Summary

Self-powered degradation (SPD) driven by the triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) has attracted significant attention. However, the effects of TENG on the migration of organic molecules have not been fully explored. Herein, a simultaneous enrichment and degradation mechanism of organic molecules around the electrode in the TENG electric field is proposed by in-situ surface enhancement of Raman scattering (SERS). In-situ SERS reveals that in the TENG electric field, the characteristic peaks intensity of organic molecules exhibits dynamic trend of “initial enhancement followed by attenuation.” In the early degradation stages, the enrichment of organic molecules around the electrode exceeds the degradation quantity. As the reaction progresses, the enrichment gradually decreases, and degradation becomes dominant, leading to SERS intensity reduction. This phenomenon differs significantly from the molecular migration in the DC electric field. This work reveals the unique migration mechanism of organic molecules in the TENG electric field and provides theoretical support for SPD applications.

Subject areas: Electrochemistry, Electronic materials, Energy materials, Materials science

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

In-situ SERS technology is used in degradation system powered by TENG

-

•

The simultaneous enrichment and degradation of molecules is proposed

-

•

The SERS is used as both the negative electrode and the degradation catalyst

Electrochemistry; Electronic materials; Energy materials; Materials science

Introduction

Rapid industrialization and urbanization have led to the discharge of large quantities of untreated wastewater into the environment.1,2 These wastewaters contain a variety of organic and inorganic pollutants and harm ecosystems, including plants, animals, and humans. Various pollutant treatment technologies have been proposed,3,4,5 including advanced oxidation processes, physicochemical method, enzymatic decomposition, and electrocatalytic degradation et al. Advanced oxidation processes use strong oxidants, such as hydroxyl radicals, to decompose pollutants, with fast reaction rates, but may produce secondary pollutants and high energy consumption.6 Adsorption and filtration are examples of physicochemical processes that change the physical and chemical properties of substances, which are simple and cost-effective, but are limited to specific pollutants.7 Enzymatic decomposition is the use of enzymes to break down complex organic chemicals into simpler molecules. However, the performance of enzymes is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, which limits their scope of application.8 In contrast, electrocatalytic degradation can efficiently treat wastewater containing a variety of organic and inorganic pollutants by directly oxidizing or reducing pollutants on the electrode surface.9,10,11 This method has the characteristics of strong adaptability, simple operation, environmental protection, low temperature operation, and higher treatment efficiency, but is limited by high energy consumption. As an alternative attempt, a green, sustainable, energy-saving and low-cost energy-harvesting technology can be used to replace the use of traditional direct-current (DC) power in the electrocatalytic degradation process, thereby effectively solving the problems related to high energy consumption.

Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) based on the principles of contact electrification and electrostatic induction have garnered significant attention due to their ability to harvest high-entropy mechanical energy from environmental sources, such as vibrations, wind, water waves, raindrops, and human motion.12,13,14,15 This ability enables TENGs to excel in applications, such as micro/nano energy harvesting, self-powered sensing, blue energy generation, and high-voltage power et al.16,17,18,19 Beyond these applications, TENGs are also widely integrated into self-powered electrochemical systems for applications in chemical synthesis, organic degradation, and heavy metal adsorption and removal.20,21,22 By combining TENGs with various catalysts and electrodes, catalytic degradation of chemical pollutants without external DC power can be achieved.23,24 TENGs-driven pollutant treatment processes produce minimal secondary pollutants, which is particularly suitable for remote or harsh areas.25,26,27 They provide a renewable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly solution that not only reduces environmental and public health risks but also alleviates the global energy burden.28,29 Due to the inherent high voltage and low current characteristics of the TENGs,30,31 which differ significantly from the low voltage and high current characteristics of traditional DC power, organic dye molecules exhibit a unique migration and degradation mechanism in the TENGs electric field. However, the migration behavior of organic dye molecules around the electrode under the influence of the TENGs electric field and its impact on the degradation mechanism remains underexplored. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms will not only clarify the specific role of TENGs in degrading organic dyes but also help to define their applicability across different scenarios.

Herein, a simultaneous enrichment and degradation mechanism of organic molecules around the electrode in the TENG electric field is proposed by in-situ surface enhancement of Raman scattering (SERS). The in-situ SERS monitoring system for self-powered degradation includes TENG, SERS device, and in-situ electrolytic cell. Among them, the Ag@NF prepared by in-situ growth method simultaneously acts as the electrode of the in-situ electrolytic cell to achieve the degradation of organic molecules, and serve as SERS substrate to not only achieve molecular trace detection with concentration as low as 10−5 mol/L, but also analyze the degradation timing characteristics of different characteristic peaks of organic molecules. In-situ SERS reveals that under the influence of the TENG electric field, the SERS intensity of characteristic peaks in the organic molecules exhibits a dynamic trend of “initial enhancement followed by attenuation.” This phenomenon differs significantly from the molecular migration in the DC electric field, that is, the organic molecules undergo direct degradation without enrichment behavior in DC electric field. This work reveals the unique migration mechanism of organic molecules in the TENG electric field and provides theoretical support for self-powered degradation applications.

