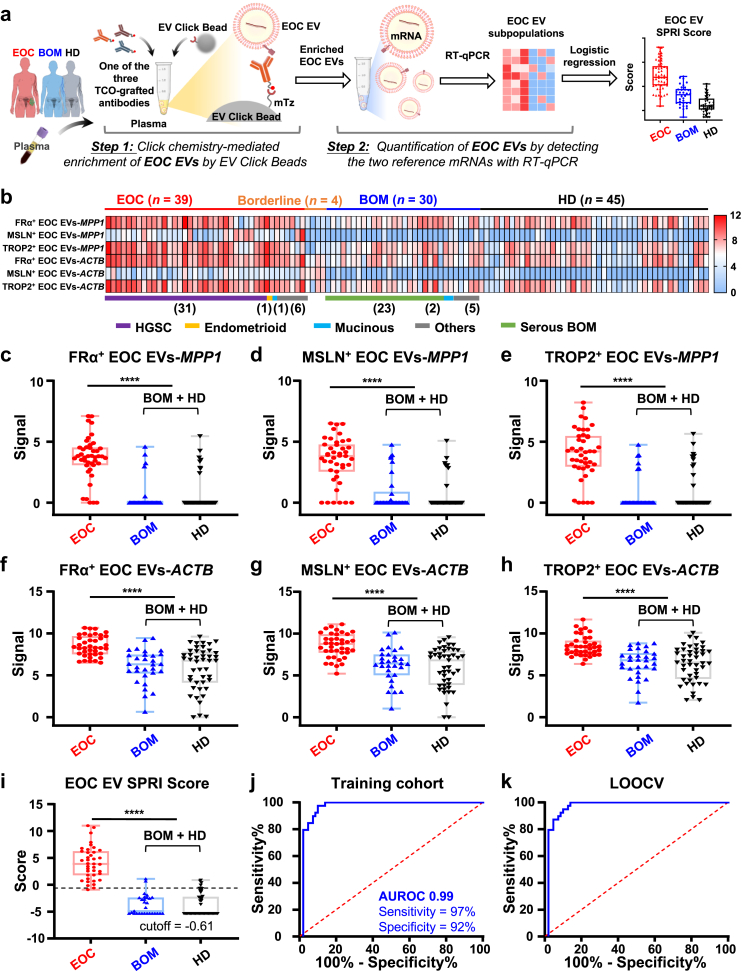

The EOC EV SPRI score accurately distinguishes EOC from controls in the training cohort

Following the validation of the linearity of the EOC EV SPRI Assay using synthetic samples, we assessed its translational potential through a phase II case–control study. The training cohort consisted of 39 patients with EOC, 4 borderline ovarian tumour cases, 30 patients with BOM, and 45 HD controls (Detailed in Supplementary Table S5). For each participant, 300 μL of plasma was subjected to the two-step EOC EV SPRI Assay that quantifies and generates the EOC EV subpopulations (i.e., FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1, FRα+ EOC EVs-ACTB, MSLN+ EOC EVs-ACTB, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-ACTB, Fig. 4a and b). Significantly elevated MPP1 or ACTB mRNA signals in each EOC EV subpopulation were detected in EOC group compared to BOM and HD groups (Fig. 4c–h). The diagnostic performance of MPP1 and ACTB in each subpopulation of EOC EVs was summarised in Supplementary Fig. S7, with AUROCs of MPP1 within the three subpopulations of EOC EVs ranging from 0.89 to 0.92 and the AUROCs of ACTB within the three subpopulations of EOC EVs ranging from 0.81 to 0.83. These results indicate that MPP1 within the three subpopulations of EOC EVs could better differentiate EOC from noncancer controls.

Fig. 4.

EOC EV SPRI Score for detecting EOC in the training cohort. (a) Workflow for the EOC EV SPRI Assay applied to plasma samples from the training cohort, which included 39 patients with EOC, 4 with borderline ovarian tumours, 30 with benign ovarian masses (BOM), and 45 healthy donors (HD). (b) Heatmaps summarising six subpopulations of EOC EVs (i.e., FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1, FRα+ EOC EVs-ACTB, MSLN+ EOC EVs-ACTB, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-ACTB) in the training cohort. (c–h) Significantly higher signals in patients with EOC compared to the combined BOM and HD control group in the training cohort were observed in the subpopulations of FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1, FRα+ EOC EVs-ACTB, MSLN+ EOC EVs-ACTB, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-ACTB. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student's t-tests). (i) The EOC EV SPRI Score was generated using a stepwise logistic regression. Significantly higher EOC EV SPRI Scores were observed in patients with EOC compared to the combined BOM and HD controls in the training cohort, with an optimal cutoff of −0.61. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student's t-test). (j) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve illustrating the diagnostic performance of EOC EV SPRI Score in distinguishing EOC from the combined BOM and HD control group in the training cohort. (k) ROC curve showing the performance of EOC EV SPRI Score after leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV).

