Abstract

BACKGROUND

Stroke is relatively uncommon in children, with a risk of recurrence ranging from 5% to 19%. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical for optimal recovery, but stroke in children is often identified later than in adults. While mechanical thrombectomy is a well-established standard treatment for acute ischemic strokes in adults, emerging data continue to show that this intervention can also benefit pediatric patients.

OBSERVATIONS

This case report discusses the management of a 13-year-old male with recurrent basilar artery occlusions and an associated vertebral artery dissection. Initially presenting with acute ischemic stroke symptoms, the patient underwent a successful thrombectomy with significant improvement in neurological function. He experienced a second stroke due to another basilar artery occlusion, which was subsequently treated by a thrombectomy. Further investigation revealed a vertebral artery dissection with a pseudoaneurysm, likely contributing to the stroke recurrence. Treatment adjustments included transitioning from aspirin to clopidogrel when aspirin resistance concern was noted, and finally apixaban therapy when the dissection was discovered. The patient remained stable without stroke recurrence.

LESSONS

This case exemplifies the effectiveness of mechanical thrombectomy in pediatric stroke management and warrants further consideration for repeat procedures for recurrence due to insidious vertebral arterial dissections and those with aspirin resistance.

Keywords: mechanical thrombectomy, recurrent stroke, aspirin resistance, pediatrics, vertebral artery dissection, case report

ABBREVIATIONS: AIS = acute ischemic stroke, CTA = CT angiography, DADA2 = deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2, ED = emergency department, mRS = modified Rankin Scale, NIHSS = National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, TICI = thrombolysis in cerebral infarction

The incidence of stroke in the pediatric population is about 2–13 per 100,000 each year for hemorrhagic stroke and 2–3 per 100,000 for ischemic stroke, which is considerably lower than that in the adult population.1 Up to 25% of cases are reported during the perinatal period, and the highest published incidence age, excluding perinatal cases, averages around 2.3 years.2 In pediatric stroke patients, the 5-year recurrence risk is between 5% and 19%, with the highest risk in patients with arteriopathy or cardiac disease.3,4 The most common pediatric risk factors for stroke include congenital heart disease, prothrombotic and metabolic disorders, elevated lipoprotein, and infection.5Similar to the adult population, immediate diagnosis of an acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is crucial in the initial stages of presentation to reduce the chances of permanent or debilitating effects. Due to the difference in clinical presentation and incidence rate, however, the diagnosis of stroke in children is delayed compared with that in adults.6

After the initial diagnosis, intravenous/intra-arterial thrombolysis and/or mechanical/endovascular thrombectomy is the standard treatment for adult patients experiencing an AIS.7 Basilar artery occlusions in particular have been shown to correlate with poorer outcomes in adults. Numerous randomized clinical trials have reported extensive evidence, proving the efficacy of thrombectomy procedures for adults with large-vessel occlusions.8 There are, however, limited but growing data regarding the efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy in the pediatric population, particularly involving the posterior circulation. Of the current cases and data available for interpretation, thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis have been shown to improve recovery and outcomes in the pediatric population, as measured by an improvement in modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores postoperatively.9 New data continue to show the efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy use in the pediatric population for AIS, but there are limited incidences and therefore limited data to observe the efficacy of repeat thrombectomy procedures in those with recurrent strokes.

