Abstract

Background

The commonly used brominated flame retardant (2,2’,4,4’-Tetrabromodiphenyl Ether, BDE-47) is a persistent organic pollutant that is widely distributed in the environment and is associated with adverse health effects, including an increased risk of osteoarthritis. However, the specific molecular mechanisms by which BDE-47 contributes to the development of osteoarthritis (OA) remain largely unclear. This study aimed to investigate the potential relationship between BDE-47 exposure and osteoarthritis pathogenesis.

Methods

To achieve this, we employed an integrative approach combining network toxicology, machine learning, SHAP analysis, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations.

Results

Initially, potential target genes associated with BDE-47 and OA were retrieved from multiple public databases, including PharmMapper, ChEMBL, and GEO. Subsequently, a comprehensive machine learning workflow involving 113 different algorithms was used to identify 10 core target genes as potential mediators of BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis. Finally, SHAP analysis identified FKBP5 as the most critical toxic target. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were then performed to evaluate the binding interactions and stability between BDE-47 and FKBP5.

Conclusion

The research results suggest that BDE-47 may be involved in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis by targeting and regulating specific toxic targets, with FKBP5 being particularly prominent as the most crucial potential therapeutic target. These insights provide a theoretical foundation for developing preventive and therapeutic strategies against BDE-47-induced OA and underscore the importance of raising public awareness regarding the health risks of environmental pollution.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40360-025-00990-4.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, BDE-47, Network toxicology, Machine learning, Molecular docking

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common chronic joint conditions, impacting hundreds of millions globally and showing a steady rise in occurrence [1]. The disease not only involves the degeneration of articular cartilage, synovial membrane, and adjacent muscular structures but also disrupts the metabolic homeostasis of joint tissues, resulting in pathological alterations such as inflammation and cartilage degradation [2, 3]. Clinically, OA is characterized by symptoms including joint pain, stiffness, and limited mobility; in advanced stages, it may lead to joint deformities, functional impairment, and even disability [4, 5]. The pathogenesis of osteoarthritis is multifactorial and complex, with research indicating a strong association with chronic inflammation and autoimmune responses. In particular, factors such as mitochondrial dysfunction, hypoxia, autophagy, glycolysis, and apoptosis play critical roles in the disease development [6]. Despite these advances, effective clinical therapies remain limited, highlighting the urgent need for preventive strategies [7, 8].

In recent years, rapid global population growth coupled with accelerated industrialization has significantly exacerbated environmental pollution. The large-scale production and utilization of industrial chemicals have given rise to numerous pollutants, whose toxicological characteristics have attracted considerable attention. Among these, 2,2′,4,4′-Tetrabromodiphenyl Ether, a member of the polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), is notable for its extensive distribution, high bioaccumulation potential, and marked toxicity, and is widely used as an additive brominated flame retardant [9]. The unique molecular structure of BDE-47 confers exceptional thermal and chemical stability, which effectively reduces the flammability of materials during use, thereby serving as an efficient flame retardant. Consequently, it is extensively utilized in a variety of consumer products, including electronic devices, furniture, and building materials [10]. However, during the lifecycle of these products—from usage to disposal—BDE-47 gradually leaches into the environment. Unlike chemically bonded flame retardants, BDE-47 is physically blended within the polymer matrix, and this non-covalent association renders it more prone to release under conditions of heat or mechanical abrasion, ultimately leading to soil and water contamination [11]. BDE-47 can enter the human body through multiple pathways, posing potential health risks via inhalation, ingestion, dermal contact, and maternal transfer through breast milk [12]. Existing studies indicate that BDE-47 may disrupt thyroid axis function, activate matrix metalloproteinases, impair mitochondrial function, and adversely affect the endocrine system, oxidative stress balance, and extracellular matrix metabolism—mechanisms that collectively suggest a negative impact on bone and cartilage health [8, 13, 14]. Although direct evidence of BDE-47’s effects on human bone and cartilage is currently limited, its demonstrated toxicity in animal models and cellular systems implies a potential risk to human skeletal and chondral integrity. Given the increasing prevalence of BDE-47-containing products, such as electronic devices, there is an urgent need to employ advanced and innovative methodologies to evaluate the associated health hazards.

Integrating network toxicology, machine learning, SHAP analysis, and molecular docking provides a robust framework for investigating toxicant-induced diseases [15]. Network toxicology, grounded in network pharmacology and systems biology, combines bioinformatics, genomics, and proteomics to map interactions among toxicants, targets, and diseases. This facilitates the identification of key pathways and supports environmental risk assessment with high efficiency and broad applicability [16]. Molecular docking complements this by predicting the binding behavior between small molecules and proteins, where lower binding energies indicate stronger interactions [17]. Machine learning further enhances this strategy by improving disease prediction and biomarker identification, while SHAP analysis helps interpret the influence of individual features on model outputs.

This research employs a comprehensive strategy that integrates network toxicology, machine learning and molecular docking methods to systematically evaluate the potential effects of the environmental contaminant BDE-47 on osteoarthritis and to reveal its underlying biological mechanisms. This multidisciplinary strategy not only deepens our understanding of the role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis but also provides a robust scientific foundation for the development of preventive strategies aimed at reducing environmental pollution and, consequently, the risk of osteoarthritis.