A stepwise logistic regression model was then used to select EOC EV subpopulations for differentiating EOC from BOM and HD based on the training cohort. The EOC EV SPRI Score was generated to construct the AUROC for evaluating the diagnostic performance of the model. Among the six EOC EV subpopulations, the model selected and incorporated FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1 for generating the EOC EV SPRI Score:

The EOC EV SPRI Score demonstrated excellent performance in distinguishing patients with EOC from BOM and HD in the training cohort (Fig. 4i), with an AUROC of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97–1.00; Fig. 4j). At the optimal cut-off of −0.61, the EOC EV SPRI Score achieved a sensitivity of 97% (95% CI, 0.87–1.00) and specificity of 92% (95% CI, 0.84–0.96), with a PPV of 88% and NPV of 96% (Supplementary Table S6). LOOCV of the training cohort confirmed the robustness of the model with an AUROC of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97–1.00; Fig. 4k), sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 0.91–0.99), and specificity of 88% (95% CI, 0.79–0.94).

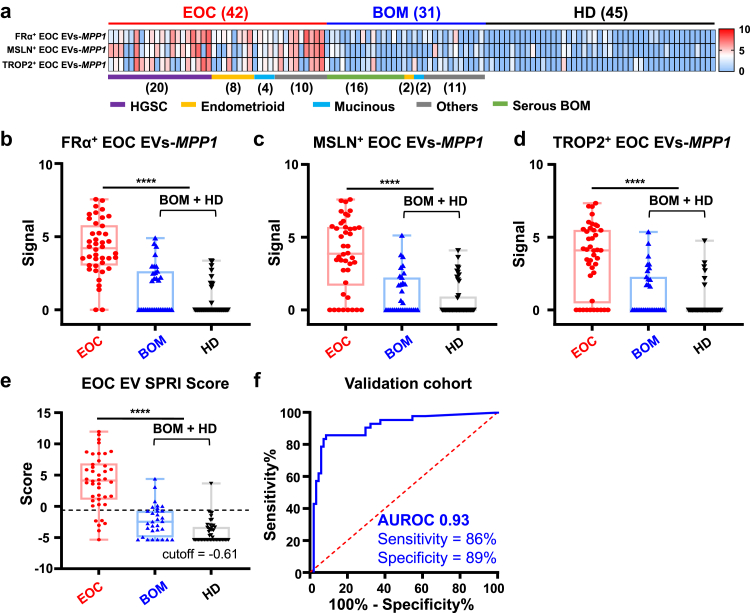

Independent validation confirms the diagnostic performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score

The diagnostic performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score was further validated using an independent validation cohort comprising 42 patients with EOC, 31 patients with BOM and 45 HD controls (Supplementary Table S5). As depicted in the heatmaps (Fig. 5a) and box plots (Fig. 5b–d), significantly higher signals from logistic regression model-selected three subpopulations of EOC EVs (i.e., FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1) were observed in the EOC cohort, compared with those from the BOM and HD controls. Applying the established logistic regression model and cutoff from the training cohort (Fig. 5e), the EOC EV SPRI Score maintained its excellent diagnostic performance in the validation cohort that effectively distinguished patients with EOC from BOM and HD controls (Fig. 5f), with an AUROC curve of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.87–0.98). The EOC EV SPRI Score demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% (95% CI, 0.54–0.81), specificity of 89% (95% CI, 0.81–0.95), PPV of 82%, and NPV of 92% (Supplementary Table S7).

Fig. 5.

EOC EV SPRI Score for distinguishing EOC from BOM and HD controls in the validation cohort. (a) Heatmaps summarising MPP1 mRNA signals across FRα+ EOC EVs, MSLN+ EOC EVs, and TROP2+ EOC EVs. (b–d) Significantly higher MPP1 mRNA signals in the subpopulations of EOC EVs were observed in patients with EOC compared to the combined BOM and HD control group. The signal is represented as 40—Ct value. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student's t-tests). (e) Boxplot illustrating EOC EV SPRI Scores in EOC versus BOM and HD controls at a cutoff of −0.61. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student's t-test). (f) ROC curve showing the diagnostic performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score in distinguishing EOC from BOM and HD.

