Abstract

Casein (CS) gels, valued for their functional properties, are widely utilized in food applications. In this study, CS sol/gels were prepared by citric acid and heat (85 °C) induction at varying pH values and protein concentrations, and their physicochemical properties and in vitro digestion characteristics were further evaluated in order to explore the gel mechanism and the potential application in controlled release of roselle anthocyanins (RA). Stable CS gels formed only at pH 2.0 and protein concentrations ≥12 %, attributed to high solubility and ζ-potential. Moreover, hydrophobic interactions and ionic bonds were the main driving forces. In addition, the CS gel effectively enabled RA controlled release, achieving intestinal release rates of 76.58 % ∼ 83.47 %. but RA reduced the protein digestibility of CS gel by approximately 10 %. These findings provide a theoretical foundation for CS gel developments and applications in functional food.

Keywords: Casein sol/gel, Physicochemical properties, In vitro digestion

Highlights

-

•

Casein gel can achieve controlled release of roselle anthocyanin.

-

•

Hydrophobic interactions and ionic bonds were the main driving forces

-

•

pH and protein concentration affected the formation of casein gel.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, protein-based hydrogels have garnered significant research interest. Compared with synthetic polymers, they not only offer nutritional value, biocompatibility, and biodegradability but also provide adjustable mechanical properties and non-toxicity (Yang et al., 2024). Casein (CS), the predominant milk protein (accounting for ∼80 % of total milk proteins), is widely utilized in the food industry owing to its high nutritional value and diverse functional properties (Yang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2020). Structurally, CS consists of four major subunits: αS1-, αS2-, β-, and κ-CS, which have a molar ratio of 11:3:10:4, respectively (Nascimento et al., 2020). Due to the high content of phosphorylated residues in CS molecules and in the presence of non-covalent interactions, these molecules gradually self-assemble to form CS micelles (Broyard & Gaucheron, 2015). As a result, the unique micellar structure gives CS many processing properties (such as gelation ability), while modulation of processing conditions allows customization for functional applications (Liao et al., 2024).

Currently, CS gels are primarily prepared via enzymatic, physical, or chemical methods, all of which involve disrupting the native protein structure and inducing cross-linking to form a water-retaining 3D network (Yang et al., 2024). Notably, temperature and pH are crucial factors affecting the preparation of CS gels. Heating promotes protein denaturation, thereby exposing hydrophobic residues and enabling disulfide bond exchange (Francis et al., 2016). Conversely, pH adjustments alter the micelle stability by modulating the net charge of the protein (Pougher et al., 2024).

At present, numerous studies have demonstrated that both high acidification temperature (≥ 60 °C) and acid type significantly influence the formation and structure of milk protein gels or CS micelles. Laursen et al. (2023) reported that citric acid-induced milk gels prepared at 75 °C and 90 °C exhibited a denser structure and good cooking integrity. Recently, Cheng et al. (2025) also found that the milk gel prepared by citric acid at 90 °C had higher hardness and cohesiveness than that made by lactic acid or hydrochloric acid. Additionally, colloidal calcium phosphate dissociated at pH 2.0–3.0, which affected the size and solubility of CS micelles (Choi & Zhong, 2020; Choi & Zhong, 2021; Liu & Guo, 2008). More importantly, citric acid increased the CS micelle hydrodynamic diameter at pH 3.0, while hydrochloric acid and gluconic acid decrease hydrodynamic diameter (Choi et al., 2021).

However, previous researches on heat and acid-induced CS gels primarily focused on lower temperatures (30 °C ∼ 60 °C) and pH > pI (4.6), often using glucono-δ-lactone as a slow acid-release agent (Cheng et al., 2025; Velazquez-Dominguez et al., 2023). Consequently, studies on citric acid-induced CS gels under high-temperature conditions remain scarce. Additionally, CS-polyphenol interactions are extensively employed in food science to enhance polyphenol bioavailability (Liao et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the effect of CS-polyphenol interactions on protein digestibility remains controversial. For instance, covalent grafting with kaempferol and quercetin significantly reduced the digestibility of CS, whereas interaction with chlorogenic acid effectively enhanced CS digestibility (Jiang et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2022). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to develop CS sol/gels induced by citric acid and heat at different pH (2.0–4.0) and different protein concentrations (9 %–21 %, w/v), then the gel properties and mechanism were investigated from the aspects of appearance, ζ- potential, chemical force and texture characteristics, and further the protein digestibility and controlled release performance of CS gels loaded with roselle anthocyanin (RA) were evaluated. This study will provide new perspectives in the development of CS gels induced by citric acid and heat, and contribute to the design of anthocyanin-rich products.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

RA was sourced from Shanxi Baichuan Biotechnology Co., LTD (Shanxi, China). CS, trypsin (≥100 U/mg), pepsin (≥250 U/mg) and 1, 1-diphenyl-2-trinitrophenylhydrazine (DPPH) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Urea was provided by Guangzhou Saiguo Biotechnology Co., LTD (Guangdong, China). O-Phenylendiamine (OPA) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Reagent Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). Dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium tetraborate and l-serine were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). Bradford protein detection kit was acquired from Shanghai Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., ltd. (Shanghai, China). The other analytical reagents were provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation of CS and CS-RA sol/gel at different pHs and CS concentrations