Materials and methods

Identification of BDE-47-Related targets

Initially, the chemical structure and SMILES notation of BDE-47 were obtained from the PubChem database using the keyword “2,2′,4,4′-Tetrabromodiphenyl ether.” Subsequently, this molecular information was used to query potential targets of BDE-47 in the PharmMapper, ChEMBL, SwissTargetPrediction, and Comparative Toxicogenomics Database, with the search restricted to Homo sapiens. Only targets with a probability (or score) greater than zero were retained to capture targets that might otherwise be overlooked [18]. Finally, after integrating the target genes identified from the four databases and removing duplicates, a total of 4788 target genes were obtained, and the target names were standardized using the Uniprot database [19]. The relevant URLs of all databases are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Identification of osteoarthritis-related targets

To investigate osteoarthritis-related targets, the following representative osteoarthritis-related datasets were retrieved from the GEO database: GSE51588 (including 40 osteoarthritis patients and 10 normal controls), GSE55457 (including 10 osteoarthritis patients and 10 normal controls), and GSE206848 (including 7 osteoarthritis patients and 7 normal controls). Prior to differential expression analysis, batch effects across multiple datasets were mitigated using the “ComBat” function from the “sva” package. The effectiveness of this correction was assessed by comparing and visualizing the data quality before and after adjustment using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [20]. Subsequently, the osteoarthritis datasets were analyzed using the “Limma” package in R version 4.2.1 to pinpoint differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In the statistical analysis, genes with a p-value less than 0.05 and an absolute log fold change greater than 1 were identified as differentially expressed genes, resulting in a total of 82 differential genes. Finally, the results were visualized using the “pheatmap” and “ggplot2” packages in R [21].

Identification of BDE-47-Related disease targets

In this study, we cross-referenced osteoarthritis-related DEGs with the predicted targets of BDE-47 to pinpoint overlapping targets that might play a role in BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis toxicity. To visually illustrate this process, a Venn diagram was generated using the “VennDiagram” package in R [22].

Functional analysis of potential targets

To investigate the biological functions and signaling pathways related to osteoarthritis after BDE-47 exposure, we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis on the potential targets. These analyses were conducted using the “clusterProfiler,” “org.Hs.eg.db,” and “enrichplot” packages in R [23]. We utilized Gene Ontology analysis—covering biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF)—to clarify the key biological roles of these potential targets. Simultaneously, KEGG analysis was utilized to identify key metabolic pathways and signal transduction mechanisms associated with osteoarthritis and BDE-47. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was set to ensure the statistical robustness of the enriched pathways and functions.

Construction of the Protein-Protein interaction (PPI) network for potential targets

To comprehensively elucidate the biological functions and interrelationships of potential targets associated with BDE-47 and osteoarthritis, we conducted a PPI analysis on the intersecting genes using the STRING database. In this analysis, the species was strictly restricted to Homo sapiens, and a minimum interaction score of medium confidence (> 0.4) was applied to ensure the selected interactions possess reliable biological significance. Subsequently, the resulting PPI network was visualized using Cytoscape 3.10.3, which efficiently constructs and displays the complex interrelationships among the proteins, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent network analyses [24].

Screening of core targets using machine learning algorithms

In this study, we employed machine learning algorithms to perform an in-depth analysis of the data. Initially, the raw data underwent preprocessing, which involved the removal of missing values and outliers. Z-score normalization was then applied to adjust each feature’s mean to 0 and standard deviation to 1, thereby eliminating the influence of varying scales among features. Subsequently, the datasets (GSE51588, GSE55457, and GSE206848) were randomly divided into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%). The detailed workflow and parameter settings are provided in Supplementary Table 2. During the model evaluation phase, we assessed the classification performance of each model by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) values on the test set, with a threshold set at 0.7. Ultimately, the RunEval function was used to compute the AUC values for each model, while the SimpleHeatmap function was applied to generate heatmaps for visualizing model performance. The model exhibiting the highest AUC score was ultimately chosen [25].

Construction and validation of the predictive model

The diagnostic model was established based on the model achieving the highest area under the curve value, and its calibration performance was evaluated using calibration curves. The predictive accuracy across various datasets was quantified by calculating the AUC, with higher AUC values indicating a stronger discriminative capability.

Single-Gene GSEA enrichment analysis of hub genes in osteoarthritis

To comprehensively investigate the potential regulatory roles of key genes in osteoarthritis, the “C2: KEGG gene sets” database was utilized. A single-gene gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted for each hub gene using the R packages “org.Hs.eg.db”, “clusterProfiler”, and “enrichplot”, with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05 [26]. Unlike traditional methods that depend on differentially expressed genes, single-gene GSEA evaluates the enrichment status of all genes in the dataset, thereby offering a more comprehensive insight into the gene expression landscape.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

We applied the CIBERSORT algorithm to determine the extent of infiltration for 24 distinct immune cell types. The resulting data and associated characteristics were visualized using R [27]. Notably, immune cells exhibit specific patterns of infiltration and retention during disease onset and progression, offering valuable insights into their functional roles in the underlying mechanisms of disease development.

Molecular docking of BDE-47 with core targets

Molecular docking was employed to predict the binding modes and affinities between BDE-47 and core targets, thereby providing insights into the molecular interactions. Initially, the 2D structure of the small-molecule ligand was extracted from the PubChem database and stored in SDF format [35]. This 2D structure was then imported into Chem Office 20.0 to generate its corresponding three-dimensional conformation, which was saved as a mol2 file. Concurrently, the protein structures of the core targets were downloaded in PDB format from UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) and the RCSB PDB database (http://www.rcsb.org/). After removing water molecules and any bound ligands using PyMOL 2.3.0, the proteins were processed in Autodock Tools 1.5.7 for hydrogen addition and charge calculation. The prepared small-molecule ligand was then imported and saved in PDBQT format. A Grid Box was defined to encompass the active site, and molecular docking was performed using Autodock Vina [28]. The interaction was assessed by binding energy: a value below 0 kcal/mol indicates a spontaneous binding process, while a binding energy below − 5 kcal/mol implies a highly stable interaction. Finally, the docking results were visualized using Discovery Studio 2019 to facilitate further analysis.