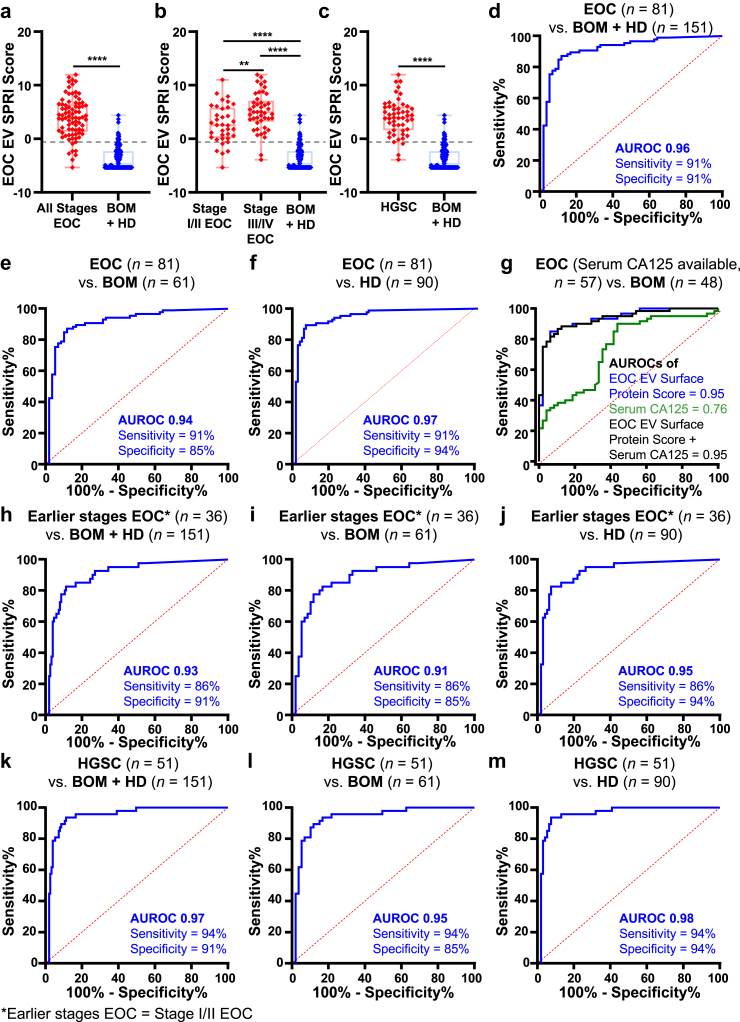

The EOC EV SPRI Score maintains high performance across clinical subgroups

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of EOC EV SPRI Score in different subgroups, we first evaluated its performance across different subgroups including all participants in the study (n = 236). Overall, the EOC EV SPRI Score of the EOC cohorts (all stages, stage I/II and stage III/IV, and HGSC) are significantly higher (p < 0.0001, unpaired Student's t tests) than that of the BOM and HD controls (Fig. 6a–c). Patients of stage III/IV also showed higher (p < 0.01, unpaired Student's t test) EOC EV SPRI Score than those of stage I/II.

Fig. 6.

Subgroup analyses of the EOC EV SPRI Score for detecting EOC across all participants. (a–c) Boxplots summarising the distribution of the EOC EV SPRI Scores across different subgroups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01 (unpaired Student's t-tests), ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student's t-tests). (d–f) ROC curves for distinguishing patients with EOC (n = 81) from the combined BOM and HD control group (n = 151), EOC (n = 81) from BOM (n = 61), and EOC (n = 81) from HD (n = 90). (g) Comparison and combination of the diagnostic performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score and serum CA125 in distinguishing EOC (n = 57) from BOM (n = 48) among participants with available CA125 data, with the EOC EV SPRI Score significantly outperforming CA-125. p < 0.001 (DeLong's test). (h–m) ROC curves for distinguishing earlier stages EOC (Stage I/II EOC, n = 36) from BOM and HD controls (n = 151), earlier stages EOC (n = 36) from BOM (n = 61), earlier stages EOC (n = 36) from HD controls (n = 90), high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC, n = 51) from BOM and HD controls (n = 151), patients with HGSC (n = 51) from BOM (n = 61), and patients with HGSC (n = 51) from HD controls (n = 90).

