Abstract

Proteolysis triggered by the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) is needed for sister chromatid separation and the exit from mitosis. APC is a ubiquitin ligase whose activity is tightly controlled during the cell cycle. To identify factors involved in the regulation of APC-mediated proteolysis, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae GAL-cDNA library was screened for genes whose overexpression prevented degradation of an APC target protein, the mitotic cyclin Clb2. Genes encoding G1, S, and mitotic cyclins were identified, consistent with previous data showing that the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1 associated with different cyclins is a key factor for inhibiting APCCdh1 activity from late-G1 phase until mitosis. In addition, the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2 was identified as a negative regulator of APC-mediated proteolysis. Ectopic expression of IME2 in G1 arrested cells inhibited the degradation of mitotic cyclins and of other APC substrates. IME2 expression resulted in the phosphorylation of Cdh1 in G1 cells, indicating that Ime2 and Cdk1 regulate APCCdh1 in a similar manner. The expression of IME2 in cycling cells inhibited bud formation and caused cells to arrest in mitosis. We show further that Ime2 itself is an unstable protein whose proteolysis occurs independently of the APC and SCF (Skp1/Cdc53/F-box) ubiquitin ligases. Our findings suggest that Ime2 represents an unstable, meiosis-specific regulator of APCCdh1.

Crucial processes in the cell cycle, such as initiation of DNA replication, separation of sister chromatids, and exit from mitosis, depend on proteolytic degradation of critical regulatory proteins (1–3). Ubiquitin ligases play essential roles in these degradation processes. These enzymes catalyze the formation of chains of ubiquitin on their substrates, thereby targeting them for degradation by the 26S proteasome (4). The anaphase-promoting complex (APC), also known as cyclosome, is a multisubunit complex acting as ubiquitin ligase (5, 6). APC is essential for mitosis, and its activity is tightly cell cycle-regulated. Its activation at the metaphase/anaphase transition requires its association with the activator protein Cdc20. APCCdc20 triggers proteolytic degradation of the securin Pds1. Upon Pds1 proteolysis, the separase Esp1 is liberated, cleaves the cohesin subunit Scc1, and thereby triggers sister chromatid separation (7). APCCdc20 also initiates proteolysis of the S phase cyclin Clb5 and a fraction of mitotic cyclins (8–10). APCCdc20 activation is inhibited by the spindle assembly checkpoint, which prevents sister chromatid separation upon defects in the mitotic spindle or in the attachment of kinetochores (11).

Cdh1 (also termed Hct1) is related to Cdc20 and is needed for complete degradation of mitotic cyclins (12, 13). Cdh1's potential to associate with the APC is controlled by phosphorylation (14, 15). The cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1 phosphorylates Cdh1, thereby preventing its interaction with APC. A Cdk1-antagonizing phosphatase, Cdc14, is kept inactive in the nucleolus for most of the cell cycle (16, 17). Its release during anaphase promotes APCCdh1 complex formation and also induces transcription and stabilization of the Cdk1 inhibitor Sic1 (14). Thus, Cdc14 activates two mechanisms, cyclin proteolysis and Cdk1 inhibition, both resulting in Cdk1 inactivation and exit from mitosis. APCCdh1 remains active in the subsequent G1 phase and is turned off at the G1/S transition by Cdk1 phosphorylating the Cdh1 protein (18, 19).

Recent data showed that APC is also important for meiotic cell divisions. During meiosis, two rounds of chromosome segregation follow one round of DNA duplication. Little is known about APC regulation during meiosis. Pds1 is degraded during meiosis I in an APCCdc20-dependent manner, reaccumulates, and disappears again in meiosis II (20). Furthermore, destruction of the cyclin Clb1 seems to be mediated by a meiosis-specific activator related to Cdc20/Cdh1, Ama1 (21).

We performed a genetic screening to identify factors involved in the APC regulation. We screened for cDNAs whose expression in G1 phase inhibit proteolysis of a fusion protein of the mitotic cyclin Clb2 with lacZ. Various cyclins and the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2 were identified as proteins that stabilized Clb2-lacZ. Ectopic expression of IME2 in G1 cells stabilized mitotic cyclins and other APC substrates. Because Ime2 accumulation caused phosphorylation of Cdh1, Ime2 may be involved in APCCdh1 regulation during meiosis.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast Strains and Plasmids.

All strains are derivatives of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303 strain. Strains carrying hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged versions of Clb2 (19), Clb3 (22), Pds1 (23), and Cdh1 (19) have been described. A 2.8-kb fragment containing the GAL-IME2 fusion was cloned from the CEN plasmid, isolated from the GAL-cDNA library, into integrative plasmids YIplac204 and YIplac211 (24). For integrations, plasmids were linearized by Bsu36I and transformed into yeast cells. To tag the IME2 gene, a XbaI restriction site was introduced upstream of the stop codon of IME2 in the plasmid YIplac204-GAL-IME2. Six copies of the HA fragment were cloned as an XbaI fragment into this site.