Results

Material preparation and in situ SERS system design

The nickel foam (NF) with high specific surface area is used as the substrate material, and the in-situ growth method is adopted to make the silver (Ag) particles grow uniformly on substrate surface, as shown in Figure 1A. Concretely, silver nitrate (AgNO3) is dissolved in water and stirred with a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 1 h to ensure uniform mixing to obtain an AgNO3 solution. Next, the NF is immersed in the AgNO3 solution. Among them, the microscopic surface of NF before immersion is a smooth surface, which provides a stable support for the growth of silver particles. As Ag+ in the solution gradually deposit, Ag particles begin to form and grow on the NF surface. The reaction is conducted at 60 °C for 40 min, during which the Ag particles progressively cover the NF surface, resulting in the formation of an Ag@NF composite material. The microscopic morphology shows that Ag particles are evenly distributed on the NF surface. Figure 1B shows an in-situ SERS monitoring system for self-powered degradation based on R-TENG. The actual picture of R-TENG is shown in Figure S1. It includes a rotating triboelectric nanogenerator (R-TENG), a SERS device, and an in-situ electrolytic cell. The R-TENG consists of a rotor and a stator based on PLA material, 6 PTFE friction layers, and 6 copper electrodes. The R-TENG assembly flow chart is shown in Figure S2. The R-TENG generates alternating current through rotation, which is converted into direct current through a rectifier to power the subsequent in-situ electrolytic cell. The working principle of R-TENG is shown in Figure S3. The in-situ electrolytic cell consists of an Ag@NF electrode that simultaneously serves as the negative electrode, a catalyst and a SERS substrate, a platinum (Pt) wire electrode that serves as the positive electrode, and an electrolytic container. The actual picture of the in-situ electrolytic cell is shown in Figure S4A. In addition, in the spectral test part, a 785 nm laser is used to excite the Raman signal on the Ag@NF surface, and the Raman spectrum is collected and output by a spectrometer to analyze the chemical information of the surface molecules. The actual picture of the Raman spectrometer is shown in Figure S4B. The degradation and monitoring target molecule are rhodamine 6G (R6G), which is an orange-red powder, and its Raman signal intensity is detected using SERS technology.

Figure 1.

The SERS substrate preparation and in-situ SERS system design

(A) Ag@NF substrate preparation.

(B) In-situ SERS monitoring system for self-powered degradation based on R-TENG.

SERS substrate characterization

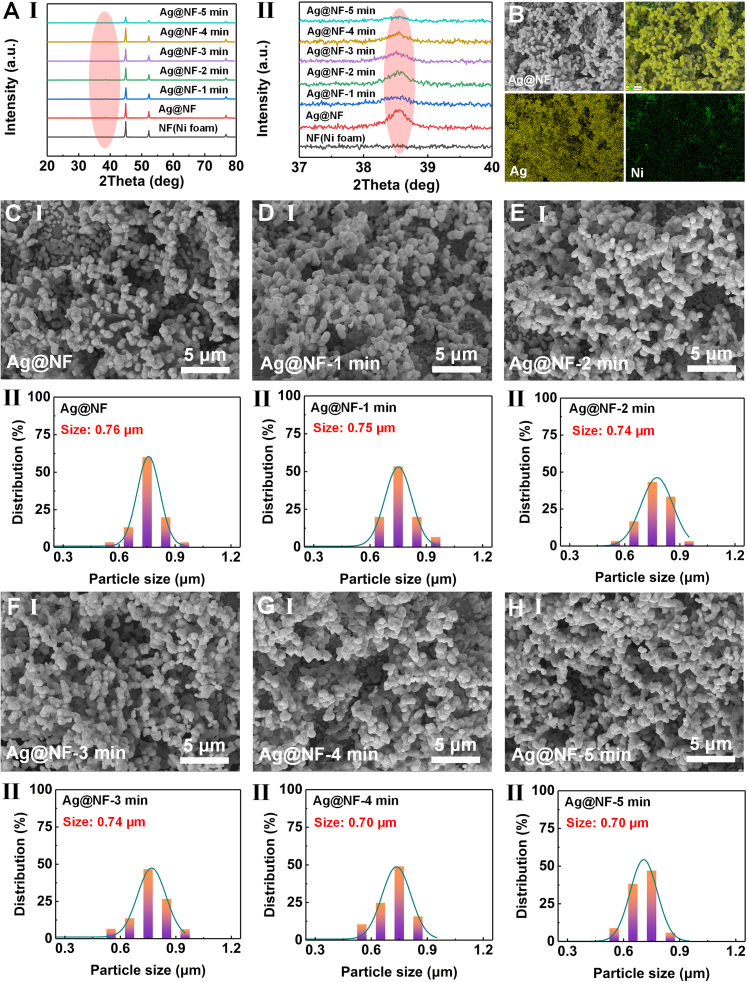

Ag@NF composite material is prepared by in-situ growth of Ag on NF, and characterized by XRD and SEM. As shown in Figure 2A, the XRD spectrum in the angle range (20–80°) reveals the diffraction characteristics of the Ag@NF-X (X = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 min) at different electrolysis times (1–5 min) compared with pure NF. To qualitatively identify the substance attached to NF as Ag, XRD analysis is performed on NF and Ag@NF before and after growth. The XRD diffraction peaks of pure NF appear at 44.6°, 51.9°, and 76.5°, corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes, respectively, indicating that the Ni is a cubic crystal structure (PDF#70–0989). When Ag was composited with NF, only new XRD diffraction peaks at 38.1° and 64.4° are observed, corresponding to the (111) and (220) crystal planes. This is because the diffraction peaks of Ag at 44.3° and 77.4° are close to the diffraction peaks of Ni at 44.6° and 76.5°, which are difficult to distinguish, corresponding to the (200) and (311) crystal planes of Ag, indicating that Ag is a cubic structure (PDF#89-3722). Comparing the diffraction peaks of Ag and Ag@NF, it clearly shows that no other crystal structures are introduced except the crystal phases of Ag and Ni, indicating that the Ag@NF is successfully prepared. In addition, as the electrolysis time increases (1–5 min), the lattice structure of Ag and Ni is not affected under the condition of a DC voltage of 6 V. Ag can enhance the signal of in-situ SERS monitoring of dyes in the catalytic process due to its plasma resonance effect. Its content and distribution state in the Ag@NF electrode material will directly affect the in-situ SERS monitoring signal. To this end, the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) is used to characterize the content and distribution of Ag in the Ag@NF. Figure 2B shows the SEM image of the Ag@NF and its corresponding element distribution. The results show that the Ag element is evenly distributed on the Ag@NF surface, and the NF provides good support as a substrate (Figure S5), further confirming that the Ag particles have been successfully deposited on the NF surface. Among them, Figure S6 is a diagram of the relative content of elements in Ag@NF. The relative content of Ni is 15.88% and the relative content of Ag is 84.12%. NF has a rich porous skeleton structure, and the skeleton surface has a certain degree of roughness, which can provide many attachment sites for the in-situ growth of Ag. Compared with planar electrodes, the three-dimensional porous structure of NF helps to increase the number of active sites of the electrode, thereby significantly improving the electrocatalytic efficiency. The SEM of NF after growing Ag is shown in Figure 2C. It can be seen that a large number of Ag particles are accumulated into a network and attached to the surface of the NF skeleton, and the size of Ag particles is about 0.76 μm. As shown in Figure S7A, it can be seen from the SEM that Ag is relatively uniformly anchored on the surface of Ni foam skeleton in the form of particles, and the size of these particles is relatively uniform. Importantly, given the key role of the distance between Ag particles in optimizing the SERS effect, the average distance between these particles is quantified in HR-SEM and found to be mainly concentrated around 100 nm. This characteristic scale is of great significance for understanding the SERS performance. In addition, to further explore the element distribution characteristics of the Ag@NF, Figures S7B and S7C show the elemental mapping of Ag@NF. The energy spectrum analysis results show that the atomic percentages of Ni and Ag are 78.15% and 18.93%, respectively, while the atomic percentage of O is only 2.92%, which is significantly lower than the former two. This shows that in the Ag@NF, the degree of Ag oxidation is extremely low, thus verifying that the Ag@NF has excellent chemical stability and reliability. As shown in Figures 2D–2H, with the electrolysis times (1–5 min) increases, the microstructure of the Ag@Ni-X (X = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 min) material remains stable and the size of Ag particles has not changed significantly.