At the established cutoff, the EOC EV SPRI Score effectively distinguished patients with EOC (n = 81) from BOM and HD controls (n = 151), yielding an AUROC of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.89–0.97; sensitivity = 91%, specificity = 91%; Fig. 6d). Additionally, it differentiated EOC (n = 81) from BOM (n = 61) with an AUROC of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.89–0.97; sensitivity = 91%, specificity = 85%; Fig. 6e), and from HD (n = 90) with an AUROC of 0.97 (95% CI, 0.93–0.99; sensitivity = 91%, specificity = 94%; Fig. 6f). Among individuals with available serum CA125 data (n = 105, Fig. 6g), the EOC EV SPRI Score outperformed serum CA125 with AUROC of 0.95 versus 0.76 (p = 0.0001, DeLong's test) in distinguishing EOC (n = 57) from BOM (n = 48). Notably, adding serum CA125 to the model did not enhance the overall performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score, although the EOC EV SPRI Score exhibited a weak positive correlation with serum CA125 levels (r = 0.288, p = 0.026, Pearson's correlation test; Supplementary Fig. S8a).

For the subgroup of earlier stages of EOC (defined as stage I/II EOC, n = 36), the AUROC of EOC EV SPRI Score was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.88–0.98; sensitivity = 86%; specificity = 91%; Fig. 6h) for distinguishing earlier stages of EOC from BOM and HD controls. Specifically, it differentiated earlier stages of EOC (n = 36) from BOM (n = 61) with an AUROC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85–0.97; sensitivity = 86%, specificity = 85%; Fig. 6i), and from HD (n = 90) with an AUROC of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90–0.99; sensitivity = 86%, specificity = 94%; Fig. 6j). Performance of EOC EV SPRI Score for detecting patients with stage III/IV of EOC (n = 45) are also promising (AUROCs ranged from 0.96 to 0.98) and presented in Supplementary Fig. S9. In patients with the most common subtype of EOC, i.e., HGSC (n = 51), the EOC EV SPRI Score achieved an AUROC of 0.97 (95% CI, 0.87–0.97; sensitivity = 94%, specificity = 91%; Fig. 6k) for differentiating HGSC from BOM and HD controls. In addition, it differentiated HGSC (n = 51) from BOM (n = 61) with an AUROC of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.91–0.99; sensitivity = 94%, specificity = 85%; Fig. 6l), and from HD (n = 90) with an AUROC of 0.98 (95% CI, 0.95–1.00; sensitivity = 94%, specificity = 94%; Fig. 6m). For patients with non-HGSC histological subtypes (n = 30), the AUROCs ranged from 0.92 to 0.95 (Supplementary Fig. S10). These results demonstrated that the performance of the EOC EV SPRI Score remained robust across subgroups with earlier stages and advanced stages of EOC, as well as the histological subtypes of both HGSC and non-HGSC. We also checked whether the most common clinical demographic factors confound our statistical model. No significant correlations were observed between the EOC EV SPRI Score and body mass index (BMI), age or number of pregnancies (Supplementary Fig. S8b-d), indicating that these demographic factors did not confound the statistical results.

Discussion

Early detection of EOC is crucial for enabling timely interventions, thereby improving patient outcomes. Yet, the sensitivity and specificity of current diagnostic modalities for detecting early-stage EOC remain suboptimal, highlighting the need for further development of diagnostics to detect EOC early.50 Tumour EVs, which carry mRNA cargo within lipid bilayer membranes and reflect the characteristics of their originating tumour cells, present a promising biomarker for cancer diagnostics.20 EVs have been explored as potential biomarkers for early detection of EOC, showing promising diagnostic efficacy.30,31,33,34,51, 52, 53, 54 Instead of measuring the concentration of EOC EV surface proteins31,51 or quantifying colocalized surface protein markers by employing DNA-barcoded antibodies,33,34 our EOC EV SPRI Assay enriches all types of EVs expressing the corresponding surface markers regardless of their size or biogenesis and measures stably expressed reference mRNAs within EOC EVs using routine RT-qPCR, which offers advantages such as rapid processing, user-friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and a minimal plasma requirement (100-μL per marker). The EOC EV SPRI Score derived from this assay demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance to distinguish EOC from BOM and HD controls, achieving an AUROC of 0.99 in the training cohort and 0.93 in the validation cohort. This surpassed the performance of serum CA125 in the same study cohort.6 Notably, the EOC EV SPRI Score maintained its excellent performance in the earlier stages (stage I/II) of EOC with AUROC of 0.93, and in the subgroup of HGSC with AUROC of 0.97.

