Abstract

Objective

Radiation dermatitis (RD) can significantly impact the quality of life in breast cancer (BC) patients undergoing radiation therapy (RT). Barrier products, such as Mepitel Film (MF) and StrataXRT, were reported in the literature to be effective in preventing RD but their efficacy and tolerance in Chinese patients have not been studied. This is a feasibility study of preventing RD in Chinese BC patients with MF and StrataXRT.

Methods

Chinese BC patients from Union Oncology Centre (UOC) who started the use of MF and StrataXRT as RD prophylaxis from August 2023 to December 2023 were retrospectively reviewed. The incidence and severity of RD during treatment, two weeks and 3 months after RT were collected. Patients were assessed by an oncologist or a trained radiation therapist with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and Radiation-Induced Skin Reaction Assessment Scale (RISRAS) (researcher part). Patients completed the Skin Symptom Assessment (SSA) and RISRAS (patient part). Patients’ compliance and side effects were assessed. This study was approved by the Union Hospital Research Ethics Committee (EC033).

Results

Twenty patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, but 3 did not apply the products during the entire course of RT because of skin reactions to the products (1 MF, 2 StrataXRT), leaving 17 evaluable patients. None reported discomfort from product use, and all had good compliance. No grade 3 RD were observed in all evaluable patients. The 2 cohorts appeared to be largely similar in all assessment parameters. The costs of MF (including costs for nursing care) were approximately three folds compared to StrataXRT.

Conclusions

MF and StrataXRT were well tolerated and safe in Chinese BC patients. Larger randomized studies are needed to understand which patients could benefit more from these products.

Keywords: Radiation dermatitis, Mepitel Film, StrataXRT, Breast cancer, Chinese

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common female cancer in Hong Kong. More than 5000 cases of BC were diagnosed in 2021, and more than 90% of these patients had early BCs (stage I to III).1 Many of these women will receive breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy followed by adjuvant radiation therapy (RT).2 RT is an effective treatment in BC (both invasive and in-situ) because it has been shown to reduce locoregional recurrence and improve survival.3 Despite these known benefits, BC patients undergoing adjuvant RT commonly experience radiation dermatitis (RD), which could adversely impact their quality of life.4 These skin toxicities may present in the form of acute reactions including erythema, pruritus or moist desquamation (MD) and late toxicities in the form of hyperpigmentation or fibrosis.5 The development of severe skin toxicities may result in treatment interruptions or increase the risk of reconstructive complications.6,7

Some improvements have been reported through improved RT delivery techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Before the development of IMRT, most breast irradiation was done by conventional three-dimensional conformal RT (3D-CRT), which is a technique that uses a computer to create a 3-dimensional picture of the tumor, allowing a higher dose of radiation to the tumor, while sparing the normal tissue as much as possible.8 IMRT is a newer type of 3-dimensional RT that uses computer-generated images to show the size and shape of the tumor. Thin beams of radiation of different intensities are aimed at the tumor from many angles. This type of RT further reduces the damage to healthy tissue near the tumor.9 Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) is an advanced type of IMRT that allows simultaneous motion of gantry, multileaf collimator and dose rate using dynamic modulated arcs, resulting in increased conformality and enhanced sparing of the critical structures near the target.10 However, the frequency of ≥ grade 2 (G2) RD remains a significant issue regardless of the technique applied (29.2% IMRT group vs. 36.2% conventional postmastectomy RT (PMRT)).4 In addition to the RT delivery technique, hypofractionation has also been reported to reduce RD in multiple RCTs,11, 12, 13 systematic reviews and meta-analyses.14,15 However, despite hypofractionation, some patients still developed grade 3 (G3) skin toxicity (14/401, 3.5%) according to a randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 study in China.11 Patients with large breasts are particularly at risk for developing worse skin toxicities. For example, the incidence of acute G2 or more cutaneous toxicity is significantly higher in patients with a cup size of C or greater (43.3%) compared to those with a cup size of A or B (22.6%).16 Therefore, there is a critical unmet need to prevent RD despite the improvements with RT delivery techniques and hypofractionation.

Barrier films or dressings have been shown to be an effective class of agents to effectively prevent RD in BC patients. Mepitel Film (MF) is a silicone-based soft film which was shown in a phase III randomized trial (n = 376) to be effective in reducing the incidence of G2 or G3 RD compared with standard care (15.5% vs. 45.0% odds ratio: 0.2, P < 0.0001).17 Other than MF, StrataXRT, a silicone-based film-forming gel has shown promise in preventing RD in BC patients. An intra-patient randomized study by Chao et al. showed that StrataXRT is non-inferior to MF in BC patients receiving PMRT.18 A recent systematic review and network metanalysis of 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that both MF and StrataXRT were significantly more effective in reducing the incidence of MD in BC patients compared to standard of care and other interventions.19

There are limited data published in using barrier films or dressings to prevent RD in Chinese BC patients. Free samples of MF and StrataXRT were available for use in the Hong Kong Union Oncology Centre (UOC) since July 2023. To further study and validate the efficacy and safety of these products, a retrospective evaluation was conducted on patients who started the use of MF and StrataXRT as RD prophylaxis from August 2023 to December 2023.