SHAP analysis

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis is a powerful approach for interpreting the predictions of machine learning models. One of its key advantages lies in its ability to provide consistent and reliable feature attributions without requiring aggregation of SHAP values across different data partitions. This ensures that the interpretability faithfully reflects the characteristics of the model trained on the complete dataset. By quantifying the contribution of each feature to the model’s output, SHAP analysis enables the effective identification of variables that most significantly influence predictive performance.

Molecular dynamics simulation

In this study, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using GROMACS 2022 to investigate the binding interactions and stability of the protein–compound complex. A 200-nanosecond production simulation was performed under consistent conditions to gain deeper insights into the interaction mechanisms between the compound and the candidate protein. Detailed simulation parameters and setup information are provided in Supplementary Table 7.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language (version 4.2). To construct a robust predictive model, the model’s predictive performance was assessed using receiver operating characteristic curves and the area under the curve values, ensuring high diagnostic accuracy and stability. Statistical significance was defined as follows: **** indicates P < 0.0001, *** indicates P < 0.001, ** indicates P < 0.01, and * indicates P < 0.05.

Results

Collection of BDE-47 target genes

Figure 1 provides an overview of the data analysis workflow in this study. BDE-47 was queried in the PubChem database to retrieve its chemical structure and corresponding SMILES notation (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, potential targets of BDE-47 were identified using PharmMapper, ChEMBL, and the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database, with additional predictions made using SwissTargetPrediction. After integrating and de-duplicating the targets obtained from these four databases, a total of 4788 unique BDE-47 target genes were identified (Supplementary Table 8).

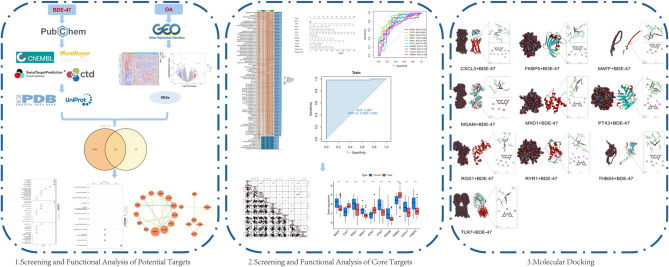

Fig. 1.

Workflow of data processing and analysis in this study

Fig. 2.

Screening of potential targets. (a) Chemical structure and SMILES representation of BDE-47. (b) Principal component analysis of the osteoarthritis dataset before batch effect correction. (c) PCA of the OA dataset after batch effect correction. (d) Heatmap of significantly differentially expressed genes in OA. (e) Volcano plot of significantly differentially expressed genes in OA. (f) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between BDE-47 target genes and OA-related target genes. (g) Protein-protein interaction network of the 30 potential targets

Collection of osteoarthritis-related targets

Osteoarthritis-related datasets were retrieved from the GEO database using “osteoarthritis” as the search keyword, yielding three datasets: GSE206848, GSE55457, and GSE51588. A detailed summary of these datasets is provided in Supplementary Table 3. After eliminating batch effects, the datasets were integrated and normalized, resulting in a combined cohort of 27 control samples and 57 osteoarthritis cases. Principal Component Analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in batch effects (Fig. 2b and c). Differential expression analysis of the integrated osteoarthritis samples identified 82 DEGs, comprising 37 upregulated and 45 downregulated genes (Supplementary Table 4). We utilized heatmaps and volcano plots to illustrate the 20 differentially expressed genes with the most significant upregulation and downregulation (Fig. 2d and e).

Identification of BDE-47-Associated osteoarthritis targets

The differentially expressed genes related to osteoarthritis were intersected with the identified targets of BDE-47, resulting in 30 overlapping genes that are potential mediators of BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis (Supplementary Table 5). These overlapping targets were visualized using a Venn diagram (Fig. 2f).

GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of overlapping target genes

To elucidate the mechanistic role of the 30 potential target genes in BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were performed (Supplementary Figs. 1a and 1b). In the BP category, enriched terms included extracellular matrix organization, extracellular structure organization, external encapsulating structure organization, leukocyte migration, production of molecular mediators involved in immune responses, regulation of cytokine production in immune responses, cytokine production during immune reactions, antimicrobial humoral responses mediated by antimicrobial peptides, production of macrophage cytokines, and regulation of macrophage cytokine production. In the CC category, the enriched terms comprised collagen-containing extracellular matrix, secretory granule lumen, cytoplasmic vesicle lumen, vesicle lumen, basement membrane, specific granules, tertiary granules, fibrillar collagen trimer, banded collagen fibers, and collagen trimer complex. For the MF category, the analysis revealed enrichment in terms such as carbohydrate binding, integrin binding, extracellular matrix structural constituent, heparin binding, cytokine activity, aromatic amino acid transmembrane transporter activity, platelet-derived growth factor binding, extracellular matrix structural constituent conferring tensile strength, chemokine activity, and L-amino acid transmembrane transporter activity.

KEGG pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of these target genes in several signaling pathways, including the IL-17 signaling pathway, rheumatoid arthritis, protein digestion and absorption, cytoskeletal dynamics in muscle cells, PPAR signaling, colorectal cancer, ECM-receptor interaction, interactions between viral proteins and cytokines as well as their receptors, amebiasis, NF-kappa B signaling, TNF signaling, and relaxin signaling. These findings suggest that BDE-47 may contribute to the onset and progression of osteoarthritis by modulating these key signaling pathways and biological processes, thus providing valuable insights for further mechanistic studies.

Construction of the potential target interaction network

To gain a deeper understanding of the interactions among potential targets, a PPI analysis was performed on the 30 identified targets using the STRING database, with a confidence threshold set at ≥ 0.4 to ensure biological relevance. The constructed network comprised 30 nodes and 23 edges, with an average node degree of 1.53, indicating that the protein interactions within the network were both specific and tightly connected. Subsequently, the network was visualized using Cytoscape 3.10.3, providing a clear depiction of the complex interaction patterns among the potential targets and laying the groundwork for further network topology analysis and identification of key regulatory nodes (Fig. 2g).