CS powder was weighed at 1.35, 1.80, 2.25, 2.70 and 3.15 g, respectively. The same weight of CS powder was dissolved in a buffer of citric acid - Na₂HPO4 at different pH (in which the pH 2.0- pH 2.4 pH buffers were further adjusted by adding a small amount of dilute HCl), and the final volume was 15 mL. Then, the mixed solution was dispersed for 5 min with a shear mixer, so CS solutions with different pH values (pH 2.0, pH 2.4, pH 2.8, pH 3.2, pH 3.6, and pH 4.0) and different protein concentrations (9 %, 12 %, 15 %, 18 %, and 21 %, w/v) were obtained. Next, 45 mg of RA powder was weighed and dispersed into the CS solution to prepare a CS-RA solution with a final RA concentration of 3 mg/mL. Subsequently, the CS solution and CS-RA solution were put into 20 mL clear glass bottles respectively, and hydrated in a refrigerator at 4 °C overnight. Finally, the glass bottle containing the CS-RA solution was heated in a water bath at 85 °C for 30 min (with the water level above the solution surface), then rapidly cooled in ice water to form CS and CS-RA solution/gel.

2.3. Appearance of CS and CS-RA sol/gel determination

All samples were placed against a black background and photographed from the front of the glass bottle. Moreover, based on the physical state of the samples in the bottle, they were classified into four categories: flowing sol, non-flowing uniform gel, non-flowing porous gel, and protein precipitation with dehydration shrinkage. These observations were then used to construct the state diagram of CS and CS-RA sol/gel systems.

2.4. ζ- potential of CS and CS-RA solution determination

CS powder was dissolved in citric acid- Na₂HPO₄ buffers at pH 2.0, pH 2.4, pH 2.8, pH 3.2, pH 3.6 and pH 4.0 respectively to obtain CS solution with a concentration of 2 mg/mL. Subsequently, the CS-RA solution was obtained by dispersing RA powder into the CS solutions of varying pH, with the final RA concentration adjusted to 2 mg/mL. All CS and CS-RA solutions were placed on a black background and photographed on the front of the glass bottle. Following a 50-fold dilution, the ζ-potential of each sample was measured at 25 °C using a Malvern particle analyzer (Nano Es90, Malvern, UK).

2.5. Chemical force of CS and CS-RA sol/gel determination

The chemical interactions stabilizing the sol/gel samples were analyzed according to the method of Jia et al. (2016). Briefly, each CS and CS-RA sol/gel sample was divided into four aliquots (approximately 500 mg each) and transferred into 50 mL centrifuge tubes. Subsequently, the samples were individually dissolved in 10 mL of the following solutions: 0.05 M NaCl solution (SA), 0.6 M NaCl solution (SB), 0.6 M NaCl+1.5 M urea solution (SC) and 0.6 M NaCl+8 M urea solution (SD). After vigorous shaking for 2 min, the dissolved samples were incubated at 4 °C for 60 min, followed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm/min for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using a Bradford protein assay kit (Bradford, 1976). The contribution of each force was calculated according to the following Eqs. (1–3):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where SSA, SSB, SSC and SSD are the protein concentrations of the sample dissolved in SA, SB, SC and SD, respectively.

2.6. Texture characteristics of CS and CS-RA sol/gel determination

The texture characteristics analysis of stable CS and CS-RA sol/gel was referred to the method of Fei et al. (2024). Texture profile analysis (TPA) was performed using a texture analyzer (TA.XTplusC, Surface Measurement Systems, UK) equipped with a P/0.5 probe. Detailed parameters were set as follows: trigger force was 5 g, compression ratio was 50 %, test interval was 5 s, pre-test rate, test rate and post-test rate were both 1 mm/s.

2.7. In vitro simulated digestion of CS and CS-RA sol/gel determination

2.7.1. Degree hydrolysis (DH) of protein

The stable CS and CS-RA sol/gel samples were weighed at 1200, 1000, 800, 650 and 500 mg respectively at the protein concentration of 9 %, 12 %, 15 %, 18 % and 21 % (w/v), so that the CS content of each sample was 100 mg. At the same time, 100 mg of CS powder was weighed as the control group. All samples were added to 20 mL of dilute HCl solution with pH 2.5 at 0.05 mg/mL of gastric protein and oscillated uniformly. The mixed solution was incubated in a gas bath thermostatic oscillator at 37 °C with 90 rpm shaking. At specified time intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min), 1 mL aliquots of digestive fluid were collected and mixed with an equal volume of 0.1 M NaOH solution. At the end of the gastric digestion phase, the remaining digestive fluid was adjusted to pH 7.0 with 1 M of NaOH solution, and trypsin was added to bring its final concentration to 0.04 mg/mL. Then all digestive solutions were incubated in a water bath thermostatic oscillator (90 rpm, 37 °C), and 1 mL of digestive solution was taken at 30, 60, and 90 min, respectively. All the above samples were immediately heated to deactivate enzyme activity, and centrifuged at 6000 rpm/min for 10 min, and the supernatant was taken for use.

