Abstract

Background:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with antiangiogenic therapy have become the standard of care for advanced HCC, albeit with limited therapeutic benefit. Our previous studies demonstrated the immunomodulatory and antitumor effects of polyIC, a synthetic dsRNA. Here, we compared the efficacy of anti-programmed death ligand 1 (αPD-L1) plus polyIC versus αPD-L1 plus anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (αVEGF) in mouse tumor models.

Methods:

We established a primary liver tumor model using hydrodynamic tail vein injection of Ras/Myc oncogenes and a metastasized tumor model via intrasplenic injection of colon cancer cells. Flow cytometry and gene expression analysis were performed to assess immune profiles across treatment groups. Key factors contributing to antitumor efficacy were explored.

Results:

In both models, αPD-L1 plus polyIC demonstrated superior antitumor effects relative to αPD-L1 plus αVEGF. Unlike αVEGF, polyIC enhanced the immune response to αPD-L1 by increasing T cell infiltration, T effector memory CD8+ T cells, CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio, and CD8+ T cell function. This combination also promoted apoptosis in tumors and the accumulation of conventional dendritic cells and invariant natural killer T cells. In addition, αPD-L1 plus polyIC treatment led to upregulation of cytokines and chemokines, with CCL5 blockade partially reducing the CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio and attenuating polyIC-driven antitumor effects.

Conclusions:

This preclinical study identifies polyIC as an efficacious adjuvant of αPD-L1 treatment in liver cancer, providing a better strategy to improve immunotherapy outcomes.

Keywords: anti-PD-L1, anti-VEGF, HCC, immunomodulation, polyIC

INTRODUCTION

The standard of care for systemic therapy in advanced HCC has evolved significantly in recent years. Sorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, was first approved as a first-line therapy in 2007,1,2 followed by the approval of other similar agents, including lenvatinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab.3,4,5,6 More recently, targeting immune evasion with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has revolutionized the treatment of many solid tumors, including HCC. Anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated efficacy in patients with advanced HCC previously treated with sorafenib.7,8

Combination therapy has since emerged as a key focus of HCC clinical research. The phase III IMbrave150 trial demonstrated that atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) plus bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) as first-line therapy for advanced HCC resulted in superior objective response rates and survival outcomes compared to sorafenib, establishing it as the new standard of care since 2020.9 In addition, a non-VEGF/VEGFR-targeting approach was explored in the phase III HIMALAYA trial, where dual ICIs, durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) plus tremelimumab (anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4, CTLA-4), also showed superior efficacy over sorafenib, leading to its approval in 2022.10 Another dual ICI combination, nivolumab (anti-PD-1) plus ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), improved objective response rates and overall survival in the phase III CheckMate 9DW trial, though careful management of immune-related adverse events is required.11 Despite these advancements, further strategies to enhance treatment efficacy by targeting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) in HCC remain under investigation.

Our previous preclinical studies demonstrated that polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyIC), a synthetic dsRNA that stimulates interferon and cytokine production, induces PD-L1 expression in the TME. Combining polyIC with anti-PD-L1 suppressed liver cancer that was refractory to anti-PD-L1 alone.12 Furthermore, in a metastatic cancer model, polyIC enhanced the antitumor response to anti-PD-L1 in the liver.13 As a Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ligand, polyIC activates antigen-presenting cells and natural killer (NK) cells while promoting CD8+ T cell priming and proliferation.14

In this study, we compared the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 plus polyIC versus anti-PD-L1 plus anti-VEGF in primary and metastasized liver cancer models. We demonstrated that anti-PD-L1 plus polyIC exhibited superior antitumor effects relative to anti-PD-L1 plus anti-VEGF. Mechanistically, polyIC enhanced the immune response to anti-PD-L1 by promoting T cell infiltration, increasing T effector memory CD8+ T cells, improving the CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio, and boosting CD8+ T cell function. Treatment with anti-PD-L1 and polyIC also led to upregulation of cytokines and chemokines, while CCL5 blockade partially reduced the CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio and diminished polyIC-driven antitumor effects. These findings provide a novel design for improving immunotherapy outcomes in HCC.