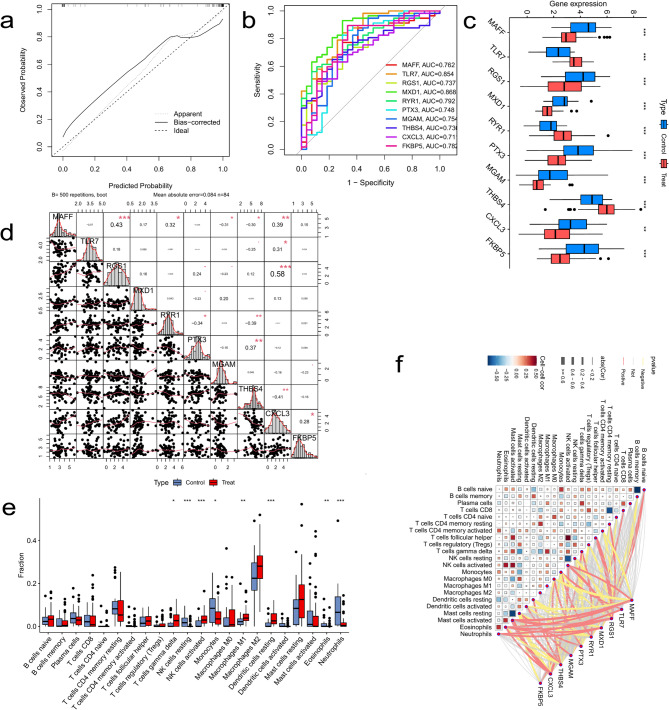

Identification of predictive hub genes using machine learning

To identify the most robust predictive model among 30 potential target genes, we constructed 113 predictive models using 12 different machine learning algorithms. The results demonstrated that the Stepglm[both] + GBM model outperformed all other models, achieving an average area under the curve value of 0.951. This model successfully identified 10 core target genes: MAFF, TLR7, RGS1, MXD1, RYR1, PTX3, MGAM, THBS4, CXCL3, and FKBP5 (Fig. 3a). We further evaluated the model performance using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis in both the training and test cohorts, observing outstanding performance with AUC values exceeding 0.9 (Figs. 3b-e). To enhance the accuracy of disease prediction, a nomogram was constructed based on these 10 hub genes, demonstrating strong predictive capability (Fig. 3f). Decision curve analysis (DCA) confirmed the model’s stability (Fig. 3g). The calibration curve analysis indicated high consistency between the predicted probability and observed probability, with the bias-corrected curve closely aligning with the ideal reference line (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the mean absolute error (MAE = 0.084, n = 84) further validated the calibration accuracy of the model. Feature selection and validation of the 10 candidate genes (MAFF, TLR7, RGS1, etc.) were performed using machine learning models. The AUC values confirmed their strong discriminatory power (Fig. 4b). Among them, MXD1 (AUC = 0.868) and TLR7 (AUC = 0.854) exhibited the highest classification performance, while CXCL3 (AUC = 0.71) and THBS4 (AUC = 0.73) showed relatively weaker predictive power. However, all selected targets had AUC values greater than 0.7, suggesting their strong potential for effective disease risk prediction.

Fig. 3.

Performance evaluation and predictive analysis of machine learning models. (a) Summary of the testing performance of 113 machine learning models. (b) Receiver operating characteristic curve of the training cohort. (c-e) ROC curves of the testing cohort. (f) Nomogram for predicting the risk of osteoarthritis progression. (g) Decision curve analysis of the model

Fig. 4.

Expression analysis of core genes and immune infiltration characteristics. (a) Calibration curve of the nomogram. (b) Receiver operating characteristic curves of the 10 core genes. (c) Expression levels of core genes in the disease and healthy groups. (d) Correlation analysis among core genes. (e) Box plot comparing the infiltration abundance of different immune cell types between the disease and control groups. (f) Heatmap showing the correlation between immune cell types and core genes. Each cell represents the correlation coefficient, ranging from − 0.5 (strong negative correlation, dark blue) to 0.5 (strong positive correlation, dark red), with 0 indicating no correlation

Correlation analysis and differential expression of hub genes

To elucidate the potential interactions among hub genes in BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis, we conducted a correlation analysis. The results revealed several significant associations: FKBP5 was positively correlated with MAFF (OR: 0.28, P < 0.05). MAFF, TLR7, and RGS1 were all positively correlated with CXCL3 (OR: 0.39/0.31/0.58, P < 0.05). THBS4 was negatively correlated with CXCL3 (OR: -0.41, P < 0.05). MAFF and RYR1 were both negatively correlated with THBS4 (OR: -0.30/-0.39, P < 0.05). PTX3 was positively correlated with THBS4 (OR: 0.37, P < 0.05). MAFF was negatively correlated with MGAM (OR: -0.31, P < 0.05), while RYR1 was negatively correlated with PTX3 (OR: -0.34, P < 0.05). Moreover, the analysis indicated that MAFF exhibited a positive association with RYR1 (OR: 0.32, P < 0.05) as well as with RGS1 (OR: 0.43, P < 0.05). (Fig. 4d).

Furthermore, the expression patterns of these key genes were compared between the osteoarthritis group and the normal control group. The results indicated that in the disease group, the expression levels of MAFF, TLR7, RGS1, MXD1, RYR1, PTX3, THBS4, and FKBP5 were significantly elevated, while those of MGAM and CXCL3 were markedly reduced. These observations suggest that these hub genes may play pivotal regulatory roles in BDE-47-induced osteoarthritis, with their expression alterations being closely linked to disease onset and progression (Fig. 4c).