Illustrative Case

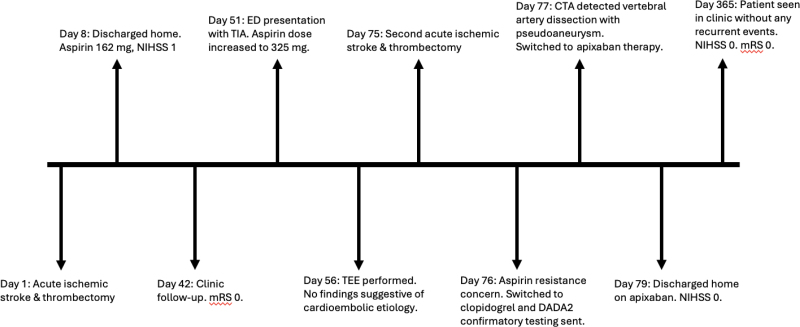

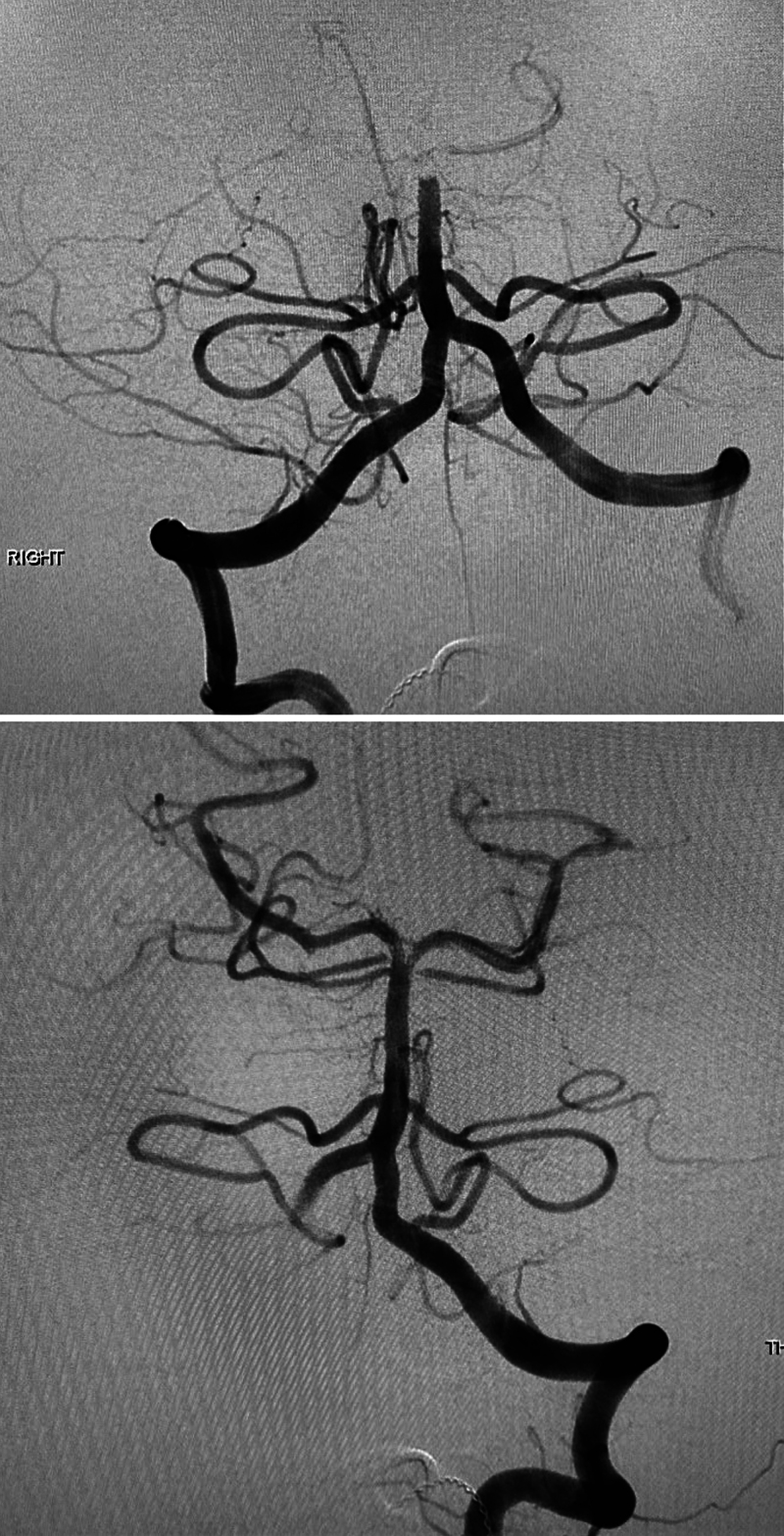

The sequence of events in this case is summarized in Fig. 1. This case involved a 13-year-old male who presented to the emergency department (ED) and reported double vision, right-sided numbness, dysarthria, and dizziness. The patient and his father denied any family history of stroke or any previous episodes of stroke-like symptoms. His NIHSS score at that time was 2. Complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, CT of the head, chest radiography, and echocardiography showed no significant abnormalities. MRI showed bilateral remote thalamic infarcts. MR angiography confirmed by cerebral angiography showed a basilar artery occlusion (Fig. 2 upper). The patient’s thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score was 3, suggesting complete recanalization (Fig. 2 lower). The patient’s NIHSS score postthrombectomy was 1. The patient was discharged on a regimen of aspirin 162 mg. The patient’s mRS score at 1 month was 1 due to residual right hemisensory loss with no associated disability.