In comparison to the current EV-based EOC detection methods,30,33,55, 56, 57, 58, 59 this two-step EOC EV SPRI Assay demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in detecting patients with EOC (Detailed in Supplementary Table S8), offering practical advantages including cost-efficiency (<$7 for materials and reagents cost per patient), rapid turnaround time (<3 h), and minimal sample handling requirements (Supplementary Fig. S11). The first step of the assay involves biorthogonal click chemistry-mediated EV enrichment, which enables a rapid, specific, and irreversible ligation between mTz-grafted EV Click Beads and TCO-grafted EVs.60 This mechanism ensures efficient immobilisation of tumour EVs on the EV Click Beads, enhancing capture sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional EV isolation methods24,26,61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 (detailed in Supplementary Table S9). Additionally, we incorporated three complementary surface protein markers (i.e., FRα, MSLN, and TROP2) to enrich a broad spectrum of EOC specific EVs, which can cover the heterogeneity of EOC EVs. The three EOC EV surface protein markers were selected via a rigorous bioinformatic framework to minimise background signals from immune cells while prioritising EOC-specific druggable targets. EOC TMA validation confirmed that these three surface protein markers are complementary and can be used synergistically, with 97.6% of EOC tissue samples expressing at least one of the three markers. Additionally, the complementary characteristic of these markers could be further demonstrated by the diagnostic performance. Each of the EOC EV subpopulations achieved an AUROC of 0.92, 0.89, and 0.90 respectively, when these three subpopulations are combined in the EOC EV SPRI Score, the AUROC increased to 0.99, with a significantly enhanced sensitivity (97%) and specificity (92%).

The second step of the assay introduced a convenient and sensitive method for quantifying EOC EV subpopulations by measuring reference mRNAs within these EVs, allowing for accurate quantification of the EOC EV subpopulations. This approach capitalises on the stability of mRNA within EVs, as the encapsulating membrane protects these transcripts from degradation, whereas mRNAs outside of EVs lack such protection and are less likely to be enriched or detected in our assay.67,68 In this study, ACTB and MPP1 were selected as reference mRNAs through a bioinformatic pipeline for EOC EV quantification. Experimental results demonstrated a strong linear correlation between these mRNA signals and overall EV concentration. Thus, the detection of ACTB and MPP1 mRNA using RT-qPCR provides an accurate reflection of EV amounts. Moreover, our study revealed that MPP1 mRNA signals within EOC EVs exhibited greater differential ability between EOC and noncancer controls compared to ACTB. The stepwise logistic regression analysis also selected and incorporated FRα+ EOC EVs-MPP1, MSLN+ EOC EVs-MPP1, and TROP2+ EOC EVs-MPP1 in the model for generating the EOC EV SPRI Score.

EOC EVs are heterogeneous, exhibiting variability in genetic, molecular, and histological characteristics both within individual tumours and across patients.69,70 Despite this heterogeneity, the EOC EV SPRI Score maintained high diagnostic performance across subgroups stratified by disease stages and histological subtypes. Specifically, our cohort encompassed not only HGSC, the most common subtype of EOC, but also less prevalent subtypes such as mucinous and endometrioid, where the EOC EV SPRI Score also demonstrated good diagnostic performance. Particularly in the earlier stages of EOC (stage I/II), the EOC EV SPRI Score showed excellent diagnostic performance, achieving an AUROC of 0.91 in distinguishing earlier stages of EOC from BOM. These findings highlight the broad applicability of the assay across diverse EOC subgroups.

Admittedly, several limitations still exist in this study. Firstly, some risk factors in ovarian cancer, such as family history and BRCA gene mutation status,71 were not assessed due to the data unavailability. Secondly, as the patients with EOC in this study were diagnosed using existing surveillance methods prior to enrolment, direct comparisons between the EOC EV SPRI Score and established diagnostic modalities such as serum CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), were challenging. Nevertheless, this study includes a preliminary comparison between the EOC EV SPRI Score and serum CA125 to provide initial insights.

In conclusion, the EOC EV SPRI Assay is a sensitive and specific noninvasive approach for distinguishing EOC from the BOM and HD controls. Moreover, its performance remained excellent in earlier stages of EOC (stage I/II, AUROC = 0.93) and in the most common histological subtype, HGSC (AUROC = 0.97). The diagnostic performance of this assay outperformed that of serum CA125 in the same study cohort, demonstrating significant promise in identifying EOC at a curable stage and potentially improving long-term patient outcomes. Future studies involving larger, multicentre cohorts will be essential to further validate its clinical utility and potential for widespread implementation.