Single-gene GSEA enrichment analysis

To further investigate the regulatory mechanisms of the 10 hub genes in osteoarthritis, a single-gene GSEA was conducted. The analysis demonstrated that the expression of these genes is closely linked to several critical biological pathways (Supplementary Figs. 2a-j), such as the MAPK, NOD-like receptor, Toll-like receptor, p53, and T-cell receptor signaling pathways. The enrichment of these pathways suggests that the onset and progression of osteoarthritis involve intricate biological processes, with the hub genes potentially modulating disease development through the regulation of diverse molecular pathways. It is noteworthy that the pronounced enrichment of various immune-related pathways underscores a strong link between the expression of these hub genes and the immune response in osteoarthritis.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

To further elucidate the pathogenesis of OA, this study quantitatively assessed the infiltration levels of immune cells within OA tissues. Utilizing the CIBERSORT algorithm, we evaluated the expression profiles and infiltration scores of various immune cell types in OA samples. The results (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Fig. 4e) revealed statistically significant differences in the expression levels of eight immune cell subsets between healthy controls and OA patients. Specifically, compared to the healthy group, the OA group exhibited a marked increase in the infiltration of γδ T cells, activated natural killer (NK) cells, M1 macrophages, and resting dendritic cells, whereas the infiltration levels of resting NK cells, monocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils were significantly reduced.

Further immune correlation analysis (Fig. 4f) demonstrated a strong association between the expression of hub genes and immune cell infiltration patterns. This finding not only confirms the close relationship between the identified hub genes and immune infiltration in OA but also suggests their potential regulatory roles in disease progression.

Molecular docking analysis

To further investigate the binding affinity between BDE-47 and the identified hub targets, we performed molecular docking analysis. The binding energy values for molecular docking are presented in Supplementary Table 6. The results demonstrated that all 10 hub genes could spontaneously bind to the environmental pollutant BDE-47, as indicated by binding energy values below 0 kcal/mol. Notably, nine core targets—TLR7, RGS1, MXD1, RYR1, PTX3, MGAM, THBS4, CXCL3, and FKBP5—exhibited binding energy values lower than − 5 kcal/mol, suggesting the formation of stable interactions between these genes and BDE-47 (Figs. 5A–J). These findings imply that BDE-47 may exert its effects on osteoarthritis-related biological processes through direct interactions with these key genes.

Fig. 5.

Molecular Docking Analysis of BDE-47 with the 10 Core Genes

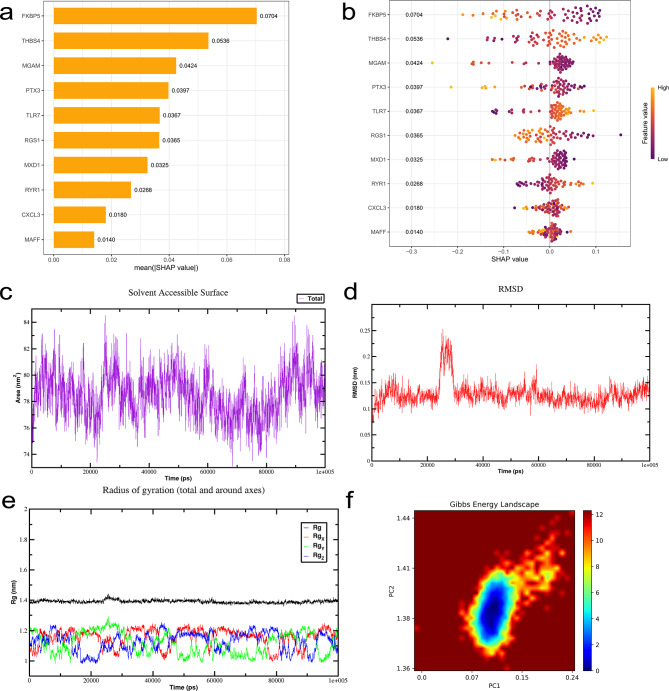

SHAP analysis

To gain a more detailed understanding of how the selected variables contribute to model predictions, we employed SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis for model interpretation. The SHAP value distributions for continuous variables, as illustrated in Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 2k, clearly indicate that FKBP5, MGAM, and PTX3 are negatively associated with disease status, whereas THBS4 and TLR7 show positive correlations. In the SHAP summary plot (Fig. 6b), each point represents a sample: the SHAP value on the x-axis quantifies the impact of specific gene expression on the model’s prediction. Positive values push the prediction toward the disease group (higher osteoarthritis risk), while negative values pull it toward the control group (lower risk). In the color gradient, purple (low feature value) represents low gene expression, while yellow (high feature value) indicates high gene expression. Furthermore, Fig. 6a presents a bar plot of feature importance based on SHAP values, revealing that FKBP5 contributes most significantly to the model’s predictive performance among all variables. These findings suggest that FKBP5 may serve as a key driver of the model’s predictive capacity.

Fig. 6.

SHAP-based model interpretation and molecular dynamics simulation analysis. (a) Feature importance ranking derived from SHAP analysis. The summary plot depicts the relative contribution of each variable to the development of the predictive model. (b) SHAP values of continuous variables. Each line represents a feature, with the x-axis indicating the SHAP value. Each dot corresponds to an individual patient, where purple denotes low-risk values and yellow denotes high-risk values. (c) Time-dependent changes in the solvent-accessible surface area of the compound–FKBP5 complex. (d) Temporal evolution of the root mean square deviation. (e) Time-dependent changes in the radius of gyration. (f) Free energy landscape of the compound–FKBP5 interaction