Figure 2.

The Ag@NF substrate characterization

(A) XRD of Ag@NF before and after degradation of R6G solution.

(B) EDS of Ag@NF.

(C) SEM of Ag@NF and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(D) SEM of Ag@NF-1 min and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(E) SEM of Ag@NF-2 min and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(F) SEM of Ag@NF-3 min and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(G) SEM of Ag@NF-4 min and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(H) SEM of Ag@NF-5 min and Ag particle size. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Catalytic performance and characterization

Figure 3A shows the three-dimensional curve of the residual concentration ratio of R6G solution over time under different DC voltages (3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 V). The closer the ratio value is to 1, the worse the decolorization effect of the solution. The closer the ratio value is to 0, the more thorough the decolorization of the solution. In the same electrolysis time, compared with other DC voltages, when the DC voltage is 6 V, the residual concentration ratio of R6G solution decreases to nearly 0, and the decolorization effect is the best. Figure 3B describes the degradation efficiency of organic dyes under different DC voltages. The degradation efficiency under the action of DC voltage 3 V is 42.2%, which is the lowest efficiency. The degradation efficiency under the action of DC voltage 6V is 98.8%, and the R6G solution is nearly completely decolorized. As the DC voltage increases, the degradation efficiency of R6G solution gradually decreases. Figure 3C shows that under the action of DC voltage 6 V, the color of R6G solution gradually changes from yellow to almost transparent over time. The UV-visible absorption spectrum in Figure 3D further reveals that the absorption peak intensity of R6G at 450 nm gradually decreases with the extension of time, which is consistent with the decolorization process of R6G solution. Figure 3E intuitively shows the attenuation process of the absorption peak. The strong absorption in the initial stage (0 min) is concentrated near 450 nm. The intensity gradually weakens with the increase of time and almost disappears after 5 min, further verifying the variation law of R6G solution degradation in the spectrum and time.

Figure 3.

The catalytic performance powered by DC power

(A) Three-dimensional curve of the residual concentration ratio of R6G solution over time under different DC voltages.

(B) Catalytic efficiency of Ag@NF under different DC voltages.

(C) Color comparison of R6G solution over time under 6 V DC voltage.

(D) UV-visible absorption spectrum of R6G solution over time under 6 V DC voltage.

(E) Cloud chart of R6G solution over time under 6 V DC voltage.