The content of free amino groups was determined by OPA method with reference to Nielsen et al. (2006), and the DH was further calculated. Sodium tetraborate (7.62 g) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (200 mg) were dissolved fully in 150 mL of deionized water, while OPA was dissolved in 4 mL of ethanol solution and transferred to the previous solution. Then, dithiothreitol (176 mg) was added to the mixed solution and fully stirred to dissolve, and then deionized water was added until 200 mL to obtain OPA reagent. In addition, 50 mg of serine was dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water to obtain a serine standard solution, while serine-NH2 was about 0.9516 meqv/L.

The digestive fluid of gastric and intestinal digestion stages was diluted 5 and 10 times, respectively, and then 25 μL sample was mixed with 175 μL OPA reagent or deionized water. After the exact reaction for 2 min, the absorbance value of the mixed solution was measured at 340 nm using the microplate reader (Ensight tm, PerkinElmer, USA). The DH of the protein in each digestive fluid was calculated according to the following Eqs. (4–6):

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where X*P represents the protein content in the sample, which is 0.05 × 0.9 in this experiment; the α, β and htot values of CS were 1.039, 0.383 and 8.2, respectively; h’ and h0 are the number of peptide bonds hydrolyzed in each digestion stage and the number of peptide bonds hydrolyzed in the initial stage, respectively.

2.7.2. Release rate of RA

The measured samples in the middle gastric and intestinal digestion stages of section 3.2.6 were diluted 2 and 4 times, respectively, and RA solutions with concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/mL were prepared. According to the experimental method of Zheng et al. (2024), the scavenging ability of the above-mentioned diluent and RA solution for DPPH free radicals was determined with a slight modification. The 100 μL diluent or RA solution was mixed with 100 μL DPPH and 100 μL pure water, respectively. The absorbance of each mixed solution at 517 nm was measured by microplate reader after 30 min light avoidance reaction. The eq. (7) for calculating DPPH free radical clearance of sample solution or RA were as follows:

| (7) |

where A0 is the absorbance of DPPH and deionized water; A1 indicates the absorbance of DPPH with the sample or RA solution; A2 represents the absorbance of the sample or RA solution with deionized water.

With different RA concentrations as horizontal coordinates and DPPH free radical clearance as vertical coordinates, the standard curve of DPPH free radical clearance of RA was calculated (Supplementary Fig. 1). In particular, the difference of DPPH free radical clearance between CS-RA sol/gel and CS sol/gel was the actual DPPH free radical clearance of RA released during digestion. Finally, the actual concentration of RA was calculated according to the standard curve, and the ratio of it to the theoretical concentration was the release rate of RA at each digestion stage.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were measured at least three times. SPSS Statistics 27 and Origin 2021 were used for statistical analysis and mapping of experimental data. Univariate analysis of variance and Duncan's multiple comparison method were used to analyze the experimental data, with a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Appearance of CS and CS-RA sol/gel analysis

As shown in Fig. 1, when the pH was 2.0, the CS sol/gel with a protein concentration of 9 % (w/v) exhibited a uniform and flowable sol state. In contrast, at higher protein concentrations (12 % ∼ 15 %, w/v), the CS sol/gel transitioned to a uniform, fine, and non-flowing gel state. Further increasing the concentration to 18 % ∼ 21 % (w/v) resulted in a heterogeneous, rough, and non-flowing porous gel state. This behavior may be attributed to the fact that only when the CS concentration exceeded a critical threshold (12 %, w/w) could heat-treated CS form large aggregates and ultimately gels (Chen et al., 2021). When the pH reached 2.4, only the 9 % (w/v) protein concentration CS sol/gel maintained a homogeneous and flowable sol state, whereas precipitation occurred at all other protein concentrations. Moreover, when the pH exceeded 2.4, none of the CS sol/gel samples formed stable sols or gels, instead exhibiting clear solid-liquid phase separation. This phenomenon may be attributed to the pH-dependent behavior of CS molecules: as the pH approaches the isoelectric point (pI ≈ 4.6), the net charge of CS molecules decreases, promoting aggregation and precipitation, thereby destabilizing the sol/gel system (Liu et al., 2008). Notably, while Tang et al. (2024) reported that HCl-acidified CS gels (pH 3.0) exhibited favorable gel properties, our study revealed that citric-acidified CS molecules lost gelling ability above pH 2.4. This contrast further suggests that the acid type critically influences CS behavior. Additionally, the performance states of all CS-RA sol/gel at different pH values and different protein concentrations were consistent with that of CS sol/gel, which meant that the addition of RA had little influence on the force between CS molecules.

Fig. 1.

The appearance characteristics (A) and state diagram (B) of CS and CS-RA sol/gel at different pHs and protein concentrations.