Molecular dynamics simulation

The molecular interactions between BDE-47 and FKBP5 include: the aromatic ring of the ligand forms a Pi-anion interaction with aspartic acid (ASP A:68), and Pi-Pi T-shaped interactions with tyrosine (TYR A:113) and tryptophan (TRP A:90) aromatic rings. The alkyl side chain of isoleucine (ILE A:87) forms an Alkyl interaction with the hydrophobic region of the ligand through van der Waals forces, while the alkyl side chains of phenylalanine (PHE A:77, PHE A:130) and tyrosine (TYR A:57) form Pi-Alkyl interactions with the ligand’s aromatic ring. These interactions together constitute the binding foundation, where Pi-anion and Pi-Pi interactions provide the primary affinity, and Alkyl and Pi-Alkyl interactions enhance the stability and specificity of the binding (Fig. 5b). To further evaluate the binding stability and interaction dynamics between FKBP5 and the compound BDE-47, we conducted molecular dynamics simulations of the FKBP5–BDE-47 complex. The simulation results demonstrated that the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) remained stable with minimal fluctuations throughout the simulation, indicating that the complex maintained structural integrity (Fig. 6c). Root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis revealed that the RMSD trajectories of the FKBP5–BDE-47 complex were nearly superimposed, with fluctuation amplitudes of approximately 0.125 nm, suggesting a high degree of structural stability during the simulation (Fig. 6d). The radius of gyration (Rg) also remained stable across the entire simulation, with no significant fluctuations observed, further supporting the structural stability of the complex (Fig. 6e). The free energy landscape revealed a single, well-defined energy minimum cluster, indicative of favorable thermodynamic stability (Fig. 6f). In addition, hydrogen bond analysis showed that the number of hydrogen bonds between FKBP5 and BDE-47 was consistently maintained at approximately one, providing further evidence of binding stability from a hydrogen bonding perspective (Supplementary Fig. 2m). Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis demonstrated that residue-level fluctuations did not exceed 1 nm, indicating overall conformational stability of the complex throughout the simulation (Supplementary Fig. 2n). MD simulation analysis indicates that the FKBP5–BDE-47 complex maintains structural stability: the RMSD values fluctuate between 0.1 and 0.2 nm, attributed to the conserved conformations of key residues such as Asp68, Ile87, and Phe130. A stable radius of gyration (Rg) suggests a compact structure with a fixed binding pocket location. SAS analysis confirms that the hydrophobic environment contributes to stability. The free energy landscape reveals that the dominant conformational states are supported by a network of residue interactions. The simulation validates that these residues maintain the complex’s stable binding through non-covalent interactions. Collectively, these results suggest that the FKBP5–BDE-47 complex exhibits strong structural stability and favorable binding affinity under dynamic conditions.

Discussion

Environmental pollution is one of the major health threats in modern society. Previous studies have demonstrated that BDE-47 can influence the secretion and signaling of reproductive hormones through two primary mechanisms. First, BDE-47 and its major metabolites act as antagonists of estrogen and androgen receptors. Second, BDE-47 induces alterations in human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels, leading to reduced progesterone secretion and intracellular cAMP levels, which ultimately results in reproductive and developmental toxicity, impairing reproductive function and development [29].In addition, the neurotoxicity of BDE-47 primarily manifests as impairments in sensorimotor functions and learning/memory, with its effects being particularly pronounced during early neurodevelopment. The underlying mechanisms include oxidative stress induction, cholinesterase binding, and signal transduction interference [30].The immunotoxicity of BDE-47 is mediated through two key pathways. First, BDE-47 disrupts thyroid hormone homeostasis, thereby affecting immune function. Second, its metabolite, 6-OH-BDE-47, binds to thyroid hormone transport proteins, interfering with thyroid hormone metabolism and signaling. Furthermore, BDE-47 suppresses granulocyte phagocytosis, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in neutrophils and a reduction in thiol levels within immune cells, collectively resulting in immune dysfunction. Although research on marine organisms is limited, existing studies have shown that BDE-47 reduces pathogen resistance in salmon and induces oxidative stress and impaired phagocytic function in seal immune cells [31].Moreover, BDE-47 has been identified as a cytotoxic compound with hepatotoxic effects in animal models. In murine studies, BDE-47 exposure has been associated with hepatocyte hypertrophy and necrosis, pathological changes that may contribute to liver tumor formation, suggesting a potential carcinogenic risk of this environmental pollutant.

While the associations between environmental pollution and immunotoxicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive and developmental toxicity, and carcinogenicity have been extensively documented, the link between environmental pollutants and OA remains insufficiently explored. Previous studies suggest that BDE-47 may affect cartilage tissue by disrupting endocrine function, immune responses, and mitochondrial activity. However, research on the specific relationship between BDE-47 and OA, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms, is still in its early stages. Against this backdrop, the present study innovatively integrated multiple online databases and successfully identified 30 potential targets associated with BDE-47-induced OA. Through GO and KEGG pathway analyses, we further elucidated the biological functions of these targets. Additionally, leveraging 113 machine learning algorithms, we precisely identified 10 key hub targets involved in BDE-47-induced OA pathogenesis. Subsequent functional and immune-related analyses provided crucial insights into the potential mechanisms by which these core targets contribute to OA progression. Finally, SHAP analysis identified FKBP5 as the gene with the greatest impact on the prediction model. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations demonstrated that the FKBP5–BDE-47 complex exhibited substantial structural stability throughout the simulation period. Specifically, both the solvent-accessible surface area and root mean square deviation profiles showed minimal fluctuations, indicating that the complex maintained a stable conformation. Moreover, binding free energy calculations further corroborated the presence of strong interactions between FKBP5 and BDE-47, highlighting the pivotal role of FKBP5 in mediating the biological effects induced by BDE-47. FK506-binding protein 5 can regulate immune cell functions by targeting and suppressing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β and TNF-α). In osteoclast differentiation regulation, FKBP5 reduces osteoclastogenesis by inhibiting the RANKL signaling pathway, thereby decreasing the risk of bone matrix degradation. Regarding autophagy regulation, FKBP5 maintains chondrocyte autophagy homeostasis by modulating the mTOR signaling pathway. Inflammation factors, osteoclasts, and autophagy are closely related to the pathological mechanisms of osteoarthritis. The excessive release of inflammatory factors and the overactivation of osteoclasts both exacerbate osteoarthritis, while autophagy plays a protective role in OA. These mechanisms indicate that FKBP5 plays a crucial role in maintaining the health of bones and joints. Based on our analysis, we have proven that the toxic substance BDE-47 interacts with FKBP5. Therefore, targeting FKBP5 may provide a potential therapeutic target and theoretical basis for the prevention and treatment of osteoarthritis [32, 33].