Contributors

Conceptualisation: HRT, Y Zhu; Data curation: RYZ, HRT, Y Zhu; Formal Analysis: YTY, CZ, TG, HK, YRJ, JK, RYZ, YJ, JL, HRT, Y Zhu; Funding acquisition: HRT, Y Zhu, NS; Investigation: YTY, LQ, YM, JK, NK, JP, JL, RYZ, JS, BR, GAD, LBJA, SM, KL, JW, SY, MSS, SL, HRT, Y Zhu; Methodology: NK, YRJ, CZ, JL, HRT, Y Zhu; Project administration: HRT, Y Zhu; Resources: JW, NS, KL, SM, HRT, Y Zhang, SZ, JR, HL, YY, YC, WZ, GW; Software: JL, CZ; Supervision: HRT, Y Zhu, NS; Validation: TG, JK, Zhili W, JR, YC, WZ, RP, HL, Zihan W, YY, GW, JW, NS; Visualisation: YTY, CZ, AW, JZY, QH, VXZ, HRT, Y Zhu; Writing—original draft: YTY, CZ, AW, JZY, LLZ, JLS, JW, NL, VXZ, AQ, AK; Writing—review & editing: BYK, HRT, and Y Zhu. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (OPR), upon reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

HRT is a co-founder and shareholder in Cytolumina Technologies Corp, Pulsar Therapeutics, and Eximius Diagnostics Corp. Y Zhu is a co-founder and shareholder in Eximius Diagnostics Corp.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (R01CA277530, R01CA255727, R01CA253651, R01CA253651-04S1, R21CA280444, R01CA246304, U01EB026421, R44CA288163, U01CA271887, and U01CA230705), DOD (HT9425-23-1-0361) and OCRA (CRDG-2023-3-1000) for the U.S. study. Additionally, we acknowledge the support of the Science and Technology Foundation of Suzhou (SZS2023006, SSD2023004) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2023335) for the work conducted at SINANO. The funders had no role in the collection of data; the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Some specimen collection for the U.S. study was supported by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre. We thank Lucy Ruoxi Shi and Icy Liang for their design and creation of the cartoon illustration for this project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105884.

Contributor Information

Shaohua Lu, Email: lu.shaohua@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Jipeng Wan, Email: wanjipeng@sdfmu.edu.cn.

Na Sun, Email: nsun2013@sinano.ac.cn.

Hsian-Rong Tseng, Email: hrtseng@mednet.ucla.edu.