3.2. Ζ- potential of CS and CS-RA solution analysis

As can be seen from Fig. 2 (A), the turbidity of CS and CA-RA solutions varied significantly with increasing pH. At pH 2.0, both solutions remained clear and transparent, whereas obvious precipitation occurred at pH ≥ 2.4, with large aggregates observed in the sediments at pH ≥ 2.8. Generally, within the pH range of 2.0–3.0, CS molecules form open fractal structures through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and cation-π interactions (due to their distance from the pI), resulting in reduced system turbidity (Velazquez-Dominguez et al., 2023). However, the acid type influenced the hydrodynamic diameter of CS micelles: citric acid was reported to increase the hydrodynamic diameter of CS dispersions (Choi et al., 2021). Thus, the observed precipitation may be attributed to citric acid-induced expansion of CS molecular hydrodynamic diameter, promoting the precipitation of CS and CS-RA solutions at low pH.

Fig. 2.

The appearance (A) and ζ- potential (B) of CS and CS-RA solution with different pHs.

In addition, as shown in Fig. 2 (B), pH value had a significant effect on the ζ- potential value of CS and CA-RA solutions (p < 0.05), indicating that the absolute value of ζ-potential first decreased and then increased with the increase of pH value. Notably, at pH ≤ 2.4, both CS and CS-RA solutions carried positive charges, with high absolute ζ-potential values (8.53–15.03 mV and 10.54–20.93 mV, respectively). In contrast, at pH ≥ 2.8, the solutions became negatively charged, showing lower absolute ζ-potential values (0.57–2.89 mV and 1.94–3.98 mV, respectively). These results suggest that the pI of CS and CS-RA lies between pH 2.4 and pH 2.8. Post et al. (2012) found that the pI of CS micelles dissolved in dilute HCl was pH 4.6, and the ζ-potential was about +30 mV at pH 2.0 ∼ pH 3.5, while the ζ-potential dropped linearly at pH 3.5 ∼ pH 5.5. It was inferred that the ζ-potential and pI of CS molecule were related to the type of acidifier, and citric acid could reduce the ζ-potential and pI of CS molecule. Although the ζ-potential of CS-RA was slightly higher than that of CS alone, the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The reason may be that at acidic pH, RA solution was mainly composed of yellow salt cations with positive charge, and the increase of pH value caused its structure to be destroyed, further leading its charge to change from positive to negative, and the charge number showed a trend of decreasing first and then increasing (Huang et al., 2023).

Collectively, higher ζ-potential values correlated with enhanced solubility for both CS and CS-RA solutions, aligning with Post et al. (2012). This phenomenon was attributed to the fact that particles with a high ζ-potential inhibited coalescence and enhanced self-stability through charge (Morrison & Ross, 2002). Furthermore, since protein gelation strongly depends on solubility, systems capable of forming soluble protein aggregates typically develop more robust gel networks (Tiong et al., 2024).

3.3. Chemical interactions of CS and CS-RA sol/gel analysis

The chemical forces stabilizing CS and CS-RA sol/gel (pH 2.0) at varying protein concentrations are shown in Fig. 3. With increasing protein concentration, the absolute value of ionic bonds gradually decreased before plateauing (p < 0.05), while hydrophobic interactions significantly increased (p < 0.05). In contrast, hydrogen bond values remained negligible throughout (p > 0.05). These results indicated that ionic bonds and hydrophobic interactions dominate the formation of CS and CS-RA sol/gel at pH 2.0, aligning with our prior findings on acidic whey protein sol/gel systems (Wang et al., 2023). The observed behavior may arise from the low pH altering electrostatic and hydrophobic forces between CS micelles, thereby modifying their structural organization (Liu et al., 2008). Furthermore, elevated protein concentrations likely perturb charge distribution within the CS hairy layer, reducing electrostatic repulsion and amplifying intermolecular hydrophobic attraction (Phadungath, 2005). Notably, RA addition exhibited no significant impact on the chemical forces governing CS sol/gel formation (p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The chemical interactions of CS and CS-RA sol/gel with different protein concentrations at pH 2.0.

Based on the above results, the presence of citric acid can significantly reduce the pI of CS in acidic solution from pH 4.6 to pH 2.4 ∼ pH 2.8. Additionally, the change in pI was closely related to the charge carried by CS, which further affected its solubility (Post et al., 2012). Consequently, at pH 2.0, CS exhibited high charge density and solubility in the citric acid solution, whereas at pH 2.4–4.0, it showed reduced charge density and lower solubility. More importantly, the higher the charge carried by the CS molecule and its own solubility, the more conducive to the formation of a uniform and stable gel. This may be related to the fact that pH value affected the gelation of proteins by adjusting the balance of gravitational and repulsive forces between proteins (Zhu et al., 2022). Additionally, the synergistic effect of heating and acidification leads to reorganization, aggregation, and eventually formation of gel networks within CS (Tang et al., 2024). Consequently, when the protein concentration was 12 % (w/w), CS gel with citric acid as acidifier was prepared only at pH 2.0, and the forces maintaining its formation were ionic bond and hydrophobic interaction, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Hypothetical formation mechanism of stable CS solution and CS gel by citric acid acidification. Not drawn to scale.