METHODS

Animals, cells, and tumor models

Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. The animal protocols (S09108) were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), following National Institutes of Health guidelines. Seven-week-old mice underwent a 1-week acclimation period before experiments. MC38 colon cancer cells were maintained in our lab and cultured in antibiotic-free DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Primary liver cancer models were induced via hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVi) of oncogenes along with the Sleeping Beauty transposase, as previously described.15 The plasmids (PT/Caggs-N-Ras-V12, PT3-EF1a-C-Myc) were generously provided by Dr X. Chen (University of Hawaii). Metastasized liver cancer models were established by injecting 1×105 MC38 cells directly into the mouse spleen under 3% isoflurane anesthesia.13

Drug administration

αPD-L1 (BE0101; Bioxcell) was administered via i.p. injection at 200 μg every other day, starting on day 14 for 6 doses in the primary liver cancer model, and on day 7 for 4 doses in the metastasized tumor model. PolyIC (GE Healthcare) was i.p. injected at 4 mg/kg every other day, administered the day after αPD-L1. The treatment strategy is based on the protocol established in our previous studies.12,13 Similarly, αVEGF-A (2G11A; BioLegend) was given at 5 mg/kg every other day on the day following αPD-L1. αCCL5 (W20042A; BioLegend) was i.p. injected at 10 mg/kg every 3 days for 6 doses at the indicated time points in the primary liver cancer models.

Histopathology

Liver tissue was fixed in Z-Fix solution or embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek) for paraffin and frozen block preparation, respectively. Tissue slides were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains. H&E slides were scanned by a Nanozoomer 2.0-HT slide scanner and screened by NDP view 2.7.25 (Hamamatsu Photonics).

Cell preparation and flow cytometry

Liver tissue was enzymatically digested with collagenase H (Roche # 11087789001) via in situ perfusion. The digested tissue was then filtered through a 100 μm strainer and subjected to gradient centrifugation to isolate immune cells. Cells were first stained with the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (L34957; Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by staining with an antibody cocktail. Intracellular staining was performed using the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (00-5523; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 Cell Analyzer at the UCSD Human Embryonic Stem Cell Core facility, Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.6.2; Becton, Dickinson & Company). A complete list of flow cytometry antibodies is provided in Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57.

RNA sequencing and bioinformatic data analysis

Immune cells were isolated from liver tissues, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (74034; Qiagen). RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the Illumina TruSeq v2 Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on the NovaSeq 6000 platform at the UCSD Genomics Core. Raw sequencing reads were first subjected to quality control and adapter trimming using Trim Galore (v0.6.7) to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences. High-quality cleaned reads were then aligned to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) with default parameters. The resulting alignments were processed to quantify gene expression levels using 2 different approaches. Gene-level raw counts were obtained using HTSeq-count (v0.13.5) with the “union” mode for feature assignment, whereas Cufflinks (v2.2.1) was used to calculate FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) values for transcript-level quantification. Differentially expressed genes were identified based on q values and fold changes using DESeq2 (v3.20). Volcano plots were generated using the EnhancedVolcano (v1.11.3) package in R.

Immune gene expression in a public dataset

Gene expression data from patients with HCC were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to assess CCL5 expression levels in tumor versus normal liver tissues, evaluate its prognostic significance, and investigate its correlation with immune cell markers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Data are presented as means±SEM. Differences between the 2 groups were assessed using the Student t test, while comparisons among 3 or more groups were conducted using 1-way ANOVA. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared with the log-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01).

RESULTS

αPD-L1 plus polyIC more effectively suppresses primary liver cancer growth than αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A

In previous studies, we demonstrated that oncogene-induced primary liver cancer responds poorly to αPD-L1 monotherapy. However, combining αPD-L1 with polyIC led to significant tumor suppression and improved survival in mice.12 Given that αPD-L1 plus αVEGF is the standard of care for advanced HCC, we compare the antitumor efficacy and immune modulation effects of αPD-L1 plus polyIC (αPD-L1+polyIC) versus αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A (αPD-L1+αVEGF-A) in primary liver cancer models.

By transfecting Ras/Myc oncogenes via HTVi, we induced primary liver cancers. Tumor-bearing mice received αPD-L1+polyIC or αPD-L1+αVEGF-A every other day for 6 doses and were sacrificed at 6 weeks (Figure 1A). Mice treated with αPD-L1+polyIC exhibited lower tumor burdens than those that received αPD-L1+αVEGF-A (Figure 1B). Tumor burdens, assessed by the number and size of tumor nodules and liver-to-body (L/B) weight ratio, indicated consistently more robust tumor suppression by αPD-L1+polyIC than αPD-L1+αVEGF-A, although both combinations were similarly effective (Figures 1D–F). However, survival was significantly prolonged in mice treated with αPD-L1+polyIC, as compared to the control and αPD-L1+αVEGF-A groups (Figure 1C). Together, these data suggest that αPD-L1 plus polyIC more effectively suppresses oncogene-induced primary liver cancer than αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A, with significant survival benefit.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of αPD-L1 plus polyIC and αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A in primary liver tumors. (A) The experimental scheme of combination therapy in the HCC mouse model induced by Ras/Myc via HTVi. αPD-L1 was i.p. injected every other day for 6 doses since day 14. PolyIC or αVEGF-A was i.p. injected every other day for 6 doses since day 15. (B) Representative macroscopic views and H&E staining of liver sections at week 6. Scale bar: 100 µm. (C) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival of the 3 groups with indicated treatment (Ctrl: n=8, αPD-L1+polyIC: n=7, αPD-L1+αVEGF-A: n=10). Tumor burdens were evaluated by (D) numbers of tumor nodules, (E) maximal volume of nodules, and (F) liver weight to body weight (LW/BW) ratios (Ctrl: n=7, αPD-L1+polyIC: n=6, αPD-L1+αVEGF-A: n=6). Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; Ctrl, control; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HTVi, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; LW/BW, liver weight to body weight; polyIC, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid.