Growth Conditions and Cell Cycle Arrests.

Before gene expression from the GAL1 promoter, cells were grown in raffinose medium. The GAL1 promoter was induced by the addition of galactose (2% final concentration). To turn off the GAL1 promoter, cells were filtered and resuspended in medium containing 2% glucose.

Strains lacking the G1 cyclins CLN1, CLN2, and CLN3, but containing CLN2 expressed from the methionine-repressible MET3 promoter, were cultivated in minimal medium lacking methionine. To arrest these cells in G1, methionine was added to a final concentration of 2 mM. To arrest cells in G1 with α-factor pheromone, cultures were incubated for 2.5 h in the presence of 5 μg/ml α-factor. To arrest cells in metaphase, cultures were incubated for 2 h in the presence of 15 μg/ml nocodazole.

Screening for cDNAs Stabilizing Clb2-lacZ.

A strain lacking all G1 cyclins (cln1, cln2, and cln3) containing MET-CLN2 and GAL-CLB2-lacZ gene fusions (S65) was transformed with a GAL-cDNA library (25) on a centromeric plasmid (URA3 marker). Transformants were plated on minimal medium plates lacking methionine and uracil. Colonies were transferred to nylon filters and arrested in G1 phase by placing filters on plates containing 2 mM methionine. After 3 h, filters were transferred to plates containing 2% galactose and 2 mM methionine. After 2.5 h, filters were frozen in liquid nitrogen and colonies were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. Blue colonies were collected. Plasmids of these colonies were retested and analyzed by restriction and sequencing. Because the expression of cDNAs encoding APC inhibitors likely results in cell cycle defects, plasmids were transformed into wild-type cells and only plasmids producing cell cycle phenotypes on galactose plates were analyzed further.

Immunoblot, Immunofluorescence, and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) Analysis.

Preparation of yeast cell extracts and protein immunoblot analysis were performed as described (26). The enhanced chemiluminescence detection system was used. For indirect immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde. Spheroplasts were prepared as described (27). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining and antitubulin antibodies were used for visualization of nuclei and spindles, respectively. FACS analysis was performed as described (28).

Results

A Screen for cDNAs Inhibiting Cyclin Degradation in S. cerevisiae.

To identify putative regulators of the APC, we screened for genes whose ectopic expression inhibited the degradation of a Clb2-lacZ fusion protein in G1-arrested cells. To arrest cells in G1 phase, we used a strain deleted of the G1 cyclins CLN1, CLN2, and CLN3 and containing a methionine-repressible MET3-CLN2 gene fusion, which caused cells to arrest in G1 upon methionine addition. This strain, also containing a GAL-CLB2-lacZ gene fusion (29), was transformed with a yeast cDNA library expressed from the GAL1 promoter (25). About 105 plasmid-carrying colonies were screened. Colonies were arrested on plates containing methionine and then transferred to galactose plates to express simultaneously the GAL-CLB2-lacZ and GAL-cDNA constructs. Cells impaired in cyclin proteolysis were expected to produce blue colonies on galactose medium, in contrast to white colonies produced by cells with normal APC activity.

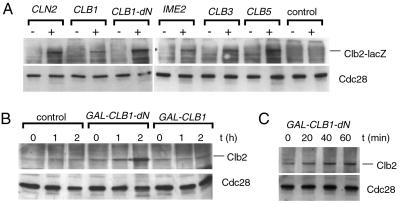

Plasmids from blue colonies were retransformed into a wild-type strain, and those plasmids causing cell cycle defects on galactose plates were analyzed further. They contained the complete ORFs from the G1 cyclin gene CLN2, the B-type cyclin genes CLB1, CLB3, and CLB5, and a truncated CLB1 cDNA lacking the N-terminal 120 aa, CLB1-dN. In addition, we identified plasmids containing the entire ORF of IME2, encoding a meiosis-specific protein kinase with sequence similarities to CDKs (30, 31). Immunoblotting showed that the expression of these cDNAs caused the accumulation of Clb2-lacZ protein in G1-arrested cells (Fig. 1A). Excepting the strain expressing CLN2, cells remained mostly arrested as unbudded cells (not shown).

Figure 1.