3.4. Texture characteristic of CS and CS-RA sol/gel analysis

Since texture is closely related to sensory perception, it serves as a critical quality indicator in food applications. The texture properties of CS gels at different protein concentrations (12 % ∼ 21 %, w/w) are summarized in Table 1. Generally, hardness reaches its maximum during the first compression cycle (Jiang et al., 2024). As the protein concentration increased (12 % ∼ 18 %, w/w), the hardness of CS gels exhibited an upward trend. This indicated that elevating protein concentration within a specific range improves the compressive strength of CS gels, likely due to the reduced water content in the gel network. Previous studies have demonstrated that gel hardness is strongly correlated with water content (Cheng et al., 2025; Lucey, 2020). Additionally, Lucey et al. (2020) reported that heat-induced and acid-induced gels experienced a significant reduction in water content at 90 °C, promoting stronger protein-protein interactions and consequently increasing gel hardness (Lucey, 2020). Notably, when the protein concentration exceeded 18 % (w/w), the hardness of CS gel decreased significantly, which may be correlated with the increasing formation of bubbles within the gel matrix. More importantly, the type of acid also has a significant impact on the hardness of the milk gel. When the acidification temperature exceeded 70 °C, the hardness of milk gel was highest acidified by citric acid, followed by lactic acid, and HCl was lowest (Cheng et al., 2025).

Table 1.

The texture characteristics of CS and CS-RA sol/gel with different protein concentrations at pH 2.0.

| Sample | Hardness (g) | Springiness | Gumminess | Chewiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-12 % | 174.39 ± 9.99b | 0.46 ± 0.07ab | 61.79 ± 7.17a | 38.71 ± 5.03a |

| CS-RA-12 % | 144.59 ± 8.34a | 0.77 ± 0.24bc | 76.71 ± 17.54a | 57.02 ± 11.94ab |

| CS-15 % | 653.41 ± 73.63c | 0.28 ± 0.06a | 209.70 ± 10.75d | 74.11 ± 14.29bc |

| CS-RA-15 % | 576.16 ± 116.87c | 0.26 ± 0.05a | 188.19 ± 27.49cd | 72.33 ± 1.71bc |

| CS-18 % | 1122.22 ± 145.66d | 0.16 ± 0.02a | 200.89 ± 41.30d | 35.29 ± 4.16a |

| CS-RA-18 % | 1225.82 ± 205.07d | 0.14 ± 0.02a | 200.33 ± 28.92a | 29.11 ± 8.17a |

| CS-21 % | 1063.47 ± 76.30d | 0.19 ± 0.03a | 159.54 ± 21.26b | 23.99 ± 6.16a |

| CS-RA-21 % | 1130.04 ± 73.33d | 0.21 ± 0.02a | 144.12 ± 18.82b | 30.63 ± 2.54a |

Different letters in the same columns represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

Additionally, springiness represents the ability of the gel to bounce back after compression deformation (Min et al., 2022). Springiness of CS gels at low protein concentrations (12 %, w/w) was greater (about 0.46), while the result was reversed at high protein concentrations. This may be related to the water content present in the system, and the high CS concentration limits the role of water in the gel system, so the springiness of CS gel can be influenced by macromolecules through the spacing effect and the competition for water binding (Min et al., 2022). Commonly, gumminess is a parameter characterizing to the energy required in bursting the semisolid gel into the steady state of swallowing (Casas-Forero et al., 2020). Interestingly, the gumminess of CS gels both increased first and then decreased with the increase of protein concentration, and reached the maximum value (209.70) when the protein concentration was 15 % (w/w). This may be caused by changes in CS concentration affecting protein-protein interactions, which is strongest at 15 % (w/w) (Cheng et al., 2025). Meanwhile, these changes may further change the gumminess of the gel by affecting the uniformity of its internal structure. Usually, chewiness depends on the pressure and energy required to break down the gel structure. Notably, the chewability results of CS gel were like to those of its gumminess, indicating that its mechanical properties changed during chewing. Similarly, the addition of RA had no significant effect on the texture properties of CS sol/gel (p > 0.05). Studies have shown that the swallowing properties of gels were closely related to their hardness, springiness, gumminess and chewability, especially the gels with low hardness and chewability had good swallowing properties (Xia et al., 2024; Xie et al., 2022). Consequently, CS and CS-RA gels can have optimal swallowing performance at a protein concentration of 12 % (w/v).