αPD-L1 plus polyIC more effectively suppresses metastasized liver tumors than αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A

While immunotherapy has shown promise in metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) with mismatch repair deficiency or high microsatellite instability, the majority of CRCs are mismatch repair proficient or microsatellite stable and remain resistant to ICIs. Notably, αVEGF is a common treatment modality for metastatic CRC. We compared the efficacy of αPD-L1+polyIC versus αPD-L1+αVEGF-A in a liver metastasis model.

MC38 CRC cells were inoculated via intrasplenic injection, and tumor-bearing mice were treated with either αPD-L1+polyIC or αPD-L1+αVEGF-A, starting on day 7 post-injection and continuing every other day for 4 doses. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 (Figure 2A). Consistent with the results observed in primary liver cancer, αPD-L1+polyIC significantly suppressed tumor formation in both the liver and spleen compared to αPD-L1+αVEGF-A (Figure 2B). In the polyIC combination group, only 2 out of 11 mice (18%) developed liver tumor nodules, whereas 7 out of 9 in the αVEGF-A combination group and all 8 mice (100%) in the control group developed tumors. Similarly, spleen tumor burden was notably reduced in the polyIC combination group (Figure 2D). Tumor burden, evaluated by liver weight, spleen-to-body weight ratio, and the number and size of tumor nodules in the liver, showed that αPD-L1+polyIC provided modestly enhanced tumor suppression, relative to αPD-L1+αVEGF-A (Figures 2E–H). Notably, αPD-L1+polyIC significantly prolonged survival, compared to both the control and αPD-L1+αVEGF-A groups (Figure 2C). In aggregate, the combination of αPD-L1 with polyIC demonstrated superior antitumor efficacy in both primary and metastasized liver tumors.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of αPD-L1 plus polyIC and αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A in metastasized liver tumors. (A) The experimental scheme of combination therapy in metastasized liver tumors driven by splenic injection of MC38 CRC cells. αPD-L1 was i.p. injected every other day for 4 doses since day 7. PolyIC or αVEGF-A was i.p. injected every other day for 4 doses since day 8. (B) Representative macroscopic views and H&E staining of liver sections in each group on day 21. Scale bar: 100 µm. (C) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival of the 3 groups with indicated treatment (Ctrl: n=11, αPD-L1+polyIC: n=10, αPD-L1+αVEGF-A: n=12). (D) Liver tumor formation rates of each group (p<0.05; chi-square test). Tumor burdens were evaluated by (E) liver weight, (F) spleen weight to body weight (S/B) ratios, (G) numbers of tumor nodules, and (H) maximal volume of nodules (Ctrl: n=8, αPD-L1+polyIC: n=10, αPD-L1+αVEGF-A: n=9). Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; CRC, colorectal cancer; Ctrl, control; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; polyIC, polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid.

PolyIC enhances the immune response of αPD-L1 by boosting CD8+ T cell activity in liver cancer models

Given the robust antitumor effects observed with the αPD-L1 plus polyIC treatment, we investigated the immune cell compositions in the liver across various groups in primary liver cancer models, focusing on the dynamic changes during treatment. Notably, the αPD-L1+polyIC treatment induced a higher percentage of T cells among total CD45+ cells compared to the αPD-L1+αVEGF-A groups at both early and late time points (Figures 3A, B). Consistently, immunofluorescent staining of liver tissues demonstrated enhanced infiltration of CD3+ T cells upon treatment with αPD-L1+polyIC (Supplemental Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). Effector memory CD8+ T cells were particularly enriched in the liver treated by αPD-L1+polyIC, while no significant enrichment was observed in the spleen or blood (Figures 3C, D). In addition, the αPD-L1+polyIC treatment, unlike the αPD-L1+αVEGF-A, significantly increased the CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio relative to control groups at later time points (Figure 3E). The proportion of granzyme B+CD8+ T cells and IFNγ+CD8+ T cells also rose within the αPD-L1+polyIC groups, with a greater increase noted at the later time point, suggesting persistent activation of CD8+ T cells (Figures 3G, H). Furthermore, PD-1+CD8+ T cells were enriched in the αPD-L1+polyIC groups compared to both the control and αPD-L1+αVEGF-A groups (Figure 3I). Of note, a unique T cell subset, invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT), which can contribute to antitumor immunity by directly killing tumor cells, enhancing dendritic cell (DC) function, and promoting cytotoxic T cell responses, was significantly upregulated in the αPD-L1+polyIC groups in the primary liver tumor model (Figure 3F). The T cell boosting effect by adding polyIC to αPD-L1 was consistently observed in the MC38 metastasized liver tumor model (Supplemental Figures S2A–D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57).