Ectopic expression of various cyclin genes and IME2 inhibits Clb2 proteolysis in G1 cells. (A) A S. cerevisiae strain deleted for all G1 cyclins (cln1, cln2, and cln3), containing MET-CLN2 and GAL-CLB2-lacZ gene fusions (S65), was retransformed with centromeric plasmids isolated from the screening of the GAL-cDNA library. Plasmids contained cDNAs of either the CLN2, CLB1, CLB1-dN (N-terminal 120 aa deleted), CLB3, CLB5, or IME2 genes. Cells were arrested in G1 phase by methionine addition, and genes were expressed by galactose addition. Clb2-lacZ protein was detected by immunoblotting with Clb2 antibodies before (−) and 2.5 h after galactose addition (+). Cdc28 (Cdk1) was used as loading control. (B) A bar1 deletion strain containing GAL-CLB2 (S61) was transformed with centromeric plasmids containing either GAL-CLB1, GAL-CLB1-dN, or a control plasmid. Cells were arrested in G1 with α-factor. Galactose was added and cells were incubated for 2 h. (C) Cells containing the GAL-CLB1-dN plasmid were transferred to glucose medium 60 min after galactose addition to turn off the GAL1 promoter (0 time point).

The identification of CLB1 and CLB1-dN cDNAs prompted us to compare the potential of full-length and truncated Clb1 protein to stabilize Clb2. In contrast to Clb1, Clb1-dN is thought to be stable in G1 cells, because it lacks the region encompassing the cyclin destruction box. It therefore can efficiently accumulate and activate Cdk1. We coexpressed CLB2 and either CLB1 or CLB1-dN in α-factor-arrested G1 cells. Cells expressing full-length CLB1 accumulated only low amounts of Clb2, but CLB1-dN caused Clb2 accumulation to high levels (Fig. 1B). Promoter shutoff experiments demonstrated that Clb2 was stabilized by Clb1-dN (Fig. 1C). These results show that Clb1-dN, but not Clb1, efficiently inhibits Clb2 degradation. Thus, high Cdk1 activity apparently correlates with a high capacity to inhibit Clb2 degradation.

Our identification of G1, S, and mitotic cyclins as negative regulators of Clb2 proteolysis is consistent with earlier data demonstrating that Cdk1 inhibits APCCdh1 from late G1 until anaphase (32).

Ectopic Expression of IME2 Stabilizes Cyclins Clb2 and Clb3.

Our screening revealed that IME2 expression displayed a phenotype similar to the expression of cyclins. Thus, Ime2, as Cdk1, may inhibit APC-mediated proteolysis. To analyze the effect of Ime2 in more detail, a GAL-IME2 gene fusion was integrated into yeast cells. Cells containing a single integration of GAL-IME2 were only modestly affected when grown on galactose medium, but cells carrying five copies of this construct displayed significant cell cycle defects (see below). Therefore, this strain was used for further experiments.

To test whether ectopic expression of IME2 affects Clb2 proteolysis in G1 phase, cells containing both GAL-CLB2 and GAL-IME2 constructs were arrested in G1 by α-factor pheromone. Then CLB2 and IME2 expression was induced by galactose. The simultaneous expression of both genes caused the accumulation and stabilization of Clb2, in contrast to cells containing only the GAL-CLB2 construct (Fig. 2 A and B). IME2 overexpression thereby resembles the phenotype of cells expressing CLB1-dN in G1 phase (Fig. 1). It is known that the expression of stable cyclins induces G1 cells to enter into S phase (18). The coexpression of IME2 and CLB2 caused many of the G1-arrested cells to initiate DNA replication (Fig. 2C), but cells did not start budding (not shown). Thus, the activity of the meiosis-specific kinase IME2 inhibits Clb2 proteolysis and causes entry into S phase.

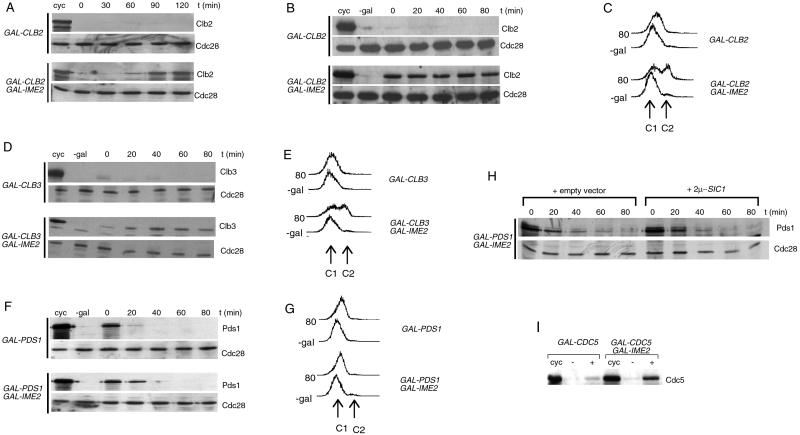

Figure 2.