FIG. 1.

Outlined summary of pertinent case events. TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

FIG. 2.

Upper: Prethrombectomy. Lower: Postthrombectomy.

The patient returned to the ED 2 months later due to an episode of right-sided weakness and slurred speech that lasted for 1 minute. Due to the patient’s history and recurrent symptoms, the neurology team was consulted, and findings from a workup including brain imaging and blood work were found to be unremarkable. Transesophageal echocardiography did not show any intracardiac shunting or possible cardioembolic etiologies. The patient’s aspirin dosage was increased to 324 mg daily.

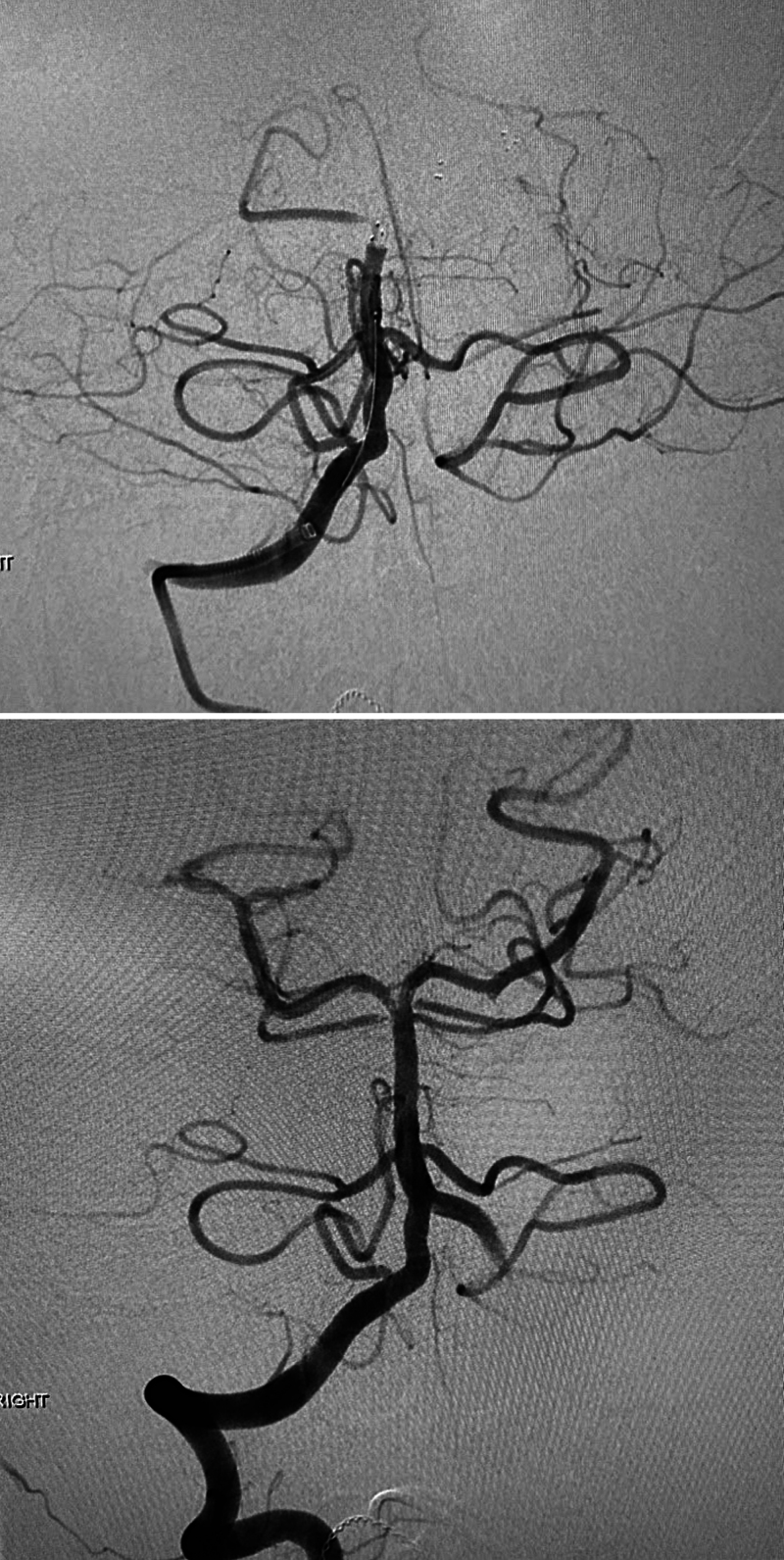

Two and a half months after the first stroke incident, the patient presented to the ED again, complaining of dizziness, right-sided sensory loss, right facial droop, and dysarthria. His NIHSS score wase 3. It is important to note that his baseline NIHSS score was 1 at the most recent neurology visit. CT angiography (CTA) showed evidence of a recurrent distal basilar occlusion. Thrombectomy was performed with a TICI score of 3 (Fig. 3 upper). The patient underwent a thrombectomy procedure, and follow-up CTA showed successful removal of the basilar artery thrombus (Fig. 3 lower). Postoperative MRI of the brain did not show evidence of cerebral infarction or hemorrhages but did show evidence of old lacunar infarctions. Aspirin platelet function testing was performed during this hospitalization, and the results showed the possibility of aspirin resistance. Deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2) blood work was sent for confirmatory testing, and the patient was placed on clopidogrel. Subsequent clopidogrel platelet function level showed appropriate platelet response.

FIG. 3.

Upper:Prethrombectomy. Lower: Postthrombectomy.

Two days after the thrombectomy, repeat CTA was performed due to concerns of asymmetric pupils. This study confirmed a patent basilar artery with no arterial occlusion or stenosis visualized. It also revealed an elusive small vertebral artery dissection with an associated pseudoaneurysm in the V3 segment of the vertebral artery (Fig. 4 left). This was thought to be the