3.5. In vitro simulated digestion of CS and CS-RA sol/gel analysis

3.5.1. DH of protein

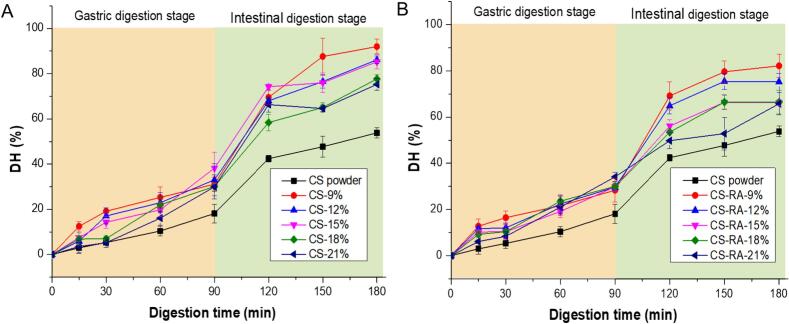

The DH of CS and CS-RA sol/gel during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion is shown in Fig. 5 and Table 2. The DH of all CS sol/gel samples increased gradually with gastric digestion time, reaching approximately 30 % by the end of the gastric phase. This phenomenon can be attributed to the hydrolysis of CS sol/gel under the combined effects of pepsin and the low pH environment of gastric juice, leading to the breakdown of CS molecules into low-molecular-weight peptides (Chen et al., 2024). Additionally, there was no significant difference in DH of all CS sol/gel at 90 min (p > 0.05), indicating that protein concentrations had no effect on DH of CS sol/gel at gastric stage. During intestinal digestion, the DH of all CS sol/gel samples exhibited a rapid initial increase (90–120 min), followed by a slower rise (120–180 min). Notably, the DH was significantly higher in the intestinal phase than in the gastric phase, indicating that the digestion of CS sol/gel predominantly occurred in the intestine. This may be due to the structural rearrangement of CS sol/gel during gastric digestion, which was not sustained in the intestinal environment (Liao et al., 2024). Importantly, after intestinal digestion, the DH of all CS sol/gel samples decreased significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing CS concentration. This trend may be associated with the hardness of the CS gel/sol matrix, as a denser gel structure offers greater resistance to physical breakdown and restricts enzyme accessibility (Li et al., 2024).

Fig. 5.

The DH changes of CS and CS-RA sol/gel at different stages and times of digestion.

Table 2.

The DH of CS and CS-RA sol/gel after simulated gastric digestion and intestinal digestion.

| Sample | DH (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gastric digestion stage (90 min) | Intestinal digestion stage (180 min) | |

| CS powder | 18.14 ± 4.18a | 53.81 ± 2.26a |

| CS-9 % | 31.08 ± 3.16bc | 91.99 ± 3.22e |

| CS-RA-9 % | 28.29 ± 5.14b | 78.15 ± 4.95c |

| CS-12 % | 33.06 ± 7.03bc | 86.15 ± 1.65d |

| CS-RA-12 % | 29.64 ± 1.64b | 67.55 ± 3.67b |

| CS-15 % | 38.27 ± 7.07c | 85.25 ± 3.11d |

| CS-RA-15 % | 29.82 ± 1.95b | 66.21 ± 1.24b |

| CS-18 % | 30.09 ± 2.02b | 77.70 ± 1.89c |

| CS-RA-18 % | 30.01 ± 1.36b | 66.49 ± 5.16b |

| CS-21 % | 29.91 ± 5.37b | 75.28 ± 2.69c |

| CS-RA-21 % | 34.13 ± 2.02bc | 65.75 ± 4.76b |

Different letters in the same columns represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

Interestingly, the DH of all CS sol/gel was significantly higher than that of CS powder during gastric and intestinal digestion (p < 0.05), and the DH of CS powder was only 18.14 % and 53.81 % after 90 min and 180 min of digestion, respectively. This may be related to the heating treatment during the preparation of CS sol/gel. Studies have shown that the milk formed relatively loose clots after heating, which leaded to faster hydrolysis of CS during stomach digestion (Ye et al., 2019). Additionally, heat treatment at higher temperature can lead to more broken milk curdles and higher protein hydrolysis rate (Mulet-Cabero et al., 2019). More importantly, compared with CS sol/gel, the DH of CS-RA sol/gel remained unchanged during the gastric digestion stage (p > 0.05), but the DH of CS-RA sol/gel decreased significantly during the intestinal digestion stage (p < 0.05). It may be that RA interacted with trypsin to form a complex, which reduced the catalytic activity of the enzyme, and ultimately leaded to a decrease in the DH of the protein (Zhao et al., 2020).

3.5.2. Release rate of RA

The RA release rate of CS-RA sol/gel at different digestion stages is shown in Fig. 6 and Table 3. Before gastric digestion, the RA release rate was approximately 15 %, which might result from either unbound RA (failed to interact with CS) or structural damage to the CS-RA sol/gel during sample preparation. During gastric digestion (0–60 min), the RA release exhibited a gradual increase, followed by a rapid surge at 60–90 min. This pattern can be explained by the initial micellar structure of CS-RA sol/gel and its subsequent rearrangement under digestive conditions (Liao et al., 2024). By the end of gastric digestion, the cumulative RA release rate reached 52.71 % ∼ 63.39 %, confirming that gastric digestion dominated RA release. Consistent with prior research, the coagulation-induced structural reorganization of micellar CS effectively delays the release of bioactive compounds (Sadiq et al., 2021).

Fig. 6.

The RA release rate changes of CS-RA sol/gel at different stages and times of digestion.

Table 3.