Ectopic expression of IME2 inhibits degradation of mitotic cyclins and securin Pds1. (A) Strains containing bar1 deletions and either GAL-CLB2 (S57) or GAL-CLB2 GAL-IME2 (S381) constructs (CLB2 C-terminally tagged with the HA epitope) were arrested in G1 phase with α-factor for 2.5 h. Galactose was added (0 time point), and cells were incubated for 120 min. HA-tagged Clb2 was detected by immunoblotting with the anti-HA antibody (12CA5). Cdc28 was used as loading control. (B) Strains S57 and S381 were arrested with α-factor for 2.5 h. Galactose was added, and, after 1.5 h, cells were filtered and transferred to glucose medium containing α-factor (0 time point). cyc, cycling cells treated with galactose for 1.5 h. (C) DNA content of samples collected either before galactose addition (-gal) or 80 min after glucose addition. (D) Strains containing bar1 deletions and either GAL-CLB3 (S56) or GAL-CLB3 GAL-IME2 (S416) constructs (CLB3 C-terminally HA-tagged) were treated as in B. (E) DNA content. (F) Strains containing bar1 deletions and either GAL-PDS1 (S206) or GAL-PDS1 GAL-IME2 (S415) constructs (PDS1 C-terminally HA-tagged) were treated as in B. (G) DNA content. (H) Strain S415 was transformed with either a high-copy plasmid carrying the SIC1 gene or an empty plasmid. Transformed strains were treated as in B except that synthetic medium lacking leucine was used for plasmid selection. (I) Strains containing bar1 deletions and either GAL-CDC5 (S88) or GAL-CDC5 GAL-IME2 (S417) constructs (CDC5 C-terminally HA-tagged) were arrested with α-factor and galactose was added. Samples before (−) or 2 h after (+) galactose addition were collected.

We next tested whether Ime2 stabilizes other mitotic cyclins. Unlike CLB2, CLB3 is a cyclin gene also expressed during meiosis (33, 34). CLB3 and IME2 were expressed in G1-arrested cells. Clb3 accumulated to only low levels in the absence of Ime2, but the coexpression of both genes resulted in the accumulation and stabilization of Clb3 (Fig. 2D). The appearance of Clb3 caused cells to initiate DNA replication (Fig. 2E). These results show that Ime2 inhibits proteolysis of at least two mitotic cyclins.

Ime2 Inhibits Proteolysis of APC Substrates Pds1 and Cdc5.

We next tested whether IME2 overexpression causes the stabilization of a noncyclin APC substrate, the anaphase inhibitor protein Pds1. GAL-PDS1 and GAL-IME2 gene fusions were transiently coexpressed in G1-arrested cells. Whereas Pds1 rapidly disappeared in cells expressing only PDS1, the simultaneous expression of PDS1 and IME2 resulted in a partial but reproducible stabilization of Pds1 within 20 min after the promoter shutoff (Fig. 2F). This experiment shows that ectopic expression of IME2 delays Pds1 degradation in G1 cells.

The expression of GAL-IME2 and GAL-PDS1 did not induce cells to initiate DNA replication (Fig. 2G), indicating that Cdk1/Clb kinases are not activated under these conditions. However, it was shown previously that Ime2 induces activation of Cdk1/Clb kinases in meiosis (35). To distinguish whether the partial Pds1 stabilization is caused by Ime2 activity or, rather, residual Cdk1/Clb activity in these G1 cells, we determined the effect of Ime2 on the half-life of Pds1 in cells containing the Cdk1/Clb kinase inhibitor SIC1 on a high-copy plasmid. Pds1 was stabilized partially in the presence of high Sic1 levels, similar to the control strain (Fig. 2H).

To test whether Ime2 affected proteolysis of the polo-like kinase Cdc5, another APC substrate (36), we determined the accumulation of Cdc5 in G1 cells. In wild-type cells, Cdc5 accumulates only to low levels when expressed from the GAL promoter, because of its instability (ref. 36; Fig. 2I). Upon expression of IME2, increased levels of Cdc5 accumulated, suggesting that Ime2 inhibits efficient Cdc5 degradation.

We conclude that high levels of IME2 affect proteolysis of various APC substrates during G1 phase.

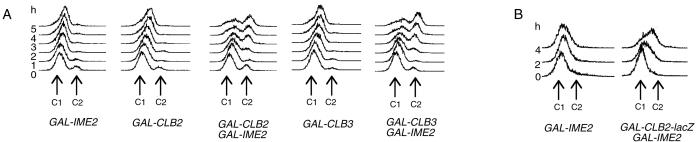

High Levels of IME2 in G1-Arrested Cells Are Not Sufficient to Trigger DNA Replication.

It was proposed earlier that Ime2 replaces the G1-specific Cdk1, the Cdk1/Cln kinase, during the meiotic cell cycle (35, 37). If Ime2 was functionally equivalent to Cdk1/Cln, then ectopic expression of IME2 should suppress the G1 arrest of cells having functional Cdk1/Cln kinases. To determine whether high levels of IME2 trigger DNA replication in the absence of Cdk1/Cln, GAL-IME2 was expressed for a prolonged period in α-factor-arrested cells. FACS analysis revealed that IME2 expression alone did not trigger DNA replication within 5 h (Fig. 3A). In contrast, cells coexpressing IME2 and CLB2 or CLB3 mostly replicated their DNA. Therefore, high levels of Ime2 are not sufficient to initiate DNA replication in α-factor-arrested cells. The expression of a cyclin gene also is required.