FIGURE 3.

PolyIC promotes the immune response of αPD-L1 in the liver by boosting cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in the HCC mouse model. (A) Percentages of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells in CD45+ cells after the first dose of treatment at week 2 (n=3). (B) Percentages of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells in CD45+ cells at week 6 (n=3). (C) Percentages of indicated cell subsets in CD8+ T cells, including effector memory (Tem, CD62L−CD44+), central memory (Tcm, CD62L+CD44+), and naïve T cells (CD62L+CD44−) in the liver. (D) Percentages of indicated cell subsets in CD8+ T cells, including Tem, Tcm, and naïve T cells isolated from liver, spleen, and blood (n=3). (E) CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratios at week 6. (F) Percentages of iNKT cells in CD45+ cells are isolated from the liver. (G) Percentages of Granzyme B+ cells in CD8+ T cells. (H) Percentages of IFNγ+ cells in CD8+ T cells after cocktail activation for 4 hours. (I) Percentages of PD-1+ cells in CD8+ T cells. Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; Ctrl, control; iNKT, invariant natural killer T cells; polyIC, polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid; Tcm, central memory T cell; Tem, effector memory T cell.

Regarding the myeloid cell compartments, the proportions of macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils in the liver did not significantly differ between the αPD-L1 plus polyIC and control groups (Figures 4A–C). However, Kupffer cells were notably reduced in the αPD-L1+polyIC group compared to both the αPD-L1+αVEGF-A and control groups (Figure 4D). The percentage of conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) was higher in the αPD-L1+polyIC group, suggesting an enhancement of antigen-presenting function (Figure 4E). Consistent with this, the cell apoptosis activity, assessed by increased cleaved caspase-3 levels, was elevated in liver tumors treated with αPD-L1+polyIC (Figures 4F, G). In addition, we observed an increase in HIF-1α expression in the tumors of the αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A group, which may partially explain the limited antitumor response to this regimen (Figure 4F).16,17 Overall, αPD-L1 plus polyIC enhanced the immune response by increasing CD8+ T cell proportion and function while potentially improving antigen presentation.

FIGURE 4.

Profiles of myeloid cells in the primary liver cancer model. Percentages of (A) macrophage (CD11b+F4/80+), (B) monocyte (CD11b+LY6C+), (C) neutrophil (CD11b+LY6G+), (D) Kupffer cell (CD11b+Clec4f+), and (E) conventional dendritic cells (cDCs, CD11b+MHC II+CD11c+) in the myeloid cells of the liver. (F) Western blot and quantification results displaying the expression levels of HIF-1α and cleaved caspase-3 in liver tumor tissues. (G) Immunohistochemical staining of cleaved caspase-3 in liver tumor tissues of 3 treatment groups. Scale bar: 100 µm. Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; Ctrl, control.

αPD-L1 combined with polyIC induces changes in cytokine and chemokine profiles in the liver