Yazhen Zhu, Email: yazhenzhu@mednet.ucla.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lheureux S., Gourley C., Vergote I., Oza A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1240–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lheureux S., Braunstein M., Oza A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer: evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(4):280–304. doi: 10.3322/caac.21559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuroki L., Guntupalli S.R. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M., Cheng S., Jin Y., Zhao Y., Wang Y. Roles of CA125 in diagnosis, prediction, and oncogenesis of ovarian cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1875(2) doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai G., Huang F., Gao Y., et al. Artificial intelligence-based models enabling accurate diagnosis of ovarian cancer using laboratory tests in China: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health. 2024;6(3):e176–e186. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali F.T., Soliman R.M., Hassan N.S., et al. Sensitivity and specificity of microRNA-204, CA125, and CA19.9 as biomarkers for diagnosis of ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2022;17(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lentz S.E., Powell C.B., Haque R., et al. Development of a longitudinal two-biomarker algorithm for early detection of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159(3):804–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueland F.R., Desimone C.P., Seamon L.G., et al. Effectiveness of a multivariate index assay in the preoperative assessment of ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1289–1297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821b5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman R.L., Herzog T.J., Chan D.W., et al. Validation of a second-generation multivariate index assay for malignancy risk of adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):82.e1-.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shulman L.P., Francis M., Bullock R., Pappas T. Clinical performance comparison of two In-Vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays (IVDMIAs) for presurgical assessment for ovarian cancer risk. Adv Ther. 2019;36(9):2402–2413. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore R.G., McMeekin D.S., Brown A.K., et al. A novel multiple marker bioassay utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore R.G., Brown A.K., Miller M.C., et al. The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(2):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss E., Taylor A., Andreou A., et al. British gynaecological cancer society (BGCS) ovarian, tubal and primary peritoneal cancer guidelines: recommendations for practice update 2024. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;300:69–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raposo G., Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revenfeld A.L.S., Bæk R., Nielsen M.H., Stensballe A., Varming K., Jørgensen M. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of extracellular vesicles in peripheral blood. Clin Ther. 2014;36(6):830–846. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiklander O.P.B., Brennan M.A., Lotvall J., Breakefield X.O., El Andaloussi S. Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(492) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav8521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Niel G., D'Angelo G., Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu D., Li Y., Wang M., et al. Exosomes as a new frontier of cancer liquid biopsy. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng B., Wang J., Zhang R.Y., et al. Click chemistry-mediated enrichment of circulating tumor cells and tumor-derived extracellular vesicles for dual liquid biopsy in differentiated thyroid cancer. Nano Today. 2024;58 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji Y.R., Lee J., Kim H., et al. Noninvasive assessment of protease activity in osteosarcoma via click chemistry-mediated enrichment of extracellular vesicles. Adv Funct Mater. 2025 doi: 10.1002/adfm.202422469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ju Y., Watson J., Wang J.J., et al. B7-H3-liquid biopsy for the characterization and monitoring of the dynamic biology of prostate cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;79 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2025.101207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun N., Zhang C., Lee Y.T., et al. HCC EV ECG score: an extracellular vesicle-based protein assay for detection of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77(3):774–788. doi: 10.1002/hep.32692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao C., Lee Y.T., Melehy A., et al. Extracellular vesicle digital scoring assay for assessment of treatment responses in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s13046-025-03379-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao C., Wang Z., Kim H., et al. Identification of tumor-specific surface proteins enables quantification of extracellular vesicle subtypes for early detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025 doi: 10.1002/advs.202414982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clancy J.W., D'Souza-Schorey C. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles: multifunctional entities in the tumor microenvironment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:205–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031521-022116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maas S.L.N., Breakefield X.O., Weaver A.M. Extracellular vesicles: unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(3):172–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian K., Fu W., Li T., Zhao J., Lei C., Hu S. The roles of small extracellular vesicles in cancer and immune regulation and translational potential in cancer therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):286. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoi A., Ukai M., Yasui T., et al. Identifying high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma-specific extracellular vesicles by polyketone-coated nanowires. Sci Adv. 2023;9(27) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P., Zhou X., He M., et al. Ultrasensitive detection of circulating exosomes with a 3D-nanopatterned microfluidic chip. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019;3(6):438–451. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerabkova-Roda K., Dupas A., Osmani N., Hyenne V., Goetz J.G. Circulating extracellular vesicles and tumor cells: sticky partners in metastasis. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(10):799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salem D.P., Bortolin L.T., Gusenleitner D., et al. Colocalization of cancer-associated biomarkers on single extracellular vesicles for early detection of cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2024;26(12):1109–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2024.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winn-Deen E.S., Bortolin L.T., Gusenleitner D., et al. Improving specificity for ovarian cancer screening using a novel extracellular vesicle-based blood test: performance in a training and verification cohort. J Mol Diagn. 2024;26(12):1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2024.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong J., Zhang R.Y., Sun N., et al. Bio-inspired NanoVilli chips for enhanced capture of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles: toward non-invasive detection of gene alterations in non-small cell lung cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(15):13973–13983. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b01406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bracht J.W.P., Gimenez-Capitan A., Huang C.Y., et al. Analysis of extracellular vesicle mRNA derived from plasma using the nCounter platform. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3712. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83132-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han Z.W., Wan F.N., Deng J.Q., et al. Ultrasensitive detection of mRNA in extracellular vesicles using DNA tetrahedron-based thermophoretic assay. Nano Today. 2021;38 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nusinow D.P., Szpyt J., Ghandi M., et al. Quantitative proteomics of the cancer cell line encyclopedia. Cell. 2020;180(2):387–402.