The in-situ monitoring of the electrocatalytic degradation process of R6G solution based on Raman spectroscopy is shown in Figure 4. Figure 4A shows a schematic diagram of the experimental device, which mainly includes a DC power, a Raman spectrometer, and an in-situ electrolytic cell. The R6G solution was placed in the electrolytic cell and degraded under different DC voltage conditions, while its Raman spectral signal was recorded in real time. Figures 4B–4F shows the change trend of the Raman spectral signal over time (0–6 min) under different DC voltage conditions (3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 V). Several key Raman characteristic peaks (such as 629 cm−1, 789 cm−1, 1202 cm−1, 1327 cm−1, 1379 cm−1, 1523 cm−1, and 1664 cm−1) are marked in the spectrum. The intensities and band assignments in the spectra of R6G shown in Table S1.32,33 These characteristic peaks may be related to the chemical bond vibration modes of the reactants or products. Under different DC voltage conditions, multiple characteristic peaks in the Raman spectral signal of R6G (such as 629 cm−1, 789 cm−1, 1202 cm−1, 1327 cm−1, 1379 cm−1, 1523 cm−1, and 1664 cm−1) gradually changed over time, indicating that during the electrocatalytic degradation of R6G solution, the material underwent transformation or structural changes. In addition, there were significant differences in the degradation degree of R6G under different DC voltage conditions, which further confirmed that Ag not only played the role of negative electrode and catalyst in the electrocatalytic degradation process, but more importantly, it served as a SERS substrate, thereby realizing real-time monitoring of Raman spectroscopy signals. The time-resolved spectral data are collected with a fixed voltage increment of 3 V, as shown in Figure S8. In Figure S8A, within the time range of 0–5 min, the applied voltage is increased by 3 V for every 1 min increase, eventually reaching 15 V. The typical Raman characteristic peaks of R6G (such as 1202, 1327, 1379, 1523, and 1664 cm−1) are selected as the main analysis objects, and the correlations between applied voltage and R6G degradation rates is established. With the gradual increase of the applied voltage, the intensity of each Raman characteristic peak of R6G showed a significant downward trend and the decreasing rates of different peaks are different. Specifically, when the voltage increased from 0 V to 15 V, the main Raman peak intensities at approximately 1202, 1327, 1379, 1523, and 1664 cm−1 decreased by 67%, 56%, 61%, 85%, and 75%, respectively, as shown in Figure S8B. This result shows that among the Raman characteristic peaks, the peak at 1523 cm−1 decreases the fastest, indicating that the molecular bond corresponding to it is more sensitive to the electric field and is prone to breakage. In contrast, the peak at 1327 cm−1 decreases more slowly, indicating that the corresponding chemical bond has stronger stability and is more resistant to electric field-induced degradation. In Figure S9A, the detection range of Ag@NF substrate is from 10−3 to 10−9 M, and its detection limit can reach 10−9 mol/L. Considering that the Ag material itself has a certain tendency to oxidize, the stability of Ag-based SERS substrate is also systematically evaluated. As shown in Figure S9B, the Raman signal changes of the Ag@NF substrate placed in the natural environment for up to 10 days are monitored. The results show that compared with the Raman signal of the initial Ag@NF substrate, its Raman peak intensity did not show a significant decrease after 10 days, and the characteristic peaks of R6G dye can still be clearly identified. The comparison of detection limits of Ag-based and Au-based SERS substrates in detecting R6G is shown in Table S2. In addition, the Raman signal changes of the Ag@NF substrate placed in the natural environment for up to 10 days are monitored. The results show that compared with the Raman signal of the initial Ag@NF substrate, its Raman peak intensity did not show a significant decrease after 10 days, and the characteristic peaks of R6G dye can still be clearly identified. The uniformity of the SERS substrate has an important influence on the accuracy of the analysis results and is one of the key parameters for evaluating its performance. The uniformity of the SERS substrate has an important influence on the accuracy of the analysis results and is one of the key parameters for evaluating its performance. As shown in Figure S10A, the experiment used R6G with a concentration of 10−5 M as the probe molecule, selected an area of 14 × 14 μm2 on the surface of the substrate, and collected at uniform interval with a step size of 1 μm to obtain the SERS spectrum. Subsequently, the SERS signal intensities at characteristic peaks such as 1202, 1327, 1379, 1523, and 1664 cm−1 are selected to make intensity mapping diagrams, as shown in Figures S10B–S10F. As can be seen from the figures, the color distribution of the Raman signal intensity is relatively uniform, indicating that the distribution of the measured molecules on the substrate and the distribution of the SERS “hot spots” are both in good repeatability. Further, the signal intensity of characteristic peaks such as 11202, 1327, 1379, 1523, and 1664 cm−1 are performed. Based on 225 repeated tests, the average signal intensities of each characteristic peak are measured as follows: 11202 cm−1 (1424.91 ± 37.87), 1327 cm−1 (1573.77 ± 116.25), 1379 cm−1 (1362.89 ± 43.44), 1523 cm−1 (1551.11 ± 69.10), and 1664 cm−1 (1819.61 ± 109.61). Meanwhile, the relative standard deviation (RSD) of 11202, 1327, 1379, 1523, and 1664 cm−1 are calculated to be approximately 4.4%, 3.1%, 7.3%, 6.0%, and 2.6%, and all are less than 10%. This result shows that the Ag@NF SERS substrate has excellent repeatability and uniformity. As shown in Figure S11, the R6G solution with concentration of 10−5 M is degraded at 6 V for up to 30 min, and Raman signals are collected every 1 min by in-situ SERS monitoring. SEM observations show that the morphologies of the Ag@NF electrode have no obvious change before and after degradation for 30 min, showing good morphological stability. XRD analysis also shows that the crystalline structure of Ag@NF electrode remains consistent before and after degradation, with no obvious phase change or oxidation product generation, which further verified the stability of the electrode under long-term working conditions. Figure S12 compares the element distribution of the Ag@NF electrode before and after degradation (30 min). Although the O content increased, it is still low relative to Ni and Ag, further proving the structural and chemical stability of the Ag@NF electrode during degradation.

Figure 4.

The SERS of R6G solution powered by DC power

(A) In-situ SERS monitoring system for degradation based on DC power.

(B) Raman spectrum under DC voltage 3 V.

(C) Raman spectrum under DC voltage 6 V.

(D) Raman spectrum under DC voltage 9 V.

(E) Raman spectrum under DC voltage 12 V.

(F) Raman spectrum under DC voltage 15 V.