Figure 3.

High levels of Ime2 are not sufficient to trigger DNA replication in G1-arrested cells. (A) A bar1 deletion strain carrying GAL-IME2 (S418) was arrested in G1 with α-factor. Galactose was added (0 time point), and cells were incubated in the presence of α-factor. The DNA content was determined by FACS analysis. Similarly, strains expressing the indicated GAL constructs were analyzed. (B) A cln1, cln2, cln3 deletion strain carrying a MET-CLN2 construct (S66) and a similar strain containing, in addition, a GAL-CLB2-lacZ construct (S65) were transformed with a centromeric plasmid containing GAL-IME2. Transformed strains were arrested in G1 with methionine, and galactose was added.

Similarly, Ime2 did not trigger DNA replication in cells deleted for all G1 cyclins (Fig. 3B), whereas cells additionally expressing a CLB2-lacZ gene frequently entered S phase.

Thus, high levels of Ime2 cannot replace Cdk1/Cln kinases in triggering DNA replication, implying that Ime2 is not capable to take over all of the functions of the G1-specific Cdk1 at the G1/S transition.

Ectopic Expression of IME2 Triggers Phosphorylation of Cdh1.

APCCdh1 inactivation in the mitotic cell cycle is meditated by phosphorylation of Cdh1, causing the dissociation of Cdh1 from APC. Both Cln- and Clb-associated Cdk1 kinases seem to contribute to APCCdh1 inactivation (38, 39).

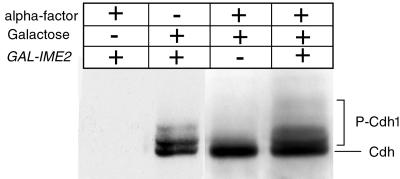

To test whether the inhibitory effect of Ime2 on APC-mediated proteolysis also is caused by Cdh1 phosphorylation, we used strains containing an HA-tagged version of Cdh1 expressed from a weak GAL promoter, described earlier as GALL-HA3-HCT1 (19). In G1-arrested wild-type cells, Cdh1 is not phosphorylated (Fig. 4, lane 3), but G1-arrested cells expressing the GAL-IME2 construct produced slower migrating bands (Fig. 4, lane 4), which most likely correspond to phosphorylated forms of Cdh1 (19). Similar mobility shifts were observed in cycling cultures that contain active Cdk1 kinases (Fig. 4, lane 2).

Figure 4.

Ectopic expression of IME2 promotes phosphorylation of Cdh1 in G1-arrested cells. A wild-type strain (S437) and a GAL-IME2 strain (S457), both containing bar1 deletions and N-terminally HA-tagged versions of CDH1 expressed from the GALL-promoter (19), were arrested in G1 with α-factor. Galactose was added to express the GAL constructs. HA-tagged Cdh1 was analyzed by immunoblotting (lane 3, S437; lane 4, S457). As control, strain S457 either was not treated with galactose (lane 1) or not arrested with α-factor (lane 2).

These results suggest that ectopic expression of IME2 promotes phosphorylation of Cdh1 during G1 phase.

High Levels of Ime2 Inhibit Bud Formation and Arrest Cells in Mitosis.

To analyze the phenotype of high levels of IME2 expressed in dividing cells, strains containing five copies of GAL-IME2 were shifted to galactose medium. The expression of IME2 caused the accumulation of unbudded cells in both haploid and diploid cells (Fig. 5A). Initially, cells were delayed in G1 phase (Fig. 5B, 2-h sample), but then they replicated their DNA. Nuclei and spindle staining revealed that these cells failed to segregate their DNA and arrest in G2/M phase, sometimes containing short spindles (Fig. 5 C and D).

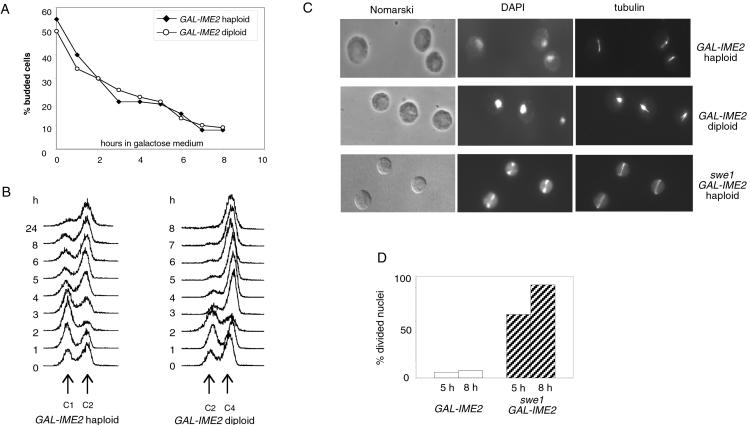

Figure 5.