possible source of the embolus causing recurrent basilar occlusions. Clopidogrel was discontinued, and the patient was started on apixaban. The patient appeared to be at a neurological baseline with no neurological deficits at the follow-up appointment (mRS score 0) a few weeks later. It was also revealed at this appointment that the patient would frequently self-perform neck adjustments to crack the cervical vertebrae and was subsequently advised to avoid future adjustments. No other neck injury was reported. Follow-up CTA 1 year after the initiation of anticoagulation therapy showed a stable dissection and pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 4 right). The patient has remained symptom free without stroke recurrence since apixaban initiation.

FIG. 4.

CT angiograms. Left: Vertebral artery dissection (open arrow indicates the point of vertebral artery dissection leading to pseudoaneurysm). Right: Vertebral artery dissection 1 year after anticoagulation.

A literature review of pediatric cases involving vertebrobasilar thrombectomy procedures revealed 31 prior cases with outcomes listed in Table 1.,10–32 Patient age ranged from 17 months to 16 years. Of the 31 cases, 23 had complete recanalization as indicated by a TICI score of 3. At follow-ups ranging from 30 to 90 days postthrombectomy, 16 of the 31 cases reported an mRS of score 0. Only 5 cases reported the additional use of tPA. Vertebral artery dissection was identified as the etiology for 7 cases with no reports of associated pseudoaneurysms. None of these cases involved recurrent thrombectomy.

TABLE 1.

Summary of case reports for mechanical thrombectomy in vertebrobasilar occlusions of pediatrics

| Authors & Year | Case No. | Age | Occlusion Site | Pre-MT NIHSS | Post-MT NIHSS | Reduction in NIHSS Score | Final TICI Score | Final mRS Score | Likely Etiology | Received tPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derrico et al., 202410 | 1 | 2 yrs | VB | NR | NR | — | 2b | 1 | Cardioembolic | No |

| Teivāne et al., 202311 | 1 | 9 yrs | VB | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | Cryptogenic | No |

| Ali et al., 202112 | 1 | 7 yrs | VB | 21 | 1 | 20 | 3 | NR | VA thrombosis | No |