To investigate the mechanism underlying the increase of CD8+ T cells by the αPD-L1+polyIC treatment, we compared tumor samples from the control and αPD-L1+polyIC groups. Using flow cytometry, we isolated C45+ cells, CD8+ T cells, CD3+CD8− T cells, and CD45+CD3− cells (Supplemental Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57), followed by RNA sequencing to examine gene expression in these cell subtypes. Analysis of total CD45+ cells revealed 22,078 differentially expressed genes between the 2 groups (Figure 5A). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment of upregulated genes identified 4 major pathways: measles, apoptosis, T cell signaling, and the p53 signaling pathway (Figure 5B). Focusing on CD8+ T cells, we identified 16,801 differentially expressed genes (Figure 5C), with a heatmap illustrating distinct gene expression patterns associated with αPD-L1+polyIC treatment (Figure 5D). Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analyses showed that T cell differentiation and cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions were among the most significantly enriched pathways in the αPD-L1+polyIC group (Figures 5E, F). We next examined cytokine and chemokine expression changes between the treatment and control groups. αPD-L1+polyIC treatment upregulated CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, IL10, CXCL9, and IFNγ, with CCL5 showing the most pronounced increase in the CD45+CD3− cell population (Figure 5G and Supplemental Figure S4A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57) and the CD45+CD3+CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Figure S4G, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). Analysis of CD3+CD8− T cells showed no significant differences in gene expression between groups (Supplemental Figure S4B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). However, in CD45+CD3− cells, primarily B cells and myeloid cells, we identified 18,516 differentially expressed genes (Supplemental Figures S4C, D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). GO analyses highlighted enrichment in immune response activation and regulation, as well as innate immune response pathways (Supplemental Figure S4E, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). To explore which immune cell populations contribute to CCL5 production, we performed flow cytometry of CCL5 expression in major immune subsets within the liver. CCL5 expression was elevated in both CD3+ T cells and CD19+ B cells, but not in CD11b+ myeloid cells, in the polyIC-based combination treatment group (Supplemental Figure S5, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). These results suggest that changes in chemokine expression in the TME may contribute to increased CD8+ T cell infiltration.

FIGURE 5.

Cytokine and chemokine changes induced by αPD-L1 plus polyIC. (A) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed genes. Upregulated (right) and downregulated (left) genes of total non-parenchymal cells in the liver of αPD-L1 plus polyIC groups compared to the control. (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment of the most significantly upregulated genes of CD45+ cells in αPD-L1 plus polyIC groups compared to control. (C) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed genes. Upregulated (right) and downregulated (left) genes of CD8+ T cells in the liver of αPD-L1 plus polyIC groups compared to the control. (D) Heatmap displaying differentially expressed genes of CD8+ T cells in αPD-L1 plus polyIC groups compared to control. C: Control, T: αPD-L1+polyIC. (E) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showing upregulated genes in CD8+ T cells of the αPD-L1 plus polyIC group. (F) KEGG pathway enrichment of the upregulated genes in CD8+ T cells. (G) Comparison of chemokine and cytokine expression in CD45+CD3− immune cells of αPD-L1 plus polyIC group and control. Abbreviations: C, Control; T, αPD-L1+polyIC.

Blockade of CCL5 impairs the antitumor effect and the expansion of CD8+ T cells induced by αPD-L1 plus polyIC

Since the αPD-L1+polyIC treatment drives CD8+ T cell infiltration and alterations in chemokine expression, we further investigated their relationship within the TME. Serum levels of CCL5 were significantly elevated in mice with primary liver cancer treated with αPD-L1+polyIC compared to the control and αPD-L1+αVEGF-A groups (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure S4F, http://links.lww.com/HC9/C57). This data was consistent with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of gene expression in CD45+ cells from the liver of different models (Figure 6B). To assess a putative role of CCL5, we injected a neutralizing antibody against CCL5 (αCCL5) in combination with αPD-L1+polyIC in the primary liver cancer model (Figure 6C). αCCL5 was administered every 3 days for 6 doses. Notably, CCL5 blockade partially abolished the antitumor effect of the combination treatment (Figures 6D, E).

FIGURE 6.

CCL5 blockade partially diminishes the antitumor effect and CD8+ T cell expansion by αPD-L1 plus polyIC treatment. (A) CCL5 levels in serum were measured by ELISA. (B) Cytokine/chemokine expression in CD45+ cells in the liver was assessed by qRT-PCR. (C) The experimental scheme of combination therapy in the Ras/Myc-induced HCC mouse model. αCCL5 was added to the αPD-L1 plus polyIC regimen and was i.p. injected every 3 days for 6 doses since day 14. Control and αPD-L1 plus polyIC groups were conducted as previously mentioned for comparison. (D) Representative macroscopic views of livers at week 6. (E) Tumor burdens were evaluated by the number of tumor nodules. (F) Percentage of CD3+ T cells in CD45+ cells. (G) Ratios of CD8+ to CD4+ T cells. (H) Percentage of granzyme B+ cells in CD8+ T cells. (I) Percentage of IFNγ+ cells in CD8+ T cells after cocktail activation for 4 hours. Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; Ctrl, control; HTVi, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; polyIC, polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

We then examined the immune cell composition in the livers of different groups. αCCL5 treatment not only reduced the overall percentage of CD3+ T cells but also mitigated the elevated CD8+ to CD4+ T cell ratio induced by αPD-L1 plus polyIC (Figures 6F, G). The functional capacity of CD8+ T cells, assessed by Granzyme B and IFNγ expression, showed a downward trend with αCCL5 treatment (Figures 6H, I). Together, these results suggest that CCL5 plays a role in enhancing CD8+ T cell recruitment and the antitumor effect of αPD-L1+polyIC in the liver.