The RA release rate of CS-RA sol/gel after simulated gastric digestion and intestinal digestion.

| Sample | RA release rate(%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gastric digestion stage (90 min) | Intestinal digestion stage (180 min) | |

| CS-RA-9 % | 63.29 ± 3.32b | 83.47 ± 4.61b |

| CS-RA-12 % | 52.71 ± 3.85a | 82.12 ± 2.97b |

| CS-RA-15 % | 63.39 ± 3.66b | 79.98 ± 2.69ab |

| CS-RA-18 % | 54.91 ± 2.33a | 76.63 ± 1.50a |

| CS-RA-21 % | 53.61 ± 3.66a | 76.58 ± 2.32a |

Different letters in the same columns represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

In the intestinal phase, the RA release rose sharply during the initial 30 min (90–120 min), then plateaued gradually (120–180 min), ultimately stabilizing at 76.58 % ∼ 83.47 %. This two-stage behavior likely reflects the disruption of gastric micellar structures in the intestinal environment, triggering rapid RA dissociation (Liao et al., 2024). Notably, protein concentration significantly influenced the final RA release rate (p < 0.05), with higher CS concentrations yielding lower release rates. As inferred from Sections 3.4 and 3.5.1, this inverse correlation may arise from excessive gel hardness and gumminess, which impede CS hydrolysis and trap RA within the protein matrix.

4. Conclusion

pH and protein concentration were critical factors affecting the formation of CS gels induced by citric acid and heat. CS gels formed exclusively at pH 2.0 and protein concentrations ≥12 %, driven primarily by hydrophobic interactions and ionic bonds. Moreover, gel formation correlated closely with CS molecular solubility and ζ-potential; higher values favored gelation. Notably, CS gels exhibited optimal textural properties at 12 % protein concentration. In terms of controlled release, CS gels positively affected RA delivery, with lower protein concentrations enhancing the release efficiency. Conversely, RA impaired the in vitro digestibility of CS gel proteins.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yun Wang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Qianyi Yao: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. Li Yin: Methodology, Data curation. Rongzhen Song: Writing – review & editing. Chunmei Li: Conceptualization. Haifeng Zhang: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 32401974), “Green Yangzhou Golden Phoenix” funding of Yangzhou (137013475), and High-level Talents Project of Yangzhou University (137013154).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102893.

Contributor Information

Chunmei Li, Email: licm@yzu.edu.cn.

Haifeng Zhang, Email: zhanghf@yzu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72(1–2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyard C., Gaucheron F. Modifications of structures and functions of caseins: A scientific and technological challenge. Dairy Science & Technology. 2015;95:831–862. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Forero N., Orellana-Palma P., Petzold G. Comparative study of the structural properties, color, bioactive compounds content and antioxidant capacity of aerated gelatin gels enriched with cryoconcentrated blueberry juice during storage. Polymers. 2020;12(12):2769. doi: 10.3390/polym12122769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Zhou K., Xie Y., Nie W., Li P., Zhou H., Xu B. Glutathione-mediated formation of disulfide bonds modulates the properties of myofibrillar protein gels at different temperatures. Food Chemistry. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Fan R., Wang X., Zhang L., Wang C., Hou Z., Li C., Liu L., He J. In vitro digestion and functional properties of bovine β-casein: A comparison between adults and infants. Food Research International. 2024;194 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z., Xia W., van Leusden P., Czaja T.P., Eisner M.D., Ahrné L. Combined effect of acidification temperature and different acids on microstructure and textural properties of heat and acid-induced milk gels. International Dairy Journal. 2025;161 [Google Scholar]

- Choi I., Zhong Q. Physicochemical properties of skim milk powder dispersions after acidification to pH 2.4–3.0 and heating. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;100 [Google Scholar]

- Choi I., Zhong Q. Gluconic acid as a chelator to improve clarity of skim milk powder dispersions at pH 3.0. Food Chemistry. 2021;344 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei S., Li Y., Liu K., Wang H., Abd El-Aty A.M., Tan M. Salmon protein gel enhancement for dysphagia diets: Konjac glucomannan and composite emulsions as texture modifiers. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;258 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Joy N., Sivadas A. Relevance of natural degradable polymers in the biomedical field. Biomedical Applications of Polymeric Materials and Composites. 2016:303–360. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Hu Z., Li G., Chin Y., Pei Z., Yao Q., Li D., Hu Y. The highly stable indicator film incorporating roselle anthocyanin co-pigmented with oxalic acid: Preparation, characterization and freshness monitoring application. Food Research International. 2023;173 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D., Huang Q., Xiong S. Chemical interactions and gel properties of black carp actomyosin affected by MTGase and their relationships. Food Chemistry. 2016;196:1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Zhang Z., Zhao J., Liu Y. The effect of non-covalent interaction of chlorogenic acid with whey protein and casein on physicochemical and radical-scavenging activity of in vitro protein digests. Food Chemistry. 2018;268:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Liu J., Xiao N., Zhang X., Liang Q., Shi W. Characterization of the textural properties of thermally induced starch-surimi gels: Morphological and structural observation. Food Bioscience. 2024;58 [Google Scholar]