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H., Liu T., Zhang Z., et al. Integrated proteogenomic characterization of human high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cell. 2016;166(3):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jo J., Choi S., Oh J., et al. Conventionally used reference genes are not outstanding for normalization of gene expression in human cancer research. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20(Suppl 10):245. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2809-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenberg E., Levanon E.Y. Human housekeeping genes, revisited. Trends Genet. 2013;29(10):569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Z., Yuan J., Long M., et al. The cancer surfaceome atlas integrates genomic, functional and drug response data to identify actionable targets. Nat Cancer. 2021;2(12):1406–1422. doi: 10.1038/s43018-021-00282-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pathan M., Fonseka P., Chitti S.V., et al. Vesiclepedia 2019: a compendium of RNA, proteins, lipids and metabolites in extracellular vesicles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D516–D519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalra H., Simpson R.J., Ji H., et al. Vesiclepedia: a compendium for extracellular vesicles with continuous community annotation. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ochoa D., Hercules A., Carmona M., et al. The next-generation open targets platform: reimagined, redesigned, rebuilt. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;51(D1):D1353–D1359. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novershtern N., Subramanian A., Lawton L.N., et al. Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell. 2011;144(2):296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dai Y., Cao Y., Kohler J., Lu A., Xu S., Wang H. Unbiased RNA-Seq-driven identification and validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR analyses of pooled cancer exosomes. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07318-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandimalla R., Wang W., Yu F., et al. OCaMIR—A noninvasive, diagnostic signature for early-stage ovarian cancer: a multi-cohort retrospective and prospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(15):4277–4286. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welsh J.A., Goberdhan D.C.I., O'Driscoll L., et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024;13(2) doi: 10.1002/jev2.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao Y., Bi M., Guo H., Li M. Multi-omics approaches for biomarker discovery in early ovarian cancer diagnosis. eBioMedicine. 2022;79 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hinestrosa J.P., Kurzrock R., Lewis J.M., et al. Early-stage multi-cancer detection using an extracellular vesicle protein-based blood test. Commun Med (Lond) 2022;2:29. doi: 10.1038/s43856-022-00088-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jo A., Green A., Medina J.E., et al. Inaugurating high-throughput profiling of extracellular vesicles for earlier ovarian cancer detection. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023;10(27) doi: 10.1002/advs.202301930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trinidad C.V., Pathak H.B., Cheng S., et al. Lineage specific extracellular vesicle-associated protein biomarkers for the early detection of high grade serous ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper T.T., Dieters-Castator D.Z., Liu J., et al. Targeted proteomics of plasma extracellular vesicles uncovers MUC1 as combinatorial biomarker for the early detection of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2024;17(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s13048-024-01471-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi M., Sawada K., Nakamura K., et al. Exosomal miR-1290 is a potential biomarker of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and can discriminate patients from those with malignancies of other histological types. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0458-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai H., Guo Y., Tian L., et al. Protein panel of serum-derived small extracellular vesicles for the screening and diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(15) doi: 10.3390/cancers14153719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J., Li Y., Li Q., et al. An aptamer-based nanoflow cytometry method for the molecular detection and classification of ovarian cancers through profiling of tumor markers on small extracellular vesicles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2024;63(4) doi: 10.1002/anie.202314262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meng X., Muller V., Milde-Langosch K., Trillsch F., Pantel K., Schwarzenbach H. Diagnostic and prognostic relevance of circulating exosomal miR-373, miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):16923–16935. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou J., Gong G., Tan H., et al. Urinary microRNA-30a-5p is a potential biomarker for ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(6):2915–2923. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karver M.R., Weissleder R., Hilderbrand S.A. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of 1,2,4,5-tetrazines for bioorthogonal conjugation. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22(11):2263–2270. doi: 10.1021/bc200295y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian Y., Gong M., Hu Y., et al. Quality and efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation methods by nano-flow cytometry. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1) doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1697028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun N., Lee Y.T., Zhang R.Y., et al. Purification of HCC-Specific extracellular vesicles on nanosubstrates for early HCC detection by digital scoring. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4489. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bellotti C., Lang K., Kuplennik N., Sosnik A., Steinfeld R. High-grade extracellular vesicles preparation by combined size-exclusion and affinity chromatography. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90022-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brennan K., Martin K., FitzGerald S.P., et al. A comparison of methods for the isolation and separation of extracellular vesicles from protein and lipid particles in human serum. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1039. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57497-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Konoshenko M.Y., Lekchnov E.A., Vlassov A.V., Laktionov P.P. Isolation of extracellular vesicles: general methodologies and latest trends. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8545347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tauro B.J., Greening D.W., Mathias R.A., et al. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods. 2012;56(2):293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Brien K., Breyne K., Ughetto S., Laurent L.C., Breakefield X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(10):585–606. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0251-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirian R.D., Steinman D., Jewell C.M., Zierden H.C. Extracellular vesicles as carriers of mRNA: opportunities and challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Theranostics. 2024;14(5):2265–2289. doi: 10.7150/thno.93115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pieretti M., Hopenhayn-Rich C., Khattar N.H., Cao Y., Huang B., Tucker T.C. Heterogeneity of ovarian cancer: relationships among histological group, stage of disease, tumor markers, patient characteristics, and survival. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(1):11–23. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee S., Zhao L., Rojas C., et al. Molecular analysis of clinically defined subsets of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cell Rep. 2020;31(2) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.George A., Kaye S., Banerjee S. Delivering widespread BRCA testing and PARP inhibition to patients with ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(5):284–296. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.