High levels of Ime2 cause the accumulation of unbudded cells delayed in mitosis. Haploid (S379) and diploid (S424) strains containing the GAL-IME2 construct were grown in raffinose medium. Galactose was added (0 time point) and samples were collected at the indicated time points for monitoring the percentage of budded cells (A) and for determining the DNA content (B). (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy of haploid and diploid cells and of a swe1 deletion strain (swe1∷LEU2, S454) containing GAL-IME2, 5 h after galactose addition. (D) Percentage of divided nuclei in haploid SWE1 and swe1 strains, 5 and 8 h after galactose addition.

It was shown previously that cells defective in budding activate a control mechanism termed the morphogenesis checkpoint, resulting in a cell cycle delay in G2/M phase (40). To test whether the arrest of GAL-IME2 cells is caused by this control mechanism, we expressed IME2 in swe1 mutant cells defective in the morphogenesis checkpoint. Only few swe1 cells had undivided nuclei, whereas most cells contained segregated chromosomes and elongated mitotic spindles (Fig. 5 C and D).

Thus, the expression of Ime2 to high levels inhibits budding and blocks progression through mitosis. The cell cycle block in late anaphase/telophase is consistent with the model that Ime2 specifically affects APCCdh1 rather than general APC function.

Ime2 Is an Unstable Protein Whose Degradation Does Not Depend on APC or SCF (Skp1/Cdc53/F-box) Ubiquitin Ligases.

Because high levels of Ime2 have deleterious effects on cell cycle progression, it is tempting to speculate that Ime2 inactivation during meiosis may be important as CDK inactivation during mitosis. Ime2 contains two motifs (KxxL, KxxLxxxxxN) resembling the cyclin destruction box motif (KxxLxxxxN) and a PEST-rich region [region rich in proline (P), glutamate (E), serine (S), and threonine (T)] implicated in protein instability. This finding prompted us to analyze the stability of Ime2 by promoter shutoff experiments. HA-tagged Ime2 was degraded rapidly in normally dividing cells (Fig. 6A). Ime2's instability was not cell cycle-regulated, because Ime2 was degraded similarly in cells arrested in G1 by α-factor (Fig. 6B) or in M phase by the microtubule-depolymerizing drug nocodazole (Fig. 6C). Ime2 proteolysis was not delayed in cdc23–1 mutants defective in APC function (Fig. 6B) or in cdc4–1 and cdc34–2 mutants impaired in the SCF complex (Fig. 6C).

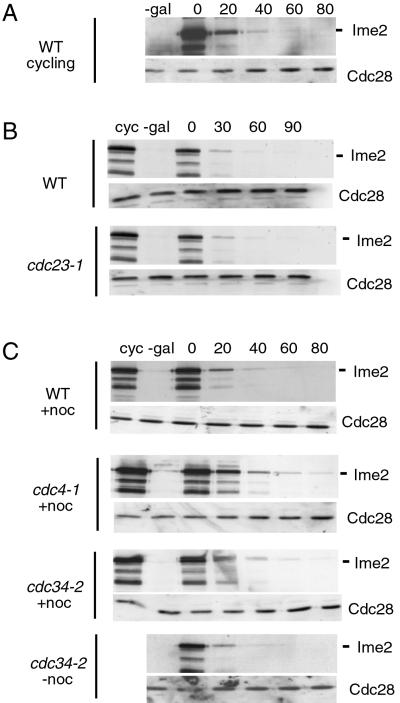

Figure 6.

Ime2 is an unstable protein whose degradation is independent of APC and SCF. (A) A strain (S396) containing a GAL-IME2 construct (IME2 C-terminally HA-tagged) was shifted for 2 h to galactose medium and then transferred to glucose medium (0 time point). Ime2 was analyzed by immunoblotting with HA-antibodies. cyc, cycling cells. (B) S396 and isogenic cdc23–1 mutants (S397), both containing bar1 deletions, were arrested in G1 with α-factor at 25°C. Galactose was added and cells were incubated for 45 min. Cells were shifted to 36°C, incubated for 45 min, then transferred to glucose medium containing α-factor and incubated at 36°C. (C) S396 and isogenic cdc4–1 (S407) and cdc34–2 (S408) mutants were arrested in M phase with nocodazole at 25°C (+noc). Expression of IME2 was induced by galactose for 45 min. Then, cells were shifted to 36°C, incubated for 45 min, transferred to glucose medium containing nocodazole, and incubated at 36°C. A cdc34–2 culture was treated similarly, but nocodazole was omitted (−noc).