Methods

Study design

BC patients who started the use of MF and StrataXRT as RD prophylaxis from August 2023 to December 2023 were retrospectively reviewed.

At UOC, the clinical oncologist first introduced MF and StrataXRT to patients before irradiation. Patients may choose the product available to them for free or opt not for any prophylactic treatment. MF was applied by trained nursing staff to the MF cohort before the first RT session and was kept on until 2 weeks after completion of RT. Patients received nursing care for reapplication if it had come off before 2 weeks after completion of RT. The StrataXRT cohort was educated on the gel application technique by the clinical oncologist based on the manufacturer's instructions before they started RT treatment so they could apply the gel on their own every day appropriately until 2 weeks after completion of RT.

RT was delivered as prescribed by the treating oncologist and may include a variety of techniques and beam modifiers. Patients received hypofractionated (40 Gy/15 Fr) photon-based radiation and were treated with or without the addition of tissue equivalent bolus or boost (simultaneous integrated or sequential boost using photon or electron beams). The dose to the skin was not a constraint applied for treatment planning.

RD was routinely assessed by the radiation therapist or clinical oncologist with National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and Radiation-Induced Skin Reaction Assessment Scale (RISRAS) (researcher part). Patients also completed the Skin Symptom Assessment (SSA) and RISRAS (patient part) (Appendix). The assessments by the patients and the healthcare professionals (HCPs) were performed at baseline before RT, weekly during the RT, the last RT, and 2 weeks and 3 months after the completion of RT. This retrospective study was approved by the Union Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee Reference No. EC033).

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with histological confirmation of BC (invasive or in situ carcinoma) who received MF or StrataXRT during their RT course were included in the study. All patients who started the use of MF and StrataXRT as RD prophylaxis from August 2023 to December 2023 were included. Verbal consent was obtained from all patients, including the use of their data and clinical photos for this study anonymously.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had prior RT to the treatment area or if they received partial breast external beam radiation or brachytherapy.

Primary objectives

The primary objectives were to determine the incidence of acute RD as defined by NCI CTCAE v5.0 and to evaluate the tolerability of MF and StrataXRT during RT in Chinese BC patients.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to assess patient-reported skin-related symptoms using the SSA and RISRAS evaluated by both patients and HCPs.

Data collection

A retrospective chart review was conducted to collect patient baseline characteristics, including age, breast size, disease characteristics, and RT treatment details (Appendix). Information from weekly skin assessments and post RT evaluations conducted by HCPs were retrieved to assess skin toxicity. Any significant discomfort experienced by patients during or after treatment due to MF or StrataXRT was documented by the HCPs.

Data analysis

The incidence and severity of RD were reported for each cohort. Other skin reactions and radiation-induced side effects were assessed and documented using SSA, RISRAS, and CTCAE toxicities at baseline, during RT at the first week (R1W), second week (R2W), and third week (R3W), and at follow-up intervals: two weeks after RT (FU2W), 3 months after RT (FU3M), and at the worst recorded scores during or after RT.

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

A total of 20 patients met inclusion criteria, with 10 patients in each cohort treated with MF and StrataXRT. Three patients (3/20, 15.0%) discontinued the products early due to skin reactions and were analyzed separately from patients who completed RT with the products used throughout the entire course of RT.

Patient and treatment characteristics of those who completed RT with the two products are summarized in Table 1. The RT technique most commonly employed across both groups was VMAT. Twelve patients (12/17, 70.6%) had a small cup size of A or B. The costs for using MF were approximately threefold higher than those for StrataXRT due to additional nursing care fee required. For MF, patients with cup sizes A–C required United States dollar (USD) 310 per course, while those with cup size D or larger required USD 620 per course. In contrast, only 1–2 tubes of StrataXRT were required per course, with each tube costing USD 90.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics.