Figure 5A shows a self-powered degradation and in-situ SERS monitoring system based on R-TENG, which includes an R-TENG, a SERS device, and an in-situ electrolytic cell. The alternating current generated by the R-TENG is converted into direct current through a rectifier to drive the operation of the in-situ electrolytic cell. Ag@NF is used as a catalyst in the electrolytic cell, and R6G is used as a degradation target. During the experiment, the electric energy generated by the R-TENG powers the electrolytic cell through a rectifier to drive the catalytic degradation reaction. At the same time, Ag@NF can also be used as a SERS substrate to monitor the dynamic changes of the reactants on the catalyst surface in real time through Raman spectroscopy. Figure 5B shows the open circuit voltage, short circuit current, and transfer charge performance of the R-TENG at different speeds. When the speed range is 1.8–3.8 r/s, the open-circuit voltage (VOC) is stable at about 100 V, and it fluctuates periodically over time, indicating that the device performance is stable and reliable. The short-circuit current (ISC) remained stable between 1.25 and 2.5 μA, while the transferred charge (QSC) was maintained at about 40 nC, and showed good repeatability at different rotation speeds, further verifying the reliability and stability of the device. Figure 5C shows the changes in the Raman spectrum of R6G during the degradation process (0–55 min). As the degradation time increases, the intensity of multiple characteristic Raman peaks (such as 1664, 1523, 1379, 1327, and 1202 cm−1) decreases significantly. In addition, the high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis is performed on the undegraded and degraded R6G samples. As shown in Figure S13A, only the parent ion peak of m/z = 443 is detected in the undegraded R6G sample. In Figure S13B, multiple ion peaks of degradation products are detected, with m/z values of 415, 359, 284, 272, 258, 148, 132, 122, and 115, respectively. As shown in Figure S14, the chemical structures corresponding to these degradation products are as follows. degradation products of m/z = 415, 359, 284, 272, 258, 148, 132, 122, and 115 were detected. According to relevant literature, the possible degradation products of m/z = 415, 359, 258, 148, 132, 122, and 115 are (Z)-N-(6-amino-9-(2-(ethoxycarbonyl) phenyl)-2,7-dimethyl-3H-xanthen-3-ylidene)-ethanaminium, ethyl 2-(6-amino-2-methyl-3H-xanthen-9-yl) benzoate, 6-amino-9-phenylcyclopenta [b] chromenylium, adipic acid, glutaric acid, benzoic acid, and 8-phenyl-3H-dicyclopenta [b, e] pyran-2,6-diylium, respectively. Figure 5D compares the color changes of the R6G solution in the initial state (0 min) and after 55 min of degradation. In the initial state, the R6G solution appears orange-red. As the degradation progressed, the solution color almost completely faded and became clear at 55 min. This phenomenon clearly shows that the degradation of R6G driven by TENG is feasible. To improve the transparency and repeatability of spectral data, as shown in Figure S15, under the action of the electric field generated by the TENG, 10 different electrode locations on the Ag@NF SERS substrate are randomly selected to carry out in-situ SERS detection of the degradation process of R6G. All the raw spectral data have been provided and attached to the Data S1: The original data of 10 random points. The variation trends of the SERS signals measured at 10 random electrode locations are consistent, indicating that the Ag@NF SERS substrate has good uniformity and stability, thus ensuring the reliability and repeatability of the experimental results. As shown in Figure S16, in the experimental design, pH values of 9 and 5 are set to explore the in-situ SERS characteristics of R6G in the degradation process. Although the Raman peak intensity of R6G decreased under the pH value of 5, its degradation rate was significantly slowed down compared with the degradation trend at pH value of 9. These results clearly show that decolorization rate is higher at basic medium than that obtained under acidic conditions. A few related results can be obtained in the literature where basic conditions are found to be superior for the degradation of pollutant molecules.32,34,35

Figure 5.

The SERS of R6G solution powered by R-TENG

(A) In-situ SERS monitoring system for self-powered degradation based on R-TENG.

(B) Electrical properties of R-TENG.

(C) Raman spectra driven by R-TENG at a rotation speed of 2.2 r/s.

(D) Color comparison of R6G solution before and after degradation.