Analysis of CCL5 expression in human HCC samples

We analyzed gene expression profiles from 373 HCC patient samples in the TCGA dataset. CCL5 expression levels were comparable between HCC and normal liver tissues (Figure 7A). Notably, higher CCL5 expression was associated with a trend toward improved overall survival and significantly longer progression-free survival compared to lower expression levels (Figures 7B, C). In addition, CCL5 expression positively correlated with CD8A expression (Figure 7D). These data support the role of CCL5 in antitumor immunity in the liver.

FIGURE 7.

Gene expression analysis of HCC patient data from the TCGA dataset. (A) Similar CCL5 expression in HCC tissues and normal liver tissues. (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival in HCC patients with high or low CCL5 expression. (C) Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival in HCC patients with high or low CCL5 expression. (D) A positive correlation between CCL5 expression and CD8A expression in HCC tissues. Abbreviation: TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

DISCUSSION

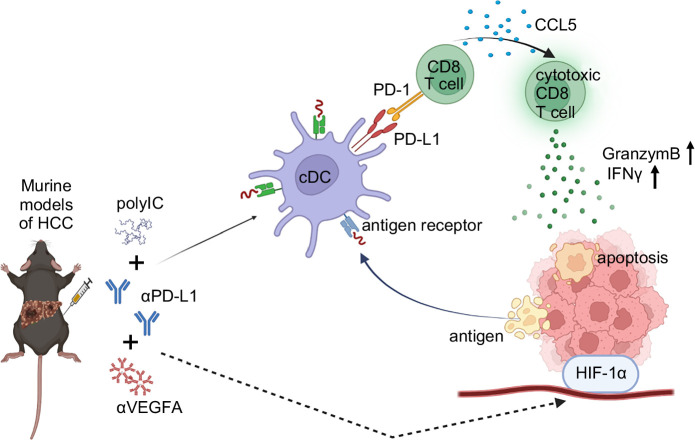

In this study, we performed a comparative analysis of the therapeutic effects of αPD-L1 combined with polyIC or αVEGF-A. Evidently, the combination of αPD-L1 and polyIC exhibited a superior antitumor effect in both primary and metastasized liver cancer models, especially in the survival benefit. This combination enhanced CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the TME and activated their function, and also led to elevated cytokine and chemokine levels, particularly CCL5, in both serum and the TME. Notably, the CCL5 blockade diminished CD8+ T-cell recruitment and reduced the tumor-suppressive effect of αPD-L1+polyIC (Figure 8). These data highlight a novel therapeutic strategy and support the development of combinational immunotherapies for advanced HCC.

FIGURE 8.

A model for the immunomodulation and antitumor mechanisms of αPD-L1 plus polyIC in the liver. Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; polyIC, polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid.

Combining PD-L1 blockade and polyIC effectively suppressed primary liver tumor development by enhancing key immune cell populations, including granzyme B+ and IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells, iNKT cells, cDCs, and PD-1+ CD8+ T cells. This combination therapy promotes both innate and adaptive immunity, with iNKT cells bridging the 2 by producing IFNγ and enhancing DC activation for efficient antigen presentation.18 The increase in granzyme B+ and IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells highlights a strong antitumor response, while the rise in PD-1+ CD8+ T cells suggests active engagement with tumor antigens, overcoming adaptive immune resistance. In addition, the therapy significantly upregulates CCL5 in myeloid and B cells, crucial for recruiting cytotoxic T cells. Blocking CCL5 reduces CD8+ T cell infiltration and weakens the antitumor effect, underscoring its significance. By boosting DC activation, iNKT expansion, and CD8+ T cell responses, this combination therapy presents a promising strategy for enhancing liver cancer immunotherapy.

A recent study has shown that polyIC administration increases CCL5 expression in NK cells and upregulates its receptors, CCR1 and CCR5, in cerebellar microglia of neonatal rat models.19 The induction of CCL5 by polyIC involves downstream signaling molecules such as interferon regulatory factor 3 and Janus kinase 1 (JAK1). A JAK1/2 inhibitor effectively reduced polyIC-induced CCL5 production in bronchial epithelial cells.20 However, the mechanism by which polyIC induces CCL5 expression in the TME of HCC remains unclear. In our study, CCL5 expression correlated with CD8A expression and was associated with better prognosis in HCC patients based on TCGA data. Future research should focus on modulating CCL5 in preclinical models to clarify its functional role in HCC cells and its broader impact on the TME.