| Characteristics | StrataXRT (n = 8) | Mepitel Film (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean: 47.3 | Mean: 48.9 |

| Median: 43.0 | Median: 48.0 | |

| Range: 37.0–63.0 | Range: 41.0–57.0 | |

| SD: 9.8 | SD: 5.7 | |

| Breast surgery type, n (%) | ||

| Wide local excision | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Mastectomy and reconstruction | 3 (37.5%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Mastectomy | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Systemic treatment, n (%) | ||

| Prior chemotherapy | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Hormonal therapy | 6 (75.0%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| Anti-HER2 target therapy (trastuzumab ± pertuzumab) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Radiation technique | ||

| VMAT | 7 (87.5%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| 3D-CRT | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Bolus | 2 (25.0%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Radiation dose, n (%) | ||

| 40 Gy/15 Fr | 5 (62.5%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| 40 Gy/15 Fr with SIB to 48 G/15 Fr | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| Cup size, n (%) | A: 2 (25.0%) | A: 3 (33.3%) |

| B: 3 (37.5%) | B: 4 (44.4%) | |

| C: 2 (25.0%) | C: 2 (22.2%) | |

| E: 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Band size | Mean: 32.0 | Mean: 30.8 |

| Median: 32.0 | Median: 31.0 | |

| Range: 30.0–34.0 | Range: 27.0–35.0 | |

| SD: 1.7 | SD: 2.7 | |

| Budget | 1-2 tubes | Cup A-C: USD 310/course |

| USD 90/tube | Cup D or overall: USD 620/course | |

SD, Standard Deviation; VMAT, Volumetric modulated arc therapy; 3D-CRT, three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy; SIB, simultaneous integrated boost.

The skin dose data (Dmax, Dmean, and V40; and their respective means, standard deviations (SD), medians, minimums and maximums) for those who did not have bolus are summarized in Table 2, while the skin dose data (Dmax, Dmean, and V40; and their respective means and SD) of those who had bolus were separated into Table 3. The skin doses to the MF cohort were numerically similar to that of the StrataXRT cohort.

Table 2.

Skin dose data of all included patients except those who had bolus.

|

Mepitel Film |

2 mm Skin Dose |

3 mm Skin Dose |

5 mm Skin Dose |

Skin volumea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT Plan Remarks | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | V40 (cc) |

| SCF + IMC | 40.4 | 23.3 | 41.8 | 25.7 | 43.1 | 28.9 | 0.5 |

| SIB 48 Gy | 46.8 | 23.7 | 48.8 | 26.2 | 51.0 | 29.7 | 3.6 |

| Tang. opp. | 41.2 | 20.8 | 41.7 | 22.7 | 41.9 | 25.2 | 2.2 |

| SCF + IMC | 41.2 | 23.2 | 42.6 | 25.5 | 43.7 | 28.7 | 1.7 |

| SCF + IMC | 39.9 | 24.4 | 41.1 | 26.8 | 42.7 | 30.0 | 0.3 |

| SCF + IMC | 42.2 | 25.0 | 42.5 | 27.1 | 43.8 | 30.5 | 2.6 |

| SIB 48 Gy, SCF + IMC | 46.1 | 24.6 | 48.5 | 27.0 | 51.9 | 30.3 | 3.0 |

| SIB 48 Gy; SCF + IMC | 43.6 | 21.8 | 45.9 | 24.0 | 50.4 | 27.0 | 1.4 |

| Mean | 42.7 | 23.3 | 44.1 | 25.6 | 46.1 | 28.8 | 1.9 |

| SD | 2.6 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Median | 41.7 | 23.5 | 42.5 | 26.0 | 43.8 | 29.3 | 1.9 |

| Min | 39.9 | 20.8 | 41.1 | 22.7 | 41.9 | 25.2 | 0.3 |

| Max | 46.8 | 25.0 | 48.8 | 27.1 | 51.9 | 30.5 | 3.6 |

|

StrataXRT |

22 mm skin dose |

33 mm skin dose |

55 mm skin dose |

Skin volumea |

|||

| RT Plan Remarks | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | V40a(cc) |

| SCF + IMC | 42.1 | 29.6 | 43.1 | 30.4 | 43.5 | 31.6 | 0.9 |

| Tang. opp. | 40.8 | 20.9 | 41.4 | 22.7 | 42.6 | 25.4 | 1.1 |

| SCF + IMC | 41.0 | 23.5 | 42.6 | 25.8 | 43.9 | 28.9 | 1.3 |

| SIB 48 Gy | 47.7 | 27.1 | 44.7 | 24.6 | 50.4 | 30.4 | 3.9 |

| SIB 48 Gy | 41.9 | 24.6 | 44.0 | 27.0 | 47.0 | 30.4 | 1.6 |

| SIB 48 Gy | 44.3 | 24.9 | 46.0 | 27.4 | 49.0 | 30.9 | 3.4 |

| SCF + IMC | 41.4 | 25.0 | 41.7 | 27.1 | 42.8 | 30.4 | 1.2 |

| Mean | 42.8 | 25.1 | 43.4 | 26.4 | 45.6 | 29.7 | 1.9 |

| SD | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| Median | 41.9 | 24.9 | 43.1 | 27.0 | 43.9 | 30.4 | 1.3 |