| Soutome et al., 202113 | 1 | 12 yrs | VB | 7 | NR | NR | 3 | 0 | Cardioembolic | No |

| Shoirah et al., 201914 | 8 | 13 yrs | VB | 17 | 0 | 17 | 3 | 0 | VA dissection | No |

| 13 | 5 yrs | VB | 4 | NA | — | 3 | 1 | VA dissection | No | |

| 14 | 17 mos | VB | NA | — | — | 2b | 1 | NR | No | |

| 15 | 22 mos | VB | NA | — | — | 3 | 0 | Cardioembolic | No | |

| Zhou et al., 201915 | 1 | 11 yrs | VB | 20 | 6 | 14 | 3 | 2 | Cryptogenic | No |

| 6 | 8 yrs | VB | 22 | 8 | 14 | 3 | 2 | Cryptogenic | Yes | |

| Bhogal et al., 201816 | 4 | 7 yrs | VB | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | Cardioembolic | No |

| Bigi et al., 201817 | 14 | 14 yrs | VB | 21 | NR | — | 2b | 0 | Cardioembolic | No |

| Wilkinson et al., 201818 | 1 | 17 mos | VB | NA | NA | — | 2b | 0 | VA thrombosis | No |

| Nicosia et al., 201719 | 1 | 23 mos | VB | NR | NR | 3 | 1 | VA dissection | No | |

| Madaelil et al., 201620 | 1 | 16 yrs | VB | 9 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 0 | Cryptogenic | No |

| Savastano et al., 201621 | 1 | 22 mos | VB | NA | NA | — | 3 | 0 | Cardioembolic | No |

| Huded et al., 201522 | 1 | 6 yrs | VB | 15 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 0 | Lt VA dissection | No |

| Ladner et al., 201523 | 1 | 5 yrs | VB | 22 | 1 | 21 | 2b | 0 | Lt VA dissection | No |

| Bodey et al., 201424 | 1 | 10 yrs | VB | 27 | NR | — | 3 | 3 | VA dissection | No |

| 2 | 5 yrs | VB | 29 | NR | — | 3 | 2 | Dehydration | No | |

| 3 | 6 yrs | VB | 28 | NR | — | 2b | 0 | VA dissection | No | |

| Dubedout et al., 201325 | 1 | 7 yrs | VB | 20 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0 | Cryptogenic | No |

| Fink et al., 201326 | 1 | 11 yrs | VB | 6 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 1 | Cryptogenic | Yes |

| Tatum et al., 201327 | 1 | NR | VB | 17 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 3 | Lt atrial thrombus | Yes |

| 3 | NR | VB | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Cardioembolic | No | |

| 4 | 4 yrs | VB | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Arterial thrombus from VA trauma | No | |

| Taneja et al., 201128 | 1 | 14 yrs | VB | NR | NR | — | 3 | 0 | Cryptogenic | No |

| Grunwald et al., 201029 | 1 | 16 yrs | VB | 36 | 3 | 33 | 3 | NR | Cryptogenic | No |

| Grigoriadis et al., 200730 | 1 | 6 yrs | VB | NR | NR | — | 2b* | 1 | VA dissection | Yes |

| Kirton et al., 200331 | 1 | 15 yrs | VB | NR | NR | — | 3* | 1 | Cryptogenic | Yes |

| Cognard et al., 200032 | 1 | 8 yrs | VB | NR | NR | — | NR | 0 | VA dissection | No |

NA = not applicable; NR = not recorded; VA = vertebral artery; VB = vertebrobasilar.

* Calculated from case report.

Informed Consent

The necessary informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

This case intertwines the topics of recurrent basilar artery occlusions, traumatic vertebral artery dissections as a source of embolism, aspirin resistance, and thrombectomy procedures in the pediatric population. Our literature review of pediatric cases involving vertebrobasilar thrombectomy showed successful total recanalization and improvement in neurological status as measured by NIHSS and mRS scores for more than half of the cases mentioned. Similarly, a recent retrospective analysis of a cohort of children who received mechanical thrombectomy after acute ischemic strokes showed not only good angiographic outcomes but also significant neurological improvements.33

The success of two mechanical thrombectomies performed in this case warrants further consideration of the success of mechanical thrombectomy and thrombolysis in the pediatric population as a whole. Although the pediatric population is unique in that these patients do not meet any inclusion criteria for clinical trials, thrombolysis and thrombectomy success in retrospective studies and case reports should contribute to its proof of efficacy when considering the use of thrombectomy as a first-line treatment in pediatric strokes from basilar occlusion.