These findings indicate that Ime2 is an unstable protein kinase whose proteolysis occurs independently of the conventional APC and SCF ubiquitin ligases.

Discussion

Identification of Negative Regulators of APC-Mediated Proteolysis.

We aimed to identify regulators of the APC by screening a yeast cDNA library for genes whose expression to high levels prevents degradation of a Clb2-lacZ reporter protein in G1-arrested cells. We identified various cyclins and the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2 as inhibitors of APC-mediated proteolysis.

The identification of G1, S, and mitotic cyclins implies that Cdk1 associated with any of these cyclins is capable of inhibiting APC-mediated proteolysis. These findings are consistent with previous data showing that Cdk1 is a key factor for turning off APCCdh1 in late G1 and for keeping it inactive during S, G2, and most of M phase (6, 32). Cdk1 associated with different cyclin proteins was shown to directly phosphorylate the activator protein Cdh1 and trigger its dissociation from APC (15, 19). Our findings underline the crucial role of Cdk1 as an inhibitor of APCCdh1. The continuous presence of Cdk1 activated by different types of cyclins helps to ensure that APCCdh1 cannot be activated during the cell cycle before Cdc14 phosphatase is released from the nucleolus, a process that depends on proper spindle orientation and the mitotic exit network (41).

Ime2, a Putative Meiosis-Specific Regulator of APCCdh1.

We have shown that ectopic expression of IME2 results in the accumulation and stabilization of the mitotic cyclins Clb2 and Clb3 in G1-arrested cells. We showed further that Ime2 triggers phosphorylation of Cdh1, suggesting that Ime2 inhibits APC activity by means of the Cdh1 activator protein. IME2 expression also delayed proteolysis of Pds1 and Cdc5, two additional APC substrates. Pds1 was affected only slightly, possibly because it is degraded primarily by APCCdc20 during G1 phase, but other data suggested that APCCdh1 is involved in Pds1 removal (12, 42). The rather weak influence of Ime2 on Pds1 also could be explained by Ime2's own instability. After turning off the GAL promoter in our test system, Ime2 gets degraded at about the same time as Pds1 (compare Figs. 2F and 6).

In summary, our results demonstrate that ectopic expression of IME2 in G1 cells inhibits APC-meditated proteolysis. Because IME2 normally is expressed only in meiotic cells, we suggest that this protein kinase acts as a regulator of APCCdh1 during meiosis.

Similarities and Differences of Ime2 with Cdk1/Cln Kinases.

There are several indications that Ime2 fulfills in meiosis the functions of the G1-specific CDKs, the Cdk1/Cln kinases. First, Ime2 shares sequence similarities with CDKs (43). Second, deletion of all CLN genes does not affect sporulation, implying that Cdk1/Cln kinases are dispensable for meiosis (35). Third, degradation of the Cdk1 inhibitor Sic1 is triggered in the mitotic cell cycle by Cdk1/Cln and in meiosis by Ime2 (35).

The capacity of Ime2 to promote Cdh1 phosphorylation suggests that this kinase may replace Cdk1/Cln in triggering inactivation of APCCdh1 in late G1 phase of the meiotic cell cycle. It was shown recently that G1-specific kinases are not sufficient for completely inactivating APCCdh1 in the mitotic cell cycle. This process also requires Cdk1/Clb kinases (38, 39). Similarly, the combined function of both Ime2 and accumulating Cdk1/Clb kinases may be needed for completely turning off APCCdh1 in meiosis.

Ime2 clearly displays some functional similarities with Cdk1/Cln, but there are significant differences between these kinases. High levels of Ime2 expressed in α-factor-arrested cells or in cells lacking G1 cyclins failed to promote DNA replication, implying that Ime2 is not sufficient to replace Cdk1/Cln in this process. Ime2 may not be sufficient to induce transcription of CLB genes. Indeed, upon coexpression of IME2 with CLB genes, most cells replicated their DNA. We conclude that Ime2 has only partially functional similarities to Cdk1/Cln kinases and fulfills some but not all of their functions in promoting entry into S phase.

Another difference between Cdk1/Cln and Ime2 is striking. The G1-specific kinase triggers budding, but Ime2 clearly inhibits this process. The expression of IME2 in cycling cultures induced the accumulation of unbudded cells that replicated their DNA. The inhibition of budding in mitotic cells also suggests a role of Ime2 in preventing budding in meiosis.

Is Ime2 Activity Regulated by Its Stability?

We have shown that Ime2 is unstable when expressed in normally dividing cells. Proteolysis of Ime2 appears to be independent of the APC or the SCF ubiquitin ligases, and the machinery responsible for Ime2 instability remains to be identified. The permanent instability of Ime2 in dividing cells may help to ensure that Ime2 never accumulates in the mitotic cell cycle, where it could interfere with processes such as budding or APC activity. It is unknown whether Ime2 also is permanently unstable during meiosis or whether it then gets periodically stabilized. Stabilization could be a mechanism to allow efficient accumulation of Ime2 in early meiosis, in addition to the transcriptional induction of the IME2 gene (31, 43).