| Min | 40.8 | 20.9 | 41.4 | 22.7 | 42.6 | 25.4 | 0.9 |

| Max | 47.7 | 29.6 | 46.0 | 30.4 | 50.4 | 31.6 | 3.9 |

|

All included patients |

2 mm skin dose |

3 mm skin dose |

5 mm skin dose |

Skin volumea |

|||

| Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | V40 (cc) | |

| Mean | 42.7 | 24.2 | 43.8 | 26.0 | 45.9 | 29.2 | 1.9 |

| SD | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Median | 41.9 | 24.4 | 42.6 | 26.2 | 43.8 | 30.0 | 1.6 |

| Min | 39.9 | 20.8 | 41.1 | 22.7 | 41.9 | 25.2 | 0.3 |

| Max | 47.7 | 29.6 | 48.8 | 30.4 | 51.9 | 31.6 | 3.9 |

RT, radiation therapy; SD, Standard Deviation; SCF, supraclavicular fossa; IMC, internal mammary chain; SIB, simultaneous-integrated boost; Tang. opp., tangential opposing.

V40 (skin volume) was calculated by V40 (whole body) minus V40 (whole body minus 3 mm).

Table 3.

Skin dose data of patients with bolus.

| 2 mm Skin Dose |

3 mm Skin Dose |

5 mm Skin Dose |

Skin volumea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | RT Plan Remarks | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | Dmax (Gy) | Dmean (Gy) | V40a (cc) |

| MepitelFilm | SCF + IMC Alternate day bolus |

42.0 | 30.1 | 43.1 | 31.2 | 43.7 | 32.3 | 13.0 |

| StrataXRT | SCF + IMC Daily bolus | 43.7 | 34.1 | 43.7 | 34.4 | 43.7 | 34.9 | 89.7 |

| Mean | 42.9 | 32.1 | 43.4 | 32.8 | 43.7 | 33.6 | 51.3 | |

| SD | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 54.2 | |

RT, radiation therapy; SD, Standard Deviation; SCF, supraclavicular fossa; IMC, internal mammary chain.

V40 (skin volume) was calculated by V40 (whole body) minus V40 (whole body minus 3 mm).

Incidence of RD by CTCAE and MD from RISRAS (HCP)

The incidences of the highest grade of RD recorded using CTCAE and MD from RISRAS assessment (HCP component) throughout the study period are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Incidence of the Highest Grade of Radiation Dermatitis (CTCAE) Recorded and Moist Desquamation (MD) from RISRAS assessment (researcher component).

| Description | StrataXRT (n = 8) | Mepitel Film (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| CTCAE grade | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| 1 | 5 (62.5%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| 2 | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| 3 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Moist desquamation (extracted from RISRAS-researcher component) | ||

| No | 6 (75.0%) | 9 (100.0%) |

| Yes | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; RT, radiation therapy; RISRAS, Radiation-Induced Skin Reaction Assessment Scale.

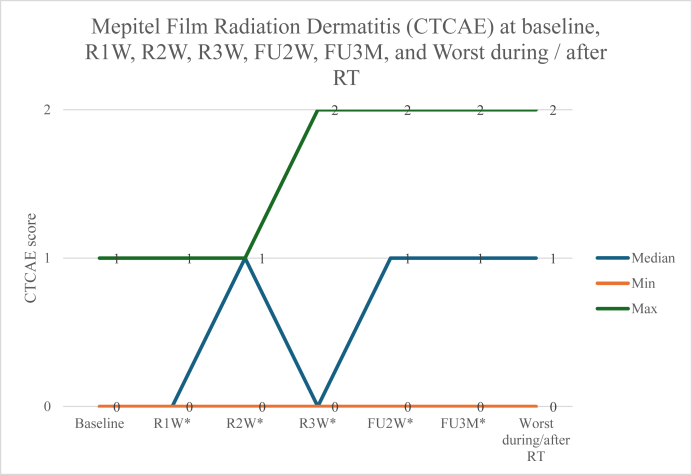

The CTCAE grade of RD at baseline, R1W, R2W, R3W, FU2W, FU3M, and the worst scores during/after RT were numerically similar between the two cohorts (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). No patients developed G3 RD with either product. Two of nine patients (22.2%) in the MF cohort had G2 RD, while three out of eight (37.5%) in the StrataXRT cohort had G2 RD. Two of eight patients (25.0%) in the StrataXRT cohort developed MD during RT, while none in the MF cohort experienced MD.

Fig. 1.