Discussion

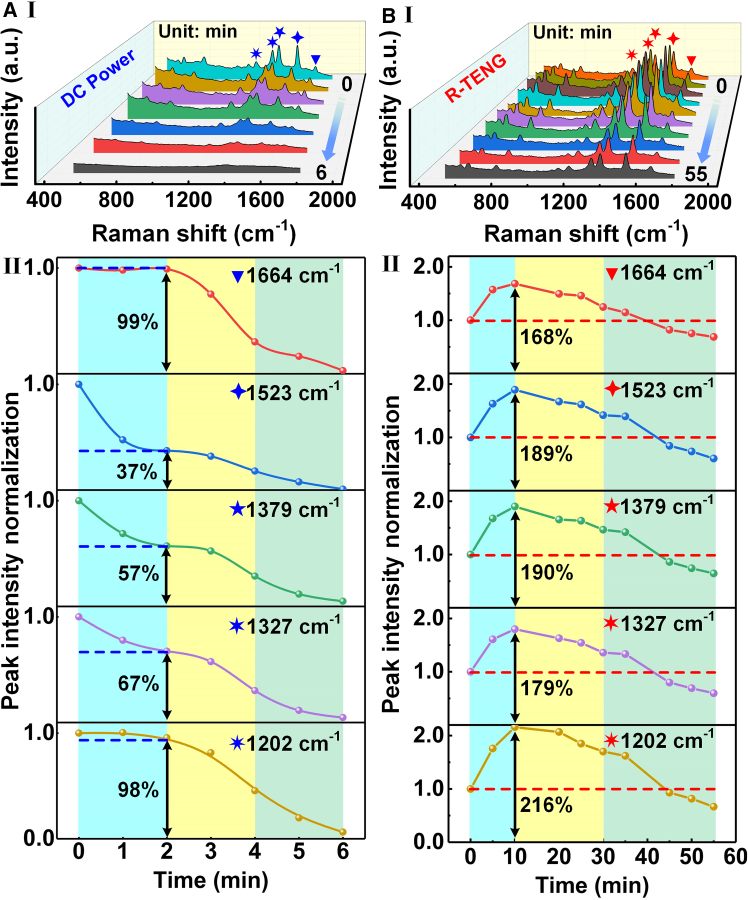

Figure 6 compares the changes in the Raman spectral signal of R6G under DC power and R-TENG conditions and the dynamic changes of its normalized intensity over time. In Figure 6AI, the intensity of the characteristic peaks of the Raman spectrum (1664, 1523, 1379, 1327, and 1202 cm−1) under DC power conditions decays rapidly over time, and the intensity of most peaks decreases significantly within 6 min, or even almost disappears completely. Figure 6AII further shows the time evolution trend of the normalized intensity of the Raman peaks at different wavenumbers. Specifically, when the degradation reaches 2 min, the intensity of the Raman peak at 1664 cm−1 remains almost unchanged, only decreasing to 99% of the original value; while the intensity of the Raman peak at 1523 cm−1 decreases significantly, leaving only 37% of the original intensity. The intensity at 1379 cm−1 decreases to 57% of the original value; the intensities at 1327 cm−1 and 1202 cm−1 decay to 67% and 98% of the original values, respectively. These results show that different characteristic peaks show obvious degradation time sequence during the catalytic degradation of R6G. In contrast, the degradation process under the R-TENG condition presents completely different characteristics. Figure 6BI shows that the normalized intensity of the Raman peak shows a significant enhancement phenomenon at the initial stage of degradation, and then gradually weakens over time. This dynamic change of “first enhancement and then weakening” is in sharp contrast to the single decay mode driven by DC power. It can be further observed from Figure 6BII that the normalized intensity of the Raman characteristic peaks 1664, 1523, 1379, 1327, and 1202 cm−1 initially enhances to 168%, 189%, 190%, 179%, and 216% of the original value, respectively. This unique enhancement phenomenon is attributed to the high voltage and low current characteristics of TENG. At the initial stage of degradation, the electric field causes the enrichment of R6G molecules near the electrode to be higher than its degradation amount, resulting in a significant increase in the Raman signal intensity. As degradation proceeds, the molecular enrichment gradually decreases, and the degradation becomes the dominant process, eventually causing the signal intensity to gradually decrease. In general, the degradation process under R-TENG conditions presents a unique dynamic behavior, and its initial signal enhancement and later intensity decrease are completely different from those under DC power conditions. This phenomenon not only reflects the unique mechanism of action of R-TENG, but also provides a new perspective for understanding the dynamic changes of organic molecules under a specific electric field. To verify the universality of the mechanism that dye molecules can simultaneously achieve enrichment and degradation under the action of the TENG electric field, the experimental objects are further expanded to other types of compounds, such as crystal violet dye and carbendazim drugs, as shown in Figure S17. First, in Figure S17A, the 785 nm Raman laser wavelength is used to perform in-situ SERS detection of crystal violet dye during the action of the TENG electric field. Within the 70 min test time, the Raman characteristic peak intensity of crystal violet dye showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, just like the R6G dye. This result shows that the simultaneous enrichment and degradation mechanism under the TENG electric field is not only applicable to R6G dyes, but also to crystal violet dyes, further verifying the universality of this mechanism. Subsequently, in Figure S17B, the concentration of carbendazim is also set to 10−5 M, and its degradation test is carried out under the same TENG electric field conditions as the R6G dye. Unfortunately, the experimental results show that under the same TENG electric field conditions, carbendazim did not show obvious degradation. Preliminary analysis shows that this phenomenon may be related to the parameters of the applied TENG electric field conditions. This discovery also provides a direction for future research.

Figure 6.

The comparison of Raman spectra powered by DC power/R-TENG

(A) Raman spectra powered by DC power and comparison of normalized intensity of characteristic peaks.

(B) Raman spectra powered by R-TENG and comparison of normalized intensity of characteristic peaks.

Taken together, a simultaneous enrichment and degradation mechanism of organic molecules around the electrode in the triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) electric field is proposed by in-situ SERS. The in-situ SERS monitoring system for self-powered degradation includes TENG, SERS device, and in-situ electrolytic cell. Among them, the Ag@NF prepared by in-situ growth method simultaneously acts as the electrode of the in-situ electrolytic cell to achieve the degradation of organic molecules, and serve as SERS substrate to not only achieve molecular trace detection with concentration as low as 10−5 mol/L, but also analyze the degradation timing characteristics of different characteristic peaks of organic molecules. In-situ SERS reveals that under the influence of the TENG electric field, the SERS intensity of characteristic peaks in the organic molecules exhibits a dynamic trend of “initial enhancement followed by attenuation.” In the early degradation stages, the enrichment quantity of organic molecules around the electrode exceeds the degradation quantity. As the reaction progresses, the enrichment gradually decreases, and degradation becomes dominant, leading to SERS intensity reduction. This phenomenon differs significantly from the molecular migration in the DC electric field, that is, the organic molecules undergo direct degradation without enrichment behavior in DC electric field. This work reveals the unique migration mechanism of organic molecules in the TENG electric field and provides theoretical support for self-powered degradation applications.

Limitations of the study

Although this study is groundbreaking in using in-situ SERS technology to detect the enrichment and degradation mechanism of organic molecules driven by TENG, it also acknowledges several limitations. The long-term durability of TENG in different environmental conditions and the consistency of its performance still need to be further explored and verified.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Sheng Zhang (zhangsheng20@mails.ucas.ac.cn).

Materials availability

Materials used in the study are commercially available.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

No new code was generated during the course of this study.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52406212, 52372251) and start-up grant from the Anhui University of Science and Technology (grant no. 2023yjrc100).

Author contributions

S.Z. and Z.Z. conceived the idea. S.Z. designed the experiments and performed data measurements. Z.Z. and Z.S. analyzed the data. J.M. and C. Xue helped with the experiments. S.Z. drafted the article. Y.Z. and C.X. supervised this work. All authors discussed the results and commented on the article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Rhodamine 6G | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | R105624; CAS: 989-38-8 |

| Crystal violet | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | C110703; CAS: 548-62-9 |

| Carbendazim | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | C140191; CAS: 10605-21-7 |

| AgNO3 | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | S765726 CAS: 7783-99-5 |

| Ni faom | Wuzhou Sanhe New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangxi, China) | https://www.hgptech.com/ |

| Pt wire | Guiyan (Beijing) Platinum Technology Development Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) | https://cnplatinum.gys.cn/ |

| PTFE film | Taizhou Yongchen New Materials Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China) | https://shop0751809627925.1688.com/?spm=a261b.12309193.0.0.255d62e7FJvvaP |

| Cu film | Suzhou Aifeimin Shielding Conductive Materials Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China) | http://www.yft88.com/fjdtbjd.shtml |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Origin 2022 | OriginLab | https://www.originlab.com/ |

| Pro/Engineer wildfire 5.0 | Pro/E | http://creo.xmsouh.cn/ |

| KeyShot 10 | KeyShot | https://keyshot.mairuan.com/ |

| 3D Printer | JG maker | http://www.cyd86.com/index.html |

Experimental model and subject details

This study does not use experimental methods typical in the life sciences.