As stated in the report, the patient did admit to frequently self-performed neck manipulations that involved twisting and cracking his neck, leading to possible injury to the vertebral artery. Although the incidence is low, systematic reviews have noted that repeated or traumatic neck manipulations are underreported at the time of clinical presentation of an AIS due to carotid artery dissections.34 Previous studies have further investigated the connection between vertebral artery dissections and neck manipulations as well. A literature review in adolescent vertebral artery dissection found that 49% of the 90 reported cases were caused by chiropractic or sports-related neck manipulation.35 Additional studies have found that the manifestations of subtraumatic vertebral artery dissections can be insidious and delayed but result in major complications such as recurrent transient ischemic attacks or basilar artery occlusions and posterior circulation strokes.36

This report also exhibited another rarity that warrants further study: aspirin resistance and its role in the incidence of stroke. DADA2 is one mechanism that can be used to confirm the presence of resistance.37 This deficiency usually manifests as a range of vasculopathy from vasculitis to stroke.37 This is because DADA2 is a highly polymorphic gene causing many different pathologies or resulting in a silent carrier status.38 Although the literature is minimal, one may also consider the prevalence of DADA2 in the causation of pediatric strokes and the importance of this screening as a method of preventing the possibility of exacerbation or recurrence of pediatric vasculopathy such as in this patient’s stroke. Lastly, this is one of the few cases we have found that displays two successful thrombectomy procedures after stroke recurrence in the pediatric population, further exhibiting the benefits of mechanical thrombectomy as a first-line treatment.

Lessons

In conclusion, this case report provides unique insight into arterial dissections and aspirin resistance for stroke causation in the pediatric population. It displays the benefits as mechanical thrombectomy that can be further considered in the improvement of pediatric stroke outcomes and avoidance of recurrence.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Sen, Meyer. Acquisition of data: Sen, Meyer. Analysis and interpretation of data: Sen, Meyer, Wood. Drafting the article: Sen, Meyer. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Sen, Meyer, Wood. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Sen. Statistical analysis: Sen. Administrative/technical/material support: Sen. Study supervision: Sen.

Correspondence

Souvik Sen: School of Medicine, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. souvik.sen@uscmed.sc.edu.