StrataXRT Radiation Dermatitis (CTCAE) at baseline, R1W, R2W, R3W, FU2W, FU3M, and Worst during / after RT. During RT at the first week (R1W), second week (R2W), and third week (R3W), and at follow-up intervals at two weeks after RT (FU2W) and 3 months after RT (FU3M). CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; RT, radiation therapy.

Fig. 2.

Mepitel Film Radiation Dermatitis (CTCAE) at baseline, R1W, R2W, R3W, FU2W, FU3M, and Worst during / after RT. CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; RT, radiation therapy. ∗During RT at the first week (R1W), second week (R2W), and third week (R3W), and at follow-up intervals at two weeks after RT (FU2W) and 3 months after RT (FU3M).

Skin-related symptoms from SSA and RISRAS (patient) and (HCP)

For patient-reported skin-related symptoms assessed by SSA, patients treated with MF reported numerically lower pain scores from RD starting from the first week of RT to two weeks post-RT (Table 5). At R1W, the MF cohort had a mean pain score of 0, while the StrataXRT cohort had a mean pain score of 0.6. At R2W, the MF cohort had a mean pain score of 0.1, while the StrataXRT cohort had a mean pain score of 0.6. At R3W, the MF cohort had a mean pain score of 0.1, while the StrataXRT cohort had a mean pain score of 0.9. At FU2W, the MF cohort had a mean pain score of 0.1, while the StrataXRT cohort had a mean pain score of 1.

Table 5.

Patient-Assessed SSA at baseline, R1W, R2W, R3W, FU2W and FU3M.

| Symptom / Timepoint |

StrataXRT (n = 8) Mean ± SD |

Mepitel Film (n = 9) Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Pruritus (Itchiness) | ||

| Baseline | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| R1Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 |

| R2Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| R3Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| FU2Wa | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| FU3Ma | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| Pain (Soreness) | ||

| Baseline | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| R1Wa | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R2Wa | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R3Wa | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| FU2Wa | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| FU3Ma | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| Blistering (Peeling) | ||

| Baseline | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R1Wa | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R2Wa | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R3Wa | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| FU2Wa | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| FU3Ma | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Erythema (Redness) | ||

| Baseline | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| R1Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| R2Wa | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| R3Wa | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.7 |

| FU2Wa | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.7 |

| FU3Ma | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| Pigmentation (discolouration/darkness) | ||

| Baseline | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R1Wa | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R2Wa | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R3Wa | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| FU2Wa | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| FU3Ma | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| Edema (Swelling) | ||

| Baseline | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.7 |

| R1Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R2Wa | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R3Wa | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| FU2Wa | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| FU3Ma | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| Trouble fitting brassieres | ||

| Baseline | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| R1Wa | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R2Wa | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| R3Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| FU2Wa | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| FU3Ma | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

RT, radiation therapy; SD, Standard Deviation; SSA, Skin Symptom Assessment.

During RT at the first week (R1W), second week (R2W), and third week (R3W), and at follow-up intervals at two weeks after RT (FU2W) and 3 months after RT (FU3M).

There were only minimal differences between the two cohorts for most SSA parameters (Table 5) or RISRAS (assessed by both patients and HCPs, Table 6).

Table 6.

HCP and Patient-Assessed RISRAS and total RISRAS at baseline, R1W, R2W, R3W, FU2W and FU3M.

| HCP-Assessed RISRAS Timepoint |

StrataXRT (n = 8) Mean ± SD |

Mepitel Film (n = 9) Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| R1Wa | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| R2Wa | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| R3Wa | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 1.1 |

| FU2Wa | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| FU3Ma | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

|

Patient-assessed RISRAS Timepoint |

StrataXRT (n = 8) Mean ± SD |

MepitelFilm (n = 9) Mean ± SD |

| Baseline | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.7 |

| R1Wa | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| R2Wa | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 1.2 |

| R3Wa | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.2 |

| FU2Wa | 2.8 ± 2.5 | 1.4 ± 1.6 |

| FU3Ma | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 0.9 |

|

Total RISRAS Timepoint |

StrataXRT (n = 8) Mean ± SD |

MepitelFilm (n = 9) Mean ± SD |

| Baseline | 0.9 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.9 |

| R1Wa | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 0.9 |

| R2Wa | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 1.5 |

| R3Wa | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 2.4 ± 1.7 |

| FU2Wa | 4.9 ± 4.0 | 2.2 ± 2.1 |

| FU3Ma | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.7 ± 0.9 |

HCP, healthcare professional; SD, Standard Deviation; RISRAS, Radiation-Induced Skin Reaction Assessment Scale.

During RT at the first week (R1W), second week (R2W), and third week (R3W), and at follow-up intervals at two weeks after RT (FU2W) and 3 months after RT (FU3M).