The standard of care for advanced HCC patients has primarily focused on antiangiogenic therapy with anti-VEGF/VEGFR agents. While these drugs can reduce or normalize tumor vasculature and exhibit antitumor effects, their associated toxicities, such as bleeding, delayed wound healing, hypertension, and proteinuria, limit their use in some patients.21 Our findings revealed high inter-individual variability in tumor response to αPD-L1 plus αVEGF-A treatment, with suboptimal immune activation compared to the polyIC combination group. Notably, tumors that failed to respond to anti-VEGF-A treatment exhibited extensive necrosis and hemorrhage, suggesting vascular instability. Further analysis showed that HIF-1α expression was elevated in tumors from the αPD-L1+αVEGF-A non-responder group, indicating a potential link between hypoxic adaptation and therapeutic resistance (Figure 4F). However, we did not further investigate the relationship between hypoxia-related factors and tumor angiogenesis, nor can we conclusively determine whether HIF-1α overexpression directly inhibits CD8+ T-cell infiltration and immune efficacy. Future studies are needed to elucidate the mechanistic link between hypoxia, immune suppression, and resistance to VEGF-A blockade, which may provide insights for optimizing combination immunotherapies.

Non-VEGF/VEGFR-based regimens, including dual immunotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 plus anti-CTLA-4, offer alternatives but come with a higher risk of immune-related adverse events.22 PolyIC engages pattern recognition receptors, including TLR3 and the RIG-I/melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) pathway. It exerts multiple immunomodulatory effects, such as promoting T-cell infiltration, inducing macrophage polarization, and activating DCs and NK cells.23,24,25 These properties have led to its application as an adjuvant in cancer vaccines. Our team has demonstrated the antitumor effects of polyIC in combination with ICIs in both primary and metastatic liver cancer models.12,13 Other studies have explored polyIC in combination with various immunotherapies.26,27 Clinically, polyIC combined with ICIs is being evaluated in patients with advanced HCC (NCT03732547). In addition, polyIC derivatives such as Hiltonol and BO-112, a nanoplexed formulation of polyIC, are undergoing clinical trials for solid tumors, including HCC (NCT05281926, NCT02828098). While awaiting the results of these pilot studies, potential toxicities, including neurotoxicity, as well as hepatic and pulmonary toxicities, warrant careful consideration.28,29 To mitigate systemic side effects, some clinical trials utilize intratumoral injection of polyIC or its derivatives. Alternative strategies, such as targeted delivery systems, should be explored to enhance efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity.

This study has some limitations. First, while CCL5 blockade partially attenuated the antitumor effects of αPD-L1 plus polyIC, additional mechanisms need to be explored to fully understand polyIC’s impact on the TME. For example, we observed a significant expansion of iNKT cells within the TME in the αPD-L1 plus polyIC group. Further characterization of their recruitment, activation, and potential tumoricidal activity is required to deepen our mechanistic understanding. Second, we did not employ single-cell sequencing or spatial transcriptomics to dissect the TME and analyze cell–cell interactions in control and treatment groups. Future studies leveraging these advanced technologies will provide deeper insights and facilitate the development of novel strategies to overcome the immunosuppressive TME in HCC.

In conclusion, this study validated that polyIC enhances the efficacy of αPD-L1 in liver cancer models. CD8+ T cells and CCL5 play key roles in mediating the antitumor effects. Future studies are warranted to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms and to develop novel strategies for HCC immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the UCSD School of Medicine Microscopy Core (P30NS047101) and Tissue Technology Shared Resource (NIH P30CA23100). We are grateful to all members of the Feng laboratory for helpful discussion and technical support throughout the project.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: αPD-L1, anti-programmed death ligand 1; αVEGF-A, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor A; cDC, conventional dendritic cell; CRC, colorectal cancer; DC, dendritic cell; FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads; GO, Gene Ontology; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HTVi, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFNγ, interferon gamma; iNKT, invariant natural killer T cells; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; L/B, liver-to-body; MDA5, melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; NK, natural killer; polyIC, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; Tcm, central memory T cell; Tem, effector memory T cell; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TLR3, Toll-like receptor 3; TME, tumor microenvironment; UCSD, University of California, San Diego.

Yichun Ji and Li-Chun Lu share the co-first authorship.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Yichun Ji, Email: yij026@health.ucsd.edu.

Li-Chun Lu, Email: lichun0519@gmail.com.

Hao Zhuang, Email: zhh8764@163.com.

Yingluo Liu, Email: yil243@health.ucsd.edu.

Yiming Gao, Email: yig017@ucsd.edu.

Andre Qin, Email: anqin@ucsd.edu.

Jin Lee, Email: jil327@health.ucsd.edu.