References

- 1.Rivkin MJ Bernard TJ Dowling MM Amlie-Lefond C.. Guidelines for urgent management of stroke in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;56:8-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVeber GA, Kirton A, Booth FA.Epidemiology and outcomes of arterial ischemic stroke in children: the Canadian pediatric ischemic stroke registry. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;69:58-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beslow LA Jordan LC.. Pediatric stroke: the importance of cerebral arteriopathy and vascular malformations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(10):1263-1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodan L, McCrindle BW, Manlhiot C.Stroke recurrence in children with congenital heart disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(1):103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simma B Martin G Müller T Huemer M.. Risk factors for pediatric stroke: consequences for therapy and quality of life. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37(2):121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klučka J, Klabusayová E, Musilová T.Pediatric patient with ischemic stroke: initial approach and early management. Children. 2021;8(8):649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia K, Kortman H, Blair C.Mechanical thrombectomy in pediatric stroke: systematic review, individual patient data meta-analysis, and case series. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;24(5):558-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bilgin C, Ibrahim M, Ghozy S.Disability-free outcomes after mechanical thrombectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024:15910199231224826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chikkannaiah M Lo WD.. Childhood basilar artery occlusion: a report of 5 cases and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(5):633-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derrico NP Kimball R Weaver K Strickland A.. Mechanical thrombectomy in pediatric large vessel occlusions before cerebrovascular maturity: a case report and technical note. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e59027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teivāne A, Naļivaiko I, Jurjāns K.Successful mechanical thrombectomy for basilar artery occlusion in a pediatric patient: a case report. Biomedicines. 2023;11(10):2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali N Al-Chalabi M Salahuddin H.. Successful mechanical thrombectomy for basilar artery occlusion in a seven-year-old male. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soutome Y, Hirotsune N, Kegoya Y.A child with paradoxical cerebral embolism in whom mechanical thrombectomy led to a favorable outcome. J Neuroendovasc Ther. 2021;15(2):100-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoirah H, Shallwani H, Siddiqui AH.Endovascular thrombectomy in pediatric patients with large vessel occlusion. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2019;11(7):729-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou B, Wang XC, Xiang JY.Mechanical thrombectomy using a Solitaire stent retriever in the treatment of pediatric acute ischemic stroke. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;23(3):363-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhogal P, Hellstern V, AlMatter M.Mechanical thrombectomy in children and adolescents: report of five cases and literature review. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2018;3(4):245-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bigi S, Dulcey A, Gralla J.Feasibility, safety, and outcome of recanalization treatment in childhood stroke. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(6):1125-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson DA, Pandey AS, Garton HJ.Republished: Late recanalization of basilar artery occlusion in a previously healthy 17-month-old child. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2018;10(7):e17-e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicosia G, Cicala D, Mirone G.Childhood acute basilar artery thrombosis successfully treated with mechanical thrombectomy using stent retrievers: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33(2):349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madaelil TP Kansagra AP Cross DT Moran CJ Derdeyn CP.. Mechanical thrombectomy in pediatric acute ischemic stroke: clinical outcomes and literature review. Interv Neuroradiol. 2016;22(4):426-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savastano L Gemmete JJ Pandey AS Roark C Chaudhary N.. Republished: Acute ischemic stroke in a child due to basilar artery occlusion treated successfully with a stent retriever. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2016;8(8):e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huded V, Kamath V, Chauhan B.Mechanical thrombectomy using solitaire in a 6-year-old child. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2015;8(2):13-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladner TR He L Jordan LC Cooper C Froehler MT Mocco J.. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke in childhood: how much does restricted diffusion matter? J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2015;7(12):e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodey C, Goddard T, Patankar T.Experience of mechanical thrombectomy for paediatric arterial ischaemic stroke. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(6):730-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubedout S Cognard C Cances C Albucher JF Cheuret E.. Successful clinical treatment of child stroke using mechanical embolectomy. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49(5):379-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink J Sonnenborg L Larsen LL Born AP Holtmannspötter M Kondziella D.. Basilar artery thrombosis in a child treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular mechanical thrombectomy. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(11):1521-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatum J, Farid H, Cooke D.Mechanical embolectomy for treatment of large vessel acute ischemic stroke in children. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2013;5(2):128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taneja SR Hanna I Holdgate A Wenderoth J Cordato DJ.. Basilar artery occlusion in a 14-year old female successfully treated with acute intravascular intervention: case report and review of the literature. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47(7):408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grunwald IQ, Walter S, Shamdeen MG.New mechanical recanalization devices—the future in pediatric stroke treatment? J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22(2):63-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grigoriadis S Gomori JM Grigoriadis N Cohen JE.. Clinically successful late recanalization of basilar artery occlusion in childhood: what are the odds? J Neurol Sci. 2007;260(1-2):256-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirton A, Wong JH, Mah J.Successful endovascular therapy for acute basilar thrombosis in an adolescent. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):e248-e251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cognard C Weill A Lindgren S Piotin M Castaings L Moret J.. Basilar artery occlusion in a child: “clot angioplasty” followed by thrombolysis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16(8):496-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sporns PB, Kemmling A, Hanning U.Thrombectomy in childhood stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(5):e011335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wynd S Westaway M Vohra S Kawchuk G.. The quality of reports on cervical arterial dissection following cervical spinal manipulation. PLOS One. 2013;8(3):e59170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saeed AB Shuaib A Emery D Al-Sulaiti G.. Vertebral artery dissection: warning symptoms, clinical features and prognosis in 26 patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(4):292-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta R Siroya HL Bhat DI Shukla DP Pruthi N Devi BI.. Vertebral artery dissection in acute cervical spine trauma. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2022;13(1):27-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erdem S Akay E Akbas T Demir F Ozbarlas N.. Aspirin resistance in children with congenital heart disease and its relationship with laboratory and clinical parameters. Iran J Pediatr. 2021;31(2):e109797. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyts I Aksentijevich I.. Deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2): updates on the phenotype, genetics, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(5):569-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]