This study further investigated the potential functions of the 10 core genes and revealed, through single-gene GSEA, their association with several key biological pathways. These pathways include the adipocytokine signaling pathway, fatty acid metabolism, calcium signaling pathway, p53 signaling pathway, cell cycle regulation, and oxidative phosphorylation. Existing research suggests that both the adipocytokine signaling pathway and fatty acid metabolism contribute to the onset and progression of osteoarthritis through multiple mechanisms, such as modulating inflammatory responses, affecting chondrocyte metabolism and function, and regulating bone metabolism [34]. Moreover, the calcium signaling pathway plays a crucial role in chondrocytes by regulating intracellular calcium ion concentrations, which in turn influences chondrocyte metabolism and function. This dysregulation ultimately leads to reduced cartilage matrix synthesis, increased matrix degradation, and subsequent cartilage degeneration [35]. Aberrant activation of the p50 signaling pathway has been shown to increase chondrocyte apoptosis by triggering a cascade of gene regulatory events. Specifically, it halts cell cycle progression and enhances apoptosis by suppressing cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) [36]. Disruptions in the cell cycle not only impair chondrocytes’ ability to synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM) but also enhance the expression and activity of matrix-degrading enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). This ultimately leads to cartilage matrix degradation and degeneration. Oxidative phosphorylation, a crucial process in cellular energy metabolism, occurs within the mitochondria. In osteoarthritis, mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in excessive production of reactive oxygen species. The accumulation of ROS induces oxidative stress, which damages essential biomolecules in chondrocytes, including DNA, proteins, and lipids. This oxidative damage ultimately compromises chondrocyte function and viability, further exacerbating cartilage degeneration [37].

In our in-depth investigation of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis, we conducted an immune-related analysis and observed a significant increase in the infiltration levels of T cells gamma delta (γδ T cells), activated NK cells, M1 macrophages, and resting dendritic cells in the disease group. Previous studies have demonstrated that γδ T cells promote inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, further amplifying the immune response through interactions with other immune cells. Activated NK cells initiate early inflammatory responses by producing IFN-γ, thereby modulating the activity of other immune cells. M1 macrophages secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and generate reactive oxygen species, exacerbating local joint inflammation and exerting direct cytotoxic effects on chondrocytes. Additionally, resting dendritic cells may contribute to OA pathology through aberrant antigen presentation and cytokine production, thereby disrupting immune homeostasis and exacerbating tissue damage. Collectively, the infiltration and activation of these immune cells play a crucial role in promoting OA-associated inflammation and tissue destruction [38]. In subsequent molecular docking analyses, we further confirmed that all 10 core genes exhibited binding affinity with the environmental pollutant BDE-47. Notably, except for MAFF, the remaining nine core genes demonstrated binding free energies below − 5 kcal/mol, indicating high binding stability. These results offer further evidence that environmental pollutants can directly influence key genes associated with OA, altering their biological roles and elevating the risk of OA development.

This study utilizes advanced techniques, including network toxicology, machine learning, and molecular docking, to systematically analyze the potential toxic targets of environmental pollutants in osteoarthritis, ensuring the accuracy and scientific reliability of the findings. This work establishes a solid theoretical foundation for further exploration of the complex mechanisms underlying osteoarthritis induced by environmental pollutants. By focusing on the molecular interactions between environmental pollutants and osteoarthritis, this study innovatively fills a critical research gap in the field, providing new perspectives and directions for understanding the relationship between environmental pollutants and osteoarthritis. However, certain limitations exist, primarily in that the predicted targets and their mechanisms of action have yet to be fully validated in animal models and cellular experiments. Therefore, future research should incorporate well-designed experimental studies to further substantiate the theoretical inferences presented in this study, thereby providing more direct and reliable evidence for the mechanisms by which environmental pollutants contribute to osteoarthritis.

Conclusion

In this study, we innovatively integrated network toxicology, machine learning, SHAP analysis, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to systematically elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying BDE‑47–induced osteoarthritis. Through rigorous analysis and validation, we identified ten core genes—MAFF, TLR7, RGS1, MXD1, RYR1, PTX3, MGAM, THBS4, CXCL3, and FKBP5—that play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis and progression of BDE‑47–driven OA. Molecular docking experiments further characterized the interaction profiles between BDE‑47 and these core gene products. Our results demonstrate that BDE‑47 spontaneously forms stable complexes with nine of these targets (all except MAFF), suggesting that they may serve as critical mediators of BDE‑47’s effects on OA. Moreover, by applying SHAP to our predictive model, we determined that FKBP5 exerts the most significant influence on model output. We then performed molecular dynamics simulations on the FKBP5–BDE‑47 complex, which revealed sustained structural stability throughout the simulation period, further supporting FKBP5’s feasibility as a potential therapeutic target. Collectively, these findings provide novel molecular‑level insights into how the environmental pollutant BDE‑47 contributes to OA progression and lay a scientific foundation for the development of targeted treatment strategies. Future research should combine in vitro and in vivo experiments to elucidate the functional roles of these key genes in OA and to evaluate their translational potential in clinical settings.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Yu Liu, Guohang Shen and Yupei Dai: Drafted the initial manuscript, conducted the research investigation, performed data analysis, and organized the data. Yu Liu and Guohang Shen: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, provided research supervision, contributed to data analysis and organization, and participated in study conceptualization. Yu Liu, Zidong Xia and Ruoyan Wang: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, provided research supervision, contributed to methodological development and research investigation, and participated in study conceptualization. Zidong Xia, Ruoyan Wang and Guohang Shen: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, contributed to methodological development, and organized the data. Zidong Xia and Ruoyan Wang: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, provided research supervision, contributed to data analysis, and participated in study conceptualization. Yupei Dai: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, contributed to methodological development and research investigation, and participated in study conceptualization.