Method details

Materials

Rhodamine 6G was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Crystal violet was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carbendazim was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). AgNO3 was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ni faom was purchased from Jinchang Yuheng Nickel Network Co., Ltd. (Gansu, China). Pt wire was purchased from Guiyan (Beijing) Platinum Technology Development Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). PTFE film was purchased from Taizhou Yongchen New Materials Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Cu film was purchased from Anhui Tongguan Copper Foil Group Co., Ltd. (Anhui China). All materials were used as is, without purification.

Synthesis of Ag@NF composite material

Ag/Ni foam (Ag@NF) composite material is prepared by in-situ growth method. The Ni foam (NF) is cut into 10 mm × 10 mm in size and ultrasonically cleaned with 3 mol/L hydrochloric acid, deionized water and anhydrous ethanol for 15 min each to remove surface oxides and contaminants. Subsequently, under stirring conditions, 3 wt % ammonia water is added dropwise to 10 mL of 40 mmol/L silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution until the solution returned from turbidity to clarity. Then, 50 mmol/L of glucose is added and stirred until the solution turned brown, indicating that the growth solution is prepared. The pretreated NF is placed horizontally in the prepared growth solution and reacted in a water bath at 60 °C for 40 min. After the reaction, the NF is taken out of the solution, rinsed with deionized water several times, and dried under vacuum conditions to finally obtain the Ag@NF composite material.

Fabrication of electrocatalytic degradation device

The in-situ electrolytic cell is designed as a cubic structure with grooves of 15 mm × 15 mm×10 mm and then fabricated by 3D printing technology. The prepared Ag@NF composite material is welded to the copper wire and placed horizontally at the bottom of the electrolytic cell as the negative electrode. Subsequently, a platinum (Pt) wire with a diameter of 0.5 mm is used as the electrocatalytic positive electrode material. The Pt wire is also connected by copper wire. Finally, the above positive and negative electrode materials are connected to the external power through copper wires to form a complete electrocatalytic degradation device.

In situ SERS monitoring system

A DC power or R-TENG is used to provide power, the rhodamine 6G (R6G) is used as an organic dye pollutant probe, and a Raman spectrometer is used to detect R6G in real time during the electrocatalytic degradation process. The Pt and Ag@NF composite material are connected to the positive and negative electrodes of the power through copper wires, respectively, and 0.5 mL of R6G solution with a concentration of 10−5 mol/L is added to the in-situ electrolytic cell. Then, the connected electrocatalytic device was placed under the Raman spectrometer laser, and the laser focus is adjusted to be on the Ag@NF electrode. The laser length used for Raman detection is 785 nm, the power is 30 mW, the number of integrations is 1 time, and the integration time is 5 s. Finally, the power is turned on for electrocatalytic degradation, and the Raman spectrum of R6G is obtained in real time during the degradation process.

Sample characterizations

XRD is used to characterize the sample phase. SEM is used to characterize the sample morphology. The sample is measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy in the range of 300∼800 nm. The SERS spectra is obtained using a Raman spectrometer: spectrometer (Omini-λ5008i), 785 nm laser (Laser 785-5HS, China), CCD detector (iVac316, Andor, UK) and UNI-T DC power (UTP3313TFL). A data acquisition and analysis software platform are created using LabVIEW software and a data acquisition card (USB-6009, National Instruments, USA). An electrometer (6514, Keithley, USA) is employed to measure parameters such as open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current, and transferred charge, etc.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The sample phase data were characterized with an XRD. The sample morphology data were characterized with a SEM. The UV-Vis data were characterized with a UV-Vis spectroscopy. The SRES data were collected with a Raman spectrometer. The TENG data were collected with a Keithley 6514 electrometer. Figures were produced by Origin from the raw data.

Additional resources

This study has not generated or contributed to a new website/forum.

Published: July 29, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113236.

Contributor Information

Sheng Zhang, Email: zhangsheng20@mails.ucas.ac.cn.

Cheng Xu, Email: xucheng@cumt.edu.cn.