Tolerability of the products

Among the 17 patients who used the products during RT, none experienced significant toxicities requiring interruption of RT, and none had to discontinue product use. Three additional patients tried the products but stopped early due to skin reactions (two from StrataXRT and one from MF). A patch test for MF was conducted before starting product use in the 10 patients who tried it, and no allergic reactions were observed during test. However, one patient developed a skin rash 11 days after starting MF (Fig. 3). For the StrataXRT group, skin rash appeared 1 day and 1 week after use in two patients (Fig. 4). For all three patients, the skin rash resolved after discontinuation of the product. The rash was mild, self-limiting, and required no additional management. RT was not interrupted due to these skin reactions. None of the three patients developed G3 RD or MD. More side effects were noted during the post-RT two-week assessment, but all were mild.

Fig. 3.

Skin rash from MF. MF: Mepitel Film.

Fig. 4.

Skin rash from StrataXRT∗. ∗The patient applied the gel to areas other than the radiation field and the rash appeared at the areas of gel application.

Discussion

To date, most clinical trials performed on prophylactic interventions for breast RD were on Caucasian patients, with limited literature in Asian BC patients.19 Our study showed that the two products were well tolerated and safe among Chinese BC patients except for skin reactions in 3 patients among 20, and a low incidence of RD and MD with the use of the 2 products. Our retrospective review showed that MF and StrataXRT were tolerable and safe in most of our Chinese patients, with only 15.0% of patients who developed skin reactions to the products. Such skin reactions have also been reported in the literature. For MF, Møller et al. reported that 12 out of 101 patients (11.9%) withdrew from the study due to skin rash or itchiness in the film area.20 Herst et al. reported that 3 out of 93 patients (3.2%) developed a rash underneath the MF test patch and were not recruited, while 7 out of 42 patients (16.7%) withdrew because of severe itching, erythema and heat underneath MF.21 As for StrataXRT, Chan et al. reported that there were no adverse events/allergic events in the use of StrataXRT for RD prophylaxis in patients with head and neck cancer. However, it could be due to the exclusion of any known allergy to the study products at enrolment.22 A systematic review and meta-analysis showed no additional safety concerns or toxicity issues associated with StrataXRT use.23 Other than the skin reactions, there were no other adverse side effects noted in our cohort. Specifically for MF, most included patients tolerated the entire process of applying the product and complied to continue treatment as instructed throughout the RT course despite the warm and humid climate in Hong Kong. These promising results can guide larger scale studies in the future to better compare the 2 products’ efficacy and safety in Chinese BC patients.

In our study, the MF cohort had numerically lower rates of G2 RD, MD and less patient-reported pain from RD compared to the StrataXRT cohort. Such results are considered exploratory as our results are limited by the sample size and appropriate statistical tests could not be applied. However, a recently published intra-patient non-inferiority randomized clinical trial comparing StrataXRT and MF for preventing post-mastectomy acute RD showed that StrataXRT was inferior to MF. In the primary outcome, the time-weighted average (TWA) grade of acute RD was lower in the MF half compared to the StrataXRT half over 10 weeks from the commencement of RT, with a mean difference in TWA grade of 0.2 (95% confidence interval: 0.1–0.3; P < 0.001).24 A possible reason for the higher efficacy of MF in preventing RD may be due to the different designs of the products. MF is a reliable physical barrier that firmly adheres to the skin and protects the skin from friction, whereas StrataXRT is a film forming agent applied in the form of a gel. The agent could be scratched off during treatment, for example when patients change their clothes or take off their brassieres. Ideally, the product should be kept on all the time throughout the intended course. Scratching off the products without reapplication may be a reason for MF being more effective in preventing RD compared to StrataXRT.

The low incidence of RD observed in our cohort needs to be interpreted with caution. Chinese BC patients have smaller breast sizes compared to Caucasian patients,25 and it is known that patients with smaller breasts have a lower risk of RD.26 Majority of our patients (12/17, 70.6%) had a cup size of A or B, and all had a band size of 27–35. Other than breast sizes, Chinese and Caucasian BC patients also differ in their skin tones. Acute RD may be underdiagnosed in patients with skin-of-colour compared to Caucasians when using a physician-rated scale.27 G2 RD without MD may be underreported in our cohort of patients with darker skin tones compared to the Caucasian cohorts.