Funding

None.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study exclusively utilized publicly available, de‑identified bioinformatics datasets and did not involve the collection of new data from human participants or animals; therefore, no ethics committee approval or informed consent was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yu Liu and Guohang Shen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Liu W et al. (2025) Osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances. MedComm (2020) 6:e70290. 10.1002/mco2.70290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Tian W, et al. Genetic transcriptional regulation profiling of cartilage reveals pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. EBioMedicine. 2025;117:105821. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lan Z, et al. A novel signature of cartilage aging-related immunophenotyping biomarkers in osteoarthritis. Comput Biol Med. 2025;187:109816. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2025.109816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunter DJ, et al. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: a lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396:1711–2. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloppenburg M, et al. Osteoarthr Lancet. 2025;405:71–85. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)02322-5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulin D, et al. The role of the immune system in osteoarthritis: mechanisms, challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2025. 10.1038/s41584-025-01223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macaulay LJ, et al. Developmental toxicity of the PBDE metabolite 6-OH-BDE-47 in zebrafish and the potential role of thyroid receptor β. Aquat Toxicol. 2015;168:38–47. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, et al. Toxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics and polybrominated Diphenyl ethers to zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;126:21–33. 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong L, et al. Promotion of mitochondrial fusion protects against developmental PBDE-47 neurotoxicity by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis and suppressing excessive apoptosis. Theranostics. 2020;10:1245–61. 10.7150/thno.40060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohoro CR, et al. Polybrominated Diphenyl ethers in the environmental systems: a review. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2021;19:1229–47. 10.1007/s40201-021-00656-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y, et al. Polybrominated Diphenyl ethers in the environment and human external and internal exposure in china: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2019;696:133902. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, et al. Exposure pathways, levels and toxicity of polybrominated Diphenyl ethers in humans: A review. Environ Res. 2020;187:109531. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson G, et al. Distribution of BDE-99 and effects on metamorphosis of BDE-99 and – 47 after oral exposure in xenopus tropicalis. Aquat Toxicol. 2007;84:71–9. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H, et al. Effects of organophosphate ester flame retardants on endochondral ossification in ex vivo murine limb bud cultures. Toxicol Sci. 2019;168:420–9. 10.1093/toxsci/kfy301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S. Efficient analysis of toxicity and mechanisms of environmental pollutants with network toxicology and molecular Docking strategy: acetyl tributyl citrate as an example. Sci Total Environ. 2023;905:167904. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z, et al. An integrated strategy combining network toxicology and feature-based molecular networking for exploring hepatotoxic constituents and mechanism of epimedii Folium-induced hepatotoxicity in vitro. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023;176:113785. 10.1016/j.fct.2023.113785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patra S, et al. Effects of probiotics at the interface of metabolism and immunity to prevent colorectal Cancer-Associated gut inflammation: A systematic network and Meta-Analysis with molecular Docking studies. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:878297. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.878297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, et al. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1388–95. 10.1093/nar/gkaa971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consortium U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53:D609–17. 10.1093/nar/gkae1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leek JT, et al. The Sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:882–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie ME, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulsen T, et al. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:488. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanehisa M, et al. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–61. 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otasek D, et al. Cytoscape automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 2019;20:185. 10.1186/s13059-019-1758-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, et al. Machine learning-based integration develops an immune-derived LncRNA signature for improving outcomes in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:816. 10.1038/s41467-022-28421-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reimand J, et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:profiler, GSEA, cytoscape and enrichmentmap. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:482–517. 10.1038/s41596-018-0103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makowski L, et al. Immunometabolism: from basic mechanisms to translation. Immunol Rev. 2020;295:5–14. 10.1111/imr.12858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trott O, et al. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–61. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercado-Feliciano M, et al. The polybrominated Diphenyl ether mixture DE-71 is mildly estrogenic. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:605–11. 10.1289/ehp.10643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eriksson P, et al. Brominated flame retardants: a novel class of developmental neurotoxicants in our environment? Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:903–8. 10.1289/ehp.01109903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arkoosh MR, et al. Disease susceptibility of salmon exposed to polybrominated Diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Aquat Toxicol. 2010;98:51–9. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jahr H, et al. Physosmotic induction of chondrogenic maturation is TGF-β dependent and enhanced by calcineurin inhibitor FK506. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. 10.3390/ijms23095110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Li Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and methylation datasets identified ADAMTS9, FKBP5, and PFKBF3 as biomarkers for osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:8908–17. 10.1002/jcp.27557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tu B, et al. Proteomic and lipidomic landscape of the infrapatellar fat pad and its clinical significance in knee osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2024;1869:159513. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2024.159513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, et al. Exercise-induced piezoelectric stimulation for cartilage regeneration in rabbits. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14:eabi7282. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng K, et al. Engineered MSC-sEVs as a versatile nanoplatform for enhanced osteoarthritis treatment via targeted elimination of senescent chondrocytes and maintenance of cartilage matrix metabolic homeostasis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2413759. 10.1002/advs.202413759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. Cascade targeting selenium nanoparticles-loaded hydrogel microspheres for multifaceted antioxidant defense in osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2025;318:123195. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, et al. Microbial succinate promotes the response to Metformin by upregulating secretory Immunoglobulin a in intestinal immunity. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2450871. 10.1080/19490976.2025.2450871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.