Yabo Zhu, Email: zhuyabo@163.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Chen S., Gao C., Tang W., Zhu H., Han Y., Jiang Q., Li T., Cao X., Wang Z. Self-powered cleaning of air pollution by wind driven triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy. 2015;14:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y., Zhang H., Lee S., Kim D., Hwang W., Wang Z.L. Hybrid energy cell for degradation of methyl orange by self-powered electrocatalytic oxidation. Nano Lett. 2013;13:803–808. doi: 10.1021/nl3046188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shang Y., Xu X., Gao B., Wang S., Duan X. Single-atom catalysis in advanced oxidation processes for environmental remediation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:5281–5322. doi: 10.1039/D0CS01032D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z., Si Y., Yu C., Jiang L., Dong Z. Bioinspired superwetting oil–water separation strategy: toward the era of openness. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024;53:10012–10043. doi: 10.1039/D4CS00673A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S., Baltussen M.G., Ivanov N.M., Haije R., Jakštaitė M., Zhou T., Huck W.T.S. Exploring emergent properties in enzymatic reaction networks: design and control of dynamic functional systems. Chem. Rev. 2024;124:2553–2582. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang B., Zhao M., Cheng K., Wu J., Kubuki S., Zhang L., Yong Y.C. Piezoelectric effect coupled advanced oxidation processes for environmental catalysis application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025;523 doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu M., Li J., Chen M., Liu Y., Mei Q., Liu H., Tang Y., Wang Q. The electron shuttle of aloe-emodin promotes the Cu-FeOOH solid solution photocatalytic membrane to activate hydrogen peroxide for the degradation of tannic in traditional Chinese medicine wastewater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy. 2025;361 doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X., Tu P., Wang X., Du C., Jiang W., Qiu X., Wang J., Chen L., Chen Y., Ren J. Decomposable nanoagonists enable nir-elicited cgas-sting activation for tandem-amplified photodynamic-metalloimmunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2024;36 doi: 10.1002/adma.202313029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh M., Guo H., Lin L., Wen Z., Li Z., Hu C., Wang Z.L. Rolling friction enhanced free-standing triboelectric nanogenerators and their applications in self-powered electrochemical recovery systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.103944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xuan N., Song C., Cheng G., Du Z. Advanced triboelectric nanogenerator based self-powered electrochemical system. Chem. Eng. J. 2024;481 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.148640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basith S.A., Khandelwal G., Mulvihill D.M., Chandrasekhar A. Upcycling of waste materials for the development of triboelectric nanogenerators and self-powered applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024;34 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.148640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan F.-R., Tian Z.-Q., Lin Wang Z. Flexible triboelectric generator! Nano Energy. 2012;1:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z.L. On Maxwell’s displacement current for energy and sensors: the origin of nanogenerators. Mater. Today. 2017;20:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z.L., Wang A.C. On the origin of contact-electrification. Mater. Today. 2019;30:34–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2019.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S., Jing Z., Wang X., Fan K., Zhao H., Wang Z.L., Cheng T. Enhancing low-velocity water flow energy harvesting of triboelectric−electromagnetic generator via biomimetic-fin strategy and swing-rotation mechanism. ACS Energy Lett. 2022;7:4282–4289. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c01908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y., Mo J., Fu Q., Lu Y., Zhang N., Wang S., Nie S. Enhancement of triboelectric charge density by chemical functionalization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30 doi: 10.1002/adfm.202004714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei A., Xie X., Wen Z., Zheng H., Lan H., Shao H., Sun X., Zhong J., Lee S.T. Triboelectric nanogenerator driven self-powered photoelectrochemical water splitting based on hematite photoanodes. ACS Nano. 2018;12:8625–8632. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b04363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong F., Pang Z., Yang S., Lin Q., Song S., Li C., Ma X., Nie S. Improving wastewater treatment by triboelectric-photo/electric coupling effect. ACS Nano. 2022;16:3449–3475. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S., Zhang B., Zhao D., Gao Q., Wang Z.L., Cheng T. Nondestructive dimension sorting by soft robotic grippers integrated with triboelectric Sensor. ACS Nano. 2022;16:3008–3016. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S., Zhang B., Gu G., Xiang X., Zhang W., Shi X., Zhao K., Zhu Y., Guo J., Cui P., et al. Triboelectric plasma decomposition of CO2 at room temperature driven by mechanical energy. Nano Energy. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X., Cao L.N.Y., Zhang T., Fang R., Ren Y., Chen X., Bian Z., Li H. Optimizing photocatalytic performance in an electrostatic-photocatalytic air purification system through integration of triboelectric nanogenerator and Tesla valve. Nano Energy. 2024;128 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.109965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W., Shang Y., Han K., Shi X., Jiang T., Mai W., Luo J., Wang Z.L. Self-powered agricultural product preservation and wireless monitoring based on dual-functional triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024;16:20642–20651. doi: 10.1021/acsami.4c02869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L., Liu L., Qiao W., Gao Y., Zhao Z., Liu D., Bian Z., Wang J., Wang Z.L. Improving degradation efficiency of organic pollutants through a self-powered alternating current electrocoagulation system. ACS Nano. 2021;15:19684–19691. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c06988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian M., Zhang D., Wang M., Zhu Y., Chen C., Chen Y., Jiang T., Gao S. Engineering flexible 3D printed triboelectric nanogenerator to self-power electro-Fenton degradation of pollutants. Nano Energy. 2020;74 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen S., Fu J., Yi J., Ma L., Sheng F., Li C., Wang T., Ning C., Wang H., Dong K., Wang Z.L. High-efficiency wastewater purification system based on coupled photoelectric–catalytic action provided by triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021;13:194. doi: 10.1007/s40820-021-00695-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao S., Su J., Wei X., Wang M., Tian M., Jiang T., Wang Z.L. Self-powered electrochemical oxidation of 4-Aminoazobenzene driven by a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano. 2017;11:770–778. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J., Wen Z., Zi Y., Lin L., Wu C., Guo H., Xi Y., Xu Y., Wang Z.L. Self-powered electrochemical synthesis of polypyrrole from the pulsed output of a triboelectric nanogenerator as a sustainable energy system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:3542–3548. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201600021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han K., Luo J., Feng Y., Xu L., Tang W., Wang Z.L. Self-powered electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis directly from air as driven by dual triboelectric nanogenerators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:2450–2458. doi: 10.1039/D0EE01102A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S., Wang N., Ma L., Li T., Willander M., Jie Y., Cao X., Wang Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator for sustainable wastewater treatment via a self-powered electrochemical process. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016;6 doi: 10.1002/aenm.201501778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C., Tang W., Han C., Fan F., Wang Z.L. Theoretical comparison, equivalent transformation, and conjunction operations of electromagnetic induction generator and triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting mechanical energy. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:3580–3591. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology and self-powered sensors–principles, problems and perspectives. Faraday Discuss. 2014;176:447–458. doi: 10.1039/C4FD00159A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajoriya S., Bargole S., Saharan V.K. Degradation of a cationic dye (Rhodamine 6G) using hydrodynamic cavitation coupled with other oxidative agents: Reaction mechanism and pathway. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rasheed T., Bilal M., Iqbal H.M.N., Hu H., Zhang X. Reaction mechanism and degradation pathway of rhodamine 6G by photocatalytic treatment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017;228:291. doi: 10.1007/s11270-017-3458-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao J.J., Gao N.Y., Li C., Li L., Xu B. Mechanism and kinetics of parathion degradation under ultrasonic irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;175:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehrdad A., Hashemzadeh R. Ultrasonic degradation of Rhodamine B in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and some metal oxide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

No new code was generated during the course of this study.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.