The low incidence of RD in our cohort could also be contributed by the RT technique and skin doses. Most patients in our cohort were treated with VMAT with a hypofractionated schedule (15/17, 88.2%). Inverse planning with IMRT has been shown to cause less RD than 3D-CRT.28 Hypofractionation was also shown to be non-inferior to conventional fractionation in efficacy and safety, and could reduce the incidence of acute RD compared to conventional fractionation in multiple RCTs,11, 12, 13 systematic reviews and meta-analyses.14,15 Takenaka et al. reported that the rate of ≥ G2 RD was significantly higher for patients for patients with V40 (skin volume) > 45 cc compared with those with V40 (skin volume) ≤ 45 cc (50.0% vs. 18.0%, P < 0.005). In their study, V40 (skin volume) was calculated by subtracting V40 (whole body minus 3 mm) from V40 (whole body).29 From Table 2, the V40 (skin volume) of most of our patients were much lower than 45 cc, rendering our patients at a lower risk of developing severe RD. As for those who had skin bolus, their V40 (skin volume) were higher than those who did not have bolus. It is worth noting that in one of the patients who used StrataXRT, the V40 (skin volume) was 89.7 cc. She experienced G2 RD with MD. As for the one who used MF, she had a V40 (skin volume) of 13.0 cc and only experienced G1 RD. The skin doses could have affected the severity of RD but the products could have contributed to a certain extent as well. However, given the small sample size and lack of a control group, it is uncertain whether the low incidence of severe RD is a result of the RT technique, patients’ baseline low risk of RD or the products.

This study also has several limitations. First, our study is an exploratory study with a small sample size, which limits the use of statistical tests to evaluate whether there were significant differences between the two cohorts. There is variability in skin doses among our patients, as a stringent skin dose constraint protocol was not defined a priori. Prospective studies with a larger sample size should be carried out with predefined skin dose-volume constraints to generate more robust comparisons. In addition, there is a lack of a standard of care group as control to compare the incidence of RD and MD with the use of these products. The encouraging findings on product tolerability from our study may support future research incorporating control groups to better determine the products' role in reducing RD severity amongst other factors.

Considering these limitations, RCTs designed specifically for Chinese BC patients with stratification of RT technique (the use of 3D-CRT vs. IMRT), type of surgery (mastectomy vs. breast conserving surgery), radiation target (local vs loco-regional radiation) and breast size (small vs. large breasts) are needed to compare the two products and provide information on which patients benefit more from these interventions. A cost-effectiveness study should also be done in Chinese patients, considering the relatively high costs of the products and the additional nursing time involved in educating patients and applying the products (in the case of MF). This study would be especially important to inform practice for Asian patients, as they may have a baseline lower risk of RD without any prophylactic treatments. Furthermore, a patient preference study comparing the perceptions of the two products would be helpful to understand which patient subgroups may opt for a physical film such as MF or a film forming gel. Our study also identified that there was a discrepancy between clinician reported and patient reported outcomes. It concurs with another study concluding that clinicians reported significantly less acute breast pain than patients.30 There is a need to better define standard assessment tools incorporating both patient and clinician reported outcomes to assess the effectiveness of different prophylactic interventions. Perception of pain is a rather subjective parameter and is easily affected by mood such as anxiety.31 Apart from physical assessments, future studies incorporating quality of life tools may help to correlate with patients’ symptoms of RD and changes in their emotions during RT. It would also be of interest to investigate the prevention of chronic skin toxicity from these two interventions.

Conclusions

MF and StrataXRT were well tolerated and safe in Chinese BC patients. Larger prospective cohort studies and dedicated RCTs in Chinese patients with a control group are required to understand their relative benefits and cost effectiveness compared to standard of care.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cindy LS Wong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original and revised draft preparation. Amy WS Lo: Formal analysis, Writing - Original and revised draft preparation. Match KP Ip: Data collection. Lavender KF Chan: Data collection. Harry CY Cheng: Writing - Revised draft preparation. Shing Fung Lee: Writing - Revised draft preparation. Edward Chow: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Revised draft preparation. Henry CY Wong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Revised draft preparation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Union Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. EC033) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards. Patient identities were kept strictly confidential and remain anonymous in all presentations and publications.

Data availability statement

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

No AI tools/services were used during the preparation of this work.

Funding

StrataXRT was provided for free by StratPharma AG. MF was provided free by Molnlycke for this study and the studies with Edward Chow. The companies did not participate in study design, patient recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation, report writing, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

StrataXRT was provided free of charge by StratPharma AG, and MF was provided at no cost by Mölnlycke for this study and other studies involving Edward Chow. The companies had no role in the design of the study, recruitment of participants, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors independently take full responsibility for the decision to submit this work for publication. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjon.2025.100769.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hong_Kong_Cancer_Registry Female breast cancer in 2021. Hospital authority. https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/factsheet/2021/breast_2021.pdf