- Laursen A.K., Dyrnø S.B., Mikkelsen K.S., Czaja T.P., Rovers T.A.M., Ipsen R., Ahrné L. Effect of coagulation temperature on cooking integrity of heat and acid-induced milk gels. Food Research International. 2023;169 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Mungure T., Ye A., Loveday S.M., Ellis A., Weeks M., Singh H. Intragastric restructuring dictates the digestive kinetics of heat-set milk protein gels of contrasting textures. Food Research International. 2024;195 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M., Li W., Peng L., Li J., Ren J., Li K., Chen F., Hu X., Liao X., Ma L., Ji J. High hydrostatic pressure induced gastrointestinal digestion behaviors of quercetin-loaded casein delivery systems under different calcium concentration. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;21 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Guo R. pH-dependent structures and properties of casein micelles. Biophysical Chemistry. 2008;136(2):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey J.A. Milk proteins. Elsevier; 2020. Milk protein gels; pp. 599–632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Zhang N., Zhao X. Impact of covalent grafting of two flavonols (kaemperol and quercetin) to caseinate on in vitro digestibility and emulsifying properties of the caseinate-flavonol grafts. Food Chemistry. 2022;390 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C., Ma W., Kuang J., Huang J., Xiong Y.L. Textural properties, microstructure and digestibility of mungbean starch–flaxseed protein composite gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;126 [Google Scholar]

- Morrison I.D., Ross S. Wiley; NY, USA: 2002. Colloidal dispersions; suspensions, emulsions and foams. [Google Scholar]

- Mulet-Cabero A.I., Mackie A.R., Wilde P.J., Fenelon M.A., Brodkorb A. Structural mechanism and kinetics of in vitro gastric digestion are affected by process-induced changes in bovine milk. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;86:172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento L.G.L., Casanova F., Silva N.F.N., Teixeira A.V.N.C., Carvalho A.F. Casein-based hydrogels: A mini-review. Food Chemistry. 2020;314 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen P., Petersen D., Dambmann C. Improved method for determining food protein degree of hydrolysis. Journal of Food Science. 2006;66(5):642–646. [Google Scholar]

- Phadungath C. The mechanism and properties of acid-coagulated milk gels. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology. 2005;27(2):433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Post A.E., Arnold B., Weiss J., Hinrichs J. Effect of temperature and pH on the solubility of caseins: Environmental influences on the dissociation of αS- and β-casein. Journal of Dairy Science. 2012;95(4):1603–1616. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pougher N., Vollmer A.H., Sharma P. Effect of pH and calcium chelation on cold gelling properties of highly concentrated-micellar casein concentrate. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2024;214 [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq U., Gill H., Chandrapala J. Casein micelles as an emerging delivery system for bioactive food components. Foods. 2021;10(8):1965. doi: 10.3390/foods10081965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., Roos Y.H., Vahedikia N., Miao S. Evaluation on pH-dependent thermal gelation performance of chickpea, pea protein, and casein micelles. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;149 [Google Scholar]

- Tiong A.Y.J., Crawford S., Jones N.C., McKinley G.H., Batchelor W., van ’t Hag, L. Pea and soy protein isolate fractal gels: The role of protein composition, structure and solubility on their gelation behaviour. Food Structure. 2024;40 [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez-Dominguez A., Hennetier M., Abdallah M., Hiolle M., Violleau F., Delaplace G., Peixoto P. Influence of enzymatic cross-linking on the apparent viscosity and molecular characteristics of casein micelles at neutral and acidic pH. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;139 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yang C., Zhang J., Zhang L. Influence of rose anthocyanin extracts on physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibility of whey protein isolate sol/gel: Based on different pHs and protein concentrations. Food Chemistry. 2023;405 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia W., Drositi I., Czaja T.P., Via M., Ahrné L. Towards hybrid protein foods: Heat- and acid-induced hybrid gels formed from micellar casein and pea protein. Food Research International. 2024;198 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.115326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Yu X., Wang Y., Yu C., Prakash S., Zhu B., Dong X. Role of dietary fiber and flaxseed oil in altering the physicochemical properties and 3D printability of cod protein composite gel. Journal of Food Engineering. 2022;327 [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Xu Q., Wang X., Bai Z., Xu X., Ma J. Casein-based hydrogels: Advances and prospects. Food Chemistry. 2024;447 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye A., Liu W., Cui J., Kong X., Roy D., Kong Y., Han J., Singh H. Coagulation behaviour of milk under gastric digestion: Effect of pasteurization and ultra-high temperature treatment. Food Chemistry. 2019;286:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Yu X., Zhou C., Yagoub A.E.A., Ma H. Effects of collagen and casein with phenolic compounds interactions on protein in vitro digestion and antioxidation. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2020;124 [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Du H., Ye E., Xu X., Wang X., Jiang X., Min Z., Zhuang L., Li S., Guo L. Optimized extraction of polyphenols with antioxidant and anti-biofilm activities and LC-MS/MS-based characterization of phlorotannins from Sargassum muticum. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2024;198 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P., Huang W., Chen L. Develop and characterize thermally reversible transparent gels from pea protein isolate and study the gel formation mechanisms. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;125 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.