Gen-Sheng Feng, Email: gfeng@health.ucsd.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE296090). All data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers upon request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Gen-Sheng Feng conceived the project and supervised all aspects of the experiments and the manuscript. Yichun Ji and Yimin Gao performed bioinformatic data analysis. Yichun Ji, Li-Chun Lu, Hao Zhuang, Yingluo Liu, Andre Qin, and Jin Lee performed experiments and collected data. Yichun Ji, Li-Chun Lu, and Gen-Sheng Feng wrote the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01CA236074, R01CA239629, and P01AG073084. Li-Chun Lu is funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (110-2314-B-002-204-MY3).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): A non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galle PR, Decaens T, Kudo M, Qin S, Fonseca L, Sangro B, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) vs lenvatinib (LEN) or sorafenib (SOR) as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): First results from CheckMate 9DW. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:LBA4008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen L, Xin B, Wu P, Lin CH, Peng C, Wang G, et al. An efficient combination immunotherapy for primary liver cancer by harmonized activation of innate and adaptive immunity in mice. Hepatology. 2019;69:2518–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin B, Yang M, Wu P, Du L, Deng X, Hui E, et al. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of programmed death ligand 1 antibody for metastasized liver cancer by overcoming hepatic immunotolerance in mice. Hepatology. 2022;76:630–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Liao R, Wang G, Yang BH, Luo X, Varki NM, et al. Preventive inhibition of liver tumorigenesis by systemic activation of innate immune functions. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1870–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Calvisi DF. Hydrodynamic transfection for generation of novel mouse models for liver cancer research. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartwich J, Orr WS, Ng CY, Spence Y, Morton C, Davidoff AM. HIF-1alpha activation mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in neuroblastoma xenografts. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapisarda A, Melillo G. Role of the hypoxic tumor microenvironment in the resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies. Drug Resist Updat. 2009;12:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu X, Chu Q, Ma X, Wang J, Chen C, Guan J, et al. New insights into iNKT cells and their roles in liver diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1035950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Pouchoulen M, Holley AS, Reinl EL, VanRyzin JW, Mehrabani A, Dionisos C, et al. Viral-mediated inflammation by Poly I:C induces the chemokine CCL5 in NK cells and its receptors CCR1 and CCR5 in microglia in the neonatal rat cerebellum. NeuroImmune Pharm Ther. 2024;3:155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sada M, Watanabe M, Inui T, Nakamoto K, Hirata A, Nakamura M, et al. Ruxolitinib inhibits poly(I:C) and type 2 cytokines-induced CCL5 production in bronchial epithelial cells: A potential therapeutic agent for severe eosinophilic asthma. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2021;9:363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayson GC, Kerbel R, Ellis LM, Harris AL. Antiangiogenic therapy in oncology: Current status and future directions. Lancet. 2016;388:518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park R, Lopes L, Cristancho CR, Riano IM, Saeed A. Treatment-related adverse events of combination immune checkpoint inhibitors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sultan H, Wu J, Fesenkova VI, Fan AE, Addis D, Salazar AM, et al. Poly-IC enhances the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy by promoting T cell tumor infiltration. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e001224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda A, Digifico E, Andon FT, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Poly(I:C) stimulation is superior than Imiquimod to induce the antitumoral functional profile of tumor-conditioned macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49:801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lion E, Anguille S, Berneman ZN, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF. Poly(I:C) enhances the susceptibility of leukemic cells to NK cell cytotoxicity and phagocytosis by DC. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di S, Zhou M, Pan Z, Sun R, Chen M, Jiang H, et al. Combined adjuvant of poly I:C improves antitumor effects of CAR-T cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong C, Wang L, Hu S, Huang C, Xia Z, Liao J, et al. Poly(I:C) enhances the efficacy of phagocytosis checkpoint blockade immunotherapy by inducing IL-6 production. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;110:1197–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steelman AJ, Li J. Poly(I:C) promotes TNFalpha/TNFR1-dependent oligodendrocyte death in mixed glial cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann D, Schneider MA, Lenz BF, Talmadge JE. Toxicity of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid admixed with poly-L-lysine and solubilized with carboxymethylcellulose in mice. Pathol Immunopathol Res. 1987;6:37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE296090). All data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers upon request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Gen-Sheng Feng conceived the project and supervised all aspects of the experiments and the manuscript. Yichun Ji and Yimin Gao performed bioinformatic data analysis. Yichun Ji, Li-Chun Lu, Hao Zhuang, Yingluo Liu, Andre Qin, and Jin Lee performed experiments and collected data. Yichun Ji, Li-Chun Lu, and Gen-Sheng Feng wrote the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01CA236074, R01CA239629, and P01AG073084. Li-Chun Lu is funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (110-2314-B-002-204-MY3).