- 2.Chen D., Lai L., Duan C., et al. Conservative surgery plus axillary radiotherapy vs. modified radical mastectomy in patients with stage I breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(1):e10–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darby S., McGale P., et al. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative G Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1707–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignol J.P., Vu T.T., Mitera G., et al. Prospective evaluation of severe skin toxicity and pain during postmastectomy radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kole A.J., Kole L., Moran M.S. Acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients: challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer. 2017;9:313–323. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S109763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kronowitz S.J., Robb G.L. Radiation therapy and breast reconstruction: a critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):395–408. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parekh A., Dholakia A.D., Zabranksy D.J., et al. Predictors of radiation-induced acute skin toxicity in breast cancer at a single institution: role of fractionation and treatment volume. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.3D-CRT. National Cancer Institute. 21 April 2025. 2025. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/3d-crt 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 9.IMRT. National Cancer Institute. 21 April 2025. 2025. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/imrt 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunte S.O., Clark C.H., Zyuzikov N., Nisbet A. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT): a review of clinical outcomes-what is the clinical evidence for the most effective implementation? Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1136) doi: 10.1259/bjr.20201289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S.L., Fang H., Song Y.W., et al. Hypofractionated versus conventional fractionated postmastectomy radiotherapy for patients with high-risk breast cancer: a randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):352–360. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S.L., Fang H., Hu C., et al. Hypofractionated versus conventional fractionated radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in the modern treatment era: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial from China. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(31):3604–3614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmeel L.C., Koch D., Schmeel F.C., et al. Acute radiation-induced skin toxicity in hypofractionated vs. conventional whole-breast irradiation: an objective, randomized multicenter assessment using spectrophotometry. Radiother Oncol. 2020;146:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrade T.R.M., Fonseca M.C.M., Segreto H.R.C., et al. Meta-analysis of long-term efficacy and safety of hypofractionated radiotherapy in the treatment of early breast cancer. Breast. 2019;48:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marta G.N., Riera R., Pacheco R.L., et al. Moderately hypofractionated post-operative radiation therapy for breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Breast. 2022;62:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquier D., Le Tinier F., Bennadji R., et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost for locally advanced breast cancer: a prospective study on toxicity and quality of life. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2759. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39469-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behroozian T., Milton L., Karam I., et al. Mepitel film for the prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer: a randomized multicenter open-label phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. Feb 20 2023;41(6):1250–1264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao M., Spencer S., Kai C., et al. ESTRO Programme Book & Exhibition Guide; 2019. Strataxrt is Non Inferior to Mepitel Film in Preventing Radiation Induced Moist Desquamation. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong H.C.Y., Lee S.F., Caini S., et al. Barrier films or dressings for the prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024;207(3):477–496. doi: 10.1007/s10549-024-07435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moller P.K., Olling K., Berg M., et al. Breast cancer patients report reduced sensitivity and pain using a barrier film during radiotherapy - a Danish intra-patient randomized multicentre study. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2018;7:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herst P., van Schalkwyk M., Baker N., et al. Mepitel film versus StrataXRT in managing radiation dermatitis in an intra-patient controlled clinical trial of 80 postmastectomy patients. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2025;69(4):440–446. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.13850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan R.J., Blades R., Jones L., et al. A single-blind, randomised controlled trial of StrataXRT(R) - a silicone-based film-forming gel dressing for prophylaxis and management of radiation dermatitis in patients with head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2019;139:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S.F., Shariati S., Caini S., et al. StrataXRT for the prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(9):515. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S.F., Yip P.L., Spencer S., et al. StrataXRT and mepitel film for preventing postmastectomy acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer: an intrapatient noninferiority randomized clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2024;121(5):1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2024.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maskarinec G., Meng L., Ursin G. Ethnic differences in mammographic densities. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(5):959–965. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernando I.N., Ford H.T., Powles T.J., et al. Factors affecting acute skin toxicity in patients having breast irradiation after conservative surgery: a prospective study of treatment practice at the royal marsden hospital. Clin Oncol. 1996;8(4):226–233. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purswani J.M., Bigham Z., Adotama P., et al. Risk of radiation dermatitis in patients with skin of color who undergo radiation to the breast or chest wall with and without regional nodal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;117(2):468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi K.H., Ahn S.J., Jeong J.U., et al. Postoperative radiotherapy with intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy in early breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial of KROG 15-03. Radiother Oncol. 2021;154:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takenaka T., Yamazaki H., Suzuki G., et al. Correlation between dosimetric parameters and acute dermatitis of post-operative radiotherapy in breast cancer patients. In Vivo. 2018;32(6):1499–1504. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam E., Yee C., Wong G., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinician-reported versus patient-reported outcomes of radiation dermatitis. Breast. 2020;50:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gogou P., Tsilika E., Parpa E., et al. The impact of radiotherapy on symptoms, anxiety and QoL in patients with cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(3):1771–1775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.