Accumulation as well as removal of Ime2 may be important during meiosis. We have shown that high levels of Ime2 blocked progression through mitosis. The continued presence of active Ime2 also may interfere with cell cycle progression in meiosis. Because Ime2 itself is an unstable protein, its inactivation during meiosis may be triggered by turning on its rapid proteolysis.

Little is known about APC regulation during meiosis. Pds1 was found to be degraded at anaphase onset in both meiosis I and II (20). Pds1 reaccumulation after its destruction in meiosis I implies that APC needs to be inactivated between meiosis I and II. Recently, Ama1, a meiosis-specific protein related to Cdc20/Cdh1, was identified (21). Ama1 seems to be required for Clb1 degradation in meiosis I, but it is not essential for meiosis II. CDH1 expression also was found to be induced in meiosis (44), indicating that Cdh1 and Ama1 may have redundant roles in triggering cyclin proteolysis.

It seems that at least three different APC complexes need to be regulated during meiosis. The identification of Ime2 as an inhibitor of APC-mediated proteolysis suggests that this protein kinase represents an important player in APC regulation during meiosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony Bretscher for providing a GAL-cDNA library, Marta Galova and Kim Nasmyth for strains and plasmids, and Wilfried Kramer and Anke Schürer for help with FACS analysis. We acknowledge Patrick Dieckhoff and Yasemin Sancak for support and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the Volkswagen-Stiftung.

Abbreviations

- APC

anaphase-promoting complex

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- HA

hemagglutinin

- SCF

Skp1/Cdc53/F-box

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Peters J M. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:759–778. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorgensen P, Tyers M. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:610–617. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zachariae W. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:708–716. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstrasser M. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan D O. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E47–E53. doi: 10.1038/10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachariae W, Nasmyth K. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2039–2058. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasmyth K, Peters J M, Uhlmann F. Science. 2000;288:1379–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shirayama M, Toth A, Galova M, Nasmyth K. Nature (London) 1999;402:203–207. doi: 10.1038/46080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumer M, Braus G H, Irniger S. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeong F M, Lim H H, Padmashree C G, Surana U. Mol Cell. 2000;5:501–511. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amon A. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visintin R, Prinz S, Amon A. Science. 1997;278:460–463. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwab M, Lutum A S, Seufert W. Cell. 1997;90:683–693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visintin R, Craig K, Hwang E S, Prinz S, Tyers M, Amon A. Mol Cell. 1998;2:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaspersen S L, Charles J F, Morgan D O. Curr Biol. 1999;9:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visintin R, Hwang E S, Amon A. Nature (London) 1999;398:818–823. doi: 10.1038/19775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shou W, Seol J H, Shevchenko A, Baskerville C, Moazed D, Chen Z W, Jang J, Charbonneau H, Deshaies R J. Cell. 1999;97:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amon A, Irniger S, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1994;77:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W. Science. 1998;282:1721–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salah S M, Nasmyth K. Chromosoma. 2000;109:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s004120050409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper K F, Mallory M J, Egeland D B, Jarnik M, Strich R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14548–14553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250351297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irniger S, Nasmyth K. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1523–1531. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Fix O, Peters J M, Kirschner M W, Koshland D. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3081–3093. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gietz R D, Sugino A. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Krizek J, Bretscher A. Genetics. 1992;132:665–673. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surana U, Amon A, Dowzer C, McGrew J, Byers B, Nasmyth K. EMBO J. 1993;12:1969–1978. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pringle J R, Adams A E, Drubin D G, Haarer B K. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:565–602. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94043-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein C B, Cross F R. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1695–1706. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irniger S, Piatti S, Michaelis C, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1995;81:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida M, Kawaguchi H, Sakata Y, Kominami K, Hirano M, Shima H, Akada R, Yamashita I. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:176–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00261718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell A P, Driscoll S E, Smith H E. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2104–2110. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amon A. EMBO J. 1997;16:2693–2702. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahmann C, Futcher B. Genetics. 1995;140:957–963. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grandin N, Reed S I. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2113–2125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dirick L, Goetsch L, Ammerer G, Byers B. Science. 1998;281:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. EMBO J. 1998;17:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee B, Amon A. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:770–777. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J N, Park I, Ellingson E, Littlepage L E, Pellman D. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:85–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeong F M, Lim H H, Wang Y, Surana U. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5071–5081. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5071-5081.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lew D J. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoyt M A. Cell. 2000;102:267–270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudner A D, Hardwick K G, Murray A W. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1361–1376. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell A P. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:56–70. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.56-70.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown P O, Herskowitz I. Science. 1998;282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]